DRIPA AND MINING THE STAKES OF B.C. MINERAL STAKING

POWERING UP FROM DIESEL TO CLEAN ENERGY

DRIPA AND MINING THE STAKES OF B.C. MINERAL STAKING

POWERING UP FROM DIESEL TO CLEAN ENERGY

We believe that learning about diverse Indigenous cultures is one way we can foster long-lasting relationships with Indigenous Peoples and communities .

In honour of National Indigenous Histor y Month , we’re sharing new experiences to explore and learn about the First Nation communities we ser ve. We’d like to thank our Indigenous par tners for allowing us to share in their celebrations and culture throughout the year. These give us authentic op por tunities to learn and grow.

Learn about our community ties at for tisbc .com/indigenousrelations .

Mákook pi Sélim acknowledges the unceded and ancestral homelands of the hƏ ń q Əmi ńƏm and Sk w x wú7 mesh speaking peoples, the xwm Ə økw Ə ý Ə m (Musqueam), Sk w x wú7 mesh (Squamish) and selilweta† (Tsleil-Waututh) nations on which this magazine was co-created. The Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations have been stewards of their traditional homelands since time immemorial.

PRESIDENT: Alvin Brouwer

PUBLISHER AND EXECUTIVE

EDITOR, BIV; VICE- PRESIDENT, GLACIER MEDIA: Kirk LaPointe

EDITOR- IN - CHIEF: Hayley Woodin

EDITOR: Chastity Davis-Alphonse

DESIGN: Petra Kaksonen

CONTRIBUTORS: Merle Alexander, Chief Joe Alphonse, Natalie Clark, Chastity Davis-Alphonse, Keogh Dooley, Shain Jackson, Dale McCreery, Mia Pena, David Douglas Robertson, Kim van der Woerd, Giana Viel, So a Vitalis, Denise Williams

RESEARCHERS: Anna Liczmanska, Albert van Santvoort

SALES MANAGERS: Michelle Bhatti, Marianne LaRochelle

ADVERTISING

SALES: Ruth Gallinger, Susan Hutchinson, Blair Johnston, Ivana Jukic, Manny Kang

Mákook pi Sélim is published by BIV Magazines, a division of BIV Media Group, 303 Fifth Avenue West, Vancouver, B.C. V5Y 1J6, 604- 688 -2398, fax 604- 688 -1963, biv.com

COLUMN

A Chinook Jargon language lesson

Copyright 2023 Business in Vancouver Magazines. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or incorporated into any information retrieval system without permission of BIV Magazines. The publishers are not responsible in whole or in part for any errors or omissions in this publication.

ISSN 1205-5662

Publications Mail Agreement No.: 40069240.

DENISE WILLIAMS - 19

8

8 FROM DIESEL TO CLEAN ENERGY

Empowering remote communities

13 DRIPA AND MINING IN B.C.

The path forward for reconciliation

18 BIV LIST

The biggest Indigenous businesses in B.C.

20 INDIGENOUS HEALTH

Workplace wellness and reconciliation

Registration No.: 8876. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Circulation Department: 303 Fifth Avenue West, Vancouver, B.C. V5Y 1J6 Email: subscribe@biv.com

Cover photo: Yoho National Park in British Columbia | Feng Wei Photography/ Moment/Getty Images

Welcome to BIV ’s fifth issue of Mákook pi Sélim (which translates to “buying and selling” Chinook Jargon). We are pleased to bring you another in -

formative issue featuring 100 per cent Indigenous-written articles and columns that cover a broad spectrum of themes and current events. It continues to be important in this time and space to have dedicated places for Indigenous Peoples to share their perspectives and knowledge on current events in our province and country. I feel very honoured to be editor of one of the only dedicated print spaces in the country that uplifts Indigenous voices in a meaningful way.

For decades. Indigenous Peoples have been at the forefront of the Truth and

Reconciliation movement in Canada. Multi-level transformative change has happened over this time as a result of Indigenous Peoples’ leadership in this country. From changes to Canada’s constitution, to preservation of some of the most beautiful landscapes in the world, to multimillion-dollar economic development projects, as well as grassroots movements that address the generations of genocide that have been inflicted on Indigenous Peoples by the State. Similarly, Indigenous leaders advocated for a national day to celebrate the rich and diverse cultures of Indigenous Peoples across Turtle Island. In 1995, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended that there be a National First Peoples Day established.

As a result of Indigenous leadership and this specific recommendation, in 1996, the governor general of Canada proclaimed the first National Aboriginal Day. In partnership with Indigenous leaders, June 21 was chosen as the day to observe and celebrate Indigenous cultures. This day was chosen because summer solstice is an

important cultural time for many Indigenous Peoples. In 2018, the day was renamed National Indigenous Peoples Day.

Since this national day was established, there have been celebrations held across Turtle Island and it is a time to learn about and participate in events that share and uplift Indigenous Peoples cultures and contributions. I would encourage you to commit to participating in local events and, if accessible to you, to look for opportunities to support these events through sponsorships that lead to long-term partnerships. Our publication this June is in honour and observance of National Indigenous Peoples Day – to add our voices and insight to the many ways to celebrate the First Peoples of this land.

Happy National Indigenous Peoples Day!

Chastity Davis-AlphonseTla’amin Nation and Tsilhqot’in Nation

Editor, Mákook pi Sélim chastitydavis.com

Editor, Mákook pi Sélim chastitydavis.com

A powerful online learning platform that centres the wisdom, traditional knowledge, worldviews, and lived experiences of the original Matriarchs of the lands often called Canada.

