ancient amazon

arqueologia no entorno | an arqueologia no entorno an archaeology in the surroundings in the

arqueologia no entorno | an arqueologia no entorno an archaeology in the surroundings in the

A Amazônia tornou-se o símbolo verde da esperança de um mundo em constante transformação, e busca-se, através da evolução econômica, científica e tecnológica, contribuir para preservar e divulgar uma das regiões mais importantes de nosso planeta.

É por isso que, no momento em que todos os olhares se voltam para a Amazônia, torna-se fundamental a edição deste livro. Ele estabelece o elo fundamental que liga épocas e culturas no tempo e na história, lembrando-nos de que só poderemos compreender o presente se nos reportarmos ao passado e só poderemos projetar o futuro se construirmos o presente. Em Amazônia antiga, a arte e a ciência estão interligadas, retratando a integração harmônica e atemporal da vida humana.

O fotógrafo Maurício de Paiva e a jornalista Mônica Trindade Canejo passaram anos pesquisando e captando belas imagens que pudessem mostrar a interação e a preservação dos elementos pré-históricos encontrados na Amazônia com a dinâmica atual da vida cotidiana, os sítios arqueológicos e seu entorno: os caboclos, os rios e as matas. O resultado, como vocês poderão comprovar, é excepcional.

Assim sendo, a Fosfertil – uma empresa que atua segundo os mais modernos princípios de sustentabilidade e responsabilidade social – sente-se honrada em participar da edição de Amazônia antiga

Vital Jorge Lopes presidenteThe Amazon has become the green symbol of hope for a constantly changing world, one that seeks through economic, scientific and technological evolution to contribute to preserve and spread information about one of our planet’s most important regions.

This is why this book’s release becomes fundamental at a moment when everybody’s eyes are turned to the Amazon. It establishes the fundamental link in time and history between epochs and cultures, reminding us that we can only understand the present with the past as a reference, and that we can only project the future if we build the present. In Ancient Amazon, art and science are intertwined, portraying the harmonic and timeless integration of human life.

Photographer Maurício de Paiva and journalist Mônica Trindade Canejo have spent years researching and capturing beautiful images that could show the preservation and the interaction of prehistoric elements found in the Amazon with the current workings of everyday life, the archaeological sites and their surroundings: the Caboclos, the rivers and the forest. The result, as you will be able to attest, is outstanding.

Thus, Fosfertil – a company that works within the most modern principles of sustainability and social responsibility – feels honored in participating in the publishing of Ancient Amazon

Vital Jorge Lopes President

Vital Jorge Lopes President

www.fosfertil.com.br

arqueologia no entorno | an archaeology in the surroundings

Estatueta antropomorfa da cultura tapajônica, região de Santarém, Estatueta da cultura de Santarém, Pará Idade desconhecida, provavelmente início do segundo milênio Pará. Idade desconhecida, início do milênio d C Acervo do MAE USP d. C. Acervo do MAE-USP

Anthropomorphic statuette of the Tapajós culture, Santarém region, Pará

Anthropomorphic statuette of the Tapajós culture, Santarém region, Pará. Age unknown, probably the early second millennium AD Collection of unknown, the second millennium AD. Collection of the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, the of São Paulo’s Museum of and Ethnography, MAE USP MAE-USP

Dedico este livro à presença de meus filhos, Enrique e Helena; à memória de meu pai, Nelson, que, junto com meu avô Jorge, despertou na infância de Dedico este livro à presença de meus filhos, e Helena; à memória de meu Nelson, que, com meu avô na minhas mãos o tato para a página impressa e o apreço pela cor; ao padrinho Eduardo Góes Neves; a Daniel Brasil, o menino que primeiro me recebeu em minhas mãos o tato para a e o apreço cor; ao Eduardo Góes Neves; a Daniel Brasil, o menino que me em Vila Tessalônica, na ilha de Marajó, mostrando me o fragmento cerâmico de “índio deitado” que encontrara à beira do rio Araramã; e a Mônica Trindade Vila Tessalônica, na ilha de mostrando-me o cerâmico de “índio deitado” que encontrara à beira do rio Araramã; e a Mônica Trindade Canejo, profundamente esperançosa Com carinho e respeito por todas as pessoas que fazem a Amazônia Hoje, ontem e nos últimos 11 200 anos profundamente esperançosa. Com carinho e respeito por todas as pessoas que fazem a Amazônia. Hoje, ontem e nos últimos 11 200 anos.

I dedicate this book to the presence of my children, Enrique and Helena; to the memory of my father, Nelson, who along with my grandfather Jorge I dedicate this book to the presence of my children, and Helena; to the memory of my father, Nelson, who with my awoke my hands’ childhood to the feel of a printed page and the appreciation of color; to my mentor awoke my hands’ childhood to the feel of a page and the of color; to my mentor Eduardo Góes Neves; to Daniel Brasil, the boy Eduardo Góes Neves; to Daniel Brasil, the who first received me at Vila Tessalônica, on Marajó Island, showing me the ceramic fragment of a ‘lying Indian’ he had found on the bank of the who first received me at Vila Tessalônica, on Island, me the ceramic of a Indian’ he had found on Araramã River; and to a deeply hopeful Mônica Trindade Canejo Araramã River; and to a Mônica Trindade Canejo. With fondness and respect for all the people who make the Amazon what it is With fondness and respect for all the who make the Amazon what it is. Today, yesterday, and in the last 11,200 years and in the last 11,200 years.

LUZ NO

Sabedoria e instinto milenar, a imagem pode ser considerada a técnica mais antiga de transmitir ensinamentos entre gerações. Desde sempre, a história do planeta e de seus habitantes é contada e representada pela interpretação dos símbolos-signos das imagens de suas obras. A imagem desempenha o papel de mais poderoso agente na capacidade de instigar a memória e polinizar a capacidade de raciocinar e sentir. Ela integraliza o passado e o futuro no presente. Congela e classifica os momentos dispondo as ferramentas que precisamos usar para o conhecimento de nossa própria história e o desfrute sensorial e intelectual.

A gramática e a ética da imagem e do ato de ver nos permitem conhecer novos códigos visuais a cada geração de fotógrafos, que alteram e ampliam nossas noções sobre o que deve ser visto e o que temos direito de poder observar. O grande mosaico visual criado a partir de 1839, quando se começou a fotografar tudo e todos, nos oferece a sensação de ter o mundo nas mãos com essa antologia universal de visões fotográficas. Imagens que, como acredita Susan Sontag, vão iluminar a caverna de Platão e seus moradores na busca pela verdade e compreensão da realidade.

Amazônia antiga arqueologia no entorno traz uma dessas coleções de imagens que vêm educando nossos sentidos através dos tempos. Maurício de Paiva, fotojornalista caçador de imagens, inconformado-curioso-visceral, nos conduz com sua inquietude pela dimensão arqueológica, o estudo da história da humanidade.

Fronteira visual raramente abordada, a ciência arqueológica, nesta obra, se discute da inédita perspectiva das planícies amazônicas. Somam-se a fotografia e seu impacto emocional para penetrar pelas portas de nossa percepção transcendental. Os fragmentos de história nestas imagens são representados em prateleiras com cacos de civilizações, sobrepostos cronologicamente, decodificando seus ensinamentos. São olhares e gestos dos habitantes desta Terra Prometida, escolhida ao acaso divino, dentro da imensidão da floresta e nas mesmas coordenadas geográficas das anteriores, onde foram se sucedendo milagrosamente, repetindo os usos e costumes nos mesmos sítios dos viventes do terceiro milênio, que aqui nos ajudam a perceber com a clareza de um raio – ou a luz de um flash – milhares de anos numa imagem.

Esta viagem pelo saber, suave navegar através do tempo cósmico, nos transporta envoltos na ambiguidade da densa leveza das formas e da profundidade do aquarelismo que

o panorama amazônico nos presenteia. São molduras ideais para rostos semelhantes e gostos iguais, de seres que repetem gestos, hábitos e afazeres, sonhos e febres e que, depois de milhões de dias nos mesmos lugares, usam a argila da mesma água e da mesma terra, nesses pontos essenciais do coração do planeta.

Guiado por sua intuição (iluminada pelo conhecimento científico de seus companheiros de jornada), Maurício reconhece e confronta pelos olhares que povoam suas imagens as muitas faces da mesma história dentro do tempo infinito. Estampadas no barro ou coladas nos firmamentos e águas monumentais da Amazônia, são como efígies de moedas de um milenar tesouro que Deus deixou para ser entendido e reconhecido por quem ali estiver vivendo. Ensinamento preciso e fluente, aqui bem debaixo de nossos pés, ao alcance de nossos sentidos e saberes.

Extrativismo espiritual e social, os fragmentos visuais dispostos pela história vão formando um mosaico de sensações transcendentais, causadas e captadas pela visão do autor. Foram produzidas segundo os mais tradicionais e comprometidos padrões de documentação fotoantropológica. Respeitam os princípios do melhor fotojornalismo e impactam e renovam fortemente nossos paradigmas imagéticos. Essa colagem cósmica da natureza perturba o senso terreno e presente, pois extrapola o registro científico e vai além do relatório quando toca o emocional e mágico, invadindo nosso subconsciente sem remorso, pecado ou perdão. Envolvendo e transportando nossos sentidos e espírito para que possamos compreender nossa própria existência, Amazônia antiga – arqueologia no entorno , enfim, inaugura uma nova dimensão iconográfica, a da próxima geração de livros de fotografia e ciência produzidos no Brasil e em língua portuguesa. Uma lindíssima história plena de descobertas científicas e prazeres visuais, explorada com astúcia respeitosa, rigor estético e consistência informativa. Um tempo precioso de genuíno prazer intelectual e sensorial.

Julho de 2009

Fotojornalista e professor de fotografia, publica desde 1969. Com passagens pelos mais influentes veículos de imprensa brasileiros, fundou a agência Angular. É seguidor de Robert Capa.

Images, being wisdom and millennia-old instinct, can be considered the oldest technique for transmitting teachings between generations. Since time immemorial, the history of the planet and its inhabitants has been told and represented by the interpretation of the symbols/signs of their works’ images. Images play the role of the most powerful agent capable of stimulating memory and pollinating the ability to reason and feel. They sum up the past and the future into the present. They freeze and classify the moments by using the tools we need for gathering the knowledge of our own history and for our sensory and intellectual enjoyment.

The grammar and ethics of images and of the act of seeing allow us to learn new visual codes in each new generation of photographers, who change and broaden our notions about what must be seen and what we are entitled to observe. The great visual mosaic created in 1839, when people started photographing everything and everyone, offers us the feeling of having the world in our hands with that universal anthology of photographic visions. Images which, as Susan Sontag believes, are going to lighten Plato’s cave and its dwellers in their search for truth and understanding of reality.

Ancient Amazon – an Archaeology in the Surroundings shows one of those collections of images which have been educating our senses throughout time. Maurício de Paiva, an imagehunting photographic journalist, a nonconformist-curious-visceral person, leads us with his disquiet through the archaeological dimension, the study of mankind’s history.

