Mankind’s obsession with the macabre is as old as art itself. Whether in ghastly folklore or dark literature, horror stories have always been able to capture the attention of their readers, creating a kind of infatuation with the macabre. But although attraction to the dark has been prominent for decades, attitudes towards and portrayals of the grotesque have shifted over time. Perhaps the way in which they’ve changed says something about the world we live in, and unveils the way we view that which is different from us.

A master of horror, Edgar Allan Poe is one of the most eminent, and possibly earliest, horror novelists. A modern comparison, who is a paragon of successful horror writers today, is Stephen King—one of the most compelling writers of our time. While both authors focused their writings primarily on the grim and frightening, their works have not been equally successful. For instance, while Stephen King is currently worth $400 million, most of Edgar Allan Poe’s writings sold for no more than 9 to 15 dollars during his lifetime. In fourteen years of publishing tales, Poe made an approximate of $6200, which caused him to lead a rather penniless life. I believe that the reason behind such difference in popularity is mainly due to the approach each author had to the genre of horror, and not merely due to the difference in era.

Although horror stories had already begun gaining popularity when Poe first started writing, early critics of his work argued that he had produced the best horror stories of

his time. On the other hand, some critics argued that Poe’s works were too eerie and unsettling, making them onerous to read. For instance, in his story The Pit and the Pendulum, Poe describes the process of the mental torture of an imprisoned man. The tale shows the prisoner saving himself from death, only to be threatened by a new and more terrible mode of death, a pendulum threatening to slice him in half. In another story, The Masque of the Red Death, Poe describes a masked figure wreaking havoc on noblemen at a masquerade ball, eventually killing every last one of them. The masked figure was used to symbolize a grotesque form of death which spares no one, even those who think they’re protected. Poe described the “Red Death” as attacking people and causing them to bleed from all their pores—a description which may have been too gruesome for some. In fact, one anonymous critic in the Boston Notion newspaper stated that Poe’s work was “better suited for readers of the future.” The critic called Poe’s collection of short stories, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, “below the average of newspaper trash... wild, unmeaning, pointless, aimless... without anything of elevated fancy or fine humor.” Despite such harsh critiques, Poe’s stories continue to be admired and read profusely to this day.

During his lifetime, many argued that Poe’s writing fell outside the norm of American literature at the time. Taking it a few years into the future, fascination with horror stories came again in the late 20th century

Writer: Arwa Hezzah Editor: Alex Ben Ghanemwith writers like Stephen King. King, who appeared almost a century after Poe’s death, had a different approach when it came to writing horror. He graduated from the University of Maine in 1970 and began his writing career almost immediately after. His novel Carrie was accepted by the publishing house Doubleday in 1973. Although it was the fourth novel he’d written, it was his first one to get published. The story tells of a young girl with telekinetic powers, who kills almost her entire town after being subjected to bullying from her school mates. It was an instant hit and King’s career skyrocketed afterwards. His early works such as Salem’s Lot and The Shining gained him popularity and money very early on in his writing career.

Stephen King’s popularity continued well into his career. He expanded his writing to include genres like fantasy and supernatural fiction. In total, King has published 61 novels, with his books selling over 350 million copies worldwide. In addition to that, many of his books have been adapted into movies, television series, and even comic books. When compared to Poe in this respect, it is quite evident that King has had far more success with his writing than Poe did. Could the reason be that one of them is simply a better writer? Or does the reason behind such a momentous discrepancy lie somewhere else?

While both writers are similar in many respects, they both approached writing about the terrifying differently. Their similarities lie in their explorations of the dark side of human nature as well as their suspenseful stories focused on psychological discomfort. Despite that fact, there remain undeniable differences in their approaches. Poe’s work was a lot more focused on painting a picture of the dark and macabre, with his stories mostly taking place in some ominous setting or another. King, on the other hand, sets his stories in real-world areas, keeping them mostly grounded in reality.

Perhaps one of the reasons why King’s works are far more popular than Poe’s is the fact that he allowed his readers to relate more to his stories by keeping the line between reality and fantasy intact. It could be argued that Poe simply dove too far into the world of fantasy, keeping a gap between the readers and his writing. Poe tended to start his stories out in a dark, grim setting with the main character already, more or less, detached from reality. There always seems to be a glimpse of another world in Poe’s stories right from the start. While this could have appealed to many, it might have made it a little more difficult to relate to his tales of terror. King, on the other hand, almost always sets his stories up in your average American town, revolving around your normal, everyday family, with everything seemingly being alright. Afterwards, he begins to add elements of horror which make the story more and more frightening as it progresses. This was a large reason why King was able to attract such a large audience: he was able to suck people into the story, allowing them to relate to the characters, before adding the frightening elements. Not only did that let readers connect with and get attached to the story’s characters, but it also gave them a chance to see little glimpses of reality within the fiction. Additionally, King gives his readers the chance to tell reality from fantasy. His supernatural elements are clearly so in his stories, while, with Poe, it sometimes becomes difficult to tell what is real and what isn’t.

Although both writers have managed to keep their readers engaged with their literature, the styles of their writing along with the time in which they became popular contributed greatly to their success. Nonetheless, it is undeniable that King and Poe still remain iconic writers of horror, whose stories will continue to live on for centuries to come.

Ṭahāra in Islam; “Keep yourself pure,” Timothy 5:22 in the Bible; Sufism coming from ‘safa’ which means purity. Safa is an ongoing theme in Sufi practice; it is the state of heart - if we might say - of a true believer, free of hatred, jealousy, evil, and sin. Even Astrea was the Greek virgin goddess of Justice and Purity. Purity cannot be separated from religion; it describes it, inhabits it, and instructs it to its believers. A pure person free of worldly faults is inevitably a good person. Religious purity, however, is not just an idea. It is physical, as in cleanliness and beauty, emotional when it comes to compassion and altruism, and also mental, to the extent of questioning seen as an impurity in itself and is therefore condemned. Because what pure person would question the divine purity of the universe?

Ṭahāra in Islam; “Keep yourself 5:22 in the Bible; Sufism coming from safa’ which means purity. Safa is an ongoing in Sufi practice; it is the state of heart - if we might say of a true free of hatred, jealousy, and sin. Even Astrea was the Greek goddess of Justice Purity. cannot be separated from religion; it it, inhabits it, and it to believers. A pure person free of worldly is inevitably good person. Religious purity, however, is just an idea. It is physical, in cleanliness and beauty, when it comes to compassion altruism, and also mental, to the extent of seen as an impurity in itself is therefore condemned. what person would question the divine of the universe?

Rituals are the “method” or the mechanism of practicing religion. Going to places of worship, praying, reading, or meditating; all these rituals bring us closer to purity, or the beautiful Arabic word used in Islamic preachings called Sakinah Sakinah means tranquility or peace. This state and feeling of reassurance is mentioned in the Quran in more than one instance to describe a Godsent feeling that washes over believers in moments of vulnerability or challenge. A similar Buddhist notion is presented in the word Passaddhi, meaning tranquility of

are the “method” the of religion. Going to places of worship, praying, reading, meditating; these rituals bring closer to purity, or the beautiful Arabic word used in Islamic called means tranquility peace. This state and of is mentioned in the in more one to describe a Godsent that washes over believers in of vulnerability or A Buddhist notion is presented in the Passaddhi, meaning tranquility of

the body and mind. Passaddhi is the path to enlightenment, which leads to “release from suffering.” Purity here exists through the idea of reassurance and trust in peace following obstacles.

the body and mind. Passaddhi is the to enlightenment, which to “release from suffering.” here exists the idea of reassurance and trust in peace following

Assuming synonymous relation purity religion produces a natural binary: purity/pollution. Guilt stigma follow religiously raised people who away from the religion, succumbing to the contaminated of sin. This brings in the concept of Catholic guilt, particularly popular in American pop culture as a disapproving reaction to Catholic ethics. Its extreme form is scrupulosity, is characterized pathological guilt about religious issues. When we imagine a world without rules purpose think of chaos and Even if that idea entirely factual, it however provide purpose. This notion is also supported by sociologist Peter L. Berger, who believed that religion a human attempt to maintain social order in a chaotic world and ascribe meaning to humanity.

