The International Journal for Bee-Centred Beekeeping NBH No. 26 Winter 2023 IN PARTNERSHIP WITH

support from Ensuring Women Benefit from Bees Isaac Mbroh, Bees for Development Ghana The Tale of Varroa-resistance in Norway, Part 1 Dr Melissa Oddie, Norway Traditional Beekeeping in Lithuania, Yesterday and Today Simona Vatinaite, Lithuania

With

HELPING BEEKEEPERS KEEP BEES FOR OVER 100 YEARS

PACKAGING, QUEEN REARING, HEALTH & FEEDING, BOOKS, GIFTS, EDUCATION, CANDLEMAKING, AND MORE!

ON 25TH FEBRUARY WE WILL BE ATTENDING THE VERY FIRST

We will have a full range of equipment for you to browse.

As usual, you can order for collection from the show, including our sale items.

Make sure you render down your beeswax to bring to swap for fresh foundation - available from our lorry in the carpark!

FIND OUT MORE AT WWW.THEBEEKEEPINGSHOW.CO.UK

SHOP

The Top Bar hive is a single box with 24 top bars. Made from British cedar the top bar hive is the traditional way of keeping bees in some African and Caribbean countries. Became popular in the UK for non-invasive beekeepers.

FOUNDATION, HARDWARE

PROCESSING, LABELS,

HIVES, BEES, FRAMES,

& CLOTHING, HONEY

ONLINE,

THE PHONE, OR IN STORE LINCOLNSHIRE BEEHIVE BUSINESS PARK, RAND, NR WRAGBY, MARKET RASEN, LN8 5NJ SALES@THORNE.CO.UK +44(0)1673 858555 SCOTLAND NEWBURGH IND. ESTATE, NEWBURGH, FIFE, KY14 6HA SCOTLAND@THORNE.CO.UK +44(0)1337 842596 WINDSOR OAKLEY GREEN FARM, WINDSOR, SL4 4PZ WINDSOR@THORNE.CO.UK +44(0)1753 830256 STOCKBRIDGE CHILBOLTON DOWN FARM,

SO20 6BU STOCKBRIDGE@THORNE.CO.UK +44(0)1264 810916 DEVON QUINCE HONEY FARM, SOUTH MOLTON, EX36 3RD DEVON@THORNE.CO.UK +44(0)1769 573086

OVER

HAMPSHIRE,

TOP BAR HIVE

Editor John Phipps - editor@naturalbee.buzz Neochori, Agios Nikolaos, Messinias, 24022 Sub Editor Val Phipps Publishers/Advertising Natural Bee Husbandry is published four times a year by Northern Bee Books, a trading name of Peacock Press Ltd. Email jerry@northernbeebooks.co.uk Tel +44 (0) 1422 882751 Magazine Design www.SiPat.co.uk Printing Custom Print Limited, Liverpool, UK ISSN 2632-3583 John & Val Phipps Editor & Sub Editor Martin

Assistant Editor Contents NBH The Bees for Development Team Nicola

Helen

Janet Lowore Natural Bee Husbandry magazine In partnership with Bees for Development Journal No 145 with support from IBRA Editorials Early Pioneers of Sustainable Beekeeping in the UK John Phipps, Greece 4 Bees for Development Journal 145 BfD Nicola Bradbear, UK 5 Articles Nature-based Beekeeping - issues arising BfD Janet Lowore PhD, UK 6 The Scientist and the Beekeeper: The Tale of Varroa-resistance in Norway, Part One Dr Melissa Oddie, Norway 8 Stories from Under The Mango Tree Society, India Debika Chatterjee, Senior Programme Manager, India 11 Ensuring women benefit from bees BfD Isaac Mbroh, Apiculture Development Coordinator, Bees for Development Ghana 20 Beekeeping with Stingless Bees in Vietnam BfD Nguyen Huu Truc and Nguyen Quang Tan, Jichi Stingless Bee Farm, Vietnam 23 Diversity in Honey Bees BfD Jonathan Vincent, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe 25 Swarms Are Precious: Why Not Try a Bait Hive and See What Happens? Ron Brown, MBE 25 Waiting for the Bees Simon Ferris, UK 26 Aspects of Traditional Beekeeping, Yesterday and Today, in Lithuania Simona Vatinaite, Lithuania 27 Looking Back: The Catenary Hive Bill Bielby, UK, and John Phipps, Greece 31 A Scientific Note on the Strategy of Wax Collection as Rare Behaviour of Apis mellifera Krzysztof Olszewski, Piotra Dziechciarz, Mariusz Trytek and Grzegorz Borsuk, Poland 39 Book reviews Honey Bees Ingo Arndt & Jurgen Tautz 36 A Guide to the Safe Removal of Honey Bee Colonies from Buildings Clive A Stewart & Stuart A Roberts 36 Beekeeping Simplified with the Drayton Hive Andrew Bax37 Manual de buenas prácticas en alimentación de abejas (Manual of Good Practice in Bee Feeding) BfD Cecilia B Dini y Noberto Garcia 38 News, events and courses BfD Bees for Development 42

Kunz

Bradbear

Jackson

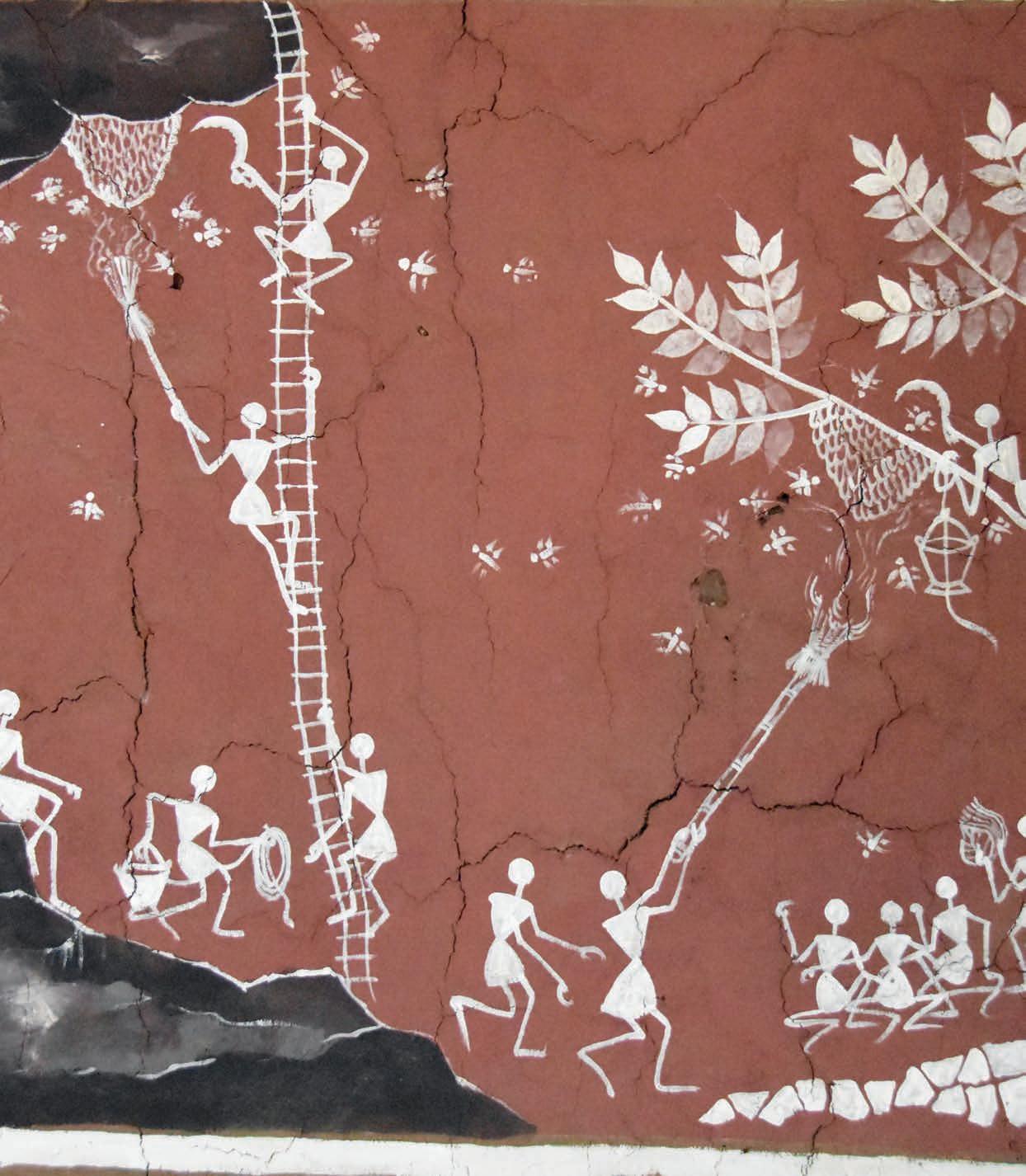

Cover photo: Artwork from Under The Mango Tree Society, India.

John Phipps, Editor, Natural Bee Husbandy magazine

Whilst today the popularity of sustainable and bee-friendly beekeeping is widespread, I have often wondered how, where and when this particular trend really began, especially since both groups as well as individuals participate in this way of involving themselves with bees: it occurs in so many parts of the developed world.