A rarely approached visual frontier, in this work archaeological science is discussed from the new perspective of the Amazon plains. Photography and its emotional impact are joined to enter through the doors of our transcendental perception. The fragments of history in these images are represented in racks with shards of civilizations, chronologically superposed, decoding their teachings. They are looks and gestures from this Promised Land, chosen by a divine whim, within the vastness of the forest and in the same geographic coordinates as those of the previous ones, where they miraculously kept succeeding each other, repeating practices and customs in the same sites of people of the third millennium, who here help us to perceive with the clarity of a lightning bolt – or the light of a flashlamp – thousands of years in an image.

This journey through knowledge, this smooth sailing through cosmic time, carries us wrapped in the ambiguity of the dense lightness of shapes and in the depth of the

watercolor gift of the Amazon panorama. The images are ideal frames for similar faces and equal tastes of beings who repeat gestures, habits and chores, dreams and fevers, and after millions of days at the same places they use the clay from the same water and the same earth in those essential spots at the heart of the planet.

Guided by his intuition (enlightened by the scientific knowledge of his travel companions), Maurício recognizes and confronts the same history’s many faces in endless time through the looks that populate his images. Imprinted on clay or fixed to the monumental skies and waters of the Amazon, they are like coin effigies from a treasure of thousands of years that God left to be understood and recognized by whoever happens to be living there. Precise and fluent knowledge, right here under our feet, at the reach of our senses and information.

A form of spiritual and social collecting, the visual fragments laid out by history form a mosaic of transcendental sensations which the author’s vision provoke and capture. They were produced using the most traditional and committed standards of photoanthropological documentation. They respect the principles of the best photographic journalism and strongly impact and renew our image paradigms. This cosmic collage of nature disturbs the earthly and present sense, for it goes beyond scientific records and reports when it touches the emotional and the magic, invading our subconsciousness without regret, sin or forgiveness. Involving and carrying our senses and spirit, so that we can understand our own existence, in short Ancient Amazon – an Archaeology in the Surroundings opens up a new iconographic dimension, that of the next generation of photographic and scientific books produced in Brazil, in the Portuguese language. An exceedingly beautiful story, full of scientific discoveries and visual pleasures, explored with respectful astuteness, aesthetic rigor and informative consistency. A precious time of genuine intellectual and sensory pleasure. July 2009

A photojournalist and photography professor, Bittar has been published since 1969. Having worked for the most influential organizations in the Brazilian press, he founded Angular, a photo agency. He is a follower of Robert Capa.

R e s e r v a d o s t o d o s o s d i r e i t o s d e s t a o b r a P r o i b i d a t o d a e q u a l q u e r Reservados todos os direitos desta obra. Proibida toda e qualquer reprodução desta edição por qualquer meio ou forma seja ela eletrônica desta por meio ou forma, ela eletrônica ou mecânica, seja fotocópia, gravação ou qualquer meio de reprodução, ou mecânica, ou meio de sem permissão expressa do editor / expressa do editor. / All rights reserved Without the express All reserved. Without the express permission of the publishers, any and all reproduction of this edition in of the any and all of this edition in any manner or form either electronic or mechanical either photocopy any manner or form, either electronic or mechanical, either photocopy, recording, or any other means of reproduction, is strictly forbidden or any other means of is forbidden.

Urna funerária da tradição policrômica dos marajoaras, que Urna funerária da dos que ocuparam a a ilha de Marajó entre os anos 400 e 1350 d C Acervo do Museu do Forte ilha de Marajó entre os anos 400 e 1350 d. C. Acervo do Museu do Forte do Presépio, Belém do Pará do Belém do Pará F u n e r a r y u r n f r o m t h e p o l y c h r o m a t i c t r a d i t i o n o f t h e M a r a j o a r a , w h o Funerary urn from the polychromatic tradition of the Marajoara, who p o p u l a t e d M a r a j ó I s l a n d b e t w e e n 4 0 0 a n d 1 3 5 0 A D C o l l e c t i o n o f t h e populated Marajó Island between 400 and 1350 AD. Collection of the Museu do Forte do Presépio, Belém, Pará Museu do Forte do Pará

Uma janela da mente que floresce. Um sol do equador. Um mês de viagem. Um misterioso igarapé e uma pedra quase lascada. Visão-declive de túnel de floresta fechada, no sábado de inverso amazônico, inverno. Uma súbita manhã gloriosa da qual agora, relembrando melhor, consigo fazer um desenho estratigráfico. O Retiro do Padre fora um sítio que me fez debruçar numa espécie de viagem xamânica, lá no Amapá do solstício. Explico. Mordi um tipo de cebola-brava – eu pensei ser um rabanete! – que veio debaixo da terra arqueológica com raiz que parecia de mandioca, retirada por uma pá de escavadeira dinossáurica, nas escavações com a equipe de pesquisa. Chamo hoje de “movimentos circulares e pensamentos cíclicos” o cerimonial que fiz quando andei em redor de minha máquina fotográfica, um entorpecimento leve, mas distinto, sim, de sensações artificiais. Desci por uma estrada deserta acerca das colinas aclives que os pesquisadores atestam ser ocupações pré-coloniais, aproximadamente da época de Cristo; eu não sabia direito se fugia do calor ou projetava frescor para perto de algum espelho d’água. Talvez apenas buscasse respiro solitário. A lucidez de pensar nos elementos que compunham ali a realidade em que eu era menos protagonista – uma ironia fotogênica – vinha por centelha, por fagulha apenas. No geral, agia quase por instinto, fugidio, para fortalecer-me. Pois, na cegueira, larguei a câmera no centro da pedra aonde cheguei, como se ilhada, e andei em torno dela a passos de soldado, tendo reflexões cíclicas. Por exemplo, como refazer-me em encontrar melhores cenas para aquela pauta ou a próxima vida em São Paulo, quando voltasse. Enxugava o suor com as costas da mão. Estavam obsessivos aqueles pensares. Dali surgiu de soslaio a mira de um urubu, que voava aberto num trajeto triangular sobre mim, reticente e seguro, como um guardião de rapina. Símbolo. Estranhei que, embora até tentasse, eu não o assustava; ao contrário, ele pululava de um galho preciso a outro, outra sobra de árvore em que ficava clara a noção de uma geometria no céu acima. Ele protegia um tempo, talvez o meu, sagrado. Então, em meio ao capricho ancestral do calor úmido, a câmera era epicentro (a mim era profana tradição, apego e prazer), eu a resguardando em círculo, a pedra que entornava e até violava tudo. Nisto me estendi de pescoço, a olhar na água uma arraia-malhada. Ela, pajé, levava consigo pequenos girinos negros, que confundi com seu próprio desenho de malha-corpo. Perplexos, eles acompanhavam sobrepondo seu nadar na beira do megálito, polido. Serenei vendo isso de pé. Arraias de rio, em igarapés, são esporas triangulares? Sol, sombra, seres vivos em trânsito; trêmula profundidade mental e buscas visuais, a renúncia do próprio equipamento à força central. O que eu, homem-olho, intuía? O que antecipava

descobrir em torpor tropical? Com o que me identificava? Depois, à tarde cedo, após ter braçado no rio, aturdido me percebia na presença das pessoas; relendo, descrevendo coisas como uma suposta boca seca, um formigamento no braço e a forma de uma nuvem que se assemelhava pão. Só desculpas. Foi para tornar-me mais racional, para vomitar. Tensão ou medo da percepção exacerbada, por uma cebola remota e natural.

Há controvérsias sobre isso tudo como contraluz desvelada. Imagética díspar que me desperta inquietação e aproximação em desmembrar. Passado. Me parece tranquilo pensar que a mágica arqueologia amazônica é como prosa, narra a loucura de sempre a quem tentei transcender, àqueles que outrora habitaram cada sítio, o ribeirinho e a “ciência”, mais perto… Há a ecologia e o capital no caldo. Acho que não consegui totalmente dar feitio de imagem, correlacionar os seres de antes e de hoje neste ensaio cor de fotogramas. Como dar aparência ao intrínseco numa foto congelada? Como catapulta, o não-óbvio emergiu da noção da ignorância sobre o nosso passado e a “pré história”. O óbvio surgiu como espelho, ver o morador amazônida. Este projeto, ainda que se conforme mais adentro da temática acadêmica, é o do desconhecimento e o do desbravamento – este por nós construído! Unir fotografia e arqueologia ainda é incompletude, mas também equivalência! Fez-me outro, fez-me falar mais de mim, ver um norte. Nos temas fotográficos, quase sempre busco coesão – achar paralelos e conexões – em ideias a princípio opostas (caminho incrível, todavia impalpável), o sertão e o mar, a floresta e a urbanidade, o arcaico e o moderno, subjetividades. Documentando sempre nos limites – e com filmes! – para imergir na etnologia e na “antropologia visual”. Indo além do imaginário sobre o passado no recorte do presente na Amazônia, indo além da angústia autoral no mundo da visualidade. O melhor quem me disse foi o caboclo Graça, um senhor do Retiro do Padre, aventando: “Essa cebola parece das que os búfalos ruminavam no pasto, no tempo que era fazenda aí pra fora. Alguns tanto que morriam, como os nossos antigos”.

O livro não sepulta nada. Sentencia tampouco. Quiçá dá espaço a essa gente tradicional na Amazônia e a seus depoimentos propícios, ocultos; à criatividade no vínculo com a memória que os vestígios supõem. Eles lidam com a natureza das coisas de cabeça, sempre singulares.

Vê-los exercita e traz o alheio do tempo.

Há cinco anos, Maurício de Paiva

Under the equator

A window of the mind blooming. An equatorial sun. A month’s travel. A mysterious Amazon stream and a nearly chipped stone. A downward vision of a tunnel of thick forest on an Amazon winter Saturday. A sudden glorious morning of which, recalling it better now, I can make a stratigraphic drawing. Retiro do Padre was a site that made me stoop on some shamanic journey, up there in Amapá, the solstice land. Let me explain. I bit a kind of wild onion – I had thought it was a radish! – that came under the archaeological earth, with a root like one of manioc, dug out by the mechanical shovel of a dinosaur-like earth-mover, during the excavations with the research team. Now I call the ceremony I made walking around my camera “circular movements and cyclic thoughts,” a torpor that was light but definitely distinct, made from artificial sensations. I went down a deserted road by the sloping hills that researchers attest to be pre-colonial dwellings, from circa the time Christ lived; I did not know for sure if I was just escaping the heat looking for some freshness near some water mirror. Maybe I was just looking for some solitary respite. Thinking of the elements there that made up a reality in which I was less of a part – a photogenic irony – was something that came only as a flicker, a spark. Overall, I acted almost by instinct, dodgingly, to strengthen myself. For, in my blindness, I left the camera at the center of the stone where I had arrived, as if on an island, and walked around it with martial steps, having cyclic reflections. For example, on how to recover to find better scenes for that assignment or how my upcoming life in São Paulo would be when I went back. I wiped the sweat with the back of my hands. Those thoughts were obsessive. Then appeared the surreptitious sight of a vulture, which flew open in a triangular path over me, reticent and secure, like a guardian of prey. A symbol. I found it strange that, though I even tried it, I did not frighten the bird; on the contrary, it jumped from one precise branch to another, a tree leftover which made clear the notion of a geometry in the sky above. The vulture protected a time, maybe my time, that was sacred. Then, amid the ancestral fancy of the humid heat, the camera was the epicenter (to me it was a profane tradition, fondness and pleasure), me protecting it in a circle, on the stone that spilled and even violated everything. That was when I stretched my neck, looking to a mottled ray in the water. As if it were a shaman, it carried along small black tadpoles, which I mistook for its own mottled body pattern. The perplexed tadpoles followed the ray superposing their swimming to the edge of the polished megalith. I got calmer standing and seeing that. Are river rays triangular spurs in Amazon streams? Sun, shade, living beings in transit; trembling mental depth and visual searches, the surrender of one’s own kit to the central force. What did I, the man-eye, infer? What did I anticipate to discover in a tropical torpor? What did I identify myself with? Later, early in the afternoon,

after having swum in the river, I found myself astonished in the presence of people; I was re-reading and describing things such as a supposed dry mouth, a tingling in the arm and the shape of a cloud that looked like a bread roll. Just excuses. That was intended for me to become more rational, to throw up. Tension or fear of a perception that was exacerbated by a remote and natural onion.

