Cover Image

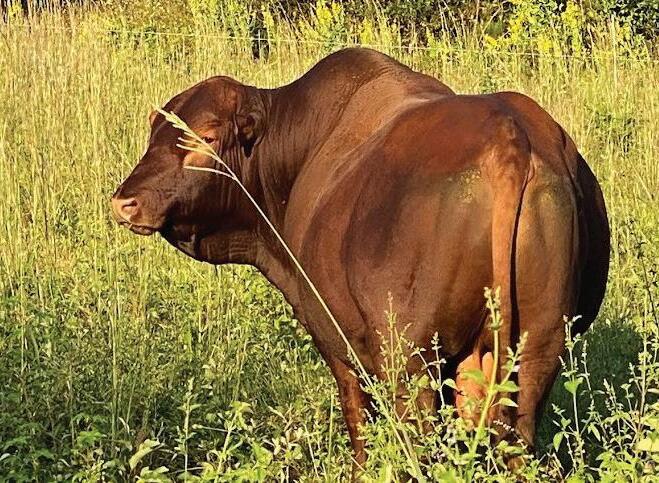

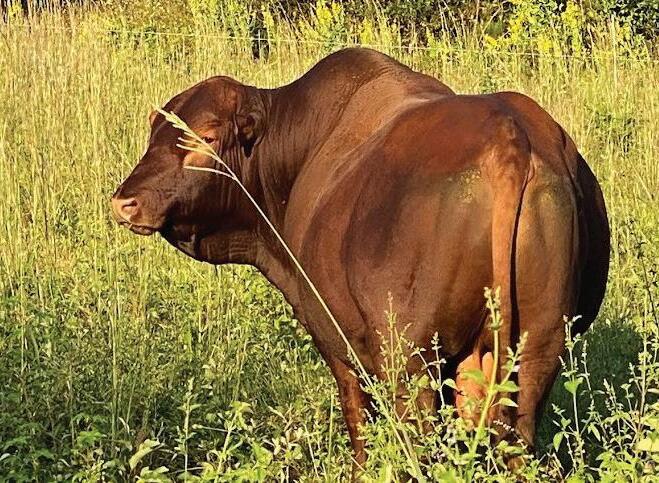

Tuli Bull

Tiptree Tuli TT1432

Steve Mains-Sheard

OUR MISSION CONTENTS

Presidents Address Introducing Sanga International

Tuli Mashona Nguni Boran Drakensberger Solera How

To preserve unique full blood Sanga genetics imported from Africa that are no longer accessible.

To establish Solera as a pathway for established cattle producers to incorporate Sanga genetics into their herds through the acquisition of full blood Sanga animals.

to Become a Breeder

5 11 17 23 29 33 37 45 2

PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS

Look to the Selection of Sanga for the Solutions to the Future of Nature Positive Grass Fed Beef.

Greetings to all champions of sustainable agriculture.

I extend my warmest greetings to each of you as we embark on a collective journey toward a future of nature-positive beef production on a global scale. Today, I have the privilege of addressing you as the President of Sanga International, a consortium deeply committed to advancing the prosperity and well-being of our member breeds: Tuli, Mashona, Nguni, Boran, Drakensberger, and the unifying Solera composite breed.

In this pivotal moment for our planet, it is imperative that we recognise the critical role we play as guardians of African cattle genetics, including their place in regenerative agricultural practices worldwide. As custodians of these diverse and naturally selected breeds, we have a shared responsibility to harness our strengths in preserving and disseminating these unique genetic assets. By doing so, we can unlock a wealth of potential for producing naturepositive grass-fed beef that benefits both people and the planet.

At Sanga International, we are guided by a commitment to holistic management principles that prioritise the well-being of both animals and ecosystems.

Our mission is to amplify the inherent benefits of each breed, transforming them into valuable contributors to a regenerative agricultural system. Through collaboration and the implementation of best practices, we strive to develop innovative solutions that enhance biodiversity, soil health, eating quality, fertility and ecosystem resilience.

The significance of Sanga cattle lies not only in their genetic predisposition to thrive in diverse environments but also in their ability to promote nature-positive outcomes through collective grazing and methane cycling. These animals serve as living examples of the potential for agriculture to be a force for good, restoring ecosystems and sequestering carbon while producing high-quality beef. As we confront the urgent challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss, the resilience of Sanga cattle and the low carbon intensity holistic management practices they embody become increasingly essential. By prioritising low-stress stock handling, regenerative grazing, and soil health management, we can harness the full potential of these animals to mitigate environmental degradation and build resilience in agricultural systems worldwide.

Our Sanga International platform serves as a hub for sharing knowledge, experiences, and insights from around the globe. As we look ahead to future collaborations and initiatives, let us come together to celebrate the successes of nature-positive grass-fed beef production, inspire one another, and pave the way for a future where agriculture serves as a catalyst for positive change.

Together, let us embrace the challenge of producing food in harmony with nature and, in doing so, sow the seeds of a more sustainable and resilient future for all.

Sincerely,

Jack Milbank BAppSci (Agronomy) N.Sch Hartwood Cattle Co. President, Sanga International and Australian Tuli.

Jack Milbank

Jack Milbank

Milbank 0434 678 228 jack@hartwoodcattle.com.au 3

Drakensberger Nguni

Jack

Tuli Mashona

Solera

4

INTRODUCING SANGA

It is my pleasure to present to you the first Sanga International Journal.

This magnificent initiative conceived by Jack Millbank and Udo Mahne has gained stature. It has generated enthusiasm from scientists such as Professor Louw Hoffman, farmers, breeders and feedlot owners, who have joined in a collective effort to save, preserve and globally promote Africa’s most important contribution to the agricultural world, the adaptable and profitable Sanga breed.

In 2014, the World Health Organisation banned the export of bovines and bovine genetics from Africa to the rest of the world to limit the outbreak of foot and mouth disease. That, as a natural consequence, ended the export of Sanga cattle to the world and to the detriment of the bovine industry.

Through the initiative of Jack, the Sanga genetics have been collected from wherever possible, outside of Africa and brought to Australia to preserve the breeds and to establish the Solera composite for the benefit of

farmers across the globe. In doing so, Jack and Udo have conceived of a composite SOLERA breed principally made up of the Sanga breeds but supplemented by a number of accepted and compatible composite breeds to fulfil the mantra of:

“Tell us where you live, and we will breed a bovine that will flourish in your area.”

Changing the breed to suit the environment.

The first hominoid rock art of bovines is over 30,000 years old. The domestication of bovines is only a few thousand years old. Although the authorities controversially do not necessarily agree, it would appear that bull selection took place as early as three thousand years ago when the ancestors of modern-day cattle, the aurochs, underwent bull selection to improve the bovine species. In one respect, we are all farmers; homo sapiens have been involved in the growing promotion and improvement of cattle for thousands of years.

EDITOR’S NOTES

Meat from cattle still constitutes by far the most important source of protein available to humans. Protein is the most essential brain food.

The footprint of producing cattle remains a crucial factor in sustainable farming. Less cattle, more meat is a sustainable policy that takes the ecological imperative to a logical conclusion. The Solera group is about exactly that: low cost, low maintenance, low input, high-quality cattle, producing excellent meat and protein on a sustainable level to combat a fast-approaching world food shortage.

The articles in this publication have been provided by a variety of breeders and enthusiasts and have been edited to comply with the space requirements of this publication. I would like to thank all those who have contributed to this publication and look forward to a growing group of enthusiasts, contributors and participants in this exciting venture.

I would also like to thank Tim Sweetapple from EXO Creative for the gargantuan task of publishing this journal, marshalling the advertising, collecting funds, editing photographs, and assisting with the proofreading of this journal. Without him, this publication could not have taken place,

Kind regards,

MartinLuitingh

5

ON THE OTHER HAND

Cattle selection decisions based on objectives, resources and environment.