Assuming a synonymous relation between purity and religion produces a natural binary: purity/pollution. Guilt and stigma follow religiously raised people who stray away from the religion, succumbing to the contaminated world of sin. This brings in the concept of Catholic guilt, particularly popular in American pop culture as a disapproving reaction to Catholic ethics. Its extreme form is scrupulosity, which is characterized by pathological guilt about religious issues. When we imagine a world without rules and purpose we think of chaos and violence. Even if that idea isn’t entirely factual, it does however provide purpose. This notion is also supported by sociologist Peter L. Berger, who believed that religion is a human attempt to maintain social order in a chaotic world and ascribe meaning to humanity.

Humans naturally we need facts answers; the unknown is not a comfortable for us. In a research study published in the Journal of Personality and Social , research found that individuals who are religious, therefore in

Humans are naturally curious; we need facts and answers; the unknown is not a comfortable place for us. In a research study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, research found that individuals who are religious, and who therefore believe in

an external superior being’s control over their lives, tend to have a higher sense of security. This idea of external control provides an illusion of personal control. Destiny and fate mean that everything happens for a reason, and that nothing is random or unsolvable. As such, the belief in external control resulting in personal control acts as a coping mechanism. The need for personal control arguably exists, and if lacking, could result in heightened feelings of anxiety. This brings back Peter L. Berger’s theory about the human need for meaning. Here the sense of peace or Sakinah is not only a result of religiosity, whatever its form, but also a safe haven from the unknown.

an external superior being’s control over their lives, to have higher sense of security. This idea of external provides an illusion personal control. and fate mean that everything happens for a and that is random or As such, the belief in control resulting in personal acts as a coping mechanism. The need for personal arguably if lacking, could result in feelings of anxiety. brings back Peter Berger’s theory about the human for meaning. the sense of or is not only a result of religiosity, its form, but also safe haven from the unknown.

Despite the religious utopian reward, whether it’s Heaven or Godly blessings in life, there is grotesqueness within the aspired purity of religion. The existence of violence in the name of righting wrongs, and deadly poverty in the name of naturally occurring classes, begs the inevitable question: is the purity really out there? How does a believer perform their religious rituals and believe in Heaven while living as an oppressed minority? How could a believer in Heaven kill a sacred soul to reach their own idea of purity? Maybe purity isn’t tangible, but rather is more of a state. Even if it is, there is definitely an impure side to it. Theodicy attempts to answer these questions, or the broader concerns of why God permits the existence of evil, and the balance between this inconsistency of a pure God and an immoral world. After the Holocaust, numerous Jewish theologians responded to the concept of theodicy with anti-theodicy, which argues that the justification of God’s existence along with such horrific evil is not possible. Similarly, Protestant theologians started writing about “The Death of God” after WWII. Richard Rubenstein, an academic Rabbi, proposes in his book “After Auschwitz”

that Judaism after the Holocaust should be treated solely as a ritualistic and mythical guideline that helps its followers cope with the world, not a religion. Max Weber on the other hand, argued that theodicy in itself is part of the human quest for reason, even when there is none.

Despite the religious utopian reward, it’s Heaven or Godly blessings in there is grotesqueness the purity of religion. The existence of violence in the name of righting and deadly poverty in the name of naturally occurring classes, begs the inevitable is the purity really out there? How a believer perform their religious and believe in living as an oppressed minority? How a believer in Heaven kill a to reach their own idea of purity? purity isn’t but is more of state. if it is, there is definitely impure side to Theodicy to answer these questions, or the concerns of why God permits the existence of and the balance this inconsistency of a God an world. After the Holocaust, numerous Jewish theologians responded to the concept with anti-theodicy, argues that the justification of God’s existence along such evil is not Similarly, Protestant theologians started writing about “The Death of God” after WWII. Richard Rubenstein, an academic Rabbi, proposes in his After Auschwitz” that Judaism after the Holocaust should be solely as a ritualistic and mythical guideline that helps followers cope with the world, not a religion. Weber on the other hand, argued in itself is part of the human quest for reason, even there is none.

In her book Purity and Danger anthropologist Mary Douglas argues that societies’ perceptions of purity and pollution are relative, and their interpretations depend on temporary social norms in collective communities. What she calls an “ambiguity of definitions” is cleared up by categorizations which change according to differences in culture. Taboos also emerge from that notion; for example, the significance of virginity differs from culture to culture. Maintaining family honor held together by a sacred hymen, could go as far as murder. On the other hand, the hymen could exist as what it is: just a membrane. The same hymen-less woman exists as a disgrace in a culture, and as the opposite in another.

In her book Purity Danger anthropologist Douglas argues that societies’ perceptions of and pollution are and their interpretations on temporary social norms in communities. she calls an “ambiguity of definitions” is cleared up by categorizations change according to in culture. Taboos also from for example, the significance of virginity differs from culture to Maintaining family honor held together by a sacred hymen, could go as as murder. On the hand, the hymen could as what it is: just a membrane. The same hymen-less exists as disgrace in a culture, and as the opposite in another.

Work and worship present dynamic that comes with perspectives in religion. In Islam, work is a holy act of worship, and a contribution to God’s Muslim scholar Al-Ghazali mentions in his book The Book of Provision, an instance between a man and Jesus. The man devoted himself to religious rituals, and Jesus him how he made a he explained that his brother for both them. Jesus then told him that brother was more religious than him. The Protestant work ethic is similar in that aspect, where hard work is equated being a Christian, which is argued to be the origin of Capitalism. Jewish faith maintains the Sabbath Sabbath starts on Friday sunset Saturday’s sunset, and is a of rest worship only. Work and other activities including cooking are prohibited.

Work and worship present a dynamic that comes with varying perspectives in religion. In Islam, work is considered a holy act of worship, and a positive contribution to God’s creation. Muslim scholar Al-Ghazali mentions in his book The Book of Provision, an instance between a man and Jesus. The man devoted himself to practicing religious rituals, and when Jesus asked him how he made a living, he explained that his brother provided for both of them. Jesus then told him that his brother was more religious than him. The Protestant work ethic is similar in that aspect, where hard work is equated with being a good Christian, which is argued to be the origin of Capitalism. The Jewish faith however, maintains the Sabbath day. Sabbath starts on Friday at sunset to Saturday’s sunset, and is a day of rest and worship only. Work and many other activities including cooking are prohibited.

Religious is a given to believers and a farce to Still, it remains a controversial concept, whether because it’s too good to be a coping mechanism, or a incomprehensible to many. It would be naïve to attach label, claiming an entirely religion. But if anything is to be deemed certain, it might as well be this: “Believe me, religions on the wrong the moment they moralize and commandments. God not needed to create or to punish. fellow men aided by ourselves.”— Albert Camus, The Fall.

Religious purity is a given to believers and a farce to non-believers. Still, it remains a controversial concept, whether because it’s too good to be true, a coping mechanism, or a reality incomprehensible to many. It would be naïve to attach a label, claiming an entirely pure religion. But if anything is to be deemed certain, it might as well be this: “Believe me, religions are on the wrong track the moment they moralize and fulminate commandments. God is not needed to create guilt or to punish. Our fellow men suffice, aided by ourselves.”— Albert Camus, The Fall.

Photo by Ingie Gohar

of womanhood lacks

Unsolicited liquid is oozing out of you. Placenta and blood and other obscure fluids are exiting your system in a uniform fashion, a gentle stream puddling between your thighs. At this point, you probably cannot tell whether your body is releasing afterbirth or defecating. You are likely to be participating in the excretion of both, simultaneously. You are bloody, icky, and disgusting. Your hair is matted across your forehead, soggy with hideous sweat. The doctor asks you how you feel and you tell him you feel beautiful. A woman must always feel beautiful. Take this moment to observe yourself carefully, and if the situation calls for it, gag in disgust. If you’re feeling extra frivolous, vomit all over the hospital gown you’re wearing; the same one your mother wore as she too emptied her bowels while giving birth to you. Regardless, take notice of your unshaven legs, what would he make out of such an unruly sight? Assess your thighs; you can finally see them now. Use your once delicate but now obesely bloated fingers to trace the cellulite that has mapped itself along the curvatures of your skin. Suppress a sob as the movements of your fingers mimic that of a vehicle traveling on an uncemented highway. Lumpy, lumpy skin.

