24 minute read

The most Belarusian of all Parisian artists

For several months, since the end of last year, the exhibition “Schraga Zarfin. Leading to the light” was open in the National Art Museum of Belarus. Dozens of interesting paintings were presented in the exposition which was telling about the work of the artist of the Paris school, a native of the Belarusian town of Smilovichi.

Advertisement

It should be said at once that this is the first personal exhibition of FaïbichSchraga Zarfin in Belarus. And it was timed to the 120th anniversary of the artist (1899–1975). The exhibition ac‑ quainted the viewer with Zarfin’s works, which belong to the Group of Compa‑ nies A‑100, as well as presented the au‑ thor’s paintings from private collections, told about his artistic and spiritual quest.

So, plain biographical lines tell about the following. Faïbich-Schraga Zarfin was born January 7, 1899 in Smilovichi, near Minsk. He started painting in his early childhood. In the 1900s he befriended Chaïm Soutine, also a native of Smi‑ lovichi, thirty years later the friends met a gain in Paris. In 1913, Zarfin, follow‑ ing in the footsteps of Soutine, entered t he Vilna Drawing School, but a year later went to Palestine. There he studied at the Bezalel School of Arts, worked in a kibbutz. In 1918–1920 he served in the British Army, fought for the liberation of Palestine from the Ottoman Empire.

After the end of the First World War, Zarfin returned to Bezalel, and partici‑ pated in a number of exhibitions. Wish‑ ing to continue his education, he left for Berlin, and a year later moved to Paris. Here he was learning on his own, began to cooperate with publishing houses and fashion houses, exhibited his paintings. In 1929 Zarfin got married, two years later the spouses got French citizenship.

In the 30s Zarfin worked a lot as a tex‑ tile artist. Critics called him “a virtuoso of s ketches for textiles”. During the Second World War, almost all of Faïbich-Schraga’s works of the previous years disappeared without a trace, only sketches for fabrics miraculously survived in a number of pri‑ vate archives. At the exhibition in Minsk s everal of such sketches were presented.

During the Second World War Zarfin first served in the French army,

then took discharge and participated in the Resistance Movement. Even at this difficult time, three of his personal ex‑ hibitions were held — one in Grenoble and two in Lyon. It was then that Zarfin developed a technique that later became his “individual style”, i. e. he managed to mix gouache and oil paints.

In 1945, Zarfin returned to Paris. But soon — two years later — they moved to Rosny-sous-Bois, a small town near the French capital. Life in postwar France, destroyed and looted by the Nazis, was very difficult, but it was at that time that Zarfin decided to follow the advice of his oldest friend Chaïm Soutine and fully devoted himself to painting. His crea‑ tive works started to increasingly bear t he impress of the artist’s intense inner life, especially after he learned of his par‑ ents’ death in the Smilovichi ghetto. It was o nly in the 1960s that the artist managed to overcome his inner crisis. A beautiful blue colour appears in his works, they are filled with peace and tranquillity.

One of the leading themes in the work of Schraga Zarfin are landscapes of France, which became his second homeland. The artist was a wonderful colorist, he used a peculiar individual palette, developed a recognizable tech‑ nique, was always in search of new ex‑ pressive means. His works are in many museums in France, in the collections of the Rothschild Barons and in the Char‑ lie Chaplin family.

All of Zarfin’s friends and relatives noted his mysticism and desire for intel‑ lectual communication. The artist read a lot, tried to travel, got acquainted with new lands and people.

Schraga Zarfinn died in 1975 after a long illness and was buried in the cem‑ etery of Rosny -sous-Bois.

Exhibition as learning the talent

At the exhibition “Schraga Zarfin. Leading to the Light” in Minsk there were 52 works of the artist, created in different years, which reflected most diverse facets of his talent. The largest number of paint‑ ings, a collection of works which belong t o the Group of Companies A‑100, was purchased from the heirs of the artist two years ago, but it was presented to the Be‑ larusian public for the first time.

According to the curator of the ex‑ hibition, Yury Abdurakhmanov, the daughter of the artist did not want to sell her father’s works, but Belarusian businessmen persuaded her that the works of Zarfin should be presented in the historical homeland. It is also inter‑ esting that the idea to “return” the artist to Belarus belonged to Pavel Latushko, the current general director of the Yanka Kupala National Academic Theatre, in the years when he was Ambassador of Belarus to France.

