a certain anomaly

giving the deviant ‘institute’ Landbouwbelang a future in Maastricht

giving the deviant ‘institute’ Landbouwbelang a future in Maastricht

Master of Architecture Academie van Bouwkunst

Committee: Machiel Spaan Milad Pallesh Christoper de Vries

Added members exam: Jarrik Ouburg Lisette Plouvier

A certain anomaly February 2022

Art Kallen

32

Collective history

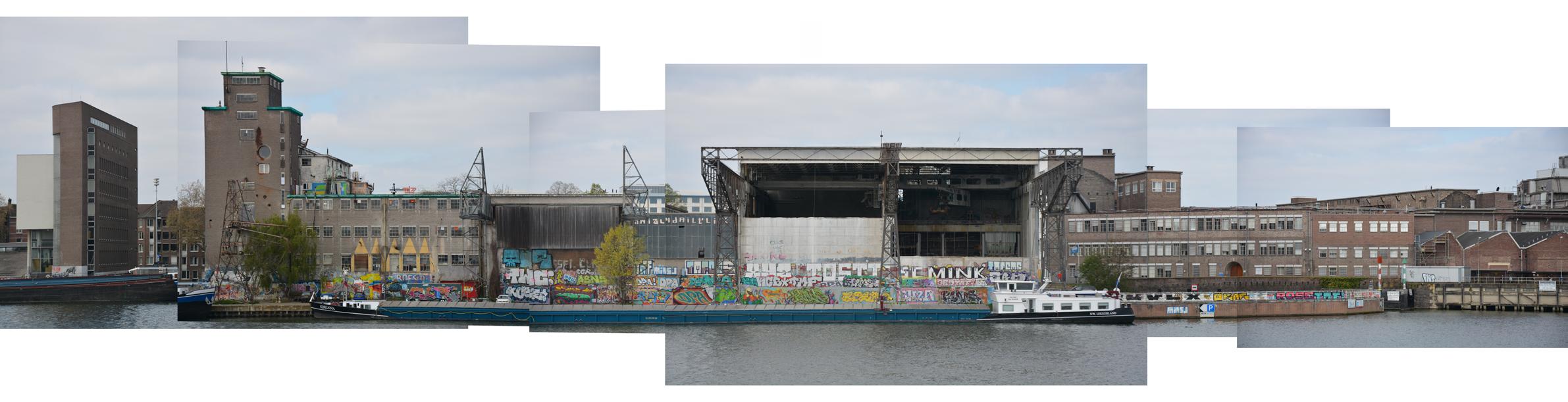

After thirty years of vacancy Landbouwbelang was squatted in 2002 and since that time has been built up towards an institute for alternative culture in Maastricht.