FOR A TRULY TRANSFORMATIONAL EXPERIENCE VISIT DEYEN.CA

BY BRIDGET GEORGE PHOTO CREDIT: GRANT FAINT/THE IMAGE BANK/GETTY IMAGES

DALE MCCREERY AND DAVID DOUGLAS ROBERTSON

PHOTO CREDIT: GRANT FAINT/THE IMAGE BANK/GETTY IMAGES

DALE MCCREERY AND DAVID DOUGLAS ROBERTSON

How does an Indigenous-based B.C. business language come up with an expression as funny-sounding as Halo jawbone? And why does it even have anything to with commerce?

Chinook Jargon is what we’re talking about. You’ve heard of it, probably in connection with previous generations of Native people. The Jargon has a long story behind it of being used for negotiations.

■ We can think of its first employment in talking to European fur traders on the lower Columbia River.

■ Jargon was also the language of Métis households, with the constant bargaining that spouses are engaged in.

■ It was the medium for working out wages and the prices of goods in stores in the Pacific Northwest for decades.

■ And Chinook Jargon was absolutely central in British Columbian assertions of Aboriginal rights and land title getting expressed to the Crown. Any of those examples deserves a column of its own – but today, we want to spend a minute on how Chinook got used in shopping.

When you were buying something from a commercial establishment in this region, back in the day, cash was in short supply. Paper money, such as it existed, wasn’t trusted, and everyone regularly discounted it. Sounds weirdly modern, eh? We phased out the paper loonie, for similar reasons!

There was such a lack of cash money in those “frontier” days, it left a big mark on our Chinuk Wawa, as the language calls itself.

The Wawa word we use for a dime is bit , or the Indigenized way of pronouncing it – mit. Ever heard the sports cheer? “Two bits, four bits, six bits, a

dollar! All for Pattison, stand up and holler!” Or did you ever hear big city people insult “some two-bit town”? Yup, that word is Jargon for a dime.

Except, back in old times, it also meant 15 cents! There just weren’t enough small coins in circulation out here to meet the demand, smaller than quarters that is. So, depending on the transaction, your payment of $0.25 for an item cheaper than that might get you back a “long bit” ($0 15) or a “short bit” ($0.10). Often this depended on luck. Did the shopkeeper happen to have any nickels that day? Or would they be forced to give you credit? Oh no...

The shortage of cash was kind of a nightmare for B.C. capitalism. If there was one thing people out here disliked almost as much as a toothache, it was having to give somebody jawbone . That’s the northern-dialect Jargon word for “credit.”

(It comes from slang, like a bunch of other Jargon words. “Jawbone credit” in English was gotten by talking someone into letting you owe money.)

Oh, and halo, pronounced “hey-low” in Jargon, is the Haida Gwaii-sourced word for “no” and “none.”

So, a sign that some B.C. business owners were known to hang up was the word halo above the jaw from a horse’s skeleton.

The phrase halo jawbone was routinely spoken, too. It’s in the running for the most B.C. thing to say, ever. And it comes from our Indigenous business history.

Dale McCreery is a Michif born and raised in Hazelton, B.C. He became interested in Chinook (also spelled Chinuk) Wawa (or Jargon) during breaks from learning his own language. David Douglas Robertson, PhD, is a linguistic consultant in Indigenous languages. He publishes articles about Chinook Wawa at chinookjargon.com and teaches free online classes in B.C. Chinook Wawa.

IF THERE WAS ONE THING PEOPLE OUT HERE DISLIKED ALMOST AS MUCH AS A TOOTHACHE, IT WAS HAVING TO GIVE SOMEBODY JAWBONE. THAT’S THE NORTHERN-DIALECT JARGON WORD FOR “CREDIT”

