March 10, 2025

Dear Opera-Curious and Opera Lovers alike,

Boston Lyric Opera is thrilled to welcome you to the Emerson Colonial Theatre for the 80th anniversary production of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Carousel Opera has a way of tapping into big emotions in a way that’s hard to describe. There’s something incredibly powerful about experiencing the human voice live in the theater, and I believe that whether you’re new to opera or have loved it for years, there’s always something new to discover. To help make your experience even richer, we’ve put together this Guide. It’s designed to give you a little background on Carousel and its themes, as well as some plot details (spoiler alert!). Our intent is to provide support in historical and contemporary context, along with tools to thoughtfully reflect on the opera before or after you attend.

Boston Lyric Opera inspires, entertains, and connects communities through compelling performances, programs, and gatherings. Our vision is to create operatic moments that enrich everyday life. As we develop additional Guides, we’re always eager to hear how we can improve your experience. Please tell us about how you use this Guide and how it can best serve your future learning and engagement needs by emailing education@blo.org.

If you’re interested in engaging with us further and learning about additional opera education opportunities with Boston Lyric Opera, please visit blo.org/ education to discover our programs and initiatives. We can’t wait to share this experience with you.

Warmly,

Nina Yoshida Nelsen

Artistic Director

Act 1 opens with Julie Jordan and Carrie Pipperidge getting run off the town’s carousel by Mrs. Mullin, the widowed proprietress of Mullin’s Carousel, after she spies Billy Bigelow putting his arm around Julie's waist. Billy follows them and, after defending Julie, gets fired from his job as a carousel barker. Billy leaves to collect his belongings and instructs Julie to wait for him, inviting her for a drink. Carrie begins to tease Julie to share her feelings about Billy, and Carrie reveals that she’s in love with the fisherman, Enoch Snow.

Billy returns with his things and Julie says goodnight to Carrie. Their conversation is interrupted by the owner of the mill, Mr. Bascombe, and a police officer. Mr. Bascombe questions why Julie is out so late and remarks that she’ll never make it back to the mill’s boarding house by curfew. Mr. Bascombe says he’ll escort Julie back to the boarding house, but Julie chooses to stay with Billy. Meanwhile, the police officer threatens to throw Billy in jail, but without any reason to arrest Billy, the officer leaves.

Continuing their conversation, Billy asks Julie if she’s scared of him. She replies that she isn’t. Billy asks if she would like to go into town for a dance, and Julie responds that she can’t because she has to look out for her character. The burgeoning couple discusses what it would be like if they loved each other, without outright admitting their growing feelings for one another.

Time goes by. Julie and Billy have gotten married, and are living with Julie’s relative, Nettie Fowler. Nettie and the other women of the town are preparing for a community clambake. Julie meets with Carrie and the two catch up. Julie confesses that Billy has been out all night with Jigger Craigin and that Billy hit her. In an attempt to cheer Julie up, Carrie shares the happier news that she and Enoch Snow are engaged and will be married the following Sunday. Enoch joins the two women, and Carrie formally introduces him to Julie. Shortly after, Billy and Jigger appear, and Billy makes rude remarks to Enoch and Julie. Billy announces that he won’t attend the clambake that evening and leaves with a distressed Julie following him. Left alone, Enoch and Carrie imagine their future together.

Meanwhile, Jigger proposes a risky plan to Billy. Jigger suggests that Billy join him in jumping Mr. Bascombe when he’s delivering cash to the whaling boat captain. Billy declines and runs into Mrs. Mullin, who offers Billy his former position as carousel barker if he leaves Julie.

Julie comes to Billy with good news – she’s pregnant and they’re to have their first child together. Excited, Billy helps Julie back to the house and decides to turn down Mrs. Mullin’s offer. He imagines being father to "Bill, Jr." when it hits him that the child may be a girl. He reflects that although he doesn't know how to be a father to a girl, he's willing to do anything for her. Still unemployed, Billy decides to accept Jigger’s proposal. He confirms his attendance at the clambake with Nettie and Julie, thus confirming his alibi.

After the clambake, the town is happy and well-fed. Nettie leads the cleanup effort while Enoch leaves to hide the treasure for the customary post-clambake treasure hunt. Jigger and Billy, the latter now armed with a knife, head towards the waterfront for their heist. Jigger becomes distracted and attempts to seduce Carrie. He begs her for a kiss, and says he worries about Carrie’s innocence. Enoch reenters, and after witnessing the interaction, angrily breaks off his and Carrie’s engagement. Jigger unsuccessfully attempts to comfort Carrie, who leaves to try and fix her relationship with Enoch.

The treasure hunt begins, and Julie catches Billy trying to sneak off with Jigger. Afterward, she and the other women try to comfort Carrie about her situation. During a second encounter with Billy and Jigger that evening, Julie realizes that Billy has a knife. She begs him to give it to her, but Billy pushes Julie away and leaves with Jigger. Julie is left alone to reflect on her marriage.

Billy and Jigger wait by the loading docks for Mr. Bascombe. They discuss God and eventually decide to play cards while they wait. Mr. Bascombe arrives, and a fight breaks out. Mr. Bascombe takes the knife from Jigger and pulls a gun on the two men, calling for help from nearby ships

while Jigger flees. When the police appear, Billy decides to take drastic action. Rather than go to prison, he stabs himself in the stomach and ultimately dies in Julie’s arms. Julie is understandably distraught. Nettie tells Julie she can stay with her and that she’ll help raise the baby.

Two Heavenly Friends appear and take Billy’s soul to the Starkeeper. The Starkeeper, a heavenly judge, tells Billy that he has not lived a good enough life to enter Heaven. However, he reveals that if there is someone alive who remembers him, Billy can return for a day to redeem himself. He tells Billy that if he can help his daughter, Louise, then he can enter heaven. The Starkeeper allows Billy to see Louise, and he watches her travails as a young woman growing up, which motivates him to help her.

Billy decides to visit Earth as a ghostly-spirit figure and discovers Julie at a cottage catching up with Carrie. They’re heading to Louise and Enoch Junior’s graduation. Louise reveals to Enoch Jr. that she wants to run away and become an actress, and Enoch Jr. offers to marry her instead. Louise rejects the offer. Billy, having watched the exchange, trips Enoch Jr. as he leaves.

Billy goes to visit his now-teenage daughter. Now visible to her, Billy says that he is a friend of her father’s. Having seen Louise being bullied for being the daughter of a criminal, he tries to encourage her. He offers Louise a star he stole from the Starkeeper. She rejects the gift, and Billy – still unable to control his frustration and panic – slaps her hand. Louise runs inside and explains what happened to her mother. Julie finds the star Billy stole lying on the ground and feels his presence.

Billy, in one last effort to redeem himself, attends Louise’s graduation ceremony, invisible. At the ceremony, the town’s physician, Dr. Seldon (who strangely resembles the Starkeeper) gives an inspirational speech to the graduates to not be defined by their parents’ successes and failures. Billy whispers to Louise to truly listen and believe Dr. Seldon’s speech. Finally, Billy goes to Julie and tells her he loves her. Having professed his love for his wife, Billy departs, having now earned his place in Heaven.

Julie Jordan, soprano, a millworker

Billy Bigelow, baritone, a carousel barker

Carrie Pipperidge, soprano, a millworker and Julie’s friend

Enoch Snow, tenor, a fisherman

Nettie Fowler, mezzo-soprano, Julie’s cousin

Jigger Craigin, baritone, a whaler

The Starkeeper, a Heavenly official

Mrs. Mullin, the owner of the carousel

David Bascombe, the owner of the mill

Dr. Seldon, the town’s physician

Louise Bigelow, Billy and Julie’s daughter

Enoch Snow, Jr., Carrie and Enoch’s son

Staging a new or relatively unknown theatrical work differs significantly from reviving a beloved classic that has achieved chestnut status. When Bradley Vernatter, the General Director & CEO of Boston Lyric Opera, approached me about directing Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s Carousel for the company, I responded with immediate and wholehearted enthusiasm. Chestnut!

