29 minute read

Mother and war

Mo ther and war

МMom, participant of the Great Patriotic War, who lived with us in Minsk for more than ten years, died nine years ago. When I think about her, images pop up on the inner vision screen. Some of them are formed on the basis of my mother’s stories about herself. Mariya, a teenage girl, enjoys herself sitting on a cart in a white butter-cloth dress made by her mother, wearing bluehemmed socks. She’s 12 or 13 years old. And they call her MashaM anechka-Marusya and Mariyka. And the cart is moving and moving into her misty future…

Advertisement

Ukraine, Kharkiv region… Beginning of the hungry thir‑ ties… The Falchenkos, the spouses Pyotr and Agraphena with their daughters and son, had already moved from the village Blagodatnoye to Rubezhnoye: father of Marusya, Vanya and the youngest Zinochka was appointed chairman of the local village council. And soon repressive actions were taken against them for “wrong administration of public wheat”. In general, for neg‑ ligence. And how it was in reality, alas, there is no one to tell about it today. Cherished memory to all my departed relatives.

And the cart is moving and moving… Marusya, swinging her legs, admires her canvas shoes. They’re washed and whitened with tooth powder. And she doesn’t know yet that when she is 15, she will go by train alone to faraway Karelia to visit her father, from whom she has’t heard for a long time. As well as the fact that he will be released later, and Pyotr Vlasovich will again work as a collective farm driver. And in the meantime, she doesn’t know that in the future she will get acquainted with the kindest woman with a grand name — Vera Nikolayevna, a noblewoman by birth. She will not only teach the girl the wisdom of banking, but also good manners, develop her taste and a sense of beauty.

Marusya does not know yet that she, a 17‑year - old girl, will marry my twenty -five year old father Mikhail Cherkashin. Having returned after his four -year service in the Marines in the Pacific Fleet in the

Far East, he will meet a brown-eyed slim-waisted girl at the Volchansky House of Culture, where he will come to work at the local brass band. And the waist of the young ac‑ tress of the amateur folk theatre is just the size of his palms’ girth.. Yes, my mother can not anticipate that soon in 1938 she will give birth to their son Yury, my elder brother. And she can’t even im‑ agine that terrible day when the war will break out.. Neither can my father, who, as a military musician, will be called to arms dur‑ ing the Great Patriotic War. And will pull 450 wounded soldiers and officers from the battlefield. I can’t help but cite the words on the award sheet of my father’s Medal “For Courage”: “Dur‑ ing the period of the HSB (health support battalion — Auth.) deployment, he was staying in the front group. He worked day and night, without sleep and rest, to help the sick and wound‑ ed as soon as possible. Only during the combat operation from About Mariya Cherkashina, a participant of the Great Patriotic War, one of those who is gone The fate of my mommy, like hundreds of thousands of Soviet women, fell on the wartime. She was lucky to survive, to enjoy life in her native Ukraine together with her husband, Mikhail Cherkashin, veteran of the Great Patriotic War. Also under the peaceful skies of Belarus among children and grandchildren.

20:061944. Cherkashin transported to the clearing platoon 450 wounded. During his work in the HSB, as well as during the transportation of the wounded by the HSB was fully involved in the evacuation of wounded soldiers and officers. He enjoys authority with the wounded. Comrade Cherkashin is worthy of being awarded the Medal “For Courage”.