There are controversies about all of this being some sleep-deprived backlit imagery. An uneven imagery that causes in me an uneasiness and a nearness to splitting apart. Past. It seems easy for me to think that the magical Amazon archaeology is like prose, that it narrates the usual madness that I tried to transcend to those who in other times inhabited every site, the riverbank people and “science” made closer… In the same brew, there is ecology and capital. I think I have not totally succeeded in creating the look of an image, to relate the beings from before and today in this photogram-colored essay. How to give an appearance to the intrinsic in a frozen photograph? Like a catapult, the non-obvious emerged from the notion of ignorance about our past and “prehistory.” The obvious appeared as a mirror, seeing the Amazon dweller. This project, although fitting more into the academic theme realm, is one of ignorance and discovery – the latter accomplished by us! To unite photography and archaeology still means incompleteness, but it also means equivalence! It has made another kind of man of me, it has made me talk more about myself, it has made me see a direction. In photographic themes, I almost always look for cohesion – to find parallels and connections –in ideas that in principle are opposite (an incredible path, however impalpable): the hinterland and the sea, the forest and urban life, the archaic and the modern. Subjectivities. Always documenting at the edge – and with photographic film! – to immerse into the ethnology and the “visual anthropology.” Going beyond the lore about the past in the background of the Amazon’s present, going beyond author’s angst in the world of the visual. The best thing was said to me by Graça, a Caboclo (mestizo) from Retiro do Padre, conjecturing, “That onion looks like one of those which water buffalos ruminated in the grazing field, at the time when there was a farm out there. Some ate it so much that they died, just like our ancient people.”

This book does not bury anything. It does not pontificate either. Perhaps it gives some space to those traditional people in the Amazon and their propitious, occult accounts; to the creativity in the links to memory hinted by the vestiges. They deal by heart with the nature of things that are always unique.

To see them exercises and brings on the alienation of time.

For five years now, Maurício de Paiva

Menino

segura tampa de urna da fase guarita. Ruínas de Paricatuba, Iranduba, Amazonas A boy holds an urn lid from the Guarita period. Paricatuba ruins, Iranduba, Amazonas

segura tampa de urna da fase guarita. Ruínas de Paricatuba, Iranduba, Amazonas A boy holds an urn lid from the Guarita period. Paricatuba ruins, Iranduba, Amazonas

Arqueólogos mantêm relação especial com seu objeto de estudo: precisam destruí-lo para estudá-lo. Uma escavação arqueológica nada mais é que a destruição de sítios onde vestígios se encontram depositados há centenas, milhares ou mesmo milhões de anos. Essa destruição, por certo, é feita com métodos próprios, desenvolvidos ao longo dos últimos duzentos anos, e é a utilização correta desses métodos o que separa os arqueólogos dos saqueadores de sítios, ou huaqueros, como são conhecidos em muitos países latino-americanos. A necessidade de aplicar métodos de campo faz também que arqueólogos normalmente andem em bandos. A imagem consagrada que associa a arqueologia de campo a uma prática solitária é falsa. No mais das vezes, a escavação de sítios requer a mobilização de grupos numerosos, que podem chegar a várias dezenas de pessoas. Tais grupos são organizados de maneira mais ou menos hierárquica, divididos segundo a formação de seus componentes, seus interesses e especialidades. Com efeito, pesquisas de campo em arqueologia são empreitadas caras e podem transformar-se em pesadelo logístico caso não sejam corretamente organizadas. Ao mesmo tempo, é fundamental boa dose de flexibilidade na concepção e condução dos trabalhos, sob o risco de comprometer o andamento deles.

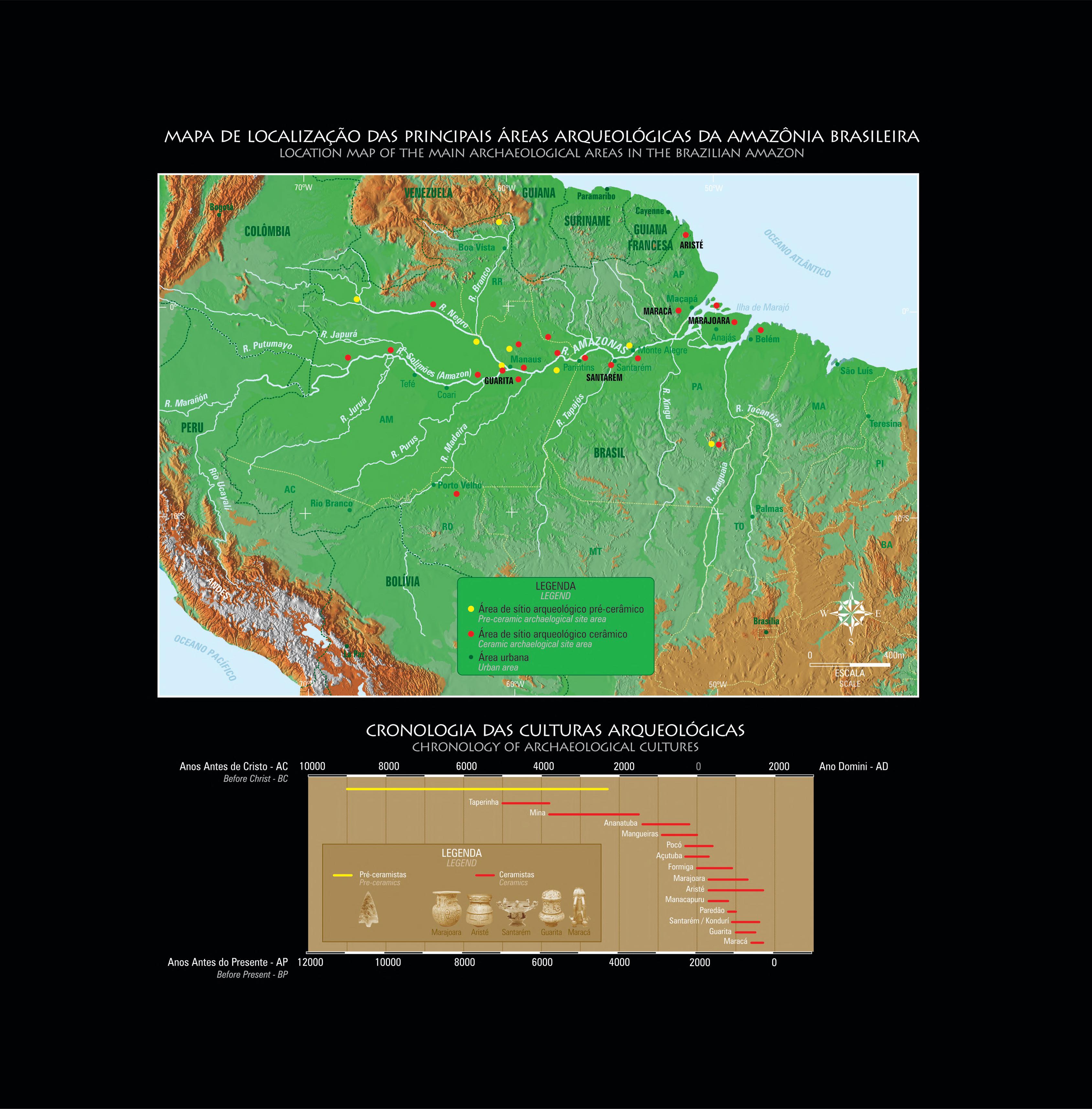

Existem alguns lugares do mundo onde ocorre tênue equilíbrio entre as exigências da pesquisa e as condições logísticas da prática arqueológica. A Amazônia é um deles. O desconhecimento da história antiga da ocupação humana da região é diretamente proporcional às dimensões continentais de lá: veem-se bacias de rios de grande porte – as quais em outros países estariam entre as maiores – que são muito mal conhecidas ou praticamente desconhecidas. As distâncias são grandes, o transporte muitas vezes se faz apenas por água e ar, e a mata recobre os sítios, escondendo os vestígios e dificultando visualizar materiais que ocorram em superfície.

Archaeologists have a special relationship with their subject: they need to destroy it in order to study it. An archaeological excavation is nothing more than the destruction of sites where vestiges have lain deposited for hundreds, thousands or even millions of years. Granted, such destruction is performed with proper methods, developed in the last 200 years, and it is the correct use of such methods that tells apart archaeologists from site robbers, or huaqueros, as they are known in many Latin American countries. The need to apply field methods also makes archaeologists normally walk in bands. The established image that associates field archaeology to a solitary practice is false. More often than not, site excavation requires the mobilization of numerous groups, which may have dozens of people. Such groups are organized in a more or less hierarchical manner, divided according to its members’ training background, interests and expertise. Indeed, field research in archaeology is an expensive endeavor and can become a logistic nightmare if not correctly organized. At the same time, it is fundamental to have a good amount of flexibility when conceiving and carrying out the work, lest its course be compromised.

There are some places in the world where a fragile balance occurs between the demands of research and the logistic conditions of archaeological practice. The Amazon is one of them. The ignorance of the ancient history of human occupation there is directly proportional to the region’s continental dimensions: one sees large river basins – which in other countries would be among the largest – that are very poorly known or virtually unknown. Distances are enormous, transportation is often made only by water or air, and the forest covers the sites, hiding vestiges and making it difficult to view material that lie on the surface.

All these conditions create a special relationship between archaeologists and the region’s inhabitants, whether they are Amerindians, mestizos or migrants who arrived from

Todas essas condições criam uma relação especial entre os arqueólogos e os moradores da região, sejam índios, sejam caboclos, sejam migrantes que ali chegaram nas últimas décadas. Na Amazônia, a arqueologia tem sabor particular porque, em muitos casos, os atuais habitantes dos lugares onde se encontram os sítios descendem dos antigos ocupantes. Isso é particularmente óbvio nas terras indígenas localizadas na periferia da Amazônia. Em outras partes do Brasil, tal relação não existe ou não é tão clara, uma vez que os povos indígenas foram extintos ou removidos para a posterior ocupação por descendentes de europeus, africanos ou asiáticos.

