JOURNAL BONEFISH&TARPON

Dr. Aaron Adams, Monte Burke, Sarah Cart, Bill Horn, Jim McDuffie, Carl Navarre, T. Edward Nickens

Publishers: Carl Navarre, Jim McDuffie

Editor: Nick Roberts

Editorial Assistant: Miranda Wolfe

Layout and Design: Scott Morrison, Morrison Creative Company

Contributors

Michael Adno

Monte Burke

Alexandra Marvar

Chester Moore

T. Edward Nickens

Flip Pallot

Chris Santella

Miranda Wolfe

Photography

Cover: Nick Shirghio

Dr. Aaron Adams

Brian Barrera

Tom Cawthon

Sergio Diaz

Greg Dini

Pat Ford

Natasha Gilbert

Warren Graham

Kelly Groce

Justin Lewis

Jess McGlothlin

Marc Montocchio

Chester Moore

Josiah Ness

Addiel Perez, Ph.D.

Nick Roberts

John Rowan

Silverline Films

Patrick Williams

Ian Wilson

Bonefish & Tarpon Journal

2937 SW 27th Avenue Suite 203

Miami, FL 33133

(786) 618-9479

Carl Navarre, Chairman of the Board, Islamorada, Florida

Bill Horn, Vice Chairman of the Board, Marathon, Florida

Jim McDuffie, President & CEO, Miami, Florida

Harold Brewer, Immediate Past Chairman, Key Largo, Florida

Tom Davidson, Founding Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Russ Fisher, Founding Vice Chairman Emeritus, Key Largo, Florida

Bill Stroh, Treasurer, Miami, Florida

Jeff Harkavy, Founding Member and Secretary, Coral Springs, Florida

John Abplanalp

Stamford, Connecticut

Dr. Aaron Adams

Melbourne, Florida

Rich Andrews

Denver, Colorado

Stu Apte

Tavernier, Florida

Rodney Barreto

Coral Gables, Florida

Dan Berger

Alexandria, Virginia

Bob Branham

Plantation, Florida

Mona Brewer

Key Largo, Florida

Adolphus A. Busch IV

Ofallon, Missouri

Evan Carruthers

Maple Plain, Minnesota

Sarah Cart

Key Largo, Florida

Advisory Council

Randolph Bias, Austin, Texas

Charles Causey, Islamorada, Florida

Don Causey, Miami, Florida

Scott Deal, Ft. Pierce, Florida

Paul Dixon, East Hampton, New York

Chris Dorsey, Littleton, Colorado

Chico Fernandez, Miami, Florida

Mike Fitzgerald, Wexford, Pennsylvania

Pat Ford, Miami, Florida

Christopher Jordan, McLean, Virginia

Bill Klyn, Jackson, Wyoming

Andrew McLain, Clancy, Montana

Jack Payne, Gainesville, Florida

To conserve and restore bonefish, tarpon and permit fisheries and habitats through research, stewardship, education and advocacy.

John Davidson

Atlanta, Georgia

Greg Fay

Bozeman, Montana

Allen Gant Jr.

Glen Raven, North Carolina

John Johns

Birmingham, Alabama

Doug Kilpatrick

Summerland, Florida

Jerry Klauer

New York, New York

Wayne Meland

Naples, Florida

Ambrose Monell

New York, New York

Sandy Moret

Islamorada, Florida

John Newman

Covington, Louisiana

David Nichols

York Harbor, Maine

Steve Reynolds, Memphis, Tennessee

Ken Wright, Winter Park, Florida

Marty Arostegui, Coral Gables, Florida

Bret Boston, Alpharetta, Georgia

Betsy Bullard, Tavernier, Florida

Yvon Chouinard, Ventura, California

Matt Connolly, Hingham, Massachusetts

Marshall Field, Hobe Sound, Florida

Guy Harvey, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Steve Huff, Chokoloskee, Florida

James Jameson, Del Mar, California

Michael Keaton, Los Angeles, CA / MT

Al Perkinson

New Smyrna Beach, Florida

Chris Peterson

Titusville, Florida

Jay Robertson

Islamorada, Florida

Rick Ruoff

Willow Creek, Montana

Bert Scherb

Chicago, Illinois

Casey Sheahan

Bozeman, Montana

Adelaide Skoglund

Key Largo, Florida

Paul Vahldiek

Houston, Texas

Noah Valenstein

Tallahassee, Florida

Rob Kramer, Dania Beach, Florida

Huey Lewis, Stevensville, Montana

Davis Love III, Hilton Head, South Carolina

George Matthews, West Palm Beach, Florida

Tom McGuane, Livingston, Montana

Andy Mill, Aspen, Colorado

John Moritz, Boulder, Colorado

Johnny Morris, Springfield, Missouri

Jack Nicklaus, Columbus, Ohio

Flip Pallot, Titusville, Florida

Mark Sosin, Boca Raton, Florida

Paul Tudor Jones, Greenwich, Connecticut

Bill Tyne, London, United Kingdom

Joan Wulff, Lew Beach, New York

The startling results of a comprehensive study on the prevalence of pharmaceutical contaminants in South Florida bonefish underscores the urgent need for wastewater treatment reform. Alexandra Marvar

As BTT commemorates its 25th Anniversary, it remains focused on achieving lasting conservation outcomes benefitting the flats fishery. T. Edward Nickens

An accomplished angler and dedicated conservationist, Adelaide Skoglund has no plans of slowing down. Monte Burke

In the wake of Texas’ historic tarpon decline, BTT is unlocking the mysteries of the Silver King in the Western Gulf of Mexico. Chester Moore

The Belize government’s stance on the Blue Economy is not matched by the nation’s uncontrolled coastal development. Monte Burke

BTT and partners will restore vital mangrove habitats in Southwest Florida’s Rookery Bay for the benefit of fish and coastal communities. Michael Adno

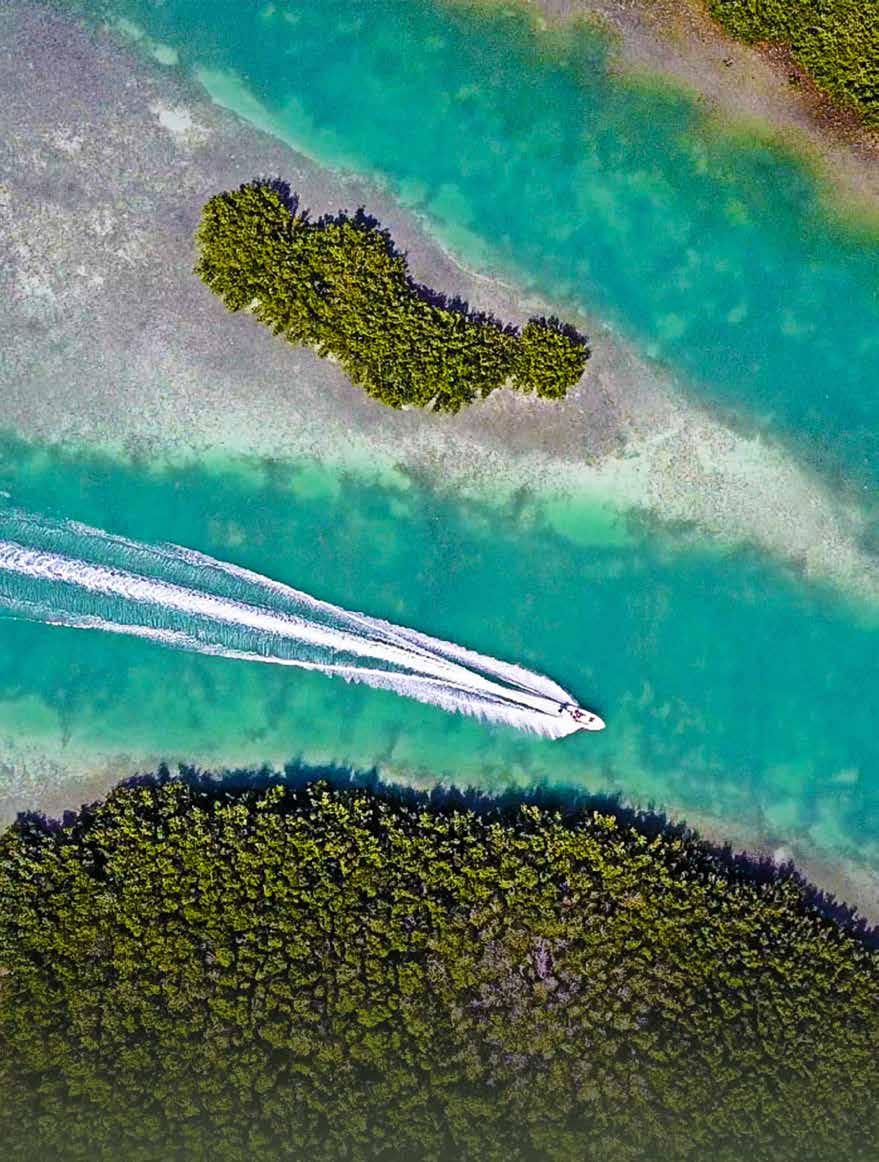

Mangroves in the Florida Everglades.

Photo: Nick Shirghio

Mangroves in the Florida Everglades.

Photo: Nick Shirghio

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, and what a long way we’ve come!