He does not know that he will return home after a serious injury with the “Or‑ der of the Patriotic War, second grade” on the service shirt. He doesn’t know either about his long decent postwar life with my mother (Read more about it in the article “Dad’s War” No. 5–2015). …My grandmother Agraphena was taking her daughter to Volchansk, a dis‑ trict center in the Kharkov region, from the village of Rubezhnoye to study for a bank clerk. She was glad that it would be easier to survive, because there would be one mouth less to feed in the family. Fam‑ ine in Ukraine was terrible. Now there is a monument to the victims of forced fam‑ ine in Volchansky Central Park. I remem‑ ber my mother and grandmother telling me about people’s death… Agraphena herself and her children survived thanks to pieces of dough that could be taken out of the village bakery: clean a container, where it was mixed, and that’s the salva‑ tion for hungry mouths. They managed to hide the dough under the clothes so that they could pass by the guards unnoticed. Coming home after the shift, my grand‑ mother used to say, her godmother would stay at the open window, as if they were talking, and would scrape the dough off her body under the jacket and pass it to the grandmother discreetly. And it also hap‑ pened that while walking past the house she threw a piece of dough right onto the ground. Grandma lifted the dough, cleaned it from the weeds, and cooked soup with dumplings. And even with the dough the family was hungry. That’s why they sent my mom to town. Not long be‑ fore being sent to the camp, Pyotr man‑ aged to arrange with his friend, who worked in the bank as a manager, about taking Marusya as a trainee. That’s how my mother became an accountant later. And was promoted to a chief accountant.

I’ve never seen my grandfather Pyotr Vlasovich, not even a photo. From the beginning of the war he was called into the army, then, they said, he was a parti‑ san in the dense forests of the Seversky Donets, and later, when the offensive of our troops in Donbass began, he joined the army and perished at the front on March 21, 1942. In the generalized database of OBD “Memorial” there is information about the place of burial of my grandfa‑ ther: Ukrainian SSR, Stalin region, Yam‑ sky district, village of Nikiforovka, 1 km by the side of the road. Nowadays it is Donetsk region, Bakhmut district. My cousin Lyudmila's mother aunt Zina told me that her father’s grave was there. So we have a goal — to worship my grandfather, put flowers on his grave.

And also, knowing the worth of hard rural labor, Agraphena Timofeyevna, of course, wanted all her children — three daughters and a son, who were born be ‑ fore the war, to become educated, and, as t hey say, to make their way in life. And that exactly how it happened later. My mother and aunt Zina had a special secondary education, Sveta had a higher education. Uncle Vanya, born in 1922, became a mili ‑ tary pilot, fought as well as my father did. I t was he who became my link with Bela‑

Fifteen-year-old Mariya Cherkashina (left), along with her colleagues at Volchansky State Bank, 1935

rus, where he was living with his family. I r emember well when he came to visit us and brought a large box of chocolates with the word “Gomel” on it. I couldn’t under ‑ stand and kept asking him whether that wa s the name of the sweets. No, my uncle pilot laughed, this is a city in the country of Belarus… Our Gomel is a beautiful city, which I have visited more than once. As for

Novopolotsk, where uncle Vanya’s son and my cousin Igor, sisters Natasha and Sveta live, I have not managed to visit yet.

However, I will return to Rubezhnoye. I remember very well a huge poplar with swings in the yard of my grandmother’s small house, where my cousins, un‑ cle Vanya’s daughters, and I used to run about in summer. Grandmother treated us to lush Ukrainian dumplings with cher‑ ries and cottage cheese, and we cheerfully competed, who will eat most of them. I’ll never forget a terrible thunderstorm with lightning. It was so bright that it made the night windows look white. And the rolls of thunder that made the glass clink. And it was impossible to sleep: it seemed that my grandmother’s house would col‑ lapse. “It’s all right, kids, don’t be afraid, I’ll pray and the storm will bypass us,” said grandma. And she added: “That is not terrible, do not be afraid, children, thunder from the Germans is more terrible.” And she would pray quietly.

We also used to run to the village outskirts where there were German bunkers, the so-called dots. In March 1942 there were fierce battles in those places for the village of Rubezhnoye. Almost 10,000 soldiers and officers were killed in them. Today, at the place where the remains of heroes who gave their lives for the liberation of the village are buried, there is a memorial sign to the Unknown Soldier. It was unveiled on the occasion of the 75th anniversary since Rubezhnoye’s liberation from Nazism. And the remains of the dead were found by searchers in the local forests. The Memo ‑ rial of Glory in the village of Rubezhnoye, V olchansky district, is one of the most re‑ vered places. In 2018 Vasiliy Mamonenko, t he only front-line soldier in the village at the time, told about those terrible times of war (there is a video on the Internet). For everyone, he is a man of the era, because he went through all the war.

