Design Anthology PG11

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Super Wicked

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2023 Future Fictions

Laura Allen, Tom Budd, Mark Smout

2022 The Progress Paradox

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2021 Uncommon Ground

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2020 Incomplete

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2019 Terra Incognita

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2018 National Reserve

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2017 Back to the Future

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2016 Incubator

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2015 Home Ground

Laura Allen, Kyle Buchanan, Mark Smout

2014 Ground Control

Laura Allen, Kyle Buchanan, Mark Smout

2013 Proving Ground

Laura Allen, Kyle Buchanan, Mark Smout

2012 Super-Urban-Mega-Listic

Laura Allen, Kyle Buchanan, Mark Smout

2011 Arcadia vs. Utopia

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2010 Neo-Nature

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2009 Field Operations

Laura Allen, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Mark Smout

2008 Second Nature

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2007 Surface Tension

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

2005 Architecture and Emotional Aspiration

Malca Mizrahi, Yael Reisner

2004 Brazilian Tropicalia

Malca Mizrahi, Yael Reisner

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

PG11 explores the philosophical and practical overlaps between land use and its associated architectures, technologies, infrastructures and ecologies in both spatial and conceptual dimensions.

These relationships are exemplified by the term ‘Wicked Problems’. These are issues that lack clarity in both their aims and solutions, and which are inherently complex, multifaceted and entangled. The ‘Super-Wicked’ dilemmas of climate change consist of problems nested within problems, as well as interactions between natural, designed and social systems. Acting on the consequences of climate change, characterised by high stakes, limited timeframes and moving targets, means continually adapting to their changing nature.

Architecture is intricately linked to both the causes and potential remedies of climate change through the flow of materials and energy. This relationship results in some startling statistics – e.g. buildings consume 36% of the world’s energy and cement production alone causes 8% of global emissions. While the design of buildings and city planning needs to be reimagined, the more revolutionary task is rethinking what and why we build.

To examine the complex relationships between human life and natural environments, we based our studies on the Thames Gateway. Despite the regeneration ambitions of successive governments, this area has not achieved its potential. Students were challenged to propose new urban and landscape environments that are a dynamic outcome of the interplay of cultural systems and this complex territory, which is further complicated by environmental change and an uncertain future. We asked: ‘How can the estuarian exurbs connect the past and present with the most pressing issues of tomorrow?’ and ‘How can the interaction of social, ecological and commercial needs respond to those of the environment?’

We then travelled to Barcelona where the impacts of climate stress are obvious. Practice visits to Flores i Prats and their Sala Beckett restoration project, as well as Ricardo Bofill’s office, inspired students to make design choices that extend beyond ‘drawing board radicalism’. They were motivated to contextualise their work within a global setting of super-wicked circularities, uncertainties and conflicts which are never completely solved, but “at best they are only re-solved – over and over again.” 1

Year 4

Xintong Chen, William Hodges, Jane Li, Sarah Nolan, Freya Parkinson, Wing Tin (Cyrus) Shek, Ian Wille

Year 5

Henry Aldridge, Bianca Blanari, Rio Burrage, Jaiwei Fan, Jennifer Oguguo, Madeleine Rutherford-Browne, Sharon Tam, Ziyue Lorena Yan, Jacqueline Zhi Qian Yu

Technical tutors and consultants: Jennifer Dyne (David Kohn Architects), Stephen Foster (Foster Structures), Martha Voulakidou (Buro Happold)

Thesis supervisors: Paul Dobraszczyk, Daisy Froud, Stephen Gage, Jan Kattein, Anna Mavrogianni, Guang Yu Ren, Robin Wilson, Oliver Wilton

Critics: Tom Budd, Kostas Grigoriadis, Luke Pearson, Naomi Rubbra, Marc Williams, Max Willing

1. Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber, ‘Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning’, Policy Sciences, 4 (1973), 155–169.

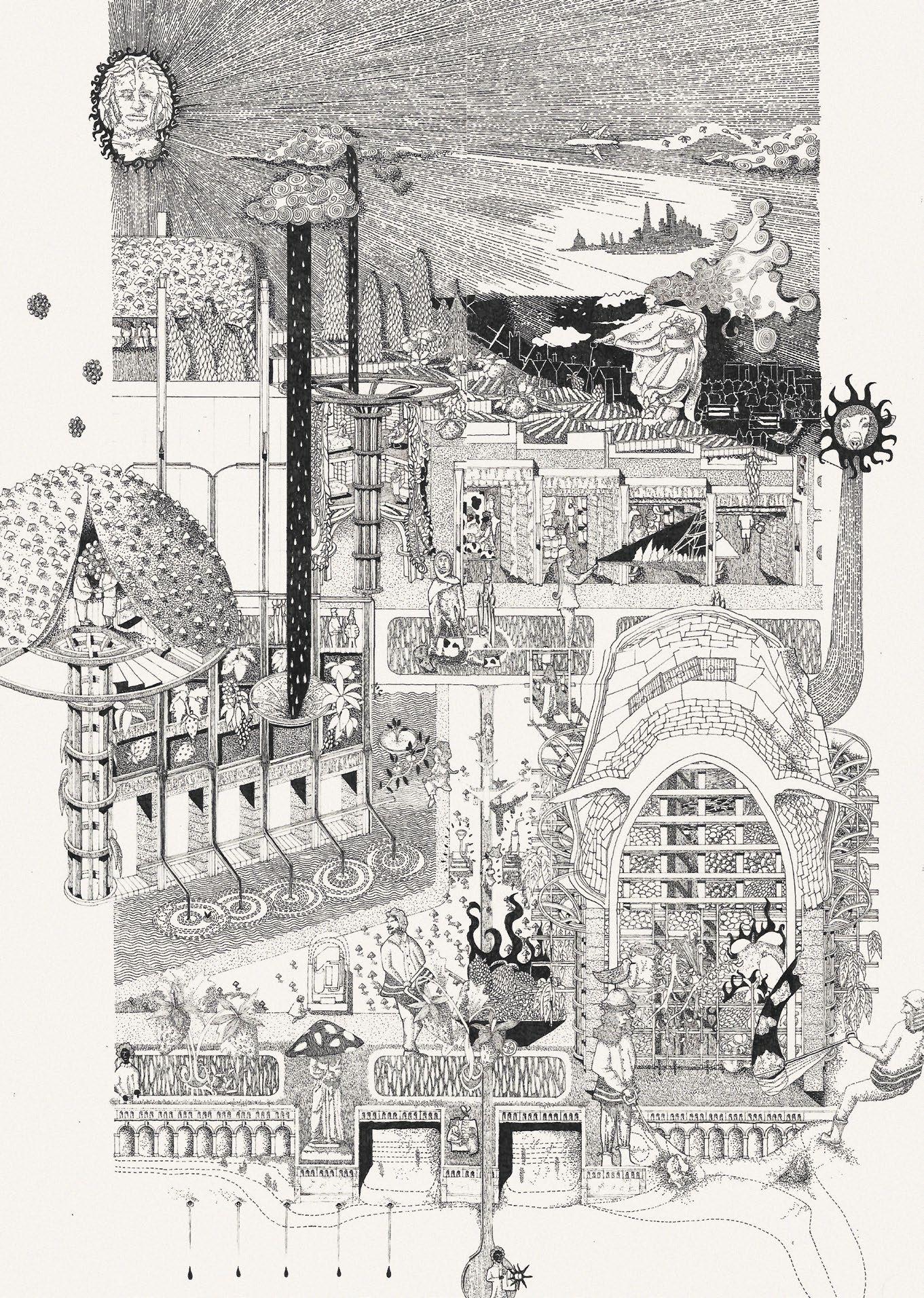

11.1 Henry Aldridge, Y5 ‘The Chalk Institute: Growing a Stone Architecture’. Chalk extraction for concrete production has resulted in chalk pits with unrealised ecological potential. This project uses waste concrete to precipitate stone – much like stalactites – to produce an architecture of growth in quarries, both in stone and flora. The proposed Institute, which researches chalk ecologies and slowly grows in size, is made of chalk and concrete runoff, and becomes a history of the site, reflecting both its history in extraction and its future growth.

11.2 Rio Burrage, Y5 ‘Flooding and Dwelling’. Following a century of neglect of UK flood-mitigation infrastructure, large areas of settlements in the Thames Estuary are submerged due to rising sea levels and extreme weather. A reinterpreted Tilbury emerges within the tidal marshland, typically hostile to human occupation. By re-evaluating British cultures of building and dwelling, the ‘wicked problem’ of urban flooding becomes an opportunity for reconciliation between the urban and the natural.

11.3 Bianca Blanari, Y5 ‘The Greenhouse Archipelago’. Exploring the horticulture of greenhouses, the project critically assesses both the Dutch model and Almeria in Spain. Using greenhouses as the urban fabric, the design confronts monocultural landscapes, addressing pivotal social and environmental concerns. It delves into issues of food security, resource management, cultivation practices and cultural identity, while also scrutinising the conditions of greenhouse workers and users.

11.4 Sharon Tam, Y5 ‘Neutral Waters’. In an era marked by geopolitical tensions, ‘neutrality’ represents a peaceful and pragmatic approach to navigating the complexities of global discord. Neutral Waters transforms Foulness Island into a neutral venue for international conferences that crave a landscape for the pursuit of common ground. The design serves as a canvas for the synthesis of opposites, inviting delegates to walk its paths, where each step embodies negotiation and moderation.

11.5 Jennifer Oguguo, Y5 ‘Fort Bec: Cultural Backdrops for Hybrid Publics’. This project stages a creative park in Becontree, wearing the guise of an industrial estate. A ‘cultural wall’ transforms Parsloe Park into manifestations of cultural stewardship, envisioning painting halls with picnic spots and local storage with prop archives. If home is one’s castle, Fort Bec is a public fortress, carving public territory into the changing landscapes of the Thames Gateway.

11.6 Wing Tin (Cyrus) Shek, Y4 ‘Bake and Blossom in Swanscombe Quarry’. This project transforms an abandoned chalk quarry into a self-sustaining ecosystem, rebuilding connectivity to the town and integrating an orchard, a compost facility and a flour mill with a bakery school. Emphasising sustainability, community involvement and ecological restoration, the project creates a dynamic model of environmental innovation.

11.7 Ian Wille, Y4 ‘Ceded Eden’. The project imagines a future of political turbulence, climate change and coastal towns out of luck. The Sheerness Urban Marsh Council, established in the year 2061, selectively recycles houses and uses their materials to create the council building, factory and a materials store. These facilities manufacture and deploy infrastructure to produce urban marshes. Decorative columns embellish the building and embody the area’s collective memory.

11.8 Freya Parkinson, Y4 ‘False Dawns’. The Thames Gateway, plagued by half-baked promises, consists of a series of isolated developments along the Estuary. It offers no long-term solution for locals or the estuary. Theme park proposals at Swanscombe are endemic of the ‘super-wicked problem’ of profit and policy over quality of life. This project deters short-term gainers from inhabiting land for ‘new beginnings’ by creating spaces for people and wildlife.