On the day that Tom Davidson and a small circle of visionary anglers established BTT on the flats of Key Largo, very little was known about flats species. Motivated by concerning declines in Keys bonefish, our founders passed the cap to fund some of the first research studies on the species, including the first tagging project to map bonefish home ranges.

Those steps taken in the late 1990s began piecing together a puzzle that has been substantially built out over the years thanks to BTT’s research. We’ve compiled volumes of new knowledge about slam species—their home ranges, movement patterns, spawning behavior, reproductive biology, and life cycle as well as the myriad threats to a sustainable fishery.

BTT has applied this new knowledge gained over the past 25 years to the important work of flats conservation, from the improved management of bonefish, tarpon and permit fisheries to the restoration and conservation of critical habitats in the US and beyond. And in doing so, the organization has grown from its grassroots beginnings in the Florida Keys to become the global leader in flats science and conservation.

These accomplishments give us much to celebrate. But as T. Edward Nickens writes in his fine feature article, “A Silver Celebration,” milestone anniversaries should be more than moments in time. For organizations such as BTT, they should also inspire a vision for how to pursue the mission in the future. We agree! On this occasion, BTT affirms its commitment to restore and conserve critical flats habitats in the US, the Bahamas, Belize and Mexico; to improve water quality through science and advocacy; and to strengthen fisheries management across the ranges of bonefish, tarpon and permit in this hemisphere.

We are already making significant progress toward these objectives, which is evident in these pages. Take, for instance, water quality.

BTT has been engaged in the fight to restore America’s Everglades for many years, including advocacy that helped secure authorization and funding of the EAA Reservoir—the critical centerpiece of a plan to store, clean and convey fresh water south to Florida Bay, the heart of Florida’s multi-billion-dollar recreational fishery. But water quality needs in Florida go well beyond the Everglades. A booming population and a water infrastructure outstripped by today’s demands introduce new threats to water quality, which are felt in every region in the state, from Pensacola to Key West.

As reported by Alexandra Marvar in “Are We Making Our Fish Dopesick?,” our collaborating scientists at Florida International University have discovered an invisible, insidious threat in the form of pharmaceutical contaminants. In a series of announcements earlier this year, BTT and FIU released the findings of the study, which sampled 93 bonefish in Biscayne Bay and the Florida Keys. A total of 58 different drugs were detected, with an average of seven drugs per fish. Antidepressants, antibiotics, blood pressure medications, pain relievers, even opioids. Not a single fish was clean! The problem isn’t

Carl Navarre, Chairman Jim McDuffie, President

Jim McDuffie, President

unique to bonefish. Contaminants were also detected in bonefish prey and will likely be found in other marine life—fishes, crabs, and lobster. The source of these contaminants? Wastewater and a water infrastructure no longer up to the task. Over the next five years, BTT will advocate for programs to reduce nutrient pollution and remove harmful pharmaceutical contaminants from our waterways, all while continuing to support expedited restoration of the Everglades.

BTT’s ongoing advocacy to improve water quality fits hand in glove with our rapidly expanding program to restore and conserve coastal habitats. As reported in this issue, BTT recently received a $250,000 grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, which will be matched by other funds, to plan coastal habitat restoration on Florida’s Gulf Coast. This follows our successful juvenile tarpon habitat restorations in the region as well as creek and mangrove restorations in the Bahamas.

In the newly funded project, BTT is working collaboratively with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to restore tidal flows to mangrove swamps and salt marshes in the Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Collier County, Florida. Success will prevent the loss of mangroves and provide more habitat for fish and other wildlife—and demonstrate how minimal alterations guided by science can provide major ecological benefits. This holds great promise for its application in similar sites across Florida as well as in damaged juvenile tarpon habitats throughout the Caribbean and Central America.

In addition to water quality and habitat restoration, BTT has made great strides in improving fishery management in Florida and elsewhere across the Caribbean Sea. Yet much work remains for us in the years ahead. BTT has committed to funding a monitoring project at Western Dry Rocks and three other Keys permit spawning sites to ensure data are available to guide future decisions by Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission on the spawning season, nofishing closure at WDR. And in Mexico, the first assessment of the flats fishery’s annual economic impact has been completed through BTT’s auspices, as reported in Chris Santella’s article in this issue. Such assessments have been important motivations in other countries for strengthening conservation-oriented management.

All that we have accomplished over these past 25 years—and the vision that these accomplishments frame for the future—would not have been possible without your generous support and advocacy for the fishery. It’s customary to celebrate the 25th with gifts of silver— we hope you’ll find yours on a flat this spring!

Kellie Ralston has been appointed Vice President for Conservation and Public Policy at Bonefish & Tarpon Trust.

Ralston served previously as the Southeast Fisheries Policy Director for the American Sportfishing Association.

“We are excited to welcome Kellie to our team,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “Her knowledge, experience and leadership will have an immediate impact on BTT’s efforts to conserve coastal habitats, improve water quality, and strengthen fisheries management.”

Prior to her tenure at ASA, Ralston worked at Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the Florida

House of Representatives, and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. In these roles, she was involved in a range of environmental, water quality, and fisheriesrelated issues.

“I am thrilled to join BTT’s respected team, where strong science helps inform policy,” said Ralston. “I look forward to using my experience at the state and federal levels to achieve conservation goals that benefit our fisheries and the environment.”

Ralston also serves on the Governing Board of the Northwest Florida Water Management District, an appointment made by Governor Ron DeSantis in 2020, and

Noah Valenstein, former Secretary of Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection, was elected to the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Board of Directors in December.

“It is an honor to serve alongside such a dedicated board and focus on protecting Florida’s fishing legacy,” Valenstein said. “The restoration of Florida’s water resources requires a science-based and collaborative approach, and Bonefish & Tarpon Trust has shown its commitment to both.”

Valenstein, who was first appointed to the DEP post in 2017 by Governor Rick Scott and subsequently re-appointed by Governor Ron DeSantis, also served as

the state’s Chief Resilience Officer. During his tenure, Valenstein championed water quality improvements, Everglades and springs restoration, coastal resilience, and conservation of Florida’s iconic lands.

A founding partner in the consulting firm Brightwater Strategies Group, PLLC, Valenstein was appointed by Governor DeSantis in November 2021 to the newly formed Biscayne Bay Commission. He also serves as a Presidential Fellow for The Water School at Florida Gulf Coast University and held past leadership positions on the United States Coral Reef Task Force, the United States Everglades Task Force, and the Environmental Council of the States.

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is pleased to welcome Whitney Wemett as Florida Keys Field Technician. Whitney grew up on the water in the Finger Lakes Region of Upstate New York and received her Bachelor of Science degree in Accounting and Environmental Studies from Stonehill College in Massachusetts. Whitney’s passion for island communities led her to work with local NGOs and fishers in Madagascar to establish science-based regulations to protect local fisheries and subsistent fishing practices in the island chain.

Based in Islamorada, Whitney is a trained scientific diver and PADI Divemaster, experienced mariner, and an environmental

writer committed to communicating science to the public. Throughout the Keys, Whitney leads grassroots campaigns, advocacy, and community-based ocean conservation programs with Surfrider Florida Keys, where she currently serves as Vice-Chair of the Executive Board. At the helm of the recent Key West cruise ship campaign, Whitney has worked with local fisherman, the Safer, Cleaner Ships Committee and her local community to defend ocean livelihoods and the fragile marine ecosystem the Keys calls home.

As the Florida Keys Field Technician, Wemett will combine her previous fisheries management and field experience to

NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Fisheries Advisory Committee that advises the Secretary of Commerce. She holds Bachelor and Master’s degrees in biology from Florida State University.

“Noah has had a profound impact on the conservation of Florida’s natural resources,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “The leadership, knowledge and commitment he brings to the BTT Board of Directors will ensure that we make the most of our opportunities to improve water quality, conserve coastal habitats, and strengthen fisheries management.

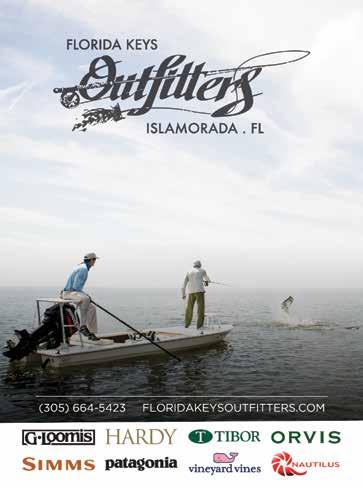

Partners In Preserving The Fish And The Places They Roam.

With the help of local fishing guides, students, and partner organizations, BTT has planted 20,000 mangroves in Grand Bahama and Abaco, marking a major milestone in the Northern Bahamas Mangrove Restoration Project. The five-year project seeks to plant 100,000 red mangroves in the areas hardest hit by Hurricane Dorian to restore vital bonefish habitat and strengthen coastal resilence. Visit BTT.org to learn how you can support this important work to ensure the future health of the Bahamas’ flats fishery and the communities it supports.