Ao mesmo tempo, é cada vez mais claro que, na Amazônia, dá-se rica interpolação entre a história natural e a história cultural. Durante décadas ou mesmo séculos, construiuse a imagem de que a região seria uma das últimas fronteiras inexploradas e desocupadas no planeta – um ambiente hostil e refratário à ocupação humana, habitável apenas por pequenos grupos nômades que viviam à míngua e estavam sujeitos à ação restritiva de fatores ecológicos. A construção dessa imagem, no entanto, resulta da própria história da colonização europeia. No século 18, quando os primeiros cientistas realizaram viagens de pesquisa e observação na Amazônia, os povos nativos já haviam passado por uma história de mais de dois séculos de contato, com a transmissão de doenças contra as quais não tinham imunidade e com as expedições militares empreendidas pelas potências coloniais. Assim, não é por acaso que a maior parte das terras indígenas de grande porte na Amazônia brasileira se localize hoje na periferia da bacia, como no alto Xingu, no alto rio Negro, no Acre, na região do Tumucumaque ou em Roraima. Trata-se de áreas distantes do eixo principal do Amazonas, que desde o século 16 serviu como caminho de penetração e ocupação.

Mas, paradoxalmente, a riqueza arqueológica das áreas localizadas às margens do Amazonas é imensa, já que registra uma ocupação humana iniciada há mais de 11 mil anos. Há, por exemplo, cerâmicas que estão entre as mais antigas do continente americano, datadas em cerca de 8 mil anos; e evidências de modificações significativas na paisagem, como a formação de férteis solos antrópicos, datadas em cerca de 2 mil anos. Essa rica história de

ocupação humana só pode ser compreendida com base no estudo dos sítios arqueológicos e dos restos materiais neles preservados.

No final do século 19 e início do século 20, quando os primeiros antropólogos começaram a realizar pesquisas na região, os povos indígenas se encontravam em situação difícil, resultante dos abusos associados ao ciclo da borracha, abusos descritos já naquela época e ainda hoje vivos na tradição oral. Foi nesse contexto histórico extremo que se constituíram sobre os modos dos povos indígenas da Amazônia as visões simplistas que se consagraram na ciência e no senso comum – a ideia de que esses povos não têm história, de que seriam habitantes primitivos de uma floresta inóspita ou ocupantes inocentes do último paraíso na Terra. Tais perspectivas não consideram as informações trazidas pela arqueologia.

Dessas informações, é provável que a mais importante diga respeito à contribuição dos indígenas e caboclos à constituição das paisagens atualmente conhecidas na Amazônia. Aqui, o termo paisagem pode ser compreendido de maneira simples como natureza modificada pela atividade humana. A antropologia tem nos mostrado que, para os povos nativos da Amazônia, é muito tênue a separação entre o que se constitui como o mundo da natureza e o que se constitui como o mundo da cultura. Dessa perspectiva, plantas, animais, afloramentos rochosos, cachoeiras e outros componentes do mundo natural têm vida própria e, sobretudo, capacidade de agir com base numa lógica apreensível pela chave da cultura. A arqueologia mostra que, junto com a apropriação simbólica da natureza, ocorreu outra, agora material, levando à formação de novas paisagens, produtos históricos da atividade humana que, portanto, não existiam naturalmente na região.

As paisagens formadas pela atividade humana no passado amazônico estão quase sempre associadas a sítios arqueológicos. Há um número de espécies vegetais que tendem a ocupar áreas cobertas por sítios e concentrar-se ali. Dentre tais espécies, estão vários tipos de palmeira, como o uricuri, o marajá e o caioé. Na Amazônia central, ocorrem também outras plantas que ocupam áreas de sítios; é o caso, por exemplo, da limorana. Assim, sítios arqueológicos funcionam como ilhas que concentram maior densidade de algumas espécies vegetais.

other parts of Brazil in the last decades. In the Amazon, archaeology has a peculiar flavor, because in many cases the current inhabitants of the places where sites are found descend from the ancient occupants. This is particularly obvious in the Amerindian reserves located in peripheral Amazon. In other parts of Brazil, such a relationship either does not exist or is not so clear, because native peoples either became extinct or were removed for the later occupation by descendants of Europeans, Africans or Asians.

At the same time, it is increasingly clear that in the Amazon a rich intertwining between natural and cultural history occurs. For decades or even centuries, an image was constructed that the region would be one of the planet’s last unexplored and unoccupied frontiers – a hostile environment, unyielding to human occupation, inhabitable only by small groups of nomads who lived in squalor and were subject to the restrictive action of ecological factors. The construction of that image, however, is a result of the history of European colonization itself. In the eighteenth century, when scientists first undertook research and observation journeys to the Amazon, the native peoples had already gone through a history of over 200 years of contact, with the transmission of diseases against which they had no immunity and with military expeditions promoted by the colonial powers. Thus, it is not by chance that most of the large-sized Amerindian reserves in the Brazilian Amazon are located in the basin’s periphery, as in the upper Xingu, or the upper Negro, or Acre, or the Tumucumaque region, or Roraima. These are distant areas from the main axis of the Amazon River, which since the sixteenth century has functioned as a pathway of penetration and occupation.

Paradoxically, however, the archaeological wealth of the areas on the banks of the Amazon River is immense, since it records human occupation that started over 11,000 years ago. There are, for example, ceramic artifacts that are among the oldest in the Americas, dated from 8,000 years, and evidence of significant changes in the landscape, with the formation of fertile anthropic soils dated from 2,000 years. This rich history of occupation can only be understood based on the study of archaeological sites and the material remains preserved there.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when anthropologists first started conducting research in the region, the indigenous peoples were in a serious predicament, resulting from the abuses related to the economic cycle of rubber. Such abuses were already described at that time and still survive in today’s oral tradition. It was in this extreme historical context that the simplistic visions about the ways of the peoples of the Amazon were constructed and enshrined in science and common sense – the idea that such peoples have no history, that they would be primitive inhabitants of an inhospitable forest, or innocent occupants of the last paradise on earth. Such perspectives do not consider the information brought to light by archaeology.

From all this information, it is likely that the most important relates to the contribution of indigenous peoples and Caboclos to the making of the currently known Amazon landscapes.

Here, the term “landscape” can be understood in a simple way as the nature modified by human activity. Anthropology has shown us that, for the native peoples of the Amazon, the separation between the world of nature and the world of culture is very tenuous. From that perspective, plants, animals, rocky outcrops, waterfalls and other components of the natural world have their own life and, above all, the ability of acting based on a logic that is understandable with the key of culture. Archaeology shows that along with the symbolic appropriation of nature, another one arose a material one, causing new landscapes to be formed, consisting of historic products of human activity, which therefore did not exist naturally in the region.

The landscapes formed by human activity in the Amazon’s past are almost always associated with archaeological sites. There are a number of plant species that tend to occupy areas covered by sites and to concentrate themselves there. Among such species are several types of palm trees, such as uricuri (Bactris tomentosa), marajá (Pyrenoglyphis maraja), and caioé (Elaeis melanococca). In central Amazon, other plants also occur occupying site areas; for example, the limorana grass (Gynerium sagittatum). So, archaeological sites function as “islands” that concentrate a greater density of some plant species. Also concerning the relationship between human beings and plants, it is now known that it was in the Amazon that some very important species, such as manioc and pupunha palm (Bactris gasipaes), were domesticated.

Ainda no que se refere à relação entre seres humanos e plantas, sabe-se atualmente que na Amazônia foram domesticadas algumas espécies muito importantes, como a mandioca e a pupunha. É possível que, no início do século 16, a região fosse um grande mosaico de jardins. Por certo não jardins como hoje os conhecemos, formados de gramados e canteiros de flores cuidadosamente mantidos. Aqueles jardins amazônicos se constituíam de ilhas de áreas cultivadas; de roças em diferentes estágios de uso e abandono; de áreas abandonadas (antigas roças ou aldeias, abertas a golpes de machados de pedra polida e ao calor do fogo, plenas de espécies frutíferas ou outras economicamente importantes); de trilhas, caminhos ou estradas que cruzavam a mata e conduziam de uma aldeia a outra; e das próprias aldeias, algumas de grande porte e com centenas de anos de ocupação contínua. Esses jardins na terra eram completados pelo rico mundo aquático dos rios, lagos e várzeas. Viajar por esse mundo é um convite a perder-se num labirinto saturado de água e cheio de surpresas: pequenos furos ou canais entupidos por troncos caídos podem levar a lagos que se abrem repentinamente e se anunciam à vista em clarões que interrompem a escuridão das matas alagadas. Nos altos barrancos que se derramam abruptamente em falésias sobre esses lagos, encontram-se em geral os sítios arqueológicos.

É assim, naquela grande escala geográfica, que se inscrevem a arqueologia e o trabalho dos arqueólogos na região. Fazer arqueologia na Amazônia é uma forma de conhecê-la da perspectiva da paisagem, é perceber que a imensidão dos rios e florestas esconde uma rica história cujo significado apenas começamos a decifrar.

O trabalho de Maurício de Paiva, a par da beleza única, tem a força de captar essa dimensão. As fotos de Maurício exibem rica sensibilidade arqueológica: mulheres, homens, crianças, bichos, plantas, objetos e paisagem têm vida, são agentes. À dimensão estática das imagens emerge uma tensão que nada mais é que a manifestação da vida a escorrer continuamente, mesmo que congelada num instantâneo. Essa operação, passando do registro estático à dinâmica da vida, é exatamente a realizada pelos arqueólogos em suas investigações. O que são sítios arqueológicos senão registros estáticos, no presente, de histórias complexas e dinâmicas que ocorreram no passado? Maurício, a sua maneira, produz em imagens uma arqueologia do contexto da arqueologia na Amazônia, donde a escolha feliz do título deste livro.

Nos últimos anos, tenho tido a chance de trabalhar com Maurício em etapas de campo pela Amazônia. Isso me deu as condições para entender seu método de trabalho. Se é inegável o talento do fotógrafo em produzir imagens fortes, elas só se puderam construir pela opção de permanecer horas ou mesmo dias no mesmo local, convivendo com caboclos e arqueólogos, observando seus modos de agir, suas relações entre si, com objetos e com a natureza. Trata-se, sem dúvida, de um trabalho de paciência, feito desapressadamente, composto de longas esperas, inspirado na contemplação, bem à moda amazônica.

É particularmente feliz a escolha dos caboclos como protagonistas de muitas das imagens. Eles foram tradicionalmente relegados pela ciência ou pelo poder público como personagens secundárias na história ou no desenvolvimento de políticas para a Amazônia, como se fossem apenas herdeiros impuros de um passado autêntico que se perdeu. Tal visão simplifica em demasia o profundo conhecimento que os caboclos têm sobre o contexto geográfico e ecológico dos locais onde vivem. O rico paradoxo do modo de vida caboclo é a mistura da modernidade com a tradição. Esse modo deve sua origem à história colonial da Amazônia, mas foi a demanda por borracha, impulsionada pelo mercado externo, que levou à fixação de migrantes nordestinos a partir do final do século 19. Com o fim dos ciclos da borracha, aqueles migrantes e seus descendentes, misturados aos descendentes dos índios que povoam há milênios a região, permaneceram ocupando as beiras de rios e lagos – os locais onde, vimos, costumam estar os sítios arqueológicos.

