Synecology

an annual publication of the Southeastern Center for Conservation

an annual publication of the Southeastern Center for Conservation

Reflecting on the achievements of 2024, we are reminded of the incredible strength found in collaboration and our shared commitment to a world where plant biodiversity thrives. This year, our partnerships, from local communities to international institutions, have proven invaluable in improving conservation outcomes. Achievements this year were not ours alone but were made possible by the vision and support of dedicated partnership networks.

One of the most rewarding aspects of the year was our participation in national and international conservation events. Hosting SePPCon at the Atlanta Botanical Garden brought together leading experts from across the southeastern U.S., energizing our regional network and advancing the mission of the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance. Our team also traveled to a National Science Foundation research mentoring symposium at the Morton Arboretum, the Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S. meeting at San Diego Botanic Garden, the International Orchid Conservation Congress in Perth, Australia, the International Botanical Congress in Madrid, Spain, and the Global Botanic Garden Congress in Singapore. Each gathering deepened our connections, broadened our perspectives, and reminded us of the global commitment required to address today’s urgent conservation challenges.

vanced research on cloud forests, building on a collaboration between The Lovett School and the local Ruiz family to create a haven for critical biodiversity. In North Carolina, we worked with stakeholders to protect the rare Schweinitz’s sunflower, and in partnership with the Catawba Nation, we supported efforts to preserve a culturally and ecologically significant species. In Costa Rica, we led a genetics workshop with Osa Conservation, equipping regional conservationists with cutting-edge skills to tackle pressing challenges. Across these initiatives, we underscore the importance of aligning science with the cultural and ecological nuances of each community we serve.

As we look ahead, we do so with renewed hope and determination, inspired by what we have achieved together and the potential that lies ahead. With the support of our partners and the strength of our global network, we are well-positioned to continue making strides in plant conservation. Every step we take is strengthened by the dedication of our partners and supporters, whose shared vision of a biodiverse world is our guiding light. To everyone who has joined us on this journey — thank you. Your dedication, knowledge and shared vision has been invaluable to our progress.

With deepest gratitude and warmest wishes for the year to come,

We have also deepened our impact through handson conservation projects, where collaboration drives meaningful action. Conservation is not only about safeguarding biodiversity but also about embracing cultural diversity and encouraging locally informed solutions. In Puerto Rico, we joined forces with partners to protect the endangered Puerto Rico manjack on Vieques, demonstrating how scientific rigor and community engagement are needed for lasting success. In Ecuador, our work at Siempre Verde has ad-

Emily Coffey, PhD Vice President, Conservation & Research Atlanta Botanical Garden

Atlanta

Mary Pat Matheson

Emily Coffey, PhD

The Anna and Hays Mershon Vice President

President & CEO

Loy Xingwen, PhD

Bo Shell Designer

Editor Bianca Glade Designer

Staff and Researchers

Cami Adams Field Biologist, EPA Florida

Laurie Blackmore, MSc Director of Applied Conservation

Tanner Biggers Conservation Horticulture Nursery Manager

Amanda Carmichael, MSc Conservation Genetics Laboratory Manager

Carson, MSc Senior Conservation Horticulturist

Kelly Coles, MSc Gulf Coast Coordinator

Caitlin Crocker Field Biologist, EPA Florida

Lauren Eserman-Campbell, PhD Research Scientist, Genetics

John Evans, MSc Conservation Horticulture Manager

Jonathan Gore Research Engineer

Dave Gregory Field Technician

Getty Hammer, MSc Field Biologist, GEBF

Dane Hulsey Administrative Assistant

Katherine Johnson Conservation Horticulturist

Amy Lee Executive Assistant to Vice President

Qiansheng Li, PhD Research Scientist, In Vitro

Jason Ligon Micropropagation & Seed Bank Coordinator

Jean Linsky, MSc GCC Magnolia Coordinator

Loy Xingwen, PhD Research Scientist, Ecology

Willow Mar Field Technician, Gulf Coast

Sarah Norris, MSc Conservation Partnerships Assistant

Sathid Pankaew Plant Digitization Assistant

Justin Peterman, MSc Conservation Horticulturist

Sandee Phillips, MA Grants & Contracts Analyst

Sally Phipps, MSc Consortium Outreach Coordinator

Carrie Radcliffe, MSc Director of Conservation Partnerships

Joe Stockert, MSc Field Biologist

Jeff Talbert, MBA Project Coordinator, GEBF Florida

Milo Vasquez Rare Plant RaMP Program Coordinator

Editor's Note

Celebrating Leadership Excellence – We’re thrilled to share that Vice President Emily Coffey was recently honored with the Center for Plant Conservation’s 2024 Star Award, a prestigious national recognition for her outstanding contributions to the conservation of imperiled plants. This award highlights the impact of Coffey’s vision, as well as the dedication of the entire team and our partners. Please join us in celebrating this remarkable achievement!