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) has awarded BTT a $250,000 grant to begin the restoration process for two degraded coastal habitats in Southwest Florida. The NFWF grant will provide funding to support restoration projects at Shell Island Road and Marco Shores Lake in Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (RBNERR), located within Collier County. Both sites have been impacted by alterations in hydrology and vegetation due to development and channelization of natural tidal river and creek systems. The restoration projects will bolster Southwest Florida’s coastal resilience, protect water quality, and improve vital nursery habitat for juvenile tarpon and snook, which support the state’s

saltwater recreational fishery, worth more than $9.6 billion annually. The work will be done in partnership with RBNERR and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

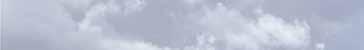

Don’t miss Bonefish & Tarpon Trust 7th International Science Symposium and Flats Expo on November 4-5, 2022, at the PGA National Resort in Palm Beach, Florida. Presented by Costa, this special two-day event will bring together stakeholders from across the world of flats fishing—anglers, guides, industry leaders, government agencies, scientists, writers and artists. The program includes presentations on major research findings along with spin and fly casting clinics, fly tying clinics, panel discussions with top anglers and guides, art and photography, and a banquet honoring legendary anglers Sandy Moret and Chico Fernandez and BTT Research Fellow Dr. Andy Danylchuk for their contributions to flats fishery conservation. The Symposium will also feature an expanded Flats Fishing Expo, where sponsors will share information about their products and corporate commitment to conservation. Space is limited, so visit BTT.org/Symposium to register today.

BTT is taking a collaborative approach to permit conservation in Belize by partnering with the co-managers of protected areas and government agencies. Dr. Addiel Perez, BTT’s Belize-Mexico Program Coordinator, recently participated in a new permit tagging project led by the Sarteneja Alliance for Conservation (SACD), Hol Chan Marine Reserve (HCMR) and the Belize Fisheries Department in northern Belize. The project is using tag-recapture to understand permit movements and the effects of fish traps. Learning more about permit movements and habitat use enables us to identify the habitats that should be prioritized for protection.

Since this new collaborative project between SACD, HCMR, BTT, and the Belize Fisheries Department spans the entire northern Belize region rather than only focusing on a particular protected area, the results will improve fisheries and protected area management. This is especially important for fish like permit that require multiple habitats throughout the region to complete their life cycle. Improved management includes better protections for the habitats on which permit depend, and properly managing fish traps to reduce the bycatch of permit, which are a catch-and-release species that cannot be harvested. BTT will continue to work together with Belizean partners to ensure the long-term health of Belize’s flats fishery and coastal communities.

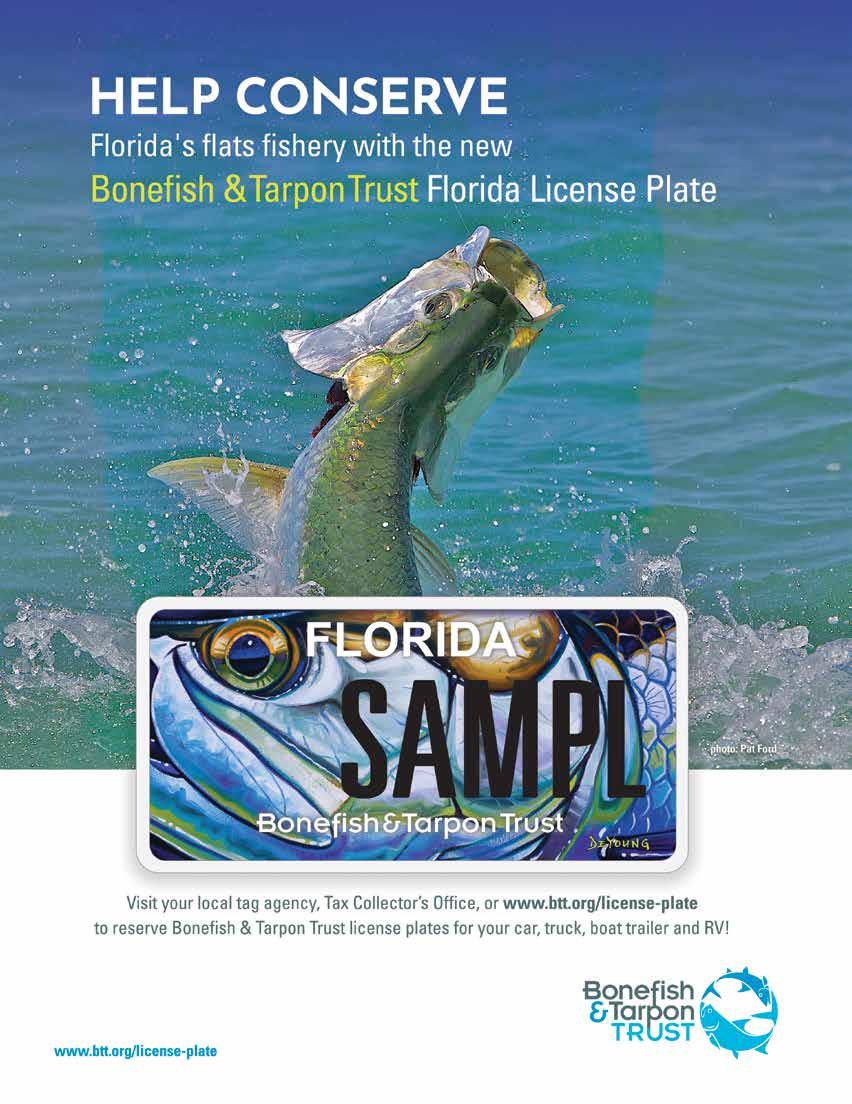

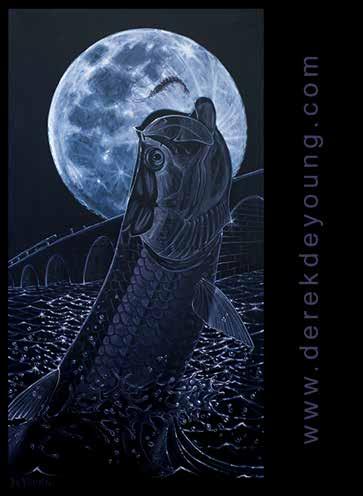

The new Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Florida license plate.

The new BTT Florida license plate, featuring the art of Derek DeYoung, benefits BTT’s efforts to conserve and restore essential juvenile tarpon habitat and improve fisheries management throughout the range of the species. To reserve plates for your car, truck, trailer, and RV, visit: www.btt.org/license-plate

The future of our oceans is in the hands of the next generation of anglers and conservationists. The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Youth Ambassadors Program recognizes outstanding young leaders in flats fishing and ocean conservation. If you or someone you know would like to participate, please visit BTT.org/ambassadors to learn more.

How prevalent are contaminants in the marine ecosystems along South Florida’s coast? And are they contaminants that could harm a $460-million-dollarper-year recreational fishery? These are some of the questions researchers at Florida International University had swimming around in their heads when, with help from colleagues at an ecotoxicology lab in Sweden, they screened a suspiciously frantic tank full of Florida bonefish for drugs.

In 2015, FIU coastal and fish ecologist Dr. Jennifer Rehage teamed up with Bonefish & Tarpon Trust to look into water

contaminants in critical bonefish habitats throughout South Florida and the Keys. Her team did a full review of published studies of contaminants in South Florida, as a first step in examining whether exposure to contaminants like heavy metals, PCBs, and pesticides might be a cause of the long-term bonefish population decline.

The following year, Dr. Aaron Adams, BTT’s Director of Science and Conservation, noticed something a bit strange about the South Florida bonefish in lab tanks at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute (HBOI) at Florida Atlantic University

that were part of the Bonefish Reproduction Research Project. Compared to bonefish caught in the Bahamas, South Florida’s fish were behaving rather strangely.

“The bonefish from Florida were frantic,” he recalled. “They were extremely spooky and would swim into the tank walls in panic. Why was this behavior different?” That’s when the researchers decided to screen for a different set of contaminants, and the early data painted a chilling picture: The Florida bonefish appeared to have taken in a dizzying cocktail of chemicals made for humans, from aspirin to antibiotics, and even opioids.

Rehage and BTT Director of Science and Conservation Dr. Aaron Adams agreed they needed to take a deeper dive. In 2018, BTT funded a three-year FIU research project to understand to what extent pharmaceuticals are present in bonefish in South Florida and numerous locations in the Caribbean to understand to what extent bonefish are being affected.

Researchers from Rehage’s Coastal Fish Ecology and Fisheries lab conducted catch-and-release testing of 136 bonefish in Biscayne Bay, throughout the Keys, and in the Caribbean, obtaining fin clips and blood samples that they then screened for 104

common drugs—antibiotics, hormones, pain relievers, betablockers, estrogen mimickers, steroids, and more.

The team also looked for these substances in other species that dwell in bonefish habitats, including crabs, shrimp, barnacles and swimming baitfish. This broader survey is designed to provide clues as to just how bonefish are being exposed to these waterborne contaminants, which can settle in seafloor sediment, get taken up by organisms that are prey for bonefish, or are dissolved in the water column.

The most surprising thing about the findings for Castillo is the sheer number of substances the team has uncovered so far. A former full-time fishing guide who lived and worked in Islamorada, Castillo carried out the contaminant study as his Ph.D. thesis. Across all five regions, he says, the samples revealed that every single bonefish they caught had traces of pharmaceuticals in its blood. “There aren’t any clean fish,” he says. “We’re finding at least one pharmaceutical in every single one.”

