TASK: Read the given paper, give a seminar and submit a review

Nature of Ian McHarg’s Science

TASK: Read the given paper, give a seminar and submit a review

Nature of Ian McHarg’s Science

ABSTRACT Ian McHarg undoubtedly will be remembered as one of the most influential landscape architects of the 20th century. His charismatic personality, grand narrative Design with Nature, and unwavering conviction that science would provide meaning and purpose for landscape architects placed him at the center of debates concerning nature, design, and planning. Yet his visions have been criticized as well as praised. Rarely straying from the ideas he developed in the 1960s, McHarg consistently contradicted himself. He criticized humans for privileging man over all other considerations, but he himself was autocratic, asserting his views as absolute and superior to all. His vision of nature was that of dynamic process, yet he sought to plot and rank natural phenomena on static maps. In promoting outdated ideas about science as a savior for landscape architecture, he used rhetorical devices suggestive of religious discourse. His views were complex as well as contradictory. His contribution of “scientific reasoning” to the development of contemporary landscape architecture is countered by his problematical assertions relating to the ecological superiority of English landscape gardens, promotion of the map-overlay method as a scientific process, and combination of Lawrence Henderson and Charles Darwin’s work for his theory of creative fitting.

KEYWORDS history, science, design, nature

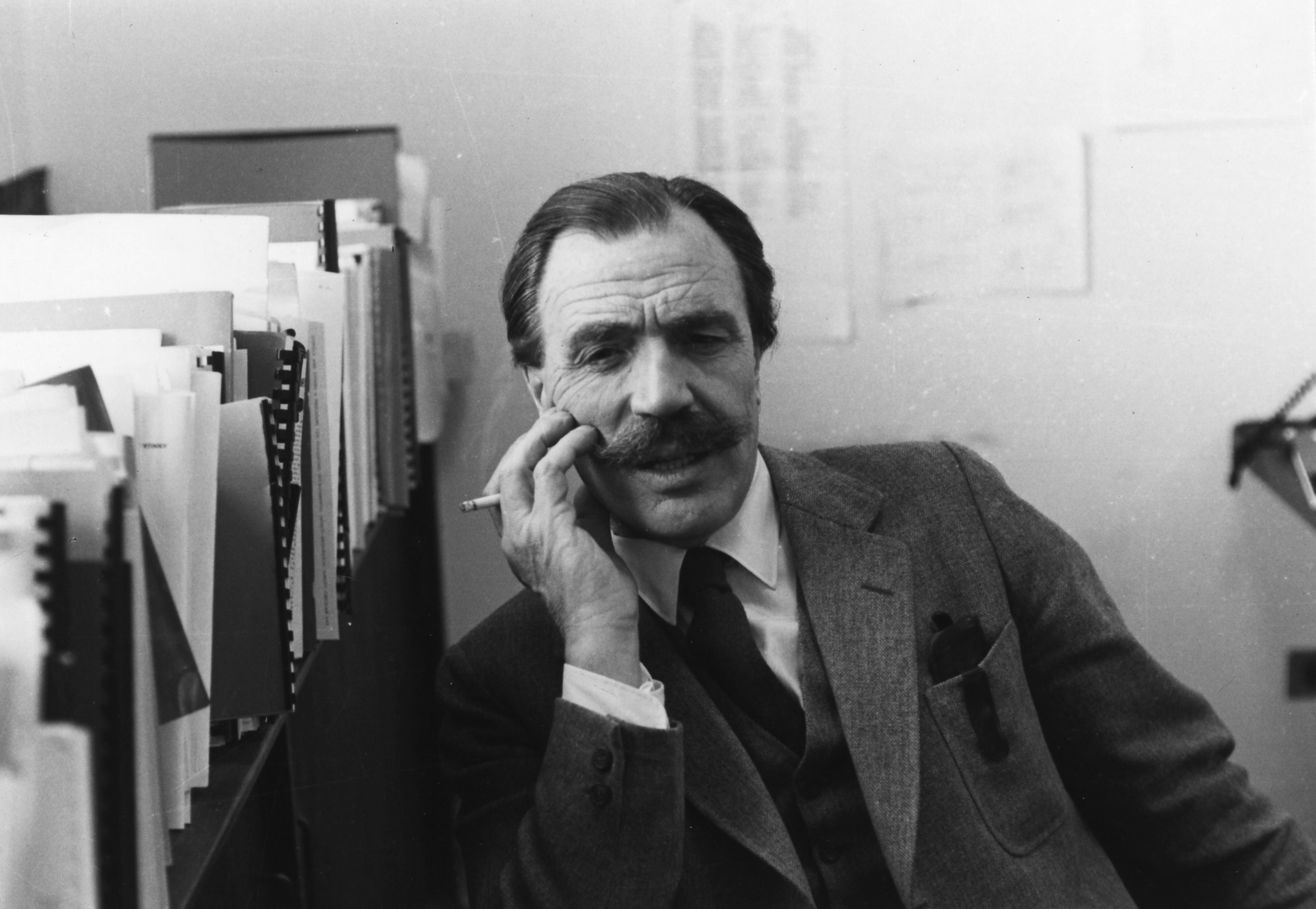

As an author, academic, public personality, and practitioner, Ian McHarg (1920–2001) profoundly changed the teaching and practice of landscape architecture (Figure 1).2 McHarg revealed the damaged condition of the natural environment and held the electrifying promise that landscape architects were instrumental to its repair. He condemned Renaissance, Baroque, and École des Beaux-Arts formalism and championed the use of natural sciences in environmental design. To raise landscape architecture from what he perceived to be the lowly and wanton ways of garden art, not only did he write and teach about the value of science to design but also, with his office Wallace, McHarg, Roberts, and Todd (WMRT), he set out to use science in the design of regional landscapes. As such, he spearheaded multidisciplinary teams including experts from various scientific fields, and he advanced the map-overlay method—a key to his ecological model and a precursor of computerized Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Notably, he sought to bring his

ecological message to nonprofessionals, pioneering the use of television media with his show The House We Live In aired by CBS from 1960 to 1961 (Figure 2).3 McHarg made major contributions to landscape architecture, though aspects of these contributions are problematical, particularly as they relate to science.

McHarg was an inventor of ecological planning, and he became a champion of ecological design. As he explicitly stated in his best-selling book, Design with Nature (1969), “It was not only an explanation but also a command” (McHarg 2006c; 1997, 122).4 McHarg’s major advancements in landscape architecture include the conception of a novel relationship among nature, design, and science; the promotion of the map-overlay method; and the use of scientific theories to measure desired outcomes in the planning and design process. As chair of the resurrected Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, he influenced generations of landscape architects. He was honored accordingly with numerous awards and medals, including election as a Fellow to the American Society of Landscape Architects (1972) and receipt of the American Society of Landscape Architect’s Medal (1984), the LaGasse Medal (1988), the Harvard Lifetime Achievement Award (1992), and the Japan Prize (2000).

Underlying all of these achievements was McHarg’s belief that science was a truth serum that would reveal the verifiable facts of nature to humans. Science provided not only an explanatory model for understanding nature but also a prescriptive one. Equipped with the revelatory powers of science, nature would serve as a guide to design and planning. While McHarg consistently substantiated his ecological ideas with scientific theories, he possessed no formal training as a scientist and he never claimed to be one. In fact, he only took one science class in 1938 at the West of Scotland Agricultural College (MY 1976, 105; McHarg 1996, 82). Although he once referred to himself as a quasi-pseudo-cryptoscientist, many considered him to be a scientist.5 David Orr has suggested that McHarg was “more of a scientist than many he employed. He was a perceptive observer of the wayward ways of men and their tendency towards

selfish destruction of the environment” (2007, 9). Problems nevertheless emerge from McHarg’s conceptions and use of science.

Despite all of McHarg’s triumphs, some aspects of his science were inaccurate. Specifically, his ideas regarding the ecological superiority of English landscape gardens, the promotion of the map-overlay method as an objective process, and the combining of Lawrence Henderson and Charles Darwin’s scientific theories were misguided. Landscape architects and students of landscape architecture continue to perpetuate these inaccuracies. Analyses of McHarg’s texts, projects, and lectures are useful in teasing out the problematic strands of this great landscape architect’s ecological message. Ultimately, they demonstrate that science, like history, is continually revised and that only by incorporating these changes into our own body of knowledge can we benefit from its wisdom.

