9 minute read

Holst betting big on the foil battery

Credit: Holst Centre

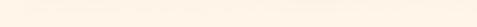

Can billions of micropillars make for a better battery than we currently have? Yes, Holst Centre believes, after the fi nal piece of the puzzle fell into place in the lab recently. Now, the institute is looking to scale up and commercialize the technology.

Advertisement

Paul van Gerven

Abattery can always do better. It can be cheaper, it can hold more energy, it can charge faster or it can have a longer life span. So, naturally, battery makers are constantly looking for ways to improve their product and gain an edge over the competition. No doubt, a lot more performance can be squeezed from the familiar electrochemical cell. Still, engineers at Holst Centre feel that in the long run, a transition to a radically di erent design will get us much closer to the perfect battery. Having made promising strides in the lab recently, the research institute found funding to prove its concept works on a larger scale and can be mass-produced. e futuristic battery Holst Centre has been working on for about ve years already is called a 3D solid-state thin- lm lithium-ion battery. It consists of a foil, covered with an array of micropillars, each coated with thin layers of battery materials: lithium-storing electrodes sandwiching an electrolyte. For simplicity’s sake, consider each pillar to be a tiny battery in itself. e main challenge is to make enough pillars – billions and billions of them – so that together, they make up a full- edged battery. is design has several advantages. First, compared to regular batteries, the lithium ions need to travel only very short distances, translating into faster charging and de-charging times. Secondly, there’s no liquid electrolyte involved, meaning a longer life span and little to no danger of res or explosions. And thirdly, the design is inherently lightweight. e Dutch Ministry of Economic A airs & Climate Policy and the province of North Brabant, home of Eindhoven-based Holst Centre, are sold. ey’re providing the research institute with 3 and 1.5 million euros, respectively, to set up a small-scale production line to demonstrate the viability and commercial potential of the technology.

Not waiting for the results to come in, Holst Centre will go ahead and start a company to commercialize the technology. “ e battery world is highly competitive. We simply can’t a ord to go one step at a time if we want to bring this to the market, eventually,” explains Holst Centre director Ton van Mol.

Troublemaking

Since the patents haven’t been led yet, Van Mol can’t go into the details of how the battery-on-foil is made. But, in broad strokes, rst, an array of micropillars, each measuring a few microns in diameter and 100-200 micron in height, is grown on the foil. Next, they’re coated with the layers of battery materials using atomic layer deposition (ALD). is deposition technique is excellent at growing well-de ned (multi-) layers on complex structures. However, in its traditional form, it’s batch based and hence not ideal for high-throughput production. Fortunately, this is one area of specialty of the Eindhoven region.

ALD, in general, involves sequentially exposing a substrate to di erent gases, which react with the surface in a self-limiting fashion, thus ‘coating’ it, literally, atomic layer by atomic layer. In traditional (temporal) ALD, a stationary substrate is placed in a reactor vessel, which is repetitively lled and emptied. Over a decade ago, however, Holst Centre’s parent organization TNO (and, separately, the company Levitech) developed a continuous ALD process, in which the substrate moves past the di erent gasses. is so-called spatial ALD (SALD) achieves much higher deposition rates and is compatible with high- throughput techniques like roll-to-roll processing.

TNO originally developed SALD for solar cell manufacturing, but over the past few years, it has been working on expanding its range of applications. TNO spin-o Saldtech is now working on OLED displays and SALD (a company with roots in TNO as well) is exploring a number of applications, including batteries – ‘traditional’ batteries, that is.

Holst Centre previously upscaled SALD to large-area roll-to-roll processing for a variety of materials. Still, it had to nd out if it could also deposit the necessary thin- lm battery materials using the technique. e nal piece of the puzzle recently fell into place when SALD deposition of lithium phosphorus oxynitride (LiPON) was demonstrated. is material serves as the solid-state electrolyte in the 3D solid-state

thin- lm batteries but could also be applied in traditional batteries. After all, the battery industry would gladly get rid of the troublemaking liquid electrolyte as well.