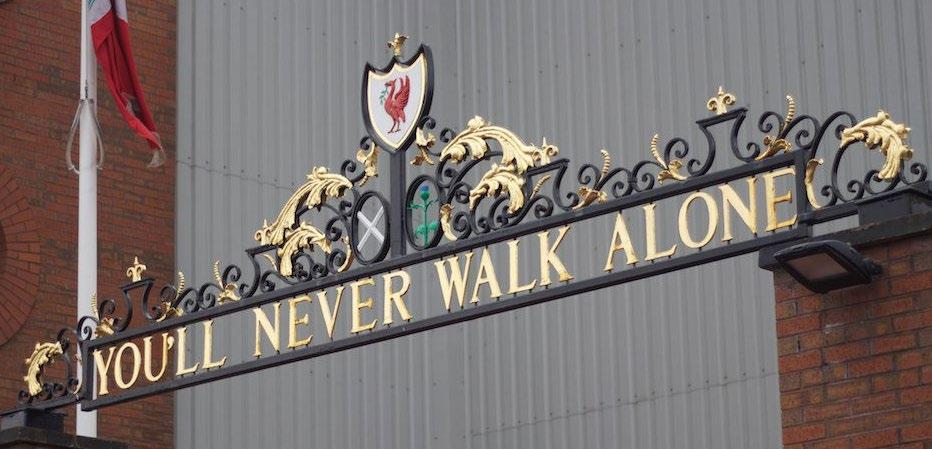

The appeal of Carousel extends far beyond its powerful music and compelling narrative. It is a production that resonates deeply with audiences, evoking personal connections and cherished memories. Upon mentioning my involvement with the show, I am invariably met with a flood of personal anecdotes and spontaneous musical recollections. Some people share stories of their own high school performances, while others recount transformative experiences of watching the show at pivotal moments in their lives. The music of Carousel, particularly “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” has transcended its theatrical origins to become a cultural phenomenon. The song has been adopted by several football clubs, most notably Liverpool, where the tradition of singing the song before every home game has become an iconic part of football culture. In some areas of the United Kingdom and Europe the song became the anthem of support for medical staff, first responders, and those in quarantine during the Covid-19 pandemic. This universal response underscores Carousel’s enduring impact and its status as a true theatrical chestnut. The musical has woven itself into the fabric of cultural memory, with its songs and themes that continue to evoke strong emotional responses decades after its 1945 Broadway premiere.

A chestnut in theater is more than just a play; it is a cultural artifact steeped in its own rich history. When staging such a well-known work, directors and actors face a unique set of challenges that go beyond the typical demands of production. Firstly, the audience does not arrive as a blank slate. They bring with them a tapestry of memories, expectations, and preconceptions woven from previous encounters with the work. These might be personal experiences, iconic interpretations they have seen, or simply the play’s reputation in popular culture. This collective memory creates an invisible but palpable presence in the theater, one that the production must acknowledge and engage with.

The word chestnut carries with it negative connotations such as hackneyed or overused, or a story that has been repeated so often that it has become stale, trite, or uninteresting. James Parker, a staff writer at the Atlantic Magazine cited the example of the infamous poems of Robert Frost,

including “The Road Not Taken,” or “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” These, he says, are not really poems anymore. Decades of mass exposure have done something to them, inverted their aura. He said that they are now more like “recipes, or in-flight safety announcements.” Moreover, chestnuts often come with specific moments or lines that have transcended the play itself to become cultural touchstones. Think of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy – these words carry a weight far beyond their role in the play’s narrative. They have become part of our shared cultural language, referenced and parodied countless times across various media. To stage a production of Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire, which has over time become a chestnut, where do you put Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Stanley? What do you do with the expectations that audiences bring with them about how Stanley should look and sound? Do you pretend that Marlon Brando never played Stanley?

In staging a chestnut, the creative team must walk a delicate tightrope. On one side is the pull of tradition – the desire to honor the work’s history and meet audience expectations. On the other is the drive for innovation – the need to breathe new life into the familiar and make it resonate with contemporary audiences. This tension between reverence and reinvention is at the heart of staging a chestnut.

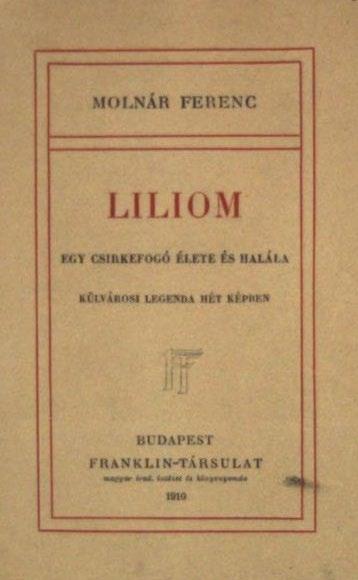

With a chestnut, it is useful to consider the zeitgeist of the moment of a play’s premiere and compare it to that of the current moment. In 1945, the year of Carousel’s premiere, the United States was engaged in a massive war both in Europe and the Pacific. Young men were returning home with what we now might call PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). The character Billy Bigelow may have been an example of such a young man – violent and lost and full of unexplored aggressions. Imagine how “You’ll Never Walk Alone” was received by audiences in 1945, many of whom were struggling, picking up the pieces of the war. Children were being raised in fatherless homes. A lot of these were encapsulated by the characters Julie and Louise. Rodgers and Hammerstein connected the source material of Liliom, the Hungarian play upon which the musical is based, and what audiences required in 1945. Billy has serious issues, but the play’s ultimate messages of hope, breaking cycles of trauma, and working towards a promising future are still meaningful and potent.

How has Carousel evolved in meaning and interpretation over time as society changes? In 2025, connecting its themes to contemporary issues and audiences requires a nuanced approach that goes beyond simply recreating the original production. Perhaps the key question to ask is not “How do we recreate the original?” but rather, “Who needs to perform this play now and who needs to hear it?” This opens new possibilities for interpretation and relevance. When Carousel first premiered in 1945, it was groundbreaking for its sophisticated integration of music and drama. The musical tackled darker themes than previous musicals, exploring complex characters

and relationships. However, over time, certain aspects of the story have become contentious, particularly its handling of domestic violence and abuse. The key is to balance respect for the original work with the need to address its problematic elements. By doing so, Carousel can continue to evolve, offering insights into human nature and societal issues that remain relevant 80 years after its premiere.

Our Carousel is happening in the same theater as its final out-of-town tryout in 1945. This leads to intriguing questions about the presence of the past and about how memories and patterns might be stored and transmitted across time and space. Do physical spaces like theaters hold memories of past performances? Do the ghosts of the performers who originally played those roles lurk nearby? Do buildings store memories? The scientist Rupert Sheldrake proposed that there is a collective memory inherent in nature, allowing similar patterns to influence subsequent ones from across time and space. He calls this phenomenon morphic resonance. His theory offers an intriguing perspective on the idea of “ghosts of past performances” in theater buildings. Morphic resonance suggests that the building itself might “remember” past performances, creating a resonant field that new productions and audiences unconsciously tap into. Sheldrake is a controversial figure in the scientific community, and his theories remain debated. But they do provoke a framework for speculation about how past performances might subtly influence current productions in each theater space, creating a unique atmosphere or energy.

In essence, directing a theatrical chestnut is not just about putting on a play. It is about entering into a dialogue with history, audience expectations, and the cultural significance that the work has accrued over time. It is a complex dance between the past and the present, between the familiar and the fresh. But by reframing chestnuts as valuable cultural artifacts rather than tired cliches, we open new possibilities for interpretation, connection, and relevance. I see them as repositories of collective memory and shared cultural experiences. This shift in perspective invites us to appreciate the depth and richness that comes with works that have stood the test of time.