PJ Budler, 2022

Genetics are the point of the arrow when it comes to the livestock industry. Although genetics are of equal importance to disciplines such as herd management, nutrition, animal health, marketing, forages, record keeping and Human Resources, genetics remain the prime mover.

As the last link in the value chain, the consumer being the first link, genetics determine how the rest of the value chain flourishes or fails.

The seedstock producer must act as a scientist with their ranch or farm being their laboratory.

By adapting their genetics to the particular environment, resources and objectives they’re dealing with, the seedstock producer experiments, invents and proves or disproves genetics.

There is an abundance of selection tools available to cattle breeders. These tools vary from traditional to cutting-edge and are all used to differing degrees within both the beef and dairy industries.

The selection tools I’ll discuss in this article include phenotype, pedigree, in-herd indexes, Production Based Culling, EBVs/ EPDs, and Genomics/Genomic enhanced EPDs.

All of these tools can be useful when making breeding decisions provided that they are used in context and with a non-biased and balanced approach.

The first objective to be considered is whether the animal you want to breed is destined to be utilised in a maternal breeding program or as a terminal animal for beef. The selection criteria for these two options is vastly different and I’ll go into more details in paragraphs to come.

A premise to consider is that there are two types of traits in a maternal breeding program. Profit traits include adaptability, functional efficiency, fertility and longevity. Turnover traits include growth, muscle, milk and marbling. Turnover traits are very important but are meaningless if profit traits are not used to lay the initial foundation.

Every breeding decision must be made according to objectives, resources and environment. Without matching these decisions to these three factors, there’s a good chance of missing your target.

The animal’s Pedigree is extremely valuable when making selections. Understanding or remembering pedigrees is fast becoming a lost art in the age of genomics. However, pedigree is the motherlode from whence all these technologies have sprung. Traits such as mothering ability, libido, temperament/aggression, well-being and hardiness are immeasurable in any accurate form by any technology. The knowledge of the ability for certain bloodlines and cow families to work together is where the art of breeding comes to fruition. A lot of selection criteria are too nuanced for the scientific method.

6

Phenotype is extremely useful, and I’d say essential, when making breeding decisions. A lot of what data or EBVs/EPDs are telling you can be seen in the animal itself. The analogy that I like to use is that when you are told that it is raining outside, one can simply open the curtains and take a look instead of checking the weather application on one’s smartphone. Growth, Fat, Muscle, Milk, Calving Ease and a host of other traits are as easily observed with the human eye as they are read off of a chart. When making phenotypic selections, one must first consider whether the animals are maternal or terminal.

In maternal animals, cattle need to be able to eat, walk and reproduce. Focussing on the Profit Traits (adaptability, functional efficiency, fertility and longevity) is first and foremost. Balance is essential. This includes physiological and endocrinological balance, carcass balance (muscle/fat ratio), skeletal balance and hormonal balance. High inherent body condition (easy fleshing ability/do-ability/ constitution) plus hormonal balance equals fertility.

In terminal animals, the fundamental traits remain vital. In animals bred for a high-yielding carcass, factors to focus on are a high growth rate and large ribeye area. Dimension is essential, too, as three-dimensional animals produce heavy carcasses. Carcass balance is still essential as fat cover is needed for good grading and fleshing ability, while muscle is required for yield. Structural soundness is essential in terminal animals, too. Structurally unsound animals tend to founder and go lame when in the feedlot. These animals lose their appetite and don’t gain appropriately. Also, steers have sisters and mothers out grazing on pasture

their entire lives, so ignoring structure in terminally bred cattle is dangerous. In terminal animals bred for high-quality eating experiences, like the Japanese and South Korean breeds, the logic remains similar in terms of structural integrity. Carcass balance leans further towards marbling traits with muscle being necessary but not pinnacle. Waxy horns, a sharp poll (or a fine ridge between the horns), oily skin, silky hair coat, flat and fine bone with small joints and a flatter muscle shape all augur well for high-marbling carcasses.

Production Based Culling is a term I use where replacement females and breeding bulls are selected based on the fact that their dams, grand-dams and great-grand-dams have simply jumped over every hurdle the breeder has placed in front of them regarding criteria to remain in the herd. These include reasonable nutritional supplementation, age at first calving, inter-calving period, short breeding seasons, cow/calf ratio at weaning, minimum weaning weights, unassisted births, etc. This is a fast way of building a profitable, consistent, adapted and uniform herd.

In-herd Indexes were the primary arithmetic used for cattle selection prior to the arrival of EBVs and EPDs. These in-herd indexes remain a vital tool when customers purchase animals from a reliable seed-stock breeder or when the seed-stock breeder is presenting their product to the market. They give context to how animals have performed in their given environment and herd. It is important to remember that not all herds are the same. A 100 index in a progressive herd is superior to a 100 index in a less

progressive herd. However, if one is familiar with and utilises a registered herd for their seedstock needs, using in-herd indexes for selection purposes is very valuable. EBVs/EPDs/ Breed Population Indexes are widely used worldwide by animal producers. These numbers are based on the in-herd ratios of the animal itself as well as the in-herd-indexes of its ancestors, siblings, relatives and offspring. EBVs (Expected Breeding Values)/EPDs (Expected Progeny Differences) can be extremely useful if used in context and when matching them to objectives, resources, and the environment. As a breeder, one needs to decide whether one trusts these numbers being published by their specific breed society/association. If the breeder believes that they are relevant and that most breeders are measuring everything, all the time, accurately, honestly, in large numbers and in the same environment, then it is important to remember that the number being produced is an objective one. Therefore, no EPD/EBV can be good or bad. It depends on one’s objectives, resources and environment.

In maternal breeding programs, it is essential to remember that the sex hormones only start when the growth hormones stop. Therefore, if one selects for high growth numbers, one is directly selecting against fertility. Selecting for fertility starts with high inherent body condition and hormonal balance. On an EBV/EPD chart that would mean higher BACK/RUMP FAT numbers and higher SCROTAL CIRCUMFERENCE at a year of age. Selecting for Top 5% Weaning and Yearling Weight continuously will create higher birth weights, leaner, later maturing and less fertile cattle

7

with higher energy requirements. Selecting for high inherent body condition and early sexual maturity will produce cattle with high relative (reaching mature size early) growth rates, low energy requirements and high fertility. If one feels that the average animal in one’s breed is big enough, it makes no sense to require anything more than the breed’s average EPD/EBV Yearling Weight or Mature Cow Size. Similar logic works with all traits.

You’ll notice that herds that have focused heavily on growth and carcass traits for some time will have a lack of sexual dimorphism in their cattle. There won’t be much difference in size and shape between the bulls and females. This sexual monomorphism is an expression of hormonal imbalance and subfertility. Bulls tend to be less masculine, and females tend to be less feminine. Sexual dimorphism occurs when selection for high inherent body condition and hormonal balance is practised. These animals mature earlier and are more fertile. The bulls are significantly larger and shaped and coloured differently from the females. Publishing trait leaders is counter-intuitive in my opinion. For example, why is less fat better than more fat when publishing a FAT trait leaders list? Doesn’t it depend on the objectives, resources and environment of the breeding program? Big, lean, late-maturing cattle are great for feedlots and processors but devastatingly expensive to keep for cow-calf operators. What good is giving the tools of a Top 1% for a trait like Milk to marketing companies to run with? Top 1% for milk doesn’t even make a profitable dairy cow, never mind how destructive it proves to be for beef cow operators.

In terminal breeding programs, traits such as Weaning Weight, Yearling Weight, Ribeye Area and Intramuscular Fat become important. Managing birth weight to where its functional is important.