When humans take a drug, Castillo says, they metabolize the chemical within hours or days, and it leaves their bodies. The bonefish, however, are constantly swimming in water that may be contaminated by pharmaceuticals; the drugs they’re exposed to are being administered at a low but prolonged, maybe even constant, dose. Another layer of complexity, Castillo adds, is that these bonefish aren’t ingesting just one substance at a time. The average number of pharmaceuticals per fish is between five and six, and some outliers had traces of as many as 17 different drugs in their systems.

Of all the substances on the list, the team paid special attention to one class in particular: psychoactives, such as anti-

anxiety medications and antidepressants. Fish have receptors for these chemicals that are not so different from humans, and according to Rehage, there is plenty of evidence already that these drugs, which are designed to make humans feel less anxious, less fearful and more carefree, may have similar effects on fish. And in the case of a fish in the wild, being carefree isn’t necessarily an advantage.

So, what does prolonged exposure to a grab bag of pharmaceuticals mean for a bonefish? Previous studies in Europe offer clues: Not so surprisingly, when a fish is exposed to foreign substances designed to manipulate the brain or biology, strange things seem to happen.

In the UK, past research found that on the Thames River in London, the presence of artificial estrogen hormones (like those found in birth control) was so high that male fish reportedly developed ovaries—a phenomenon reported by local sport fishermen as early as the 1980s. And in 2013, researchers from Umeå University in Sweden, who are collaborating with the FIU team on their study, published a study on how medications like Valium, Xanax and Oxazepam in diluted doses were shown to alter the brain chemistry of European perch and profoundly change their behavior.

“They became more active, they became asocial, and they became risk-taking,” Umeå University’s Dr. Tomas Brodin, who led the research, explained at a press conference at the time. “We do daily care on these fish. On day three, without knowing [which fish were dosed and were not], I could tell which fish were exposed.”

Because these perch took more risks, the data showed, they also tended to get eaten faster by predators.

In 2019, that team published findings of similar effects in hatchery-reared Atlantic salmon, which, when exposed to antianxiety medications, became bolder, less vigilant of threats, and they migrated faster than salmon that were not exposed.

Through these studies, Rehage says, researchers are trying to determine not just the downstream effects of these drug-induced changes to fish feeding habits, spawning, migration, schooling, sociability, and other behaviors—changes that certainly affect individual fish, Rehage says, but also come with population-level repercussions.

“These [previous] studies found that all these different aspects of the way fish interact with the environment are altered,” she says, “and in the end, they have lower survival rates. Their different behaviors are not in tune. They’re just acting. They’re not afraid—and it gets them killed.”

So far, there hasn’t been research done as to precisely how these drugs impact bonefish specifically, but Adams says there

are plenty of reasons to hypothesize that behavior changes in bonefish would echo those of previously studied fish species.

“If pharmaceuticals cause bonefish to migrate earlier, then fish that are exposed to pharmaceuticals might show up the week before all the other fish,” Adams says.” If they migrate by themselves rather than with a large school, they’re more likely to get eaten.” When bonefish do reach the spawning site, a series of complex behaviors is set in motion, spurred along by factors as nuanced as a few-degree change in water temperature or the phase of the moon.

“We don’t know the extent to which pharmaceuticals might

affect egg development or sperm development,” Adams adds, “and we don’t know how they could impact spawning behaviors, either.” And after spawning, he says, bonefish still need presence of mind for the important task of finding their way back home again.

Unlike other contaminants which degrade over time, researchers have learned that pharmaceuticals stay in the water. Worse news yet, Rehage says, is that the amount of contamination flowing from land to sea increases each year.

In 2020, 6.3 billion prescriptions were dispensed to an estimated 72 million Americans. Antidepressant use alone has more than doubled in the past two decades, according to an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development survey of data from 38 countries. And in the U.S., the percentage of people taking these drugs increased sixfold between the landmark launch of Prozac in 1988 and 2014.

Plus, new drugs are entering the system all the time: Global healthcare analysts forecast that more than 50 new active substances will launch annually—each with its own unforeseeable long-term impacts on marine life.

“We have this tremendous amount of production in pharmaceuticals which is currently unregulated,” Rehage says, “and while they’re really important to our health and quality of life, we need to figure out what we can do to make them so they don’t pollute our environment or have these side effects on wildlife.”

Some countries, Sweden included, are neutralizing or mitigating the threat in wastewater with special water treatment infrastructure, implementing processes like ozonation to break down pharmaceuticals, or granular activated carbon to filter them out. In the U.S., however, these systems are not yet in place.

To Rehage, the study isn’t just about the bonefish fishery: It’s about all marine life, and humans too. If these contaminants are so impervious to wastewater treatment that they have become this prevalent in the ocean, she notes, they are also in drinking water.

“Bonefish are kind of a canary in the coal mine, just telling us they’re unfortunately picking up all these pharmaceuticals just by doing the things they do,” she says. “If we’re not going to make them better, we need to figure out how to clean them up. We don’t

Nick Castillo releases a bonefish after sampling it.

Photo: Florida International University

Seine nets are used to collect bonefish prey from the flats to sample for pharmaceuticals. Photo: Ian Wilson

Nick Castillo releases a bonefish after sampling it.

Photo: Florida International University

Seine nets are used to collect bonefish prey from the flats to sample for pharmaceuticals. Photo: Ian Wilson

need to be exposed to pharmaceuticals we didn’t sign up for. It’s not fair to the bonefish, and it’s not fair to us.”

According to Adams, in Florida, this contamination issue may be further exacerbated by the state’s buckling water infrastructure. Shortcomings in wastewater treatment from septic and sewage treatment to stormwater runoff, he says, may be amping up exposure for South Florida’s bonefish populations.

“Bonefish feed in nearshore habitats which are closer to the outflows,” Adams says, “so they likely have higher exposure rates than fish that are offshore. They could get the pharmaceuticals straight from the water, or from eating prey, and that input could come from septic systems leaching into the water table, and then that fresh water seeping into coastal waters. Alternatively, they could get it from sewage outfalls. Florida has sewage outfall issues virtually every time it rains. They could also be getting it from discharged, treated sewage effluent, as Florida doesn’t have the technology at the sewage treatment plants to remove pharmaceuticals.”

He adds, “I wish I could say that pharmaceuticals occurring in animals is Florida’s one big water problem, but it’s not. It’s one of many things indicative of outdated and overwhelmed water infrastructure. Pharma is important, but it’s also just one piece of a huge mess.”

According to BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie, the findings have created a responsibility for the organization at large. “These research findings should sound alarms everywhere along Florida’s coast,” and knowing what we now know, he says, BTT has stepped up to advocate for policy changes in Florida to address the key role of the state’s buckling water infrastructure in constantly dosing the bonefish fishery with behavior-altering substances.

“The presence of pharmaceutical contaminants in a valuable recreational species like bonefish is one of the factors degrading habitat and water quality, and that poses a threat to so many things: the livelihoods of guides, the economic benefits provided to the state by the fishing industry, the sustainability of the fishery itself,” McDuffie says. “If we’re going to be true to our mission as an organization, then we have to be in this space, advocating for improvements and wastewater infrastructure.”

The state is taking steps to address these issues, McDuffie noted, with a new and expanding wastewater grants program and other state investments in modernizing wastewater infrastructure. “It’s a great start,” he added, “yet these findings underscore the urgency of doing more and doing it faster.”

Of course, the solutions to big, complex problems are multipronged. This one will require regulations and policy, innovation and technology, and, Nick Castillo says, the continued involvement of bonefish anglers and guides, which has been indispensable so far. He thinks back to his days on the bow of the BTT skiff looking for the telltale glints of silver in the shallows, angling for samples to flesh out the contaminant study’s data.

“My expertise was the Upper Keys and the Everglades, not Biscayne Bay or the Lower Keys or Key West,” Castillo says of his angling and guiding experience. “I would absolutely not have

been able to catch these fish if it wasn’t for the support and the help of the guiding community and anglers in general. These are the people who are out there every single day,” he adds. “The alarm would never have been sounded that there was a problem if it wasn’t for fishing guides, telling scientists, ‘Here’s what we see happening.’”

Alexandra Marvar is a freelance journalist based in Savannah, Georgia. Her writing can be found in The New York Times, National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine and elsewhere.

“If we’re going to be true to our mission as an organization, then we have to be in this space, advocating for improvements and wastewater infrastructure.”

As BTT commemorates its 25th Anniversary, it remains focused on achieving lasting conservation outcomes benefitting the flats fishery.

Even in the early days, before there was a Bonefish and Tarpon Unlimited, the predecessor to today’s Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, science was at the core of it all. In early 1997, six friends turned their worry over declining Florida Keys bonefish into action, and kicked off a two-year effort (and contributed $10,000 each) to contract the University of Miami for an inventory of the published science of bonefish ecology, and commence a bonefish tagging program to fill in the many blanks of what was known about bonefish ecology. The organization’s name would change in 2009 to BTT, but from the beginning, the underpinning of science for all action was paramount.

It’s only now, two-and-a-half decades later, that being so

rooted seems so visionary.

BTT turns 25 years old this year, and it’s an intriguing milestone for any number of reasons. For starters, a 25th anniversary is typically celebrated with gifts of silver, and there’s nothing like silver to stoke the BTT crowd.

But 25 years should serve as a different sort of marker for a healthy organization, one that is as forward-looking as it is retrospective. BTT’s legacy over the last quarter-century is largely anchored in a hard-won storehouse of scientific study, a required priority given the relatively barren landscape of understanding about flats fishes and flats ecology in those early years. Now that purposeful approach will power an elevated and results-oriented

emphasis on engaging some of the most profound challenges facing flats fisheries.