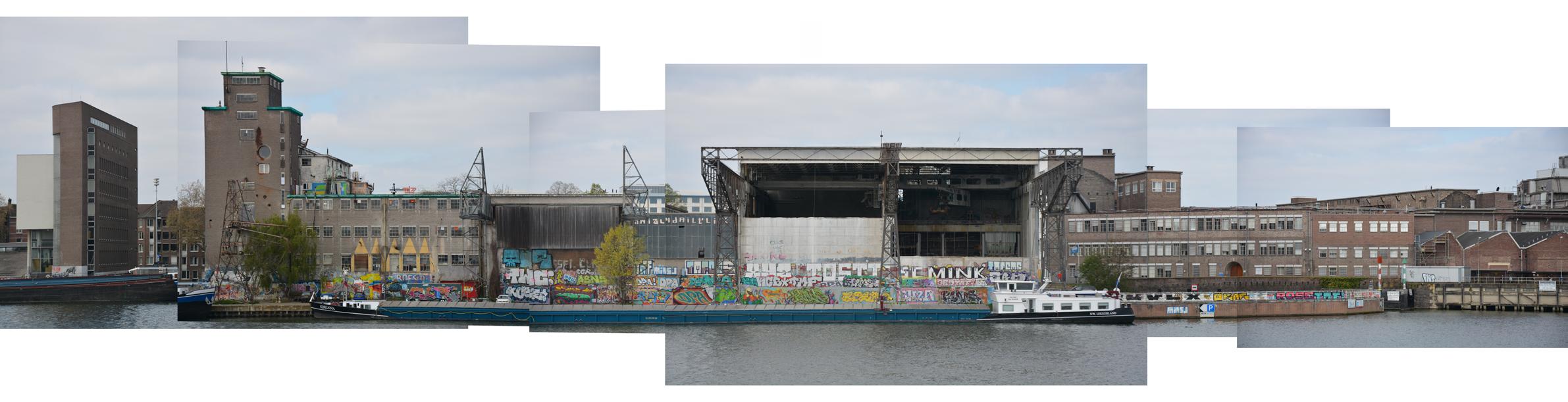

These days Landbouwbelang’s ensemble of buildings has come to represent a collective history of Maastricht which reaches further than the squat of the past twenty years. The site and its buildings show how the squatters community has granted a function to the vacant industrial monument. In addition, it shows that the place has been used as a cargo location of the original agricultural cooperation Landbouwbelang for years. It shows that the northern part belonged to the paper factory. Moreover, it shows how Landbouwbelang was positioned on an island between the river Maas and the canal Luik-Maastricht, with the lockkeepers houses as relics of that time.

Underneath all of these histories, we find historical layers which are not directly tangible. For five hundred years, this place housed the Sint-Antonietenklooster, situated right on the edge of Maastricht against the city wall. The squatting, the industrial activity and the monastic life which took place at the Landbouwbelang site all have in common that they deviated from the surrounding life at that time. In the very centre of the urban tissue of Maastricht, the Landbouwbelang site has always been a bastion that accommodated a tradition of subculture. It represents an alternative way of living that is in contrast with the Leitkultur: `het sjiek en sjoen’. It is an anomaly in Maastricht, but not ‘just’ a certain anomaly.

Redevelopment

The current tender leaves no room to maintain the embodied variegation of the site in the future. In the tender, the building ensemble is

placed within a financial logic of a larger area development. Thereby it is depriving the location of her autonomy and in turn is neglecting her unique role in the city. The financial conditions dictate a redevelopment that in practice can only been found in a very voluminous and pragmatic housing programme. Market conformity will be leading, thereby irrevocably ending this piece of collective history.

