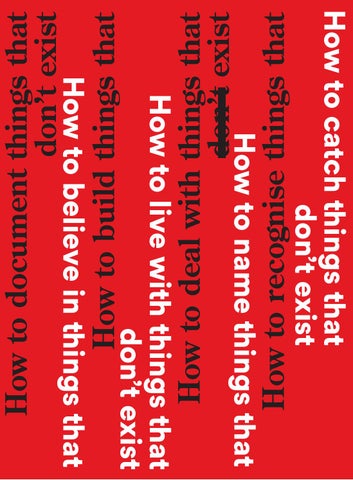

How to recognise things that

How to catch things that don’t exist

How to deal with things that don’t exist

How to name things that

How to build things that

How to live with things that don’t exist

How to (...) things that don’t exist

How to document things that don’t exist

How to believe in things that

31st Bienal de São Paulo

Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t defeat. The Amazon isn’t silly. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Cabelo de Velha. The Amazon isn’t beads. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t nesting. The Amazon isn’t noble. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t leprosy. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a river. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t commodity. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Cabanagem. The Amazon isn’t vertigo. The Amazon isn’t a canoe. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a choice. The Amazon isn’t terror. The Amazon isn’t baroque. The Amazon isn’t incendiary. The Amazon isn’t Tum tá tá. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t serious. The Amazon isn’t calm. The Amazon isn’t sowing seeds. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t eternal. The Amazon isn’t reinvention. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t discord. The Amazon isn’t fleeting. The Amazon isn’t what we want. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t an exposed fracture. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t mourning. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t 38. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t torment. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Serra do Cachimbo. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t 19. The Amazon isn’t make-believe. The Amazon isn’t politics. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t promise. The Amazon isn’t complicity. The Amazon isn’t the edge. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t misfortune. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t the Xingu. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t subtlety. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a corollary of lies. The Amazon isn’t the BR-230 highway. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a threat. The Amazon isn’t Belle Époque varnish. The Amazon isn’t carelessness. The Amazon isn’t fortune. The Amazon isn’t 252. The Amazon isn’t intensity. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a search. The Amazon isn’t highway. The Amazon isn’t Orellana. The Amazon isn’t constant doubt. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t black earth.

The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t accusation. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a mockery. The Amazon isn’t fallibility. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t The Amazon isn’t some two-bit technocrat. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a state of being. The Amazon isn’t a State. The Amazon isn’t absence. The Amazon isn’t concealing. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t vassalage. The Amazon isn’t a silver whistle. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t appearances. The Amazon isn’t experience. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Javindia. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t harshness. The Amazon isn’t of child-bearing age. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t society. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t blame. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t parturient. The Amazon isn’t Rio de Raivas. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t damned. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t campgrounds. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t murderous. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Macondo. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t translatable. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t putrid. The Amazon isn’t beautiful. The Amazon isn’t human experience. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t coziness. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t obedient. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t consternation. The Amazon isn’t insolence. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a ballerina. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t corrosive. The Amazon isn’t monkey business. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t.

The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t first-rate timber. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t tragic. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a media spectacle. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t solitude. The Amazon isn’t the Company of Jesus. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t voluptuousness. The Amazon isn’t uneasiness. The Amazon isn’t the red light. The Amazon isn’t hereditary. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t bleeding from the ear. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t religion. The Amazon isn’t Purgatory. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t jungle! The Amazon isn’t softness. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t misfortune. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Pagan. The Amazon isn’t paternal authority. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t filicidal. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t dementia. The Amazon isn’t civilisation. The Amazon isn’t gluttony. The Amazon isn’t frigidness. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t illogical reasoning. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t justice. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t discord. The Amazon isn’t Malaysia. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t cowardice. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t conspiracy. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t selective. The Amazon isn’t siege. The Amazon isn’t carelessness. The Amazon isn’t companionate. The Amazon isn’t an infamous project. The Amazon isn’t a trap. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a nuisance. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t suffering. The Amazon isn’t a rainforest. The Amazon isn’t the Pervert. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t the Black Forest. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t disillusionment. The Amazon isn’t La Condamine. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t camaraderie. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t civility. The Amazon isn’t a gum tree. The Amazon isn’t a

devastator of spirits. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t the Foreign Ministry. The Amazon isn’t domesticable. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a lavish spender. The Amazon isn’t hollow. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t Medellin. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t lamentation. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t refinement. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t coercion. The Amazon isn’t sordidness. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a model. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a pendant. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t submission. The Amazon isn’t whereabouts. The Amazon isn’t dawn. The Amazon isn’t displeasure. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t concupiscence. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t gospel. The Amazon isn’t guerrilla warfare. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t television. The Amazon isn’t hereditary. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a bellyful. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t gunshot and echo. The Amazon isn’t fecund. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a place of banishment. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a bow-and-arrow. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t.

The Amazon isn’t silence in the woods. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t luck. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t the owner of a rubber plantation. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a mass grave. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t categorical. The Amazon isn’t sacrifice. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t pounds sterling. The Amazon isn’t strange. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t a silver harness. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t spurs. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t recurrence. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t aristocratic. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t fear. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t intimidation. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t captive. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t equilibrium. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t. The Amazon isn’t.

-

-

-

-

How to think about things that don’t exist

How to imagine things that don’t exist

Bienal and ItaĂş present

31st Bienal

How to talk about things that don’t exist

8

••

At first sight, How to (…) things that don’t exist might seem like an abstract question. But perhaps we should think of the title of the 31st Bienal de São Paulo as a contemporary dilemma: how do we live in a world that is in a permanent state of transformation, in which the old forms – of work, of behaviour, of art – no longer fit and the new forms have yet to be clearly outlined? By choosing this curatorial project, the Bienal makes room for a fresh view of its building and its history, with a proposal that leaves the modernist heritage on the sidelines in favour of new approaches and considerations. The book you now hold in your hands is another piece of evidence of the vigorous work realised by the curators and the foundation’s permanent staff. Working in one of the biggest cities in the world, we are responsible for an event that attracts more than five hundred thousand people and is increasingly more committed to the cultural and social circles that surround us. For the past five years, the Education Department has been developing an unparalleled project in teacher training – which, by the end of 2014, will have reached 25,000 educators – and with the participation of new sectors of the public, involving communities and partner communities all over Brazil. At the same time, the Bienal’s travelling programme has brought recent editions of the exhibition to different Brazilian cities, drawing larger and larger crowds. This year, it has the potential to double the number of spectators, so that the 31st Bienal is seen by a total of one million people. Beyond the spectrum of instruction and the spread of culture, we also operate with increasing focus in the area of research. Since 2013, resources have been applied to revitalising the Bienal Archive, consolidating its place as a centre of reference and memory in modern and contemporary art. This process has already begun to bear fruit, which should become more visible in the coming years. Thus, transcending the exhibitions that it stages, the Bienal Foundation is today an institution dedicated to the production of content, the professional training of its personnel and the implementation of a consistent management model. Still, its activities would not be possible without the crucial support provided by the Ministry of Culture, the State Secretary of Culture, the Municipal Secretary of Culture, its partner in the event, Itaú, its sponsors, and a valuable cultural partnership with sesc São Paulo. It is this network of support that allows us to strengthen the bonds between art, the avantgarde and education in order to merit and maintain our place of prestige on the national and international scene.

Luis Terepins President of the Bienal de São Paulo Foundation 9

••

Itaú Unibanco believes that access to culture, in addition to bringing people closer to art, is a fundamental complement to education, developing critical thinking and transforming individuals, society and the country. This is why we invest in and support one of Brazil’s most important cultural manifestations. We are the official sponsor of the 31st Bienal: an event which transforms with each edition, welcoming more people, new ideas and variations of artistic expression which expand the horizons of those who participate in and visit the exhibition. With more access to art and broader horizons, knowledge grows and a variety of opportunities emerge to change the world for the better. After all, people’s worlds change when they have more culture. And the world of culture changes with more people. Investing in changes that make the world a better place is what it means to be a bank made for you. Investing in culture. #thischangestheworld

Itaú. Made for you.