“We have always been grounded in solid science,” explains Jim McDuffie, BTT president and CEO. “And science for a purpose— conservation. As we move into the future, science will inform our work at larger scales and in even more impactful ways. All that we’ve already accomplished over the past 25 years prepares and inspires us for the way forward.”

Three primary spheres of endeavor mark BTT’s work in the organization’s 2025 Plan—improving water quality, restoring and conserving coastal habitats, and improving fisheries management across the range of slam species.

And as it was in the beginning, science provides the foundation for it all.

In 2018, BTT collaborating scientists made a startling discovery: In the flesh of two Upper Keys bonefish they found detectable levels of nine different prescription drugs, including the opiate Tramadol. Since that initial study, more work has shed light on the depth of the problem: In a study of 136 bonefish from the Florida Keys, the Bahamas, Belize, and Mexico, pharmaceuticals were found in every single fish. One Keys bonefish carried 17 prescription drugs in its blood plasma. A

Grand Bahamas bonefish carried three. In the entire sampling, 58 different pharmaceuticals were found. Among the most common were antidepressants, known to depress the activity of fish larvae and foraging behaviors in adult fish.

The findings gave added urgency to an issue that had already been a focus of BTT for years, and is one of the most far-reaching, contentious, and impactful issues facing flats fishes and flats conservation—water quality. While Florida’s water woes and pollution across the region have long been a part of the BTT conversation about the health of flats fisheries, the discovery of bonefish awash in prescription-drug-laced water underscored the need for a decided emphasis on the soup of ills that sully the water in even the most remote regions.

That study, says McDuffie, “provided renewed focus and a new policy angle to address the urgent water infrastructure issues impacting the flats fishery.” Florida’s water quality faces serious problems, from outdated and outmoded wastewater treatment facilities to agricultural runoff to outright habitat destruction. “Our mantra has always been that clean water equals healthy habitats. It we lose water quality, we’ll lose habitats, and if we lose habitats, we’ll lose our fishery, says McDuffie. “These findings make clear there is a new and serious threat emerging that should give us more leverage in our water quality efforts.”

The organization’s recently approved five-year plan comes with a decided emphasis on conservation action wherever it’s needed— in the water, on the ground, and in government offices at every

level. Under water quality, BTT will support expedited Everglades restoration while also advocating aggressively to reduce nutrient pollution and remove harmful drugs from state waterways. And the timing is auspicious with new attention in Tallahassee and D.C. on infrastructure and coastal resilience needs, including new policies and historic funding levels advanced by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and the state legislature.

“Our founders probably never imagined that one day we would be walking the halls of Tallahassee and Washington, D.C. to advocate for an overhaul of wastewater management in Florida,” says McDuffie. “Working to restore the Everglades, yes, and efforts to prevent the loss or degradation of flats habitats, absolutely. But now our science has led us to an additional threat, which brings even greater urgency to addressing water quality issues. This and other threats originate far from the flats and are invisible to us.”

BTT’s scope of work at 25, especially in the habitat conservation arena, is a perfect example of how scientific discovery grades seamlessly into policy and management decisions. Case in point: Hurricane Dorian’s 2019 devastation of 69 square miles of mangroves on Grand Bahama and Abaco islands. The herculean and ongoing effort to restore those mangroves is an all-encompassing initiative between BTT and partners at the Bahamas National Trust, Friends of the Environment Abaco, and the fishing apparel company, MANG. Not surprisingly, it started with science: How do you assess the damage at that scale, and design an effective planting plan? How do you collect and raise mangrove propagules, and transport and transplant them, on a near-landscape scale?

The ongoing rescue effort underscores the importance of BTT’s commitment to habitat. “The mangrove restoration effort in the Bahamas is a big challenge because of the spatial scale. But we have the advantage of working in habitats that prior to Dorian were healthy and intact,” says BTT’s Director of Science and Conservation, Dr. Aaron Adams. “In Florida, we’re also dealing with the outright loss and degradation of habitats due to coastal development, so here it’s a matter of fixing what we’ve broken in the past.” Researching and advocating for storm buffering and coastal resilience policies is a big piece of the picture. But across much of Florida, and growing in threat level in the Bahamas, Belize, and Mexico, rapid, unwise, and unplanned development chews through critical habitat for tarpon, bonefish, permit, and snook 12 months a year, paving over wetland habitats and turning nearshore coves and bays into near wastelands for young fish.

Hands-on restoration work is an ongoing and growing part of BTT’s work. Responding to site-specific habitat threats has already informed work in one of BTT’s most exciting initiatives—the restoration of juvenile tarpon nursery habitats in Florida. Young tarpon need tidal mangrove creeks and shallow backcountry shorelines for protection from predators and for their easily obtainable food sources. But these habitats are in the crosshairs of development in Florida, and even where they remain intact, nutrient runoff and altered water-flow regimes can diminish their values for young tarpon and snook.

Incorporating habitat considerations into fisheries management may be new thinking, but BTT is well on its way to showcasing how the new approach can work. BTT launched its Juvenile Tarpon Mapping Project in 2016, under the guidance of project manager JoEllen Wilson. Working with recreational anglers and guides, BTT mapped 289 Florida habitats of critical importance to juvenile tarpon. Some are in good condition, and require only

protection to safeguard their values for young tarpon. Others need to be restored before protection. To learn how best to restore an individual nursery site, BTT scientists analyzed three different nursery habitat designs to tease apart what elements best support growing young tarpon.

BTT is now working on prioritizing the habitats in terms of threat level and importance to tarpon populations, and recently received a $250,000 matching grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to restore 1,000 acres of two degraded mangrove habitats in Rookery Bay. The work will significantly boost storm surge protection, while bringing back the critical nearshore mangrove habitats required by young tarpon and snook. Wilson underscores BTT’s approach to habitat protection and restoration: “Our approach is collaborative, from working with guides and anglers to identify and characterize juvenile habitats to working with resource management agencies to revise approaches to include habitat as a core component of management. We put so much emphasis on juvenile habitats because these habitats provide the future for the fishery.”

It’s an approach whose time has come. “As common sense as it sounds, habitat conservation has not been a significant part of fisheries management,” explains Eric Sutton, executive director

of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. “But bag limits, size limits, an emphasis on catch-and-release fishing, and other regulatory tools are not the only factors we have to consider. Habitat quality and water quality are of critical importance, and that’s a whole new paradigm in how we manage fisheries.”

But that doesn’t mean that traditional fisheries management approaches are in the rearview for BTT. New research is providing increasingly powerful arguments for regulatory change.

It was the multi-year saga—both scientific and sociological—of revising permit management that perhaps best illustrates how BTT works in the fisheries management realm. Through Project Permit, BTT spent more than a decade tagging permit with dart tags, followed by five years of tracking permit movements with acoustic tags. The first goal of the research was to determine if the Special Permit Zone, which encompasses the Florida Keys and Biscayne Bay and was implemented by FWC in 2011, is large enough to protect the flats fishery. It is—very few permit from the Keys leave the SPZ. The project also revealed habitat use by permit, and demonstrated that Western Dry Rocks is an essential spawning site for flats permit. BTT built a coalition with the guide

and angling communities to advocate for a seasonal closure at WDR to protect spawning fish. When a four-month-per-year no-fishing closure was enacted by FWC in early 2021, it marked a watershed moment that proved how science-based advocacy could work to bolster fisheries resources.

“One of the last things we ever want to do is enact a closure,” explains Sutton. “Access to the resource is fundamental for conservation. But we knew that something was going on at the Western Dry Rocks, and without BTT I don’t think we would have found the sweet spot for closing a site to fishing while being mindful of so many opinions and perspectives.”

Dealing with fisheries management issues will also involve a greater influence in one of the most-overlooked aspects of marine conservation—human behavior change. It’s another example of how BTT’s 25-year heritage of scientific rigor is paying dividends in surprising ways. “BTT has been so involved in educating not only guides but the fishing public,” says Will Benson, a fishing guide, member of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council, and recent recipient of BTT’s Flats Stewardship Award. When it comes to fighting times, awareness of predators

while fighting fish, and safe handling techniques, he explains, “BTT puts the science behind responsible angling.” As more and more people flock to the flats, an even greater awareness of individual behaviors will be critical to prevent flats scarring from boat propellers and shoreline and reef damage from boat wakes. Which means that the future for flats and flats fisheries is the responsibility of every single person drawn to these fragile habitats. That was the vision of BTT’s founders 25 years ago, when six individual anglers stepped up and stepped out to partner with scientists in an epic journey of discovery. And it’s the vision of a BTT looking forward to a new era of working more directly for change. “We can’t wait any longer, to be honest,” urges Benson. “There is a genuine fear that there’s not much time left to stop the slope of loss we’re experiencing in the fisheries. This is a critical time to pivot towards action.”

A dedicated conservationist and accomplished angler with no plans of slowing down.

One day while fishing for tarpon on the ocean side of Duck Key with guide Dustin Huff, Adelaide Skoglund was forced to face what is perhaps her greatest fear. Though she has been fishing since she was a very young girl—starting with a cane pole and worms in a farm pond—and though she is among the most passionate of tarpon anglers you’ll ever meet, spending close to 50 days a year fishing for her favorite species, and though she is, as Huff describes her, “a total sport and always up for anything,” Adelaide happens to be deeply and darkly afraid of the water. “I love being on the water,” she says. “I do not like being in it at all.”

