Synecology

an annual publication of the Southeastern Center for Conservation

an annual publication of the Southeastern Center for Conservation

for the natural world, it also brings exciting plant science and conservation stories closer to home.

The conservation of rare plants and their ecosystems is a cornerstone of the Garden’s mission and I am honored to be leading a team that is tremendously dedicated to this goal.

In the past year, we have been active across the Southeast, from the mountains of North Carolina to the coastal wet prairies of the Florida panhandle. You can witness some of our work when you visit the Garden. Inside the Southeastern Center for Conservation, visitors can look through a glass window into one of our labs to observe imperiled plants being propagated in delicate glass beakers. Along the hallway are interpretative panels that tell the conservation story of mountain golden heather, a North Carolina endemic wildflower that we’re fighting to protect, as well as macrophotography of insects observed at a Florida state park that we are helping to restore. Outside in the Conservation Display Garden, visitors can marvel at a diversity of Southeastern native plants, several of which are threatened species that the Center is actively working to conserve. A miniature meadow of orchids, carnivorous plants and other native wildflowers, carefully assembled and maintained by the Garden’s Horticulture & Collections team, is a living diorama of wet prairie habitats that our team is helping to restore on Florida’s Gulf Coast. The Garden connects people to plants in many ways and in addition inspiring delight and love

The Garden’s Southeastern Center for Conservation is recognized regionally, nationally and internationally as a hub of plant conservation excellence. But the future of plant diversity cannot be secured by just one or a few institutions. We owe much of our success to 20 years of conservation partnerships across the United States, as well as global partnerships such as those we have forged through coordinating the Global Conservation Consortium for Magnolia. Both locally and abroad, I am constantly inspired by our partners and their work. We are incredibly fortunate to be with so many talented people and institutions in the fight to preserve plant diversity worldwide.

There are times when our fight against biodiversity loss, climate change and habitat destruction can feel overwhelming. However, collectively we can make a positive impact and turn the tide. Please enjoy reading some of our success stories from the previous year’s work as our amazing team addresses pressing issues, including research on Florida torreya’s population genetics and response following Hurricane Michael, new projects from our Conservation Seed Bank, successes in Conservation Horticulture, the release of a regional Ex Situ Gap Analysis and many other exciting stories.

Vice President, Conservation & Research Atlanta Botanical Garden

The outlook for many of our threatened native plants remains precarious in this rapidly changing world.

Atlanta Botanical Garden Southeastern Center for Conservation established in 2019

Mary Pat Matheson Emily Coffey, PhD

The Anna and Hays Mershon Vice President President & CEO Conservation & Research

Loy Xingwen, PhD Bo Shell Editor Designer

Cami Adams Field Technician, EPA Florida

Laurie Blackmore, MSc Conservation & Research Manager

Amanda Carmichael, MSc Conservation Laboratories Supervisor

Carson, MSc Safeguarding Nursery Coordinator

Caitlin Crocker Field Biologist, EPA Florida

Lauren Eserman, PhD Research Scientist, Genetics

Caleb Evans Conservation Horticulture Technician

John Evans, MSc Conservation Horticulture Manager

Jonathan Gore Conservation Database Coordinator

Will Hembree, MSc Senior Conservation Horticulturist

Jason Ligon Micropropagation & Seed Bank Coordinator

Jean Linsky, MSc GCC Magnolia Coordinator

Loy Xingwen, PhD Research Scientist, Ecology

Liz Miller Field Biologist, GEBF Florida

Grant Morton, PhD Conservation Seed Bank Curator

Sarah Norris, MSc Conservation Partnerships Assistant

Sandee Phillips, MA Grants & Contracts Analyst

Carrie Radcliffe, MSc Conservation Partnerships Manager

Ian Sabo Field Biologist

Ashlynn Smith Gulf Coast Coordinator

Jeff Talbert, MBA Project Coordinator, GEBF Florida

Maria Vogel, MSc Scientific Executive Assistant to the Vice President

The Southeastern Center for Conservation humbly acknowledges the indigenous people of our focal region. We are working on the homelands of many tribes and it is with gratitude and appreciation that we seek to conserve species and natural systems that were nurtured by those stewards possessing unparalleled relationships with these lands since time immemorial. The Center recognizes the many impacts of colonialism and the irreparable losses that have been endured by the region’s original inhabitants –including humans, animals, plants and stones – and the land itself.

To learn more about tribes in the Southeast, visit the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Tribal Story Map (secasc.ncsu.edu/tribal-resources/) and the Native Land Digital (native-land.ca) interactive online maps. These are on-going works in progress that are not meant to represent official or legal tribal boundaries; to learn about definitive areas, please contact the nation(s) in question.

by John Evans, MSc Conservation Horticulture Manager

by John Evans, MSc Conservation Horticulture Manager

Mountain golden heather (Hudsonia montana) is a critically imperiled, diminutive woody plant found on just a few dry rocky outcrops of Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina. Not a true heather, this plant is instead a member of the rock rose family, Cistaceae. Although its distribution was limited even at the time of its first description in 1816, reports at that time indicate that populations were much greater than what we observe today1. Severe population declines in the last several decades have been attributed to competition for light with taller plant species due to fire suppression, as well as accidental trampling by leisure hikers and climbers 2,3. The Southeastern Center for Conservation is working hard to restore H. montana population numbers in the wild.

