Adjunctive

therapy or standard of care?

Contents: 2-3 DCBs: Past, present and future – Luca Testa

4-5 High-bleeding risk patients and DCB PCI – Tuomas Rissanen

Adjunctive

Contents: 2-3 DCBs: Past, present and future – Luca Testa

4-5 High-bleeding risk patients and DCB PCI – Tuomas Rissanen

The use of drug-coated balloons (DCBs) for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is seen as one of the most exciting areas of development to have emerged in the field of interventional cardiology within the last decade. In a statement that followed May 2023’s EuroPCR meeting (16–19 May, Paris, France), which heard new evidence for the use of DCBs in a number of clinical scenarios, PCR acknowledged that DCB PCI “looks set to assume growing importance in the years to come” adding that the potential for increased use of these devices in clinical practice is “considerable”. In this article, Luca Testa (IRCCS Policlinico S Donato, Milan, Italy) outlines to Cardiovascular News the contemporary applications of DCB technology in coronary interventions, discusses how the devices are viewed in clinical practice guidelines, and highlights some of the evidence supporting their use.

involving the future use of DCBs, which can include DCB-only PCI or hybrid approaches—combining DCBs with drugeluting stents—contend that there are a range of scenarios in which the use of these devices can produce favourable results and counteract some of the limitations of current-generation drug-eluting stents.

“There is a huge amount of literature where researchers have tried to establish several indications for the use of DCBs,” Testa comments. Nevertheless, he notes, the only approved current indication, as endorsed within European practice guidelines, is for the treatment of in-stent restenosis, either caused by a bare-metal or drug-eluting stent”.

Research has shown that after stent implantation with a second-generation DES, the rate of target lesion revascularisation (TLR) within five years is around 10%, increasing to 20% within 10 years. Redo PCI for in-stent restenosis has been associated with substantial rates of recurrent restenosis and worse survival compared with PCI of de novo coronary disease.

“In the most recent European guidelines the indication to treat in-stent restenosis with a DCB has exactly the same level of recommendation as the treatment of in-stent restenosis with a drug-eluting stent,” Testa explains. “In other words, if you have a patient with in-stent restenosis, you can use

a drug-coated balloon or a drugeluting stent. Either way is endorsed by the guidelines”.

Though in-stent restenosis remains the only approved indication, “practice has gone way beyond this indication, especially in the treatment of small vessel disease or even native disease in coronary arteries, i.e. without a previous stent implantation,” Testa explains.

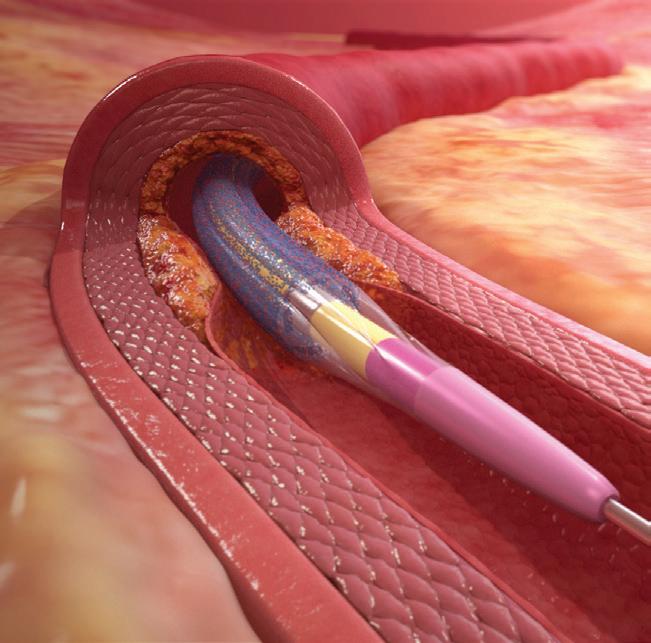

The hypothetical advantage of using a DCB in the setting of in-stent restenosis is “very clear” according to Testa, stemming from the fact that there is no additional permanent metallic implant to be left in the treated vessel. “In other words,” he says, “instead of putting a second layer of metal inside a previously implanted drug-eluting stent or bare-metal stent, you can just prepare the lesion and deliver the drug.”