The Southeastern Center for Conservation humbly acknowledges the Indigenous Peoples and Tribal Nations of our focal region. We are working on the homelands of many Tribes and Indigenous Communities, and it is with gratitude and appreciation that we seek to conserve species and natural systems that were nurtured by those stewards possessing unparalleled relationships with these lands since time immemorial. The Center recognizes the many impacts of colonialism and the irreparable losses that have been endured by the region’s original inhabitants–including humans, animals, plants and stones–and the land itself. We aim to provide access to resources and opportunities for an informed alliance while we participate in building bridges, expanding perspectives, honoring Indigenous Knowledge, and weaving together our respective approaches.

To learn more about Tribes in the Southeast, visit the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Tribal Story Map (secasc.ncsu.edu/tribal-resources/) and the Native Land Digital (native-land.ca) interactive online maps. These are on-going works in progress that are not meant to represent official or legal tribal boundaries; to learn about definitive areas, please contact the nation(s) in question.

by Laurie Blackmore, MSc Director of Applied Conservation

Island species are often at high risk of extinction because of their unique adaptations to local conditions. The endangered Puerto Rico manjack (Varronia rupicola) is one such species, with only three small populations remaining on Vieques and Puerto Rico (U.S.), and Anegada (British Virgin Islands). On the island of Vieques, the species is especially vulnerable to threats such as habitat loss from development, invasive species and climate change.

In 2021, the Southeastern Center for Conservation, in partnership with the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance and funded by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (US FWS), launched a comprehensive conservation program to save the Puerto Rico manjack on Vieques. In addition to prioritizing the most at-risk population of this species, the project aims to establish a model for future reintroduction efforts on other islands.

Staff joined local organizations — the Vieques Conservation & Historic Trust, Ticatove and the US FWS Vieques National Wildlife Refuge (VNWR) — in their ongoing efforts to safeguard the remaining wild population's genetic diversity. When the Center came on board, the VNWR nursery had already cultivated many plants from wild seeds and cuttings, which were ready for planting back in the wild.

In October 2023, the team facilitated an experimental approach to outplanting to learn how to improve the success of future

reintroduction efforts. Nursery-grown Puerto Rico manjack plants were planted in a range of potential habitats. To identify optimal conditions, they collected soil samples from outplanting sites and the original wild location. Thanks to innovative drip irrigation devices developed by the partners, 90 percent of the outplants survived after eight months. To refine propagation methods without risking wild seeds, the team worked with Fairchild Botanical Garden to obtain seeds from its seed bank. By carefully timing seed sowing to mimic natural conditions, nearly 70 percent germination was achieved, with some plants already reaching two feet tall — a testament to this species' will to survive.

Looking ahead, the team will continue to monitor plant survival and growth in relation to soil and other site conditions while refining propagation protocols. To conserve genetic diversity more effectively, it will grow plants from seeds whose origins are carefully tracked back to their mother plants. This method, called maternal line tracking, ensures that it captures and maintains a broad range of genetic lineages within plant conservation collections collections, forming a stronger foundation for future reintroduction efforts. The Center is also deepening its partnerships on Vieques by fostering conservation strategies through an exchange of knowledge and local insights. Together, the goal is to build sustainable efforts to protect the Puerto Rico manjack and other threatened species in the region.

by Jason Ligon Micropropagation & Seed Bank Coordinator

If two minds are better than one, imagine combining the expertise of more than 800 botanical gardens across 118 countries to tackle the biodiversity crisis. With two out of five plant species at risk of extinction, the world's largest plant conservation network, Botanical Garden Conservation International (BGCI), leads the charge. While collaboration among botanic gardens is crucial, conserving rare plants requires support from conservation-minded landowners and managers.

This is why BGCI partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service (USDA FS) to create funding opportunities for joint conservation initiatives.

Through this partnership, the Southeastern Center for Conservation secured funding for two projects with the USDA FS, with whom it has collaborated for more than a decade. Both projects focus on seed banking species with narrow geographic ranges, which are particularly vulnerable to extinction. Seed banking preserves genetic diversity, and the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Conservation Seed Bank, one of the Southeast's largest, now holds more than 4,855 accessions from 542 taxa.

"the Garden’s Conservation Seed Bank, one of the Southeast's largest, now holds more than 4,855 accessions from 542 taxa."

The first project, funded in 2023, supported the seedbanking of the critically endangered Balsam Mountain gentian (Gentiana latidens) from North Carolina’s Pisgah National Forest. Center staff were able to map out this species' range and collect 5,100 seeds from 51 mother plants. When dried to 3-7% moisture content, the seeds showed no reduction in seed viability compared to controls, suggesting they are orthodox. Orthodox seeds can survive drying, which makes them easier to store long-term.