By the way, the opening of the exhi‑ bition in Minsk was attended not only by art historians, representatives of the business community and collectors, but also by the artist’s relatives, i. e . his neph‑ ews with children, grandson and greatg randson. They came to the vernissage from France, Russia and Israel. — O ur family is very grateful to the Belarusians for the way they treat my grandfather’s art. We are very proud of it, — said Iv Dyulak, the artist’s grandson. — I t is important for our family that representatives of different branches of the Zarfins — from Russia, Israel, and France — met for the first time in the grandfather’s homeland. It is a great happiness for us. This is my third visit to Belarus, and Smilovichi has become my native place. This time I’ve come with my daughter. My Russian relatives have also

The exhibition in Minsk presented more than 50 works by the author. Among them there were three paintings from the funds of the National Art Museum, the rest was from the private collections. In particular, 15 paintings were purchased by a Belarusian private company from the artist’s daughter.

brought their children to introduce them to their historical homeland. — F aïbich-Schraga had three brothers and two sisters, but they all left Smilovichi for different reasons. Our family is scattered all over the world. We are very grateful to Belarus, the National Art Museum, which brought us all together, — said the artist’s granddaughter Ella Zarfin.

Creativity of Schraga Zarfin and his biography are still being studied by art historians. In his paintings he tried to convey the spiritual and philosophical problems that were of concern to him. Although he mostly painted French land‑ scapes. The paintings that were presented a t the current Minsk exhibition, say the least, were mesmerizing. Landscapes made in blue-green tones, got you in‑ volved, as if inviting the viewers to walk in t he fields and mountains of France, walk under the vaults of temples, admire the sea. Some works depicted rural life, there

were still-lives. Sketches of fabrics were also of interest, because it is not without reason that the artist in the 1930s became one of the most successful designers in the textile industry. It is known that he made a number of sketches for Coco Chanel who was beginning her career.

The exhibition also featured the master’s personal belongings: a note pad, a palette and a paint box, fam‑ ily photos, documents, recollections of Chaïm Soutine. Yes, he had known this artist since childhood, because they grew up in the same town and were on friendly terms in Paris. — The exhibition is very diverse. Zarfin is a fascinating, charming, mysterious artist. His work is interpreted in many different ways. I like the statements of French researchers who say that his paintings are designed to bring harmony to the soul. Indeed, they have a strong emotional impact on the public. The artist attracts attention, he causes interest, although in 2012 nobody knew about him yet. We are very pleased that the personal exhibition of Zarfin was held in our museum,— s aid leading researcher of the National Art Museum of Belarus Nadezhda Usova.

The exhibition included original tours, lectures from art historians, which helped to get better acquainted with the work of one of the artists of the Paris school. Zoya Kotovich’s film about Schra‑ ga Zarfin was shown daily. As part of the exhi bition project, the first artist’s cata‑ logue in Russian has also been published. — Zarfin’s art has always aroused keen interest among the Belarusian public at all exhibitions dedicated to the Paris School. His often mysterious paintings reflect the long and difficult way of spiritual quest the artist has covered and which he leads his viewer to,— said Yury Abdura‑ khmanov, chief curator of the project. —Schraga Zarfin, as a multicultural and multi-national figure, is a wonderful embodiment of the openness to the world that we want to promote here and now, relying upon the national cultural heritage, — added Alexander Tsenter, Chair‑ man of the A‑100 Supervisory Board. —

Born in Belarus and having lived most of his life outside the country, Zarfin has become a citizen of the world, so his creative work is the embodiment of cultural t ies that exist between Belarusian and foreign art. We hope that our acquisition of Z arfin’s works and their display in Belarus will become a new stage in the development of these contacts, — he said. …Today a reference to the Belaru‑ sian town of Smilovichi can be found in any more or less self-respecting encyclo‑ pedia — the famous artist Chaïm Sou‑ tine was born there. Several years ago, thanks to the enthusiasm of museum workers and the support of UNESCO, a small exposition dedicated to Soutine was opened in Smilovichi.

Another native of Smilovichi and Soutine’s friend, Faïbich-Schraga Zarfin, who was also a representative of the ar‑ tistic movement known as the “Paris School”, did not become so famous. And almost nobody knew about him in Be‑ larus until recently. Fortunately, thanks to the “Belgazprombank” project to create a collection of artists of the Paris School — natives of Belarus, canvases of Chagall, Soutine, Kikoin have returned to the country. And Zarfin’s!

