35th bienal de são paulo

choreographies of the impossible

(eds.)

diane lima

grada kilomba

hélio menezes

manuel borja-villel

catalogue

35th bienal de são paulo choreographies of the impossible

The Ministry of Culture, São Paulo State Government, through the Secretary of Culture, Creative Economy and Industry, the Municipal Secretary of Culture, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo and Itaú present

35th bienal de são paulo choreographies of the impossible

ahlam shibli → 52

aida harika yanomami, edmar tokorino yanomami and roseane yariana yanomami → 54

aline motta → 56

amador e jr. segurança patrimonial ltda. → 58

amos gitaï → 60

ana pi and taata kwa nkisi mutá imê → 62

anna boghiguian → 64

anne-marie schneider → 66

archivo de la memoria trans (amt) → 68

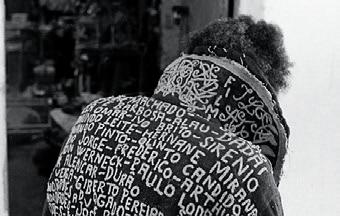

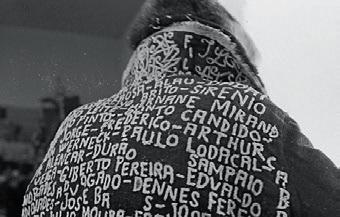

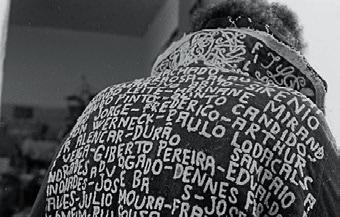

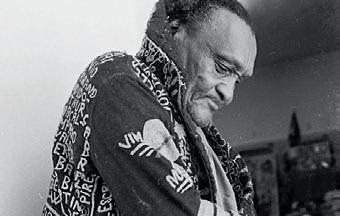

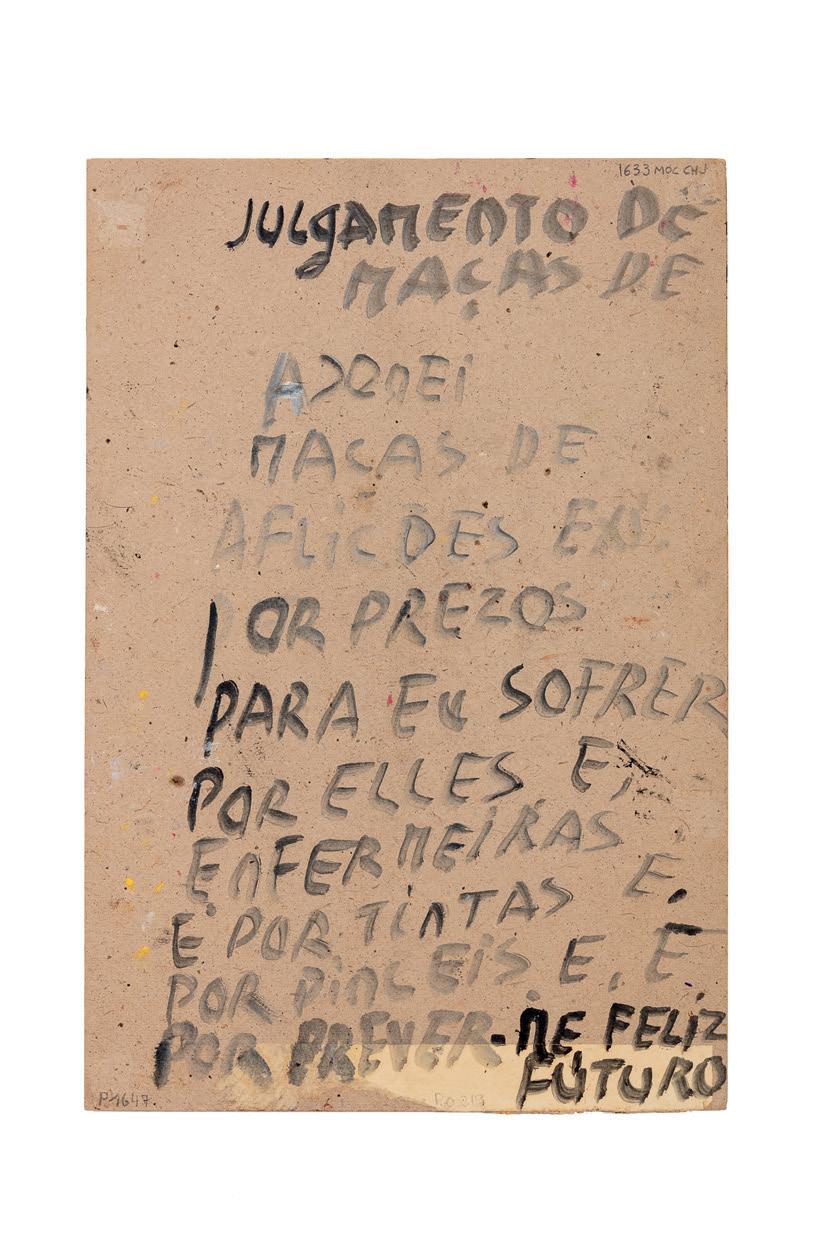

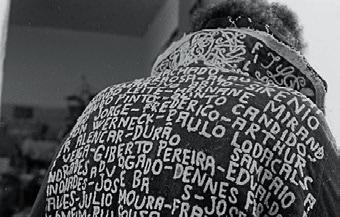

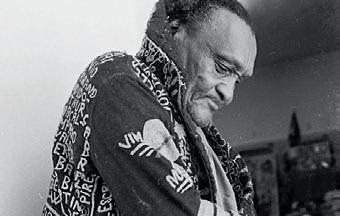

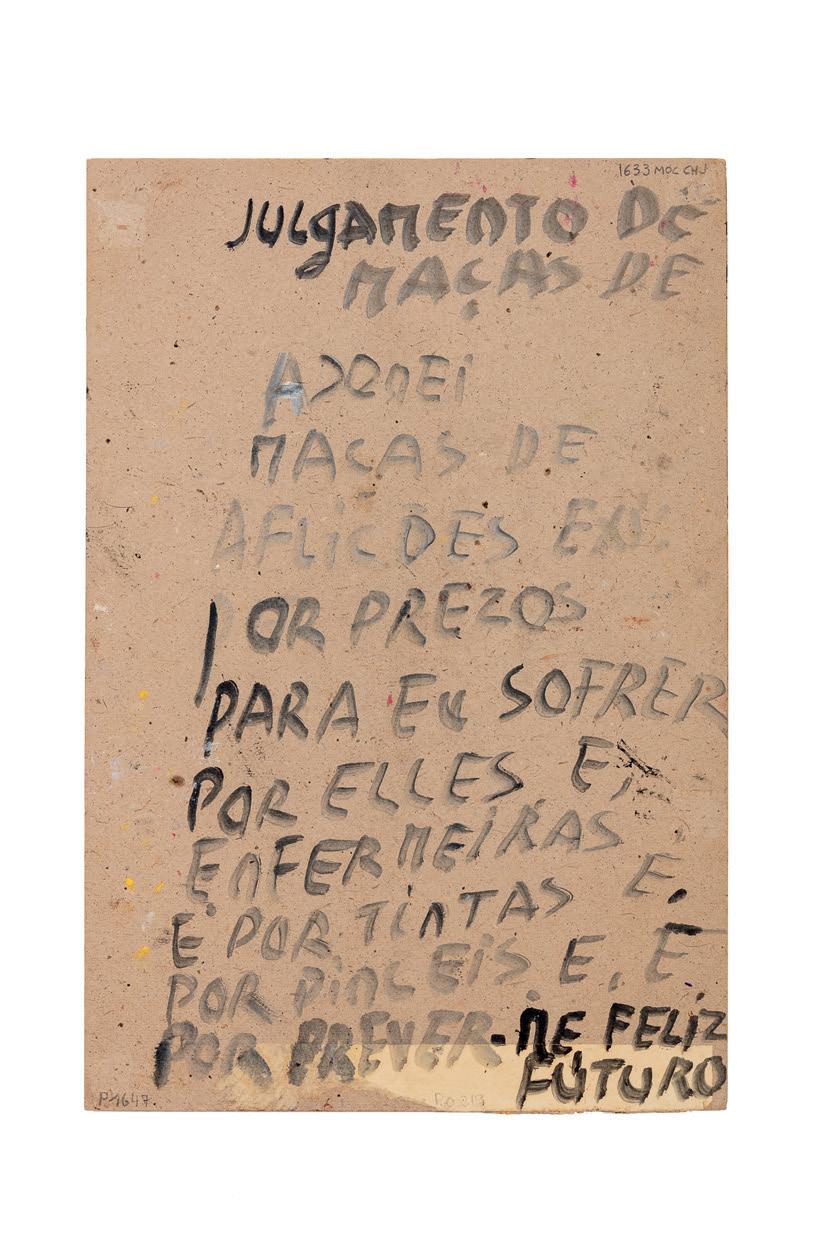

arthur bispo do rosário → 70

aurora cursino dos santos → 72

ayrson heráclito and tiganá santana → 74 benvenuto chavajay → 76 bouchra ouizguen → 78