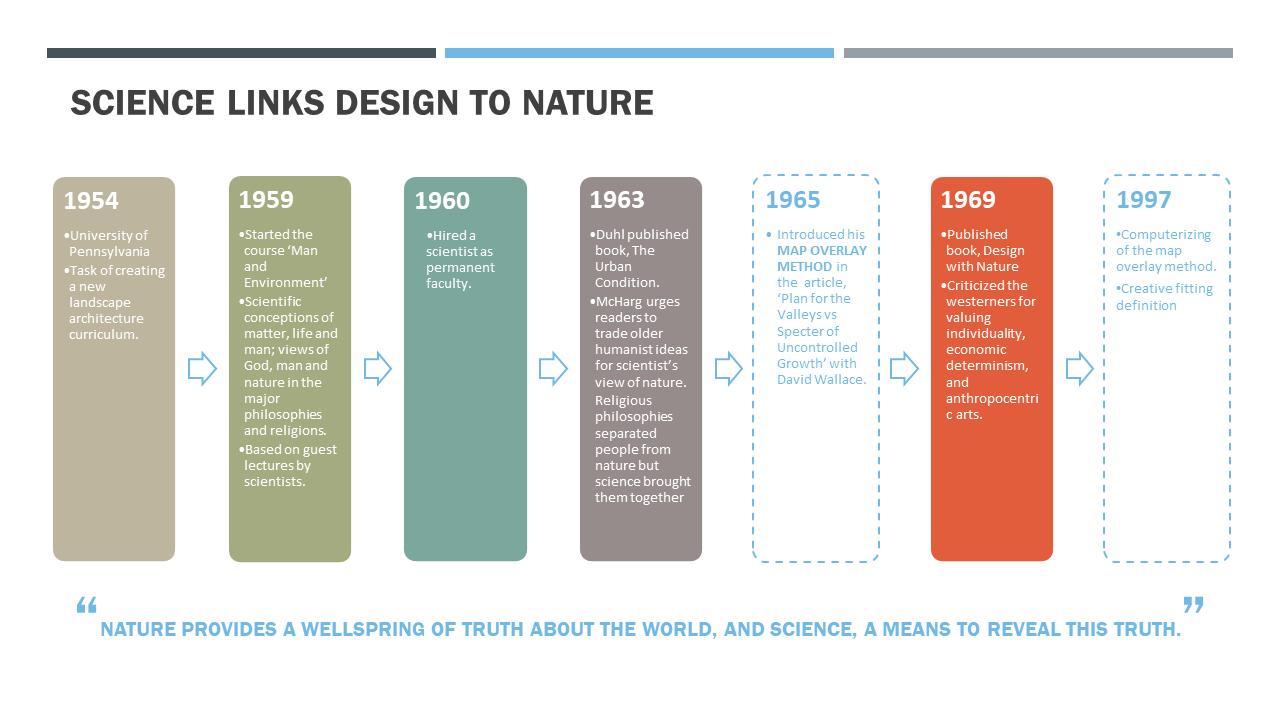

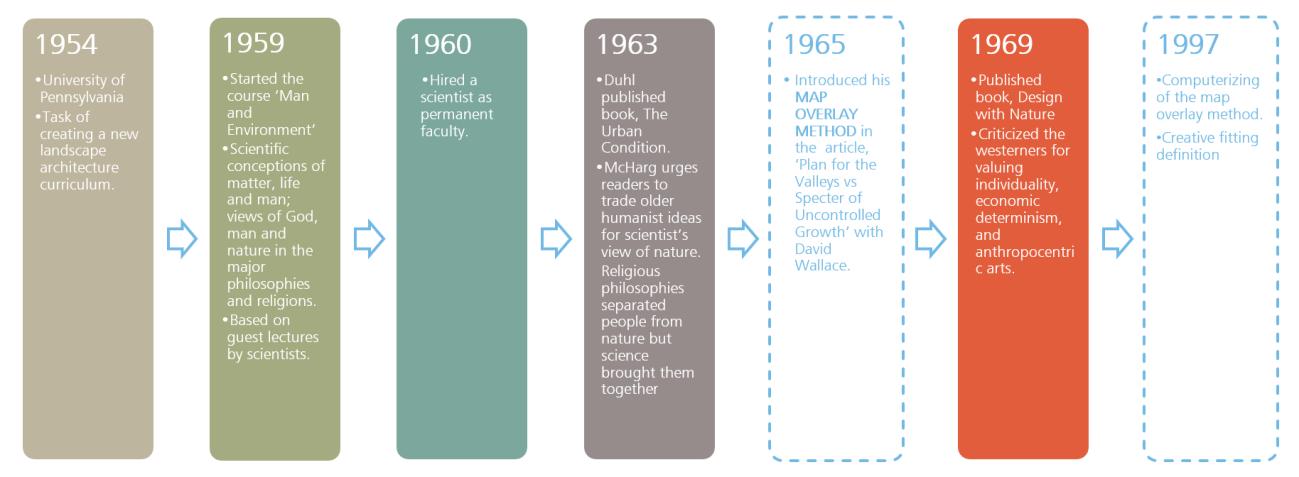

As an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania in 1954, McHarg was charged with the task of creating a new landscape architecture curriculum. He viewed the profession as plagued by low self-esteem in both the academic community and in society in general (McHarg 1996, 129). McHarg admired the modern revolutionaries Christopher Tunnard, Thomas Church, and Lawrence Halprin, but he found most practitioners in North America uninspired and mediocre at best. He sought to change this state of affairs by developing a landscape architecture curriculum that was better than the program at his alma mater, Harvard University. He did this by recruiting top-ranked architecture students and developing courses and studios that included a body of knowledge—the natural sciences—missing from his own experience as a student at Harvard. Scientists were frequent guests to the school, and in 1960 McHarg hired Nicholas Muhlenberg, a scientist with background in forestry and ecology, as part of the permanent faculty (McHarg 1996, 172).

In 1959 McHarg started the course “Man and Environment,” which involved guest lecturers investigating “the scientific conceptions of matter, life, and man; the views of God, man, and nature in the major philosophies and religions” and the ecological interactions of humans and nature (McHarg 1996, 140). In time, theologians declined invitations to the course. McHarg noted: “Scientific expositions amplified the understanding of the miraculous in nature. No scriptural description of the supernatural could remotely compare to the scientific view” (1996, 161). He also investigated the Potomac River Basin with students as part of his design studio. Building upon his experience with large, collaborative projects at Harvard, McHarg incorporated numerous scientists into the fold of this multidisciplinary team. The study integrated an assortment of scientific data, including “meteorology, geology, geomorphology, groundwater and surface hydrology, soils, vegetation, wildlife, limnology, and, where appropriate, physical oceanography and marine biology” (McHarg 1996, 194). This project was “the first of its kind to use the physiographic region and the river basin as the primary organizing context for ecological planning and design—a framework that linked past, present, and anticipated future actions and multiple landscape scales from garden to region” (Spirn 2000, 105). For McHarg, this regional planning study was an “expansion of professional responsibility” (McHarg 1996, 195) that established his ecological planning method (1996, 197).

In 1963, McHarg contended that the ecological and natural sciences offered an important theoretical framework for landscape architects and planners. In “Man and Environment,” which appeared in Leonard Duhl’s The Urban Condition, McHarg asked readers to trade in older, humanist ideas regarding nature for the scientist’s view of the evolution of nature. He posited: “The inheritors of the Judaic-Christian-Humanist tradition have received their injunction from Genesis, a man-oriented universe” (McHarg 2006f; 1963, 3). McHarg viewed religious doctrine as separating humans from nature, whereas science provided an integrative view of humans and nature. In this way, nature

provided a wellspring of truth about the world, and science, a means to reveal this truth. Relating this idea directly to the design and planning process, he surmised, “We have asked Nature to tell Man what it is, in the way of opportunities and of constraints for all prospective land-uses” (McHarg 2007, 44).

In terse prose, McHarg repeatedly condemned Judeo-Christian traditions and Western culture in general as the legitimizing force behind our separation and dominion over nature, and he consistently promoted science as the alternative. This argument appears in his papers “Man and Environment” (2006f; 1963) and “Values, Process, and Form” (2006g; 1968), his speech “Man: Planetary Disease” (1971), his book Design with Nature (1969), his lecture “The Garden as a Metaphysical Symbol” (1980), and an essay for the American Society of Landscape Architects (2006c; 1997). McHarg’s support of science sometimes assumed a religious fervor, and he has been described as the Billy Graham of ecology (Hedgpeth 1986, 48). The opening chapters of Design with Nature (McHarg 1969) take readers from the countryside of Scotland, dune development in the Netherlands, natural disasters, pollution, tacky commercial strips and dense urban living (that would inspire a later generation of designers), and homage to the people of Japan (whom he viewed as indivisible from nature) to a tirade against Western Civilization that valued only individuality, economic determinism, and anthropocentric art. At the end of this blistering critique, he asked, “Where else can we turn for an accurate model of the world and ourselves but to science?” (McHarg 1969, 29)

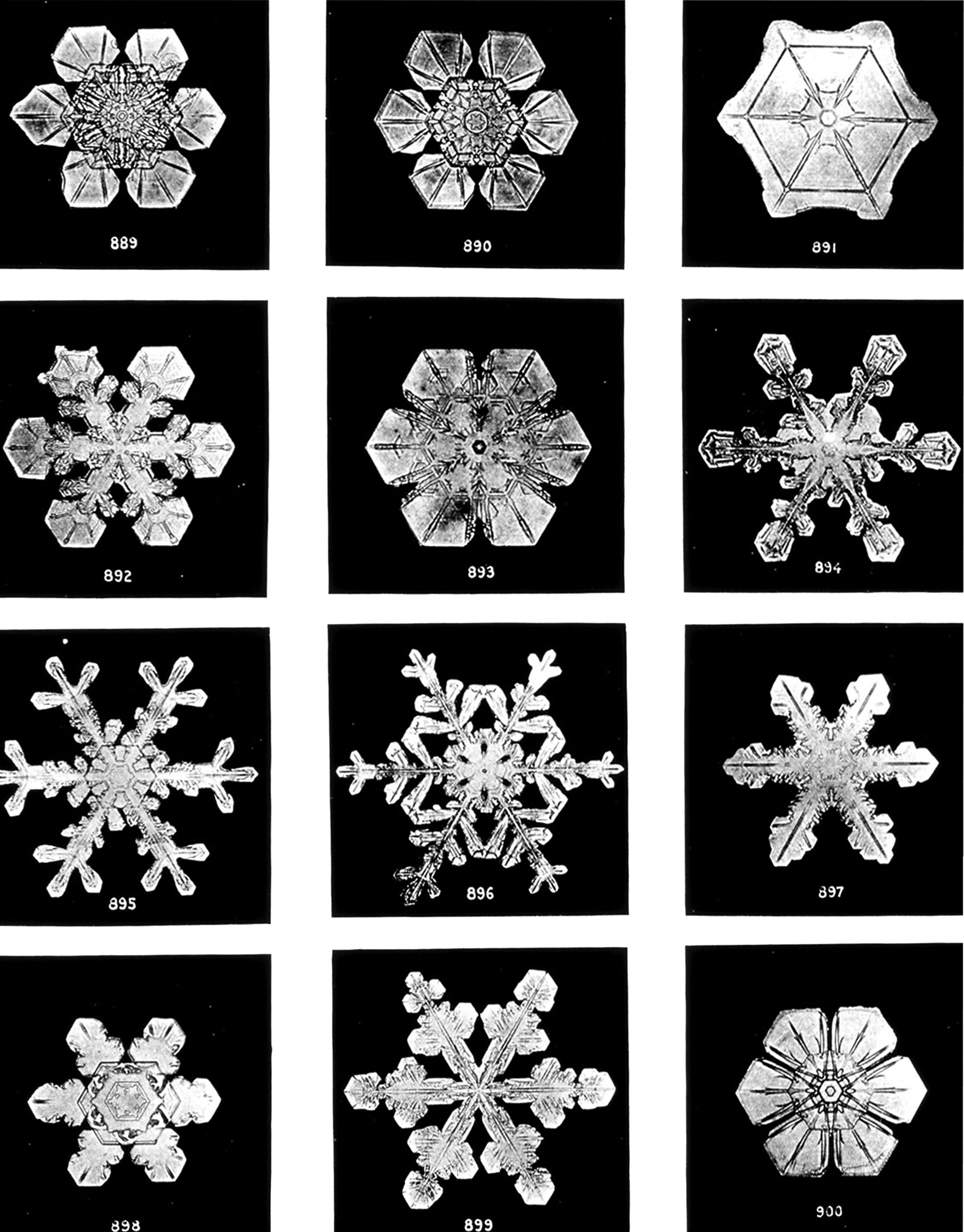

A recurring feature in McHarg’s texts and lectures was the use of representational analogies to validate designing with nature. In making comparisons to show similarities, his analogies were central to both the discovery and explanation of scientific theories. Most notably, Sir Isaac Newton explained his theory of gravitation by drawing a likeness between the way the earth pulls on an apple falling from a tree and the way it attracts the moon. McHarg frequently used the frozen hexagonal

symmetry of snowflakes (Figure 3) or the elegant utility of a bird’s beak to symbolize the inherent beauty of nature’s designs. Moreover, to represent nature’s design at a larger scale, McHarg consistently referred to 18thcentury English landscape gardens, which he viewed as representing ecological concepts. Humans creating these gardens were designing with nature, while earlier Western gardens were not designed with nature.