CHASTITY DAVIS-ALPHONSE, TLA’AMIN & TSILHQOT’IN NATIONS

CHASTITY DAVIS-ALPHONSE, TLA’AMIN & TSILHQOT’IN NATIONS

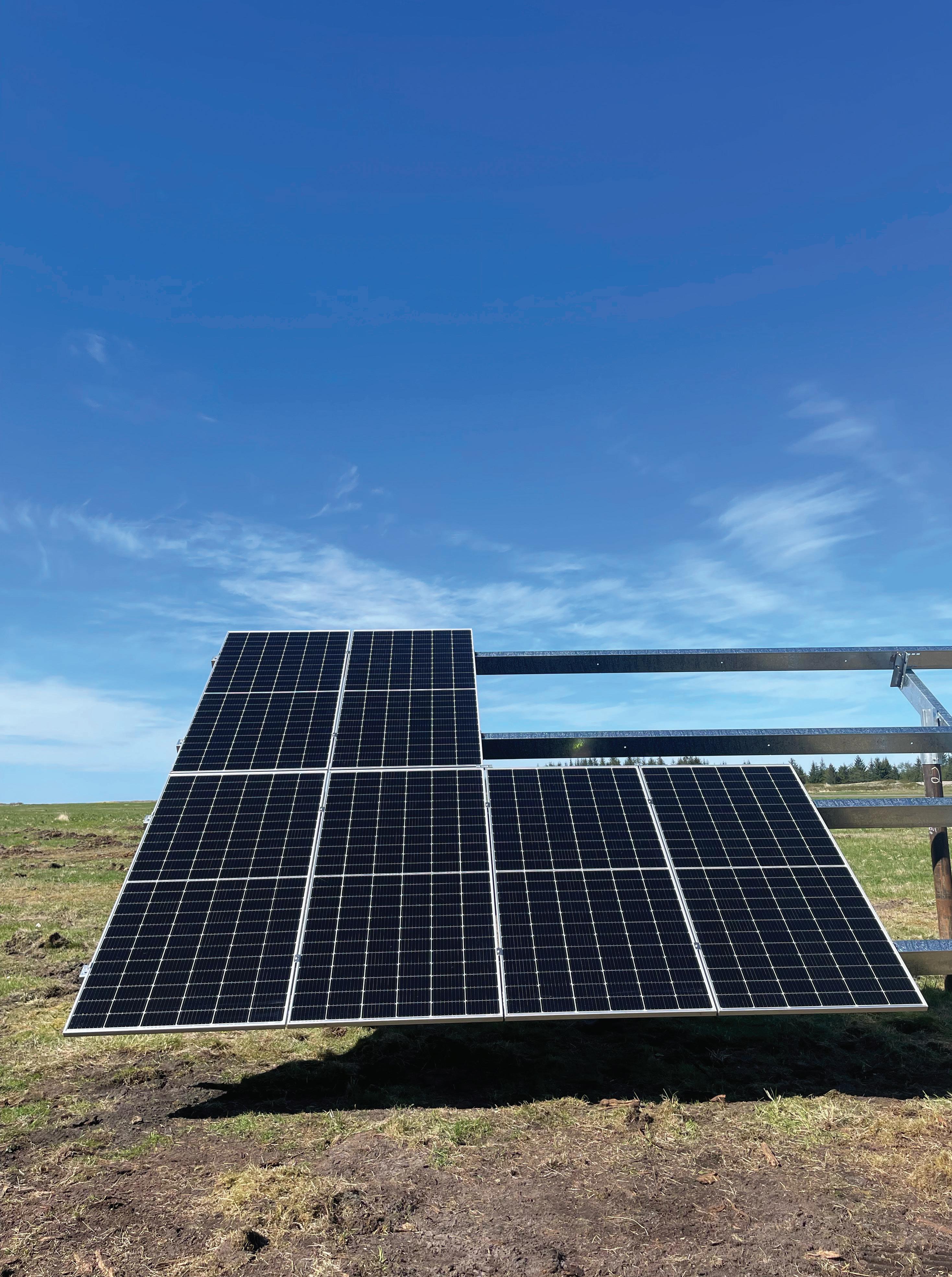

The majority of those 27 communities are Indigenous and have been leading advocates in the shift from a reliance on diesel as a source of power, to clean energy opportunities such as solar, wind, tidal and small-scale hydro dams.

Diesel generators are expensive, high carbon producers, and put a strain on overall health and wellness of peoples and lands. Clean energy utilizes the natural elements and energy of the lands such as the sun, wind, fire and water – sources that are more aligned with the Indigenous way of being, worldviews and values of being interconnected to nature, and living in harmony with traditional lands.

Despite broad recognition of the need to reduce carbon emissions, and support for decarbonization initiatives, a lot of this advocacy has fallen on deaf ears within government and the utilities.

Trent Moraes is the Deputy Chief of Skidegate Band Council on Haida Gwaii, and has been leading the development of a cleaner energy grid for over a decade. The council has successfully built a two-megawatt (MW) solar field and many other clean energy initiatives.

Moraes shared that Haida Gwaii has the largest consumption of diesel among all remote communities in British Columbia.

“We are bigger than the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Alberta combined with over 51.06 per cent of all B.C.’s

diesel generation in Haida Gwaii, which is 5 . 4 per cent of all of Canada’s diesel consumption.”

Moraes is not only leading a different energy path forward for Haida Gwaii, but has co-founded a clean energy group that represents all remote Indigenous communities (known as Non-Integrated Areas [NIA]) to advocate for decreased diesel reliance and support from provincial and federal governments, BC Hydro and the BC Utilities Commission for clean energy projects.

Despite diesel consumption being the largest opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Moraes says that “they are the last considered and this is crazy!”

He adds that “our voice hasn’t been considered until the adoption of UNDRIP,” referring to Indigenous voices and Bill 41 that was adopted by B.C. in 2019. “First Nations are now being required to be consulted with. Since UNDRIP, we are no longer an option.”

When asked what the barriers are for moving away from diesel reliance to clean energy, Moraes shares that “it’s BC Hydro and their red tape, and the BC Utilities Commission. The province must advocate and make legislative and regulatory changes to the process that will make way for Indigenous communities to lead clean energy projects in their community.”

Moraes offers some solutions to those barriers. More

There are more than 230 remote communities in Canada that are powered by microgrids, and 27 of them are in British Columbia.A two-megawatt solar eld is one of the Skidegate Band Council's clean energy initiatives • SUBMITTED

Indigenous people are needed inside BC Hydro to help the utility understand, relate to and connect with communities, ultimately leading to better relationships.

At BC Hydro and with the provincial and federal governments, Moraes says that there is support from top executives and ministers for Indigenous-led clean energy projects, but that it’s the bureaucracy that stalls initiatives and frustrates change.

Aligning executive and political will with bureaucratic and organizational operations would go a long way in making necessary changes, he says.

Leona Humchitt from Heiltsuk First Nation has also been leading the way for her nation with the creation of the Haítzaqv Community Energy Plan. Humchitt says that this plan was created “by the Heiltsuk for the Heiltsuk.” It incorporated a robust community engagement plan built from the more than 1,000 Heiltsuk voices that spoke about Heiltsuk history, language and culture.