cabello/carceller → 80

carlos bunga → 82

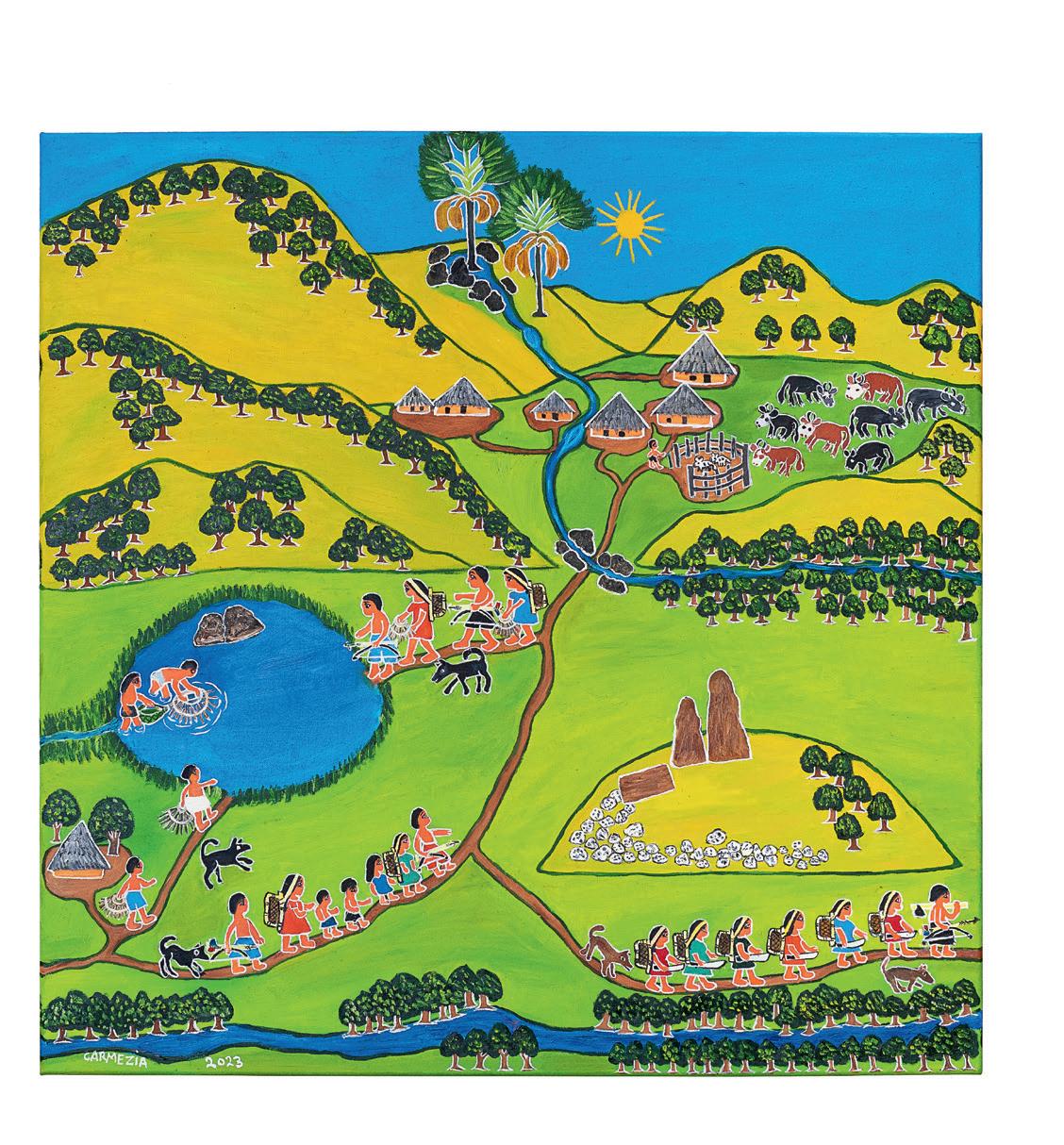

carmézia emiliano → 84

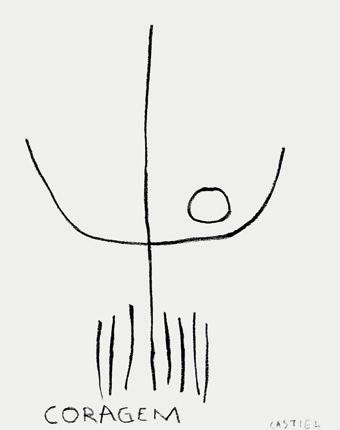

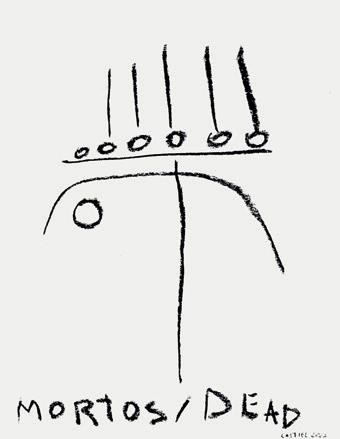

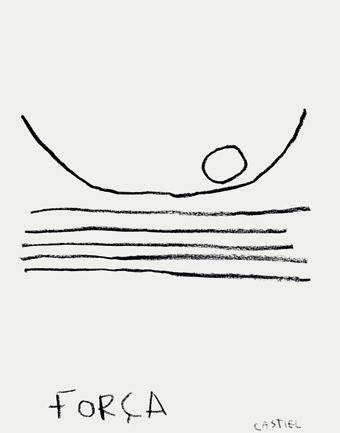

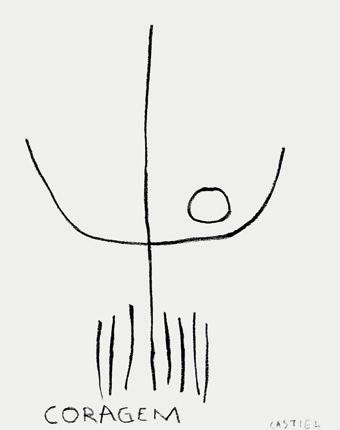

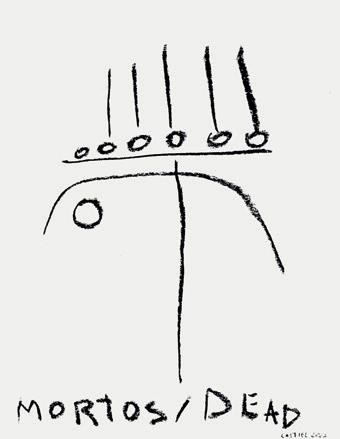

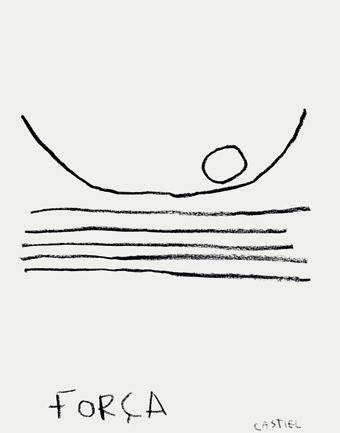

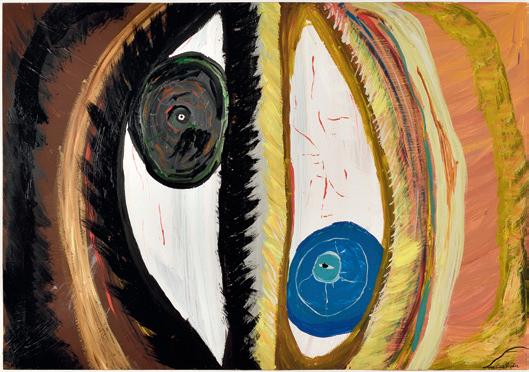

castiel vitorino brasileiro → 86

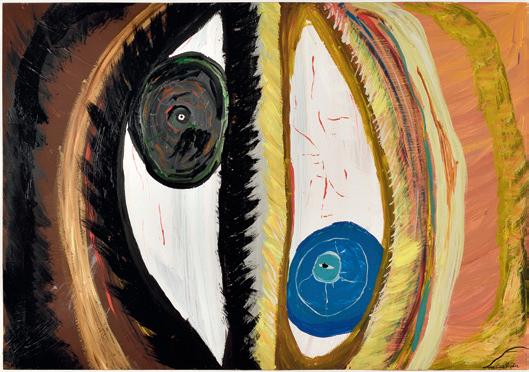

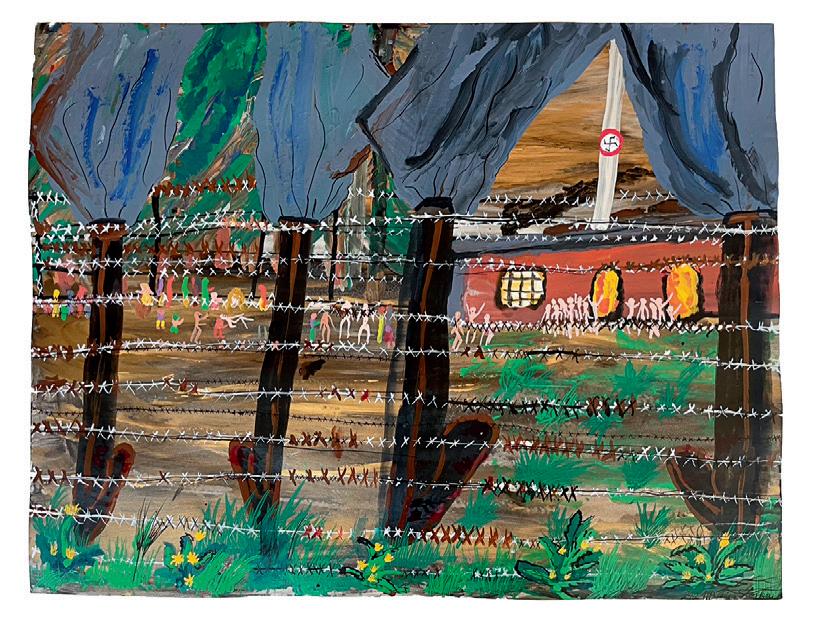

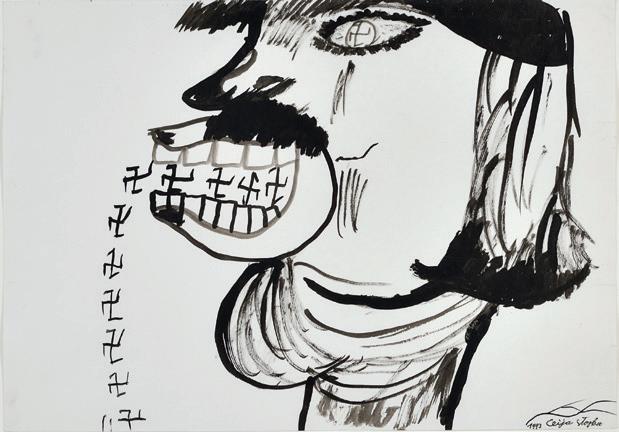

ceija stojka → 88

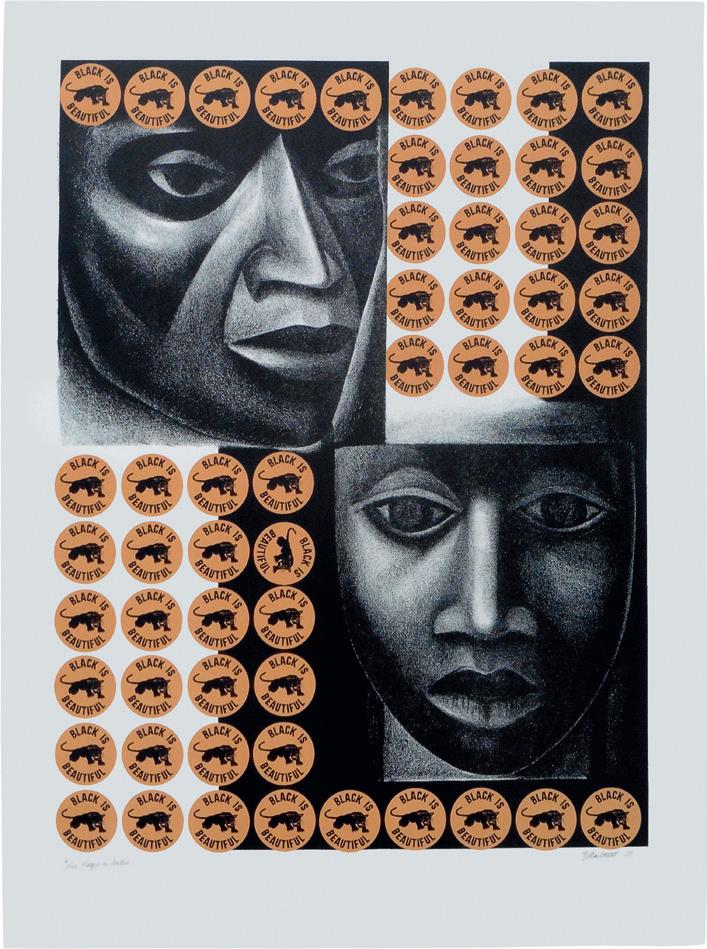

charles white → 286

citra sasmita → 90

colectivo ayllu → 92

cozinha ocupação 9 de julho – mstc → 94

edgar calel → 118

elda cerrato → 120

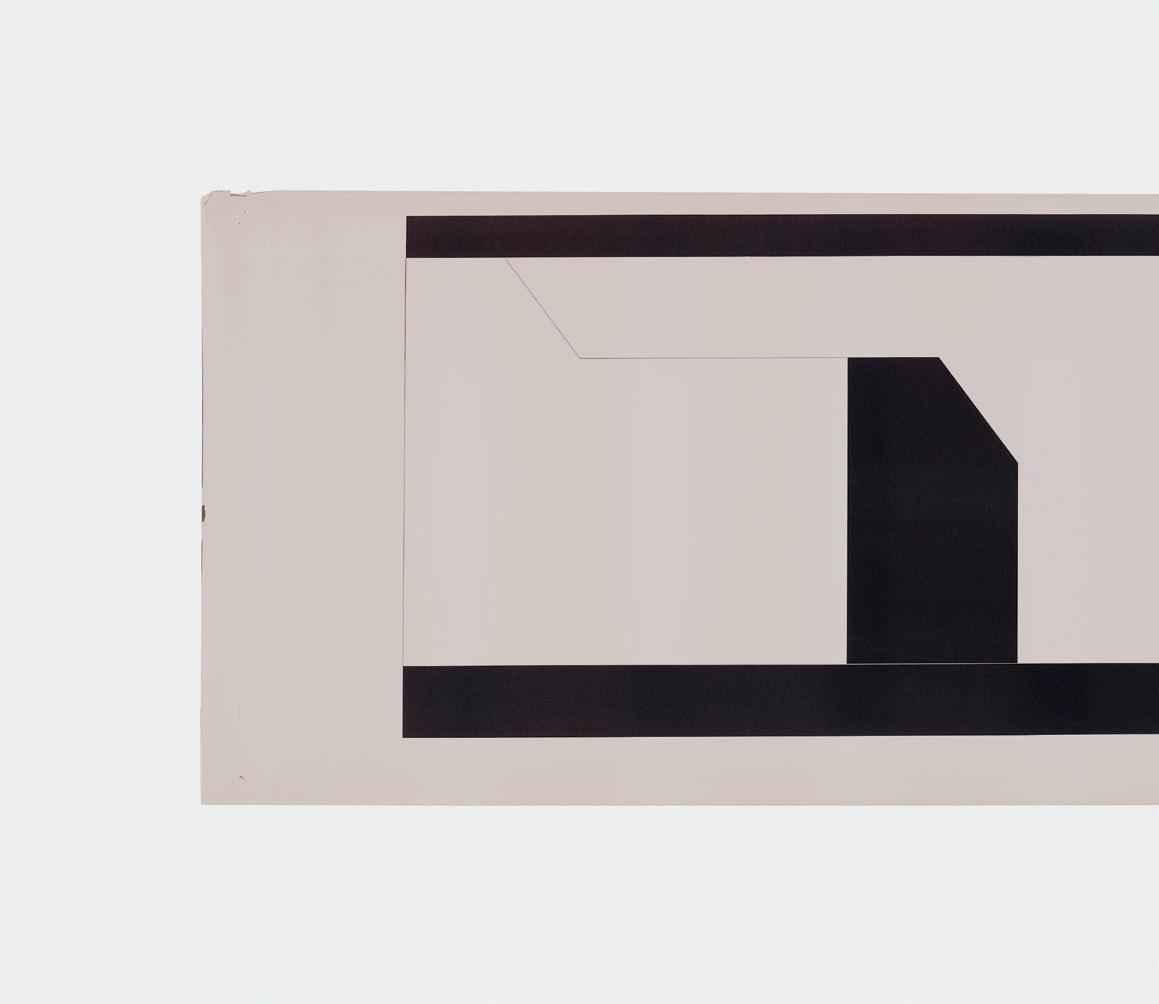

elena asins → 122

elizabeth catlett → 285

ellen gallagher and edgar cleijne → 124

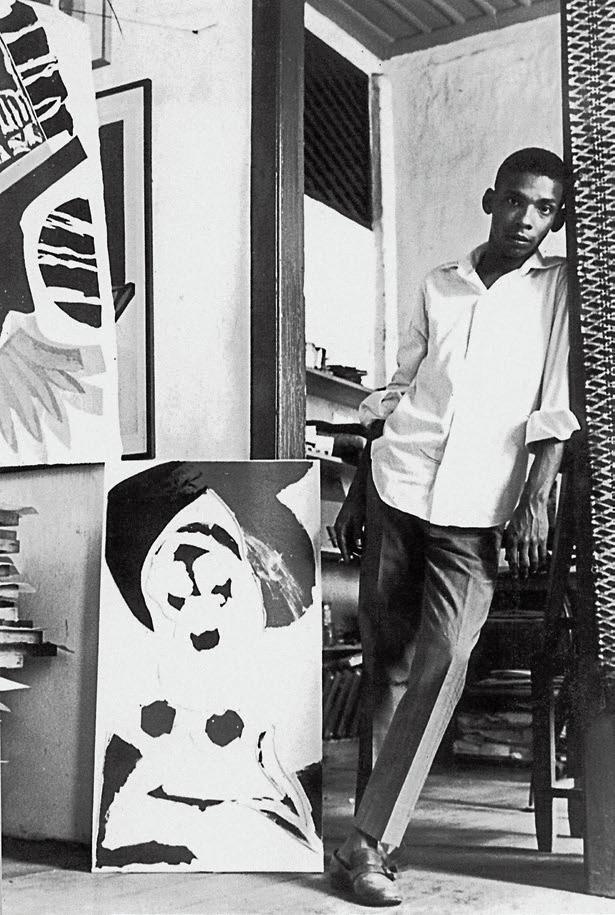

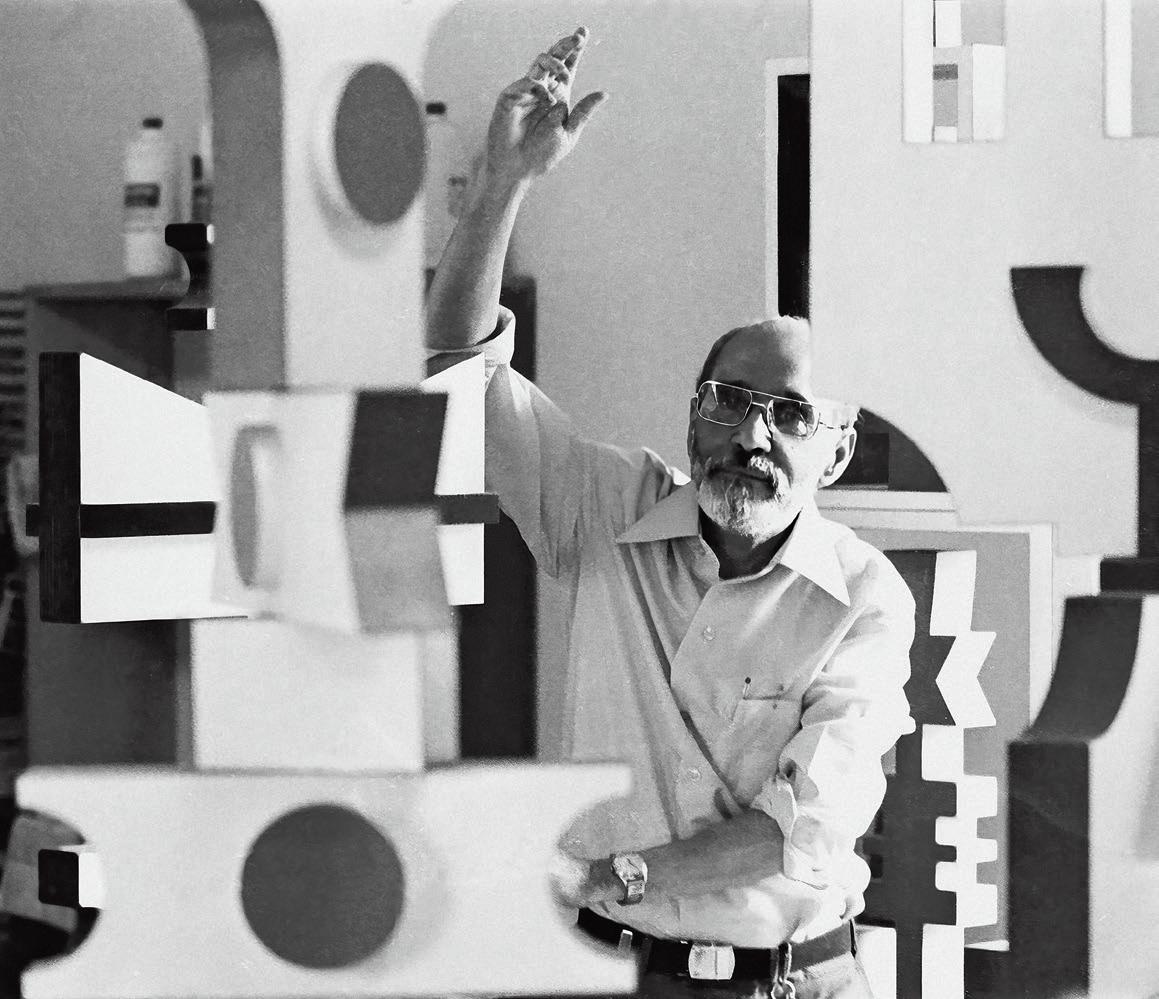

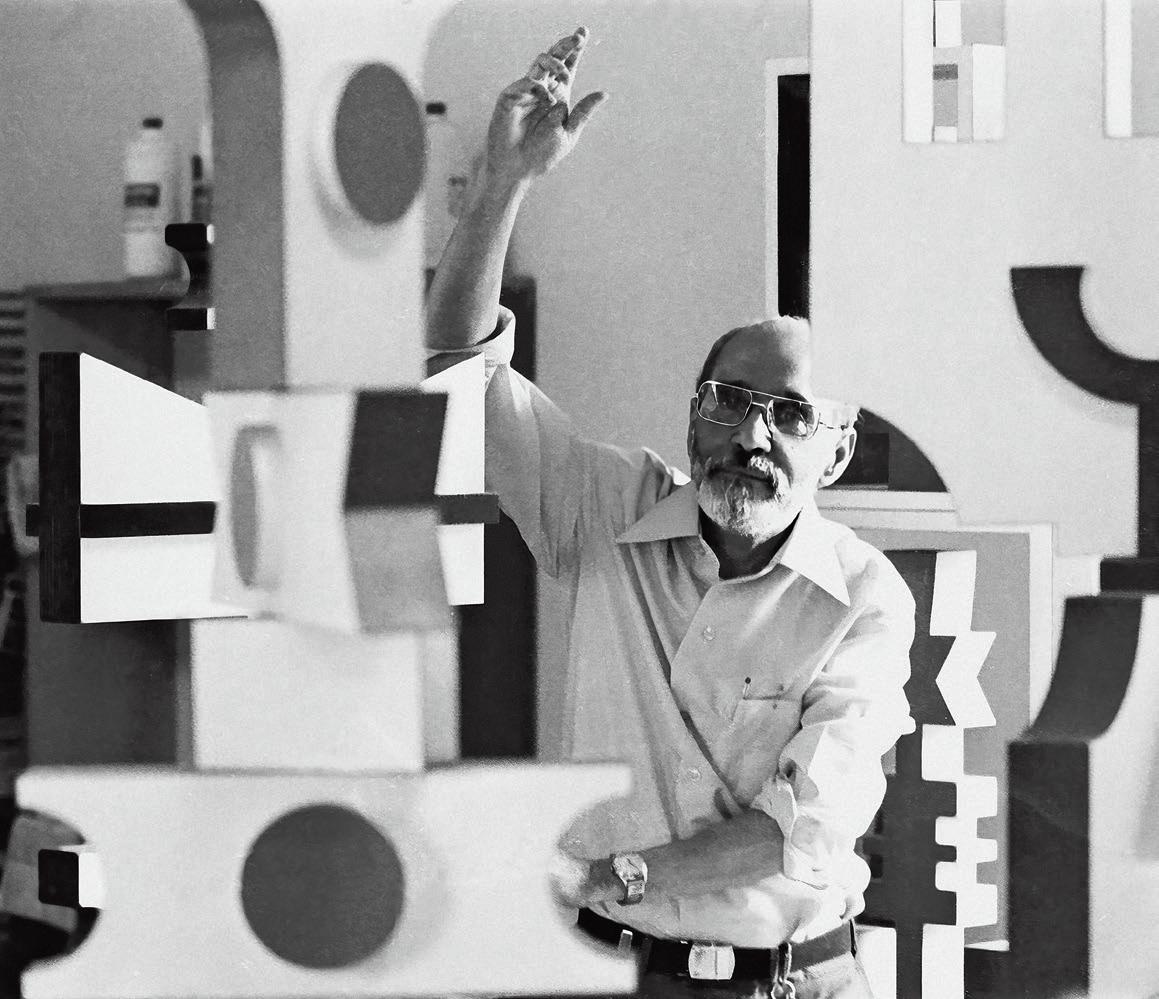

emanoel araujo → 126

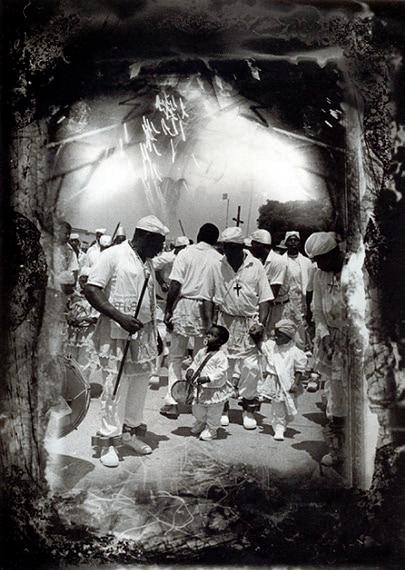

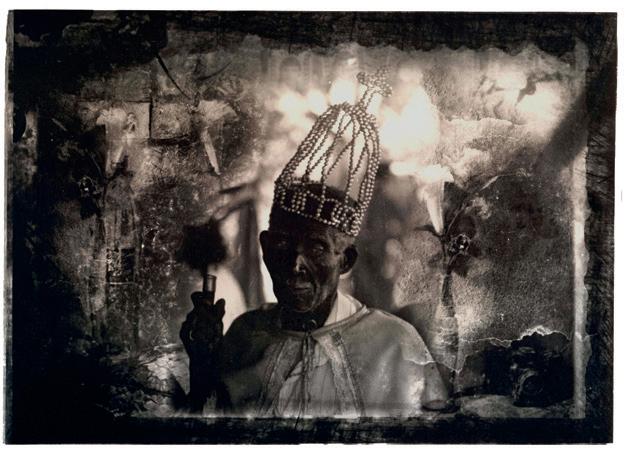

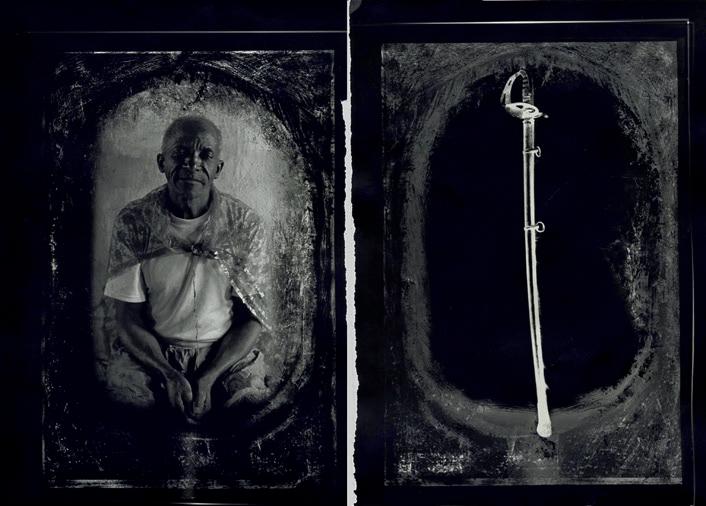

eustáquio neves → 128

gabriel gentil tukano → 136

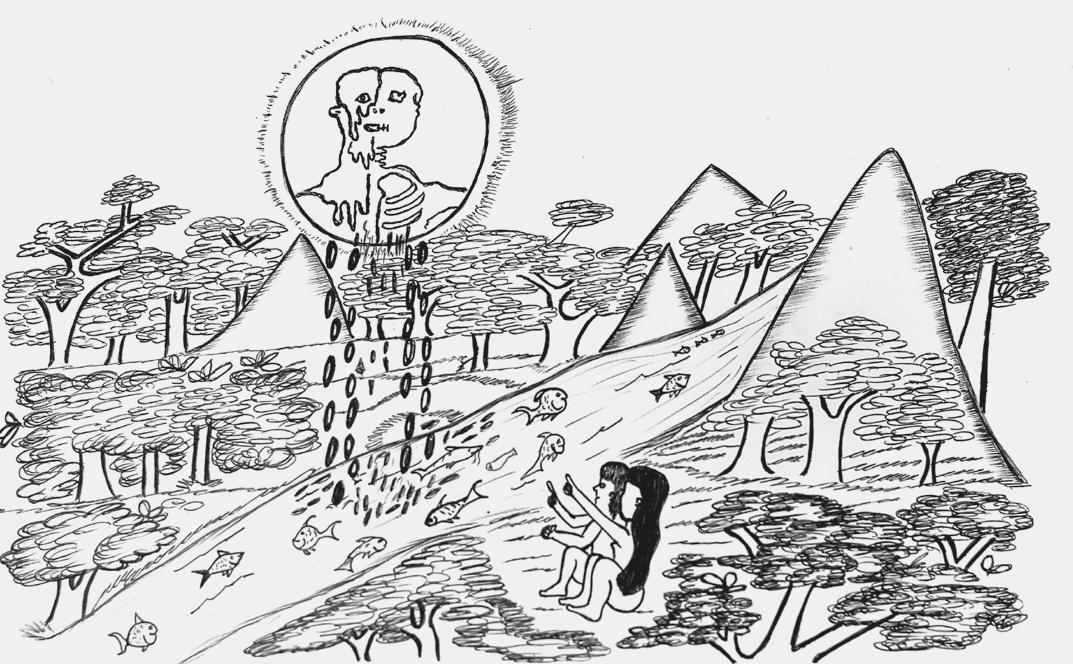

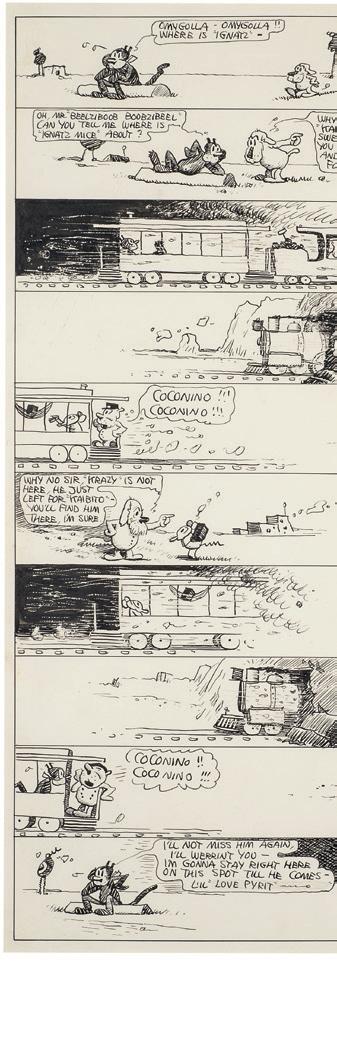

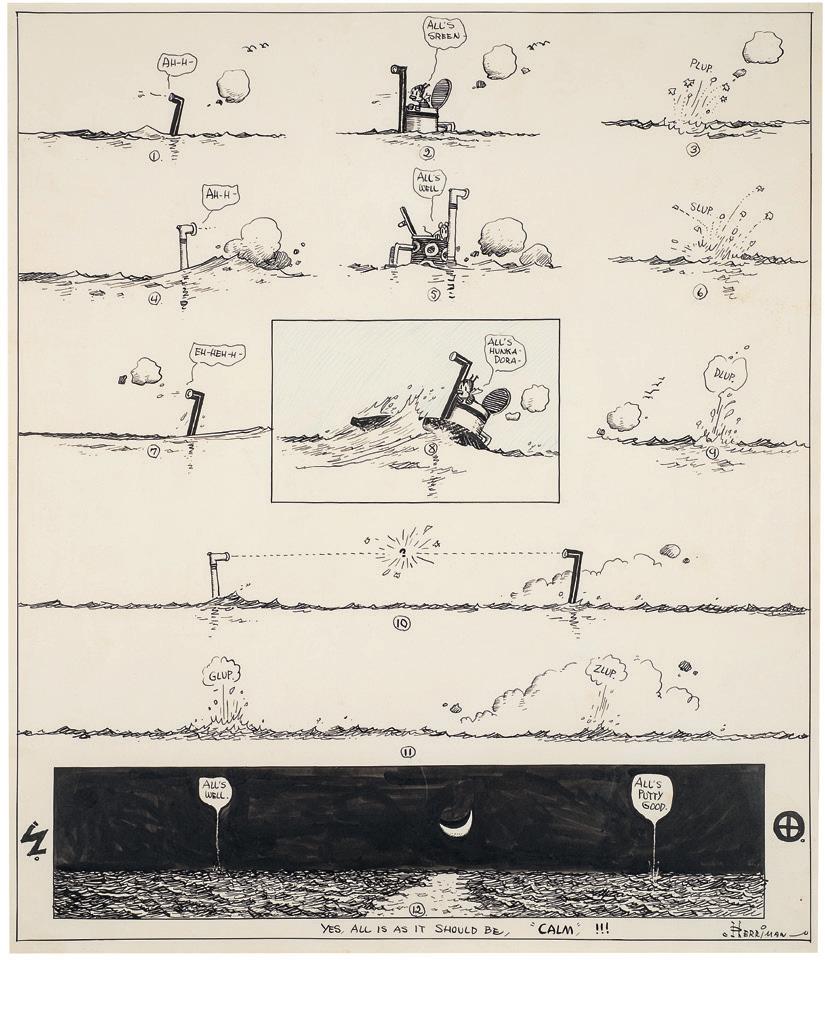

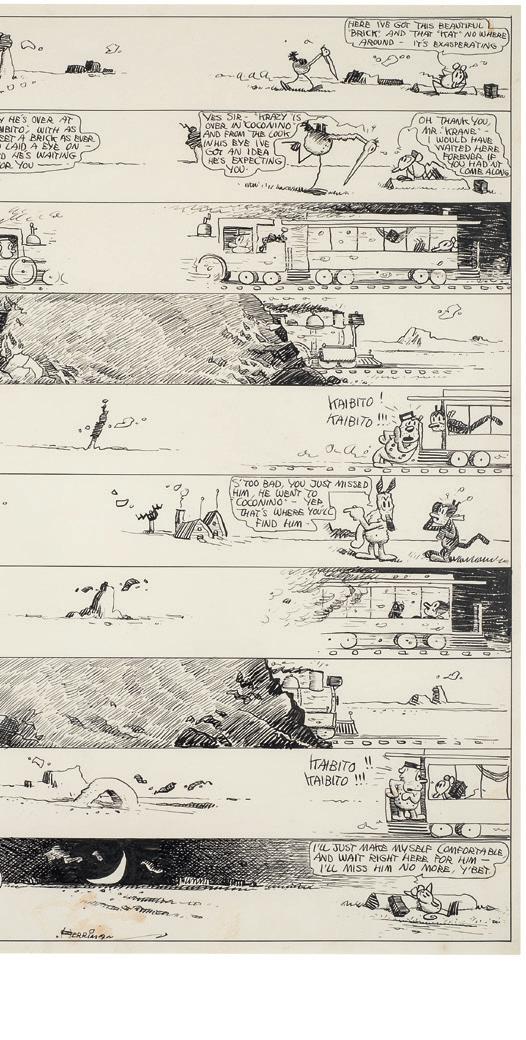

george herriman → 138

geraldine javier → 140

gloria anzaldúa → 142

grupo de investigación en arte y política (giap) → 144

guadalupe maravilla → 146

ibrahim mahama → 154

igshaan adams → 156

ilze wolff → 158

inaicyra falcão → 160

januário jano → 162

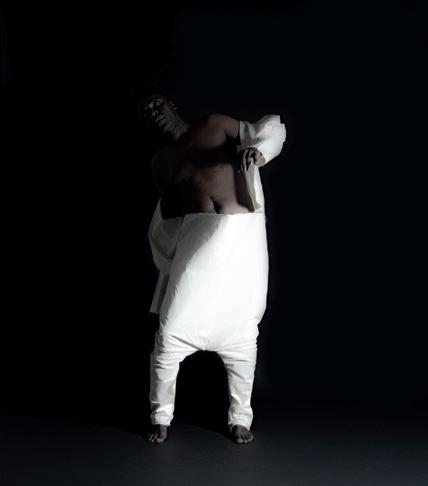

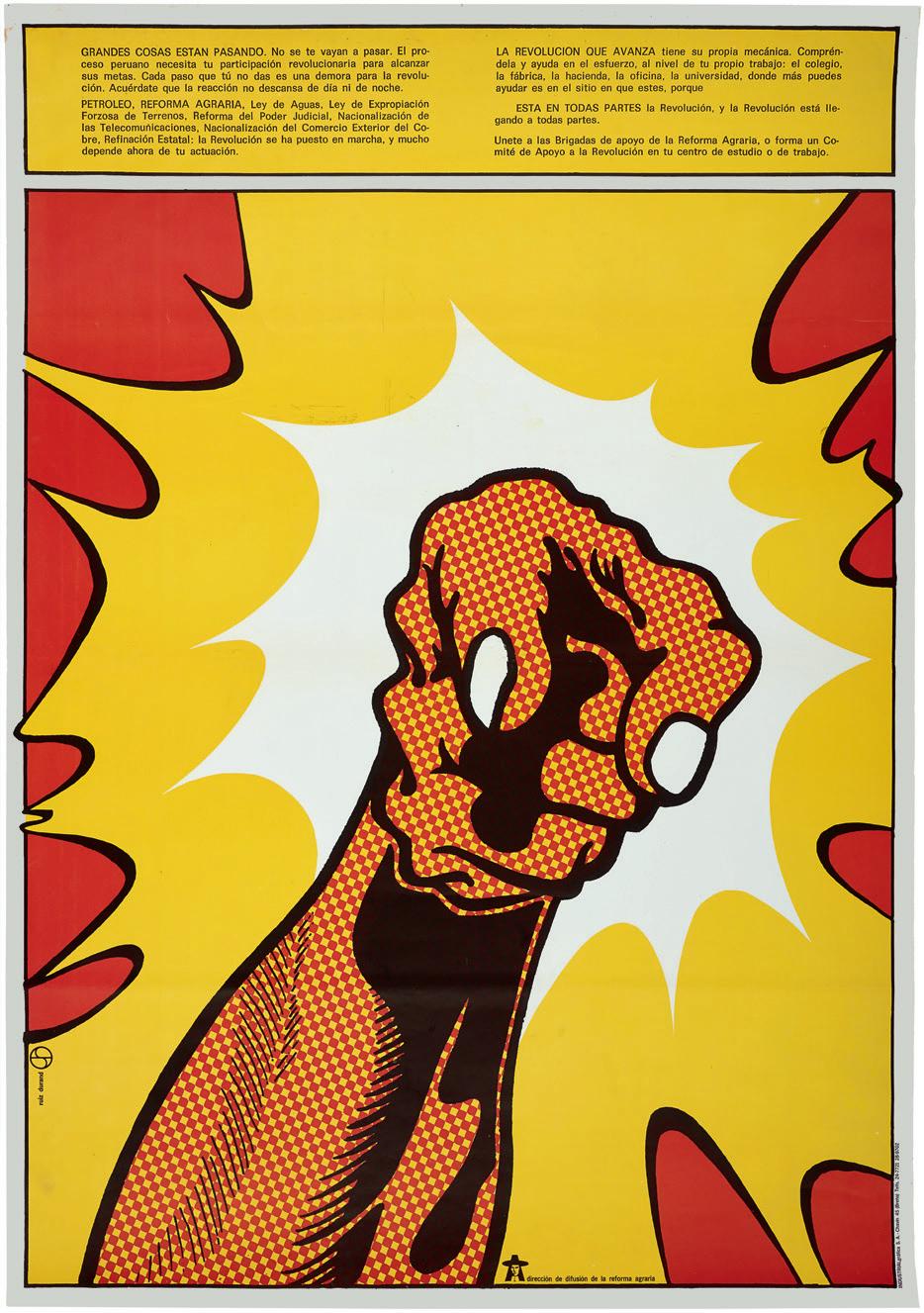

jesús ruiz durand → 164

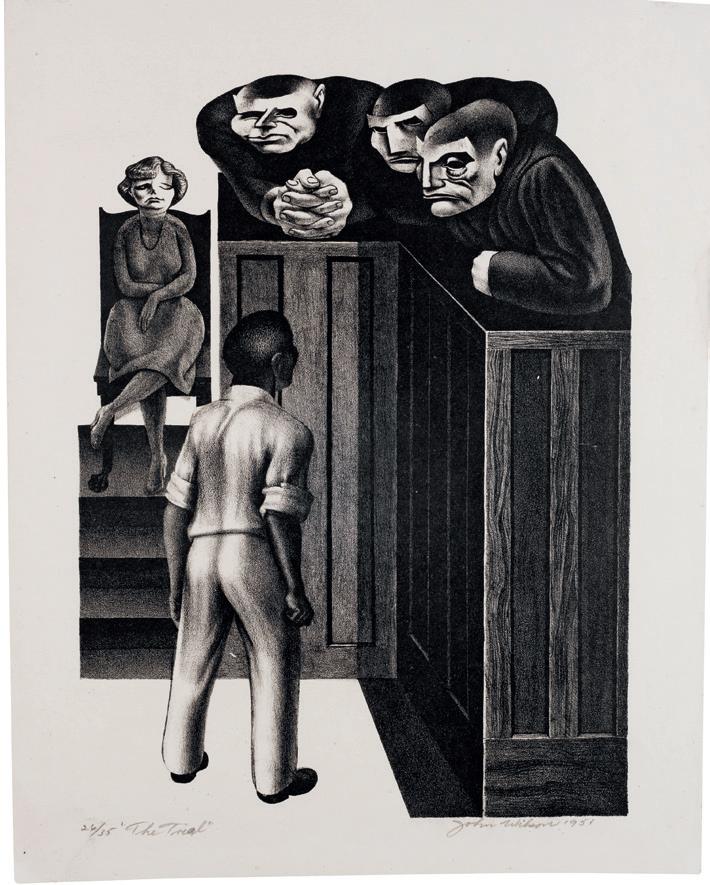

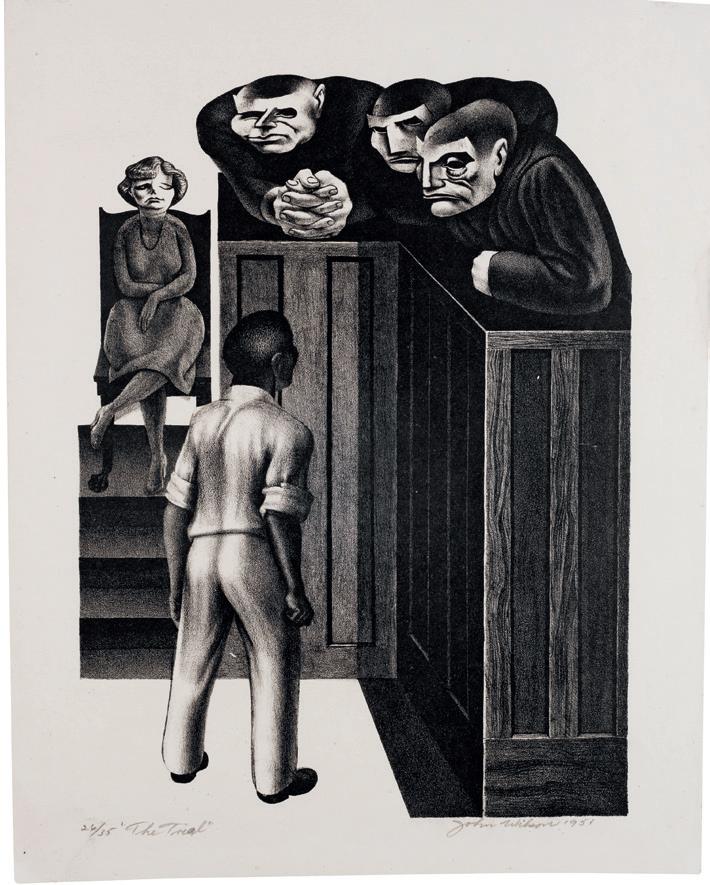

john woodrow wilson → 287

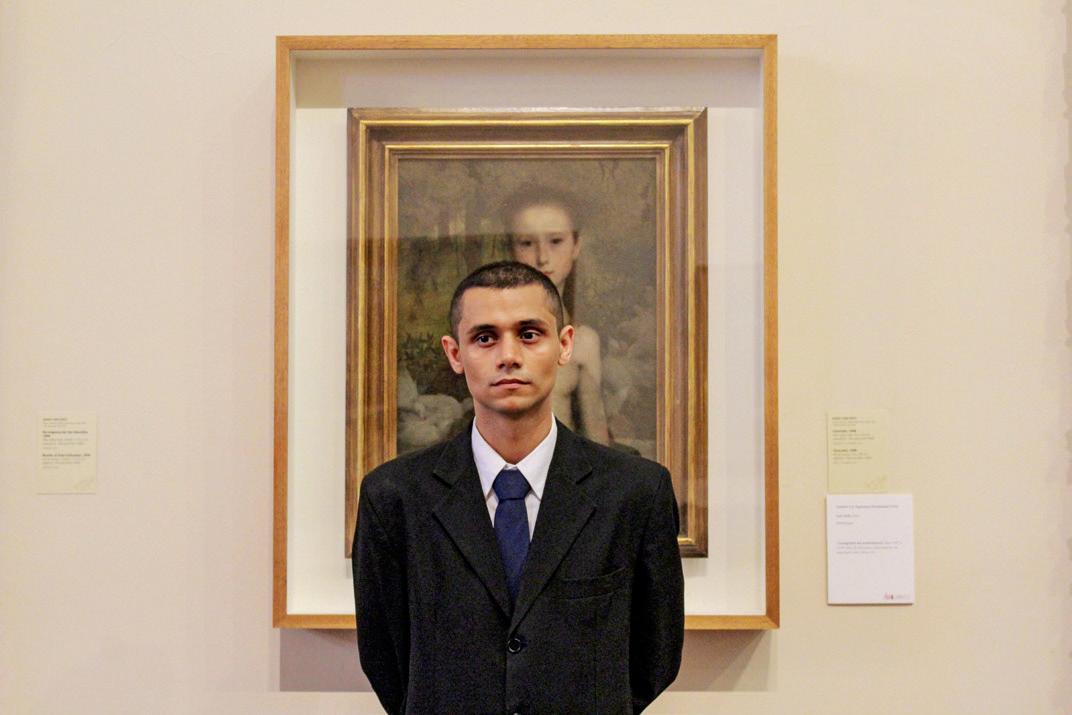

jorge ribalta → 166

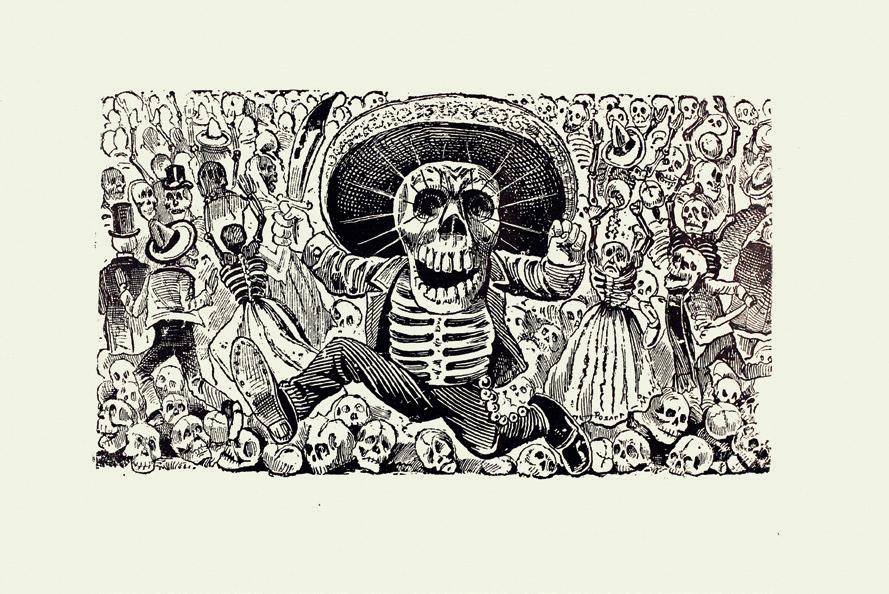

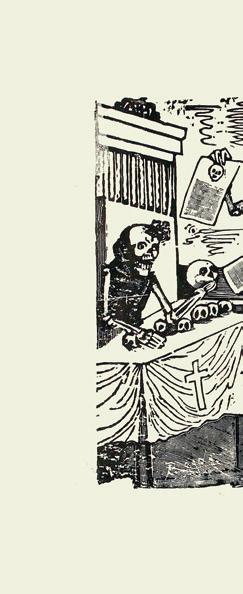

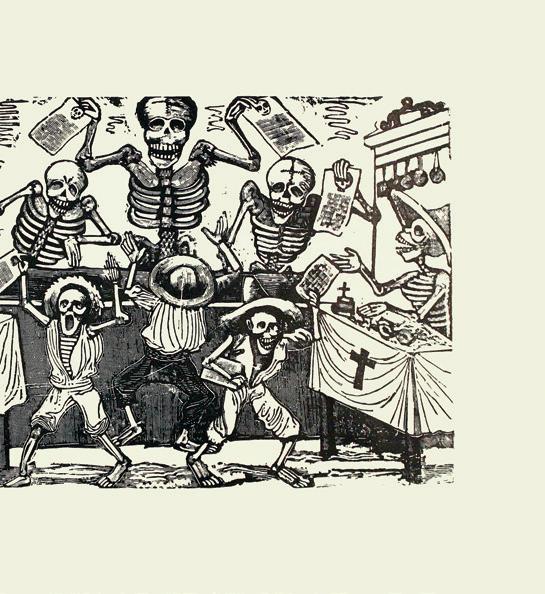

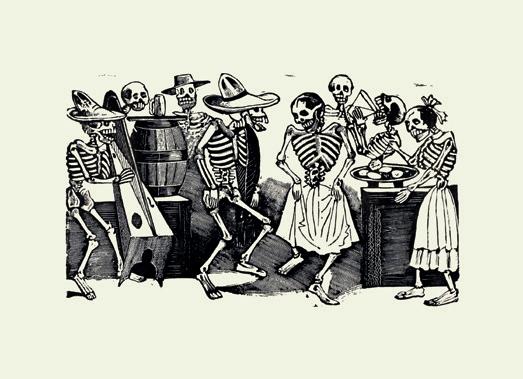

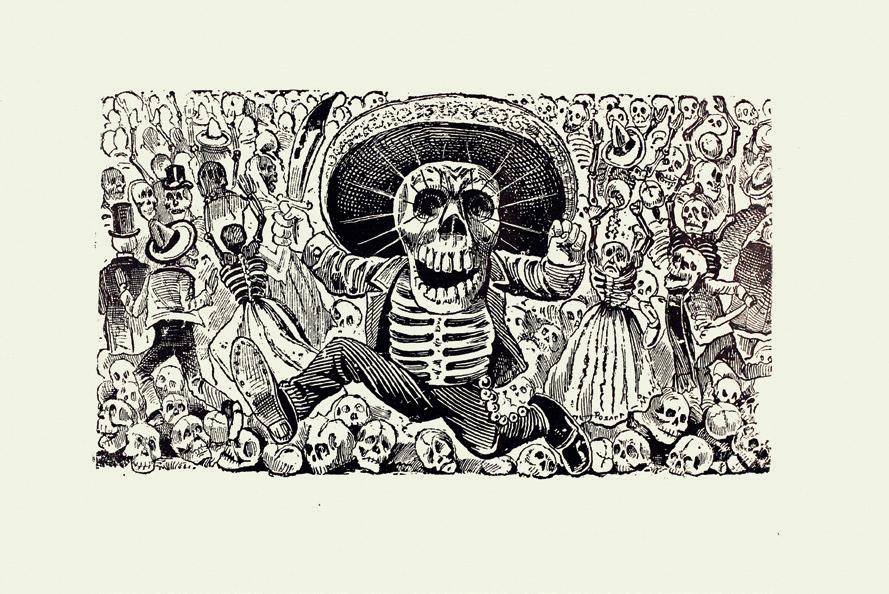

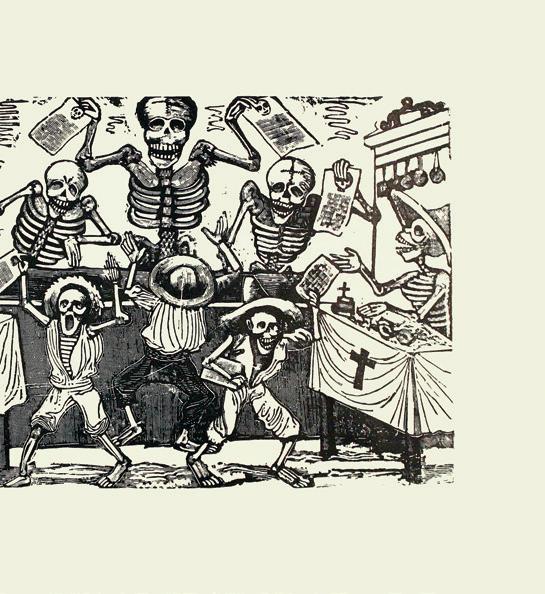

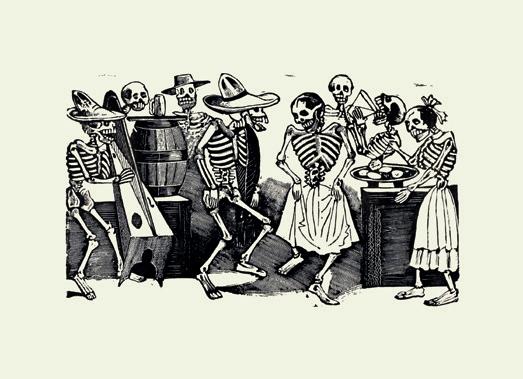

josé guadalupe posada → 168

juan van der hamen y león → 170

judith scott → 172

julien creuzet → 174

daniel lie →

daniel lind-ramos → 102 davi pontes and wallace ferreira → 104 dayanita singh → 106 deborah anzinger → 108 denilson baniwa → 110 denise ferreira da silva → 112 diego araúja and laís machado → 114 duane linklater → 116