McHarg frequently berated Renaissance gardens as the penultimate expressions of Judaic-Christian traditions and Western culture. He found they “clearly show the imprint of humanist thought. A rigid symmetrical pattern is imposed relentlessly upon a reluctant landscape” (2006f; 1963, 8). In Design with Nature (1969) his critique of historical landscapes took a full chapter, titled “On Values.” McHarg began with American Indians in North America, who he claimed “evolved a most harmonious balance of man and nature” (1969, 67). He then moved on to the imperious Renaissance gardens, where he perceived “the imposition of a simple Euclidean geometry upon the landscape” (1969, 71). Ultimately, the French Baroque gardens designed by Le Notre were “testimony to the divinity of man and his supremacy over a base and subject nature” (1969, 71).6 Despite the fact that the term ecology was not coined until the 19th century, McHarg found that these gardens had “no ecological concept of community or association” (1969, 71).7 For these reasons, McHarg used them as representational analogies of not designing with nature.

Unlike those involved in earlier gardening traditions, McHarg (1969) wrote, a handful of 18th-century landscape architects believed that “some unity of man and nature was possible and could not only be created but idealized” (1969, 72). For McHarg, English landscape gardens were designed by adhering to a site’s natural functions, making them analogies of designing with nature. He claimed: “Never has a society accomplished such a beneficent transformation of an entire landscape” (1969, 72). He admitted that the designers of these gardens took their cues as to what nature looked like from the Romantic painters Claude Lorraine, Nicolas Poussin, and Salvator Rosa (1969, 73). Nonetheless,

McHarg assured readers, in the English landscape garden “the ruling principle was that ‘nature is the gardener’s best designer’—an empirical ecology” (1969, 73).

In advocating for nature, science, and design, McHarg also introduced a novel definition of nature. He posited that places are “only comprehensible in terms of physical and biological evolution” (1967, 105) and that nature as a process is subject to the forces that produce and control the phenomena of the biophysical world. This definition of nature as a process is an enduring contribution. And the method he advocated for integrating natural processes into design and planning was equally enduring. This method used mapping as a process for conducting extensive landscape inventories.

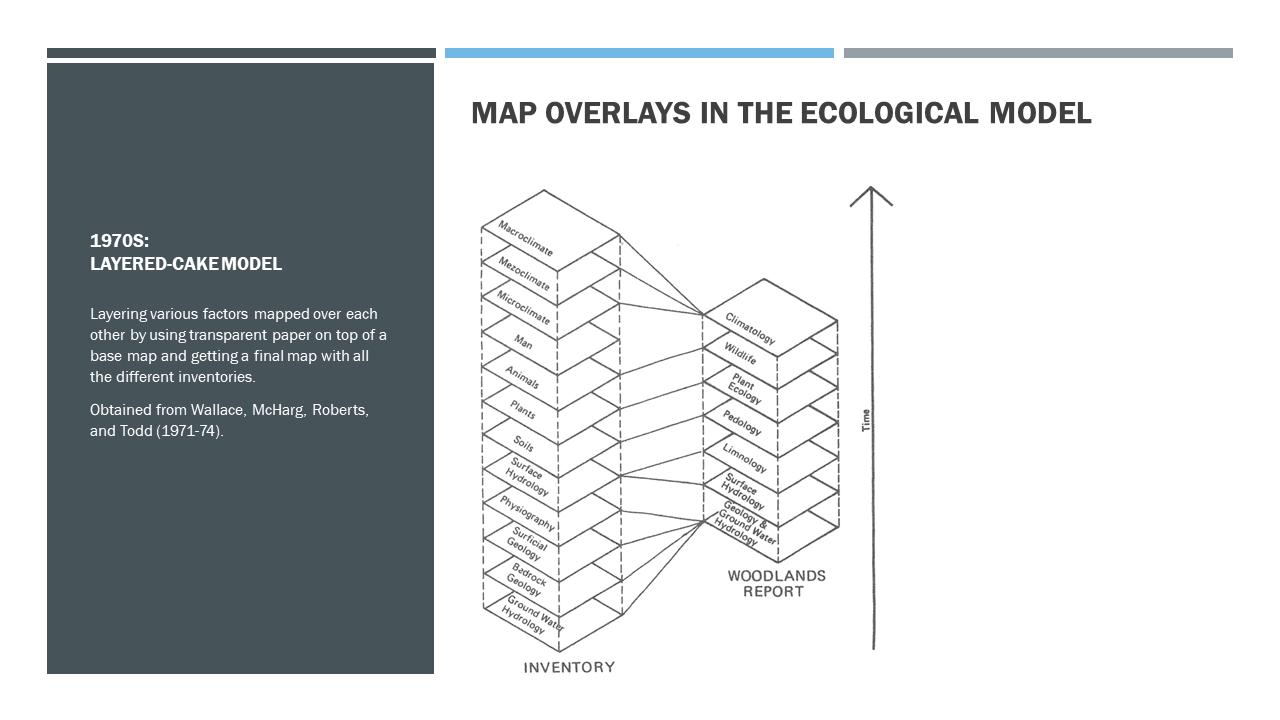

The map-overlay method was key to McHarg’s ecological model. This process spatially referenced the inventoried data and weighted its relative importance to design decision-making as part of the analysis. Originally, the map-overlay system involved layers of transparent film over a base map. Other types of transparent materials, and eventually the computer, replaced the film overlays. Each layer of film was dedicated to a single inventoried factor, such as topography or historic sites, which was rated from a high to low value. The darkest gradations of tones represented areas with the highest value and the lightest tones indicated areas with the least significant value. All of the mapped layers were then superimposed to create a composite map that in McHarg’s words looked something like a “complex X-ray photograph with dark and light tones” (1969, 35).

For McHarg, the composite map was where the truth was revealed. Development suitability was rated on the map from highest (lightest color) to lowest (darkest). According to McHarg, the integration of social and natural information across the site enabled designers to chart future development in ways that closely adhered to nature’s intrinsic progression towards stability. He augmented the map analyses with technical reports, suitability matrices, diagrammatic sections, decision

trees, and other techniques to reveal the natural processes of a site. Map overlay, however, is consistently attributed to McHarg’s ecological method.

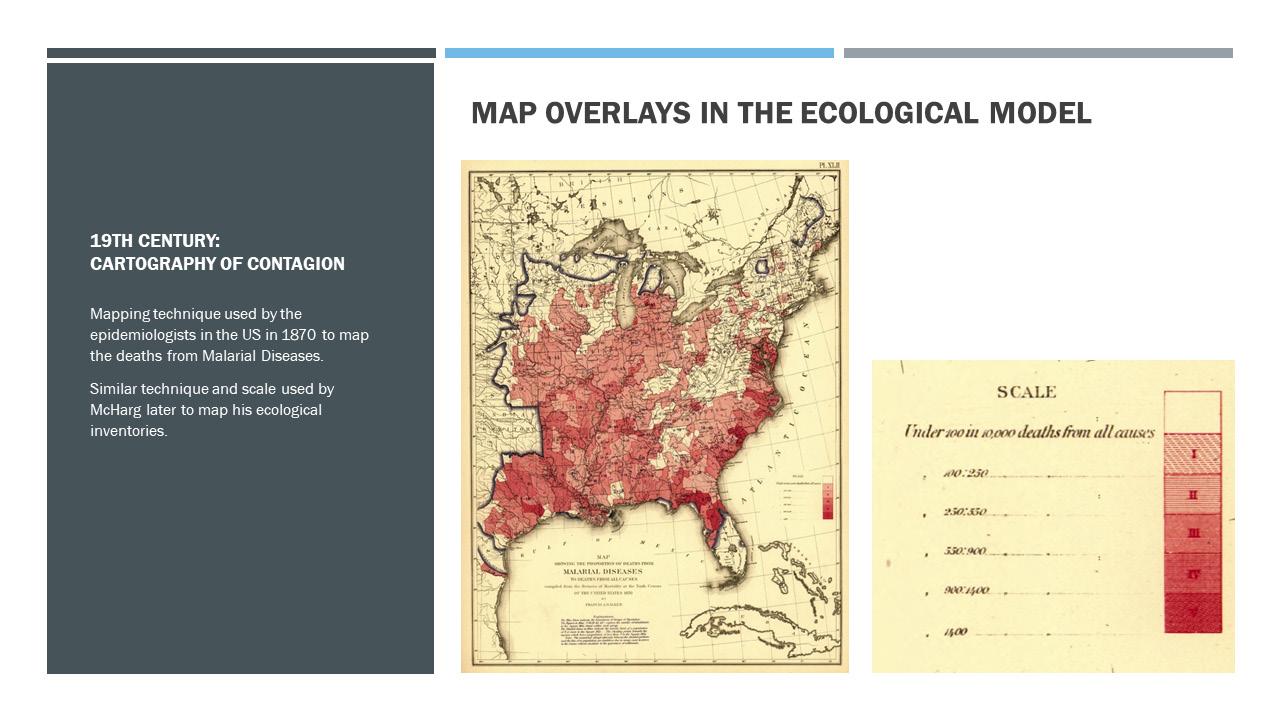

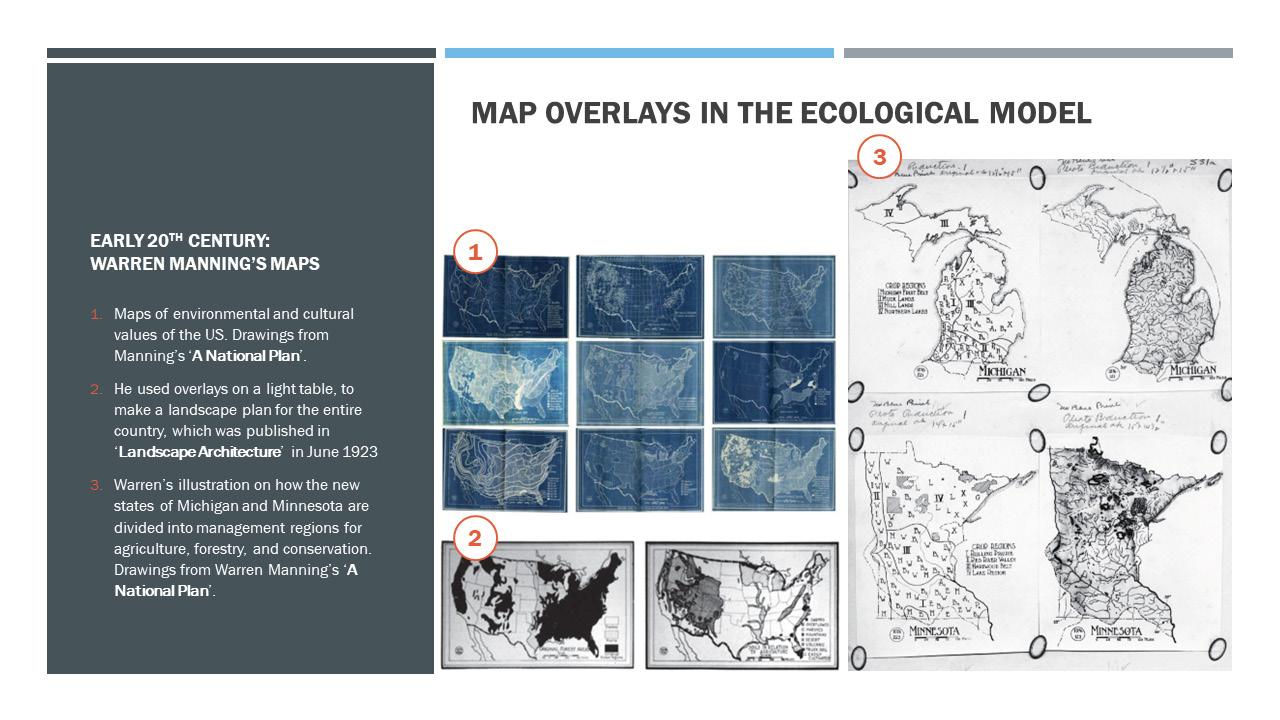

In the early 19th century, epidemiologists used similar mapping techniques to establish the location of contagions in cities (Tufte 1983, 27). Likewise, McHarg’s mapping method shares commonalities with the overlays employed by the U.S. Defense Department to determine target locations for intercontinental missiles during the Cold War (Cloud 2001, 203). In landscape architecture, the map-overlay method advanced by McHarg was similar to that used by Warren Manning in the early 20th century to record and classify site information (Zube 1986; Neckar 1989).8 In 1950 Jacqueline Tyrwhitt provided one of the first explicit descriptions of the map-overlay method in the design process in her book Town and Country Planning Textbook (Steinitz, Parker, and Jordan 1976, 445). Tyrwhitt was a professor at the Graduate School of Design in the Department of City Planning and Landscape Architecture at Harvard University from 1955 to 1969. While McHarg was not the inventor of the map-overlay method, he certainly championed it as no other individual before him.