Alternative future

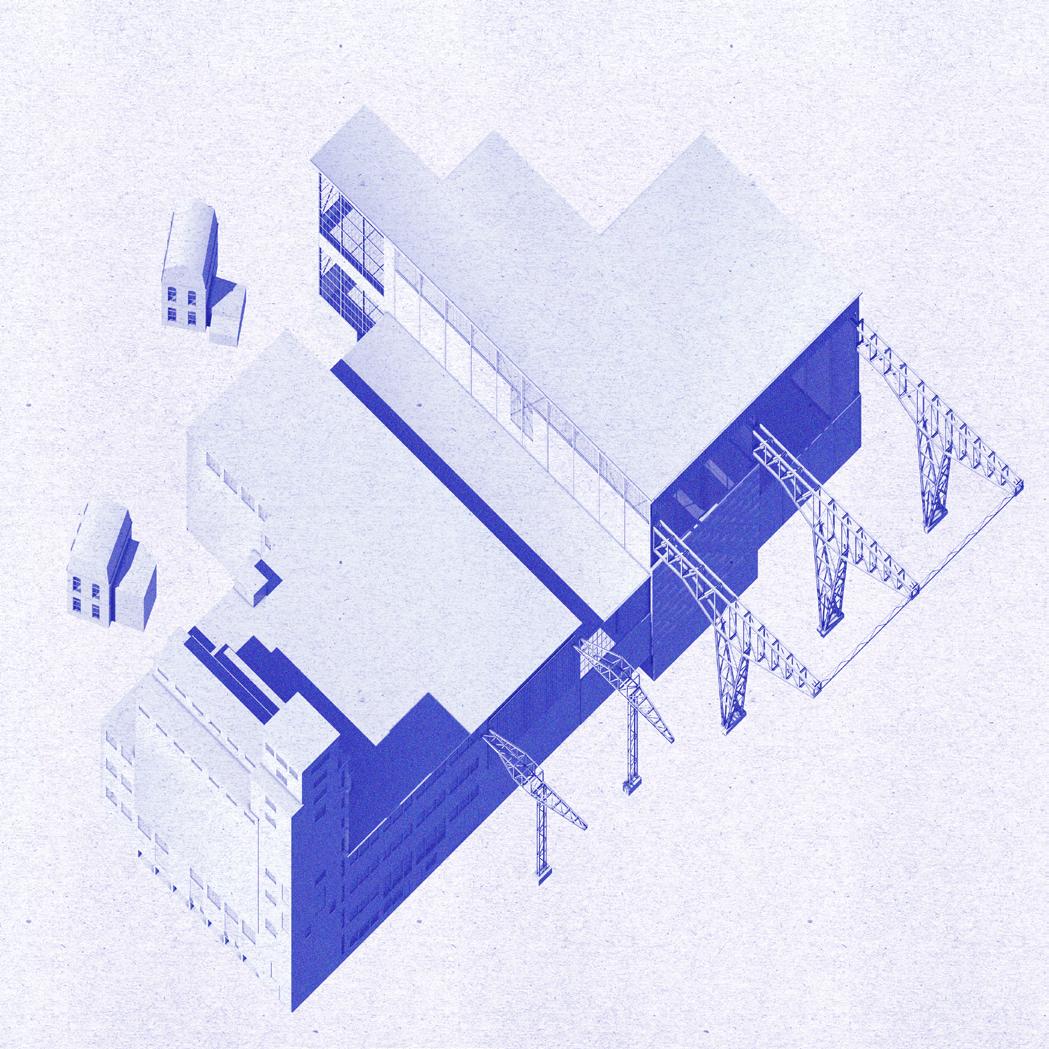

The imminent redevelopment motivates this design of an alternative future. In this project I value the existing buildings and the history they entail. And I draw parallels between the existing use and the historical uses on site. Next to the current use of Landbouwbelang and the rooted value this has for an alternative culture in Maastricht, the parallel with history makes apparent how the current subcultural identity is engrained in the history of the site. At this crossroads for the site of Landbouwbelang, but also at this crossroads for Maastricht, this design shows a way to make the development of Landbouwbelang an acknowledgement of the value of the existing city and its histories. In the design I reuse large parts of the existing buildings to both expand on existing programme and add new functions. By making interventions to the primarily concrete casco, I intensify existing functions and add special housing conditions. These are housing conditions of a collective nature that mirror the history of both the life in the squatting community and the monastery. In this way, a future is created where preservation and new construction are interwoven to show the layered history of this site, while making space for contemporary users to add a new layer. A new layer that respects the tradition of subculture as a contrasting addition to the city centre of Maastricht.

54

...there is another type of human right that should challenge the neoliberal market logics: the right to the city. [...]The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.

[...]This right is not only a right of access defined by the property speculator or state planners, but an active right to make the city different, to shape it more in accord with our heart’s desire.

David Harvey

76

Harvey, D. (2003) The Right to the City. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 27, nr. 4. p. 939-941

collective history

98

1110

At the dawn of the nineties I was born in Maastricht just on the Eastern bank of the Maas river. At 4 years old we moved two streets further to a house that overlooked the Maas looked out over De Griend, a former island in the middle of the Maas that was made part of the Eastern mainland in 1895. Although we lived in the city we played a lot outside because we had De Griend right across from our house. When I looked a bit further than De Griend and gazed to the other side of the river I saw an unearthly big building. A building rising from the hard cay in the water with its concrete foundation. Towering on top of that foundation stood two cranes hanging above the streaming water. The cranes emerged from a building which seemed to be provisionally closed off with mortared concrete blocks on the lower part of the building, above that a gaping hole revealing a dark steel structure. The building had an ominous presence, how it stood there

gazing over the grey glistening water. Little did I know that I would be dancing in one of the tiny basements of the building 20 years later.