Biography with different color shades

Schraga Zarfin was born to a wealthy Jewish family. His father owned a leather workshop and was a very educated man, who used to read Turgenev and Tolstoy.

Throughout his life Zarfin lovingly re‑ membered his childhood years spent in S milovichi. According to friends and rel‑ atives, he could spend hours telling about t he place, about the forests surround‑ ing it, about the Volma, in its waters he u sed to bathe as a boy in summer and to skate on the frozen river in winter… One day the boy fell into an ice-hole and hit his head hard on its edge. Fortunately, he was rescued. Telling about it many years later, the artist, not without pride. showed a big scar on the back of his head.

In his early childhood, Schraga used to draw with enthusiasm, covered the pages of his father’s office books with his drawings. Despite the difference in so‑ cial status, Soutine’s and Zarfin’s fathers were friendly. Perhaps because of this,

Soutine, who had already been studying at Vilna Art School, allowed little Schra‑ ga to watch him work. The delighted boy started painting with even more enthu‑ siasm. There are reports that he was allowed to draw a figure of an angel to decorate the Summer Theatre in Smi‑ lovichi. Apparently, after that Zarfin’s father gave in and told him: “Well, try to become an artist, like a young Soutine.

In 1913, Schraga Zarfin entered Vilna Art School. His further life reminds of an adventure novel. In 1914, he went to Pal‑ estine, which at that time was part of the O ttoman Empire. For about two years young Schraga lived and worked in a kibbutz: in the fields, doing march drain‑ age, hungry and suffering from heat and c old. Then he entered the Bezalel School of Arts in Jerusalem. In 1918, Palestine became a British protectorate. Zarfin was drafted into the British army. Later, the artist recalled with humor that it saved him from starvation, because for the pre‑ vious two years his only food was figs.

I n September 1920, Zarfin was dis‑ charged. He wouldn’t stop painting. Al‑ most immediately after he came back, he p articipated in an exhibition organized by the new Jerusalem authorities and critics specified his paintings. The young artist had many friends in Jerusalem, some of whom later became major po‑

The artist achieved an amazing light of the paintings by using gouache and oil

litical figures in Israel or famous artists. W hen in 1923 Zarfin decided to go to Germany to take painting lessons from the famous Max Liebermann, they per‑ suaded Schraga to stay. However, he did g o to Europe — first to Berlin, where, among other things, he participated in the exhibition “Berliner Sezession”, and then to Paris. In the capital of world art, he got closer to artists, many of whom came from the Russian Empire. Accord‑ ing to Zarfin, at that time he understood t hat he still had a lot to learn. Schraga ru‑ ined most of his early works and started t o tirelessly visit museums, galleries and exhibitions. In Montmartre, he met Sou‑ tine. Chaïm was simply obsessed with p ainting, but lived so poorly that Zarfin decided to work anywhere and to do any‑ thing to avoid such a fate. The two fellow c ountrymen went different ways again.

All that time Zarfin did not forget about painting. He wanted to partici‑ pate in the exhibitions at the Salon of the Independent. Soutine, whom Zarfin found in Paris in the 1930s at the request of his family (“We have no information about Chaïm” — wrote the parents of Soutine to Zarfin), in every way encour‑ aged Zarfin to do painting and gave him some valuable advice. According to the memoirs of Lilian, Zarfin’s daughter, Soutine visited their home quite often.

In 1939, the Second World War broke out. Zarfin was called up for military service. Fearing Nazi repression, his wife and their little daughter walk to the south of France. However, quite soon, the Vi‑ chy regime signed a truce agreement with H itler and France was divided into two zones. The French army was disbanded.

Demobilized Zarfin managed to find his family. Together they hide away first in the town of Brive and then in Lyon. The owner of the house on Rue Street in the 14th quarter of Paris, where the Zarfins used to live before the war, seized the opportunity to get hold of their apartment. The entire fam‑ ily archive, all the property and Zarfin’s paintings, created before 1940, went missing. According to the artist himself, there were about 300 of his works, i.e. paintings, watercolors, sketches, in the apartment. In addition, Zarfin had a small collection of works of his friends a rtists, perhaps, Soutine.

The persecution of Jews forced the Zarfins to move to the outskirts of Gre‑ noble. However, even at that time Zarfin m anaged to exhibit: in November 1941 in the gallery Notre Dame in Grenoble, in March 1942 in the “Artists’ Shelter” in Lyon and in July of the same year — in the Lyon gallery “Folklore”. At that time he experimented a lot with gouache, of‑ ten mixing it with oil paints. His painting b ecame more stable and at the same time more disturbing, more expressive.