“We incorporated our own language and words into the plan, and this creates ownership and buy in from the

community,” Humchitt says, adding that creating the Haítzaqv Community Energy Plan “was an amazing journey that helped us blossom and root ourselves in stronger jurisdiction.”

Similarly to Moraes, Humchitt speaks to the barriers that are present with Indigenous communities switching from diesel to clean energy. Humchitt also speaks to the lack of funding that is available from the federal and provincial governments. She says even though the federal government recently invested $300 million dollars for Indigenous-led clean energy projects, $ 70 million went to setting up a government-led administrative arm and the rest gets split up between the more than 600 First Nations across Canada, and won’t result in much investment to each nation.

Despite the multiple barriers, Humchitt and the Heiltsuk Nation are implementing many aspects of their clean energy plan and have completed retrofitting in over 90 per cent of the homes in the community with renewable energy and heat pumps. They have also conducted energy audits on 200 homes and solar feasibility studies for both residential and

commercial spaces, and are currently taking part in a renewable diesel pilot project.

Humchitt says that implementing the clean energy plan is to ensure that her nation is building “a better future for the little ones and the little ones to come.”

Moraes and Humchitt are leading some important work on behalf of their nations and there are many other First Nations that are leading similar and equally important work to move away from reliance on outdated diesel generation. If the government and utility companies made a meaningful commitment of resources to the leadership that remote Indigenous communities are showing regarding clean energy projects, our province and country would be moving in the right direction to reduce our collective carbon footprint, to align with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to realize Truth and Reconciliation.

Indigenous Nations know how to preserve and live in harmony with their lands – we’ve been doing it for thousands of years. British Columbia and Canada will only reach their full potential when Indigenous Peoples are able to step into theirs. Now is the time.

WE ARE BIGGER THAN THE YUKON, NORTHWEST TERRITORIES AND ALBERTA COMBINED WITH OVER 51 06 PER CENT OF ALL B.C.’S DIESEL GENERATION IN HAIDA GWAIITrent Moraes Deputy Chief, Skidegate Band Council

True leadership is required to address the climate crisis and to protect the world we share

CHIEF JOE ALPHONSEFirst Nations can often feel isolated and alone in our fight for title, rights and recognition. The United Nations offers a forum where Indigenous groups from all over the world can meet and realize that we aren’t alone on our paths to recognition. In April of this year, a Tsilhqot’in delegation, including myself, attended the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) in New York. The theme this year was “Indigenous Peoples, human health, planetary and territorial health and climate change: A rights-based approach.”

Sometimes you’re not sure whether you should continue to push for change or if the fight will get you nowhere. It is re-energizing to meet with Indigenous Peoples from around the world, who share the same struggles and aspirations as our people here in Canada. You know that not only should you fight – but you have an obligation to make sure Canada does better.

Some Indigenous groups at the UN are risking their lives to speak out against their treatment back home. It is important to meet with the nations there in order to have dialogue and see how we can support one another.

Canada is a global leader in setting the bar for human rights. However, one of Canada’s exports has been its policies and treatment of Indigenous Peoples. Canada must live up to its obligation to the rights of Indigenous Peoples. It is no secret that the health and well being indicators of Indigenous Peoples in Canada are on par with levels seen in developing countries. Nor that the voices of

Indigenous Peoples have been silenced since the earliest days of settlement.

The issues of the climate crisis become magnified tenfold when the lack of Indigenous voice combined with the impoverished conditions of our communities. Business has a role to play in the climate crisis to not only develop climate alternatives, but to advocate for the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) as a mechanism to give voice to Indigenous Knowledge and improve the lives of the fastest-growing population in Canada – First Nations. We arrived at this place – the health of our planet in crisis and the health of our people on equal footing – because of leaders focused on progress instead of protection. When you change the natural environment, there is no amount of science or technology that can replicate that. When you remove nature, you remove the connection that Indigenous Peoples have to it. For most settlers, it is hard to comprehend the idea of the entire formation of a people to be based on what the land, air and water provides. And furthermore, for an entire language system to be developed from the land. The environment – the lands at the state they are in, in this country, is screaming for its Indigenous voices to be incorporated and to bring nature back into a healthy balance. The global community of Indigenous Peoples understands this need. We know why we have to fight. We see the conflict between notions of progress and the dire impacts it is having on Indigenous cultures and the world we all inhabit. It may not be in my lifetime, but I hope that Canada and the business community may one day share in the need to listen and act upon the Indigenous voice.

CANADA IS A GLOBAL LEADER IN SETTING THE BAR FOR HUMAN RIGHTS. HOWEVER, ONE OF CANADA’S EXPORTS HAS BEEN ITS POLICIES AND TREATMENT OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

Is this a moment for meaningful, transformative change, or merely the pursuit of fool’s gold?

MERLE ALEXANDERB.C. mineral staking is like online gaming. With the click of a button, any would-be millionaire takes their chance to strike it rich.

The odds of success are extremely low, the wagers are typically made with other people’s credit and, seemingly, the house always wins.

The Crown is the house and greatest beneficiary, as they profit from highly taxed profit margins that ultimately exploit the gamer. The truth is, though, the Crown is dependent on the outcome and has itself become vested in gamers’ losses and successes.

The B.C. mining regime is akin to regulating an illegal activity (under the Criminal Code, gaming houses are illegal unless the Crown authorizes them). The illegal activity is the granting of rights to exploration and mining companies on First Nations title lands without their consent. The entire mining regime is based on the theft of First Nations subsurface minerals. It is deeply rooted in the racist and colonial doctrine of discovery

and terra nullus that we recently witnessed the Pope apologize for and reject.

