Our Design DNA

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2019 Entropic Encounters

Kostas Grigoriadis, Maren Klasing

2018 Otherworldly: New Colonies of the Anthropocene

Jennifer Chen, Maren Klasing

2017

Process Matters

Kostas Grigoriadis, Sofia Krimizi

2016 Liquid Laboratory

James Hampton, Sofia Krimizi

Entropic Encounters Kostas Grigoriadis, Maren Klasing

Entropic Encounters

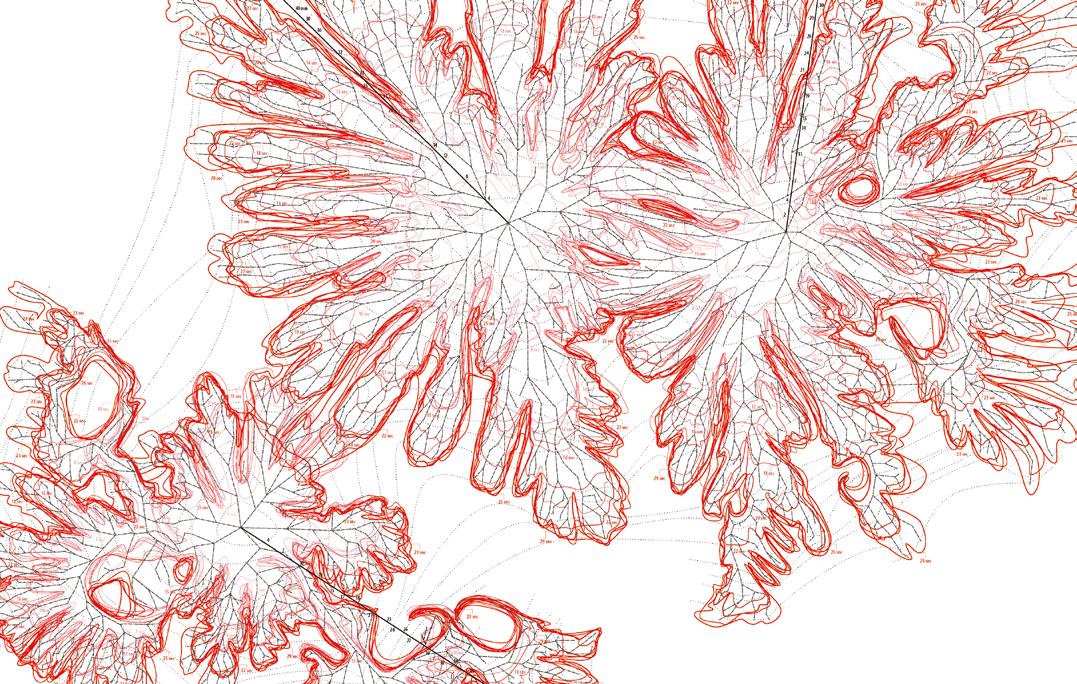

Kostas Grigoriadis, Maren KlasingUG11 operates with the idea of ‘change’ in mind. The aim of the unit is to embrace uncertainty in the digital age and address some of the increasing challenges of the Anthropocene. We argue that processbased, computational design thinking enables us to prepare for the complexity of an unpredictable future. The built environment needs to facilitate adaptation and abandon the unsustainable nature of static architecture and predefined, confined space. Contemporary times require a radically new repertoire and alternative design methodologies to cope with volatility and to deal with ambiguity. In UG11, we strive to create resilient and dynamic environments as a result of iterative processes, in response to major societal and environmental shifts. We aim for unique spatial experiences that achieve versatility through complexity, and discover distinct qualities through diverse unconfined and atmospheric spaces.