The small apartment of the Zar‑ fins in Grenoble was one of the secret addr esses of the Resistance, and when the danger of falling into the hands of the Gestapo increased, the Zarfins moved to a small village in the Alps, where they quickly made friends with the lo‑ cal peasants. The painter continued to w ork hard. In 1945 Zarfin presented to the public a personal exhibition of works created during the war. The spouses took their daughter away from the monastery and returned to Paris.

However, having been deprived of their apartment and all their property, they found it difficult to make both ends meet. Fortunately, the relatives from America helped with money, and his friends — artists shared the paints and canvases with Zarfin. In war-torn France there was almost no work, but the artist didn’t get discour‑

aged — and kept on painting… And almost stopped exhibiting. Critics and the public started to gradually forget about him. His daughter Lilian said that Zarfin was very reluctant to part with his works and sold them only to a very narrow circle of collectors. Sometimes, when they had no money to buy even bread, his wife sneaked away one or two paintings for sale. The fate of many of them is unknown today.

Paintings that stun with their music…

In the 1950s, the artist often came to Normandy, particularly to the town of Honfleur, which is depicted in several of his paintings, many drawings and sketches. It was at that time that Zarfin created a number of works figuring churches and cathedrals in Paris and its suburbs. Critics noted those works, and pointed out that “Zarfin has found un‑ known so far colors and shades. The art‑ ist has climbed to the top of art”.

At that time Zarfin cozied up to a number of artists of the Paris school, i.e. Aberdam, Ancher, Pressman, Gar‑ finkel, brushed up his acquaintance w ith fellow countrymen Kikoin and Kremen.

Since the second half of the 1950s, the interest in Zarfin’s paintings was steadily growing. In November 1954, the General Directorate of Fine Arts and Literature of France bought one of the landscapes of Zarfin for state museums. The famous philosopher and art historian Étienne Souriau, who was teaching at that time at the Sorbonne, dedicated one of his university lectures to Zarfin and wrote several articles about him, he called his work “one of the highest achievements of modern art.” And art critic Emmanuelle Re wrote about the artist the following: “Zarfin reminds me of the great Russian poet F. T yutchev, for whom the outside world was only a fleeting and shortlived vision, briefly arising from the chaos and immediately disappearing in it…”

In 1958, about 30 works by Zarfin were presented to the public at the exhi‑ bition in the “House of Intellectuals” in Paris. Several famous French collectors bought them. Today, the largest number of Zarfin’s paintings and gouaches is in the collection of Paul Rampeno — about 90 works! Rampeno stressed some spe‑ cial musicality of works by Schraga Zarfin: “In Zarfin’s painting… one can feel the same grandeur that shocks us when we listen to Bach”.

In 2012, Zarfin’s grandson Iv Dy‑ ulak visited Belarus. According to him, he was happy to visit his grandfather’s homeland, and especially Smilovichi. At the opening of the exhibition “Art‑ ists of the Paris School from Belarus” in the National Art Museum of Belarus, Iv Dyulak gave a gift from his family to the museum, i.e . two paintings by Schraga Zarfin, which can be seen today in the museum collection.

Portrait against a backdrop of war a coat, a hat, a subtle smile in the cor‑ ners of the mouth. In the photographs Zarfin is a typical Frenchman, one would never recognize him as a native of the town of Smilovichi near Minsk. Meanwhile, the favorite with the Paris‑ ian public recollected for the rest of his life his parents’ house, the Volma River and barefoot childhood to the long folk songs in the Belarusian language.

Zarfin was one of those creators who never gave up practical affairs for the sake of high art. For example, he managed to be in the army twice. In his youth he served in the British army, and in 1939 — in the French one. Amaz‑ ingly, but it did not interfere with his creativity: the artist painted always and everywhere. Later, an album of draw‑ ings made by him at the beginning of World War II, was purchased by the French government.

Schraga didn’t give up painting when he was hiding away during the Nazi occupation, and his apartment became one of the secret addresses of the French Resistance. That’s a fact that Zarfin’s personal exhibitions were suc‑ cessfully held in 1941, 1942 and 1944 in different cities of France. It was in the war years when critics recognized him as a serious artist.