While site protection and habitat management are the first line of defense for many imperiled plants, botanical gardens can also help by creating and maintaining conservation collections of imperiled species. Plants in conservation collections can be multiplied by propagation to create more plants that can be outplanted to boost wild populations. This requires collecting seeds and cuttings from the wild, tracking all plant material by maternal line (Figure 1), conducting controlled propagation experiments, conducting experiments to test methods for outplanting in the wild, conducting actual outplantings in the wild and finally, monitoring the success of outplanting.

Previous attempts by conservation biologists to grow H. montana in captivity yielded mixed results — seeds germinated well but the seedlings would die within weeks (M. Kunz, pers. com.). One of our major research objectives was to determine the cause of seedling mortality and develop a successful seed propagation protocol (Figure 2). In addition to experimenting with a variety of potting mixes, we also evaluated whether a top dressing of biocrust (live microbes collected on the soil surface around wild populations) provided benefits to the plants. We discovered that standard, commercially available potting mixes are not suitable for growing H. montana. Instead, specially blended potting mixes, which we created to mimic the texture and composition of the natural soils in which H. montana grows, yielded both high germination rates and high seedling survival rates. We found no significant differences between treatments with and without biocrust material, so it may not be necessary for growing this species.

Additionally, we tested if stem cuttings taken from wild plants could be rooted and grown. This is one way to multiply plants from populations that are not producing adequate seeds in the wild. We found that the most significant determinant of success was the timing that cuttings were taken. H. montana cuttings root most successfully from material collected in mid-spring. In fact, plants rooted in 2021 are growing robustly in the Garden’s Conservation Greenhouse and have even bloomed (Figure 3).

rooted in 2021 are growing robustly in the Garden’s Conservation Greenhouse and have even bloomed.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that any botanical garden has managed to successfully grow and bloom H. montana.

Our next steps are to conduct an experimental outplanting of the newly propagated H. montana plants at one of the sites where the seeds and cuttings were originally sourced from. We will experiment with both spring and fall planting times, to determine the best season for outplanting. Each plant will be geolocated using a high precision GPS device and carefully monitored over several years for survival and success. Care will be taken to place plants in locations away from human traffic, to give them the best chance of survival. We will continue to work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Pisgah National Forest to ensure the continued survival of this unique mountain wildflower.

We found that the most significant determinant of success was the timing that cuttings were taken. H. montana cuttings root most successfully from material collected in mid-spring. In fact, plantsREFERENCES 1. Nuttall, T. 1818. The genera of North American plants. Philadelphia, PA. 2. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1983. Mountain Golden Heather (Hudsonia montana) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, GA. 3. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2019. Mountain Golden Heather 5-Year Review Addendum. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, GA.

be the best bet for storing large quantities of this species in a limited space. This year, T. floridana shoot tips will be sent to the Garden where Conservation Laboratories Supervisor, Amanda Carmichael, and Seed Bank Curator, Dr. Grant Morton, will

ful. We look forward to growing the Conservation Seed Bank at the Atlanta Botanical Garden and are thankful to all of our staff, partners and volunteers for choosing to participate in safeguarding some of the world’s most unique flora.

COVER STORY: New insights into the genetics and ecology of Florida torreya

The species is listed as ‘critically endangered’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and ‘endangered’ by the United States government. One of the major causes for the decline of T. taxifolia is an invasive fungal pathogen, Fusarium torreyae. In 2018, Hurricane Michael also killed many wild T. taxifolia trees.

The Atlanta Botanical Garden has been a leader in the conservation of T. taxifolia since 1991. To safeguard the future of this species, the Garden’s Southeastern Center for Conservation has collected and cultivated branch cuttings from over 400 wild trees, representing more than half of the total known wild population. These newly propagated trees have been added to the Garden’s Conservation Safeguarding Nursery. This proved to be a vital conservation measure, as many of the wild trees from which cuttings were originally taken have since perished. Without safeguarding collections, unique genetic diversity may be lost forever whenever a wild tree dies.

The Center recently conducted a study to examine the genetic diversity contained within T. taxifolia. One objective was to evaluate whether current collections sufficiently capture the genetic diversity of the wild population. This is vital for ensuring that current and future safeguarding practices are effective. Understanding the genetic makeup of T. taxifolia may also help in future breeding programs for better fungal resistance. A second objective was to assess overall levels of genetic diversity in the remaining wild population.