11.9–11.10 Ziyue Lorena Yan, Y5 ‘Managed Retreat: Innovating Sustainable Polder Communities on Swanscombe Peninsula’. This project establishes a test bed and natural reserve on the isolated and windswept Swanscombe Peninsula to experiment with landscape creation and community design. Challenging traditional land-sacrifice histories, this regeneration initiative redefines flood risk management. Resilient polders are created that utilise the incoming floodscapes to accommodate scientific communities.

11.11 Jaiwei Fan, Y5 ‘Artificial Washland’. This project proposes a flood-management landscape that embodies an alternative approach to addressing coastal erosion. A layered model integrates various scales and inspires a playful and participatory design process where a dialogue can unfold between biodiversity hotspots, flood infrastructures and a network of public buildings.

11.12 Jane Li, Y4 ‘The Wasteland Reclamation Facility’. Perched atop the toxic spoil heap of Beckton Alps, the facility explores the integration of ecological rehabilitation and educational functions via the process of myco-remediation. Utilising locally sourced materials, including remnants of former ski infrastructure, the project highlights the transformative potential of brownfield sites and a future where industrial relics become foundational elements for resilient landscapes.

11.13 Jacqueline Zhi Qian Yu, Y5 ‘The Flooding School for Amphibious Living’. Harnessing the precarious liminality of flood-prone quarry sites along the Essex Colne Estuary, a matrix of floating and anchored structures, including habitable vessels, gardens, reservoirs and environmental systems, serve as sponges and playscapes. This architectural landscape experiments with adaptability to enable living with water as a response to an increasingly changeable environment.

11.14 Xintong Chen, Y4 ‘Breached! A Meanwhile Marsh School’. This project provides an immediate solution to the lack of social infrastructure. It reconnects Beam Park in Dagenham back to its peatland origins through interventions that gradually decay and breach the surrounding landscape. The building remains atop a reclaimed permanent marsh landscape that accepts and adapts to an inevitable future of flooding.

11.15 Sarah Nolan, Y4 ‘Letting the Landscape In’. This flood refuge proposal speculates on the use of land and its inundation by future flood events. It rethinks the protection of the vulnerable landscapes of Benfleet and Southend Marshes, as well as their inhabitants during weather emergencies. Paper models are used to explore the process by which building edges can be dissolved into the landscape.

11.16 William Hodges , Y4 ‘In Search of Sand and Slowness’. The project synthesises anthropic activity with natural ecological cycles, utilising solar systems as a method to radically decarbonise intense industrial processes. It transforms an existing sand and aggregate depot into a ritualistic landscape focused on material exploration and production. This newfound regenerative industry seeks to augment the fourth industrial revolution.

11.17 Madeleine Rutherford-Browne, Y5 ‘A Toolkit for Retrofit’. As the largest housing estate in Europe celebrates its centenary, how will the Mayor of London’s so-called ‘retrofit revolution’ impact Becontree’s quirky character? This drawing represents a manifesto through a patchwork of interventions, advocating for mass retrofitting techniques and a sustainable way of living. The estate’s architectural homogeneity makes it the perfect testbed for pushing the limits of what retrofit can achieve.

Laura Allen, Tom Budd, Mark Smout

How can architecture strengthen the bond between people and place, and the placelessness of homogenised cities? Australian environmental thinker Glenn Albrecht, seeing the links between human and ecosystem health, coined the term ‘solastalgia’ to articulate the emotional and behavioural consequences of climate change. ‘Eco-anxiety’ of this kind is an emerging phenomenon, triggered by both small-scale and global environmental challenges. This year PG11 focused on environment and future-thinking, imagined a new vocabulary for Generation Anthropocene and asked how architecture can respond to the emotional and environmental effects of the climate crisis.

Situating ourselves within a global context, this line of questioning has been interrogated through projects sited across the globe. Cities and their architecture are never finished and are by their nature experimental. With this in mind, we initially drew inspiration from Boston, USA, focusing on four stories in which interrelating narratives and histories gave both a provocation and a site for investigation. By exposing the complexity of human/ environmental relationships, the tales provide a physical, cultural and political context for the unit’s work. In response to readings of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, published in 1887, utopian thinking is understood as an extrapolation of the present, emerging out of a longing for change. What models for future life can be imagined in the 21st century?

In addition, the unit was also inspired by the radical transformations of Boston’s physical geography to enable the city’s rapid economic expansion. The draining of marshland and flattening of hills allowed the creation of territories for institutional, domestic and ecclesiastical development, alongside the Emerald Necklace of public parks, which emerged as the public realms of Bellamy’s vision. We then asked how future transformations in society and the natural environment might be reflected in the built environment.

These research strands have been adapted and challenged across the unit, resulting in a wide variety of proposals connecting people, place and the environment.

Year 4

Henry Aldridge, Jiawei Fan, Jennifer Oguguo, Zhi Qian Jacqueline Yu

Year 5

Harry Andrews, Emily Child, Ernest Chin, Chia-Yi Chou, Yu Ling (Pearl) Chow, Christopher Collyer, Ka Chun Ng, Charles Pye, Long Hin (Ron) Tse, Maya Whitfield, Chuzhengnan (Bill) Xu

Technical tutors and consultants: Rhys Cannon (Gruff Architects), Stephen Foster (Foster Structures Limited), Martha Voulakidou (Buro Happold)

Thesis supervisors: Carolina Bartram, Brent Carnell, Gillian Darley, Paul Dobraszczky, Murray Frazer, Daisy Froud, Stephen Gage, Polly Gould, Michael Stacey, Tim Waterman, Robin Wilson

Critics: Doug John Miller, Danielle Purkiss, Ellie Sampson, Tim Waterman, Sandra Youkhana

11.1 Long Hin (Ron) Tse, Y5 ‘Isle of Bamboo’. The project proposes a floating island that speculates an alternative approach to land reclamation in Hong Kong. By combining research on Very Large Floating Structure (VLFS) technology and the city’s folk traditions, the project explores a sustainable means of gaining ground that questions the role of land creation in the preservation of ecology, cultural identity and local heritage.

11.2 Christopher Collyer, Y5 ‘Ne(i)ther Regions: Boston Marsh’. Ne(i)ther Regions embrace softness. They dismantle rigid dualistic thinking and foreground performative and generative cyclical processes, generating new modes of ambiguous living. At Long Island, the cathartic processes of steaming, mud bathing and plunging engage with the soft material processes of the newly dredged Boston Marsh, thus renewing crucial solidarity between a local community and its swampy past.

11.3 Charles Pye, Y5 ‘Unclaiming the Land’. Utilising traditional drainage and land-forming techniques the project uses the flooding of the Ouse Washes to construct new higher ground to realign local communities and rethink the use of land within the fens. With the threat of rising sea levels and the inevitable un-claiming of land, the project realigns agricultural land use with conservation and recreational uses.

11.4 Henry Aldridge, Y4 ‘The Boston Snow Council’. With climate change, snowfall in Boston, MA is changing. The project places Boston politicians, to some extent responsible for changes to the local environment, inside a snow structure susceptible to the climate. The structure uses existing snow management techniques, with snow piled into a large mound before excavating an inhabitable space within. The structure only lasts half the year before melting, rebuilding and reconfiguration take place to suit different programmes.

11.5 Yu Ling (Pearl) Chow, Y5 ‘Re-shaping Boston: A Vision for Equitable Communities’. The project enhances the quality of life in Boston’s marginalised Roxbury neighbourhood by aligning it with the living standards of more prosperous areas such as Back Bay. Through architectural modifications and the centralisation of communal spaces within a community hub, an inclusive neighbourhood is created that bridges wealth gaps and preserves cultural and architectural heritage. This image captures a panoramic view of a model that depicts co-living experiences between citizens from opposite ends of the wealth spectrum; it portrays eight scenes of a hypothetical residence.

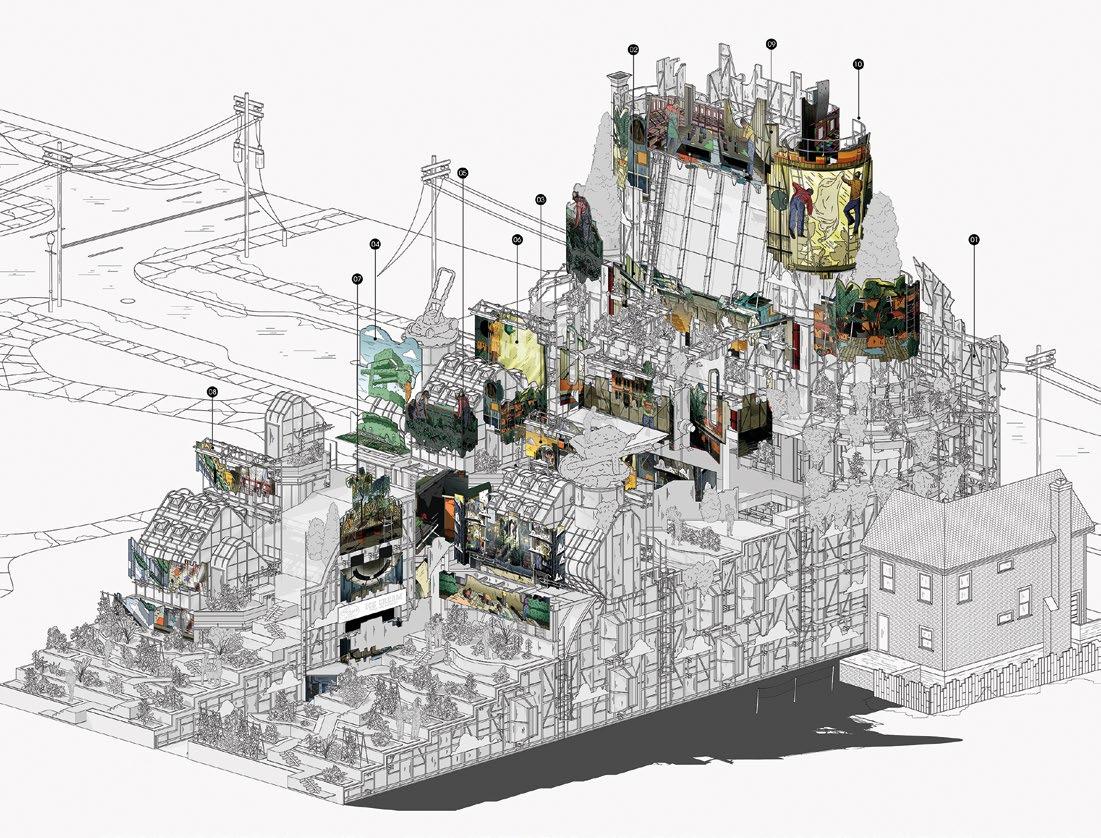

11.6–11.7 Ka Chun Ng, Y5 ‘The In-between Goodsyard Estate.’ The project challenges the orthodox master planning strategy that has contributed to the homogenisation of cities and displacement of local communities. Situated within the gentrified area of Shoreditch, the project redefines the roles of gardens, terraces, hedges, gabled walls and façades. It ultimately creates a new public-private gradient and urban scenery that embodies diversity and inclusivity.