Plausibly, he says, the less metal that is implanted, the higher the expected chance of long-term patency. “To look at it the other way around, the more metal you place into the artery, the higher chance you have of a further restenosis. So, the idea is to treat the failure of a stent without another stent.”

In terms of the existing evidence underpinning the use of DCBs for instent restenosis, Testa points to the work of groups in Spain—the RIBS study programme—and in Germany—the ISAR-

6-7 Harnessing the strengths of DCBs and drug-eluting stents – Jorge Sanz Sanchez

DESIRE trials—as being key to influencing thinking in this arena. “They tested the efficacy of DCBs against plain balloon angioplasty but also against drug-eluting stent implantation for patients who had in-stent restenosis, and from these two big groups of publications we have the evidence that this technology might be at least as good as drug-eluting stents,” says Testa of this early work. Later studies, including PACCOCATH ISR 1 and 2 and PEPCAD have also demonstrated the efficacy of DCBs in the treatment of in-stent restenosis as compared to stent implantation.

While in-stent restenosis remains the predominant context for the use of DCBs presently, there is a rapidly growing interest in the use of DCBs in the treatment of de novo coronary artery disease, and in a wider variety of indications. Testa points to bifurcation lesions (in particular the treatment of the side branch) and native coronary artery disease as two such settings where DCB usage will expand in the future, though significantly more studies are needed in this regard, he cautions.

“We are working in this respect. There are a lot of studies ongoing, and a lot of data will come in the next couple of years, but nowadays we are still in the phase of understanding what the balance is between the risk and the benefit of “leaving nothing behind”, i.e. just using the DCB, which is basically a carrier of the drug,” Testa explains. “With a drug-coated balloon you do not do the angioplasty, you do not inflate the balloon to enlarge the artery, what you basically do is just deliver a drug. The trials are ongoing, and we need to wait for the follow-up.”

Testa recommends that close reading of the RIBS IV trial—comparing outcomes after DCB use versus drug-eluting stent implantation—is fundamental for any interventional cardiologist seeking to implement DCBs into their practice. Threeyear results from the trial were published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions in 2018. “The message coming from this trial is that rates of cardiac death, myocardial infarction,

as well as stent thrombosis at three years were similar in the two arms,” he explains. “In other words, you have a choice now to decide whether you want to use another stent or a drug-eluting balloon.”

Commenting on how these data influence his practice, Testa explains that in the vast majority of in-stent restenosis cases he will favour using a DCB-only strategy. This requires a different approach compared to what you would do to implant another drug-eluting stent, he explains, noting that with the DCB-only strategy it is necessary to prepare the lesion in a different way, minimising the possibility of having a residual small lumen. In sum, it is necessary to achieve a good angiographic result before the use of the DCB.

“You use, for example, cutting balloons, scoring balloons, and then you use drugcoated balloons,” says Testa of the DCBonly approach. “When opting for a strategy of implanting another drug-eluting stent, many operators tend to accept a suboptimal lumen before placing another stent. In my practice, I would say in 99% of in-stent restenosis cases I just go for a DCBonly strategy.”

Trials to look out for

Bookmarking the studies to watch in this arena, Testa picks out the EASTBOURNE registry, describing it as the largest study of drug-coated balloons yet to have been undertaken. The study is a prospective, multicentre registry, enrolling more than 2,000 real-world patients treated with a sirolimus-coated balloon, more than half of whom have presented with de novo lesions. “Now we are analysing the subset of patients where they were treated for native coronary artery disease” explains Testa. “This trial will give us a lot of information concerning what we can expect from this technology.”

Elsewhere he singles out the TRANSFORM I and II trials, the first of which is a randomised trial focusing on small-vessel de novo coronary lesions, and the latter an open-label randomised trial in the native coronary vessels.

“The TRANSFORM I trial was a more mechanistic than clinical trial: it supported the superiority of a paclitaxel-eluting balloon over a sirolimus balloon in terms of angiographic parameters; the much larger TRANSFORM II will provide clinically oriented evidence” says Testa.

Reflecting on his expectation for the future for the use of DCBs in PCI, Testa comments that he believes they will be an

What the guidelines state: Drug-coated balloons are recommended for the treatment of in-stent restenosis of bare-metal stents or drug-eluting stents.

Source: 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ ehy394

important tool on the shelf in future.