My own beekeeping began over fifty years ago in a typical way; attending a course, buying bees from the company that provided free tuition over three days, and then following the management procedures I had learnt for a few years.

However, I soon became aware that so many of the practices I put in place were contrary to what the bees wanted - and ultimately it was the bees themselves that decided what to do.

Someone then told me to read less about managing bees and read books about bees. Not only did I do that, but enrolled in a correspondence course run by the BBKA, with Mildred Bindley as my course tutor. Through her I came to know the works of Butler, von Frisch, Ribband and Lindauer as well as Dade on anatomy, and since then I have studied the works of those who came after such prestigious people.

However, I wanted more from beekeeping than just producing honey. I can’t quite remember how it occurred, but it was through meeting Beowulf Cooper in the mid-seventies and then editing both BIBBA News and The Bee Breeder until the early eighties.

As part of Beowulf’s main concern, which was to raise the profile of the British Black bee, he made trips to Northern Germany as well as organizing conferences there, so that more could be learned about the old races of black European bees. These, despite people’s denials, still existed in small pockets in the UK and were very common too in Germany, especially amongst heather beekeepers.

Beowulf regularly sent me postcards from Germany, in which he wrote enthusiastically about skep beekeeping, seeing skeps as an important tool in re-establishing British bees. It had all the requirements; the right volume for native bees, excellent insulation, and was cheap and relatively easy to make. Out of this interest arose one of BIBBA’s most interesting publications of that time, ‘Make Your Own Skep - and Revive a Lost Art’ by Rev E Nobbs (this was reprinted in full in NBH No 11, May 2019).

Whilst Beowulf was keen on promoting skeps, at the same time Bill Bielby, the Beekeeping Advisor for North Yorkshire, produced the Catenary Hive, which embodies many of the principles of NBH today. It allowed bees to build combs freely on top bars, the shape and volume of the brood area allowed the bees to make nests similar to those that they could make in the wild, and the entrance was midway on the front of the hive and just a single round hole. The most notable disadvantage though was the thinness of the hive walls, though this could be easily be improved by using thicker timber and plenty of insulation. A full description of this hive is in Bielby’s book, ‘Home Honey Production’.

Bielby was a member of BIBBA and was delighted to have a native strain of bees in his apiary at Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire. I spent a fascinating day with Beowulf Cooper and Bill Bielby at Spurn Point on the Humber, when prepa-

rations were being made for an isolated queen breeding apiary for native bees.

The other main development also at that time was Ron Brown’s Kenyan Top Bar Hive, which he had first used during his time abroad, finding it to be an economic and easy way of keeping bees, with the advantage that honey bees could build their combs without the restriction of having to use frames in the hives. It is interesting that the top bar has become more prominent over the years, but I have yet to fully understand why so many beekeepers use long hives which need frames. I strongly believe, too, that all those who count themselves as ‘bee-friendly’ should ensure that the homes which they provide for bees should be made from natural, sustainable and fully-recyclable materials.

Having seen a naturally-built colony in a hedge, I have always believed that bees should not be confined to hives designed for beekeepers and not for the needs of bees.

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 4 Editorial

Top: postcards from Germany sent to me by Beowulf Cooper; Left: my first sight of a swarm that had built its nest in a hedge; Right: meeting at Spurn Point on a wild autumn day. Left to right: Reg Birch, Beowulf Cooper, Bill Bielby and Don Appleton.

Nicola Bradbear, Bees for Development

Dear Friends

Bees for Development is thirty years old this year and we are celebrating! We are reflecting, too, on what we have achieved and what differences we have made, for bees, and for the people we have helped to care for them. When we set out (and there was just Helen and I in those days), we knew that beekeeping worked very well as a way for rural people to create food for their family and community, and income also. And in poor areas, people were keeping bees in the same ways that had been done for generations – with healthy bee populations and using skills and methods that had stood the test of time.

Bees for Development set to work in 1993 with dual aims: to reduce poverty, and to increase biodiversity. Back in those days, quite a few folk suggested that we should not use the word biodiversity, because ‘nobody knows what it means’. We used it anyway, because no other term adequately captures the concept of biological diversity: all the variety and variability of life on earth. Bees are of course our speciality, however we are using them as a means to interest and incentivise people to care for their surrounding habitat –because if they get that habitat right for their bees, they get it right for everything else.

Bees have moved up the human - interest agenda since 1993, and nowadays it’s not just bees but all insect pollinators that have gained public awareness. The climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis are no longer treated as separate issues: it is now accepted that there is no viable route to limiting global warming to 1.5°C without protecting and restoring nature. Beekeeping remains a feasible way for many people to create income while doing their bit to restore their surrounding habitat too, and we are making even more effort to ensure that happens over our next thirty years!

About Bees for Development Journal

ISSN number 1477-6588

Bees for Development works to assist beekeepers in developing nations. Produced quarterly, we have readers in 128 countries.

Editor: Nicola Bradbear MBE PhD; Coordinator: Helen Jackson BSc. Subscriptions: £30 per year. Pay online at www.shop. beesfordevelopment.org or email info@beesfordevelopment.org

Bees for Development gratefully acknowledge: ADM, Bees for Development North America, Charles Hayward Foundation, E H Thorne (Beehives) Ltd, Healing Herbs, Hiscox Foundation, Incubeta, John Paul Mitchell Systems, Rowse Honey Ltd, Yasaeng Beekeeping Supplies and many other generous people and organisations.

Copyright: You are welcome to translate and/or reproduce items appearing in Bees for Development Journal as part of our Information Service. Permission is given on the understanding that the Journal and author(s) are acknowledged, our contact details are provided in full, and you send us a copy of the item or the website address where it is used.

Address: Bees for Development, 1 Agincourt Street, Monmouth NP25 3DZ, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1600 714848

Email: info@beesfordevelopment.org

Web: www.beesfordevelopment.org

When pollination turns fatal

Biodiversity is declining faster than at any time in human history, yet we know so little of the amazing life that surrounds us. The famous Australian wildlife photographer, Rudie Kuiter, has permitted us to use his astounding photograph showing pollination turning fatal. The miner bee Lasioglossum lanarium was visiting the blue flowers of the great sun orchid Thelymitra aristata when she was caught by a green lynx spider (possibly the species Tharrhalea prasine). Note that the bee had made a previous visit to one of the orchid's flowers before it died, based on what she is carrying. You can see the orchid's pollinarium attached to the dorsal side of her abdomen. That is typical of pollination in most sun orchids with blue flowers. The column hood of the flower (not quite visible in this photo but upper left to spider's white abdomen) mimics a tuft of pollen-rich anthers, and the bee curls her abdomen around the hood to "shake out the pollen." When she unhooks her abdomen, it hits the viscidium on the rostellum lobe of the stigma. The bee yanks out the pollinarium and flies away with it attached to her butt. Note that one of the pollen sacs has started to rupture and is leaking pollen fragments.

Rudie gave us permission to share this photo which he took at Crib Point, a reserve in Victoria, Austrialia. Rudie Kuiter's fourth edition of Orchid Pollinators of Victoria is still in print.

Editorial 5

Above: Our latest cover picture on Bees for Development Journal No. 145, perfectly illustrates the biodiversity we seek to maintain.

B fD article

Editorial

Nature-based Beekeepingissues arising

Janet Lowore PhD, Programme Manager at Bees for Development

Why does Bees for Development particularly advocate Nature-based Beekeeping in developing nations?

Put simply, Nature-based Beekeeping systems are accessible to many people who need to earn a living from bees, because Nature-based Beekeeping relies more strongly on freely available natural materials and natural processes, and less heavily on capital. For people living in poverty, lack of capital is a huge barrier to participation, both to beekeeping, as well as to many other potentially lucrative livelihood activities. However, our reasons are far more complicated than that!

In the previous joint edition of Bees for Development Journal and Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine, we presented our case for Nature-based Beekeeping. In addition to that article, we are preparing a short video explaining this approach. We are currently testing the video with a range of stakeholders, to gain their feedback, and in this and subsequent articles we will address some of the most interesting and challenging feedback points we have received, concerning our article and the video. Comments we have received:

Please explain why ‘modern’ hives do not work. You tell us about the advantages of traditional hives, but you do not explain why countries which rely most heavily on traditional hives are not amongst the top honey producers in the world.

Why do frame hives fail in remote areas?

How can local-style methods be improved?

Does the clay and cow dung mixture used to smear basket hives contaminate the honey and beeswax? Does honey harvested from local-style hives meet international quality standards?

I would like to see more evidence of Nature-based Beekeeping working at scale.

In this article, Janet will address the first feedback point, i.e., why we say that ‘modern’ hives do not work.

Let us first examine the wording of the comment. Use of the term modern for bee hives is inappropriate: no serious discussion about beekeeping technology should use the term ‘modern’, which is imprecise and subjective. It hints, imperfectly, at when a particular hive was invented rather than describing its design features. And when something was invented has little bearing on its suitability for the context. It is much better to describe a beehive by its design features. Please let us describe bee hives by their design (or designer). It is for these same reasons that we do not use the term traditional – as this term also refers to a time or culture, rather than design feature.

