7 minute read

Bringing high-performance motion systems to a whole new stage16 Bringing high-performance motion systems to a whole new stage16 Bringing high-performance motion systems to a whole new stage16 Bringing high-performance motion systems to a whole new stage

Bringing high-performance motion systems to a whole new stage

In the world of high-performance machine development, the Netherlands is planted fi rmly on the cutting edge – particularly in the fi eld of chip-making equipment, used in the semiconductor and electronics domain. To stay ahead of the ever-evolving demands and consumer expectations, key players in Dutch high tech are teaming up as part of the Imsys-3D public-private partnership to create next-generation high-performance motion systems.

Advertisement

Collin Arocho

When it comes to the world of silicon, the chips that are feeding the electronics boom, Dutch equipment and machine builders such as ASML and ASMI are planted at the top of their elds, globally. However, to keep a competitive edge in the production of state-of-the-art machines, companies like these must balance their customers’ current needs with innovation. anks to the public-private partnership of the Imsys-3D project, high-tech equipment makers are getting a big boost in planning for the future, as collaborators utilize cutting-edge technology to develop new and improved methods to build next-gen high-performance motion systems.

For the high-tech equipment industry, high-performance motion systems are a vital piece to the puzzle. However, to meet future performance targets and time-tomarket demands, new design-optimization methods are much needed. Enter the Imsys-3D project team, which includes Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), mechatronics and motion control specialist MI-Partners, the industrial 3D-printing equipment manufacturer Additive Industries, lithography systems provider ASML and software company In nite Simulation Systems. “Our goal for this project is to use computers to generate new designs for a wafer stage automatically,” explains Arnoud Delissen, PhD student at TU Delft. “By using unique algorithms, computers can design optimal shape and dynamic properties, which can then be 3D-printed, o ering never before realized e ciency – allowing industrial partners to work toward the next generation of machines.”

Precision

In chip manufacturing equipment, the wafer stage, also called a chuck, is a crucial positioning module in the chip-making process. When the large disk or wafer of silicon

Imsys-3D

As part of the Imsys-3D project, Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), MI-Partners and Additive Industries joined forces, together with ASML and In nite Simulation Systems, to create a next-generation, 3D-printed wafer stage for improved performance and accuracy in the chip-making process. e project is co-funded by Holland High Tech, Top Sector HTSM, and the Dutch Research Council (NWO), with a public-private partnership grant for research and innovation. is ready to be printed with a chip pattern, through the so-called lithography process, the silicon is placed by a robot on the magnetically-levitated stage, which moves very precisely under extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light – exposing only speci c parts of the silicon to the light to print patterns. “ e exactness and speed of this movement are critical for productivity, but fast motions easily trigger mechanical vibrations that destroy the accuracy of the lithography process,” describes Matthijs Langelaar, associate professor of computational engineering at TU Delft. “Making the chuck sti er isn’t an easy remedy, since adding more mass results in higher forces as well.”

Typically, to solve this issue and limit the vibrations in wafer stages operating at high speed, it would take teams of engineers conducting dynamic optimization analysis – a real-time test and evaluation process of the mechanical design – to determine how best to control the movements for optimum precision. e Imsys-3D collaboration, however, is looking to automate and improve the procedure. “Currently, this is an iterative process where the mechanical designers create a design and pass it along to dynamics engineers for analysis. en the system would move to a control engineer to determine what kind of control bandwidth

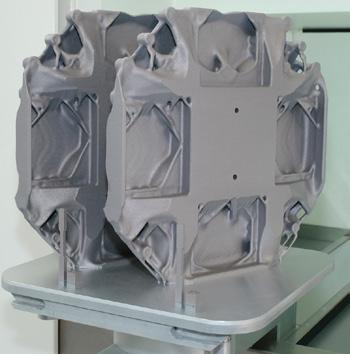

Credit: Imsys-3D

Back view of two printed chucks as produced by the Metalfab1 of Additive Industries. After separation from the build plate and post-processing of the magnet interfaces, the chuck is ready for use in a motion system.

we can get out of the machine,” describes Dick Laro, system architect at MI-Partners. “Several years ago, we started looking into how to make this more e cient and we set out to combine these three separate steps and integrate them into one, as part of a new integrated optimization process.”

“ is integrated way of working can reduce the lead time of a stage design from several weeks to a single day, while also providing superior performance,” adds Delissen.