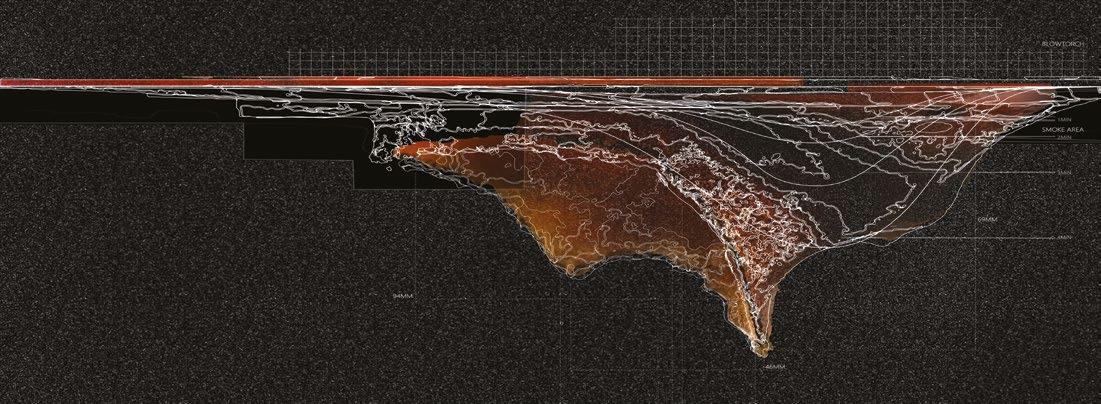

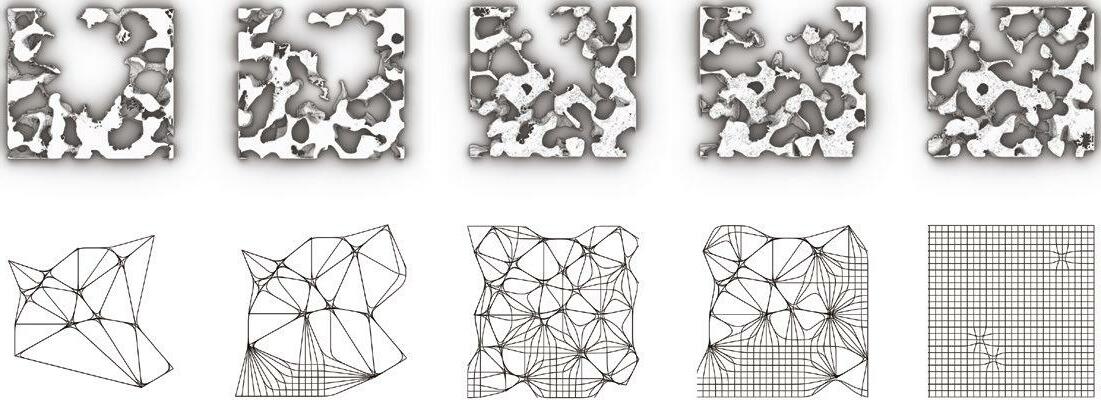

This year started off with physical, material experiments that explored notions of ambiguity, impermanence, emergence and entropy. We simulated natural processes of transformation where multiple forces resulted in surprising synergies and intriguing spatial ambiguities. Inspired and informed by these initial explorations, we identified computational design techniques that aimed to simulate such processes in the digital realm, generating various formations, versatile conditions and atmospheric qualities.

These experiments were then applied in the context of Moscow, where we visited mass-housing schemes with nondescript envelopes, abandoned buildings, obsolete facilities and monuments of past times, to observe and critique the impact and failures of repressive and purpose-built architecture. This dense urban fabric provided us with a fertile ground to formulate our briefs for architectural interventions that addressed environmental and societal issues like overpopulation and obsolescence, unregulated automation and alienation, unleashed consumerism and infrastructural collapse. We discussed how the inherent ambiguities of our process-based formations enabled our architectural concepts to adapt to the changing circumstances of a place, directly informed by the computational techniques we experimented with.

Alternative design methods served as thought vehicles with which to speculate on alternative architectures, investigating synergetic relationships between virtual, natural and artificial materiality with productive encounters of existing and envisioned environments. Architectural ecologies were developed that were relevant and resilient, comprised of diverse spatial qualities, characterised by ambience and immediacy, and ultimately redefined our perception of space and the way we relate to it.

Year 2

Hanna Abramowicz, Ahmed Al-Shamari, Poppy Becke, Angel Lim, Diana Marin, Zaneta Ojczyk, Jingxian (Jacquelyn) Pan, Chueh-Kai (Daniel) Wang, Kehui (Victoria) Wu, Sevgi Yaman

Year 3

Wan Feng, Celina Harto, Francis Magalhaes-Heath

Special thanks to our technical tutor Jeroen Janssen, and many thanks to our computing tutors and guest critics: Monika Bilska, Samuel Esses, Soomeen Hahm, Xuanzhi Huang, Martin Krcha, Igor Pantic

11.1–11.4 Zaneta Ojczyk, Y2 ‘Gallery Of Reclamation’. Moscow‘s landfills are reaching maximum capacity, due to the population only recycling 4% of their waste. This proposal aims to show the aesthetic side of recycling by demonstrating how disposed objects can have a second life. The gallery not only exhibits trash art, but is also an exhibit itself as it uses reclaimed plastic as a building material. The versatility of plastic is harnessed here to create varied internal spatial conditions that are manifested gradually as one walks through the gallery. 11.5–11.7 Angel Lim, Y2 ‘Transit Theatre’. The proposal for a drive-through theatre in the performance arts district of central Moscow provides an entertaining alternative to the frustration of being stuck in the city’s seemingly neverending traffic jams. Three differentlysized stages are set along the road with pedestrian paths weaving above and below. Based on the varying lengths of each show, the road curvatures determine speed and time spent driving by these stages. The roof structure carefully curates light conditions and sightlines, whilst creating a sense of arrival. What was a congested 30-metre-wide motorway that was too difficult to cross is now a bridge over a continuous park, enabling a harmonious relationship between cars and pedestrians. 11.8 Celina Harto, Y3 ‘Grown Ornaments’. This project started with a series of material studies of salt and borax, observing the ornamental qualities and structural capacities that result from their growth over time. Following this, a series of urban interventions were designed across London that consist of bare frameworks to facilitate the growth of crystals that form pockets of space for people seeking refuge from the unpredictable London weather, whilst forming highly sculptural and ornamental aesthetic singularities in the urban fabric. 11.9–11.10 Francis Magalhaes-Heath, Y3 ‘Democratising the Edge’. This project salvages the vast amount of material produced by the demolition of the social housing developments in Moscow, and proposes their deposition on the city’s river embankment. There, they are used to construct a landscape of living spaces that weave into public platforms and the corroded river bed to form a democratic landscape. Learning from the failures of other cities, the proposal aims to democratise the edge and reconcile public space so that it is accessible by all, with private housing that generates profit for the city. The diverse repertoire of spatial conditions and spectrum of building blocks established for the proposed reconstruction is informed by thorough research into deconstruction methods and weathering effects on materials in Russia’s extreme climate.