Why do ‘modern’ hives not work? Of course they do work – according to what beekeepers want in some places, yet they are not suitable for all bees or all situations.

All beehives – be they top-bar, frame, horizontal, vertical, made of sawn wood, hewn wood or straw – have pros and cons. There can be no such thing as the ‘perfect’ beehive because bees differ in their biology and behaviour and people have differing requirements, preferences and resources available to them.

Just think about the innovative Flow Hive – clever design yes, but not suitable for everyone, everywhere. The suitability of a beehive for any given situation – is determined by social, cultural, economic and ecological criteria, with some beehive types working best in some circumstances and some in others. Frame hives have been given, pushed, donated, promoted, sanctioned and encouraged across rural Africa – yet adoption rates remain low. There are multiple, interacting reasons for these low adoption rates and it would serve the industry well if we unravelled and understood these reasons, rather than blindly pushing a technology where it is ill-suited – and wasting a lot of money.

Frame hives are ingenious, yet they are not perfect in every circumstance. Think about other technologies. In some places radio is a better medium for transmitting information than TV, why? In some places motorbikes are better means of transport than saloon cars, why? In some places, solar-powered irrigation pumps are better than petrol engine powered irrigation pumps, why?

So, let us ask this question properly. Why, despite being donated in their millions in developing countries are frame hives not well adopted by beekeepers? The reasons are not the same everywhere and they intersect – so writing a simple list is just not possible. In this article we can only begin to answer:

Economic reasons

One simple explanation is that frame hives are too expensive. If a poor person has a spare US $50 they will have many more pressing and rationale expenditures to make than buying a frame hive. Poor people do not have the luxury of spending to accumulate – they need to buy food, school uniforms, medicines, fertiliser, to fix the roof, to pay taxes, to buy tools. And if they did have the luxury of spending to accumulate there are many more accessible, less risky and more profitable ways of spending US$ 50 than on a frame hive. Buying tomatoes where they are cheap and selling them in town, making and selling food on market day, becoming a mobile phone credit vendor or buying some tools and fixing bicycles. All easier ways of turning a profit on US$ 50. Spending money on frame hives is something rich people might do because they can afford it and can afford to take the risk. They might get their money back, they might not. A poor person just will not do this.

Please note that ‘not spending money on a frame hive’ is not the same as ‘not investing in beekeeping’. A poor person can very easily invest in beekeeping for nothing at all. By making their own hive using locally available cheap or free materials.

Some people have been spared the need to buy a frame hive by being given one – but in interests of reaching more people, most donor-funded projects would rather give one hive each to ten people, than ten hives to one person. We have seen countless examples of donor-funded projects trying hard to reach even more people by donating hives to groups –a group of twenty people being given ten hives. Not enough!!! One beehive (let alone half a beehive) is never enough.

6 Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145

B fD article

The argument that a person can make enough money from their one donated hive to buy another one is flawed. It does not happen! If your average poor person (we will generalise for a moment) is given one frame hive and is fortunate enough to make US$ 50 profit in their first year of beekeeping – what are they going to spend this US$ 50 on? Those items mentioned above or many, many other alternatives before a frame hive. And this assumes that they make US$ 50. There are many reasons why this might not happen at all. So in summary most of the rural poor cannot afford to buy frame hives, and those that receive them in donations use them, and may or may not earn from them, but are extremely unlikely to buy another one. They are just too expensive given (a) there are other less risky things you can spend US$ 50 on and (b) there are cheaper way to invest in beekeeping. So frame hives are not widely adopted because of economic reasons.

Economic reasons are only the beginning of the story. In this article we touched on some further ideas and assumptions – we mentioned risk and we mentioned that a person who receives a frame hive as a donation, might not make much money from it at all. Why not?

I certainly agree with the comments above, understanding that an essential part of Bees for Development’s work is to aid the economy of the groups with which it is involved; however, there are other issues which they hope to address in future editions of the magazine. As for Natural Bee Husbandry’s aims, economy is not likely to be a problem. The focus is on supplying bees with sustainable homes that adequately meet the colony’s full needs as nature intended, and which since the dawn of time have allowed them to survive with little interference from man. This being the case, the hives adopted for use in the developed world have been influenced by several of those that have been promoted by Bees for Development in their programmes, as well, of course, those from previous centuries within each of their own geographic regions.

Some of the most important principles of sustainable and bee-friendly beekeeping

Bees able to build their combs in the most natural way as possible

Homes provided for bees are of the right volume, weatherproof, give protection from enemies, and well-insulated from extremes of heat and cold

Homes able to be made easily and cheaply from natural, sustainable materials, preferably found locally

Bees interfered with as little as possible

Bees not treated with chemical agents against pests and diseases

Plenty of natural stores are left for the colonies so that they can survive during droughts and winters

The first time I saw a colony in the wild with its beautifully constructed nest, I always considered it to be a shame that bees are confined within frames in modern hives and not allowed to build the nest in the ways they have for millennia.

Given a chance, a gap between frames, will allow the beekeepers see how well comb can be constructed when the bees are given the freedom to do so.

A skep: an ideal home for bees for thousands of years. If given shelter from adverse weather conditions, the colonies within them should thrive.

Story 7

B fD article

Top bar-hives allow the bees to produce beautiful combs which can also be removed easily from the hive if need be.

All photos John Phipps

The Scientist and the Beekeeper: The Tale of Varroa-resistance in Norway

Dr. Melissa Oddie

Part One

I remember first reading about Varroa destructor. It was portrayed as this apocalyptic plague that had descended on the world’s honey bees, spreading disease, and killing colonies at such a rate that beekeepers were throwing up their hands, walking away from a life-long passion because they could not take the crushing pressure. I read this, but I also read about the people fighting to control it: novel treatments, using mite predators, new management techniques, but the method that struck me the most was naturally-adapted mite resistance; using evolution to fight a problem that evolution had helped create.

My first trip to Norway was in 2015, about five months into my PhD. The work was on varroa resistance in European honeybees: resistance, in my mind, is the ability of honeybees to adapt and employ techniques to reduce mite population growth, rather than tolerate high loads. This method struck me because, like graduates of any Ecology and Evolution program, I had learned about the Red Queen Hypothesis: the arms race of adaption between two competing species. It seemed a self-adjusting strategy, to have bees adapt and manage the parasite. They would achieve a sort of dynamic equilibrium with it, living in a balanced push and pull for as long as nature saw fit. This would effectively prevent the catastrophic losses so many beekeepers were now fighting.

The roads were pitch black as I drove my rental, with no lights save my own, and the black silhouettes of the towering spruce crowding on both sides against a deep navy sky. It was about 10 pm one night in August and I was hopelessly lost; both geographically and apiculturally. Everything I had learned about bees up until that point, I had crammed in about four months, reading scientific papers and beekeeping blog - as many as I could.

Top: Terje and Melissa sit at the famous kitchen table discussing the results from the year 2021. Above: The experimental apiary used during the scientific studies from 2020-2022, set up by Terje and Melissa.

Prior to this, I knew no more than any non-bee-associated person would. So, when I was sent to investigate Terje Reinertsen’s alleged “varroa-surviving” Buckfast bees, I held a healthy level of skepticism in the claim. The literature said that European honeybees died of varroa, and that was that. I almost did not find the house. Terje and his wife, Anita, had graciously said that I could stay in their spare room while I ran my observations. As luck would have it, I stopped to ask for directions at the very house I was supposed to find! Anita opened the door, invited me inside, and so begins the story.

Terje Reinertsen is a very typical beekeeper outwardly, with greying hair, a snowy white beard, a back bent from work and the kindest smile you would ever see, but I only needed to speak with him on a few occasions to know that his powers of observation were extraordinary. Terje noticed things about the bees most others would not. Each morning we would rise at the same time, while his wife still slept, and we would share breakfast and a conversation. Then, he would start his bee work and I would drive to my host institution to prepare my experiments. The words we exchanged at

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 8

that kitchen table revolutionized my understanding of honey bees, because prior to that, they had been resigned to concepts of ink on paper, beyond the occasional forager that floated distantly past my office window. I did not know them, but Terje did.

Mornings became routine: Terje would share his theories on the bees, what they were doing and why, and I absorbed everything, cross-referencing it with the textbook learning I

had memorized before my trip. It gave me an appreciation for both perspectives, academic and experimental, and taught me the value of each: beekeepers observe, and they often do it well, so they catch things not yet described or explained by research, and research gives a crucial context to many of the beekeepers’ observations.

On days when there were no research tasks, I opted to shadow Terje as he worked with his bees, watching,

learning, and working firsthand. I quickly became aware that Terje had such a keen understanding of them that, even though it was difficult to communicate, he could be relied upon to an astounding accuracy: bees were all about balance. If something was off, they reacted, adjusting their behaviour to return the colony to their version of normal. They were absorbing information I could only guess at, but Terje seemed to know what each response meant and what had caused it: the brood pattern was off, or they were not building drones where they should. Everything at every time in the season had a different reason and I slowly realized that forty years was a rather tight time limit to learn what Terje seemed to know.