10

••Art and the senses of the world In our contemporary context, rife with symbols and interpretations that blend and clash, questions remain about the possibilities of individuals finding their way. Each of us may feel, to a greater or lesser extent, the urgency of attributing meaning, under the penalty of being overwhelmed by images, texts and sounds that construct reality. Art participates in this symbolic circulation as a protagonist, with its often disturbing presence and commentaries regarding other presences. In this way, the approximation of contemporary visual art production can signify the expansion of its possibilities for reading the things of the world to various audiences. From the perception of this potential comes the partnership between sesc – the Social Service of Commerce and the Bienal de São Paulo Foundation, born out of the compatibility of their missions for spreading and fomenting contemporary art and which has been manifested in joint actions since 2010. The 31st Bienal consolidates this partnership with the development of educational efforts, such as open meetings and curatorial workshops, as well as the co-production of artworks, with selected pieces traveling to sesc locations throughout the state. This shared effort reaffirms the conviction that the fields of culture and art are geared for educational intervention – a real vector of collaboration and the transformation of individuals and society.

Danilo Santos de Miranda Regional Director of sesc São Paulo

11

Contents

pp.38-41 Agência Popular de Cultura Solano Trindade

Inside front cover-p.4 The Amazon Isn’t Mine! Text by Armando Queiroz

pp.42-44 Open Meetings

p.16 Meeting Point, 2011 Bruno Pacheco

p.45 A Toolbox for Cultural Organisation pp.46-47 Educativo Bienal

p.17 Untitled, 1975 Juan Downey

p.48 O que caminha ao lado, 2014 [Double Goer] Erick Beltrán

p.18 Não-ideia, 2002 [No-Idea] Marta Neves p.19 Dheisheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem, West Bank Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal p.20 O que caminha ao lado, 2014 [Double Goer] Erick Beltrán pp.21-25 Baobab Connection Text by Alessandro Petti, Sandi Hilal, Grupo Contrafilé and others

p.49 Não-ideia, 2002 [No-Idea] Marta Neves p.50 The Map of Utopia, The Map of the City, 2012 Qiu Zhijie p.51 Wonderland, 2013 Halil Altındere

pp.26-27 Turning a Blind Eye, 2014 Bik Van der Pol

pp.52-57 Working with Things That Don’t Exist Text by Benjamin Seroussi, Charles Esche, Galit Eilat, Luiza Proença, Nuria Enguita Mayo, Oren Sagiv and Pablo Lafuente

pp.28-30 SIASAT – São Paulo ruangrupa

p.58 Untitled, 1988 Juan Downey

pp.31-33 Espacio para abortar, 2014 [Space to Abort] Mujeres Creando Text by Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz

pp.59-61 Ônibus Tarifa Zero, 2014 [Fare Free Bus] Graziela Kunsch

pp.34-37 Comboio and Movimento Moinho Vivo

pp.62-63 Voto!, 2012-ongoing [Vote!] Ana Lira pp.63-65 Save Roşia, 2013 Dan Perjovschi

12

pp.65-67 Wonderland, 2013 Halil Altındere Lyrics from Wonderland written by Tahribad-ı İsyan pp.68-69 Violencia, 1973-1977 [Violence] Juan Carlos Romero p.70 Sem título, 2013 [Untitled] Éder Oliveira p.71 Não é sobre sapatos, 2014 [It Is Not About Shoes] Gabriel Mascaro pp.72-73 A última palavra é a penúltima – 2, 2008/2014 [The Last Word Is the Penultimate One – 2] Teatro da Vertigem pp.74-75 Nada é, 2014 [Nothing Is] Yuri Firmeza Text by Ana Maria Maia pp.76-77 Invention, 2014 Mark Lewis pp.78-79 Small World, 2014 Interview with Yochai Avrahami pp.80-89 On Seeking Incuriously Text by Tony Chakar p.90 Dust Bowl in Our Hand, 2013 Prabhakar Pachpute p.91 Breakfast, 2014 Leigh Orpaz Text by Helena Vilalta pp.92-93 Those of Whom, 2014 Notes for Those of Whom by Sheela Gowda

pp.94-95 Céu, 2014 [Heaven] Danica Dakić p.96 Meeting Point, 2012 Bruno Pacheco p.97 Open Phone Booth, 2011 Nilbar Güreş Text by Santiago García Navarro p.98 Resimli Tarih, 1995 [Illustrated History] Gülsün Karamustafa Text by Helena Vilalta p.99 Landversation, 2014 Otobong Nkanga p.100 Kopernik, 2004 [Copernicus] Wilhelm Sasnal p.101 Art Education, 1999 Lia Perjovschi p.102 Video Trans Americas, 1973-1979 Juan Downey p.103 Tayari (Amazon Rain Forest), 1977 Juan Downey p.104 Fuego en Castilla, 1958-1960 [Fire in Castile] Val del Omar p.105 O suplício do bastardo da brancura, 2013 [The Hardship of Bastard of Whiteness] Thiago Martins de Melo pp.106-107 A última aventura, 2011 [The Last Adventure] Romy Pocztaruk Letter from Luísa Kiefer to Romy Pocztaruk

pp.108-109 Ymá Nhandehetama, 2009 [In the Past We Were Many] Armando Queiroz with Almires Martins and Marcelo Rodrigues Text by Almires Martins pp.110-111 MapAzônia Part of Dossiê: Por uma cartografia crítica da Amazônia [Dossier: For a Critical Cartography of the Amazon] pp.112-113 House/studio views, 2014 Vivian Suter p.114 Untitled, 2010 and Untitled (Mine), 2009 Wilhelm Sasnal p.115 Árvore de sangue – Fogo que consume porcos, 2014 [Blood Tree – Fire Devouring Pigs], Thiago Martins de Melo

p.126 A última aventura, 2011 [The Last Adventure] Romy Pocztaruk p.127 Life Coaching, 1999 Lia Perjovschi pp.128-135 Image Captions pp.136-137 Projects’ Credits pp.138-153 Biographies pp.154-159 Credits pp.160-161 Acknowledgments p.166 neoblanc, 2013 Yonamine

pp. 116-117 Cotton White-Gold, 2010 Anna Boghiguian

p.167 The Map of the Park, 2012 Qiu Zhijie

pp.117-119 Archéologie marine, 2014 [Marine Archaeology] El Hadji Sy Excerpt from Black Soul by Jean‑François Brière

pp.168-169 Of Other Worlds That Are in This One, 2014 Tony Chakar

p.120 Cities by the River, 2014 Anna Boghiguian pp.121-122 Handira, 1997 Teresa Lanceta p.123 Junction, 2010 Nilbar Güreş pp.124-125 Muhacir, 2003 [The Settler] Gülsün Karamustafa Text by Helena Vilalta

pp.170-171 Los incontados: un tríptico, 2014 [The Uncounted: A Triptych] Mapa Teatro – Laboratorio de artistas pp.172-174 The Excluded. In a moment of danger, 2014 Text Notes for the film The Excluded by Chto Delat pp.175-179 Errar de Dios, 2014 [Erring from God] Etcétera... and León Ferrari

13

p.180 Letters to the Reader 1864, 1877, 1916, 1923, 2014 Walid Raad p.181 Minimal Secret, 2011 Voluspa Jarpa Text by Santiago García Navarro p.182 Karl Marx, 1992 Lázaro Saavedra

pp.201-211 ‘All It Takes Is for Educators to Question Themselves’ Text by Graziela Kunsch, Lilian L’Abbate Kelian and invited educators p.213 Poster for the 31st Bienal Prabhakar Pachpute pp. 214-225 Architecture

p.183 Nogal (serie Perímetros), 2012 [Walnut (Perimeters Series)] Johanna Calle

pp.226-227 Balayer – A Map of Sweeping, 2014 Imogen Stidworthy Text by Helena Vilalta

p.184 Contables (serie Imponderables), 2009 [Countables (Imponderables Series)] Johanna Calle

pp.228-229 “… - OHPERA – MUET - ...” 2014 [“… - MUTE - OHPERA - …”] Alejandra Riera with UEINZZ Text by Alejandra Riera

pp.184-185 Apelo, 2014 [Plea] Text Speech for the film Apelo by Clara Ianni and Débora Maria da Silva

pp.230-233

pp.186-187 Justice for Aliens, 2012 Agnieszka Piksa

pp.234-238 Loomshuttles, Warpaths, 2009-ongoing Ines Doujak and John Barker

pp.188-190 The Incidental Insurgents, 2012 Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme

Línea de vida | Museo Travesti del Perú, 2009-2013 [Life’s Timeline | Transvestite Museum of Peru] Giuseppe Campuzano

p.239 Untitled (Perú-Bolivia Journey), 1976 Juan Downey

pp.191-194 The Revolution Must Be a School of Unfettered Thought, 2014 Jakob Jakobsen and María Berríos

pp.240-241 Overhead, 2010 and The Grapes, 2010 Nilbar Güreş

pp.195-200 La Escuela Moderna [The Modern School], 2014 Files by Archivo F.X./Pedro G. Romero

pp.242-245 Dios es marica, 1973-2002 [God is Queer] Nahum Zenil / Ocaña / Sergio Zevallos / Yeguas del Apocalipsis Text by Miguel A. López pp.246-247 Counting the Stars, 2014 Text by Nurit Sharett and Carlos Gutierrez

14

pp.248-249 Sergio e Simone, 2007-2014 [Sergio and Simone] Virginia de Medeiros pp.250-265 Towards an Art of Instauring Modes of Existence That ‘Do not Exist’ Text by Peter Pál Pelbart p.255 Pages from Les Détours de l’agir: Ou, Le Moindre Geste, Fernand Deligny p.261 Spear, 1963-1965 Edward Krasiński pp.266-267 Installation at Edward Krasiński’s Studio, 2003 Edward Krasiński pp.268-269 Agoramaquia (el caso exacto de la estatua), 2014 [Agoramaquia (The Exact Case of the Statue)] Asier Mendizabal pp.270-271 In the Land of the Giants, 2013 Jo Baer pp.272-273 Aguaespejo granadino, 1953-1955 [Water-Mirror of Granada] Text Dialogues by Val del Omar pp.274-275 Fuego en Castilla, 1958-1960 [Fire in Castile] Text Programme by Val del Omar pp.276-279 Caderno de referência, 1980s [Reference Notebook] Hudinilson Jr. Text Xerox Action by Mario Ramiro pp.280-281 Casa de caboclo, 2014 [House of Caboclo] Arthur Scovino

pp.282-285 Letra morta, 2014 [Dead Letter] Excerpt of the film script by Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa p.286 Vila Maria, 2014 Danica Dakić

p.314 Back to the Farm II, 2013 Prabhakar Pachpute p.315 Del Tercer Mundo Exhibition, Havana, 1968 [From the Third World]

pp.287-288 A família do Capitão Gervásio, 2013 [Captain Gervásio’s Family] Kasper Akhøj and Tamar Guimarães

pp.316-317 Index of Participants

pp.289-292 Terrible Deed Text by Michael Kessus Gedalyovich

p.325-Inside back cover The Amazon Isn’t Mine! Text by Armando Queiroz

pp.318-320 Index of Projects at the 31st Bienal

pp.293-295 Nosso Lar, Brasília, 2014 Jonas Staal pp.296-297 Nova Jerusalém [New Jerusalem] Text by Benjamin Seroussi and Eyal Danon pp.298-301 Inferno, 2013 [Hell] Yael Bartana pp.301-303 Capitol, 2009; Columbus, 2014; Untitled, 2013 Wilhelm Sasnal pp.304-309 Mind and Sense: On the Ambivalence in Noraic Husdrapa and Mind Singing. Text by Asger Jorn pp.310-311 neoblanc, 2013 Yonamine p.312 Knowledge, 1999 Lia Perjovschi p.313 Landversation, 2014 Otobong Nkanga 15

Bruno Pacheco, Meeting Point, 2011

Juan Downey, Untitled, 1975

Marta Neves, N達o-ideia, 2002 [No-Idea]

Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal, Dheisheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem, West Bank, 2008

Erick Beltrรกn, O que caminha ao lado, 2014 [Double Goer]

20

Baobab Connection Text for the project Mujawara by Alessando Petti, Grupo Contrafilé, Sandi Hilal and others

From March 2014, the duo of Architects Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti and the Grupo Contrafilé held meetings in São Paulo, at the Centro Cultural Tainã, in Campinas, and at the Terra Vista settlement in southern Bahia, where they were joined by Milson Oniletó (a member of the Rede Mocambos), TC Silva and Joelson Ferreira de Oliveira, who are leading activists in the struggle for land. Through the educational platform Campus in Camps, Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal work with communities of Palestinian refugees to produce new forms of representation of the camps and of themselves – overcoming the static, traditional images of victimisation, passivity and poverty by promoting new political and spatial configurations. Contrafilé has been working with land issues by building ‘backyards’ within the A Rebelião das crianças [Children’s Uprising] project. Allowing the body to work the land, in the land and through the land, Contrafilé creates a collective space for imagining and playing, which is, above all things, the access to a spatiality of freedom. The Centro Cultural Tainã is a political centre for educational and cultural production. Created by TC Silva, it is the milestone of the Rede Mocambos, which connects quilombola communities (self-sufficient communities formed by activists affirming their African-Brazilian heritage) through the internet and the ritualistic planting of baobabs. Its horizontal and non-linear links subvert the rooted notion of an ancestral past, which no longer acts on the present, so that these other temporalities can emerge and awaken critical thought. Founded in 1995 in Arataca by workers related to the Movimento dos Sem-Terra [Landless Workers’ Movement] (mst), Terra Vista defines itself simultaneously as settlement and quilombo. A regional leader in organic farming, it has developed a comprehensive educational programme, from middle school up to professional education in agroecology.

Sunrise Terra Vista settlement, Arataca, 5 May 2014

Contrafilé […] After having a private talk with Joelson, TC brought us some new information: there’s a place where Joelson plans to build a temple for ‘chiefs’ meetings. We woke up at 5.30 a.m. and went to his house, where we were already expected. We went for a walk through the settlement, taking many pauses, in which Master Joelson, as he’s known there, gave us real lectures. Leaning always on a tree, he evoked the image of the ‘original school’.

Every young baobab we found was revered by TC. The symbolic and dynamic role of these trees within the movement became very clear. According to him: ‘Soon, every point in the network will have its baobab, which will become the “password” of this movement.’ When the walk ended, Joelson took us where the temple will be built: it’s the place where he watches the sunrise and makes his connections; he also intends to plant a baobab there. ‘It will be a temple for celebrating water, knowledge and the sun,’ he says, and adds: ‘always circular; the circle is the shape that guides us.’

We cultivate together Sandi Hilal: Does the word ‘quilombo’ identify a territorial term, like the word ‘camp’? What’s its source?

TC: Quilombo refers to the territory, and mocambos are the villages or families in the connected area within a common territory. All farming, feasts and childbirths are collective. The most important values of African heritage are nature, land and integration. 21

Sandi Hilal: You’re saying something like: ‘we cultivate together’, but if you have a community that eats, dances and plants together, how does it relate to other communities? Does the concept of quilombo imply a network? Sandi Hilal: One of the things Alessandro and I are aiming at is the Palestinian refuTC: It is very important to think in a global gee camp. These camps are neither private sense, in an exchange of struggles – a nor public property. They’re a community of people standing together fighting for ‘Baobafricanisation of the Americas’. And their right to return back home. Maybe new technologies are important for this. the real conflict arises from the question of how these communities can stay together Alessandro Petti: In 1948, when Israel was established, the beyond all this state construction.

first thing they did was to flatten all this collective land and put it in one single category of public land. In a way, this was a form of expropriation. We always think that public land is good for all. But we don’t realise that this is only good for the coloniser. Let me give an example: there were several categories of this collective land, one of them called Al Masha, which referred to ‘people together’. Everyone knew that it didn’t belong to you or me, it was a common land.

Alessandro Petti: The question for us now is, what is the Al Masha today? What is, for you, the quilombo today? We think Al Masha today is in the camps, because for sixty-five years, even though refugees have been living in very difficult circumstances, there is a total autonomy to how people organise themselves. It is the most political space you can imagine. I understand the desire to go back to memories and roots, but it was the colonial powers that invented the notions of the native and the authentic. This is a way of managing that recognises a subject, but disallows him or her from having influence or being contemporary.

Sandi Hilal: At the beginning of the seeding season, the farmers will divide and sort the land so each one has his place of land for seeding. It was important to support each other, it was a form of being together. And you have to seed. If you are not cultivating you cannot be there. The plot of land you are assigned is not fixed, especially so you don’t feel you own the land.

Alessandro Petti, Sandi Hilal and Grupo Contrafilé, Mujawara, 2014

Contrafilé: In the case of Brazil, the connection with Africa can definitely establish a different way of thinking today. It’s not necessarily a paralysing return, it can be more of a spiral than a linear link.