Na Amazônia contemporânea, os caboclos são os grandes guardiões dos sítios arqueológicos. É sobre esses sítios que moram, é nas terras pretas que fazem suas roças, é dali que extraem seus modos de vida e de reprodução. Qualquer política ou ação que vise à valorização ou estudo daquele patrimônio precisa passar por esse reconhecimento. Espero que a beleza do trabalho de Maurício e a possibilidade de divulgá-lo neste livro possam contribuir para tal sensibilização.

Doutor em arqueologia pela Universidade de Indiana (EUA), professor do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da USP e coordenador do Projeto Amazônia Central

It is possible that, in the early sixteenth century, the region was a great mosaic of gardens. They certainly were not gardens as we know them today, made of carefully maintained lawns and flower beds. Those Amazon gardens were “islands” of cultivated areas in different stages of use and neglect; abandoned areas (old cultivated plots or villages, opened by fi re and polished-stone axes, full of fruit-bearing and other economically important species); trails, paths or roads that crossed the forest and led from one village to another; and the villages themselves, some of them large, with hundreds of years of continuous occupation. Such gardens were complemented by the rich aquatic world of rivers, lakes and flood areas. Traveling in this world is an invitation to lose oneself in a labyrinth saturated with water and full of surprises: small channels obstructed by fallen trunks may lead to lakes that open suddenly and announce themselves to sight in flashes that break the darkness of the flooded forest. It is generally in the high escarpments that fall abruptly in cliffs over those lakes that archaeological sites are found.

It is so, in that grand geographic scale, that archaeology and the work of archaeologists in the region fit themselves. To work with archaeology in the Amazon is a way of getting to know it from the perspective of the landscape; it is realizing that the vastness of the rivers and forests hides a rich history whose meaning we are only starting to decipher.

Maurício de Paiva’s work, in addition to its unique beauty, has the strength of capturing that dimension. Maurício’s pictures show a rich archaeological sensibility: women, men, children, animals, plants, objects and the landscape are alive; they are agents. From the static dimension of the images emerges a tension that is nothing more than the manifestation of life that flows continually, even if frozen in an instant image. That operation, going from a static record to the dynamics of life, is exactly what archaeologists perform in their investigations. What are archaeological sites other than present-day static records of complex and dynamic stories that happened in the past? Maurício, in his own way, produces in images an archaeology of the context of archaeology itself in the Amazon; hence the fortunate choice of this book’s title.

In recent years, I have had the chance to work with Maurício in the field throughout the Amazon. This has enabled me to understand his working method. Although the photographer’s talent in producing strong images cannot be denied, they could only be constructed through the choice of staying for hours or even days at the same place, living together with Caboclos and archaeologists, observing their ways of acting, their relationship with each other, with objects and with nature. It is doubtlessly a work of patience, made without hurry, made up of long waits, inspired in contemplation, just in the Amazon’s way.

Featuring the Caboclos as protagonists of many images was a particularly fortunate choice. Science and the government have traditionally relegated them to secondary roles in the history or the development of policies for the Amazon, as if they were only impure heirs of an authentic past that has been lost. Such a view oversimplifies the deep knowledge the Caboclos have about the geographical and ecological context of the places where they live. The rich paradox of the Caboclo way of life is a mix of modernity and tradition. That way of life arose from the

Amazon’s colonial history, but it was the demand for rubber, propelled by the foreign market, that led migrants from Northeastern Brazil to settle there, starting from the late nineteenth century. When the rubber economic cycles ended, those migrants and their descendants, intermixed with the descendants of the Amerindians who have populated the region for thousands of years, remained occupying the banks of rivers and lakes – the places where, as we have seen, archaeological sites often are.

In the contemporary Amazon, Caboclos are the great guardians of archaeological sites. They live on those sites; it is on the terras pretas that they farm their small fields; it is from there that they take and reproduce their ways of life. Whatever policy or action aiming to value or study those riches must necessarily acknowledge this reality. I hope the beauty of Maurício’s work and the possibility of making it known through this book may contribute to make people more aware of that.

Mais um barco se apronta para sair. Mulheres entram trazendo seus filhos e suas sacolas. E homens, carregando caixas nos ombros. Muita gente embarcando rapidamente, escolhendo o melhor lugar para armar a rede e depositar o aparelho de som, que garantirá a trilha sonora de todo o percurso. Alguns estão voltando para casa, outros vão a um batizado, há quem esteja deixando o lar para encontrar novos destinos. A viagem é longa, são dias pela imensidão do rio. Durante a noite faz muito frio, mas o dia é ensolarado e calmo, como a superfície plana da água. Nas margens, aqui e acolá, algumas casas de madeira, com a pintura azul desbotada, rodeadas de altas palmeiras. E a densa mata, muralha muito verde.

De vez em quando, uma pequena canoa se aproxima do barco. Crianças sobem pela corda. Trazem camarões secos ou açaí batido. Antes que todos possam reparar na mercadoria, voltam para o casco. Não devem se afastar de casa. Um trânsito incessante que se repete a cada dia, levando pessoas de uma grande cidade à outra, parando em outras menores, atravessando as estradas fluviais. Se para mim é uma novidade essa experiência, para o morador da Amazônia são caminhos habituais, rumos que se tomam desde tempos muito remotos, quando outros eram os que dominavam essa paisagem.

Olhar as pequenas casas isoladas e pensar que há quinhentos anos, quando os primeiros europeus trilharam o mesmo caminho em viagem de reconhecimento, boa parte dessa área era bem mais habitada que hoje é uma espécie de volta no tempo. Caminhar por essas

Yet another riverboat gets ready to leave. Women come in, bringing their children and their bags. And men, carrying boxes on their shoulders. Lots of people boarding quickly, choosing the best place to hang their hammocks and lay their sound devices on, to ensure the soundtrack of the whole voyage. Some are coming home; others are going to some baptism ceremony; there are those who are leaving home to find new destinations. The voyage is long, days on the vastness of the river. At night it is very cold, but days are sunny and quiet like the even surface of the water. On the banks, here and there, some wooden houses, with a faded blue paint, surrounded by tall palm trees. And the dense forest, a very green wall.

Once in a while, a little canoe comes close to the boat. Children climb the rope. They bring dried shrimp or mashed açaí fruit. Before all can see their merchandise, they get back to the hull. They must not go far from home. An endless traffic that repeats itself every day, taking people from one city to the other, stopping in small towns, traversing the fluvial roads. While the experience is new for me, for the Amazon dweller these are habitual paths, ways that are taken since very remote times, when other people dominated this landscape.

To look at the small isolated houses and to think that 500 years ago, when the first Europeans traversed the same path in a surveying voyage, a large part of this area was much more populated than today is like a kind of travel back in time. To walk on these banks thousands of years ago might mean finding roads, villages, cultivated plots, unknown

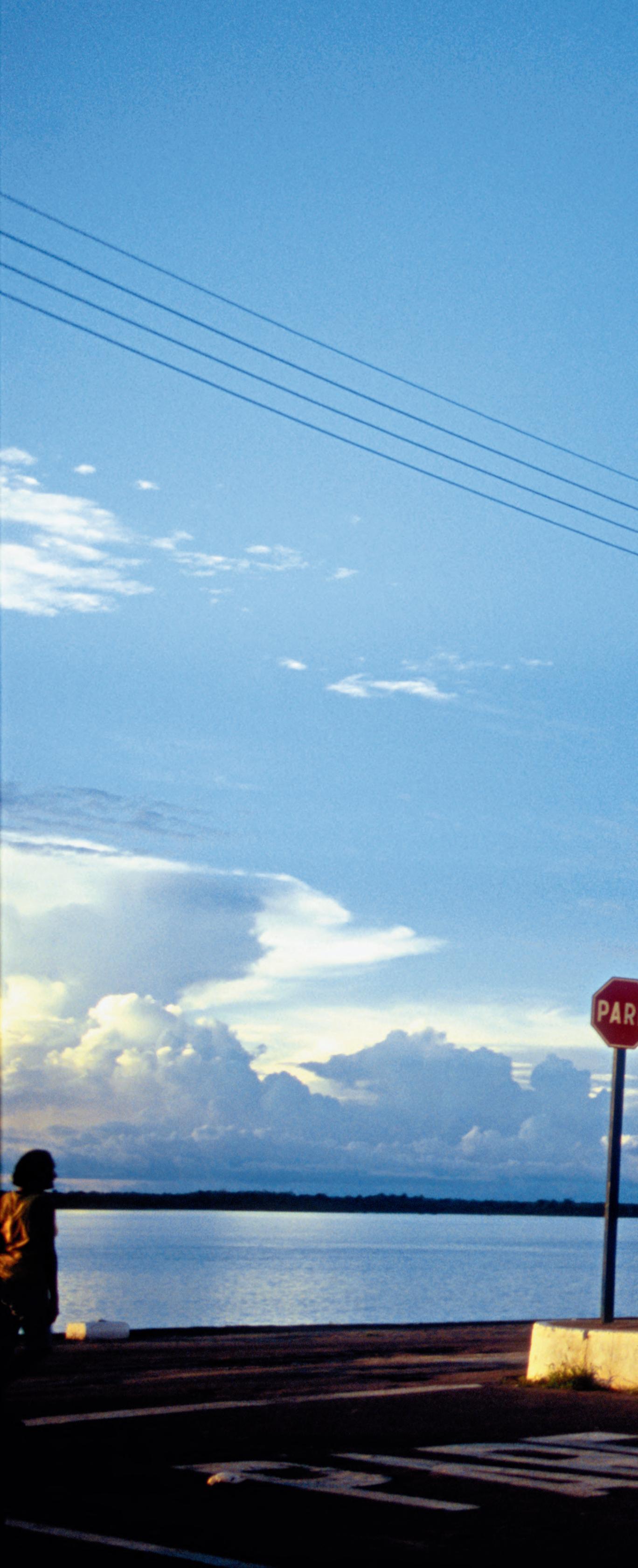

No litoral e nos estuários do Pará e Maranhão, a pesca tradicional sofre forte influência das variações da maré, que apresentam metros de amplitude. Já se identificaram ali sítios com algumas das cerâmicas mais antigas na América do Sul, além de sambaquis em torno de 5500 anos. Ilha de Apeú Salvador, Pará. PP. 20-3, 26-9

In the coast and estuaries of Pará and Maranhão, traditional fishing is under the strong influence of tidal variations, several meters high. Sites have been identified there which yielded some of the oldest ceramic objects in South America, in addition to sambaquis (sand and seashell middens) around 5,500 years old. Apeú Salvador Island, Pará. PP. 20-3, 26-9

margens há milênios podia significar o encontro com estradas, aldeias, plantações, línguas desconhecidas. Adentrar os sertões podia levar a outros povoados, densos agrupamentos situados a vários dias de caminho por terra ou água.