The second project, funded in 2024, focused on three orchids unique to Puerto Rico: Luquillo Mountain baby boot orchid (Lepanthes eltoroensis), rock baby boot orchid (L. rupestris), and Woodbury's baby boot orchid (L. woodburyana). This project takes place at El Yunque National Forest – Puerto Rico’s only national

forest. Thanks to the Center’s dedicated USDA FS partners, staff added Woodbury's baby boot orchid seeds to the seed bank and started germination trials. Plans are under way to collect seeds from the other orchid species.

Seed banking is a cost-effective conservation strategy, but it is only the beginning. The future of these species hinges on deepening our understanding of their genetic diversity. In both projects, leaf tissue was collected from each plant that provided seed to prepare for future genetic studies that will inform smarter conservation strategies. Moving forward, the Center’s collaboration and shared goals with esteemed and long-standing partners like the USDA FS will be paramount in ensuring these species not only survive but thrive for generations to come.

Conservation partners take action to safeguard Schweinitz’s sunflower

by Joe Stockert, MSc GCC Magnolia Coordinator

Cycles of disturbances — from natural fires and windstorms to agriculture and settlement — have continuously shaped the Southeast’s vegetation communities. In the Carolinas' Piedmont region, wild and cultural fires historically maintained forest gaps to support grasslands akin to prairies of the American Midwest. These so-called 'Piedmont prairies', however, are becoming increasingly rare.

One particular type, the Southern Prairie Barren, is a critically imperiled vegetation community unique to the Charlotte metropolitan area. It is home to rare plants like the Carolina-endemic Schweinitz’s sunflower (Helianthus schweinitzii), which faces extinction as its habitat vanishes.

Today, more than 90 percent of Schweinitz’s sunflower populations are found on roadways and along powerlines, where maintenance machinery keeps woody vegetation in check, inadvertently creating prairie-like conditions. But the future of these fortuitous surrogate habitats is not guaranteed. In fact, a sunflower population was recently rescued from certain death because of road development. The plants were saved by conservation partners from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, the Catawba

"90 percent of Schweinitz’s sunflower populations are found on roadways and along powerlines"

Nation, the North Carolina Botanical Garden (NCBG) and Winthrop University. Many of the rescued plants are being replanted on Catawba Nation land as part of an effort to restore the region’s historic prairies. Relocating plants for conservation is a last resort because of the difficulties in ensuring their survival in new environments and the labor involved. Yet, these efforts hold immense value, not just for preserving the species' genetic diversity but also as symbols of meaningful conservation action.

The Southeastern Center for Conservation, funded by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance (SE PCA), is adding Schweinitz’s sunflower to its conservation collections. In 2023, the Center surveyed 18 recorded sites in South Carolina but found the species at only seven. In North Carolina, staff visited six populations. Seeds were collected from all sites in both states for seed banking. These will be shared with the North Carolina Botanical Garden to help establish a more robust metacollection within the SE PCA. Next, the Center will assist the Catawba Nation in developing propagation methods and planning future outplantings in the wild.

by Jean Linsky, MSc GCC Magnolia Coordinator

Sally Phipps, MSc Consortium Outreach Coordinator

Botanical garden collections are vital to conserving endangered plants. High quality conservation collections safeguard wild genetic diversity, making plant material available for reintroduction and research.

However, capturing this full genetic diversity often requires maintaining hundreds of plants of a single species, which can be a challenge for individual gardens. Metacollections address this by distributing plants across multiple gardens, allowing institutions to share resources and reducing the risk of losing an entire collection due to damage at any site. To make metacollections effective, gardens need tools that facilitate data analysis and sharing across institutions.

The Global Conservation Consortium for Magnolia (GCCM) is helping gardens implement metacollections for threatened magnolia species. As the leading institution for the GCCM, the Southeastern Center for Conservation has undertaken a multiyear project funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, in collaboration with Botanic Gardens Conservation International and the Global Conservation Consortia for Oaks and Cycads. A key part of this initiative is developing GAMMA. This web-based application simplifies the process of analyzing the conservation value of collections, removing the need for specialized expertise in statistical programming. The Center introduced GAMMA to an international audience at a virtual workshop in May

2024, which drew enthusiastic feedback. Staff are continuing to enhance the tool’s capabilities and accessibility.

In addition to helping develop digital tools, the Center provides on-the-ground support to other partners within the GCCM. In March 2024, funded by the Walder Foundation through a grant awarded to Chicago Botanic Garden, staff traveled with them to visit partners in Ecuador, including the Jardín Botánico Padre Julio Marrero (JBPJM), Fundación Jocotoco, and Reserva Tesoro Escondido. Staff at JBPJM have successfully cultivated critically endangered Magnolia canandeana and M. dixonii from wild-collected seeds. As a GCCM partner, the Center supported the collection of nec-