11.11–11.14 Jingxian (Jacquelyn) Pan, Y2 ‘Youth Shelter’. This project proposes a shelter offering protection for teenagers that have been exposed to domestic violence. A range of spatial conditions are created with variably soft and hard materials to provide a unique sense of safety and relaxation for each occupant, whilst the organisation of the different interiors promotes the development of positive relationships amongst the teenagers.

11.15–11.19 Kehui (Victoria) Wu, Y2 ‘Krushchyovka Disordered’. Responding to Moscow’s demolition of the Khrushchyovkas – mass-housing built during the Soviet era – and arguing for the selective preservation of their architectural and cultural qualities, this project attempts to adaptively reuse two such buildings in Cheremushki by converting and extending them into a themed luxury hotel and Khrushchyovka museum. Observing the modular features of the existing buildings, the design disrupts and deforms the strict spatial grid whilst working with a programmatic transition gradient to bring the old and the new together in a coherent yet distinct proposal.

11.20–11.21 Ahmed Al-Shamari, Y2 ‘Parallel Pools’. In this project, a catalogue of variably porous walls are used to regulate atmosphere, light and ambience in a public bathhouse that acts as a vitrine for its concealed LGBTQ counterpart. The latter provides a network of spaces for bathing and relaxation for this persecuted and censored community in Moscow. Both parts remain contained in parallel realities, but they coexist in an architecture that enables their encounter through varying degrees of phenomenal and actual transparency, challenging that divide.

11.22, 11.25 Hanna Abramowicz, Y2 ‘Synthetic Garden’. This proposal is a response to the fact that we stigmatise technology by denying its natural aspects: mortality, fragility, complex interactivity, and its utter dependence on sometimes fitful flows of energy and material substance. An initial series of both physical and digital studies explore these abstract notions. The proposed landscape elicits a tender, reverential and nurturing attitude towards technology and artificiality.

11.23–11.24 Chueh-Kai (Daniel) Wang, Y2 ‘Communal Culinary Centre’. Inspired by the current Russian culinary revolution, this project creates a social hub for Moscovites, aiming to educate them through a shared dining experience. The building houses the ecology of cooking, from growing to recycling. At the intersection of three distinct volumes, spaces merge and transform towards an inner core of shared areas, where formal qualities shift and material properties adjust to the changing and overlapping spatial requirements.

11.26–11.27 Wan Feng, Y3 ‘Souvenir Tower’. This design proposal aims to promote traditional Russian crafts that have fallen under the radar despite their cultural significance and economic value, providing a livelihood for many. The building programme organises two main elements in a vertically spiralling arrangement that is part monument and part mall, incorporating functional workshop facilities for artisans with a visitor route that allows tourists to view and experience the various manufacturing processes and purchase their products. The tower is supported by an exoskeleton that inherits the ornamental quality of the souvenirs and identifies their structural potential.

Otherworldly: New Colonies of the Anthropocene Jennifer Chen, Maren Klasing

Year 2

Temilayo Ajayi, Alp Amasya, Arsenij Danya Barysnikov, Frances Leung, Su Yen Liew, Jiana Lin, Pinyi (Joicy) Liu, Chuzhengnan (Bill) Xu

Year 3

Paul Brooke, Yuqi (Kenneth) Cai, Hao Du, Camille Dunlop, Chi Ka (Vincent) Lo, Harrison Long, Gabriel Pavlides

Thank you to our Technical Tutor: Jeroen Janssen

Thanks to our Digital Media Tutors: Harry Spraiter, Nathan Su

Thank you to our critics: Isaïe Bloch, Ricardo de Ostos, Andreas Körner, Yael Reisner

Otherworldly: New Colonies of the Anthropocene

Jennifer Chen, Maren KlasingWhat does it mean to live and design in the age of the Anthropocene?

Human activity is now considered the dominant influence on the earth’s climate and geology. In its 4.5 billion years of existence, the world has never experienced such acceleration in its transformation. In UG11 we argue that our current relationship to nature and its resources is no longer a sufficient response to the warming climate and its volatile conditions. They could be re-imagined as a key driver in the way we design communities that are versatile, resilient and resourceful. The built environment must adapt to the continuously changing surroundings. New cultures must emerge from these strange new natures.