100

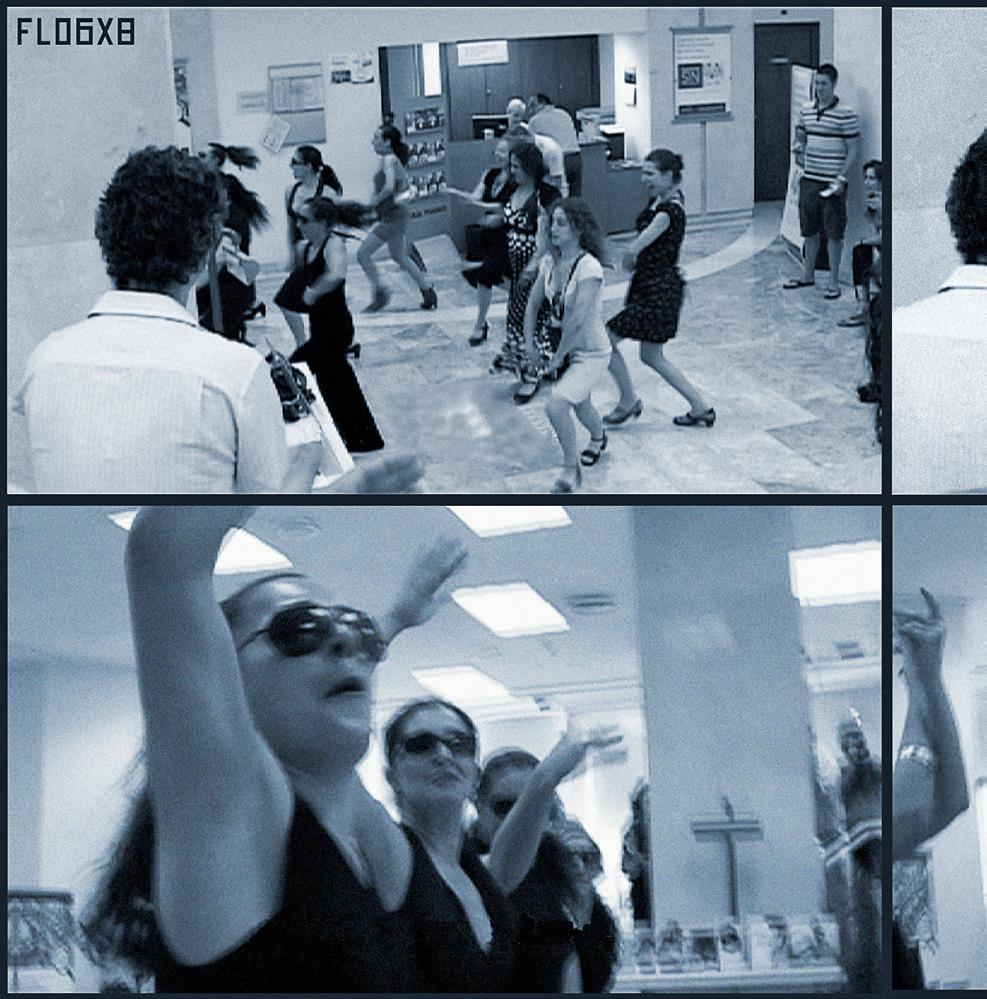

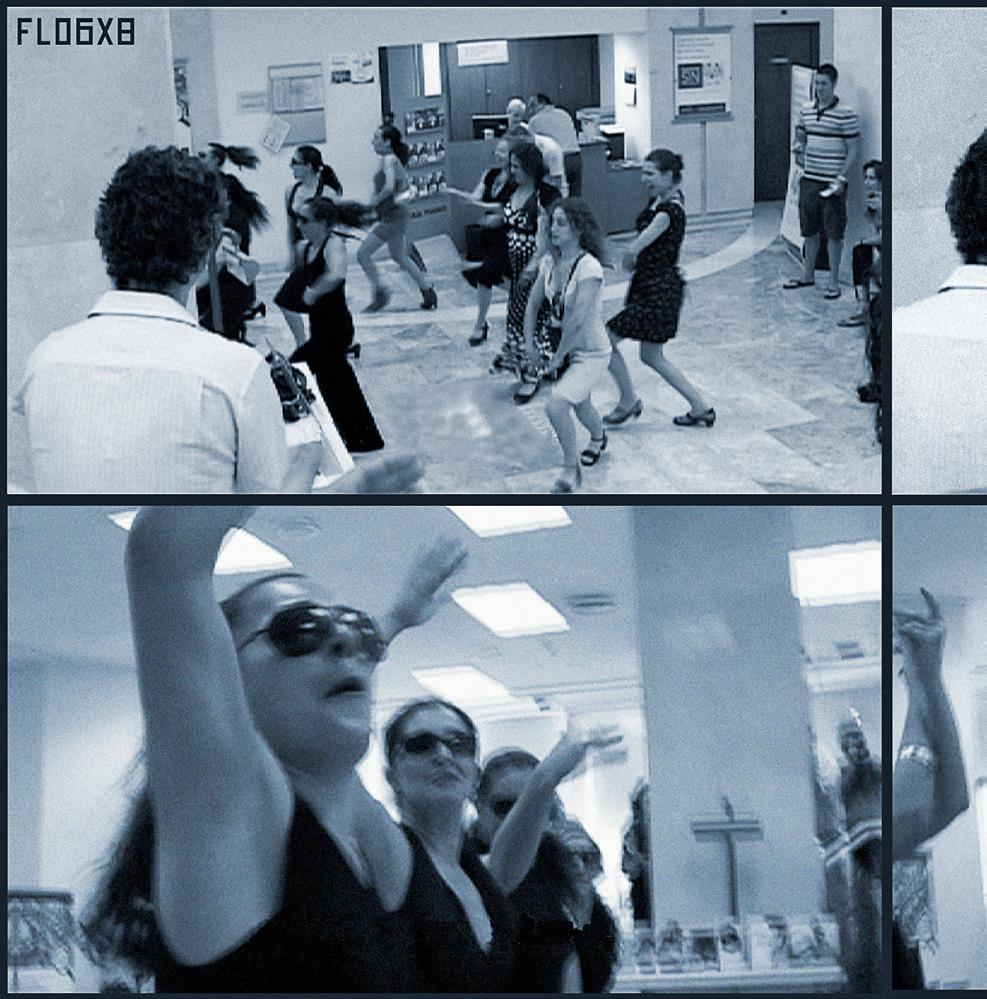

flo6x8

francisco toledo

frente

→ 130

→ 132

3 de fevereiro → 134

kamal aljafari → 176

kapwani kiwanga → 178

katherine dunham → 180

kidlat tahimik → 182

leilah weinraub → 184

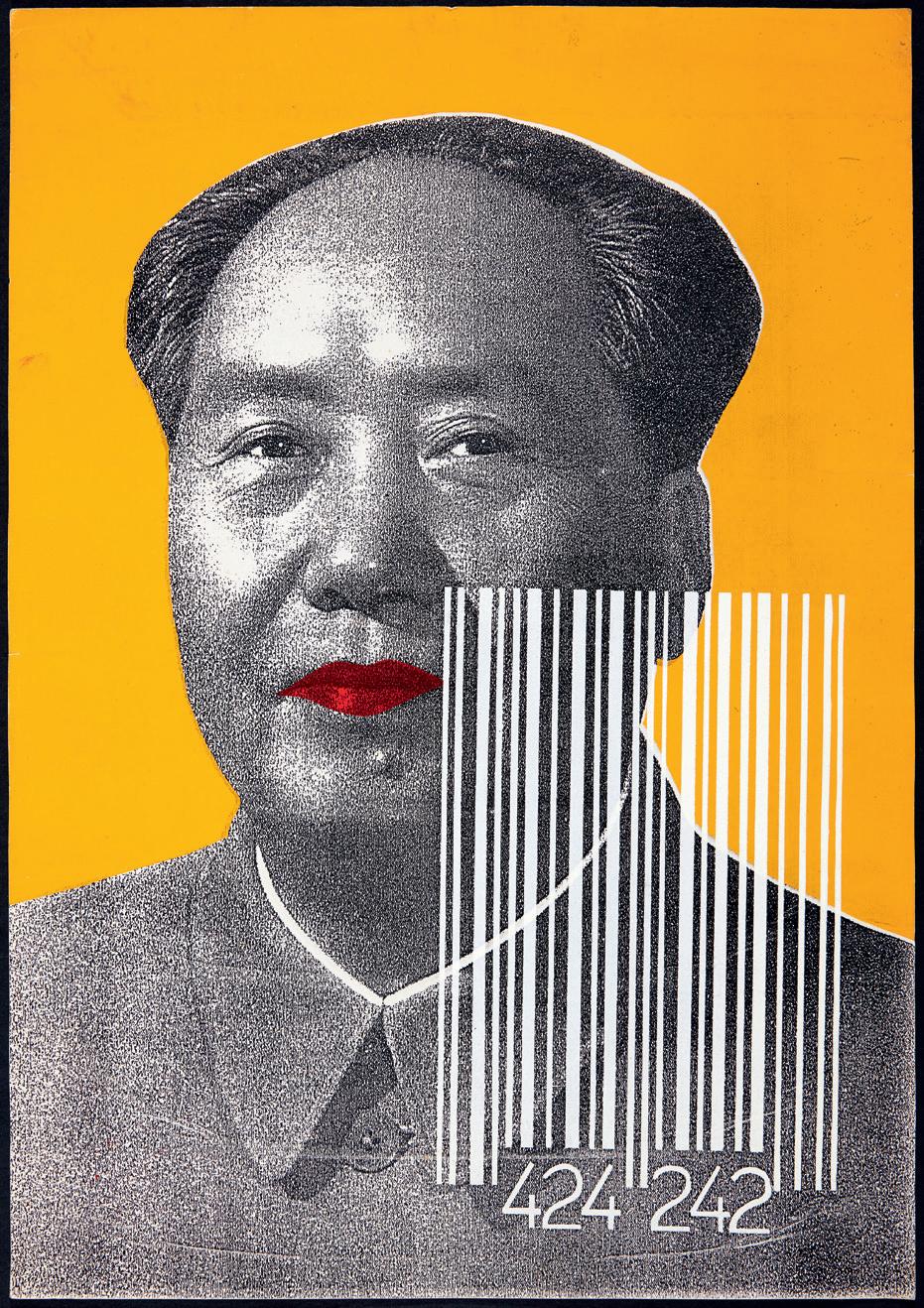

leopoldo méndez → 289

luana vitra → 186

luiz de abreu → 188

m'barek bouhchichi → 190

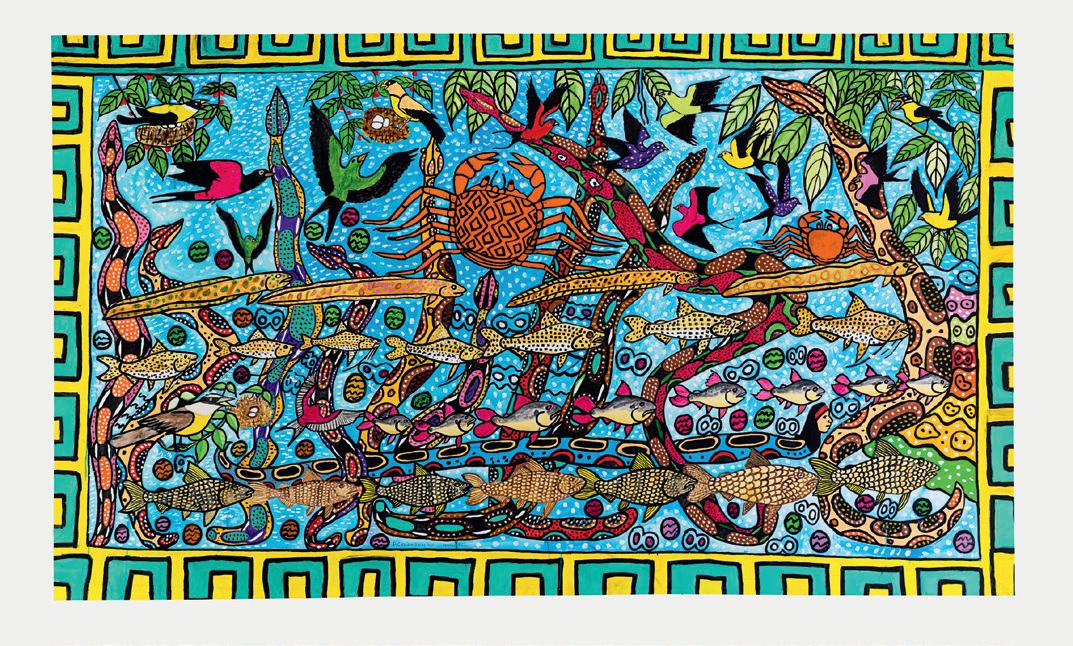

mahku → 192

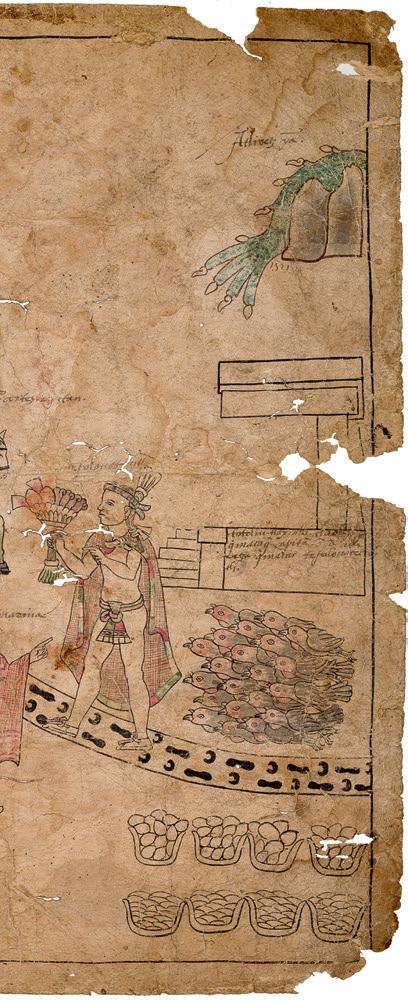

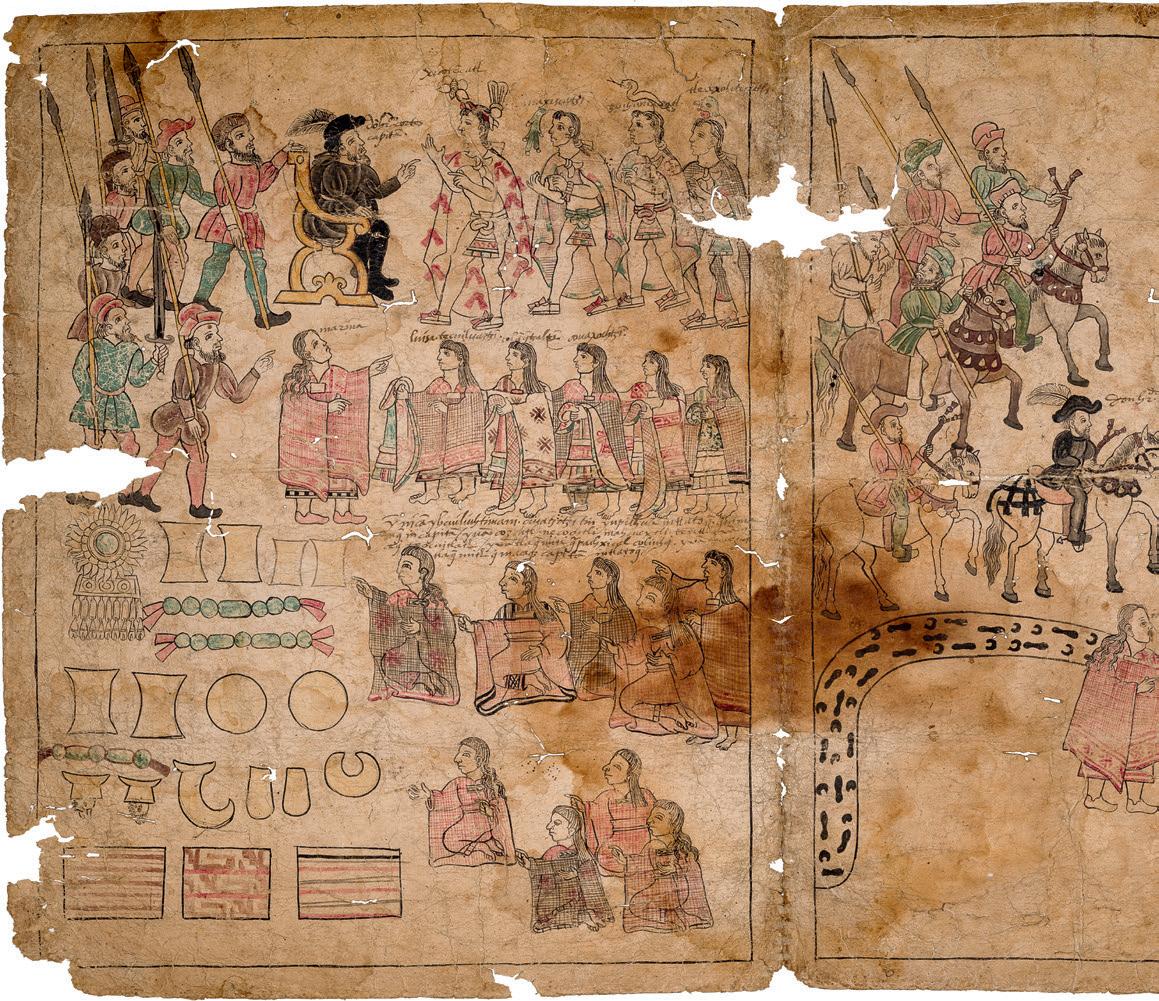

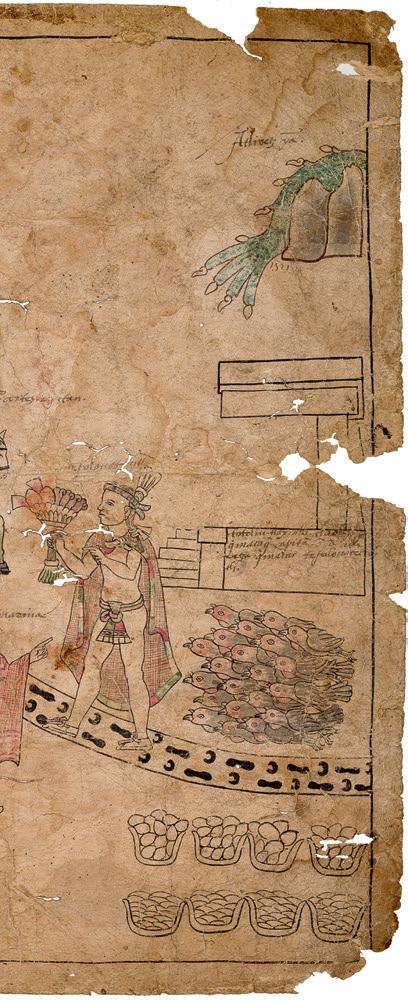

malinche → 194

manuel chavajay → 196

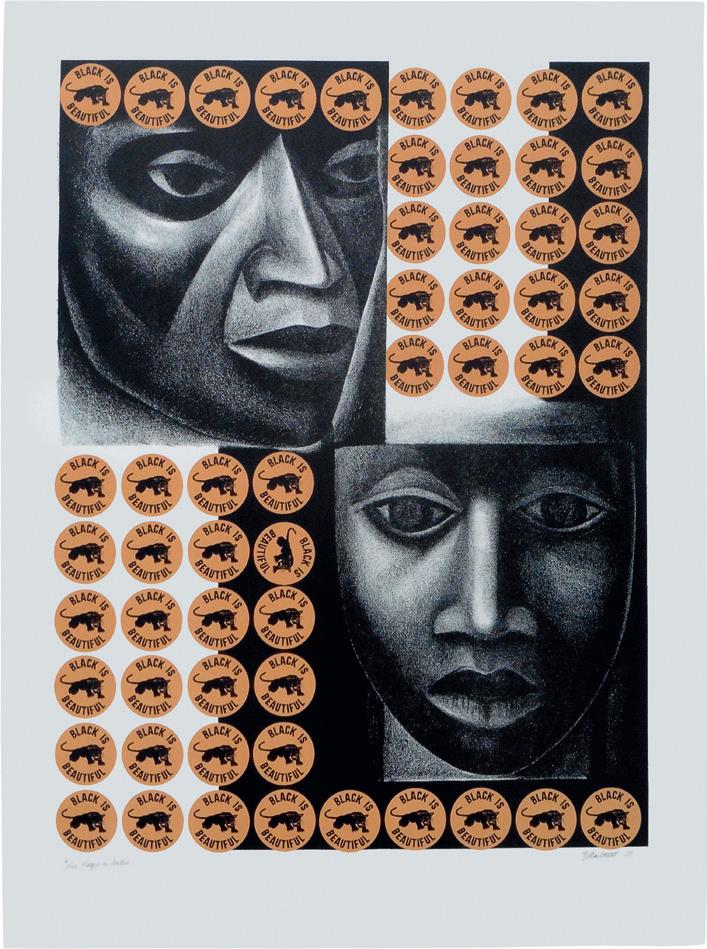

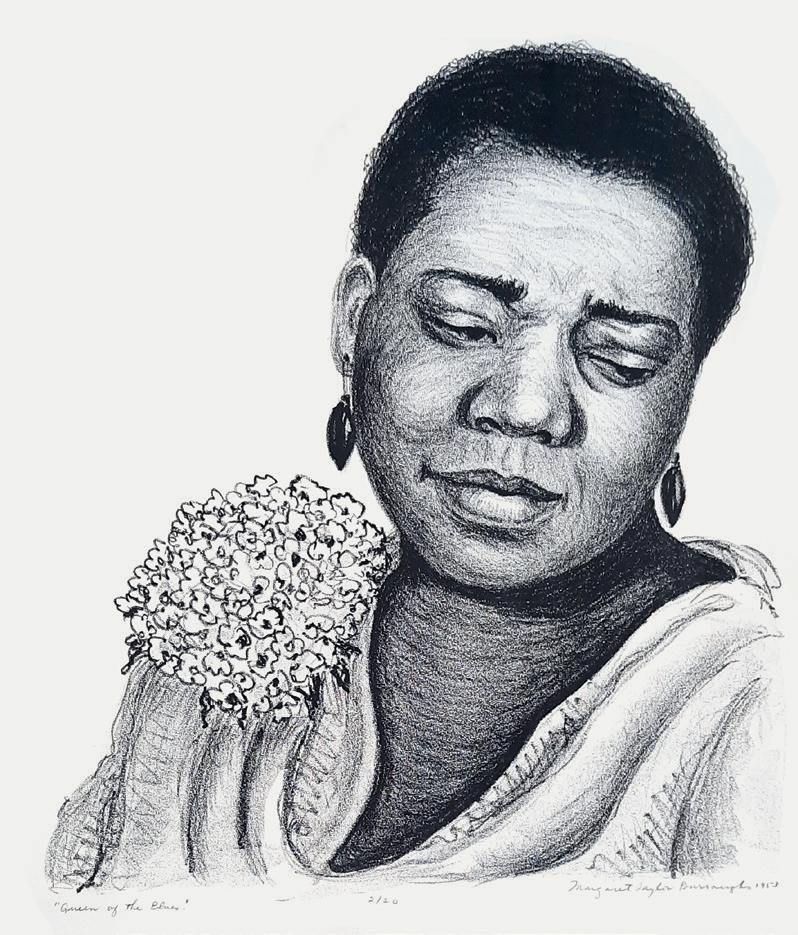

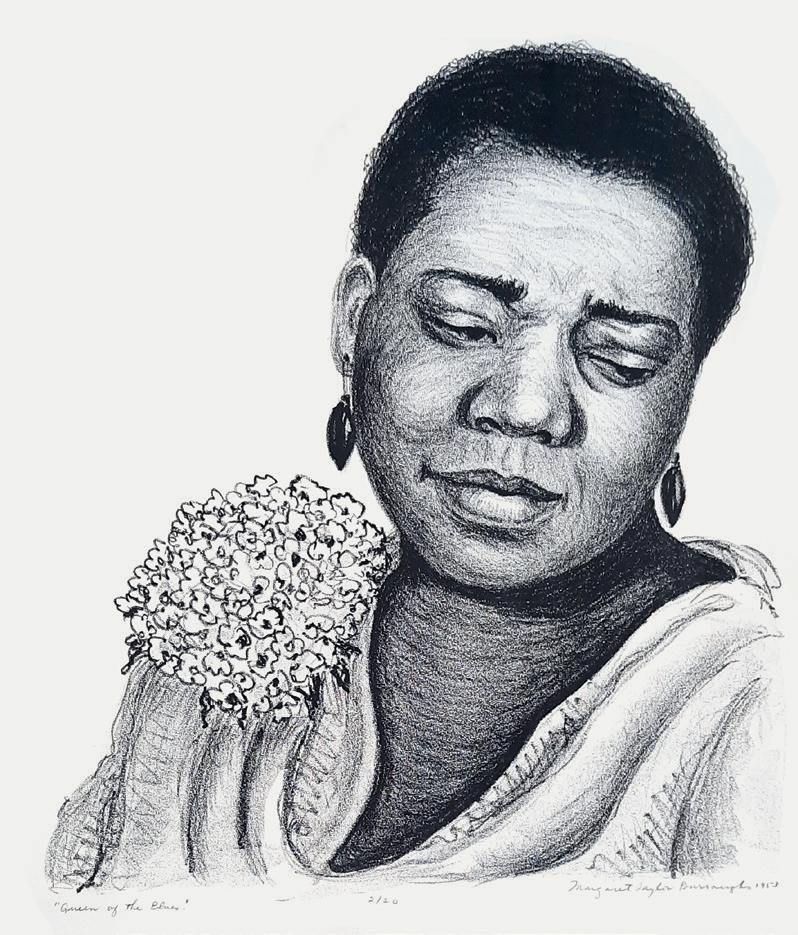

margaret taylor goss burroughs → 288

marilyn boror bor → 198

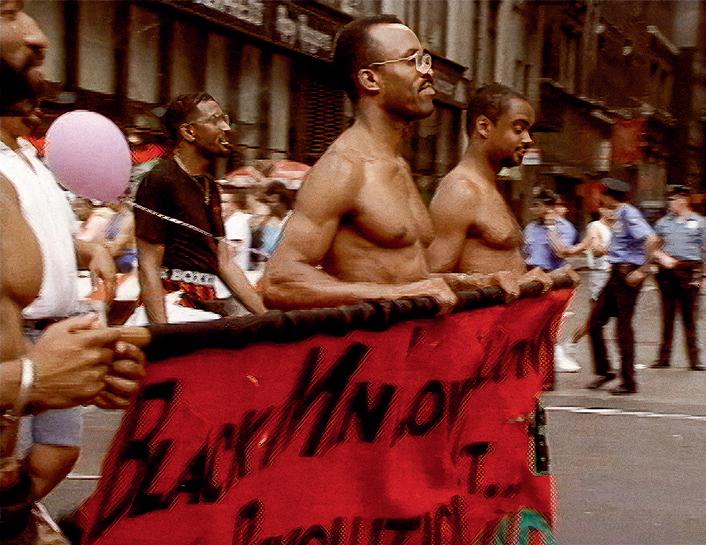

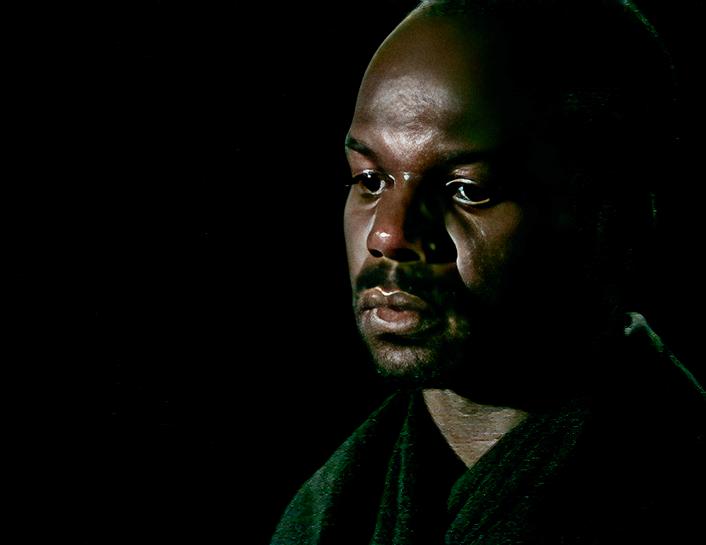

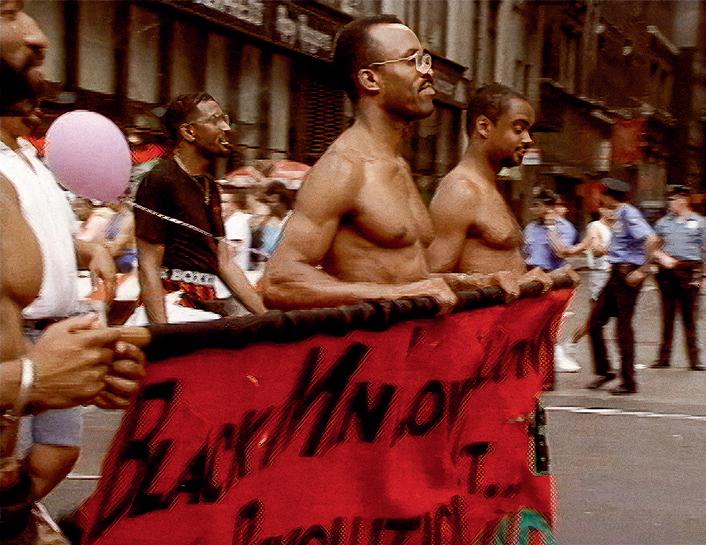

marlon riggs → 200

maya deren → 202

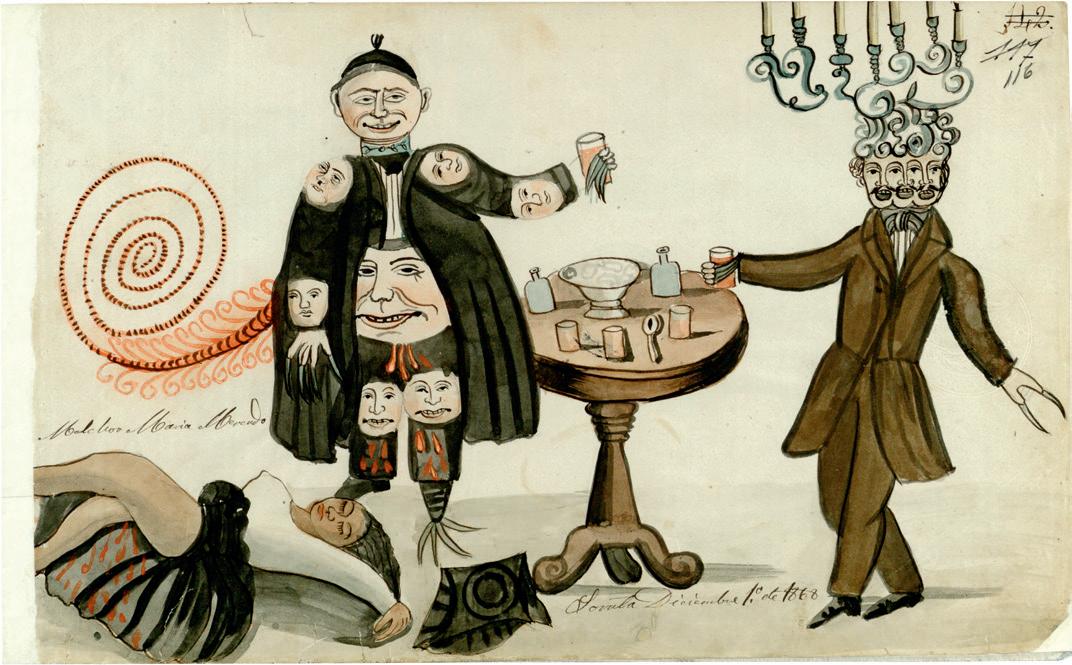

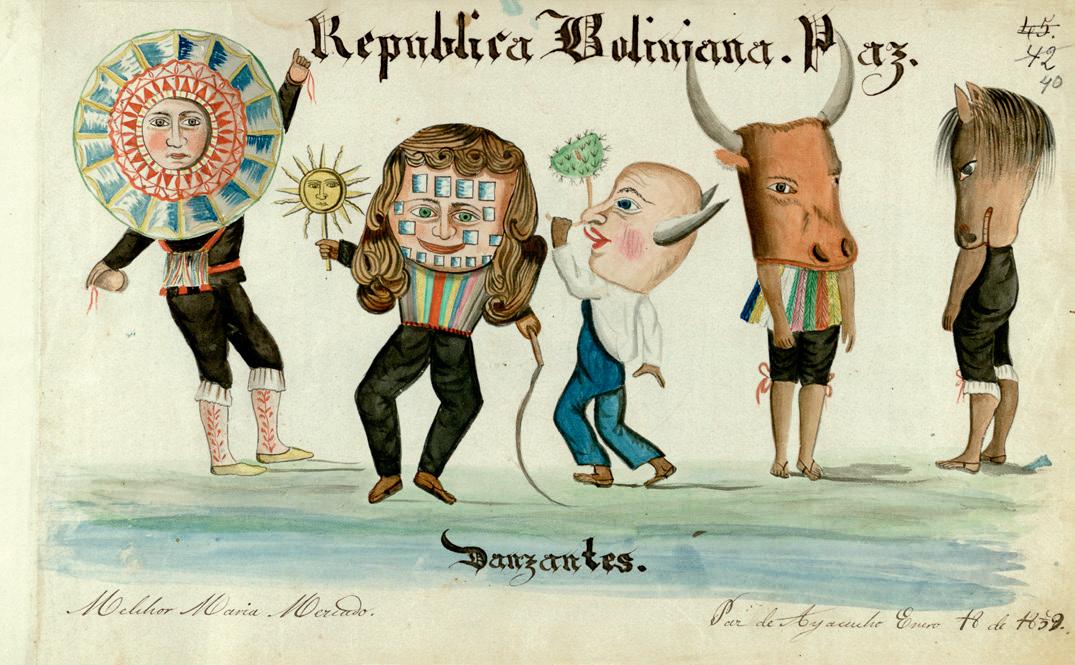

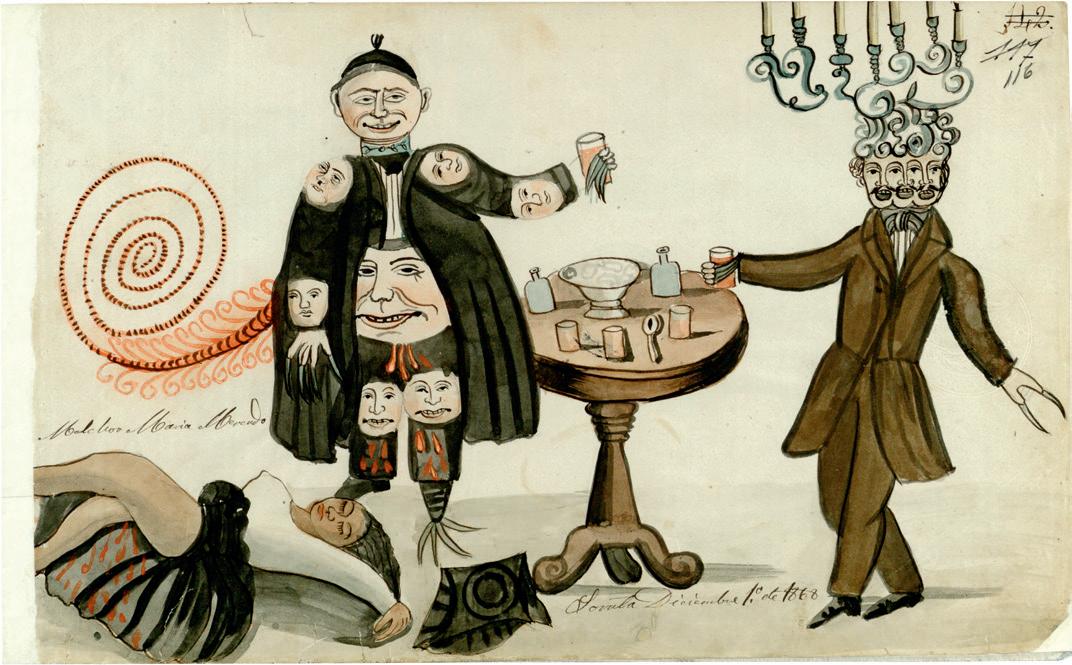

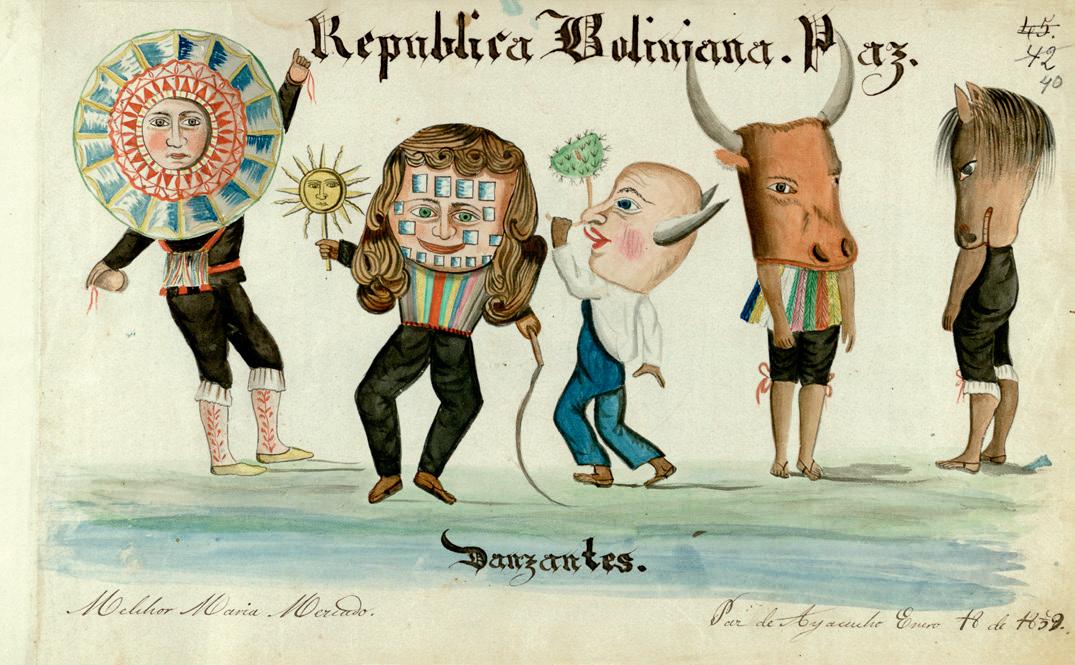

melchor maría mercado → 204

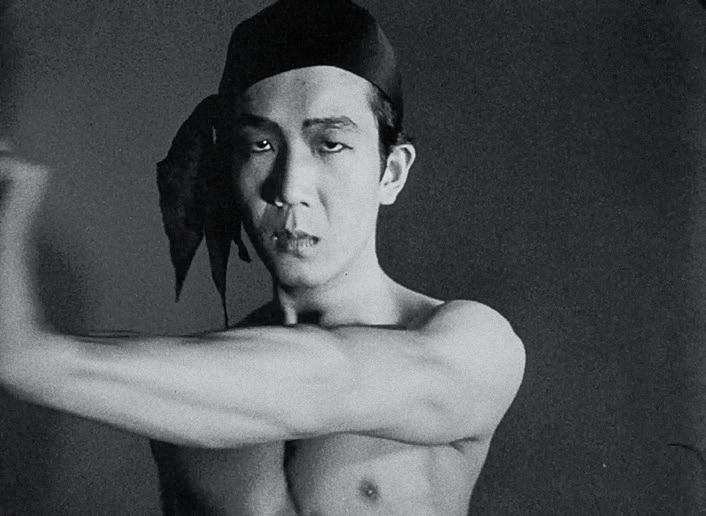

min tanaka and françois pain → 206

morzaniel ɨramari → 208

mounira al solh → 210

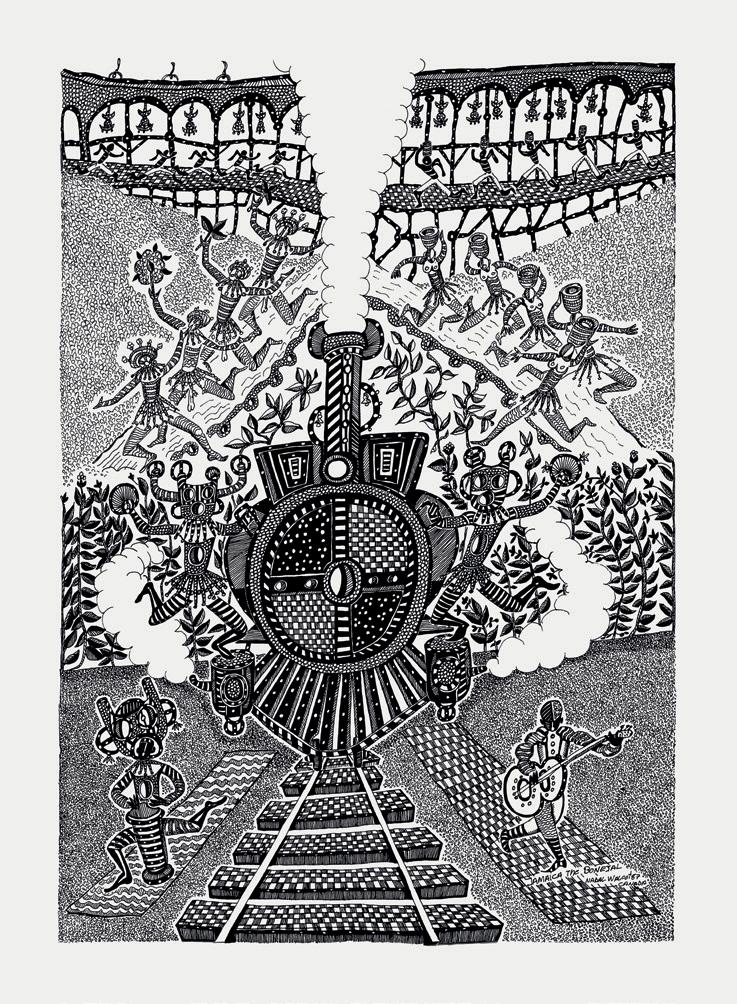

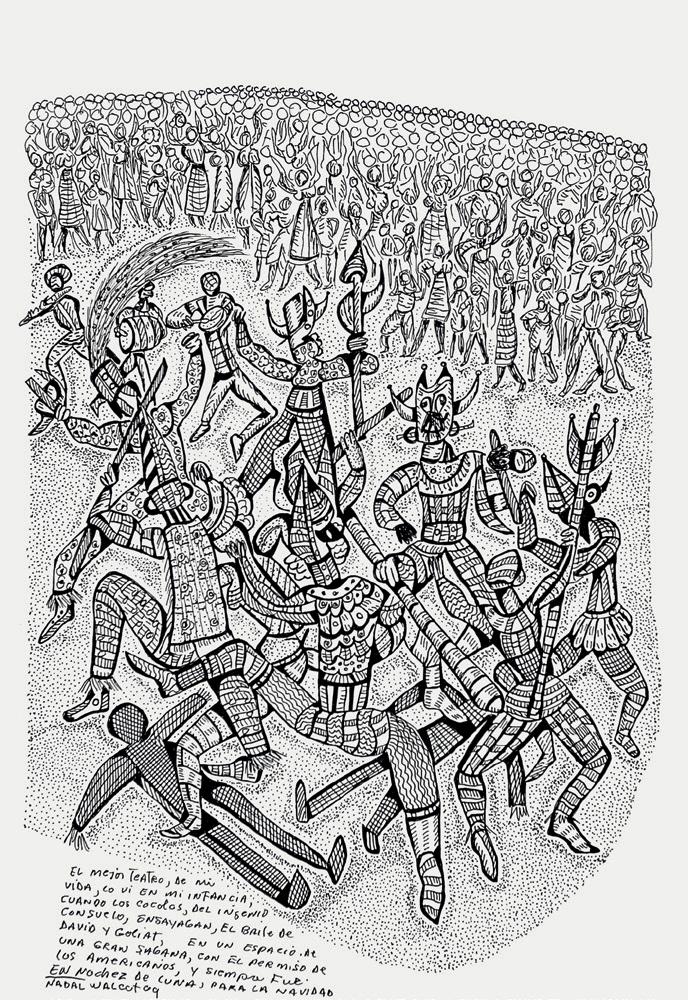

nadal walcot → 220

nadir bouhmouch and soumeya ait ahmed → 222 nikau hindin → 224

niño de elche → 226

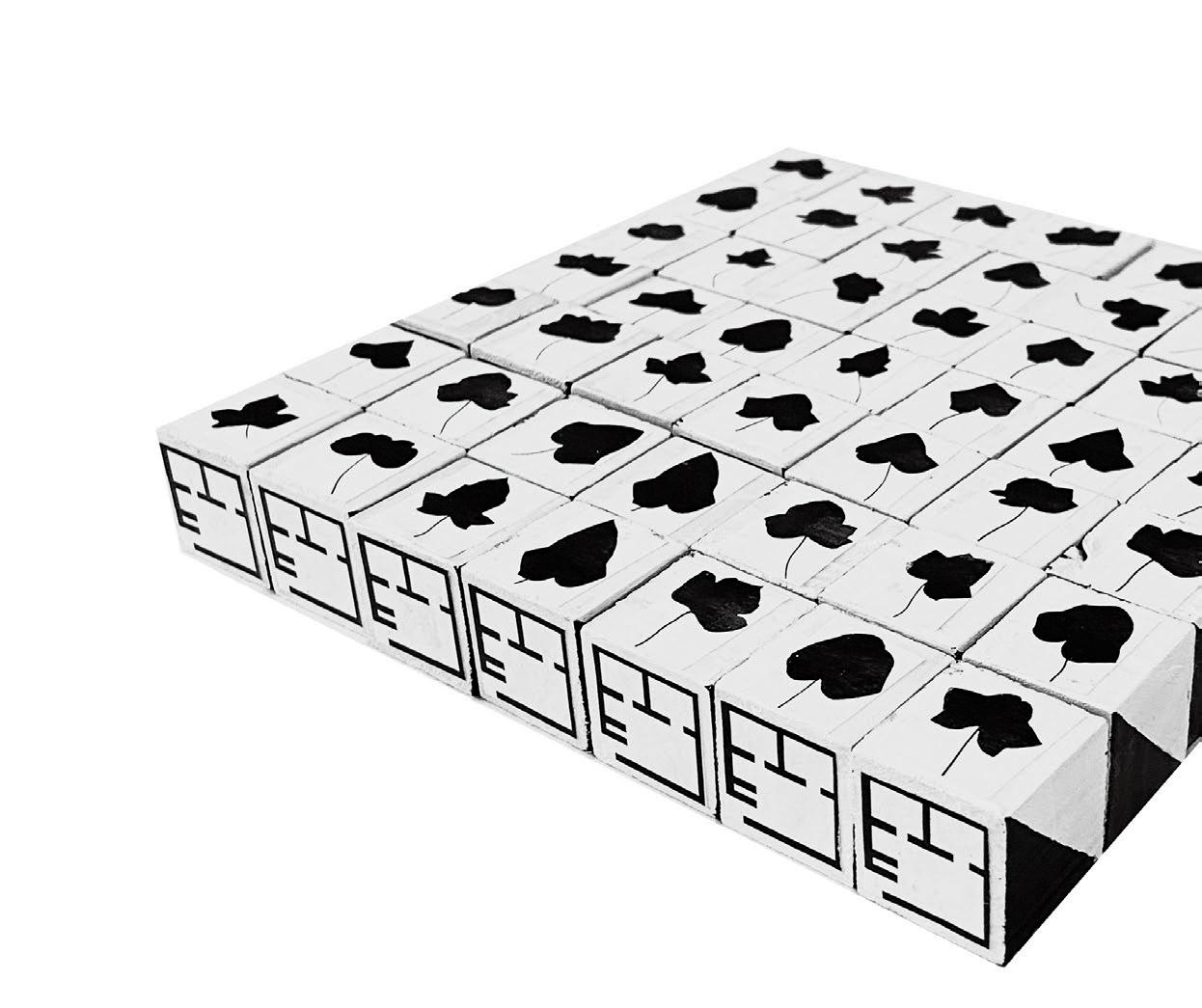

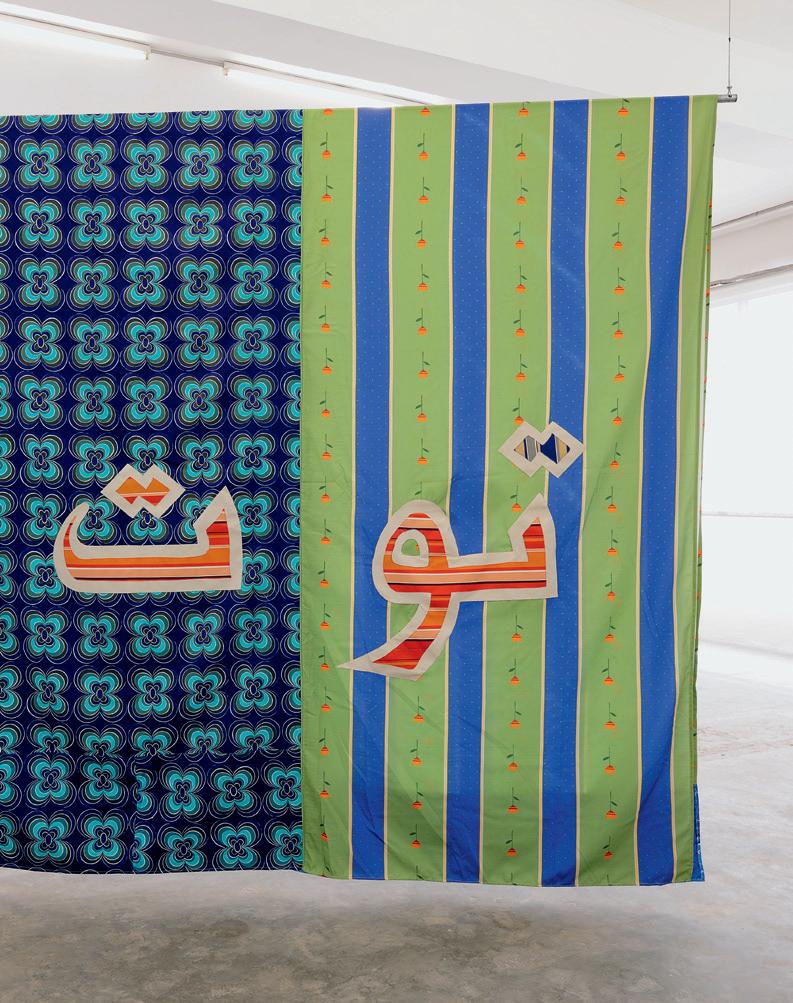

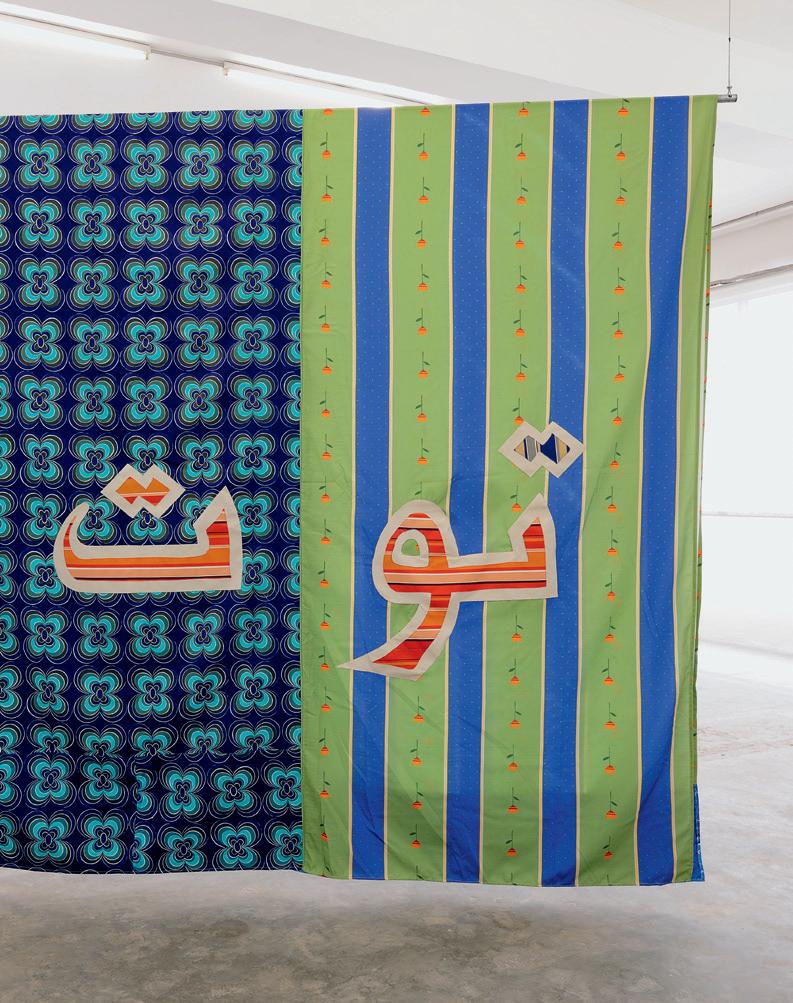

nontsikelelo mutiti → 228

patricia gómez and maría jesús gonzález → 230

pauline boudry / renate lorenz → 232

philip rizk → 234

raquel lima → 238

ricardo aleixo → 240

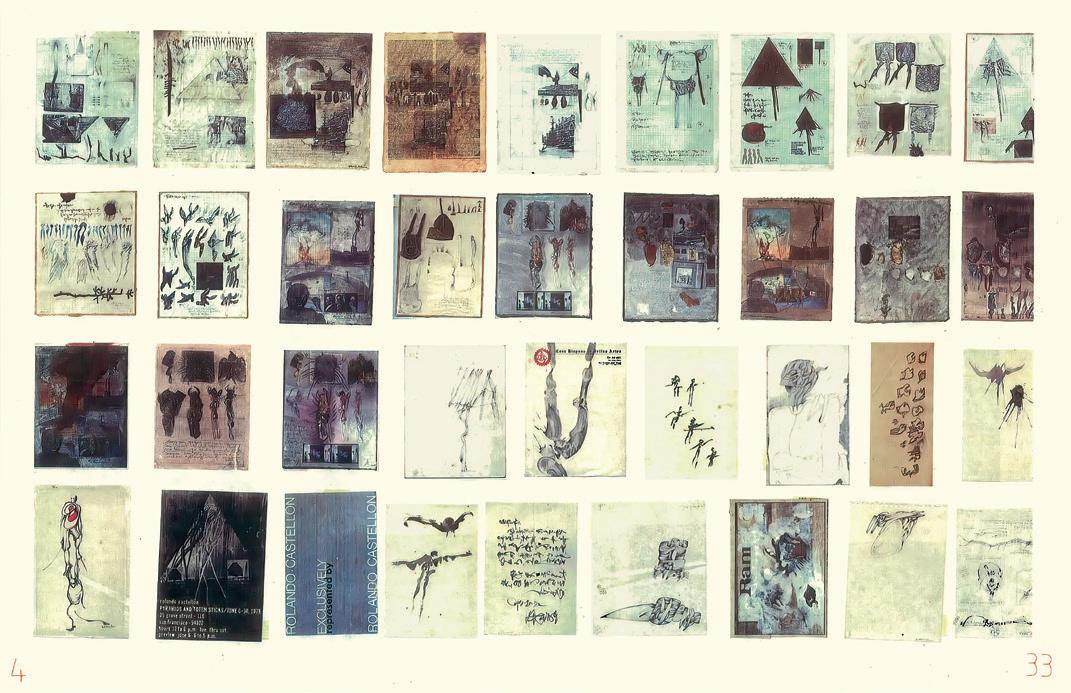

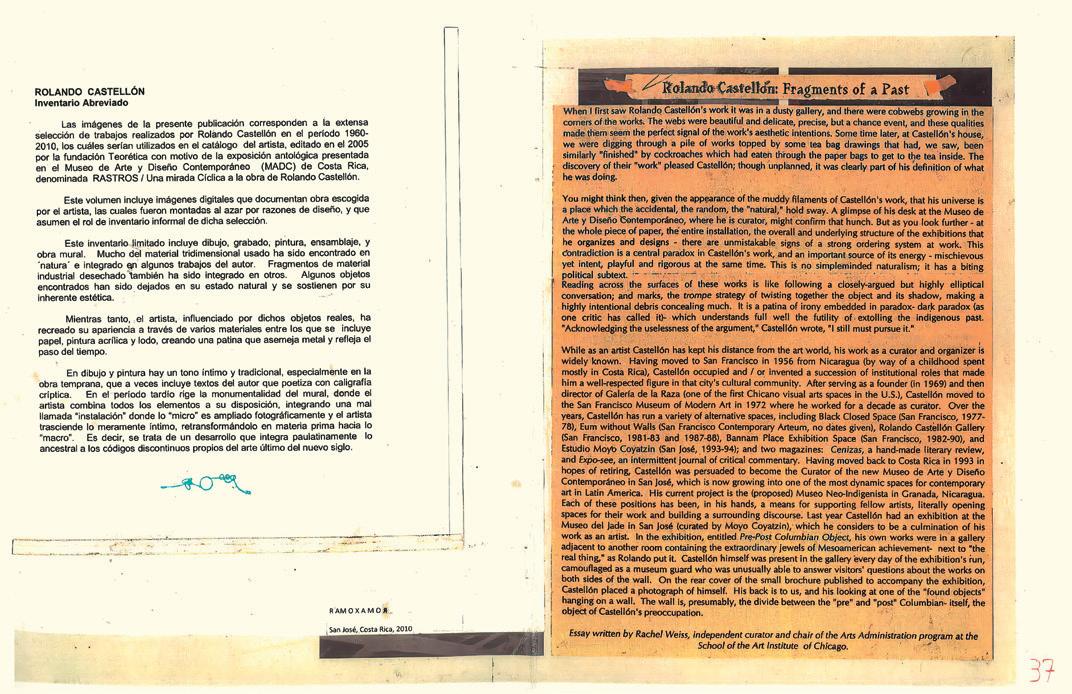

rolando castellón → 242

rommulo vieira conceição → 244

rosa gauditano → 246

rosana paulino → 248

rubem valentim → 250

quilombo cafundó → 236

rubiane maia → 252 sammy baloji → 260

santu mofokeng → 262

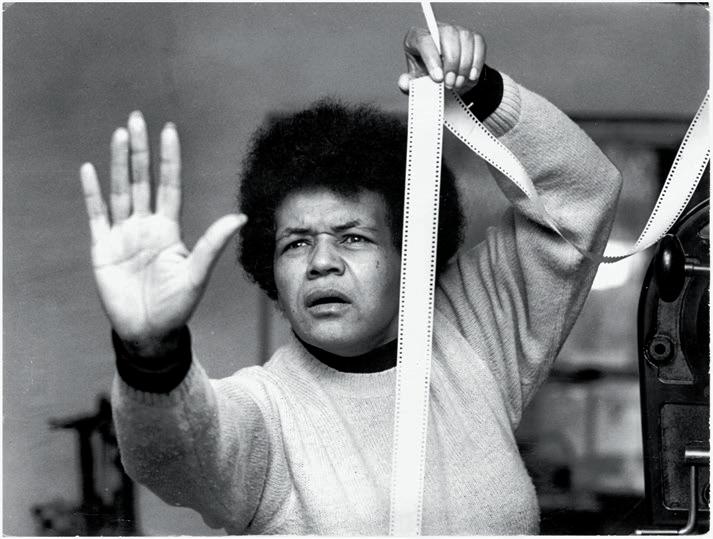

sarah maldoror → 264

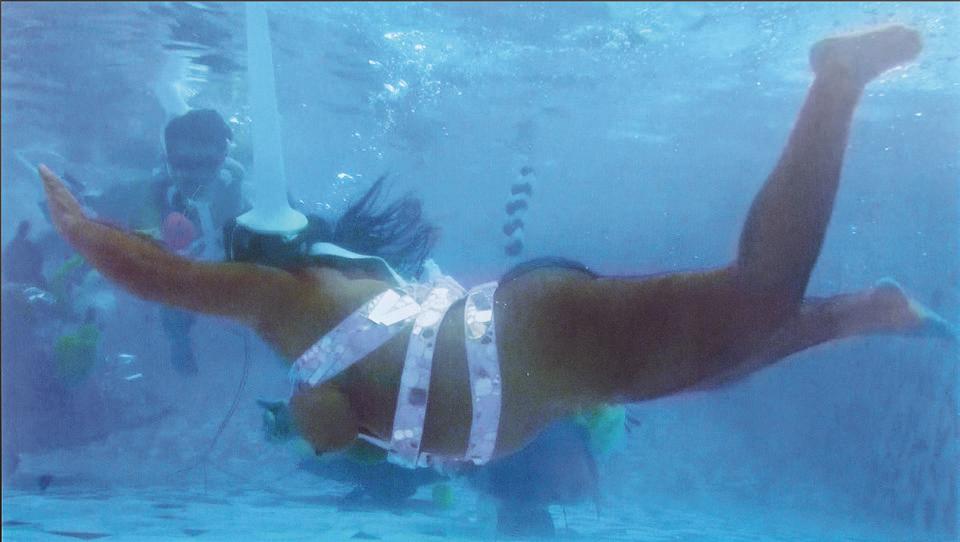

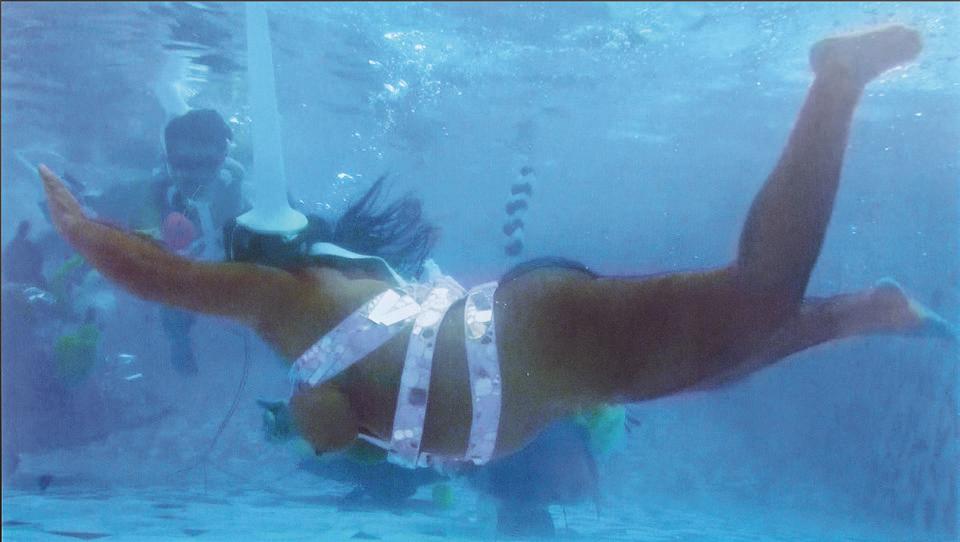

sauna lésbica by malu avelar with ana paula mathias, anna turra, bárbara esmenia and marta supernova → 266

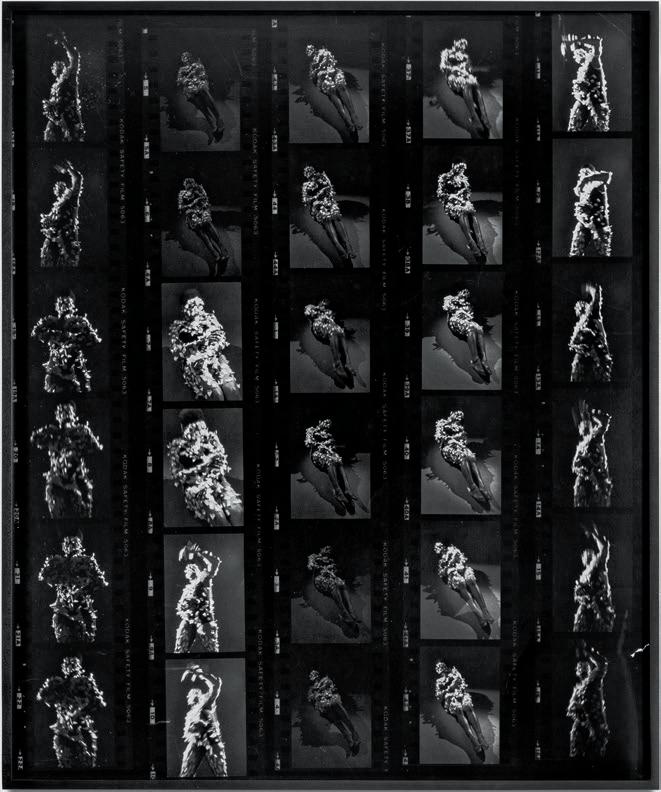

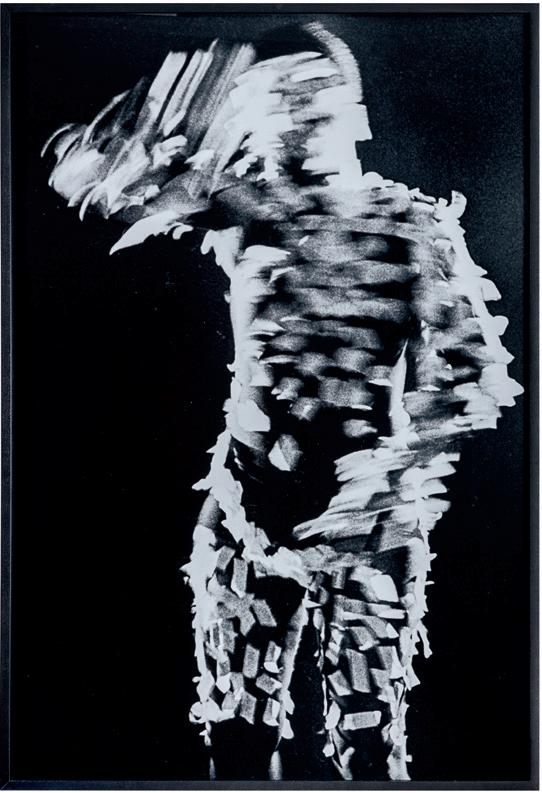

senga nengudi → 268 sidney amaral → 270

simone leigh and madeleine hunt-ehrlich → 272 sonia gomes → 274

stanley brouwn → 276

stella do patrocínio → 278

tadáskía → 280

taller 4 rojo → 282

taller de gráfica popular → 284

taller nn → 290

tejal shah → 292

the living and the dead ensemble → 294

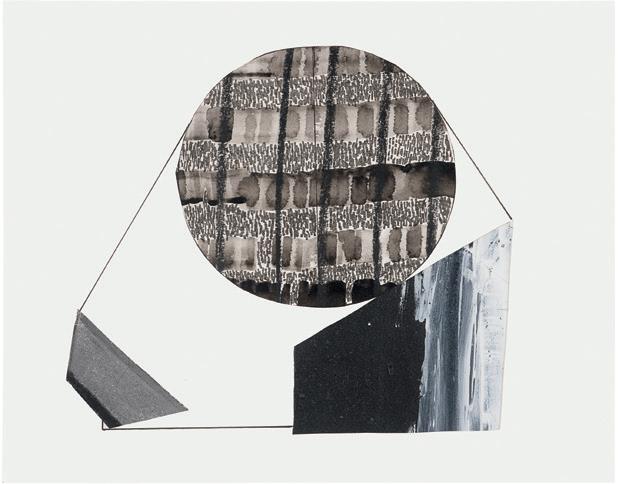

torkwase dyson → 296

trinh t. minh-ha → 298

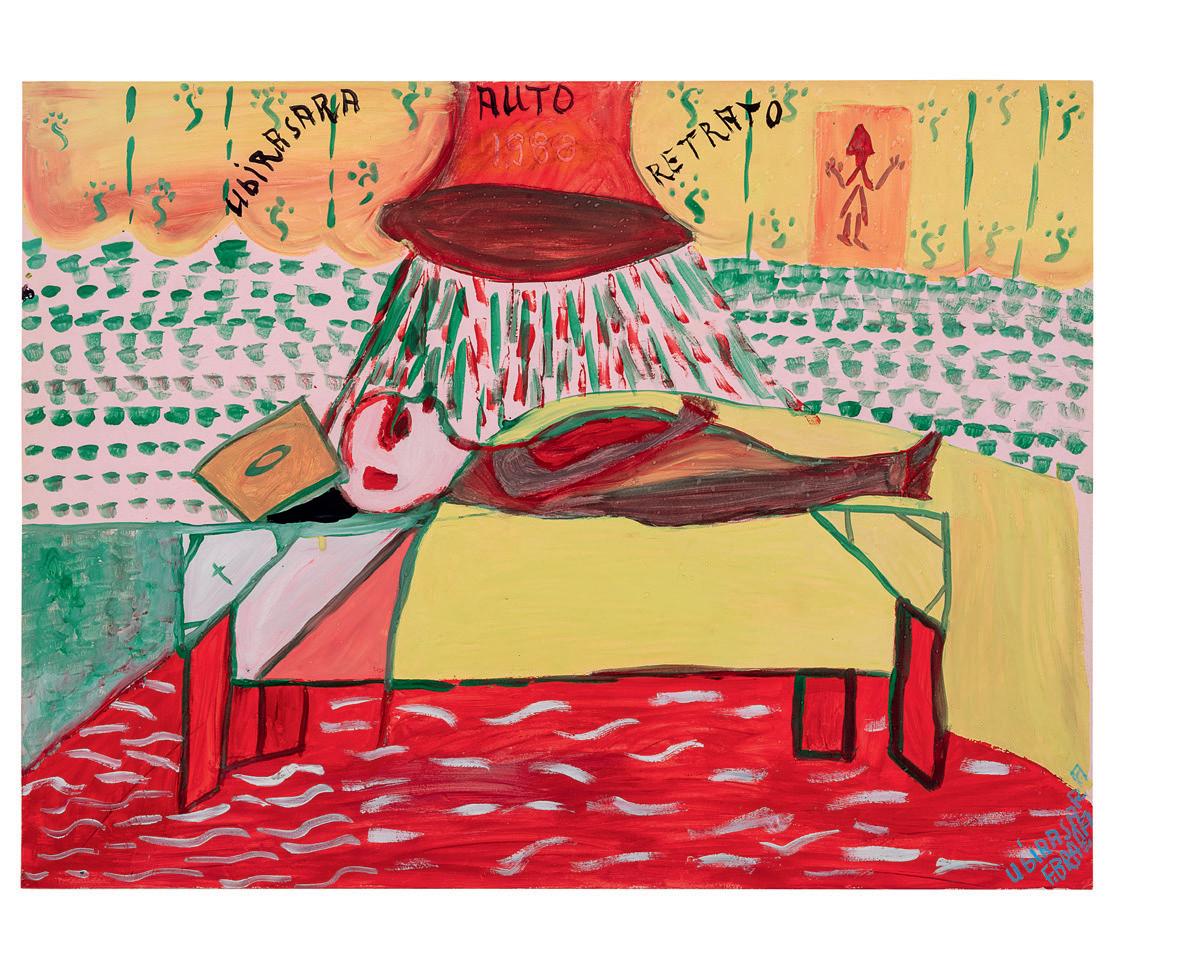

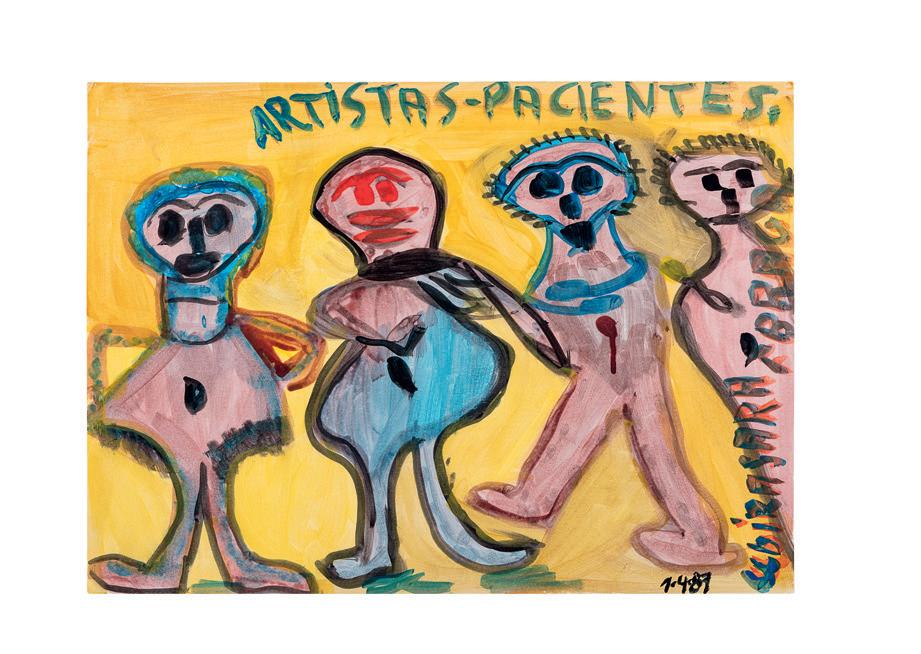

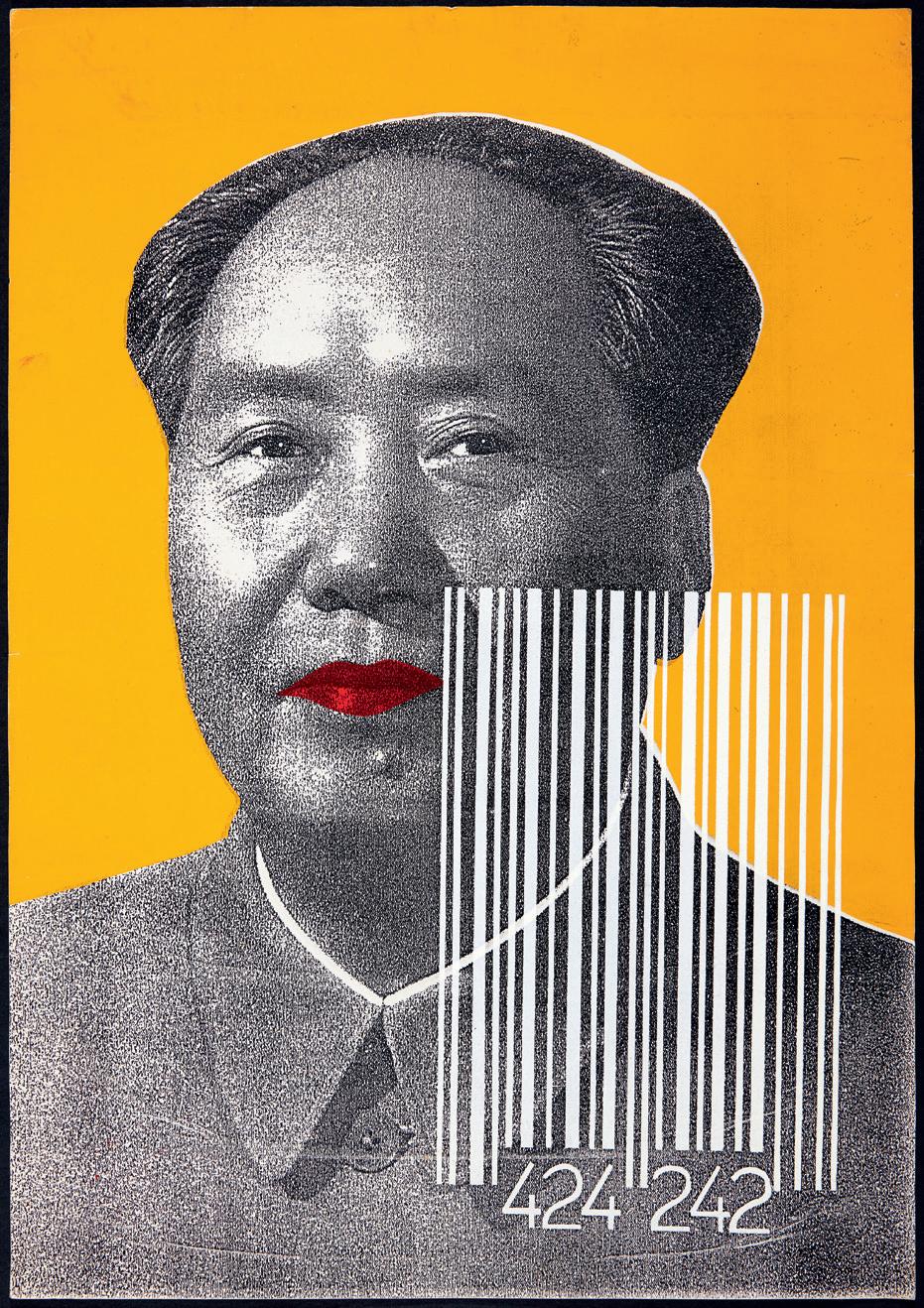

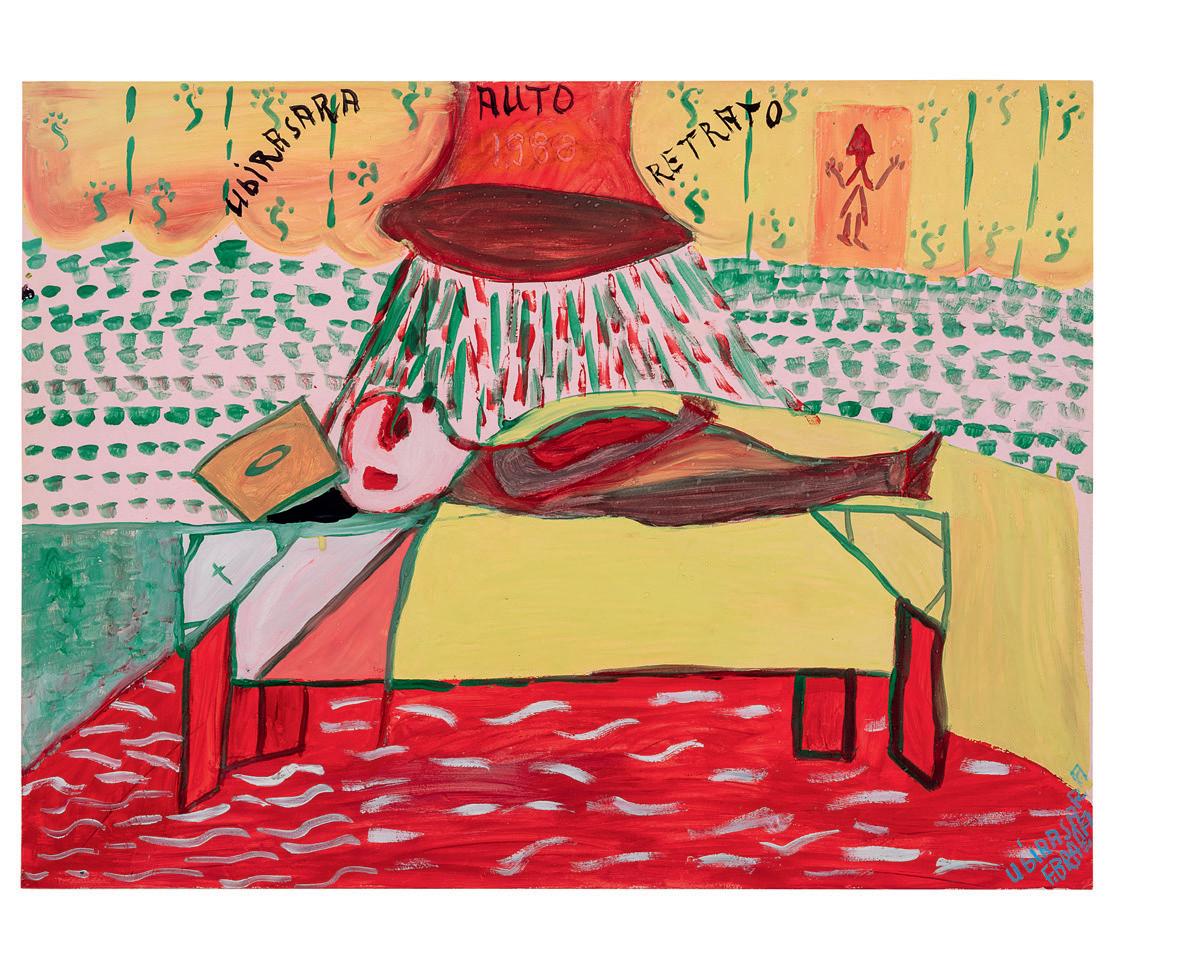

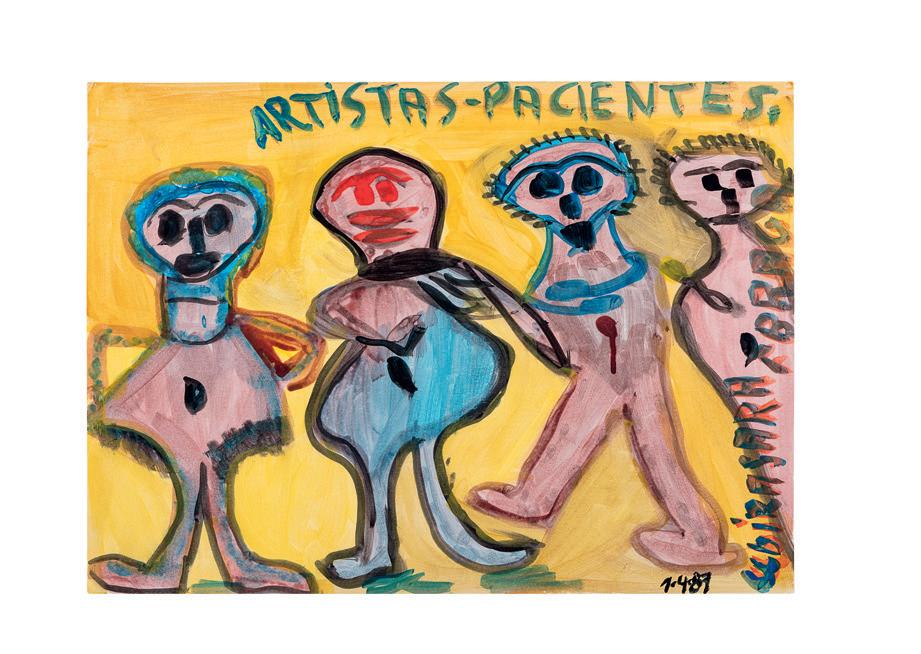

ubirajara ferreira braga → 300

ventura profana → 302

xica manicongo → 308

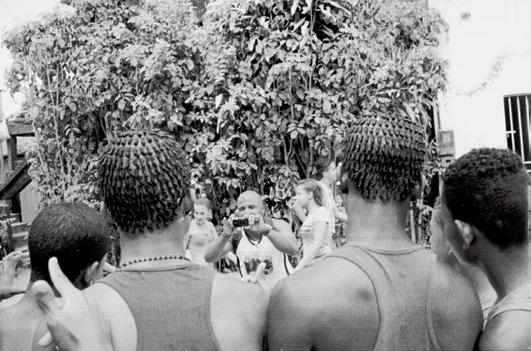

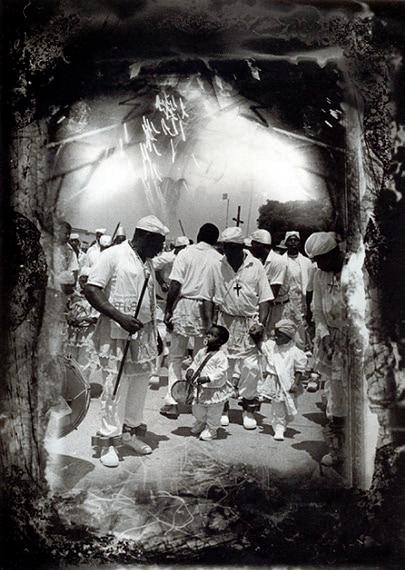

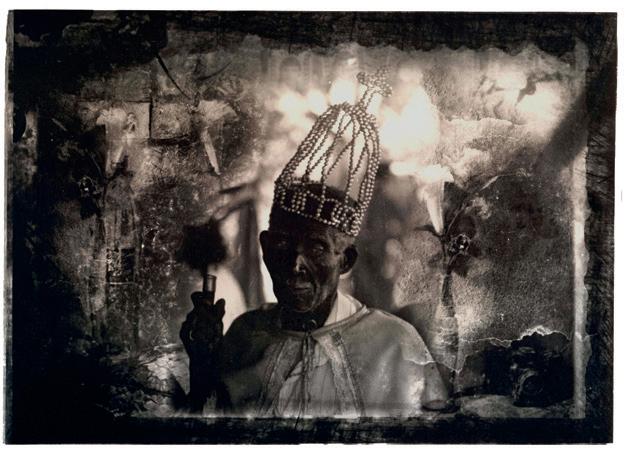

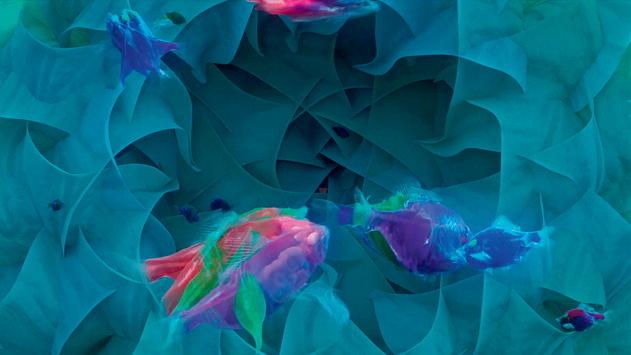

zumví arquivo afro fotográfico → 312

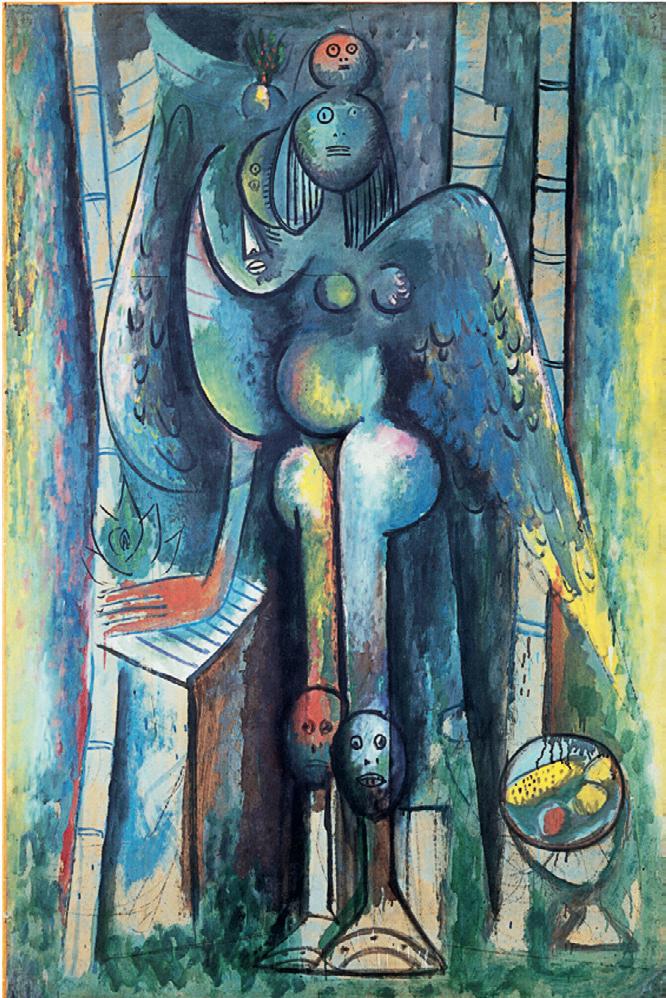

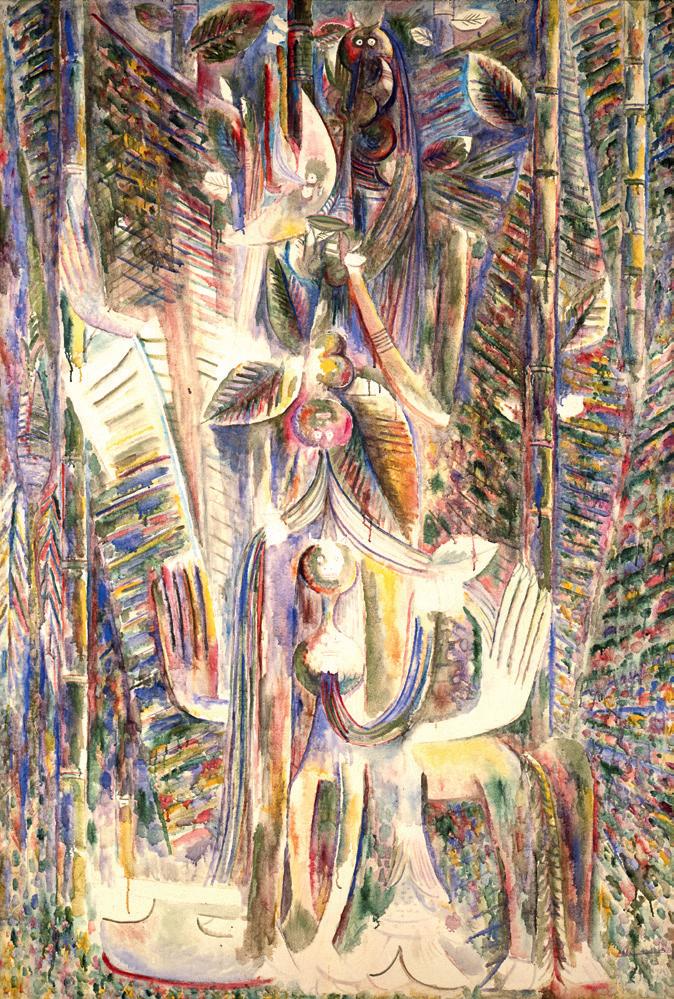

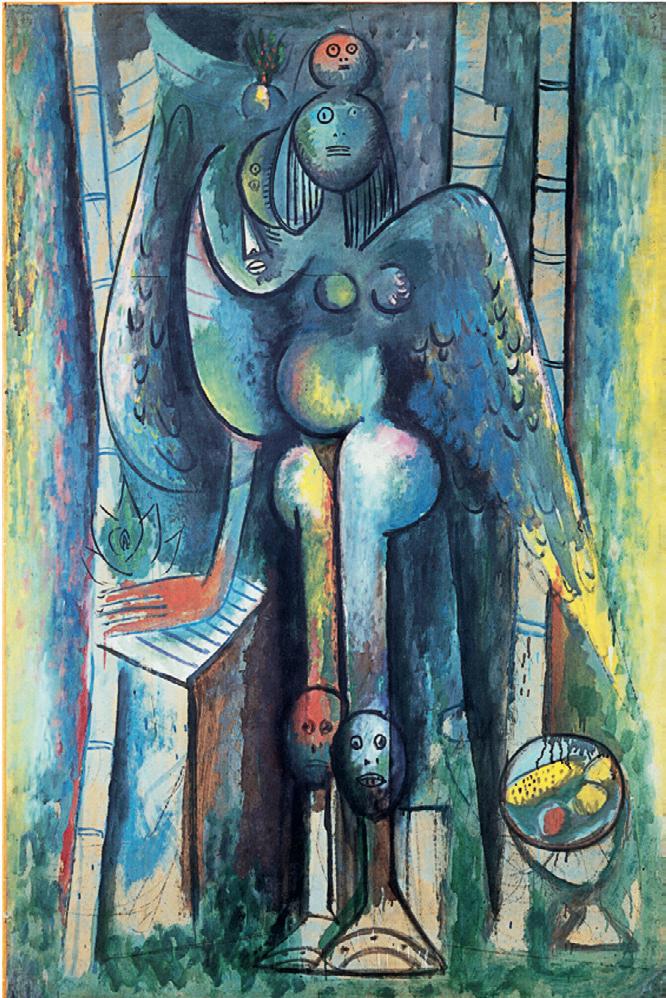

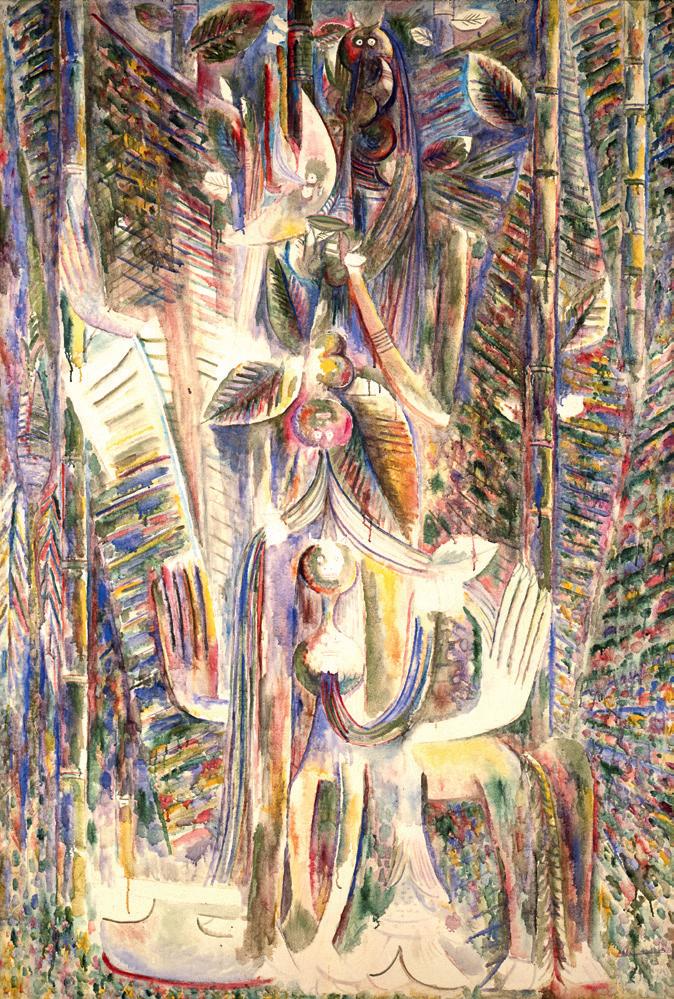

wifredo lam → 304 will rawls → 306

yto barrada → 310

grada kilomba → 12

hélio menezes → 14

manuel borja-villel → 20

diane lima → 28

hagar kotef → 42

gladys tzul tzul → 96

rizvana bradley and denise ferreira da silva → 148

tiganá santana → 212

ilenia caleo → 254

leda maria martins → 314

auá mendes

juliana dos santos

mario lopes

natali mamani

queen gloria "mama g" simms

xadalu tupã jekupé

ëntun fey azkin (mapuche territory) nls / new local space (jamaica) sertão negro (brazil)