The painter had his own recognizable style. The press enthusiastically wrote: “…landscapes, flowers and human fig‑ ures… are transformed by a lyrical im‑ pulse, which as if takes them out of na‑ ture and moves into the world of fantasy, o ften severe and fierce. In this world, the contours of objects are transformed into crazy arabesques, and paints become signs of some matter resulting from a subtle and skilful alchemy”.

Too much oil makes gouache better

Zarfin painted quickly. Bright fas‑ cinating paintings were created within one morning. But this was preceded by long preparatory work. At first, the art‑ ist photographed the places that had in‑

spired him. Then he would make many small sketches. And only after it he would start to make the “final draft”. He got up very early, waxed the parquet, then poured tea and started painting. By the way, not always with a brush — often he did it with his fingers.

A unique feature of Zarfin’s writing is in the mixture of paints. His personal discovery was the combination of oil and gouache. Due to this, сolors on the canvases acquired a special depth and even glow, which is so often noted by critics. — D uring his travels, he visited all the churches. All religions were good for him. Temples gave him harmony and joy, especially if there was an organ. Father was very fond of Bach’s music. He needed an accompaniment to draw,— the painter’s daughter Lilian shared her memories

To Picasso — in a neighbourly way

For a long time Soutine stayed as a guiding personality for Zarfin. Schraga followed his friend to Vilno, and then to Paris. However, their creative paths went quite differently. Chaïm remained an unrecognized penniless genius, and his countryman got fame and money as the author of sketches for fabrics. In the 1930s, the best fashion houses in Paris were on the waiting list for the opportu‑ nity to work with him. — It’s not true to say that in those years Zarfin was wasting his talent. What he was doing, influenced his future paintings — s aid Nadin Neshaver, an expert on the Paris school 1905–1939.— When you look at his paintings, you get the impression that the picture and print are superimposed. The colours shine on them.

It seemed that the artist had reached his ultimate dreams: his beloved wife and mite of a daughter, good income, a beautiful apartment near the Parc de Monsoûry in the fashionable for those times 14th district of Paris. His neigh‑ bors are Picasso, Dali and Hemingway. But noisy parties, at which all the crea‑ tive elite of the French capital gathered, were alien to Zarfin who was not much of a companion. Only his childhood friend Chaïm Soutine knew that to feel happy he lacked one thing, i. e.painting. When they met again in 1936, the fellow countryman reminded about the true purpose of an artist and advised to start everything from scratch. Schraga took the words of his elder comrade literally: he destroyed all his works.

The mysterious Zar fin revealed himself in the movie

We are talking, of course, about the film “Wandering Star from Smilovichi” by Zoya Kotovich and Yury Abdura‑ khmanov.

If the films about Chagall most often tell about already known facts, the film about Zarfin is a research in the form of documentary filmmaking. The film is watched in the same breath and presents unique facts collected by the authors during a two-year filming expedition to France, Hungary, Lithuania, Israel and Belarus.

It was worth seeing at least to get acquainted with Zarfin’s work, about which even the ubiquitous Internet has a very modest idea. The fact is that most of the artist’s paintings are kept in pri‑ vate collections. A friend of Zarfin, who collects his works, lives in Hungary but it was not easy to video them. The creators of the film agreed to do the shootings in a certain light and not to touch the paintings. So the images of winter landscapes, bunches of flowers, human figures which we see in the film have been collected throughout Europe like grains of gold. One can’t see them anywhere else.

And it’s really worth seeing. Even in his lifetime Zarfin was written about as the painter who “found unknown to this day colors and shades”, “has become a real phenomenon in the world of art.” His landscapes were used by a Swiss doctor for treatment of neurosis and depres‑ sive disorders. And collectors say that there is a musicality in Zarfin’s works, which places him alongside with Bach. Apparently, this is not only a talent, but also achieved through suffering creativity, which is can be comforting. As a teenager, he flew his parents’ nest and settled in Paris years later. He went through two wars. His parents died in the Smilovichi ghetto. And he himself continued to paint, even hiding away from the Nazis, during the war he par‑ ticipated in exhibitions.

There are unique film frames of fam‑ ily chronicles in the film. Recordings of Schraga’s voice, who is reading poetry and singing a lullaby in Russian and Belarusian. He never visited Smilovichi again, although he loved his village and often talked about it. Zarfin also wrote memoirs about Soutine. He was the only one who described his father and brother. According to his memoirs, re‑ searchers from different countries, who came to “Soutine Readings” in 2015, were able to find the exact place where the artist’s house used to be situated. In short, Zarfin is a significant figure, and it is amazing that his name is only now beginning to sound anew.