Cada vez que o barco aporta, as pessoas se acotovelam, céleres, para pisar novamente em terra, tão carregadas que estão com suas crianças e seus pertences. Há pressa, sempre há pressa. Próximo ao porto, muitas vezes há também um mercado. Ervas medicinais, frutos da terra, colheitas recentes, peixes de boa carne. E cestos e potes e panos e colares e pulseiras. Analisando vestígios arqueológicos, sabe-se hoje que, unindo toda a Amazônia, bem antes desses atuais mercados, já havia uma complexa rede de intercâmbio comercial. Peixe seco produzido por ribeirinhos, farinha torrada por sertanejos, ferramentas talhadas em rocha, ornamentos dourados que vinham de uma tal aldeia do ouro. Para lá e para cá, havia quem ia e vinha com suas embarcações lotadas de produtos comerciáveis. No estoque fluvial, seguia junto um pouco do saber de cada povo. Um diferente modo de curar uma doença, um trejeito de dança, um desenho na pintura da vasilha. E umas estórias que se espalhavam igarapés adentro, unindo diferentes povos em semelhantes devoções, mostrando que o fio da religiosidade percorria longos caminhos na disseminação do sagrado.

Hoje, os devotos podem estar no Círio de Nazaré, na festa que homenageia santa Rita ou num modesto culto evangélico, como o que presenciei uma noite lá na pequena e pouco conhecida Vila Tessalônica, no arquipélago de Marajó. No dia seguinte, numa construção ao lado, onde funciona um pequeno posto médico, uma funcionária se encarrega de fazer o teste de malária no menino febril, que veio de uma viagem de três horas remadas pelo braço moreno do pai.

Na frente, alheias à presença de qualquer enfermidade, crianças correm divertidas pelo arruado de madeira suspenso.

Mostram-me cacos de cerâmica encontradas à beira do espelhado rio Araramã, vasilhas desenterradas, urnas funerárias. A mãe de uma delas me chama e aponta a “greguinha” –uma urna semienterrada, onde volutas que realmente lembram as gregas me dizem algo que não posso compreender.

Seu José Ferreira, apesar da aparência jovial, é um dos moradores mais antigos do lugar. Sentado num banco sob uma grande árvore que se debruça sobre o rio, ele me esclarece que as urnas serviam para “agasalhar os mortos”. Meu pensamento profano não se entretém por muito tempo imaginando quem tomava agasalho na greguinha. Nessa hora, estou intrigada é com a peça em si, um ícone da cultura marajoara. Os marajoaras, que habitaram todo esse arquipélago paraense entre os anos 450 e 1350, eram exímios ceramistas. No rastro dessas peças, arqueólogos vão estudando os locais que eles ocupavam, suas relações sociais

e políticas, a extensão de seus domínios, a possibilidade de que tivessem uma sociedade hierarquizada, com divisão de trabalho.

Mas é a estética de seus desenhos o que mais diz sobre essa cultura. Num emaranhado de signos, compõem-se narrativas míticas. Entre os traços, há padrões que se repetem em novas combinações a cada peça, um novo conjunto, uma nova estória escrita.

Você leu escrita porque é assim mesmo que se pode definir a iconografia marajoara: uma escrita. Denise Pahl Schaan, arqueóloga que há vários anos estuda tais cerâmicas, defende que se trata realmente de um tipo de código gráfico. Não da forma que se alinham as letras que você está lendo neste papel, já que se tratava não de representações sonoras, mas de representações míticas. Algo talvez muito complexo para a objetividade do nosso pensamento atual.

Pois é… Tanta gente falando de outras culturas pré-colombianas, e de repente alguém nos ensina que, aqui mesmo no Brasil, um grupo indígena chegou a um grau de sofisticação tão elevado que possuía sua própria escrita. Feito que nem os cultuados incas ou seus antecessores mochicas alcançaram. Quantas coisas mais os marajoaras dominavam que nem sequer imaginamos?

E eles não foram os únicos a imprimir suas crenças em cerâmica. De Marajó, na foz do Amazonas, ao limiar dos Andes, outros povos desenvolveram técnicas cerâmicas sofisticadas, inclusive as policromas, recobertas com pinturas em preto e vermelho sobre superfície tingida de branco. Talvez não tivessem escrita própria, ou não sejamos capazes de compreendê-la como tal, mas estão ali seus mitos, suas devoções, suas estórias do dia e da noite. Para o bem viver, generosos pratos de comida que serviam dezenas de pessoas de uma só vez, recipientes para substâncias alucinógenas destinadas a rituais xamânicos, grandes vasilhas para armazenar bebidas. Para o bem morrer, urnas funerárias de diversos feitios. Algumas, em bojudas formas, abrigavam corpos inteiros, acomodados com alguns pertences. Outras, onde iam apenas os ossos, o formato repetia a figura humana. Mulheres com pontudos peitinhos de barro, homens sentados em banquinhos. Interessantes figuras ornadas com suas joias e pinturas, representantes de pessoas que há muito deixaram de pisar esses chãos.

Se os pesquisadores ocupam-se por dias seguidos com um caco de cerâmica tentando extrair dele confissões seculares, os moradores igualmente criam suas próprias teorias. Na comunidade de Santa Rita da Valéria, em Parintins, Amazonas, mora Geraldo França, experiente artesão que faz objetos de madeira para vender a ocasionais turistas. Acostumado à presença de pesquisadores, questiona com sutil sabedoria: “É a mão de Deus? Assim eu vejo estas cerâmicas, como a mão de Deus”. Talvez não o Deus a quem ele faz suas preces diariamente, mas outros deuses, que se faziam gente para tomar as mãos de artesãos habilidosos e inscrever no barro sagrado sua mensagem milenar.

languages. To go further inland could lead to other settlements, dense groupings several days away on foot or by boat.

Now, every time the riverboat docks, people cram themselves speedily to tread on land again, so overloaded are they with their children and their belongings. There is hurry, there is always hurry. Next to the mooring, there is often also a market. Medicinal herbs, local fruit, recent crops, good fish. And baskets, pots, fabrics, collars and wristbands. By analyzing archaeological vestiges, it is now known that well before the current markets there was already a complex trade network. Dried fish produced by riverbank dwellers, toasted manioc flour made by inland people, tools carved in stone, golden ornaments that came from a so-called “village of gold.” There were those who came and went back and forth with their vessels full of trading goods. In the riverine inventory, something of each people’s wisdom went along: a different way of curing a disease, a dance mannerism, a pattern in a pot’s painting, and some stories that were spread inland on the side streams, uniting different peoples in similar devotions, showing that the thread of religiousness fared long ways disseminating the sacred.

Today devouts may be at Belém’s feast of Our Lady of Nazareth, or at the feast in honor of Saint Rita, or in a modest Protestant cult, such as the one I witnessed one night in small and little known Vila Tessalônica, in the Marajó archipelago. The next day, in a neighboring building where a small clinic operates, a female civil servant is testing a febrile boy for malaria; he came on a three-hour canoe journey, with his father’s darkskinned arms rowing all the way.

Ahead, oblivious to any infirmity, amused children run on the suspended wooden paths.

They show me ceramic shards found on the bank of the mirror-like Araramã River, unearthed pots, funeral urns. One of the children’s mother calls me and points to the greguinha (“the little Greek one”), a half-unearthed urn where curved traces that really look Greek tell me something I cannot understand.

José Ferreira, in spite of his jovial appearance, is one of the place’s oldest inhabitants. Sitting on a bench under a large tree that bends itself over the river, he tells me that the urns’ purpose was to “dress the dead warm.” My profane thought does not entertain itself for long imagining who sheltered oneself from the cold inside the greguinha. At this time, I am really intrigued by the piece itself, an icon of the Marajoara culture. The Marajoara, who inhabited that entire archipelago in Pará in the years AD 450-1350, were accomplished potters. On the trail of their pieces, archaeologists keep studying the places they occupied, their social and political relationships, the extension of their domain, the possibility that they may have had a hierarchical society with a division of work.

But it is their drawings’ aesthetics that tells more about their culture. In a complex pattern of intertwined signs, mythical narratives are told. Between the traces, there are patterns that repeat themselves in new combinations in each piece – a new set, a new written story.

You have read “written” because this is exactly how one can define Marajoara iconography: a system of writing. Denise Pahl Schaan, an archaeologist who has been studying such ceramic pieces for several years, maintains that it is really a kind of graphical code. Not in the same way that letters are aligned on the paper you are reading, since those were not phonological representations, but mythical ones. Something maybe too complex for our current, objective way of thinking.

Here we are… So many people talking about other pre-Columbian cultures, and suddenly someone teaches us that right here in Brazil an indigenous group achieved such a high degree of sophistication that it had its own writing, a feat achieved by neither the revered Incas nor their Mochica predecessors. How much more the Marajoara mastered that we cannot even imagine?

And they were not the only ones to imprint their beliefs on ceramic. From Marajó Island, on the mouth of the Amazon River, to the edge of the Andes, other peoples developed sophisticated techniques with ceramic, including the polychromatic one, covered with black and red paintings on a white-coated surface. Maybe they did not have their own writing, or we are unable to understand it as such, but their myths are there, as are their devotions, their tales of the day and the night. For living well, generous food plates that served dozens of people at once, recipients for hallucinogenic substances meant for shamanic rituals, large vessels to store beverages. For dying well, funeral urns in several shapes. Some of those urns were potbellied and contained whole bodies, accommodated with some belongings. Others, wherein only the bones went, repeated the human shape: women with pointed little clay breasts, men sitting on little benches; interesting figures ornated with their jewels and paintings, representing people who stopped treading this ground a long time ago.

While researches busy themselves for days in a row with a shard of ceramic, trying to extract centuries-old confessions from it, the current inhabitants of the Amazon create their own theories. In the settlement of Santa Rita da Valéria, in Parintins, Amazonas, lives Geraldo França, an experienced artisan who makes wooden objects to sell to occasional tourists. Accustomed to the researchers’ presence, he questions with subtle wisdom: “Is it the hand of God? This is how I see these ceramic pieces, as the hand of God.” Perhaps not the God to whom he prays every day, but other gods, who made themselves human to take the hands of skilled craftspeople and inscribe in the sacred clay their thousands-years-old messages.

