RESEARCH

Credit: locrifa/stock.adobe.com

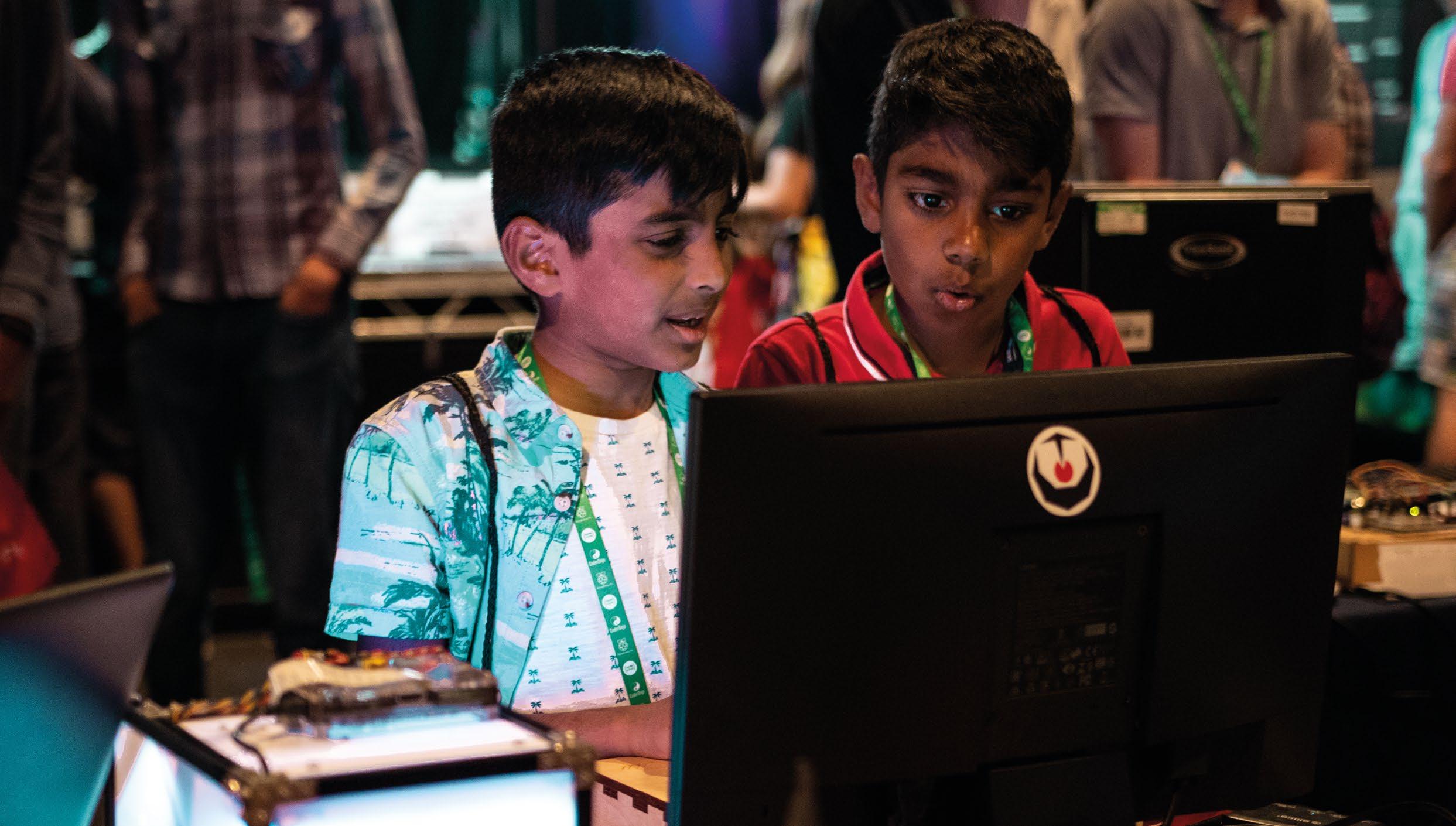

LEARNING THROUGH MAKING Making is so much more than just a tool for engagement; its power can be harnessed for a very different way of learning and understanding the world

t’s pretty clear, if you know young people, that making is something that’s going to engage them. Active lessons always get the popular vote from classes, especially if they let students make choices about what they work on. The sense of achievement you get from making something and sharing it with others or taking it home is pretty motivating too. There are always a few who would rather have a theory lesson, but the engagement you get from making is usually a powerful motivator. It’s hugely important to get people engaged with learning in order for it to be successful, but learning is more complicated than simply paying attention to something. Seeing learning through making only as a way to engage people would be missing something much deeper. For proponents of constructionism, it’s also about how making interacts with the way we develop understanding.

I

36

The Big Book of Computing Pedagogy

From concrete to abstract

The culture of education in the West can often be very focused on the cognitive — the abstract thinking that can be clearly defined in learning objectives, exams, and books. It tends to think of formal education as the process of coming to understand abstract ideas, with abstract ideas being the most important level of understanding that can then be applied to our everyday lives. Young children usually start learning about numbers through physically playing with concrete objects such as blocks, counters, and toys, but the aim is for them to move on to being able to discuss and manipulate numbers as abstract ideas. Dealing with concepts on a totally abstract level is hard, and children often have to return to these concrete methods to support their understanding. It takes time before children can add and subtract without the convenient aid

of fingers to count on; even when this is mastered, they often return to counters when learning about the more complex concept of division. This trajectory from understanding concepts in concrete, real-life terms towards being able to explore them in the abstract is explored well in the work of Jean Piaget, almost universally taught in teacher education courses across the Western world.

Credit: Anita Ponne/stock.adobe.com