As my mother said, she liked it in the bank. Although it was difficult, she felt hungry, and dreamed about figures, she liked communicating with friendly peo‑ ple. They also gave food to a skinny girl, keen on studying: some people used to give her a piece of bread, others a pan‑ cake or a lump of sugar. Mom often recol‑ lected it with tears in her eyes. And with humor once told about Vera Nikolayevna who invited her to lunch at the weekend. She remembered sitting at the round table with a white tablecloth. There were spar‑ kling forks and spoons on the table lying next to the plates with golden edging, next to them there were starchy white napkins. First, bean soup was served, which was poured out of a tureen, and then small thin pancakes. My mother watched Vera Nikolayevna twist the pan‑

cake with a fork and dip it into honey. And she tried to do the same. But the pancake did not obey, moreover, it was spreading out on a plate as if it was alive. And Vera Nikolayevna’s brother watched her and said: “Baby, take it into your hand and eat with pleasure. And do not worry.” My mother remembered that dinner for life. Mother with a five-year-old son, Yury. The photo was taken immediately after Kharkiv was liberated from the Nazis in February 1943, and sent to the front to her husband. On the back one can barely read: To our beloved husband and father from his wife and son. With this picture, Daddy returned home in April 1945.

One day, she and I made pancakes and tried to fork them. It didn’t work!

Oh, my mommy, how much you went through, how much you endured…

“Everybody grieved and en‑ dured…” — my mom used to say when it came to war.

Volchansk was ruthlessly struck down by war, as well as other cities of the USSR. My mom had just turned 21. Her words sound in my memory: “We, like every‑ one else, have become numb: what to do, where to run, how to survive…”.

Father was called to the colours im‑ mediately, on the third day of the war, and s ent to the airfield service battalion, i.e. 690th airfield service battalion, 100 km from Volchansk, near Valuyki, district center of Belgorod region. And he was made in charge of a grocery storehouse. And when in the winter of 1942 he was driving through Volchansk, he managed to… take his young wife with their 3‑yearold son and bring her to the battalion. But, of course, he wasn’t allowed to live with his family… Still, my mother didn’t go back: she started to work at the airfield service battalion as a bookkeeper. And my brother Yury was looked after by a village woman, who hosted civilian Mariya Cherkashina. “It was terrible time, in February, cold was unbearable, and so many pilots died — said my mother — day after day…”. Ac ‑ cording to her, many wives and children f ollowed their men to Valuyki: everyone thought the war would soon be over…

But, as we know, the war lasted for a long time. My father fought for three and a half years, was wounded twice. More than a thousand three hundred days and nights my mother, like most wives of those who had gone to war, was without him.

When in February 1942 my father was transferred from the airfield service battalion to the 51st guards rifle division and enlisted in a musical platoon, she, hav ‑ ing stayed enough at strangers’, returned t o Volchansk. After having been in the territory of military operations, mother, as she confessed, was no longer afraid of anything. Our town was occupied twice: from October 31, 1941 to November 12 of the same year. And from June 10, 1942 to