“The possibility of treating our patients without leaving a permanent prosthesis will be more than welcome,” he explains. “I honestly believe that the research that is already ongoing will definitely give the drug-eluting balloon technologies the appropriate place and space that they deserve in the cardiovascular arena. In the past we used too many stents, that is my thinking. Nowadays we are in the process of changing this attitude to a more tailored approach: the DCB technology will surely challenge the paradigm according to which PCI means drug-eluting stent implantation; to do so, we are collecting experience and data”.

Luca Testa is an interventional cardiologist practicing at IRCCS Policlinico S Donato in Milan, Italy, where he works as head of the Coronary Revascularization Unit and head of the Clinical Research Unit within the Department of Cardiology.

I honestly believe that the research that is already ongoing will definitely give the drugeluting balloon technologies the appropriate place and space that they deserve in the cardiovascular arena.”

Luca Testa

“The subset of patients with high bleeding risk is a very important population,” Tuomas Rissanen (North Karelia Central Hospital, Joensuu, Finland) tells Cardiovascular News. Representing around 40% of patients coming to cath labs for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), Rissanen comments that this remains something of an underappreciated population among interventional cardiologists. And, given that much of the world is seeing populations gradually age over time, strategies to treat older patients with increasingly complex comorbidities are likely to be called upon more often by physicians in future.

THE GROWING USE OF DRUGeluting stents, which initially came with some concerns over stent thrombosis, drove clinicians to administer at least one year of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)— involving the combined use of aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor to reduce recurrent ischaemic events—after the completion of the procedure. However, this long-term strategy comes at the potential expense of an increased risk of major bleeding in highrisk patients. Studies including LEADERS FREE, have emerged showing that a shorterduration DAPT regimen after drug-eluting stent PCI may be safe in selected patients. However, there is also a growing body of evidence that reinforces the use of drugcoated balloons (DCBs) as an attractive and effective strategy as an alternative to stent implantation within this increasingly complex patient population.

“I think that DCBs are very suitable in this patient population,” comments Rissanen, before going on to explain the chief reasons why this strategy may be seen as an appropriate option within the highbleeding risk cohort. “The most important reasons are that leaving nothing behind is very beneficial. If the patient starts bleeding and you have implanted a stent you have to continue DAPT for at least four weeks after PCI. But, if you did not implant a stent then you have the option to cease the antiplatelet therapy.”

Before establishing which is the optimal treatment option, be it medical therapy, PCI with a stent or DCB, or even surgical revascularisation, it is important to understand which patients are at the highest risk of bleeding, Rissanen advises. There are many factors that can determine whether a patient is considered to be at a high risk of bleeding, which include advanced age,

current anticoagulation usage, a history of prior bleeding, presence of kidney failure, the need for future surgery, to name a few.

“The patient must be examined very well. You have to review the medical records and especially the records involving surgery, neurology, haematology, and internal medicine concerning kidney failure, for

example,” explains Rissanen. “If there are abnormalities in lab exams; a low haemoglobin level or low thrombocyte levels, for example, those patients are also at high bleeding risk. We have to examine the patient very carefully and also review them in our labs before deciding whether the patient is at high bleeding risk or not.”

If the risk of bleeding is high but the ischaemic risk is low, Rissanen posits that the optimal strategy may be conservative treatment, meaning that it is better not to do PCI at all. But, he adds, if the patient is very symptomatic and there is severe coronary artery disease present then the prospect of performing a revascularisation procedure comes into the picture. “At this point comes the question of whether to do PCI, perhaps only in the most severely diseased culprit lesions, or in all of the vessels, which increases the risk of stenting some of the vessels.” Whether to refer the patient for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), which does not require DAPT, should also be considered, taking into account the surgical risk of the patient.

DCBs offer advantages over stent implantation in patients at high bleeding risk.”

Tuomas Rissanen

The issue of whether to pursue a conservative treatment strategy or revascularisation is the most important consideration for the physician, Risannen explains. “You might make that decision based on the clinical features and symptoms of the patient, and what is going to happen in the future. If there is going to be cancer treatment, which is very stressful to the heart, or if there is very high-risk surgery, then quite often you have to consider revascularisation before doing a highrisk surgery.”

Evidence of the benefit of a DCB-only strategy in high-bleeding risk patients stems predominantly from two randomised trials, DEBUT and BASKET SMALL 2, both published in The Lancet.