Sandi Hilal: When you look at a quilombo, what is very interesting is the consciousness of asking for collectivity. In camps, even when life is very collective in action, the request is to return to private property.

After the end of a certain world

Contrafilé: The refugee camps, the quilombos, the backyards, reconnect with an idea of existence on the land, that, when it gains visibility, is able to break away from hegemonic thought-forms. Just as the Zapatistas, who, according to Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, are the evidence of what can exist ‘after the end of a certain world’ the quilombolas and the refugees allow historically prohibited relations and connections to take place.

22

Alessandro Petti: That’s because by the simple fact that they exist they create a problem for those in power. If there are refugees it means that people have been expelled; if they return, Israel as it is today cannot exist. If one accepts this way of thinking one understands that this is not just about resisting, it’s an existential problem. This implies that, when you look at the situation through the lens of these existences, the only possibility is to dismantle the state as it is today. Sandi Hilal: Is this also the case with the quilombos? Is it a political battle for normalisation or decolonisation? One of the lessons I learned from Paulo Freire is that the only one that can liberate the coloniser is the colonised.

TC Silva: After all, who is the victim of what? We’re not simply resisting, we’re making proposals. Contrafilé: From the moment when the question is about existing and not integrating, what kind of existence is that?

Contrafilé: When we built the backyard in São Bernardo in 2013, we heard from a young man that by digging holes, planting trees, building things and touching the earth he had connected with a knowledge he did not know that possessed until then, because city life had never allowed him to access that, as if it had been invisible. He started to understand his black and indigenous heritage, he reconnected with his grandmother, his great-grandmother, as well as the aunt who had a candomblé temple, but where his mother, a Protestant, never let him go.

And the baobab comes in TC Silva: In school, everything I was told about my people was that we were slaves. As a young boy, I believed that black people are born already chained in the mother’s womb, not that they had suffered violence and been enslaved. The Africans who came here were colonised into getting used to that idea. And so were those who colonised, in order to believe that enslaving, denying and killing the culture of another was a good thing. Colonisation is a serious issue, it denies important human experiences. That’s where the baobab comes in. Why didn’t societies try to see what the world would look like, guided by these ancestral rites?

Fernand Deligny, drawings

TC Silva: I want to exist by myself, not according to the way someone else wants me to exist, or not to exist. When we’re talking about what oppresses us, we’re not accepting the position of victim, we’re looking for decolonised forms of thinking.

TC Silva (singing): ‘I can find myself anywhere in the world, if I carry my parents’ house within me, I’ll be alright.’ I am the territory, if I have the reference of the territory. If I don’t have this, then I don’t have anything. Nothing’s more than you, inside you there’s only you, and inside you nothing belongs to you.

Contrafilé: It seems that the body, when it touches the land, realises immediately that the land isn’t the property of anyone, that it belongs to all – it’s the incontestable proof of a common dimension. Joelson F. de Oliveira: When you look at nature, you see that singularities and collectivities get along TC Silva: (singing): ‘Come, living is easy as very well, they don’t fight. In the forest, the strong, flying. Flying beyond the reaches of light. the weak and the newborn live together. And all of a In our dark inner depths.’ We can all make a sudden, the strong have to die so the small can live. So too is the river. The spring flows into a stream, difference if we can realise who we are. We which flows into a river, which then flows into have to grow strong as people. Otherwise the ocean.

we’ll always be half-people.

23

Milson Oniletó: This will be the symbol of this century’s change. Because we were ‘europeanly’ taught to be a dependent part of the other. ‘You are my part and together we’re complete.’ No, African societies teach that we have to be whole. This doesn’t mean being selfish. I am God, I grow with myself; then I’ll merge with you who are also God and are whole; then with you and with you, and we grow in a circle.

TC Silva: The territory is your place, where you plant, where you eat, where you work the land. It’s something charged with meaning, involving ancestral values, from which we have been disconnected. We spend our whole lives without ever touching the land, but nothing exists without it. Therefore, I don’t have to carry anyone’s territory. The territory is ours, therefore we can move inside it to connect with other territories and realities. (Showing the baobab fruit.) This is the baobab’s house. It’s like a womb, a temporary shelter. All that comes out of it will expand.

Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal, Dheisheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem, West Bank, 1955 /2012

Milson Oniletó:

I am because we are.

Having a fixed identity or the right to transform oneself?

Alessandro Petti: How can the quilombo stop being an identity project and become one where all the people can join in? The conflict would be between having a fixed identity and having the right to transform oneself. This is also valid for Palestine. You first have to have a Palestinian state identity. But then it’s a national state like any other. This is where camps and possibly quilombos could be different; they could be places where people are not fixed in one identity.

Sandi Hilal: After being expelled in 1948, the refugees lived in tents for four years. When they eventually built four walls, they wondered whether or not to build a roof. They feared that if they built the roof, this would prevent them from going home. Once I heard some women in the camp ask one of the leaders: ‘When will we return home?’ He said: ‘We don’t have enough transportation to take you home’. This is a core question for them: how can we take our present life back to our history? That is the life of exile.

24

TC Silva: Since the beginning the colonising process has tried to deconstruct the quilombola and indigenous identities. Remembering doesn’t mean being stuck in the past. It’s important not to forget one’s own history, because if you do you’ll be submissive to churches, political parties, the media...

Campus in Camps, Campus in Quilombos Alessandro Petti: In order to talk about these places today and not just about the past, we felt it was very necessary to build a university inside it, and we called it Campus in Camps. This has to do with what you have been doing at Rede Mocambos, by connecting quilombos.

Sandi Hilal: The principle of Campus in Camps is not simply to move the structure of a university as it is inside the camp, but to actually think of the camp as a source of knowledge. This is actually how a university should be: a place to give names to things, to problematise our own lives. Joelson F. de Oliveira: Our greatest dream is to build a school that awards graduate diplomas or a Masters degree. The idea is, together with neighbouring communities, that the child starts from kindergarten and has a full education here. If we can get communities to work together, we’ll combine knowledge.

Alessandro Petti: I think we definitely have a good starting point, talking about the refugees, quilombos and education. But we have to secure some distance, or we may risk just describing the thing and not adding anything or even problematising anything. We must bring this discussion back to the idea of metropolis, to the Bienal itself. This is also the world that we inhabit.

What does it mean to be contemporary? Contrafilé: You don’t have to be in a city in order to be contemporary. Conversely, urbanity does not necessarily mean a city. It means that many scales operate at the same time. If, for instance, you are in a refugee camp, there are people connecting through many different layers and levels on local and global scales, they are creating institutions and knowledge.

Grupo Contrafilé, preparation for baobab planting ritual, 2010

Alessandro Petti: Maybe the question is: what can we do together now? This has political power. Just being fascinated by the other is not enough and it’s not worth just showing things in the museum.

Contrafilé: Exactly. If we define that we are working with these realities not only in theory we need to step forward and truly do away with representation. For this, we believe in another kind of image, which is a dense-image, a land-image. That is, we use land-support as the means for the materialisation of an image that has realised itself inside us with urgency. Then, a body acting on urbanity through this image wouldn’t be a machine, and here is where its power lies. Because it’s a body that carries an image at the same time as it is carried by it: it is a born image.

Joelson F. de Oliveira: So thinking about this, how will liberty be built? The work towards liberty is harder than that towards being a slave. We have to produce good experiences for the eyes of the world. But it’s necessary that they be concrete. Then they will flourish by themselves. During one of the occupation processes, we marched from Feira de Santana to Salvador. When we finally got there, we went to a place where there was only concrete and on the buses there was only space for the women and children. Then it started to rain and only stopped the following morning. We, the men, stood for twelve hours in the rain. We asked ourselves ‘Why are we doing this?’ Now we know why: to protect Mother Earth to have a plot of land, to have another perspective.