The female body—a long disputed territory, a collection of crevices harboring zits and uteri and ashy ankles. The female body, flexible, easily collapsible, foldable, boxed, and shelved. The body a sack of bones clanging against each other. An accumulation of flesh and bone carved out and assembled using their eyes, their tongues. You, a caricature of femininity that tastes similar to that which your mother used to feed you. A caricature of the ideal woman: poised and calm and collected. You, a product of a set of social institutions that they shoved down your throat but that you have since forgotten to purge. So now, you ask them to stab needles into your back so you never forget to sit up straight. Watch, as one hair follicle after the next is ripped out of your skin making you more woman. Stay quiet, as blood clots disintegrate and stain your sheets, your new jeans, and the chair in that one classroom that you haven’t been in since. Smile, with your eyes rather than your teeth. And perform, they all await you.

It is 2015. The London Marathon is tomorrow and Kiran Gandhi, who has been training all year for the event, has just started her period. She is in distress. Where will she possibly put away all the blood that is bound to excrete itself out of her in the 5 hours it takes to run the marathon? It is the next day, Kiran Gandhi decides that she is going to run the marathon without a tampon, a pad, a menstrual cup or any other protective surface that can prevent her blood from seeping into her pants. Instead, she wears neon pink leggings and she runs and nobody can do anything about it. She runs and her blood slowly makes its way

down her inner thighs, surely chafing her skin in the meantime. Afterwards, when asked why she did what she did, Kiran responds by saying that it was simply what she felt would make her feel most comfortable. That she would not both run a marathon and worry about the logistics of a tampon shoved into her. What is there to learn from such a woman? Is it that a man cannot police a woman’s body if she is outrunning him? Is it that shame eradicates itself from the body only at the point of extreme fatigue? Perhaps.

‘ةروع ةأرملا توص’. In which you, a woman, cannot speak lest you be heard. A culture of shame that they have planted into you, now sprouts out, making its way through your lips and down your esophagus. Do you feel the way its thorns scratch at your throat every time you try to speak? How it has paralyzed your tongue? Your most innate feature no longer innate but characteristic of a tumor ebbing out of your forehead, threatening to pierce through and unleash itself onto whoever you stand before. So now, when they ask you to dance, you dance. Barefoot, as the gravel scrapes your foot and punctures your heel. When they ask you for tea, you make them tea and pour it into saliva laced teacups, and smile with your eyes. When they ask you for your name, you nod. Yes, I am whoever you want me to be. And when they ask you for your hand, you stay still, your hand already theirs. You, an object of convenience. Skin so smooth and hair so silky you become the tapestry. You, the embodiment of what they find perfection to be, do you not miss the taste of your tongue as it curled and snapped in revolt?

You sit with your legs wide open; it is not comfortable but it makes them see you. You suck on your palms as they watch, weary. Hairy tendrils are sticking out from underneath the hem of your pants, threatening to suddenly blossom

and encircle their necks, putting each one of them in a chokehold. You scream vulgarities that you do not know the meaning of and watch as your spit streams out of your mouth and lands onto their eyebrows, gently cascading around the curvature of their eyelids and into their eye sockets. Your fingernails yellowing as they succumb to the earwax fermenting beneath them. This is the closest that freedom will ever come to you. There are onlookers. Bare your teeth to them and watch as they cringe back in disgust as the aroma of your mouth violates their senses. Watch, as they shrivel into themselves and cower in fear of what you have become. Of, finally, what you have made of yourself. Build a fortress and from it, throw soiled pads at passersby that dare look at you for longer than three seconds. Walk through a muddy field barefoot then paint your toenails because this is how you choose to artistically express yourself. Staple flyers of propaganda onto strangers’ chests and unleash a guttural screech if one of them is so brash as to try to utter a complaint. They need you, don’t they? What else is there to counter one extremity with if not another? How else will they indoctrinate the rest, if not by dissecting your body and splaying its organs across their sidewalks? How else?

Because necessity is oppressive.

piercing skin pierce this skin rupturing sebaceous bliss coursing through coarse and true honoring virile lineage of the multiple masculine melodramas these curses i’ve been blessed with these gifts with no return address these true features, this true sex you are perhaps the most superfluous // i can and cannot do with or without you and precision is that enemy it stalls, stops and fixes me and the various bio-technologies the managing and murdering of bodies the growth and decay of societies and wondering if my father is proud of me your heavy duty machinery far too heavy handed on me and yet you come so patchily denying me even the semblance of success to think my masquerade unnoticed to walk aimless, to breathe smooth //

the markings of a sex leave pocked and gendered markings on my neck yet in your strength subdued, still i bear your likeness, simultaneous to that of an agent, still in your firm grip – sacred and scarring the visage a machinery subcutaneous wreaking havoc upon this flesh // and with the workings of a gaze doubled a curious thieving optic troubled a body-object molded huddled crippled and crippling vanished and vanishing scrapping and scrapping a sisyphean self-fashioning and spiraling self-doubt to the sounds of solipsism on the skin and throughout a furtive fertility inescapable continuity stunned and stunted inhabiting perpetual irony.

Ever been at a baby shower—bored out of your mind—twiddling your fingers and pulling at your hair, when a thought pops into your head: “man, wouldn’t it be kind of awesome if someone burst through the door right now and shot us all dead”? No? Yes? Maybe? Well, you may not have had that exact same thought, but we’ve all had that one moment where we thought of something that can only be described as purely “psychotic”—and if you say you haven’t, you’re a liar. Comedian Daniel Sloss once said:

“A lot of people think I’m a good person. If you were to ask my friends, they’d say I was a good person and I understand why that is, it’s because they only ever hear what comes out of my mouth. They never hear what’s going on in my head, and those are two hugely different things.”

Everyone assumes that, just because you don’t kick baby kittens on your way to work every morning, you don’t have little voices in your head actively telling you to do despicable things from time to time— which is completely false… Don’t you think? Having violent or grotesque thoughts isn’t limited to only psychopaths and serial killers; they’re thoughts even your own mother has from time to time. In fact, she’s probably fantasized about dropping you as a baby down a flight of stairs on more than one occasion. These thoughts are called “intrusive thoughts.” They’re natural, nothing to worry about, and don’t make you any less of a good person.

I’d advise all of you who have these sorts of thoughts to try and embrace them or laugh them off, because the more you fight these thoughts, the worse they get. A study about thought suppression, conducted by the now deceased Harvard professor Daniel M. Wegner, found that trying your hardest to

not think about something actually makes you think about that thing even more. So the harder you try to not think about committing heinous crimes, the more you’ll end up having those thoughts. So go easy on yourself and relax. If you actually believe that one or two nasty thoughts are going to make you Dahmer 2.0, you’re probably wrong.

However, for people with OCD, having these kinds of constant intrusive thoughts becomes rather debilitating. They begin second guessing themselves, thinking, “Do I really love this person?” or “am I really a monster?” then they start to worry if they really can hurt this person. Dr. Seth J. Gillihan from the University of Pennsylvania calls this form of OCD “Malevolence OCD” (or for short: MOCD). People suffering from this disorder have violent obsessions that trigger massive anxiety, and as a result, they’ll feel the need to do something to ensure that they won’t hurt anyone. This begs the question: “how do I tell the difference between having MOCD and being a psychopath?” Well, the distinguishing factors are easy: people with MOCD find the idea of acting on their obsessions downright repulsive, but psychopaths tend to not act on their thoughts solely because of the aftermath of their potential actions.

So hopefully most of you just drew a breath of relief, thankful that you’re not an up-andcoming serial killer. Some of you, on the other hand, may be slightly disappointed to realize that you lack the potential to become one. But for those of you who still worry, please remember that thoughts are only thoughts. It’s only when you actually pick up the axe do we really have a problem.

I am cinched by my despair, Living in a cycle of grieving My own life, Overcome by a chemical imbalance That nothing seems to fix.

I wish happiness was a simple decision. I’ve lost sleep over losing sleep In a bed warm as mine, choked on my privileges and easy life, felt closer to death every night, only to wake up to the blinding sunshine

I’ve tried drinking lavender tea before bed, but fate is a cruel mistress— I find my hands shaking every time I try to turn the kettle on, reminding me of the ‘92 earthquake and the stories my mother told me over coffee breaks. The reminder tempts me to stay awake, The fear of what we have not surviving a good night’s sleep leaves me wide awake in ocean dreams.