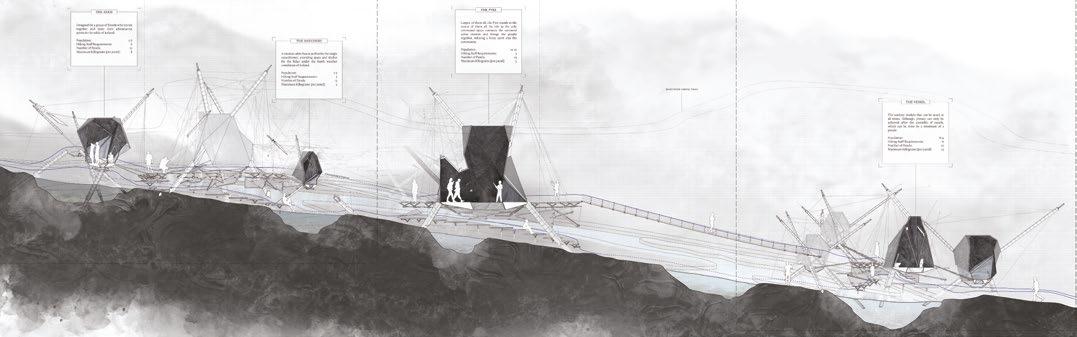

Like pioneers of unchartered territories in the stories told to us, we too donned our helmets and headlamps, snow boots and ice grips, braved the arctic wind and rain to explore the diverse landscapes of Iceland. Our expedition took us to volcanoes and glaciers, from waterfalls to the windswept coasts, ancient formations in the lava fields to shiny new glass buildings in the capital. We traced the power of nature from its rawest state, to the energies harnessed by people in steam-filled power plants. At these sites of extremes, we learnt from the ingenuity of humankind and imagined what new architectures and ecologies could emerge. To do this, we used computational design tools and borrowed techniques from storytellers and filmmakers to help us observe natural phenomena, map current conditions, simulate systems and transformations. Through the process, we began to understand the mechanisms that drive this planet, and to discover new ways to engage with it.

We started by designing artefacts that might have been from the future or an alternate present. The new connections to nature conceived at the scale of our bodies were then extended to the scale of our communities. The result is a range of projects where these new opportunities and approaches to engaging with the environment and natural resources are tested. We speculated on programmes designed for a range of communities, from climate refugees to tourists, scientists to patients; on sites underground to mountaintop, from inland forests to eroded coastlines. Along the way, we forecasted industry and economy, considered our heritage and culture, and speculated on how architecture might grow and adapt. These projects are a survey of our current hopes and anxieties, failings and endeavours. They make up an atlas of possible new ecologies.

Fig. 11.1 Camille Dunlop Y3, ‘Pipeline Hijacking’. A response to the current Icelandic housing crisis using narrative as a driving force to speculate on community formation and its architectural implications. The site of this proposal is very close to the Hellisheidi Geothermal Power plant, and surrounds a pipeline that carries hot water to and from the power plant. A community is envisioned as a closed-loop piping system that feeds from this existing infrastructure. A variety of intricate pipe formations and patterns create specific thermal conditions for the domestic programme. Figs. 11.2 – 11.4 Cha Ka ( Vincent) Lo Y3, ‘The Bivouac’. The problem of overpopulating tourism has led to a burgeoning demand for accommodation and privacy, and obstructs the true beauty and tranquillity of the Icelandic landscape. This project proposes a solution for tourists to

enjoy unpopulated areas of Iceland, with well-designed cabins that function like tents or bivouacs. As opposed to visiting the more popular attractions this programme encourages people to go hiking and camping. The project starts off with a number of critera that are derived from the hazardous yet beautiful nature of Iceland. Spaces are to be constructed with minimal intervention to the natural habitat of the national park, but can be relocated around the park annually to promote different hiking areas and expose Iceland’s hidden beauty. 11.2

and floating concrete provide foundations for different sections of the proposed elements. Permeable concrete has been developed to allow for water to filter through without compromising its structural intergrity. Acknowledging the fact that water can penetrate the mix, mangrove seeds are mixed into the cast and over time grow out of the concrete. This methodology can be adapted for marine environments to enhance biodiversity and support new ecosystems to thrive.

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2018

11.9

Fig.11.11 Hao Du Y3, ‘Ice-Age Community and Gardens’. It is 2060. The world has been cooling down for 20 years. Most of the land is covered by snow and ice. The world average temperature breaks -1 °C and scientists are predicting a new ice age. At the same time, people are in need of affordable, sufficient and renewable energy. A solution is geothermal energy. This project proposes Iceland’s Krysuvik geothermal area as a testing ground to start a community. Inhabitants excavate the ground up to 200 metres deep in order to build underground gardens with different climatic conditions. Using the excavated rocks, they build vernacular architecture using drystone technique to shield themselves from the extreme cold. Fig.1.12 Paul Brooke Y3, ‘Glitched Network’. This building primarily serves as refuge point from the invisible but

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2018

abnormalities of the ancient rock that forms the ridge, while extrapolating these qualities to form zones of safety by way of point clouds that control the extent to which the vulnerable populace are exposed to harmful solar rays, allowing the post-atmospheric community to dwell safely. 11.13

Figs. 11.13 – 11.18 Paul Brooke Y3, ‘Glitched Network’. In 1989, the international community ceremoniously rejected the Montreal Protocol, whose chief aim was to protect and revive our dwindling atmospheric layers, which was our only true barrier from the vacuum of space and the cruelty of solar winds. Life on planet earth has changed forever, and in few places is this more pronounced than in Iceland, that, due to the total absence of the Ozone above, has been rendered defenceless to such devastation. This building primarily serves as refuge point from the invisible but devastating electromagnetic forces that the civilian population are subjected to. As it spans along the Icelandic Reykjanes ridge, the construction embodies a unification of the natural world and mediated design; capitalising on the natural magnetic

