AN OPERA GUIDE TO

Dear Opera Curious and Opera Lovers alike,

March 10, 2025

Boston Lyric Opera is thrilled to welcome you to the Emerson Paramount Center for a truly unforgettable experience —The Seasons, an innovative new work co-conceived by celebrated playwright Sarah Ruhl and countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo.

Opera has a way of tapping into big emotions in a way that’s hard to describe. There’s something incredibly powerful about experiencing the human voice live in the theater, and I believe that whether you’re new to opera or have loved it for years, there’s always something new to discover. To help make your experience even richer, we’ve put together this Guide. It’s designed to give you a little background on the opera and its themes, as well as some plot details (spoiler alert!). Our intent is to provide support in historical and contemporary context, along with tools to thoughtfully reflect on the opera before or after you attend.

Boston Lyric Opera inspires, entertains, and connects communities through compelling performances, programs, and gatherings. Our vision is to create operatic moments that enrich everyday life. As we develop additional Guides, we’re always eager to hear how we can improve your experience. Please tell us about how you use this Guide and how it can best serve your future learning and engagement needs by emailing education@blo.org.

If you’re interested in engaging with us further and learning about additional opera education opportunities with Boston Lyric Opera, please visit blo.org/ education to discover our programs and initiatives. We can’t wait to share this experience with you.

Warmly,

Nina Yoshida Nelsen

Artistic Director

Boston Lyric Opera

by Sarah Ruhl

“ „ „ „ „ “ “ “

It’s that the world was failing at its one task — remaining a world. Pieces were breaking off. Seasons had become postmodern. We no longer knew where in the calendar we were by the weather…the ice cubes were melting… New things to die of were being added each day. We were angry all the time.

— Sheila Heti, Pure Colour: A Novel

If grief can be a doorway to love, then let us all weep for the world we are breaking apart so we can love it back to wholeness again.

— by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeating refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.

— Rachel Carson

Both fire scientists and firefighters have suggested dropping the word season; the threat, they say, is year-round…

— David Wallace-Wells, author of The Uninhabitable Earth

Photo by Zach Dezon

As we sit in rehearsals in New York City for this opera, the world burns: this is the third day of the wildfires in Los Angeles, creating historical, unfathomable loss. By day, the creative team listens to arias; by night, we check on loved ones and friends who are now – very suddenly – without houses, and who have become (what may have seemed like an abstract term a mere year ago ): “climate refugees.” This is our new normal.

On one hand, I don’t have to remind anyone that the weather is getting more extreme as a result of concrete human policies; we experience these changes on almost a daily basis. On the other hand, I find that we are often numb to these changes: either they feel far away and televised, or they feel so close to home that we are in shock, in survival mode. So for many, it is hard to feel anything about the changing weather besides uneasy dread.

Facing a burning world is so disturbing that people often dissociate, trying not to feel anything about the earth’s trajectory. I wanted, with this opera, to see if audiences and collaborators could feel something about our changing weather, in an artistic space. Music opens us emotionally, and the familiarity of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons reminds me that the seasons themselves used to feel achingly familiar. By contrast, every year the seasons seem to get less familiar.

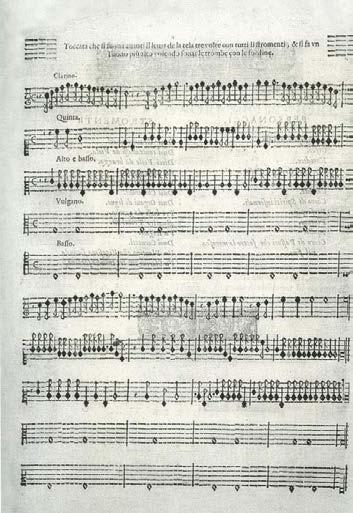

LWhen I was little, I grew up listening to The Four Seasons on a cassette tape during long car trips with my family, looking out from the backseat window at the leaves, or the snow. I imagined the drama of the weather; or I saw it, looking out of the car window at a winter storm, often driving from Chicago to Iowa. When I grew up, I learned that Antonio Vivaldi, the “Red Priest,” wrote sonnets to accompany his Four

Seasons. Each poetic line created specific imagery to go with particular moments in the concertos: birdsong, a goatherd sleeping, a drought, a rainstorm, a harvest, a hunt, a storm, a deep freeze.

When the visionary countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo approached me to work on a Baroque pastiche centering the work of Vivaldi, my first thought was to create a piece around The Four Seasons, but with the seasons out of order, reflecting our contemporary situation of disordered and extreme weather. I wanted to write my own haiku to partner with the music, a tribute to Vivaldi’s impulses to pair his music with poetry.

During the pandemic, when theaters were shut down, nature became my theater. I wrote one haiku a day to mark the transformations outside my window.

During the pandemic, when theaters were shut down, nature became my theater. I wrote one haiku a day to mark the transformations outside my window. I started as a poet, but became a playwright in my twenties; for two decades, I was in the theater almost constantly, working as a playwright indoors, often in the dark. During the quiet of the pandemic, like many other people, I noticed birdsong as if for the first

time. Observing the incremental seasonal changes in the natural world became my preoccupation; marking these momentary transformations with haiku became my practice. After the quarantine ended, I felt irresponsible not writing about the changes in the weather that were all around me.

As I worked on this libretto, I wondered what Vivaldi might have to teach us about the seasons and harmony, or about the seasons and disharmony. In the Baroque period, the natural world reflected an order in the cosmos, a sort of divine mirror. To me, Vivaldi’s music feels oddly Taoist — a celebration of change as the only constant. When I did a deep dive into Vivaldi, it was a revelation to discover that he wove many of the melodies from The Four Seasons into other arias and choral pieces. You can clearly hear a melody from the “Winter” movement in Tito Manlio’s “Se il cor guerriero”; you can hear the “Spring” melodies in the choral piece Dell’aura al sussurrar. I also found, to my delight, that his operatic characters often sang about the weather — less about the weather outside of them, and more about the weather inside of them, as in the aria “Sento in seno,” in which the singer “rains tears.” I started to think about how artists often feel their own internal emotional weather deeply, and less deeply about the weather outside of them.

A note on love in this piece; these characters fall in love quickly, almost in the Greek vernacular of Cupid’s arrow piercing the heart suddenly and immediately — just as the weather changes quickly around them. I thought, too, of Shakespeare’s romances and the Ovidian speed of love and transformation. We often feel we cannot control love, just as we cannot control the weather. And even as larger political and existential questions loom, human beings still find a way to love, and to obsess about the romance that is right in front of them. Just as the weather is fluid, so too is sexuality somewhat fluid in this piece; one countertenor role (The Choreographer) is played by a mezzo-soprano

in this version, without any change to the story. In opera, “pants roles” (women playing men’s roles) were common — often a contralto playing the role of an adolescent man. In this piece, the gender of any character can all be changed without a problem, as long as each voice suits the vocal demands of its role. I am passionate about putting love stories onstage that don’t make a big deal of which gender loves which gender — in other words, stories in which gender is not the focal point of love.