Genomic Enhanced EBVs/EPDs are based on the same premise as EBVs/EPDs. However, the actual genetics of the animal are taken into consideration and not just the average EBVs/EPDs of sire and dam at birth. GE-EPDs/ GE-EBVs increase the accuracy of an EPD/EBV for an animal with no offspring to have the same accuracy of that same animal if it had had up to a dozen offspring. If the premise of EPD’s and EBV’s make sense to the breeder, then GE-EPDS/GE-EBVs will work for them.

If, however, a breeder does not agree that the data being used to create GE-EPDs/GE-EBVs is measured entirely, honestly, accurately, in large numbers, all the time, eliminating environmental influence by most breeders, then it is probably better to revert to the other tools in the selection toolbox. These being Phenotype, Pedigree, In-herd Indexes and Production Based Culling.

“Cattle breeding is as much an art as it is a science.

Artists and scientists alike are passionate and obsessive about their work.

Context and nuance are key.” PJBudler

Rhodesia

The epitome of balance wrapped up in a slick, fertile, heat tolerant package.

HARTWOOD RHODESIA HR362 PP (AI)

REGISTERED TULI - DOB : 25/10/2019

Hartwood Rhodesia 19 362 (AI) is a Homozygous polled, Docile, Slick, Recessive Red, Dun gene carrier. He is a Myostatin free, flatback, heat tolerant, fertile Tuli Sire that will add resillience to any breeding herd in the north. Hartwood Rhodesia is moderately framed at 850kg. The benefit he brings in the form of hybrid vigour makes him the maternal, heifer bull of choice for Northern Australia.

EXPORT ACCREDITED SEMEN NOW AVAILABLE

Exceptional progeny are now on the ground with consistent, productive, predictable calves. Hartwood Rhodesia is out of HTS 14 072 a dam proven through calving ability on scrub in the El Nino drought from 2015-2020. His grand dam dam is TRE 10 0125 who is by TRE 03 0051 Bin Lardin the sire produced from Imported (Zim) Terraweena Zangu 2045. Rhodesia's maternal lineage traces back to Embryo Dam Inyanga 4 selected by CSIRO. On the Sire side he traces back to the Imported Sire Mazunga, one of the most significant contributors to the Tuli breed globally. Mazunga was a Bull out of ZIHEAN HYM025 by ZIMATO 81 WWW.HARTWOODCATTLE.COM.AU

All Semen is tested and only collected when a Live, Normal, Progressively Motile (LNPM) cell count of 8million is achieved

What do you get when you incorporate Tuli genetics into your breeding program.

Thousands of years of isolated natural selection in arid, predatory environments leading to a genetic pre-disposition to collective grazing that builds soil carbon & an exceptional contribution to hybrid vigour in either Bos Indicus or Bos Taurus herds.

e most heat tolerant cattle breed on earth originating from s natural adaptation to the condition in the Kalahari Desert and Lowveld of Zimbabwe. Selected by the leading CSIRO scientists for import to Australia

Exceptional fertility, milk and meat quality with unrivalled grass conversion efficiency and ability to thrive in severely deficient landscapes while exhibiting a docile low stress temperament

Export Semen Available from Hartwood Rhodesia Tuli are a contributor breed to the Solera & part of the Solera Selection Sale

HEAT TOL ERANCE FERTILITY

HYBRID VIGOUR

PARASITE RESISTANCE DOCILITY

IMF

SEMEN ~ EMBRYOS ~ BULLS

Ph: +61 (0)434 678 228 beef@tuli.com.au

Holy dooley! I need a Tuli!

www.tuli.com.au

Cattle Breeders’ Society of South Africa

: +27

323 4286 (Stephen Mains-Sheard: President) | Landline : +27

410 0958

: tuli@studbook.co.za | www.tulicattle.co.za F e r tile, P r o f i t able Veld C attl e

Tuli

Mobile

82

51

Email

TULI

Tulis are known for their early maturity, good mothering ability, docile nature and high fertility. They can withstand intense heat without showing signs of stress. Due to their unique genotype, Tulis offer the maximum hybrid vigour in crossbreeding programs.

TULI

11

TULI

This hardy, unique Zimbabwean breed was developed in Zimbabwe to thrive under often challenging climatic conditions. In 1955, the Tuli was registered as a Zimbabwean indigenous breed. The late Queen Elizabeth awarded Len Harvey the prestigious MBE for his contribution to agriculture in Zimbabwe.

The Tuli breed is medium-framed and comes in four basic coat colours: red, gold, ivory and dun. The Tuli is sleek and shiny with a short-haired, smooth coat, which deters ticks. This has also allowed them to adapt well to the intense sunlight typical of Zimbabwe,

which is very similar to the northern parts of Australia.

One of the most advantageous traits is their fertility, calf-toweaning ratio, and early maturity. Premium fertility means more calves and, therefore, more income every year. Price-wise, Tuli is at the high end because of the exceptional quality of meat they produce. The Tuli is earlymaturing, and re-conception is earlier, allowing for a faster return on investment. Their average pregnancy rate is 90%.

The breed’s mothering ability is outstanding, as they actively protect their calves against predators.

Other traits that set this breed apart are their hardiness, diverse environmental and climatic adaptability, low maintenance and their natural ability to handle intense heat without stress. Their outstanding tick and disease resistance is legendary and reduces vet bills and treatments. The breed’s temperament makes them very easy to work with and they are tolerant to nutritional shortages.

In dry areas with as little as annual rainfall in the area could be from as low as 159mm/y to 420mm/y, coupled with temperatures of over 40°C. Tuli Cattle will flourish.

The manager of the Nuanetsi Ranch Tuli stud, Keith Kaschula, is probably the breeder who runs his stud under the most taxing conditions in Zimbabwe.

Kaschula states that his Tuli weaners outweighed his Beefmaster weaners by 6kg on average, even though the Beefmaster is considered a bigger breed. The Tulis cope better with long-distance walking under extensive farming conditions whilst maintaining condition and produce more calves per unit.

The breed’s indiscriminate grazing habits make it the ideal choice in harsher grazing environments and to mitigate the effect of drought. In drought years, it is easier for Tuli females to obtain their nutritional requirements from the land.

The animals’ access to roughage is increased by chipping and shredding bush and feeding it to the cattle. Stewart says they love eating it fresh, and despite the lack of leaves during the drought, the stems come out bright green, which gives the animals a significant protein boost.

Kerry Stewart, Chairperson of the Zimbabwe Tuli Breeders’ Society, says, “It is important to fit your cattle to the type of environment you have, not fit your environment to your cattle. It is more expensive to try to change your environment than to change your type of cattle. If the environment is not suited to your cattle, you are going to spend money on supplementary feeding and cattle losses due to pregnancy misses and deaths from diseases. With the Tuli’s attributes, such as being highly adaptable to virtually all conditions, the breed obviously makes financial sense.”

Annelie Coleman Farmer’s Weekly South Africa.

Read the full article:

https://www.farmersweekly.co.za/ animals/cattle/zimbabwes-tulicattle-make-financial-sense-andare-easy-to-farm/

13

Photos provided by: Jack Milbank & Mary Mains-Sheard

African Genetics Why? Focussed Profit Drivers Fertility + Stocking Rate + Adapted Genetics Lantz Hobbs HoTuSt African Genetics lantz.hobbs@gmail.com 0428 526 893

ACHM CATTLE POLICY

African Centre for Holistic Management

1. Build up cattle and small stock to maximum possible for land and wildlife restoration as the main tool of management of the environment. Obtain cattle from any sources while ranch itself owns relatively few. Gradually decrease outside cattle as ranch cattle ownership increases till 100% owned by ranch.