artist's residency

essays

networks

abigail campos leal

ana longoni

barbara copque

beatriz martínez hijazo

carles guerra

cíntia guedes

claudinei roberto

david pérez

déba tacana

emanuel monteiro

fernanda carvajal

getsemaní guevara

heitor augusto

horrana de kássia santos

igor de albuquerque

isabel tejeda

josé antonio sánchez

juliana de arruda sampaio

kaira cabañas

kênia freitas

kike españa

luciana brito

luciane ramos silva

marco baravalle

maria luiza meneses

mario gooden

miro spinelli

natalia arcos salvo

nicole smythe-johnson

oluremi onabanjo

omar berrada

pérola mathias

phillipe cyroulnik

rafael garcía

renato menezes

rocío robles tardío

rossina cazali

sara ramos

sol henaro

sylvia monasterios

tarcisio almeida

tatiana nascimento

thiago de paula souza

josé olympio da veiga pereira → 336

margareth menezes → 337

itaú cultural → 338

instituto cultural vale → 338

bloomberg → 339

sesc são paulo → 339

biographies → 330

credits → 340

acknowledgements → 344

partners → 346

image credits → 348

publication credits → 352

collaborations institutional letters +

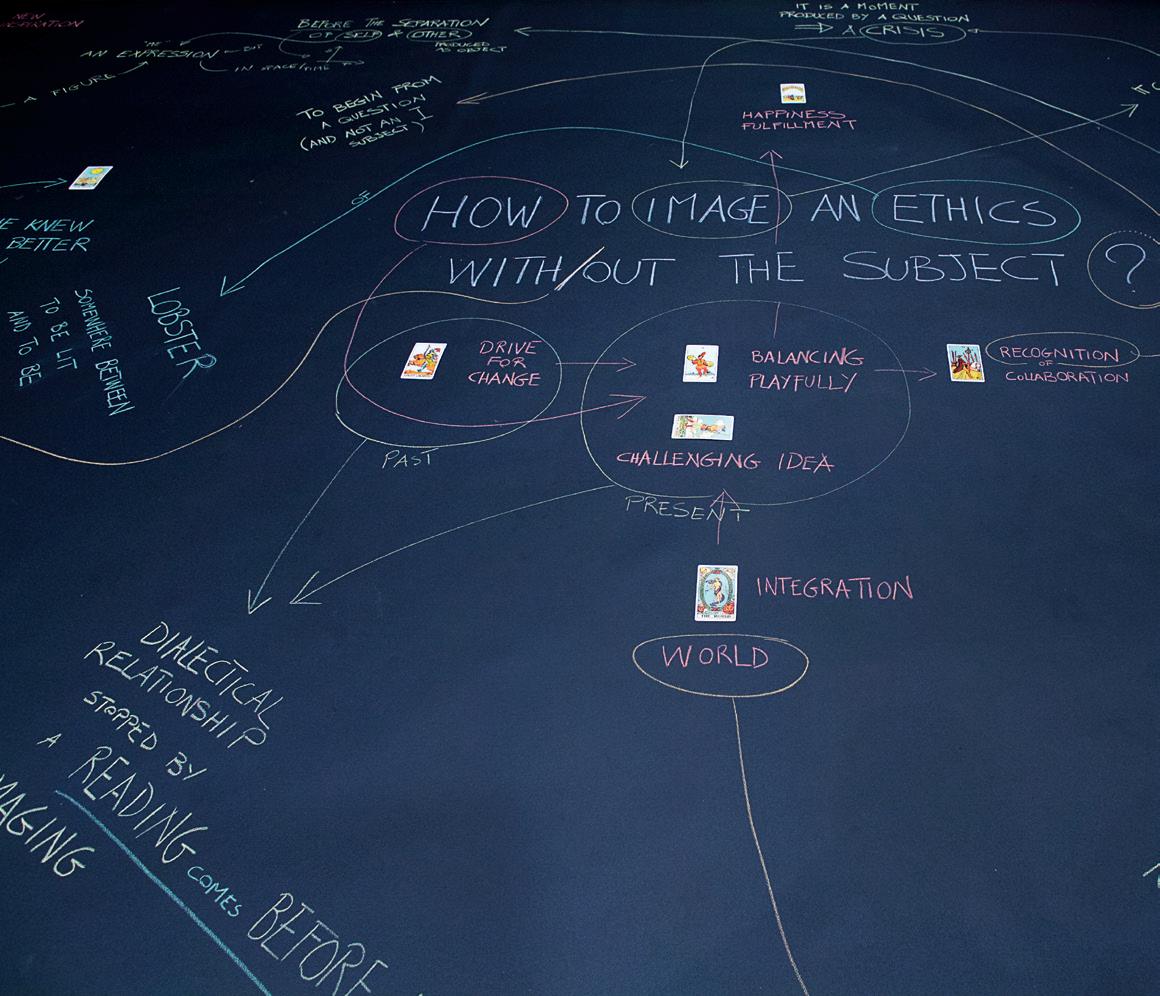

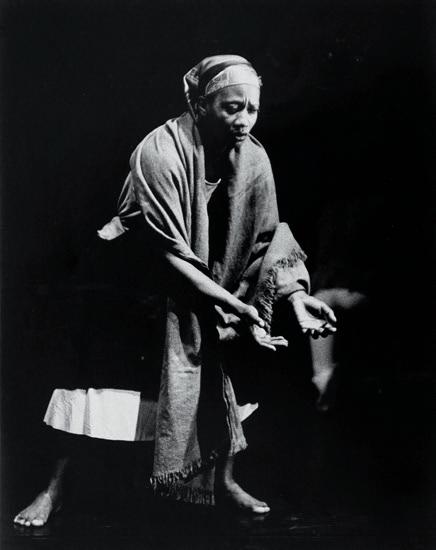

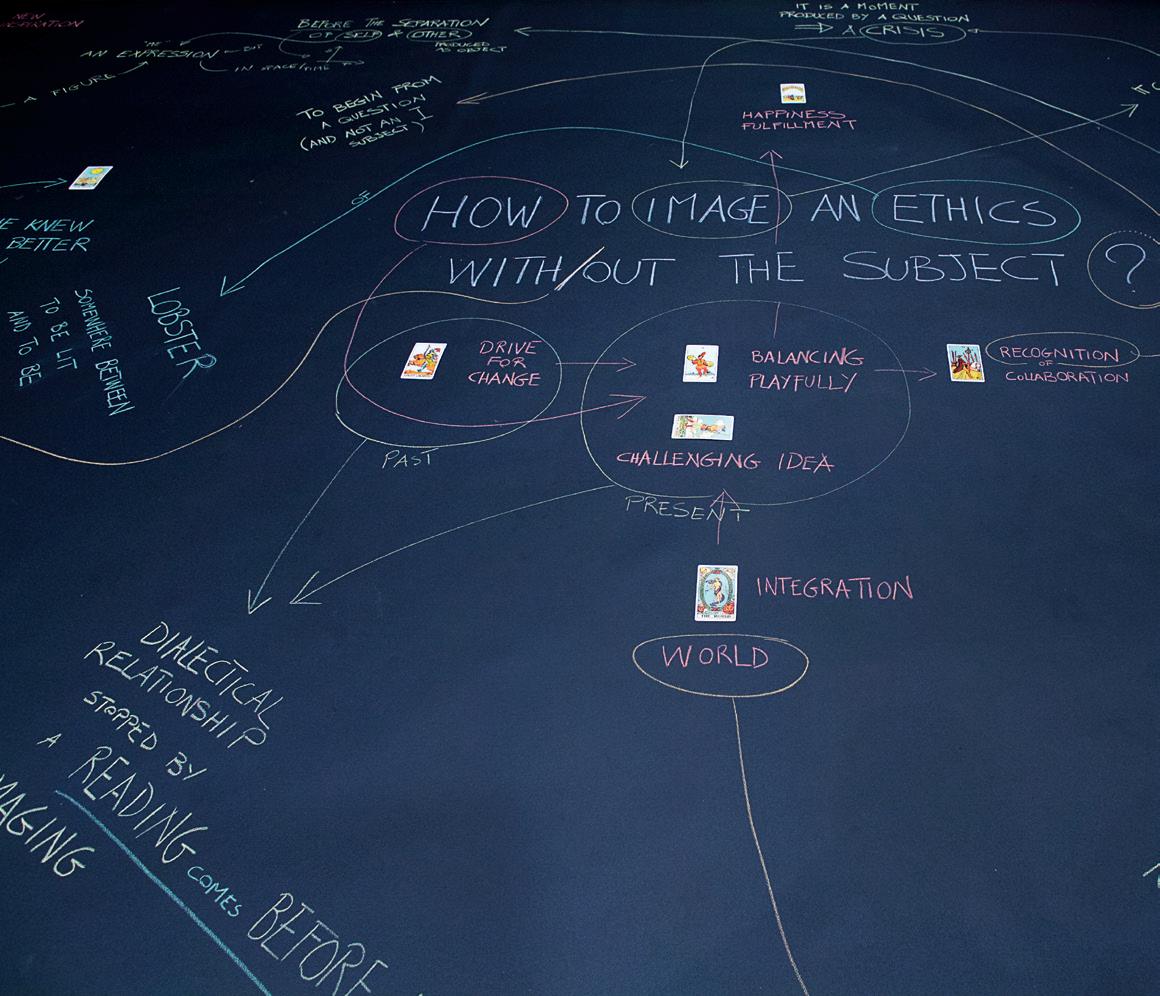

choreographies of the impossible takes shape from a conceptual exercise that is reflected in our own curatorial training and practice. We came together to create a horizontal group, without the hierarchy of a chief curator or the homogeneity of a collective. It is a way of choreographing that considers our different backgrounds, education, areas of activity and, above all, seeks to create strategies that allow us to face the institutional and curatorial challenges inherent to a project of this magnitude.

Broadening collaborative processes and our perspectives was what motivated us to conceive a set of dialogues, ranging from the list of participants and groups and spaces – which offered us examples of alternative management to current approaches – to researchers and learning practices not necessarily linked to conventional fields of knowledge. There was also a lot of dialogue with the pair of curatorial assistants, composed of Sylvia Monasterios and Tarcisio Almeida, and with the curatorial council, formed by Omar Berrada, Sandra Benites, Sol Henaro and Thomas Lax.

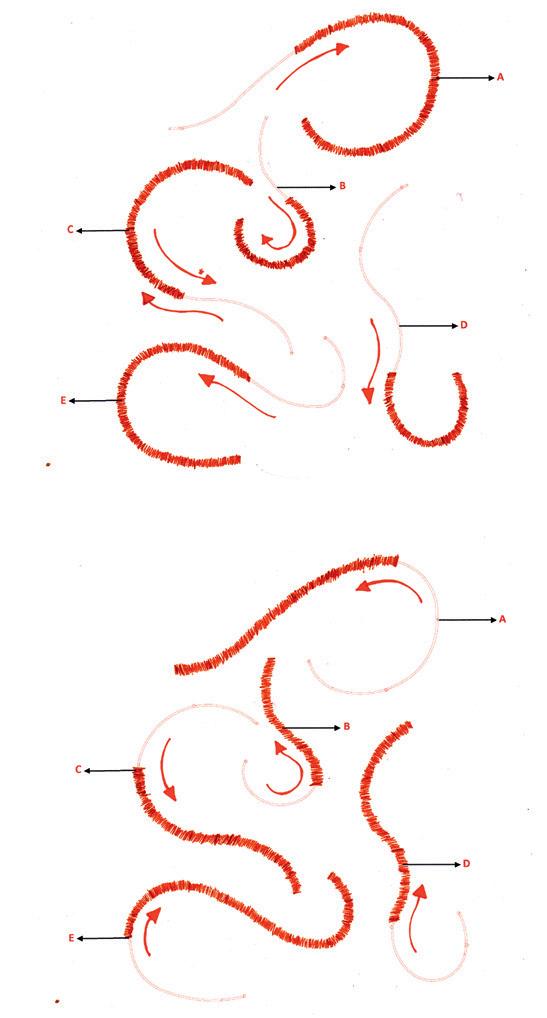

As we will see in the various texts that make up this catalog, this spiral principle radiates through the selection of works and all the other structures that organize a biennial, such as the architectural and exhibition design, the education and mediation program, as well as the invitation to read this material.

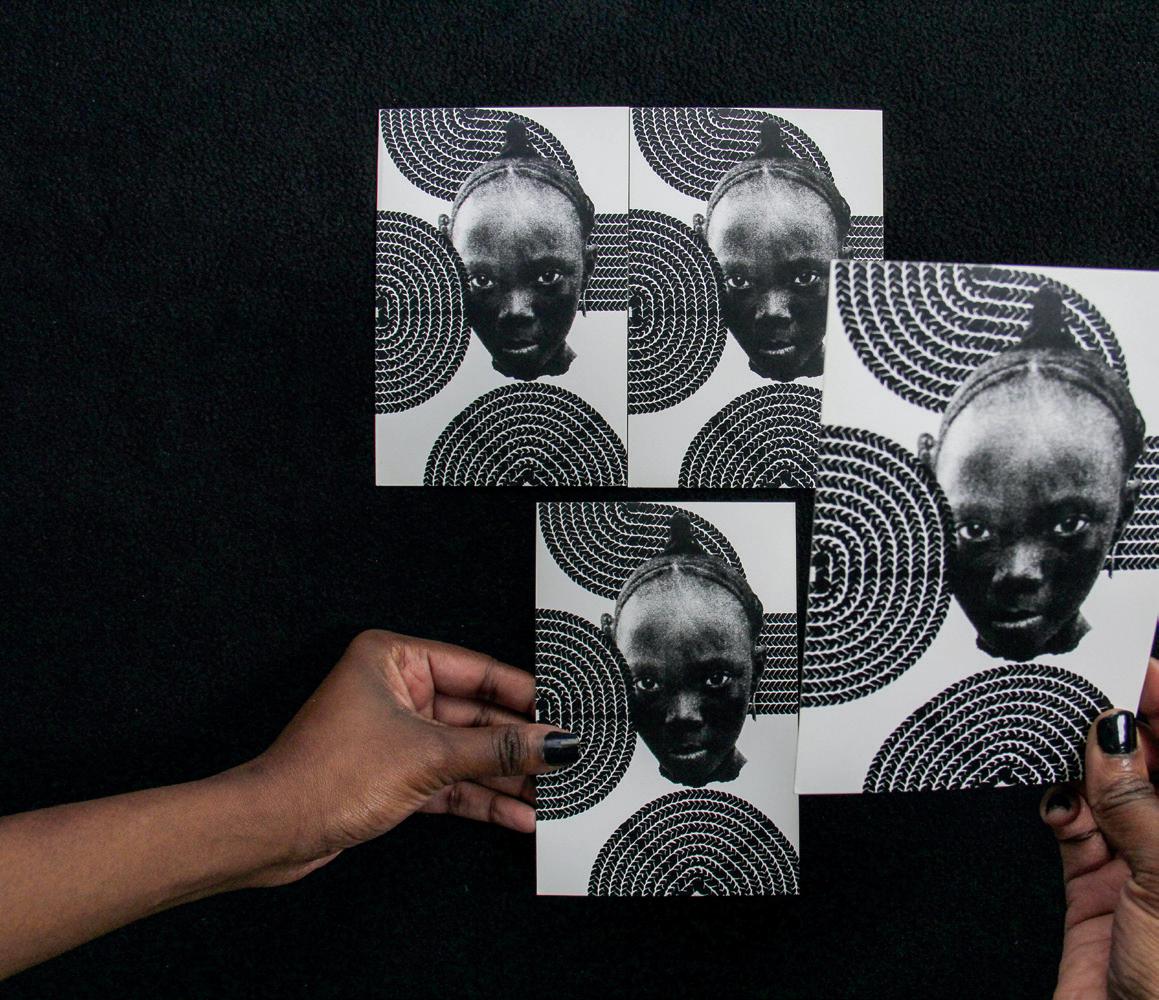

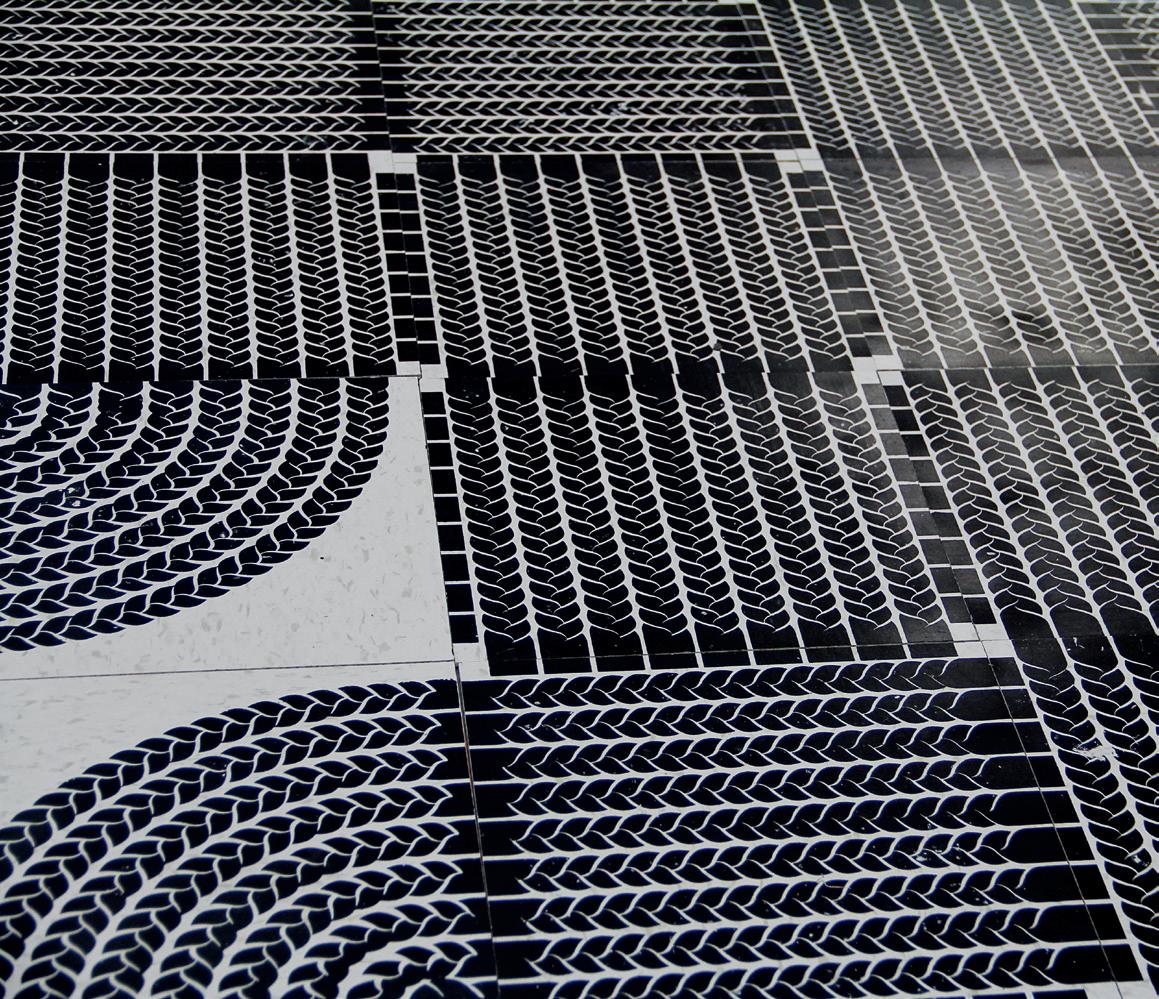

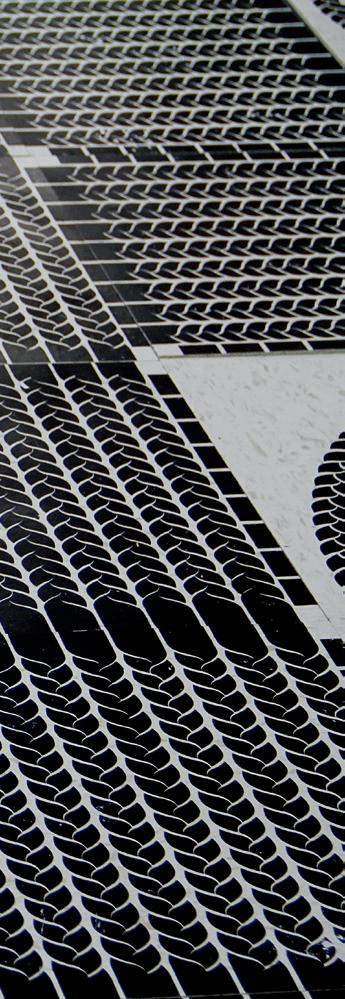

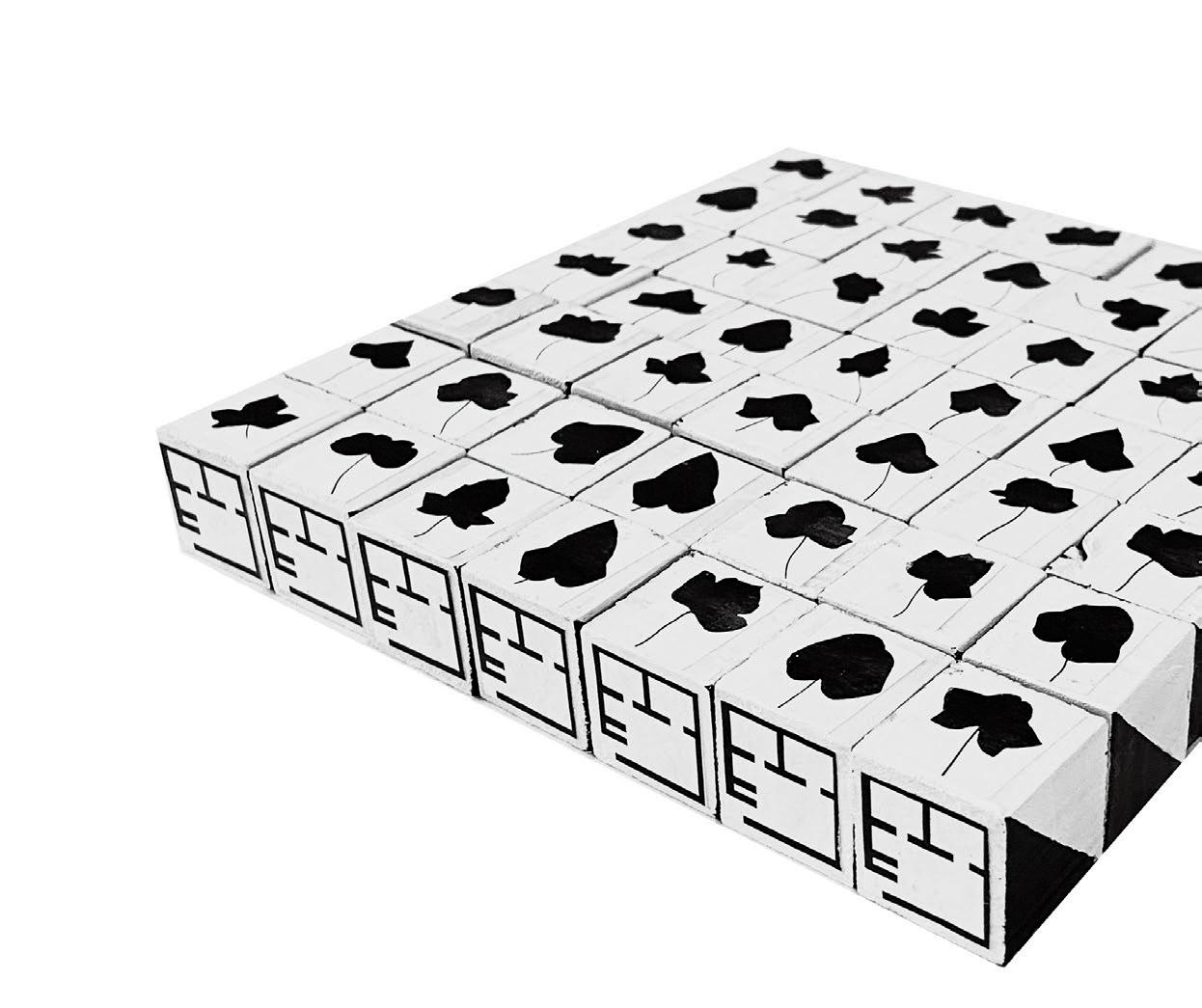

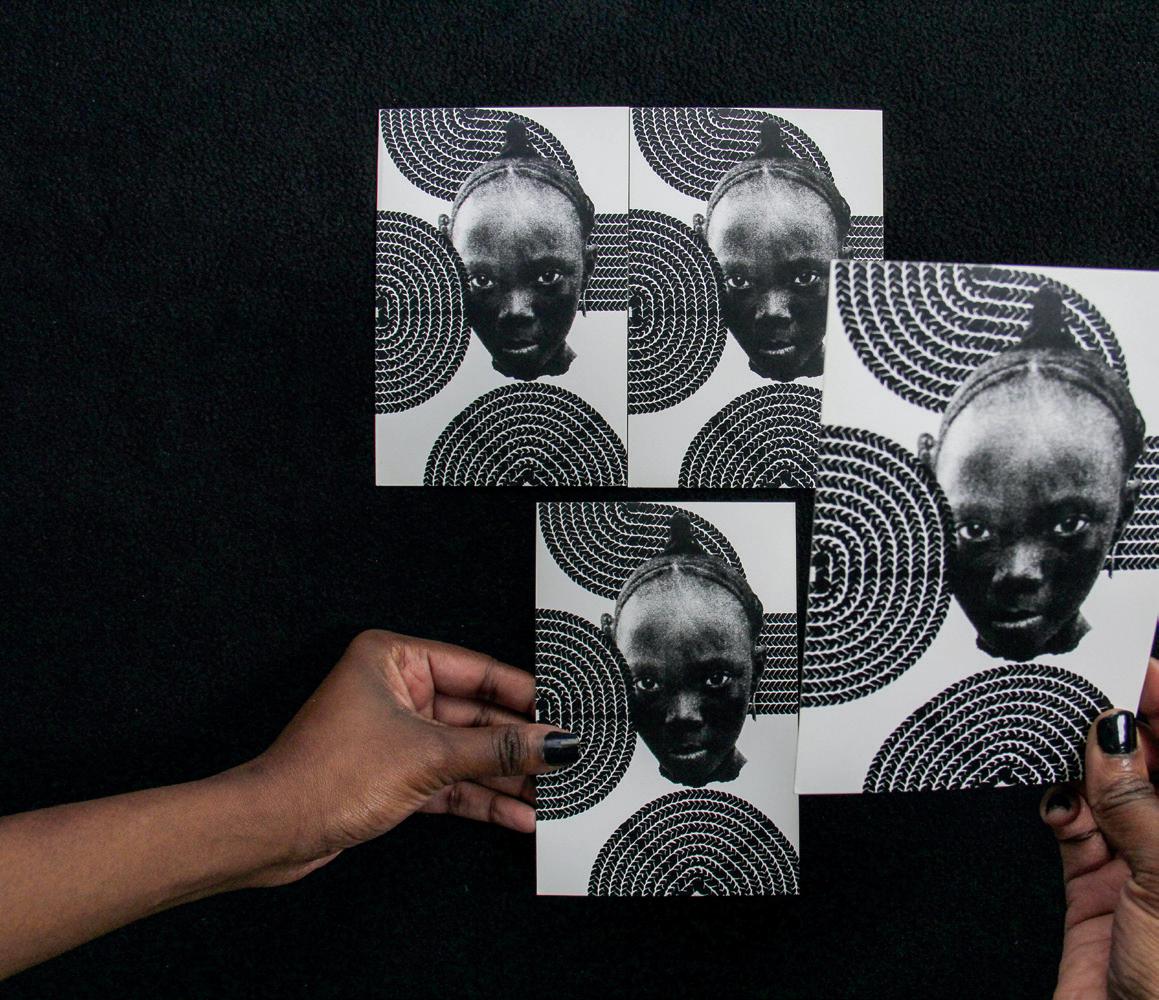

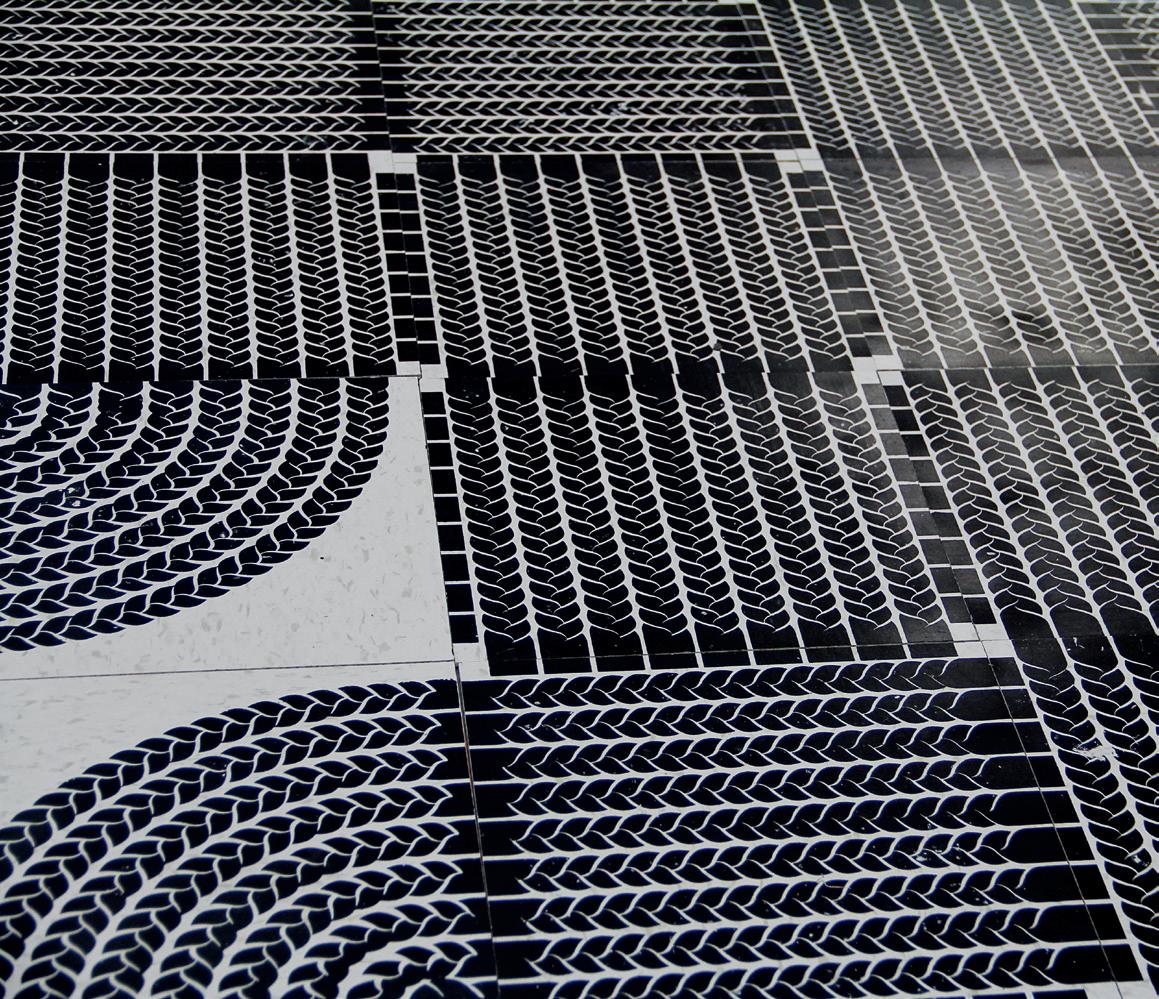

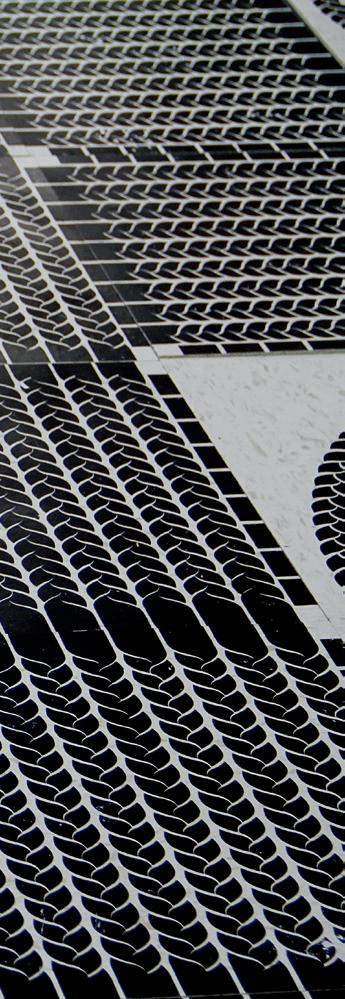

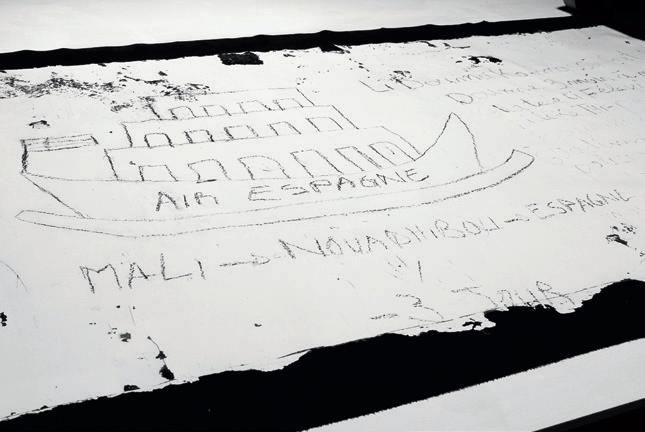

Conceived as a weave of voices, or a “braid” of worlds – as the artist and educator Nontsikelelo Mutiti, who created the visual identity of the 35th Bienal de São Paulo, urges us to think – this editorial project brings together a large group of authors who have accepted the challenge of updating, rereading, translating or developing original thoughts and dialogues, and who expand the ways of conceiving choreographies of the impossible. This web, which takes place as a flux, consists of four essays written individually by the curatorial team, reference texts and a chorus of commissioned critical essays, which reflect the profile of the 121 participants.