When I moved to another part of the town I did not get to see the building as often anymore, although the impression of it remained. But in the time that I turned my attention away from the building I so often wondered about what it housed, it was brought back to life. The agricultural cooperative ‘Landbouwbelang’ built this particular building in 1939 to store large amounts of grain. For years it was in use as a node between land transport and boat transport. But in the seventies, the warehouse was abandoned and the building obtained by the adjacent paper mill. Although the paper factory never gave a new purpose to the Landbouwbelang building. This was exactly the period of time I registered this dark colossus standing vacant from my bedroom window.

1312

1514

Landbouwbelang in 1950

Landbouwbelang in 1983

1716

Landbouwbelang in current times

1918

Sphinxkwartier

Muziekgieterij

Pathe Lumiere

Bureau Europa

SAPPI

2120

2322 1939: start construction 1946: Landbouwbelang in action 27y 1973: Landbouwbelang discontinued 29y 18y 2002: Landbouwbelang squatted 2020: future? 1994: my bedroom view

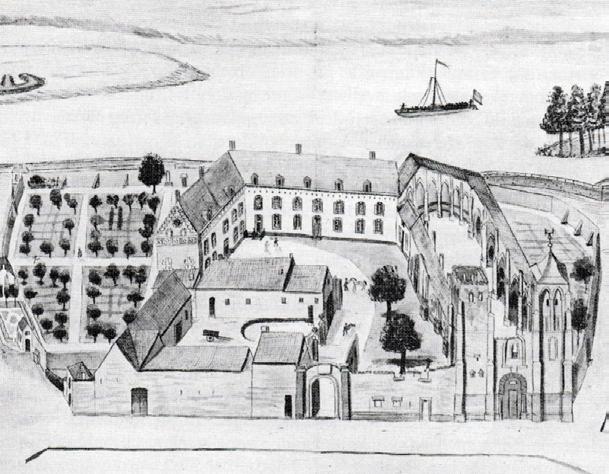

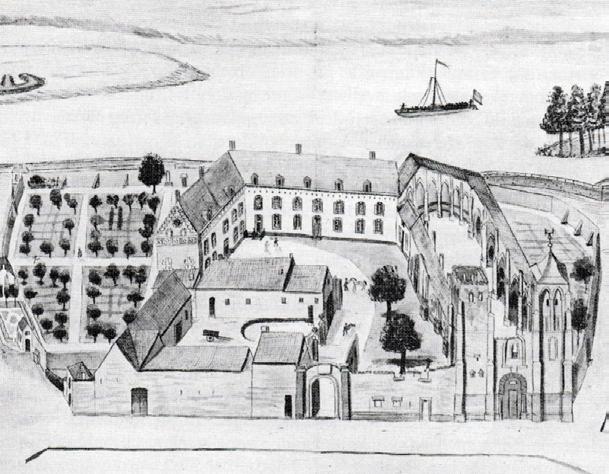

Sint Antonietenklooster (monastery)

1250 - 1794

From 1250 until 1780 the site has been a monastery for the order of the Antonieten. The monastery died a silent dead and in 1790 the monastery was sold to a private person.

After a French siege in 1794 the monastery was unrepairably damaged and afterwards it was torn down.

As a monastery the site has been a very secluded place in the city for centuries. It was at the edge of the city, just inside the city walls. The monastery by definition had an inward focus.