2. All outside owners of cattle allowed to bring in females or oxen only - no bulls.

3. Policy is to gradually build up our own herd from the mixed broad genetic makeup by closing the herd (meaning no more bull buying as soon as possible – when we think we can produce enough of our own bulls from “A” herd females explained below). Females will continue to come into ranch ownership herd after that point but not bulls.

4. With this closed herd approach we run A and B animals in the same herd but know which cows are A animals and which are B animals through record of their individual numbers. Most cows at present are B animals - which means we do not select bulls from their male calves. Those that are A cows (from records kept) are the ones from which we select future bulls. These A cow produce a good quality calf every year in the desired calving season without feeding or supplementing. Feeding and supplementing as in mainstream ranching results in selection for animals needing help and results in ever less locally adapted animals. Our breeding policy is aimed at selecting only for animals that thrive in this environment under Holistic Planned Grazing and without supplementing.

Heifers from all cows A and B obviously enter the herd but ONLY heifers from A mothers that produce can become A mothers unless they miss a calf when they go to B animals. Tracking the A & B animals is relatively easy from the records although all cattle are in one management herd.

5. Calving is planned to occur over 2 months beginning mid October to latest mid December. Calving in season although bulls are with cows all year is brought about by the culling program. Bulls all year in herd is to ensure normal social behaviour and lessen conflict.

6. Culling policy: Assume eventually culling 20% of cow herd annually to ensure average turnover in five years although some cows will grow older. Then aim is to cull that 20% in this order.

• No calf produced and reared (until A herd numbers are at peak required a cow that produced a good calf but lost it through no fault of her own can avoid being culled but later she would be culled regardless because it biases her ability to produce next calf over and above a cow that produces after raising a calf fully).

• Poor calf and or bad mother.

• Late to calve ie. calving so late in the required calving period that she will automatically be out of calving season in following year.

15

7. All efforts are being made to increase disease resistance through minimal dipping with products not killing oxpeckers, dung beetles, etc. New ideas to be constantly tried, such as herders literally painting Stockholm tar with an insecticide into ears, under tails, etc. and onto ticks while cattle in kraals.

Possible use of sulphur powder in ears etc.

8. All grazing is done using the Holistic Planned Grazing process and all plans are to be filed for record and future planning. Nothing in this plan excludes periodically having to run some animals separate on continuous grazing should there be a sound need. Or feeding some separately in side pen as long as they are not A animals and thus will be leaving the herd.

9. Nothing in this policy excludes commonsense in any emergency or other unusual situation. The policy that must be adhered to is the strict maintenance and build up till all are A animals – from which future bulls and breeding stock arise suited to the management and environment.

10. Ideally all ranch staff dealing with the public and trainees must be able to explain this cattle policy clearly and the reasons behind it. Because this strict policy goes against almost all conventional cattle breeding it will be questioned and challenged. It is not new and unique to ACHM but is taken from extremely successful ranchers and what they did in mainly the US and Mexico very successfully. Many ranchers tried to emulate their success but failed because they cut corners and did not stick strictly to such policy. In particular you are likely to be told:

That you have to supplement breeding cows. If you do so this ensures that those most using the supplement are more likely to breed successfully and thus you are gradually and unknowingly selecting the whole herd over time for those that need help. Costs can only keep increasing.

Second that if you keep your own bulls you will be inbreeding and they will mate with their own daughters. First we are not inbreeding with no selection we are inbreeding exactly as in nature with selection. For example was it six water buffalo that landed on Australia’s coast from a shipwreck and that led to a very healthy population of thousands. Or one pregnant rat reaching an island are producing thousands of healthy rats. Next if a bull has an active life of say five years in herd with say 6 bulls his chance of mating with his own daughter is 1:6 in his 3rd year and of mating with his granddaughter nil as she will be bred in the 6th year from her mother’s conception. And if the bull was there another year it is a low chance. That together with strict selection is adequate to heed the advantages of breeding for high production in our environment at low cost. If any of the conventional critics refer to bulls being present breeding with heifers too young that too has a response – we have two remedies. First accept it and cull those heifers if they do not produce a calf in their second year, or we can take young heifers and run them as a separate herd over critical time although we have not to date done that.

Alan Savoury The God Father of Regenerative farming

16

MASHONA

Adapted to withstand adverse nutritional circumstances, the Mashona performs even in the harshest conditions, due to their small size and low metabolic rate. As natural foragers, their resourcefulness is extraodinary.

MASHONA

17

MASHONA

The interaction between the animal and its total environment is of crucial importance in relation to its ability to perform and thrive in that specific environment. The Mashona, in common with other Bos indicus breeds, has evolved both anatomical and physiological adaptations to cope with the Central African environment, which in many instances mimics some Australian environments.

Firstly, the Mashona possesses certain adaptations which facilitate loss of heat from the body, therefore rendering it less susceptible to heat stress under conditions of high ambient temperatures. In comparison with Bos taurus breeds, the coat is smooth and glossy, thereby reducing insulation, and the skin is thick and movable and possesses numerous sweat glands and high vascularity to allow for rapid heat dissipation.

Heat loss is also enhanced by the large surface area per unit mass, with the skin surface area often being increased by extra folds in the region of the dewlap, neck, and scrotum. A further advantage is that fat tends to be deposited intramuscularly rather than subcutaneously, reducing any effects of tissue insulation. Moreover, Mashonas have a low metabolic rate, and under conditions of heat stress, there is less metabolic heat that can be dissipated.

A natural hazard for cattle in Zimbabwe is the high degree of ultraviolet radiation. The Mashona possesses a pigmented hide and secretes quantities of a substance called sebum from the skin, which spreads over the hair and acts as an ultraviolet filter. It is well-equipped to resist the damaging effect of ultraviolet radiation.

These include the formation of cancers, hyperkeratosis of the hide, and cancer of the eyelid, which can become a major problem in certain breeds. Bad inflammation of the skin due to photosensitivity can also become a problem in cattle with no pigment to their hides.

A major advantage of the Mashona is that it is tick-repellent. This is due to the thick hide, combined with well-developed sulcus muscles and a sensitive pilomotor nervous system. The hide will thus react more rapidly in the face of the slightest irritation, which is in marked contrast to breeds with longer woolly hair and thin hides. These traits make the Mashona resistant to physical tick damage and reduce their susceptibility to infection with tick-borne diseases. The same mechanisms that help repel ticks are also helpful in overcoming attacks from flies and other biting insects. The secretion of sebum is further believed to act as a form of fly repellent.

As the Mashona is adapted to the leached Mashonaland sourveld, with acid soils, both skeletal development and body size are small. Therefore, the maintenance requirements of cows are lower, and combined with a low metabolic rate, the chances of production and survival under adverse nutritional circumstances are better than for larger breeds. This is an important attribute of the dam in relation to specialised crossbreeding programmes.

There is no evidence that the Mashona possesses any special mechanisms for the digestion or utilisation of low-quality diets. However, the combination of their small body size and mobility, their ability to forage under conditions of high ambient temperatures and radiation, and their durable teeth, make them very efficient and selective grazing animals, particularly when compared with the larger Bos taurus breeds.

Moreover, the Mashona does show a natural propensity to browse, thereby making wider use of food resources. Many of the highveld tree species bear copious quantities of fruit and pods of high nutritive value. Freshly fallen leaves from deciduous species have been shown to have a crude protein content in excess of 10%. These natural supplements are readily sought after and play a significant nutritional role in late autumn and early winter.

Practical observations by Keith Harvey indicate that Mashona cows exhibit a high degree of urgency in their grazing and browsing behaviour and appear to get their fill and start ruminating early in the morning. This may well be due to adaptation to long hours of kraaling to which they were traditionally subjected.