I am passionate about putting love stories onstage that don’t make a big deal of which gender loves which gender — in other words, stories in which gender is not the focal point of love.

There is plenty I don’t know about opera, having been trained as a playwright and poet who can read music (but plays piano not very well at all). As such, I learned a great deal every day I worked on this piece — and I recommend learning something new the older you get. I learned beautiful and useful words like melisma, and I learned about the surprising relationship between improvisational jazz and the freedom with which Baroque singers can ornament their da capo sections.

When the brilliant director Zack Winokur came aboard, we started to create a world where dance, poetry, and song could come together to create story in innovative ways. I was interested in how the text for the arias could swing back and forth between English and Italian, between pure passion (the original Italian) and a sort of close-up on the da capo sections (new English translations). My hope was to create room in these juxtapositions, towards which the audience could lean forward to hear in new ways. And I started to hope for an adjustment, for people who make art and people

who appreciate art, to start to feel something — really feel something — about the weather outside them, which urgently demands their attention.

I began this piece before I actually saw a weatherman, while he reported on the most recent devastating hurricane in Florida, crying on the news.

I began this piece before I actually saw a weatherman, while he reported on the most recent devastating hurricane in Florida, crying on the news. I started writing it before seeing one weatherman in Iowa quit because he got death threats for mentioning climate change on the air. My inspiration for the character of “The Cosmic Weatherman” was my feeling that we long for godlike omniscience from our weather reporters, when all they can do these days is helplessly report on extreme weather.

It seemed important in a piece about climate change to create a set with the smallest possible carbon footprint. Mimi Lien has done just that.

It seemed important in a piece about climate change to create a set with the smallest possible carbon footprint, and our brilliant scenic designer Mimi Lien has done just that. Lien and Jack Forman (from the MIT Media Lab) have synthesized unprecedented technology for us to use as theatrical weather — snow that flies upward, mountains of snow that can disappear — using nothing more than soap! Yesterday, one of the singers in the piece, Alexis Peart, remarked that making ancient songs new, and bringing Vivaldi into the present moment, is in itself a kind of recycling.

As our team collaborated, we sought the advice of climate justice activists, who emphasized two points:

1) the important role of storytelling in melting our numbness and 2) the fact that so many of the solutions to climate change are already here, and have been here for a long time; the world just needs the political will to change the course of history and move away from its dependence on fossil fuels.

sWhen I was in fourth grade, we studied land masses. I took it upon myself to write a play, my first full-length: a courtroom drama about an isthmus. All the land masses spoke — islands, archipelagos, mountains. The dispute between land masses got heated. And the sun had to come down and settle things in a deus ex machina

I still have the land mass play, handwritten in a flowered binder. It began like this:

SKY: I watch the earth from above.

WATER: I watch the earth while traveling.

LAND: I watch the earth on a level.

SKY: As I watch there has been a shortage in the water system.

LAND: That is very true. The tributary has stopped functioning and there has been confusion ever since.

This would have been 1985, before discussions about climate change had entered elementary schools. I’m not sure what possessed me. I gave my teacher, Mr. Spangenberger, the play, hopeful that he would produce it in the auditorium He said no, and it remains my very first unproduced play. Yet, here I am now, writing an opera not with talking land masses but where people dance the weather.

Working with iconic choreographer Pan Tanowitz has been a revelation: she finds ways for her dancers to dance the weather and also the feeling of weather; to express the Baroque inside our strange contemporary

moment. John Cage once said of collaboration in an interview with Merce Cunningham: “It’s less like an object and more like the weather. Because in an object, you can tell where the boundaries are. But in the weather, it’s impossible to say when something begins or ends. We hope that the weather will continue. And we trust that our way of relating dance and music will also continue.”

I echo Cage in this fervent hope — that the weather will continue — and that “our way of relating dance and music will also continue.” There is almost no limit to what we can do with our bodies and our voices without imperiling our ecosystem. We can sing and dance our way forward into joy. I have learned from activist friends in the environmental space that hope is a precondition for action. Let this be a ritual of hope that binds the performers and the audience together.

To quote Vivaldi’s choral work Gloria: Et in terra pax hominibus And on earth, Let peace be unto us – Sarah Ruhl

These characters were written to be flexible for any gender to play as long as the voice matches the vocal demands of the part. Here are the vocal parts for the BLO production.

The Poet, countertenor

The Farmer, soprano

The Painter, countertenor

The Performance Artist, soprano

The Choreographer, mezzo-soprano

The Cosmic Weatherman, baritone

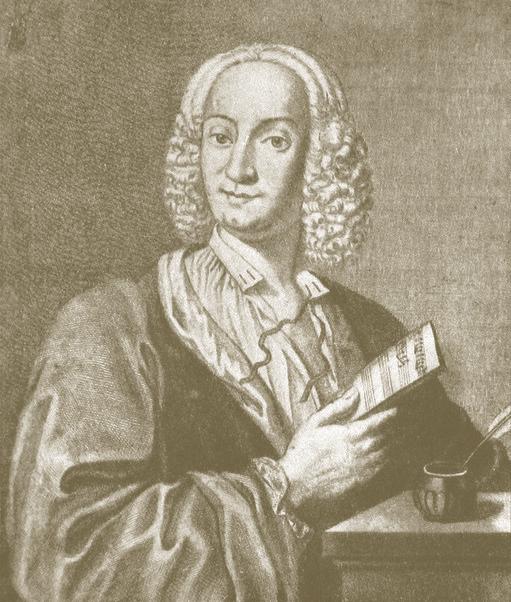

Antonio Vivaldi was an Italian composer, violinist, teacher, and impresario of the Baroque period, perhaps best known today for his instrumental compositions, particularly those for strings. As a composer, he is credited with popularizing and establishing numerous innovations in form, style, and orchestration. He was known for working hard and speedily, and he wore many hats, professionally speaking. Vivaldi’s influence on European music was far-reaching during his lifetime, and the popularity of his compositions was undeniable. However, his work gradually faded into obscurity after his death and was not revived to any great degree until the 1920s, nearly 200 years later.