That’s him, the most Belarusian of Parisian artists. Time puts every‑ thing in its place. The place of Zarfin is in Belarus. By Vengiamin Mikheyev

Long-awaited premiere

TThe film studio “Belarusfilm” pre‑ sented a trailer for the film “The Ad‑ ventures of Prantish Vyrvich”, which is based on the novel by Lyudmila Rublevskaya. This is one of the rare do‑ mestic film projects, which involves only Belarusian actors.

General Director of the film stu‑ dio Vladimir Karachevsky, who also acted as general producer of the project, called this historical-adventure film “Belarusian garde-marines”. Alexander Anisimov directed the film.

The film itself tells about the adven‑ tures of the Belarusian nobleman and his friends.

This is the only historical and fan‑ tasy picture of domestic production and the first after “Anastasiya Slutskaya” film on a historical subject. The main actors came to the presentation, includ‑ ing Lyudmila Rublevskaya. — It was very important for me to show my version of Belarus from a his‑ torical point of view and my character, a n iconic Belarusian, and in this way to destroy the stereotypes that still exist, — said Lyudmila Rublevskaya.— Frankly speaking, I did not really believe that the project would come true. But I be‑ lieved it, apparently, when I saw with m y own eyes a steam-powered tank de‑ signed by Leonardo da Vinci and made b y the masters of Belarusfilm. For me

The film “The Adventures of Prantish Vyrvich” based on the book by Lyudmila Rublevskaya was released in Minsk

as the author, the most pleasant thing is that many people start looking up infor‑ mation about my main characters in en‑ cyclopedias. Then they ask: “Mrs. Lyud‑ mila, where can I find more information a bout Butramey Lyodnik?” I’m even embarrassed to disappoint them that I invented him myself. And in the film, by the way, we show the famous Library of Polotsk. The one that Wacław Łastowski describes in his “Labyrinths”. In the film you will see it in the beautiful embodi‑ ment of our artist Vladimir Tsarikovich.

The creators have almost com‑ pletely abandoned computer graphics. Nevertheless, the picture turned out to be bright and dynamic. Shooting took place in Lida, Nesvizh, Mir castles, in Minsk and Bobruisk. —It took almost a year to shoot the film. We made a lot of amendments, often had to shoot at night,— s aid Ale‑ x ander Anisimov. — We walked along the corridors of the Nesvizh and Mir castles listening, sniffing. There was a feeling that something mystical was taking place next to us. The direction of the film was difficult, but we had a good team, so we were able to make, in my opinion, an interesting film.

Such actors as Ivan Trus, Georgy Petrenko, Veronika Pleshkevich, Ser‑ gey Yuryevich, Vyacheslav Pavlyut, Yevgeniya Anikey, Viktor Manayev, Sergey Savenkov, Konstantin Mikha‑ lenko, Dmitry Yesenevich took part in the film. By Viktoriya Askero

Migratory birds have returned to Belarus. It's a good sign of renewal.

country in heart of europe

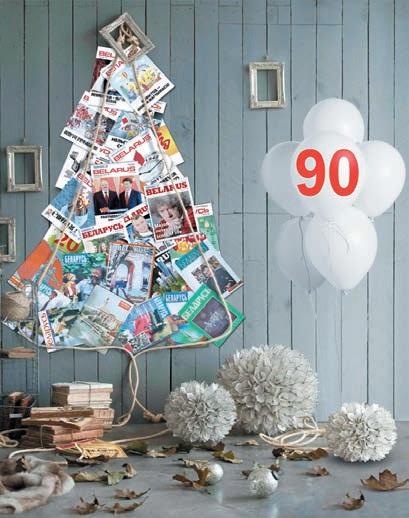

No. 12 (1035), 2019 Magazine for you Беларусь. Belarus belarus Politics. Economy. Culture ISSN 2415-394X No. 1 (1036), 2020 Magazine for you Беларусь. Belarus belarus Politics. Economy. Culture ISSN 2415-394X No. 2 (1037), 2020 MAGAZINE FOR YOU Беларусь. Belarus

BELARUS Politics. Economy. Culture ISSN 2415-394X No. 3 (1038), 2020 Magazine for you Беларусь. Belarus belarus Politics. Economy. Culture ISSN 2415-394X

New Year — N ew opportu N ities Mature age In January, 90 years have passed since the first issue of the magazine "Беларусь. Belarus" THIS AMAZING BOOK WORLD