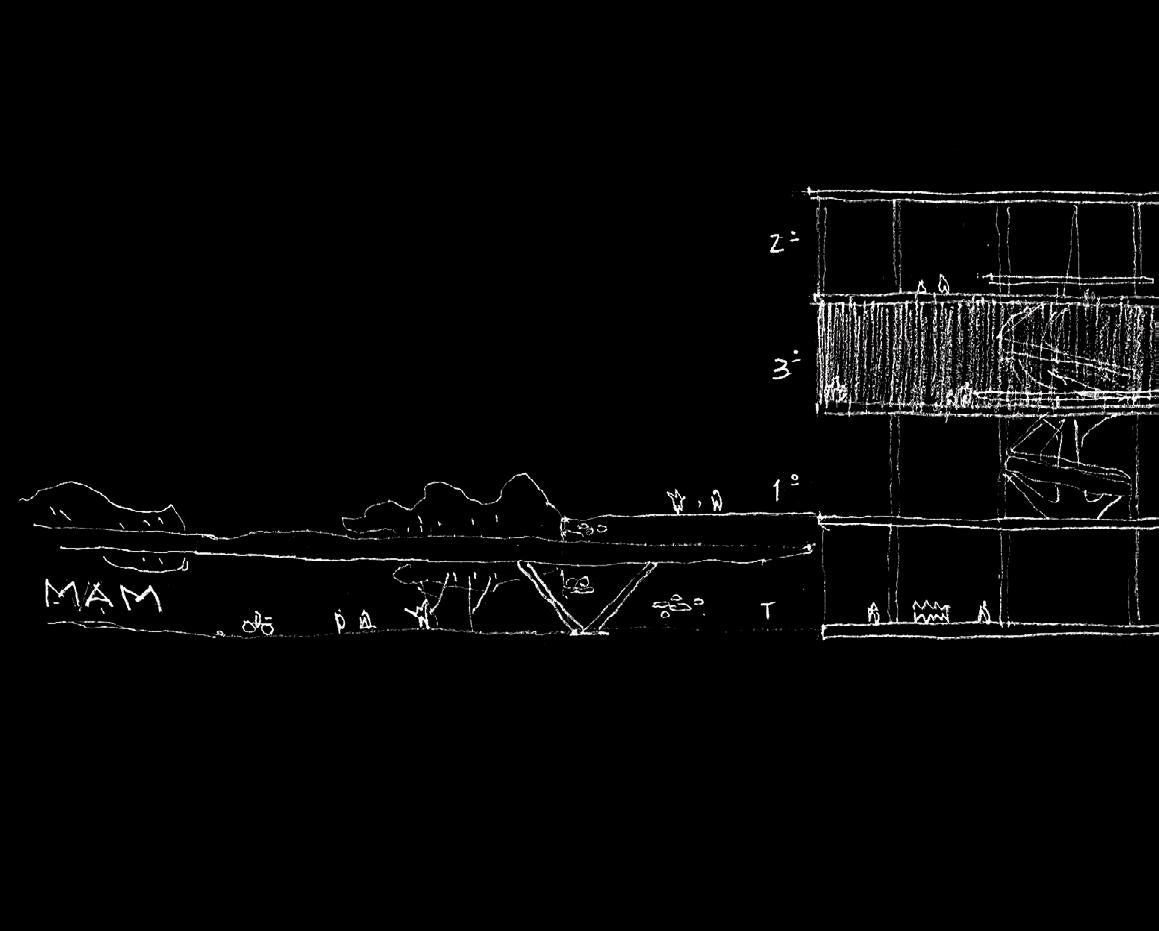

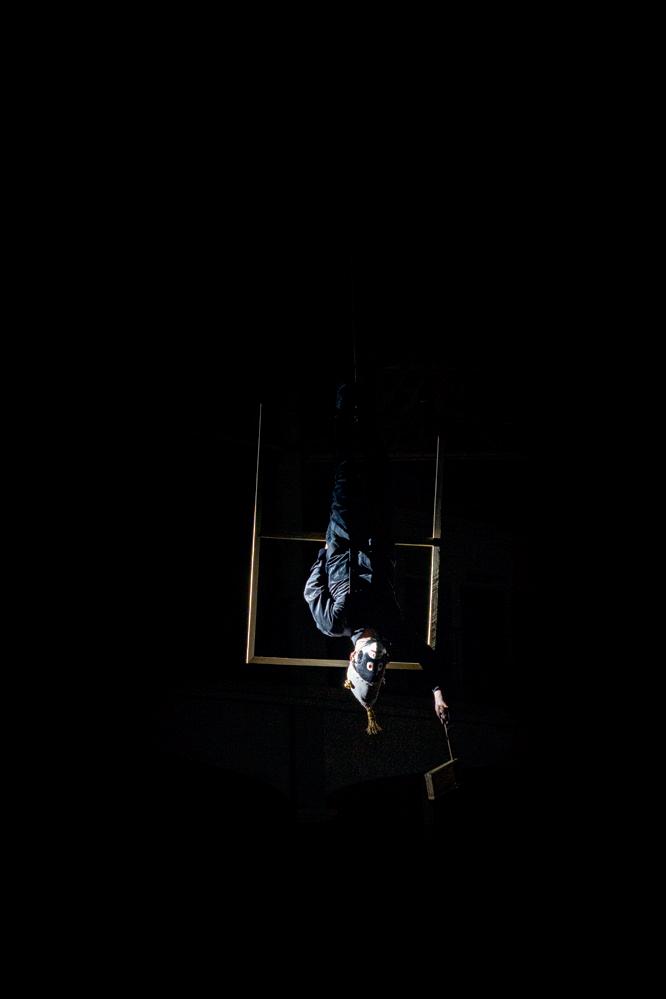

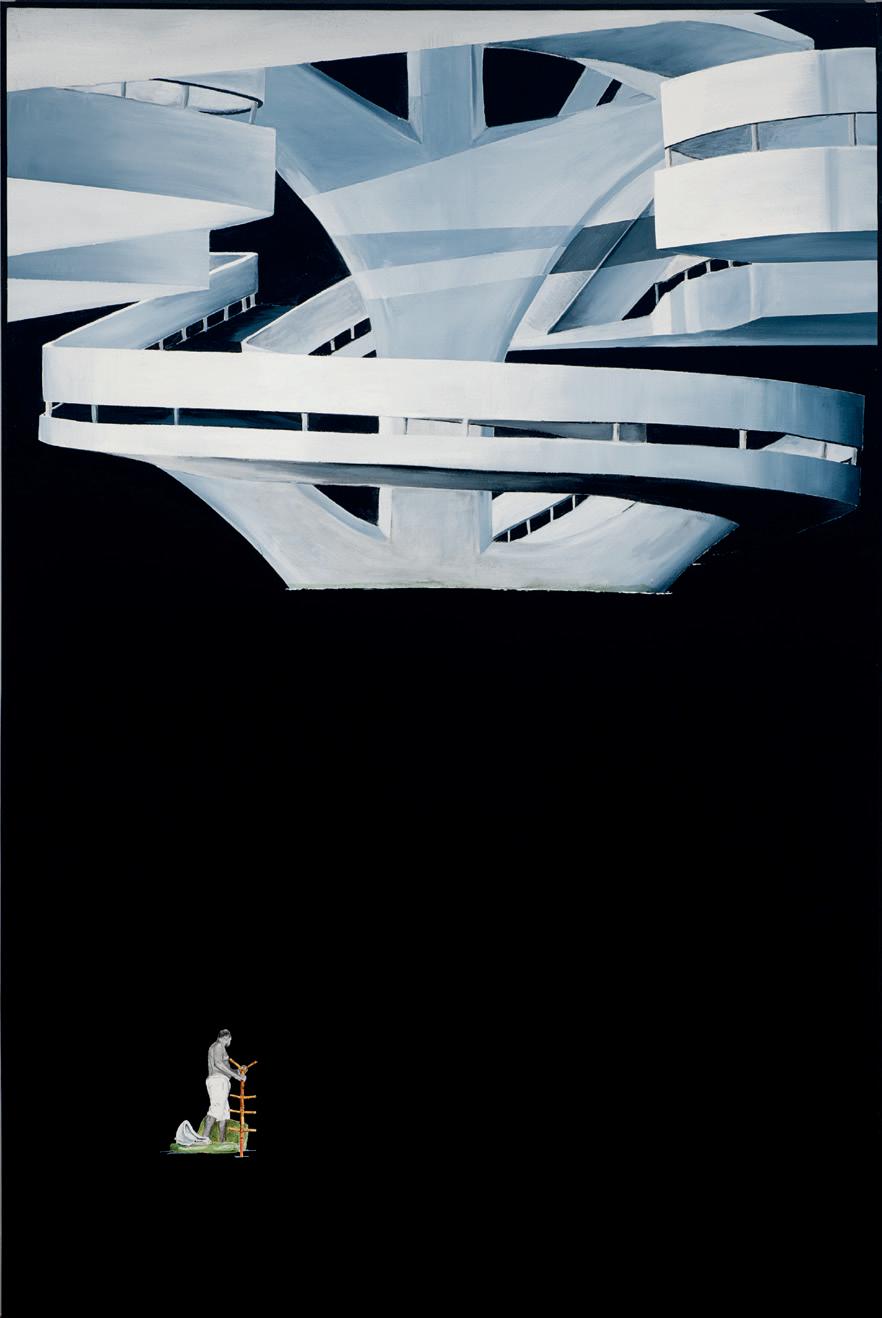

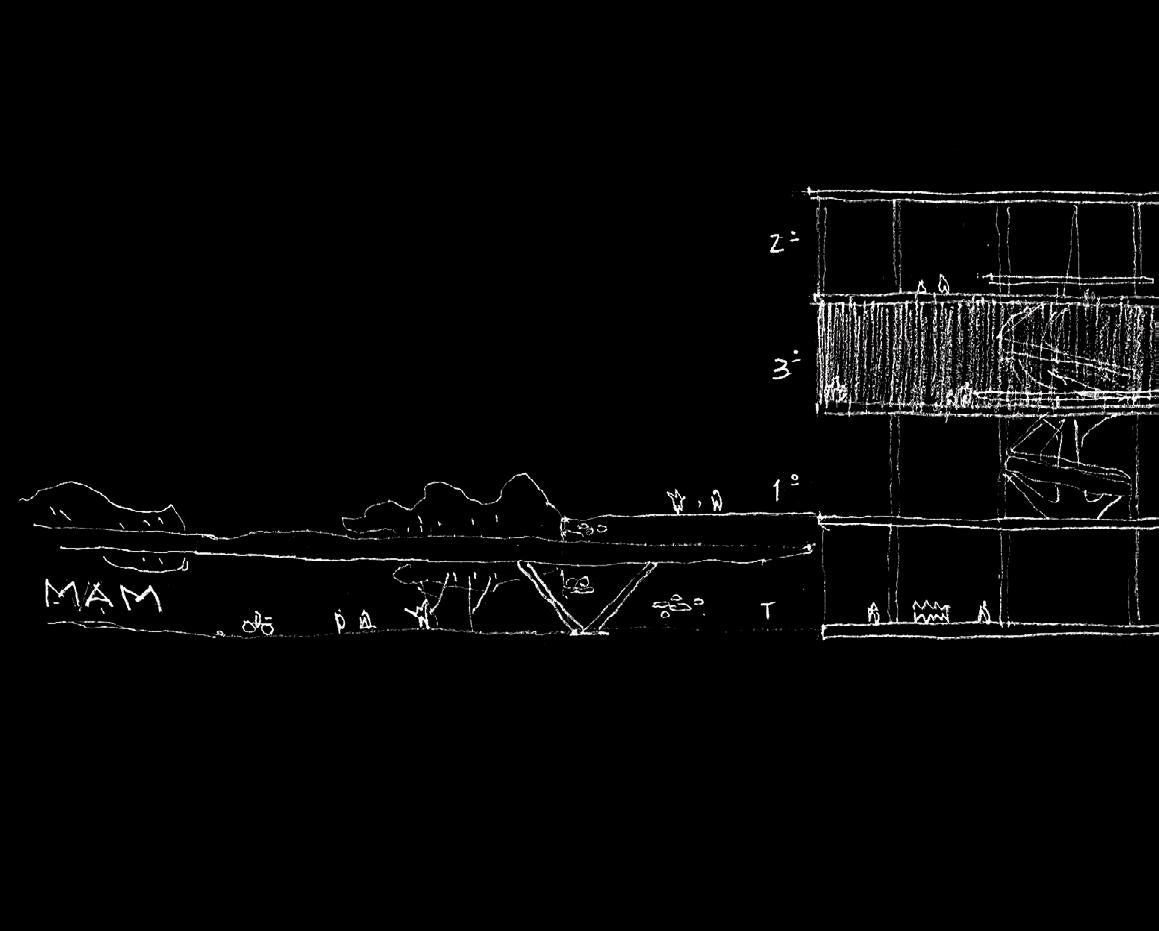

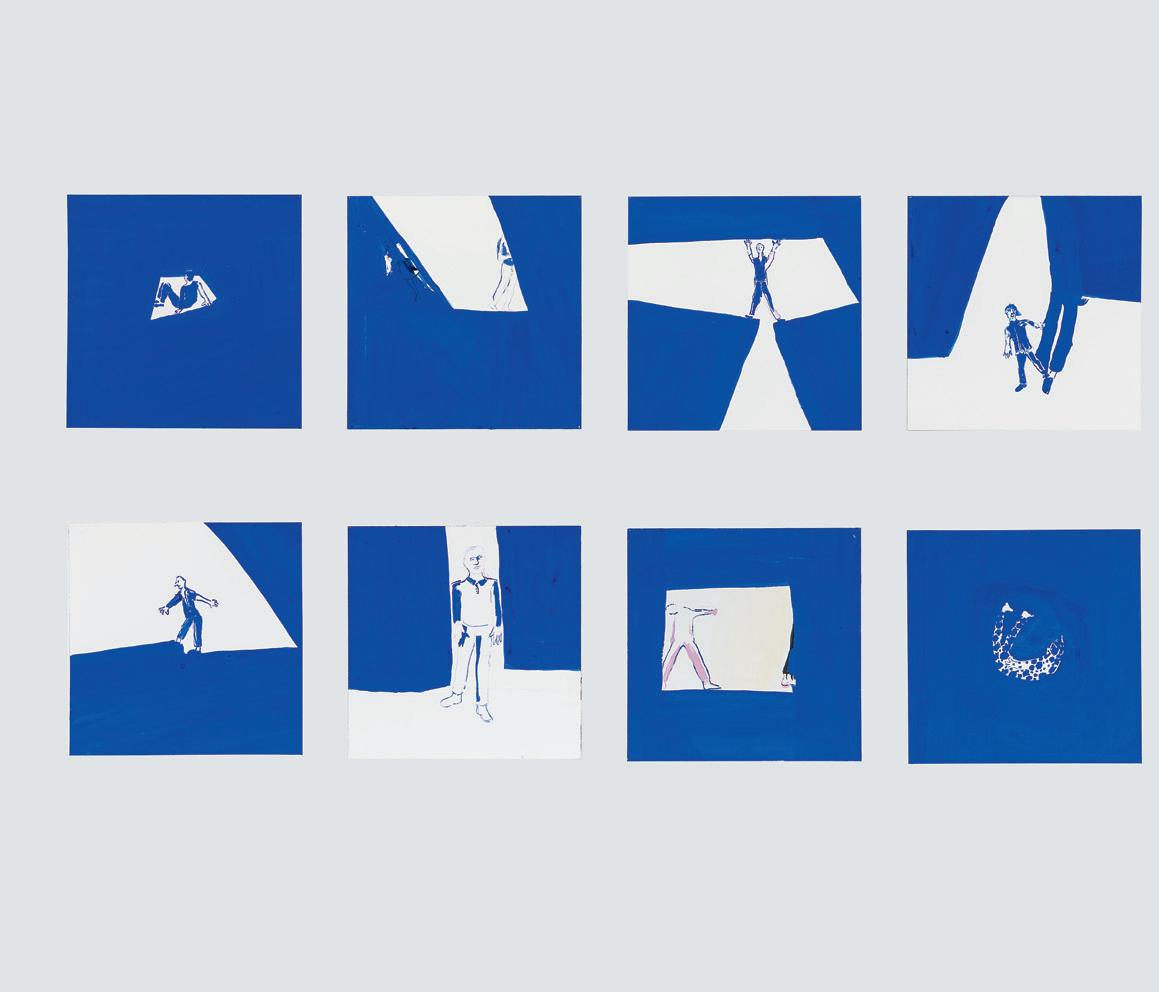

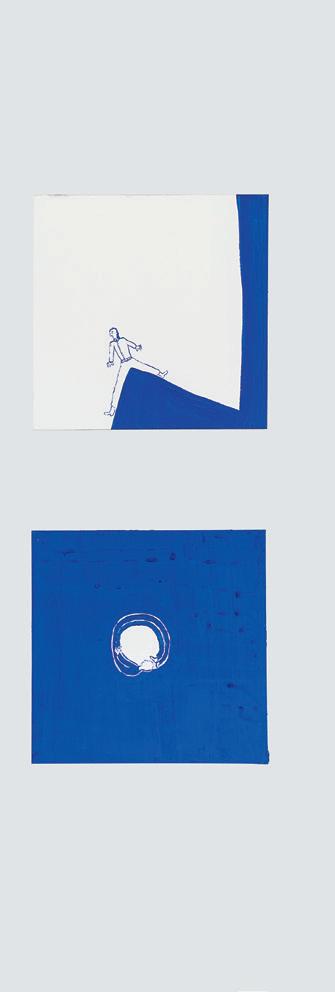

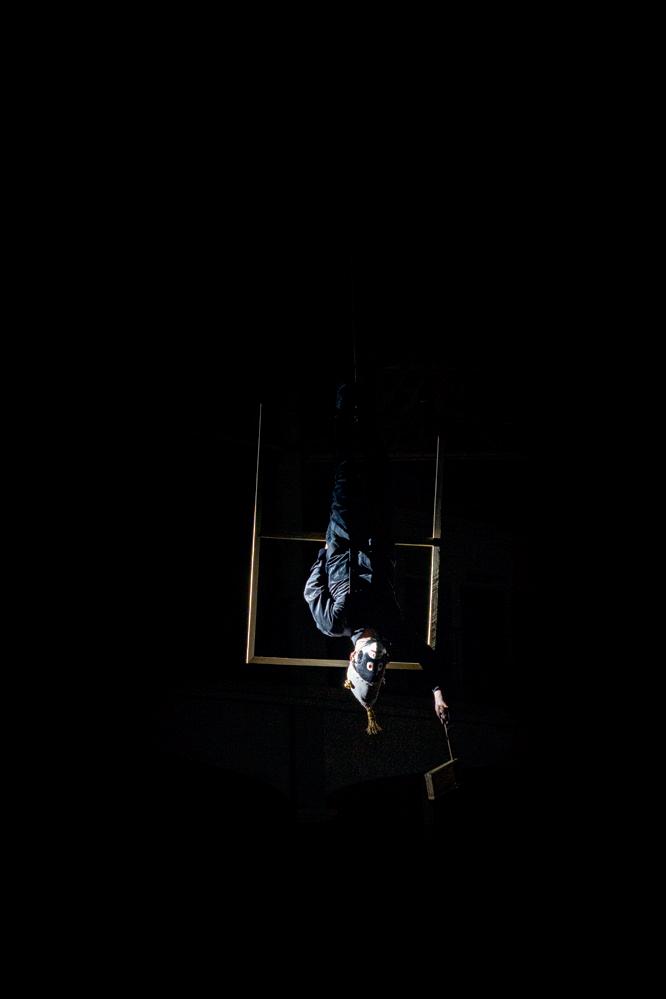

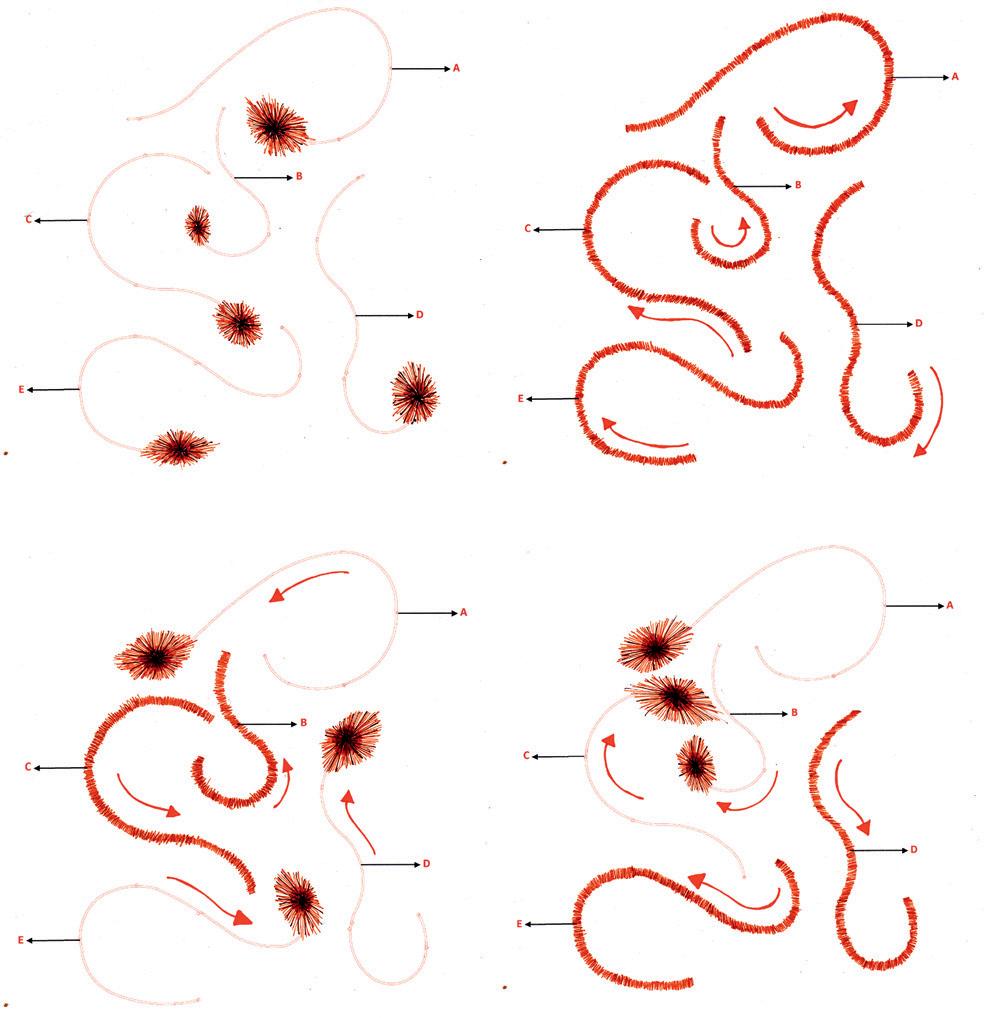

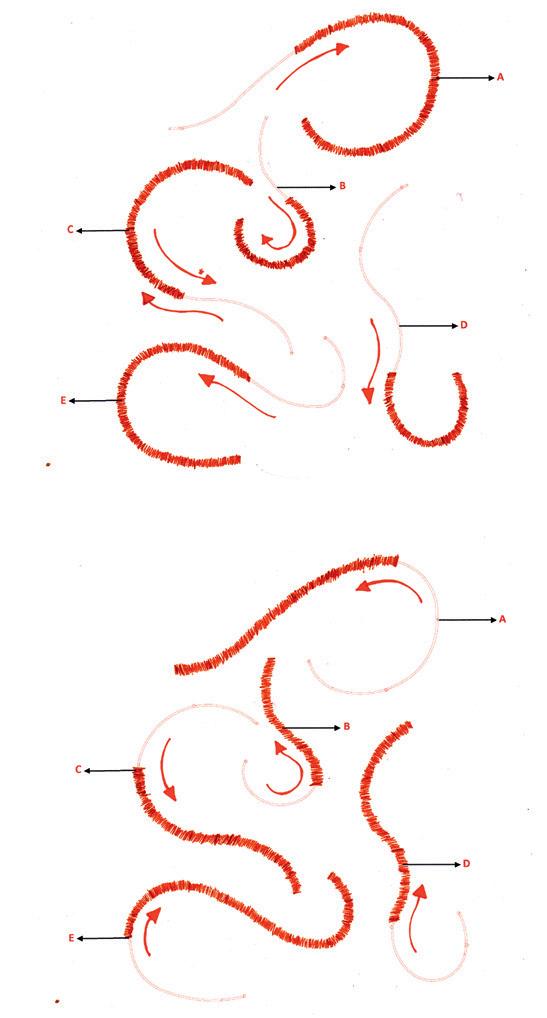

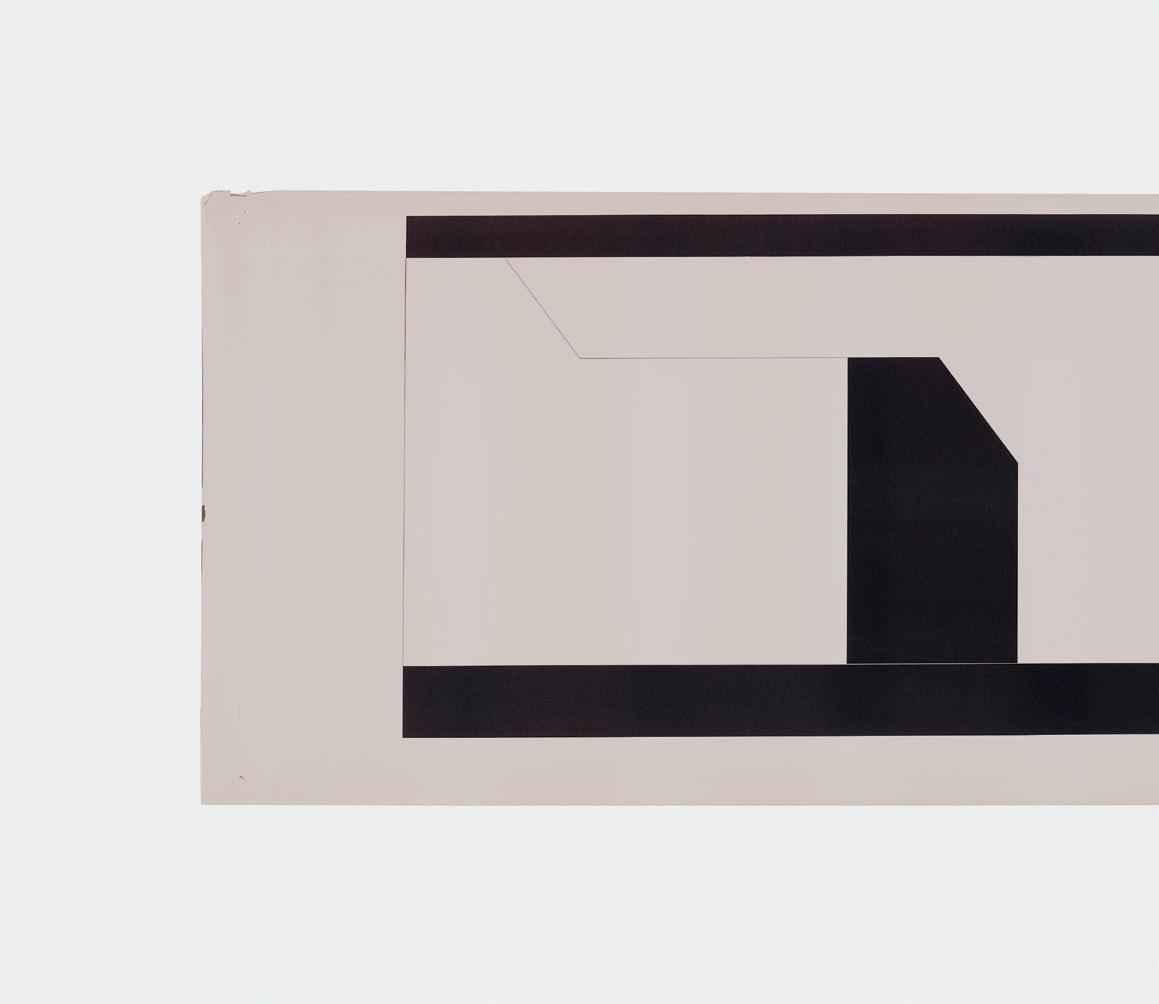

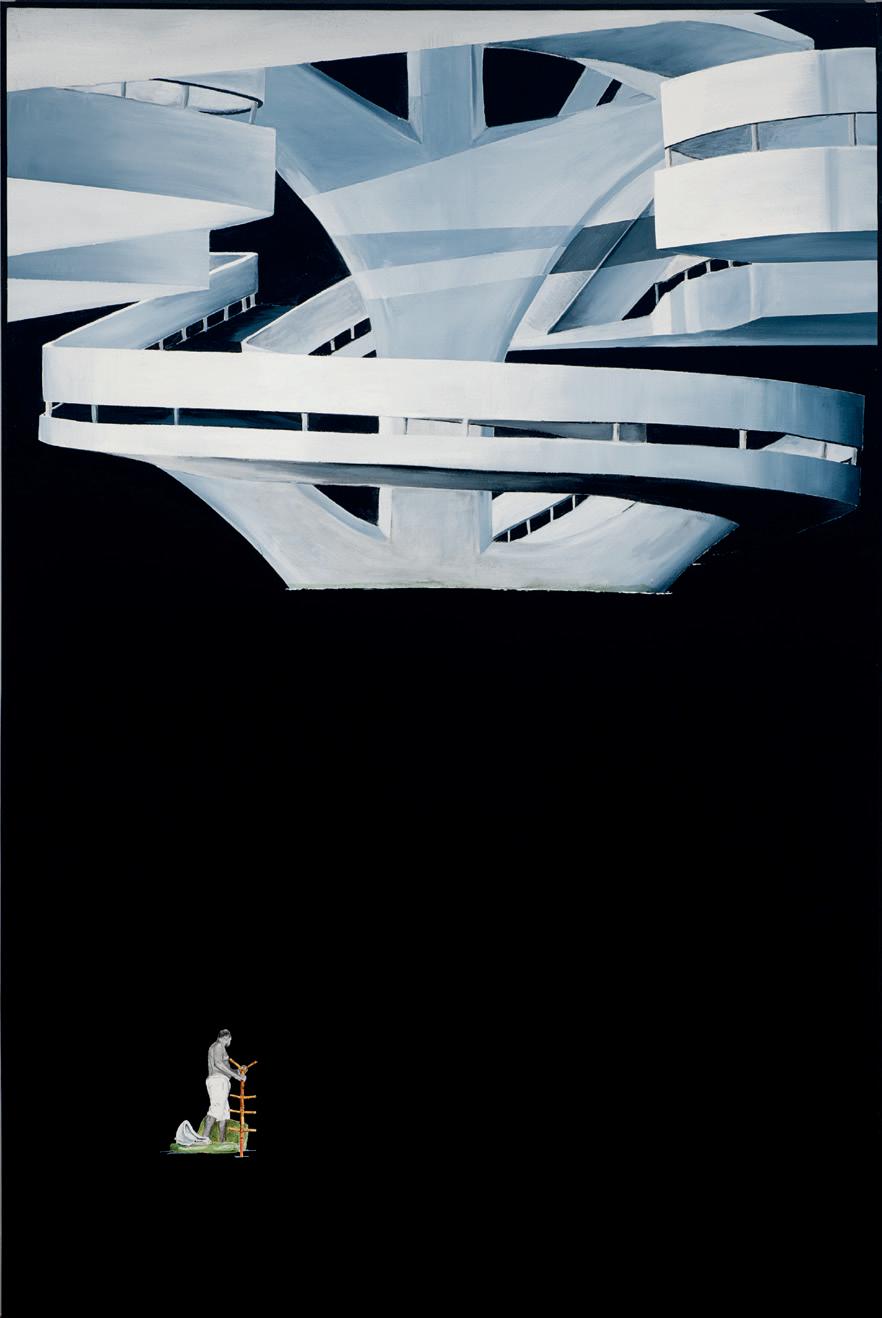

In the exhibition space, a choreography of paths was created, as defined by Vão, the firm responsible for the architectural and exhibition design of choreographies of the impossible, which has no themes or chronological organization. It is a proposal capable of making us feel in our bodies what the shifts in flows and the interventions in the building produce, such as the inversion of the floors, an illusion created by the envelopment of the central span – one of the most emblematic architectural structures of Oscar Niemeyer’s original project – and a design that arranges a sequence of movements that accelerate, slow down, pause, and suggest different speeds, linking different rhythms and contrasts beyond the monumental scale of the Pavilion.

These choreographies of narratives place great importance on the formative work carried out by Fundação Bienal’s Education team, especially

9 8

choreographies of the impossible

diane lima grada kilomba

given the challenge of creating facilitation tools that help elucidate to visitors how such paths challenge, in practice, the relationships with time and space.

The way the team narrates its path in the three movements – the name given to the educational publications that complement each other and reveal themselves throughout the construction of choreographies of the impossible – is also a good example of the way the concept radiates. Through the creation of a broad educational program and invitations to different artists and researchers, the team understands that different educational procedures are devices of liberation and freedom, if not a calling in which artistic, intellectual, and political practices become fundamental in the construction of knowledge based on exchange, collaboration, and experimentation.

We have also developed a network of artist's residency programs, formed by New Local Space (Kingston, Jamaica), Sertão Negro (Goiânia, Brazil), and Ëntun Fey Azkin (Wallmapu, Ancestral Mapuche Territory). These independent spaces and initiatives are circuits that foster art, education, and new modes of organization, also providing training and redistributing access to the local scene, in view of the crises and social and economic impacts that these territories face. We believe in the role of platforms such as biennials in creating formative processes and research and in strengthening collective movements. We also believe that, together with the discussions that our project proposes, we can contribute to the maintenance and consolidation of solidarity networks such as Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho – MSTC, which is present at the 35th Bienal both as a participant and in charge of food service.

The choreographies of the impossible also have an extensive public program, composed of activations, performances, roundtables, talks, film screenings, workshops, and laboratories throughout the exhibition.

What can these practices, which choreograph the impossible in their original locations, generate when put in dialog here? What ruptures and encounters, consensuses and dissensuses, can this reunion create? For us, these questions play a central role. They make it possible to invent and discover new and unknown choreographies.

hélio menezes manuel borja-villel

2nd floor plan closed space open space 3rd floor plan closed space open space

image: Vão Arquitetura

what is choreography? what is a choreography? what are choreographies? and what are the choreographies of the impossible?

what is impossible? what is the impossible? and what about the impossibility?

can a choreography circumscribe the impossible?

how does one define choreography? is it an art? a drawing? an inscription? a movement? is it a dance?

is choreography the art of dancing? or the art of drawing a movement that is danced?

is it the art of inscribing a movement? of drawing a set of movements? their sequence? in all their parts and fractions?

the spelling of a movement?

the spelling of a movement that will compose a dance? the spelling describing how a dance will take place? foreseeing it?

time?

can we, thus, abstract the idea of choreography? slow time? fast time?

unhurried time? fragmented time? still time? can the same choreography vary according to the time it is danced?

allowing for many interpretations? creating multiple dances?

dances that were unimaginable before?

dances beyond the power of imagination? or beyond what was imagined? or beyond what was imagined for us?

can a choreography interrupt the impossible? and can a choreography occupy the impossible? space?

empty space? full space? horizontal space? vertical space? diagonal space?

13 12

c-h-o-r-e-o-g-r-a-p-h-i-e-s grada kilomba

how does one occupy the space for a choreography?

mindfully? absently? around? about?

can the choreography get across notions of space? the same way it gets across notions of time? creating infinite dances?

crossing the impossible? beyond impossibility?

and the body? who dances the choreography?

is choreography, then, the writing of the body? and is the body the center of the choreography?

the body?

the physical body? the body, not the object?

the possible body?

who is possible? who is impossible? and who becomes an impossibility?

what is impossible? the body?

the impossible body?

the denial of a body? or its desire?

the violence against a body? or the repressed desire? the refusal of a body? or the obsession over it?

can the choreography dismantle the impossible?

creating multiple dances? in multiple variations? in multiple forms? and in multiple bodies?

crossing manifold notions of time, space, presence, and body?

what are the choreographies of the impossible? and what is the 35th Bienal de São Paulo?

the revealing of impossibles? the affirming of possibilities before the impossible? or the revelation of what was always possible? revealing multiple possibilities?

Berlin, June 20, 2023

translated from Portuguese by bruna barros and jess oliveira

choreographies of the impossible, crossroads of time hélio menezes

I learned from an early age that Time is another name of the Kitembo nkisi, god of infinity, being that inhabits and crosses all beings and times. An entity that inhabits and takes on the body of a sacred tree. A Time that is fed. Its twinning with the indeterminable times of natural and more-than-human cycles, and the consequent collapse of sequentiality as an ontological dimension of time, embody, it seems to me, an interesting and radical possibility of altering the rigid time-space binomial. An inherent ability to de-narrate stories by the movement itself in/of time.

In a similar cadence, the thinker Leda Maria Martins has suggested that time can be experienced through the principle of movement: a curve that turns, goes back and forth, shuffles the chronology, conjugates remembering and becoming as Siamese verbs. The author reminds us that one can experience times outside linear mechanics, irreducible to the modern idea (i.e. the colonial idea) of a sequential or progressive chain. A time lived ontologically with and as a body. And which finds its translation in linguistic and thought systems for which the separation between ethics, aesthetics, body, time, and life lacks explanatory power.

As Leda teaches:

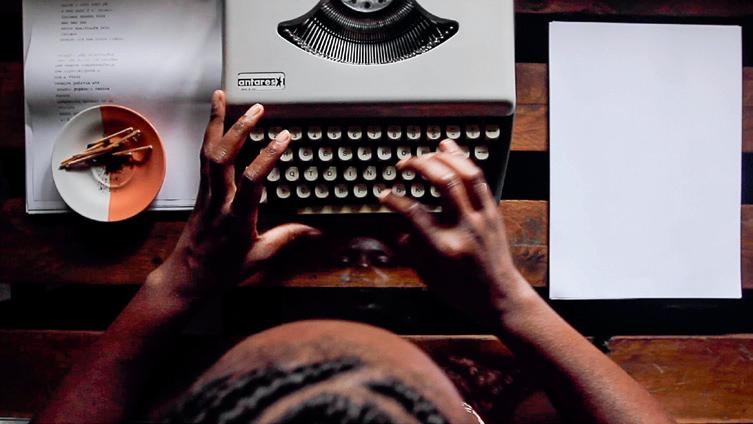

in Kicongo, one of the Bantu languages of the Congo, the same verb, tanga, designates the acts of writing and dancing, from whose root the noun ntangu is also derived, one of the designations of time, a plurisignificant correlation. Here, in a choreography of returns, to dance is to inscribe curvilinear temporalities in time and as time.1

Ntangu. — Tanga — Matanga — Tango — Matanza. To write, to dance (in) time.

These choreographies of returns, movements of the impossible, are understood in the context of the 35th Bienal de São Paulo as temporalities that are realized in episteme at each movement that seeks to escape the

rigidity of this world torn apart by the daily life of the rites and practices of total violence. And which make the idea of a full and just life an impossible occurrence. An unattainable horizon for at least five centuries, for the same and increasingly numerous wretched of the earth 2 A world against which, in the end, attempts are made, as unavoidable as they are improbable, to wriggle and escape, refuse, confront, reverse, and repair the consequences of those very contexts that make the lives of some more impossible than the lives of others.

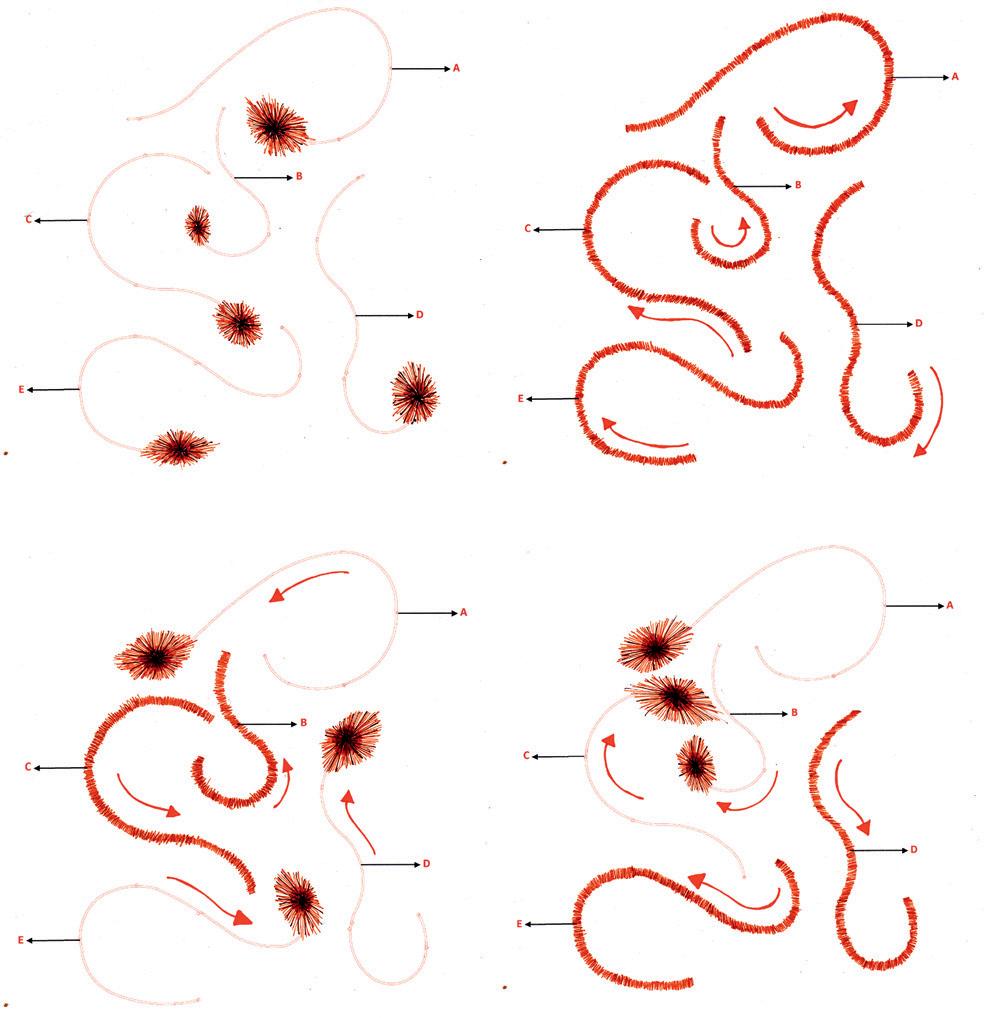

These spiral understandings of time, which perceive it and conceive it as localized and embodied knowledge, the matrix of all motricity and therefore of all possibility, support and find an echo in the choreographies of the impossible. The desire to gather and propose relationships between a set of artistic and social practices that claim other cosmoperceptions of time, that try to choreograph other configurations of the world — despite dealing with impossibility as a condition — was the basis for the research that resulted in this 35th Bienal, as well as in the essays and images that make up this publication now available for your reading.

There are several, even infinite, times at play here: there is oneiric time, and its capacity for transmutation to access other planes and worlds, as told in Mãri Hi [The Dream Tree], directed by Morzaniel Ɨramari; the ancestral time of mulheres mangue [mangrove women] by Rosana Paulino, powerful figures in form of roots and anthropomorphic trees, in which life, mud and renovation are indistiguishable; the telluric time of ceramics, unearthing stories of exploration but also of healing, as Marilyn Boror Bor and Simone Leigh teach us, or even M’barek Bouhchichi, in suppressing the distance between Dave the Potter’s verses, M’barek Ben Zida’s lyrics and Conceição Evaristo’s writings. There is the time-without-time of those who live “in the time of capture,” as Stella do Patrocínio tells us in her

15 14

1/ Leda Maria Martins, Performances do tempo espiralar: poéticas do corpo-tela. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2021, p. 81.

2/ Frantz Fanon (1961), The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

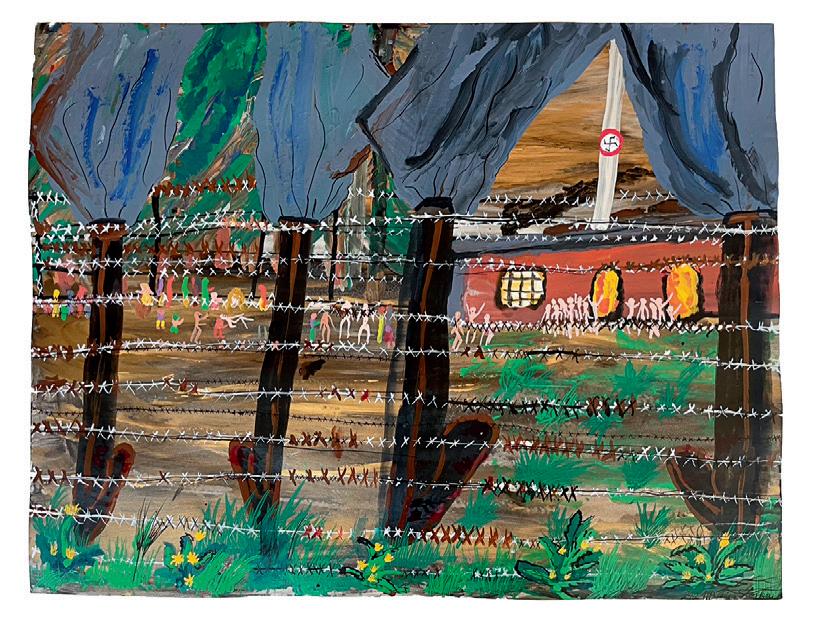

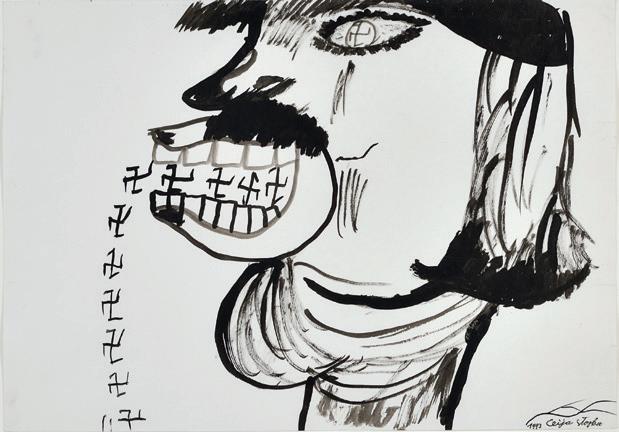

Falatórios;3 the time that dwells in the hinge of re/memory with delirium, as Aurora Cursino and Ubirajara Ferreira tell us; the time of horror and its incarnate effects, about which narrative is impossible (but is still spoken of), as Ceija Stojka did.

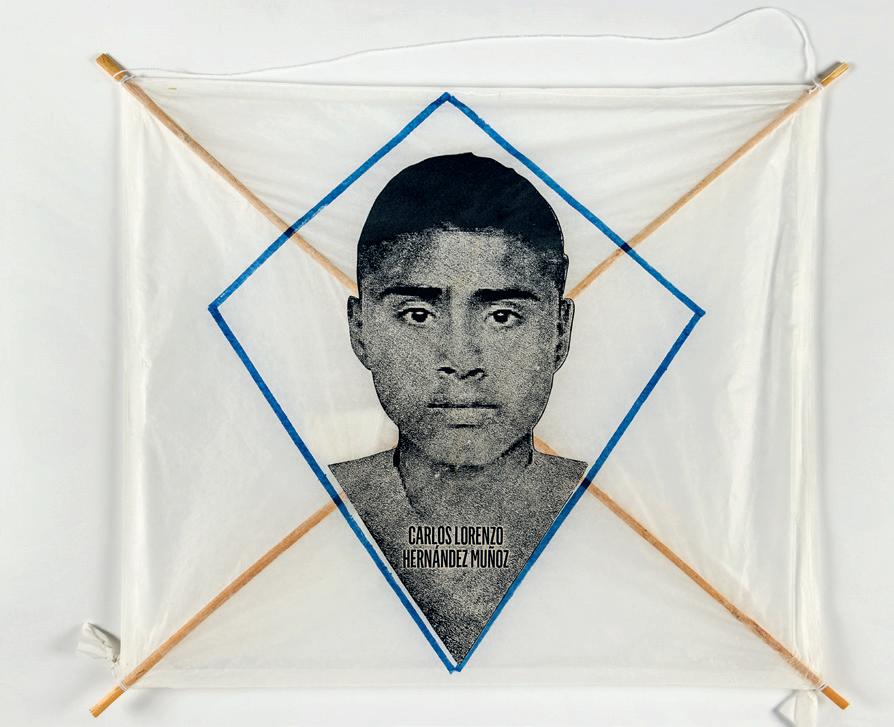

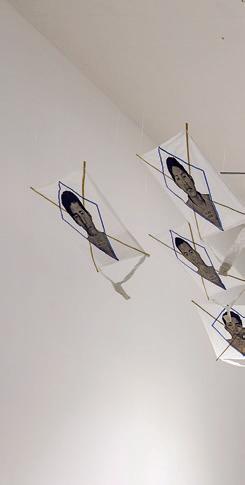

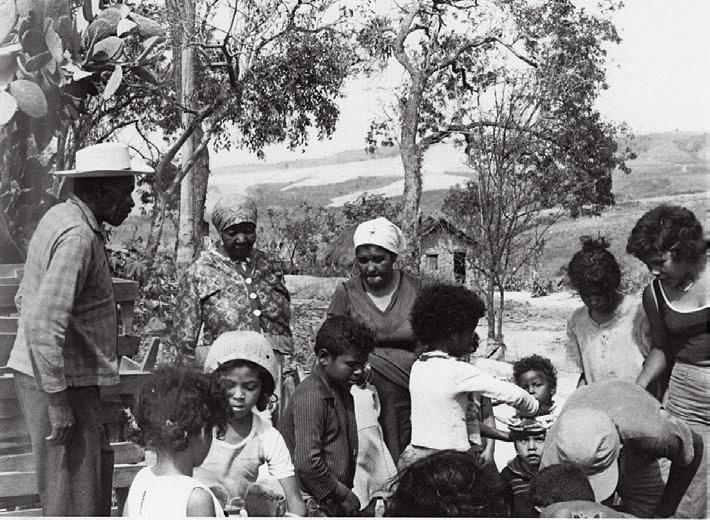

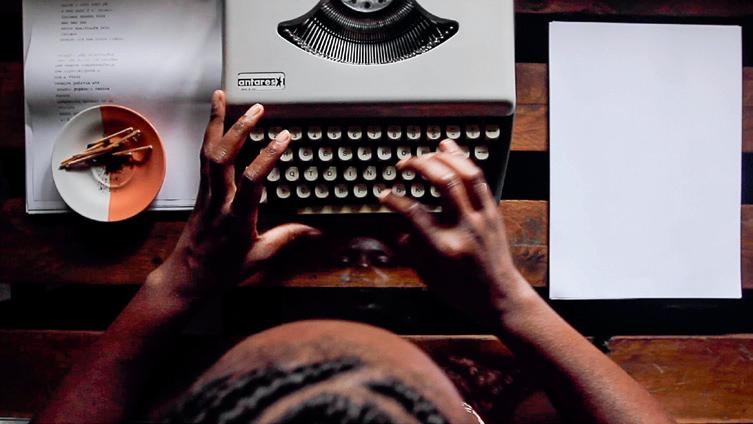

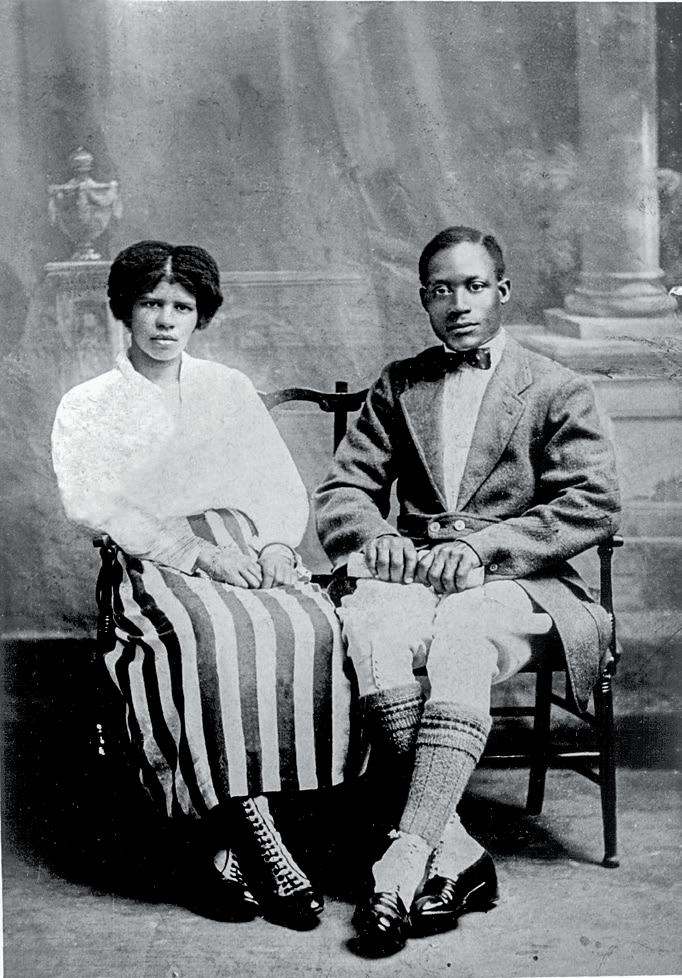

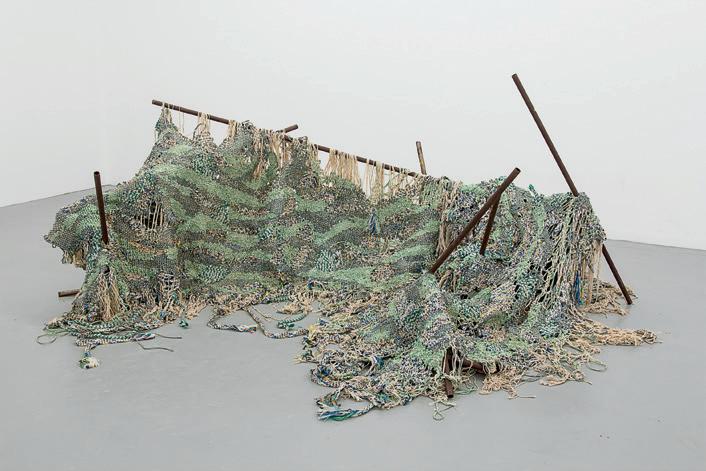

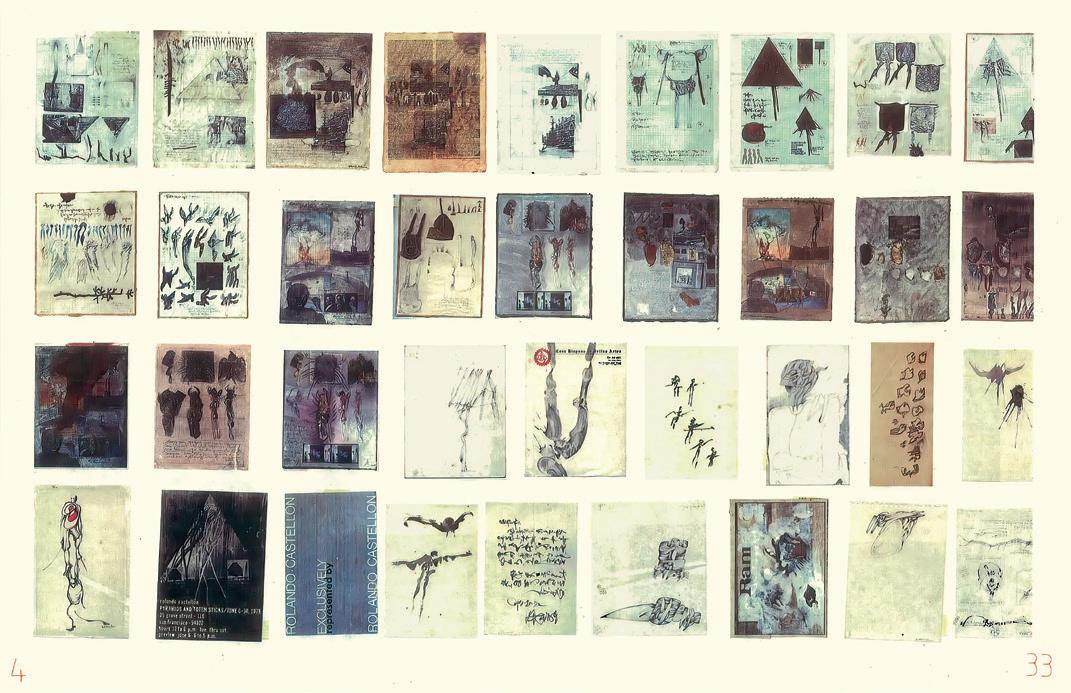

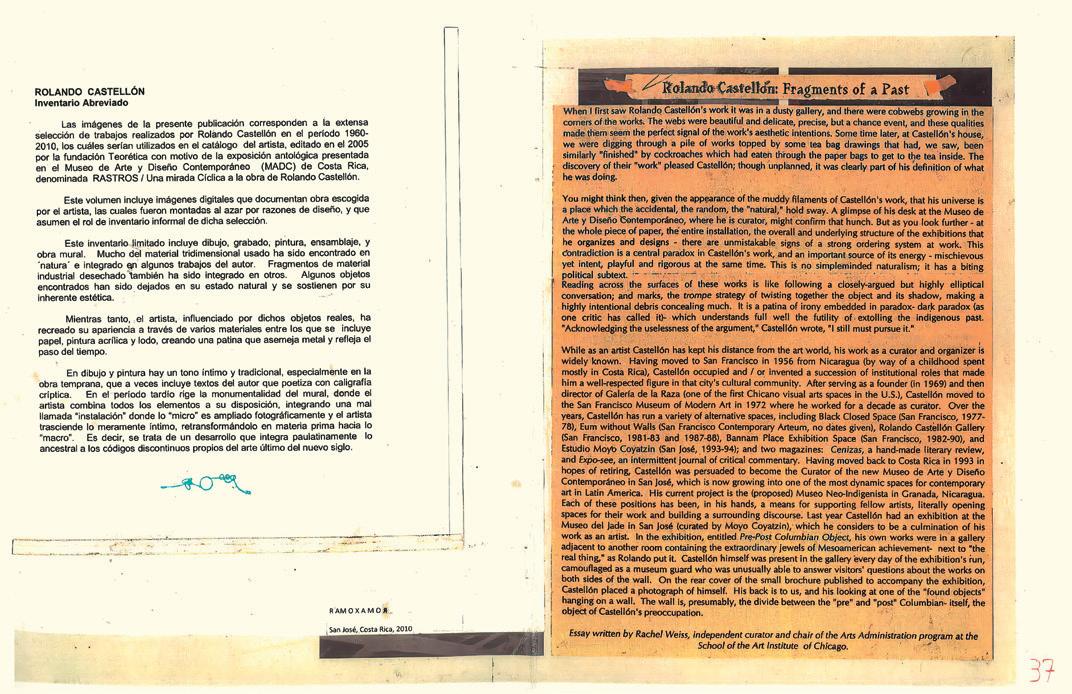

There is the time of a time that ends, as in the Silent March, organized by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation on December 21st, 2012 — the day the world ended, according to the Mayan calendar. The slow time of sowing and the uncertain time of harvesting, set by the criollo corn garden, and unsubjectable to monoculture, which Denilson Baniwa explores in this Bienal; the time of re/de/composition of fungi, plants, and other beings beyond humans, in long-lasting cycles where life and death are indistinguishable markers, as Daniel Lie suggests. There is the cumulative time of “found and unimportant objects,” collected throughout Rolando Castellón’s life in Nicaragua and Costa Rica; machinic time and dance, in its umbilical links with industrial colonialism-capitalism, which Warp Trance, by Senga Nengudi, Tales of the Copper Cross Garden: Episode I, by Sammy Baloji, and Sumidouro nº2 — diáspora fantasma [Sinkhole No. 2 — Ghost Diaspora], by Laís Machado and Diego Araúja, seize and decode. There is the time of mourning and the (impossible, though inevitable) reconstruction of inter/rupted kinship ties, as in A água é uma máquina do tempo [Water is a Time Machine], by Aline Motta, which shuffles Afro-Atlantic colonial histories and family stories of death and self-writing; or as in Palestine under the gaze of Ahlam Shibli, populated by images of martyrs and murdered youth, on the street as well as in domestic spaces, portrayed in Death series.

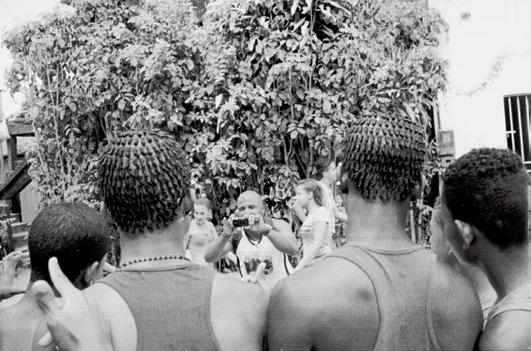

There is the time of walking feet, of body shapes that go back and forth between Senegal, France, and Brazil, as choreographer Ana Pi points out, in partnership with Taata Kwa Nkisi Mutá Imê, chief priest of the Casa dos Olhos do Tempo que Fala [House of the Eyes of the Time that Speaks] — a candomblé terreiro whose name is already a proclamation of a time that is anything but static.