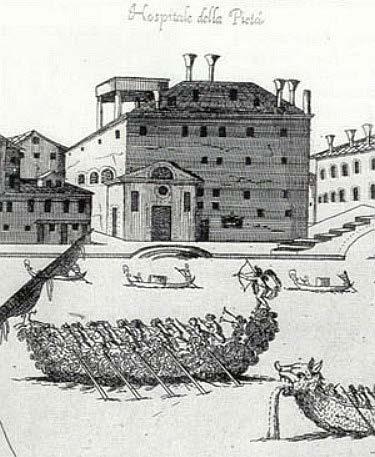

Antonio was born on March 4, 1678 in Venice, the Italian “floating city” famous for its canals. Legend would have it that an earthquake shook the city on the day of his birth, but this rumor has since been discredited by historians.1 From birth, it was clear that Antonio’s health was not quite what it ought to be, and he struggled with chronic respiratory difficulties throughout his life, which are now thought to have been some form of asthma. Among his five known siblings, Antonio became the only professional musician. His father, Giovanni Battista Vivaldi, had been a barber by trade before becoming a violinist and was likely Antonio’s first music teacher.2 He certainly taught him to play the violin, and they performed together throughout Venice while Antonio was still quite young. His father worked as a musician in the Basilica di San Marco under the maestro di cappella Giovanni Legrenzi, who may have given Antonio lessons in organ, theory, and possibly composition.3 Due to sparse and sometimes inconsistent records, little is known for certain about Antonio’s earliest musical education. Whatever his training, he clearly had a solid foundation in the musical arts when he

1 Micky White, Antonio Vivaldi: A Life in Documents, Florence: Olschki, 2013, 11.

2 Michael Talbot, Vivaldi, London: J.M. Dent, 1978, 36-39.

3 Karl Heller, Antonio Vivaldi: The Red Priest of Venice, Trans. David Marinelli, Portland: Amadeus Press, 1997, 40.

accepted a professional post at the Ospedale della Pietà, a convent and orphanage that housed a wellrespected music conservatory. However, before he found his way to this job – which would figure in his professional life for most of the next 40 years – Antonio Vivaldi was looking in another direction altogether.

At age 15, Vivaldi began studying to be a priest and was ordained ten years later, in 1703. He is

famously remembered by the nickname “The Red Priest,” which he apparently acquired due to his vividly red hair. However, he did not remain a priest for very long after his ordination. Varying accounts attribute this to such wide-ranging causes as his poor health and a deeper desire to pursue music.4 In the same year that he left the priesthood, Antonio turned his professional attention to music full-time. At the age of 24, he was hired

Vivaldi most likely left his work as a priest because of his health, as his respiratory condition would have made it difficult to say lengthy Masses, which would have also required him to sing and chant in Latin extensively. But one rumor that surfaced during this period of Vivaldi’s life was that he once got so distracted by a fugue theme he thought up during Mass that he stopped the celebration, went to his office to write out his idea, and then returned to finish the church service!

as a musician at the Ospedale della Pietà. Over time, he served as a teacher, orchestra director, violinist, composer, choir director, and purchaser of instruments for the Pietà – often serving in multiple posts at once, as would have been common in similar situations at the time. His responsibilities would have included teaching music theory, the playing of specific instruments, or both; composing vocal and instrumental music for all sorts of ensembles and occasions, including sacred and secular festivities; rehearsing and conducting the choir and orchestra; and much more. The Pietà and similar institutions in Venice were well-funded by their patrons. As a result, working at the Pietà gave Vivaldi access not only to a respectable budget, but also ample opportunities to experiment creatively and hone his skills as a composer. Since his contract required him to keep his students constantly supplied with new music to learn – both for their own improvement and for public performances, which were given on nearly every feast day and holiday – Vivaldi’s compositional output for the Pietà was considerable. He wrote dozens of concertos, symphonies, and oratorios – one major work for every feast day and many more works, besides. 5

Eighteenth-century Venice was obsessed with music. The city’s artistic history and reputation was rich and well-established and had been since at least the Renaissance. Antonio Vivaldi, whose family was neither wealthy nor of a high-ranking social class, was born into a period of particular intensity in the musical life of the city. Music and music-making touched every level of society. From people singing in the streets as they went

5 Ibid, 24-27.

6 Ibid, 30-33.

about their daily business, to the many and famous improvised songs of the gondoliers steering the canal boats, to the aristocrats who not only owned theaters and sponsored musicians financially but also were often amateur musicians themselves at a time when other European aristocrats scorned instrumentalists as lowerclass – in these ways and many more, music accompanied daily Venetian life. Venice had been the first city in Europe to open an opera house with a paying public in 1637. Five or six major theaters were fully active in the city throughout a given year’s three opera seasons – perhaps not unlike the U.S. sports seasons we are used to in modern times – and the city had an international reputation as a powerhouse in the realm of opera.6 Such was the Venice that Vivaldi grew up in, absorbing music of all styles, genres, and social classes; and such was the Venice in which he reached his maturity as a composer.

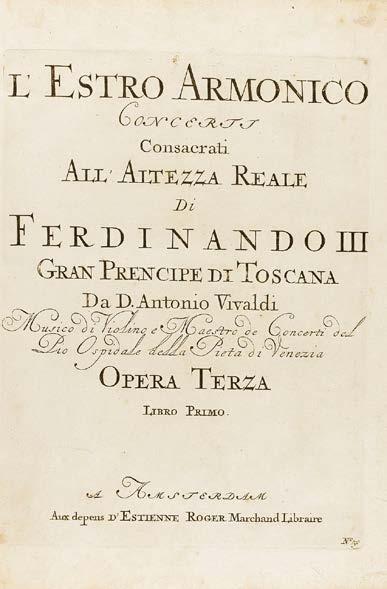

In addition to his many and various duties at the Pietà, Vivaldi began to have his compositions published in 1705, which saw the publication of his first collection of sonatas. By 1712, his Opus 3 – a set of violin concertos called L’estro armonico – had established his reputation throughout Europe. Within a year, the Pietà had

given Vivaldi leave to travel and put his musical talents to use outside the city of Venice. 1713-1718 saw him writing operas and other works for major theaters in other Italian cities like Vicenza and Florence, and at one point he turned out six operas in two years.7 As Vivaldi ventured further out into the world, his popularity spread. His published concertos were becoming known in major cities and even reaching some tiny towns. His style also became known to visiting musicians and music students from across Europe, who absorbed his techniques and took them back to their homelands. Additionally, Vivaldi was often actively involved as conductor and virtuoso violinist in performances of his own works, which would not have been unusual for composers of his time.8 Evidence from some of his surviving letters indicates a practical man who understood the scope and specifics of mounting a concert or opera production – and who, at this point in his career, probably concerned himself with the smallest details because he had to. One letter discussing just one opera season at Ferrara (likely about one-third of the year) indicates that

7 Ibid, 37-39.

8 Ibid, 40-41.

Vivaldi composed quickly, even inventing a musical shorthand that he used to speed things along. This makes sense when he was constantly expected to provide music for the Pietà’s chorus and orchestra, as well as writing operas and other works for outside engagements. If he had especially little time, he sometimes reused or reimagined passages from his own – or other composers’ – existing works. This was normal at the time; even Bach did this occasionally. Even Vivaldi’s most famous work, The Four Seasons, contains music from his own oratorio Juditha, including the melody from Judith’s aria “Vivat in pace.”