The Global Conservation Consortium for Magnolia (GCCM) is one of several consortia initiated by Botanic Gardens Conservation International. With half of the world’s magnolia species globally threatened with extinction, the GCCM is a network of institutions and experts collaborating to prevent the extinction of magnolias worldwide. Launched in 2020, the GCCM is currently led by the Southeastern Center for Conservation and has grown to include 64 participants across 20 countries. For more information, visit globalconservationconsortia.org

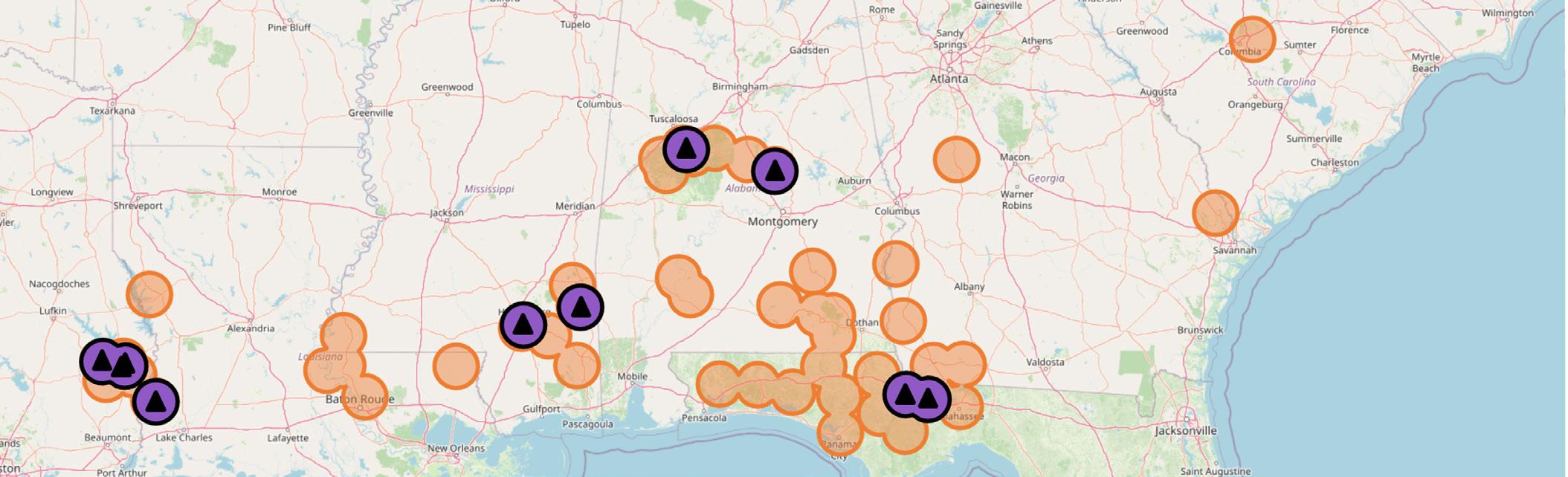

Screenshot of the GAMMA web interface, a tool to support conservation strategy for ex situ collections. Orange circles represent occurrences of Magnolia pyramidata from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility with a 20 km buffer. Purple circles indicate geo-referenced provenance of global ex situ collections. Black triangles represent collection sizes, with all shown here containing 5–15 individuals.

essary conservation data and leaf tissue samples to assess the genetic diversity of wild populations and cultivated collections. At an international symposium on plant conservation, Center staff led workshops on data standards and tools for metacollection management. Plans are under way to establish metacollections for M. canandeana and M. dixonii across Ecuadorian gardens.

Looking ahead, the GCCM aims to continue to support the establishment of metacollections worldwide to enhance the conservation of threatened magnolia species, empowering gardens of all sizes to contribute to safeguarding plant biodiversity.

by Yaneth Vazquez Jacinto

Master’s Student Researcher

Cloud forests are extraordinary tropical ecosystems. At elevations of about 10,000 feet, the rich plant diversity found there is adapted to cool temperatures and nourished by near-constant cloud cover. Yet these unique conditions make cloud forests highly sensitive to shifting temperatures and rainfall patterns caused by climate change.

Siempre Verde, a forest preserve nestled in the Cotacachi volcano foothills, is a hub for cloud forest education, conservation and research.

Established by the local Ruiz family and Atlanta’s The Lovett School, this unique facility was a home base for my Master’s degree field research.

My Master’s thesis echoes a previous study conducted in 2014 by scientists who sought to understand how elevation shapes the types of trees found in Siempre Verde’s cloud forests1. This year, we visited 23 of the original study plots to examine how the forests have changed in the last decade. Understanding how forests are changing over time is essential for predicting the effects of climate change and devising effective conservation measures.

Fieldwork was long and challenging. The field team included Southeastern Center for Conservation staff Emily Coffey, Syliva Seger, Joe Stockert and Kelly Coles, with support from students and staff from The Lovett School and the Ruiz family. Teams of four to five worked to locate the decade-old study plots and set up new ones. We tagged, identified and measured the size of every tree within each plot with a trunk diameter at breast height greater than 5 cm. We also collected and pressed specimens from trees we could not identify in the field. I then brought the specimens to the herbarium at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, where I worked with my local co-adviser, Álvaro Javier Pérez Castañeda, to identify them to species. My next steps will be to analyze the data with help from the Center’s research ecologist, Loy Xingwen.