11.8 Chia-Yi Chou, Y5 ‘Silvertown Battery Park’. Silvertown Battery Park is a scientific testing ground that portrays every possible and impossible technology. It is both an off-grid energy infrastructure and a vibrant public space for local communities. The techno-parkscape demonstrates bold and trivial science imagination in a playful and immersive manner, while the working infrastructure celebrates its industrial history and brings Silvertown into the next stage of transformation.

11.9 Chuzhengnan (Bill) Xu, Y5 ‘(Un)Folding Terra Incognita: Charlesgate Revitalisation’. Charlesgate in Boston, which connects the Back Bay Fens to the Charles River, forms the first link in the parkland chain known as the Emerald Necklace. The project explores ways in which the parkland could be restored and improved in a future

that has fewer cars and in which redundant expressways are removed. The proposal is an urban retreat landscape that documents the history of the parkland chain and includes spaces for public education. The architecture reuses remaining overpass piers as dominant structures, allowing the marshland to control the flow and cleanse the creek, creating a new blue-green infrastructure.

11.10 Harry Andrews , Y5 ‘Deconstructing Nostalgia’. Creating a new urban realm in harmony with the context of Brixham, the scheme blends the application of nostalgic architecture with a new local vernacular that operates as a catalyst for the growth of the town and its renewed sense of place in a climate of post-Brexit austerity.

11.11 Ernest Chin, Y5 ‘Idealistic Pragmatism’. In Singapore buildings are often prematurely demolished. Driven by the demolition of a childhood home, the project proposes ‘Immovable Social Objects’ and ‘Best Friends’ within a prototypical landscape. The former are protected everyday social spaces, while the latter consist of enveloping housing attachments that protect them. While redevelopment is an ever-present concern, one can consider radical possibilities to protect what remains dear.

11.12 Jiawei Fan, Y4 ‘Curating Landfills: Re-imagining Coastal Waste Landscape’. In response to the East Tilbury managed retreat plan, the project envisions a restoration facility which breaches the sea wall and acts as a buffer for the landscape behind it. Through repurposing inert building waste from this coastal landfill site, the proposal explores an alternative inhabitation of the interstitial zone between wet and dry.

11.13, 11.15 Maya Whitfield, Y5 ‘Traces of the Past; Forming Tiberias Field School’. As the historic city of Tiberias, founded in AD 19, continues to exist in a state of neglect and disrepair, this project proposes a restoration, learning and research facility, dedicated to improving and mobilising both the residents and the annual occurrence of visitors to the site. The project integrates community construction alongside an architecture that provides a performative dwelling; it is layered with fragments of the city, both old and new.

11.14 Zhi Qian Jacqueline Yu, Y4 ‘The Weathering Yard: Façade Prototype Testing Ground in Central London’. As we navigate the challenges of Generation Anthropocene, we must consider non-human agency in shaping our world. By embracing the idea of weathering, we can appreciate architecture as a dynamic, evolving entity – something influenced by both nature and human interaction rather than a static, unchanging object. The project is specifically interested in accelerated weathering testing for 1:1 façade prototypes.

11.16 Emily Child, Y5 ‘Form Follows Phygital’. This project is a climate change response strategy for MIT, USA against future flooding risk. It proposes digital circular management techniques of preserving cultural heritage by dismantling existing buildings threatened by flooding into a bank of ‘physical fragments’ for reuse. Parallel physical and digital modelling techniques were used to propose a flood-resilient structure that integrates with the residual campus buildings.

11.17 Jennifer Oguguo, Y4 ‘Islington’s Living Rooms’. Exploring the integration of feminist theory with architectural design practice, the project proposes ‘Islington Public Studios’, a live/work programme devoted to craft education. This axonometric summarises the central body, an interpretation of a Georgian terrace house, surrounded by public space; this is mediated through differing applications of public and private to create a craft-informed third space.

PG11 continues to challenge the paradoxes of preservation versus progress and wilderness versus culture. We examined the radical, even revolutionary ideas that stitch together the past, present and future, revealing the cultural and political complexity of the built environment. In a world more dangerous yet more open to opportunity than ever, these notions are also affected by ‘the progress paradox’ –the more forward progress is made, the more problems are created.

Our interest in environments that exhibit displacement, restoration, redundancy, progress, dormancy and future living is exemplified by the UK’s National Parks. Initiated by the 19th-century ‘Freedom to Roam’ movement, large areas of land are now protected by law for the benefit of the nation. This is due to their special and particular qualities of countryside, wildlife and cultural heritage.

Until relatively recently little acknowledgement was given to thinking about nature as a system. Boundaries were laid out according to convenient political or economic interests rather than to reflect ecological realities. As keystone institutions of environmental conservation, the parks are operated as managed systems: ‘interactive ecologies’ of people, nature, landscape and infrastructure. Charged with protecting fragile ecosystems and vulnerable regional identities, they also – more now than ever – act as outdoor playgrounds.

The National Parks, themselves often cultural paradoxes, are also influenced by political activities and decisions. Changes taking place outside their boundaries can have a tremendous impact on preservation efforts within. This can result in damage to local economies and environments, overloaded rural infrastructure and even threats to their conservation goals and nature reserve status, particularly where the weight of tourism is unsustainable.

This year students looked at temporal and spatial cultural scenarios to reveal underlying processes that continue to affect our built and natural environment, our societal institutions and the fascinating consequences of adapting the cultural imaginary. They asked how legislated territories should accommodate cultural and environmental changes and how future transformations in society and the natural environment could be reflected in the built environment. Students also explored the role of architecture in a complex ‘interactive ecology’. Finally they considered what might be the implications – and, more importantly, the opportunities – of designing architecture for uncertainty and alternative futures.

Year 4

Harry Andrews, Chia-Yi Chou, Yu (Pearl) Chow, Ka Chun (Mark) Ng, Charles Pye

Year 5

Theo Clarke, Michael Holland, Justin Lau, Kit Lee-Smith, Rory Martin, Iga Świercz, Yun (Kenny) Tam, Annabelle Tan, Zifeng Ye

Technical tutors and consultants: Rhys Cannon (Gruff Architects Ltd), Stephen Foster (Foster Structures), Ioannis Risoz, (Atelier Ten)

Thesis supervisors: Gillian Darley, Kelly Doran, Murray Fraser, Daisy Froud, Elise Hunchuck, David Rudlin, Tania Sengupta, Oliver Wilton

Critics: Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Doug John Miller, Aisling O’Carroll, Alicia Pivaro, Tim Waterman

11.1 Zifeng Ye, Y5 ‘Anxious Nostalgia’. This project is a study into Shanghai’s waning living space, combining typological research into the city’s disappearing lilong neighbourhoods with speculative reimaginings of modern domestic space. The project seeks to reinvigorate old communities and encourage ad-hoc spatial appropriation in the otherwise regimented cosmopolis.

11.2 Chia-Yi Chou, Y4 ’Foreston Keynes: Carbon Capture in a Progressive Town’. Milton Keynes has always been an experimental city that leads bold future-proofing schemes. Responding to the city’s ambition of becoming carbon-neutral, the building captures carbon dioxide and generates carbon credits. It also erects a new image that celebrates and reshapes the modernist town.

11.3 Harry Andrews, Y4 ‘The Park Ascending’. The project provides protective measures against the physical pressures and impacts of tourism by amplifying the sense of place. By restoring an emotional connection with the landscape, the proposal reveals the undiscovered networks of lost navigational methods in the national parks.

11.4 Ka Chun (Mark) Ng , Y4 ‘Casting Redcar’. In response to the demolition of the Redcar Steelworks complex, the project envisages a landscape archive and research centre where Redcar’s industrial heritage will be celebrated and remediation of soilscapes will be carried out over a 50-year span. Sited in the unique slag region of South Gare, the design explores both landscape casting and tilt-up construction as ways of revealing the industrial scars of the contaminated site and as an opportunity for phytoremediation of the polluted landscape.

11.5 Yun (Kenny) Tam, Y5 ‘Keystone Architecture: A Wilding Experiment’. The project challenges architecture’s role in nature by mimicking ecological interaction with endangered species. The proposal stitches together five keystone architectures along the Ledge Route to the summit of Ben Nevis. It encourages visitors to participate in a wilding experiment, while at the same time generating empathy for these fragile spaces.

11.6–11.7 Justin Lau, Y5 ‘Simulating National Parks’. In the age of ecological emergency, is it time for our capital to become Britain’s newest national park to safeguard our agriculture, water, energy and people? Roughly 47% of London is made up of green space. This green space is a vital asset in building a climateresilient city that can combat rising temperatures and flash floods. The project reverses the traditional notion of national parks in rural settings and uses ecology as a form of architectural construction for London’s industrial landscapes.

11.8 Annabelle Tan, Y5 ‘Past, Present and PostTropicality’. Colonial spectres and contemporary evolutions of tropicality continue to shape Singapore. Framing tropicality in terms of scarcity and affordance, the proposal unmakes neo-colonial vestiges of tropical solutions and remakes a ‘nature-ficial’ landscape of affordance. By linking a threatened forest to a nationally recognised nature reserve, the scheme dissects social and physical ideas of scarcity, creating a new set of values around productive and performative dwelling practices that synthesise nature and culture and lead towards a nascent monument of post-tropicality.

11.9 Iga Świerc, Y5 ‘ Moving Upwards: Mimicking Mersea’s Resilient Relocation’. The diverse ecosystem and community of Mersea Island, Essex, are under threat of extensive coastal erosion and flooding. To address this issue, a new managed retreat is proposed. The self-made Mersea Commons design plan supports the community in creating a common methodology for the relocation. Designed with the input of the community, local and bioregional scales allow for multiple futures for the new Mersea Commons. The participatory citizen science

model recognises and addresses the needs of the residents of Mersea Island while enabling the renewal and preservation of its ecosystem.

11.10 Michael Holland, Y5 ‘A Peat Protopia’. This research and restoration facility is dedicated to furthering our understanding of peatland habitats through an architecture in constant conversation with the landscape. The building systematically restores damaged peat through a cyclical process of saturation, while simultaneously questioning wider discussions of land ownership, sustainable land management and rewilding.

11.11 Theo Clarke, Y5 ‘Hijacking the Elan Valley’. The project leverages the existing rich hydrological landscape of the Elan Valley reservoir system in Wales to impose an infrastructural energy-buffering stratum across the valley’s vast watershed. The carefully orchestrated pumped hydro system creates the framework for a ‘buffering town’, a quasi-bulwark/ communal housing development where one can experience the extremes of whitewater rapids passing underfoot, while tending an allotment, before a game of lawn tennis.