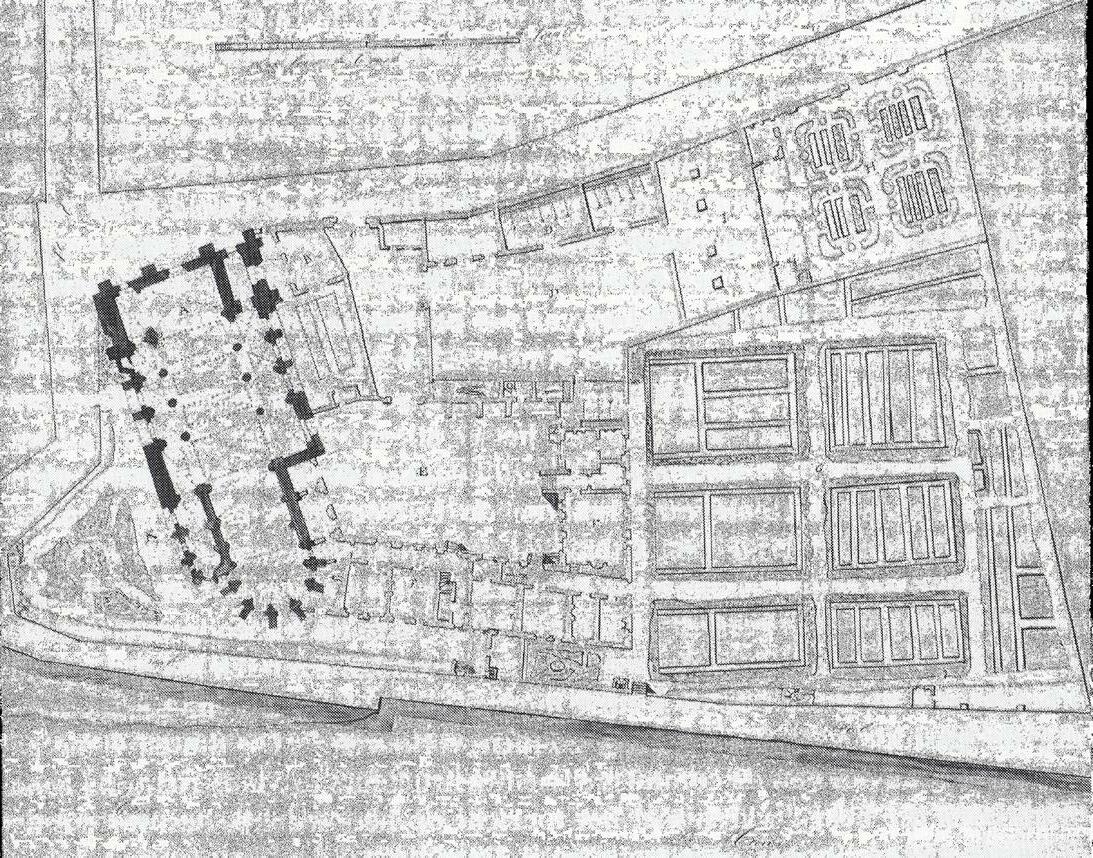

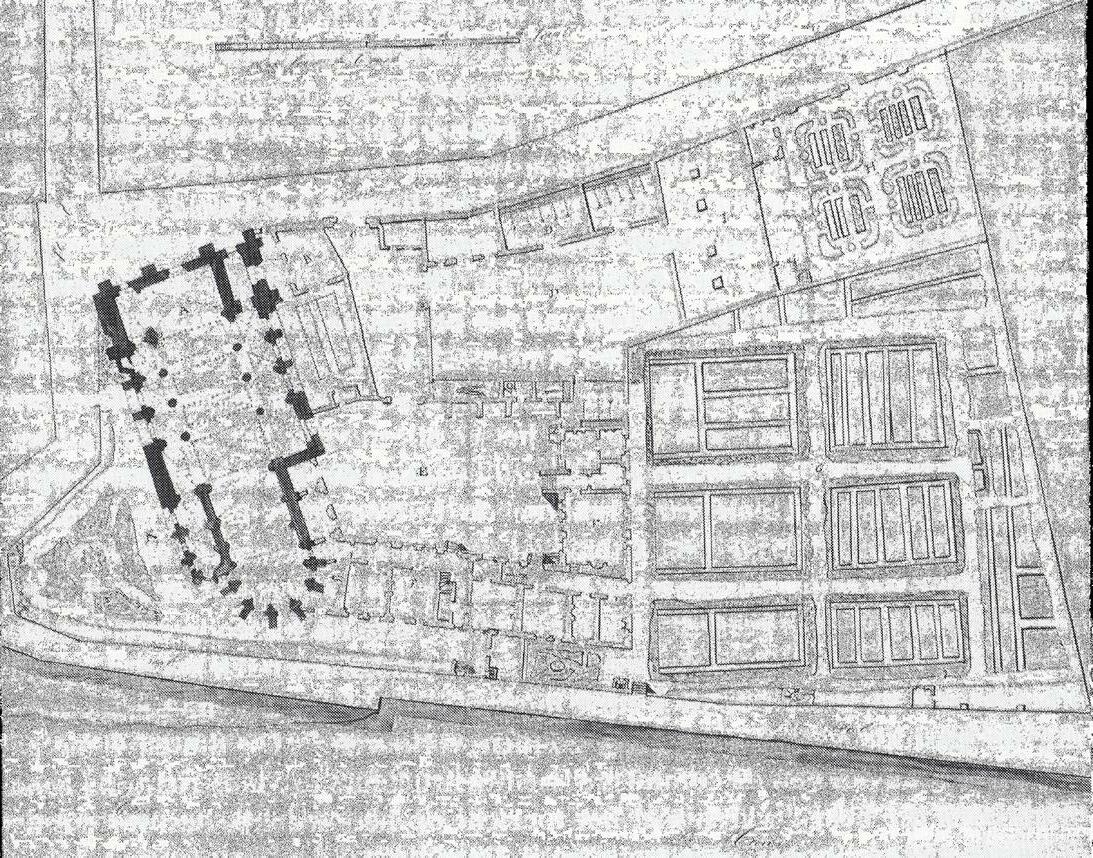

Kanaal Luik-Maastricht

1846 - 1967

In 1846 a channel between Luik and Maastricht was created. This connection lead straight past the Maas through the center of Maastricht. It’s main function was to make transport between the two cities more efficient and quick.

The digging of the channel meant for the site of Landbouwbelang that it created a certain island. When Landbouwbelang was built in 1939 the site was a dilapitaded island disconnected from the city. In between the locks past the paper factory, the Maas and the Luik-Maastricht channel.

Landbouwbelang

1967-current

At the end of the 1960s the channel was closed again to make space for the next infrastructural function. The channel became a big car road to connect north and south of the city. This has left the site of Landbouwbelang still disconnected from the city.

That urban condition played its part in letting the squat that occupied Landbouwbelang after its vacancy, grow into an enclave.

2524

2726 Sint Antonietenklooster 1250 - 1794 1846 - 1967 1967 - current Kanaal Luik-Maastricht Landbouwbelang site history

redevelopment

2928

one undeniable future

3130

LBB squat 18y 2020 plan belvedere centre plan belvedère 0,8km 1,6km 2,4km 3,2km 4,0km 4,8km 5,6km 6,4km 7,2km 8,0km

development

The expansion of the city centre that is entailed in the Belvedère plan leads to a deciding moment in Maastricht, a city with a community that is just as exclusive as it is inclusive. Over time an entity has come into existence just next to the city centre, that has deviant relationship with the city and its community: Landbouwbelang. This anomaly could exist in the lee of the city centre. But now the centre is expanding, this entity is not in the perifery anymore and garners a lot of attention.

3332