DEBUT is a randomised trial comparing bare-metal stents with DCBs in high-bleeding risk patients. In the trial, the occurrence of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) in stable angina was 0% in the DCB group compared to 11% in the bare-metal stent group. The trial also reported a 13% bleeding rate at nine months among those undergoing treatment with a DCB, compared to 11% among those receiving a bare-metal stent. “That trial showed that the DCB-only strategy is superior to bare-metal stents in terms of revascularisation, but because baremetal stents are largely now left out of the cath lab, we have to prove this with modern drug-eluting stents as a comparator,” says Rissanen.

BASKET-SMALL 2, meanwhile, compared drug-eluting stents to DCBs for the treatment of small vessel disease in 758 patients with acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary disease. The patients who received a DCB for stable coronary disease were given one month of DAPT, while those who had an acute coronary syndrome were assigned to a 12-month regimen. MACE at 12 months was 7.3% in the DCB arm and 7.5% in the drug-eluting stent arm, while major bleeding rates stood at 1.1% for the DCB group and 2.4% for drug-eluting stents. “Twenty percent of that patient population had high bleeding risk and it was shown that DCB is at least as good as drug-eluting stents in this patient population in terms of revascularisation, but there was a trend towards less bleeding in the DCB-only arm,” adds Rissanen, cautioning though that the trial was not powered for this comparison. Rissanen does note however, that it supports the hypothesis that “shortening DAPT is actually beneficial in this patient population”. Registry data from

centres in Finland and Italy have also demonstrated the feasibility of single antiplatelet therapy with a DCB-only approach.

More evidence is on the horizon, and Rissanen singles out the DEBATE trial, of which he is an investigator, as being likely to add significant new data to this discussion. The trial began randomising patients over 12 months ago, and at the time of writing has randomised roughly 20% of the 530 patients needed to meet the power calculation of the trial. “Currently we only have Finnish centres, but we will have centres from Germany, Spain, France, and maybe from the UK,” explains Rissanen, adding that the trial is anticipated to report 12-month results in around 2026.

antiplatelet therapy regimen between the two groups in this trial,” he says.

40%

Proportion of patients undergoing PCI with high bleeding risk (HBR) characteristics

“Specifically, DEBATE aims to show the benefit of shortening DAPT after PCI by using a DCB-only strategy in high-bleeding risk patients, so on top of having a different method of PCI there is a different dual

Presently, guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) do not recognise a DCB-only approach in de novo lesions, regardless of bleeding risk, but future updates could be guided by evidence from the DEBUT trial and registry data, Rissanen believes. Despite this, the third report of the International DCB Consensus Group, published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions in 2020, acknowledges: “DCBs offer advantages over stent implantation in patients at high bleeding risk.” With more trial data to support this concept coming down the road, DCBs could be an important option for the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease at high risk of bleeding in the future.

Tuomas Rissanen is an interventional cardiologist at North Karelia Central Hospital in Joensuu, Finland.

Advanced age

≥75 years

Comorbidities

Renal disease

Liver disease

Active cancer

Laboratory

Anaemia

Low platelet count

Central nervous system

Stroke, intracranial haemorrhage, brain arteriovenous malformation

Bleeding history

Bleeding diathesis

Prior bleeding or transfusion

Iatrogenic

Oral anticoagulation

Use of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs, steroids

Planned surgery on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), recent trauma or surgery

Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) have been shown to be a viable alternative to stents in a number of clinical scenarios and offer promise in addressing some of the shortcomings inherent in the current generation of drug-eluting stent technologies. Though many physicians see the appeal in the concept of “leaving nothing behind” in the treatment of coronary artery disease, there will be instances in which combining the strengths of both DCBs and drug-eluting stent technologies is likely to be advantageous. “The idea is to get the pros from both technologies in order to improve our results,” comments Jorge Sanz Sanchez (Hospital Universitari i Politècnic la Fe, Valencia, Spain), detailing to Cardiovascular News some of the situations in which this strategy can be applied.

THERE IS A WIDE BODY OF evidence supporting the use of drug-eluting stents in various clinical scenarios, but, as Sanz Sanchez points out, studies have shown “persistent” events resulting from percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using this type of technology. “Drug-eluting stents have been with us for a long time,” he comments. “They perform outstandingly, we know how good they are, and we can use them in a lot of scenarios including patients with stable coronary disease or acute coronary syndromes, as well as really challenging situations such as calcified lesions and left main disease. We have also been able to reduce dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration in high-bleeding risk patients.

