5 minute read

Forgotten Heroes

Forgotten Her es Jewish Doctors in the Civil War

By Avi Heiligman

Advertisement

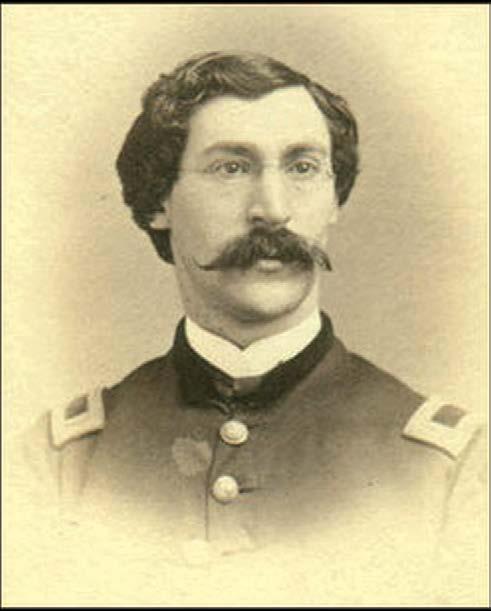

David Camden de Leon, the “fighting doctor” Part of a letter written by Bernhard Behrend to President Abraham Lincoln about allowing Jews in the army to rest on Shabbos Surgeon Dr. Morris Asch is buried in Salem Fields Cemetery in Brooklyn, NY

The American Civil War was by far the bloodiest conflict to take place in North America. While the knowledge of medical practices was primitive, doctors and medical personnel did their best to save as many lives as possible. People like Clara Barton, who volunteered to go to the frontlines and give medical treatment to soldiers still lying on the battlefield, are still remembered today. There were some Jewish doctors and medical personnel who aren’t quite as famous who served on both sides of the conflict.

David Camden de Leon had an interesting background before becoming the surgeon general for the Confederacy. Dr. de Leon, who became known as “the fighting doctor” for his heroics during the Mexican American War, hailed from a Sephardic Jewish family in Charleston, South Carolina. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a medical degree and became an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army in 1838.

The first war that de Leon served in was the Seminole War in Florida where he “served with distinction” (the dispatch makes no reference as the particular action). He was then stationed on the western frontier for several years, and in 1845, he went with General Zachary Taylor down to Mexico. During the Mexican American War, the doctor was present at most of the battles during the drive to Mexico City. On two occasions at the Battle of Chapultepec, he led a charge of cavalry after the commanding officer had been killed or wounded. The doctor was able to lead counter-attacks that effectively stopped the enemy. For his heroics, de Leon was cited by congress for his gallantry in action. After the war, he became a surgeon with the title of major.

As with many officers from Southern states in U.S. Army, he was opposed to secession and was torn when time came to choose a side at the start of the Civil War. Dr. de Leon resigned his commission in early 1861 and was appointed by Confederate President Jefferson Davis to the role of Chief Surgeon of the Army of the Confederate States of America. From March 1861 until August 1862, he held the post as the South’s surgeon general. After the war, he moved to New Mexico and died in 1872.

Surgeon Dr. Morris Asch served with the Army of the Potomac in the Union Army and was present at many important battles during the war. Asch was born in Philadelphia and graduated from Jefferson Medical College in 1855 as a medical doctor. When the fighting began in 1861, Dr. Asch was appointed as an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army. A few months later, he went on active duty and in 1862 was appointed surgeon-in-chief for the artillery reserves in the Army of the Potomac. He later held positions as the medical inspector of the army, medical director for the 24th Army Corps, and after the war became the staff surgeon for General Phillip Sheridan.

During the Civil War, Asch was at important battles including Gettysburg, Chancellorsville, The Wilderness, and Appomattox Court House. Altogether, he tended to wounded soldiers during sixteen battles. Right before the war concluded in 1865, Asch attained the rank of major and continued serving in the army even after the conclusion of hostilities. While on Sheridan’s staff, he came down with yellow fever. Once he recovered, Asch rejoined the army and tended to the wounded during the wars with the Plains Indians.

Dr. Asch retired in 1873 and became a renowned expert in the field of laryngology.

Many in the medical field served with the regular U.S. Army. Hospital steward Adajah Behrend was a Jewish soldier from Germany. He enlisted with the regular army in 1861 and was promoted to hospital steward. He was wounded at James River in 1862. After recovering, Behrend rejoined his unit and continued to serve through the rest of the war.

His father wrote a letter to President Lincoln of which the contents became known after the war. It was in regards to an executive order that religious soldiers can observe Sunday as their Sabbath. Part of the letter reads:

Now by the order of your Excellency you give the privilege to those officers and men in the army who by their religious creed do observe the Sunday as a holy day and a day of rest; but you make no provision for those officers and men in the army who do not want to observe the Sunday as a holy day, as for instance … the Jews, who observe the Saturday as a hold day and a day of rest … I gave my consent to my son, who was yet a minor, that he should enlist in the United States army; I thought it was his duty, and I gave him my advice to fulfill his duty as a good citizen, and he has done so. At the same time, I taught him also to observe the Sabbath on Saturday, when it would not hinder him from fulfilling his duty in the army.”

After the war, Adajah received his M.D. from Georgetown and became a well-known physician.

Many others served in the medical field during the war, including Mark Blumenthal, who served as surgeon major in the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. Those serving in the medical field while in the military are often overlooked. While they usually aren’t the ones who can change the outcome of a battle, they can change lives on the battlefield for the better and are truly Forgotten Heroes.

Avi Heiligman is a weekly contributor to The Jewish Home. He welcomes your comments and suggestions for future columns and can be reached at aviheiligman@gmail.com.