centre

plan belvedère

deviant energy in the city

3534

3736

“to look at the world from an estranged point of view is to rediscover and reinvent it”

reinventing

The redevelopment of Landbouwbelang reveals a tensed choice within city and community. This crossroads dips deep into the identity of the city and the community. Landbouwbelang and its future put Maastricht’s leitkultur right opposite the ‘otherness’ in the city.

Maastricht knows a tradition of rational architecture. A tradition that has reached its peak in the redevelopment of the Ceramique quarters in the 90’s. It is an architectural tradition appropriated by the ‘sjiek en sjoen’ -the leading class- from Maastricht and that fits flawlessly into the smooth city.

The use of Landbouwbelang by the squatters puts an alternative view opposite this. It is an architectural approach that is headstrong and does not adhere to common standards. One that constructs and deconstructs. One that progressively builds and appropriates a reality that fits the desires of the users. This approach challenges our perception of the norm.

In that it is pedagogical and emancipatory, like the axonometric drawings (Prouns) of the constructivist artist and architect El Lissitzky:

by looking at the world from an estranged point of view is to rediscover and reinvent them.

Now there is a choice for Maastricht to either learn from the point of view of the squatters and reinvent a part of Maastricht, or to go along in a tradition of rationalism that leads over a path well known in the city: the generic, smooth city.

It is a chance to maintain an untraditional thinking in the city, a way of thinking that the city houses so very little.

But why would you choose for a counter culture perspective. What does it add to the city that makes it valuable? How does a counter culture benefit the city?

