5 minute read

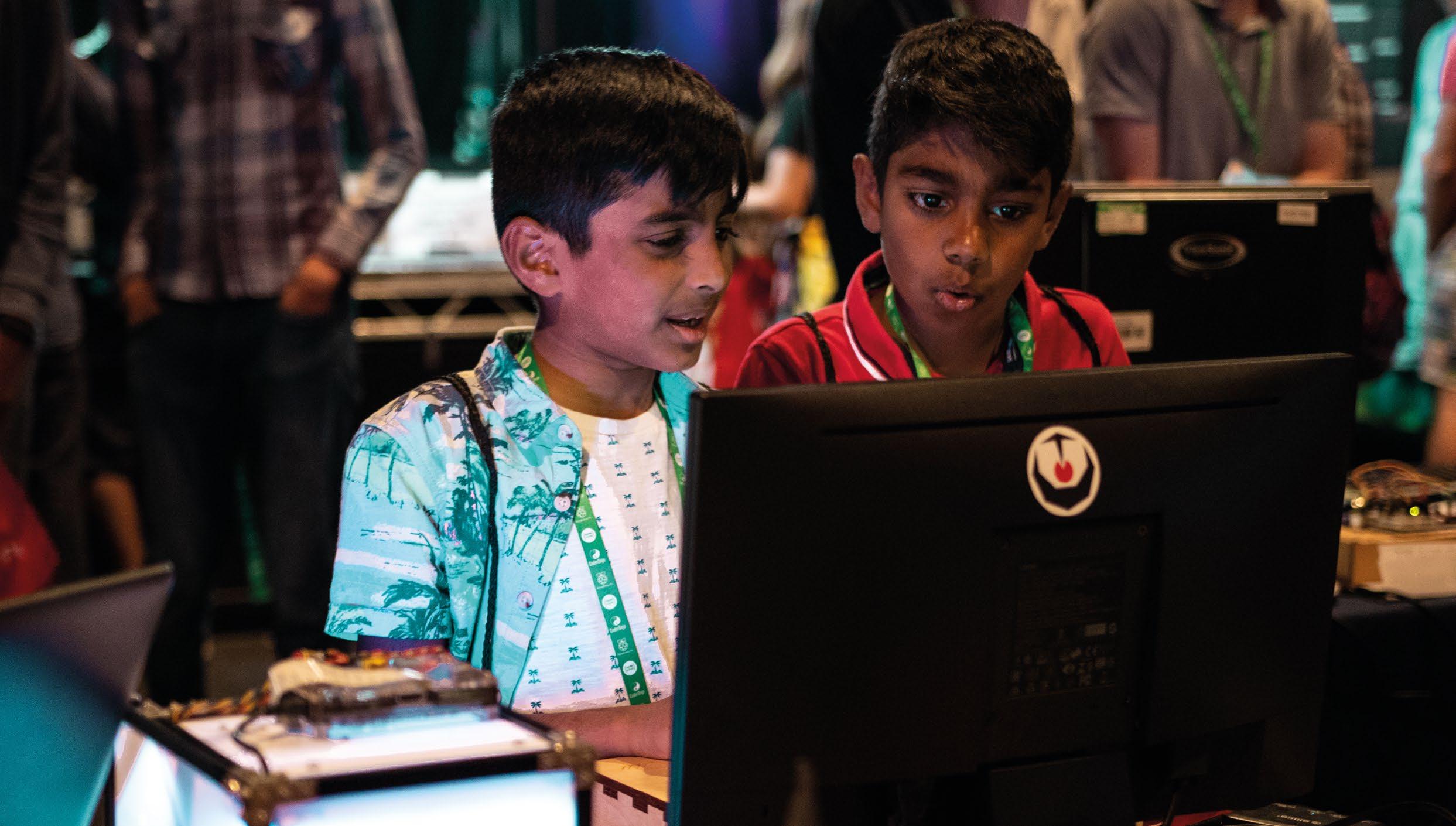

LEARNING THROUGH MAKING

Credit: locrifa/stock.adobe.com

Making is so much more than just a tool for engagement; its power can be harnessed for a very different way of learning and understanding the world