Vivaldi not only provided his music to the theater, but also recruited the singers, instrumentalists, and dancers; adjusted the length of the show to suit its likely audiences; had copies made of all the scores; was involved in the logistics of selling tickets; and may have also been involved in stage direction and choreography.9 As quickly and fervently as he composed music, Vivaldi apparently approached all the practical aspects of producing a show with similar energy.

From 1718-1722, Vivaldi vanishes from the records of the Pietà. (This happened a few more times before he finally left his post for good in 1740.) Around this time, he accepted the prestigious position of maestro di cappella in the court of Prince Philip of Hesse-Darmstadt, governor of Mantua. He moved there for three

9 Ibid, 58.

10 Talbot, 64.

11 Pincherle, 46.

years and produced several operas, after which he brought his distinctive operatic style to Rome – a fierce musical competitor of Venice –in 1722.10 Upon returning to Venice a few years later and resuming his post at the Pietà, the terms of his contract were amended, limiting his teaching responsibilities so he could prioritize traveling, composing, and performing. By now, he was famous across Europe, and the Pietà – while wanting to use his talents as often as possible – did not want to tie him down too strictly and thus risk losing him altogether. Indeed, after 1725, the bulk of Vivaldi’s professional work lay in freelancing, and he traveled more frequently, farther away, and for longer periods of time, occasionally returning to Venice to stage a new opera or attend to his duties at the Pietà.11 This later period of his composition, which lasted until

his death in 1741, included several commissions by European nobility and royalty, including cantatas, concertos, and operas.

In the last few years of his life, Vivaldi found the popularity of his music ebbing in the face of the mercurial artistic tastes of Venice, which hungered for the newest musical trend. After selling off some of his manuscripts for additional money, he moved to Vienna, evidently hoping to continue composing there with the support of Emperor Charles VI.12 Unfortunately, the emperor died shortly thereafter, and Vivaldi lost the prospect of a royal and reliable source of income. By the time of his own death in July 1741 at the age of 63, the composer had become seriously impoverished.

After his death, Vivaldi’s music gradually faded into obscurity before undergoing an enthusiastic revival in the early 20th century. Although some of his works

12 Walter Kolneder, Antonio Vivaldi: His Life and Work, Trans. Bill Hopkins, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1970, 180.

13 Scaramuccia, “New Discoveries of Vivaldi (2016),” https://scaramucciaensemble.com/en/newdiscoveries-of-vivaldi/ (2024), accessed 6 January 2025.

remain lost, we know that Vivaldi is responsible for producing a staggering amount of music. He wrote over 500 concertos (around 230 of which are for violin), numerous sacred works like cantatas and oratorios, anywhere between 46 and 94 operas, and about 90 sonatas and other forms of chamber music.

He solidified the concerto as a standard and popular instrumental form. His stylistic influence is deep and direct in some of the most famous works of Johann Sebastian Bach, a titan of Baroque music. The Four Seasons, a group of four violin concertos based on sonnets about the seasons of the year, remain Vivaldi’s best-known and most popular composition today. Several more lost Vivaldi works have been rediscovered and performed in the twenty-first century, most recently in 201513 – so who knows what Vivaldi may yet have in store for us?

It was common for composers in Vivaldi’s time to work many jobs (conductor, teacher, performer, etc.) in addition to composing.

Why do you think this was?

Do you think this is still true of musicians today?

Why or why not?

How might you or someone you know relate?

The term “countertenor” has a long history. Its earliest use refers to a specific harmony part in polyphonic choral works of the 14th and 15th centuries. Women were not allowed to sing in church – a main source of choral music at the time –so some male singers using falsetto would sing the high parts, sometimes joining the young boys of the choir. Eventually, the word “countertenor” came to refer generally to male singers who use their voices in a high range comparable to that of alto, mezzo-soprano, or soprano singers.

By the time opera started emerging in 17th-century Italy, a fashion for castrato singers also emerged, and their unique sound made them the pop stars of Baroque opera. Within the century, changing musical tastes and medical ethics led to the decline of this practice, though castrati were not banned by the Vatican until 1903. In modern performances of Baroque operas, roles originally written for castrati are typically sung by countertenors. Many of these Baroque roles that are still popular today come from the operas of George Frideric Handel (1685-1759).

Today, there is disagreement among voice teachers, voice scientists, and even singers themselves about what makes a countertenor. Is “countertenor” a unique voice type, a specific way of training the male voice, some combination of the two… or something else? The debate continues, but one misconception that can be cleared up is the idea that all modern countertenors sing entirely in falsetto, a lighter mechanism or way of producing higher pitches without engaging the full voice. If you listen to a modern professional countertenor singing opera, you will likely find that they are engaging their voice fully, and using a wide range of dynamics, tone colors, and expressive choices. Moreover, most singers who train the higher register of their voice so they can sing countertenor repertoire are also fully capable of singing in the lower tenor, baritone, and sometimes even bass registers, as well. Some countertenors may focus primarily on training their higher range, while others may choose to practice singing every note they have, from top to bottom. Operas of the Classical, Romantic, and 20th-century traditions rarely, if ever, included parts for countertenors. Some notable exceptions include Benjamin Britten’s operas A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1960) and Death in Venice (1973), Philip Glass’s Akhnaten (1983), and Jonathan Dove’s Flight (1998). Among new operas being written today, countertenor roles are becoming increasingly common, exploring a vast array of characters, settings, and dramatic possibilities. In fact, in BLO’s production of The Seasons – a new work that fuses Baroque music with a newly written libretto by a living playwright – you will hear not one, but two countertenors sing the roles of The Poet and The Painter!

Anthony Roth Costanzo and Kangmin Justin Kim, whose performances you will hear in The Seasons, are internationally known in the world of

opera. Some other popular countertenors include Jakub Józef Orliński, who sang at the opening ceremonies of the 2024 Summer Olympics; Philippe Jaroussky, who started as a violinist before turning to singing; and John Holiday, who has appeared on NPR’s Tiny Desk concert series and joined BLO’s cast of Mitridate earlier this season. But countertenor singing is not exclusive to opera – just ask Chris Colfer and Alex Newell of Glee fame!

By Annalisa Dias, Co-Founder of Groundwater Arts

“Sometimes, we feel the weather inside of us more than we feel the weather outside of us.”

