8 minute read

End of a Sea Power

moving Mignatta hoping that it would fi nd another ship. Th eir wish came true, the steamer Wien of the Austrian Lloyd fell victim of the device.

Th e captured Rossetti and Paolucci were taken on board of the Viribus Unitis where they were surprised to learn that the fl eet had been transferred to the State of the Slovenes, Croats and Serbs a dozen hours before. Th ey told Janko Vuković de Podkapelski, the last Austro-Hungarian commander of the battleship, who on the preceding day had been promoted to kontraadmiral by Zagreb, that they had attached a magnetic mine to the ship. Vuković immediately ordered abandon ship, the two Italians jumped into the water where they were picked out later by one of the boats of the Viribus Unitis. When the explosion did not occur at the time indicated by Rossetti, Vuković and his men returned to the battleship, bringing the two Italians with them. At 6:30 a.m. (other sources state 6:44 am) an explosion shook the ship when the magnetic mine detonated. Th e outraged sailors wanted to force their Italian prisoners to go down with the ship, locking them in a cabin. Vuković barely succeeded to talk them out of this inhumane act. Fourteen minutes after the explosion the Viribus Unitis capsized and sank. Rossetti and Paolucci survived the sinking, while their savior, Vuković perished. Th e exact number of the victims is unknown, because on those chaotic days no one administrated the number of the men on board or the number of the survivors. In the Pola cemetery there are around forty graves of the victims of the sinking of the Viribus Unitis. Estimates range between 50 and 400 deaths, the truth may be closer to 50.

Advertisement

On the sketches of the wreck made by the Italians in the 1920s it is clearly visible that the edge of the armored deck separated from the side shell plating which enabled the fl ooding of compartments above this deck, as had occurred in the case of the Szent István. Allegedly the watertight doors which had been closed and sealed at the start of the war were opened by the celebrating crew, which can help to explain the rapid sinking of the battleship.531 Th e wreck was broken up by the Italians in the 1920s. Some parts of the ship are now on display in Venice: an anchor, together with the Tegetthoff’s anchor and a small section of the bow.

Rossetti and Paolucci as prisoners of war were taken to a hospital ship. Th ey were freed when the Italian Navy took control of Pola on 5 November. Th ey were presented with gold medals for bravery and they were awarded more than 1 million Lire from the Italian government as a reward for their services. Th e jealous Costanzo Ciano, the commander of the MAS fl otilla in Venice demanded a part of the reward for himself stating that he had been co-inventor of the Mignatta. Due to Rossetti’s protest Ciano was deprived of the reward.532 Rossetti, who felt remorse, gave a great part of his reward of 650,000 Lire (1 percent of the value of the Viribus Unitis) to the widow of Vuković. Th e money was used to establish a trust fund for widows of other war victims. Rossetti later wrote a book and he off ered the revenue to the family of Vuković. With the advent of the Fascism in Italy he founded an Anti-Fascist movement and later had to leave the country. Th anks to his activity the Italian government revoked his gold medal during the Spanish Civil War. Raff aele Paolucci, now conte di Valmaggiore, followed a political career during the Fascist regime beside his medical career, although he was rather a Monarchist than a Fascist. After his rehabilitation he continued his political career from 1953 until his death in 1958.

End of a Sea Power

After the turn over the fl eet to the National Council of Zagreb, the non-South Slavs had to abandon the ships they had under their control. Over the next several days they had to organize the homeward journey of the other nationalities amidst the chaos. It was not an easy task, at least in the case of the Hungarians, because the majority of the Hungarian offi cers left Pola immediately after the turnover of the fl eet, leaving behind their men. Only a handful of junior Hungarian offi cers remained in Pola to help organize the return of the Hungarian sailors which took place in the fi rst days of November. Th e Hungarian committee which organized the return journey made an advertisement which was published in the newspapers of Pola thanking the South Slavs for their help in repatriating the sailors.533

Th e Allied Powers naturally did not recognize the turnover of the fl eet, the Italians being especially angry. From 30 October, armistice talks took place at Villa Giusti outside of Padua between Italy and Austria-Hungary. Th e Austro-Hungarian

— 148 —

Navy was represented by Prince Johann Liechtenstein and Georg von Zwierkowski. Th e armistice was signed on 3 November. Th e Armistice of Villa Giusti authorized Italy to transfer fi ve battleships, three cruisers, eight destroyers and a dozen torpedo boats among other units to Venice. Th is was done in March 1919. In this month the Italians held a victory parade in Venice, on this occasion on the masts of the former Austro-Hungarian ships the following signal was fl ying: “We have revenged Lissa”.534 Th e armistice also authorized Italy to occupy all Austro-Hungarian Adriatic ports within 48 hours.535 Between 4 and 9 November, the Allied Powers occupied the former Austro-Hungarian ports, and (almost) all the warships came under Italian fl ag. Th e Italian government in the next months vehemently protested against the turnover of the former Austro-Hungarian Navy via the Swiss Embassy of Vienna, considering the transfer unlawful.536