PRELIMINARY RESULTS: How tree diversity changes with elevation in 23 forest plots. Each dot shows a forest plot surveyed twice, ten years apart. The top graph shows how the number of tree species changes over time, with elevation (linear model). The bottom graph shows patterns in Simpson’s index, a diversity metric that reflects species balance (quadratic model).

Preliminary results reveal no increase in tree species per plot over the past 10 years. However, the balance in the abundance of different species declined, particularly at the highest and lowest elevations. I will continue analyzing the data to explore whether these patterns are because of new species moving into the study area, species dispersal among plots or other factors.

I hope my research will help shape future conservation strategies and provide insights into how cloud forests respond to the pressures of climate change.

7,92310,938 ft. trees tagged & measured 1058 tree species identified 148

field days 29 study plot elevations

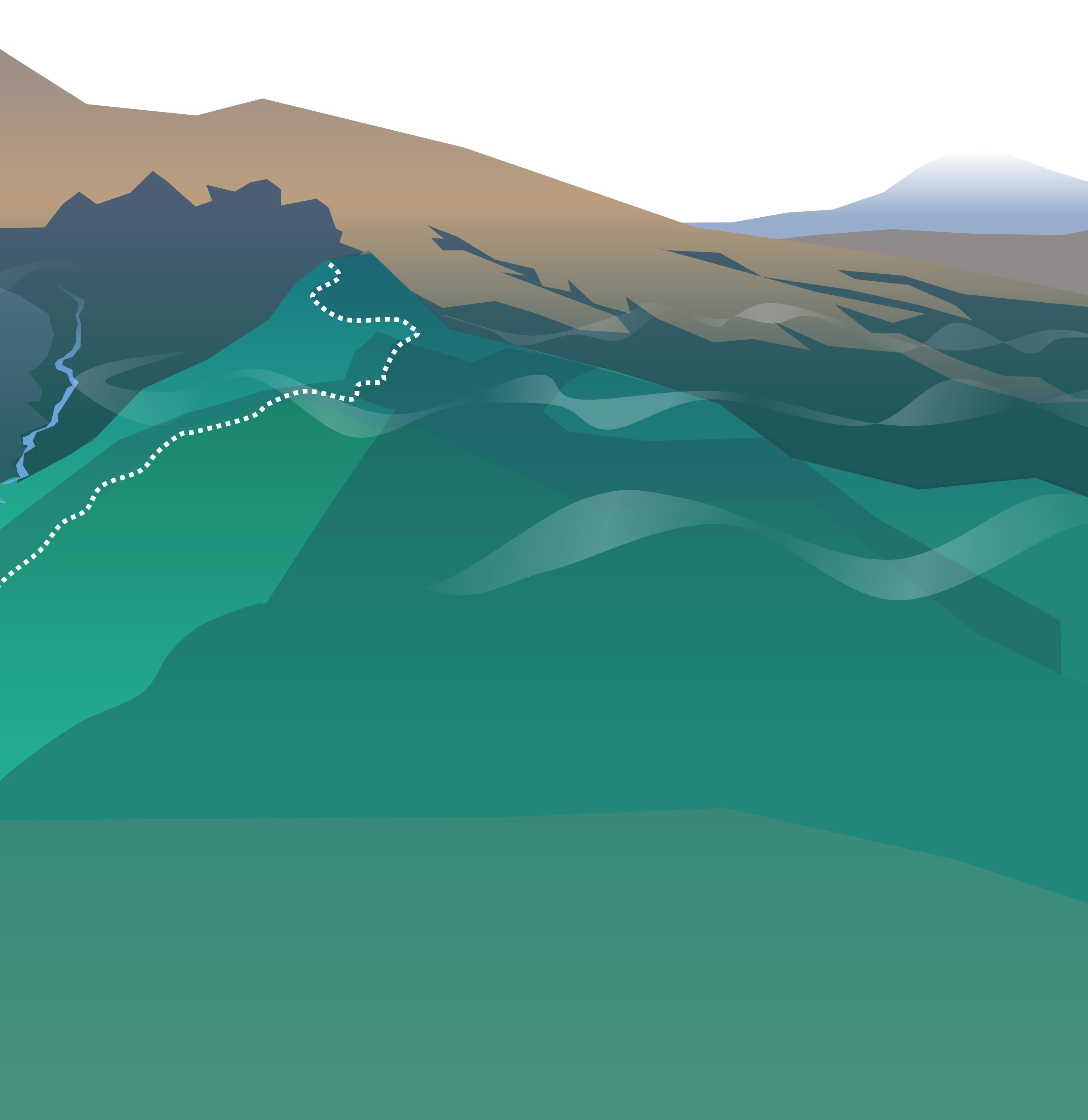

PARAMO GRASSLAND

> 11,500 feet elevation

Too windy and dry for dense forests, here the vegetation is composed mainly of grasses and shrubs.