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2018

Figs. 11.19 – 11.23 Yuqi (Kenneth) Cai Y3, ‘Limestone Farm and Auction Hall’. It is the year 2118. Overpopulation and overconsumption have taken their tolls on earth. Natural resources that were once widely available are now quickly depleting. The value of natural materials skyrockets as they become scarcer and less economic to mine. Limestone is considered precious. The building, an Auctioneers’ Limestone Farm, is strategically located on the edge of the Blue Lagoon, because it requires a reliable geothermal heat source, large amounts of water and basalt rock grounds, all of which need to be locally available for the farm to function and can be found in abundance at this southwestern tip of the island. The farm utilises cutting-edge carbon capture technology to ‘grow’ limestone from CO 2 and basalt, which will then be ‘harvested’

and sold in the auction hall. Due to unpredictable market prices and economy, the quarry would develop and expand irreguarly over time. It reads like an agile crack in the basalt field that constantly changes its direction and appearance in response to a dynamic market and its cost efficiency demands. An initially pragmatic decision and strategy to maximise basalt surface areas in order to grow more limestone resulted in surprisingly ornamental surface qualities and unique spatial experiences. The result is an impressive architecture that is in harmony with and subtracted from the basaltic lava field surrounding it.

Process Matters

Kostas Grigoriadis, Sofia Krimizi

Year 2

Teresa Carmelita, Du Hao, Michelle Hoe, Jie Kuek, Jiyoon Lee, Zhi Tam, Jun Yap, Renzhi Zeng

Year 3

Kelly Au, Samuel Grice, Ana-Maria Ilusca, Olga Karchevska

Thank you to:

Sean-Paul von Ancken, Biayna Bogosian, Ivi Diamandopoulou, Natalia Hayes, Michael Herrmann, Alvin Huang, Francesca Hughes, Rick Joy Architects, Claudia Kappl, Hanne Sue Kirsch, Costandis Kizis, Colby Ritter, Sylvie Taher, Roger Tomalty

Process Matters

Kostas Grigoriadis, Sofia KrimiziIn the beginning of the 20th century, the art historian Alois Riegl wrote of a decisive change that took place at the time – namely the transition from the valuation of old materials to the valuation of new ones. This reflected the shift in early modern Europe towards a preoccupation with newness, which eventually paved the way for the constant invention of new materials that could be easily manufactured via mechanised mass production, as opposed to artisanal making. This shift effectively also triggered the modernist collapse of the links between design, form and materiality.

More than a century later, the material invention paradigm that Riegl once witnessed is now happening at an exponentially fast rate, with new materials and production methods being concocted each and every day. In architecture, on the other hand, the age-old separation of the types of construction in tectonics and stereotomics are – surprisingly – still valid, illustrating quite clearly the fact that architecture, and the way it is designed and built, has yet to catch up with the exponentially advancing material innovations of today.

In this context, the objective of the studio is to align with these developments, and to attempt to generate a new architecture in sync with contemporaneous material advances. Rethinking the ways in which space is conceived and designed, buildings are constructed, and architecture is inhabited generates for us an unprecedented opportunity for spatial and architectural innovation, informed by twenty-first century materials and materialisms.

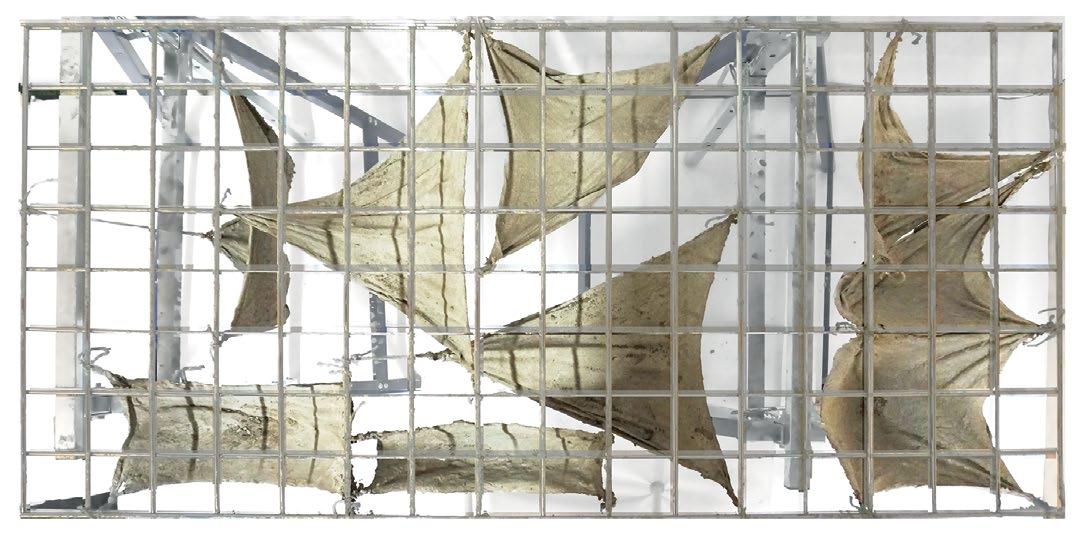

In pursuit of this, we initially looked into materiality in its malleable, liquid state. We explored different ways in which liquid materials can be physically admixed and cast, and their rheological properties – with flow and coagulation simulated digitally. In parallel with this, we pursued unconventional fabrication techniques that explored the reciprocal relationship between mould and cast, pushing the solidified materials to breaking point, and understanding both the inherent and unexpected properties of our admixtures.