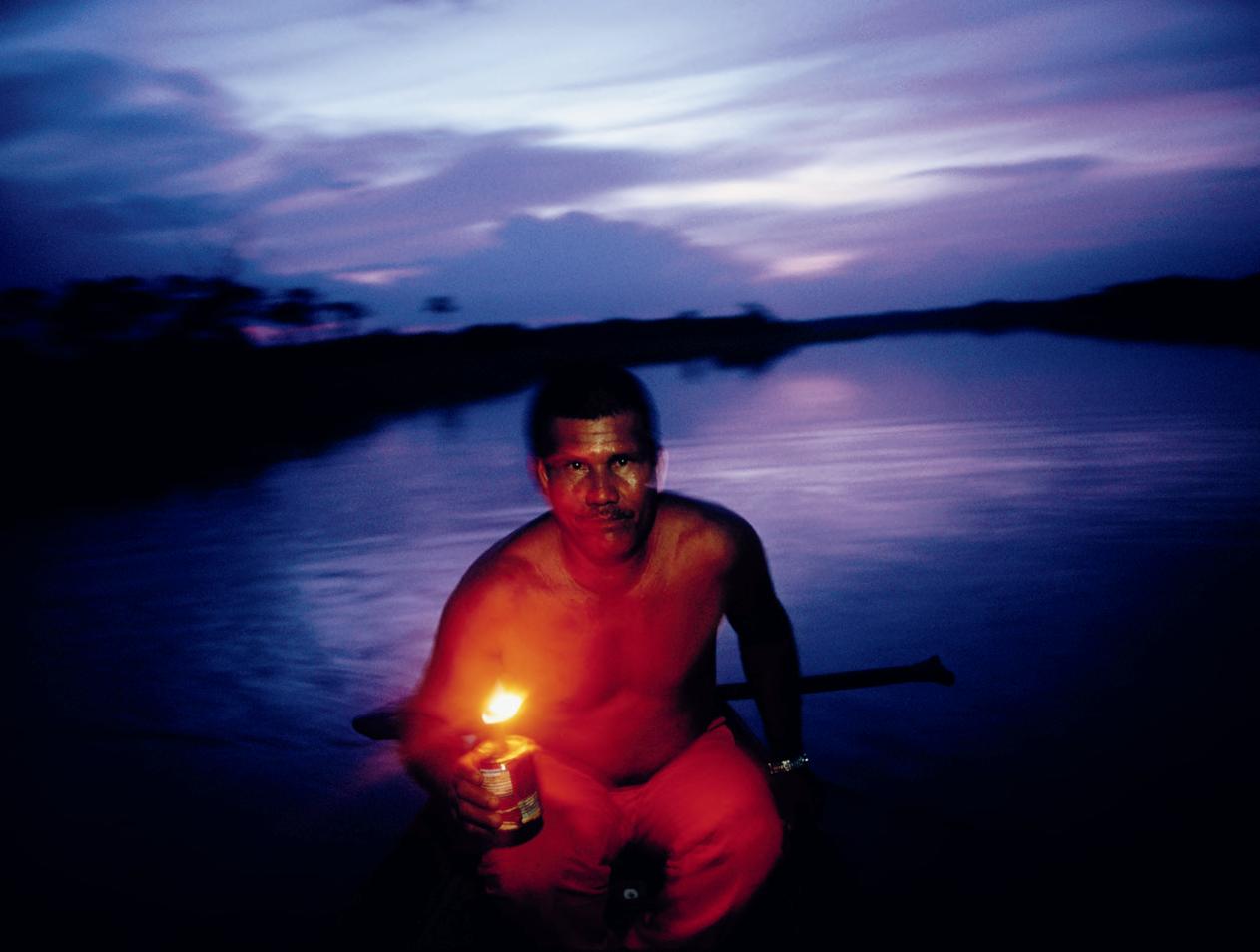

“Eu pescava muito, tudo quanto era peixe – tracajá, curimatã, tambaqui. Era muito. Tucunaré, surubim… Mas, olhe, eu nunca arpoei um peixe-boi neste lago; tem uns aí que escuta até cuspe n’água. […] Numa viagem, eu estava pescando pirarucu no buraco do Caju, vi um focinho, e a bocarra boiô pra mim, de uns três ou quatro metros. Eu gritei, e arpoemos pra descourar e tirar a manta dele. Na boca da noite, saímos na beira do lago comprido, o buritizal nos agasalhando pra outra banda. ‘Aquele fogo ali é a Cobra Grande’, eu disse pro meu parceiro do casco. Ela vinha baixando, passou perto de nós por arriba d’água, deslizando com fogo ou ao menos no feixe. Não vimos a cobra de verdade – mas o fogo sim!”

Nelson Neris, Santa Rita do Lago da Valéria, Parintins, Amazonas

“I used to fish a lot, all kinds of fish – tracajá, curimatã, tambaqui. It was a lot – tucunaré, surubim… But I’ve never been able to harpoon a manatee in this lagoon; there are some manatees out there that can hear even if one spits into the water. […] On a trip, I was fishing for arapaima at Caju Hole when I saw a muzzle and that big mouth mooed at me, some three or four meters away. I screamed, and we harpooned it to skin it and get its pelt. In the early evening, we went out on the edge of the long lake, the buriti palms guiding us to the other side. ‘That fire out there is the Big Snake, the fiery one,’ I said to my boat mate. It came slowly downwards and passed near us over the water, gliding with fire or at least a beam of light. We didn’t see the actual snake – but we did see the fire!”

Nelson Neris, Santa Rita do Lago da Valéria, Parintins, Amazonas

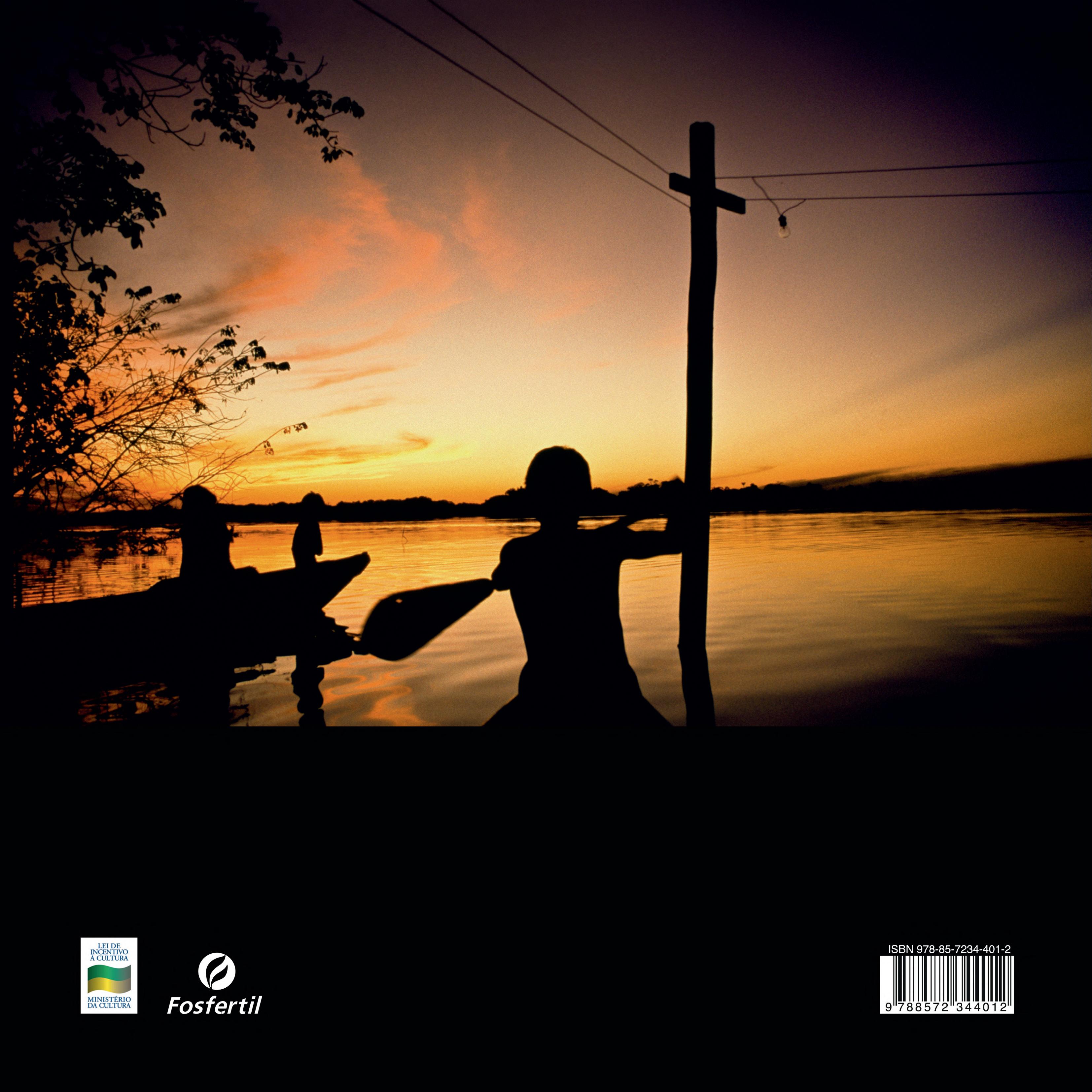

Comunidade Santa Júlia, rio Jurupari, ilha de Marajó O trapiche por onde o menino Comunidade Santa Júlia, rio Jurupari, ilha de Marajó. O por onde o menino caminha com sua lamparina ao crepúsculo foi construído sobre um aterro em que, há caminha com sua ao foi construído sobre um aterro em que, há 1600 anos, viviam os marajoaras 1600 anos, viviam os

Settlement of Santa Júlia, on the Jurupari River, Marajó Island The wooden path the Settlement of Santa Júlia, on the River, Island. The wooden the boy walks with his lamp at twilight was built on a landfill where the Marajoara lived walks with his at was built on a landfill where the lived 1,600 years ago years ago a n c i e n t a m a z o n • ancient amazon • 4 1 41

“E veio a chuva, a água e o aguaceiro. E veio o subterrâneo, vem enterrando e mostrando a lama, enterrando!

[…] Mas, mesmo sem você cavar, afloram aquelas cabecinhas todas que as crianças trazem.”

Um morador da comunidade de Bete Sêmis, rio Solimões, Amazonas

“And then came the rain, the water, the downpour. And there pops the underground, burying and showing the mud! […] But even if you don’t dig, all those little heads appear, and the children bring them.”