11.12–11.13 Rory Martin, Y5 ‘Tales from the Flood’. As the people of Morfa Borth, Wales, discover their town will no longer receive the necessary sea wall defence funding to protect them from rising sea levels, the residents band together to preserve the soul of their community by mobilising to start their journey to higher ground and safety.

11.14–11.15 Kit Lee-Smith, Y5 ‘ Transboundary Massif’. The project questions the need for Portland cement in the Albertine Rift in Africa, and instead explores the potential of geopolymer cement from mine tailings in north Burera, Rwanda. The project integrates community construction within Rwanda’s extraction policy, minimising building footprints in this densely populated area. It proposes a ‘construction-arium’ to express, explore and educate inhabitants, utilising and stabilising past industrial scarring through geopolymeric lateritic soil blends and techniques.

11.16 Charles Pye, Y4 ‘Ruining the Road’. The project encourages the abandonment of motor vehicles within the city, while simultaneously saving the UK’s national parks from increased environmental damage. City roads also undergo reform, nurturing new national park typologies within the urban fabric.

11.17 Yu (Pearl) Chow, Y4 ‘Snowdonia Plant-nation’.

A paper mill for the e-commerce giant Amazon within a carbon-offsetting tree plantation in Wales. The project tackles themes of exploitation and codependency between the urban and the natural, and explores the power dynamic between the money-hungry and the carbon-hungry. It serves as a pioneering project through its use of locally sourced timber from the surrounding forest and its derivatives produced as by-products during the cardboard-making process.

Laura Allen, Mark Smout

This year’s brief challenged students to rethink the edges and intersections between landscape and the urban realm, hand-in-hand with those between public and private space. These relationships are fluid, volatile, contested and reciprocal, and challenge the polarised notions that the unit continues to revisit: preservation versus progress and wilderness versus culture.

Our rural environment is substantially cultured as ‘wilderness kept in check’ or for the production of vast quantities of food – 70% of the UK’s land is agricultural.1 Environmental technologies and nature have become inextricably linked; cutting-edge technologies are increasingly deployed that engineer nature from the micro scale of genetically modified crops to the global scale of GPS agricultural automation. Furthermore, the landscape is crisscrossed with infrastructural networks, inter-urban links of road and rail that also connect cities with their surrounding rural areas and the regions of supply with the centres of demand. We asked, What are the radical outcomes of the synthesis of urban and rural spaces?

A further blurring of the distinction between rural and urban, and private and public is the privatisation of nature. Natural capital – stocks of natural assets, access to and control of material resources, even forests and fields, soil, geology, water, air and all living things –are controlled by property rights where commercial agendas can overturn seemingly common sense. In our cities too, public spaces are being transferred to private ownership – Privately Owned Public Space (POPS) – with byelaws, urban design, surveillance and policing to control perceived misuse. We asked, How can architectural and technical innovations alleviate the pressure of private encroachment on public environments?

We can see that the future of the city is inextricably linked to that of the rural. Controversially, some advocate for re-commoning –the application of a ‘sharing economy’ to urban space, borrowed from archaic rural environments that persist today. Contemporary commons are not only a material resource; they are also a form of social organisation that could be revisited in our urban environment. During lockdown, the use of urban parks soared where commoning laws – the rights of certain individuals to enjoy the property of others – were exploited. The Victorian parkland concept of ‘rational recreation’ – the ordered and orderly use of landscape – was stretched to breaking point. We asked, How can principles of commoning be applied to urban space?

Year 4

Theo Clarke, Michael Holland, Justin Lau, Kit Lee-Smith, Rory Martin, Iga Świercz, Yun Tam, Annabelle Tan, Zifeng Ye

Year 5

James Cook, Peter Davies, Meiying Hong, Thomas Leggatt, Liam Merrigan, Jack Spence, Sarmad Suhail, Ryan Walsh, Yitao Zhu

Thank you to Rhys Cannon for his invaluable Design Realisation teaching, structural consultant Stephen Foster and environmental consultant Ionnis Rizoz

Thesis supervisors: Matthew Barnett Howland, Mollie Claypool, Edward Denison, Daisy Froud, Polly Gould, Gary Grant, Jan Kattein, Oliver Wilton

1. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2015), Agriculture in the United Kingdom 2014 (accessed 22 June 2021), gov.uk/government/ statistics/agriculture-inthe-united-kingdom-2014

11.1 Peter Davies, Y5 ‘The Stone Language Centre’. Sited in the dormant Welsh granite quarries of Nant Gwrtheyrn, the project advocates a revival for low-carbon structural stone construction and demonstrates the whole-life benefits of stone, from extraction to material reuse. Monolithic stone buildings form The Stone Language Centre, creating a space for learning and discovery within the rich Welsh landscape.

11.2 Thomas Leggatt, Y5 ‘A Corn(ish) Community’. The Cornish coastline is being increasingly appropriated by outsiders, for outsiders, specifically second-home owners. Using a pub(lic) model, a dialogue is established between the architect and community in the design of a new village for second homeowners and local residents. The model encourages collaborative design and an immersive understanding of the project as a whole.

11.3 Annabelle Tan, Y4 ‘The River, Restoration and its Rituals’. Sited along the River Wensum in Norfolk, the building is a roving restoration scheme that visits rural villages to restore the vulnerable chalk river while engaging and empowering the local community to sustain an intimate relationship with the environment through rituals and beliefs. The building is simultaneously a restorative and ritual machine, marrying ecological values with the process of restoration.

11.4 Kit Lee-Smith, Y4 ‘Orkney’s Udal Energy’. Orkney’s foreshore and landscape boundaries, eroded by anthropologically driven climate change, are explored via an infrastructural design for the archipelago’s preservation. The design uses archaeological language and materiality alongside stone machining techniques to expose the relationship between the building foreshore and community-centric architecture.

11.5 Rory Martin, Y4 ‘The Hiker’s Retreat’. Situated in the intertidal mudflats off Osea Island in the Blackwater Estuary, the project creates a ‘hearth’ –a lost historical focal point in the home and a place for people to reconnect and share stories and experiences. The project works in harmony with the surrounding historical vernacular of the Essex coastline by referencing traditional building. The central kachelöfen (stove) stands as a beacon of sustainability and efficiency.

11.6 Theo Clarke, Y4 ‘ Floreat Blaenau’. The town of Blaenau Ffestiniog, strewn with glaciers of cascading waste material, is one of seven identified sites to be included within a new UNESCO World Heritage bid. The project challenges the vision of UNESCO by highlighting Wales’ historical relationship with Patagonia, resulting in the formation of a Patagonian enclave. Analytical, physical and digital experimentation reveal elemental and man-made forces, exposing the visitor to the uncanny implementation of mechanical installations.

11.7 Zifeng Ye, Y4 ‘Inhabiting Common’s Nature’. The project seeks to establish a woodland common inside an old gravel quarry by the East Tilbury coast in Essex. Facilities allow access to the site and initiate a century-long programme of reforestation. The design aestheticises ‘waste’ land and materials, in order to rekindle a common interest in living with unappreciated landscapes.

11.8 Yun Tam, Y4 ‘Percolate Agri(Park)’. Merging agriculture, water and park in a symbiotic relationship, the project brings food currency to the citizens of Hong Kong by bridging the gap between the sensory connection of the public to the origins of food and the enjoyment of the recreational parkscape.

11.9 Iga Świercz , Y4 ‘Dressing the Scottish Landscape’. The ministry, located in the Cairngorms, has a profound understanding of the Scottish ancestral textile industry by creating soft architecture that also promotes a tourism strategy for the Highlands. The clothed interiors recall

domestic rituals, the art of weaving, seasonality and the colours and textures of the Scottish tradition.

11.10 Justin Lau, Y4 ‘Leigh Frontier’. Extreme changes to global climates are expected to breach over 1,000 historic landfill sites on the British coast, through erosion. The increasing risk poses serious pollution damage to the estuarine landscape and beyond. ‘Leigh Frontier’ proposes a chained fortification embedded along the eroding edge of Leigh Marshes, allowing time to remediate one of the most toxic old landfill sites in the UK.

11.11 Michael Holland, Y4 ‘The Commons Community Centre’. The project raises awareness of the growing rate of food poverty throughout the borough of Hackney. It tackles the often negative associations of food banks, through the integration of commoning principles that inspire a sense of ‘togetherness’ and community expression, celebrating the sharing of culture, food, resources and knowledge.

11.12 Sarmad Suhail, Y5 ‘Power Palace Park’. The idiosyncratic Crystal Palace is reimagined as the showcase for the ‘Green Industrial Revolution’, providing a model for parks to become energy generating and carbon-capture resources. Ersatz materials and visual trickeries blur the line between what is ‘park’ and ‘building’, to provide a locally sourced, national-facing infrastructure.

11.13 Ryan Walsh, Y5 ‘Digital Archaic Commons’. How do we build a future where personal digital fabrication is utilised towards the common good? This project explores how users of commons, such as FABLAB, apply sophisticated digital manufacturing and scanning tools to produce decentralised architecture.

11.14 Yitao Zhu, Y5 ‘Parking Rectory Farm’. Rectory Farm is a derelict site near Heathrow, where a new public park is to be built on top of an underground logistics facility. The project challenges the park typology and envisages an alternative landscape for the site, which addresses potential financial crises. A mixture of housing, industry, infrastructure and landscape encourages richer interactions between domestic and park activities.

11.15–11.16 James Cook , Y5 ‘Inhabitable Billboard Vernaculars: Brush Park Agrihood’. Set in Detroit, ‘Brush Park Agrihood’ reimagines the potential for hoardings and billboards. Drawing inspiration from Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour’s book Learning from Las Vegas (1972), the hoardings stage moments in the storyline of construction and provide a framework for inhabitable spaces, which inevitably spill out into the backlands of the site. The agrihood’s infographics and community messages, embedded within the framework of the building, inform people about Detroit’s environmental crises.