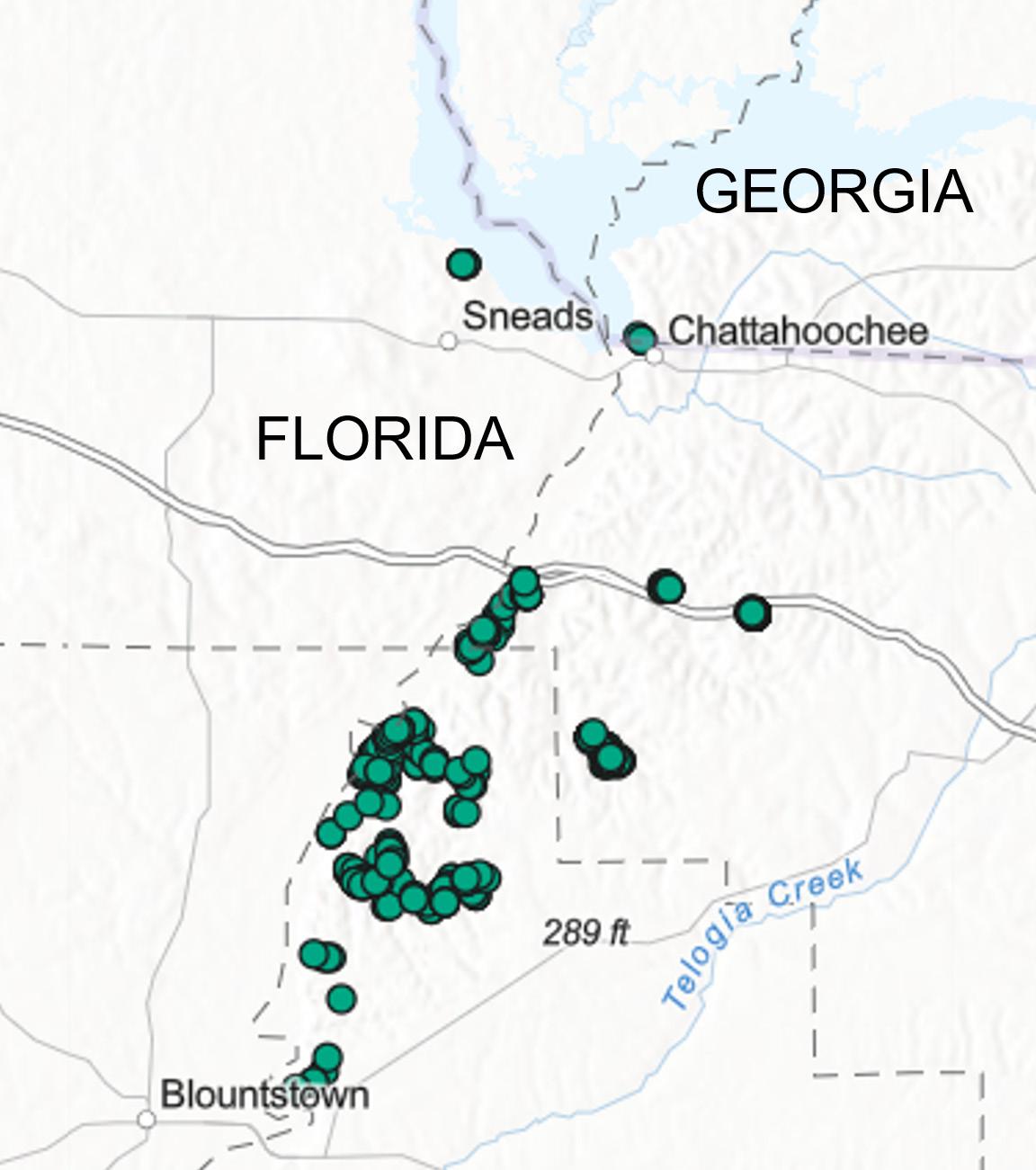

In partnership with the Florida Native Plant Society, leaf samples were collected from wild trees in public and private lands across the species’ entire range (Figure 1). Conifers are notorious for having extremely large and highly repetitive nuclear genomes, making typical population genomic techniques such as Genotype-by-Sequencing (GBS), restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RADseq) and genome skimming unfeasible. As such, a technique called ‘target gene capture’ was used to target sequencing on specific loci within the large and repetitive genome of the species. To this end, the Center collaborated with the University of Georgia to develop a target capture bait set that can be used on T. taxifolia

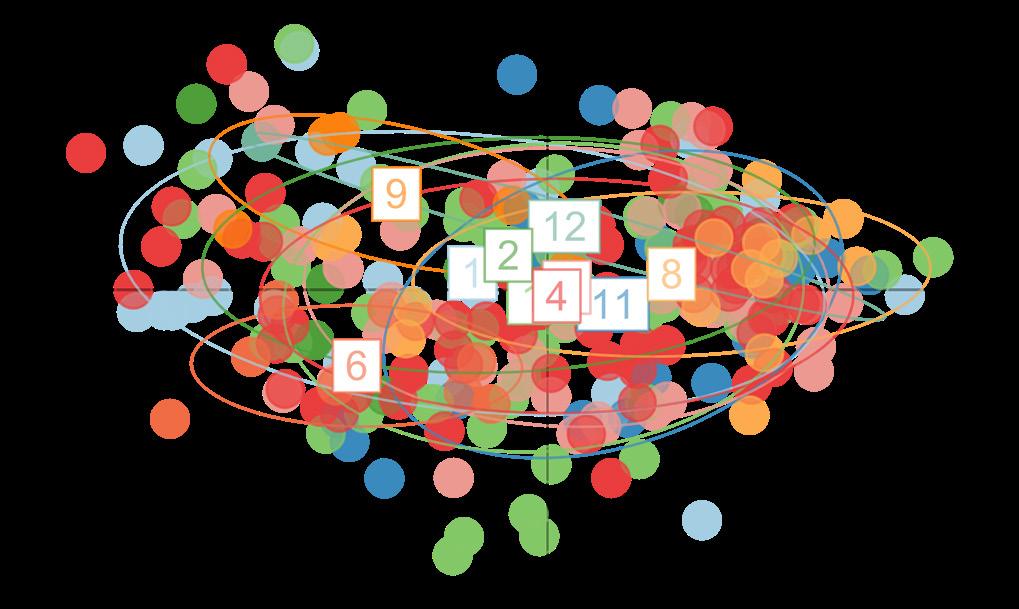

Study results show that genetic diversity of the species is comparable to other conifers with narrow ranges, and the wild population has maintained unexpectedly high genetic diversity despite

having suffered tremendous decline. The genetic makeup of trees from different ravines was largely overlapping, indicating that genetic diversity is not spatially clustered (Figure 2). This implies that future collection efforts for safeguarding the species do not need to focus on specific locations and instead need to be spatially dispersed. Overall, the high level of genetic diversity within the species is promising for breeding programs. Study findings will also help inform future plans for safeguarding collections of this rare and beloved tree.