February 9, 1943. And during the Khark‑ ov offensive operation it was liberated by t he Soviet troops of the Voronezh Front. So my mother lived under occupation for more than six months. Many Volchansk women, and those who lived on our street Podgornaya, outskirts of the town, worked wherever they could, sold something. To find a job was a big luck. Young people, like my mother, were taken to clean the dining room, paid with expired products, or the left-overs from the Germans’ plates. And the more she managed to collect, the hap ‑ pier Mom came home. After all, she was wa ited for by her mother - in-law and my brother Yury. It is difficult for me to imag ‑ ine not only the fact that they didn’t have en ough to eat in those days, but also how they managed to find room in a tiny mudwalled hut with a straw roof. Because there was only one room and a kitchen. Appar ‑ ently, for this reason, one of the top -rank Germans, as my mother said, stayed only a couple of days. But he managed to scare her to death. Mom was just hanging out her laundry, and through the holes in the fence, she saw a fat man who had dined heartily, go out into the yard and head towards her. She ran into the garden, which stretched under the mountain. When she saw with her side vision that the German was quick ‑ ening his pace, mother rushed up a steep s lope of a ravine overgrown with ground cherry. She had no idea that he would find the path and climb the mountain. Just twenty meters from the edge of the ravine there was a field of corn which was quite tall. It saved my mother. First, she hid herself there, ran a little, and then spread out between the stalks, and pressed to the ground. The heart, she said, was jumping out of her chest, it seemed that the German could hear its beats. But he stopped in front of the field and turned back. She stayed in the corn-field till dark, and when she re ‑ turned home, the grandmother said: the G erman had packed his things and left on the motorcycle. After him, a tank crew arrived to stay in the house, or maybe it was some other armoured vehicle. Those three were young Hungarians, or Roma ‑ nians, as my mother said — the Magyars. A nd they didn’t hurt anybody. They didn’t even mind it when my little brother had stolen a couple of pressed cocoa and sugar bars from them, chewed them up behind the barn and came home with his mouth smeared. In gestures, laughing, the guests said, “The Germans would have shot him immediately”. And sometimes they gave him cookies and plain biscuits. When our troops began their offensive, they left and warned the whole family to stay in the cellar. I remember well that cold ground cellar. It remained there when our big bright house was built in place of the hatka (peasant house).

Mom’s war under occupation was primarily for survival. In summer it was easier: apples and apricots were ripe in the garden. It’s true, they made people want to eat even more. Bread was rare. In Au‑ gust they dug up potatoes, carrots. They made borsch from beet tops with potatoes and carrots. There was corn on the moun‑ tain. Although it was forbidden to take it, people still managed to take at least some corn-cobs for themselves. Kids chewed it raw. Their growing bodies needed food badly. My mother told me that even after the war Yura used to run to his father’s cousin, stopped at the door and waited for something to be given to him. And if the pause was too long, he began to whim‑ per diplomatically: bunjka, grandmother,

How beautiful the bank employees were after the war. Mom (right) and her friend, 1946.

has not yet stroked a fire, bunjka, has not cooked yet…

When after the liberation of Kharkiv region the bank returned from the evacua‑ tion, my mother went to work there again. Employees, she said, greeted each other as if they were relatives… So bread ap‑ peared in the house, which was rationed. My father’s sister Olga came back from the evacuation with her two children — Alik and Valya. That’s what my cousin recol‑ lected:

“I remember walking around the city, skinny, exhausted… But alive! And in the

center we met aunt Marusya, who was running to the bank to work. We came to Podgornaya Street and started liv‑ ing there. All five in one small room: me and my sister with our mother and aunt Marusya with my cousin Yurka. And grandma Katya slept in the kitchen…

With Yurka we ran to the ravine, which was adjoining the Cherkashins’ garden, there were two trench shelters, where we found all sorts of things left by the Germans. We even found grenades and an automatic pistol that uncle Misha (my father — Auth.) handed over to the police.

At the time people lived poorly, halfstarving. In 1946, in Volchansk, the hun‑ ger was terrible: the birds didn’t even chirp. I remember feeling hungry all the time. And when uncle Misha started working at the oil-mill, he loaded oil cake (a product derived from sunflower seeds after isolating oil by pressure — Auth.), we all felt more cheerful. Oil cake tasted better than chocolate for me. And Yurka said it was even sweeter than the bars of cocoa he once had stolen from a tank and chewed up behind the barn.”

My father came back in April 1945. In a hospital in Ekaterinburg, then Sverdlovsk, he had been treated for over three months. Dad’s war began on June 24, 1941 and end ‑ ed in April, 1945. I found these dates in his R ed Army book and military registration card after he passed away in 1993. And that my father was treated in hospital 414, I found out from his documents. There, in Yekaterinburg, at 145 Mamin-Sibiryak Street, on the building of the House of In ‑ dustry, there is now a memorial plaque m ade of grey marble in memory of hospital 414 …