—The Poet, The Seasons

In The Seasons, we’re invited on a journey through a complex tapestry of emotions that emerge when confronting how the climate crisis has fractured our relationship with land, time, and place. Together with the artists, we navigate through confusion, anger, despair, fear, overwhelm, activation, and… maybe eventually… a precarious and tender hope.

When faced with global inaction, it's natural to spiral into despair and even echo the performance artist's question: "Can we change?" The scale of destruction we face can feel paralyzing. Hope often feels out of reach. Recent research in psychology and sociology suggests a framework to understand our shared experience: "climate anxiety."

Here in Boston, climate anxiety intertwines deeply with environmental justice concerns. Communities like East Boston, Chelsea, and Roxbury bear disproportionate burdens of climate change impacts, from extreme heat due to fewer trees and more pavement, to flooding risks in low-lying areas. These same

neighborhoods have historically faced higher rates of air pollution from highways and industrial sites. Yet these communities are also at the forefront of climate resilience, with organizations like GreenRoots in Chelsea and Alternatives for Community & Environment (ACE) in Roxbury leading the fight for environmental justice, demonstrating how local action can create meaningful change.

Ask any climate scientist and they’ll tell you: we don’t have an information problem; instead, we have a crisis of imagination. We have the solutions necessary to mitigate the worst impacts of climate chaos, yet many of our stories about the futures we face due to climate change end in doom and gloom, dystopia, and apocalypse. Artists and storytellers can play a key role in shifting that narrative. It’s up to us to “feel the weather” inside of us and translate that into tangible action. As marine biologist, policy expert, and Urban Ocean Lab founder Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson asks: instead of existential disaster, “what if we get it right?”

If this conversation and terminology is new to you, here are a few helpful definitions and examples of where these concepts show up concretely here in Boston:

Environmental Justice: the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. For example, neighborhoods in Boston that were redlined — labeled risky investments because its residents were Black, immigrants, or Jewish — are “7.5°F hotter in the day, 3.6°F hotter at night, and have 20% less parkland and 40% less tree canopy than areas designated as A: Best,” according to the city’s 2022 Heat Resilience Plan.

Frontline Communities: communities who experience the “first and worst” impacts of the climate crisis. These communities are disproportionately Indigenous, Black, low income, coastal communities of color, migrant communities, and more. For example, the city of Boston was founded on unceded Native land, and Boston’s urban Indian community, while large and complex, frequently faces disproportionate negative community health impacts related to climate change.

Anxiety: distress about climate change and its impacts on the landscape and human existence. That can manifest as intrusive thoughts or feelings of distress about future disasters or the long-term future of human existence and the world, including one's own descendants. Boston Children’s Hospital has a Pediatric Environmental Health Center which provides medical treatment and care for young people experiencing the impacts of climate anxiety.

This show is a pastiche, a collection of music that has been specifically put together to illustrate a new story. We can’t talk about the intentions of the original composer, since this new production curates and combines his work in a wholly new way, but we can enjoy that skillful selection and combination of one wonderful piece by Vivaldi after another, especially in the solo playing of our wonderful orchestra leader, Annie Rabbat.

1 Chorus "Dell'aura al sussurrar": This is a wonderfully joyous 4-part chorus that listeners will recognize as the theme of Vivaldi's "Spring." This arrangement of the tune (with words expressing joy in springtime) came from Vivaldi's opera La Dorilla.

Now, listen to Vivaldi’s instrumental version of “Spring,” the first movement of The Four Seasons.

How does the version without words use tempo, dynamics, rhythm, pitch, and other musical elements to express the same excitement and energy?

2 Aria “Sento in seno” from Vivaldi’s Giustino: A plaintive aria about feeling sadness raining down in the soul. Listen to how Vivaldi uses pizzicato in the strings to evoke raindrops.

Can you think of other examples where a composer uses a specific instrumental technique to “paint a picture” of a specific thing or idea?

3

4

Aria “Se il cor guerriero” from Tito Manlio: This “rage" aria sung by a bass is a perfect example of Vivaldi's use of harmonic sequences to heighten dramatic tension – very similar to "Winter" in The Four Seasons. What else does Vivaldi do in this aria to build emotional intensity?

Trio “Aure placide, e serene” from La verità in cimento: A gorgeous trio for voices and strings that depicts serenity in nature. Listen to how the interweaving voices create a sense of ethereal stillness and beauty. How else does this piece convey calm and peacefulness?

• What instruments do you hear?

• How fast is the music? Are there sudden changes in speed? Is the rhythm steady or unsteady?

• Key/Mode: Is it major or minor? (Does it sound bright, happy, sad, urgent, dangerous?)

• Dynamics/Volume: Is the music loud or soft? Are there sudden changes in volume (either in the voice or orchestra)?

• What is the shape of the melodic line? Does the voice move smoothly, or does it make frequent or erratic jumps? Do the vocal lines move noticeably downward or upward?

• Does the type of voice singing (baritone, soprano, tenor, mezzo, etc.) have an effect on you as a listener?

• Do the melodies end as you would expect, or do they surprise you?

• How does the music make you feel? What effect do the factors above have on you as a listener?

• What is the orchestra doing in contrast to the voice? How do the two interact?

• What kinds of images, settings, or emotions come to mind? Does it remind you of anything you have experienced in your own life?

• Do particularly emphatic notes (low, high, held, etc.) correspond to dramatic moments?

• What type of character (romantic, comic, serious, etc.) fits this music?

BLO’s new Rising Waters / Rising Voices initiative for climate awareness

Boston’s Office of Climate Resilience

Boston’s Keeping Cool in the Heat

U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit

To Witness: A Proposal to Build Radical Trust across Difference in the Arts by Ronee Penoi (Laguna Pueblo/Cherokee) & Annalisa Dias

Catalyzing Climate Justice by Divesting from Fossil Fuels by Ronee Penoi (Laguna Pueblo/Cherokee) & Annalisa Dias, on behalf of Groundwater Arts

How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled by Laura Sullivan

All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis edited by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson

MIT Media Lab’s Future Worlds is an interdisciplinary project with the aim to combat climate change using new technologies. Explore the research projects and publications related to Future Worlds.

For Young People:

Climate Change Resources for Educators and Students

National Geographic Kids: 13 ways to save the Earth from climate change

ClassicFM’s “10 of Vivaldi’s greatest pieces of music”

ClassicFM’s “13 pieces of classical music inspired by birdsong”

PODCAST: Art Restart: Groundwater Arts

Heller, Karl. Antonio Vivaldi: The Red Priest of Venice. Trans. David Marinelli. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1997.

Kolneder, Walter. Antonio Vivaldi: His Life and Work. Trans. Bill Hopkins. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1970.

Pincherle, Marc. Vivaldi. Trans. Christopher Hatch. New York: Norton, 1957.