McHarg introduced his method to landscape architects in 1965 in his Landscape Architecture article “Plan for the Valleys vs. Spectre of Uncontrolled Growth” with David Wallace. Examining and layering geological, topographical, economic, and a multitude of other factors, they demonstrated how planned growth could save seven million dollars as compared to uncontrolled growth (McHarg and Wallace 1965, 180). The mapoverlay method also features significantly in Design with Nature. There, McHarg structured the text so that chapters rife with condemnations of corrupt cities, Western values, rampant pollution, and urban pathologies alternated with chapters detailing the life-saving solutions of his map-overlay process. Many of these projects were completed with University of Pennsylvania students and his office, WMRT. Accompanied by God-like aerial views of the earth, these polychromatic maps revealed to readers how one might design with

nature, thereby locating intrinsically suitable locations for various types of development. The answer was simple—map it.

McHarg’s ecological method was both a “diagnosis and prescription” for development (Palmer 2001, Spirn 2000), and he believed it an objective procedure that could be replicated to produce the same outcomes. Describing the Woodlands project, to Landscape Architecture readers in 1975, McHarg and Jonathan Sutton noted, “Having accumulated and interpreted the biophysical data describing the region and [an] 18,000 a[cre] site, a method was developed which insured that anyone would reach the same conclusions . . . any engineer, architect, landscape architect, developer, and the client himself were bound by the data and the method” (McHarg and Sutton 1975, 78).

Later in life, McHarg was enthusiastic about the importation of his mapping method into computerized, geographic, information systems, exclaiming, “More data can be ingested, evaluated, and synthesized faster, and more accurately than ever before” (2006c; 1997, 119). He surmised that finally, the “computer will solve the command ‘show me the locations where all most propitious factors are located and most detrimental factors are absent’” (2006c; 1997, 118). To be sure, the computer fulfilled his quest for a systematic method of landscape design based on scientific data, but McHarg’s approach was also substantiated by scientific theories concerning evolution and adaptation.

As a means of lending scientific integrity to his ecological approach, McHarg developed a scientific theory called creative fitting that both explained and validated designing with nature. McHarg’s method was ecological not only because it used ecological data but also because the outcomes it produced matched the processes of adaptation and evolution. It helped determine where proposed human uses, such as buildings and roads, intrinsically fit on the land. Since this design method located the fittest environment for various land uses, it

also fulfilled the basic principles of adaptation (2006c; 1997, 124–125).

Adaptation. In McHarg’s words, the theory of creative fitting “has absolutely no status whatsoever, except insofar as all the parts have been derived from excellent scientists” (2007, 21). Indeed, creative fitting conjoined the scientific theories of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species (2003; 1859) and the lesser-known scientist Lawrence Henderson’s The Fitness of the Environment (1958; 1913). Creativity, for McHarg, was not an act exclusive to human artists but rather a directional process towards higher levels of order, which he thought occurred in the laws of both thermodynamics and evolution—in living and nonliving systems (2007, 22). McHarg defined fit as a blend of two scientific propositions: Charles Darwin’s idea that “the surviving organism is fit for the environment” (2007, 23) and Lawrence Henderson’s theory that “the actual environment, the actual world, constitutes the fittest possible abode for life . . . this fitting then is essential to survival, according to Darwin, and there is always a most fit environment for every system seeking an environment” (2007, 23–24). In 1981, McHarg wrote, “Every organism, system, constitution, is required to find the fittest environment, adapt that environment and itself in order to survive” (McHarg 1981, 93). In 1997, he again referred to his theory of creative fitting in a definition of ecological design:

Ecological design follows planning and introduces the subject of form. There should be an intrinsically suitable location, processes with appropriate materials, and forms. Design requires an informed designer with a visual imagination, as well as graphic and creative skills. It selects for creative fitting revealed in intrinsic and expressive form (McHarg 2006c; 1997, 123).

He concluded: “And, thanks to Charles Darwin and Lawrence Henderson, we have a theory” (2006c; 1997, 124).

Evolution. Creative Fitting also explained how McHarg’s ecological method produced outcomes matching the

trajectory of evolution. He anchored his theory of fit in the Darwin / Henderson combination, stating, “All systems are required to seek out the environment that is most fit, to adapt these and themselves, continuously . . . Systems which are fit are evolutionary successes; they are maximum success solutions to fitness” (2006b; 1978, 87). McHarg’s explanations of the Darwin / Hendersoninspired theory of creative fitting stressed that evolutionary progress, left to nature, moves towards some optimal point of success—that best evolutionary success is best defined by maximum fit solutions (McHarg 1969, 120; 1996, 245; 2007, 23).

This may be why the living and nonliving things, that were in McHarg’s view ‘unfit,’ drew his criticism. They did not fulfill what he deemed the optimizing directionality of adaptation. In defining what is unfit, McHarg (1969, 170) noted:

Our language conforms to this notion of the unfit as the unhealthy, crippled, deformed, although there may well be excellences that overcome this. Beethoven transcended deafness. So unfitness would include not only the broken piano, but also the defaced painting . . . the house in shade or the glaring street, the anarchic city; these are all unfit.

Stability. Another dimension concerning the outcomes of evolution and adaptation is the idea of stability as a benchmark of ecological health. McHarg argued that “stable and healthy forests, marshes, deserts, streams can be defined, that succession and retrogression can be identified” (2006a; 1966, 39). He further asserted: “Complexity, diversity, stability (steady state), with a high number of species and low entropy are indicators of health and systems moving in this direction are evolving” (1967, 107), and again attested that an increase in the number of species correlates with an increase in stability (2006g; 1968, 57). He concluded that ecological fitness must meet the evolutionary side (trending towards complexity and diversity) of the simplicitycomplexity, uniformity-diversity, instability-stability, independence-interdependence criteria (2006g; 1968,

60), and “on all counts the complex environment will be more stable”(1969, 120).

Design with Nature made its debut in 1969, and since then conceptions of nature, design, and science have developed in landscape architecture in myriad ways. Some of these changes have been the direct consequence of reinterpreting McHarg’s work. Without doubt he sustained a devout following, particularly among his past students. The landscape architecture office Andropogon Associates, founded by Carol Franklin, Colin Franklin, Leslie Sauer, and Rolf Sauer (McHarg’s former students), has produced award-winning landscapes in the name of “designing with nature.” On the teaching front, Ecology and Design: Frameworks for Learning (Johnson and Hill 2001) has revamped the role of ecological thinking in design education; some consider it the postscript of Design with Nature (Pittari 2003, 115).

Former students have also challenged McHarg’s autocratic views, expanding the scope and intent of his ecological message. Whereas McHarg viewed the city as the antithesis of nature, his former students, Anne Whiston Spirn and Michael Hough, found the urban environment brimming with natural systems worthy of our attention (Spirn 1984; Hough 1995). McHarg’s colleagues also countered some of his positions on the future of landscape architecture, bringing a humanist dimension to his ecological method. McHarg sought to make landscape design and planning a hard science (Olin 1999, 16). Laurie Olin, in both his practice with Robert Hanna and his teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, however, combined ecological concerns with artistic expression. When James Corner joined the University of Pennsylvania in 1988, he intentionally exploited the subjective beauty of maps. With Anu Mathur, Corner argued that maps were part of the repertoire of representational strategies used to generate “a catalytic

locale of inventive subterfuges for the making of poetic landscapes” (Corner 1992, 275).

Even the latest trend in landscape architecture— landscape urbanism—has ties to McHarg’s work. Richard Weller (2006) has posited that landscape urbanism must conjoin the rigor and conviction characterizing McHarg’s ecological method with the exquisite imagery and theoretical sophistication that defines Corner’s work. For Weller, “We are aptly reminded that landscape architecture is at best an art of instrumentality, or better still, an ecological art of instrumentality” (2006, 77). Indeed landscape urbanism shares commonalities with McHarg’s work, particularly its emphasis on graphic and analytic techniques, and its dependency on systems and strategy over form and design.

Critics of McHarg have frequently observed his disinterest in social issues. As early as 1971, Michael Laurie cautioned: “By his own admission McHarg barely touches upon social issues beyond the realm of survival” (206, 248). And yet some of the most serious criticism leveled at McHarg concerns his disdain for art and his low regard for site design, particularly at a garden scale. In Recovering Landscape, Marc Treib stated:

[McHarg] mixed science with evangelism—a sort of ecofundamentalism . . . McHarg’s method insinuated that if the process were correct, the consequent form would be good, almost as if objective study automatically gave rise to an appropriate aesthetic. In response to his strong personality and ideas, landscape architects jumped aboard the ecological train, becoming analysts rather than creators, and the conscious making of form and space in the landscape subsequently came to a screeching halt (1999, 31).

Given that Treib’s essay is the first chapter of Recovering Landscape, readers might wonder whether landscape architecture is recovering from McHarg. Spirn also noted:

When McHarg calls ecology “not only an explanation, but also a command,” he conflates ecology as a science (a way of describing the world), ecology as a

cause (a mandate for moral action), and ecology as an aesthetic (a norm for beauty). It is important to distinguish the insights ecology yields as a description of the world, on the one hand, from how these insights have served as a source of prescriptive principles and aesthetic values, on the other (2000, 112).

The following is an attempt to begin unraveling McHarg’s appropriation of science.