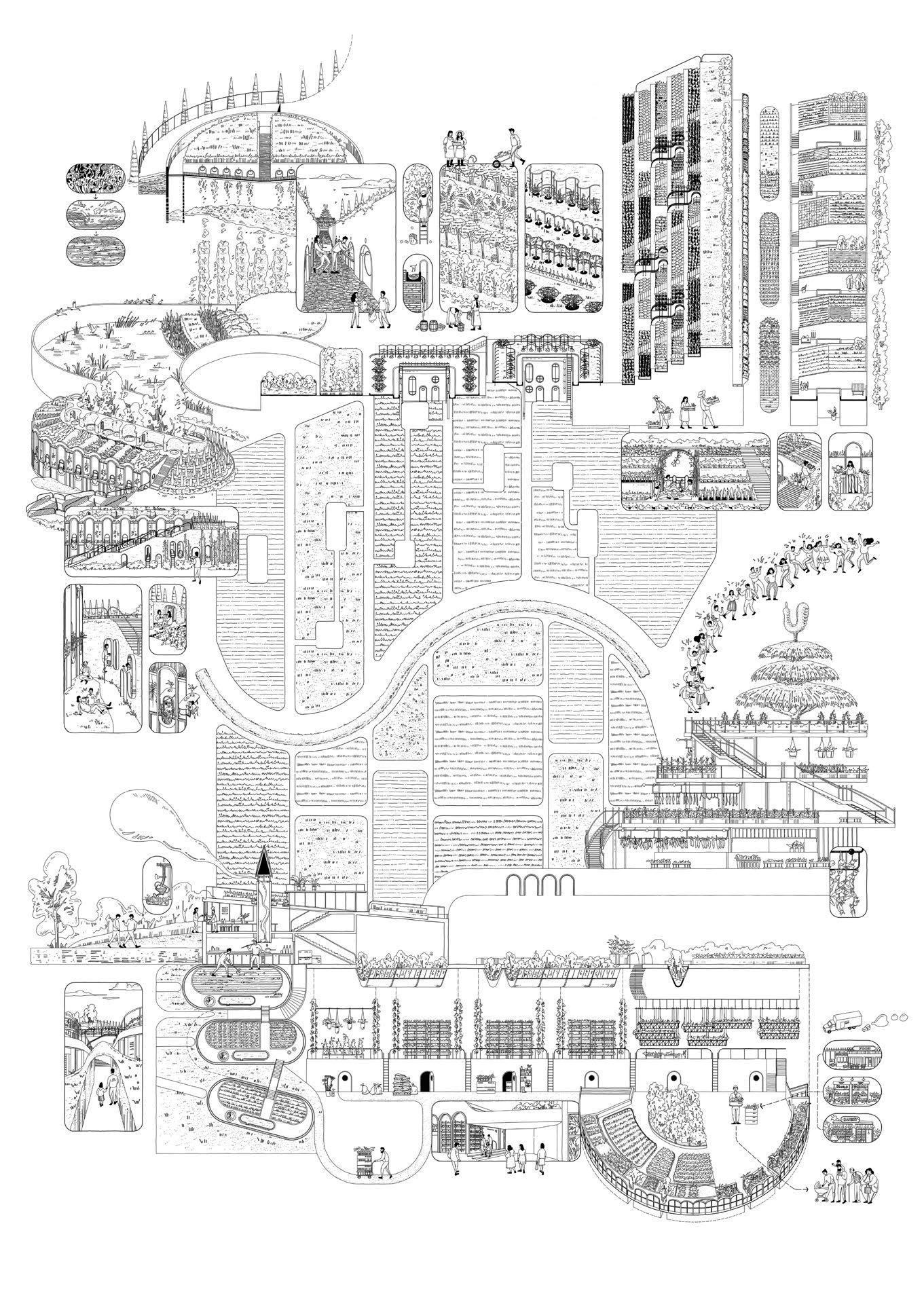

11.17 Meiying Hong , Y5 ‘Productive Landscapes: Food community in Regent’s Park’. To counteract food poverty and waste post-pandemic, this project replans a section of Regent’s Park as an experimental food community, integrating housing with food production, collection, distribution and disposal. The terraced gardens, roof orchards and growing lands form a productive landscape in an overlooked section of the park.

11.18 Jack Spence, Y5 ‘The 4th Epoch: Reinhabiting desolate landscapes’. Highlighting the significant climate threat facing the UK’s coastline, this proposal looks to reinvigorate Hurst Castle in Hampshire through the siting of a research outpost. Digital inhabitation of the surrounding gamified landscape also enables the immersive engagement of ‘virtual researchers’ from around the world with the vulnerable coastline.

Incompleteness, whether intentional or accidental, brings opportunities for reinvention. This year, we rebooted stories of change and adaptation, of bold ideas and incomplete visions. The intriguing qualities of the incomplete invite alternative futures. Unresolved stories lead inevitably to new endings with substitute narratives. In the worlds of architecture, music and art, incompleteness carries with it tantalising indications of the creative process. Drawing on this back catalogue of defunct imaginings, unbuilt and incomplete buildings and the ruins of obsolete architecture, we listened, adapted and reimagined, creating alternative futures and future pasts, designing new relationships with historic and contemporary contexts.

Our work is informed by stories from Sicily – the site for our field trip and major projects – which demonstrate architecture’s responsive and fluctuating relationship with landscape, politics, culture and the environment, four critical territories of engagement. Partially constructed architecture – abandoned in a state of unreadiness –is so widespread in Italy and Sicily that there have been calls for it to be distinguished as its own architectural style: ‘Incompiuto’. Deserted stadia, hospitals that were never occupied, and skeletons of structures forsaken mid-construction, their futures suspended in time, stand as ruins of modernity. Bridges, theatres, churches, and numerous other public works were planned to revitalise communities and capture available funds before they ran out. Hundreds of buildings were subsequently aborted at every stage of construction, these now obsolete architectures, their futures interrupted, became instant ruins. Some have been revived by unplanned-for activities, but most remain incomplete visions in suspended animation, the legacy of political hubris and economic recklessness. Prince Fabrizio, the protagonist of The Leopard, Sicily’s most famous novel, declares, “Tutto deve cambiare perché tutto rimanga lo stesso ”: Everything must change in order for everything to remain the same.1 His proclamation refers to Sicily’s 19th-century struggle with social change, but seems equally apposite today.

But this change is territorial as well as societal. Short-lived volcanic islands in the seas surrounding Sicily, ghost towns, abandoned houses and patched-up structures which pepper the landscape are reminders of Sicily’s long history of geological instability and cataclysmic earthquakes. Rebuilt towns such as Noto stand as near-perfect examples of Sicilian Baroque, while the relocated town of Gibellina Nuova is a part-deserted postmodern experiment in town planning and cultural engineering.

Students have pursued individual research agendas and projects addressing landscape futures, water security, mass migration, corruption, environmental collapse, tourism, preservation versus progress, social inequality, archaeology and agricultural tourism.

Year 4

James Cook, Peter Davies, Meiying Hong, Thomas Leggatt, Rory Martin, Jack Spence, Sarmad Suhail, Ryan Walsh, Yitao Zhu

Year 5

Siqi (Scott) Chen, Sacha Hickinbotham, Theo Jones, Karolina Kielb, Liam Merrigan, Rachel Swetnam, Maxime Willing

Many thanks to Rhys Cannon for his inimitable practice teaching and Stephen Foster and Ioannis Rizos for their technical support

Thanks to our critics Richard Beckett, Kyle Buchanan, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Rhys Cannon, Ness Lafoy, Claire McAndrew, Doug Miller, Kyrstyn Oberholster, Naomi Rubbra, Ellie Sampson

1. Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa,The Leopard, (1957), 1960. Milan: Feltrinelli / London: Vintage

11.1 Rachel Swetnam, Y5 ’Opera Dei Lus’. The Sicilian Marionette, Opera Dei Pupi, is a dying but cherished art at the very centre of Sicilian storytelling traditions. Opera Dei Lus is a puppet theatre in Ortigia, Sicily that may be used as a repository or archive for stories from the community and a chance to contribute to Sicily’s story culture from a personal and contemporary perspective. The theatre is designed around suspension and layered frames designed to distort perceptions of scale – of a puppet, human, and theatre.

11.2 Peter Davies, Y4 ‘Carving Cusa: Sculpture School’. The ancient limestone quarries of Cusa were abandoned in 409 BC. To this day the site lies incomplete, with half-cut columns embedded within the quarry and crumbling fragments strewn across the landscape. The sculpture school acts as a vessel to reactivate the site. The project uses all elements of the limestone extraction process from nose to tail: carving studios are nested within quarried voids, amphitheaters are forged from open bench quarry scars and byproducts are reused to create new landscapes, blending old and new.

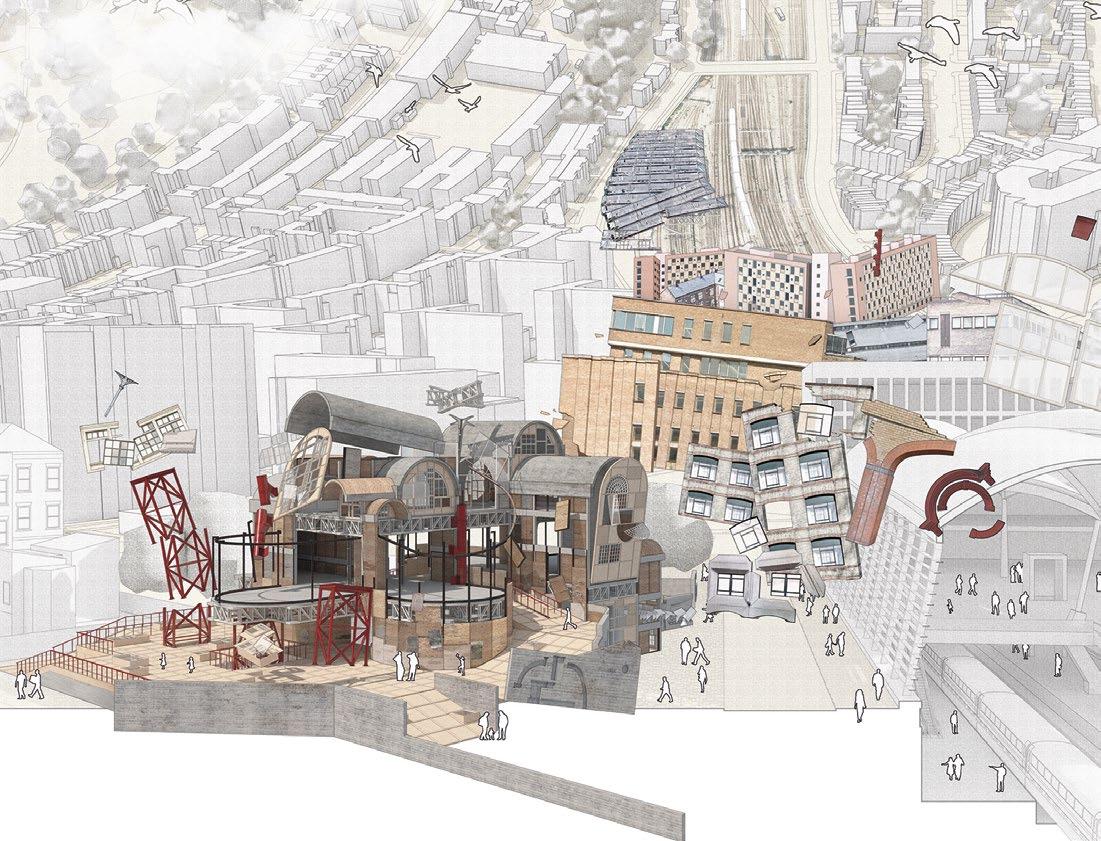

11.3, 11.5 Meiying Hong, Y4 ’Zero Waste Ortigia’. In the last five years, Sicily has a serious waste-management crisis. In response to the unlawful management of waste, this programme directly utilises the recycled waste as key building components, showing the potential and value of these materials. As well as being a plant disposing of the sorted waste, the centre encourages public participation in the recycling process. Adapted to the traditional waste collection methods, donkeys work as ‘organic machines’. 11.4, 11.6 Sacha Hickinbotham, Y5 ’Civic Palimpsest for Future Learning’. As the European refugee crisis brings unprecedented amounts of foreign arrivals, this research studies the broad social integration of migrants and refugees into Palermo, Italy. Churches are historically one of the most dynamic architectures to exist in cities – altered, deconstructed and reconstructed with every new colonisation. The project deals with designing into this heritage, opening the building to its urban context and altering its function to serve a new purpose. Fieldwork, site visits and interviews formed a foundation of knowledge, resulting in a series of models that were offered back to community members and politicians. 11.7 James Cook, Y4 ‘Pop-Up Parliament’. Parliament aims to deliver a temporary House of Commons facilities for MPs during the extensive refurbishment of the deteriorated fabric of The Palace of Westminster. This proposal is a critical constituent in the manufacturing of a modern government. The design reuses and manipulates waste byproducts and building technologies as part of its renovation programme. The drawings are a critique on the political muralism of Parliament that reveal the disparities and social injustices between MPs and the general public.