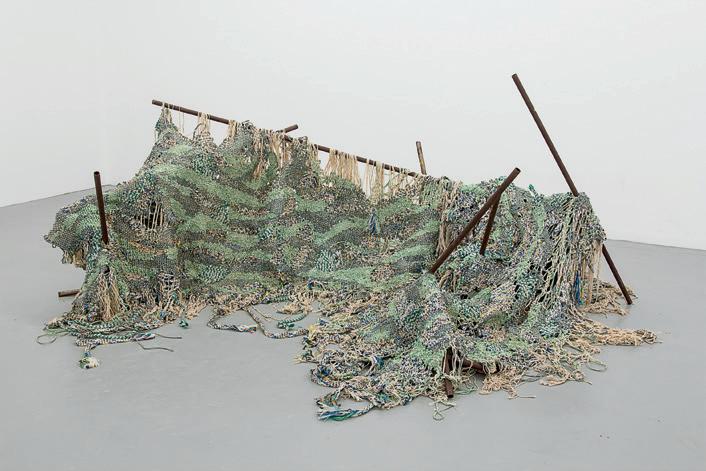

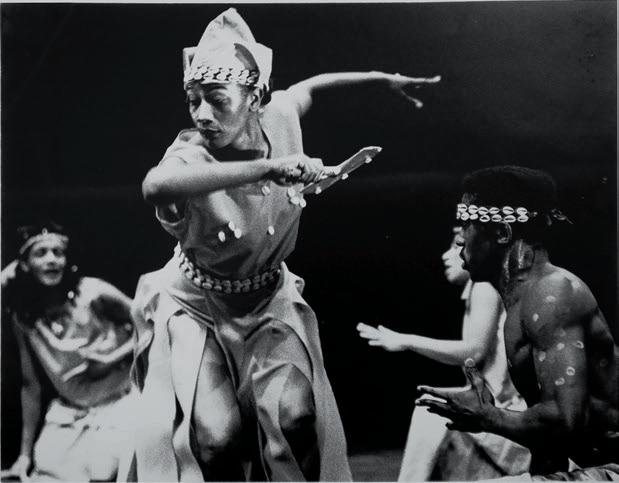

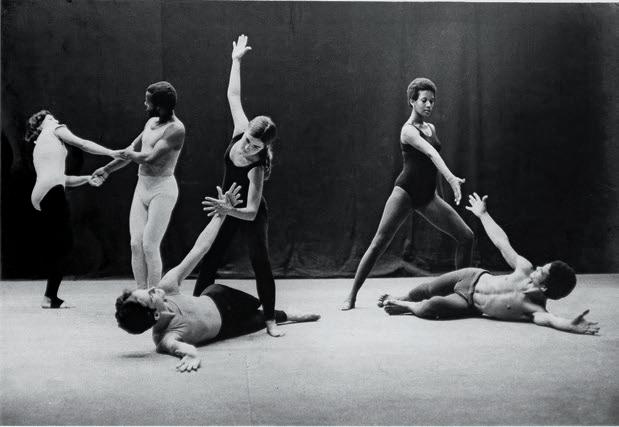

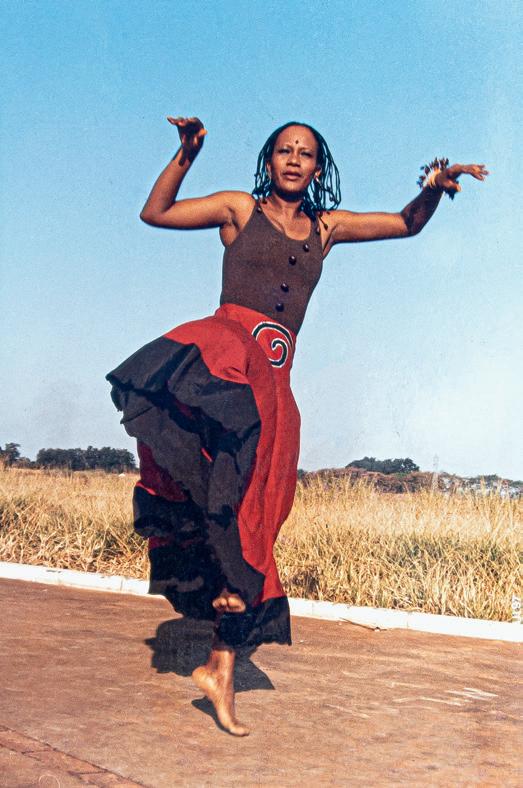

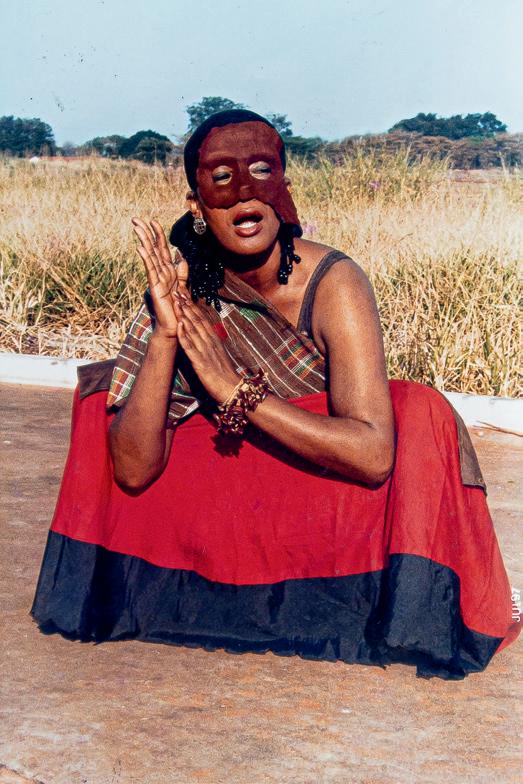

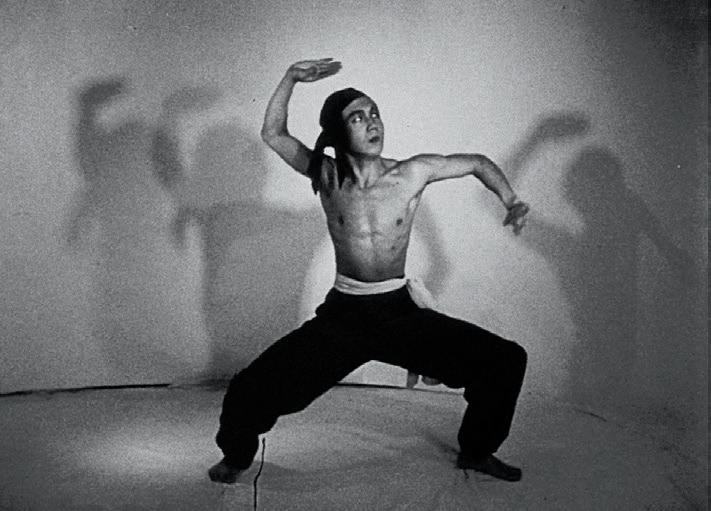

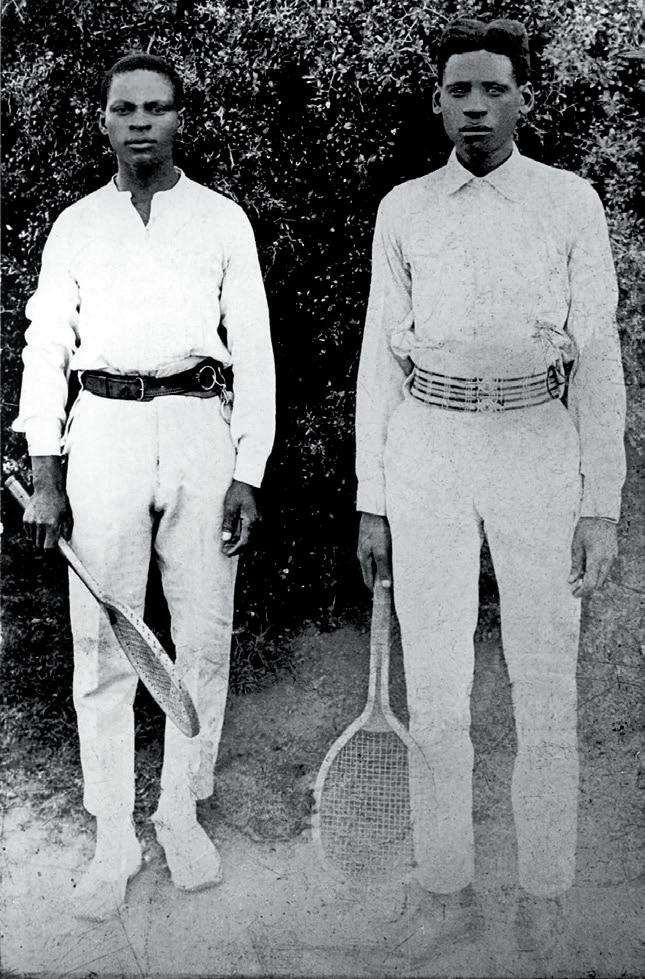

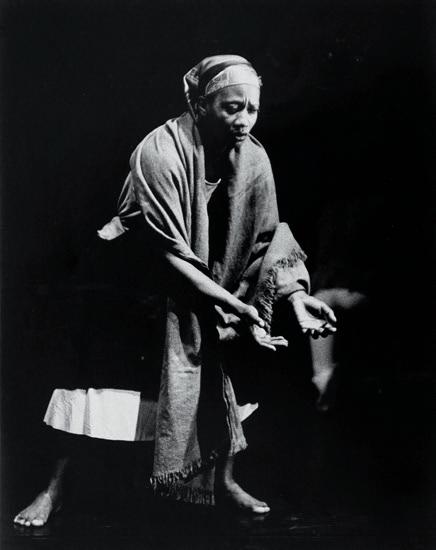

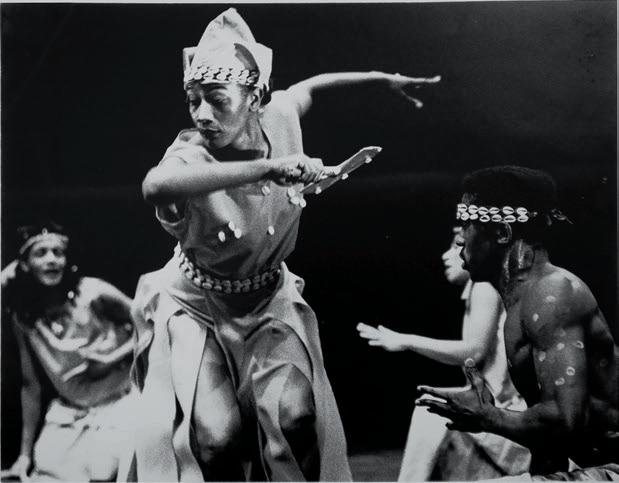

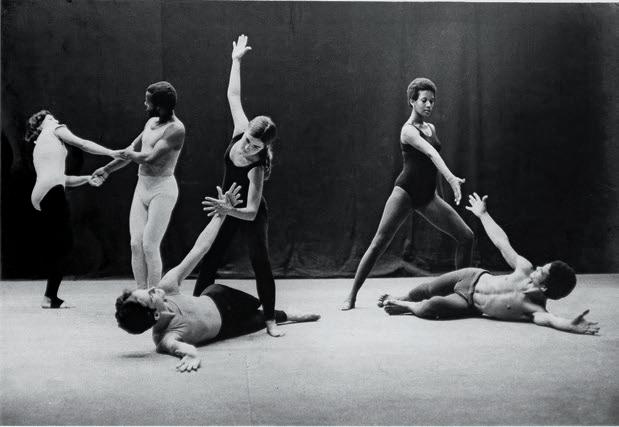

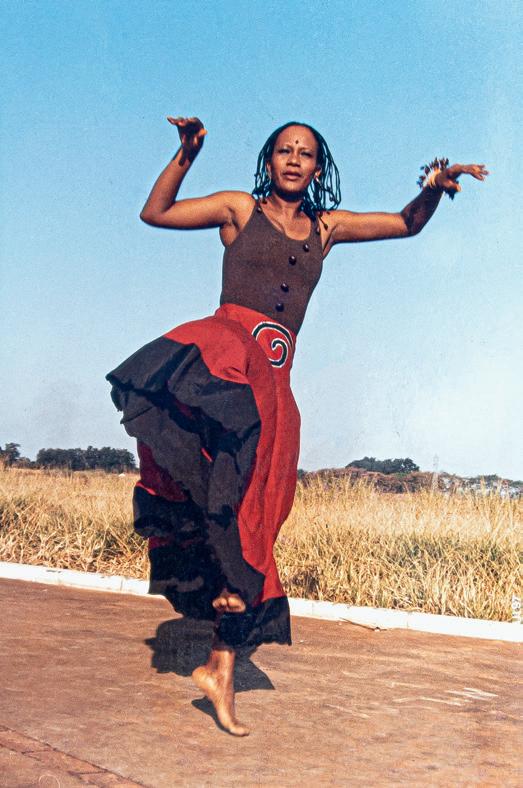

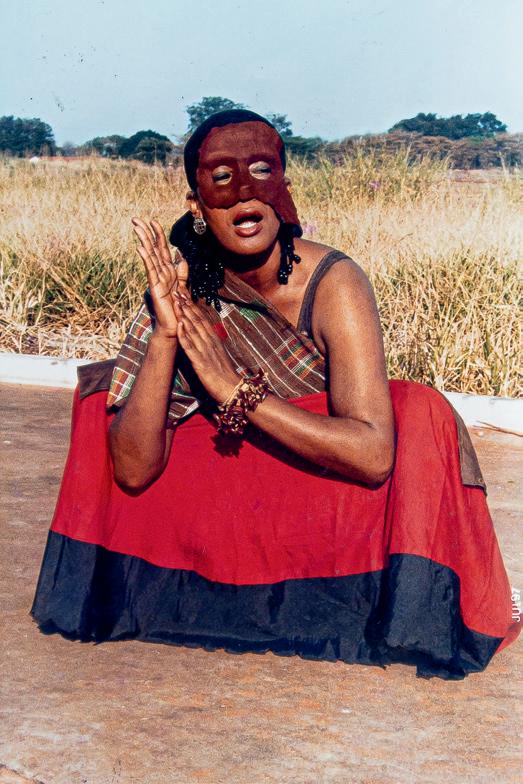

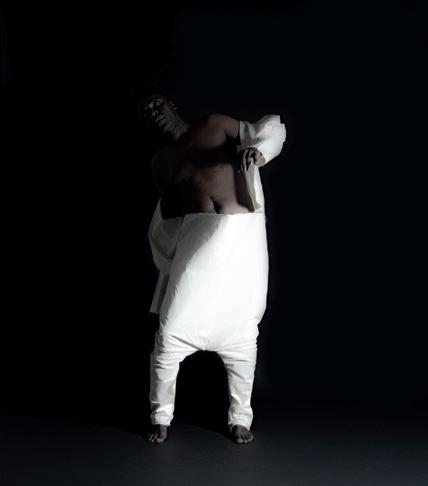

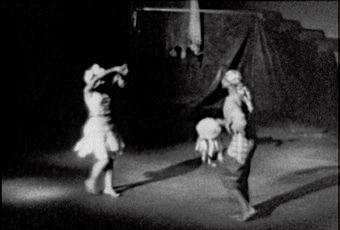

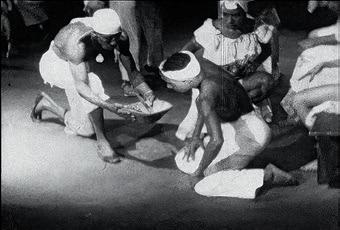

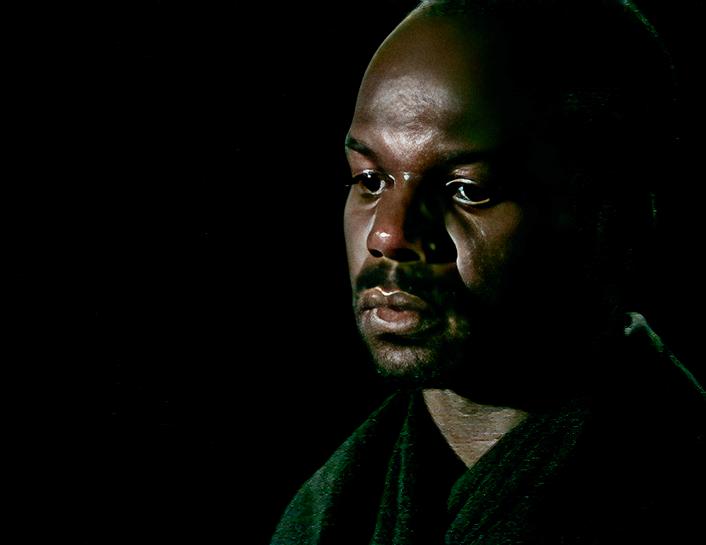

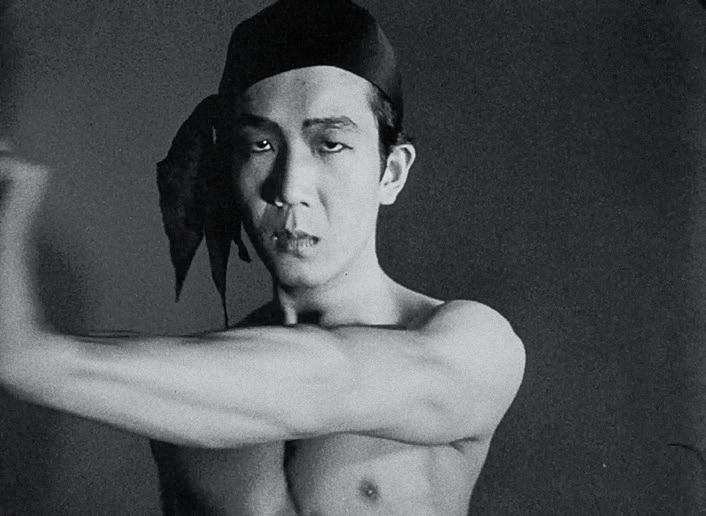

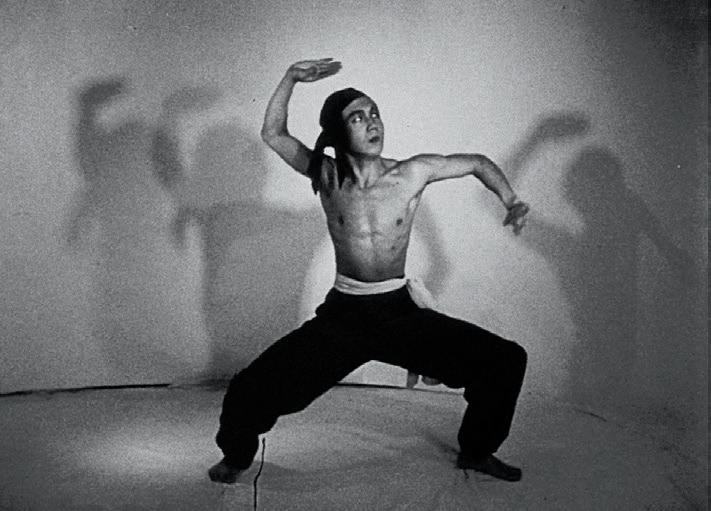

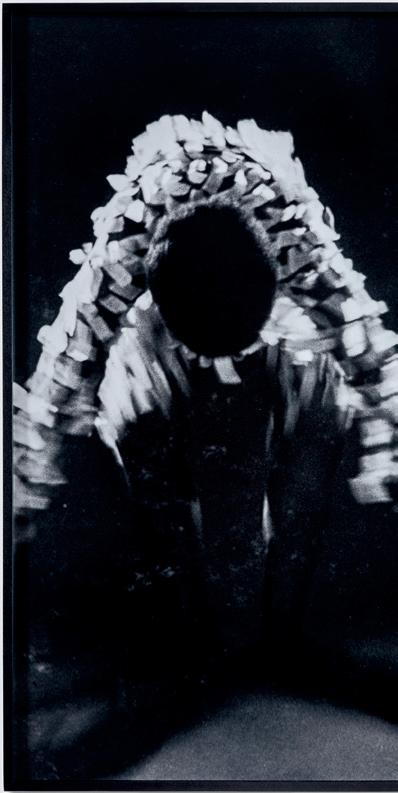

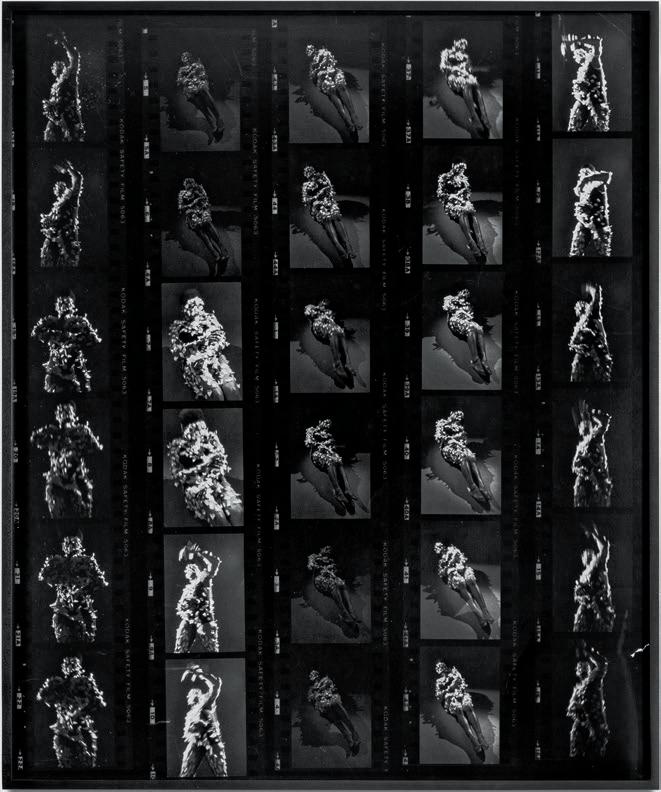

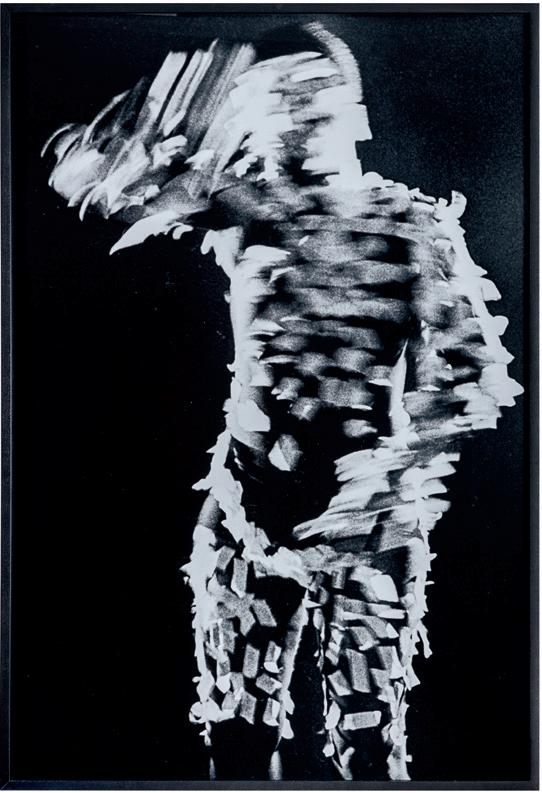

Other artist-choreographers, such as Bouchra Ouizguen, Luiz de Abreu, Will Rawls, Inaicyra Falcão, and the duo of Davi Pontes and Wallace Ferreira, are taking part in the exhibition with propositions that also use the body as the primary vehicle of time, and vice versa, expanding the dialogues (which are ancient and always current) between the fields of dance, music, and visual arts. Whether in Maya Deren’s camera, who, when filming Chao-Li Chi in a dance-trance of rigor and accuracy, ends up dancing herself; or in Katherine Dunham’s rhythmic movements, between Africas, Caribbeans, and Americas, developing a choreographic vocabulary that is still influential today on several generations of artists, here, time and body are fully interchangeable instances.

●●●

From a curatorial perspective, thinking about these folds of time of/in artistic expressions also implies relocating the meaning of choreography — taking it in an expanded and poetic sense, beyond its disciplinary historicity. Thus, it consequently required contradicting the assumption of authenticity of its etymological meaning, freeing the gaze towards movements, performed in a world that seems irresolvable, through which improvisation and creativity develop new and unsuspected motions.

Choreography was an art, a practice of moving even when there was nowhere to go, no place left to run. It was an arrangement of the body to ellude capture, an effort to make the uninhabitable livable,4

says Saidiya Hartman about Mabel Hampton, a young black choir singer from Harlem in the 1920s, in a meaning that is coextensive with what this Bienal entails. “In its

3/ Stella do Patrocínio, Reino dos bichos e dos animais é o meu nome, ed. and introd. Viviane Mosé. Rio de Janeiro: Azougue, 2001.

4/ Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

broadest sense, choreography — this practice of bodies in motion — was a call for freedom.”5

In this sense, choreographing the impossible connotes the social technologies and artistic practices that seek to circumvent the grammar of violence, referring to poetic exercises of resilience, social, aesthetic, and curatorial strategies of evasion from the norm; a permanent invitation to the fabulation of a yet unknown future — despite all infeasibility. A half-moon tempo, as they say in capoeiragem: the dexterity of combining an elusive maneuver, at the very moment of its realization, with a reverse circular kick, in a game that is also a dance, a dance that is also a fight.6 “Alongside defeat and terror, there would also be this: the glimpse of beauty, the instant of possibility,”7 Saidiya reinforces.

What does it take to make these instants emerge? What impacts can defeat and terror have on language? How have artists been reading or circumventing the effects of these impossible contexts? What aesthetic propositions emerge from unsubmissive subjectivities and collective strategies of emancipation from, against, and in spite of ruin? Beyond combative reaction, figurative description, and the politics of representativity, what other expressive forms can the radical imagination awaken, beyond expectations of resistance through responsive frontality?

“What do we want, after all, from language? Everything, everything that allows us to be in the world without bending our backs,”8 in the words of Edimilson de Almeida Pereira.

From other perspectives, the term choreography also invites us to reflect on the risk, which always lurks, of the seizure of this same dancing freedom by devices

5/ Ibid., p. 322.

6/ Reference to the lyrics of the song “Capoeira de benguela”, by Paulo César Pinheiro, from the album Capoeira de besouro. Quitanda, 2010.

7/ Saidiya Hartman, “Vênus em dois atos”, trans. Fernanda Silva e Sousa

of body conduction (not any bodies, we all know) and the codification of disruptive movements, often converted into merchandise. Whether through interpersonal relationships hierarchized by social markers of difference (race, class, gender, sexuality, et al.), by the State, or by Capital and its derived institutions of surveillance and control (those of art, especially).

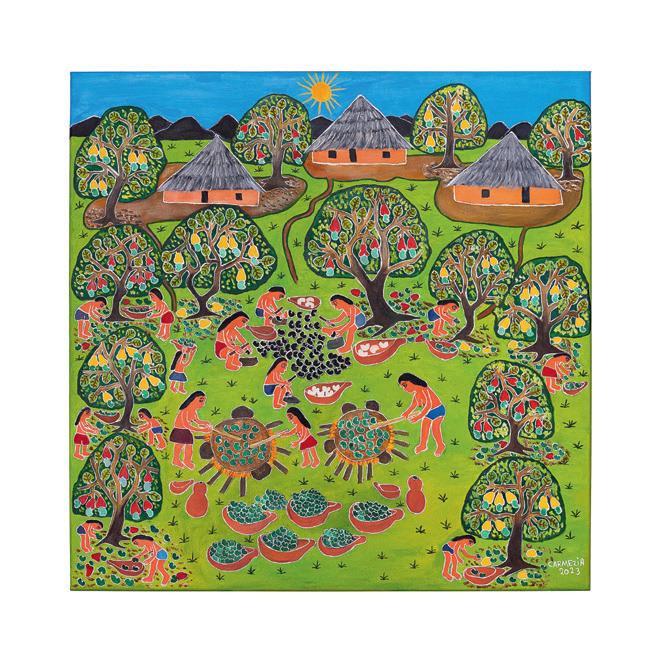

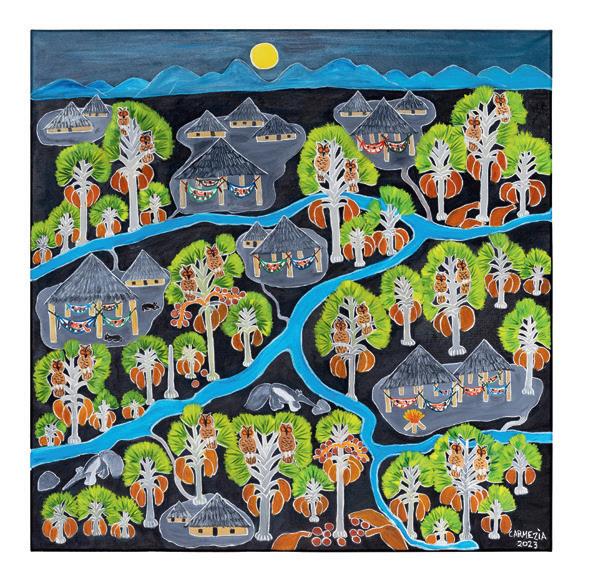

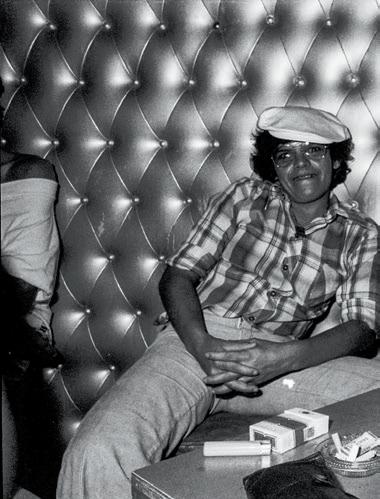

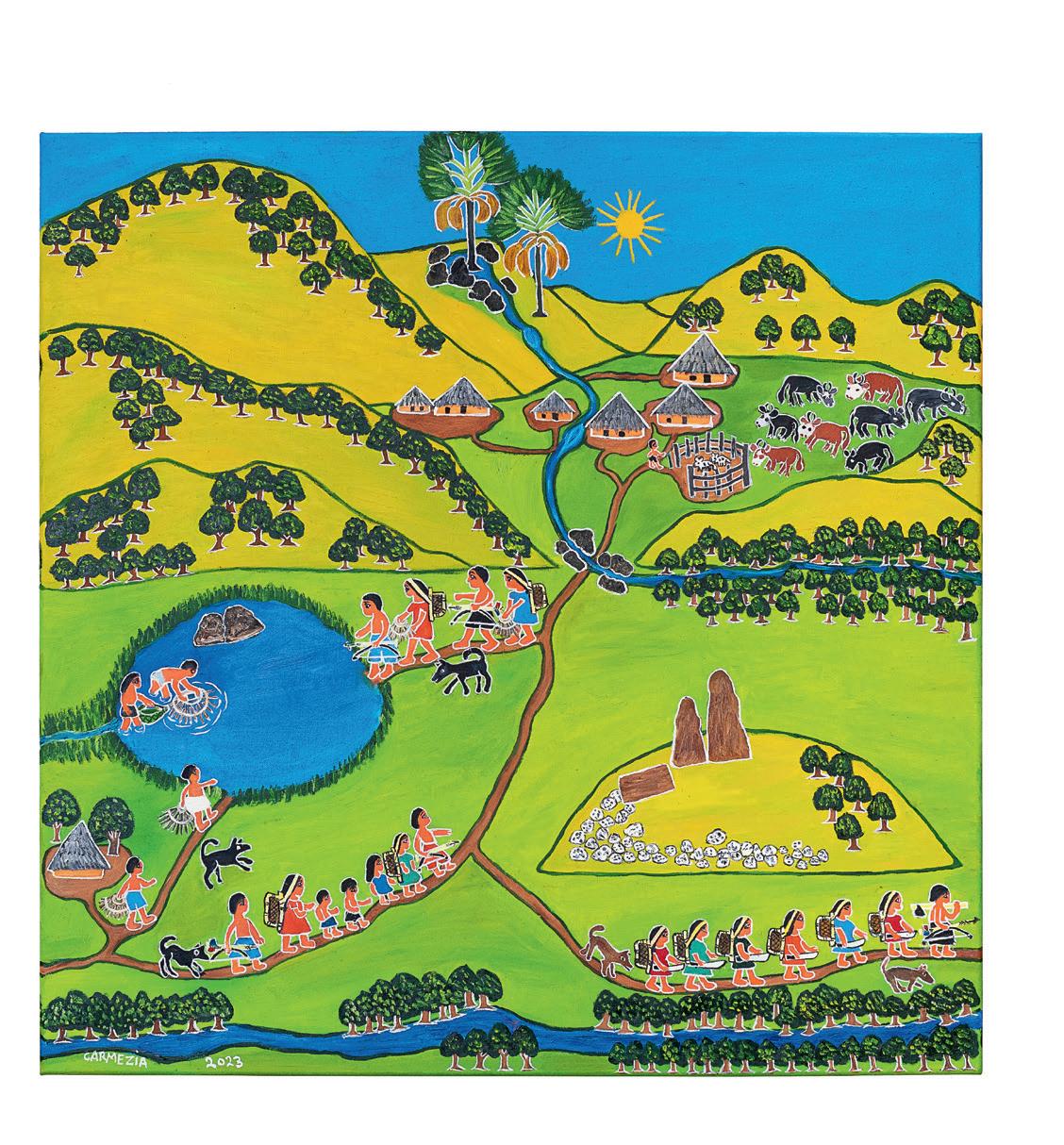

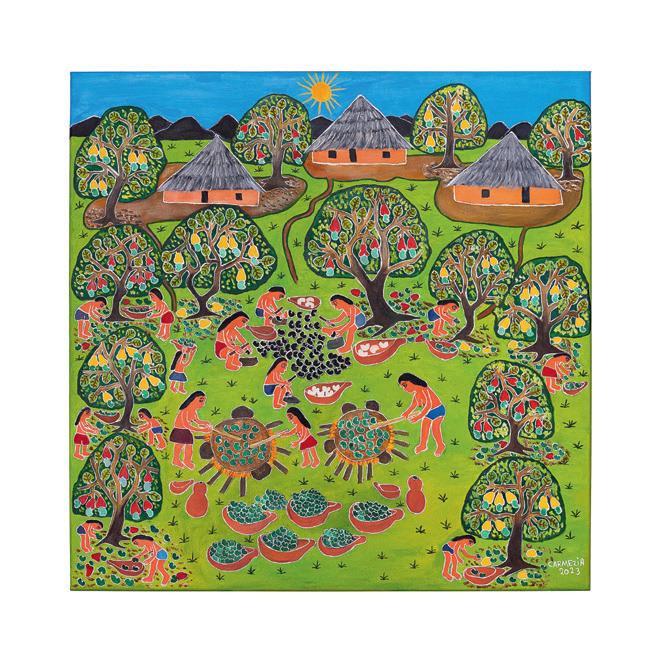

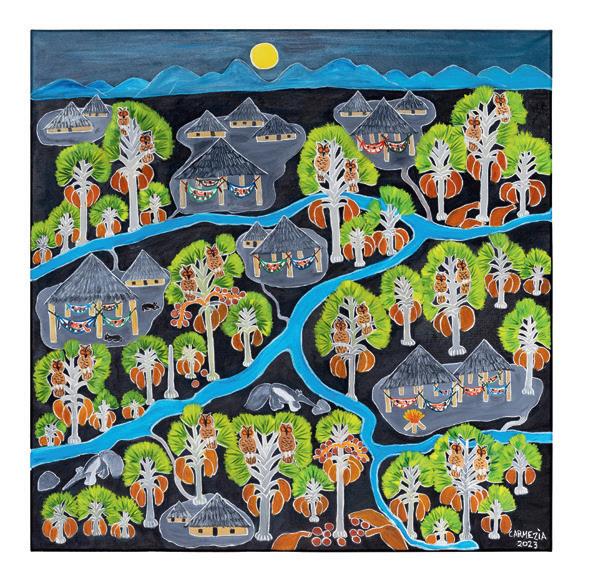

The illusion and irreality of the freedom to wander/ dance, to move in a truly free way, is a funereal characteristic of these times of extreme clarity in which we live. Of this modernity-coloniality engendered by the transatlantic trafficking of people and destinations, by forced displacements and containment barriers, regulatory ideas of borders and racialized divisions of space, concentration and refugee camps, policies of incarceration and asylumization of sexual and gender dissent, land grabbing and land disputes, the irreversible consequences of environmental racism — the aftermath, in short, of a world in agony. Or rather, of certain impossible worlds that cohabit (in) the world. Physical and symbolic places that have been seized as spaces of expropriation and destruction for much longer and more rapidly than others, and which are nevertheless places of resistance and fabulation. I am referring to Lake Atitlán, surrounded by three volcanoes and countless layers of time — Mayan time, colonial time (still so alive), the repressive time of the Guatemalan state and society, the time of extractivist neoliberalism — and which serves as setting and protagonist for Manuel Chavajay’s Oq Ximtali — a choreography of fishermen’s boats in synchronized movement, generating an unstable quasi-perfect circle. These impossible worlds are also found in the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land, whose Mount Roraima shines in multicolor on Carmézia Emiliano’s canvases, despite the illegal invasion and mining that threaten life in the region with pollution and lead poisoning; in the places of permanent exile, of which Mounira Al Solh tells us; in the bars of and for lesbian women running in downtown São Paulo, photographed by Rosa Gauditano in the 1970s, in the midst of the military dictatorship; it also refers to the architectural and abstract spaces of black compositional thought, as defined by Torkwase Dyson; to the spaces of

17 16

and Marcelo Ribeiro. ECO-Pós, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, n. 3, pp. 12-33, 2020, p. 24.

8/ Edimilson de Almeida Pereira, Um corpo à deriva. Juiz de Fora: Macondo, 2020, p. 147.

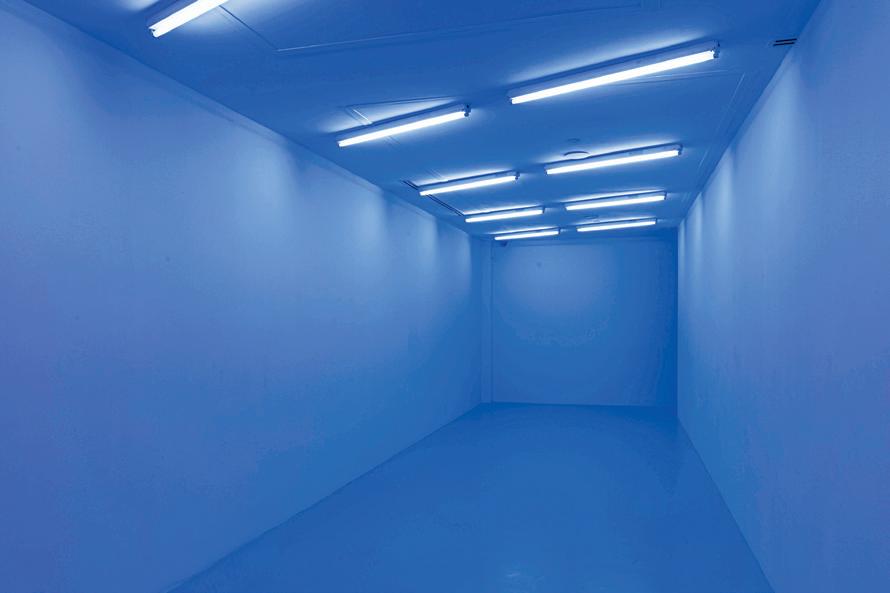

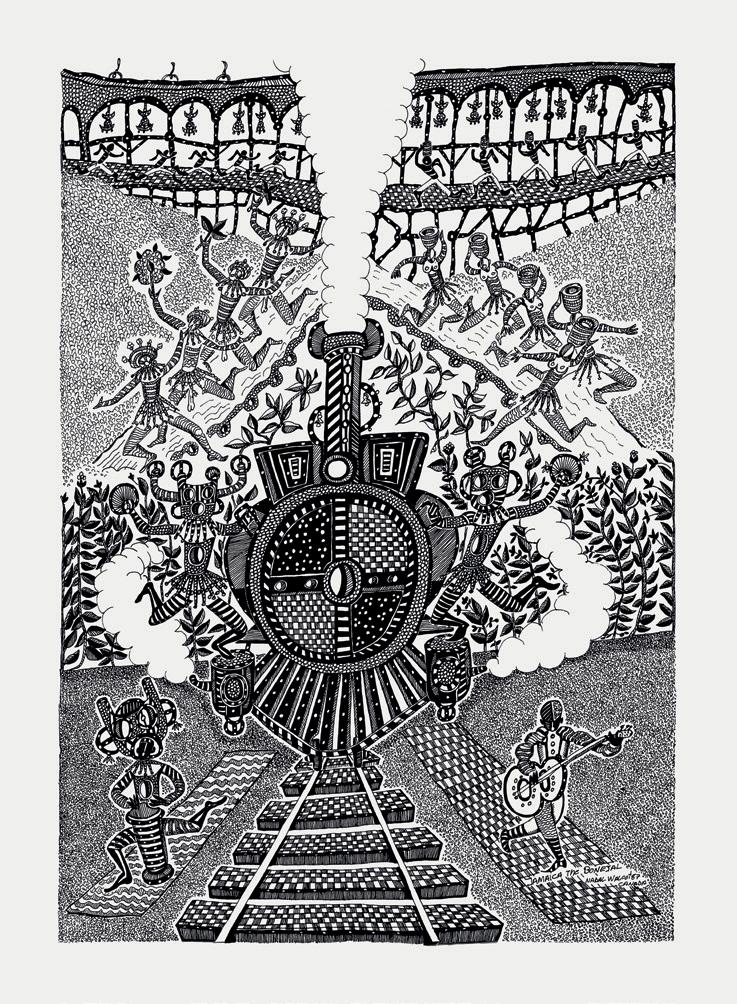

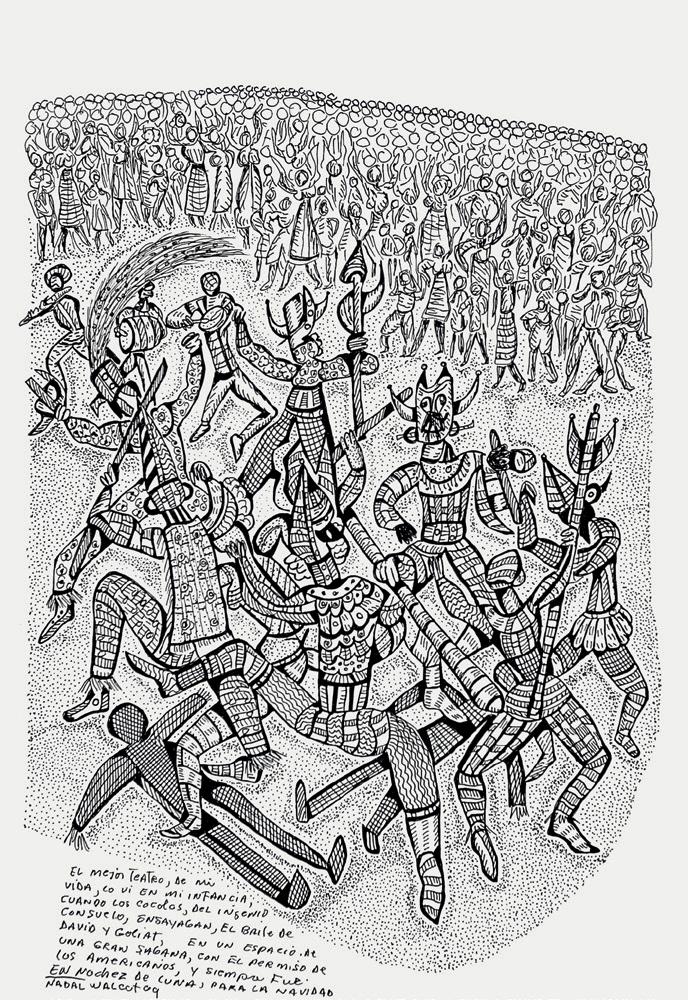

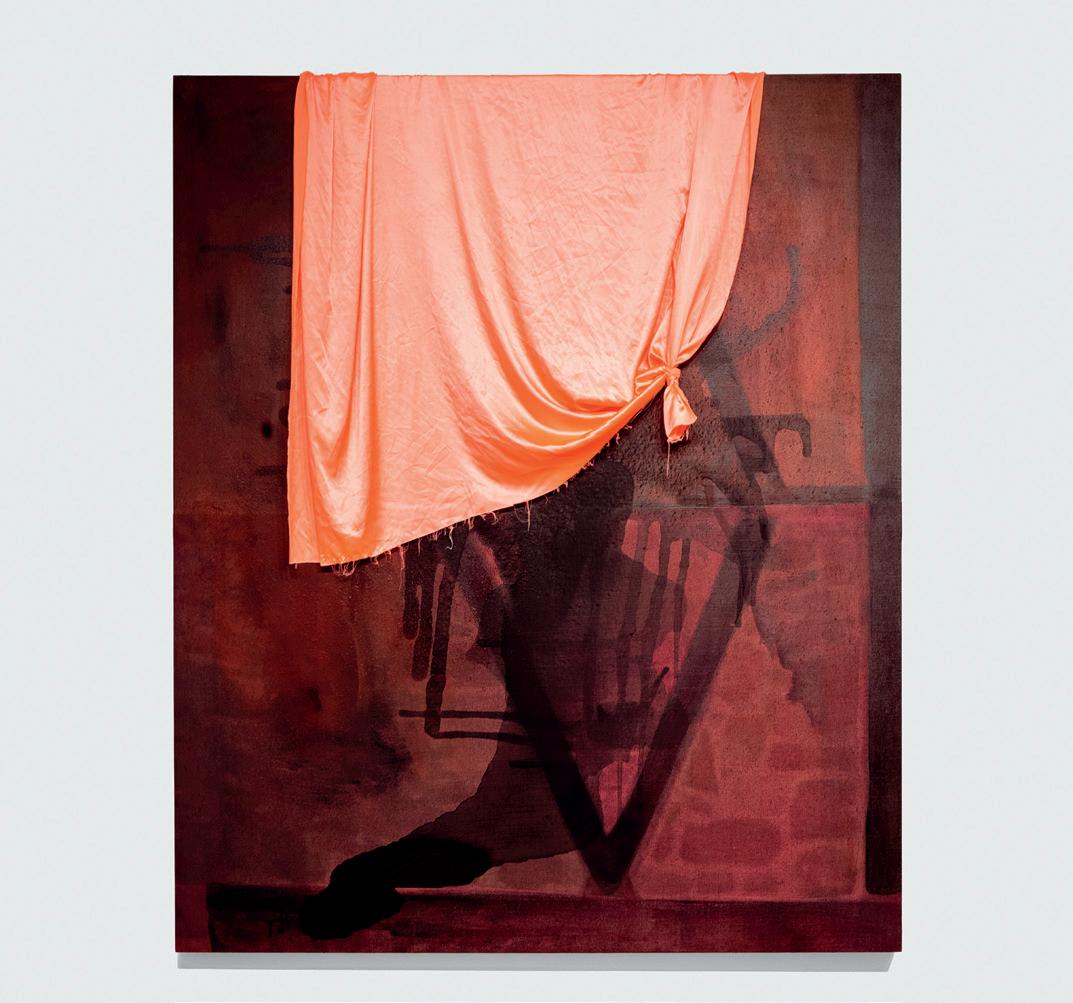

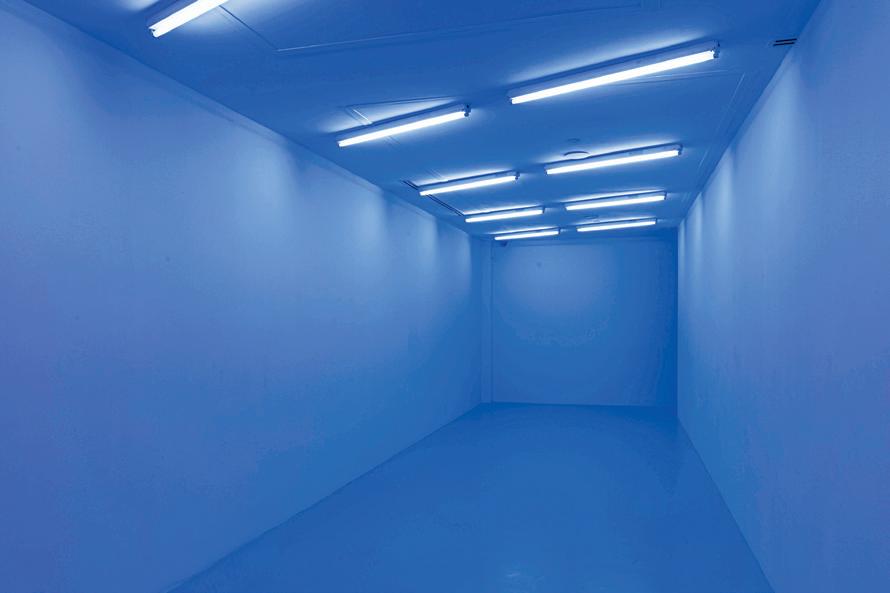

surveillance and incarceration, metaphorized by Kapwani Kiwanga in pink-blue; to the somatizations arising from the trauma of patrolling and death that lurk along migratory crossing routes, which Guadalupe Maravilla reminds us of. Or Deborah Azinger’s abstract landscapes, composed of curly hair and the blues of a non-idyllic Caribbean; the sugar plantations of the Dominican Republic, reimagined by Nadal Walcot in drawings where train tracks meet workers, dances, and fantastic beings; to the cotton fields and their role in British colonial control over Egypt, to which Anna Boghiguian’s Woven Winds — The Making of an Economy — Costly Commodities refers.

This impossible cartography, where a good part of the artistic proposals that embody the 35th Bienal de São Paulo are located, is not the result of an expansive curatorial movement, nor of an encyclopedic search through the world’s eviction rooms.9 Nor is it a residence, although many of the participants in this Bienal come from this southern region of the world, the so-called Global South — a concept that, devoid of an analysis of raciality10 as the ordering principle of the inequities that underlie modernity, ends up concealing irreconcilable “internal” inequalities, making it too broad.