Scaramuccia. “New Discoveries of Vivaldi (2016).” https://scaramucciaensemble.com/en/newdiscoveries-of-vivaldi/ (2024), accessed 6 January 2025.

Talbot, Michael. Vivaldi. London: J.M. Dent, 1978.

White, Micky. Antonio Vivaldi: A Life in Documents. Florence: Olschki, 2013.

People have been telling stories through music for millennia throughout the world. Opera is an art form that is over 400 years old, with roots in Western Europe. Here is a brief timeline of its lineage.

Please note that all date ranges for these time periods are approximate, and notice that some even overlap.

1573 The Florentine Camerata was founded in Italy, devoted to reviving ancient Greek musical traditions, including sung drama.

1598 Jacopo Peri (1561-1633), a member of the Camerata, composed the world’s first opera –Dafne – reviving the classic myth.

1607 Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) wrote L’Orfeo, the first opera to become popular, marking him as the premier opera composer of his day and bridging the gap between Renaissance and Baroque music. His works are still performed today.

1637 The first public opera house, Teatro San Cassiano, was built in Venice, Italy.

1673 Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), an Italian-born composer, brought opera to the French court, creating a unique style, tragédie en musique, that better suited the French language. Blurring the lines between recitative and aria, he created fast-paced dramas to suit the tastes of French aristocrats.

1689 Henry Purcell’s (1659-1695) simple and elegant chamber opera, Dido and Aeneas, premiered at Josias Priest’s boarding school for girls in London.

1712 George Frederic Handel (16851759), a German-born composer, moved to London, where he found immense success writing intricate and highly ornamented Italian opera seria (serious opera). Ornamentation refers to stylized, fast-moving notes, usually improvised by the singer to make a musical line more interesting and to showcase their vocal talent.

1750s A reform movement, led by Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), rejected the flashy ornamented style of the Baroque in favor of simple, refined music to enhance the drama.

1805 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), although a prolific composer, wrote only one opera, Fidelio. The extremes of musical expression in Beethoven’s music pushed the boundaries in the late Classical period and inspired generations of Romantic composers.

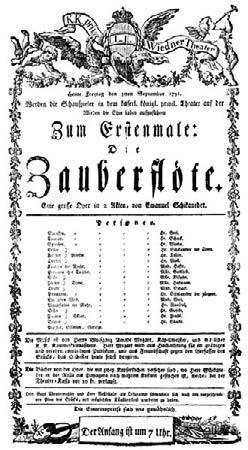

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) wrote his first opera at age 11, beginning his 25-year opera career. Mozart mastered and then innovated in several operatic forms. He wrote opera serias (serious operas), including La Clemenza di Tito; and opera buffas (comedic operas) like Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). He then combined the two genres in Don Giovanni, calling it dramma giocoso (comedic drama). Mozart also innovated the Singspiel, a German sung play featuring spoken dialogue, as in Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute).

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) composed Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), becoming the most prodigious opera composer in Italy by age 24. He wrote 39 operas in 20 years. A new compositional style created by Rossini and his contemporaries, including Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini, would, a century later, be referred to as bel canto (beautiful singing). Bel canto compositions were inspired by the nuanced vocal capabilities of the human voice and its expressive potential. Composers employed strategic use of register, the push and pull of tempo (rubato), extremely smooth and connected phrases (legato), and vocal glides (portamento).

1853 Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) completed La Traviata, a story of love, loss, and the struggle of average people, in the increasingly popular realistic style of verismo. Verdi enjoyed immense acclaim during his lifetime, while expanding opera to include larger orchestras, extravagant sets and costumes, and more highly trained voices.

1842 Inspired by the risqué popular entertainment of French vaudeville, Hervé (1825-1892) created the first operetta, a short comedic musical drama with spoken dialogue. Responding to popular trends, this new form stood in contrast to the increasingly serious and dramatic works at the grand Parisian opera house. Opéra comique as a genre was often not comic, tending to be more realistic or humanistic instead. Grand opera, on the contrary, was exaggerated and melodramatic.

1865 Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) Tristan und Isolde was the beginning of musical modernism, pushing the use of traditional harmony to its extreme. His massively ambitious, lengthy operas, often based in German folklore, sought to synthesize music, theatre, poetry, and visuals in what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). The most famous of these was an epic four-opera drama, Der Ring des Nibelungen, which took him 26 years to write and was completed in 1874.

1871 Influenced by French operetta, English librettist W.S. Gilbert (1836-1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) began their 25-year partnership, which produced 14 comic operettas, including The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Their works inspired the genre of American musical theatre.

Johann Strauss II, (1825-1899) influenced largely by his father, with whom he shared a name and talent, composed Die Fledermaus, popularizing Viennese musical traditions, namely the waltz, and further shaping operetta

1896

Giacomo Puccini’s (1858-1924) La bohème captivated audiences with its intensely beautiful music, realism, and raw emotion. Puccini enjoyed huge acclaim during his lifetime for his works.

1911 Scott Joplin, (1868-1917) “The King of Ragtime,” wrote his only opera, Treemonisha, which was not performed until 1972. The work combined the European lateRomantic operatic style with African American folk songs, spirituals, and dances. The libretto, also by Joplin, was written at a time when when African Americans in the southern United States rarely had access to literacy resources and education.

1927 American musical theatre, commonly referred to as Broadway, was taken more seriously after Jerome Kern’s (1885-1945) Show Boat, with words by Oscar Hammerstein II (1895-1960), tackled issues of racial segregation and the ban on interracial marriage in Mississippi.

Alban Berg (1885-1935) composed the first completely atonal opera, Wozzeck, dealing with uncomfortable themes of militarism and social exploitation. Wozzeck is in the style of 12-tone music, or serialism. This new compositional style, developed in Vienna by composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), placed equal importance on each of the 12 pitches in a chromatic scale (all half steps), removing the sense of the music being in a particular key.

British composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) gained international recognition with his opera Peter Grimes. Britten, along with Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), was one of the first British opera composers to gain fame in nearly 300 years.

John Adams (b. 1947) composed one of the great minimalist operas, Nixon in China, the story of Nixon’s 1972 meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong. Musical minimalism strips music down to its essential elements, usually featuring a great deal of repetition with slight variations.

1935 American composer George Gershwin (1898-1937), who was influenced by African American music and culture, debuted his opera, Porgy and Bess, in Boston, MA with an allAfrican American cast of classically trained singers. His contemporary, William Grant Still (1895-1978), a master of European grand opera, fused that with the African American experience and mythology. His first opera, Blue Steel, premiered in 1934, one year before Porgy and Bess.

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), known for synthesizing musical genres, brought together the best of American musical theatre, opera, and ballet in West Side Story, a reimagining of Romeo and Juliet in a contemporary setting.