“As they have been with us for so long, we have a large body of data already supporting the use of drug-eluting stents, but they have some cons. We know from data that there is a persistent 2% event rate every year. This is constant, even studies at 10-year follow-up show a 2% target lesion failure (TLF) rate for all drugeluting stents.” This suggests, according to Sanz Sanchez, that there is room for improvement, and while this does not, he believes, warrant removing drug-eluting stents from the shelf altogether, a reduced stent strategy could be considered in cases where it can provide value.

“The advantage of DCBs is that they keep the anatomy of the vessel, they keep the vasomotion of the vessel,” comments Sanz Sanchez, adding that there is also, in the case of paclitaxel-coated devices, a degree of positive remodelling seen

in the vessel. “From what we have seen so far from the data that we have from randomised controlled trials in patients mainly with small-vessel, native coronary artery disease, they perform as well as drug-eluting stents in terms of events and TLR [target lesion revascularisation],” he notes.

Despite these advantages, DCBs come with their own drawbacks.

Sanz Sanchez offers the view that they are “not as good as drug-eluting stents in terms of acute recoil”, adding that it is also still important to learn “how to deal with dissections”. Altogether, this adds up to the fact that DCBs should not be simply viewed as an alternative to drug-eluting stents, but as a complementary treatment option for patients—with approaches that harness the best features of both types of device becoming an important consideration when deciding on which approach to pursue.

is important to avoid using very long stents. “The longer the stents the more events they have”, he tells Cardiovascular News, alluding to the fact that stent length is known to predict worse clinical coutcomes. Though these may be some of the best examples of the cases to consider, Sanz Sanchez states that a DCB and drug-eluting stent approach should not be limited to these scenarios in isolation.

“It does not mean that you have to put a DCB and drug-eluting stent in every case,” he explains. “You might prepare the vessel, [and] if there are no flow limiting dissections, the TIMI [Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction] flow grade is good, and the residual stenosis is less than 30%, then you can apply the DCB. If after performing DCB-PCI the result is good, you can keep it like this. If not, you always have the drug-eluting stent and it can be considered as a bailout.”

He sets this against the example of current experience using drug-eluting stents in the treatment of bifurcation lesions, where studies have compared a provisional against an up-front two-stent strategy. “In the provisional strategy you start with one stent, and if the result is not good you put a second stent into the side branch.”

A strategy consisting of the use of a drug-eluting stent and DCB with the aim of reducing the amount of metal implanted and minimising the risk of in-stent restenosis and stent thrombosis could become the solution for very complex lesions.

Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2022

Turning to the scenarios in which a combined approach may be the strategy of choice, Sanz Sanchez points to situations where it

Any approach that combines DCB and drug-eluting stents should be viewed in a similar light, he says, when it comes to thinking about how to deploy this strategy. “We have to see this as complementary and part of one strategy”.

Commenting on whether approaching a case in which you intend to pursue a combined DCB and drugeluting stent strategy should be different from any other type of PCI, Sanz Sanchez says that there should always be the same concept at the centre: adequate plaque preparation. “You have to prepare the plaque not thinking [about] if you are going to finish with a drugeluting stent or a DCB,” he comments, noting that it is important to be “meticulous” in this process. This means sizing the balloon 1:1 according to the distal reference diameter to prepare the lesion, with plaque modification

techniques or plaque debulking devices necessary in the event of the presence of calcification.

Once the plaque has been adequately prepared, three things must be evaluated: TIMI flow grade, assessment of dissections, and measurement of the degree of residual stenosis, Sanz Sanchez explains. “If everything is fine you can apply the DCB, but you must be very meticulous when preparing the plaque,” he repeats.

At present, much of the data underpinning this approach come from observational studies, and more randomised trial data are needed to adequately inform treatment choices. “We first started with DCBs in in-stent restenosis, then we moved to small vessels, and now there are ongoing randomised clinical trials in large vessels, in patients with native coronary artery disease. There are different trials ongoing in this setting,” acknowledges Sanz Sanchez, referring to the growing body of evidence concerning the use of DCBs in different settings. And, more research is now focusing on clinical scenarios including acute coronary scenarios, where this DCB and drug-eluting stent strategy could be applied. “We will run a randomised clinical trial with what we call a reduced stent strategy, with paclitaxel drug-coated balloons in patients with STEMI [ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction]. The idea is not to do a head-to-head comparison between DCBs and drug-eluting stents,” he explains, adding that the aim is to see if reducing the number of stents is non-inferior to what has been practised in these patients for the past 20 years.