Dad fought on the Kursk Bulge and near Stalingrad. He also lib‑ erated Belarusian cities. I heard about Operation Bagration, as well as Polotsk and Vitsebsk… As part of the 49th special communications regiment, which, by the way, had the honorary title of Polotsk, fought through the north-western regions of Belarus towards Daugavpils. I know all this from his short stories about the war, which he did not like to talk about, no matter how much we tried to make him talk. And, of course, from the Red Army book, I know about all the awards my father won. They were carefully kept by my mother. She was the one who made my father wear a jacket with the orders and medals and take pic‑ tures. As a keepsake for the children and grandchildren. Thanks to mom, this pic‑ ture is kept in the family archive. And she made him go to the Kursk Bulge on the occasion of one of the Victory Anniversa‑ ry dates. The Volchansky district military committee took the veterans of the Great Patriotic War to the famous memorial complex, which was opened on August 3, 1973 in honor of the heroes of the Battle of Kursk. I remember my mother telling me: father was very pleased. And how happy he was when I, already living in Minsk, gave birth to his a grandson Bogdan! And only then, after years since the war, his heart seemed to soften. I will never forget my Daddy’s smile when he was holding

Bogdanchik, a three -year - old, in his lap. And how proud he was of his grandson when he went to study “to be a doctor”. He said he would become a true man!

By the way, grandmother Agraphena, Zina and Sveta also survived during the war years. Before the battles for Rubezh‑ noye Pyotr Vlasovich managed to trans‑ port them to his parents in Blagodat‑ noe. And later grandmother returned to Rubezhnoye again, her house on the out‑ skirts of the village survived. My aunts got education, got married. Sveta with time took the grandmother to the city of Yel‑ low Waters, which is in Dnipropetrovsk region.

Chronologically Mom’s war ended with the return of the father, as well as in any other family, where the breadwinner returned after the war. There was hope that it would soon be easier. There was new experience of post -war life in which I didn’t exist yet…

But that damn war was invisibly still present. When my husband and I invited my mother to stay with us, surrounded her by attention and care, the memory of war and famine showed itself in her care for food. She said we should always have salt, sugar, cereal in the house. How she re ‑ joiced when the refrigerator was full. And s he didn’t like it when there wasn’t a slice of bread in the house. And how gently she was holding it in her fingers. She used to re ‑ member that there was no bread under the o ccupation and, immediately after the war.

I remember well a large bag of bread‑ crusts, which was hung on a nail in the pantry, and was replenished from time to time. It hung in both the old house and the new house. The breadcrusts were drying in the oven. I also remember well that aroma and spicy taste of them. Sometimes mom and dad would break them to pieces and throw them into the soup…

And how proud she was when in 2002, at the Minsk Mili‑ tary Committee of the Soviet

District, she was presented

with a certificate of participation in the Great Patriotic War based on her per‑ sonal file, confirming that Mariya Petro‑ vna Cherkashina had participated in hostilities. Before that, when we went on holiday to our homeland, we requested a notice from the Volchansky district mili‑ tary registration and enlistment office. I remember how skeptical the employee was about our request, wondering: why your grandmother needed it, what kind of a participant of the war she was… They treated our actions in Minsk with respect. It’s right that people like your mother are marked out, not forgotten, said one of the women who gave her a certificate, because at any moment the combat airfield where she was working could have been bombed.

As a result of the status of a Great Pa‑ triotic War participant, mother’s pension got higher. And how happy she was when every year on the Victory Day she received triangle greeting cards signed by the Presi‑ dent of Belarus. And proudly listening to Alexander Lukashenko’s speech, she sat in the hall of the Palace of the Republic where she was invited to a concert dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the Victory.

It was also unforgettable for my moth‑ er that she received an unusual congratu‑ latory message on her 90th birthday. On April 25, 2010, a real military band was playing melodies of the war years on a green lawn under the windows of the house on Logoysky Trakt in Minsk. My mommy, sat in a wheelchair, with flow‑ ers in her hands, crying. She probably re‑ membered her husband, a military musi‑ cian. And her war.

We’ll celebrate 75 years since the Vic‑ tory without mom, she is one of those who are gone. According to the tradition estab‑ lished by my parents back in Volchansk, the Minsk part of our family will get to‑ gether. Men will raise 100‑gram daily ra‑ tion of vodka. We will certainly remember that my father never drank more. Because he was sure: it’s manly.