Florida torreya (Torreya taxifolia) is one of the rarest conifers in North America. In the last century, populations have declined from nearly 700,000 trees to around 700 trees today.FIGURE 2: Ordination plot of the principal components analysis of genetic diversity of 353 T. taxifolia trees. Each point is an individual tree, with distant dots showing two trees that are more genetically different than two points closer together. Colors show the ravines that each tree sample originated from.

by Loy Xingwen, PhD Research Scientist, Ecology

by Loy Xingwen, PhD Research Scientist, Ecology

On October 10th 2018, Hurricane Michael became the first recorded Category 5 hurricane to make landfall in the Florida Panhandle. In addition to devastating regional towns and cities, the Hurricane blasted through Torreya State Park - the last stronghold of one of the world’s most threatened conifer trees: Florida torreya ( Torreya taxifolia ). The storm instantly killed many T. taxifolia and destroyed vast areas of their forest habitat.

Fortunately, several hundred T. taxifolia trees made it through the storms. The Southeastern Center for Conservation and our collaborators immediately launched several urgent conservation and research efforts. Among these is an ongoing multiyear study that documents the lives of 40 wild T. taxifolia trees that managed to survive the initial hurricane impact. A primary objective of this study is to determine how forest

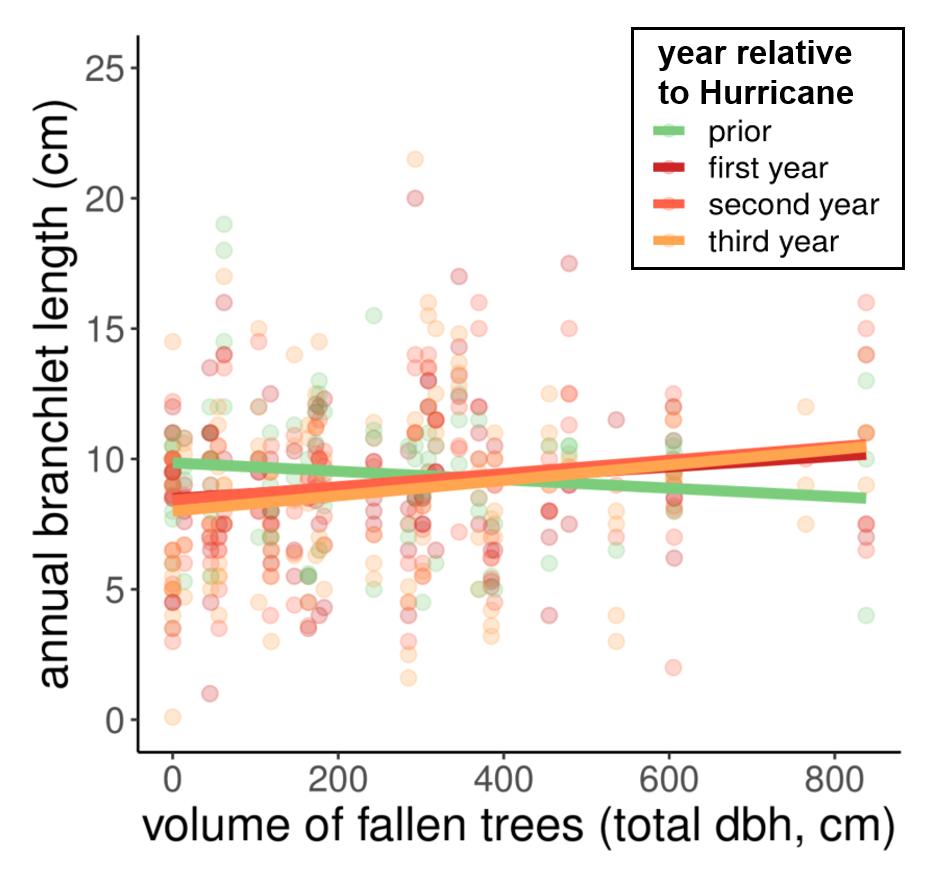

FIGURE 1: Relationship between the lengths of branchlets produced each year by 40 T. taxifolia trees and the total volume of fallen trees (diameter at breast height) in the surrounding forest. Generalized linear mixed models show that annual growth significantly varied by year. Branchlets produced after the hurricane (red, orange, yellow points and lines) were longer wherever tree fall in the surrounding forest was greater.

damage caused by Hurricane Michael will affect the long-term health of the T. taxifolia survivors.

The 40 torreya trees, located all over Torreya State Park, were selected to be individuals of similar size and alive in the spring following Hurricane Michael. Every fall since the Hurricane, our researchers have returned to each of the 40 trees to measure their growth and health. In addition, they surveyed the forest damage surrounding each of the 40 trees, recording the volume and identities of all standing and fallen trees in the surrounding forest habitat of each T. taxifolia . Field data loggers were set up at each tree to continuously measure environmental variables like temperature and humidity. These detailed surveys have revealed interesting insights into the ecology of T. taxifolia .