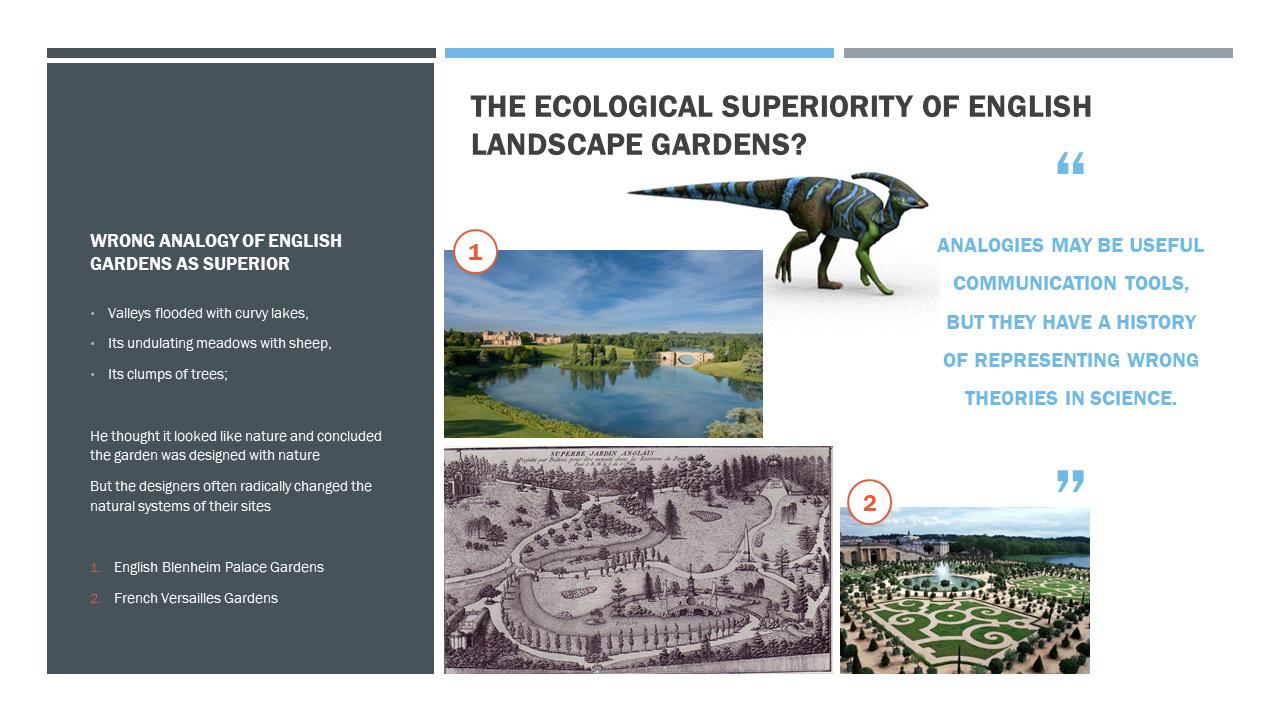

The Ecological Superiority of English Landscape Gardens?

As is evident in McHarg’s writings and lectures, the English landscape garden, compared with other historical gardens, served as a representational analogy for designing with nature. Analogies may be useful communication tools, but they have a history of representing wrong theories in science. For example, during the majority of the 20th century, paleontologists believed that duckbilled dinosaurs inhabited aquatic environments. The dinosaurs had bills and webbed feet like the ducks we see today, so it was postulated that they lived like ducks (Figure 4). As a result, professional publications, educational dioramas, and popular books displayed duckbilled dinosaurs, such as Corythosaurus, swimming in water or emerging from a murky swamp. Later examination of their fossilized remains, however, indicated that despite their ducklike appearance, these dinosaurs were not aquatic creatures but lived on land (Turner 2000).

McHarg’s analogy between designing with nature and English landscape gardens from the 18th century suffers in this way. The paleontologist sees the webbed feet and ducklike bill of the dinosaur. She thinks it looks like a duck and so concludes it was an aquatic animal. Likewise, McHarg saw an English landscape garden, its valley flooded with curvy lakes, its undulating meadows with sheep, its clumps of trees; he thought it looked like nature and concluded the garden was designed with nature. Despite appearances, duckbilled dinosaurs lived on land and the designers of English landscape

gardens often radically changed the natural systems of their sites.

This zeal for the superiority of English landscape gardens glosses over both the human and site subjugation resulting from their creation, placing in question their benefit to existing human populations and the natural systems of the site. For example, in his promotion of English landscape gardens, McHarg obliquely referred to the enclosure acts that made many of these gardens possible. He noted that, before the 18th century, agricultural patterns were awkward and unproductive: “Starting with a denuded landscape, a backward agriculture, and medieval pattern of attenuated land holdings, this tradition rehabilitated an entire countryside” (McHarg 1969, 72).

While enclosure generally was an economic success for landowners, it provided little appreciable benefit for the landless tenant farmers. Moreover, this success was largely due to technological advances in farming, and it came at the expense of people’s common rights. Enclosure acts disenfranchised the poor by forcing them to work as tenant farmers on the enclosed land or leave to find work elsewhere. As early as the 18th century, critics such as Mary Wollstonecraft condemned the enclosure acts. She argued that the exploitation of poor people for the sake of maximizing agricultural production and creating landscape gardens was inhumane (Bohls 2005, 145–146).

In the 20th century, Denis Cosgrove analyzed the impact of enclosure on farmers, noting:“ [A] majority saw their position eroded and their land slipping from their grasp as enclosure acts forced them to bear the costs of fencing and hedging while depriving them of crucial traditional sources of communal livelihood” (1998, 192). Cosgrove also stressed the division of space and labor in these enclosed lands. The tenants hired to maintain the plantings, statuary, and water features in landscape gardens were prohibited from using them. They could enter these spaces only as laborers. According to Cosgrove, “The 60 persons, for example, permanently employed to cater for Blenheim’s 2,500 acres, are entirely excluded from its ‘landscape’” (1998, 215).

In his Design with Nature (1969) chapter “On Values,” McHarg included a photograph of Blenheim Palace showing John Vanbrugh’s Grand Bridge crossing over Lancelot Brown’s flooded Glyme Valley (Figure 5). McHarg seems to have been unaware of the human labor that produced and maintained this landscape in noting that English landscape designers “used native plant materials to create new communities that so well reflected natural processes that their creations have endured and are self-perpetuating” (1969, 72). On the page with a photograph of the Blenheim Palace landscape, McHarg continued his promotion of English landscape gardens, noting the “water courses graced with willow, alder and osier, while the meadow supported grasses and meadow flowers” (1969, 73).

In actuality, Lancelot Brown made sweeping changes to the existing hydrology and terrain of the Blenheim Palace site. He did far more than plant trees and meadows at Blenheim. Starting in 1763, he redirected a major waterway, damned it, flooded the first floors of the Grand Bridge, wiped out Lady Sarah’s waterfall and canal, and after a succession of cascades redirected this water into the Thames River, “which he boasted would never forgive him” (Green 2000, 53). According to Clemens Steenbergen and Wouter Reh’s analyses of Brown’s work at Blenheim, “Its landscape seems to have been forged with a sledgehammer; it is a visual tour de force” (1996, 321). This certainly is a description correlative to dominating nature rather than designing with it. Moreover, Brown radically changed the hydrology and terrain on numerous other sites he designed.

This flawed view of certain historical landscapes representing designing with or without nature prevailed in McHarg’s lectures and writings. In 1997, in an essay for the American Society of Landscape Architects, McHarg surmised that Baroque gardens like Versailles sought to demonstrate man’s dominion over nature. This constitutes the worst possible admonition to the explorers who were then about to discover and colonize the earth. Anthropomorphism, dominion, and subjugation are better suited to suicide, genocide, and biocide than survival and success (1997, 105) More problematic,

some landscape architects persist in upholding these faulty representational analogies. John Dixon Hunt has noted that the profession continues to attribute rectilinear gardens with badness and serpentine gardens with goodness (2000, 212). This is due to the supposition that gardens that look like 18th-century English gardens are designing with nature and so are good, and that gardens that similar to Baroque or Renaissance gardens are not designing with nature and so are bad.

The Map-Overlay Process Is Like a Scientific Method?

The objectivity of maps. The mapping process so fundamental to McHarg’s method is also strangely at odds with his emphasis on nature as a dynamic process.9 The act of plotting static features as a way of designing with nature is inconsistent with the idea that nature is a phenomenon marked by gradual changes through a series of states. As Spirn has observed, the conflict between preservation and change is McHarg’s most persistent inconsistency (2000, 102).

Yet another problem with McHarg’s mapping process is his persistent claims to its objectivity. Although McHarg promoted the map-overlay method as an objective approach to design, the compilation of facts is not bias-free, and maps can be as subjective as other forms of depiction (Harley 1989a, 1989b, 1990; Wood 1992; Cosgrove 2008). In the classic text The Iconography of Landscape, J. B. Harley introduced maps as “part of the broader family of value-laden images” (1989b, 279). Tracing a history of mapmaking from the decorative maps of the 16th century to the “scientific phase” of mapping in the 20th century, Harley posited that maps are far from value-free. Moreover, 20th-century maps created under the guise of scientific disinterestedness— while free from heraldic banners, jewel encrusted compasses, or dueling Minotaurs—serve to legitimatize power relations.

These power relations are legitimized not only by what maps contain but also by what they omit—the silences of maps. According to Harley, “It is asserted here that maps—just as much as examples of literature—

exert a social influence through their omissions as much as by the features they depict and emphasize” (1989b, 290). For example, describing 17th-century maps of English estates in Ireland, surveyors often excluded the cabins of Irish families in their otherwise “accurate” maps. These omissions revealed not only religious tension but also the power of English landholders to expunge the Irish from their conceptualizations of the landscape. For Harley, “Silences on maps thus come to enshrine self-fulfilling prophecies about the geography of power” (292). What you see is what you get.

While Harley used historical maps to make his point, contemporary maps, including those created with computers, may further increase the disconnect between maps and the realities of a site.10 Contemporary maps “foster the notion of a socially empty space,” and computer generated maps lessen “the burden of conscience about people in the landscape” (Harley 1989b, 303).11 Critics wonder, “Are we really designing with nature, or are we simply addicted to our maps and the technology behind them?” (Dunstan 1983, 61)

Given that maps are not objective, this opens their creation to partiality. A latent bias in McHarg’s ecological method was his preference for low-density development as a desired outcome. WMRT’s Plan for the Valleys in Maryland; for Medford Township in New Jersey; and for The Woodlands in Texas endorsed lowdensity housing. In the plan for Medford, for example, single-family residences on lots bigger than one acre are weighted the highest and considered the best type of new development in comparison to all other densities. Throughout Design with Nature, McHarg advocated the spacious countryside and its scenic qualities over denser, urban living.

To legitimatize his preference for low density, McHarg referred to John Calhoun and Jack Christian’s work on crowding in rat populations and the theory of pathological togetherness. In Design with Nature, McHarg warned of the direct relationship between high density and a decline in the size of litters, deformed young, and ultimately the “failure of the mothers to provide milk, and cannibalism” (1969, 193). McHarg

applied the findings of Calhoun and Christian, whose rats were living in conditions of extreme crowding, in his ecological model of Philadelphia. Mapping a range of factors from ethnic distribution, density and economic factors to various social diseases, he conjoined high density with pathology, noting, “It’s premature to predict correlations. The single obvious one is poverty, but density—indeed the adjacent population map bears a remarkable correspondence to the pattern of pathology” (193). With the rise of cluster housing and later new urbanism, low-density housing has been associated with increased dependence on cars, a diffusion of single-function infrastructure, and greater ecological disturbances. Yet, even in his 25th anniversary edition of Design with Nature, McHarg did not change his stance on dense living and the city.