The first measurements I took, counting varroa on the bottom boards of the colonies told a very interestng story; indeed, it seemed that a good number of Terje’s colonies had a much lower drop rate than expected, consistently over several measurements, and this was in autumn, when varroa would notoriously take over. So, there was some evidence for the “surviving” claim, but I still wasn’t convinced. The next bit of evidence came in the brood - because I suspected the lack of mites would continue there, I did not use brood frames in which eggs had been laid and capped by Terje’s own bees, but frames from other colonies that had a measurable issue with the mites. Each of ten colonies were given two capped frames, one of which was set into one of Terje’s colonies, and one into a local Carniolan colony with no reported resistance, and very clear mite evidence. Each of the five receiver colonies of both population types (Terje’s or Carniolan) got two frames from different donor colonies. The frames were removed after about nine days and since the brood used was laid in a specific time window, I knew most of the cell occupants would be about nine days old after capping, the perfect time to measure reproductive success in the mites. Terje’s bees did not disappoint. In that nine-day window they seemingly managed to influence the varroa reproductive rates, reducing the reproductive success on average by 30%, despite the mites coming from the same donor colonies in an apiary over fifty km away.

Now, cell recapping is what I have published most on besides the ability of Terje’s bees to reduce the reproductive success of varroa. It is, simply put, a

9 The Scientist and the Beekeeper: The Tale of Varroa-resistance in Norway

Top: A capped brood frame in one of Terje's surviving colonies. Central in the photograph is a cell with an open cap to reveal the little hole made by the bees that has been capped back over with wax.

Above: From left to right: Terje, Frank, Roar and Melissa crowd into the small grafting room in Terje's workshop.

hygienic behaviour that exists in every colony, used to detect problems with and remove diseased brood. Where varroa is concerned, it seems highly associated with colonies that can reduce the population growth of the parasite. I did not discover this association in relation to varroa. I first read about it in one paper from the Baton Rouge lab in Louisiana: “Changes in Infestation, Cell Cap Condition, and Reproductive Status of Varroa destructor (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) in Brood Exposed to Honey Bees With Varroa Sensitive Hygiene” (1). It remarked that the bees opening a cell and capping back it over with wax was a by-product of complete brood removal in response to varroa invading and/or reproducing in brood cells. In the case of recapping, the brood is not removed, only the cell cap is opened, partly or completely, and then the hole is repaired, often by another bee. The brood remains undisturbed, to develop as it would normally. A simple recapping would not prevent the mite from reproducing, if it chose to remain in the cell, but it is possible that simply opening the cell may create enough of a disturbance to reduce the number of offspring a female is capable of rearing successfully, especially if the cell is opened more than once.

At this point, I had solid evidence that varroa numbers were lower and that their reproduction was being actively affected by something Terje’s bees were doing, but no method was yet apparent. I was tasked with measuring brood removal, or, VSH in my original experimental design that year, but to my chagrin, I found no difference between Terje’s bees and my controls in the number of brood cells missing from the test frames (which had been carefully photographed and

mapped before and after the nine-day rearing period). Nor did they seem to be grooming themselves at any higher rate, at least, not in the month-long time window I was given (2).

I still believe it is possible that the bees could have been changing their varroa management tactics across a year, and I simply missed them, so VSH and grooming may play a role in survivability, and re-capping may just be a by-product after all, but back then, sitting in the tiny lab late one cool, August night, with three weeks gone and no evidence of any real mechanism for the difference in varroa I was measuring, I was at a loss. It was then I began to question everything I had been doing; there was something there, I had missed it and by then it was far too late to re-design and run any more experiments.

That was when I noticed it: a small discolouration in the cell cap on one of the frames given to Terje’s bees, and I thought back to that paper. Carefully, I excised the cap like one would open a can and turned it over - the cell had been opened before, but not by me, by the bees. Now that I had seen it once, I found it everywhere; in some colonies the rates were modest, in some, nearly every infested cell had been tampered with, but the key thing was it was only in the brood that had been given to Terje’s bees. The control frames were lucky to have two re-capped cells in 200. This was something, perhaps my life choices could be salvaged! At that point in the night, I heard a loud bang, and suddenly the hallway was flooded with water. One of the pipes in the automated coffee machine had burst, sending a solid jet squirting straight out from the break corner. I spent the next ten minutes splashing about, trying to

find a wrench to shut the water off and then rescue my (now precious) brood samples from a soggy end.

I published a few times after that data. Terje’s colonies never disappointed me with their evidence of varroa survivability, no matter how many seasons of data I took. One notable publication in 2018 mentioned re-capping found in Norway and three other, scientifically-backed surviving honeybee populations in Europe (3). Since then, more researchers have begun to talk about re-capping, if not as an actual mechanism of varroa resistance, then at least an easily measurable proxy one can use to gauge a colony’s ability to survive. What happened concurrently in Norway was, in my mind, much more interesting. Terje and his ideas of breeding bees that did not require treatment was gaining traction, and my research served to support it. People were taking notice, they wanted to try it too and it was not long before national funding was granted to try and repeat Terje’s breeding efforts, but this time with a scientist heading and recording the process. They chose me.

To be continued in the next issue: May 2023.

References

(1) Harris J. W., Danka, R. G., & Villa, J. D. (2012). Changes in infestation, cell cap condition, and reproductive status of Varroa destructor (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) in brood exposed to honey bees with Varroa sensitive hygiene. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 105(3), 512-518.

(2) Oddie M. A., Dahle, B., & Neumann, P. (2017). Norwegian honey bees surviving Varroa destructor mite infestations by means of natural selection. PeerJ, 5, e3956. (3) Oddie, M., Büchler, R., Dahle, B., Kovacic, M., Le Conte, Y., Locke, B., ... & Neumann, P. (2018). Rapid parallel evolu.on overcomes global honey bee parasite. Scien.fic reports, 8(1), 1-9.

Beekeeping Today Podcast

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 10

With U.S. beekeeper hosts Kim Flottum & Jeff Ott. Hear the latest beekeeping science, news, education and personalities from around the world! And check out the latest episode including 5+ years of content and a new blog series, "Beekeeping and Climate Change" by Kim Flottum, starting February 2023. Find us at www.beekeepingtodaypodcast.com

Of Bees and Beyond: Stories from Under The Mango Tree Society, India

Debika Chatterjee, Senior Programme Manager, Under The Mango Tree Society - www.utmtsociety.org

Under The Mango Tree Society (UTMTS) is an award-winning not-for-profit organisation in India, that offers beekeeping with indigenous bees to tribal farmers for enhancing their agriculture through improved pollination. It started in 2009 with the vision of providing beekeeping as an agricultural input to small and marginal farmers*, to increase their crop yields and income, protecting and enhancing the local population of indigenous honey bees by creating awareness in the local communities about their role as ecosystem service providers, and encouraging beekeepers to adopt bee-friendly agriculture practices. The beekeeping programme of UTMT Society expanded over the years to include income enhancing opportunities along the beekeeping value chain, such as the setting up of micro enterprises that specialised in beekeeping inputs and enrolling local trainers and other service providers to support beekeepers. Since then, UTMT Society has received several awards and accolades, including the World Bank Award in 2013 and the HCL Foundation Award in 2020. Currently, it has presence in around 300 villages in 14 districts in the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh.

Even as the organisation has progressed in leaps and bounds, the Society is focussed on working with Indigenous Bees, primarily the Apis

cerana indica and stingless bees, to improve pollination cover for smallholder agriculture. Beekeeping with the local indigenous bee is well suited to the diversified farming systems found in tribal communities. Input costs are low because the bee is locally available (wild hives are domesticated) and resilient (little need for antibiotics). Since the bees are well adapted to the local environment, they subsist on existing flora without needing to migrate the boxes, as is required for A.mellifera. So, even when A.cerana is less productive in making honey than its European cousin, it is an excellent pollinator. Some of the key impacts of UTMT Society’s work have been:

1) Reduction in unsustainable honeyhunting practises

2) Increase in crop production

3) Creating other sources of livelihood generation

4) Diversified agriculture

5) Increased green-cover and biodiversity

Reduction in unsustainable honey-hunting

Honey-hunting is the method of extracting honey from bee hives found in the wild, and it mostly involves killing bees residing in colonies in the wild so as to obtain combs containing honey and brood (larvae & pupae). In

rural communities, honey hunting still remains an integral way of collecting honey, as the hunters are unaware of the consequences of destroying bees and their habitats. Through awareness programmes, UTMT Society informs and explains how bees help in pollination and how pollination is crucial for agriculture and maintaining the biodiversity of the surrounding forests.

“Being a traditional honey hunter, every year I used to destroy around 5-7 bee colonies for honey. I have stopped it completely now”, shares Prafulbhai Bagul, a 32-year-old beekeeper from the Dangs district in Gujarat. Now his perception has shifted from ‘bees for honey’ to ‘bees for pollination’. He also actively participates in sensitizing others in his community about bees, beekeeping and how it impacts our environment.