UPPER MONTANE CLOUD FOREST

10,100 - 11,500 feet elevation

Cold temperatures, high winds, and low rainfall keep the trees stunted and less than 15 m tall. Constant mist and fog allow mosses and lichens to cloak tree branches.

TRANSITIONAL ZONE

8,800 - 10,100 feet elevation

The region between upper and lower montane forests contains a mix of species from both habitats and thus often contains the highest species diversity.

LOWER MONTANE FOREST

7,500 - 8,800 feet elevation

High rainfall and warmer temperatures support towering trees and riparian species. This region is more altered by human activities like agriculture.

SIEMPRE VERDE

PRESERVE & RESEARCH CENTER

Located on the slopes of Ecuador’s dormant Cotacachi Volcano, Siempre Verde has 7 trails. The longest, the Ariba Trail, runs for only 2.7 miles but gains 4000 feet in elevation.

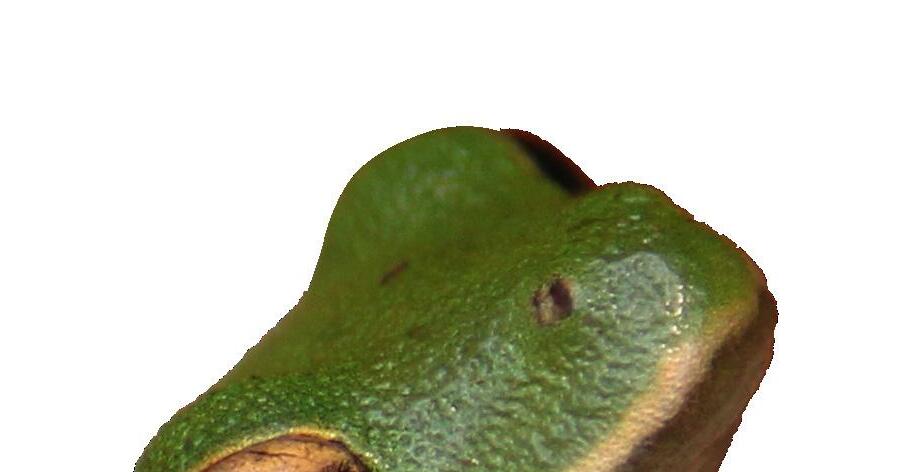

RICH FLORA & FAUNA

Siempre Verde is home to an immense and unique variety of plants and animals, including 308 taxa on the IUCN Red List, with 48 listed as vulnerable, 8 endangered, and even a rediscovery of a species previously thought to be extinct. Rare animals, such as the plate-billed mountain toucan, olinguito, and fern-loving rain frog, are frequently seen.

by Loy Xingwen, PhD Research Scientist, Ecology

In 1990, Bob and Connie Braddy, both Lovett School science teachers, visited Ecuador to study the Andean cloud forests. Passing through Santa Rosa in the Imbabura Province, they found a school in disrepair. With The Lovett School's support, they raised funds to help rebuild it, sparking a lasting bond with the local community.

Two years later, Lovett strengthened that connection by creating Siempre Verde, a protected cloud forest preserve for conservation, education and research that now covers 1,245 acres and is recognized by the Ecuadorian government as a Bosque Protector, the highest designation for private protected forest reserves.

Today, Siempre Verde is a hub for U.S. and Ecuadorian students to study conservation, conduct research and support the local community through service projects. Its facilities include dormitories, a dining area and a large laboratory. Managed by Nelson and Mari Ruiz, whose local expertise and hospitality enrich visitor experiences, the preserve encourages ecotourism and sustainable practices to protect the forest.

Over the past decade, a partnership between The Lovett School and the Atlanta Botanical Garden has grown significantly. Orchids, a symbol of Ecuador’s rich biodiversity, were a key research focus. Staff worked with Lovett students to collect orchid DNA samples to better understand the region’s orchid diversity. Their most recent studies track tree communities along an elevational gradient, providing insights into climate change's effects.

Siempre Verde is a living example of how education and conservation can work together. The continued commitment of The Lovett School and its partners helps ensure that Siempre Verde remains true to its Spanish name “forever green.”