In the wild, T. taxifolia typically grows under the cool shade of other taller tree species, so our researchers expected forest canopy gaps caused by hurricane damage to be harmful to this alleged shade-loving species. However, preliminary analyses of the 40 trees data suggest that hurricane damage to their forest habitats might have improved their growth. While some T. taxifolia trees showed signs of sun damage to their leaves in the summer following the hurricane, the trees quickly adjusted to sunnier and warmer conditions and responded by producing significantly more growth in subsequent years (Figure 1).

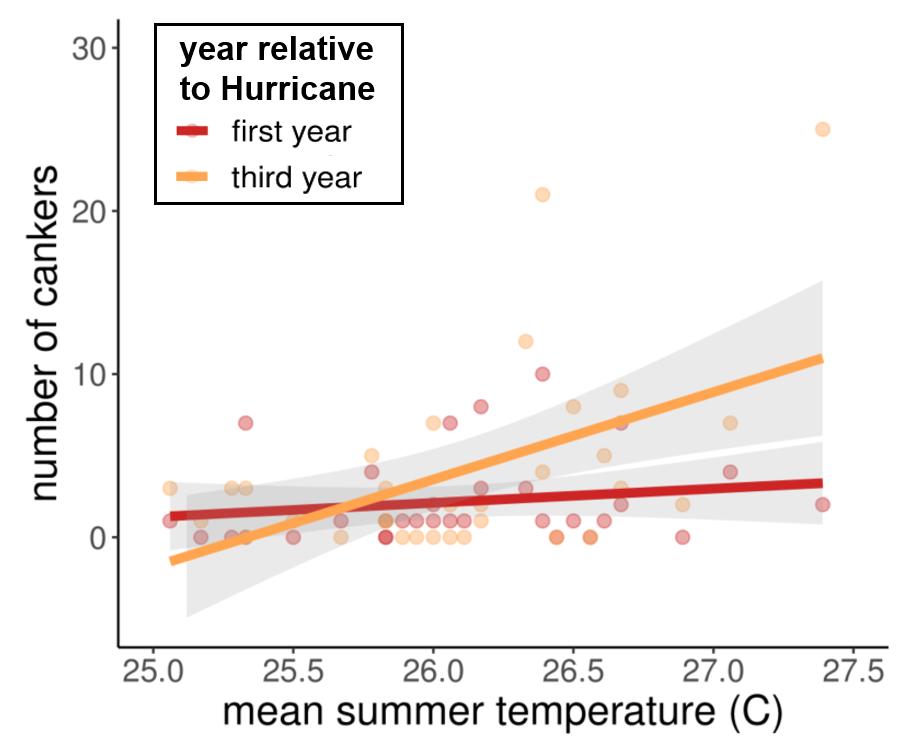

But there’s a catch. Preliminary analyses also suggest that higher temperatures may be exacerbating the lethal fungal canker diseases that are plaguing the species (Figure 2). While it is tempting to consider moving T. taxifolia to more northern latitudes, where cooler temperatures might make the trees more resilient to fungal diseases, the global and ongoing threat of global warming means that such solutions are only temporary unless climate change is effectively mitigated. Moving such a highly susceptible fungal host to a novel ecosystem is also risky, as even if the transplants are initially free of fungal pathogens, doing so creates opportunity

for novel fungal diseases to eventually establish in ecosystems and permanently change the local ecology.

Intense storms and warming temperatures threaten T. taxifolia in its native range, so it is critical that we safeguard the species in botanical collections outside of its native habitat where the pathogen spread can be contained and monitored. The Southeastern Center for Conservation is leading ex-situ conservation for this species. Preserving and maintaining the genetic diversity of the T. taxifolia gives us valuable time and opportunities to help the species overcome some of the immediate threats to its survival.

FLORIDA SANDILLS are characterized by their dry sandy soils, sparsely scattered longleaf pines, turkey oaks and fields of wiregrass. Plants that grow here are well adapted to the blazing sun and frequent fire. Sandhills support threatened animals like the gopher tortoise and red cockaded woodpecker.

SLOPE FORESTS grow in the cool and moist microclimates created by steephead ravines - the habitat of Florida

torreya. Slope forests boast immense plant diversity. Other rare species found here include Ashe’s magnolia, Florida yew, croomia and bay starvine.

HURRICANE MICHAEL devastated the Florida panhandle in 2018, the first recorded category 5 hurricane to make landfall in the region. The hurricane severely damaged forests at Torreya State Park. Within its slope forests, the volume of tree fall ranged from 0-94%.

FLORIDA TORREYA IS ONE OF THE WORLD’S RAREST CONIFERS and found only in and around Torreya State Park. Once abundant in its habitat, the species has declined dramatically in the last century. Potential causes include fungal diseases and climate change. In addition, many individuals were lost to Hurricane Michael. The Southeastern Center for Conservation continues to lead rescue and research efforts for this species.

DECIDUOUS TREES create the dense canopies of slope forests, which support shade-loving plants. Typical canopy trees here include American beech, tulip poplar, white ash and black oak.

GROUNDWATER carves the steephead ravines that riddle the sandhills. Rain percolates the sandhills and leaks into steephead ravines. As it reaches the surface, it causes the sand at the bottom of the ravines to crumble away, lengthening the ravines.

PLANTS OF COOLER CLIMATES thrive in the shade and shelter of steephead ravines. Species typically found in the Piedmont or southern Appalachian mountains are common here: mountain laurel, eastern leatherwood, wild hydrangea, rattlesnake plantain and bloodroot. This unique and rare community of cool and warm flora is threatened by climate change.