Similarly, Kaliram Rajbhopa, from the Chhindwara district in Madhya Pradesh, used to be a traditional honeyhunter. He says “I had no idea that Cerana bees can be domesticated, and unknowingly I have destroyed so many hives in the past. I was amazed to learn about the benefits of beekeeping during the beekeeping training”.

Increase in crop-production

Despite being life-long farmers, a lot of the small and marginal farmers do not understand the concept of pollination. One of the things that is explained in great detail during the two-day basic

11 Of Bees and Beyond: Stories from Under The Mango Tree Society

Women beekeepers in a village in western India catching Cerana swarms

*Marginal Farmers are those who cultivate on less than 1 hectare (2.5 acres) of land by definition in India, and Small Farmers are those who cultivate on less than 2 hectares (5 acres) of land. They make up almost 85% of the farming community in India. They are mostly “subsistence farmers” and only if there is extra produce, they sell it in the local market.

beekeeping training offered by UTMT Society, is how bees pollinate flowers to form fruits. Before the training, most of the farmers link bees only to honey, but later there has been a sea change in their attitude towards bees and also towards the entire environment.

Ajaybhai Kokani, a 27-year-old beekeeper, from the Halmundi village in Tapi district of Gujarat, farms on two acres of agricultural land, which earns him an annual income of Rs 80,000. Trained in 2020, he currently has three filled bee boxes in his farm. He was pleasantly surprised to see the increase in the harvest quantity of Mango and Watermelon post beekeeping. Previously he used to harvest 1400 kg of Watermelon by sowing one kg of seeds, but after beekeeping he harvested 2000 kg of Watermelon. Bhabhut Kayda, a beekeeper from Charkheda village, in the Chhindwara district of Madhya Pradesh is now keen to preserve indigenous bees and promote beekeeping among other villagers. He says “My work has helped me understand that conserving the bee population is a local solution to our ever-pressing problem of decline in agricultural productivity”. He thinks that the beekeeping training programme made it easy for farmers like him to bring the bees to their farms. He now correlates better produce with the greater number of bees in his farm. Bhabhut Kayda explains, “I was able to earn Rs 15,000 additionally from the sale of surpluses of Chickpeas and Peas this year, after I placed filled bee boxes on my agricultural land. Post placing the bee boxes, I was able to harvest 90 kg of Chickpea, which was only 40 kg before beekeeping, even though I used the same quantity of seeds and other inputs. Also, the size of grains of both Chickpeas and Peas were bigger, which fetched me good price when I sold in market locally. I am very happy that I am a beekeeper”.

Creating other sources of livelihood generation

UTMT Society also impacts the local community by developing micro-enterprises as part of the beekeeping input-supply chain, which in turn contributes to the livelihoods of local people. Micro-enterprises associated with beekeeping have led to new livelihoods, like womens’ Self Help Groups and local carpenters making and selling beekeeping-related inputs. The villagers trained in carpentry are taught how to make bee boxes within

the village, so that the beekeepers can purchase the resources directly from them and at a much lower price, since there is no transportation cost involved. It has also helped the local carpenter in generating extra income. For example, a carpenter from the Tuterkhed village, in Dharampur block in Valsad, Gujarat says, “The scope of carpentry work was limited in the village so we had to migrate outside for work as unskilled labourers in workshops as we lacked advanced skills and had no equipment. But with the establishment of the carpentry unit, a local avenue for livelihood has been created.”

Another such avenue of livelihood generation has been through bee-veil and swarm-bag Womens’ Self Help Groups (WSHGs), where women are trained in making bee-veils and swarmbags in tailoring workshops organised by the Society. In some places UTMT Society has helped the local women set up beeflora nursery WSHGs, where saplings of bee-friendly indigenous plants are grown and sold to the villagers.

Diversified agriculture

UTMT Society’s beekeeping programme has also encouraged farmers to not limit their agriculture to monsoon crops, but also take up winter cropping through its beeflora intervention (wherein the seeds and saplings are provided to farmers at 50% contribution). Some of the seeds commonly distributed are that of Chilli, Bottle gourd, Sponge gourd, Ladies finger, Sunhemp, Brinjal, Sesame, etc., which has resulted in a number of farmers expanding their agriculture beyond subsistence farming.

Increased green cover and biodiversity

Saplings of indigenous trees, planted as part of the beeflora initiative, improve the green cover of the area. Longterm trees, such as Jamun (Java plum), Drumstick, Apple Jujube, Indian Gooseberry, Litchi, Lemon and Guava provide nectar and pollen for the bees, while also improving the green cover of that area. Some of these flowers also serve as pasturage for other types of pollinators and flower visitors from various insect orders.

We can safely say that beekeeping is an activity that not only tackles hunger and poverty at grassroots level, but also addresses inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, and biodiversity enhancement. UTMT Society’s ‘Bees for Poverty Reduction’ (BPR) programme addresses ten of the twenty SDGs by offering beekeeping with indigenous bees and flora enhancement measures to tribal populations practicing agriculture in some of the most backward areas of the country.

Can you name the 10 SDGs we are talking about?

Follow Us or Tag Us at:

Facebook: /utmtsociety

Instagram: /utmt.society

Twitter: @societyutmt

Linkedin: /company/utmtsociety

Youtube: /utmtsociety

12 Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145

A locally-made Cerana beebox

Top and above: Naturally occurring cerana colonies in the hollow of a tree and under an abandoned basket. Below: Colonies placed in hives made of mud which due to the climate are not very resilient.

Lack of trees

Summer in most of India lasts for 4 to 5 months and is very hot and dry. Drought-like conditions make crop production very difficult.

Building hives

Completed hives

Comb building

To prevent pests entering the hives the legs are placed in a tin of liquid

Examining hives & collecting swarms

Honey harvesting

Honey harvesting

Drought conditions make crop production difficult. Wells need to be very deep for water to be collected. All the water has to be carried from the well to the crops. Crops include: maize, beans and mangoes. The plants produce nectar and pollen for the bees, bees provide the pollination neccesary for seed and fruit production.

The state of Maharashtra faces drought like situation almost every year, because of climate change and fast depletion of ground water level.

Above left: Cashew, one of the key cash crops grown in Gujarat, gets greatly impacted by bees.

Above left: Kitchen garden planted during the summer months where the farmers use gray water for their plants. The produce is used for self-consumption. (Maharashtra); below left: Collecting data about agriculture production. (Gujarat)

Above left: Cashew, one of the key cash crops grown in Gujarat, gets greatly impacted by bees.

Above left: Kitchen garden planted during the summer months where the farmers use gray water for their plants. The produce is used for self-consumption. (Maharashtra); below left: Collecting data about agriculture production. (Gujarat)