25

Turning a Blind Eye Admiral Nelson was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy, famous for his leadership, sense of strategy and unconventional tactics, which resulted in a number of decisive naval victories. He was wounded several times in combat, losing one arm and the sight in one eye. During the Battle of Copenhagen (1801) his cautious overall commander Parker sent a signal to Nelson’s forces giving him discretion to withdraw. At that time, naval orders were transmitted via a system of signal flags. When the more aggressive Nelson was given attention to this signal, he lifted his telescope up to his blind eye and said ‘I really do not see the signal!’, and his forces continued the attack, resulting – after a lot of destruction – in a victory for the British fleet. We may all be blind to what is in front of us; we might also be willfully blind. Turning a Blind Eye (2014), a programme of public workshops, events, lectures and walks by Bik Van der Pol, explores different notions of the ‘unseen’ (the non-visible and the non-existent), and the ways in which we look at things or choose what we look at. The programme seeks to investigate the idea of ‘publicness’, as well as to generate a public for its own activities. A live, large scoreboard animated live follows the developments of the projects and invites the publics to become participants. We understand that artistic practice is a form of learning, and a space of experience and encounter. Art can be a strategy for emancipation and a potential response to public issues. The recent occupations of public squares worldwide, or the increasing commercial exploitation of private information, demonstrate the urgency of public space as a site of conflict over rights, information, relations and objects. Debates over forms of common property such as knowledge and culture show that public space is to be understood in the broadest possible terms – as that which holds the fabric of experience-as-community together. Yet it is threatened by exclusions, privileged access and disinformation to the point that it becomes invisible. Public property needs to be re-articulated time and again, and is just as precarious as the natural environment, threatened by a predatory economy.

26

Turning a Blind Eye investigates recent events in Brazil and worldwide, departing from tensions around the exploitation of urban and natural space. The programme has been created with the participation of the general public, students of the School of Missing Studies, universities and organisations in São Paulo. The 31st Bienal acts as the site for the project’s creation and research, implementing the educational model of ‘the school’ as a form of mental theatre that may create new horizons of action, production and reflection. Bik Van der Pol

Bik Van der Pol, [accumulate, collect, show], 2011

27

HISTORY, ARCHIVES

BOUNDARIES, BORDERS AND ACCESS

Abstract Possible is a research project exploring notions of abstraction, taking contemporary art as its starting point.

ABSTRACTION Islandkeeper: Maria Lind

nagele

Communi(ci)ty’, the societal, cultural and moral issues of a boletsi radical liberation of planning.

FREELAND Islandkeeper: Jeroen Zuidgeest

Public rhetorical strategies and the ways they give a shape to (and restricts) public space.

BARBARIZING PUBLIC SPEECH Islandkeeper: Maria Boletsi

URBAN SPACES AND SPACE OF NATURE AS SITES OF CONFLICT

Think Tank Aesthetics reflects on art and its relations to current debates about the political and the social against the backdrop of neoliberalism.

THINK TANK AESTHETICS Islandkeeper: Pamela M. Lee

Collective activities contributing to the crossdisciplinary exchange between several nodes of knowledge production: network and participatory technologies; sensorial media and public space; environmental remediation design and spatial organization; and alternative planning design integration

IN PROGRESS Islandkeepers: Gediminas and Nomeda Urbonas

ABSTRACTION AND FRAGMENTATION

Oct 2013

Comparison of different urban ideologies from different perspectives, analyzing the effect of current (global) developments in (former) new towns, observing new towns of today and speculating on the future.

BLUEPRINT NL (NAGELE) Islandkeepers: Bik van der Pol

This island is about living in a world in which the doing is separated from the deed, in which this separation is extended in an increasing numbers of spheres of life, in which the revolt about this separation becomes ubiquitous. In collaboration with Casco Projects, Utrecht

COMMONING TIMES Islandkeepers: Rene Gabri and Ayreen Anastas

What does it mean to engage in ‘the missing’ and to acknowledge the unknown?

A MISSING VOCABULARY writing & discussion sessions Islandkeeper: Moosje Goosen

Bik Van der Pol, School of Missing Studies, 2013 - ongoing

THE COMMONS, PRIVATIZATION AND ACCESS ECOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGY

Oct 2014

Interactions between forests and atmosphere, mapping and economics, mutual learning as forms of exchange, lost knowledge and megaprojects in the Amazone, displacement, participatory architecture, lost sights, lost sites, walking tours, invisible rivers concrete jungle, unseen and turned away, participatory forms of staging.

Turning a blind eye [or: ignoring an undesirable information] or I really do not see the signal!

URBAN SPATIAL POLITICS

Scenarios for an intervention as a response to tenderness in the daily life and a challenge to that what is near.

DIVINE INTERVENTION Islandkeeper: Samira BenLaloua

The main question that runs through the thesis is what does it mean to situate one's work "in institution," while at the same time rubbing against official (and institutionalised) ways of knowing?

IT'S TIME MAN. IT FEELS IMMINENT: POLITICS AT THE MOMENT OF EXPOSITION Islandkeeper: Sarah Pierce

LANGUAGE AND RHETORIC

“The borders of new sociopolitical entities (...) are no longer entirely situated at the outer limit of territories; they are dispersed a little everywhere, wherever the movement of information, people, and things is happening and is controlled” (Etienne Balibar).

THE BORDERS ARE NO LONGER AT THE BORDER Islandkeeper: Ernst van den Hemel

Exploring the contemporary landscape of Palestine in particular urban environments.

FRAGMENTED CARTOGRAPHIES Islandkeeepr: Tina Sherwell

1. The elements On context – the mobility experienced by people with different social, economic and cultural backgrounds has created diverse behaviours and communities. There are cartographies of hybrid behaviours and social realms that influence one another. On histor y – write… On the social – deploy well-tested formulas and strategies in using the urban space as locus for social intervention, while exploring new means and methods.

ruangrupa, RURU.ZIP, Decompression #10, National Gallery of Indonesia, Jakarta, 2010

SIASAT – São Paulo Text for the project RURU by ruangrupa Our latest payroll statistics show that ruangrupa regularly involves more than twenty people, and works with about ten project-based additional people. Being an organisation of such small scale, having survived for nearly fifteen years cannot be considered as a small feat. In addition, being an organisation born in a post-crisis context – at the time when Indonesia was struggling with the lingering effects of the 1998 Asian economic depression – crisis has always been an omnipresent factor that forever haunts the consciousness of ruangrupa. In 2011, a little shortly after we celebrated our tenth anniversary, we composed an always-in-beta document entitled SIASAT: a short tactical guide for artist-run initiatives, an ‘dense’ eighty-page binder, a how-to manifesto-like survival kit. SIASAT – São Paulo can be considered as a prototype, born out of SIASAT. What is forced relocation (whether following touristic, economic or the basic survival impetus) but a form of crisis? What follows are some statements taken from the document, which served as our starting points in formulating SIASAT – São Paulo.

28

On politics – discover some channels to fill in the gaps. Speak from our own position to complete or otherwise enrich the structure by offering more spaces for exploration, without boring attempts to directly oppose whatever establishment there is – while at the same time avoiding co-option. On culture – engage with the widest possible landscape of arts and cultural production and involve the public within the arena of production. On interdisciplinarity – set up a group of people who produce spontaneous and sporadic ideas. On collaboration – it is about giving everyone a remote control. On process – a direct opposition, an antithesis, a resistance, or a direct reaction against the mainstream. Multiply-Integrate-Viral On platform – the space should also be imagined as a continuous effort towards a better dissemination. On working style – love and other demons… jokes and play… music and alcohol and cigarettes. Distraction is bliss.

2. The empire of love

3. The shelter

4. The centre of the storm

Grow and work as a platform (foundation/vessel) that can continue to hold ideas, passion, excitement, imagination and dreams, and, of course, friendship.

Participants should be able to disperse or even hide easily. In this sense, warehouses and government buildings are not an option.

Things to consider as survival kit: Laptop (as long as there is electricity) Sleeping bag Medical kit Military survival guidebook

Build a structure that has the adaptability/flexibility to change based on the realities of the society around it. Build a structure that can acknowledge the speed of change in society.

Social/cultural context and class – the question of using domestic, commercial, abandoned space or even of becoming spaceless should be raised. Budget – budget-less is also possible.

Do not trust any existing structure. Invent your own.

On how to build an architectural character:

Do not pay too much attention to the structure. Let the content define its structure.

Facilitate personal and collective ideas in the auto-creation of spaces.

It always good to be disorganise. (sic)

On models and programmes:

On networking – make friends not art. On local/international partnershit (sic) – build a decentralised network, based on collaboration and horizontal partnerships. Silaturahmi. On conflict – it’s overrated.

On how to choose a space:

Large – meeting/working/archive and library; exhibition/screening/ party; toilet/kitchen; sleeping area/ artist residency/shops; parking space; storage approximately 100 sqm; above-average for large property house/large size apartment/ large warehouse, etc.