And I know I can talk to my mother, But most days I feel that I am talking through her, So I fold up my emotions like origami pills

and keep them lodged in my throat, The words claw and gnaw my insides raw But only the silence escapes me.

I do want to have lunch with my mother, but most days I don’t want to have lunch at all. Yesterday’s dinner sits tied to a sinking stone in my abdomen, Weighing me down with its heaviness and my guilt. I’ve always loved food, But most days I can’t bring myself to like it anymore.

Most days I can’t bring myself to like me anymore. I have been practicing self-love, I applied a face mask last night, But the hate I harbor for myself Cannot be washed off in 30 minutes.

I wish I could grow flowers In the cracks and crevices The depression uses to seep into my being; Romanticize my sadness and rebuild my broken dreams— But how can I when I cannot even go to sleep?

Writer: Eisha Afifi Editor: Farida GoharDear Criptess,

I can hardly believe that this village is part of our kingdom! True, it lies on the border, but these misshapen huts, muddy roads, filthy peasant folk… I wonder how they could belong. Words cannot do justice to my repulsion; even the quill I hold dirties my fingers!

I write though I know you are unable to answer, dear friend. I suppose you couldn’t have heard, but last night, the chancellor decreed: “until her majesty, Queen Cordialla, declares the mandatory exile complete, the princess shall have no contact beyond the village.”

For something so positively infuriating, I only have Mother to thank! Sending me— her own daughter, the princess!—to live among the commoners. Did she think this village suitable for one such as myself?

She claims I will learn valuable lessons, but what, in this foul wasteland? What teacher could bestow any such knowledge upon me? A native? Perhaps if they did not all appear as lifeless as the filth they dwell in!

Bother… I will see this tradition of exile ended once I become queen.

May you fare better than I, Princess Manitelle

Dearest Mother, Some nights have passed with the family to which you have so kindly shackled me. I spend mornings baking inside this hut, cleaning away scum alongside those who would benefit more from cleaning themselves. I fail to see the meaning in this. Regardless, I have engaged with them. The parents are hard-working though hardly of note. I cannot fathom their decision to have five children. In these conditions! Is this not some crime?

Of the children, the eldest is a son, married and away. The rest are daughters of various ages. Artyris, the eldest daughter, has tried frequently to converse during our daily tasks. I have obliged, though not for any reason beyond necessity.

She speaks simply of simple things, as one would expect. Of her siblings and companions, she speaks at length. It is at times tiresome, and I often find myself losing focus. Who would not, distracted by the spittle that flies from her cracked lips, the small insects that crawl through her hair, the flakes falling from her dirt-caked arm!

Mother, I am disgusted. I recoil at it all, people and surroundings alike.

Respectfully, Princess Manitelle

Dear Criptess, I have continued attending lessons (if they qualify as such) with Artyris. I have met the companions of whom she has spoken so highly. Though I do not share her opinion, I must say that my opinion of her has improved.

During the first lessons, I noticed she exhibits an eagerness unlike those around her. I must revise my statement that she is simple; she has proven quite knowledgeable, given her circumstances. Not that this excuses her unclean appearance, of course. Just yesterday, she claimed that I remind her of her younger sisters and laughed, though I can’t comprehend why; they’re all haughty little things, really. None know their place! We returned from lessons walking through the village. Barbaric for ladies such as myself, but alas. Artyris stumbled again. I assume she is unwell but does not speak of it (I need not concern myself with her affairs, regardless). I nearly offered her my hand but was overcome with such a feeling of sickness that I froze. I suspect that, even had her hands not been dirtied by the ground, I’d have frozen. There is this feeling I have about Artyris and the village folk… Can one be stained by destitution?

It permeates the earth, taints the food, the furniture, the people… though I suppose this concept is alien to you. Such people have shame enough not to show themselves in the capital.

Best, Princess ManitelleDear Criptess, Artyris has fallen so ill that I have been removed from her quarters. It is catching. And yet, her family surrounds her. Even the eldest son has returned.

While I have not been expressly forbidden to enter, I dare not. With so many of them in that small room, huddled so intolerably close… I dare not. Yet those soft sobs stab at me. Is she in great pain? The family has assured me that she is not, but I fear their words were simply meant to comfort.

As such, when a nobleman’s caravan passed through the village today, I stopped him. How surprised he was to see the heiress! But I digress. I had him deliver a letter to Mother. I am no fool; I know Artyris will not fare well without a proper physician’s aid.

There, again… She cries. But, that small room… It will be so much worse than sitting at this dust-covered slab on this filth-ridden floor with this grime-laden quill!

Even the door is too scum-covered to touch. Would my presence even be felt? I know not.

Sincerely, Princess Manitelle Writer: Heidi Aref Editor: Yasmeen BadawyDear Artyris,

I have concluded my mandatory exile and have safely returned to the castle. I have a free moment and so have chosen to write, as I’ve gotten into the habit since I began my stay with you.

I thought to write about my first and only visit during your illness. Upon entering the room, your family stared at me. Tears streaked their faces. I thought they were angry as well as sad. Were they angry at me? Are you?

I sat silently by your side. Do you remember me, there? I was the one who shed no tears, who tried not to touch or be touched.

But, you were remarkably clean. I suppose your family tended to you well.

At this time, your breathing was weak. The sobs I heard were no longer yours. Little teardrops fell, creating mud of dirt. Your mother leaned close when you tried to speak. Otherwise, all was quiet.

The room was very dark, but I still saw when you turned your head and looked my way. I saw when your hand reached out feebly.

And yet, I did nothing. Why? Simple: because though you were clean, you were disgusting. You were dirty. How could someone like you not be?

I did nothing, and your family saw. You saw. And abruptly, I saw. What I was doing. What was I doing? I looked down, and I was holding your hand.

I remember you smiled, but I could not. I was overcome with disgust, for in that moment of hesitation before taking your hand, I felt filthy. Dirty. Vile.

I let go and left the room. Fled. Looking around, the hut seemed remarkably clean. Outside, the muddy, trodden roads sparkled. But my own hands… I tarnished everything I touched. How did you reach out to someone like me? How could you bear the sight?

I ask these questions but expect no response. After all, by the time the physician arrived, it was a gravedigger you needed.

Soon after, my exile ended, but the feeling did not. That dirtiness is something I am unable to rid myself of; it is on my skin, yet not…

Curious, how my own quill now feels tainted by my hand. I will not have it suffer me much longer. I do not imagine you wish to hear more of one such as myself in any case.

Manitelle Photo by Ingie Gohar

The Soldier rested his back against the wall, taking a draw from his cigarette as he stared at the four men in front of him playing cards. Two argued that the third cheated, and the last was laughing in a way reminiscent of a donkey. The scorching sun stretched their shadows across the encampment. The Soldier stood alone, his dry lips stuck together from hours of silence, split in the middle where he held his Marlboro. They had been sitting tight for a few days, since the cease-fire had been called, and most soldiers had been enjoying their time off. Not the Soldier. He tapped his foot against the ground, eager to do something.

The Soldier pushed himself off the wall and picked up the rifle next to him. His black boots crunched against the ground as he walked. He entered the sniper’s den, a small area covered with a tarp at the edge of the base, and put his hand on the shoulder of the other sniper there.

“I’ve got this, Yusuf,” the Soldier said, the ashes from his cigarette falling as he spoke. “How long’s it been?”

“Around three hours,”

Writer: Karim Abdel Hamid Editor: Arwa HezzahYusuf nodded and rubbed his eyes, “Yeah, I’ll just go get some shut-eye.”

The Soldier helped Yusuf up by the hand and pushed him out of the den. He quickly fixed his rifle atop the sandbags that gave him cover. Sprawling across the floor, he put his head against the stock of the rifle and looked through the scope.

He and Yusuf took shifts watching an old road that passed by the base, linking Kurdish Syria and Turkey. Cracks ran throughout the asphalt, and it was covered with sand from lack of use.

After a few hours of staring through the scope, the Soldier rested his eyes and stretched his neck. He soon found himself gazing at his dozens of tattoos on his arms, he remembered when he got each of them. Tattoos were very rare in Turkey, but he had started getting them at 16, sneaking out of his house to get them with his small sum of savings. His favorite was a cracked skull, with thorny vines twirling around them. Most of the tattoos covered swelling lines. There were more on his back, where his dad’s belt met his skin. Some were lines on his wrist. Those he claimed as his own. The Soldier’s body was a gallery of pain that he had turned into beauty with his little inked masterpieces.