Topology optimization

After years of planning, research and development, the collaborators were getting close to their goals, at least in simulation. en, two years ago, the coalition was joined by Eindhoven’s Additive Industries, which brought its state-of-the-art 3D- printing capabilities using metal-based additive manufacturing (AM) technology. As a unit, the consortium focused its design work on to-

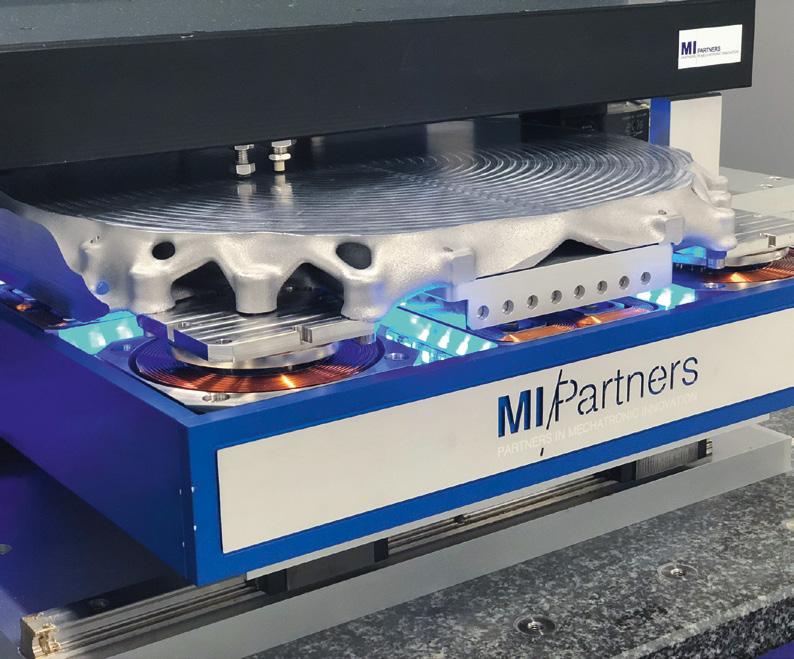

Credit: MI-Partners

pology optimization, aka generative design, which takes a 3D model and analyzes how to whittle away layers of excess material to achieve ultra-e cient designs, while still tting the size, weight and functional requirements of the customer.

In designing their rst demonstrator, collaborators adhered to a strict set of parameters from one of their industrial partners. e new chuck needed to have a speci c shape, a weight pro le of roughly 8 kilograms and needed to measure 400 by 400 by 50 mm – a very large volume in the metal 3D-printing world. “ is is a real bene t of our system and metal AM technology, the complete freedom of shape and design – allowing the algorithm to optimize in a broader space,” highlights Harry Kleijnen, key account manager at Additive Industries. “We’ve created printed structures that you simply cannot create with any other technology available today. is is a major contributor to the uniqueness of this project and the promise of the future.”

“By utilizing these methodologies for topology optimization, we could fully exploit the exibility o ered by additive manufacturing. As Harry described, it gives you a lot

High tech highlights

A series of public-private success stories by Bits&Chips

The fi nal product in action: the printed optimized stage, magnetically levitated in its setup at MI-Partners.

of freedom, which you simply don’t have in conventional machining,” adds Laro. “By using this, we’ve been able to markedly improve the performance of the stage, which is important because it would be next to impossible for human minds to just develop that structure, which is now synthesized through the algorithm.”

First time right

While many development projects take years of trial and error and analysis, the Imsys-3D project team has made big strides in progress over a relatively short time. ough the collaborators have run into several challenges, ranging from changing dimensions of the stage requirements to the pure computational issues caused by the limitations of today’s technology, the group has already rea lized success. In fact, with all parties giving input throughout the optimization stage of the chuck, the nal design was sent to Additive Industries and prepared for the rst trial print. “Going into this last phase of the design, we reviewed the plans, allowing our team to bring in the speci c AM constraints, like maximum angulation of surfaces, to be integrated into the algorithm, then it was ready to go,” recalls Kleijnen. “ e design was perfectly suited to print. We printed two parts, which took roughly 10 days total – 5 days per part. We could achieve this in half the time, but we opted to play it safe for the initial print. In the end, the newly printed chuck was a total success from the very rst time, which is a big step forward.”

Now, the aluminum-alloy wafer stage, weighing in at 8.5 kilos before processing, is heading to MI-Partners to be integrated into the machine and tested. Group expectations are that this newly printed chuck can o er twice the performance as its predecessors while limiting vibrations and ensuring precision and accuracy. “Going forward, our goal is to have a completely automated design process within a year,” expresses Langelaar. “MI-Partners will be working to fully integrate the chuck with the motion controllers to show the viability and potential gains to industrial stakeholders. In the end, we think this will o er unparalleled e ciency for those making the chips, which means cutting-edge technology can become more a ordable to end-users and consumers.”