That day off Duck Key—a place known for its sometimesrowdy water—Huff’s boat pitched in some waves, and Adelaide fell off the deck and rolled overboard, going all the way under. “When she came up, she had a look of sheer panic in her eyes, the most terrified look I’ve ever seen,” says Huff. The Buff Adelaide was wearing over her nose and mouth added to the terror by making it harder for her to get air after resurfacing. “She looked like she was being waterboarded,” says Huff.

Adelaide eventually ripped down the Buff and took some deep breaths, and was helped back into the boat by Huff. “Once I knew she was okay, I couldn’t stop laughing,” he says. Adelaide began to laugh, too. And then, after taking just a moment or two to compose herself, she grabbed her rod and took her place in the bow again, and the duo continued to fish.

Adelaide Skoglund, 73, has, as Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s Vice Chairman Emeritus Russ Fisher describes it, “a go-for-it personality.” That personality has led her to live an enviably sporty life. Among other things, she has bred and trained champion trotting horses, hunted for quail, caught a 150-pound tarpon and a three-foot-long bonefish, helped start one fishing tournament and gone on a John Wooden-like championship run in another and played to as low as a three-handicap in golf.

That personality has also led her to become someone who, put simply, gets things done. She has, over the years, played a significant role in the rebuild of the chapel and the transformation of the medical center at the Ocean Reef Club, and spearheaded the renovations of the clubhouse at the Card Sound Golf Club. And, of course, she was a founding member of BTT, responsible for some of the most critical fundraising efforts in the organization’s early years. Adelaide is the type of person who doesn’t always get the recognition she so richly deserves, because her efforts are in the local community or, as in the BTT fundraising, just outside of the limelight. And yet, she is precisely the type of person who makes this world go ‘round. “If Adelaide were a Catholic saint, they’d have built a cathedral to ‘Our Lady of Excess’ in her honor,” says her long-time companion, Bill Legg. “She’s always moving. There is never a dull day with Adelaide.”

**

Adelaide grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina. Her father, David Johnston, raised standardbreds—first on a farm outside of Charlotte and then in Paris, Kentucky—and was the head of the United States Trotting Association for many years. “Dad had me in his arms when I was three months old on a 20-year-old pony

that had a swayback down to the ground,” she says. Adelaide has ridden all of her life and, for many years, showed hunters and jumpers.

Adelaide went to Sweet Briar College in Virginia, majoring in art history, then returned to Charlotte. There, she worked as an assistant education director at the Mint Museum, training docents and working on catalogues, and in a couple of galleries before receiving an offer to run an antique and decorating store owned by a cousin. She accepted the job, but asked for time off before she started.

During that time off, she traveled with her parents to Lexington, Kentucky, to attend the Tattersalls horse-sale event. While there, she went next door to the Red Mile Racetrack, an iconic trotting horseracing venue, and met a man named John Skoglund. She didn’t know it at the time, but she and John already had a connection: John, who was also in the trotting horse business, had purchased some horses from Adelaide’s parents many years prior.

Adelaide never would run her cousin’s antique and decorating store. She and John were married and moved to Minneapolis, where John was an owner of an outdoor advertising company and the chairman and part owner of the Minnesota Vikings (John’s father, H.P., was one of the original owners of the team).

The Skoglunds also remained in the horse business, where they had some incredible success. They bred Tagliabue, a horse named after their friend, Paul Tagliabue, who was the commissioner of the NFL at the time, which won the 1995 Hambletonian Stakes. (The couple also bred horses with other football-related names, like Double Coverage and Herschel Walker.) And in 1997, the Skoglunds’ horse, Must Be Victory, won the Hambletonian Oaks, which is among the most prestigious events in the sport of horseracing.

After learning to fish with that cane pole, Adelaide eventually graduated to a spinning rod, and her parents began bringing her and her brother along on fishing trips to the Florida Keys. “Dad loved to fish,” she says. “But I think Mom loved it even more.” On one of her first trips to the Keys, her family fished with the Knowles brothers (her parents fished with Billy; she and her brother fished with Ralph). Over the years on those flats, they hooked and landed tarpon, bonefish and cobia. On one trip, she and her brother caught several permit with live crabs and spinning rods under the Channel 2 bridge. With the last crab on the boat, her brother caught a “40-some pounder” that qualified as a junior record in the Metropolitan Miami Fishing Tournament. Her mother, in another boat, caught a 42-pounder that same day.

Adelaide says that in her late teens and early 20s, with college and her horses and her work, she drifted away a bit from fishing. But that changed when she met John.

John was an avid angler and a co-owner of a 50-foot Hatteras mothership named Hope, which had a crew out of McLean’s Town in Grand Bahama. (John and Adelaide turned out to have another unknown, pre-marriage connection: Adelaide’s parents were also co-owners of the boat, though they never fished with John.)

On their second wedding anniversary, John gave Adelaide a 12-weight tarpon rod. One day on the water, a guide taught her how to double-haul. “I worked so hard and was so spastic at first,” she says. “But when I finally got it down, it was like someone had given me the greatest gift in the world.”

But soon afterward, Adelaide had her second respite from fishing. After she and John moved to Ocean Reef in 1982, Adelaide focused mostly on golf. She had been the champion at her club in Minneapolis and, within short order, became the champion at Card Sound. Adelaide sees some parallels between golf and tarpon fishing with a fly rod, in the swing—the acceleration, the weight change, the timing, the importance of staying on the same

plane—and in the nerve. Standing over a five-foot putt to win a match, she says, “is like seeing five big tarpon swimming at you on a flat.” (Perhaps it’s no coincidence that some other great tarpon anglers—like Andy Mill and Dustin Huff—are also excellent golfers.)

In the late 1990s, John sold his interest in the Vikings and then became sick with lung cancer. He passed away in late 1999. In the summer of 2000, in an effort to raise her spirits, BTT Chairman Emeritus Tom Davidson and the late Joel Shepherd, a BTT founding member, invited her to fish with them in Colorado. “I went and had a great time,” says Adelaide. And then she came back to Ocean Reef and, through a bit of serendipity, rediscovered her love of fishing.

gourmet lunches. “One of my most memorable days on the water was with them, when we hooked 29 tarpon on the bay side of Key West,” he says. It was with Huff that Adelaide also caught her biggest tarpon, which was an estimated 150 pounds. “She is so incredibly coordinated,” he says. “She has impeccable form as a caster.”

For 15 years starting in the 1980s, Bill Legg’s wife, Judy, and a few of her girlfriends from Baltimore would make an annual pilgrimage down to Ocean Reef, leaving their husbands behind.

“They called it the ‘Tired Mothers’ group,” says Legg, now a retired investment banker. On those trips, Judy would often rope in Adelaide as a “fourth” for a round of golf. Adelaide would eventually help the Leggs get into Card Sound after they purchased an apartment at Ocean Reef.

Judy developed breast cancer around the same time that John got sick. She passed away shortly after he did, in early 2000. After Adelaide returned to Ocean Reef from her Colorado trip in the summer of 2000, Bill called her one day. “I hadn’t really ever met her,” he says. “I just wanted to stop by and thank her for being a friend to Judy.” Something clicked that day. Bill and Adelaide have now been companions for 22 years.

And they’ve spent much of their time together on the water. “That was when I got really into tarpon fishing,” says Adelaide. “I love it so much and I got addicted and still am.”

The duo fishes all over the Keys with a handful of guides—Will Benson, Andy Thompson, Bob Branham, Jared Raskob, Diego Rouylle and Huff among them. Huff, like his father, Steve, has always had a rather static list of clients, and Bill and Adelaide, despite their efforts, couldn’t book any time with him for years. But in 2003, on the day that one of Huff’s longest-tenured clients, Del Brown—who booked Huff for more than two months a year— died, a friend of Bill’s emailed him a simple message: “Del dead. Call Dustin.” Adelaide and Bill now fish with Huff for around nine days a year. “We have such a great friggin’ time together,” says Huff. Adelaide “cusses like a sailor” says Huff and makes huge,

Benson, who has been guiding Adelaide and Bill for a decade, echoes that sentiment. “She’s a really good caster and an expert at feeding the fish,” he says. Adelaide once hooked 16 tarpon in a day with Benson. “My three days with them are always the best of the year,” he says. “Adelaide always seems to bring some good luck with her on the boat.” She also, it seems, brings some other things, as well. “I have to completely empty my boat before Adelaide comes down because she takes along so much stuff,” Benson says. “She has, like, three changes of clothes, a giant lunch, camera equipment, tackle boxes, you name it. It looks like she’s packed to go to Australia for a month.” What Adelaide lacks in weight with her slight frame, says Benson, “she more than makes up for with all of that stuff.”

At Ocean Reef, Adelaide used to host an informal get-together with a group of fellow fly-fishing women. They talked knots and practiced casts in the vacant lot across from her house. One of those women, Nancy Zakon, helped the group establish itself as The Bonefish Bonnies and in time, they decided to start an equally informal flats tournament. Adelaide ran it for a while as it grew. “We had a ball with that,” says Adelaide. “We had prizes for things like the best lunch and the best-dressed captain.”