Then he noticed that tattoo with his mom’s name. Cliché, maybe, but it was important for it to always be there. She was always there for him. She was there when he won his football matches, and when he shed his tears. When she wasn’t feigning ignorance of how her husband was beating her son, she iced his wounds and made him feel better.

to act out the fighting. He made sounds to imitate the grunts and groans of his action figures. But he yelled too loudly and disturbed his father at the wheel. The Father smacked the Boy’s legs, making him yelp out in pain.

“Shut up for five minutes! If I hear another peep out of you for the rest of the ride, I’m going to choke the fuck out of you so I can get some damn peace.”

The Boy stifled his tears, wrapping his arms around his legs to ease the pain. His mother turned in her seat and soothed the Boy’s bruise with her hand.

“Leave him be,’’ the father said. “if you keep babying him, he’ll never become a real man.”

The mother quickly faced forwards in obedience. The Boy knew she was just as scared as he was. The Boy’s tears fell onto his bruise, which helped somewhat. Soon, the father pulled over.

The sound of spinning wheels drowned out the sound of music. The Boy was playing with his toys, an action figure and a toy velociraptor, pressing them against each other

“I need a break. From driving, from you,

from this fucking life. I get zero gratitude from either of you, and I’m so goddamn tired of it.” He slammed the door, and when he was a clear distance away, the mother turned and gave her son a kiss on the cheek.

“I know he gets angry a lot, but never mind him. You know, he loves you.”

The Soldier had stopped looking at his arms and was now staring into the desert. He shook his head to get some focus and reached for the water bottle next to him. As he drank, he saw dust rising far in the distance. He put down the bottle, seeing a Toyota driving across the road. The Soldier put his eye to his scope and took a closer look. The car came to a halt on the side of the road. He made out three figures inside the car, as one quickly opened the door and got out. It was a man, wearing a beige shirt and khakis. Half a minute later, a woman exited the other side, and stared out into the desert.

The Soldier stared at the figures for a minute, his hand grasping his rifle. His finger was becoming sore and itchy. He hadn’t been in combat for weeks. But now, right there, he finally had a target. A hundred kilometers out, no one would know where the shot came from. Hell, no one would care. The Soldier looked to the ground and thought for a moment, finger tracing the trigger guard. The woman hadn’t moved, but the man was pacing back and forth.

Suddenly, a jolt of energy came to the Soldier. He put his finger on the trigger, aimed at the woman, and fired. She collapsed a second later, when the bullet finally hit. The Soldier grinned. The man in the distance turned to face his wife and swiftly moved towards her. The Soldier grinned further as he turned the rifle towards the man and shot. It felt good. The release. The adrenaline. The power he’s wanted for so long.

The fact he could make that shot filled him with a looming

lust for blood. The Soldier stared through the scope at the man crawling towards his motionless wife, leaving behind a trail of blood. The man soon turned onto his back, his body twitching and, his chest spasming. And then he just stopped.

The Soldier reached for a cigarette and stared at the bodies through his scope. As he gazed at them, he noticed that the woman was moving strangely. Soon, an arm reached out from beneath her. It was small and skinny. Feebly, a small child pulled himself out from under the woman. The Soldier hadn’t seen the Boy to start with. His jaw dropped, and his cigarette fell to the ground.

The Boy, whose shoulder was bleeding, dropped to his knees, pushing his mother to wake. He didn’t understand what had happened. The Soldier stared for another minute. His finger tightened again, and he took the shot. The bullet hit the Boy’s head so hard he flew backwards.

The Soldier lifted his head up from the scope. And he smiled again.

Lest We Forget: On Death Writer: Laila El Refaie Editor: Rawan SohdyYoung friends Victoria and Ellen sit together in the drawing room, dim lamps above each of their heads. Each of them holds a book, their eyes navigating the words and crossing from page to page. Ellen looks up from her book for a moment, as if in an epiphany, and speaks to Victoria.

Ellen: Vicky, I have come across the most intriguing realisation. .

Victoria: (looking up from her own book) And what is that?

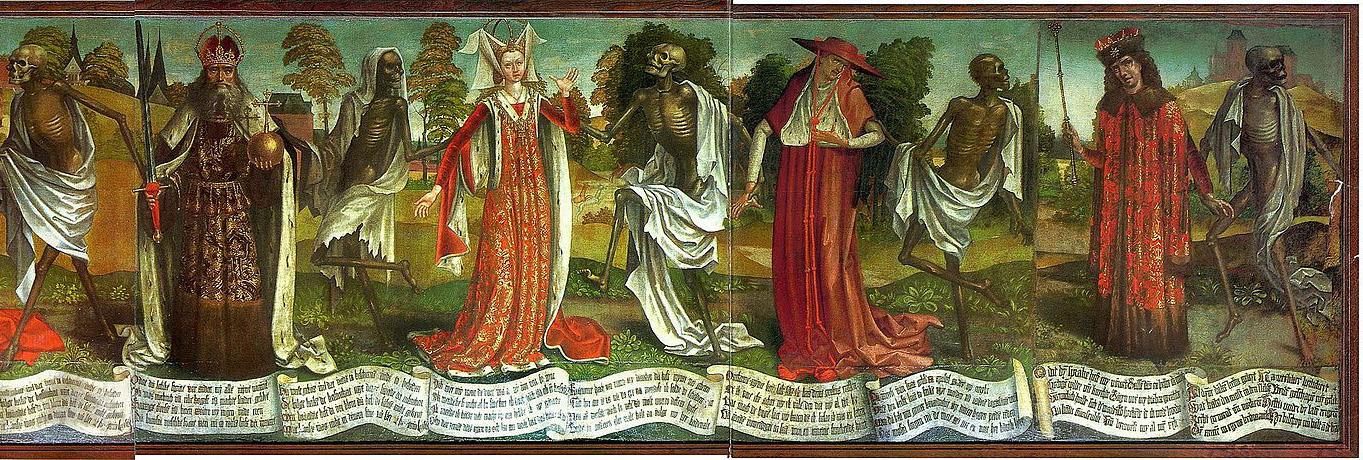

Ellen: Death is abound. Everywhere we look, there is death and decay. In these very books we read, there is no shortage of corpses and coffins. This ongoing danse macabre is daunting, a constant reminder of our finitude.

Victoria: A beautiful painting, mind you. But the macabre is a subject of much interest, Ellen. It’s not simply corpses and coffins galore, but so much more than that. You’re right. Death is abound, but the truer shame is that we learn nothing of it.

Ellen: How do you mean?

Victoria: Look around you, be it Nosferatu or Frankenstein, we consume death like an opiate. We relish the anxiety and palpitations it gives us, but we understand nothing of it, and moreover, we think nothing of it.

Ellen: How do you propose we think of death, then, if not by worrying about it?

Victoria: By thinking about it. By dwelling on the finitude of our existence, and the morbidity of our lives. By engaging in the internal inquiry of why the divine has made it so that our every moment is felt as our first, but as final as our last. I would argue that if we are to salvage what is left of our disgraced morality, we must dwell on death rather than entertain it. We must let its terror take root in our minds, and allow it to shape our every action. All this death and decay you see. Perhaps now it is a cultural commodity, but what of the deaths happening every day? Just last week, a young man barely over sixteen died in his sleep. There were no wounds on his body, or even any traces of poison. But his corpse, like many others, lay pale in his bed. But do we learn anything from this? Does the death of this young man stir in us a desire to think? We all mourned the loss of his life, but did he know he was going to die at such a tender age? Did he stop to think about how he would be remembered? Even if he hadn’t, his death should have reminded us to.

Ellen: The poor boy. But why does it no longer disturb us in this way?

Victoria: Precisely because it is so prevalent. These books, these films, these operas and plays where tragedy is the order of the day and death is the predictable ending, have desensitised us. When you watch a rendition of Hamlet, do you reflect on your own actions? Do you reflect on justice, on life, on death…?

Does the sight of a corpse make you think of your own death? No! No to all of this!