Ultimately, my interest in Carousel is not simply to the answer to the question “who needs to perform this play now and who needs to hear it?” The aim is to tap into the power of the original without altering its content. We are not changing or eliminating any of the words or music. In our version of Carousel, a group of refugees arrive from a great distance to perform the play, seeking to gain access and acceptance. The show’s exploration of forgiveness and community aligns with the refugees’ quest for acceptance. As the performance unfolds, it is my hope that the original power and alchemy of Carousel takes hold. Through this process, two separate communities, that of the audience and that of the performers, may transform into one, united in the intrinsic power of the piece.

by Kira Troilo

When you think of Carousel by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, what immediately comes to mind? If you grew up in an earlier generation, chances are that what lingers in your memory are the soaring musical themes, the majesty of the score, the joy of “June Is Bustin’ Out All Over,” and the emotional pull of the anthem “You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

If you identify with that generation, you may not even know much about Carousel beyond its music. Songs like “You’ll Never Walk Alone” have taken on a life of their own beyond the musical. “You’ll Never Walk Alone” has had a significant life beyond Carousel, becoming an anthem of hope and solidarity across various contexts. The song was famously adopted by Liverpool Football Club in the 1960s after a cover by the British band Gerry and the Pacemakers topped the UK charts. Since then, it has been sung at every home game at Anfield, becoming a powerful symbol of unity and perseverance in the world of sports.

Beyond football, the song has been used as an anthem of resilience in times of crisis. It was frequently played during the COVID-19 pandemic as a message of support for frontline workers and those struggling with isolation. “You’ll Never Walk Alone” endures as a song that transcends its origins in Carousel, offering comfort and inspiration in difficult times.

I think personally of a post-show panel I moderated for a recent production of Oklahoma, another iconic (though problematic in 2025) Rodgers & Hammerstein show. I called on a gentleman in the audience who shared the story of how he sat in the Broadway theater to see the original production of Oklahoma in 1943. Experiencing the show again in 2024 was emotional for him and brought him enormous comfort.

On the flip side, if you’re a millennial or Gen Z who grew up in the age of social media, you likely bring more critical awareness to Carousel. You weren’t around in 1945 when Carousel premiered to post-war audiences seeking uplifting messages from the stories and music they consumed. These younger generations don't often come to the Golden Age musical with rose-colored glasses on. A rousing anthem isn't enough to negate the uglier, often underexamined aspects of these stories.

Whenever a Golden Age musical like Carousel is presented today, it must (rightfully) face contemporary scrutiny. Why should we continue to stage Carousel? Why now, in 2025, when the world is navigating a post-pandemic cultural shift, global political instability, climate crises, and an ongoing fight for social justice? The arts are being challenged to reflect these turbulent times, with theater audiences more attuned than ever to issues of representation, power dynamics, and historical accuracy. Is Carousel, a show from 1945 about 1870s Maine, the story we should be telling right now? Or does the show belong in the past, an artifact from a time long gone?

And what happens when we apply modern values in live theater and opera to shows like Carousel? What happens when we cast a racially diverse company, feature artists with gender identities outside the binary, and incorporate contemporary perspectives on abuse and power?

These are the questions I helped Boston Lyric Opera (BLO) and director Anne Bogart navigate during pre-production for Carousel. These discussions are crucial before actors step into an operatic relic and attempt to make it relevant to today’s audiences.

Let’s start with Carousel's most obviously problematic aspect: not just Billy Bigelow’s physical abuse of the timid Julie Jordan, but his ultimate redemption — and the troubling lines spoken by Julie and their daughter at the end of the show.

“Has it ever happened to you? Has anyone ever hit you — without hurtin’?”

“It is possible, dear,” Julie responds, “for someone to hit you — hit you hard — and not hurt at all.”

Researching Carousel led us to its reference material: the play Liliom. In Liliom, Billy’s counterpart meets a different, arguably more fitting fate. After his death, he is sentenced to 16 years in purgatory. Given a chance at redemption, he visits his teenage daughter — but when he abuses her as he did his wife, he is condemned to hell. Liliom is a clear tragedy, its title character an unmistakable cautionary tale.

Rodgers and Hammerstein softened the ending. Carousel was crafted for 1945 audiences who wanted comfort, escape, and redemption — not a moral reckoning. (Imagine “You’ll Never Walk Alone” being sung as Billy is relegated to the fiery pits of hell.) After all, many families were left wondering if there could be redemption for the sons that never came home, or who came home traumatized and changed in 1945.

Like many adaptations, Carousel wrestles with its source material in ways that create inconsistencies. The ending — with its soaring anthem and Billy’s implied ascension — feels redemptive. But does Billy deserve redemption when his only atonement is whispering a few words to his daughter at her graduation?

Billy’s actions are undeniably ugly, as is the generational trauma that courses through the story. But domestic abuse is not a relic of the past. In the U.S., approximately 24 people per minute (yes, per minute) experience intimate partner violence — over 12 million individuals annually. One in four women and one in nine men endure such violence in their lifetimes.

I prefer stories where women rise up against domestic abuse. I prefer Sofia’s “Hell No!” from The Color Purple to Julie Jordan’s final takeaway in Carousel. But reality is complicated. If domestic abuse were simple, no one would remain in an abusive relationship. The statistics would tell a different story.

Love is not always perfect. Love often exists even when it is undeserved.

For me, Julie and Louise’s final lines are deeply sad. They do not glorify or excuse abuse; they reflect the lived experience of many survivors. The words should not uplift; but they may, for some of those 12 million annual victims, ring true.

As an industry, I think we’ve gotten the memo about representation — it matters, big time. And it is also crucial to examine and grapple with what happens when we cast people of color in roles that were originally intended for — and traditionally played by — white people. What happens to the story, for example, when you have a Black Julie Jordan in a story that’s set in the 1870s in Maine — the Jim Crow era — a time when there weren’t very many Black people in Maine (though there were some! About 300, according to Maine Memory Network).

The time for “color-blind” casting is over. We can no longer pretend that we “just don’t see color.” We do see color, and that’s a beautiful thing. Skin color is one of many characteristics that makes each person who they are. We should not ask actors or audiences to ignore something so wonderfully present. But how do we present Golden Age musicals in a way that reflects the diversity of

cities of Boston in 2025, while also telling stories that most certainly did not consider people other than white actors stepping into roles like Billy Bigelow or Julie Jordan?

The latest Broadway revival of Carousel asked the question of what would happen if a Black man played Billy Bigelow. The reviews were scattered, and opinions varied. But many thought it troubling to ask a Black man to step into the shoes of Billy Bigelow, an abusive bully. For BLO’s production, the racial diversity is flipped. While Billy is portrayed by a white actor, our Julie is Black.

This, in a contemporary context, immediately makes the storytelling more complicated. Today, for example, Black women experience violence at a rate of 2.5 times more than white women. And while the #MeToo movement was co-opted by white women, it actually started with Black women (one woman in particular — Tarana Burke).

What does it do to the storytelling to ask contemporary Black folks to step into traditionally white roles? What does it do for audiences of color to see representation onstage while also grappling with the plausibility of the storytelling?

These are questions I grapple with as an Inclusion Consultant: how do we care for and support artists in these complicated, identity-driven circumstances? As a production, BLO’s Carousel has taken actor identities into account in order to tell the story in 2025 Boston. To create responsible art, we must consider the context.

Presenting art does not mean agreeing with it. And art isn’t always a statement. In my opinion, the best art asks questions. We all bring different truths, different identities, to any art we consume — so the answers are always different to each individual.

Through my work with BLO in the lead-up to Carousel rehearsals, I’ve encouraged the team to lean into the question rather than forcing a statement. The big question is one we’ve been grappling with, especially in the last five years. Is there a place for the Golden Age musical in contemporary times? Can Carousel work now?