So, what does this analogy have to do with B.C.’s Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA) and mineral tenure reform? Well, to be blunt, we need to start this process with Truth if we are to achieve Reconciliation. We cannot rebuild a Mineral Tenure Act or Mines Act (or any legislation) to be “consistent with UNDRIP” on illegal concepts of ownership. The Crown also must come clean with the fact that it has a vested interest in the continuation of the current regime. These are hard truths and so far, they are not accepted.

We are a crossroads on implementing UNDRIP in B.C. Beautiful political platitudes, deeply respectful land acknowledgements and good faith are being tested. The reform of B.C. mining law is the first truly land-based statutory regime to enter into the queue and it forces a convergence of conflicting interests. It is the epitome of fear and fearmongering where some will argue that transformative change will cause a

certain economic Armageddon.

The crossroads are apparent because the B.C. government is currently committed to reform the Mineral Tenure Act through the DRIPA Action Plan on the one hand. And, on the other hand, Crown counsel is making written and verbal legal submissions in the Gitxaaxla case before the B.C. Supreme Court that uphold the current regime. This undermines the spirit and intent of UNDRIP implementation and could destroy the fragile trust that is being rebuilt.

In the last few weeks, we could have literally created a split screen. On one screen, we see historical announcements of legacy investments in implementing UNDRIP, and the introduction of title affirmation legislation for the Haida Nation. On the other, attorney general legal counsel arguing that DRIPA is mostly aspirational, and that no duty to consult is required when awarding exploration interests in title lands.

You cannot rebuild trust with a forked tongue.

Reconciliation in B.C. is about accepting the legal pluralism of First Nations’ legal orders and jurisdiction alongside and

equally with Crown jurisdiction. Reconciliation achieves mutual consent and co-jurisdiction. Reconciliation will create a legal regime of certainty where exploration and mining companies have a clear path to approval or rejection of their projects.

We are in a difficult transition of reconciliation growing pains now. First Nations are saturated in Crown consultation referrals and industry engagement, and now must also implement this transformative legal reform. In mining, there are piles of exploration and mining-related referrals; environmental assessments; direct engagements with exploration and mining companies; direct negotiation on government-to-government agreements in developing consent-based agreements applicable to mining and Mineral Tenure Act reform. Those are a lot of parallel paths running simultaneously – and they are converging.

So how do we chart this path together without undermining our mutual interests? For me, it is simple. The B.C. government must embrace an empowered mandate to legal reform. A mandate that:

■Creates co-jurisdiction for First Nations and Crown;

■Repudiates colonial Crown constructs of discovery and terra nullus (you need to accept that this land remains subject to our Title);

■Embeds UNDRIP in the architecture of the exploration and mining regime;

■Creates and ensures legal participation of First Nations right-holders throughout legal reform (we cannot uplift First Nation legal orders and not have them at the table);

■Defines the roles of stakeholders, including the environmental non-governmental organizations, industry associations and Métis; and

■Transitions existing grandfathered approvals paired with a redress mechanism.

As a transition, there needs to be a clear timeframe that no further tenures or other exploration or mining approvals can or will occur without First Nations consent. We cannot continue in this patchwork of mere consultation that leaves vulnerable all permits. We cannot continue in a consultation framework that encourages First Nations to choose the last resort of litigation. We need to have the humility to accept that the status quo is not working, and that truth is foundational.

There is a mutual interest for all of us to see a thriving, environmentally sustainable prosperity within these Territories. We cannot allow fear-based bureaucrats and advisers to uphold law that is

based on original crimes. We cannot allow UNDRIP to become the fool’s gold in implementation. We can accept hard truths to make progress.

WE ARE A CROSSROADS ON IMPLEMENTING UNDRIP IN B.C. BEAUTIFUL POLITICAL PLATITUDES, DEEPLY RESPECTFUL LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND GOOD FAITH ARE BEING TESTEDMerle Alexander Principal, Miller Titerle +

Co

The model remembers Dr. Miyazaki, and centres Indigenous healing

There are times when we need to chart our own path. As you may be aware, the treatment of Indigenous folks in our medical system has been a hot topic over the past few years. For many decades, we as Indigenous people have been seeking quality health care without needing to worry about being subjected to inferior treatment, racist stereotypes and so on. If you are not familiar with these issues, please have a look at B.C.’s In Plain Sight report among other evidentiary writings. Thanks to light being shed on these topics, and the hard work of many wonderful people, things are slowly changing for the better. However, the tectonic shifts we require are still not on the horizon. As Indigenous people we have concluded that if we want substantive change, we must create the vision ourselves.

A few years ago, I was asked to create a large art piece for the st’at’imc people near Lillooet. It was a copper wall depicting their history, stories, laws and so on. I was given the honour of interviewing many Elders, cultural keepers and

historians, and one name kept popping up: Dr. Miyazaki. I dug deeper into this figure and found something remarkable. Miyazaki’s story starts during WWII when Canada was rounding up Japanese Canadians and placing them in internment (read concentration) camps. One of these camps was in st’at’imc territory near Lillooet. The Japanese here were treated horribly and abandoned by much of Canadian society. During this dark time, it was the st’at’imc that came to their aid, treating them like family, sharing what little they had and supporting the Japanese in whatever way they

AS INDIGENOUS PEOPLE WE HAVE CONCLUDED THAT IF WE WANT SUBSTANTIVE CHANGE, WE MUST CREATE THE VISION OURSELVES

could, sometimes risking their own freedom to do so. Instead of going home after the end of the war, when the camp closed, Dr. Miyazaki – picking up his medical practice

decided to do something extraordinary. In reciprocity for all the love and goodwill he was shown by the st’at’imc people, Dr. Miyazaki stayed behind and dedicated his life to serving the st’at’imc as their doctor. This included house calls and delivering babies. He was also known to advocate for members when they needed to go outside the community for treatment.