At most, people will shudder and say something about how they would much prefer to avoid such a fate, but do they ponder how to avoid it? Never! Because they detach themselves from it; they are spectators of a masterpiece, gazing woefully at it from afar lest they catch this contagion of death.

Ellen: What a terrible thought… But I wish to ask you: who did?

Victoria: Die? Everything since before the dawn of mankind, of course.

Ellen: Yes, but what of this thinking about death?

Victoria: We have always thought about death to justify our ethics. Many have argued for death as the driver of morality. Those who believe in the afterlife and divine punishment seek Heaven. With death as their deadline, they strive for the completion of their worldly mission, bestowed upon them by God. The Jews, the Christians, the Muslims, the Buddhists—all of them desire some form of nirvana, and all of them fear some form of lamentable curse. The afterlife is one of the most important tenets to any religion, because it keeps the followers honest. If they had no reward or retribution to constantly remember, why else would they be good?

Ellen: I can think of little other reason.

Victoria: Others have argued for other reasons. Thomas Hobbes, for example, did believe that our fear of dying violent deaths was the root cause of our goodness. We form communities, tribes, and alliances to avoid that dreadful fate.

Ellen: I can think of worse things to be afraid of.

Victoria: Of course, but the fact remains that we think of death with fear, be it fear of others, of God, or ourselves.

Ellen: Ourselves?

Victoria: Ourselves. Our legacies. Alexander the Great sought to immortalise himself as a figure of honour and glory. Even you, Ellen, surely wish to be remembered as a good person.

Ellen: Hopefully, yes.

Victoria: And many others, just like you. No religion or social creed has its moral foundations without the acknowledgement of death, and we align ourselves with the belief that frames death in the way we most agree with. Ascribing to a religion thus imposes pressure upon us to act morally, otherwise we would be shunned. While we may fear worldly punishment and criticism, we can resist it, and we can argue against it. However, we have no power to stop people from making our legacy as dark and terrifying as the eyes on our corpses, and we have no power to stop the Lord from damning us to Hellfire.

Ellen: But Vicky! I would lose my mind if I were to think so much of death!

Victoria: Of course, and that process of over-pondering will inevitably desensitise you, just as the arts have. We should ponder death, but only occasionally. Descartes was no skeptic, but he did question his surroundings in his meditations. In similar fashion, we should meditate on death to remind ourselves to be good, just as Descartes would remind himself of what was true.

Ellen: But it seems impossible to walk past a cinema or bookstore without having horror and death lashing out at you. How can we resist this?

Victoria: Think individually, Ellen. Surely we cannot dismantle an entire industry with our discussion, but we should maintain a state of philosophical and spiritual inquiry, no matter the source.

Ellen: The source?

Victoria: As much as it may upset you, the macabre is everywhere. That young boy, cases of murder, and the passing of your own family members should be a source of macabre curiosity, awareness, and inquiry that reminds you to be morally sound.

Ellen: In the misery of death, you wish to find philosophical inquiry?

Victoria: I knew it would upset you, but yes. Call me detached from reality if you will, but in that grief and misery, we must learn our lesson. Death is a lesson from God; a lesson that every step we take may be our last.

Ellen: I can’t help but agree. But come; let us speak of other matters. Otherwise I won’t be able to sleep tonight.

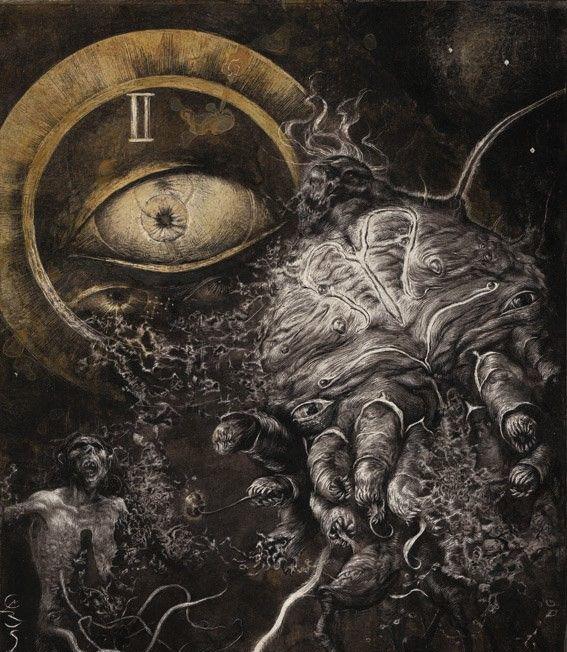

We all love horror; we love the excitement of it, the way it makes us feel. Most importantly, we love the disgusting aspect of it. We don’t like to admit this though— that we have a tendency to like the disgusting. We don’t like to admit to this attraction because we normally don’t like to admit to being “bad people”—just like we don’t like to admit to wanting to choke a sibling to death or to imagining what it would be like to be killed. For a society that is so interested in the macabre, we tend to hide it under false pretenses. Take, for instance, our fascination with the djin and the devil; outside of the context of a horror movie, this could be taken as a form of defiance against religion, but in a horror picture, it suddenly becomes appropriate table talk. And that’s the beauty (or horror) of pop culture. We hide our interest because we need to have a sense of belonging; whatever is not appropriate according to social decorum puts us at risk of getting rejected by society. Thus, we resort to normalizing our “uncommon” interests by putting them in the context of watching a movie.

There are two reigning theories explaining our interest in horror. The first is Carl Jung’s theory, in which he believed that horror movies tapped into an archetype buried deep into our subconscious. Another, older, theory is Aristotle’s: the notion of catharsis. According to Aristotle, we watch horror and violence to purge the negative feelings and thoughts that we have. Since we are unconsciously attracted to the disgusting, it explains why we are all so attracted to horror movies, supernatural thrillers and

Writer: Mariam Zakzouk

Editor: Aly Abdelaal

Writer: Mariam Zakzouk

Editor: Aly Abdelaal

many other subjects that are deemed “undesirable” by our society. Today, psychologists divide horror movie watchers into four categories: gore watchers, thrill watchers, independent watchers, and problem watchers.

When you picture gruesome horror, you might think of shows like the anthology series American Horror Story, specifically its fourth season, Freak Show (20142015). A large majority of the season’s main characters are people with physical deformities. They feel isolated from the world because they are othered for being “disgusting”, until a carnival owner, Jessica Lange’s Elsa Mars, gathers them to be a part of a freak show, where they formed a welcoming community with each other. Not only do we find the characters—or, rather, their struggles—relatable, but we also consistently empathize with them, despite there not being a single entirely innocent character among them. American Horror Story is famous for always making us feel for the “bad guy”, and Freak Show is no exception. Even Twisty the Clown, the season’s main villain, who went around massacring innocents, was made relatable. After the show gave Twisty a relatable and humane backstory, everyone pitied him, with some people even rooting for him. Gore watchers, like American Horror Story fans, usually have a strong identification with the killer. In the case of Twisty the Clown, fans were satisfied with Twisty

punishing people, because in their minds, his victims deserved it.

Think of the other famously gory seasons in this anthology: Coven (2013-2014) and Hotel (2015-2016). They had human sacrifices, torture chambers, and bloody threesomes, among other things. Yet, we keep watching, even though the sight of a human sacrifice is supposed to make our skin crawl. People exposed to disgusting horror scenes (blood, guts, etc.) pay more attention the gorier it gets. They still feel disgust, but their curiosity overpowers that feeling. Research shows that people are less disgusted by gory horror shows than by documentaries that depict essentially the same actions. The only difference is that these horror movies are not real, so we’re placed a safe psychological distance away from them and the violence they portray. We feel safe in a way, so they don’t psychologically affect us—at least not consciously. People who shift into beasts, people who thirst for blood and crave the taste of human flesh, witches and hexes—they’re also presented from a non-threatening distance. Being so curious about the supernatural, we love watching films like The Exorcist (1973), The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005), The Conjuring (2013), or Annabelle (2014). Fans of these films form another category of watchers: thrill watchers. They identify with the victims and love the thrill and fast pace of this genre.