That is a question asked by BLO, by director Anne Bogart, by the design team, and by the cast performing the show — by this production as a whole. As a team, we have a responsibility to think critically, to care for artists who step boldly into roles that weren’t meant for them, and to provide resources to those who may struggle with the uglier themes in the show. And after all of that, we tell the story; and in so doing, ask the question. In BLO’s production, you’ll see the artists ask the question in a very literal way, and the audiences will be asked to respond. I imagine everyone involved will continue to grapple with the answer long after the curtain falls.

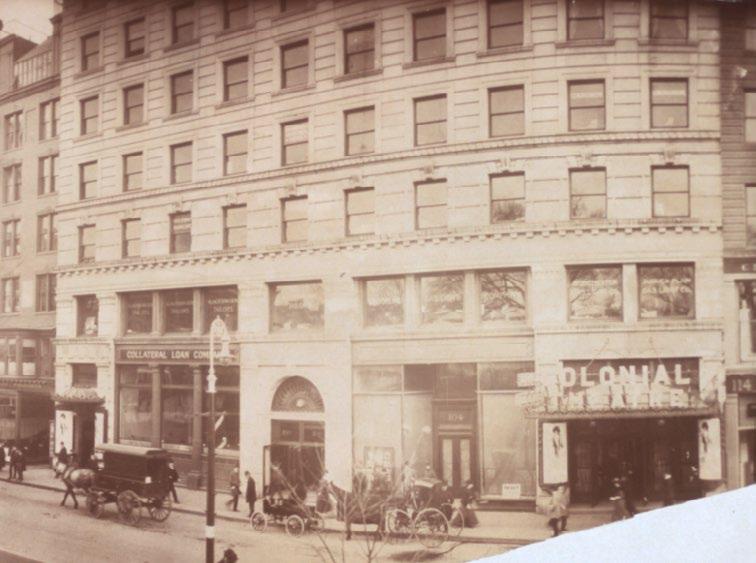

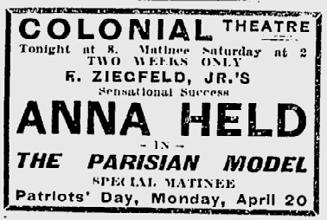

Boston is known around the US as a city with a rich and vibrant history – from the role it played during the American Revolution, to the storied halls of the city’s numerous academic institutions, to its nickname as “The City of Champions.” But even Bostonians may be surprised to learn that Boston was also where many Golden Age musicals hosted their pre-Broadway debuts. Boston has long been regarded as a popular “try-out town” for theatrical productions looking to make it to Broadway. In fact, as reported by the Boston Globe, “the city’s supporting role as one of the top pre-Broadway tryout towns in the nation was so vital that composer Richard Rodgers, of Rodgers & Hammerstein fame, used to say he wouldn’t open a can of tomatoes without first bringing it to Boston.”1 At the center of this rich theatrical history is The Emerson Colonial Theatre, the venue for Boston Lyric Opera’s 2025 production of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Carousel.

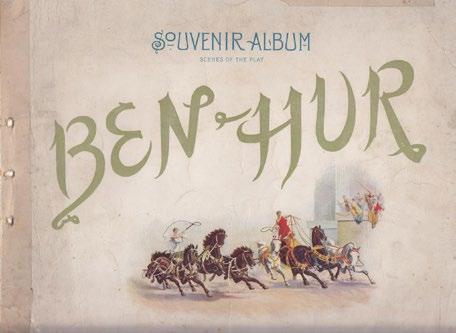

The Colonial, designed by architect Clarence H. Blackall and designer Henry Barrett Pennell, first opened on December 20th, 1900 with a production of Ben-Hur. This opening production had a cast of 350 people as well as 8 live horses – in fact, the original stables can still be found backstage, and there are plans to convert them to increase backstage accessibility. After operating for over 100 years, the theatre was purchased by Emerson College in 2006 and subsequently closed in 2015 due to a decrease in touring productions. The college initially had plans to convert the theatre into a student center and dining hall, but after much outcry from Emerson alumni, art- and history-loving Boston residents, and theatre makers across the US – including famed composer Stephen Sondheim – it was eventually purchased by the Ambassador Theatre Group. The Colonial remained closed for three years, during which its original architectural charm was revitalized and refurbished, eventually opening again in 2018 with the premiere of the stage version of Baz Luhrmann's Moulin Rouge!

Now in its 125th year, The Colonial is considered the oldest operating theatre in the City of Boston. The Colonial has hosted many openings, most notably Anything Goes, Porgy and Bess, Oklahoma!, Follies, A Little Night Music, and La Cage aux Folles. A spokesperson for the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization said to Playbill of The Colonial, Away We Go! arrived at the Colonial in March '43 and it was on the theatre's fabled gilt lobby grand staircase that the cast assembled to hear a new choral version of a song going into the show that week. The song was called 'Oklahoma,' and became a show-stopper at the Colonial, and a title song by the time Oklahoma! opened at the St. James on Broadway at the end of March.”2

The Colonial holds so many memories for the artists who have had the honor of performing on its stage. Don Scardino, who premiered the role of Johnny Parkins in the 1978 production of King of Hearts, recalls the magic of The Colonial:

For all its size, the Colonial feels intimate and close. I felt like I could reach out and touch every single person in the audience, even in the balconies. The energy, the aura of the place, was palpable and it embraced our show and placed it like a shiny little jewel in a box full of the most radiant gemstones. I felt wrapped in the warm arms of the audience, and there was a connection that is unmatched in other houses. I know in my heart that it was the Colonial itself, with all its grand performances and thrilling memories still alive, that made our show feel so wonderful. Can a theatre, a building, hold a special magic? Are the ghosts of all those evenings, the players and audiences connected by thrilling theatrical art, still vibrating in that space, even now? I believe so and I know I felt it every night I played the Colonial. It was then, and is now, pure Heaven on Earth. 3

One of the most notable out-of-town tryouts was Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Carousel. This work was the celebrated duo’s second collaboration together after the success of Oklahoma! (previously titled Away We Go!). The idea was pitched by Rodgers & Hammerstein’s producers, New York's Theatre Guild’s Theresa Helburn and Lawrence Langner, who suggested adapting the 1909 Hungarian play Liliom by Ferenc Molnár.

Operatic Connections: Renowned Italian composer Giacomo Puccini originally wanted to turn Liliom into an opera but was rejected by Ferenc Molnár. German composer Kurt Weill also sought adaptation rights and was also rejected.

After attending a performance of Oklahoma!, Molnár was convinced that Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein would honor his original play and, after lengthy negotiations, allowed the pair to change certain plot points.

These plot changes were crucial. While writing Carousel, Rodgers and Hammerstein struggled with many of the darker aspects of

Molnár’s play. Additionally, they struggled with making the plot relevant to American audiences – audiences who were still grappling with the daily household effects of World War II. To Americanize the Hungarian play, they attempted to set the musical in Louisiana instead of Budapest. However, after unsuccessfully attempting to write in a Creole dialect, Richard Rodgers suggested New England as the backdrop for their adaptation. Additionally, Rodgers and Hammerstein altered Molnár’s original ending. The ending of Liliom was deemed to be too dark for an American musical comedy and was reworked to give Billy Bigelow a redemption arc.

The Cutting Room Floor: One of the other notable changes made to Carousel between the Boston and Broadway premiere was to the character of The Starkeeper. Originally, this role was meant to be two roles, known as Mr. and Mrs. God, and they were designed based on a New England minister and his wife.