Also, their very deliberate identification and selection of grass and browse species (by smell) varies with the seasonal patterns and may be influenced by a natural instinct to achieve a nutritional balance, particularly of protein. Certainly, the large variety of indigenous legumes that abound in the highveld and are usually regarded as unpalatable to bovines are readily taken on a seasonal basis.

The Mashona is a docile animal, and in contrast to some other Bos indicus breeds, both bulls and cows adapt well to handling. The relatively small body size further facilitates handling and management.

Under ranching conditions, the herd and maternal instincts are well-developed. Therefore, females tend to graze in groups, allowing for more efficient use of bulls during the breeding season. At calving time, a few matrons will guard the calves in a nursery area while their dams are grazing, and they serve to protect the calves and warn the rest of the herd if danger threatens. The bulls naturally take to single sire herds and exhibit herd control to a remarkable degree in much the same manner as certain polygamous antelopes like the impala.

Photos provided by: Adam Rabjohns & Mark Rossiter

Photos provided by: Adam Rabjohns & Mark Rossiter

19

Photo Credit: Johan Smit

Mashonas reach puberty at a relatively early age. Therefore, heifers can be bred early (14 months) if feeding and management are adequate. This will lead to greater lifetime productivity from females in comparison with those bred at a later age.

Females are sexually active and tend to resume activity soon after calving. The expression of oestrus is strong, which can prove to be a particular advantage of an artificial insemination programme. Males possess good libido and are very mobile under ranching conditions. The scrotum is adapted and designed to maintain the correct testicular temperature under sub-tropical conditions. Females are highly fertile, and a feature of the beast is that cows will give a consistently high overall calving percentage.

In common with other Bos indicus breeds, calving ease is a strong point of the cow, and if bred pure, calving difficulties are unknown.

Even with cross-bred calves, the birth mass is contained by the dam influence.

Combined with her high fertility, the Mashona cow is an excellent mother with a good milk supply. Scientific research has conclusively proven that the Mashona cow in the natural veld is unrivalled in weaner output per unit weight of the cow.

The adaptive traits of the Mashona render it particularly suitable for the efficient utilisation and maximisation of growth from the veld under more extensive systems of production. This ability may increase in importance in relation to the current trend in Zimbabwe, away from pen fattening to more extensive systems of fattening off the veld.

The main advantages of the Mashona are its high dressing percentage and the ability to fatten and finish at a low body mass because of its early maturity.

In addition, recent evidence has shown that the proportion of meat to bone and fat in the carcass is high.

The most economically important muscle in the carcass, the round or eye muscle, is particularly well-developed in Mashona males. As the Mashona lays down a high proportion of its fat in intramuscular form, this renders the meat juicier and more tender than in breeds, which deposit a greater proportion as subcutaneous fat.

Dr Mario Beffa

Head of Zimbabwe herd book, Member of Mashona Committee, Researcher.

Source:

Mashona Cattle Handbook, 2016. Originally Compiled and Edited by Dr David H Holness in 1992, Updated in 2016 with sections by Dr JJ Jackson and David Addenbrooke. Published by the Mashona Cattle Society.

21

Photo credit: Jaime Elizondo, Real Wealth Ranching

Our mission is to conserve, regenerate, and market Nguni cattle in Australia through herd recognition, education, promotion and fellowship.

Furthermore, through the Nguni's unique traits we hope to foster a symbiotic relationship between country, cattle and man. A relationship which results in the well-being and regenerative health of land, animal and human.

What we offer:

- Community and Membership

- Stud/Breed Inspection

- Genetic Conservation

- Genetically Diverse Polled Genetics

- Full Blood Maternal Lineage

- Stud registered with the Nguni Cattle Breeders Society of South Africa

- Breed Education

- Full Blood Bulls available to improve hybrid vigour in cross breeding operations

- Semen available from both polled and horned animals

Nguni Club in Australia endorsed by The South Africa Nguni Cattle Breeders Society

Ed

0429 652 718 Hentie Martens 0490 100 039 Kc Dechaud 0477 884 668 Exceptional Fertility • Excellent Maternal Instinct • Longevity • Placid Temperament • Low Input Resistance to Harsh Environments • Tick and Parasite Resistant • Low Environmental Impact

Rous

Nguni Australia works alongside other breeders to ensure the purest Nguni Genetics are preserved for future generations. nguni.au

NGUNI

Said to be one of the most profitable cows in the world, the Nguni is known for its good temperament, heat and light tolerance and its ability to handle extreme heat as well as cold temperatures. Hardy and adaptable, the Nguni possess excellent parasite resistance.

NGUNI

23

NGUNI

The Nguni breed is a naturally fully adapted breed of cattle (Bos Taurus Africanus) from the Southern Hemisphere. This 6000-year-old breed from Africa has a stable, dominant, and well-adapted genome that has brought many benefits to the Australian beef industry.

In 2004, Doug Paton, Richard Gill and Gabriël Roux imported Nguni embryos from South Africa, started Nguni breeding programs and established the Nguni Society of Australia (ANBI). Two other independent breeders, Edwin Rous and G T Ferriera also contributed significantly to the genetic pool in Australia.

Unfortunately, the small 6-year window closed in 2011 due to an outbreak of Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) in South Africa. However, an excellent and wide base of Nguni genetics has been established, with various programs in place to preserve and expand the genetic versatility of the breed. This includes the great initiatives of Sanga International.

The Nguni Breed flourishes in arid, harsh conditions, with cold winters down to -8ºC and dry, hot summers up to 40ºC with annual summer rainfall of 300 millimetres. This breed can adapt to long periods of drought and to all grazing conditions, from high rainfall to low rainfall.

Their adaptability allows them to thrive, produce and survive in different climate conditions.

These animals, through natural selection, define the ideal cattle weight for the harsh Southern climate: bulls weigh 600-700kg, and cows weigh 250-350kg. They are resourceful foragers and regularly include leaves, shrubs, bark, berries and even weeds in their diet. This results in a great capacity to survive droughts and eliminates supplementary feeding.

Being ‘flat-boned’ with light skeletons, it reduces trampling of grass and allows for long-range water access. This also ensures a greater deboned weight-todressed weight ratio, providing, on average, 15% more meat to the butcher per dressed carcass.

The Nguni is a maternal line breed and is certainly one of the most fertile breeds under harsh grazing conditions with low mortality and high longevity; they calve easily and have excellent maternal qualities. The Nguni cow limits the size of the foetus and together with the characteristic sloping rump, the cows calve easily. She can properly raise the calf of a meat breed bull, with greater income per hectare guaranteed. This outstanding cow efficiency ensures a weaned calf with easily 50% and more of her own weight.

Good pigment on the skin protects the skin from ultraviolet rays from the sun. As mentioned, longevity is a very important characteristic of the Nguni cow and some cows reach 18 years old.

ngunibreeders.com.au

Maternal qualities are very strong. She will protect her calf with her life from predators.

The fertility of Nguni cows approaches 100% with the expectation of one calf every year. The Nguni pelvis is problem-free and will easily calve from any large-framed bull. Their udder is well-attached with plenty of milk and decent teats: pendulous, lowhanging udders or bottle teats are rare. Nguni cows grow very old and can be expected to calve until age 16 or older. The Nguni is naturally resistant to internal and external parasites. This is due to natural selection over the centuries in Africa. Farming with Nguni cattle remains a low-cost operation with little or no use of dosing agents and vaccinations.

The challenge is to build your own high-quality Nguni breeding herd - either pure Nguni cows or high-grade crossbreeds bred with top-quality Nguni bulls. This herd is well-suited for dry regions and organic farming. Next, choose a large-frame Bos Taurus bull of your choice (consider artificial insemination if the climate is too harsh). Take all offspring to the market to take advantage of the generous hybrid vigour.