Why choose for counter culture instead of the ‘smooth city’?

3938

qualities

Landbouwbelang has brought and developed several qualities that Maastricht houses very little

LBB verdiepingen

big hall

LBB verdiepingen

‘t keldertje grote kelder landhuis/treehouse

SPACES year month week

SPACES year month week

big hall

‘t keldertje grote kelder landhuis/treehouse

mindful

making

foodbank social

mindful

making

foodbank social

cultural

entertainment

educational eating environmental living

art

art

cultural

entertainment

educational eating environmental living

NL’se dansdagen

NL’se dansdagen

fashionclash

fashionclash

cirque du platzak

cirque du platzak

workspaces aurora yoga workspaces ateliers kaleido

workspaces aurora yoga workspaces ateliers kaleido

demotech kom eten

open mic repair cafe skatecafe

open mic repair cafe skatecafe

plata morgana maastricht goes vegan

plata morgana maastricht goes vegan

demotech kom eten

boardgame club kaleido transport artspace foodbank

boardgame club kaleido transport artspace foodbank

4140

music Nederlandse dansdagen

skate

4342

open ateliersdebates

performance - cirque platzak

4544

sjiek en sjoen TEFAF het Parcours Preuvenemint Andre Rieu Bonnefanten Marres Bureau Europa Ainsi Theater ah Vrijthof Museum ah Vrijthof Bordenhal theater Muziekgieterij alternative

Landbouwbelang fashionclash cirque du platzak plata morgana

Maastricht soft tissue

ainsi bonnefanten museum bureau europa

marres

kumulus

transport artspace big hall expo open ateliers

museum ah vrijthof complex

muziekgieterij

theater ah vrijthof

avb maastricht jan van eijck

conservatorium MECC

‘t keldertje werkruimte toneelacademie

podiumBG weggeef winkel community restaurant

workshops

big hall podiumBG mandril bankastudio’s

stadsnomadedemotech S A M s t

maastr cht

kunstacademie

universiteit maastricht

toneelacademie zuyd hogeschool

het werkgebouw

ichtingateliers

batterijstr 48 ainsi collective workspace maastricht

4746

regional amenities

Eindhoven (70km)

(25km)

(70km)

(25km)

(20km) Kerkrade (25km)

(30km)

4948

Venlo

Aachen

Heerlen

Maastricht Luik

Hasselt

Genk(20km) sectie-C plan B NRE-terrein Stroomhuisje Campina -terrein Vonk Hasselt Landbouwbelang Bankastudio’s het Werkgebouw Mandril Ravi Liege Les Ateliers Dony Espace 251 Nord La Comete Nunzig Freitag1830 Carbon6 Q4 van Abbemuseum TAC MU heheh jjemm klene Z33 Bonnefanten Bureau Europa Marres B32 AINSI La Boverie Les Brasseurs Ludwig Forum Centre Charlemagne Suermondt Ludwig Schunck Nieuwe Nor Limburg museum Cmine Cube subsidised cultural institutes bottom-up/alternative cultural venues + creative hubs focus barrier