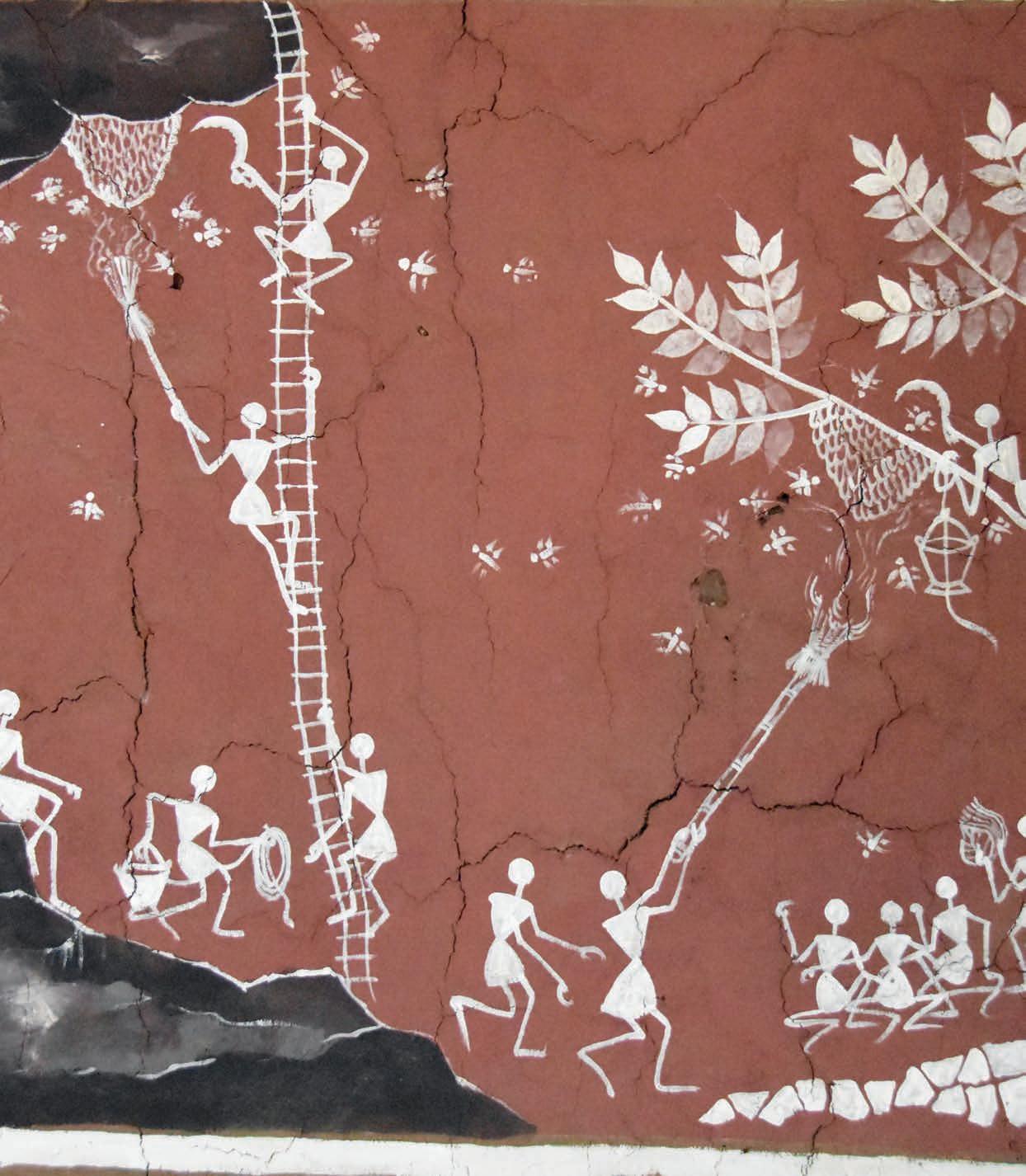

Above: This is Warli painting, a form of tribal art done by the Warli people in Maharashtra and Gujarat. The Warli culture is centered on the concept of Mother Nature and elements of nature are often focal points depicted in Warli painting.

Below: It is important that the bees are given appropriate shade during the hot season. One of the village UTMT training centres.

18 Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145

The young girl is holding indigenous variety of Brinjals.

Above: Beekeeping Resource Centre in a village in Maharashtra.

19 Of Bees and Beyond: Stories from Under The Mango Tree Society

Another village training centre with educational posters and examples of tribal art.

Ensuring women benefit from bees

Isaac Mbroh, Apiculture Development Coordinator, Bees for Development Ghana

Organisations are increasingly advocating for gender mainstreaming to ensure that they respond effectively to the needs of all citizens. Until recently, the involvement of women in beekeeping in Ghana was not common, and Bees for Development Ghana (BfD Ghana) has been championing this cause. Since 2015 we have been working very hard to encourage women’s involvement in our work.

Gender gap

Women in rural areas of Ghana have high illiteracy compared with men, and more limited capacity to access and adopt improved technologies – and most are very poor. Women own less land, have fewer assets and have low access to cash and credit, adding to their food insecurity. World-wide, only 15% of Agricultural Extension Agents are women, yet women are crucial for achieving food security, sustainable agriculture and rural livelihoods. Of seventy extension advisors in Ghana, only ten are female.

The beekeeping sector is highly skewed against womens’ participation, with less than 1% of beekeeper trainers being women (Bees for Development).

BfD Ghana is rolling out a new project in February 2023 to address this gap. We will train women who are unemployed to become professional beekeepers and trainers and ‘Bee the voice’ for the vulnerable in the society.

BfD Ghana’s experience

BfD Ghana has tried hard to address the gender imbalance – concerning both those practising beekeeping, and those who are trainers, leaders and change agents. Whilst trying to understand the reasons for low participation of women in beekeeping, we found that women were afraid of bees and of working at night. They could not climb trees, and keeping bees was considered a ‘man’s occupation’. Traditional ways of restricting women to domestic activities close to the homestead also serve as a hindrance to engaging in beekeeping.

Our experience suggests that these reasons mirror those given for limited access of women who keep bees in other parts of the world. However, women commonly make value-added products from honey and beeswax, and these products offer unique opportunities for womens’ traditional skills. Where work and childcare commitments constrain women to remain within or near their homes, value-added products can be an ideal opportunity for income generation. Male beekeepers are often not interested in this field, so it is not challenging to the cultural status quo.

Top-bar hive beekeeping offers advantages for female beekeepers because it moves away from traditional methods that may be seen as more ‘male orientated’. In West Africa, beekeepers do not have to climb trees to install hives. They make hive stands or use fork-like tree branches to hold hives in position in an apiary. Fixed comb hives such as Borassus log hives and basket hives which are low-cost and affordable, are promoted by BfD Ghana and are well accepted by both men and women.

Training workshops and womens’ participation

We closely monitor and evaluate our project work, and this enables us to make alterations when needed. Interactions with women in the Afram Plains reveal that, especially those in the Muslim communities, they find it difficult (or uncomfortable) to participate in our usual mixed training sessions, and that sourcing materials for hive-making was also a major challenge for these vulnerable women as it involves the cutting and lifting of materials like Borassus logs.

As a result, we revised our approach to accommodate these concerns by holding separate training workshops for women. The first all-women-workshops welcomed thirty-three women participants who were provided with sixty wooden fixed comb hives – which are cheaper than top-bar hives. We intend to extend this to other communities in the Afram Plains.

Even where women received materials and training in basic beekeeping, some said they sometimes depend on assistance from men for colony management, especially at night.

Gender mainstreaming success stories

Since 2019, BfD Ghana has been training honey-hunting communities – with a considerable number of women, living on the fringes of Digya National Park, keeping bees using local style, fixed-comb hives.

The results are amazing: Hawa Issah, a fifty-two-year-old woman who lives in Kojorbator, a small village on the fringe of Digya National Park, was named Best Beekeeper in the Kwahu Afram Plains North Awards in December 2021 during the National Farmers’ Day celebration. Hawa sometimes works

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 20

B fD article

Above: training for women beekeepers at Bondaso, Afram Plains. © Gideon Zegeh/BfD Ghana.

in her husband’s apiaries – doing colony management, harvesting and processing of honeycombs for honey and beeswax.

“Hawa is our star beekeeper” says BfD Ghana’s Director, Kwame Aidoo. We like her commitment and passion towards beekeeping.

Another success story is Lucy Benewaa, one of the many women supported to keep bees in their cashew orchards under BfD Ghana’s Cashew, Bees and Livelihoods Project. This leads to double benefits; farmers like

Lucy benefit from the pollinating activities of honey bees leading to increased cashew nut yields and from bee products - honey and beeswax.

Lucy is a sixty-four-year-old woman with five children who lives at Offuman in the Bono East Region. She started with two hives in 2017 and now has fifty. Lucy can select and prepare an apiary; make and bait hives, set them up in the apiary; manage colonies; harvest, process and sell honey and beeswax. She earned about GH₵8500 (US$800; €760) in 2021 and over GH₵10000 (US$943; €895) in 2022.

Lucy has benefited from keeping bees in the last five years — harvesting and selling more cashew nuts in addition to

Right: Hawa Issah with her beautiful beeswax. © Isaac Mbroh/BfD Ghana.

Right: Hawa Issah with her beautiful beeswax. © Isaac Mbroh/BfD Ghana.

Ensuring women benefit from

21

bees

Above: Lucy Benewaa and her husband with their beeswax.

Left: Lucy with one of her fifty hives. © Isaac Mbroh/BfD Ghana.

honey and the beeswax she gets from keeping bees from the same piece of land.

Sarah Fosua is doing well in the beekeeping industry. She started as an apprentice to one of BfD Ghana’s master beekeepers Stephen Adu. Currently, Sarah and her younger brother own fifteen hives, and all are occupied by bees. Sarah manages these fifteen colonies herself and has much passion for what she does.

Sarah does not see any barriers to beekeeping for women. She said, “To me, there are no barriers. Beekeeping is like any kind of work - once you make up your mind to do it you can. This is a normal, money-making venture and nothing can prevent me from keeping bees”. This is Sarah demonstrating her resilience to succeed in the beekeeping industry.

Naomi Ankomah, a forty-threeyear-old single mother with four children who lives in Bono Manso in the Bono East region, is another beneficiary of BfD Ghana’s Cashew, Bees and Livelihood project. Naomi manages five colonies. She harvests, processes, packages and sells her honey in 4.5 litre containers on the Techiman-Tamale highway, and also processes and sells beeswax. Naomi is a beekeeper in addition to her regular small-scale business of selling assorted food items by the roadside.

Although beekeeping is a ‘male dominated’ activity, men also face many management challenges, especially those who are beginner beekeepers. Both men and women can be equally afraid of bees.

Equal opportunity

BfD Ghana believes gender equality is necessary to ensure that women and men, and girls and boys have equal rights, opportunities, and respect.

We have gender-specific and disaggregated indicators for only women or only men that help them to measure differences between women and men in relation to each metric. This would not have been possible without efficient monitoring systems and dedicated staff who go to the field to measure these important indicators. The frequent evaluation of our programmes ensures that we are able to modify our work by closely monitoring their gender equality indicators that measure this directly or as a proxy for gender equality or equity.

BfD Ghana believes that by ensuring all the above, development organisations could be far more successful.

Women reached by BfD Ghana’s projects

Within the last six years, about one thousand people have benefited from BfD Ghana’s projects. Of this number, women who directly benefited are about 15%, from over forty communities across Ghana. According to the women who have participated, people have certain perceptions. People think that beekeeping is for men so why are women engaging in such a dangerous

References

and difficult livelihood activity? Despite the glaring challenges, we are resilient in championing this course and are resolved to make a huge impact.