We’ll also buy bright red tulips, put them near the portraits of our dear peo‑ ple. And we’ll light a candle in my dad’s old fishing lantern.

By Valentina Cherkashina-Zhdanovich

As recorded — believe it

A BSU student has collected over a hundred recollections of war participants

In the house of a Great Patriotic War veteran, fate brought me to‑ gether with Roman Zinchenko, a freshman of the History Depart‑ ment of the BSU. He has been working as a volunteer with veterans for four years, and has recorded recol‑ lections of 120 war veterans who are living in Minsk and Minsk region. For Roman it is priceless in itself. —In my family, the veteran is my great-grandmother Chupris Mariya Fyodorovna. She was born in the vil‑ lage of Boriski, Minsk region. At the age of 15 she left for the city, and at the beginning of the war she was al‑ ready working as surgeon assistant in Klumov’s hospital. The famous Evg‑ eny Klumov, who was sent to the gas chamber by the Nazis in March 1944… Hero of the Soviet Union.

From 1942 to 1944, the great grandmother participated in the par‑ tisan movement, was a liaison in the detachments “Dima” and “Gromyko”. In our family the following episode is often recollected. Mariya Fyodorovna was walking around the Komarovsky market in Minsk in a beautiful fox-fur collar coat. It was winter. It was cold. She was in a hurry to carry out the task, i.e. to deliver leaflets and a report from one secret address to another. Sud‑ denly armed patrol appeared. They noticed her and signaled to come. The great -grandmother came up to them, her legs giving way. It was cold for the Germans, too, the winter was severe. They wanted to tear the foxf ur collar off the great-grandmother’s coat in order to use it for themselves, to protect themselves from frost. The collar wouldn’t come off. The great g randmother was more dead than alive as the leaflets were hidden un‑ der the collar. The fox fur was so close to coming off… But suddenly, a hot patty cake seller appeared nearby, be‑ gan to loudly tout for customers, and the Germans forgot about Mariya Fy‑ odorovna for a while. While they were eating the patty cakes, she managed to run away. I keep her medals, certifi‑ cates, photographs, award documents and the Order.

My great -grandmother had an el‑ der brother Chupris Dmitry Fyodor‑ ovich, a career military man born in 1910. He participated in the Polish campaign of the Red Army, in the war with Finland, in the Patriotic War, de‑ fended Moscow. And in 1942 he was parachuted on the territory of Be‑ larus to become the chief of staff in the subversive detachment “Dima”. I know that Dmitry Fyodorovich took part in the preparation of the assassi‑ nation attempt on gauleiter Wilhelm Kube. He liberated Belarus, Poland, fought at Koenigsberg, and celebrated the victory on the Elbe…

I couldn’t help but ask: “Why do you need to know all this today?” —I’m interested in people’s fates, how they survived, how they fought the enemy under extreme conditions. In our family we used to talk a lot and often about the war, but I did not see my family war veterans alive. Perhaps, this made me do volunteer work with the veterans, record their recollec‑ tions…

Roman Zinchenko carefully col‑ lected from the table old photos with portraits of war participants, shabby documents, awards of his great g randfathers. He was in a hurry, the veterans were waiting for him in the hospital. By Vladimir Stepanenko