I understand that this one man’s dedication to this Nation led to definitively better health outcomes than those experienced by any of the surrounding Nations. Knowing this, it dawned on me: Every community needs a Miyazaki! 0 ur own doctor focused exclusively on us. Someone who can be part of our community, do house calls, build relationships and advocate for us when we are in hospital to make sure we are safe and treated with respect.

Since learning this story, we began imagining not only a doctor dedicated just to us, but a medical setting built just

for us. Instead of a cold clinical space full of potential threats, we imagined a warm, caring, cultural space where we’re surrounded by cedar, beautiful artwork and things that make us feel at home; a place where our own medicines can be used and ceremonies held, and where we will feel safe and welcome. Thanks to the guidance of the folks at the Lu’ma Clinic in Vancouver – who have already broken ground in this area – and numerous others, we have designed just that.

We would like to see such spaces dotted throughout B.C., and while each individual clinic will be named in the language and tradition of its local beneficiaries, informally we would like the greater project to be named after Dr. Miyazaki. This, so we can call upon this beautiful narrative of compassion, honour, love, and reciprocity to bring us all together. When we act as one, and for one another, we can overcome immense challenges and accomplish fantastic feats.

sectors

A re ection on leadership, stepping up and stepping away

DENISE WILLIAMSSometimes people would call me a “fearless leader” to compliment me. I never received it well. I would quietly take offence at the notion that I did any of it without fear. The emotional and physical pain of standing at podiums, speaking my truth in rooms where I was dismissed daily and navigating the tricky business of assembling a team I could trust was, at times, excruciating. For lots of leaders, the work of it all is like a gentle hike with some ups and downs but nothing unmanageable. Not me. I was on the final traverse of the hilly step, unsure if I’d survive the ascent or decent, oxygen thin, a misstep disastrous – and that would be just a Monday.

A year after leaving all forms of leadership to heal, travel and indulge myself in philosophical questions about what it all meant, I realized that it’s just bloody hard work to bring every element of your lived experience as a First Nations woman to work with you every day and have it sniffed out and picked through by packs of boards, governments, colleagues and mainstream industry, never knowing if they would approach with educated allyship, or with an intention to consume you to advance their own interests and survival.

It’s not advisable to approach those packs fearlessly – we don’t have that kind of privilege. It is, however, wise to be calm and do what First Nations leaders have been doing for generations. We can only trust our instincts and our knowing. Trust that we never truly walk alone, and do our best to make the most of the gifts we have and share them with as much love and generosity as possible – despite the threat.

That said, my life has kind of been one long existentially anxious process of trying to know who I am and what I’m meant to do here. I gave up long ago on arriving on an answer and have accepted that my job is to just learn how

to live a healthy life at this high frequency vibration of exuberant, spilly empathy and its compulsory aloneness. Luckily, when one is left alone with reckless empathy and desperate intellectual curiosity, too intense to ever allow for “a focus,” one can spend wonderful amounts of time observing how things work, what drives people and what’s truly behind all the façades and dynamics.

Being in this state of comfortable liminality can be an advantage when your work requires navigational skills that aren’t taught in schools or easily read in books. This is true of the work ahead of us navigating ongoing systemic racism, the work of reconciliation, the reimagining and the redesigning of ‘Canada.’

For those reasons, although I don’t know what it all means for me personally, I’m thrilled that I'm without the burden of thinking I know how or what’s next. This state of liminality is allowing me to live into the moment, meet the moment and make decisions from a new place within me that is far wiser than when I had a title. I’m finding it freeing to live a life away from data, reports and experts for now. It feels like step one of undoing some of that fear.

You know, maybe that’s part of the reason I truly loved the work of the First Nations Technology Council in those early days. It allowed me to be an unrestrained philosopher on the future and imaginings of Indigenous leadership in an undetermined and not-yet-designed world – work that is by definition expansive, unknown, complicated. Perhaps it met me where I was at the moment and we understood each other, two Rubik’s cubes spinning around, excited by the moments it felt like something, anything, might line up and make sense.

There’s something extraordinary about stepping away, and stepping out of playing by the rules of someone else’s game. That’s all I’m saying. In the words of the great ‘90s philosopher Eddie Vedder, “I knew all the rules, but the rules do not know me, guaranteed.”

Denise Williams is a member of the Cowichan Tribes and former CEO of the First Nations Technology Council.

The 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission released 94 calls to action to redress the colonial legacy of residential schools.

Call to Action No. 19 focuses on gaps in health outcomes and health services for Indigenous Peoples; Call to Action No. 23 focuses on recruiting and retaining Indigenous Peoples in health-care fields, and providing cultural competence training for all healthcare professionals; and Call to Action No. 92 calls on corporate Canada to have equitable economic development opportunities for Indigenous Peoples, and equitable access to jobs, training and education opportunities in the corporate sector.

In 2020, data demonstrates that Indigenous Peoples continue to be underemployed and paid less than non-Indigenous people in Canada. Furthermore, employed Indigenous people have differential occupational health outcomes due to high levels of psychosocial and environmental hazards.

Occupational health considers categories that can create hazards for people, including biological, chemical, physical, biomechanical and psychosocial hazards. Social determinants of health (for example, income and social protection, working life conditions, social inclusion and non-discrimination or structural conflict) can further influence health outcomes that, in turn, influence the health of Indigenous people in the workplace.