On sustainability – ongoing negotiation.

Things to consider as sur vival tricks: Reduce programmes Reduce expenditure Friends or family loan Pawnshop Inheritance (maybe) Charity Last but not least: busking, scrounging and begging for money Internal constraints/domain disaster: a. Conflict management b. No membership c. Loss of space d. No ideas/motivation, boredom e. No funding/money f. Social conflict On dealing with points (a) (b) (d) – DO NOT try to be wise. One rule to settle all: DO NOT BE A SMARTASS. DO NOT TRY to reach any conclusion. On dealing with points (c) (e) (f ) – DO NOT TRY to place yourself as negotiator. Negotiation is not an important matter. DO NOT PURSUE justification. Injustices arise only after justice is defeated.

ruangrupa, RURU.NET Decompression #10, National Gallery of Indonesia, Jakarta, 2010 29

5. The anatomy of numbers

6. An affair to remember

Money is not everything. Time is…

On space and public – intervene and cooperate by entering spaces of public consumption, such as malls, shops, neighbourhoods and streets. Operate through daily and social events. Let people participate. Let them become a part of everyday life, where the public is free. Develop new approaches to see tensions in and functions of the public, domestic and private spaces. Negotiation and interaction with the surroundings are important aspects which influence artistic practice and other activities of the organisation.

On local resource – it is NOT advisable to choose donors that intervene within the programme platforms. On how to self-raise income: donations and fundraising – if you think setting up a business unit is a good idea, make sure that it does not corrupt your artistic integrity. This decision would only be strategic if it was integrated with your programmes or activities. On shops/creative works/ projects/micro-transaction, etc. – make a small shop filled with various artworks from the young artists that frequently collaborate with you. Set up a second-hand market or cooperation with small-/street-level businesses in order to generate and support the micro-economic system. On commercial/selling/buying – only sell your works to your ‘friends’. On how to work without a budget – find people to work with who are young, or who are looking for experience, and are willing to work pro bono publico. Create a programme that allows you to work off-budget. Money is not necessarily the only form of support. On how to find and work with sponsors – creating a proposal is unlike writing a poetry anthology: avoid using sentences that are too flowery and rhetorical. A good proposal, most of the time, comes from a good project. On how to work with government support – be careful with corruption and manipulation: they are the experts. Trust no one.

30

On public affairs – the space becomes a public domain: dispossession of space, open to the public, meeting point, noninstitutional. On how to make your space public: Put the ‘WELCOME’ rug at the front door Don’t lock your door Open the space up to support your friends, then to anyone else Open it 24/7 Treat your space as a meeting point Serve the public with a friendly approach.

ruangrupa, RRREC Fest, Jakarta, 2010 - ongoing

On how to deal with the neighbours – always buy your daily needs in the surrounding area. On how to create basic public involvement – make a programme that relates to your surroundings. On how to communicate with the public – publish your character. If you don’t need to, you don’t have to. ruangrupa, Toko Keperluan, Anggun Priambodo’s solo exhibition, RURU Gallery, Jakarta, 2010

Mujeres Creando, Graffiti, undated

Espacio para abortar (2014) [Space to Abort] starts with an urban intervention, a public and participative procession-performance against the dictatorship of patriarchy that is exercised over women’s bodies. A giant mobile uterus is paraded and then tem-porarily placed in the Bienal Pavilion. Once inside the Bienal, the idea for it is to open a space for debate and dialogue. In other words, the project creates a platform for discussing the meaning of abortion, the colonisation of the female body and what free choice, the right to decide and freedom of conscience actually mean in contemporary democracies – especially those in South American countries where abortion is illegal and penalised. Founded in La Paz in 1992, Mujeres Creando is an internationalist movement of working women (prostitutes, poets, journalists, market sellers, domestic workers, artists, dressmakers, teachers, etc.) fighting against sexism and institutionalised patriarchy in Bolivia and the rest of the world. With this goal, the members of Mujeres Creando operate like guerrilla fighters, opening spaces of visibility and uncovering others with their bodies, in the street, in the mass media, and in international contemporary art spaces, inserting iconic slogans in its ideological circuits, for instance: ‘You can’t decolonise without depatriarchising!’, or ‘There is nothing more similar to a right-wing sexist than a left-wing sexist!’

Mujeres Creando, Útero ilegal, 2014 [Illegal Uterus] 31

Mujeres Creando, Graffiti, undated

Yeguas del Apocalipsis, Casa particular, 1989 [Private Home]

Mujeres Creando, Ăštero ilegal, 2014 [Illegal Uterus] 32

33

IN THE CITY OF SÃO PAULO, THERE IS A PLACE WHERE THE COURSE OF THE TRAIN LINES BISECTS, ONLY TO COME TOGETHER AGAIN FURTHER AHEAD. THIS UNION-SEPARATION-UNION CREATES A WALLED SPACE SHAPED LIKE AN EYE, AND INSIDE THIS EYE STANDS THE LAST FAVELA IN DOWNTOWN SÃO PAULO, FAVELA DO MOINHO. FOR ABOUT THIRTY YEARS, IT HAS OCCUPIED THE RUINS OF THE OLD MOINHO MATARAZZO (‘MATARAZZO MILL’) AND WAS ONCE HOME TO OVER 1,200 FAMILIES. A DIRECT TARGET OF REAL-ESTATE SPECULATION AND ‘GENTRIFICATION’ PROJECTS, THE COMMUNITY OF MOINHO CONTINUES TO RESIST IN ONE OF THE MOST HIGHLY VALUED AREAS OF THE CITY, THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF CAMPOS ELÍSEOS.

THE HEART IS BELOW AND TO THE LEFT.

IN DECEMBER 2011, THE FAVELA DO MOINHO BECAME KNOWN NATIONALLY AND INTERNATIONALLY BECAUSE OF A LARGE FIRE THAT AFFECTED AROUND FIVE HUNDRED FAMILIES AND CUT THE OCCUPIED AREA IN HALF. THIS FIRE OCCURRED DURING THE SAME YEAR IN WHICH SEVERAL OTHER FAVELAS IN SÃO PAULO – ALL LOCATED IN AREAS OF GREAT INTEREST TO THE REAL ESTATE INDUSTRY – WERE ALSO STRUCK BY FIRES.

ON 31 DECEMBER 2011, THE CITY HALL GOT A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION TAKING POSSESSION OF PART OF THE LAND, ALLEGING THAT THE BUILDING HAD TO BE DEMOLISHED BECAUSE IT WAS IN DANGER OF COLLAPSING. THE AREA WAS THEN SECTIONED OFF BY WOOD SCAFFOLDING THAT CUT THE FAVELA FROM END TO END AND MADE IT HARD FOR RESIDENTS TO RETURN TO THEIR PLOT. NOT ONLY WAS THE BUILDING NOT ON THE VERGE OF COLLAPSE, BUT THE SIX HUNDRED KILOGRAMMES OF DYNAMITE THEY USED TO TRY TO DEMOLISH THE HUNDRED-YEAR-OLD STRUCTURE DID NOT KNOCK IT DOWN. BUT STILL, CITY HALL DECIDED TO CONTINUE THE DEMOLITION MANUALLY. THE SCAFFOLDING WAS REPLACED BY A CONCRETE WALL THAT WAS EIGHT METRES TALL TO DEFINITIVELY PREVENT RESIDENTS FROM REBUILDING THEIR HOMES AND, ACCORDING TO A REPORT FROM THE FIRE DEPARTMENT ITSELF, LEFT THE COMMUNITY WITHOUT AN ESCAPE ROUTE IN CASE OF ANOTHER FIRE. AFTER SEVERAL ATTEMPTS TO ESTABLISH A DIALOGUE WITH THE MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION, ON 4 AUGUST WE DECIDED TO TAKE THE WALL DOWN WITH OUR OWN HANDS AND CLEAR AN ESCAPE ROUTE OURSELVES. THIS ACT BECAME KNOWN AS THE ‘FALL OF THE WALL OF SHAME.’