Carousel is considered the most operatic Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, even though it has no overture but instead an opening waltz. Due to its orchestration and the limited number of scenes with spoken dialogue, as well as the innovative use of dance, music, and character to progress the storytelling, it became a new standard for the American musical. In April 1945, Oscar Hammerstein wrote in the New York Times, “We knew we wouldn’t wind up with a conventional musical comedy. It was obvious that we would have to mix in values from the dramatic stage and opera.” 4 The music was written with classically trained singers in mind, and as Richard Rodgers wrote in his autobiography, “...to me, my [Carousel] score is more satisfying than anything I have ever written.” 5

On March 27, 1945, Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Carousel opened for the first time in Boston. Carousel's operatic return to The Colonial with Boston Lyric Opera marks 80 years of this American classic, and will be celebrated on March 27, 2025 with a gathering of Boston’s arts community for World Theatre Day at The Colonial for a sing-a-long. Just like in 1945, today’s Boston audiences will learn that they, too, will never walk alone.

Footnotes:

1. Aucoin, Don. “A Comeback Role for Boston’s Theater District?” The Boston Globe, July 14, 2018.

2. Jones, Kenneth. “Colonial Theatre in Boston, Birthplace of Follies, Oklahoma! and Porgy and Bess, Seeking Presenter.” Playbill, July 6, 2011.

3. Schneider, Robert. 2016. “Hal Prince, Stephen Sondheim and More Reflect on Their Early Out-of-Town Days.” Playbill, April 16, 2016.

4. Hammerstein, Oscar. “Turns on a Carousel: An Account of Adventures in Setting the Play ‘Liliom’ to Music.” The New York Times, April 15, 1945.

5. Rodgers, Richard. Musical stages: An autobiography. Cambridge, Mass: Da Capo Press, 2002.

Imagine: you’re sitting in a theater, the house lights just went down, the conductor has arrived, and the orchestra plays that first note. Perhaps a curtain rises, and you are treated to a brilliant whirlwind of music, dance, and drama. You could be at a musical. You could be at an opera. While there are particular elements unique to each art form, opera and musical theatre are more similar than you might think.

Both opera and musical theatre can trace their origins back to ancient Greek theatre. Opera is about 500 years old, originating roughly in the 1500s (for a more in-depth timeline of opera as an art form, check out the History of Opera Timeline in this study guide!), whereas musical theatre emerged around the late 19th century. One important stepping stone in the creation of musical theatre was the operetta.

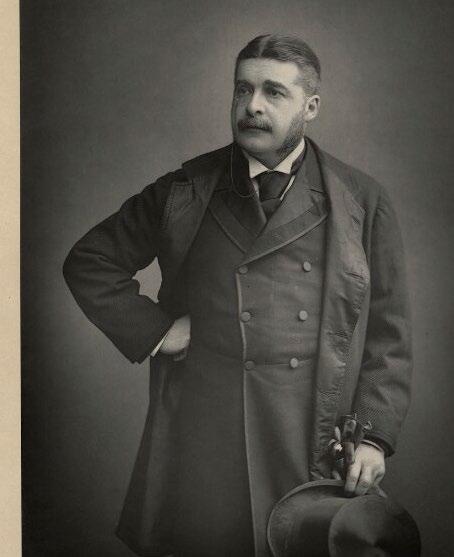

Operettas are “light” operas. But what does that really mean? Typically, operettas tend to be comedic or satirical, contain more spoken dialogue, have smaller orchestras, and are shorter. They became popular in 19th-century Europe thanks to composers like Jacques Offenbach, composer of Orpheus in the Underworld, and the composer/librettist duo W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, creators of H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance.

European immigrants, such as composers Victor Herbert, Rudolf Friml, and Sigmund Romberg, brought operetta to the United States, allowing it to blossom and evolve further. However, musical theatre was

not influenced exclusively by operas and operettas, but rather by a range of performance mediums. Musical theatre has been shaped by vaudeville, turn-of-the-20th-century Yiddish theatre, as well as jazz. All these elements lent themselves to what some consider the uniquely American art form of musical theatre.

Opera is defined by its vocal styling. Vocalists with aspirations of operatic performance diligently train and practice throughout their lives to be able to intimately control their instrument — their voice. The training is necessary — proper technique is what allows singers to healthily project their voice over an orchestra and to the back of the balcony. Opera singers are athletes and need to be able to engage their bodies appropriately in order to perform at such a high level.

While there is a wide range of operatic styles, there are some qualities in the voice that you’ll likely notice no matter what opera you’re attending. For instance, tall or modified vowels, resonant sound, and the use of vibrato all play a part in creating that signature “opera” sound. They aid in the creation of the undeniable gravitas of operatic singing.

To many, operatic performance feels worlds away from a modern musical theatre sound — and there are some notable differences. For starters, contemporary musical theatre singers, while they may have had

classical training, are usually miked while performing. But there’s also a difference in the sound of the voice. Many times, a “musical theatre style” will be described as “bright” or as a “character voice.” This is due to the singer’s placement of the voice, the shape of their vowels, and the incorporation of acting choices that don’t always prioritize a “beautiful sound.”

So how did this vocal styling change? An important step in the evolution from opera and operetta towards the modern musical theatre sound was a period of time called the Golden Age of Musical Theatre.

The Golden Age of Musical Theatre began in the mid-20th century. It was said to have been sparked by Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1943 collaboration, Oklahoma!, and lasted into the mid-1960s. The musicals written during this time forever influenced the trajectory of musical theatre and set the standard for what is considered an American musical. Golden Age musicals typically have archetypal characters, romantic themes, hummable melodies, big dance numbers, and happy endings – all characteristics commonly shared with operetta. The rise and success of Golden Age musicals was due to a major shift in American culture — the United States experienced an economic boom after World War II, and, coming out of the war, Americans were looking for escapism. Notable works that premiered during this time were The Sound of Music, Annie Get Your Gun, The Music Man, Guys and Dolls, My Fair Lady, West Side Story, and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel

Golden Age musicals are the key bridge between opera and contemporary musicals, in large part because they do not share the more pop-sounding vocal qualities of contemporary musicals. You may hear some musicologists say that Golden Age musicals feature “legit singing.” What they mean by this is that the quality of the sound is more like that of classically trained singers rather than the powerhouse belters we tend to hear on Broadway today. Similarly to operatic vocal stylings, Golden Age musicals favor the sound of tall, round, open vowels and the use of vibrato. And like in operetta, the sound in Golden Age musicals is lighter and there is an emphasis on the beauty of the phrasing.

Watch and compare these videos of two famed Broadway performers. The two performers, Julie Andrews and Shoshana Bean, both talented singers and actors, are a great example of the contrast between a Golden Age sound versus a contemporary sound.

It is from the Golden Age of Musical Theatre that musical theatre composers began to experiment with sound and style. During the 1960s, American culture shifted again, encompassing the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War protests, the rise of the counterculture movement, and the influence of rock music. These seismic cultural changes naturally shaped the art of the time, musical theatre and opera included. As the Golden Age of Musical Theatre ended, new musical traditions began, and their lineage can be traced back, in part, to opera. Even more directly, contemporary composers, librettists, and lyricists often combine elements from both opera and musical theatre in their work.

Watch this 1977 clip from the PBS program “Previn and the Pittsburgh,” where composer Stephen Sondheim discusses how he utilizes different aspects of opera and musical theatre in his writing.

Stephen Sondheim discusses Opera vs. Musical Theater (1977)

Opera and musical theatre will continue to influence each other as time goes on. These similar art forms have both captured the hearts of audiences and inspired new generations of artists. Artists from one genre will learn from the other and vice versa. Opera and musical theatre will forever be in conversation with one another and continue the centuries-old tradition of telling stories through music.

Carousel was a groundbreaking work for Rodgers & Hammerstein, following on the heels of their first big hit – Oklahoma! – but trying to deal with much more serious matters, and developing the music with some very long sequences. It was Richard Rodgers’ favourite work, and with good reason!