Registration Options for Nguni: Establish and register your own Nguni stud with purebred cows and bulls. Establish and register your own Ausguni stud by enrolling in a F5 crossbreeding program. Establish and register your own Solera breed using Nguni as the foundation genetics.

Tradition in Australia has it that a large carcass = large profits. Cattle farming is just another business. Profit = Yield in kg/ hectare per year minus inset costs.

Turnover is King, and low inset cost is Queen.

Article provided by Gabriel Roux & Freddie Besselar

Article provided by Gabriel Roux & Freddie Besselar

25

Photos provided by: Gabriel Roux & FJ Besselar

27

Lizette & David Basson +61 437773537 / +61 418404441 bassonbdry@gmail.com 248 Mount Russell Rd, Mount Russell, NSW FARM SUNSET DOWNS AUSTRALIA

2 Y/O BONT BULL BOORALEE SINGITI

BORAN

Renowned for their distinct humped appearance, the Boran are recognised for their high fertility, excellent temperament, good mothering ability, disease resistance and their incredible survivability in the harshest of conditions.

BORAN

29

BORAN

The Boran cattle breed is a historically unique, pure cattle breed. Boran cattle have a distinctive genetic composition focused on production, reproduction, body structure and composition.

Boran cattle are part of the Bos Indicus Cattle Group and were introduced to Africa shortly after the Arabian invasion around the 700s and first identified in the Borana Plateau in Southern Ethiopia. The Borana plateau has high-altitude climate conditions and regular harsh droughts. The Boran comprises 64 % of Bos Indicus, 24 % of Bos Taurus, and 12 % of Africa-Bos Taurus. The Boran has characteristics that are compatible with arid conditions in Australia.

This breed has flourished in diverse African environments and will benefit Australian beef and cattle production. The Boran has high-quality meat with low input costs, as they perform well from paddock to plate and have the ability to be rounded off with little input at feedlots due to the rumen capacity and ability to convert feed into fuel and muscle growth.

The attributes of the Boran are what shape the structure of their performance, including high tick resistance, low susceptibility to diseases and their ability to adapt and thrive in sudden changes to climate (green and lush to drought conditions).

Boran have strong herd and mothering instincts and are protective against any form of predation. At the same time, they have a docile temperament, high fertility, even in drought conditions, and longevity. Most importantly, Boran are efficient with poor and lowquality feed (2-4 % Dry matter and digestibility percentage) into kilograms of meat production with early maturity (maturity as early as 14-16 months) and the ability to reproduce. Boran cows of 15 years are still highly fertile and produce excellent offspring. A 16-year-old bull produces excellent, highly fertile sperm with 80-90% sperm quality.

Carcass maturity and traits are evidenced by a large rumen capacity, supporting the body depth and their ability to fatten evenly and grow eye muscle capacity.

Boran cattle come in a diverse range of colours; however, the main colours are white, grey, and fawn in the body with light and dark brown shading in the neck, shoulders and hindquarter regions, black hooves and black muzzle. The Boran has small ears and a distinctive hump on the back (ranging from small to large).

Borans have larger and more sweat glands than the cattle breeds of Australia, allowing them to withstand high humidity and high temperatures.

Thus, they perform excellently in drought conditions and regions of significantly low temperatures and the ability to walk long distances in heat conditions, withstanding water stress.

Boran cattle were introduced to Australia by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) from 1990 to 1991 through the importation of embryos and semen (Australian Boran Cattle Incorporated, 2020). The first embryos were implanted in 1992, and the first international Boran were bred. The aim of the study trial was to find a Zebu cattle breed similar to Brahman, but unrelated and with different genetic composition. The traits of key interest that led to the Boran being the chosen breed were adaptability to hot, dry climates, unexpected drought survival ability, the hybrid vigour for potential crossbreeding, and fertility. Another trait that was regarded as beneficial was the ability of the Boran to survive and thrive on low-quality feed.

Over the years, the Boran has continued to survive and thrive in Australian conditions. This led to the establishment of the Australian Boran Association, now known as Australian Boran Cattle Incorporated (Australian Boran Cattle Incorporated, 2020). The breed has a superior level of resistance to insects.

This is due to the shorter hair coating, which makes it difficult for insects to attach themselves, and secondly, having a higher waxy oil-like layer on the skin, reducing the attachment of ticks and biting flies.

The Boran Cattle rest on average 2% of the time as opposed to Bos indicus and Bos taurus, which spend on average more than 4% and 10.12%. This high grazing time of the animal demonstrates they have the behavioral ability to utilize pasture feed efficiently. They ingest, digest, and break down consumed feed, and turn it into body and growth quicker than other cattle breeds.

The unique traits, characteristics, and performance of the Boran cattle make them an ideal candidate for climatic and environmental conditions in Australia.

Article provided by Melissa Fourie

Sources:

Australian Boran Cattle Incorporated. (2020)., Australian Boran Cattle.

Bayssa, M., Yigtem, S., Betsa, S. & Tolera, A., (2020)., Production, reproduction, adaption characteristics of Boran cattle breed under changing climates.

Boran Cattle Breeders Society of South Africa. (2012)., Boran Cattle SA.

Boran Cattle Breeders Society. (2023), Kenya is the home of the pure Boran breed.

De La Vida Borans. (2023)., Origin & genetic makeup of the Boran.

Venter, Y., (2021)., Die Boran: Uniek geskik vir die Suid Afrikaanse omgewing.

31

Photos provided by: David & Lizette Basson

CPC’s Kenyan sourced Borans are a total outcross giving unbelievable hybrid vigour - Highly fertile - Fast young growth - Bred to thrive in harsh conditions Contact: David Young: 0428 257 686 | livestock@pastoral.com bred to breed

Polled pure Boran Polled pure Boran

Boran cross Angus PTIC yearling heifer

Yearling pure Boran heifer

Boran cross Angus yearling bull, ready to work

Bulls that work 365 days a year

DRAKENSBERGER

Known for their high-grade beef, significant carcass and their iconic smooth, black coat, the Drakensberger offers traits such as calving ease, high fertility, quality milk output and exceptional maternal instincts.

DRAKENSBERGER 33

DRAKENSBERGER

The Drakensberger (Draks) is indigenous to South Africa. The Drakensberger was acquired by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1497, making this year the first time the cattle breed was recorded in history. The Drakensberger has been developed over a few centuries. Initially, this cattle breed went by the name Vaderland cattle for some time until the name was changed to Uys cattle after the Uys family worked to improve and maintain the quality of the breed. In 1947, the breed was officially renamed the Drakensberger after the region where the cattle roamed and flourished.

Known as extremely hardy and adaptable, the Drakensberger has developed a natural resistance against tick-borne diseases. Coats are sleek and shiny, repelling insects that could cause infections or illness and reflect heat, helping the animal stay cool in hot climates . “Draks” have short, strong legs, which makes them good walkers on rough terrain and steep hills. Their heavy brows protect them from the sun’s rays, and they have exceptional muscle definition.

The Drakensberger cattle have an easy temperament and are quite docile. They are easily handled and raised by breeders.

This cattle breed can live over 14 years, remaining productive for most of their lives. Cows have a high fertility rate and give birth to calves easily. Calves have a fast growth rate due to the quality and quantity of their mother’s milk but continue to gain weight quickly after weaning. All these characteristics support this cattle’s title of being a “profit breed.”

Draks have a significant carcass, making it on the top 10 list of highest quality beef in South Africa and is recognised as having high palatability. Outside of South Africa, Draks are found in Australia, where they have

been bred and are well received by many committed breeders who have bred them successfully in arid areas. While this cattle breed has high milk production, the Drakensberger is not used for commercial milk production.