Conclusion

We believe that there is much to be done to ensure gender and social inclusion, and in coming years we will be striving to increase the percentage of women who benefit directly from our work.

ADEBAYO,J.A.; WORTH,S.H. (2022). Women as Extension Advisors. Research in Globalization. 5. 100100. 10.1016/j. resglo.2022.100100; FAO (2008). International assessment of agricultural science and technology for development. https://www.grida.no/resources/6343; MANFRE,C.; RUBIN,D.;ALLEN,A.; SUMMERFIELD,G: COLVERSON,K.; AKEREDOLU,M. (2013). Reducing the gender gap in agricultural extension and advisory services: How to find the best fit for men and women farmers. Meas Brief, 2, 1-10; WORLD BANK. (2010). Gender and Governance in Rural Services. The World Bank.

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 22

B fD article

Naomi bottling honey into 4.5L containers for sale. © Kwame Aidoo/BfD Ghana.

Sarah Fosua installing a new hive for another beekeeper. © Stephen Adu/BfD Ghana.

Beekeeping with stingless bees in Vietnam

Nguyen Huu Truc and Nguyen Quang Tan, Jichi Stingless Bee Farm (Trai Ong Du Jichi), City of Phan Rang - Thap Cham, Phan Rang Province, Vietnam. www.OngDuJichi.com

Stingless bees are less well known than honey bees in Vietnam, yet they have an important role in pollination and honey production, and in recent years people have been more interested in these bees.

In nature, stingless bees build their nests in cavities such as tree hollows, rocks, or house walls. At our Jichi Stingless Bee Farm, we produce stingless beehives made of wood, decorated and painted in different colours. The hives are usually multiple boxes and the volume of each box is one litre because in our experience, this kind of hive is convenient for taking care of bees, collecting honey and multiplying the colonies.

At our farm we produce queen bees and multiply the stingless bee colonies. We sell hives, honey, and stingless bee colonies, and in addition, we provide pollination services and care of colonies after they have been sold.

We place several hives on farmland or in gardens for pollination and/or honey production. In a café, shop, or the backyard of a house we place one or two colonies for decoration, hobby or interest.

Stingless bees have received more interest and attention from the public in our area because they have advantages:

The bees are stingless therefore people are not afraid of them!

No feeding of stingless bee colonies is necessary.

The colonies rarely abscond. Swarm colonies usually do not go far from the mother colony.

Honey from stingless bees is considered superior and the price of stingless bee honey is higher than honey bee honey.

Stingless bees are tiny and lovely. Stingless bees are not attracted by the light from bulbs at night.

1: a colony from which honey is about to be harvested.

2/3: all boxes are made by us from wood and painted in different colours.

4/5: we place several hives on farmland or in gardens for pollination and/or honey production. In a café, shop, or the backyard of a house we place one or two colonies for decoration, hobby or interest.

23

Beekeeping with stingless bees in Vietnam

2 4 3 1 5 B fD article

The demand for honey and colonies of stingless bees in Vietnam is now growing. Currently, the price of honey is VND2,000,000 (US$80; €77) per litre and that of a double box bee colony is VND3,000,000 (US$120; €116). On average, a colony can provide one litre of honey per year and a colony can be multiplied into two colonies in one or two years.

With this article and pictures, we are happy to share the information of our stingless beekeeping and would like to hear about the knowledge and experience of colleagues in other parts of the world.

All images © Nguyen Quang Tan; except images 11–13 © Nguyen Huu Truc.

24 Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145

10: two boxes being separated; 11: stingless bee brood; 12: honey and pollen; 13: not afraid of getting stung because the bees are stingless!; 14: Nguyen Quang Tan and Nguyen Huu Truc

6 9 8 7 10 11 13 14 12 B fD article

6–9: The hives are kept inside a bee house with the entrances on the outside. The entrances are painted different colours and have a plastic tube attached to them.

Diversity in Honey Bees

Jonathan Vincent, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

We had a great start to the seasonal rains here in Bulawayo in November 2022. The bees are busy, and all my colonies have swarmed and are building up again. I had some good harvests last year and if the weather is good, this year could be even better.

I managed to obtain cuttings of African Blue Basil, and from these I have produced hundreds of additional plants and distributed them at the local garden club and to all the people who host my hives. This plant is extraordinary in its ability to flower continuously in our subtropical climate. The bees find the blooms irresistible and are foraging on them constantly. Since the plant is a hybrid and does not produce seeds, it is easy to convince farmers that it will not become invasive. It would be interesting to see articles on the plant and some figures on the suitability of this plant as a source of forage for bees.

It is Time to be Thinking About Bait Hives

Swarms Are Precious: Why Not Try a Bait Hive and See What Happens?

Ron Brown, MBE (BKQ 57 Spring 1999)

Every year there are many reports of swarms hiving themselves in empty brood boxes, or even in stacks of honey supers, and there is no doubt that boxes that other bees have lived in are most attractive to bees looking for a home. If you have an empty hive, with frames of used combs, in the garden, you may notice bees going in and out as if curious. Should the number of bees doing this increase considerably over two or three days, they are probably scout bees sent out to look for a home by a colony about to swarm. The scout bees may even come from a swarm of bees hanging unobserved in a tree up to half a mile away. Within 48 hours or less the swarm may arrive.

Why not prepare a bait hive and see what happens? You will need a brood box (preferably British National size) in any case, so get it ready as soon as

I have sent pictures of the colour variations I am seeing in my bees. After some research it appears that this is a good thing as it shows that my bees have good genetic diversity. The pictures were taken on the same basil plant, same time, same day. Observation of hive entrances show I have black and yellow bees in the same hives. Since, as far as I am aware, we have only Apis mellifera scutellata here in Bulawayo this is a natural genetic variation. I am establishing hives in a local farming area on the Umguza River, and the first two hives are building up well. There are both large and small hive beetles in the area which can be a problem: small, low hive entrances are required. I have found that guinea fowl and hens can be a great help to keep down the beetles as they eat the larva and scratch around the hives.

possible and fit it out with ten frames of foundation and one frame of old but clean, dark brood comb (to attract the scout bees). Even better would be a secondhand four or five frame nucleus box with frames of combs that have been bred in, and a small entrance smeared around with wax and warmed propolis scraped from one of the old frames. Place well above the ground, about 5' - 6' (2m) up; this is then very likely to attract a swarm during June and July.

When occupied, the bees can be shaken into your 'proper hive' and the trap set up again. Transfer just one of the old combs plus bees and replace it in the nucleus with a frame of foundation.

What are the snags? If you leave any space in the the bait hive not occupied by frames, the bees will choose to fill it with new, wild combs, perhaps built at an awkward angle, rather than use the frames provided. There is also the risk that wax moths will get to work on any old frames of comb and make a horrible mess of them, but these risks have to be taken, for a few weeks only.

What are the ethics of this? In law bees are wild creatures temporarily housed, but when they escape from an apiary they are considered to have regained their freedom, unlike cattle or sheep, hens or geese which are domesticated. Among beekeepers themselves, ownership of a swarm is usually conceded if a

beekeeping neighbour says that he saw a swarm from one of his hives fly towards your premises, or if the queen is marked in a distinctive way. In practice this is rare, and a swarm may have come from a church steeple or a hollow tree.

(I see nothing at all wrong with putting up bait hives. It is a common practice in many countries (though illegal is some like Switzerland) and I remember a pleasant afternoon I spent with Job Pichon in Brittany doing the round of his baits. It took me some time to see them for they were often quite high up or hidden in the trees. Swarms are extremely valuable today - better that they end up in a bait hive of a beekeeper who is going to look after them and treat them rather than become a nuisance to the public should they enter a wall space and thus end up being destroyed. Editor.)

25 Diversity in Honey Bees

B fD article

Images © Jonathan Vincent

Bait hive high up in a tree.

Waiting for the Bees

Simon Ferris

In February I attended an event to build a top bar hive, at Bere Marsh Farm in Dorset. The farm is owned by the Countryside Restoration Trust and there were six of us, I think, that attended a workshop and assembled hives in a day, under the guidance of Jim Binning. He is based in Bridport and known as "Jim the Bee". You may know of him; he is a kind man and patiently helped us all assemble our hives. The timber had been sourced locally (western red cedar, rough sawn but all pre-cut to size). Our workshop was held the day after storm Eustice. At least the barn where the workshop took place was still standing. I set my hive up in the garden and also put out an old national brood box - on a new stand and with a new roof (seconds, from Maisemore Apiaries).

On 27th and 28th May I scythed some of the long grass in our garden. Within a day or so, scout bees appeared at both the top bar hive and the national brood box. I was encouraged and for some days the scout bees kept visiting ... but then disappeared as quickly as they came. I didn't expect to see them back again, thinking they had found a home elsewhere.