Rich culture takes over the world

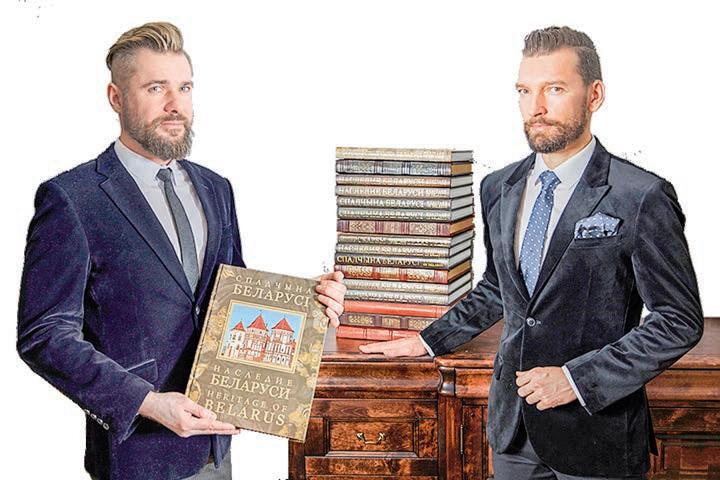

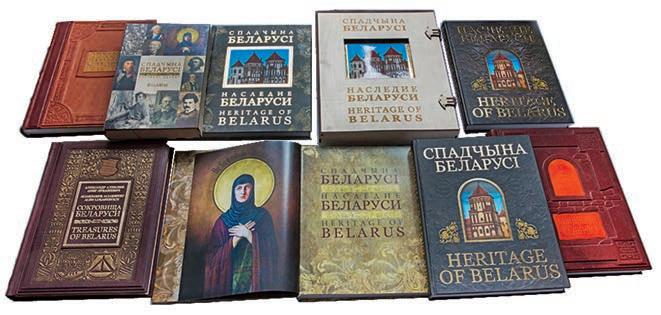

The art project “Spadchyna of Belarus” is submitted for the State Prize

In an attempt to solve the code of Belarus many researchers and art‑ ists tirelessly write about our coun‑ try, glorifying it in the works of art. A lexander Alekseyev and Oleg Lu‑ kashevich have created one of the m ost prominent and significant art pro‑ jects in the history of modern Belarusian c ulture — “Spadchyna of Belarus”. With the help of three components (presenta‑ tional books -albums, documentaries and photo exhibitions) the authors managed to create a recognizable brand “Spadchy‑ na of Belarus” and rediscover the country n ot only for the Belarusians themselves, but also for the foreign public.

Developing the concept of their project in 2001, Alekseyev and Luka‑ shevich, in many ways, were ahead of time: they were the first art photogra‑ phers to persistently destroy the stereo‑ type of “peasant” Belarus:

спадчына.бел

— W e didn’t even suppose that our album “Spadchyna of Belarus” would be so demanded, — admi ts Oleg Luka‑ shevich. — Nevertheless, since 2004 the book has been republished 18 times, 46,500 copies have already been issued, and journalists called it a bestseller about the Motherland. And at the begin‑ ning of our journey we were led by love for our country, the feeling that such a book is necessary for Belarus, that we can’t always exploit the theme of folklore and nature while talking about it. When a person comes to a strange country for the first time, he pays attention first of all to the material heritage: architecture, works of art, what was created by previ‑ ous generations. It was very important for us to gather our national wealth un‑ der one cover to show that Belarus did not appear yesterday, the country has a thousand-year history, there were many enlightened people, scientists, masters, artists, patrons of arts.

Since 2004, books-albums “Spad‑ chyna of Belarus” have been in the gift co llections of most heads of state and government, in the largest libraries of the world, in prestigious universities, cultur‑ al and diplomatic institutions, in private co llections of famous people — from the Queen of Great Britain to the Pope.

Thanks to the painstaking and tal‑ ented work of Lukashevich and Alek‑ seyev, on the pages of their publications we discover a dazzlingly beautiful re‑ gion with a rich history. —Now there is a good wave of reviv‑ al; many Belarusians, especially young p eople, are interested in their native language and history, they are eager to travel around the country,” Alexander Alekseyev said. — I t hink our project has contributed to it in many ways. After all, when we started, famous at present architectural monuments and tourist routes were in the sidelines. But we man‑ aged to present them in a favorable light.

First in everything

In the books-albums “Spadchyna of Belarus” the authors were the first (in the presentational edition) to purpose‑ fully create the concept of artistic rep‑ resentation of the historical grandeur,

uniqueness and diversity of architectur‑ al monuments and items of decorative and applied art of the 19th — early 20th centuries in all regions of the country. In each republication the data on the na‑ tional heritage are updated. And if we compare the editions of 2004 and 2017, one can see a long way of Belarus on way of restoration of historical monuments.