Trials conducted by JF de Bruyn et. Al. (1989), on different breed groupings viz., Zebu-, British-, European breeds and the Drakensberger, showed the Drakensberg to have the juiciest and most tasty (flavourful) meat with the best cut ability. The dressing percentage was second only to the European breed whilst statistically higher than that of the Zebu and some British breeds.

Drakensberg cattle are a medium-frame breed with a long and deep body and a smooth black coat. Their horns are short and curved and there are also polled animals within the breed. Mature bulls can weigh a ton or more, while cows weigh less, with a range of 500-700kg. There has been successful crossbreeding, and the breed’s ability to cross with both Bos indicus and Bos taurus breeds is well known, making it exceptionally suitable as a mother-line breed in crossbreeding systems.

Effort and care has been put into maintaining the purity of the Drakensbergers by South African cattle breeders in Australia after embryos were sent to Australia in 2004 and 2009. The Drakensberger cattle have adapted to extreme heat and subzero temperatures. These cattle thrive on even low-quality foraging in rough terrain.

Article provided by

Martin Luitingh

35

Drakensberger Calf size compared to Tuli cow

Email: martinl@coramchambers.com.au

SOLERA SOLERA

The ‘Trifecta Performance Breed’ - Solera combines the best traits of Bos Africanus , Bos Taurus and Bos Indicus to maximise hybrid vigour. Showing impressive results in all areas, Solera can be tailored to suit your environment, whether it be temperate, coastal or arid.

37

SOLERA

As the global climate crisis intensifies, agriculture faces a reckoning with the new ecological reality. From prolonged droughts to intensifying bushfires and biodiversity loss, Australia’s $28 billion beef industry confronts an existential crossroads. However, an innovative solution born from cutting-edge animal science is emerging - the Solera cattle composites driven by Sanga International.

Solera represents the world’s first “environmentally adaptable breed,” developed through a pioneering process called “Trifecta Performance Breeding.”

This genomic program combines the genetic excellence of African cattle genetics (Bos Africanus) with the best traits of existing Australian breeds (Bos Taurus and Bos Indicus) into a revolutionary new hybrid. The resulting ‘Solera’ breed possesses a profound resilience capacity, imbued with exceptional traits like heat tolerance, disease resistance, efficient nutrient cycling, and adaptability across diverse terrains, vegetation, and water sources.

Physically, Solera cattle exhibit desirable qualities that are perfectly suited for low-stress livestock management and

low-cost, high-quality beef production. With substantial carcasses, tight sheaths, slick skin, high fertility rates, and elevated meat-to-bone ratios, these animals can thrive in the most unforgiving environments while maximising outputs of premium beef and milk. Furthermore, their even-keeled dispositions harmonise with regenerative multi-paddock grazing models rehabilitating degraded lands.

From an economic perspective, Solera facilitates a sustainable operating model by dramatically reducing overhead costs. Their robust health and carefully calculated breed compositions minimise treatment requirements and nutritional inputs while allowing for accelerated herd expansion. This low-maintenance, highyield model drives profitability while future-proofing operations against climate volatility.

Solera’s breakthrough breeding approach enables producers to bioengineer region-specific herds optimised for their unique geography. Whether navigating arid, coastal, or temperate conditions, the optimal traits can be tailored using proprietary breed composites - Temperate (75% Bos Taurus, 25% Bos Africanus), Coastal (50% Bos Taurus, 25% Bos Africanus, 25% Bos indicus), and Arid (25% Bos Taurus, 62.5% Bos Africanus, 12.5% Bos Indicus).

Photo credit: Jerry Addison - Texas

From an environmental stewardship perspective, Solera aligns beef production with sustainable principles. Their tropically-influenced genetics allow Solera cattle to thrive in hotter, more variable climates while producing less methane. Simultaneously, their adaptive multi-paddock grazing patterns and hoof-aerating impacts actively regenerate soils, sequestering carbon while enhancing biodiversity and water conservation.

As current practices grow increasingly unviable amidst Australia’s ecological shifts, Solera represents a vital catalyst for revitalising the nation’s beef supply chain. By integrating this nature-positive cattle breed, developed in Australia for grassfed, low carbon intensity beef, Australian producers can transition to a new climateresilient model. One that prioritises ethical, humane farm-to-fork standards, economic viability, premium product quality, and environmental stewardship.

In confronting the existential threats of climate change, bold adaptation will be required across all sectors. Through the Solera breed, Australia’s beef industry can forge a nature-positive path forward, cementing the nation’s leadership in sustainable, ethical protein production for generations to come.

Article provided by The Solera Board

39

THE ENVIRONMENTALLY ADAPTABLE BREED

Tailor your herd to your environment within the Solera framework

25% BOS TAURUS 50% SANGA 25% BOS INDICUS COASTAL 25% BOS TAURUS 62.5% SANGA 12.5% BOS INDICUS ARID 75% BOS TAURUS 25% SANGA 0% BOS INDICUS TEMPERATE

SOLERA

AFRICANUS

Breeds

Euro Breeds

INDICUS Brahman Boran

Brangus

Belmont

Bonsmara 25-37% TAURUS <25% INDICUS 50-75% SANGA

BEEF

BOS

Tuli Mashona Nguni Nkone Drakensberger BOS TAURUS British

Wagyu & Akaushi

BOS

Santagertudis Braford Charbray Simbrah Stabilizer Eldorado Speckle Park

Droughtmaster

Red

ACCEPTED COMPOSITES NATURE-POSITIVE

OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS FOR AFRICAN BREEDS IN AUSTRALIA

Don Nicol - Breedlink

What can Sanga breeds offer the Australian beef producer; but first a bit of history.

From the 1930s, cattle researchers in Australia, the USA, and South Africa have evaluated different tropical cattle breeds to determine their potential to join with the foundation British beef breeds to produce an animal that could thrive in the tropics. That research led to some crossfertilisation of ideas in utilising Brahman (Zebu) and the Sanga breeds in the tropics.

Interestingly, African cattle first arrived in Australia with the First Fleet in Sydney in 1788. There is talk in the history of black cattle that were loaded onto ships at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. The NSW colony cow herd was subsequently developed from these original imports.

Sanga breed genetics imported into Australia include Africander, Boran, Tuli, Mashona, Drakensberg and Nguni.

CSIRO importation of Boran and Tuli - In the late 1980s, CSIRO, with a consortium of graziers, imported frozen embryos of the Boran and Tuli breeds from Africa (Zambia and Zimbabwe) via the Cocos Islands, where they were implanted into Australian recipients.

74 calves of the breeds were later imported to the mainland. The importation process was logistically complex but, in the end, successful. They had imported the genetics of the Boran and Tuli breeds specifically because of the similarity of the African continent to Australia, the similarity in climate and the ability of the breeds to produce and survive in harsh environments.

The timing of the sale and release of animals of the Boran and Tuli breeds to industry, after comprehensive research on both breeds by the Tropical Beef Centre at Rockhampton, did not immediately lead to a strong take-up by the northern industry. In Central and North Queensland, 300kg of dressed weight quickly became a reference point for bullock producers at that time. This carcass weight was achieved at a turn-off at two and a half (rarely), three and a half, or four and a half years. The market was moving away from full-mouth bullocks. Based on the smaller size of the two African breeds, Queensland producers did not clearly see a role for them.

Ironically, the smaller mature size can now catalyse renewed interest in the two breeds and other Sanga breeds.

Belmont Red - Africanders were part of the earlier breed comparison program conducted by CSIRO in northern Australia, near the Tropic of Capricorn. The research showed that the Africander cross HerefordShorthorn line was the most productive of all the lines at Belmont Research Station. This led to the release of the Africander cross line to the northern Industry as the Belmont Red in 1968. The breed has cemented its place in the northern beef industry with very successful bull sales in recent years. The breeders have also selected strongly for polledness in recent years.