Advertisement

It’s pretty clear, if you know young people, that making is something that’s going to engage them. Active lessons always get the popular vote from classes, especially if they let students make choices about what they work on. The sense of achievement you get from making something and sharing it with others or taking it home is pretty motivating too. There are always a few who would rather have a theory lesson, but the engagement you get from making is usually a powerful motivator. It’s hugely important to get people engaged with learning in order for it to be successful, but learning is more complicated than simply paying attention to something. Seeing learning through making only as a way to engage people would be missing something much deeper. For proponents of constructionism, it’s also about how making interacts with the way we develop understanding.

From concrete to abstract

The culture of education in the West can often be very focused on the cognitive — the abstract thinking that can be clearly defined in learning objectives, exams, and books. It tends to think of formal education as the process of coming to understand abstract ideas, with abstract ideas being the most important level of understanding that can then be applied to our everyday lives. Young children usually start learning about numbers through physically playing with concrete objects such as blocks, counters, and toys, but the aim is for them to move on to being able to discuss and manipulate numbers as abstract ideas. Dealing with concepts on a totally abstract level is hard, and children often have to return to these concrete methods to support their understanding. It takes time before children can add and subtract without the convenient aid of fingers to count on; even when this is mastered, they often return to counters when learning about the more complex concept of division. This trajectory from understanding concepts in concrete, real-life terms towards being able to explore them in the abstract is explored well in the work of Jean Piaget, almost universally taught in teacher education courses across the Western world.

Affective learning

While we see the cognitive side of learning as key to understanding, we tend to see the affective, or experiential and feelings-based, side as useful for making learning engaging and memorable, but not as a fundamental part of it. Computer scientist and pioneer of the constructionist movement Seymour Papert saw it differently. In his seminal text Mindstorms, he vividly relates the affective experience of playing with cogs and gears as a child, and how he came to an understanding that machines could be both very structured and creative ways of interacting with the world.

Papert writes about changing his world view not only in terms of gaining knowledge, but in terms of gaining a new relationship with knowledge. Manipulating and exploring the concrete objects of gears allowed him to develop an affective understanding of how machines work, and realise that these complex constructions are knowable and understandable. Mark Surman, the executive director of the Mozilla Foundation, describes this memorably as seeing the ‘Lego lines’ in the world; the visible joins that help you understand that something was made by a person, and that with the right learning, that person could be you.

Learning as becoming

Such a change in understanding is quite a shift from the way educators are often encouraged to see learning; it’s a different metaphor for the process. Much of the time, our language about learning is based on what Professor Anna Sfard calls the ‘learning as acquisition’ metaphor, in which learning is seen as discrete blocks of content that can be gradually acquired. There are other metaphors; when exploring

the potential of learning through making, it helps to think about the ‘learning as becoming’ metaphor, the idea that we learn in order to explore and develop who we are as a person, and the way we see our identity fitting in to the world.

New tools for learning

Much of this could be an argument for learning through experience, but for Papert it was using computers that was incredibly powerful. Why? Computers allow us to manipulate abstract concepts in a way we simply can’t in the physical world. Logo may seem like primitive software to us in 2021, but Papert saw its potential to allow children to actively manipulate concepts such as angles and geometry. This made abstract concepts accessible for children to manipulate and understand by feel, much as sand and water trays in the early years allows children to explore their understanding of basic physics. We expect children to move on from this playful, exploratory approach to learning as they get older, but perhaps this is only because we lack the tools to make more sophisticated concepts concrete and accessible to them to manipulate. The power of computers for learning is described in Papert’s writing not as being a way to deliver content to children, but as a tool they can use to explore and manipulate previously abstract concepts in a concrete way.

Harnessing the tools

Making is often a fun and engaging way to learn, yet its power can go beyond engagement and towards a very different way of learning and understanding the world. It takes a shift in how we think about learning and in the way we encourage young people to use computers to understand the world. These days, we certainly have more powerful and sophisticated tools accessible to young learners; perhaps the biggest challenge is understanding how they can be used not only to engage, but to learn in new ways that are both effective and affective.