‘THE FIRE STARTED AT THE SAME TIME IN DIFFERENT PLACES AND IN LESS THAN TEN MINUTES IT HAD SPREAD. THE BUILDING WAS MADE OF BRICK. THERE’S NO WAY IT WOULD HAVE CAUGHT FIRE THAT WAY UNLESS THERE HAD BEEN SOME FLAMMABLE LIQUID THERE. THE FIRE DEPARTMENT TOOK OVER AN HOUR TO GET THERE AND WHEN THEY DID THEY HAD NO WATER. ALL OF A SUDDEN, WE SEE THE MAYOR ON TELEVISION SAYING THAT IT HAD BEEN AN ACCIDENT CAUSED BY A DRUG ADDICT. WE SAW AT LEAST THIRTY CHARRED BODIES WRAPPED IN PLASTIC BAGS BEING CARRIED OUT THE BACK OF THE FAVELA BY POLICE. LOTS OF THEM WERE CHILDREN AND VARIOUS RESIDENTS TALKED ABOUT A FAMILY THAT DIED HUGGING ONE ANOTHER. I SAW THE FIRE CHIEF BURST INTO TEARS, EVEN THEY COULDN’T TAKE SEEING WHAT WAS GOING ON. THIS FIRE WAS NO ACCIDENT, IT WAS A CRIME, MOST LIKELY COMMITTED BY PEOPLE IN POWER WHO HAVE INTERESTS IN THAT AREA. ON TOP OF ALL THESE INDICATIONS THAT THE FIRE WAS PLANNED, WHAT HAPPENED NEXT ONLY SERVES TO SUPPORT THIS THEORY.’

CASA PÚBLICA (‘PUBLIC HOUSE’) IS AN URBAN INTERVENTION RESULTING FROM AN ARTISTIC RESIDENCY AND RESEARCH IN FAVELA DO MOINHO, WHICH COMMENCED IN SEPTEMBER 2012. SINCE THEN, WE HAVE BEEN ABLE TO EXPLORE THE AREA’S ISSUES AND PROBLEMS MORE DEEPLY, AS WELL AS GET TO KNOW LOCAL FIGURES. AFTER A LONG PERIOD OF DAILY COHABITATION AND OBSERVATION OF THE DYNAMICS OF USERSHIP IN THE SPACE, WE BEGAN THE CONSTRUCTION OF CASA PÚBLICA, BUILT IN PARTNERSHIP WITH RUBBISH COLLECTORS AND RESIDENTS, UTILISING LOCAL TECHNOLOGY, THE RESOURCES AVAILABLE IN THE COMMUNITY AND MATERIALS DISCARDED THROUGHOUT THE CITY. SINCE JUNE 2013, THE SPACE HAS SERVED AS AN IMPORTANT SPACE FOR UNITING, ARTICULATING AND FACILITATING VARIOUS CULTURAL AND POLITICAL AGENTS INSIDE AND OUTSIDE THE COMMUNITY.

COMBOIO (‘CONVOY’) IS AN INDEPENDENT AND AUTONOMOUS PROJECT OF RESEARCH AND URBAN INTERVENTION, WHICH HAS BEEN OPERATING IN ‘INFORMAL’ SPACES IN CENTRAL SÃO PAULO SINCE 2010.

‘VERMELHÃO’ (‘REAL RED’) IS THE NAME GIVEN BY INHABITANTS TO A SPACE LOCATED NEXT TO THE OVERPASS USED MAINLY BY THE CHILDREN OF MOINHO AS A LEISURE AREA. AFTER THE LAST BIG FIRE THAT RIPPED THROUGH THE FAVELA IN SEPTEMBER 2012, THIS SPACE BECAME A DUMPING GROUND FOR GARBAGE, SCRAP METAL AND ASHES. WITH THE RECONSTRUCTION OF NEIGHBOURING HOUSES, THE SURROUNDINGS WERE ONCE AGAIN OCCUPIED. THUS, THE DESIRE TO REBUILD AND RECLAIM THIS IMPORTANT PUBLIC SPACE EMERGED. PARQUE VERMELHÃO (‘REAL RED PARK’) IS A DIRECT EXTENSION AND DEPLOYMENT OF CASA PÚBLICA’S EFFORTS.

EVEN WITH THE LACK OF SPACE BEING A SERIOUS PROBLEM AND WITH HOUSES BUILT ON TOP OF ONE ANOTHER, THERE IS STILL ONE SPACE WITH THAT HAS BEEN MAINTAINED AND PRESERVED BY THE COMMUNITY FOR THE PAST THIRTY YEARS: THE SOCCER FIELD. FOR THE 31ST BIENAL DE SÃO PAULO, WE PROPOSED AN ACTIVATION OF THIS SPACE THROUGH OPEN MEETINGS AND EDUCATIONAL WORKSHOPS.

Agência Popular de Cultura Solano Trindade The agency’s mission is to foment popular culture by making artistic production viable in the outer city limits of São Paulo, building strategies for self-funding and economic sustainability. Through this initiative, we seek to understand more about the relationships of production, consumption and commercialisation of services, products and cultural knowledge, and thus contribute to the development of the local creative economy. In the following pages there are details of a few of the cultural groups and activities we work with.

Sarau Verso em Versos One of the cultural manifestations that take place every third Friday of the month at Espaço Comunidade, Sarau Verso em Versos is a meeting of poets, musicians, actors, visual artists and all parties interested in expressing their art through poetic, musical, graphic or performance-based interventions.

Sarau da Kambinda Held at Teatro Popular Solano Trindade in the city of Embu das Artes, its mission is to promote poetry and meetings between poets and artists that are part of the cultural movement in the city’s periphery and of African origin.

38

Sarau do Binho With a history of over eight years, O Sarau do Binho unites poets, singers, actors and other popular artists and people from the periphery, establishing itself as an important feature on the city of São Paulo’s cultural calendar. The sarau started in a bar. At that time, there were no cultural spaces in the periphery where encounters of this kind could take place. To this day, it is difficult to utilise public spaces for cultural

activities at night. The sarau gave way to many ideas and actions such as Postesia and Postura, an artistic practice which sets up signs with poetry and visual arts in public areas of the city; the installation of a

O Praçarau O Praçarau has been held in São Paulo’s south zone for the past four years. Today, it is the only outdoor sarau, attracting a vastly diverse audience to its performances. Music, dance, poetry, performances, all blended together in a space open to the public. The sarau features the support of several partner groups as well as the local residents.

community library, also in the Campo Limpo region; or the activities of Bicicloteca, which has so far distributed over 5,000 books in houses and bus stops in the neighbourhood. Poetas Ambulantes Inspired by the street vendors who circulate among the collectives, offering their merchandise, Poetas Ambulantes (literally ‘Wandering Poets’) offer passengers spoken and written poetry, in exchange for attention, emotion and interaction. Each month the poets follow a different itinerary.

Sarau Preto no Branco Comprised of a group of young people from Jardim Ibirapuera, it was created in 2012 specifically to encourage young people, poets and artists from the region to express themselves. The group’s members are all under 21, making the event a way to demonstrate that the youth has something to say, addressing such themes as inequality, corruption and prejudice in their poetry and music.

Batalha TSP Founded in Taboão da Serra in August of 2012, TSP is a collective for the dissemination of culture. TSP’s main mission is to foment the culture of independent hip-hop in São Paulo’s periphery.

39

Bonde Sak Funk MC Spyke and MC Preto have been rapping together since 2007. With a repertoire of lyrics that deal with everything from social issues – such as daily life in their community – to the reigning style of baile funk in São Paulo, ‘funk ostentação’, they stand out for their sociallyconscious funk.

Sarau A Plenos Pulmões Organised by Marcos Pezão and Dona Otília, it is held at a variety of venues in the city of São Paulo, featuring the participation of the many poets that have followed the sarau movement for over fifteen years. Marcos Pezão believes in a literature that builds bridges between the city’s inhabitants and breaks down territorial prejudice.

Treme Terra Escultura Sonoras For 22 years Aderbal Ashogun has been promoting actions that bring together visual artists, masters of popular culture and religious leaders from traditional communities and peoples. His best-known work is O Treme Terra Esculturas Sonoras. The intervention combines percussion, rhythm, poetry, urban culture and candomblé culture in an ‘Ancestral Flash Mob’.

40

O Menor Sarau do Mundo A poetry intervention that involves one poet and an audience of up to three people beneath an umbrella. With a duration of one minute and twenty seconds, the poet recites three short poems of his or her authorship with a high factor for stunning the public.

Coral Guarani Xondaro It is a performance of religious chants for children, taught by the village elders, which mainly speak of the religious myth of the Terra Sem Mal (‘The Land of No Evil’), a sacred place for the Guarani people, symbolically located on the other side of the ocean, and the moral values which should guide the lives of each of the community’s members.