COTACACHI VOLCANO Imbabura, Ecuador 16,220 feet

SIEMPRE VERDE PROJECTS 11,400 feet

ABOVE AND BEYOND

ROAN MOUNTAIN North Carolina, USA 6,277 feet

RARE PLANT MONITORING 6,260 feet

EL TORO PEAK Puerto Rico, USA 3,524 feet

ORCHID GENETICS & SEED BANKING 3,018 feet

The effects of global warming are often first felt in the mountains. Studying high elevation ecosystems allows scientists to anticipate future climate changes. The Garden’s Southeastern Center for Conservation works in three high elevation regions in the Americas: the Andes, the Southern Appalachians, and Puerto Rico’s Luquillo Mountains.

by Loy Xingwen

Herpetofauna are bioindicators of wetland restoration success in Florida

by Caitlin Crocker Field Biologist, EPA Florida

PRELIMINARY RESULTS: How herpetofauna diversity varies at Deer Lake State Park. Rarefaction curves help compare species diversity while accounting for differences in the number of surveys or individual animals observed. Solid lines represent observed species richness, while dashed lines predict total richness if more samples were collected. Shaded areas show 95% confidence intervals, indicating the range of possible values.

Amphibians and reptiles, collectively known as herpetofauna, are valuable indicators of ecosystem health. As different amphibian species vary in their sensitivity to water and air pollution, the composition of amphibian communities can reflect environmental conditions. Additionally, herpetofauna such as snakes are important members of ecosystem food chains, preying on small animals while being prey for larger predators. Diverse and abundant populations of herpetofauna often indicate robust predator-prey dynamics in ecosystems.

The North American Coastal Plain, especially the Florida Panhandle, is rich in herpetofauna and ranks among North America's top five biodiversity hotspots. The region’s wet prairies are home to numerous rare or endangered species but are threatened by shrub encroachment, fire suppression and coastal development.

The Garden’s Southeastern Center for Conservation, with a grant from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), has partnered with the Florida Park Service and the University of Florida to address these challenges. In the last decade, 310 acres of wet prairie at Deer Lake State Park in Wal-

ton County, Florida, have been restored by mechanically removing encroaching shrubs and reintroducing fire.

Environmental monitoring studies are showing promise. In an ongoing project, we are examining how herpetofauna re spond to different wetland restoration techniques, such as shrub clearing, pre scribed burning and scraping away duff (the layer of shrub leaf litter that alters soil nutrients, suppresses prairie plants and can hinder prescribed burns without providing meaningful wildfire prevention). To measure herpetofauna abundance and species diversity, drift fences, coverboards and PVC pipes were used to safely trap and release animals after data collection. Nighttime spotlight searches and frog call surveys also were conducted.

So far, an impressive 53 herpetofauna species have been identified across 12 sites. Early findings show that resto ration efforts are working – after 2 years, restored wet prairie sites now support more species, comparable to nearby healthy ‘reference’ wet prairies. However, while removing duff may benefit

prairie plants, it could temporarily disrupt herpetofauna populations.

This data will continue to be collected and analyzed to determine how specific restoration methods benefit different species. This

by Carson, MSc Senior Conservation Horticulturist

When you picture Panama City Beach, what comes to mind? Perhaps sprawling beachfront resorts, crowded shores dotted with colorful beach towels or the annual influx of spring breakers immersed in merrymaking rituals. This seems hardly the place to look for rare wildflowers.

Yet in this bustling coastal landscape, on low sand ridges near the Gulf of Mexico, the threatened Telephus spurge (Euphorbia telephioides three counties of the Florida Panhandle.

Recently, one population in Bay County faced impending annihilation from plans to expand a roadway. Between October 2021 and March 2022, Southeastern Center for Conservation staff and Kelly Mandello of Cordgrass Consulting conducted emergency rescue operations. The group carefully relocated 63 plant individuals to the Garden’s Conservation Greenhouse in Atlanta.

The Center’s conservation horticulturists diligently cared for these plants in captivity, closely observing

by Lauren Eserman-Campbell, PhD Research Scientist, Genetics

The Rare Plant RaMP Network, funded by the National Science Foundation, offers individuals with a baccalaureate degree a one-year intensive research opportunity to gain experience in plant conservation. This program is a partnership among four gardens: Atlanta Botanical Garden, California Botanic Garden, Morton Arboretum and San Diego Botanic Garden. Each of the four partner botanic gardens hosts two mentees annually in this three-year mentorship program.

In the program’s first year, the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Southeastern Center

for Conservation welcomed Barbara Garfinkle and Max Meader.

Garfinkle’s research focused on the endangered Florida torreya (Torreya taxifolia), a critically endangered conifer endemic to Florida's panhandle. Since the early 1900s, its population has plummeted from 800,000 individuals to around 1,000 today. A major cause of the decline is a fungal pathogen identified as Fusarium torreyae. Garfinkle aimed to assess whether fungicides or biocontrol agents could limit the pathogen's spread and determine if other

tree species are vulnerable. She successfully conducted in vitro fungicide trials and started a greenhouse study, inoculating different tree species with the fungus.