We then travelled to Los Angeles and Phoenix. In this land of extreme juxtapositions and odd notions of architectural normality, the truth in materials was whatever we decided it to be. Our search explored the banal, weird and wonderful ways that cast materials can be produced. The metropolitan architecture of LA was effectively juxtaposed with the utopic character of Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti and his concept of ‘Arcology’. Our aim was to formulate a firm architectural position through recursive readings of the habitat and instil some of these observations into the urban context of LA, where our buildings were situated. In this process of architectural transplantation, we aspired to rebuild the modernist collapse of the relationship between form, design, materiality and process in order to generate a new type of architecture, or a 21st-century Arcology that has finally caught up with the future.

Fig. 11.1 Michelle Hoe Y2, ‘After the Earthquake’. Gradient concrete-spraying study model of the inhabitable scaffolding module. Figs. 11.2 – 11.4 Renzhi Zeng Y2, ‘Homeless City’. A 3D-printed framework designed through liquid material simulations is openly inhabited by homeless people currently occupying large parts of Skid Row in Los Angeles. The main spaces consist of a central communal area that is designed to provide basic sanitary facilities and specialised areas that enhance the interactions of the occupants. In addition, the open-cellular organisation of the living units aims to strengthen the micro-social relationship of homeless people. Fig. 11.5 Jiyoon Lee Y2, ‘Truck Hotel and People’s Highway’. Forming an oasis in the endless desert of the interstate highways complex, the project consists of an automated

parking system and living and communal spaces for large vehicle drivers, who are otherwise not allowed to exit the highways. The individual habitation modules can be customised in number and size in order to fit into various freeway intersections in key locations across the main east-to-west truck routes. 11.2 11.3 11.4

Figs. 11.6 – 11.7 Teresa Carmelita Y2, ‘Foam Aggregations’. A series of study models exploring the relationship between top-down control imposed by the model maker and the material’s intrinsic bottom-up behaviour. Here, the s-shaped foam blueprint ends up in a fractal-like series of folds that are generated as a result of this negotiation between design and materiality. Figs. 11.8 – 11.9 Michelle Hoe Y2, ‘After the Earthquake’. Anticipating the next big earthquake to strike Los Angeles, the proposal consists of a series of inhabitable scaffolding modules that act as bracing systems when placed in between earthquake-affected historical buildings. Dwellings, utility and social spaces within the scaffolding allow users of the adjacent buildings to go about their daily activities – and for habitation to carry on – despite the disaster.

Figs. 11.10 – 11.11 Du Hao Y2, ‘LA Actors’ Homestage’. The project is a hybrid of living spaces and stages for struggling actors in Los Angeles, located on top of the disused Regent Theatre in downtown LA. A series of catenary arches, made up of steel tubes sprayed with concrete, forms an easily deployable building system that organises the plan and structures the distribution of acting and living spaces below. Figs. 11.12 – 11.13 Ana-Maria Ilusca Y3, ‘The Museum of Light’. The project looks at the evolution of light and colour in the cinematic industry and proposes a series of spaces that capture the stylistic, visual and spatial qualities of film noir. Here, a series of Hele-Shaw cell experiments are tested out as a technique for recreating the stark contrasts between light and shadow found in this particular genre. 11.10

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2017

Figs. 11.14 – 11.15 Zhi Tam Y2, ‘LA 2024’. One of the decommissioned Astronaut Islands off the Long Beach coast in LA is redesigned to accommodate diving and swimming events during the 2024 Olympics. The scheme is designed around a series of elevated vistas that frame strategic views of the city, generating a multi-layered and multiple set of pictures, experienced via television as well as other media interfaces. Figs. 11.16 – 11.17 Kelly Au Y3, ‘Lungs of LA’. Inspired by Biosphere 2 in Arizona, the project consists of a prototypical learning environment designed to filter and clean the polluted LA air, as a response to the increasing number of children with respiratory problems in the city. Providing these controlled-air environments are a series of tensegrity structures made of a latex skin held in tension by

wooden members, with all the materials that make up the proposal locally sourced from native Californian rubber trees. 11.16 11.14

Fig. 11.18 Jie Kuek Y2, ‘Depolluted Learning - Filtering Wall Study’. The Maywood area in south Los Angeles is suffering from air pollution, a long-existing problem in the city, as well as from soil contamination caused by the discharge of exide lead during the processing of industrial waste. The project attempts to address these issues through a series of tectonic elements that filter the air and clean up the soil, minimising site pollution and providing a clean environment in which local children play and learn. Figs. 11.19 – 11.20 Jun Yap Y2, ‘Mould and Moulded’. This process consists of the recording of traces generated and left over by a solvent acting on dissolvable substances and the casting of concrete within these partially dissolved moulds. The aim is to effectively obtain a moulded structure, observe the negative spaces formed by the solvent and translate these

11.20

into spatial elements. Fig. 11.21 Jiyoon Lee Y2, ‘Angle of Repose’. The project explores the self-forming behaviour of sand under the mere influence of gravity. 11.18 11.19 11.21

Liquid Laboratory James Hampton, Sofia Krimizi

Year 2

Nour Al Ahmad, Alexandra Cambell, Rupinder Gidar, Nnenna Itanyi, Ziyu (Ivy) Jiang, Harry Johnson, Tung Yi Sardonna Leung, Fola-Sade (Victoria) Oshinusi, Zhi (Zoe) Tam, Ching (Cherie) Wong, Yu (Amy) Wu, Ke Yang