In reality, it’s all historical. Our obsession with zombies started in the 1950s, stemming from the fear of the nuclear bogeyman, and it continued in the 1960s after the Napalm attacks in Vietnam. A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), which featured the zombie-like Freddy Krueger (a child killer who had evaded prison due to a technicality but was later burned alive by the children’s parents), was the product of a general mistrust of authorities that grew out of many rebellious movements as well as the Watergate scandal. Zombies made an appearance again in the 2000s, but this time, as a product of our fear of a global pandemic. This also explains our fascination with movies about postchemical-blast monsters and crises. Whether it stems from innate fears of natural disasters, of the apocalypse, or of something else entirely, it has to stem from something.

On a more local level, in Egyptian culture, we are extremely curious about the Devil— the Shaytaan—and the Djin. The Shaytaan and the Djin are both invisible forces that, as kids, we were taught the existence of, but our generation is more skeptical by nature. We have an unquenchable thirst— we always want to know more. This is why everyone was so attracted to a movie like Al Fil Al Azraq (2014)—The Blue Elephant. It explored new grounds that no Egyptian filmmaker had dared to venture into before. It tapped into our unexplainable fear of

those creatures and our need to find out more, whether we believe in their existence or not.

When you look at more recent horror movies, it is clear that they play on the carnal and disgusting—our shadow self. The horrible little part of us that thoroughly enjoys seeing the protagonist being chased around, the gutting, the evil. It plays on our curiosity and also on our unanswered questions about what happens in the dark. Horror antagonists have become either distracting spectacles or complex, relatable characters. They are a part of us, and that is why we love them so much. We all get scared of ourselves sometimes.

Writer: Maryam Kotb Editor: Farida Gohar

Photo by Georgenia Bassily

Writer: Maryam Kotb Editor: Farida Gohar

Photo by Georgenia Bassily

I was 12 when she told me, you need to lose weight to wear that. She watched as if waiting for magic. As if my tears would slip onto my stomach, casting the spell to pull and hatch out her actual daughter.

The real one would thrust her fingers through this monster’s engorged belly, ripping herself out and swatting away the blood and fat. After the slaughter, my mum would finally be proud. But no matter how many nails I scratch off repeating the ritual the mantra you’ve gained goes on gnawing, and is there an answer but gripped teeth? I have hunched my neck too often staring back at unforgiving digits, I forget that this body is not a monster that needs to be hidden under my bed.

This body, my body, is more than one more Russian doll waiting to be plied open.

From Socrates’ death sentence, to Malcolm X’s assassination, there has always been a trend of individualistic thinkers being shut down. It seems as if diverging from established norms (be it socially-agreed upon ones, or those imposed by powerful authorities) is the common “sin” across history. Whether it’s violating divine or social norms, nonconformity seems to be the major sin.

A sin is essentially an immoral act considered to be a transgression against the law of God. According to most Abrahamic religions as well as some polytheistic religions such as Hinduism, God always wills what is morally good; which is why sins are considered immoral. Take the seven deadly sins, for example: pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath and sloth. These sins are often seen as abusive and excessive levels of one’s natural instincts. For example, gluttony abuses one’s desire to eat, to consume. It is clear that the deadly sins were inspired by

humanity’s perpetual struggle to transcend their animalistic instincts and rein in their emotions.

Of course, letting your instincts run wild is bound to lead to catastrophic consequences. We’ve established that as a collective species, and used it to create our laws and institutions. However, the idea of sin becomes more complicated when it encompasses things beyond merely controlling one’s primitive instincts, such as Saudi Arabia’s former ban on women driving, because they somehow considered it as sinful.

The notion of sin has always been present in many cultures throughout history, where it was usually equated with an individual’s failure to live up to external standards of conduct, or with their violation of established taboos, laws, or moral codes. So, in other words, this type of sin equals nonconformity. We see that all around us, as our society is quick to label various

harmless things sinful. In some cases, choosing not to have kids is considered sinful as it’s misinterpreted as going against God’s will. People, especially women, who make that decision are heavily stigmatized, when, in reality, wanting to bear children is more of a social expectation than a religious decree. You could even be considered a sinner for what you wear or for choosing to get an imprint on your skin, and these things are enough to make you ostracized from certain societies or subcultures.

But if some people don’t believe in God, does that mean that morality ceases to exist for them? Clearly not. There’s still a consensus on some form of objective morality in secular societies. People still condemn others for their actions all the time, regardless of their backgrounds. For liberals in the West, racism, homophobia, and sexism are considered morally wrong, and perpetrators are vehemently chastised. One might even dub them social sins from

Photo by Nada Mohamed

Photo by Nada Mohamed

the aggressive backlash they get, since good and evil are shaped by society’s expectations. Those ideals are even loudly preached nowadays—much like religious ideals were in the past—and those who violate them are shunned from society. So if secular ideals are subject to the same kind of “religious” preaching, does that mean that morality is what powerful authorities or a collective agree upon? And if so, does that make individuality a sin? Is this why free-thinkers across all cultures and time periods are often deemed heretics, socially shunned, and even criminally indicted?

It seems as if societies’ obsession with quashing and policing what they deem ‘sinful’ stems more from a desire for social conformity rather than a genuine concern for religious teachings. There’s a kind of universal inclination in societies towards sanctifying their perception of what’s right, and demonizing whatever digresses from it and thus deeming it as “grotesque”.

Curves andEdges Writer: Nadine Ramzy Editor: Mahmoud El HakimLoneliness is a terrifying feeling. People spend their lifetime searching for somewhere to belong, somewhere to call home. But what if even your own body is foreign to you? When you don’t feel comfortable in a place, you leave—but you can’t escape your body. You try to run away, but it accompanies you everywhere you go. You’re stuck somewhere you don’t belong. You feel a “constant homesickness”.

When you look in the mirror, you feel sick. You feel taunted by everything you hate about yourself staring back at you. The facial hair you just shaved is already starting to reappear, leaving a shadow on your sharp jaw that you wish you could soften. Your eyes trail down your broad shoulders, your flat chest, your square-like waist, and lack of hips. You don’t recognize yourself until you look into your eyes and see the hurt, confusion, and revulsion that have become a part of who you are. They eventually become the only features connecting you to the body you inhabit.

You start wondering why you’re so detached from your body. After all, you’ve been dubbed “man” by everything around you. Before laying eyes on you, they planned a party with blue confetti falling all over the place, revealing your “gender” to the world. Your first encounter with the world was in a hospital room filled with balloons and “it’s a boy!” signs, with a blue pacifier shoved in your mouth, wrapped in a blue blanket. Your parents had already

painted your room in the same blue shade as everything you own. You’re given a “manly” name and referred to as “he” and “him”. A few years later, they give you a sword and a car to play with, while they give your sister a Barbie and a pink broom. You’re taken to karate and football practice. You’re expected to be strong, protect your family, and never cry, or God forbid wear nail polish, because “you’re not a girl” and they would rather have you play with guns than with paint. You’re set up to become a man, before you even understand what a man is.

In the beginning, you thought that everyone felt this way about their body, but as you grew up, you realized that most people felt tied to their body in a way you’ve never experienced. Most people have never had to actively think about their gender or even consider the difference between their sex and gender. Sex refers to someone’s biological characteristics and hormones, whereas gender is related to how a person identifies and perceives themselves, based on psychological and cultural characteristics. A person’s gender can sometimes be aligned with their sex (i.e. someone assigned female at birth identifying as a woman), making them cisgender. Other times, it does not align (i.e. someone assigned female at birth identifying as a man). Often, when someone’s gender identity and sex do not match, they experience strong feelings of distress or gender dysphoria.

A lot of the struggles of gender dysphoria come from being a part of a community in which being anything other than cis is considered abnormal. Always afraid of what people would think. Sometimes they pretend to understand, treating you how you want to be treated. But when you look at them, you can see the repulsion, making your self-hatred and abhorrence multiply. They see you as a man posing as a woman. And slowly, you start believing them. They convince you that you’ll never be a real woman and, deep down, you know that you can’t be a man either. You become transphobic towards your own self.

Among numerous complications of living in Egypt as a trans or gender non-conforming (TGNC) person is the effect society has on you. Since most Egyptians are generally hostile and malicious towards minorities, you must yield some of your rights to protect and maintain your social bonds. Especially, since your families’ moral and financial support can be withdrawn. The lack of education on the subject makes them perceive TGNC individuals as shams or mentally ill. These perceptions, mixed with strictly conservative backgrounds, project on your thoughts and further affect your perception of yourself. Not to mention the dangers of coming out publicly, which include humiliation, bullying, discrimination, and/or physical assault.