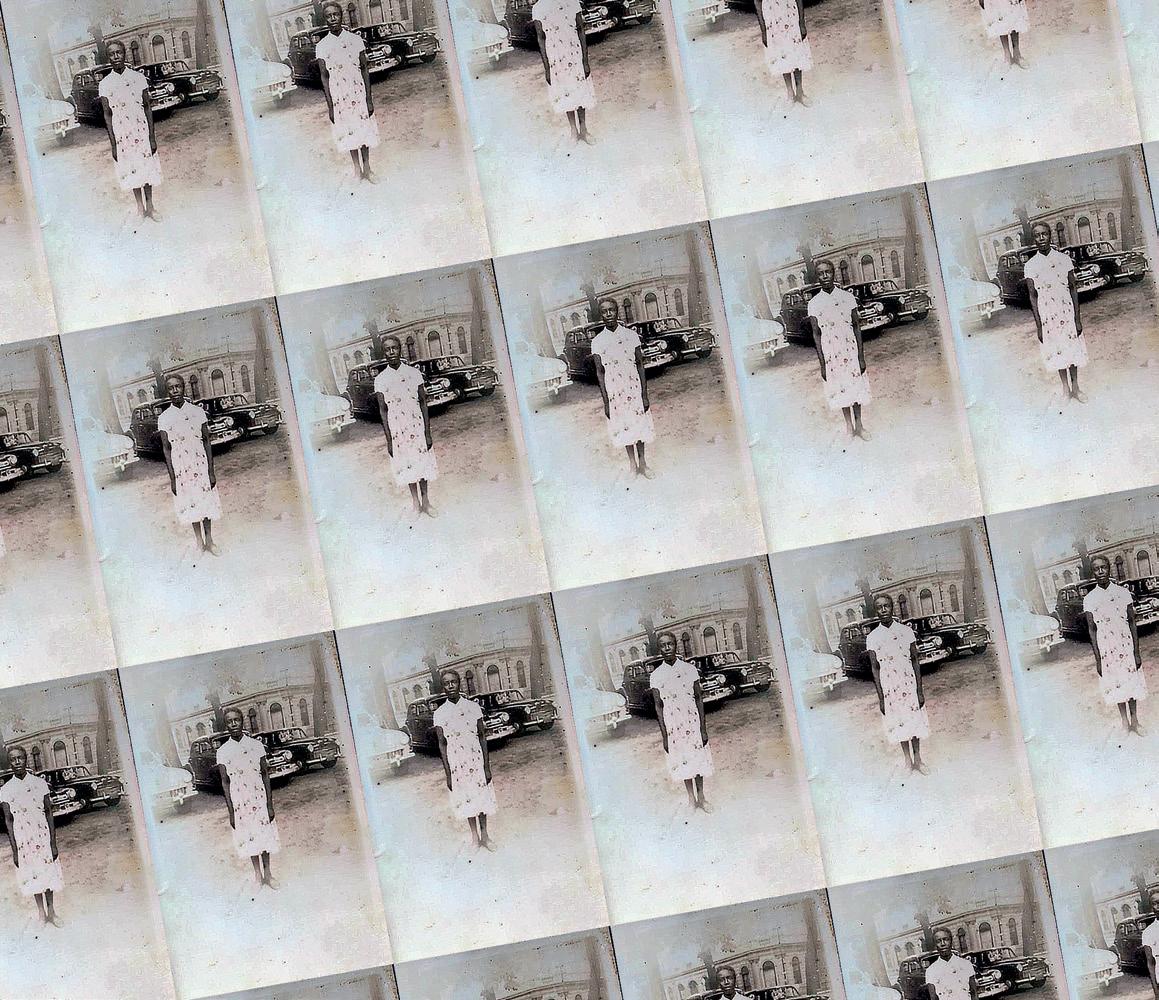

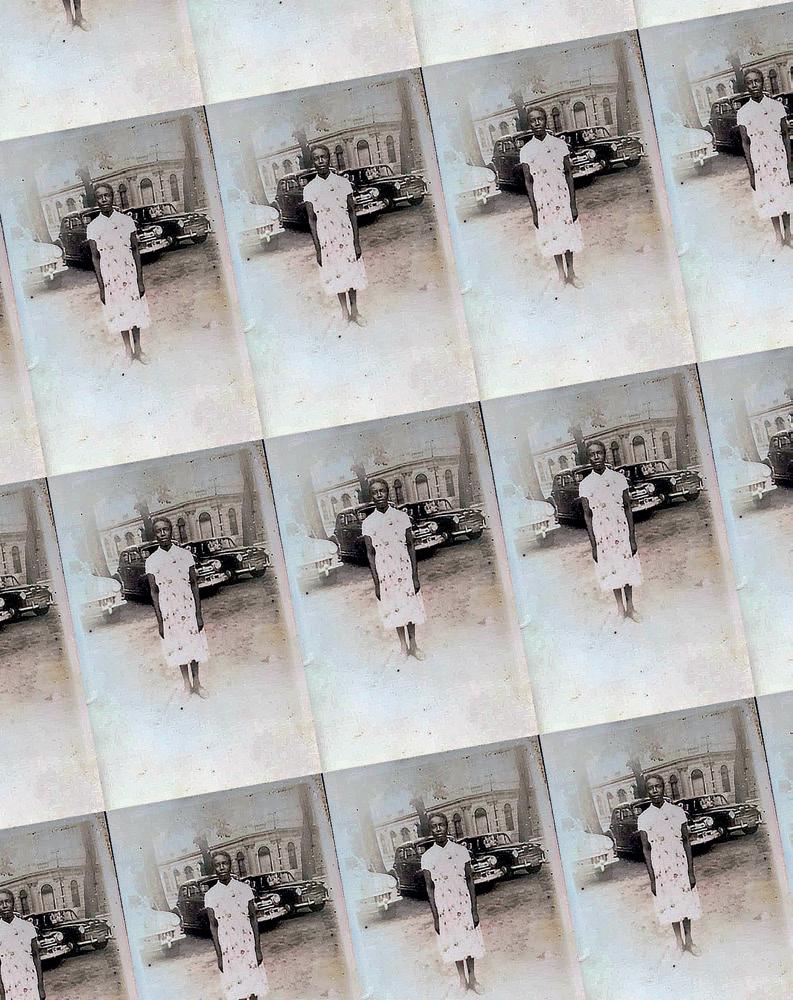

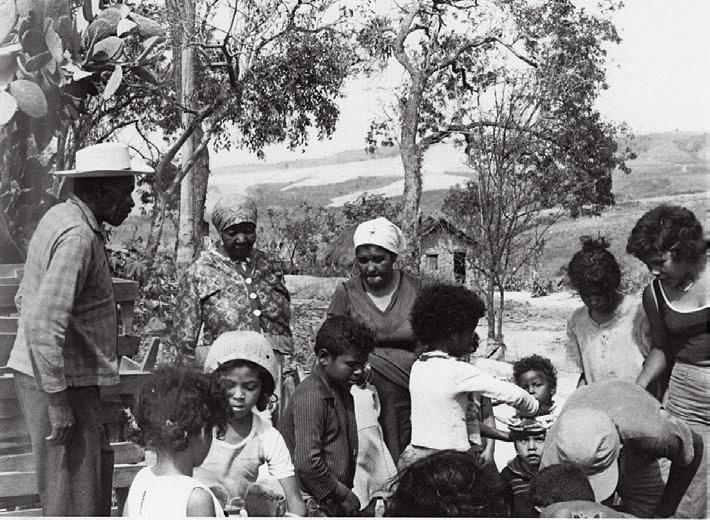

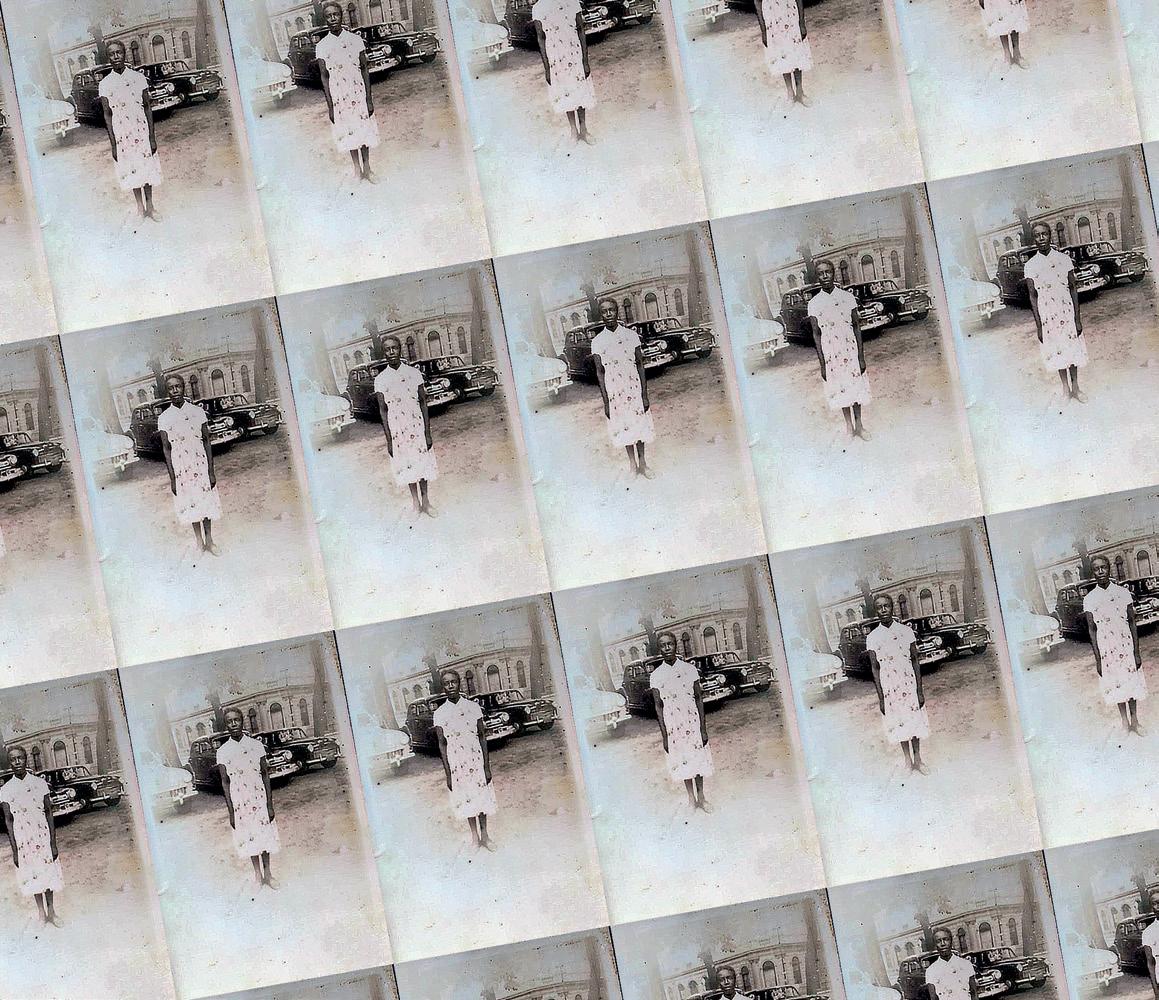

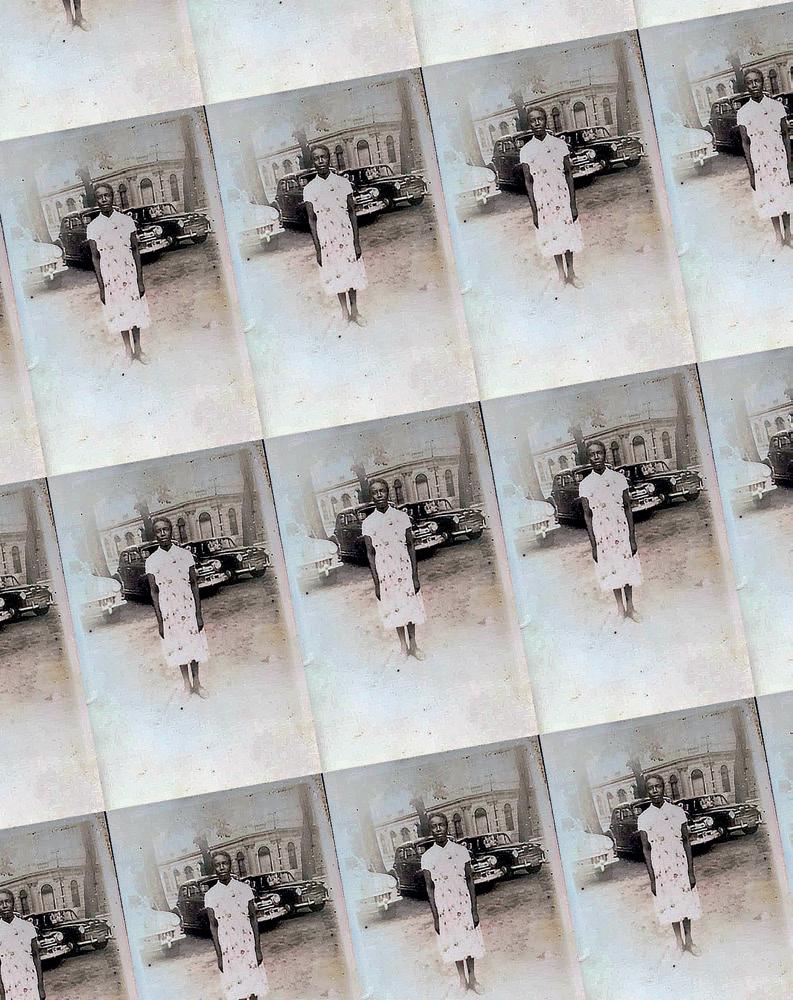

These impossible spaces to which we refer are located, rather, in the native, existential, spiritual, and ancestral territories that find ways to choreograph the impossible in which they live, conceiving their own instruments, movements, and languages. Territories that are located in street protests, on their corners and crossroads — and which take place at the encounter between written language and visual language in the most diverse ways and geographies: in the more than 30,000 images of the Zumví — Arquivo Afro Fotográfico, a collection that holds the work of Lázaro Roberto, Rogério Santos, Aldemar Marques,

9/ Carolina Maria de Jesus (1960), Quarto de despejo: diário de uma favelada. 10. ed. São Paulo: Ática, 2019.

10/ Sueli Carneiro, Dispositivo de racialidade: a construção do outro como não ser como fundamento do ser. São Paulo: Zahar, 2023; Denise Ferreira da Silva, Homo Modernus: Para uma ideia global de raça, trans. Jess Oliveira and Pedro Daher. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2022.

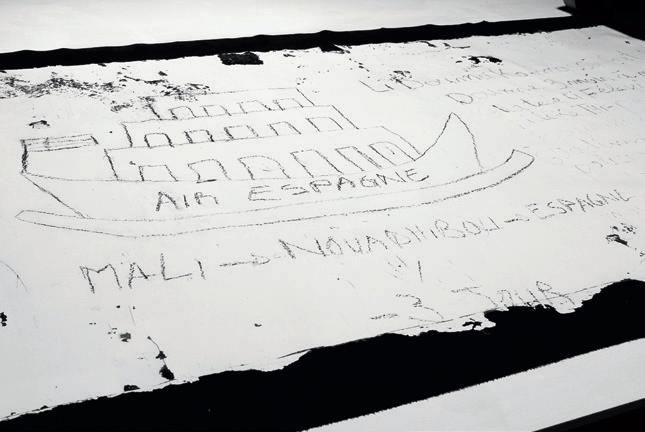

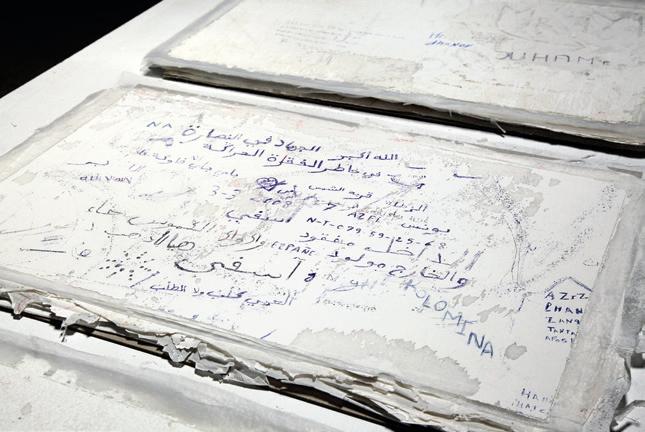

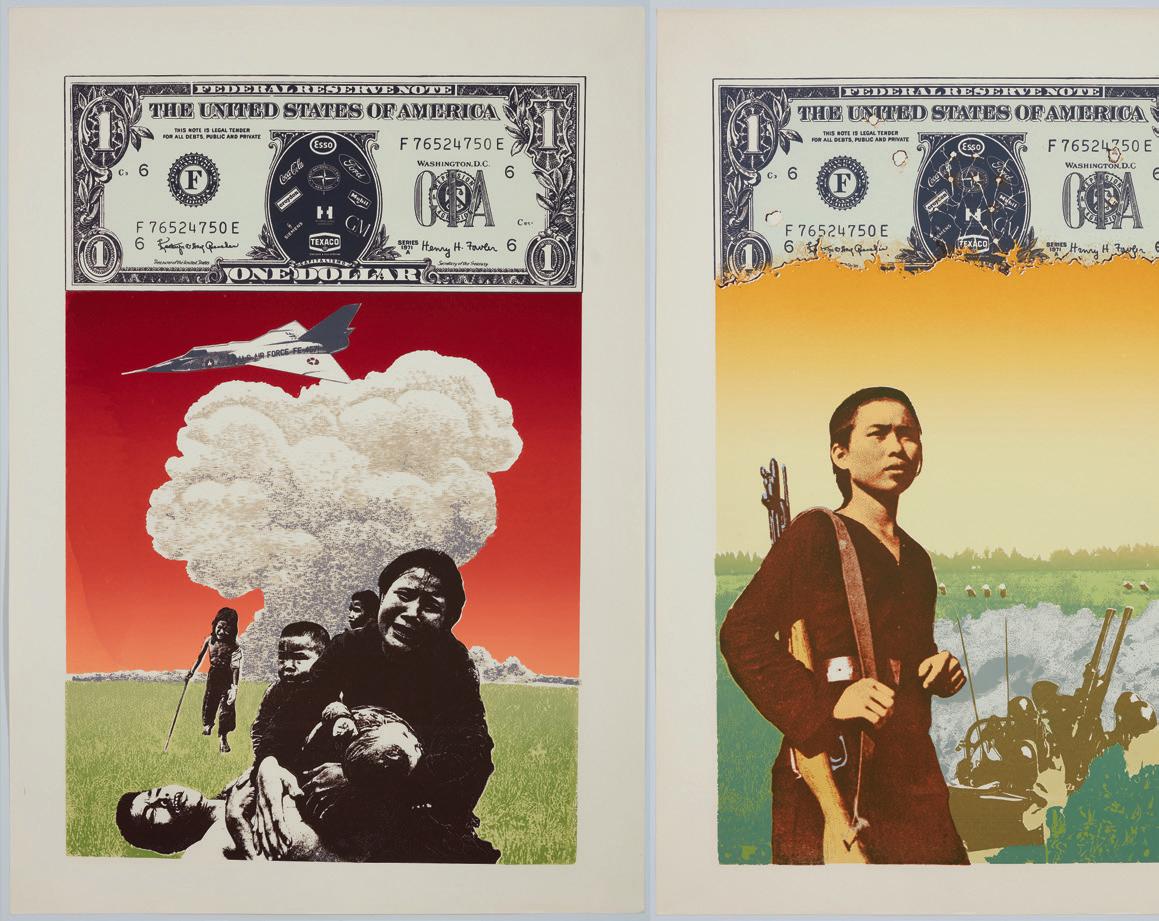

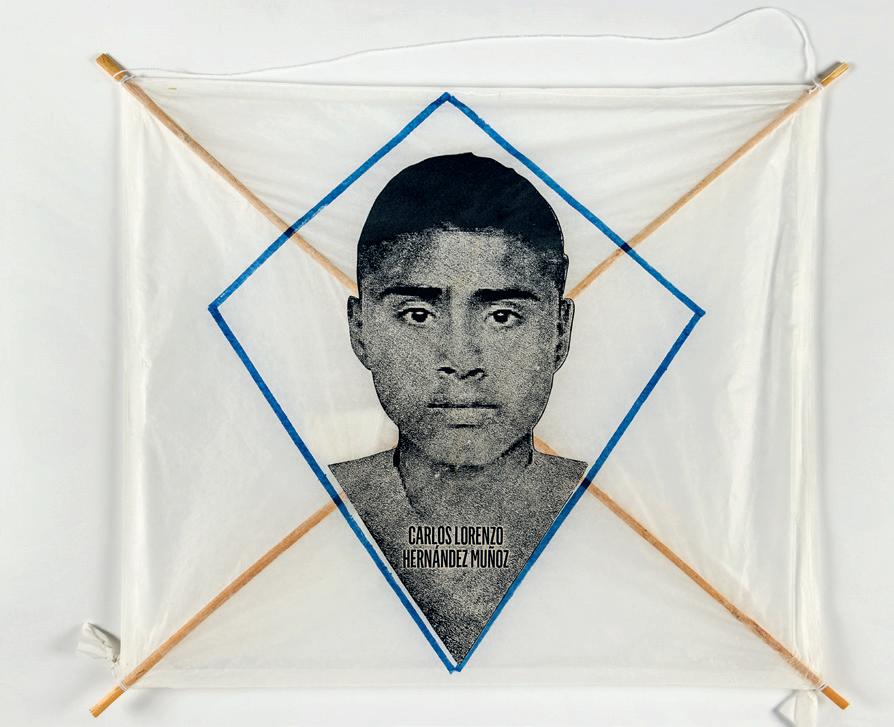

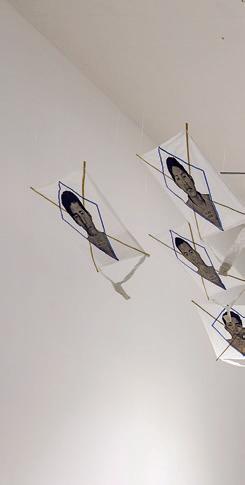

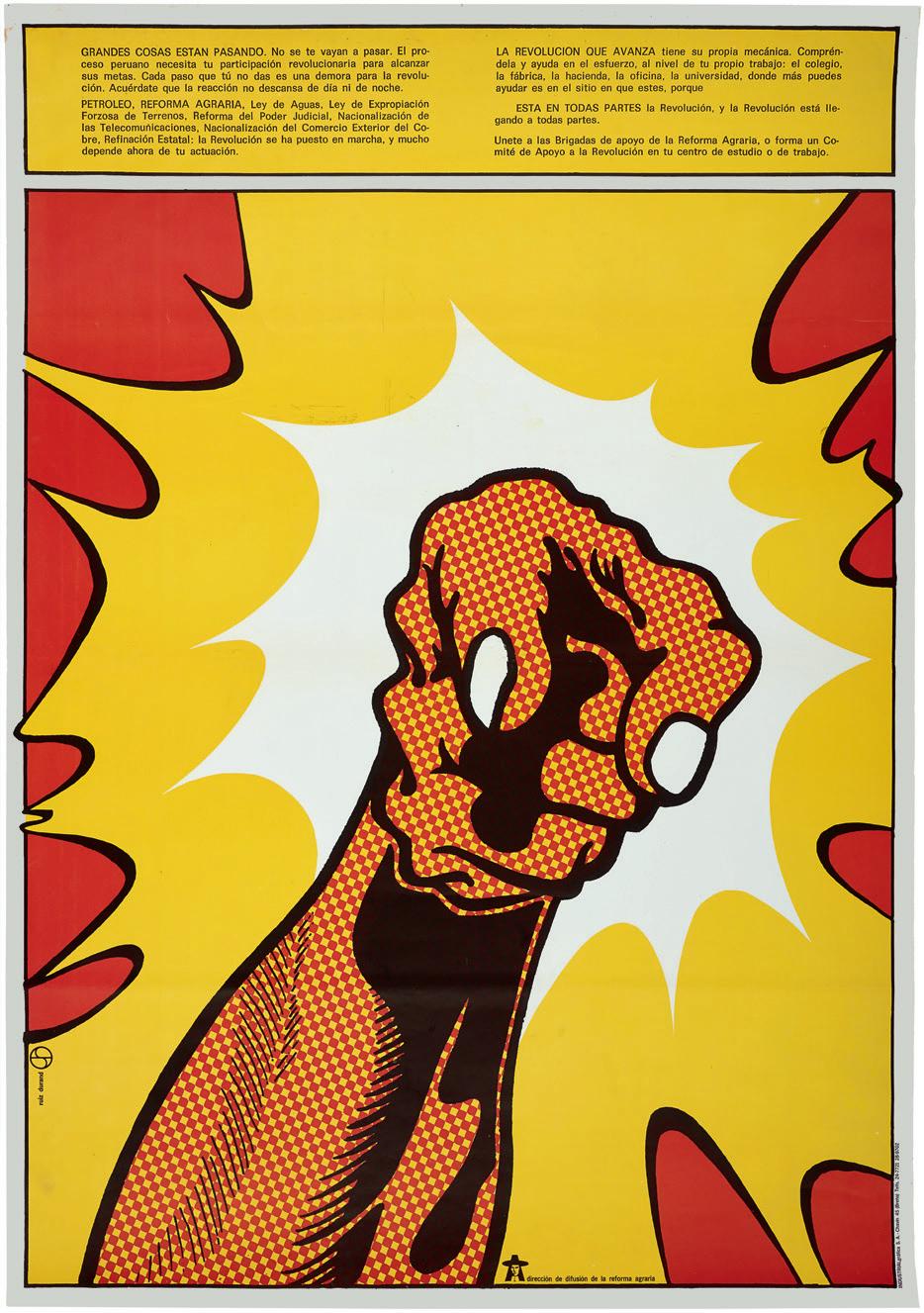

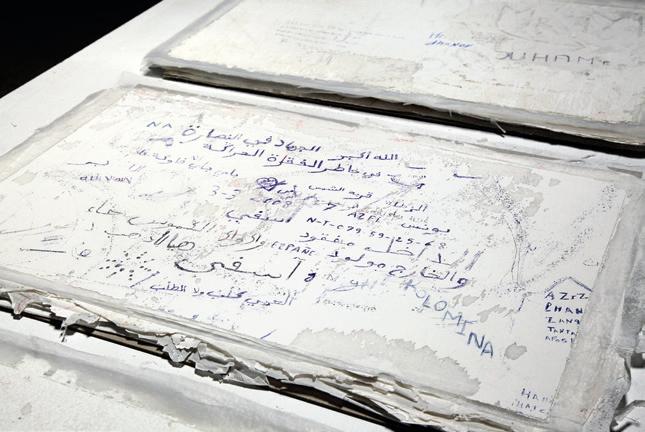

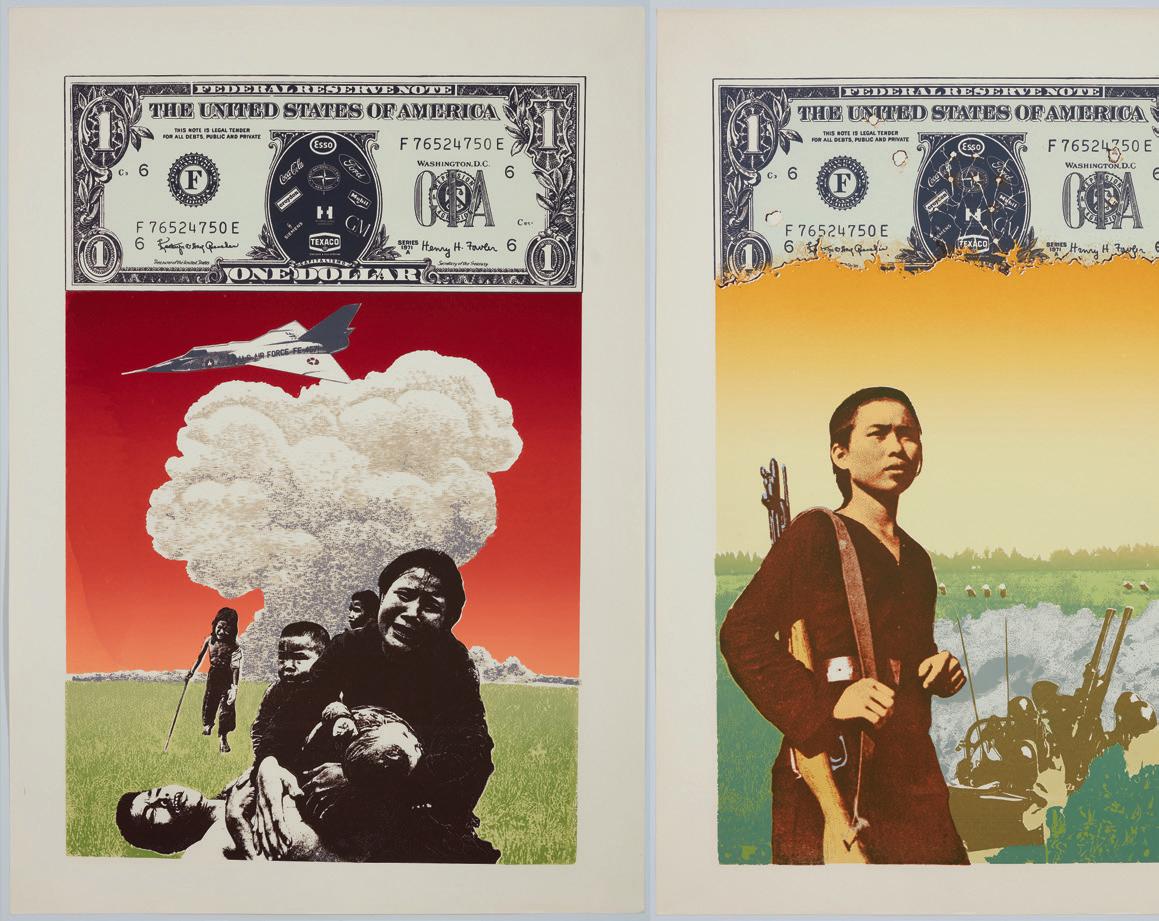

Jônatas Conceição, Geremias Mendes, Lúcio Guerreira, and Raimundo Monteiro, black photographers active in Bahia since 1980; in the posters of the Taller NN in Peru in the 1980s; in Taller 4 Rojo, in the midst of the Colombian armed conflict of the 1970s; in the visual activism of Taller de Gráfica Popular and its collective creative processes, in Mexico in the 1940s; in the fabrics and street actions of Colectivo Ayllu; in the banners and lambe-lambes of Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho — MSTC.

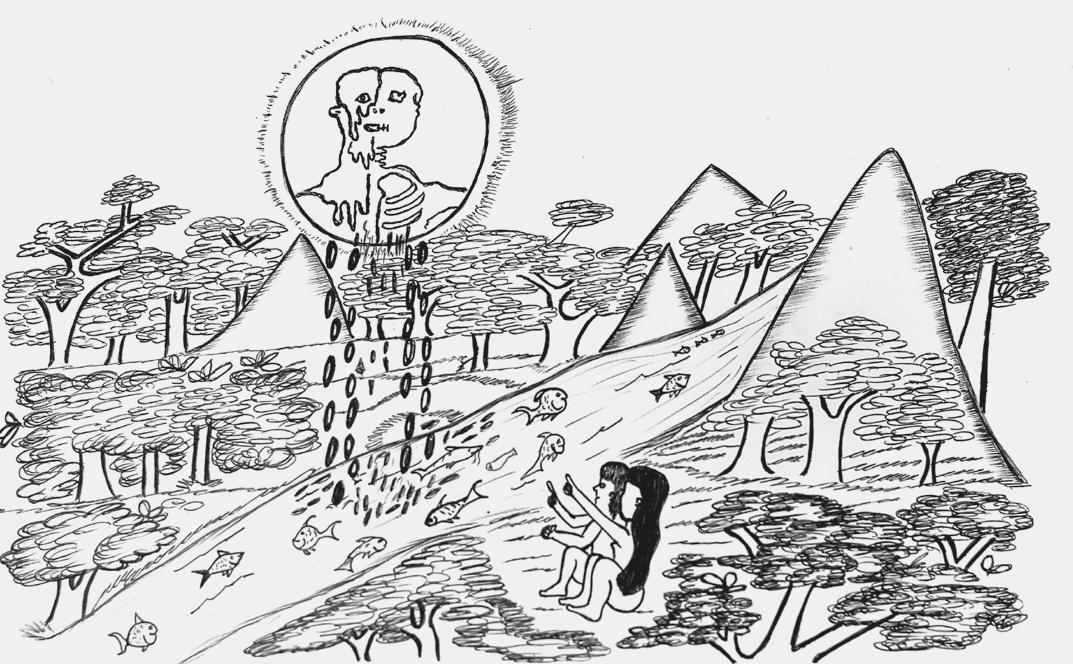

Impossible territories extend to the villages and their enunciations of florestania (or “forest citizenship”), a possibility of citizen life within the forest, as proposed by Ailton Krenak,11 and can be inferred from the fantastic and “erotic” drawings by Gabriel Gentil Tukano; the filmography of everyday practices made by Aida Harika Yanomami, Edmar Tokorino Yanomami, and Roseane Yariana Yanomami; as well as the Floresta de infinitos [Forest of Infinities], populated by Nkisi, orixás, caboclos, animals, and enchanted humans, as proposed by Ayrson Heráclito and Tiganá Santana. Territories that are consistent with the quilombo, simultaneously, ethical space and operation, “the continuity of life, the act of creating a happy moment, even when the enemy is powerful. A possibility in the days of destruction,”12 in Beatriz Nascimento’s apt definition — and one that resonates in the living archive of Quilombo Cafundó.

These choreographies of the impossible take place, themselves, in an impossible territory called Brazil. And in an equally impossible context — in the four years preceding the 35th Bienal, 570 Yanomami children were killed by mercury poisoning, malnutrition, and hunger in this country, according to data from the Ministry of Indigenous

12/ Maria Beatriz Nascimento, Beatriz Nascimento, quilombola e intelectual: possibilidade nos dias de destruição, ed. União dos Colectivos Pan-Africanistas (UCPA). São Paulo: Filhos da África, 2018, p. 190.

11/ Ailton Krenak, Futuro ancestral, ed. Rita Carelli. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2022.

Peoples.13 This, among the many and innumerable impossibilities that occur on a daily basis in this place, is especially shocking due to the re-enactment of the 17th century European invasion — a loop of time that never passed. As Gilberto Gil sings: “here is the end of the world”.14

The urgency and persistence of these issues have led these choreographies of the impossible to highlight a series of artists, collectives, historical figures, collections, poets, and social organizations, driven by the radical possibility, as Denise Ferreira da Silva proposes, of “thinking the world Otherwise.”15 All of them are involved in movements of creation of between-spaces and between-times that, though ephemeral, are fertile to the practice of generation and transmutation of life. They meet “the ethical mandate to challenge our thinking, to free our imagination and to welcome the end of the world as we know it, that is, decolonization, which is the only adequate name for justice,”16 also in Denise’s terms.

●●●

As if in a choreography of returns, the works presented at this 35th Bienal were conceived between the 17th century and 2023 — although the propositions and provocations they allow, in dialogue and relationship, exceed and invalidate such dates. And they are expressed in multiple languages, moving between cinema, visual arts, music, ritual art, dance, and poetry, among others that barely fit into the more or less habitual categories.

13/ Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, “Presidente Lula convoca ação emergencial interministerial na TI Yanomami," Jan. 20, 2023. Available at: www.gov.br/povosindigenas/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2023/01/presidente-lula-convoca-acao-emergencial-interministerial-na-ti-yanomami. Accessed: July 7, 2023.

14/ “Marginália II”, song by Gilberto Gil and Torquato Neto, from the album Gilberto Gil, 1968, São Paulo, Philips Records.

15/ Denise Ferreira da Silva, op. cit.

16/ Pensamento negro radical: antologia de ensaios. São Paulo: Crocodilo, 2021.

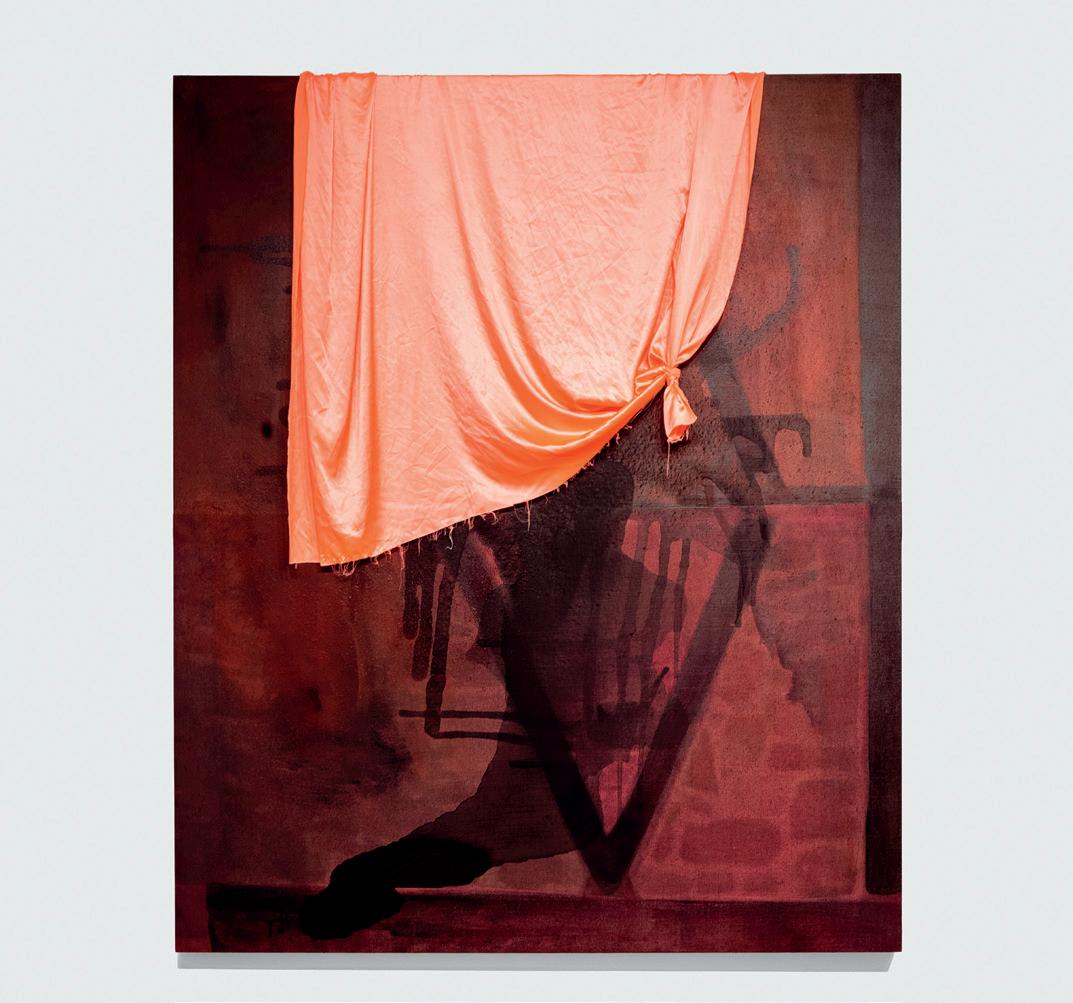

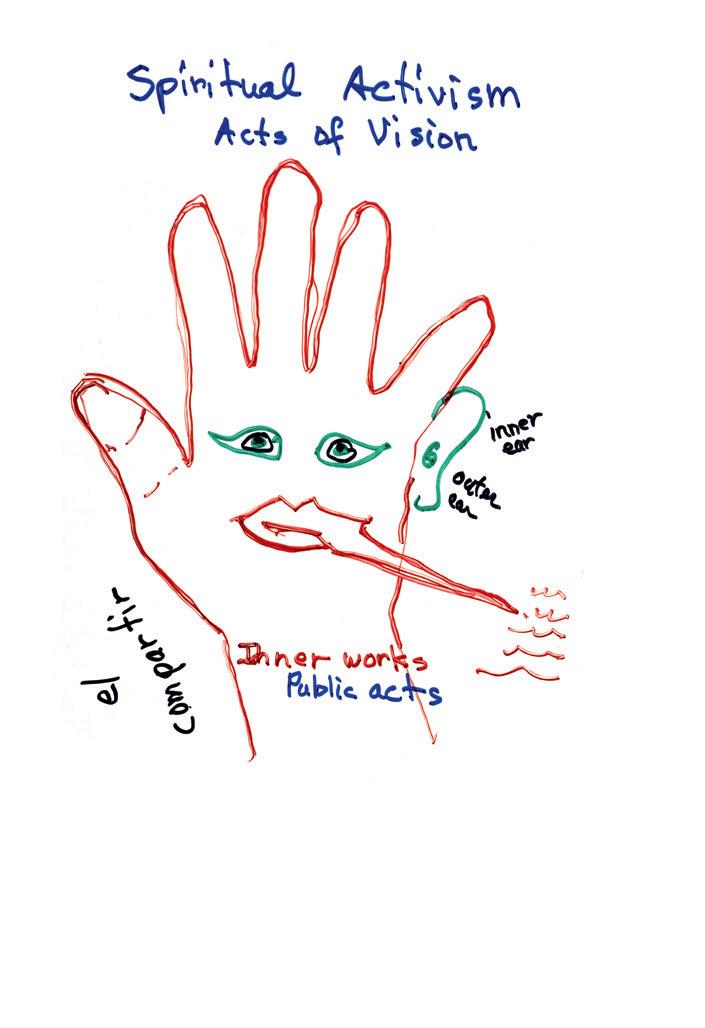

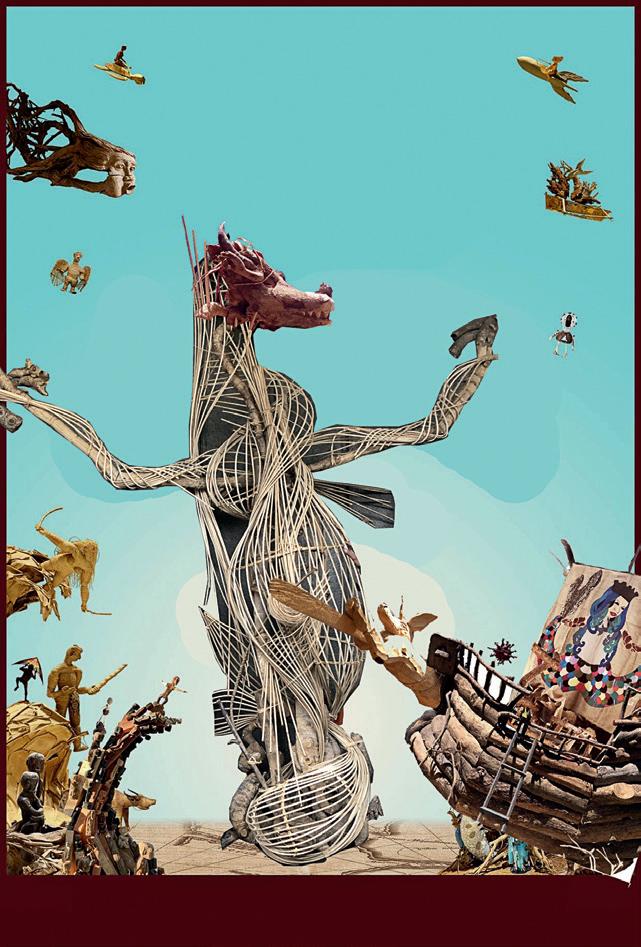

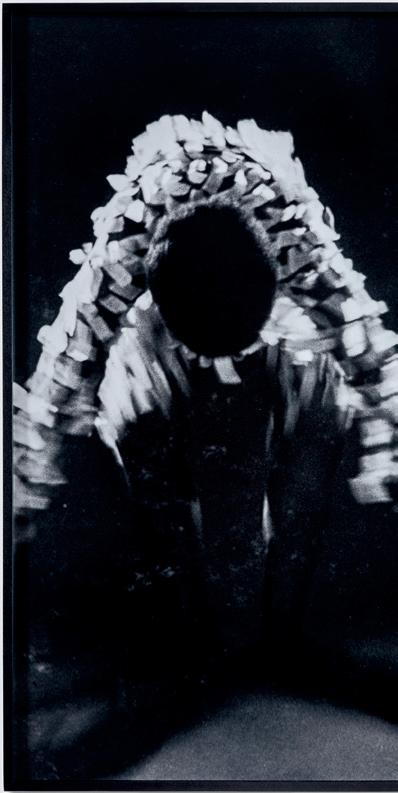

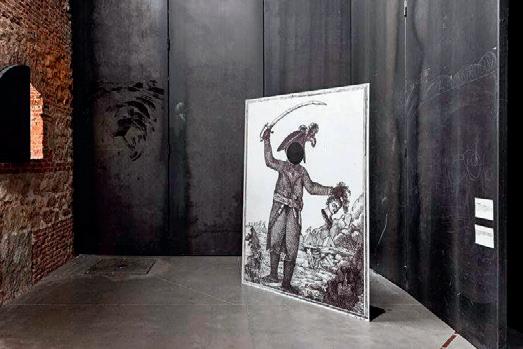

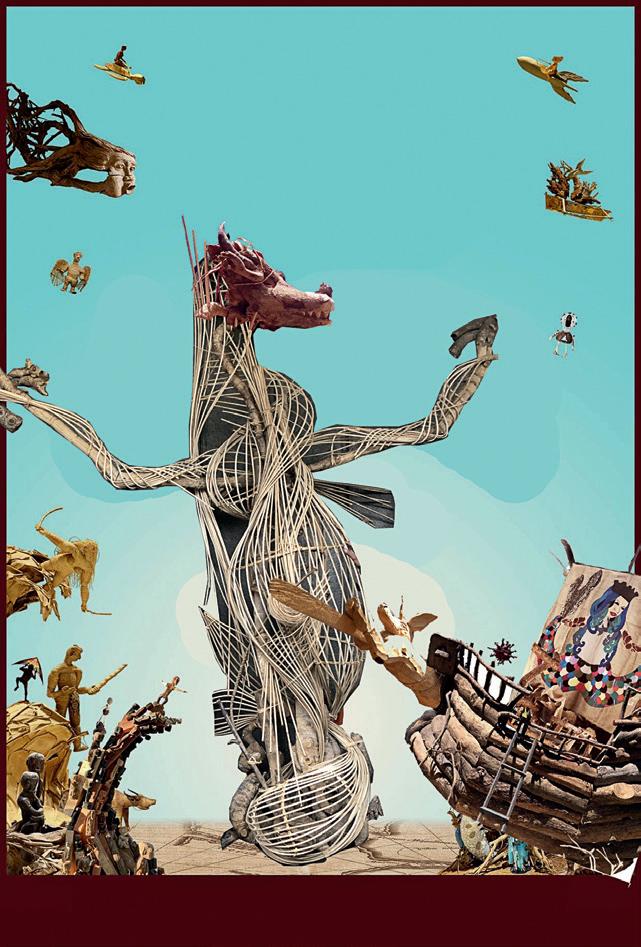

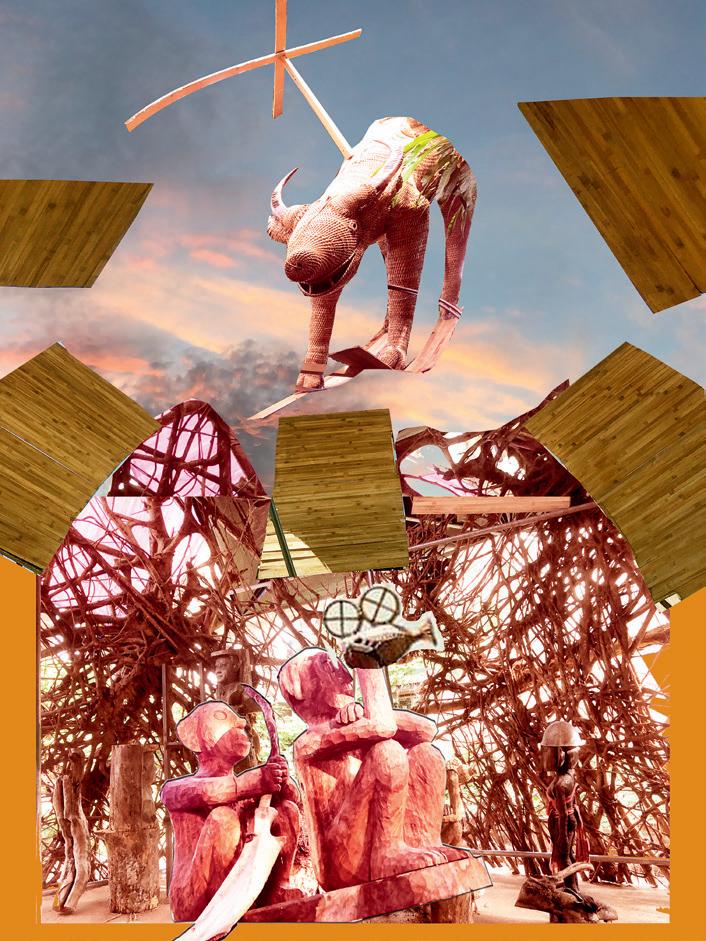

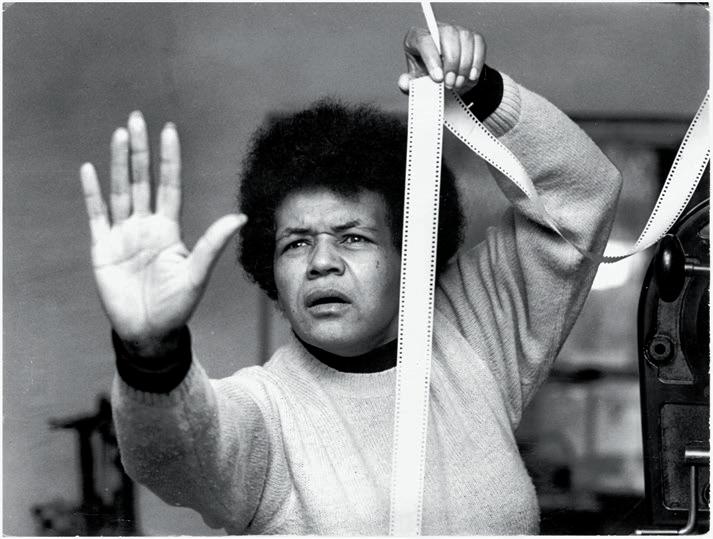

This ensemble makes it possible to highlight, I believe, the intense circulation between languages, emphasizing formal experimentations that mix up the boundaries, for example, between visual arts, archives, and practices of resistance. How can we fail to recall Marlon Riggs’s stage-cinema, which dared to recite love poems between queer black people and people living with hiv, in the 1980s? Or Kamal Aljafari’s “camera of the dispossessed,” expanding the possibility of filmmaking by using unlikely footage shot by security cameras, recorded by the Israeli army or commissioned by state advertising agencies? The expanded ways of dialoguing between different languages can also be found in Kidlat Tahimik’s “cinematographic” installations, where the stories of Igpupiara and Syokoy, beings from indigenous-Brazilian and Filipino mythologies, are told through assemblages that are very similar to a film script. Filmmakers such as Sarah Maldoror, Amos Gitaï, Leilah Weinraub, and Trinh T. Minh-ha; poets such as Gloria Anzaldúa, Ricardo Aleixo, and Raquel Lima — for whom the fields of the visual arts, the body, and writing go hand in hand — are other examples of practices that develop in circulation. Such diversity guided the curatorial proposal to arrange the works in expographic neighborhoods that privilege sensitive affinities, connections of a more properly poetic order, rather than guided by approximations in thematic nuclei, by language types, or formal or material properties. Nor by chronological orientation. They are arrangements that allow us to highlight other genealogies of the contemporary, braids that have not been incorporated or subsumed into the constitutive teleology of art history and that allow the encounter, for instance, of the bindings, twists and body-canvasses of Sonia Gomes’s sculptural vocabulary, the inextricable weaves of ropes and fabrics of Judith Scott’s dense compositions, with the lines, rods, poetry and dance amalgamated in Julien Creuzet’s installations. For this reason, they decline in the configuration of an exhibition space that is averse to linearity, composed in refrains, unforeseen reappearances; without a predetermined path or an ideal sense of direction.

“Time, in its spiral dynamics,” says Leda, “can only be conceived by space or in the spatiality of the gap that

19 18

the spinning body occupies. Time and space thus become mutually mirrored images”.17

The architectural design for the 35th Bienal, developed in partnership with Vão, therefore favored the construction of a dynamic between wide and delimited spaces, alternating movements of contraction and opening, systoles and diastoles. The architectural design is fundamentally inspired by the curvilinear forms of the building — the mezzanine and central void. The contours of these spaces, when summed, result in an architectural body that seeks to disobey the structuring orthogonality of the Pavilion, functioning in a reversed manner on each floor. On one floor, the periphery external to the hollow space is filled with closed rooms; on the other, the central space is occupied by closed galleries, while its surroundings open up into a wide, non-sectioned space.

We also seek to extend this concept to the places of coexistence and encounter that permeate the space of the choreographies of the impossible. Projects of a gregarious nature, which operate equally as an installation, an exhibition place, and a space that is open to encounters — such as Assay, proposed by the duo Nadir and Soumeya; the re/dis/assemblable tetrahedrons that make up Metaphysics of the Elements — The Studio, by Denise Ferreira da Silva; Parliament of Ghosts, by Ibrahim Mahama; and the Sauna lésbica [Lesbian Sauna], by Malu Avelar with Ana Paula Mathias, Anna Turra, Bárbara Esmenia, and Marta Supernova — are examples of these diastoles that spread between the exhibition floors.

The same can be said of the presence of the Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho — mstc [the Kitchen of the 9 de Julho Occupation — mstc], from its spiral forms and collective technologies of governance, gestated in the homonymous building occupied by the Movimento dos Sem Teto do Centro (mstc) housing movement, in São Paulo — which creates an in-between space in which food, street visual culture, the debate-in-practice of the right to the city and to quality food, resulting from a responsible production chain, are merged.

Such curatorial proposals stem from an understanding of our group — composed of my colleagues Diane Lima, Grada Kilomba, Manuel Borja-Villel, and myself — in dialogue with the curatorial assistants Sylvia Monasterios and Tarcisio Almeida, as an attempt to disarrange the vertical structures of power and their imperative modes of operation.

From this encounter is derived a conception of the choreographies of the impossible as a Bienal — in the form of exhibitions, publications, artistic residencies, public debate programs, performative actions, mediation and educational actions, collaborative networks with autonomous spaces for art and thought — that is also a platform for practices of redistribution, a laboratory open to experimentation, to collective governance exercises. A crossroads, in Leda Maria Martins’ terms, again:

the possibility of interpreting the systemic and epistemic circulation that emerges from interand transcultural processes, in which performative practices, conceptions and cosmovisions, philosophical and metaphysical principles, diverse types of knowledge, are confronted and intertwined — not always amicably.18

Not always amicably, the choreographies of the impossible can, I want to believe, shake the ground on which this collapsing world rests. By changing its rhythm, by reversing its cadence, these crossroads of time accomplish the impossible: they bring back to the dance the all-that-can-be of times not yet lived.

translated from Portuguese by philip somervell

17/ Leda Maria Martins, op. cit., p. 134.

18/ Id., ibid., p. 51.

six moments for another time manuel borja-villel

1. Cairo. 14 March 1932. At the request of King Fuad I of Egypt, an important international congress is organized with the aim of discussing and documenting the sound traditions of the Arab world. After gaining independence from the United Kingdom in 1922, the Egyptian government yearns to assert its identity by showing a history that differs from the English and serves as a modernizing example for its citizens. The convention was attended by scholars and musicians from the Maghreb and the Middle East, such as Muhammad Fathi, Ali Al-Darwish, Rauf Yekta Bey and Mohammed Cherif, as well as European composers such as Béla Bartók and Paul Hindemith.