On 7 November, her South Slav crew sailed the battleship Zrínyi to Buccari, a port not yet occupied by the Italians. Days later the US Navy seized the ship, which came under US fl ag as USS Zrínyi until the distribution of the former Austro-Hungarian fl eet. In the Cattaro naval base all the fl ags were cut in small stripes, which the crews brought home to prevent them falling in the enemy’s hands as a last act of defi ance.537

Negotiations to determine the fate of the former Austro-Hungarian fl eet began on Corfu in early November 1918. Th e leader of the Italian delegation, contraammiraglio Ugo Conz, concluded that the former Austro-Hungarian Navy in Yugoslav hands would represent an unacceptable threat to Italy. He said: “Th e Austro-Hungarian fl eet must either be given to Italy or destroyed.”538 Th e representatives of other powers, especially the British showed some sympathy to the South Slavs, because they were disgusted by the arrogance of the Italians. Nevertheless, it was out of question that any of the victors would accept the transfer of the fl eet.539

Th e fate of the former German and AustroHungarian fl eets generated considerable debate and disagreement. Th e interned German fl eet was scuttled by the German crews of the ships in Scapa Flow in June 1919. After this act the debates continued over the fate of the former Austro-Hungarian fl eet, and the Allies postponed the fi nal decision to 1920. Th e distribution of the fl eet was made in 1920 by the Naval Allied Commission of Disposal of Enemy Vessels (NACDEV). Th e overall spirit of naval disarmament which culminated in the Washington Treaty of 1922 sealed the fate even of the most modern battleships. With the exception of the three Helgoland class cruisers, all of the former Austro-Hungarian warships larger than 1,000 tons were scrapped or destroyed in the early twenties.

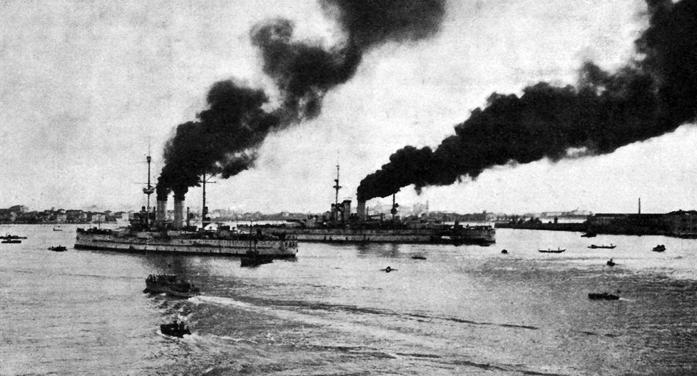

65 Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand and Tegetthoff paraded in Venice in March 1919

— 149 —

Th e three units of the Radetzky class and the two remaining dreadnoughts were distributed between Italy and France in May 1920. All the three Radetzkys were transferred to Italy. Th e Tegetthoff, which had been in Italian hands since March 1919, was offi cially transferred to Italy and the Prinz Eugen was transferred to France. Th e distribution of the two dreadnoughts was not lacking a certain symbolism. Th e eponym of the Tegetthoff, Wilhelm von Tegetthoff had defeated the Italian fl eet at Lissa, while the eponym of the Prinz Eugen, Prince Eugene of Savoy had achieved victories over the French during the War of Spanish Succession. All fi ve battleships were transferred with the proviso that they should be scrapped within fi ve years.

Th e Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand was scrapped at Ancona in 1921-1922, the Radetzky at Pola in 1921-1922 and the Zrínyi also in 1921-1922. In the case of the Tegetthoff the Italians tried to stall for time, fi nally she was demolished in 1924-1925 after their former allies had put pressure on Italy. Th e guns and other valuable fi ttings were removed from the ships before sending them to the breakers yard. Some equipments of the fi re control system of the Tegetthoff are now on display at the Technical Museum of Milan. Th e French intended to use the Prinz Eugen as a target ship. She was towed from Pola to Toulon, where she arrived in September 1920. In the fi rst months of 1921 her guns, machinery and all other fi ttings were removed from her. In May 1921, the Prinz Eugen was used as a target ship for aerial bombs. She withstood well the bombing, even the largest bombs infl icted little damage on her. Next, in January 1922, her torpedo protection system was tested with a torpedo warhead. As in the case of her sisters, the torpedo bulkhead could not withstand the underwater explosion, and the entire compartment behind it was fl ooded. Because the water was leaking through the makeshift sealing of the bulkheads which had been made after the removal of the pipes and electric cables, neighboring compartments were also fl ooded and the ship sank in the shallow water. Th e Prinz Eugen was salvaged and repaired in Toulon. On 28 June 1922, she made her fi nal journey. She was towed to ten nautical miles off Toulon, where she was used as a target ship for the 34 cm and 30.5 cm guns of the French dreadnoughts which sank her. Th is is how the story of the last two and largest Austro-Hungarian battleship classes ended. Th eir construction had cost the taxpayers of the Empire 360.4 million Kronen, equivalent of 109 metric tons of gold.