Narra Várzea In Brazil, football emerged as futebol de várzea (‘field football’), back when the fields weren’t regulated and didn’t have set rules. The organisation of this amateur sport gave way to the first Clubes de Várzea, basically informal associations and meeting places for friends from the city’s ghettos and outlying communities. Balé Capão Cidadão The project offers workshops of different dance styles (classic ballet, theatre-dance and street dance) to children and teenagers from the Jardim Valquíria’s community, through the Capão Cidadão ngo.

Círculo Palmarino Círculo Palmarino is a national political chain of the black power movement that emerged in 2006 to combine the efforts of those who believe in a new, fair and egalitarian society in which black people can be subject to their own history. Present in the states of Bahia, Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, Sergipe and São Paulo.

Comunidade Cultural Sambaqui Since 2003, the collective has been dedicated to the research and maintenance of Afro culture in São Paulo. Its practices intensify the public contact with traditional masters inside the communities and at the Sambaqui terreiro, and also to promote this culture through presentations, workshops and the transmission of knowledge.

Sarau Poesia na Brasa Since 2008, Sarau Poesia na Brasa has been regularly holding saraus inside a bar (first Bar do Cardoso and then Bar do Carlita), as well as schools and cultural centres. They have released six books and the historical book Tambores da Noite by the great black poet Carlos de Assumpção. In their meetings, drumming and oral expression are the main vehicles for communion, thus reclaiming traditions that are thousands of years old.

Sarau O que Dizem os Umbigos?! Today, the mass culture of television and technology rules, human relationships are more and more limited to the individual realm, and we end up distancing ourselves from dialogues, exchanges of experiences and the exercise of listening; let us stop ‘gazing at our navels so much and start dialoguing with other people’s navels’.

Núcleo de Dança Pelagos The Núcleo was created in 2010 by the hands of Projeto Arrastão and the nowadays-professional ballet dancer Rubens Oliveira. The project has the purpose of initiating teens between fifteen and eighteen years of age in their corporal development and of promoting a deepest connection between art and general culture.

41

Open Meetings

LIMA, Peru 22 NOV 2013 – El Galpón Espacio in collaboration with: Miguel A. López report: Florencia Portocarrero and Horacio Ramos LONDON, England 10 JUN 2014 – Whitechapel Gallery in collaboration with: Sofia Victorino report: Helena Vilalta MADRID, Spain 20 FEB 2014 – Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (mncars) in collaboration with: Jesús Carrillo reports: Francisco de Godoy and Laura Vallés BOGOTÁ, Colombia 31 JAN 2014 – FLORA ars + natura in collaboration with: Jose Roca HOLON, Israel 20 FEB 2014 – The Israeli Center for Digital Art SANTIAGO, Chile 12 MAR 2014 – Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC), Facultad de Artes, Universidad de Chile

BRASÍLIA, Brazil 14 AUG 2014 – Beijódromo – Universidade de Brasília (UnB)

SÃO JOSÉ DO RIO PRETO, Brazil NOV 2014 – sesc São José do Rio Preto

SÃO CARLOS, Brazil 24 MAY 2014 – sesc São Carlos in collaboration with: Sandra Frederici and Sandra Leibovici report: David Sperling

SOROCABA, Brazil 26 APR 2014 – sesc Sorocaba in collaboration with: Katia Pensa Barelli and Sandra Leibovici report: Ellen Nunes

42

BELÉM, Brazil 19 DEC 2013 – Instituto de Artes do Pará (iap) in collaboration with: Orlando Maneschy report: Maria Christina Barbosa

FORTALEZA, Brazil 7 NOV 2013 – unifor in collaboration with: Adriana Helena report: Luciana Eloy

RECIFE, Brazil 13 NOV 2013 – Espaço Fonte in collaboration with: Cristiana Tejo reports: Olívia Mindêlo and Paulo Tarso

SALVADOR, Brazil 23 JAN 2014 – Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia (mam-ba) in collaboration with: Marcelo Rezende reports: Ludmilla Britto and Rosa Gabriela de Castro Gonçalves BELO HORIZONTE, Brazil 6 FEB 2014 – Museu Mineiro in collaboration with: Júlia Rebouças report: Francisca Caporalli

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil 6 JUL 2014 – Largo das Artes in collaboration with: Consuelo Bassanesi report: Icaro Ferraz Vidal

SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL 6 AUG 2013 – Bienal de São Paulo Curatorial Perspectives

SANTOS, Brazil OCT 2014 – sesc Santos

20 AUG 2013 – Bienal de São Paulo The Art Market 30 NOV 13 – Casa do Povo Art and Education reports: Daniela Gutfreund and Sabrina Moura 22 MAR 2014 – sesc Pompeia The City and Its Spaces in collaboration with: Daniela Avelar and Sandra Leibovici reports: Joana Zatz Mussi and Ligia Nobre

PORTO ALEGRE, Brazil 11 OCT 2013 – Santander Cultural in collaboration with: Bernardo de Souza reports: Luísa Kiefer and Michelle Sommer

26 JUL 2014 – sesc Belenzinho The Production of Discourse in Brazil in collaboration with: Mauro Lucas report: Isabella Rjeille

43

The Open Meetings are a series of encounters organised by the 31st Bienal’s curatorial and Educativo Bienal teams in collaboration with individuals and institutions throughout Brazil and other international locations, in which people involved in art, culture and activism gather to discuss fundamental concerns and urgencies of their own. These meetings, structured as an open dialogue, work both as a research tool and a critical assessment of the curatorial process, engaging artists, critics, curators, cultural organisers and others in a process that renders open the process of organising the 31st Bienal. Each of the meetings adopts different formats in order to explore the diverse possibilities of public discussion forums, and in response to contrasting urgencies. They formulate diverse questions and expose the intentions, workings and developments within the development of the 31st Bienal. All the meetings have been critically assessed by commissioned reviewers, with the resulting material made available through the 31st Bienal’s website, providing access to the curatorial process as an open pedagogical process.

Juan Downey, Untitled, 1988

44

A Toolbox for Cultural Organisation A Toolbox for Cultural Organisation, part of the 31st Bienal education programme, is a three-week workshop extended over 10 months in 2014. This workshop gives sixteen young curators, artists, writers, educators and/or cultural activators (selected after an open submission call) the chance to engage in a critical exchange about organisation and intervention in artistic and cultural contexts. The aim of the workshop is to provide, share and compare tools for critical engagement today; it intends to be an intervention, questioning existing modes of relating and operating, and investigating the applicability of diverse strategies in different contexts. The participants in the workshop are Ana Maria Maia, Andrés Ennen, Carolina Vieira, Caroline Menezes, Daniel Jablonski, Florencia Portocarrero, Gabriela Motta, Júlio Martins, Lígia Afonso, Lorenzo Sandoval, Lucas Oliveira, Michelle Sommer, Mónica Amieva, Renan Araujo, Rodolfo Andaur and Sabrina Moura. The workshop includes the participation of the 31st Bienal’s curatorial team and guests, both Brazilian and international.

Week One: Writing Histories

Week Two: Conflict Zones

Dates: 27–31 January Monday to Friday, 14h–20h Location: Centro Cultural São Paulo and visit to Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo Guests: Ana Longoni, Ivo Mesquita and Walid Raad

Dates: 13–17 May Tuesday to Saturday, 14h–20h Location: sesc Vila Mariana Guests: Cauê Alves, Daniel Lima, Luisa Duarte, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz and Ricardo Basbaum

Monday: Introduction First part: Introduction to the workshop, aims and structure Second part: Short presentations by the participants Tuesday: Exhibitions Histories/ Biennial Histories First part: Charles Esche and Pablo Lafuente – On Writing the History of Exhibitions: What Does It Mean, How Can It be Done? Second part: Charles Esche – On Writing the Histories of Biennials Wednesday: Between Art and Politics: Argentina First part: Ana Longoni – Between Art and Politics in Argentina Second part: Planning for May week. Thursday: Narrating the Collection (visit to the Pinacoteca do Estado) First part: Ivo Mesquita – A History of Art in Brazil: The Pinacoteca Second part: Charles Esche – Three Museum Experiences outside of the Museum Friday: Art, Disaster and Fiction: Case Studies from Arab Lands First part: Walid Raad – Scratching (Arab) Art Second part: Goodbye drinks at Praça Roosevelt