Heavily subsidized

Holst Centre is currently in the process of drawing up the speci cations of the production equipment. After the tools have been manufactured and installed, the search for a viable production approach for thin- lm batteries can begin. All in all, Van Mol estimates Holst Centre will need one and a half to two years to deliver the rst working batteries. Soon afterward, Van Mol hopes to start working with companies to show the technology can deliver on their requirements. “We consider wearables to be a good entry market, but our calculations show our technology can be applied in almost every battery market, even electric vehicles,” says Van Mol.

It will be a rocky road, though, Van Mol admits. “We’re working at the cutting edge of what’s technologically possible, so success is by no means guaranteed. But, in my opinion, betting on a next-generation

Credit: Holst Centre

technology like this is a much better way for Europe to catch up in battery manufacturing, rather than heavily subsidizing factories that are practically the same as those already operating in Asia.”

The future is closer than you think

You want your company to stand out, but how? You’ll need specialists who can share their thoughts at every level. With creativity, dedication, and lots of knowhow, NTS helps its customers find the ultimate solution to every problem.

We specialize in developing, manufacturing, and assembling (opto-)mechatronic systems, mechanical modules, and critical components. Our expertise? Precision and maneuverability.

From the initial design to the prototype, all the way to assembly — our comprehensive support helps customers realize their ideal product faster. NTS excels in solving complex issues. Leave it to us to design and create an application that’s exactly what our customer was looking for. With our versatile knowledge and wealth of experience, we help accelerate technological innovations.

The technology of the future? With NTS, it’s at your fingertips.

nts-group.nl/career

Our (opto-)mechatronic systems and mechanical modules contribute to future technologies

Anton van Rossum anton.van.rossum@ir-search.nl

Ask the headhunter

V.C. asks:

After an international sales career of 20 years, of which 15 years in the semiconductor industry, I settled again in my hometown in the Netherlands. ere’s no place like home! We moved there at the beginning of this year, just before the Covid-19 pandemic broke out. Since then, I’ve been working remotely for my employer. No one goes to the o ce anyway and traveling to customers is very limited. As I don’t think this will be sustainable much longer, I’ve agreed with my CEO to look for a position outside the company.

Following my MBA 20 years ago, I switched from a sales job in the Netherlands to a position as a sales and marketing executive at an international distributor of electronic components in Italy. After a few years, I came into contact with my current employer, a medium-sized semiconductor company with (at the time) a less thriving position in a few niche markets. I started there as an account manager and have grown into a European sales director and member of the board of directors. To continue my growth in this company, I would have to move to the US, but – as said – I prefer to work in the Netherlands.

Problem is that my business network here has become less strong due to my long stay abroad. I also know very little about the local chip scene. Recently, I saw a vacancy for a marketing manager at a large semiconductor company in the Netherlands. I’m thinking of applying but I’m hesitant: the position is below my level and I cannot leave con den

Try to build a network first

tial information about my current employer in the hiring company’s general application system. Yet, I’d like to get in touch.

How do you compare the vacancy to my current position? Could it help me progress my career? Do you happen to have a contact there or can you mediate in a rst step?

The headhunter answers:

When you’ve been away from the Netherlands for so long and hardly have any contacts in the semiconductor industry here, it doesn’t hurt to start with scrutinizing the eld. You can of course apply for this position, which is indeed far below your level, but that might harm your interests in the long run. Each position is to some extent career furthering, but they want to ll the vacancy now and not start again in 6 months.

My advice to you is to try to build a network rst. ere are various ‘platforms’, such as fairs, organizations and lectures, you can use to make valuable contacts. You can also choose to directly reach out to the management of potential employers to explore opportunities. You’ll understand that this takes time and perhaps some perseverance.

It isn’t clear to me what con - dential information about your employer you’re referring to. When you want to get a managerial commercial position elsewhere, you inevitably need to show something of your market knowledge, know-how and added value. Evidently, you don’t share turnover gures and details from commercial agreements, but you don’t have to be secretive about what can be gathered from public sources, such as products, markets and distribution channels. It’s good to show your loyalty to your present employer and your sensitivity to the subject, but too much restraint will hinder your opportunities.