Another detriment to people with gender dysphoria is that it has been recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Despite benefiting some people in receiving medical and psychological care and legitimizing their experience, it treats TGNC people as mentally ill, which invalidates their identities and ‘justifies’ discrimination against them. It could also encourage abusive “reparative” therapy that is designed to “cure” gender variance, only to cause harm instead. It induces more internalized transphobia for individuals and exposes them to depression, anxiety, low selfesteem, and suicidal ideation.

There are many ways that people deal with dysphoria. To start therapy, one must assess their goals and needs. For example, some trans people might want to be treated as their affirmed gender without physically altering their appearance.

Being recognized the way they see themselves could help them feel validated and accepted. Depending on a person’s goals, one might shave or leave their body hair, change their haircut, wear clothes that match their gender, in order to feel more comfortable and authentic. Physical appearance can be used to express one’s inner truth. Alternatively, a trans person might want to get medical help with gender affirming surgeries and procedures. They might search for a larger community where they feel understood by people who are struggling with the same issues. This could eventually lead to self-acceptance, which is the most important stage.

Society’s view of gender is very rigid. It associates roles, and in turn distributes rights and responsibilities, according to gender. When someone does not fit into one of these molds, especially the one associated with their assigned sex, people try to fit it in the gender binary. This idea constrains people into looking and acting a certain way in order to be validated. When someone challenges these roles and expresses their gender differently, they are regarded as experiencing their gender “wrongly”. For example, a woman whose expression of femininity is atypical would be referred to as “mestargela”. These judgements are eventually projected on people with gender dysphoria, rendering them self-conscious about their bodies and how they act, in fear of not passing as their affirmed gender in front of people. According to Judith Butler, gender is a performance that we learn to take part in and as we perform it, we reinforce these roles. This could suggest that a person’s gender identity would be aimless if they don’t perform it and earn social recognition. However, Barbara Risman conceptualizes that gender comprises three levels: individual, how a person feels internally; interactional, how a person interacts with society in terms of their gender; and situational, the role one takes in specific situations. Therefore, even with a lack of social recognition, a person’s identity would still be viable since they recognize it and it would help them feel more genuine, even if it’s not expressed. It could allow one to experience their true self on their own terms, without the need to prove it to people.

What do you like about films? What would you consider as a classic? With so many films being released every year with all types of plots, graphics, performances, and scores, it becomes harder and harder for a film to stand out as a classic. Nevertheless, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 masterpiece, The Godfather, has managed to maintain its popularity and status, even after almost 50 years. It continues to embody what it means to be a Hollywood Classic, with its captivating plot, stellar acting and highly memorable score. Released during a bit of an unstable time for the US, by showcasing gangsters in a new light as well as representing Italian-Americans, the film was truly an authentic representation of the culture. It kept its focus on the family rather than the criminal and violent parts of the gangster realm. Thus, the film does not only show the brutal life of the Mafia, but it also shows what it was like to be living in America during that time, to be an ItalianAmerican and to be part of a family so engulfed in crime.

From the very first scene, Marlon Brando’s Don Vito Corleone is a captivating character. Brando’s portrayal clearly shows what it means to be a crime boss and a family man. The film then starts to follow Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone, Don Vito’s son, and his growth and transformation. The film also displays the nature of organized crime that is led by Don Vito, who is only ruthless against those who dare oppose him. Yet, their family is built on support, loyalty, and respect for Vito’s principals. When Vito refuses to partner up with other crime bosses when dealing drugs, it leads to a lot

of conflicts between the five major crime families in New York. The situation quickly turns bloody, taking the lives of many and nearly killing Don Vito. Following the assassination attempt, Sonny, the eldest son, is left in charge, only to get brutally killed. During Sonny’s reign, Michael is responsible for avenging their father by killing Sollozzo and McCluskey (the head of one of the major crime families and a corrupt officer, respectively), thus taking his first steps in the family’s crime world. Michael’s transformation is completed after Sonny is killed and he returns from Sicily (where he was sent to hide) to become the new head of the Corleone family and a Don who proved to be far more ruthless than his father.

The Godfather immerses you in the life of the Corleones and how they deal with their family, allies, and enemies. Interestingly, the family’s criminal activities seem to be accepted by the audience. Perhaps it is because of how they are justified: through the family’s principles, and their great emphasis on unity and loyalty to their allies. Michael, the youngest son, starts out as a war hero that wants to stay out of the family business; however, when he makes the transition to crime boss, it is glorified. At first, he avenges his father under his brother’s leadership, and eventually, he kills all those who wrong the family. Thus, Michael’s loyalty towards his family overshadows the fact that he abandons his principles. Michael’s transformation also seems to be crucial for the family because of the personalities of his brothers. Sonny, the eldest brother, is not as calculating and

calm as his father. As a result, his reign as Don ends with his death after he ignites the first mafia war in a long time. Fredo, the second eldest brother, is known to be the weaker and less intelligent sibling, so he already has less power in the family than his brothers. So it makes perfect sense for Michael to take up the family business and do what needs to be done. Michael was the “college boy” being groomed to enter the political arena, the honorable war veteran, but he steps in to lead the family with the intent of making their business “legitimate”. However, he gets swept up in the criminal world and starts to savor his role as the new “Godfather”.

With all these justifications, Michael Corleone’s transition into the criminal world seems like an effortless and well-explained one. One may even say that it is completely romanticized. A significant reason behind this romanticism could be the time period in which the film takes place. One of the many reasons The Godfather is regarded as a classic is because of its context and the troubled political climate during the 1940s, when it is set. During that time, there was political and economic turmoil in the US; World War II had just ended, and the people were not satisfied with their current situations, so they were actively looking for ways to elevate their lives. These conditions were heightened by economic instability as consumerism rose following the War. This was due to pent-up demand and fears of another Great Depression like the one that followed the First World War. As the idea of the “American Dream” was created and developed, the film

showed how the Corleones were able to live the stereotypical American Dream in an untraditional and clever way. The film showcased the corruption, the violence, and how Italian Americans and other immigrants who were involved in crime coped with these situations to reach their “American Dream”. That is in addition to how the film changed the perception of gangster films, which had previously almost always ended with the demise of the “evil” gangster. However, although Michael Corleone was regarded as the 11th most iconic villain of all time by the American Film Institute, he was still seen by the public as a hero, or at the very least, a tragic hero. Thus, The Godfather challenged the old traditions of gangster films by creating protagonists that are able to kill, plot, and scheme but still be regarded as the ‘good guys’ in the end. Hollywood and other types of media constantly display the varying forms of ugliness that continue to exist, but the way The Godfather does this is unparalleled in film history. The Godfather invites us to question what it means to justify and accept this kind of behavior. It shows a hero, who is not necessarily heroic in the traditional sense but is a morally questionable one living on the wrong side of the law. Witnessing the transition, the reasons behind Michael’s decisions and actions, and his full journey to becoming the Don, makes the audience empathize and understand the roots of his behavior. The narrative, the context, and the environment create the hero that is Michael Corleone and the classical phenomenon that is The Godfather.

Writer: Omar Auf Editor: Laila El Refaie

Writer: Omar Auf Editor: Laila El Refaie

Not too many things in this world are hideous or distorted enough to be described as grotesque. Seldom do we use such a word to describe an action, object, or, certainly, a person. It is a powerful word reserved for only the most repulsive of things. Yet there is a hidden beauty within the grotesque: a beauty of purpose, if you will. Such beauty exceeds appearances and our general preconceived notions of beauty. But what is beauty in the first place? One may say it is that which pleases the eye, but this begets two problems: the first being that aesthetic beauty is a shallow interpretation, and secondly, what that statement describes is the beautiful, not beauty. Beauty is rather that which pleases the soul.

The grotesque, by definition, cannot be aesthetically pleasing. But beauty can exist within the grotesque – in fact, it must. The grotesque exhibits a sheer defiance that is in and of itself a beauty of spirit. Art which is shocking, unnatural, and even disgusting is a good example of this. One need not look very far from the giants of painting to find this. A lot of Salvador Dali’s surrealism can be described as grotesque, yet it still has an appeal. This is because there exist multiple layers of beauty which can be found within it. Society recognizes both exterior and inner beauty. Yet even someone like