11.8 Siqi (Scott) Chen, Y5 ‘Unexpected Landscape’. This project looks at the incompletion of scale through miniature models, creating unexpected landscapes from different corners of the student’s flat. The study sets up different scenes with micro-environment using daily objects, constructing miniature worlds full of mystery and wonder. 11.9–11.11 Siqi (Scott) Chen, Y5 ‘Reimagining the “Incompiuto”: Siciliano Archaeological Park’. Sicily’s landscape is dotted with incomplete architecture –a representation of political corruption and planning disasters of the 1990s. This study identifies the ‘Incompiuto’ as an architectural resource for the construction in the town of Giarre, memorialising this period of Sicilian history and providing six new community buildings.

11.12 Sarmad Suhail, Y4 ‘Borgo Palermo’. Sicily’s agricultural industry has rapidly declined following decades of reduced rainfall and failed infrastructure projects. The Sicilian Agricultural Board has outlined its

revival through ’Agritourism’. Borgo Palermo, set in the heart of Palermo, is designed to achieve ‘accreditation’ despite its urban location. The typology of the urban block informs its design language, the building acting as a wall surrounding a landscaped farm, providing rurality, the first step in reviving the ‘incomputio’ Via Dei Borghi scheme that aims to link up 13 abandoned hamlets built by Mussilini in the 1930s.

11.13 Yitao Zhu, Y4 ‘Collaging Euston’. The HS2 project, is the biggest construction site in Europe, with hundreds of homes, local businesses, and streets completely bulldozed. While generating considerate amount of building waste, HS2 also erases collective urban memories of the area. This project adopts various ways of material reuse and showcases a possible way where memories can be continued.

11.14 Jack Spence, Y4 ‘The Acqua Duomo’. Extreme changes to the global climate and ocean ecosystem are forecast in the coming years. This project outlines a speculative future environmental scenario in a Sicilian coastal town. The project creates a synergy with the landscape by mimicking the metaphorical ‘breathing in’ of the ocean, exploiting the tidal movements and solar distillation to generate potable water for the local community. The use of a salinity device to roam the highly saline waters enables the ocean’s everchanging ecosystem to be monitored.

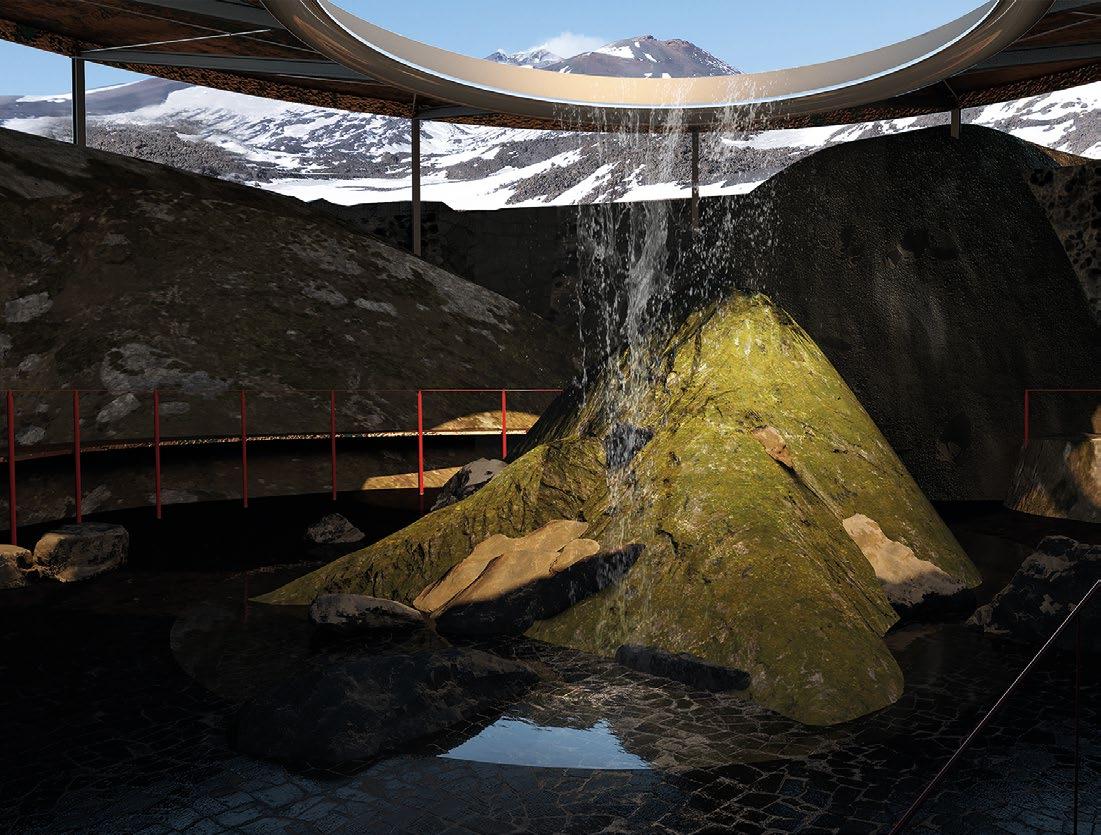

11.15–11.16 Karolina Kielb, Y5 ‘Etna, Mountain of the Mind’. As an alternative to data-driven understandings of landscapes as signifiers of climate change, this project aims to restore the emotional connection between the mountain and the mind. This engagement is used as a protective measure to remove the pressures of tourism from fragile mountain environments. An alternative volcanic landscape is proposed to reduce the impact of tourism on the summit. A series of architectural and landscape interventions amplify specific qualities of site and our historical engagement with mountainous landscapes.

11.17 Ryan Walsh, Y4 ‘Re-Making Poggioreale’. The town of Poggioreale was ruined by an earthquake that struck the Belice valley in 1968. This project proposes a phased return to inhabiting the ghost town over the next century in the form of retention and self-supported structures, built from the debris left behind by the earthquake, to support a forest garden landscape. It uses 3D scanning to conduct the archaeological assessment and restoration of the ‘digital twin’ of the site, mirroring its dilapidated character.

11.18 Thomas Leggatt, Y4, ‘Generation Montagna’. With eco-corruption becoming a major threat to Sicily’s quest for sustainable energy, this project explores the ways in which energy can be covertly generated and stored. By applying a decentralised methodology, a self-sufficient energy network is created, disguised as sheltered accommodation for Sicily’s ageing population. A typical Sicilian town is compressed into the accommodation, thereby emphasising the capacity for architecture to sustain traditional ways of life within a modern context.

11.19 Maxime Willing, Y5 ‘Disjecta Membra’. Alongside China, Italy has the largest number of UNESCO World Heritage sites in the world, but with the wider economic issues afflicting the country and particularly the region of Sicily, there is a growing concern that this heritage will crumble to dust. The project considers the resolution of this issue through the application of a 19th-century form of education: the production of cast replicas of historical artefacts and fragments for exhibition. A landscape of copies that develop their own history, they become a record of an original that will only ever degrade further.

The Latin phrase terra incognita, meaning ‘unknown land’, was used by cartographers in the Age of Exploration (early 15th to early 17th century) to denote those territories of the globe that were unknown, unexplored or undocumented. Geographical terra incognita is now practically inconceivable, as the prospect of discovering uncharted land has all but disappeared. Myth and imagination are replaced by indisputable physical reality, as most of the Earth’s surface has been digitally surveyed, if not charted, in minute detail. Yet, for reasons such as the shifting topographies of climate change, renegotiated political borders and evolving infrastructures, a map is outdated as soon as it is made. Flaws caused by digital glitches and the inaccuracies of new scanning technologies add yet another layer of redundancy and ambiguity. Our unremitting drive for ‘progress’ and search for knowledge has produced many Ages of Exploration, including missions to chart the ocean depths and voyages extending beyond our galaxy. ‘Terra incognita’ is now more likely to be used metaphorically, to signify uncharted territories in other areas of exploration, such as fields of scientific research. This year, we asked: ‘What is the current focus of global exploration?’ and ‘What is the role of architecture in future thinking?’

It is not down in any map; true places never are.1

Far from being ‘lost in space’, the unknown is, fundamentally, the territory of speculation and discovery. The unit focused on the moving target of the future at its most enigmatic, uncovering or proposing ideals and didactic models for living, evoking real or imagined scenarios and reviving forgotten innovations.

All who claim to foretell or forecast the future are inevitably liars, for the future is not written anywhere – it is still to be built.2

Following in the footsteps of the founders of the Alpine Club French architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) and English art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900), we endeavoured to develop a ‘better knowledge of mountains through literature, science and art’ 3 on a grand tour of the sublime Swiss Alps. The pristine wilderness is remarkably geotechnically manipulated and undergoes dramatic seasonal transformations, seen not only in the couture of the ski slopes but also in the ancient agricultural practice of ‘transhumance’: the moving of livestock from lowlands to upland grazing meadows. The awesome dominance of its sublime and elemental mountains – bucolic alpine panoramas with chocolate box views of bell-jangling cows grazing on wildflower meadows – belies a culture of modernity and scientific innovation. The majority of projects are sited amongst the visual abundance and landscape utility of this living laboratory.

Year 4

Siqi (Scott) Chen, Sacha Hickinbotham, Theo Jones, Karolina Kielb, Liam Merrigan, Rachel Swetnam, Maxime Willing

Year 5

George Bradford-Smith, Andrew Chard, Wei-Kai Chu, Oliver Colman, Stefan (Dan) Florescu, Paul Humphries, Douglas Miller, Naomi Rubbra, Nicholas Salthouse

Many thanks to Design Realisation tutor Rhys Cannon, and Stephen Foster for Structural consultancy

1. Melville, H., Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (London: Constable & Co., 1922)

2. Godet, M. and Roubelat, F.,’Creating the future: The use and misuse of scenarios’, in Long Range Planning, Volume 29, Issue 2, April 1996, pp164-171

3. Alpine Club Rules, alpine-club.org.uk/ac2/ about-the-ac/mission-2

11.1 Oliver Colman, Y5 ‘Alposanti’. In homage to the Alps as a source of Swiss national identity, ‘Alposanti’ takes compositional cues from the form of a mountain, to create a touristic, closed, world of the future. The project responds to declining tourism figures in Switzerland, partly due to diminishing snowfall due to climate change, and draws on the principles of hyperreality in duplicating and exaggerating culture to create an extensive architectural world of warped ‘Swissness’ within one mega-building.