Anthony Davis (b. 1951) premiered his first of many operas, X: The Life and Time of Malcom X, which reclaims stories of Black historical figures within the theatre space. He incorporated both the orchestral and vocal techniques of jazz and classical European opera in his score for a distinctly American sound, and a fully realized vision of how jazz and opera are in conversation within a work.

Still a vibrant, evolving art form, opera attracts contemporary composers such as Philip Glass (b. 1937), Jake Heggie (b. 1961), Terence Blanchard (b. 1962), Ellen Reid (b. 1983), and many others. Composers continue to be influenced by present and historical musical forms in creating new operas that explore current issues or reimagine ancient tales.

Opera is unique among forms of singing in that singers are trained to be able to sing without amplification, in large theaters, over an entire orchestra, and still be heard and understood! This is what sets the art form of opera apart from similar forms such as musical theatre. To become a professional opera singer, it takes years of intense physical training and constant practice — not unlike that of a ballet dancer — to stay in shape. Poor health, especially respiratory issues and even allergies, can be severely debilitating for a professional opera singer. Let’s peek into some of the science of this art form.

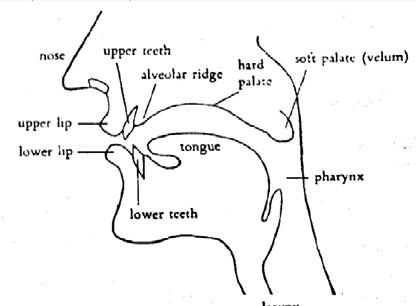

Singing requires different parts of the body to work together: the lungs, the vocal cords, the vocal tract, and the articulators (lips, teeth, and tongue). The lungs create a flow of air over the vocal cords, which vibrate. That vibration is amplified by the vocal tract and broken up into words by consonants, which are shaped by the articulators.

Any good singer will tell you that good breath support is essential to produce quality sound. Breath is like the gas that goes into your car. Without it, nothing runs. In order to sing long phrases of music with clarity and volume, opera singers access their full lung capacity by keeping their torso elongated and releasing the lower abdomen and diaphragm muscles, which allows air to enter into the lower lobes of the lungs. This is why we associate a certain posture with opera singers. In the past, many operas were staged with singers standing in one place to deliver an entire aria or scene, with minimal activity. Modern productions, however, often demand a much greater range of movement and agility onstage, requiring performers to be physically versatile, and bringing more visual interest, authenticity of expression, and nuanced acting into the storytelling.

If you run your fingers along your throat, you will feel a little lump just underneath your chin. That is your “Adam’s Apple,” and right behind it, housed in the larynx (voice-box), are your vocal cords. When air from the lungs crosses over the vocal cords it creates an area of low pressure (Google The Bernoulli Effect), which brings the cords together and makes them vibrate. This vibration produces a buzz. The vocal chords can be lengthened or shortened by muscles in the larynx, or by changing the speed of air flow. This change in the length and thickness of the vocal cords is what allows singers to create different pitches. Higher pitches require long, thin cords, while low pitches require short, thick ones. Professional singers take great pains to protect the delicate anatomy of their vocal cords with hydration and rest, as the tiniest scarring or inflammation can have noticeable effects on the quality of sound produced.

Without the resonating chambers in the head, the buzzing of the vocal cords would sound very unpleasant. The vocal tract, a term encompassing the mouth cavity, and the back of the throat, down to the larynx, shapes the buzzing of the vocal cords like a sculptor shapes clay. Shape your mouth in an ee vowel (as in eat), then sharply inhale a few times. The cool sensation you feel at the top and back of your mouth is your soft palate. The soft palate can raise or lower to change the shape of the vocal tract. Opera singers often sing with a raised soft palate, which allows for the greatest amplification of the sound produced by the vocal cords. Different vowel sounds are produced by raising or lowering the tongue, and changing the shape of the lips. Say the vowels: ee, eh, ah, oh, oo and notice how each vowel requires a slightly lower tongue placement and slightly rounder lips. This area of vocal training is particularly difficult because none of the anatomy is visible from the outside!

The lips, teeth, and tongue are all used to create consonant sounds, which separate words into syllables and make language intelligible. Consonants must be clear and audible for the singer to be understood. Because opera singers do not sing with amplification, their articulation must be particularly good. The challenge lies in producing crisp, rapid consonants without interrupting the connection of the vowels (through the controlled exhalation of breath) within the musical phrase.

Perfecting every element of this complex singing system requires years of training and is essential for the demands of the art form. An opera singer must be capable of singing for hours at a time, over the powerful volume of an orchestra, in large opera houses, while acting and delivering an artistic interpretation of the music. It is complete and total engagement of mental, physical, and emotional control and expression. Therefore, think of opera singers as the Olympic athletes of the stage, sit back, and marvel at what the human body is capable of!

Opera singers are cast into roles based on their tessitura (the range of notes they can sing comfortably). There are many descriptors that accompany the basic voice types, but here are some of the most common ones:

The lowest voice, basses often fall into two main categories: basso buffo, which is a comic character who often sings in lower laughing-like tones, and basso profundo, which is as low as the human voice can sing! Doctor Bartolo is an example of a bass role in The Barber of Seville by Rossini.

A middle-range lower voice, baritones can range from sweet and mild in tone, to darker dramatic and full tones. A famous baritone role is Rigoletto in Verdi’s Rigoletto. Baritones who are most comfortable in a slightly lower range are known as Bass-Baritones, a hybrid of the two lowest voice types.

The highest of the lower-range voices, tenors often sing the role of the hero. One of the most famous tenor roles is Roméo in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. Sometimes, singers with lower-range voices also cultivate much higher ranges, singing in a range similar to a mezzo-soprano or soprano by using their falsetto register. Called the Countertenor, this voice type is often found in Baroque music. Countertenors replaced castrati in the heroic lead roles of Baroque opera after the practice of castration was deemed unethical.

Each of the voice types (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, baritone, bass) also tends to be sub-characterized by tone descriptors such as “lyric” or “dramatic.” Lyric singers tend toward smooth lines in their music, sensitively expressed interpretation, and flexible agility. Dramatic singers have qualities that are attributed to darker, fuller, richer note qualities expressed powerfully and robustly with strong emotion. While it’s easiest to understand operatic voice types through these designations and descriptions, one of the most exciting things about listening to a singer perform is that each individual’s voice is essentially unique, so each singer will interpret a role in an opera in a slightly different way.

The lowest of the higher treble voices has a low range that overlaps with the highest tenor’s range. This voice type is less common.