Though Adelaide says she doesn’t really enjoy formal tournaments, she has, for the last decade or so, dominated the fly division of the season-long Key Largo Anglers Club tournament. She tends to outwork most of the other competitors. “Early in the morning, you’ll see her staked out at Curtis Point with her guide, waiting for the tarpon,” says Russ Fisher.

Though Adelaide has had some excellent bonefishing days— she briefly had the record for the species on 20-pound tippet, once caught a 36-inch bonefish that weighed an estimated 16 pounds and caught one to cap off a grand slam one day—tarpon are her jam. “They are my favorite fish by far,” she says. That love makes her a very eager angler. “If I were to be tactless about it, I would describe Adelaide as a ‘bow hog,’” says Legg. Davidson, who has fished with her many times, agrees. “You really need to be careful or she will push you right off the bow to get her turn at bat.” In her defense, Adelaide says she has no defense. “Yeah, I fight for the bow.”

Adelaide says there isn’t one tarpon that stands out for

her—not even the big one she caught with Huff. “They’re all memorable to me. I actually feel like I can remember each one I’ve caught.” These days, she no longer likes to exhaust the fish— or herself—by fighting them all the way in. She goes by the Stu Apte 20-minute rule: fight them hard for a short amount of time, get a jump or two, maybe get the leader knot in the rod, and then pop them off. “I do the same with bonefish,” she says. “I would die if I saw one of my fish get eaten by a shark.”

In a significant way, Adelaide is a precursor to an entirely new generation of women anglers who have (thankfully) flooded into the sport. She may not be as well-known as Joan Wulff or even Zakon, but her dedication and love of the sport have set a standard. “When I came along, it was weird that a little girl wanted to fish,” she says. “And now to see women like Alex Lovett-Woodsum, who is passionate and a great caster, is so cool. Some women in the sport now don’t do it for the right reasons. It seems to be a means to an end for them. But the real deals are awesome. They’re out there because they enjoy it, not because they want to impress some guy.”

A few years ago, a friend of Legg’s was out on a point by Ocean Reef, fishing for tarpon. Another boat was maybe 80 yards away, and the angler in the bow was tossing graceful cast after graceful cast. Legg’s friend turned to his guide, amazed, and asked: “Who is that guy on the bow?” The guide replied, simply: “That’s no guy. It’s Adelaide.”

even with all of the retired CEOs and high-powered lawyers around here,” says Legg. “She never quails in the face of a large, complicated and politically-charged decision. She takes it on and doesn’t ask for anything. Getting it accomplished is her reward.”

Adelaide was a fundamental piece, too, of the birth and establishment of the BTT. Every nascent organization needs funding. Adelaide, now a board member of BTT, was one of the first founding members that Davidson and Fisher handpicked. Says Davidson: “We picked her because of her passion for fishing and her skill at raising money.”

Adelaide hosted fundraisers at her house—which included dinners with Apte and Chico Fernandez—that raised tens of thousands of dollars and got BTT up and running. She also helped establish the “Artist of the Year” program, which has been a boon to fundraising efforts. “I didn’t have anything to do with the direction of the organization, but I helped where I could,” Adelaide says. The work of BTT, she says, is vital. “I say this sincerely: If there’s a shot at saving these species, it will come through BTT. What they did at Western Dry Rocks in helping push through the protection of spawning permit is a great example.”

Adelaide’s help was crucial, according to Davidson. “Otherwise, we were just three people holding down chairs in a board meeting,” he says.

When not on the water, Adelaide is never idle. She plays golf, tends to her orchids (she has two named after her) and collects sporting art and duck decoys. And she has dived, headfirst, into any project that’s worthwhile and needs help. When the chapel at Ocean Reef needed to be redone, she was invited to be on the committee, even though she’s not a regular churchgoer. With the Card Sound clubhouse rebuild, the board, not by coincidence, planned the teardown and reconstruction during her term as president, and even extended that term so she could see it through. And the total reinvention of the Ocean Reef medical center, done with Tom Davidson, became her passion. When she first arrived at Ocean Reef, the medical center was not much more than a “doc-in-a-box”-type clinic. She became the chairman of the board and raised some serious money, and now the clinic is world-class, with four full-time doctors and a nurse practitioner and 46 specialists who come through periodically.

“If Adelaide believes in something, she will run it and she doesn’t mind stepping on toes and using her sharp elbows to get it done,

“That’s not worth much without the contribution of Adelaide. She is a very good broker of social power.” Says Legg: “Someone has got to make these things happen. Whatever needs funding, she will pony up herself and then get the rest of us to pony up as well. Adelaide is very expensive to live with. But she never does any of this for the notoriety. She does it because she enjoys it or because it is the right thing to do.”

Indeed, she is not one to seek any accolades for her work. “I feel like I haven’t done anything special,” she says. Which is, perhaps, precisely why and how she has managed to do so many special things.

If Adelaide has one fault, according to her friends, it is her propensity for tardiness. “Adelaide’s idea of being on time is to arrive 30 minutes late,” laughs Davidson. But, given her personality, this seems to be a highly-forgivable trait. After all, there’s a good chance she’s late because she was off doing some good somewhere in the world.

Monte Burke is The New York Times bestselling author of Saban, 4th And Goal and Sowbelly. His new book, Lords of the Fly: Madness, Obsession, and the Hunt for the World-Record Tarpon, is available now. He is a contributing editor at Forbes and Garden & Gun

Meadows of green turtle grass sway peacefully in the current beside patches of bright white sand, where tiny crabs and shrimp forage, nearly invisible to the untrained eye. Several slowly moving Vs suggest the approach of a school of bonefish. The flash of a black sickle-like tail at the deeper edge of the flat confirms the presence of a feeding permit.

For a passionate angler, it would be difficult to place too high a price upon such an intact, fecund flat; it’s what we live for. But for a bureaucrat hundreds of miles away, who probably doesn’t fish, and very likely has never set foot in such an ecosystem, it may have little intrinsic value. Can we build a housing development there? Can we mine precious metals there? Are there oil or natural gas reserves there? If not, it’s just another patch of sand and mangroves…and we have a gazillion hectares of that.

Enter the economic impact study.

Economic impact studies examine the impact of an activity on the economy of a specified area, measuring changes in

business revenue, wages and job growth. They can provide a tool for attributing a hard dollar value to a resource that might be otherwise difficult to quantify.

“Economic impact studies do several things for a conservation group like BTT,” said Dr. Aaron Adams, BTT’s Director of Science and Conservation. “First they provide leverage for conservation proposals that call for improved management of a resource. Historically, the well-being of flats species like tarpon, bonefish and permit—and their habitat—were not part of the management discussion. We’ve always had to build the case from a scientific perspective. We’ve learned that showing a fishery’s economic value is also important. It’s ammunition for governing bodies to justify more conservation-oriented management actions.

“The other benefit I see in economic impact studies is that they engage a region’s fishing community and encourage members to think about conservation. For most people—especially the guides—this is the first time that a value has been placed upon

their fishery. They start to see that the habitat has economic worth, and they can share this insight with their fellow citizens. When the whole community is engaged, there’s a better chance of pushing for better regulations to protect the resource.”

Economic studies in Florida, the Bahamas, and Belize have provided leverage for improved conservation measures. In Florida, studies have increased the profile of flats species and the connection to habitat quality and helped enact spawning season closures; in the Bahamas, they helped provide momentum for establishing additional national parks to provide protection for bonefish habitat; in Belize, they encouraged the enactment of catch-and-release regulations for tarpon, bonefish and permit.

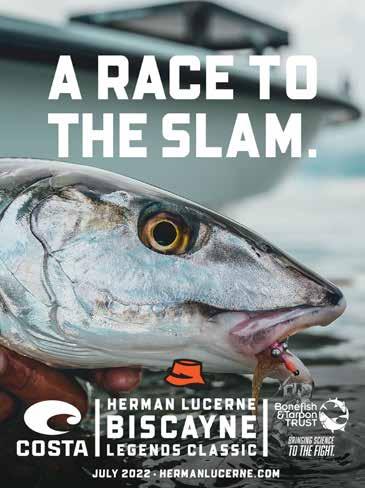

It’s hoped that a recently completed economic impact statement will have the same positive impact on the flats fishery of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The report was produced by Dr. Addiel Perez, BTT’s Belize-Mexico Program Coordinator, and Dr. Leopoldo Palomares, the Secretary of Sustainable Fisheries and

Aquaculture in Yucatán, Mexico. The research revealed direct angler expenditures of nearly $20 million; the value-added effects of these expenditures (economic activity that supports flat fishing) totaled $25.2 million, resulting in a total economic impact of $45.2 million (USD) in 2019, supporting approximately 1,674 jobs.

“When you think about recreational fishing in Mexico, there are many types of fisheries,” Dr. Perez explained. “Unfortunately, many continue to be unregulated, and receive little attention from a conservation/management perspective. There are very few NGOs (non-governmental organizations) in Mexico; nor are there many resource managers. Concerns associated with recreational fisheries are not being addressed. And because of that, there’s a lack of information regarding the socio-economic relevance of recreational fishing.” This report will help address that missing element.

procedure requires obtaining information on fishing activities directly from the guides and managers of flats fishing lodges in the various coastal communities where it is promoted,” Dr. Palomares said. “Our objective was to obtain a robust estimate of the number of anglers and the expenses generated by their visits to the country. In this way, the direct economic impact would be obtained, to which the indirect and induced effects should be added as a multiplying factor that the activity generates in the local economy.”