One of the most important milestones of the meeting was the request to restrict improvisation and standardize the tuning system, which was not tempered. The government representative to the congress, Muhammad Fathi, recommended that musical groups in the area use Western instruments, which he believed possessed superior expressive qualities. If Egyptian vernacular music had produced what a British commentator described as “terrible sounds,” harmony was now guaranteed. The constant reinvention of rules was also limited, favoring standardization and state control. The narrative was changed, what was national was reclaimed, but the framework of Western thinking was maintained. This allowed participation on the condition that it was carried out within pre-established and supposedly scientific parameters of ordering and classification — and also of possession and destruction.1

We know that decolonial processes have not always been successful and can even lead to counter-revolutionary periods. Knowing why they failed, analyzing their causes and consequences, is essential. Hence the relevance of what the Moroccan thinker Abdelkebir Khatibi (1938-2009) called “double critique,” that is to say, the continuous questioning of colonial reason and our position in relation to it.

The overturning of mastership, subversion

itself, depends on this decisive act of turning infinitely against one's own foundations, one's origins, those origins undermined by the whole history of theology, charisma, and patriarchy, if one can characterize thus the structural and permanent givens of this Arab world. It is this abyss, this nonknowledge of our decadence and dependence that should be brought to light, named in its destruction and transformation beyond its possibilities somehow.2

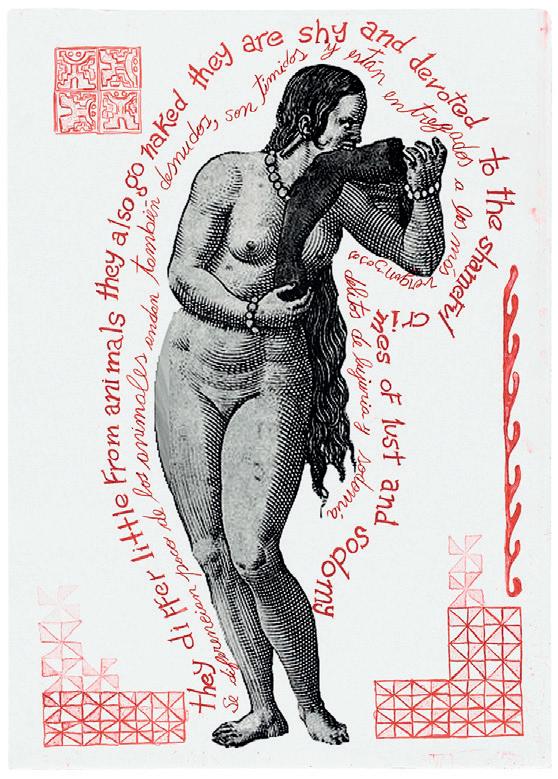

In an article entitled “What it Means to Curate for My Native American Community”, Kiowa-Muscogee-Seminole curator and activist Tahnee Ahtone wonders about the way in which indigenous cultures have been introduced into American museums.3 She does not doubt the good intentions of her colleagues. However, she questions whether there was any real will to change the structures. Ahtone laments that indigenous curators are often forced to develop their careers in a system that is alien to the customs and ways of doing things in their communities. When the alternative or independent is used only as a style, it does not designate anything outside mainstream culture. A visit to a few art fairs, exhibitions, and museums confirms this. Racism is denounced, raciality is vindicated, but this critique tends to refer to established patterns, which do not merely question what makes racism possible, but revalidate it. However, this does not imply a paradigm shift, because domination remains intact. When certain approaches become fashionable, when a work of art becomes a product apart from the context in which it was created, when we fail to understand that we are all part of a shared ecosystem in which nothing is ours, and when the subject-object separation is ratified, the master-slave

2/ Abdelkebir Khatibi, Plural Maghreb: Writings on Postcolonialism (1974). London: Bloomsbury Academy, 2019, pp. 26-27.

3/ Tahnee Ahtone, “What it Means to Curate for My Native American Community,” Hyperallergic, Dec. 2021. Available at: hyperallergic. com/702775/what-it-means-to-curate-for-my-native-american-community/. Accessed: Jul. 2, 2023.

21 20

1/ I thank Philip Rizk for sharing his research on this conference with me.

relationship remains active, regardless of whether the images depicted are African-American or indigenous. This entails transforming history, not just remembering it, and requires the reformulation of institutional governance, and also understanding the role of the artist in each society while recognizing that we cannot talk about art from a modern perspective, that is, as if it were a universal and infinitely interchangeable object. We must not forget that in some indigenous languages, such as the Mayan, the word “art” does not even exist. To refer to artistic practice, they use other terms that have to do with healing, the biosphere, tradition, or with something that is done with the hands, and which apply to things that belong to everyone and are therefore inseparable from their community and territory. Likewise, for Yoruba cultures, aesthetic delight is not separated from the functionality of their songs or dances, their crafts, sculptures, symbolic representations, sciences, or music. As noted by Leda Maria Martins, while the triumph of the economic over the imaginative spirit made the terrible rupture between life and art possible in the West, for the Yoruba, aesthetic pleasure is added to and not disassociated from a fundamental ethical understanding, constitutive of all the qualities of doing/making.4 This involves a radical change with respect to Eurocentric ways of collecting, ordering, exhibiting, and explaining.

2. London. 1 May 1851. The Crystal Palace, the fantastic architecture of Joseph Paxton (1803-1865), is inaugurated in Hyde Park. One can argue that the phenomenon of the great exhibitions began with it, replacing local fairs and overcoming the chaos and the social disturbances they caused. Under the hypnotic gaze of the spectacle, these exhibitions served to regenerate cities and strengthen national pride, building a sense of deceptive unity between unequal classes and groups.

The great exhibitions arose shortly after what was apparently its opposite: the panopticon, which was imposed in the Western prison system from the 18th century onward. The Crystal Palace was an open space, based neither on confinement nor on a unidirectional vision. From the outside one could see what was going on inside; from the inside one could distinguish what was occurring outside. The gaze became omnipresent and external surveillance was no longer essential, since everything was available to everyone. As in prison, control was exercised by the individual over themself.

The spectator observed from a location that was intended to be neutral. Traversed by the single perspective, the bodies did not exist as such, they were transparent. However, this transparency concealed conflict and made it impossible to distinguish the mechanisms through which the propositions were produced, interpreted, and distributed. With modernity, experience ceased to be an irruption of the unknown and became captive to a totalizing general design that caused the loss of relational and performative spheres.

In the cognitive system of many peoples, words are invested with effectiveness and power. They express themselves through circumlocutions, the different sonorities of the voice and the movement of the body. Not only do they represent a thing, but they are also the thing itself. They contain what they evoke. Contrary to modern thought, knowledge is not only kept in libraries, museums, archives or official monuments; instead it is constantly revived and recreated through oral and bodily repertoires, gestures,

4/ Leda Maria Martins, Performances do tempo espiralar: poéticas do corpo-tela. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2021, pp. 70-71.

and habits.5 This performative aspect runs through the works exhibited in choreographies of the impossible In its etymological sense, the noun “choreography” means inscription in space. The Greeks, whose culture was not so much the origin of Western civilization as it was the continuity of a set of knowledges that already existed in Asia and Africa, used two different terms to refer to place: topos and chora. The former responds to an Aristotelian notion that is static and entails the dissociation between agent and space. One can move freely through space, but not leave it, since space is always identical. Chora, on the other hand, is a Platonic concept that entails a dynamic relationship between being and place; there is no separation between one and the other. Both form a dance of encounters and displacements, which teaches us how to relate to what we know and to what we ignore about ourselves and others.

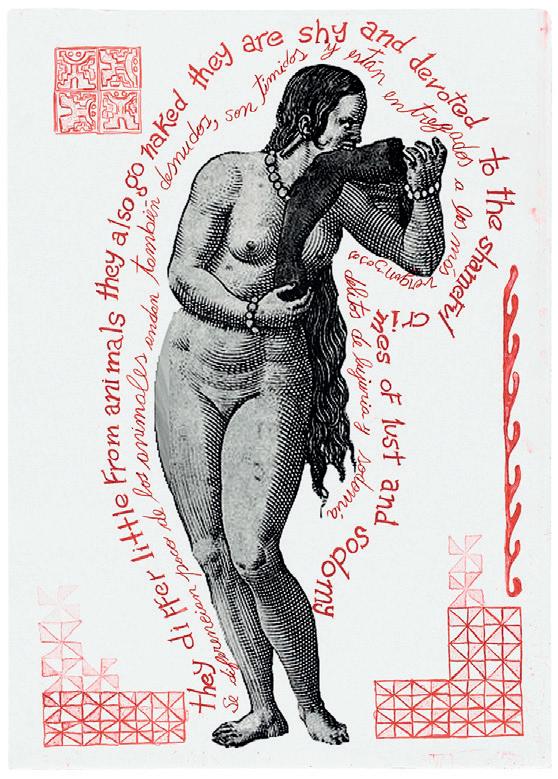

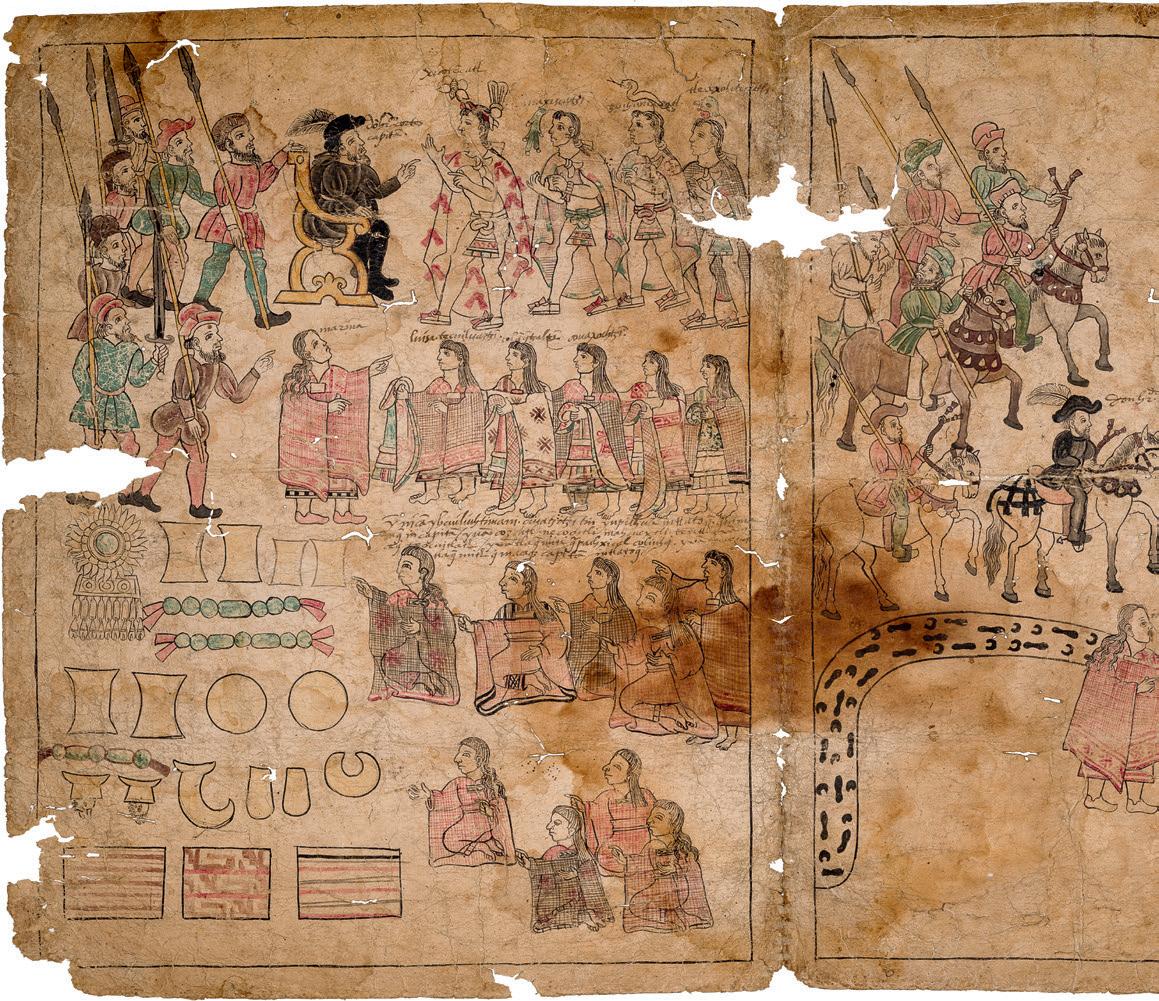

The hegemony of writing over other modes of communication was absolute from the 16th century onwards. Let us mention a remarkable historical coincidence: the publication of Nebrija’s Grammar in Spain in 1492 — the same year the Spaniards arrived in America — was key to transforming language into an instrument of control and conquest. At that time, the newly introduced regulation avoided constant variations and was essential in the attempt to suppress knowledge considered heretical and undesirable by the Europeans.6

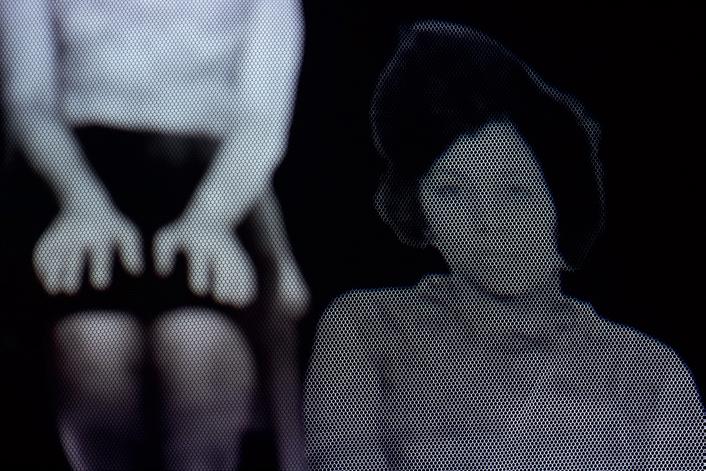

Spelling or graphing knowledge is synonymous with an experience that finds its place in the body in performance and not necessarily in an alphabetically-written language. Many of the participants in the 35th Bienal, such as Tejal Shah, El Niño de Elche, Pauline Baudry and Renate Lorenz, or Ellen Gallagher and Edgar Cleijne, have designed installations that go beyond the binomial white cube/black box. They are constantly transforming, they encourage the conscious mobility of the public and call for a break from the straitjacket of all modern devices, fleeing

5/ Ibid., p. 40.

6/ Ibid., p. 34.

from the transparency and optocentrism characteristic of the “Crystal Palaces.” There is no separation between subject and object. Thus, Gallagher and Cleijne’s “landscapes” in Highway Gothic (2017) are part of a common memory, not experiences external to the human being. Similarly, El Niño de Elche’s Auto Sacramental Invisible (2020), inspired by a 1949 composition by Spanish artist and inventor José Val del Omar (1904-1982), is both material and mystical. Such is the case with Tejal Shah’s Between the Waves (2021), a desiring machine, in which times and genres flow and the ancestral is current. It introduces poems and images that question the viewer, returning their gaze to themself, asking the audience to reflect on their capacity to perceive.

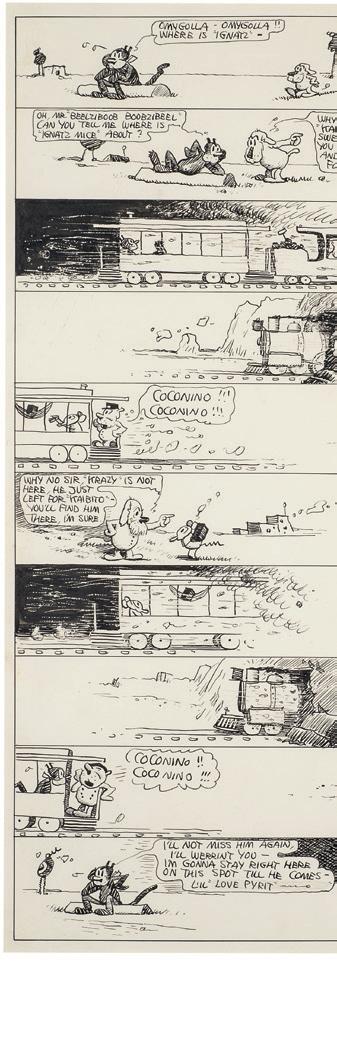

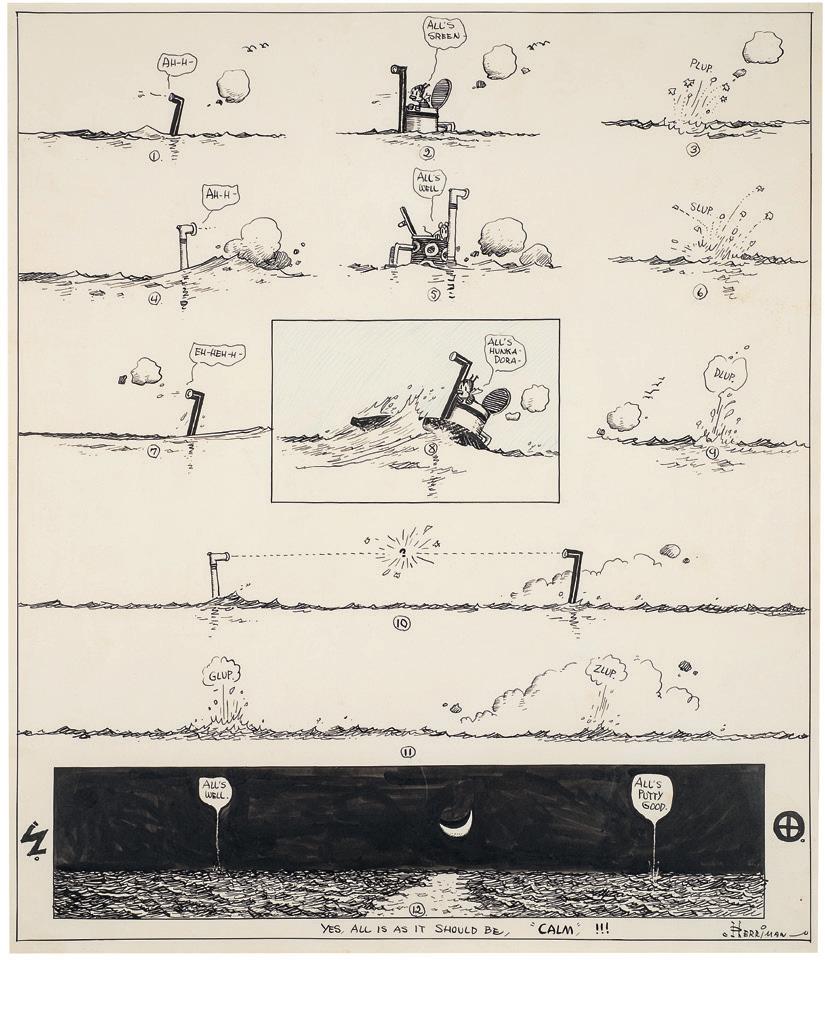

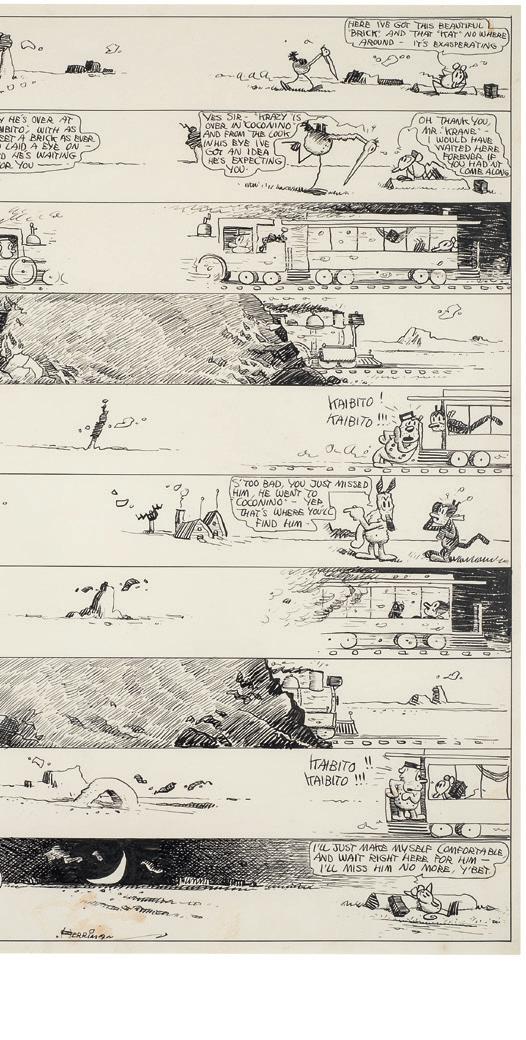

The voices, images, and objects in these and other pieces are fragments of a whole, always incomplete, which must be updated each time. They are not exhibited for the visitor to recognize themself in them, nor to explain a higher order, but to introduce elements of rupture in their way of being and acting, generating alternative political and epistemological reconfigurations, bringing together very different kinds of knowledge. Hence the Bienal is not organized according to thematic, formal or chronological affinities. A conceptual artist such as stanley brouwn, who worked in Europe in the second half of the last century, can make sense, for example, alongside an American comic book artist from the beginning of the century, like George Herriman (1880-1944). Or a space like Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho can approach the butoh dance of the film Meditation on Violence that Maya Deren (1917-1961) made in 1948. This choreography, which brings together scholarly and local artistic practices, proposes an insurrection of learning.

23 22

3. Bienal Pavilion, Ibirapuera. 6 September 2023

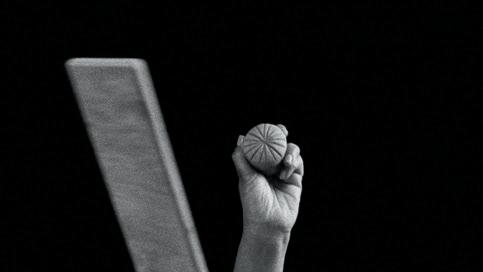

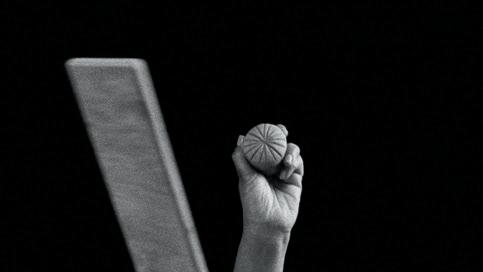

A woman dressed in traditional Mayan costume from San Juan Sacatepéquez stands on a cement base whose surface is still fresh. As the material dries, her ankles are also covered and she stands like a monument. Before the cement sets, the woman steps down from the pedestal. There is now no memorial figure. A plaque on its base seems to take her place. It reads: “Freedom for the rivers, the hills, the mountains, the flowers, and the lakes!” The action is a recreation of a piece entitled Monumento vivo [Live monument], that MayanKaqchiquel artist Marilyn Boror Bor represented in Guatemala City’s Central Plaza in 2021.

Memorials are fashionable, both in terms of their construction and their demolition. A natural and logical tendency of any repressed society is to try to take down the symbols of those who subjugate it. However, it is one thing to remove the monuments of repressors from public space, but quite another to amputate history. Such erasure is often the way in which an order of power is camouflaged and survives. After 1989 most of the countries that had constituted the Soviet bloc destroyed or hid almost all the memorial statues referring to the former regime. This does not mean that the oligarchy has ceased to exist in Russia and other countries. Large monopolies have replaced the Party apparatus.

Boror’s monument is not intended for a superior being who rises above all others. It is erected for those who apparently have no history and for non-humans. It proposes the idea of a society in which there is no separation between community and territory and in which our links with other species are reconfigured. The sustainability of our lives is rooted in a politics of care and affection, and opposes the notion of indefinite growth that has distinguished Western society for centuries.

The testimony offered by this Monument is neither at the center nor outside the conflicts. Its truth is based on the fact that it is a participant in the problem. The historical account is also history, not just a chronicle or description. On the pedestal remains the footprint of the feet, of the action,

the podium remains, but not the figure that oppresses because of the power it holds; it is not something that is transmitted or exercised, and it only exists in action.7 In this way, the Guatemalan artist questions both the language of oppression and the oppression of language. She proposes a kind of counter-history, which exposes the way in which power relations activate certain devices of knowledge and politics of truth. These devices consist in the ability to tell the story of other people and simultaneously make it the definitive one.8 To telling the history of the continent we know as America with the arrival of Christopher Columbus is not the same as using as a start point the communities that originally populated it, nor is it the same to begin telling the history of Africa with the failure of the African state as with its colonial creation.

Boror exposes the danger of a single history, because not being recognized by it or not accepting its recognition condemns one to non-existence. All the exclusions, oppressions, scorns, and despoilments derive from this eviction, but also all the heresies and dissidence, criticism and the creation of unsubmissive worlds. Those “without history” are both those who are expelled by it and those who resist its capture. So it happened with the civilizations that did not pass into what was considered the legitimate genealogy of Western culture. “How to endure nothingness? How to resist not being?” asks Marina Garcés in the epilogue of the Spanish edition of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s book, The Danger of a Single History.9

8/

9/

7/ Michel Foucault, Genealogía del racismo. Madrid: Las Ediciones de la Piqueta, 1992, p. 28.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, El peligro de la historia única. Barcelona: Penguin Random House, 2019, p.19.

Ibid., p. 43-44.

4. Chiapas. 21 December 2012. March of Silence.

Forty-five thousand Zapatistas peacefully and by surprise occupy some of the municipalities they took by force in 1994. The demonstration takes place without proclamations or chants. For a few hours, a crowd of hooded men and women march through the squares, their steps forming ephemeral spiral shapes. The date is revealing, as it marks the end of the world in the Mayan calendar and heralds the beginning of a new era for oppressed peoples

Modernity confused reality with vision and, in so doing, turned all epistemology into aesthetics. The modern world was not the result of the scrutiny or analysis of certain traces or vestiges, but a self-evident truth, because perception and representation were the same thing.10 This produced a false idea of space and time. The latter responded to a linear, progressive, and teleological conception of the universe. Space was imagined as an empty terrain to be conquered. An abstract and colonial non-place, incapable of admitting that, in the territories occupied by modern man, other human beings and forms of life already existed.11 All the ecological catastrophes, personal tragedies, and social fractures caused by the plundering of resources were erased at a stroke. In contrast, after a few years of little public activity, the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (ezln) reappeared, announcing a time and a space of its own, that of the “Caracoles” (“snails”), which is the name given to the districts governed by the Zapatistas in Chiapas. There were no speeches because there is a language that is neither discursive nor narrative; it is the language of the living body. The time claimed by the Zapatistas is opposed to the idea of chronos of the Western calendar, in which time is just a succession of events. The time of the March of Silence is, as Leda Maria Martins says in another context, a spiral, a temporality that bends forwards and backwards simultaneously, always in the process of prospection and

retrospection, of remembrance and becoming.12 Time and memory are images that reflect each other. They constitute an enigmatic knowledge, which traps us even though their meaning escapes us, because trying to apprehend an enigma means grasping the ways in which that which cannot be seen manifests itself. Every memory can evoke an unexpected event that supposes an opening to unimagined futures. Past and future are not part of a continuum, but interruptions of it. This is cardinal for communities and races that have lived in bondage and have had to move between impossibilities, between what was expected of them and what they actually did.

Their epistemes and a whole complex body of knowledge and values were re-territorialized, re-implanted, re-founded, recycled, re-invented, re-interpreted, in the countless historical crossroads resulting from these journeys.13

25 24

10/ Rolando Vázquez, Vistas of Modernity. Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary. Amsterdam: Mondrian Fund, 2020, p. 26. 11/ Ibid. p 34.

12/ Leda Maria Martins, op. cit., p. 23. 13/ Ibid. p. 45.

5. United States. Late 19th century. “If I can’t dance, I’m not interested in your revolution.” This is the phrase attributed to feminist activist Emma Goldman when a male colleague reproached her for dancing.

An admirer of a “rebellious and innovative” Nietzsche, Goldman proclaimed that “revolution is but thought carried into action.”14 She thus revealed the nature of a history which, despite all the revolutionary ruptures it might contain, was still conceived as a continuous evolutionary process. She reclaimed a history told through the movement of dance. That is to say, a different history, with its paradoxical laws, irreducible singularities, unheard-of and incalculable sexual differences.15

Capitalism originated, among other causes, in the expropriation of communal lands. Once this was accomplished, at least partially, there was another object and form of expropriation, that of bodies, which began in the course of the s17th century. As Silvia Federici points out, this was facilitated by the reorganization of the State and the Church, by the philosophical criteria of René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes, as well as by the new sciences of anatomy and statistics,16 leading to a disciplining of the body that aimed to transform it into a mere working tool, an object that could be used, exchanged or even destroyed according to the will of its owner or master. In short, it was a matter of making bodies submissive and obedient to the capitalist work schedule, of turning the body into a machine, especially necessary at a stage of technological development that was still in its infancy.17 This subjection has only increased since then and is the very basis of today’s necropolitics on a planetary scale.

14/ Jacques Derrida and Christie McDonald,“Coreografías.” Lectora: revista de dones i textualitat, Barcelona, n. 14, 2008, p. 157.

15/ Ibid., p. 160.

16/ Silvia Federici, Caliban y la bruja: Mujeres, cuerpo y acumulación originaria. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños, 2018, pp. 183-221.

17/ Victoria Pérez Royo, “Corporalidades disidentes en la celebración. Fiesta y política en la escena contemporánea", in Bárbara Hang; Agustina Muñoz (eds), El tiempo es lo único que tenemos. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, 2019, pp. 138-140.

Dance is the place where ghosts repressed by history can appear. Bojana Kunst explains that, by not being attached to anything, always dwelling on the edge of the fixation of its own image, ready to disappear at any moment, the performing body interferes with the instituted modes of figuration. Excluded beings can emerge through this dancing body, discovering forgotten or repressed movements and gestures. The past revives in us through dance. That is why its movements and rhythms constitute a political praxis. The choreographies that Katherine Dunham (19092006) designed in the 1940s on the basis of her anthropological research in the Caribbean would be a clear example of this. They were guided by an impulse to denounce that hid in the seams and cracks of an established knowledge system. In her dances, the body shone without form, and the joyful tension between presence and disappearance acted freely.18

18/ Bojana Kunst, “Los cuerpos autónomos de la danza.", in Bárbara Hang and Agustina Muñoz, op. cit., pp. 58-59.

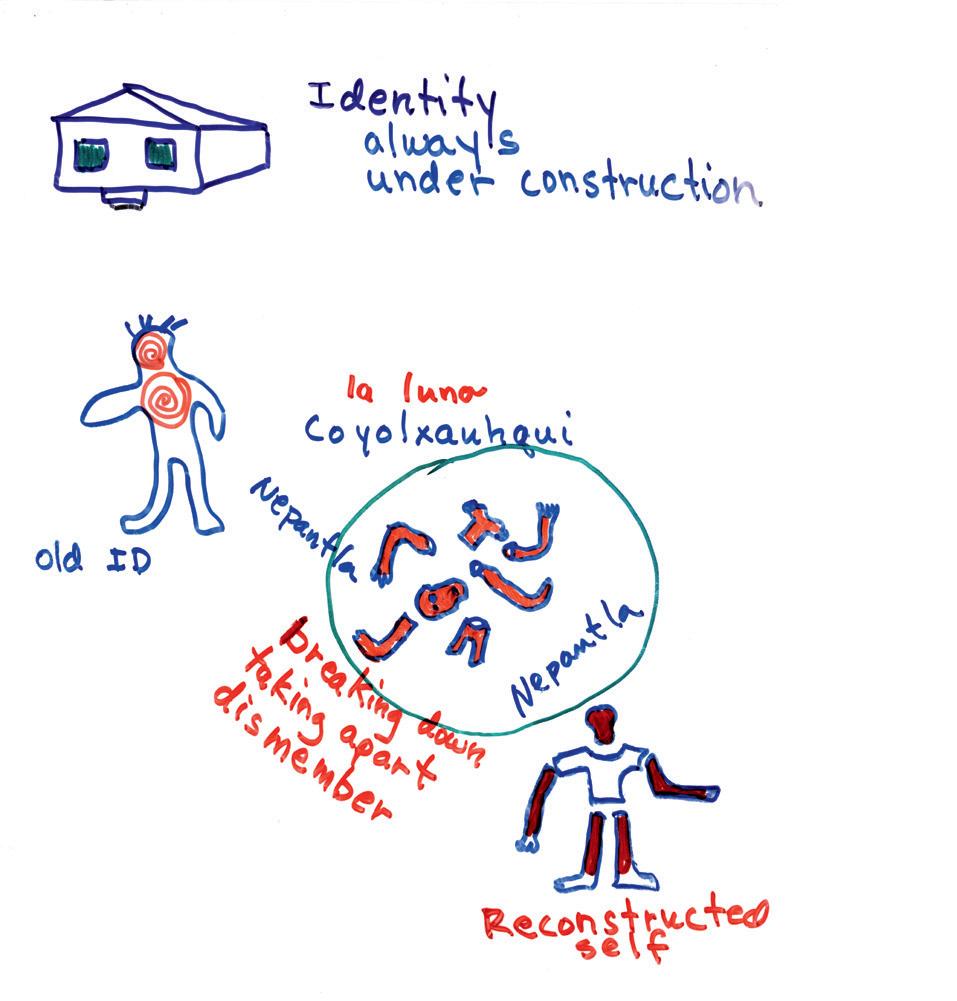

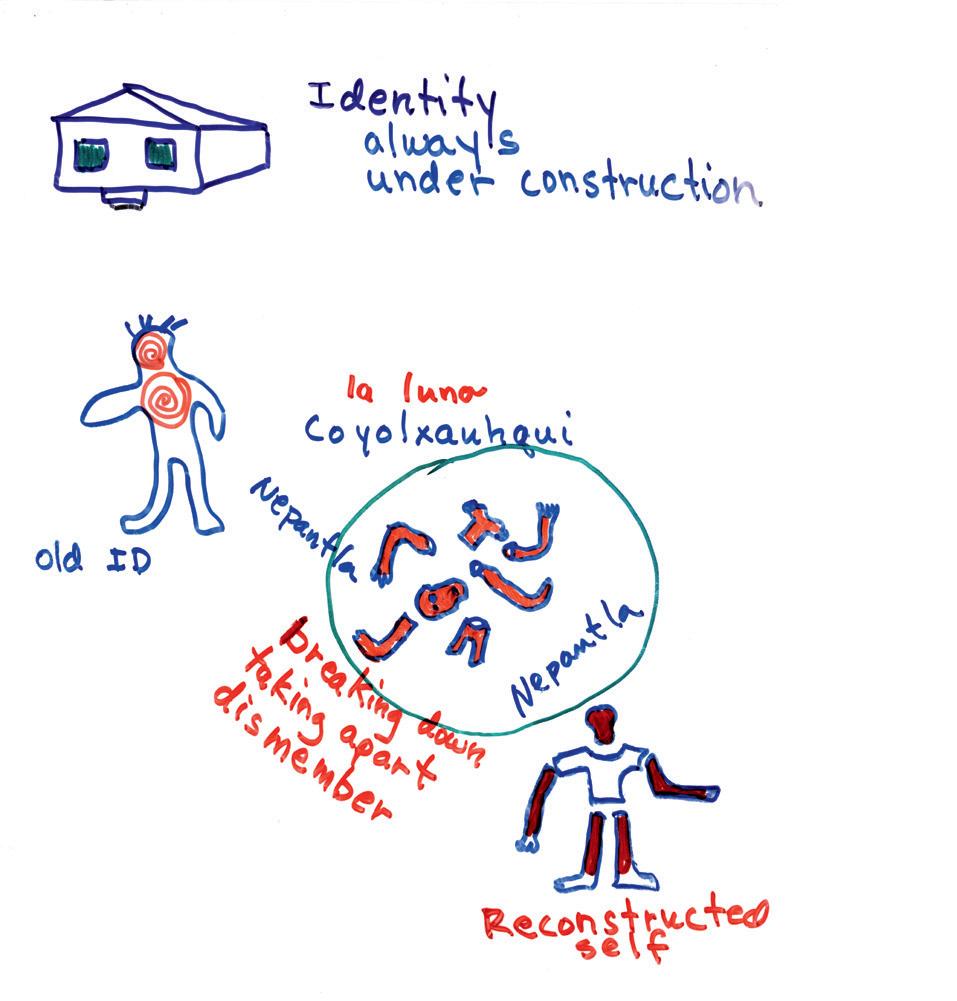

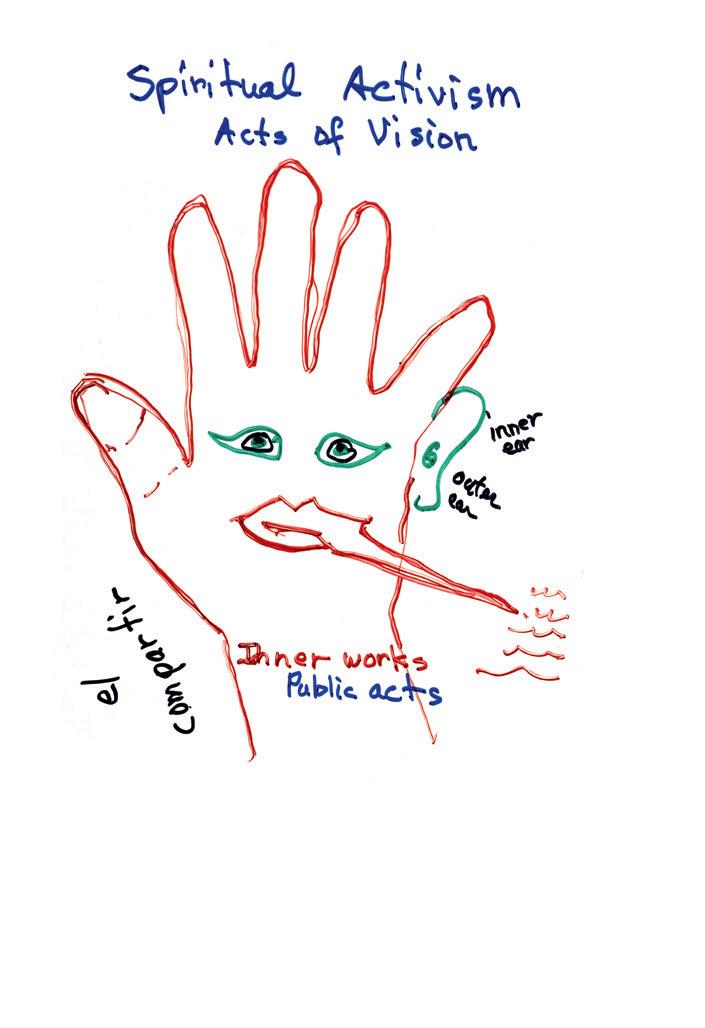

6. San Francisco, 1987. Aunt Lute Books publishes Gloria Anzaldúa’s book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. This book is essayistic, autobiographical, combines poetry with prose, is written in several languages (Spanish, English, Nahuatl, Tex-Mex, Chicano, and Pachuco) and delves into the idea of the border, of boundaries and divisions. One of the poems in the book begins and ends with the following lines:

To live in the Borderlands means you are neither hispana india negra española ni gabacha, eres mestiza, mulata, half-breed caught in the crossfire between camps while carrying all five races on your back not knowing which side to turn to, run from […]

To survive the Borderlands you must live sin fronteras be a crossroads.19

Anzaldúa argues that it is necessary to draw a map that does justice to the territorial reality of the border, that trans-geographical and trans-historical place where the reconstruction of collective identities of the diaspora or of those located beyond coloniality takes place. To this end, it is essential to reduce the scale in order to assimilate the fact that the territory in conflict, by the simple fact of being shared, harbours more stories than those that make up the national narrative. These stories are nourished by what each denies of the other, and between the mutual denial a space is created, one in which the rumor of the narrative of the expelled population, which has been suppressed and which is established against the grain of the others, takes shape.

Can I belong by not belonging? To be a citizen, yes, but a second-class citizen. Is this belonging by not belonging, or rather belonging by pre-

tending to belong? These are still two positions in tension that should be mutually exclusive, and yet they are two positions whose overlapping shapes a social identity.20

Accustomed as we are to the fact that only those who inhabit a territory have a narrative of their own, we have not been able to construct a history in which narratives have more to do with relationships than with identities. Unlike the latter, relationships are not fixed. Beyond reductive categories such as “American art,” “Latin American, art” or even more recent concepts such as “Afro-American art,” we should talk about the flows and encounters that took place on both sides of the Atlantic. On the other hand, while Foucault understood the confinement of prisoners as a form of control, control today is exercised on the basis of mobility. Diaspora has become a state of permanent deportation, which is the condition of many people without a voice in history.

Forced migrations, planned relocations, and exiles are part of our condition. The silences of history are marked by it. The movement of authors who have worked on the border, who have constructed a hybrid language, which is nourished by the past while subverting it, which maintains roots that have disappeared in their regions of origin, is unstoppable. This language finds its space at the crossroads, which is “a sacred place of intermediation between diverse knowledge systems and instances.”21

In Yoruba cosmogony this crossroads is represented by Èsù, who is constitutive of everything, of the material and the superhuman, of the feminine and the masculine. Not in a binary sense, but in flux, because it cannot be classified into any category. Èsù represents the ontology of time in the Yoruba cosmogony, since it is the ontology itself, the time that curves forward and backward.The reinvention of new subjectivities, gazes that hinder the colonial domination that occurs against those who are rejected because of their race or sexual orientation, is inescapable. Resisting the discourse

20/ Martha Palacio Avendaño, Gloria Anzaldúa: poscolonialidad y feminismo. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial, 2020, pp. 67-68.

21/ Leda Maria Martins, op. cit., p. 51.

27 26

19/ Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987, pp. 261-262.

of shame and seeking strategies to rewrite history are radical political acts, that break with many of the established epistemological divisions and unite with authors from different continents, generating unexpected cartographies. In his introduction to Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s book, Jack Halberstam mention Maurice Sendak’s famous short story Where the Wild Things Are (1963).22 For Halberstam, the protagonist of Sendak’s narrative is on a journey to a world that is no longer the one he left, but also not the one he originally intended to return to. This is, according to Halberstam, the most important element of Harney and Moten’s text. We cannot really imagine a future when we set off from a reality that is intrinsically unjust, whose form of knowledge is imposed on us and does not allow us to see beyond its limits. It is impossible to put an end to colonialism if we fight it with its same tools, with its same truths. It is inescapable that we situate ourselves in a space that has been abandoned by the regulated and the normative. It is an indomitable, borderline space that exists beyond colonial reason, it is not an idyllic utopia, it already exists in many situations: in jazz, in the improvisation of performance, in noise, in the enigma of the poetic. This “other place” is already present in our desire. As Moten says, according to Halberstam:

The disordered sounds that we refer to as cacophony will always be cast as “extra-musical” […] precisely because we hear something in them that reminds us that our desire for harmony is arbitrary and, in another world, harmony would sound incomprehensible. Listening to cacophony and noise tells us that there is a wild beyond to the structures we inhabit and that inhabit us.23

22/ Jack Halberstam, “The Wild Beyond: With and for the Undercommons", in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions, 2013, p. 6. 23/ Ibid., p. 7.

Translated from Spanish by Ana Laura Borro

the impossible diane lima

“Beauty is not a luxury, rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical act of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity for the baroque, and the love of too much.”1 saidiya hartman

When, the other day, you asked me why I said yes to the impossible, I remember answering almost without thinking that it was to survive: a way to find freedom or, simply, to make things more possible in life

The questions “what is the impossible” or “what is impossible” soon popped up, because if we consider the impossible to be the ontology of black women, we will always tend to face these questions with a certain intimacy and, above all, with an absolute sense of refusal, given that the revolt against the compulsory condition that makes the impossible more possible for some than for others is implicit in our daily lives.

Today, looking back on my days as curator of the 35th Bienal de São Paulo from the few that remain as such, I am left with the same feeling I had during a research trip to Jamaica, when I understood that, always journeying with the task of survival, it is to search for beauty that we defy the impossible.

“A beauty of life” were the words I began to repeat over and over until the moment I could no longer discern between what was sea water, tears, or raindrops. “A beauty of life” seemed to be the revelation of a commitment or a promise that, at some point, had been made, and which, until then, I didn’t even know about.

By this time, I was totally immersed by Christina Sharpe’s thought that beauty is a practice and a method. “What is beauty made of?”2 she asks. “Attentiveness when-

1/ Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019, p. 60.

2/ Christina Sharpe, “Beauty is a Method.” e-flux, n. 105, Dec. 2019.

Available at: www.e-flux.com/journal/105/303916/beauty-isa-method/.

Accessed: Jul. 12, 2023.

ever possible to a kind of aesthetic that escaped violence whenever possible — even if it is only the perfect arrangement of pins.”3

If the only way to find beauty is to refuse all impossibilities and escape violence whenever possible, perhaps that is a first free definition of what the choreographies of the impossible might be. A beautiful experiment, to also quote my rapture at the way Hartman sees beauty in the everydayness of rebellious lives, a gesture that refuses what has been given as destiny and the always scarce possible options. A life that refuses impossibility, but “demands the impossible — reparation.”4

I believe that being in Jamaica touched me deeply because it was a kind of encounter with some notions of what I consider beauty that I have long wanted to experience. In one of the conversations I had with the researcher and opera singer Inaicyra Falcão, who gifted me with thoughts like “dance is everyday life transformed” and “grandma was my new world,” she made me relive how the transits of the Black Atlantic are remade in Bahia, when telling me how, since she was a child, she nurtured a cosmopolitan impetus by having access to a whole Atlantic cultural repertoire that passed through Ilê Axé Opô Afonjá, in Salvador.

Afonjá is the terreiro where she learned from Mãe Senhora, Maria Bibiana do Espírito Santo, her paternal grandmother and a recognized Ialorixá, how to be an articulator of worlds. It made an impression on figures such as the French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, as they learned through Mãe Senhora’s famous phrase “from the gate inwards, from the gate outwards” how the dynamics of knowledge production and transmission take place in the circular spaces of African heritage in Brazil. A knowledge that is learned in performance, that is made and remade in everyday life, in a participatory dynamic in which one learns with the whole body and not only through an ocularcentric,

3/ Ibid.

4/ Saidiya Hartman, “Extended Notes on the Riot.” e-flux, n. 105, Dec. 2019. Available at: www.e-flux.com/journal/105/302565/extended-noteson-the-riot/. Accessed: Jul. 12, 2023.

29 28

categorical, and binary dimension between body and mind. Which is dedicated to all those who inhabit the doorways 5 and which gains from the image of the gatekeeper the determination of what liturgical knowledge is, which must be preserved with its secrets in the community of initiates, and what can be transmitted and recreated as intellectual and artistic expression for society in general.

Teachings that Falcão incorporated when musicalizing the orikis, a memorial poetry that narrates the heritage of the knowledge of the Nagô-Yoruba tradition and that, even before becoming the Autos coreográficos: Mestre Didi, 90 anos, 6 or any other of the many books dedicated to Deoscoredes Maximiliano dos Santos, Alapini, supreme priest in the worship of the ancestral Egunguns, artist, playwright, writer, and her father, had already manifested the desire for a choreography of displacements.

With a sonorous timbre that is felt in one’s skin, the frequencies of this dramatic soprano’s voice reached its most plural modes of expression at the borders. From her long academic career retracing the flows of BrazilNigeria, we ended the day talking about how this trajectory had informed her “pluricultural proposal of dance-arteducation,”7 in which ancestral exercises and technologies, from the deepening of collective listening to the exercises of collectivization of choreographic processes through everyday movements, build an archeology of spinning that finds, in the voice, its own dance.

By the end of the day the only thing we hadn’t talked about was the title for the project we had commissioned, which concerned the recording of an album, the publication of a book, and a presentation of her lyrical performance. But as “every wheel of movement turns into a radiating center of force and vibratory energy that expands

5/ Dionne Brand, Um mapa para a porta do não retorno: notas sobre pertencimento, trans. Jess Oliveira and Floresta. Rio de Janeiro: Bolha, 2022.

6/ Deoscoredes Maximiliano dos Santos, Autos coreográficos: Mestre Didi, 90 anos. Salvador: Corrupio, 2007.

7/ Inaicyra Falcão dos Santos, Corpo e ancestralidade: uma proposta pluricultural de dança-arte-educação, 2. ed. São Paulo: Terceira Margem, 2006.

its borders,”8 two days later Falcão wrote to me saying that the project had been baptized. When I read it, I was surprised, for it was the same expression by which I had been called that night by a researcher passing through town, who explained to me the meaning of the word in Yoruba. I breathlessly replied to Falcão, who told me the reason for her choice: when she went to Nigeria, she was soon called TOKUNBÓ. And when she began to attend Ilê Axipá, the ancestors also gave her the title of TOKUNBÓ. “I am always hovering. I go to Nigeria and I come from abroad, then I’m here and I come from there.”

TOKUNBÓ: sounds between the seas. We have a title.

the Mona Lisa

I grew up in a town called Mundo Novo, in the state of Bahia,9 in a house with a beautiful view over two mountains, where the window was the stage for my imagination and my thirst for discovering what lay beyond the valley, or what I might see behind the mountain range. In that house, I grew up with abundance and prosperity, and by the late 1980s, my mother had been the first to realize and conquer much of what was not widely available in the city as a field of possibilities. And that was a lot for me. I don’t know if anyone else in my family saw it the same way, so I don’t speak of it as a fact, but as an impetus, a fire, a feeling. As I suppose the impossible makes its home in believing, the walls, as unbelievable as this story may sound, were taken over by reproductions of classical works of Western art history. In birthday photos, balloons on the walls contrast with duly framed characters, among them the Mona Lisa (1503), by Leonardo da Vinci; the work Bust of a Man (the Athlete) (1909), by Pablo Picasso; A Walk at Twilight (1889-90), by Vincent van Gogh; as well as two still lifes, a Virgin Mary with a child in her arms, a clown,

8/ Id., “Tramas criativas de corpo e ancestralidade,” in Fundação Bienal de São Paulo (ed.), aqui, numa coreografia de retornos, dançar é inscrever no tempo: publicação educativa da 35ª Bienal de São Paulo — coreografias do impossível. Movimento 1. São Paulo: Bienal, 2023. 9/ Mundo Novo literally translates as “new world”.

and a woman with a horse — for the last two, I always held less appreciation.

I grew up with them, talking to them, naming them, and literally creating my own stories for them. The Mona Lisa, of course, was the one that impressed us the most. At nightfall or when fear of being alone crept in, so did the fear of that eye that stalked us. And, in case of any disobedience or restlessness, it was enough to remember that the ghost was hanging and that, if I was not brave, at some point those eyes would catch me.

I don’t know what seems more impossible to me: to have met the Mona Lisa in that condition or to have managed to escape from her.

As I grew up in a house with a communist and trade unionist mother, and a great-grandmother who, having passed away at the age of almost 104, left us as a legacy, among many teachings, the proverb “tomorrow is dark,”10 I decided to tell this story, because I came back from Falcão’s house wondering if it was not from this episode that beauty became a synonym of escape for me. Also, to highlight how multiple are the ways in which the impossible constitutes us throughout life. What Hartman, when discussing the work of the artist Simone Leigh, calls the “monumentality of the everyday”:

Her work, like my own, is preoccupied with the question of scale: how to undo assumptions about the provincialism and narrowness of black women’s life and work, so that the dimensions of their existence in the world, their contribution, their way of making and doing might be recalibrated.11

This means that one can see the lives of black women not only as an “inventory of violence”12 but as an “architecture

10/ In Portuguese the sentence “o amanhã é escuro" concentrates a poetic and prophetic charge with two meanings: dark is also Black which means the future.

11/ Saidiya Hartman, “Extended Notes on the Riot", op. cit. 12/ Ibid.

of possibilities,”13 so that we can find a “critical language capable of conveying the epic scope of the black ordinary and the monumentality of the everyday.”14

It was as much this ordinary life of cosmopolitan Salvador that Falcão’s lyric singing transcended, as it was this ordinary re/cognition of Black women’s creative and intellectual output that materializes in the many images, sculptures, and encounters created by Simone Leigh, that readied me to respond, in the lecture we gave in collaboration with New Local Space (nls) in Kingston, Jamaica, to what had brought me there.