Two technologies, one strategy DES DCB &

If the results are good, this will be a strategy that will be practised in most cath labs.”

Jorge Sanz Sanchez

Asked whether he sees this approach as one that will be adopted by more interventional cardiologists in future, Sanz Sanchez offers the view that favourable results from clinical trials will guide practice. “I think if the results are good, this will be a strategy to follow,” he comments. “Everybody would like to have a vessel with a non-permanent scaffold that keeps the vasomotion of the vessel preserved; that you preserve the anatomy of the artery; that you always have an option B or an option C to treat the patient. So, if the results are good, this will be a strategy that will be practised in most cath labs.”

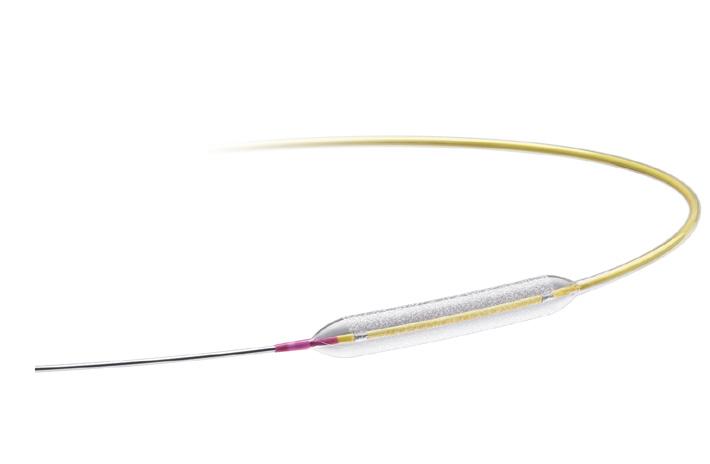

Paclitaxel Coated PTCA Balloon Catheter

Europe

Medtronic International Trading Sàrl.

Route du Molliau 31

Case postale

CH-1131 Tolochenaz

Tel. +41 (0)21 802 70 00

Fax +41 (0)21 802 79 00

medtronic.eu

United Kingdom/Ireland

Medtronic Limited

Building 9, Croxley Park

Hatters Lane, Watford

Herts WD18 8WW

Tel. +44 (0)1923 212213

Fax +44 (0)1923 241004

medtronic.uk

Prevail DCB offers the performance you want for treating complex lesions1:

Superior deliverability†2 deliberately designed to maximise pushability

Rapid drug release1,5 and long-term tissue retention6 facilitated by biocompatible urea excipient3

Excellent safety and efficacy supported by the PREVAIL Study4

medtronic.eu

/PrevailDCB

* Third-party brands are trademarks of their respective owners.

† Bench test data may not be indicative of clinical performance.

1 Prevail Instructions for Use.

2 Based on bench test data on file at Medtronic, D00133639, Rev. B. May not be indicative of clinical performance. n = 5 of each DCB: IN.PACT Falcon™, SeQuent®* Please, SeQuent®* Please NEO, Agent*, MagicTouch™*.

3 Chang GH, et al. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6839.

4 Latib A, et al. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33:E863-E869. PREVAIL study did not have powered endpoints.

5 Cremers B, et al. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:201-206.

6 PS762 preclinical study report: An Evaluation of the Medtronic Drug Coated Coronary Balloon Catheter in a Porcine Artery Model. 2016.

See the device manual for detailed information regarding the instructions for use, the implant procedure, indications, contraindications, warnings, precautions, and potential adverse events. For further information, contact your local Medtronic representative and/or consult the Medtronic website at www.medtronic.eu.

UC202404576-prevail-cardiovascular-news-a4-supplement-en-emea-10531574

© Medtronic. All rights reserved. For distribution only in markets where the Prevail paclitaxel coated PTCA balloon catheter has been approved. Not for distribution in the USA, France, Japan, Canada, or Australia. 2/2024