Coordinator

Coordinator

Fire is integral to many ecosystems of the southeastern United States. Fire was naturally common in the coastal plains of the Southeast due to frequent lightning storms and abundant natural fuel, until the arrival of European settlers1. Since before the 1900s, concerted action to actively prevent natural fires dramatically affected the region’s fire ecology2. Today, even though scientists and conservation practitioners alike recognize the benefits of fire3, 4, decades of fire suppression have had lasting consequences.

Fire suppression has fundamentally altered Florida’s coastal wetland ecosystems. Where once grew scattered pines and immensely diverse wet prairies, today are dense impenetrable woody thickets that support little biodiversity. In parts of the Florida panhandle, these thickets primarily comprise just one small shrubby tree species, the native spring titi (Cliftonia monophylla). Anecdotal evidence suggests that the thickets create dense shade that prevent the growth of historical herbaceous wet prairie plants. The trees may also increase soil carbon and nitrogen content, by producing copious leaf litter. This is of particular concern as nutrient-poor soils are necessary to support the region’s many iconic wetland flora, such as carnivorous plants. Thickets may provide poor habitat for wetland animals, such as amphibians, by changing surface and subsurface water flow and quality. However, many of these theories about the impacts of woody thickets on wetlands have not been scientifically tested.

To evaluate the severity of habitat change and identify viable solutions to the problem, the Southeastern Center for Conservation and the University of Florida are collaborating on a restoration project funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This ongoing project takes place at Deer Lake State Park, Florida. The project has three phases, two of which have already been completed. We first measured pre-restoration baseline conditions of plant biodiversity, amphibian biodiversity, soil nutrient levels and hydrology within the park. We then cleared the spring titi and other woody species from 12.6 acres of wetland and examined whether this improved streamflow and reduced nutrients in groundwater and streams. We are currently at the third and final phase of this project: testing different techniques to promote the return of historical wet prairie biodiversity. The techniques that are being tested include the use of fire, the removal of accumulated leaf litter and the application of plant material with diaspores (plant material containing seeds harvested from healthy wet prairies). We aim to evaluate which restoration techniques lead to the greatest recovery in herbaceous plant communities, amphibian communities, as well as improve water retention and quality. The results of this project will inform our long-term goal to restore 1,000 hectares of wetlands in the Florida panhandle.

Our experiment at Florida’s Deer Lake State Park tests the effectiveness of four different restoration treatments in various combinations. At each of eight wetland sites, we have set up 16 treatment units in a full factorial experimental design, where all combinations of the four treatments will be tested against controls.

CLEARED OF WOODY THICKETS

LAYER

SCRAPED

UNCLEARED OF WODDY THICKETS

Clearing Scraping Diaspore Burning

At each site, half of the 16 treatment units are positioned in areas that have been cleared of tall woody thickets. The heavy machinery used to clear woody thickets tends to leave woody material and leaf litter on site.

LAYER

Half of the treatment units were scraped with a back-end box blade to remove accumulated organic matter or duff.

Half of the treatment units were scattered with plant material containing diaspores, to assist with the establishment of wet prairie herbaceous plants. The other half will be allowed to naturally re-

REFERENCES

generate. Outside of the Southeast, diaspore transfer is a common practice for restoring prairies if a lack of naturally available seed is limiting the recovery of vegetation at a site.

BURNED OR UNBURNED

Half of the treatment units received prescribed fire. Fire is often employed as a restoration tool in forests and encroached wetlands across the southeastern US. In the western Florida Panhandle, research suggests that early-season fires were historically more common than late-season fires and fire intervals were approximately every 4 years. Fire decreases the growth of woody species and increases herbaceous cover. Regular, low intensity burns keep fuel loads low, thereby preventing dangerous, high intensity fires.

1. Ryan, K.C., Knapp, E.E. and Varner, J.M. (2013) Prescribed fire in North American forests and woodlands: history, current practice, and challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11: e15-e24.

2. Fowler, C., & Konopik, E. (2007) The History of Fire in the Southern United States. Human Ecology Review, 14(2), 165–176.

3. Platt, W.J., Orzell, S.L., Slocum, M.G. (2015) Seasonality of fire weather strongly influences fire regimes in South Florida savanna-grassland landscapes. PLoS One, 10(1).

4. Waldrop, T.A. & Goodrick, S.L. (2012, revised 2018). Introduction to prescribed fires in Southern ecosystems. Science Update SRS-054. Asheville, NC, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station.

conservation actions conducted where a threatened plant grows in the wild. Depending on the goals of a conservation program,

eastern United states, while the other is global, evaluating the state of international efforts to conserve magnolias worldwide.

by Jean Linsky GCC Magnolia Coordinator

by Jean Linsky GCC Magnolia Coordinator

The Southeastern Center for Conservation is the lead institution of the Global Conservation Consortium for Magnolia (GCCM). The GCCM is a network of botanical gardens and other conservation institutions that aims to prevent the extinction of magnolias, which comprise over 330 species globally. Two of the main objectives of the GCCM are to establish, expand and manage ex situ collections of high conservation value and to ensure effective in situ species conservation. In 2022, the GCCM released the Global Conservation Gap Analysis of Magnolia to provide guidance to the global community and to continue to catalyze activities for the species throughout their ranges in North and South America, the Caribbean and East and Southeast Asia. The gap analysis uses data from global databases such as Botanic Gardens Conservation International’s PlantSearch and a survey of the global botanic garden and conservation community to report detailed information on Magnolia species in institutional collections worldwide3. The gap analysis revealed that 50% of Magnolia species are present in botanical institutions, but each institution’s collection of any particular species can range from a single tree to dozens of individuals. The gap analysis also found that 98 threatened Magnolia species are completely absent from any ex situ collection. It also identified geographical areas that are under-represented in global conservation collections.