Meader’s project focused on identifying orchid mycorrhizal fungi in the roots of the endangered white fringeless orchid (Platanthera integrilabia). In nature, orchid seeds require specific fungi to germinate. While seeds can be grown without fungi in the lab, experimental outplantings show that plants grown without these fungi struggle to survive

in the wild. Meader isolated DNA from fungal cultures collected from wild orchid roots. He used PCR with ITS primers and sent samples for Sanger sequencing to identify mycorrhizal fungi.

The remarkable work by Garfinkle and Meader will aid in the recovery of some of the Southeast’s most imperiled plant species. As they embark on the next steps in their careers, the Center looks forward to hosting two new mentees in the second year of the Rare Plant RaMP Network program.

by Amanda Carmichael, MSc Conservation Genetics Laboratory Manager

Lauren Eserman-Campbell, PhD Research Scientist, Genetics

Last summer, staff traveled to Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula to teach conservation genetics as part of the new “Tropical Tree Conservation Field Course” for early-career conservationists. The course was launched by Osa Conservation, a local non-profit organization whose mission is to conserve the globally significant biodiversity of southern Costa Rica through ecosystem stewardship, providing education and training, and creating sustainable economic opportunities.

The course was held at Osa Conservation’s Conservation Campus, in collaboration with Botanic Gardens Conservation International and Morton Arboretum, with support from the Franklinia Foundation. It was attended by nine early-career conservationists from the United States, Costa Rica and Peru, and offered handson training in conserving endangered tree species in Central America, focusing on ways to build climate resilience in tree conservation.

Center staff led a seven-hour session on conservation genetics, introducing its importance in addressing conservation issues and discussing lab methods for genetics research. Based on a pre-training survey, many students did not have previous experience with conservation genetics. However, they quickly developed skills through case studies, hands-on data analysis in R statistical software and exercises in designing and budgeting genetic studies.

With most students speaking primarily Spanish, Osa Conservation staff members Rodrigo de Sousa and Maria José Mata Quirós translated the lessons. The students asked insightful questions that sparked important discussions on using genetics to inform conservation actions. The Center staff received positive feedback on the practical focus of the training and were impressed by the students' enthusiasm. We are grateful to Osa Conservation for this opportunity and look forward to future partnerships.

by Sarah Norris, MSc Conservation Partnerships Assistant

Carris Radcliffe, MSc Director of Conservation Partnerships

The Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance (SE PCA) is committed to facilitating effective and inclusive plant conservation among diverse stakeholders to create national impacts. This goal was the central focus at the Southeastern Partners in Plant Conservation (SePPCon) 2024 Conference, held last October at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

The Center and its partners coordinate the SE PCA and SePPCon, which provided unique opportunities for in-person interactions among diverse conservation partners. The event kicked off with workshops focused on novel technologies and methods in plant conservation. Participants explored topics like remote-sensing data and drone use in habitat monitoring, conservation horticulture, seed bank curation and standard metrics for assessing plant rarity. SE PAC co-chairs Emily Coffey and Carrie Radcliffe welcomed attendees and set the tone for continuing to address global conservation needs through expanding partnerships and perspectives. Each day was launched by keynote speakers, including Reed Noss, Kayri Havens and Jared Margulies.

The conference featured 74 presentations following three themes: In situ Conservation, Ex situ Tools and Advocacy and Planning. Topics included research, new species described, conservation efforts for culturally significant species like rivercane, novel technologies and database development. State programs credited past SePPCon events and the use of SE PCA resources as inspirations in their progress toward incorporating plants into wildlife action plans. Tribal Nation representatives delivered moving and humbling presentations emphasizing that conservation is incomplete without centering the voices of displaced communities, addressing their cultural losses and restoring access to traditional resources. Breaks between sessions, evening receptions and a session with 26 posters allowed for networking, relationship building, and knowledge sharing.

SePPCon 2024 was a resounding success, with more than 230 participants from 15 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Attendees included representatives from natural heritage programs, various levels of government, Tribal Nations, and universities as well as student, private and professional botanists. With a record number of attendees and the development of new working relationships, more success is expected on the horizon. Partners are already looking forward to the next SePPCon gathering as its network continues to grow in participation, scope and impact.

DIAMOND SPONSORS

BAND Foundation, Atlanta Botanical Garden

GOLD SPONSORS

Bartlett Tree Experts, Georgia DNR

SILVER SPONSORS

Center for Plant Conservation, Missouri Botanical Garden, Tennessee Valley Authority

COPPER SPONSORS

TN Department of Environment & Conservation, Georgia Native Plant Society, Virginia Native Plant Society, Auburn University College of Sciences and Mathematics, State Botanical Garden of Georgia at the University of Georgia, Wild Ones MidSouth, Georgia Power, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Southeast Conservation Corps

Join us in advancing plant conservation and protecting biodiversity. Scan the QR code to support the Southeastern Center for Conservation. Every contribution makes a difference.

Synecology is an annual year-end publication by the Southeastern Center for Conservation at the Atlanta Botanical Garden. 1345 Piedmont Ave. NE, Atlanta, GA 30309