McHarg was aware of the cultural biases of mapmaking. In his biography, Quest for Life, he revealed how race played a role in the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority project. He noted: “[A] covert value system was being utilized in conjunction with an overt ecological inventory” (1996, 340). While how he avoided this covert value system is unclear, he claimed that for this project, like others, the “process was overt, explicit, and replicable, just like a scientific experiment” (1996, 341).

McHarg’s belief in the objectivity of maps was deeply entrenched in culture. As Monmonier noted: “Map users are generally a trusting lot . . . they readily entrust map-making to a priesthood of technically competent designers and drafters” (Monmonier 1996, 1). Developers deploy the presumed objectiveness of map analyses purposely to lie in ways that do not benefit the environment or the local people (Monmonier 1996).

Inaccurate and diverse data. Monmonier has posited that all maps contain lies. These lies are not always intentional but can be attributed to the inaccuracies of |the data, particularly with imprecise resource-related data. Data sources commonly used in landscape planning and design (for example the Unites States Geological Survey) are often flawed, as are procedures for compiling these data. For example, according to

Monmonier, “Floodplains defined locally by a single elevation tend to include either too much or too little of the real flood plain” (1996, 76). Cosgrove also scrutinized the conflation of knowledge and mapmaking, noting that the graphic power of McHarg’s maps lies in their ability to calculate claims about phenomena that escape normal bodily experiences (2008, 168). For example, it’s not always possible to experience the intersection of bedrock geology and residential values on a site. This situation, however, often forces mapmakers to use secondary sources subject to the types of inaccuracies cited by Monmonier. Inaccurate data hinders the type of scientific rigor that McHarg aspired to achieve with his overlay method.

Another problem with the map-overlay method is the notion that physical values, such as information gleaned from a soil boring, may be operationalized the same way that cultural values, such as historical significance, may be. McHarg’s method was attacked for giving too much weight to science instead of intuition (Spirn 2000). Critics, wrote Spirn, “lose sight of the most important aspects of the ecological inventor—its systematic comprehensiveness and the relation of different aspects of the environment” (2000, 108). The breadth of issues and values that the map-overlay method could address was unprecedented. But the ability to integrate biophysical features as well as cultural factors through the Cartesian sieve of the overlay method overlooked the complexity of cultural issues.

In Design with Nature, the location of a highway provides the first example of the map-overlay method at work. Information like bedrock conditions, slopes, and soils conditions are rated—low suitability (Zone 1), medium suitability (Zone 2), or high suitability (Zone 3) for road construction. Soil values, for example, ranks silts and clay soils areas low, and these areas are portrayed in darker tones. Sandy loams are ranked medium, and these areas are of a mid-range tone. Gravelly sand or silt loams and gravelly to stony sandy loams are rated high and given the lightest tone because these soils are good for roadway construction.

In the same study, but on different layers, the rating approach is applied to cultural criteria such as residential, institutional, and scenic values. Residential values, for example, are marked low for road construction suitability where the market value of housing is more than $50,000, medium for houses valued between $25,000 and $50,000, and high for road-construction suitability in areas with houses under $25,000. This ranking raises concerns about social inequities in the map-analysis procedure. Why are the wealthier homeowners permitted to hide in the shadows of the darker tones? Moreover, when people living in inexpensive housing exist on the same tonal plane as gravelly sand, how is this designing with nature? McHarg admitted that this example privileges the wealthy but surmised that it nevertheless is a success because the method is explicit (1969, 40).

Scientific proof. McHarg consistently referred to the map-overlay method as an ecological model that was scientifically defensible. Scientific approaches to understanding the world are based on the following four elements:

1. observation of specific facts or phenomena

2. formulation of generalizations about such phenomena

3. production of causal hypotheses relating different phenomena

4. testing of the causal hypotheses by means of further observation and experimentation (Pigliucci 2002, 128–129).

McHarg argued for this positivist conception of landscape architecture. He thought that design and planning solutions, like those in science, should be verified for their ecological integrity. As early as 1965, he outlined the data collection and mapping for his new ecological model in his lecture “Ecological Determinism.” According to McHarg, these procedures included six steps:

ecosystem inventory

description of natural processes

identification of limiting factors

attribution of value

determination of prohibitions and permissiveness to change

identification of stability or instability (2006a; 1966, 24)

By 1967 McHarg expanded the last step to a set of binary ecological criteria by which design outcomes could be affirmed as positive or negative, bringing his methodology into complete alignment with positivist thinking.

During the early 1990s landscape architects criticized McHarg’s unequivocal endorsement of mapoverlays and GIS as a positivist method. Some argued that these approaches to design were incapable of considering the rich array of cultural aspects comprising landscapes. In 1991, James Corner identified positivism as a tyranny in landscape architecture. Corner described the positivist tyranny as one grounded in science, based on descriptions and explanation of design processes, and overly methodological. For Corner, “one only has to plow through the complex matrices of Christopher Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form (1964) or to look at the exhaustive collection of data involved in McHarg’s suitability analyses to see the laborious nature of such an enterprise” (1991, 117). The tyranny for Corner, however, was not the voluminous amount of work but the notion that the data itself would automatically guide designers to a credible solution.

The problem raised here concerns the lack of proof substantiating the ecological superiority of McHarg’s method. While McHarg championed that the outcomes of his method could be verified, there have been few systematic assessments of his built projects. In the 1970s the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development hailed The Woodlands, WMRT’s award winning project in Texas, as a great success (Morgan and

King 1987, 142–143). Other awards followed, but the project gained its fame as an application of McHarg’s ecological approach conjoined with The Woodlands’ status as a Housing and Urban Development New Town (Morgan and King 1987, 149), not through the replication and testing of the design solution.

Landscape architects have studied the project as well. In the 1990s, Cynthia Girling and Kenneth Helphand found that subsequent developments in The Woodlands did not McHarg’s signature open-swale system. Instead, by 1985, development there used the conventional curb-and-gutter system (Girling and Helphand 1994, 166–167). Urban designer Ann Forsyth found that residents complained about the wild look of the open swales and that some thought the focus on hydrology diminished the importance of maintaining corridors for wildlife (Forsyth 2003, 13). These studies, however informative, probably are not the rigorous scientific testing McHarg envisioned.12

Evaluations of McHarg’s design solutions compared with those of ecological health could help determine whether his model is scientifically credible. We learn from mistakes—the identification of ecological failures in his solutions would suggest adjustments to his method. This certainly was not lost on McHarg. He noted in Design with Nature: “We can accept that scientific knowledge is incomplete and will forever be so, but it is the best we have and it has that great merit, which religions lack, of being self-correcting” (1969, 29). Nonetheless, even if we used McHarg’s ecological criteria to self-correct—to check whether his method produced landscapes of great ecological integrity compared to other methods—there are problems with some of his ecological theories. These ideas are noteworthy because they have permeated both professional and academic thinking in landscape architecture.

The illusion of design. While Darwin- and Hendersoninspired theory occupy McHarg’s ecological thought for more than 30 years, his interpretations of their work were not entirely accurate. McHarg was clearly captivated

by Henderson’s recounting of how the world became fit for life. Henderson’s The Fitness of the Environment (1958) is a classic text explaining how hydrogen and oxygen and their particular characteristics make possible the production of living protoplasm, and thus, a fit condition for life. Be that as it may, scientists seriously questioned Henderson’s foray into the metaphysical implications of his work—an explanation of who or what was designing this earth for life (Mendelsohn 2008).

Some readers of The Fitness of the Environment, like McHarg, found that Henderson’s theories validated the idea that there was a design for earth, which made it fit for “every form of life that has existed, does now exist, and all imaginable forms” (McHarg 2007, 23).13 According to historian Everett Mendelsohn, Henderson did not believe there was a grand designer for earth’s natural systems, and he spent a significant portion of his career defending and explaining his metaphysical claims. In a letter cited by Mendelsohn, Henderson contended:

What I maintain is that there is a pattern in the ultimate properties of the chemical elements and in the ultimate physiochemical properties of all phenomena considered in relation to each other. I do not mean to say that this pattern is exactly of the same nature as the pattern of a watch or an organism. Still less do I mean to say or to imply anything about design of mind. The only minds that I know are the minds of the individual organisms that I encounter upon the earth (Mendelsohn 2008, 10).

In this letter Henderson argued against an interpretation of his work claiming that natural organisms are designed by some God-like mind. Richard Dawkins has called this misinterpretation “the illusion of design” (1996, 3–4). Since some things in the world—the beautiful symmetry of a butterfly for example—appear to have been designed, some argue that they must have been intentionally designed by an intelligent being. According to Dawkins, “Natural selection is the blind watchmaker, blind because it does not see ahead, does not plan consequences, has no purpose in view” (1996, 21). Since Henderson proposed that the earth was designed

for life, for some people this suggested a grand designer in the wings. Unfortunately for the atheist Henderson, Intelligent Design enthusiasts cite his metaphysical accounts more often than scientists do (Denton 1998).

McHarg was not an Intelligent Design advocate, but God held a spectral presence in his thinking on nature and science. His writings and lectures are laced with religious overtones of heresy, good, evil, and a perpetual guilt that our brains make humans a planetary disease. McHarg (1996) implied that God praises the ecological designer over others. Even his film Multiply and Subdue the Earth suggests his disillusionment with the frequently cited line from Genesis: “So God created man in his own image . . . and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it’” (Bible 2007). In an interview in 1976, McHarg remarked, “So far as I’m concerned, ecology is a kind of heavy-footed religion. It’s a religious quest, this idea about something that unites all rocks, plants, animals and men” (MY 1976, 109).

Through history, scientists have been theists or atheists, but McHarg’s desire to find a purpose and unity in nature’s design muddles the science in his theory of creative fitting. On one hand he promoted a scientist’s view of adaptation regarding evolution. On the other, he was unwilling to accept the remorseless Darwinian prognosis that the world had evolved with no grand design. Even if we choose to believe that nature has a design, with creative fitting as its proof, there are problems with the outcome of its plan, particularly with regard to optimization and balance.

Optimization. The process of adaptation involves the mutation of genes, which is random, so there is no bias towards improvement. Dawkins asked, “How on earth is mutation supposed to ‘know ’ what will be good . . . by what mysterious built-in wisdom does the body choose to mutate in the direction of getting better, rather than worse? (1996, 305–306). The desire to believe that adaptation is moving towards greater improvement is simply that, a belief, and has never been verified.