Occupational health and social determinants of health provide an intersection of factors that can define health.

Furthermore, conceptualizing health through an Indigenous lens

means focusing on the interconnectivity of the physical, mental, spiritual and emotional aspects of being. Holistic health involves the balance and harmony of the four states of being through a mind-body-spirit connection.

With regard to the nature of employment, 23 per cent of Indigenous people who are employed in Canada work in the goods-producing sector, according to The Lancet Global Health journal. Another 14 4 per cent work in health care and social assistance, 10 2 per cent in public administration and 10.8 per cent in

construction. Indigenous people are underrepresented in managerial and technical services ( 3 4 per cent).

The report – which examined seven databases and 31 studies as

Shifting our mindset of how work needs to be can encourage reconcilitation, Indigenous worker retention and a holistic model of workplace wellnessNatiea Vinson is CEO of the First Nations Technology Council • SUBMITTED

CREECON.CA

Cree-Con’s skilled members are taking the Lower mainland to the Kootenay Boundar y Region to new levels for your one stop commercial concrete site works contractor.

part of a review of work and health issues encountered by Indigenous workers – found that, in general, being employed has been found to be a protective factor for substance misuse and gambling, as well as mental health for Indigenous people.

However, given the nature of employment held by Indigenous people, and their occupation of lower hierarchical levels in the workplace, evidence suggests Indigenous people are at greater risk of occupational hazards that can compromise their health.

Furthermore, Indigenous workers continue to face high levels of workplace racism, harassment and bias. Additional social determinants of health – such as low socioeconomic status for the worker and their family, higher rates of unemployment, lack of access to education, gender discrimination and ageism – further compound negative health outcomes.

These cumulative challenges can affect physical and emotional health and, consequently, their success in the workplace. For example, the experience of racism compromising emotional health has direct implications on punctuality, sick leave, stress leaves and overall retention, according to a 2019 report from the Conference Board of Canada titled Working Together: Indigenous Recruitment and Retention in Remote Canada

According to Dr. Brittany Bingham, director of Indigenous research at Vancouver Coastal Health and the inaugural director of Indigenous research at the Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity, Indigenous people “are still living out the historical contexts.”

“For example, Indigenous people go to more funerals, dealing with different challenges that others aren’t dealing with on a regular basis,” she said.

Workplace health and equity must ensure that people are treated fairly, and should entail cultural safety best practices – respectful engagements, for example, and addressing power imbalances.

As stated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, (UNDRIP) “Indigenous individuals have the right not to be subjected to any discriminatory conditions of labour and, inter alia, employment or salary.”

Supporting a holistically healthy Indigenous workforce is essential for strong businesses and industries, and is a central tool for health equity, justice and reconciliation.

Natiea Vinson, CEO of the First Nations Technology Council, encourages us to view holistic well-being in the technology sector, where Indigenous people are notably underrepresented.

“In western society, …. we look at mental and physical health as different parts. We can look at the medicine wheel to integrate those points.… We have to think about what is serving us as communities, whether Indigenous or not,” she said.

“Our lives are intertwined now,” she said. “[We can] use the teachings of the Medicine wheel to integrate beliefs of health in a wholistic way.”

Examples of ways to promote health for Indigenous people in the workplace include:

■building a genuine understanding of Canada’s history and impact on health and well-being for Indigenous Peoples;

■build strategic, effective and meaningful inclusion practices so that

Indigenous Peoples feel welcome, valued and understood;

■ensure cultural competency and humility training to reduce racism and discrimination;

■decolonize human resource practices to accommodate Indigenous Peoples to participate in familial and traditional activities (such as ceremony, hunting and fishing, family health and wellness needs);

■create career pathways for Indigenous Peoples to be in positions of leadership – pathways including mentorship and coaching; and

■continue to reflect on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action and on UNDRIP to be a part of good social change “You need to make different support for Indigenous employees because of this ongoing history that continues to shape Indigenous Peoples’ lives,” said Bingham.

“We need to shift the colonial mindset on how work needs to be. It means we need to decolonize what we see as wellness in the workplace and consider equity-informed wellness.… We must create systems of support that support wellness while doing work and while life happens.”

A project that teaches, heals and reclaims a sense of identity and connection to land

In our current colonial context, many Indigenous girls have been impacted by the toxic drug crisis, government care, intergenerational trauma and ongoing state violence against Indigenous children and youth. This state violence includes the problematic and disturbing narrative of Indigenous young women and girls as being at risk, or vulnerable. To offer a counter-narrative, supported Indigenous Girls' Groups are reinstating Indigenous ways of healing and wellness, training future leaders and providing a culturally safe space for sharing and growing.

By reclaiming this intergenerational gathering, we celebrate, support, hold up and foster young women, and non-binary youth in Secwepemc ways of being and wellness. The opportunity is provided to be mentored by Aunties and Elders in a culturally relevant and safe way, to engage in re-learning traditional practices, medicine making, land-based healing, and to strengthen the Secwepemc language, connections to the land, and foster belonging. These activities promote leadership and belonging to an ongoing intergenerational group, which provides opportunities for a young woman and gender-diverse youth to learn about and value their gifts.

The Tsutswey’e (butterfly) Grrlz' Group and land-based camp are rooted in a First Nations holistic, or gender-based intersectional approach that attends to many intersecting factors including age, gender, sexuality and a commitment to activism and Secwepemc sovereignty. The group is also grounded in the values and ethics of the Secwépemc people. These values include: Relationship: Kweseltnews (we are all family); Individual strength and responsibility: Knucwetsut (take care of yourself); Knowing your gifts: Etsxe; Sharing: Knucwentwe’cw; Humility: Qweqestin; Renewal: Mellelc.