This GCCM publication presents regional prioritizations for species of conservation concern at the global level and will be used to guide the development of strategies as the Consortium expands. These collaborative publications are exciting additions to the development of gap analysis methods and provide information which will guide activities of our national and international networks for years to come.

50% (168 of 336) of Magnolia species are reported in ex situ collections. 98 threatened species from the categories CR-Critically Endangered, EN-Endangered and VU-Vulnerable are not reported from any ex situ collection. Other categories: NT-Near Threatened, LC-Least Concern, DD-Data Deficient.

The southeastern United States is a biodiversity hotspot – an area rich in unique habitats and plants that, because of anthropogenic influences and climate change, is at increased risk of loss. The region is home to over 11,000 native plant species, 30% of which are endemic4. The Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance (SE PCA) is a public and private partnership of professionals bridging gaps between local and national plant conservation efforts and collaborating to prevent and restore the loss of plant diversity in the southeastern United States. The SE PCA, in partnership with the Atlanta Botanical Garden, Botanic Gardens Conservation International, U.S. (BGCI-US) and NatureServe, developed a regional priority species list, followed by an ex situ collections gap analysis5

The regional priority species list was based on NatureServe’s extensive documentation of species geographical distributions and rarity across the United States. A species list was compiled for the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (SEAFWA) footprint of the Southeast, including these 15 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia. Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands were not included due to insufficient data, but will be incorporated in a future iteration of this work. A total of

The gap analysis revealed that the Southeast has done well in terms of ex situ collections of threatened plants. Of the 703 shortlisted “high priority” species, over half (382 species) are already present in at least one ex situ collection. Wild provenances for 223 (32%) species are reported but provenances for another 161 (23%) taxa in ex situ living collections are not reported. Knowing exactly wheere each collected plant comes from helps in evaluating how well a collection captures the natural variation in a species across its range and is also vital for reintroducing the plants or their offspring back to where they originally came from. A total of 158 institutions provided data for this analysis, half of which comprise institutions located within the United States. Our collective achievements and goals will guide ongoing efforts for the region and promote global standards for biodiversity conservation7. Based on this gap analysis, the SE PCA aims to secure the majority of rare plants of the Southeast in seed banks and living collections at various botanical institutions and implement recovery and restoration programs that support wild plant populations. The list of “high priority” species will now be developed into the ‘Southeast Plants Regional Species of Greatest Conservation Need list’, which will be the first of its kind that serves to align plant conservation with broader efforts to conserve

High priority taxa reported by 321 institutions in 36 countries

Wild-origin material reported by 77 institutions in 14 countries

4% of high priority taxa are held in ex situ living collections

80% held in the Southeast U.S.

75% are reported by seed banks

4% represented by 20+ wild-origin accessions

68% represented by zero wild accessions

308 43.8% 45.7% 9.8% 69

321

Number of wild-origin accessions

Number of wild-origin accessions reported for 223 Southeast U.S. high priority taxa of conservation concern, categorized by NatureServe Global Conservation Status Rank. Based on a 2020 list of high priority species of conservation concern6 and living collections data reported during an April 2021 ex situ survey of wild-origin accessions. *Please note that numbers of accessions greater than 50 have been cropped here to maximize data visibility.

REFERENCES

1. BGCI. 2017. Orchids: 2017 Global Ex situ Collections Assessment. Botanic Gardens Conservation International, U.S. Available from: https://www.bgci.org/resources/bgci-tools-and-resources/2017-global-ex-situ-collections-assessment-for-orchids/

2. Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Pivorunas, D., Hoban, S., & Westwood, M. (2021). Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Pines. Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum

3. BGCI. (2020). PlantSearch online database. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Richmond, U.K. Available at https://tools.bgci.org/plant_search.php. Accessed on 8 August 2020.

4. Noss, R., Platt, W. J., Sorrie, B. A., Weakley, A. S., Means, D. B., Costanza, J. K., & Peet, R. (2015). How global biodiversity hotspots may go unrecognized: Lessons from the North American Coastal Plain. Diversity and Distributions, 21(2), 236-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12278

5. Beckman Bruns, E., Coffey, E., Treher Eberly, A., Frances, A., Meyer, A., Radcliffe, C. (2022). Ex situ Gap Analysis of High Priority Plant Taxa of Conservation Concern in the Southeast U.S. San Marino, California: Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S.

6. NatureServe. (2020). NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available at https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed November, 2020.

7. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. (2016). North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation, 2016-2020. Illinois, USA: Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S. http://northamericanplants.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/NAGSPC.pdf

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is the most important legislation for the preservation of endangered species in the United States. Threatened species can be included and protected under the Act if they meet certain criteria and can conversely be delisted if the species is deemed to be secure following successful conservation interventions. In 2021, the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance (SE PCA) began a project that targets threatened plant species listed under the Act, with the goal of helping their recovery and eventually delisting from the Act. This project, titled “Improving Recovery Outcomes for the Endangered Species Act” involves numerous local and regional partners, including U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service recovery leads and administrators.

The project identified 13 high-priority federally listed plant species of the Southeast. The SE PCA’s primary objectives for these species include on-the-ground conservation actions (both research and management), education and outreach to partners and landowners, providing support to local Plant Conservation Alliances, building partnerships with public and private landowners and facilitating working groups and workshops. In 2020, the SE PCA and partners received funds for pilot conservation work on five of the project’s 13 focal species.