Somewhat equivalent to an alto role in a chorus, mezzo-sopranos (mezzo meaning “middle”) are known for their full and expressive qualities. While they don’t sing frequencies quite as high as sopranos, their ranges do overlap, and it is a “darker” tone that sets them apart. One of the most famous mezzo-soprano lead roles is Carmen in Bizet’s Carmen

The highest voice. Some subtypes of the soprano voice include coloratura, lyric, and dramatic sopranos. Coloratura sopranos specialize in being able to sing fast-moving notes that are very high in frequency, often referred to as “color notes.” One of the most famous coloratura roles is the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

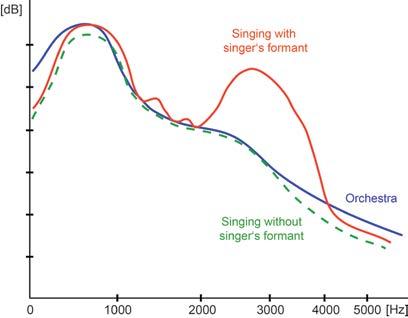

What is it about opera singers that allows them to be heard above the orchestra? It’s not that they simply singing louder. The qualities of sound have to do with the relationship between the frequency (pitch) of a sound, represented in a unit of measurement called hertz, and its amplitude, measured in decibels, which the ear perceives as loudness. Only artificially produced sounds, however, create a pure frequency and amplitude (these are the only kind that can break glass). The sound produced by a violin, a drum, a voice, or even smacking your hand on a table, produces a fundamental frequency as well as secondary, tertiary, etc. frequencies known as overtones, or as musicians call them, harmonics

The orchestra tunes to a concert “A” pitch before a performance. Concert “A” has a frequency of about 440 hertz, but that is not the only pitch you will hear. Progressively softer pitches above that fundamental pitch are produced in multiples of 440 at 880hz, 1320hz, 1760hz, etc. Each different instrument in the orchestra, because of its shape, construction, and mode in which it produces sound, produces different harmonics. This is what makes a violin, for example, have a different color (or timbre ) from a trumpet. Generally, the harmonics of the instruments in the orchestra fade around 2500hz. Overtones produced by a human voice—whether speaking, yelling, or singing— are referred to as formants

As the demands of opera stars increased, vocal teachers discovered that by manipulating the empty space within the vocal tract, they could emphasize higher frequencies within the overtone series—frequencies above 2500hz. This technique allowed singers to perform without hurting their vocal cords, as they are not actually singing at a higher fundamental decibel level than the orchestra. Swedish voice scientist Johan Sundberg observed this phenomenon when he recorded the world-famous tenor Jussi Bjoerling in 1970. His research showed multiple peaks in decibel level, with the strongest frequency (overtone) falling between 2500 and 3000 hertz. This frequency, known as the singer’s formant , is the “sweet spot” for singers so that we hear their voices soaring over the orchestra into the opera house night after night.

that are specific to each particular

like a

When two people sing the same note simultaneously, the high overtones allow your ear to distinguish two voices.

The final piece of the puzzle in creating the perfect operatic sound is the opera house or theater itself. Designing the perfect acoustical space can be an almost impossible task, one which requires tremendous knowledge of science, engineering, and architecture, as well as an artistic sensibility. The goal of the acoustician is to make sure that everyone in the audience can clearly understand the music being produced onstage, no matter where they are sitting. A perfectly designed opera house or concert hall (for non-amplified sound) functions almost like gigantic musical instrument.

Reverberation is one key aspect in making a singer’s words intelligible or an orchestra’s melodies clear. Imagine the sound your voice would make in the shower or a cave. The echo you hear is reverberation caused by the large, hard, smooth surfaces. Too much reverberation (bouncing sound waves) can make words difficult to understand. Resonant vowel sounds overlap as they bounce off hard surfaces and cover up quieter consonant sounds. In these environments, sound carries a long way but becomes unclear or — as it is sometimes called — wet, as if the sound were underwater. Acousticians can mitigate these effects by covering smooth surfaces with textured materials like fabric, perforated metal, or diffusers, which absorb and disperse sound. These tools, however, must be used carefully, as too much absorption can make a space dry — meaning the sound onstage will not carry at all and the performers may have trouble even hearing themselves as they

perform. Imagine singing into a pillow or under a blanket.

The shape of the room itself also contributes to the way the audience perceives the music. Most large performance spaces are shaped like a bell – small where the stage is and growing larger and more spread out in every dimension as one moves farther away. This shape helps to create a clear path for the sound to every seat. In designing concert halls or opera houses, big decisions must be made about the construction of the building based on acoustical needs.

Even with the best planning, the perfect acoustic is not guaranteed, but professionals are constantly learning and adapting new scientific knowledge to enhance the audience’s experience.

You will see a full dress rehearsal – an insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera premieres. The singers will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and an orchestra will accompany the singers, who may choose to “mark,” or not sing in full voice, to save their voices for the performances. A final dress rehearsal is often a complete run-through, but there is a chance the director or conductor will ask to repeat a scene or section of music. This is the last opportunity the performers have to rehearse with the orchestra before opening night, and they therefore need this valuable time to work. The following will help you better enjoy your experience of a night at the opera:

• Arrive on time! Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks in the performance and often not until intermission.

• Dress in what you are comfortable in so you can enjoy the performance. For some, that may mean dressing up in a suit or gown; for others, jeans and a t-shirt is fine. Generally, “dressycasual” is what people wear. Live theatre is usually a little more formal than a movie theater.

• At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra will ask the oboist to play the note “A.” You will hear all the other musicians in the orchestra tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. You can applaud to welcome them!

• Feel free to applaud or shout "Bravo!" at the end of an aria or chorus piece if you really liked it. The end of a piece can usually be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• It’s OK to laugh when something is funny or gasp at something shocking!

• When translating songs, and poetry in particular, much can be lost due to a change in rhythm, inflection, and rhyme of words. For this reason, opera is usually performed in its original language. In order to help audiences enjoy the music and follow every twist and turn of the plot, English supertitles are projected. Even when the opera is in English, there are still supertitles.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, pay attention to repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

The singers, orchestra, dancers, and stage crew are all hard at work to create an amazing performance for you! Here’s how you can help them.

• Lit screens are very distracting to the singers, so please keep your phone off and out of sight until the house lights come up.

• Due to how distracting electronics can be for performers, taking photos or making audio or video recordings is strictly forbidden.

The theater is a shared space, so please be courteous to your neighbors!

• Please do not take off your shoes or put your feet on the seat in front of you.

• Respect your fellow opera lovers by not leaning forward in your seat so as to block the person’s view behind you.

• Do not chew gum, eat, or drink while the rehearsal is in session. Not only can it pull focus from the performance, but the ushers are not there to clean up after you.

• If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly.

Otherwise, sit back, relax, and let the action onstage pull you in. As an audience member, you are essential to the art form of opera — without you, there is no show!

Have Fun and Enjoy the Opera!