Year 3

Yat (Heidi) Au-Yeung, Ana-Maria Ilusca, Justin Li

We would like to thank our consultants and critics: Chris Carroll and ARUP, Costandis Kizis, Johanna Muszbek, Hseng Tai Ja Reng Lintner, Brendon Carlin, Francesca Hughes, Frederik Petersen, Sara Shafiei, Bob Sheil, Mollie Claypool, Elisabeth Dow, Yota Adilenidou, Delfina Fantini van Ditmar, Stefanos Levidis, Diony Kypraiou, Daniel Rea, Nick Browne, Jessica In, Manolis Stavrakakis, Ifigenia Liangi, Cristiana Chiorino, the Pier Luigi Nervi Project Association and from ETH Zurich: Achilleas Xydis, Sarah Nichols, Guillaume Habert, Nils Havelka

Thank you to our sponsors ARUP

Liquid Laboratory

James Hampton, Sofia KrimiziUG11 operates as a material research laboratory, pursuing strategies of making to design new spatial typologies. Through investigation of cast material processes we look for the strange, the banal and the beautiful. We cast concrete. Our process is driven by experimentation on alternative uses of material and our investigation is informed by data collection, measuring and analysis. The material experiments lead us in a constant feedback loop of design stages, physical models, digital aspirations and fabrication techniques.

We engage with a process that welcomes material mis-use and misbehavior, aspiring to systematise knowledge garnered from failure. We examine the ways technology can push our material beyond established forms and types. By investigating recent concrete fabrication and structural methods, we discover unexpected and productive design processes, potentially defining a new craft; one that can be both morphogenic and typological and will respond to a variety of programmes. Concrete, the protagonist of cast building materials, becomes in the unit the vehicle to disrupt and redefine practices of architectural synthesis. The diversity of scales, design approaches and structural systems applied to our projects has a direct correlation with the protocols of fabrication developed in the beginning of our investigation into the world of cast materials.

Our field trip adopted the format of a Grand Tour focused on concrete applications, building paradigms and prototypes as well as current material and theoretical research in the field. Starting in Rome, we visited some of the first applications of concrete in the history of architecture and engineering, as well as identifying the sites of operation for UG11 projects in the north part of the city in close proximity with the large-scale Olympic infrastructure, as well as the recent MAXXI Museum. Making our way north to Turin, we visited a series of Pier Luigi Nervi’s buildings, the FIAT Factory in Lingotto and the wild rehabilitation of the National Cinema Museum. Our itinerary took us to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ) in order to explore contemporary research on concrete alternatives, dynamic formwork and automated casting. The last stretch of our trip to Switzerland took us to the Rolex Centre by SANAA in Lausanne before spending the night in the monastery of La Tourette, visiting Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp and ending in Basel with the Vitra Museum and the Goetheanum, Rudolf Steiner’s own design for his school.

Fig. 11.1 Group project ‘Unit Work Assembly'. Experimentations with unorthodox and misbehaving cast processes aspiring to create new structural and spatial typologies. Fig. 11.2 Nour Al Ahmad Y2, ‘Human Concrete’. An investigation into the behaviour of human hair-reinforced concrete. Detail of physical model testing density and distribution of hair particles in the concrete mix. Fig. 11.3 Tung Yi Sardonna Leung Y2, ‘Internally inflatable concrete’. A series of physical experiments testing the relationship between gravity and viscosity on pre-pressurised inflatable moulds. Fig. 11.4 Ching (Cherie) Wang Y2, ‘Inflatable Lattice’. Hybrid casting device controlling a synchronous flow of air and concrete allowing for multiple chambers of internal complexity to emerge simultaneously. Fig. 11.5 Ke Yang Y2, ‘Fabric-Formed Concrete Creatures’.

An exhaustive investigation in the creation of fabric-formed concrete elements that grow in formal complexity and structural performance. Alexandra Campbell Y2, ‘Air-Formed Concrete’. An experimentation in dynamic casting through the use of pressurised air flow applied against the direction of casting. Zhi (Zoe) Tam Y2, ‘Antigravity Casting’. An attempt towards multidirectional concrete casting using a gimbalenabled device. Nnenna Itanyi Y2, ‘Stalactite Casting’. The development of a moldless casting method that used the process of dripping to create an inventive structural system.

Fig. 11.6 Harry Johnson Y2, ‘Concrete-Reinforced Fabric Columns’. An investigation into double reinforcement between fabric and concrete, aspiring to create a system of light vertical elements cast in situ. These photos depict this in full-scale, assisted by Nnenna Itanyi. Fig. 11.7 Fola-Sade (Victoria) Oshinusi Y2, ‘Photographic Concrete’. An interchange between the protocols of analogue photography development and that of concrete casting. The project developed a methodology for impregnating knitted surfaces with concrete mixes allowing aggregates to define a variety of surface textures. Fig. 11.8 Rupinder Gidar Y2, ‘Centrifugal Casting’. An investigation into dynamic casting. The project developed a series of casts set in motion under centrifugal forces acting on the concrete mix. Moments of extreme