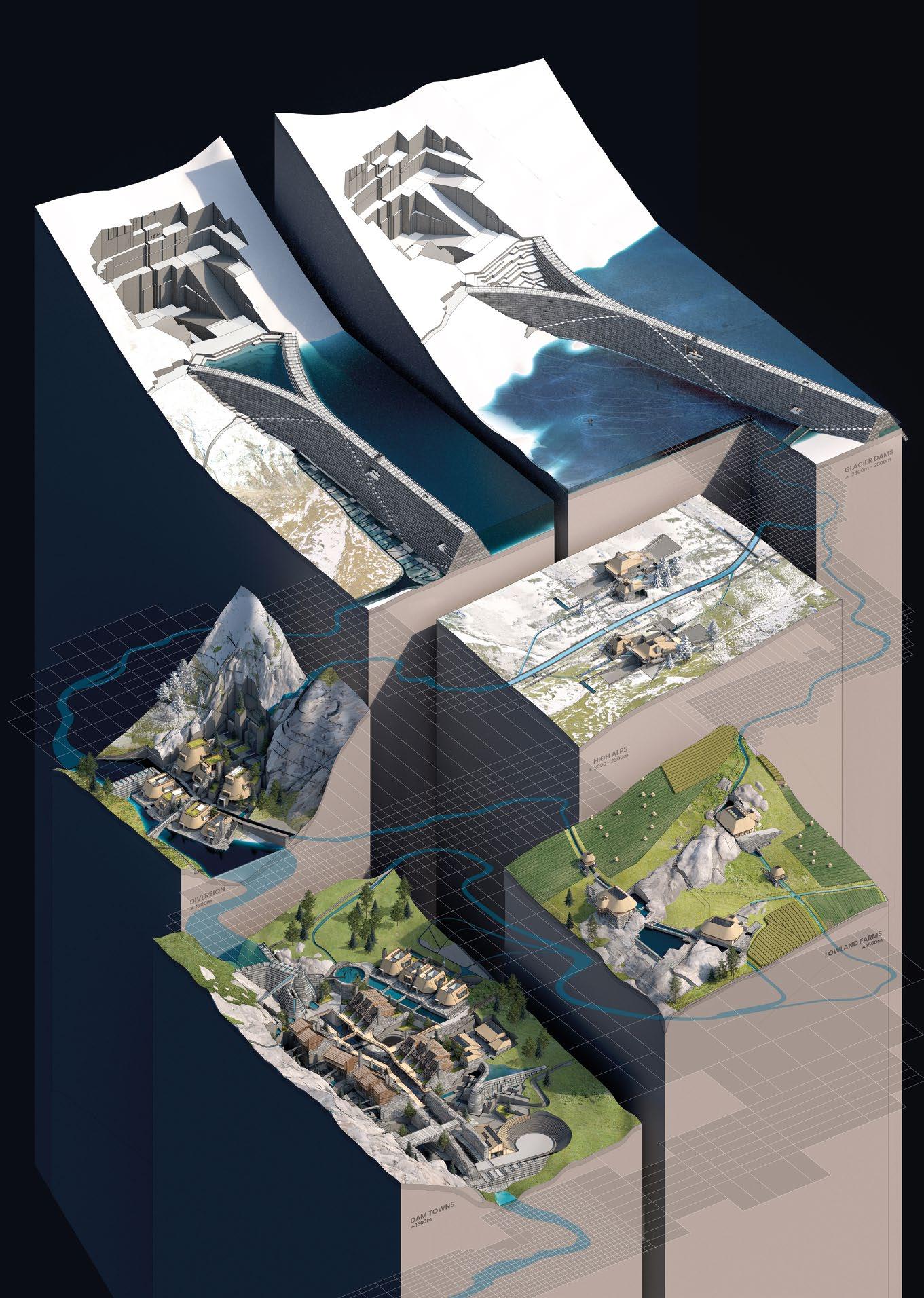

11.2 Andrew Chard, Y5 ‘Reconfiguring the Rhône’. With retreating glaciers affecting river regimes throughout Switzerland, the creation of new water buffering dams is needed. Carved into the emerging granite landscape left behind by the fading glacier, these dams are sustained through the implementation of alpine farming communities, expanding from the growing water network deployed throughout the Rhône Valley over the next century.

11.3 Karolina Kielb, Y4 ‘Re(g)Rhône Glacier’. This project reinstates a Victorian research station on the Rhône Glacier in the Swiss Alps. The building is inspired by the Ice Stupa – a form of glacial grating that creates artificial glaciers – and uses meltwater from the glacier to artificially restore a fragment of the lost landscape.

11.4 Wei-Kai Chu, Y5 ‘Alpine City’. This project reflects on the environmental crisis, caused by rising temperatures, facing mountain ecology among alpine valleys. Initially, a thematic board game was created as a precursor for the scheme to speculate the potential and question the emergent botanic township.

11.5 Naomi Rubbra, Y5 ‘Who is London For?’. A masterplan is typically decided and drawn from the top-down. Here, instead, it becomes an activity by ‘walking alongside’ residents through the site. This site model is a manifestation of the findings; the bright ornaments and their associated timber swatch mimic design responses to issues of surveillance, safety, companionship and nature.

11.6 Nicholas Salthouse, Y5 ‘The Liquidity of Glacial Recession’. As Switzerland approaches ‘peak water’ taken from its glacial reserves, this project considers the relative social construct of ‘water scarcity’. Since many struggling alpine towns depend on seasonal meltwater, a series of key infrastructural interventions form a resilient rind to protect the town, enabling further reconstruction of themselves by serving as 1:1 fabrication templates. This landscape of architectural jigs and civic prosthetics reconfigures the town, allowing rituals of harvest to come to the fore, thus catalysing their regeneration from within.

11.7 Stefan (Dan) Florescu, Y5 ‘Augmenting the Vernacular’.

A new architectural ensemble in Albinen in Switzerland uses AR technology in order to make a step-by-step transition from the urban to the rural landscape, allowing newcomers to discover and understand vernacular architecture of alpine chalets. Initially encountered as a fully immersive AR experience, the virtual elements will gradually fade over time to reveal the physical reality.

11.8 Douglas Miller, Y5 ‘The Harderkulm Transect’. A restored hiking route runs from town square to mountain top in the city of Interlaken, Switzerland. Forming an alternative route to the recently installed funicular, a new transect is formed that crosses various mountainous biomes along which an array of buildings augment and protect the mountainside, whilst providing facilities for the local hikers.

11.9 Paul Humphries, Y5 ‘The End of Technology’. In this project, the city of Zurich in Switzerland is reimagined 50 years from now as Europe’s first ‘smart city’ – but not as we imagine it to be today. This project explores our relationship with data as a series of architectural responses via a new, non-physical boundary – reinstating Zurich’s 16th-century fortification as a data network.

11.10–11.11 Siqi (Scott) Chen, Y4 ‘Nomadic Farm’.

Suffering from a dairy crisis, Switzerland is looking for a solution to save its traditional family farms. This project explores the relationship between nature, urbanity and industrialisation behind the Alpine dairy industry. Situated in Gruyères, the farm is made from timber, straw and hay, with an edible façade for cows.

11.12 George Bradford-Smith, Y5 ‘Manipulating Mont Blanc: Preparing for Martian Frontiers’. Located on the summit of Mont Blanc, this astronaut training facility passively simulates the Martian environment of the Alps, using on accessible extreme environment to recreate another.

11.13 Sacha Hickinbotham, Y4 ‘Immaterial Landscapes’. This installation explores the material and immaterial phenomenological qualities of scaled Swiss-landscape infrastructures. A series of suspended cast vessels produce a slow drip of water to replicate Swiss hydroelectric dam infrastructures. Subsequent models of light, sound and heat are activated through the impacting force of falling water.

11.14 Theo Jones, Y4 ‘Unfolding a home of diplomatic containment’. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange lived inside the Ecuadorian embassy for six years. Leaked documents suggest that Ecuador considered transporting Assange out of the embassy in a diplomatic bag. In this project, the embassy is folded down inside the diplomat’s jacket, secretly moving Assange and the territory of Ecuador that protected him.

11.15 Maxime Willing, Y4 ‘Woven Futures’. This project proposes a holistic environment designed to provide the people of Geneva with a building that changes in appearance with time and use. The architecture takes on the blue from the dyeing of textiles in the same manner that an artisan’s hands change with work. Ornamentation developed from the Swiss vernacular process of ‘sgraffito’ is used as the vehicle for this layering of colour.

11.16 Rachel Swetnam, Y4 ‘Glasmuseum’. A process collage following a series of light studies testing the qualities of coloured light for a glassblowing museum and studio in Lucerne, Switzerland.

11.17 Liam Merrigan, Y4 ‘Neulandsgemeindeplatz’.

For centuries, the Appenzeller community in northern Switzerland has resisted influence from beyond their territory, fostering a unique identity rooted in political debate, religion and their connection to the landscape. This project examines the past and future of this isolated culture, drawing on traditional costume and craft to convey architectural ideas. The scheme is a monument of statues, guesthouses, relics and festival spaces built around a new parliament square.

Year 4

George Bradford-Smith, Andrew Chard, Wei-Kai Chu, Oliver Colman, Stefan Florescu, Paul Humphries, Douglas Miller, Naomi Rubbra Nicholas Salthouse

Year 5

Bethany Bird, Laurence Blackwell-Thale, Tom Budd, Emma Colthurst, Patrick Horne, Alexander Liew, Joe Roberts, Eleanor Sampson

Many thanks to our Design Realisation tutor Rhys Cannon, and to Stephen Foster, for their support

Thank you to our critics: Roberto Botazzi, Kyle Buchanan, Margaret Bursa, Edward Denison, Holly Lewis, Aisling O’Carroll, Luke Pearson, Emanuela Tiley, Tim Waterman

The ‘National Reserve’ brief interprets the landscape of margins and architectures ‘on the edge’, to expose overlooked stories of life and data. Spatial opportunities within the often-misunderstood interlacing of unplanned and planned, designated and uncontrolled urban and rural landscapes are exposed through interrelated landscape scenarios. The green belt – which provides a curated buffer zone, an idealistic hinterland between city, suburb and ‘satellite’ village – is a perpetually threatened (spatial) concept and (legislative) landscape. The public perception of the green belt as countryside is at odds with the reality of this landscape. Much of it is classed as ‘neglected’, with derelict buildings, rubbish, electricity pylons and other blots on the landscape. Less than half is green and much of that is monoculture farmland, spending whole seasons beige or brown.