1 The opening prologue sets a nostalgic mood, with the famous waltz and the deliberately strange harmonics in the wind representing the fairground organ. Listen to the ghostly start and the way that it builds up momentum into the swirling waltz that many listeners know and love. My favourite recording is this 1994 revival, conducted by Eric Stern.

Carousel 1994 Revival - Prologue/The Carousel Waltz - YouTube

Just for fun, you might like to compare this to the faster dry performance – or a performance that’s inexpressive and inflexible, unemotional – conducted by the composer himself – very different!

Richard Rodgers - The Carousel Waltz

2

The most striking thing about Carousel, apart from its serious treatment of a very dark story, is the extended musical numbers which cover wide-ranging emotions and thoughts, none more so than “If I loved you.” Listen to how the music constantly changes character in the background during the spoken sections. This recording shows the performers from the 2018 revival in the recording studio – fascinating!

Joshua Henry and Jessie Mueller Perform 'If I Loved You' from Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel

3

4

Another extended number which covers many sudden changes of thought and direction is the “Soliloquy,” where Billy considers the implications of becoming a father. The music is so much more than just an accompaniment; it creates endlessly shifting moods and emotions.

Carousel 1994 Revival - Soliloquy

This show contained one great hit after another – songs like “June is bustin’ out all over” and “You’ll never walk alone,” for example, each of which would guarantee the success of the show. But my own little favourite is “What’s the use of wond’rin’?” with its exquisite harmonies and touching sentiment. Listen particularly to the background in the orchestra, especially the solo violin.

Carousel 1994 Revival - What's the Use of Wond'rin'

Musical Stages: An Autobiography by Richard Rodgers

The Sound of Their Music: The Story of Rodgers & Hammerstein by Frederick W. Nolan

Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein's Broadway Revolution by Todd S. Purdum

Round in Circles: The Story of Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel by Barry Kester

Articles

A Rodgers & Hammerstein Timeline

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel, After #MeToo by Laurie Winer

5 Things to Know and Rodgers and Hammerstein by Rania Aniftos

The Musicology of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from Rodgers & Hammerstein Carousel

Rodgers & Hammerstein’s CAROUSEL | Through Time and History

PBS’s Great Performances: “Rodgers & Hammerstein’s 80th Anniversary”

NPR’s Fresh Air: “How Rodgers And Hammerstein Revolutionized Broadway”

PODCAST: Carousel: Part One

PODCAST: Carousel: Part Two

• What instruments do you hear?

• How fast is the music? Are there sudden changes in speed? Is the rhythm steady or unsteady?

• Key/Mode: Is it major or minor? (Does it sound bright, happy, sad, urgent, dangerous?)

• Dynamics/Volume: Is the music loud or soft? Are there sudden changes in volume (either in the voice or orchestra)?

• What is the shape of the melodic line? Does the voice move smoothly, or does it make frequent or erratic jumps? Do the vocal lines move noticeably downward or upward?

• Does the type of voice singing (baritone, soprano, tenor, mezzo, etc.) have an effect on you as a listener?

• Do the melodies end as you would expect, or do they surprise you?

• How does the music make you feel? What effect do the factors above have on you as a listener?

• What is the orchestra doing in contrast to the voice? How do the two interact?

• What kinds of images, settings, or emotions come to mind? Does it remind you of anything you have experienced in your own life?

• Do particularly emphatic notes (low, high, held, etc.) correspond to dramatic moments?

• What type of character (romantic, comic, serious, etc.) fits this music?

People have been telling stories through music for millennia throughout the world. Opera is an art form that is over 400 years old, with roots in Western Europe. Here is a brief timeline of its lineage.

Please note that all date ranges for these time periods are approximate, and notice that some even overlap.

1573 The Florentine Camerata was founded in Italy, devoted to reviving ancient Greek musical traditions, including sung drama.

1598 Jacopo Peri (1561-1633), a member of the Camerata, composed the world’s first opera –Dafne – reviving the classic myth.

1607 Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) wrote L’Orfeo, the first opera to become popular, marking him as the premier opera composer of his day and bridging the gap between Renaissance and Baroque music. His works are still performed today.

1637 The first public opera house, Teatro San Cassiano, was built in Venice, Italy.

1673 Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), an Italian-born composer, brought opera to the French court, creating a unique style, tragédie en musique, that better suited the French language. Blurring the lines between recitative and aria, he created fast-paced dramas to suit the tastes of French aristocrats.

1689 Henry Purcell’s (1659-1695) simple and elegant chamber opera, Dido and Aeneas, premiered at Josias Priest’s boarding school for girls in London.

1712 George Frederic Handel (16851759), a German-born composer, moved to London, where he found immense success writing intricate and highly ornamented Italian opera seria (serious opera). Ornamentation refers to stylized, fast-moving notes, usually improvised by the singer to make a musical line more interesting and to showcase their vocal talent.

1750s A reform movement, led by Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), rejected the flashy ornamented style of the Baroque in favor of simple, refined music to enhance the drama.

1805 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), although a prolific composer, wrote only one opera, Fidelio. The extremes of musical expression in Beethoven’s music pushed the boundaries in the late Classical period and inspired generations of Romantic composers.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) wrote his first opera at age 11, beginning his 25-year opera career. Mozart mastered and then innovated in several operatic forms. He wrote opera serias (serious operas), including La Clemenza di Tito; and opera buffas (comedic operas) like Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). He then combined the two genres in Don Giovanni, calling it dramma giocoso (comedic drama). Mozart also innovated the Singspiel, a German sung play featuring spoken dialogue, as in Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute).

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) composed Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), becoming the most prodigious opera composer in Italy by age 24. He wrote 39 operas in 20 years. A new compositional style created by Rossini and his contemporaries, including Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini, would, a century later, be referred to as bel canto (beautiful singing). Bel canto compositions were inspired by the nuanced vocal capabilities of the human voice and its expressive potential. Composers employed strategic use of register, the push and pull of tempo (rubato), extremely smooth and connected phrases (legato), and vocal glides (portamento).

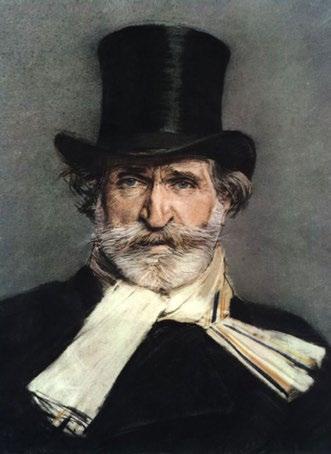

1853 Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) completed La Traviata, a story of love, loss, and the struggle of average people, in the increasingly popular realistic style of verismo. Verdi enjoyed immense acclaim during his lifetime, while expanding opera to include larger orchestras, extravagant sets and costumes, and more highly trained voices.

1842 Inspired by the risqué popular entertainment of French vaudeville, Hervé (1825-1892) created the first operetta, a short comedic musical drama with spoken dialogue. Responding to popular trends, this new form stood in contrast to the increasingly serious and dramatic works at the grand Parisian opera house. Opéra comique as a genre was often not comic, tending to be more realistic or humanistic instead. Grand opera, on the contrary, was exaggerated and melodramatic.

1865 Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) Tristan und Isolde was the beginning of musical modernism, pushing the use of traditional harmony to its extreme. His massively ambitious, lengthy operas, often based in German folklore, sought to synthesize music, theatre, poetry, and visuals in what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). The most famous of these was an epic four-opera drama, Der Ring des Nibelungen, which took him 26 years to write and was completed in 1874.

1871 Influenced by French operetta, English librettist W.S. Gilbert (1836-1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) began their 25-year partnership, which produced 14 comic operettas, including The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Their works inspired the genre of American musical theatre.

Johann Strauss II, (1825-1899) influenced largely by his father, with whom he shared a name and talent, composed Die Fledermaus, popularizing Viennese musical traditions, namely the waltz, and further shaping operetta

Giacomo Puccini’s (1858-1924) La bohème captivated audiences with its intensely beautiful music, realism, and raw emotion. Puccini enjoyed huge acclaim during his lifetime for his works.