Then on Sunday 12th June at 2:30pm Juliet, me and my sister were outside the house, having a cup of tea after a lunch at our favourite pub. As we sat with our tea, interrupting that quiet afternoon came a strange sound, almost as if out of nowhere. I said it sounded like a swarm of bees, but couldn't at first see anything, but then ... half way up our garden above the apple trees was this cloud of activity (and noise) - absolutely amazing! We watched for a time - of course I hoped the bees' plan was to go straight into my lovely (as I saw it, at least) new top bar hive and I would then sit back, knowing I was now a fully-fledged natural beekeeper. It didn't quite happen that way though.

The swarm drifted a little, more over our neighbours’s garden, to a high multi-stemmed ash tree. Earlier in the year some of the boughs of that tree had been taken off by a tree surgeon, but at its base is the remains of an old stem, now about 10 ft high, in which, on the far side, is an opening to a cavity. Well, after about ten minutes of the swarm having arrived, it seems the queen was in there pretty quickly, as the bees didn't cluster as such - there were many flying around of course, but within a couple of hours I would say they had all taken up residence.

Fortunately, our neighbours are ok with bees (the next neighbour over has gardeners who used to keep bees) and they will be left undisturbed. I'm hoping that maybe next spring that wild colony will swarm and find that the top bar hive is then acceptable. It may be that the wood was a little too damp still (I noticed that when assembling, the screws would squeeze damp from the timber) so this dry summer will hopefully have helped season the hive sufficiently.

I cannot help wondering if a) there is any connection between scything grass and bees appearing and b) whether the scout bees would have found their nearby natural home anyway, or whether the bait hives attracted the scouts to the area initially and then the natural home was found and preferred.

I know of other conventional beekeepers in nearby villages and there may be a swarm available next year via them, if I keep my ear to the ground. I've also joined the Hampshire Natural Bees group - a very helpful and friendly lot.

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 26

"My story - not that dramatic, but for me it was all very exciting!"

Above: Simon Ferris. Bottom left: the swarm preferred a cavity in a mature tree in my neighbour’s garden. Bottom right: I watched and waited hoping that they would choose my hive.

Aspects of Traditional Beekeeping - Yesterday and Today - in Lithuania

Simona

Simona

When I close my eyes, I see a flowering meadow. There are no flowering fields of rapeseed or phacelia. All that blooms are native, not alien plants. In the forest behind the stream, alder buckthorns, rowan trees, and elderberries are blooming. The bees hum quietly. At the edge of an area of a half-hectare, near a small round pine tree, a straw hive with wooden box for honeycombs is set on a table (Pic.1). This is my first populated hive! And I proudly have already giving a name of ‘apiary’ to my land with one beehive standing in it! And then I open my eyes, I see it is a green winter outside the window. Now I am in the Netherlands. Here I hope to start learning beekeeping from a famous skep beehive beekeeper in spring.

All my weaving activities started in a nature camp in the ancient Lithuanian apiary-museum in our own Dzūkija National Park. There I learned how to weave a traditional unit of measure of volume and a container as well – gorčius (Pic. 2-6).

In the times of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, this container of the XIV -XVI centuries corresponded to the current of 5.6 liters, and from the XVI century - to 2.8 liters. Lithuanians measured volume by gorčius for a long time, differently than in

1: My wooden box of honeycomb with woven skep - already covered and plastered with a mix of clay, sand and lime.

2: On the right of the picture – two finished gorčiai and at the left – the starting phase of gorčius’ production.

3: The start of weaving gorčius. On the left it is made with freshly digged pine root out of earth, and on the right – the same root just kept in water for a long time (one month) adjusted for weaving.

4: Gorčius, the dark one and the light one.

5: The bottoms of gorčius.

6: Gorčiai in my hands.

27 Aspects of Traditional Beekeeping - Yesterday and Today - in Lithuania

1 6 5 4 3 2

Europe, Lithuanians didn’t start to measure by liter when it was introduced in XVIII century. Even until the beginning of the XX century we measured in gorčius. Although there were bees buzzing around the camp, I had never heard of woven beehives before. In Lithuania, bees have been raised in tree trunks and hollow hives for many centuries. Such beehives are also in the Musteika apiary-museum, you can scroll it on www.facebook.com/Ancient.beekeeping.

Weaving gradually turned from a hobby into my livelihood. I was often invited to various festivals and cultural centers to teach braid weaving. I remember how a woman came to one of them and asked if I made beehives and began telling me about her grandfather who lived in the region of Klaipeda and was a beekeeper in braided beehives. I even

gasped in surprise. In the winter of that year, I went to several of the largest Lithuanian museums to see the old Lithuanian beehives preserved in the museum funds. I photographed them all and measured them so that I would know how to make them. Knowing my new passion, an acquaintance sent me the contacts of a woman who sells braided beehives. This is how the first exhibits of my collection came about (Pic.7). The idea finally matured to allow me to weave my own first beehive (pic.8).

Now that I already knew how to weave I realized that some Lithuanian beehives are woven in the same way as ‘gorčiai’. The most difficult thing was to get a large amount of Lithuanian long rye, because due to the developing agricultural policy, farmers grow less and less of it, because

7: Old cylindric skeps that I was lucky to buy.

8: My first woven skep among other creations.

7: Old cylindric skeps that I was lucky to buy.

8: My first woven skep among other creations.

Natural Bee Husbandry Magazine | No. 26, Winter 2023 | Bees for Development Journal No 145 28 7 9 10 11 8

9: The meadow of rye. 10: The rye cut with sickle. Later they are lied on and wrapped into tablecloth. 11: After day of work it is possible to relax.

the payments for it are significantly lower than for wheat (Pic.9) I cut rye for beehives in the same way as for gorčiai or braided plates - with a hand sickle (Pic.10). Then I wrap them like babies in tablecloths and carry them to the car. Cutting rye is quite difficult, I get quite tired after such work and I want to lie down (Pic.11). There is a lot of work to be done at home - to cut the ears of rye with scissors, to clean the leaves from the straw, to pick out weeds. And then I go to the forest for digging pine roots! Yes, you heard it rightpine roots are torn, they will be used to interweave rye straw. In the same way, “gorčiai” are woven in Lithuania from rye straw and pine roots or linden wicks. It's true, now that I've been in the Netherlands, I've started to get a little lazy and buy ready-made and split rattan canes.

Woven beehives have been known in Lithuania since the XIX century, although it is possible that this tradition was known in western Lithuania much earlier. Most of the largest Lithuanian museums have at least one woven beehive in their collections. And the number of people who are interested in braided beehives is gradually increasing. Here is my Face-

12 13 17 18 19 21 20 22 16 15 14

17: Two rings of cylinder skep on the wooden honeycomb; 18: One cylinder skep with a lid; 19: Cylinder skep weaved the same way as hat shaped skep; 20: The long skep from Šiauliai Aušra museum; 21: The long skep with door from Šiauliai Aušros museum; 22: The long skep, the form of which reminds us of the skeps of Breigel’s drawing.

Traditional forms of Lithuanian round hives

book page: www.facebook.com/pintiaviliai which already has more than 700 followers. You can also buy traditional or sun beehives that I weave there.

Traditional Lithuanian woven beehives are divided into types according to their shape - hat-shaped (Pic.12-16), cylinder-shaped (Pic.1719) and long beehives (Pic.21-23). The first ones are earlier. Interestingly, unlike in Western Europe, the hives here have a wooden pin going through the central hole. It can be long, reaching the arc of the hive and connecting to the wooden part of the antechamber (Pic.13), or short, just 7-10 cm, covering only the central opening of the hive from above. The hives are quite thick, going from 5.5 to 8.5 cm thick. Winters in Lithuania are cold, sometimes it can be under -20 degrees Celsius at night, so a thick-walled beehive is necessary. The cylindrical hives (Pic.17-20) are woven in a completely different way which is by placing rye from above on a wooden loom and pressing it with the help of a loom. Also, such cylindrical hives have a cover which can be made up from several cylindrical rings or also with a box for the honeycomb (Pic.17). I found one beehive braided in the same way as a hat beehive and even with a pin, but it is cylindrical and made of several rings (Pic. 19). Some of the hives wear out over the years and are repaired, such surviving marks can be seen in the museum exhibits. The smallest group of beehives found in Lithuania are the long beehives, only five of which are preserved in Lithuanian museums (Pic.20-22). One of them is very similar in shape to the beehive from the Bruegel’s painting (Pic.22)

I weave many different kind of skeps and there are so many examples from the past to learn more about, but sadly there is no room for further examples here (see my website(!). Of course, in order to produce a traditional hat-shaped skep it takes longer and the help of a carpenter is needed. The carpenter, Giedrius, helps me to make those beautiful wooden honeycombs boxes stools and pins. (Pic 23 -25). In the summer, I prefer weaving in the nature and that's where I get inspired and relaxed (Pic 26).

23–25: Wooden components of the hives I am unable to build, but they are expertly made by Giedrius. 26: Weaving hives in the outdoors on a pleasant day - what could be more relaxing!

30

23 24 25 26

Looking back: the Catenary Hive

Text and images from Home Honey Production

This unique hive was the invention of Bill Bielby in the 1970s and was publicised in his book “Home Honey Production”. Published by EP Publishing Limited in 1977 as part of the series of ‘Invest in Living’ - very practical books which enabled people to: improve their quality of life. have an interesting and rewarding leisure activity.

produce financial savings.