A dweller of the settlement of Bete Sêmis, Solimões River, Amazonas

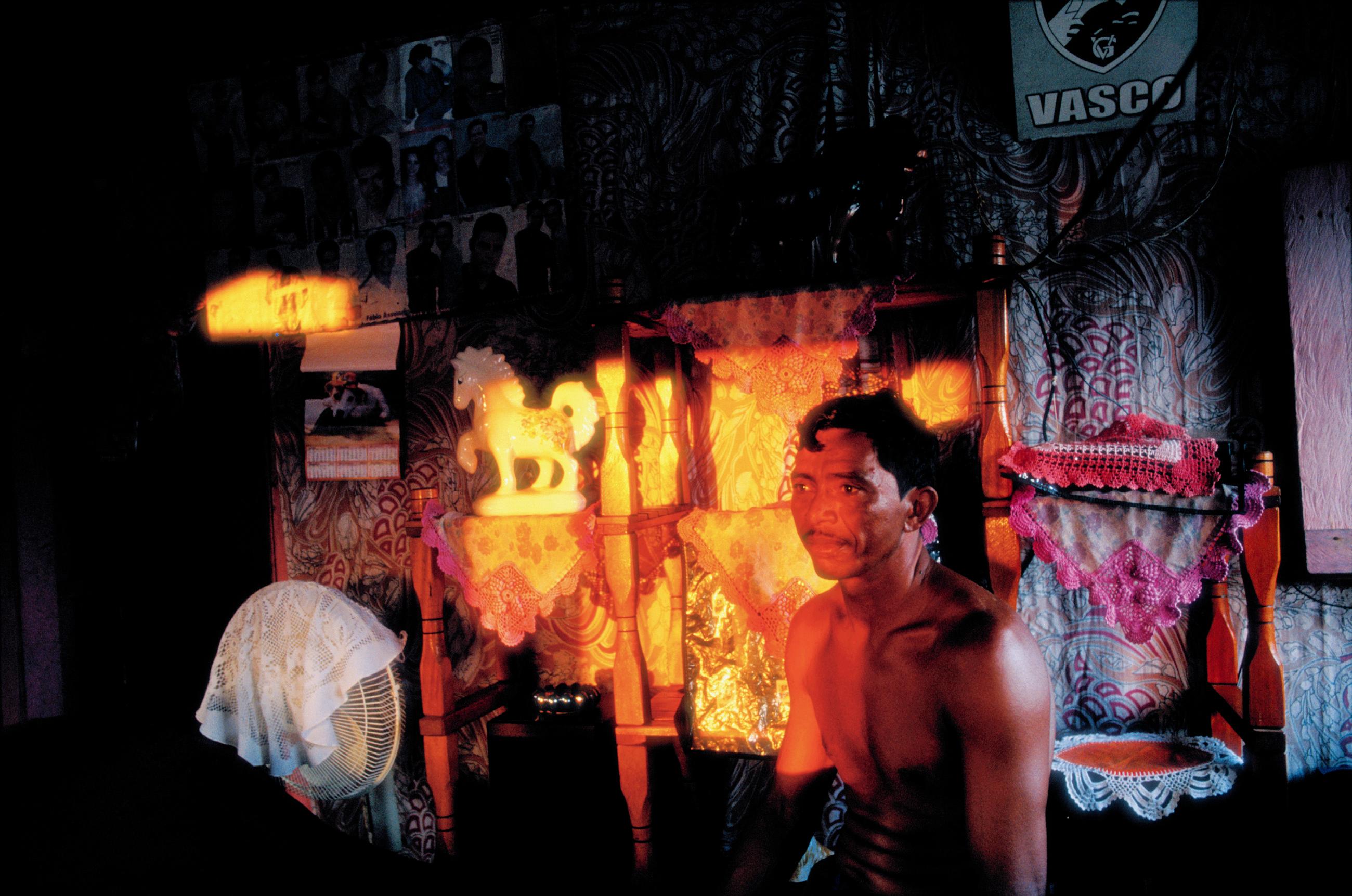

Caboclo em casa da comunidade de Sampaio, Autazes, Amazonas Caboclo em casa da comunidade de Amazonas Caboclo in a house of the settlement of Sampaio, Autazes, Amazonas Caboclo in a house of the settlement of Amazonas

Aqui e ali, esses objetos vão nos contando histórias dessas gentes, povoadores de um imenso território, num caminho temporal que se estende ao passado em mais de dez milênios, sucedendo-se uns aos outros. Até hoje, o caboclo ocupa e revive um modelo cotidiano que não difere muito do que seguiam os antepassados. Em cada sítio arqueológico, os vestígios remotos. Nos seus entornos, os caboclos de hoje.

Corre à boca miúda que, nessa relação, antropólogos preferem não usar a palavra herança . É fato: caboclos são os filhos mestiços de remanescentes indígenas com nordestinos atraídos pela borracha. Mas e esses habitantes do passado? É provável que, com a chegada dos colonizadores europeus, tenham migrado para outros territórios, sido dizimados por epidemias ou assimilados pelas missões religiosas e se desagregado socialmente. O fio dessa meada se perdeu. Mas, ora, não se pode olhar o caboclo de hoje sem perceber quanto ele é a continuidade de um cotidiano milenar. Se não há uma herança genética, material, há a herança dos costumes da terra.

Ainda saem em grupos de homens para espreita e caça de animais da floresta. Ainda pescam, seja a piranha para um breve caldo, seja o pirarucu que alimentará famílias inteiras. Ainda apanham argila nas beiras para modelar seus potes e trançam cestos de cipó, que usam na coleta de castanhas e frutas. E a mandioca reina absoluta, beneficiada em arcaicos fornos de barro, nas toscas casas de farinha. O sagrado atual já não se

Here and there, such objects keep telling us stories of those people, settlers of an immense territory, in a time path that extends itself to a past of over 10,000 years, replacing each other in succession. Even today, Caboclos occupy the place and relive a day-to-day existence that is not much different from what their ancestors lived. In each archaeological site, the remote vestiges. In the sites’ surroundings, today’s Caboclos.

It is widely rumored that anthropologists, when referring to that relationship, would rather not use the word “heritage”. Granted, Caboclos are the mestizo descendants of remaining indigenous people mixed with Northeasterners attracted by rubber. But what about the inhabitants from the past? It is likely that, when European colonizers arrived, those people migrated to other territories, were decimated by epidemics or assimilated by the religious missions, and became socially disjointed. The thread has been lost. But, well, one cannot look at today’s Caboclo without realizing how much he represents the continuity of a daily routine of thousands of years. If there is not a genetic, material heritage, there is the heritage of the customs of the land.

Caboclos still go out in groups of men to watch and hunt animals in the forest. They still fish, whether it is a piranha for a quick broth or an arapaima that will feed whole families. They still gather clay on the river banks to shape their pottery and weave vines into baskets, which they use to collect nuts and fruits. And manioc reigns absolute,

“Estão claras as relações a longa distância que ocorriam há milênios – expansões do baixo rio Orinoco, na Venezuela; do Napo; do norte da Amazônia; das Guianas; uma expansão humana que colonizou o Caribe […]. As paisagens foram transformadas pelas ocupações humanas como um pacote tecnológico de eco-história. A vida não é só manejo econômico: hoje as crianças caboclas brincam nos buracos de terra; a casa de farinha está arraigada na agricultura anterior. Eu diria transformação antrópica, porque houve ação do homem. É o que aparece aqui, no perfil da escavação; vemos que isso fica grudado nas sucessivas ocupações.”

Manuel Arroyo, arqueólogo chileno“The long-distance relationships that happened thousands of years ago are clear – expansions from the lower Orinoco River in Venezuela, from the Napo, from the northern Guyanas, a human expansion that colonized the Caribbean […]. Landscapes were transformed by human occupation like a technological package of ecohistory. Life is not only economic cultivation: today the Caboclo children play in the holes the ancients left in the earth; the manioc meal engine has its roots in earlier agriculture. I would call it anthropic transformation, because there was human action. This is what appears here in the excavation profile; we see that it stays sticked to successive occupations.”

Manuel Arroyo, Chilean archaeologist

Manuel Arroyo, Chilean archaeologist

apresenta vestido de híbrido humano e animal; está mesmo é numa pequena igreja de madeira, ora evangélica, ora católica. Mas as festas, estas, sim, continuam a manifestar alegria e fé. Já não adoram a Cobra Grande. Mas mantêm o respeito pelas grandes cobras. Esse homem é o mesmo que esbarra, quando capina a roça fincada na fértil terra preta, em fragmentos de cerâmica arqueológica. É, novamente, o homem ocupando seu lugar no ambiente amazônico.

O que separa esses dois mundos é a direção para onde voltamos nosso olhar: do chão à cabeleira do pé de açaí, onde pode haver um menino agarrado em busca de um cacho de frutos pretinhos, é domínio do presente. Do chão para baixo, onde estão enterrados restos de alimento, objetos esquecidos, corpos descarnados, reside o passado. Se olhamos para cima, vemos os que transitam na liberdade do ar. Para baixo, aprisionados no solo, camada sob camada, pedaços congelados do passado. Dois cotidianos que se espelham: um em constante movimento, outro estacionado na terra.

Os arqueólogos vão lá e raspam suas espátulas no chão que faz a tênue fronteira. Com suas ferramentas, vão desbastando centímetros de terra, procurando a parte oculta do espelho. Mas também estão interessados em conhecer os que ficam por cima, para compreender melhor como é essa relação. Conversam, achegam-se na hora do café, ouvem estórias de visagens, pegam uma carona de canoa.

Numa viagem há alguns anos, estive também abrigada entre esses moradores por alguns dias. Um episódio foi especialmente marcante. Depois de uma cansativa e frustrada caminhada pela mata em busca de um suposto sítio arqueológico, voltamos enfim à margem onde tínhamos aportado. Apenas para descobrir que a maré havia secado. Entre nós e nosso barco: lama. No começo, até que não foi tão difícil. Bastava levantar a perna bem alto, dar um passo largo, afundar o pé novamente. Mas os passos iam ficando cada vez mais pesados, e o sol mais ardido, e a lama mais funda. Quando ela já tinha engolido metade do corpo e o barco ainda estava a uns cinquenta metros de distância, percebi que a vida nunca havia me parecido tão difícil (nessa época, eu ainda não era mãe). Veio o desespero, a birrenta vontade de desistir e dormir na mata, à espera da

cheia da maré. Mas uma olhada rápida nos mostrou que a margem, naquela altura, já estava tão distante quanto a voadeira. Ir em frente era a única opção. O que aconteceu dali em diante não sou capaz de explicar. Um impulso inesperado, um segundo fôlego, um não-sei-quê de força. E já estávamos exaustos dentro do barco, com alguns rapazes caboclos que nos olhavam sem entender e um pequeno jacaré, amordaçado, que não teve a mesma sorte de safar-se.

Algumas horas depois, já tranquilos, compartilhamos o jantar com uma família ribeirinha, sem vizinhos à vista. A casa é de madeira, construída sobre pilares, para a passagem da água nos tempos de cheia. Em cima da mesa, a luz fraca de uma lamparina compete com as chamas do fogão a lenha, onde a mulher prepara graúdos camarões, tirados há pouco da água doce, que vai servindo a todos (o jacaré já era).

Estamos bem em frente ao gigante Amazonas, no ponto em que ele se casa com o oceano Atlântico, e cercados pela mata densa, distante muitas horas de barco da cidade mais próxima. À porta da casa, no alto da escada que leva ao solo, posso observar as crianças que se deliciam barulhentas e risonhas com o banquete singelo e o escuro absoluto que nos rodeia. Experimento compreender como é a vida dessas pessoas, tão isoladas do resto do mundo e, ao mesmo tempo, tão senhoras em sua solidão. Numa noite tão escura como essa, de pouca lua e muitas estrelas, não é difícil vislumbrar fantasmas de outras eras, visagens que caminham pela mata protegendo seus espaços sagrados. Mas não há medo. Só uma sensação de que a solidão é ilusória, de que, por todos os lados, guardiões espreitam. Vejo, aqui, apenas uma família de pai-mãe-e-filhos. Mas quem pode afirmar quantos pés de gente passaram por esse mesmo chão nos últimos milhares de anos?

Quem foram esses antigos habitantes do Brasil? Com que nomes batizavam seus filhos? Que mensagens inscreveram no barro cozido dessas urnas? Segredos guardados por tantos anos, enterrados numa terra que hoje é pisada pelos pés de outros homens. Outros homens que têm, por sua vez, seus próprios segredos para zelar.

processed in archaic clay ovens to make meal. Today’s sacred no longer presents itself dressed as a hybrid of human and animal; it is actually in a little wooden church, sometimes Protestant (mostly Pentecostal), sometimes Catholic. But the feasts do keep expressing joy and faith. They no longer adore the Big Snake, but they still respect large snakes. Those people are the same who stumbles upon fragments of archaeological ceramic when clearing the farming field created on the fertile terra preta . Again, people occupy their place in the Amazon’s environment.