11.6

thinness as well as emergent geometries were by-products of the process that informed the work throughout the development. Fig. 11.9 Yu (Amy) Wu Y2, ‘Gravity-Formed Concrete’. An investigation into using thin concrete shells cast in situ, using fabric as reinforcement. The project developed a combinational method of nesting domes, which allows for a systemic understanding of load bearing. 11.7

Figs. 11.10 – 11.11 Harry Johnson Y2, ‘Forest as Market’. The project develops a typology for an open air informal market in the sports district of Flamino in Rome through the definition of a breathing concrete epidermis. The system of columns and canopy allows topical control of light and temperature, simulating the spatial conditions identified in a forest field. A reversed ceiling plan describing the variations of ash density in the concrete mixture is applied onto the tensile fabric through the main market space. The project imagines a growth of this urban typology that can occupy different parts of the city at different moments, following particular events and activity. Figs. 11.12 – 11.14 Justin Li Y3, ‘Slip Film Museum’. The project investigates a system of dynamic concrete slip-printing using the concrete reinforcement bars as paths

for printing devices that deposit a constant amount of cast material though their movement. References from a Gothic structural and ornamental repertoire were relevant in the organisation of a continuous interior for the proposal of the museum of cinematic props in Rome. The building developed between two existing storage warehouses that eventually performed as the museum’s archival spaces. The notion of ‘scalelessness’ in the structure is important, since the system has to accommodate props of an extreme size and material diversity. The typology of the museum suggests a nonprescriptive engagement of the visitor with the building, allowing different paths to form amongst the forest of printed columns. Different types of roof tiles control the light conditions below as the museum collection finds itself in flux.

Figs. 11.15 – 11.16 Rupinder Gidar Y2, ‘Centrifugal Healing’. This project continues the investigation of spun concrete. Inhabitable in-situ spun elements aggregate to create an athletic healing hub within the Olympic complex in Rome. The curing time of the centrifugal casts is analogous to the time spent by the patients in each chamber. The interior surfaces provide a register for the motion of the concrete while liquid. A system of joining between casts is developed in the process, allowing for openings and connections to emerge. Typologies of extreme nesting emerge as the pain and pleasure aspects of the programme are placed throughout the field of chambers. The strategy for construction and assembly is differentiated from the analysis of space as inhabited by the healing body. 11.13 11.14

11.15 11.16

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2016

Figs. 11.17 – Fig. 11.18 Ziyu (Ivy) Jiang Y2, ‘Vertical Roman Beach’. The project imagines a vertical urban beach in the district of Flaminio in Rome. The casting method developed by the project directs the vectors of liquid concrete through a series of horizontal elastic filters, while allowing all vertical elements to be formed mouldlessly. Diving platforms and water pools are formed in vertical juxtaposition with each other, allowing the beach program to develop upwards. The totality of the site is considered to be liquid while in the making, creating in this way different depths of swimming and diving water. The thickness of the concrete is inhabited by the secondary programs that expand from the structural core downwards below the level of the water. 11.17

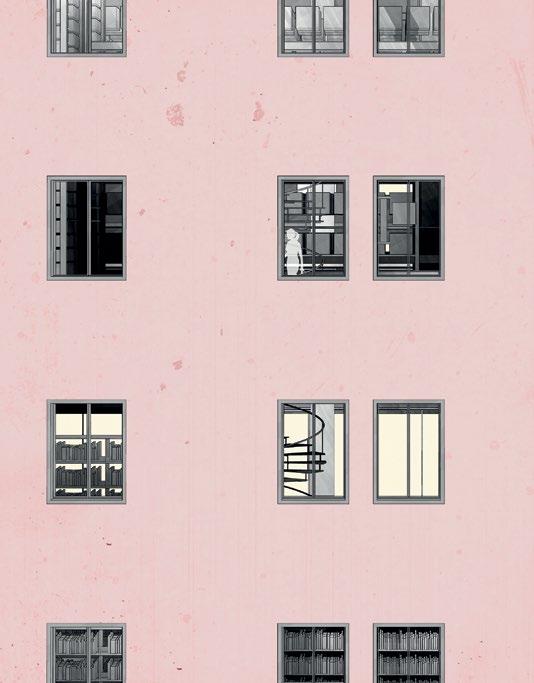

Figs. 11.19 – Fig. 11.21 Yat (Heidi) Au-Yeung Y3, ‘Archive Whispers’. The project investigates the typology of the working archival library focusing on the juxtaposition between the storage of physical manuscripts, digital databases and performance – reading spaces focusing on the genealogy of Roman plays derived from the work of Plautus. A dense and floorless archive hides behind the existing façade of a residential block in the north part of Rome. Through the mass of physical and digital storage, suspended concrete amphitheatres carve through the stacks and operate as hybrids between reading rooms and reenactment spaces for the archived plays. With time, the theatre plots translated into different languages, as Latin morphed into the various Romance languages. With each translation, parts of the plots

were lost and rewritten, creating the diversity of theatrical literature and media today. This archive will collect these materials – ranging from the original manuscripts to the digital versions, from the Latin plays to their translations in Romance languages – allowing the history of theatrical literature to be traced. Each level of storage is dedicated to a time period, organised chronologically so that the building is a physical timeline of the development of dramatic text. The collection will continue to grow, and new forms of recording literature will develop in the future. The archive will also continue to excavate downwards, exposing the Roman grounds and writing its history anew.