Trillium reliquum

Alabama: SE PCA provided funds to the Alabama Plant Conservation Alliance to protect this species from deer and feral hog damage, supporting Davis Arboretum at Auburn University to construct 50 dome-shaped exclusion cages to keep feral hogs at bay.

Georgia: Conducted population surveys on public lands.

South Carolina: The Center worked with the South Carolina Natural Heritage Program and the South Carolina Plant Conservation Alliance to secure access to the populations on private property, conduct population surveys and conduct invasive plant control.

The Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance (SE PCA) is a public and private partnership of conservation professionals that bridges gaps between local and national plant conservation efforts, so as to restore and prevent the loss of plant diversity in the southeastern United States. The SE PCA footprint covers 15 states and 2 territories. There currently are more than 120 members in the SE PCA, including government agencies, land managers, botanical gardens, university programs and other experts and professionals. Over 20 leaders comprise the steering committee, with over 50 task team members. The SE PCA is currently chaired by the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Southeastern Center for Conservation.

Varronia rupicola

SE PCA, through the Southeastern Center for Conservation, is supporting local conservation efforts for this species by partners such as Vieques National Wildlife Refuge, Vieques Conservation Trust and others. This is achieved through collaborative planning, developing conservation infrastructure and capacity, increasing plant material for experimental reintroductions and an outreach video documenting the conservation needs and successes for this species.

Schwalbea americana

SE PCA is working with The Jones Center at Ichauway, Longleaf Alliance and Emory University to develop predictive species distribution models to search for new populations and identify potential habitats across the southern portion of its range. Surveys have focused on the Carolinas and Georgia. In addition, seeds are being collected for safeguarding at the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Conservation Seed Bank.

Ribes echinellum

SE PCA is helping the Southeastern Center for Conservation and Emory University with demographic research to understand the ecology and unusual geographic distribution of this species. This work is in collaboration with the Florida Plant Conservation Alliance and South Carolina Plant Conservation Alliance. In addition, seeds are being collected for safeguarding and research at the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Conservation Seed Bank.

Platanthera integrilabia

Alabama: SE PCA organizations conducted population surveys across the Piedmont and Ridge & Valley of Alabama, collected seeds for seed banking distribution and conducted habitat restoration. This effort involved the Southeastern Center for Conservation, Auburn University’s Davis Arboretum and the Huntsville Botanical Garden’s Conservation Department. This will support conservation efforts

by landowners, such as Talladega National Forest, Skyline Wildlife Management Area and Mountain Longleaf Wildlife Refuge.

Rangewide: SE PCA is developing regional management guidelines based on the expertise and experiences of organizations that have been active in the conservation of this species, including the various botanical gardens, Plant Conservation Alliances and Natural Heritage Programs in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina and Tennessee.

Caitlin is based in Florida at Deer Lake State Park and her work is funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Caitlin helps to conduct restoration experiments in wet prairies and studies how restoration affects vegetation, hydrology, soil and herpetofauna (reptiles and amphibians).

Caitlin is pursuing a Master’s degree on the conservation of herpetofauna.

Cami is based in the Gulf Coast in the Florida panhandle, where she assists with rare plant surveys and demography studies, seed collections and vegetation assessments. She also helped conduct insect surveys at Deer Lake State Park. Cami has a BS in Cell & Molecular Biology from Auburn University. Her passion for the outdoors and protecting native ecosystems led her to pursue conservation work in the field.

Grant curates the Seed Bank at the Atlanta Botanical Garden. His research examines seed storage, viability and symbiotic germination. Grant earned his PhD in Botany from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, researching the genetics and fungal symbionts of endangered Florida Vanilla orchids. In his free time, Grant enjoys astronomy, gardening, hiking and going to the movies with his partner.

Jonathan has a passion for the intersection of technology and the natural world. His experience ranges from machine learning for wildlife detection to bioacoustic data analysis of bird calls. Jonathan helps to manage the flow and storage of the Center’s conservation and research data. He also helps conduct aerial drone surveys for rare plants and communities.

Maria assists the Vice President with a variety of routine and special projects and ensures the Center’s operations run smoothly. Maria holds a Masters in Botany with a certificate in conservation from Miami University, Ohio, where she specialized in using genetics to help inform plant conservation. Maria enjoys being active, meeting new people and the beauty of nature. She is excited to be a part of this team helping to conserve plants in the Southeast.

Sandee is originally from Connecticut and moved to Georgia 6 years ago, with 14 years of experience working with federal and non-federal grants. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Business Management and a Master’s degree in Pastoral Ministry. Sandee is married and has two sons. She is very excited to work with a wonderful team and to ensure the integrity of the Center’s grant management.

With a background in community ecology, environmental science and conservation, Sarah uses her experience facilitating conservation activities to serve the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance. Sarah has already helped to develop the first Regional Species of Greatest Conservation Need list for imperiled plants of the Southeast. Sarah enjoys fostering neonatal kittens, hiking, gardening and baking in her spare time. Sarah and her husband welcomed their first daughter in January.

Conservation

Will manages and maintains plant conservation collections at the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Midtown location. He also supports field research and conservation. Will received his BS in Horticulture from the University of Georgia and completed his MS in Horticultural Science at North Carolina State University studying plant breeding and cytogenetics. Will joins the team with several years of experience working with top botanical gardens from around the world.