Thanks to the project, the Bela‑ rusian heritage and culture were pre‑ sented at prestigious exhibition ven‑ ues of the world: from the UNESCO headquarters to the British Museum. In Paris, London, Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Rome, Warsaw, Beijing, New York, Washington and other cities peo‑ ple learned about the rich history of Be‑ larus. In Paris, the project “Spadchyna of Belarus” was exhibited for more than two years (the works over 2 meters in size were purpose -made). And in Minsk, for five years, the photos from the booka lbum were admired by everyone who was walking past Chelyuskintsev Park, where breathtaking landscapes were placed. It was the largest exhibition in history: almost one kilometer of exhibi‑ tion space, 150 three -meter works. And today the permanent exhibition of the project “Spadclosehyna of Belarus” dec‑ orates the Independence Palace. Since 2003, the authors have held 30 larges cale national and international photo exhibitions.

Perhaps the success was facilitated by the fact that the art project, again for the first time in history, received the blessing of two major confessions of Be‑ larus, Orthodox and Catholic.

The first book was published in Sep‑ tember 2004, and the edition of three thousand copies was sold within 29 days. The rest, as they say, is already his‑ tory. The authors of the album were a tremen‑ dous success, there were numerous reis‑ sue of the album with its unique representative function, which was noted at the high‑ est level: on January 7, 2005, President Alexander Lukashenko presented Alex‑ ander Alekseyev and Oleg Lukashevich with the award “For Spiritual Revival”. — S uch a high appraisal was very supportive of us at the beginning of our journey, we understood that we should move forward,” the authors note.

Each book -a lbum “Spadchyna of Belarus” consists of 320 pages, more than 400 art photographs, which rep‑ resent each region of the country and provide important information about the most significant facts in history in three languages: Belarusian, Russian and English.

The book is a true value

The letter from Buckingham Palace, sent by order of Elizabeth II, contained the following lines: “Her Majesty noted: this edition is a wonderful voice of Be‑ larus. The book is a true value, which will immediately enlarge the Royal Li‑ brary”.

Lukashevich and Alekseev had the honor to donate the album “Spadchyna of Belarus” in 2004 to Pope John Paul II. In a letter of gratitude from the Vatican State Secretariat it was noted: “I thank you for the noble gesture of present‑ ing to the Holy Father an interesting book “Spadchyna of Belarus”, which contains information about historical, artistic and religious monuments in different regions of Belarus, illustrated with beautiful photographs.

A series of documentary films “The Epoch”, “Artists of the Paris School. Na‑ tives of Belarus”, “Contemporary Art of Belarus” (31 films in total) blended in with the project “Spadchyna of Belarus”. The authors were the first in documen‑ taries to investigate in detail and on a large scale the biographies of Saint Euphrosyne of Polotsk, Mark Chagall, Ignacy Domeyko, Tadeusz Kosciuszko, Adam Mickiewicz, etc.

Research materials, photographs and documents of the project “Spad‑ chyna of Belarus” are constantly used for educational purposes in various educational institutions, museums, spe‑ cialized organizations, in the framework of state programs for putting historical landmarks of Belarus on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

For the Belarusians themselves, this project does not only reveal the origin, uniqueness and richness of the national history and culture, but also awakens a sense of pride in their country, makes them think about careful treatment of their property, revival of the lost, future effective development. ◆◆◆

Pavel Sapotko, director of the Na‑ tional Museum of History: — There is no other presentational book-album in the national book edi‑ tion that has been such a success and has had such a circulation. The value of the project is that the authors have taken the research aspect as the basis for their work. This is what allowed the project to reach the international level.

Sergey Klimov, Director of the Na‑ tional Historical and Cultural MuseumReserve “Nesvizh”: —The project has taken its rightful place in the national culture. The au‑ thors, Alexander Alekseyev and Oleg L ukashevich, managed to create not only their own concept to promote and popularize Belarus’ historical and cultural heritage, but also to com‑ bine modern approaches in pub‑ lishing, exhibition and video p roduction. This project opens wide opportunities to present the historical heritage of Belarus in the international arena.

By Viktoriya Popova