Like his interpretation of Henderson’s work, McHarg’s ideas about adaptation may have been more influenced by religious ideas. According to Stephen Jay Gould, “[A] popular impression regards Darwin’s principle of natural selection as an optimizing force, leading to the same end of local perfection that God had supplied directly in older views of natural theology” (1997, 5). In Western cultures, where scientific ideas have replaced natural theology with Darwin as the mainstay, evolutionary theories have been frequently misinterpreted as attaining theology’s end game. This certainly explains McHarg’s misinterpretation of Darwin, but how did it affect the profession he so profoundly changed?

Landscape architects continue to suffer from this misreading of Darwin with regard to native plants. The argument follows that since native plants lived in North America before Western settlement, they existed in a natural state and thus must have naturally evolved as the best-adapted plants for their given location. Biologists have pointed out that natural selection is only a “better than” principle, not an optimizing device (Gould 1997, 6). Nonetheless, students of landscape architecture often claim that native plants are the best-adapted plants for a landscape. One can hardly blame them. Not only did McHarg roll out a version of adaptation optimization but advocacy groups and nurseries also began selling native plants, “confirming” the theory.

Natural balance. According to McHarg, another criterion for creative fitting is a stable ecosystem. Stability, however, has been one of the most contested criterions for describing a healthy ecosystem. The idea of a stable, balanced natural state may be traced back to natural philosophy in the 18th and 19th centuries. By the 1930s, however, numerous ecologists found “there was no evidence of ecological stability in unexploited natural populations or communities” (McCoy and Shrader-Frechette 1992, 188). Healthy ecosystems did not necessarily exhibit stability or balance. In the 1950s, stability was replaced by dynamic balance, and is sometimes used by present-day interpreters of McHarg’s work (Sagan 2006, 82). This proved to be as difficult

to substantiate as balance, stability, and steady-state (McCoy and Shrader-Frechette 1992, 185). According to McNaughton, “Continued assertions of the validity of one or another conclusion about diversity-stability, in the absence of empirical tests, are acts of faith, not science” (1977, 515). Notions of balanced nature and stability principles have misrepresented the foundations of resource management, nature conservation, and environmental protection (Wu and Loucks 1995, 439).

McHarg attributed his definition of stability to Robert MacArthur (1967, 107), a frequent guest in his classes (McHarg 1996, 137). In a retrospective of MacArthur’s contributions to ecology, Stephen Fretwell has speculated on why this respected scientist upheld the idea of stability as a benchmark for healthy ecosystems, surmising that his “work surrounding stability and diversity was what everyone wanted to hear in the thenbudding ecology movement” (1975, 7). Perhaps McHarg faced a similar situation.

Like optimization, religious thought rather than science may have influenced McHarg’s views on natural balance. Frederick Turner has posited that many environmental concepts about nature are still infused with religious beliefs, noting: “Very often the environmentalist’s ideas of nature retains these characteristics of the transcendent God . . . The basic feature of nature is homeostasis . . . nature in this view has an ideal state, which is perfect and should not be tampered with” (1993, 38–39).

This belief in natural balance and evolutionary stability continues to permeate landscape architecture and its educational institutions. Consider the 2005 International Federation of Landscape Architects Charter For Landscape Architectural Education. It states that landscape architects will engage in “the conservation and enhancement of the built heritage, the protection of the natural balance and rational land use planning for the utilization of available resources.”14 Or think of the numerous concept statements by landscape architecture students explaining how their designs will restore nature’s balance.

The contradictions and inaccuracies do not detract from the spectacular advancements McHarg made in landscape architecture and society in general. Rather, they suggest his work be contextualized historically. Recent books on McHarg are unwavering in their admiration of him. Frederick Steiner has suggested: “Ian McHarg’s ideas about ecologically based design, human ecology, and national and global inventories remain crucial to our futures” (2006, xiv). David Orr has noted: “McHarg’s vision of humankind and nature in harmony . . . may help a generate wisdom and foresight amongst your peers” (2007, 14). McHarg certainly deserves this recognition, but without a historical critique of McHarg’s ideas, we lose the opportunity to understand McHarg’s place in history. We also fail to learn from the other fields that he relied upon in his work.

This is true of the sciences as well as of history. According to Michael Graham and Paul Dayton, scientific knowledge is a dynamic process; they caution that when ecologists loose touch with their historical roots, they “face a greater likelihood of recycling ideas and impeding scientific momentum” (2002, 1481). This caution applies to landscape architecture, too. For example, if we continue to maintain that maps are an objective form of depiction, we too risk repeating the past and hindering knowledge about landscapes. This is not to say we should abandon GIS or the map-overlay method. Maps are extremely useful and efficient forms of communication, but they must be presented to students with this awareness that they are not bias free. Like a perspective sketch, they illustrate a point of view, and in doing so they leave things out.

Why did McHarg not keep up with current research on evolution and ecology? Despite 25 years of changes in science and landscape architecture, the 1992 edition of Design with Nature is virtually identical to the 1969 edition. Perhaps, as with MacArthur, whom McHarg so admired, people liked what they heard. The environment was in crisis, and he had a solution that felt right. Likewise, why was McHarg’s ecology more like a “heavy-

footed” religion? The son of a minister, McHarg perhaps was inclined to measure the relations between organisms and their environment in terms of divine sources of truth and goodness. But May have been due to the scale of the questions he asked. McHarg wanted to know how we are part of a larger, God-like scheme and how the values and commitments we share might be garnered to maintain this it. The answers to this question are surely most suited to religious speculation.

Spirn has remarked: “It is difficult to imagine what landscape architecture would be like today without the presence of Ian McHarg, his publications, teaching, and professional projects.” (2000, 114). Indeed he was a powerful and complex figure in the history of landscape architecture. McHarg seized some of the most the crucial issues of his times and unearthed them in a powerful method for landscape architects. He challenged us to take a stand in protecting the natural environment. In short, he asked us to care, which is surely a substance not only of science and religion but also of reason.

I thank Judith Major, Thaisa Way, and the Landscape Journal reviewers and editors for their helpful comments on this paper.

1. Portions of this article were presented on April 25, 2008, in a session on landscape architecture and science (chaired by Judith Major and Joy Stocke) at the Society of Architectural Historians Annual Conference in Cincinnati.

2. See Spirn 2000. According to Steiner in The Essential Ian McHarg (an excellent collection of McHarg’s writings and lectures prefaced by Steiner’s introductions), “The dictum ‘design with nature’ not only changed design and planning but also influenced fields as diverse as geography, engineering, forestry, and environmental ethics, soil science, and ecology” (Steiner 2006, xiii).

3. McHarg also produced a film, Multiply and Subdue the Earth (Hoyt, Blau, and McHarg 1969). See also Walker and Simo 1996.

4. Where two publication dates are referenced, republication date is followed by the original publication date.

5. This self-description is from Margulis, Corner, and Hawthorne 2006, an edited transcription of McHarg’s conversations with students. For the complete recordings, see Margulis, MacConnell, and MacAllister 2006.

6. In Design with Nature McHarg attempted to reconcile the Le Nôtre-inspired plan of Washington, DC. He noted, “It is something of a paradox that the image of the city, most appropriate of kings, became the expression for that confederacy, which was to become a great democracy” (McHarg 1969, 181). He was even more surprised that L’Enfant’s plan used the geomorphology of the site to locate major structures and align them with other major landscape features (1969, 183).

7. Ernst Haeckel coined the term ecology or oekologie in 1876, and ecological science emerged as a branch of biology devoted to the study of organisms’ relationship to each other and to the physical environment in which they live.

8. For a brief history of the map-overlay method in landscape architecture, see Steinitz, Parker, and Jordan 1976.

9. I thank a Landscape Journal reviewer for pointing this out.

10. Critiques of the maps produced through GIS appear extensively in geography literature. See Harvey 2000, Taylor 1991, Taylor and Johnston 1995, and Openshaw 1991 and 1992.

11. Denis Wood has posited that since maps bring out contested issues, they can provide a discursive territory that also provides an opportunity to debate what they dispute (1992, 19).

12. The Woodlands Corporation funded a hydrological study to determine whether WMRT’s unique design mitigated flooding. Using the 1978 plan and a mathematical model (HEC1), it found that ”the hydrological impacts were minimized” (Bedient et al. 1985, 550).

13. Admitting he may have overstepped the boundaries of science, Henderson wrote: “It is evident that a perfect mechanistic description of the building of a house may be conceived. Yet such design and purpose, whether or not in themselves of mechanistic origin, are at one and the same time determining factors in the result” (1958, 307). One can imagine this line appealing to McHarg, the combining of design and purpose perhaps foreshadowing his television series The House We Live In.

14. The complete August 15, 2005, version reads: “It is in the public interest to ensure that landscape architects are able to understand and to give practical expression to the needs of individuals, communities, and the private sector regarding spatial planning, design organization, construction of landscapes, as well as conservation and enhancement of the built heritage, the protection of the natural balance, and rational

land-use planning for the utilization of available resources” (IFLA, 2005).

Alexander, Christopher. 1964. Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard. University Press.

Bedient, Philip, Alejandro Flores, Steven Johnson, and Plato Pappas. 1985. Floodplain storage and land use analysis of The Woodlands, Texas. Water Resource Bulletin 21 (4): 543–552.

Bible (Revised Standard Version). 2007. Genesis I, 11: 26–28. http: // quod.lib.umich.edu / cgi / r / rsv / rsv-idx?type=DIV1 &byte=1801 [December 20, 2007].

Bohls, Elizabeth. 2005. Travel Writing, 1700–1830: An Anthology. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Cloud, John. 2001. Hidden in plain sight: The CORONA reconnaissance satellite programme and the Cold War convergence of the earth sciences. Annals of Science 58 (2): 203–209.

Corner, James. 1991. A discourse on theory II: Three tyrannies of contemporary theory and the alternative of hermeneutics. Landscape Journal 10 (2): 115–133.

———. 1992. Representation and landscape: Drawing and making the landscape medium. Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal /Visual Enquiry 8 (3): 243–275.

Cosgrove, Denis. 1998. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

———. 2008. Geography and Vision: Seeing, Imagining and Representing the World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Darwin, Charles. 2003. On The Origins of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview.

Dawkins, Richard. 1996. The Blind Watchmaker: Why Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design. New York: Norton.

Denton, Michael. 1998. Nature’s Destiny: How the Laws of Biology Reveal Purpose in the Universe. New York: Free Press.

Dunstan, Joseph. 1983. Design with Nature: 14 years later. Landscape Architecture: 73 (1): 59, 61.

Forsyth, Ann. 2003. Ian McHarg’s Woodlands: A second look. Planning August: 10–13.

Fretwell, Stephen. 1975. The impact of Robert MacArthur. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 6: 1–13.

Girling, Cynthia L., and Kenneth I. Helphand. 1994. Yard, Street, Park: The Design of Suburban Open Space. New York: Wiley.

Gould, Stephen Jay. 1997. An evolutionary perspective on strengths, fallacies, and confusions in the concept of

native plants. In Nature and Ideology: Nature and Garden Design in the Twentieth Century, ed. Joachim WolschkeBulmahn, 11–19. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. Graham, Michael and Paul Dayton. 2002. On the evolution of ecological ideas: Paradigms and scientific progress. Ecology 83 (6): 1481–1489. Green, David. 2000. Blenheim Palace. Norwich: His Grace the Duke of Marlborough and Jarrold Publishing.