The original and enduring role of the green belt is to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently ‘open’. However, in the UK, no aims are set for acceptable land uses and no indication is given as to their preferred form beyond a general concern that green belts should retain their ‘openness’. This vaguely defined requirement is inevitably renewed and transformed as our territorial requirements change to keep up with the demands and desires of the 21st century – be they local, national, technical, cultural or social – and by consequence, provides an essential landscape for defining the transforming prospect of Britishness itself.

Occupying the ‘Terrain Vague’

Green belts were never explicitly provided for nature conservation or to preserve the appearance of the UK’s rural idyll, but rather to produce a peri-urban edge to the city in the form of a national reserve: land squirreled away, not left to squirrels.

‘Open’ also doesn’t necessarily mean natural, accessible or absent from development. In fact, much of its area could be described as Terrain Vague, a term coined by Ignasi de Sola-Morales to suggest a spatial phenomenon that, contrary to the legislative designations that surround it, defies categorisation – an in-between ‘ambiguous space’. Its unexpected lack of definition, and appearance of being left to its own devices, permits a kind of freedom from the palimpsest of previous lives and the promise of future ones. This is the territory where our architectural imaginations can thrive.

Alongside our interest in the UK’s legislative landscapes, we also delved into international territories (Palm Springs and Los Angeles) where parallel stories of urban speculation offered alternative narratives on architecture’s capricious relationship with landscape.

Fig. 11.1 Eleanor Sampson Y5, ‘The Fourth Estate’. Sited within the once idealised suburban state of ‘Metro-Land’, North-West London, this project is a testbed for a new template of British housing. The multi-layered landscape seeks to emulate the convenience and contradictions of the suburbs whilst updating the semi-detached housing typology to the needs of today. The urban-to-rural gradient influences both the cultivation of the landscape and the uses of the buildings rooted within it.

Fig. 11.2 Joe Roberts Y5, ‘The Post-Growth Community’. What would it mean for the city to be accountable for all the elements that sustain it, not as an abstraction, but as a fully bounded system obliged to take care of itself? The Post-Growth Community’s ecological footprint is correlative with its political boundary. Fig. 11.3 Tom Budd Y5, ‘Bigger Than a Hamlet, Smaller

Than a Town’. Chobford-Barrow challenges the notion of creating new garden village communities from scratch. By using the motorway as the economic starting point for a settlement, a new ‘service station village’ typology is proposed. Here the collision of multiple scales of pace are mediated through the fusion of the village green, high street and motorway service station. Fig. 11.4 Patrick Horne Y5, ‘How Do You Feel?’. This project explores virtual environments as a platform to test the psychological effects of architecture. Through five experimental buildings, it examines which forms of useful data we can extract from participants in virtual environments and speculates on how this data might knowingly inform architectural design. Each building is shown before and after revision, highlighting the changes enacted through each consultation process.

Fig. 11.5 Bethany Bird Y5, ‘Ojai Wildfire Response Centre, California’. Purpose-made materials such as Nomex and Kevlar are developed to aid firemen and women to tackle fires. The project applies these modern firefighting technologies in tandem with dressmaking techniques, to explore fire safety within architecture. Fig.11.6 Wei-Kai Chu Y4, ‘Future P[Reserve] Archive’. The governmental act of releasing green belt land for housing development inspires the process of digitally recording London’s green belt landscapes. Fig. 11.7 Oliver Colman Y4, ‘Occupying the Green Belt’. A series of dynamic mechanical models flip the National Planning Policy Framework to question the occupation of green belt land. Each model explores the protected land around Epping, Essex through augmented landscapes, faux historical façades and illusionary

interventions. Fig. 11.8 Andrew Chard Y4, ‘Filtered Oasis’. California’s accidental Salton Sea once provided tourism and wealth to this desert region. Now receding, the shores flood the surrounding communities in toxic dust. This elementary school provides a filtered safe haven to the community’s most vulnerable inhabitants. Fig. 11.9 Douglas Miller Y4, ‘Mapped’. Exploring the divide between the map and the world it depicts, this project investigates the manipulations and absurdities that are thrown up by comparing the bleeding-edge technology of mapping and navigation to its two-dimensional predecessor. Using modern mapping technologies such as LIDAR in conjunction with drawing, a new graphical language is built.

Fig. 11.10 Paul Humphries Y4, ‘The Letchworth Achievement’. This new town hall celebrates the garden city in the hope of it thriving as the blueprint for new town development in response to the current housing crisis. Fig. 11.11 Nicholas Salthouse Y4, ‘An Architecture of Uncertainty’. In politically uncertain times the building offers extraterritorial amnesty from Theresa May’s ‘Hostile Environment’. The architecture reconfigures itself with the tides, metaphorically representative of this political ebb and flow, allowing variable programmatic flexibility within an otherwise open-plan space; its configuration at any one time graphically embossed in the façade. Fig. 11.12 Stefan Florescu Y4, ‘Under the Grid’. An Apiculture Centre, where bees live and produce honey all year long, provides a new building typology for the hazardous open land under power lines in the green

belt. The building uses its geometry and materiality to shield its occupants from electromagnetic radiation. Fig. 11.13 George Bradford-Smith Y4, ‘Dirty Greenbelt’. Heathrow Airport has the highest levels of pollution within the green belt, exceeding EU limits. This project captures, diffuses and reconfigures air pollutants and aircraft noise, transforming these into structural movements. Hotel guests’ negative perceptions of pollution are subverted through the hotel experience. Fig. 11.14 Alexander Liew Y5, ‘The British Overseas Territories Exposition’. The exposition is designed to bring the global patchwork of 14 intriguing communities and territories together into one site, in order to highlight the diverse range of attributes in their landscapes and communities, whilst re-linking them to Britain.

Fig. 11.15 Naomi Rubbra Y4, ‘New Citizens’ House’. This project looks at providing a space for communal gathering, whilst supplying much-needed services to the boating community along the Lee Navigation. The work evolved from a 1:1 installation on Tottenham Marshes exploring structural mobility, into an architectural response to the temporality of boating lifestyle, water reuse and habitat restoration.

Fig. 11.17 Laurence Blackwell-Thale Y5, ‘Sublime Landscape Generator’. Foothills, fingers of lakes, shoulders of mountains: the body-landscape metaphor is the basis for a trans-scalar production of new landscape iterations. The Sublime Landscape Generator uses aerial photography techniques to produce stereoscopic visions of cartographically quantified, sublime experiences. 11.16

Fig. 11.16 Emma Colthurst Y5, ‘The Circumambulation of Cranham’ explores the richer narratives between the community of Cranham and their collective landscape: a suburbanised village on the outskirts of London. The future civic functions of the village relocate along the ancient parish boundary on 26 alphabetised boundary markers. Each civic function harbours a secondary political function, for example

uniting the pub (A) with Havering Political Surgery and the butcher’s shop (C) with Adult Welfare. The residents and local council collectively embark on this circumambulation to further discover and celebrate the community of Cranham.

Year 4

Bethany Bird, Laurence Blackwell-Thale, Emma Colthurst, Patrick Horne, Lex Liew, Joe Roberts, Ellie Sampson

Year 5

Alexander Chapman, Chris Delahunt, Johanna Just, Anthony Ko, Ness Lafoy, Milo de Luca, Agostino Nickl

Thanks to our Design Realisation tutor Rhys Cannon

Thank you to:

Steven Foster Engineers, Ali Shaw at Max Fordham and to our critics Brendan Cormier, Edward Denison, Stephen Gage, Dan Hill, Joseph Grima, Rory Hyde, Zoe Laughlin, Holly Lewis, Peter Liversidge, Luke Pearson, Tania Sengupta, Tomas Stokke, Gwen Webber, Patrick Weber, Elly Ward Morris

This year, we dreamt of future pasts. The natural tensions and antithetical relationships characterised by the struggle between preservation and progress provide lessons, opportunities and limits for the continuum of landscape and urban histories and, more importantly, determine their emerging futures.

The zenith of preservation is the UNESCO World Heritage List for natural, built and cultural landscapes, cities and monuments. It seeks to record and preserve cities and landscapes, making them, to an extent, 'future-proof' – and at the same time inadvertently fossilised in their current states. The UNESCO list is diverse and wide-ranging, and includes Easter Island, 17 works by Le Corbusier, the Statue of Liberty and the industrial ruins of an Argentinian Fray Bentos Factory. Listing provides protection through international law, however, it has also been described as a lethal weapon deployed in the act of preservation’s crimes against cities.

The Venetian Lagoon (the journey’s end of our European trip this year) is striving to maintain its inclusion on the World Heritage List, despite a developing battle between tourism and culture. The city hosts over 600 cruise ships and 20 million visitors per year, which, as well as pumping tourist money into the city, also endangers its physical fabric and cultural integrity under the terms of its UNESCO listing.

Could the construction of replica cities and pseudo-landscapes, relocated across the world, be an alternative to the museumification of listed cities such as Venice? These embodiments of Umberto Eco’s concept of ‘Uffiziland’, such as the unfeasibly blue and chlorinated Grand Canal at the Venetian hotel-casino in Las Vegas, are designed to improve on the touristic rather than the authentic ‘experience’.

The opportunity for the retelling and recasting of histories through copies, and their significance in preservation, is given credence via museum collections such as the Cast Courts at the V&A, which contain collections of historic plaster and wax replicas of monumental sculptural and architectural fragments collected in the 19th century. Their collection also reveals the contemporary role of copies in the preservation of cultural artifacts and global heritage threatened by war, climate change and societal pressures. The emergence of new technologies such as 3D scanning and digital printing mean that copies can now be ‘dematerialised’ to the hard-drive rather than to the museum gallery. One can imagine a future reprinting, like a Jurassic Park style recreation of cultural artifacts, cut off from their context and meaning, reanimated nowhere and everywhere, even at an urban or landscape scale.

In attempt to recast ‘Wonderland’ and to create instant histories, inspiration for our year’s work included UNESCO’s list of intangible Cultural and World Heritage, model villages, alternative preservation manifestos, fakery, architectural graveyards, demonstration landscapes, cultural migration, monuments and their doppelgängers.

Fig. 11.1 Agostino Nickl Y5, ‘Low-res City’. Using photogrammetric data, Hamburg is compressed into 80 specimens mined from across the city. These low-res samples become true representatives of the urban fabric containing extracts of fields, the Autobahn, a brutalist warehouse, a church and an airplane, amongst others. They serve as testbeds for newly developed and existing fabrication techniques. Fig. 11.2 Ellie Sampson Y4, ‘The Torcello Typology Repository’. Composite drawing. An elevated island in the marshy landscape towards the north of the lagoon, the repository uses channelled water, limestone-lined vessels and purposefully eroding walls to recreate and intensify the processes attacking Venice’s unique infrastructure.

Fig. 11.3 Laurence Blackwell-Thale Y4, ‘Miniatur Wunderland