The study began in March of 2020, only to be postponed by the COVID-19 pandemic. “We were able to begin conducting interviews again in March of 2021, and completed them by the end of April,” Dr. Perez said. “We spoke to guides as well as lodge

managers and owners in flats fishing communities, from Holbox in the north to Xcalak at the southern end of the peninsula. We interviewed at least 40 people, and combined the information that we collected with some previous reports that had been commissioned.” Perez noted that the most robust communities for flats fishing are concentrated around Ascension and Espiritu Santo bays. “These areas are less developed,” he added, “and have healthy habitat…and thus, more abundant fish.”

Few have done more to bring the gospel of flats fly-fishing to the coastal communities of Quintana Roo than Alejandro Vega, better known as “Sandflea.” Born on the island of Holbox, he was initially exposed to fly-fishing by an uncle on Cozumel who guided. Largely self-taught, Sandflea has mentored hundreds of guides up and down Mexico’s Caribbean coast.

“I taught fly-fishing to people on Holbox, down in Ascension Bay, Mahahual, and Xcalak,” he shared. “Many of the men who became fly-fishing guides were commercial fishermen. I’d tell them, ‘You catch and kill so many pounds of snook or whatever in a day, and get paid for what you catch. Eventually, there’s less fish to catch. Sportfishing is catch-and-release. It’s better for the fish. And you can make more money doing this.’ When I started, 100 percent of the men on Holbox were commercial fishermen; now 50 percent are fly-fishing guides.” (Today, Sandflea operates Holbox Tarpon Club.)

“Flats fishing is a very important source of income in coastal communities in the Yucatán,” Dr. Perez added. “People once relied on small-scale commercial fishing, but because of an increased number of fishers and the high demand on fisheries as a food source related to the population increase, there’s been a decrease in fish abundance. Flats fishing can make up for the lost income. Thanks to catch-and-release fishing, there will be more fish abundance. They’ll always have that income.”

In some communities, Drs. Perez and Palomares found that lodges are weighing the pros and cons of increasing angler

capacity. “From a business perspective, it may seem to make sense to expand,” Dr. Perez said. “But they need to evaluate how increased pressure will impact the sustainability and quality of the fishery, and if it’s worth the short-term profits.”

Now that the economic impact study has been completed, what are the best possible outcomes for the Yucatán flats fisheries? Dr. Palomares outlined a few. “The first step would be to establish the flats fishing areas as fishing refuge zones, where only recreational catch-and-release fishing could be allowed. This would allow authorities to better monitor illegal fishing, like the use of nets in the mangroves and estuarine channels, which catch all types of species. It will also be important to recognize permit, bonefish and snook as exclusive species for recreational fishing under the recreational fishing regulations (NOM-017-PESC-1994). Currently, only tarpon have this recognition, which means that their commercial capture is not allowed. But an angler can still keep or kill a tarpon with a sport fishing license; Dr. Perez says the regulation needs to be revised as catch-and-release only. Given that the value of catch-and-release is greater than the income for consumption of these species, it would be feasible to consider better management for their sustainable use. Additionally, carrying capacity limits should be established for recreational boats to ensure the quality of fishing. I’d also love to see the guides become more organized so they can become certified as fly-fishing guides. This would encourage more professionalism, while involving them in management decisions together with administrators.”

Dr. Palomares is optimistic about the future of flats fishing in Quintana Roo—and the communities that rely upon it as an economic driver. “In all the places we visited, the guides are aware of the importance of taking care of the natural capital of

their resources. They are proud to carry out a sustainable activity, and to be recognized for their skills by visiting anglers. This social capital is the most important thing that the guides offer and encourages guests to choose Quintana Roo as a destination for fly-fishing the flats.”

Chris Santella is the author of 21 books, including the popular “Fifty Places” series from Abrams. He’s a regular contributor to The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Trout

Bob Bailey was the very definition of a crusty, old salt. When my dad and I would buy shrimp at Bailey’s Fish Camp on the north end of Sabine Lake, he would always tell us the same thing.

“I don’t know what in the world you’re buying bait for. The fish aren’t biting.”

One day, however, he had something else on his mind.

“I’m going to show you something, kid. It’s going to blow your mind,” Bailey said.

He took us over to a huge, old chest freezer tucked in the back of his shop.

“Go ahead little Chester, open it up,” Bailey said.

At first, I wasn’t sure if he was pulling some prank but curiosity got the best of the 10-year-old me.

Inside was a seven-foot-long tarpon.

My mind was blown. I had a poster of Texas coastal fish in my room with a tarpon on it and marveled at them in fishing magazines but had never seen the Silver King up close.

“A guy caught it by the 18-mile light out on the Sabine Bank

last week. He’s keeping it here until he finds a taxidermist who can mount it. When I was younger, we had tarpon all over the place around here and then they disappeared. This is the first one I’ve seen in years,” Bailey said.

I left that day inspired by actually getting to see a tarpon in the wild and curious as to why these great fish vanished from my home waters.

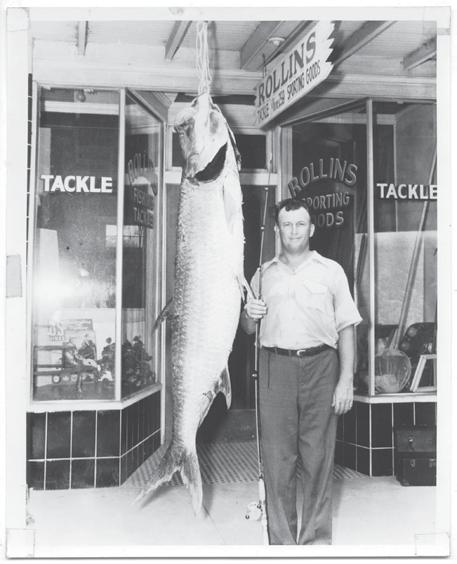

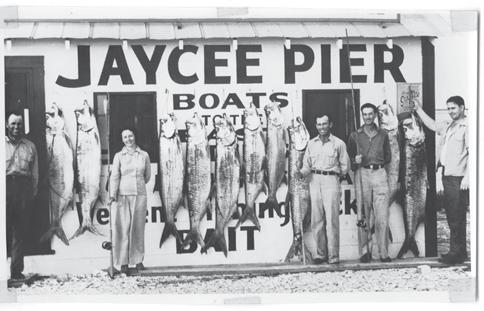

Tarpon such as this 136-pounder can be caught by anglers leaving the Pleasure Pier for offshore fishing mid-1930s.

Those words are scribbled on the back of a photo of a man with a large tarpon hanging from a rope. On display at the Museum of the Gulf Coast in Port Arthur, TX, the photo and a few newspaper references to tarpon tournaments during that era are the last reminders of any viable fishery for the species there.

Then there’s Tarpon, TX.

Known as Port Aransas for the last 100 years, it was named for the main economic driver for the island city. Beginning in the

late 1880s, thousands poured into the area to catch tarpon, and for years huge crowds gathered to witness the annual “Tarpon Rodeo” tournament.

Similar accounts are found in Port O’Connor, Freeport, and other areas along Texas’s 367 miles of Gulf shoreline that borders both Louisiana and Mexico.

Officials with the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department link the decline to the damming of rivers, droughts, pesticides, and past overfishing. And while the fishery may have markedly declined, there has always been a silver lining in certain areas.

Longtime Port Mansfield guide and lodge owner Capt. Bruce Shuler said there were always some anglers that figured out where to find tarpon and how to catch them.

“We did pretty well on them in certain years at the Port Mansfield jetties,” Shuler said.

“It always seemed that there would be really good years and then some not-so-good years. And there were always people who were on top of finding and catching tarpon, even after the big decline.”

“Tarpon Alley,” an area two to four miles from the beach between High Island and Galveston Island, produces good catches annually. South Padre Island is arguably the state’s most consistent fishery with Port Mansfield and Port O’Connor jetties both producing quality fish.

What anglers, guides, and Bonefish & Tarpon Trust researchers want to know is what is going on with Texas’ tarpon fishery now and how we can better manage it so what exists doesn’t fade away like the fisheries of the past.

Designed to broaden the understanding of tarpon movement and habitat uses, BTT’s Tarpon Acoustic Tagging Project began as a collaborative program of the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust (BTT) and University of Massachusetts Amherst focusing on the southeastern US and eastern Gulf of Mexico, before expanding to Texas in collaboration with Texas A&M University.

The broad goal for the tarpon tracking project is to understand tarpon movements and habitat use enough to guide management

and conservation. The partner leading the effort in the western Gulf is the Fisheries Ecology Lab & Department of Marine Biology at Texas A&M University at Galveston.

BTT Research Fellow Dr. Andy Danylchuk and BTT Collaborating Scientist Dr. Lucas Griffin lead the project and have written extensively on its mechanics. The innovative technology it employs involves stationary acoustic receivers or “listening stations” moored on the seafloor.

“These receivers detect the signals from acoustic tags that we surgically implant into tarpon. The transmitters are the size of an AA battery and have a lifespan of five years,” said Griffin. “This means not only can we implant them in a wide size range of tarpon, including those around 15 pounds, we can also track them over multiple years. As the tarpon swims past the network of receivers, a unique ID code, date, and time are saved on the receiver.”