Harley, J. Brian. 1989a. Deconstructing the map. Cartographica 26 (2): 1–20. ———. 1989b. Maps, knowledge, and power. In The Iconography of the Landscape, ed. Denis Cosgrove and Steven Daniels, 277–312. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1990. Cartography, ethics and social theory. Cartographica 27 (2): 1–23.

Harley, J. Brian, and David Woodward. 1987. History of Cartography: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harvey, Francis. 2000. The social construction of geographic information systems. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 14, 713–716. Hedgpeth, Joel W. 1986. Man and nature: Controversy and philosophy. The Quarterly Review of Biology 61 (1): 45–67. Henderson, Lawrence. 1958. The Fitness of the Environment: An Inquiry into the Biological Significance of the Properties of Matter, intro. George Wald. Boston: Beacon. Hough, Michael. 1995. Cities and Natural Process. London: Routledge.

Hoyt, Austin, Ron Blau, and Ian L. McHarg. 1969. Multiply and Subdue the Earth. Boston: WGBH Educational Foundation. Hunt, John Dixon. 2000. Greater Perfection: The Practice of Garden Theory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA). 2005. Charter for landscape architectural education. http: // www.iflaonline.org / images / PDF / education / ifla_la educationcharter_082005.pdf [September 26, 2009] Johnson, Bart R., and Kristina Hill, eds. 2001. Ecology and Design: Frameworks for Learning. Washington, DC: Island. Laurie, Michael. 1971. Scoring McHarg: Low on methods, high on values. Landscape Architecture 61(3): 206–248. Margulis, Lynn, James Corner, and Brian Hawthorne, eds. 2006. Ian McHarg Conversations with Students. New York: Princeton Architectural. Margulis, Lynn, Adam MacConnell, and James MacAllister, eds. 2006. The Lost Tapes of Ian McHarg Collaboration with Nature. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green.

McCoy, Earl D., and Kristin Shrader-Frechette. 1992. Community ecology, scale, and the instability of the stability concept. PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association.

McHarg, Ian L. 1967. An ecological method for landscape architecture. Landscape Architecture 57 (2): 105–107.

———. 1969. Design with Nature. New York: Natural History. ———. 1971. Man: Planetary Disease (full text at http: // www .eric.ed.gov:80 / ERICWebPortal / contentdelivery / servlet / ERICServlet?accno=ED061052). Y.B. Morrison Memorial Lecture. Portland, Oregon. March 10, 1971 [September 26, 2009].

———. 1980. The garden as a metaphysical symbol: the Reflection Riding Lecture. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 128 (5283): 132–143

———. 1996. A Quest for Life: An Autobiography. New York: Wiley. ———. 2006a. Ecological determinism. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 30–46. Washington, DC: Island. Originally published in John P. Milton, ed. 1966. The Future Environments of North America, 526–538. New York: Natural History. ———. 2006b. Ecological planning: The planner as catalyst. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 86–89. Washington, DC: Island. Originally published in Robert W. Burchelland and George Sternlieb, eds. 1978. Planning Theory in the 1980s (2nd ed. 1983), 13–15. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Center for Urban Policy Research.

———. 2006c. Ecology and design. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 122–130. Washington, DC: Island. Originally published in George F. Thompson and Frederick R. Steiner, eds. 1997. Ecological Design and Planning, 321–332. New York: Wiley.

2006d. Human ecological planning at Pennsylvania. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 90–103. Washington, DC: Island. Originally published in 1961, Landscape Planning 8: 109–120.

———. 2006e. Landscape architecture. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 104–109. Washington, DC: Island. Originally a reflective essay for The American Society of Landscape Architects lectures.

———. 2006f. Man and environment. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 1–14. Washington, DC: Island. Originally published in Leonard J. Duhl and John Powell, eds. 1963. The Urban Condition, 44–58. New York: Basic.

———. 2006g. Values, process, and form. In The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature, ed. Frederick R. Steiner, 47–61. Washington, DC: Island. Originally published in The Smithsonian Institution Staff, eds. 1968. The Fitness of Man’s Environment, 207–227. New York: Harper and Row.

———. 2007. Theory of creative fitting. In Ian McHarg: Conversations with Students: Dwelling in Nature, ed. Lynn Margulis, James Corner, and Brian Hawthorne, 19–62. New York: Princeton Architectural. Undated lecture.

McHarg, Ian L., and Jonathan Sutton. 1975. Ecological plumbing for the Texas Coastal Plain. Landscape Architecture 65 (1): 78–89.

McHarg, Ian L., and David Wallace. 1965. Plan for the valleys vs. spectre of uncontrolled growth. Landscape Architecture 55 (3): 179–181.

McNaughton, Samuel J. 1977. Diversity and stability of ecological communities: A comment on the role of empiricism in ecology. The American Naturalist 111 (979): 515–525. Mendelsohn, Everett. 2008. Locating “fitness” and Lawrence J. Henderson. In Fitness of the Cosmos for Life: Biochemistry and Fine-Tuning, ed. John D. Barrow, Simon Conway Morris, Stephen J. Freeland, and Charles L. Harper Jr., 3–19 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Monmonier, Mark. 1996. How to Lie With Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Morgan, George T., and John O. King. 1987. The Woodlands: New Community Development 1964–1983. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

MY (anonymous). 1976. What Do We Use for a Lifeboat When the Ship Goes Down? New York: Harper and Row. Neckar, Lance. 1989. Developing landscape architecture for the twentieth century: The career of Warren H. Manning. Landscape Journal 8 (2): 78–91.

Olin, Laurie. 1999. Across the Open Field. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Openshaw, Stan. 1991. A view on the GIS crisis in geography, or, using GIS to put Humpty-Dumpty back together again. Environment and Planning A 23: 621–628.

———. 1992. Further thoughts on geography and GIS: a reply. Environment and Planning A 24: 463–466.

Orr, David. 2007. The “quasi-pseudo-crypto-scientist.” In Ian McHarg Conversations with Students, ed. Lynn Margulis, James Corner, and Brian Hawthorne, 9–14. New York: Princeton Architectural. Palmer, Joy. 2001. Fifty Key Thinkers on the Environment. New York: Routledge.

Pigliucci, Massimo. 2002. Denying Evolution: Creationism, Scientism, and the Nature of Science. Sutherland, MA: Sinauer. Pittari, John, Jr. 2003. Review of ecology and design: Frameworks for learning. Journal of Planning Education and Research 23: 113–115.

Sagan, Dorion. 2006. “The algae will laugh”: McHarg and the second law of thermodynamics. In Ian McHarg Conversations with Students, ed. Lynn Margulis, James Corner, and Brian Hawthorne, 79–84. New York: Princeton Architectural.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. 1984. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. New York: Basic.

———. 2000. Ian McHarg, landscape architecture, and environmentalism: Ideas and methods in context. In Environmentalism and Landscape Architecture, ed. Michel Conan, 97–114. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. Steenbergen, Clemens, and Wouter Reh. 1996. Architecture and the Landscape. Brussum, The Netherlands: Prestel. Steiner, Frederick R., ed. 2006. The Essential Ian McHarg: Writings on Design and Nature. Washington, DC: Island. Steinitz, Carl, Paul Parker, and Lawrie Jordan. 1976. Hand-drawn overlays: Their history and prospective uses. Landscape Architecture 66 (5): 444–55.

Taylor, Peter J. 1991. A distorted world of knowledge. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 15: 85–90. Taylor, Peter J., and Ronald J. Johnston. 1995. GIS and Geography. In Ground Truth: The Social Implications Of Geographic Information Systems, ed. John Pickles, 51–67. New York: Guilford.

Treib, Marc. 1999. Nature recalled. In Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture, ed. James Corner, 29–44. New York: Princeton Architectural.

Tufte, Edward. 1983. Visual Explanations Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphic Press.

Turner, Derek. 2000. The functions of fossils: Inference and explanation in functional morphology. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Biological and Biomedical Sciences 31 (3): 193–212. Turner, Frederick. 1993. The invented landscape. Beyond Preservation: Restoring and Inventing Landscapes, ed. Dwight Baldwin and Judith DeLuce, 35–66. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Walker, Peter, and Melanie Simo. 1996. Invisible Gardens The Search for Modernism in the American Landscape, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 273–275. Weller, Richard. 2006. An art of instrumentality: Thinking through landscape urbanism. In The Landscape Urbanism Reader, ed. Charles Waldheim, 69–86. New York: Princeton Architectural. Wood, Denis. 1992. The Power of Maps. New York: Guilford. Wu, Jianguo, and Orie L. Loucks. 1995. From balance of nature to hierarchical path dynamics: A paradigm shift in ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology 70 (4) 439–466. Zube, Ervin H. 1986. The advance of ecology. Landscape Architecture 76 (2): 58–67.

AUTHOR SUSAN HERRINGTON is a Professor in the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of British Columbia. She is the author of On Landscapes, published by Routledge in 2009. Currently, she is writing a book on modern landscape architecture and the work of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander.

Figure 4. Illustration by Richard Deckert shows the Corythosaurus Casuarius, genus of the Duckbill Dinosaur, swimming and the other dinosaurs on land. This drawing was frequently used by paleontologists in their publications (From Barnum Brown, Corythosaurus Casuarius: Skelton, Musculate and Epidermis in Bulletin of The American Museum of Natural History 35. 1916. Plate XXII).

The paper is an account of McHarg's theory that Nature is the world's truth in terms of its evolution and existence, and science is the means to understand it and achieve its objectives through design. The author Prof Susan Herrington works with the faculty of the Landscape Design course in University of British Columbia. This paper of hers is a part of her discussion, explorations and comparisons of the modern and the postmodern theories in Landscape Design.

The paper begins with the talks about the accomplishments and the bases for McHarg's theory. His accomplishments being three: conception of the relationship between nature, science and design, promotion of the map overlay or layered cake method and finally the scientific theories that back planning and designing with nature.

His theories and concepts started taking shape when he was given the task of preparing a new curriculum for the University of Pennsylvania in 1954, wherein he started a course called the Man and Environment in 1959 which consisted of guest lectures by various scientists with a background of forestry and ecology. He

had an idealist theory criticizing humanist ideas as well as religious philosophies while encouraging science as a base for nature's evolution.

He criticized the Western Gardens while appreciating the English Landscapes from the 18th century calling them out to be designed with nature. The author later points that these landscapes were based on the Enclosure Acts and they served only one family for 60 acres of land. Their cropping technique was later on criticized by agriculturists and ecologists as very harmful for the soil.

McHarg’s map overlay method is based on various other models like cartography of contagions in the early 19th century or the maps made by Warren Manning in the US. The author credits the great Landscape Designer to be the first one to have ‘championed’ this style of map making in spite of there being many who had already used the technique.

McHarg’s theory of science supporting Nature is derived from two great authors and scientist, namely, Charles Darwin and Lawrence Henderson. Their theories were merged together to form his theory of adaptation, evolution and stability.