1911 Scott Joplin, (1868-1917) “The King of Ragtime,” wrote his only opera, Treemonisha, which was not performed until 1972. The work combined the European lateRomantic operatic style with African American folk songs, spirituals, and dances. The libretto, also by Joplin, was written at a time when when African Americans in the southern United States rarely had access to literacy resources and education.

1927 American musical theatre, commonly referred to as Broadway, was taken more seriously after Jerome Kern’s (1885-1945) Show Boat, with words by Oscar Hammerstein II (18951960), tackled issues of racial segregation and the ban on interracial marriage in Mississippi.

Alban Berg (1885-1935) composed the first completely atonal opera, Wozzeck, dealing with uncomfortable themes of militarism and social exploitation. Wozzeck is in the style of 12-tone music, or serialism. This new compositional style, developed in Vienna by composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), placed equal importance on each of the 12 pitches in a chromatic scale (all half steps), removing the sense of the music being in a particular key.

1945 British composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) gained international recognition with his opera Peter Grimes. Britten, along with Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), was one of the first British opera composers to gain fame in nearly 300 years.

John Adams (b. 1947) composed one of the great minimalist operas, Nixon in China, the story of Nixon’s 1972 meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong. Musical minimalism strips music down to its essential elements, usually featuring a great deal of repetition with slight variations.

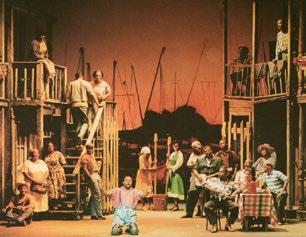

1935 American composer George Gershwin (1898-1937), who was influenced by African American music and culture, debuted his opera, Porgy and Bess, in Boston, MA with an allAfrican American cast of classically trained singers. His contemporary, William Grant Still (1895-1978), a master of European grand opera, fused that with the African American experience and mythology. His first opera, Blue Steel, premiered in 1934, one year before Porgy and Bess.

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), known for synthesizing musical genres, brought together the best of American musical theatre, opera, and ballet in West Side Story, a reimagining of Romeo and Juliet in a contemporary setting.

Anthony Davis (b. 1951) premiered his first of many operas, X: The Life and Time of Malcom X, which reclaims stories of Black historical figures within the theatre space. He incorporated both the orchestral and vocal techniques of jazz and classical European opera in his score for a distinctly American sound, and a fully realized vision of how jazz and opera are in conversation within a work.

Still a vibrant, evolving art form, opera attracts contemporary composers such as Philip Glass (b. 1937), Jake Heggie (b. 1961), Terence Blanchard (b. 1962), Ellen Reid (b. 1983), and many others. Composers continue to be influenced by present and historical musical forms in creating new operas that explore current issues or reimagine ancient tales.

Opera is unique among forms of singing in that singers are trained to be able to sing without amplification, in large theaters, over an entire orchestra, and still be heard and understood! This is what sets the art form of opera apart from similar forms such as musical theatre. To become a professional opera singer, it takes years of intense physical training and constant practice — not unlike that of a ballet dancer — to stay in shape. Poor health, especially respiratory issues and even allergies, can be severely debilitating for a professional opera singer. Let’s peek into some of the science of this art form.

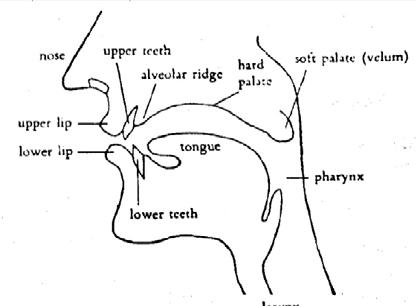

Singing requires different parts of the body to work together: the lungs, the vocal cords, the vocal tract, and the articulators (lips, teeth, and tongue). The lungs create a flow of air over the vocal cords, which vibrate. That vibration is amplified by the vocal tract and broken up into words by consonants, which are shaped by the articulators.

Any good singer will tell you that good breath support is essential to produce quality sound. Breath is like the gas that goes into your car. Without it, nothing runs. In order to sing long phrases of music with clarity and volume, opera singers access their full lung capacity by keeping their torso elongated and releasing the lower abdomen and diaphragm muscles, which allows air to enter into the lower lobes of the lungs. This is why we associate a certain posture with opera singers. In the past, many operas were staged with singers standing in one place to deliver an entire aria or scene, with minimal activity. Modern productions, however, often demand a much greater range of movement and agility onstage, requiring performers to be physically versatile, and bringing more visual interest, authenticity of expression, and nuanced acting into the storytelling.

If you run your fingers along your throat, you will feel a little lump just underneath your chin. That is your “Adam’s Apple,” and right behind it, housed in the larynx (voice-box), are your vocal cords. When air from the lungs crosses over the vocal cords it creates an area of low pressure (Google The Bernoulli Effect), which brings the cords together and makes them vibrate. This vibration produces a buzz. The vocal chords can be lengthened or shortened by muscles in the larynx, or by changing the speed of air flow. This change in the length and thickness of the vocal cords is what allows singers to create different pitches. Higher pitches require long, thin cords, while low pitches require short, thick ones. Professional singers take great pains to protect the delicate anatomy of their vocal cords with hydration and rest, as the tiniest scarring or inflammation can have noticeable effects on the quality of sound produced.

Without the resonating chambers in the head, the buzzing of the vocal cords would sound very unpleasant. The vocal tract, a term encompassing the mouth cavity, and the back of the throat, down to the larynx, shapes the buzzing of the vocal cords like a sculptor shapes clay. Shape your mouth in an ee vowel (as in eat), then sharply inhale a few times. The cool sensation you feel at the top and back of your mouth is your soft palate. The soft palate can raise or lower to change the shape of the vocal tract. Opera singers often sing with a raised soft palate, which allows for the greatest amplification of the sound produced by the vocal cords. Different vowel sounds are produced by raising or lowering the tongue, and changing the shape of the lips. Say the vowels: ee, eh, ah, oh, oo and notice how each vowel requires a slightly lower tongue placement and slightly rounder lips. This area of vocal training is particularly difficult because none of the anatomy is visible from the outside!

The lips, teeth, and tongue are all used to create consonant sounds, which separate words into syllables and make language intelligible. Consonants must be clear and audible for the singer to be understood. Because opera singers do not sing with amplification, their articulation must be particularly good. The challenge lies in producing crisp, rapid consonants without interrupting the connection of the vowels (through the controlled exhalation of breath) within the musical phrase.

Perfecting every element of this complex singing system requires years of training and is essential for the demands of the art form. An opera singer must be capable of singing for hours at a time, over the powerful volume of an orchestra, in large opera houses, while acting and delivering an artistic interpretation of the music. It is complete and total engagement of mental, physical, and emotional control and expression. Therefore, think of opera singers as the Olympic athletes of the stage, sit back, and marvel at what the human body is capable of!

Opera singers are cast into roles based on their tessitura (the range of notes they can sing comfortably). There are many descriptors that accompany the basic voice types, but here are some of the most common ones:

The lowest voice, basses often fall into two main categories: basso buffo, which is a comic character who often sings in lower laughing-like tones, and basso profundo, which is as low as the human voice can sing! Doctor Bartolo is an example of a bass role in The Barber of Seville by Rossini.

A middle-range lower voice, baritones can range from sweet and mild in tone, to darker dramatic and full tones. A famous baritone role is Rigoletto in Verdi’s Rigoletto. Baritones who are most comfortable in a slightly lower range are known as Bass-Baritones, a hybrid of the two lowest voice types.