Through the Tsutswey’e Group and the land-based camp, storytelling and art making, alongside ceremony, are multi-dimensional and interconnected. They form a larger narrative and shared meaning that not only bear witness to the realities of ongoing colonialism, but also place love, resistance and activism of Indigenous Peoples at the core.

The Tsutswey’e Group is facilitated by author Natalie Clark and happens weekly with guests like Elder/Knowledge keeper Minnie Kenoras, big sister helpers like Mia Pena and Seren Clark, who attended when they were younger, and guests including Aunties, Elders and Knowledge

Keepers. This supports the Neskonlith community vision for teaching young ones traditional ways and skills for living on the land: Birch bark basket making, hunting, berry picking, identifying and foraging for medicines, pine needle basketry and other Secwépemc seasonal activities. These cultural activities are integral for future generations to learn and re-learn. They are linked to healing, belonging, identity and esteem through the process of cultural remembering and renewal.

The weekly group centres Indigenous girls and non-binary youth in their community and culture, enhances wellness, fosters healthy and safe relationships and strengthens community connections and loving kinship. At their core, groups like this are examples of transformative models of healing and justice through healthy relationships with self, others and communities, especially with adult women – Aunties. They are examples of what Mississauga Nishnaabeg activist and scholar Leanne Simpson calls spaces in which an active presence is created through acts of ceremony, art making, singing, dancing, beading and by simply being on the land. Our work is to dream and “to do that dreaming” as Two-Spirit scholar and poet BillyRay Belcourt visions for us “in the name of a different revolution.”

The Tsutswey’e Group and the land-based camp are examples of Indigenous girls “(re)mapping” and (re)animating the lands with their movements, “spatial sovereignty,” ceremony and laughter, according to Mishuana Goeman, author of Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations. Youth are engaged in theorizing the lived sensations and embodiment of joy, of giggles, sitting around a fire together, storytelling and story listening, medicine picking and jumping into water together. Through everyday acts of loving and (re)matriation, we are imagining and creating a future for our children – one that exists beyond traditionalist and heteronormative patriarchal ideas of relationship to land and family.

This work offers hope for Secwépemc youth to once again be seen for their gifts, and for the statement “Let’s go pick berries” to be answered again and again with “Yes.” Cu7 me7 q’wele’wu-kt (Come on, let's go berry-picking).

Natalie Clark is a professor and co-chair of Thompson Rivers University’s School of Social Work and Human Service, and facilitator of the the Tsutswey’e Group. Mia Pena attended the group when she was younger and participates as a Big Sister.

BY RECLAIMING THIS INTERGENERATIONAL GATHERING, WE CELEBRATE, SUPPORT, HOLD UP AND FOSTER YOUNG WOMENIndigenous women are the heart of our communities. They’re our teachers, ceremonial leaders, interpreters, healers and caretakers of our children. They are also more likely to go missing, be murdered, assaulted and overlooked. As established by the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Indigenous women are 12 times more likely to be murdered or go missing than any other woman in Canada.

Additionally, the overwhelmingly colonial justice system that exists today – a system I’ve seen first-hand – further perpetuates negative impacts on lives of Indigenous Peoples.

It’s a vicious cycle that needs to end, and, as outlined in the 231 Calls for Justice , governments, businesses and organisations are responsible for meaningfully redressing historical and ongoing inequities and supporting Indigenous women to achieve their full pwotential.

There’s real power in giving people access to life-changing resources. Having dedicated my life to supporting Indigenous Peoples and promoting justice and decolonization, I have seen how culturally appropriate programs can move marginalised people into safer environments.

In 2021, for example, TELUS launched the Mobility for Good for Indigenous Women at Risk program, partnering with Indigenous organisations, including the Native Courtworker and Counselling Association of British Columbia (NCCABC), to provide smartphones and plans to Indigenous women at risk of or experiencing violence.

The program gives women a critical lifeline to timely emergency services, reliable access to virtual healthcare and wellness resources, and the ability to stay connected to their support networks. The effects of colonial practices and systems – such as Residential Schools and the ’60s Scoop – continue to be felt by Indigenous People today.

Women we help at NCCABC are fleeing violent situations, coming to us with no ID or money. They’re surviving on the streets while waiting for a space at a transition home. Some Indigenous women who live in isolated communities rely on hitchhiking for transport.

That’s why ensuring Indigenous women stay connected to someone they trust is critical.

To date, the Mobility for Good program has supported more than 1200 Indigenous women and their families. Our TELUS partner has been receptive to feedback provided by the NCCABC, improving the

program based on our recommendations, while addressing a number of the Calls for Justice.

As we did on Red Dress Day, we must continue to recognize and honour the lives of the missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people, and acknowledge the pain and trauma to our families and communities.

We must continue to decolonize our systems and support Indigenous Peoples in their journey toward healing and personal sovereignty, while reconnecting with their culture and communities.

We are seeing Indigenous matriarchs rise up. They are standing in their truths, reclaiming their identities and culture, and making impactful changes across our communities.

There is a role for everyone to support this powerful journey. The recommendations within the 231 Calls for Justice state this best: “ Individuals, institutions and governments can all play a part; we encourage you to understand and, most importantly, to act on yours.”

By Kim Rumley, the Acting Director of Court Services at the Native Courtworker and Counselling Association of British Columbia