Comparing the Traits by Breed Type - Table 1 shows the traits the African breeds bring to a breeding program compared to Bos taurus breeds in Tropical and Temperate environments. The table shows the comparative ranking by trait and breed type. The table was compiled by Dr Heather Burrow, then of CSIRO, from various breed trials comparing breed types and an F1 cross.

It can be seen that the Sanga and African Bos indicus (Boran) breeds have the profit driver traits of moderate mature size, fertility, heat resistance and drought tolerance which are key traits when designing a crossbreeding program.

A Temperate environment is assumed to be one free of environmental stressors, whilst tropical environment rankings apply where all environmental stressors are operating. Hence, while a score of, for example +++++ for fertility in a tropical environment indicates that breed type would have the highest fertility in that environment, the actual level of fertility may be less than the actual level of fertility for breeds reared in a temperate area. Due to the effect of environmental stressors that reduce reproductive performance.

B Principally meat tenderness.

C Rhipicephalus microplus

D Specifically Oesophagosromum, Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus and Cooperia spp.

E Data from purebred Continental breeds are not available in tropical environments and responses are predicted from the CSIRO Rockhampton crossbreeding data. 1African Bos indicus = Boran 2Indian Bos taurus= Brahman

Boran x Angus calf in Central Queensland Photo credit: P. Lewis Trait Bos Taurus Bos Indicus F1 Brahman x British Tropical Bos Taurus Breed Type British ++++ ++++ Continental Sanga Indian African TemperateA Growth Fertility +++++ +++++ ++ ++ +++ ++ ++ ++ + +++++ +++++ ++++ ++++ ++ ++ +++ +++ ++ + + +++ +++ ++++ +++++ +++ +++++ +++ +++ +++++ +++++ ++++ +++ ++++ +++ +++ ++++ +++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ ++ +++ ++++ ++++ ++ ++++ ++++ ++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ ++++ ++++ +++++ ++++ ++++ +++++ ++++ ++++ +++++ ++++ ++++ Growth Fertility Mature Size Meat QualityB Cattle TickC WormsD Eye Disease Heat Drought TropicalA Resistance to environmental stressors 43

FUTURE PROOFING YOUR HERD AGAINST CHANGING CLIMATE

Don Nicol

Breed cattle adapted well to your environment to protect your herd against changing climate. Constant high heat and humidity levels can lead to pregnancy losses under open rangeland grazing. Breeding for future environments is the key word here, not for a couple of years but for a few generations into the future.

The science is in; it can be clearly stated (Table 1) that the Sanga breeds deliver important genetic packages of tropical adaptation genes, heat tolerance, moderate size (very important), easy calving, high fertility, and early puberty (weaning rate %) - all profit drivers.

Sanga bull buyers will tend to be producers focussed on kilograms per hectare rather than increasing kilograms per head. Followers of Regenerative Agriculture, holistic farming systems, and proponents of low input, low or no -chemical, time-controlled grazing systems should also consider the Sanga breeds whether it is a bull for crossbreeding or purebreds. There are bull breeding opportunities here too.

Sanga Composite Role - Like the Africander years earlier combining with Hereford and Shorthorn for a three-breed composite, the Belmont Red, Tuli and Boran were also chosen as contributing breeds for some tropical composite programs, largely developed by more integrated pastoral companies.

Unlike the sheep industry, where crossbreeding and composite breeding is commonplace, in beef, the purebred still prevails. Sanga genetics still plays a strong role in new composites, especially in the tropics.

Crossbreeding with a Sanga - If you want to lower greenhouse gas emissions by breeding more efficient, more productive cattle, crossbreeding Brahman or Brahman-derived cows, and Sanga bulls offer progeny where both males and females are highly adapted and because the breeds are genetically separate, a high level of hybrid vigour is gained.

The author has recommended Boran bulls to downsize the progeny of purchased, tallframed Brahman cows that had heavy mature weight.

In addition to reducing mature size in replacements, it also introgresses significantly earlier puberty. The popular saying” it’s not the cow! It’s the how” is not true when the cow is large framed with high maintenance requirements and a ‘spotty’ calving history. Reducing stocking rates for larger cows that consume more forage than smaller cows is a key factor in determining profitability.

Moving forward

Collaboration and cooperation between breeders of the different Sanga breeds is critical to increase the visibility of the breeds and their profit traits. Multiplication of the current population of Sanga seedstock to commercial numbers will require strategic use of IVF (in vitro fertilisation).

Don Nicol Breedlink

References:

H.M. Burrow Animal (2012), 6:5, pp 729-240 ‘Importance of adaptation and genotype X environment interactions in tropical beef breeding systems’.

Boran x Brahman bull downsizing project in Papua New Guinea

44

ONLINE ACCOUNT FOR COMPLETE ANIMAL MANAGEMENT NATIONAL MULTIMEDIA BREED ADVERTISING PERFORMANCE PREMIUMS AND MARKET ACCESS QUALITY HEAT TOLERANT GENETICS PERFECTED BY NATURE INVITATION TO PARTICIPATE AT ANNUAL NATIONAL SALE THE BREED OF CHOICE FOR A LOW CARBON, WARMING CLIMATE 14 MANDATORY TRAITS RECORDED FOR ALL SALE ANIMALS CERTIFIED BREEDER WWW.SOLERABEEF.COM A GLOBALLY CO-ORDINATED BEEF BREED. CALL 0434 678 228 TO FIND OUT MORE CONSISTENT ~ PRODUCTIVE ~ RELIABLE FROM CONCEPTION TO CONSUMPTION Breed Society Members Registration Guide Register on AgPro Technology web portal using the link above or QR Code to the right 1 Choose Single Farm to automatically create and link your first property to Sanga International 2. (You can change this later if you manage multiple properties) a Choose AgPro Grazier account type 3 On the dashboard, click the link New Graziers - Upgrade your free account to an AgPro Grazier subscription 4 Pay online with credit card to activate your AgPro Grazier subscription upgrade 5 You are now ready to import your animals, pedigree, and observations, along with access to the AgPro Livestock Index reports Your farm data is shared with the Sanga International board to verify breed pedigree 6. https://au agpro technology/Register?referral=Sanga+International 45

THE BRUNSWICK HOTEL

SANGA CLUBHOUSE FOR BEEF WEEK ROCKHAMPTON 2024

SANGA CLUBHOUSE FOR BEEF WEEK ROCKHAMPTON 2024

THE ENVIRONMENTALLY ADAPTABLE BREED

Tailor your herd to your environment within the Solera framework

25% BOS TAURUS 50% SANGA 25% BOS INDICUS COASTAL 25% BOS TAURUS 62.5% SANGA 12.5% BOS INDICUS ARID 75% BOS TAURUS 25% SANGA 0% BOS INDICUS TEMPERATE

SOLERA

BOS AFRICANUS Tuli

TAURUS

Breeds

& Akaushi Euro Breeds

INDICUS Brahman Boran

Park Brangus

Belmont Red Bonsmara 25-37% TAURUS <25% INDICUS 50-75% SANGA

NATURE-POSITIVE BEEF

Mashona Nguni Nkone Drakensberger BOS

British

Wagyu

BOS

Santagertudis Braford Charbray Simbrah Stabilizer Eldorado Speckle

Droughtmaster

ACCEPTED COMPOSITES

Jack Milbank

Jack Milbank

Photos provided by: Adam Rabjohns & Mark Rossiter

Photos provided by: Adam Rabjohns & Mark Rossiter

Article provided by Gabriel Roux & Freddie Besselar

Article provided by Gabriel Roux & Freddie Besselar

SANGA CLUBHOUSE FOR BEEF WEEK ROCKHAMPTON 2024

SANGA CLUBHOUSE FOR BEEF WEEK ROCKHAMPTON 2024