The highest of the lower-range voices, tenors often sing the role of the hero. One of the most famous tenor roles is Roméo in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. Sometimes, singers with lower-range voices also cultivate much higher ranges, singing in a range similar to a mezzo-soprano or soprano by using their falsetto register. Called the Countertenor, this voice type is often found in Baroque music. Countertenors replaced castrati in the heroic lead roles of Baroque opera after the practice of castration was deemed unethical.

Each of the voice types (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, baritone, bass) also tends to be sub-characterized by tone descriptors such as “lyric” or “dramatic.” Lyric singers tend toward smooth lines in their music, sensitively expressed interpretation, and flexible agility. Dramatic singers have qualities that are attributed to darker, fuller, richer note qualities expressed powerfully and robustly with strong emotion. While it’s easiest to understand operatic voice types through these designations and descriptions, one of the most exciting things about listening to a singer perform is that each individual’s voice is essentially unique, so each singer will interpret a role in an opera in a slightly different way.

The lowest of the higher treble voices has a low range that overlaps with the highest tenor’s range. This voice type is less common.

Somewhat equivalent to an alto role in a chorus, mezzo-sopranos (mezzo meaning “middle”) are known for their full and expressive qualities. While they don’t sing frequencies quite as high as sopranos, their ranges do overlap, and it is a “darker” tone that sets them apart. One of the most famous mezzo-soprano lead roles is Carmen in Bizet’s Carmen.

The highest voice. Some subtypes of the soprano voice include coloratura, lyric, and dramatic sopranos. Coloratura sopranos specialize in being able to sing fast-moving notes that are very high in frequency, often referred to as “color notes.” One of the most famous coloratura roles is the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

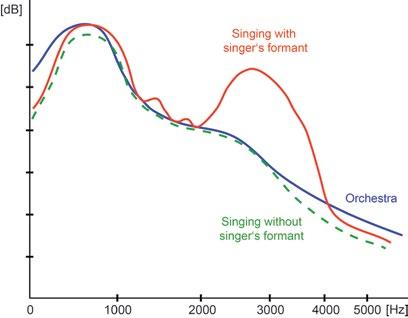

What is it about opera singers that allows them to be heard above the orchestra? It’s not that they simply singing louder. The qualities of sound have to do with the relationship between the frequency (pitch) of a sound, represented in a unit of measurement called hertz, and its amplitude, measured in decibels, which the ear perceives as loudness. Only artificially produced sounds, however, create a pure frequency and amplitude (these are the only kind that can break glass). The sound produced by a violin, a drum, a voice, or even smacking your hand on a table, produces a fundamental frequency as well as secondary, tertiary, etc. frequencies known as overtones, or as musicians call them, harmonics

The orchestra tunes to a concert “A” pitch before a performance. Concert “A” has a frequency of about 440 hertz, but that is not the only pitch you will hear. Progressively softer pitches above that fundamental pitch are produced in multiples of 440 at 880hz, 1320hz, 1760hz, etc. Each different instrument in the orchestra, because of its shape, construction, and mode in which it produces sound, produces different harmonics. This is what makes a violin, for example, have a different color (or timbre ) from a trumpet. Generally, the harmonics of the instruments in the orchestra fade around 2500hz. Overtones produced by a human voice—whether speaking, yelling, or singing— are referred to as formants

As the demands of opera stars increased, vocal teachers discovered that by manipulating the empty space within the vocal tract, they could emphasize higher frequencies within the overtone series—frequencies above 2500hz. This technique allowed singers to perform without hurting their vocal cords, as they are not actually singing at a higher fundamental decibel level than the orchestra. Swedish voice scientist Johan Sundberg observed this phenomenon when he recorded the world-famous tenor Jussi Bjoerling in 1970. His research showed multiple peaks in decibel level, with the strongest frequency (overtone) falling between 2500 and 3000 hertz. This frequency, known as the singer’s formant , is the “sweet spot” for singers so that we hear their voices soaring over the orchestra into the opera house night after night.

that are specific to each particular

like a

When two people sing the same note simultaneously, the high overtones allow your ear to distinguish two voices.

The final piece of the puzzle in creating the perfect operatic sound is the opera house or theater itself. Designing the perfect acoustical space can be an almost impossible task, one which requires tremendous knowledge of science, engineering, and architecture, as well as an artistic sensibility. The goal of the acoustician is to make sure that everyone in the audience can clearly understand the music being produced onstage, no matter where they are sitting. A perfectly designed opera house or concert hall (for non-amplified sound) functions almost like gigantic musical instrument.

Reverberation is one key aspect in making a singer’s words intelligible or an orchestra’s melodies clear. Imagine the sound your voice would make in the shower or a cave. The echo you hear is reverberation caused by the large, hard, smooth surfaces. Too much reverberation (bouncing sound waves) can make words difficult to understand. Resonant vowel sounds overlap as they bounce off hard surfaces and cover up quieter consonant sounds. In these environments, sound carries a long way but becomes unclear or — as it is sometimes called — wet, as if the sound were underwater. Acousticians can mitigate these effects by covering smooth surfaces with textured materials like fabric, perforated metal, or diffusers, which absorb and disperse sound. These tools, however, must be used carefully, as too much absorption can make a space dry — meaning the sound onstage will not carry at all and the performers may have trouble even hearing themselves as they

perform. Imagine singing into a pillow or under a blanket.

The shape of the room itself also contributes to the way the audience perceives the music. Most large performance spaces are shaped like a bell – small where the stage is and growing larger and more spread out in every dimension as one moves farther away. This shape helps to create a clear path for the sound to every seat. In designing concert halls or opera houses, big decisions must be made about the construction of the building based on acoustical needs.

Even with the best planning, the perfect acoustic is not guaranteed, but professionals are constantly learning and adapting new scientific knowledge to enhance the audience’s experience.

You will see a full dress rehearsal – an insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera premieres. The singers will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and an orchestra will accompany the singers, who may choose to “mark,” or not sing in full voice, to save their voices for the performances. A final dress rehearsal is often a complete run-through, but there is a chance the director or conductor will ask to repeat a scene or section of music. This is the last opportunity the performers have to rehearse with the orchestra before opening night, and they therefore need this valuable time to work. The following will help you better enjoy your experience of a night at the opera:

• Arrive on time! Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks in the performance and often not until intermission.

• Dress in what you are comfortable in so you can enjoy the performance. For some, that may mean dressing up in a suit or gown; for others, jeans and a t-shirt is fine. Generally, “dressycasual” is what people wear. Live theatre is usually a little more formal than a movie theater.

• At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra will ask the oboist to play the note “A.” You will hear all the other musicians in the orchestra tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. You can applaud to welcome them!

• Feel free to applaud or shout "Bravo!" at the end of an aria or chorus piece if you really liked it. The end of a piece can usually be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• It’s OK to laugh when something is funny or gasp at something shocking!

• When translating songs, and poetry in particular, much can be lost due to a change in rhythm, inflection, and rhyme of words. For this reason, opera is usually performed in its original language. In order to help audiences enjoy the music and follow every twist and turn of the plot, English supertitles are projected. Even when the opera is in English, there are still supertitles.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, pay attention to repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

The singers, orchestra, dancers, and stage crew are all hard at work to create an amazing performance for you! Here’s how you can help them.

• Lit screens are very distracting to the singers, so please keep your phone off and out of sight until the house lights come up.

• Due to how distracting electronics can be for performers, taking photos or making audio or video recordings is strictly forbidden.

The theater is a shared space, so please be courteous to your neighbors!

• Please do not take off your shoes or put your feet on the seat in front of you.

• Respect your fellow opera lovers by not leaning forward in your seat so as to block the person’s view behind you.

• Do not chew gum, eat, or drink while the rehearsal is in session. Not only can it pull focus from the performance, but the ushers are not there to clean up after you.

• If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly.

Otherwise, sit back, relax, and let the action onstage pull you in. As an audience member, you are essential to the art form of opera — without you, there is no show!

Have Fun and Enjoy the Opera!