an alternative future

5150

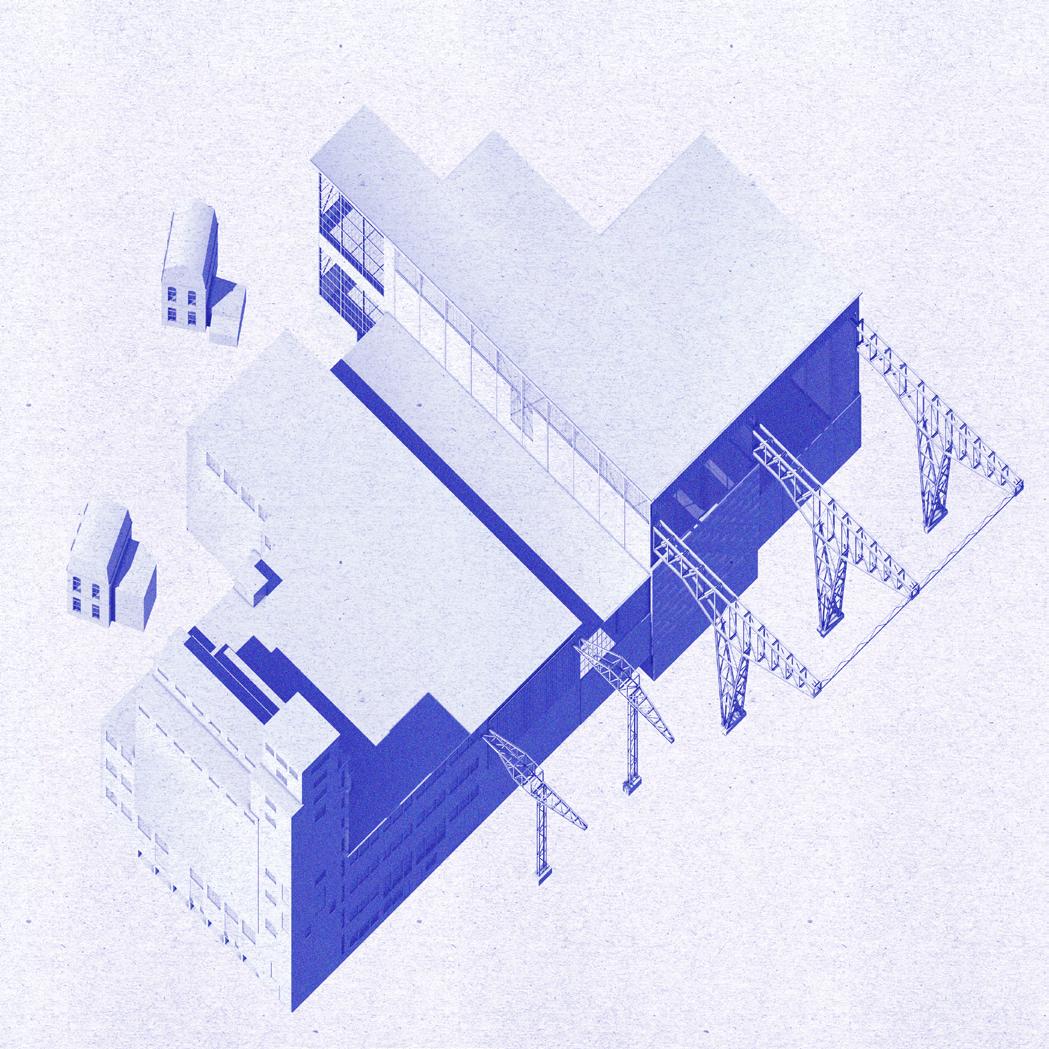

approach

The redevelopment of Landbouwbelang can, for the sake of the city, not be seen as a tabula rasa project in which the existing is erased as if it never were. For the urban life, the alternative culture and the collective history of Maastricht it holds too much value. Even for the regional network it holds a strong position in the cultural scene.

But the fact that it houses a lot of functions, does not mean it attracts a diversity of people. The leading ‘habitus’ revolves around people with an alternative lifestyle.

The project acknowledges the historical layers and the value of Landbouwbelang in its approach. The aim of the project is to intensify the use of the site as to bring in a new group of actors. This diversifies the users of the site and connects Landbouwbelang to a bigger audience.

Instead of starting with a carte blanche, the intensification of the use of site is pursued by extending the programme and building on the existing atmosphere.

In short the approach is continuing the engrained history of the site.

collective history

engrained history

5352

added layer

Years went by before I got to experience Landbouwbelang from up close. The building is situated on a triangular plot outside of the normal routes through the city. It is situated a little behind a busy car road with a big crash barrier. A crash barrier with plastic reflecting panels on top of it, so the view from the car on Landbouwbelang is obscured. The other two sides are hard cays standing firmly in the water. Even in its location, it seems to be deviant from the standard, maybe that is one of the reasons that it has been able to survive for 18 years.

When I finally did visit Landbouwbelang my imagination had mystified the image of the place already. A monastery of bygone times

in which alternative monks live a life I could only dream of living. Was it as mysterious and perfectly alternative as I thought it would be? I think that it is. It is rough, it is a bit messy, I felt a bit out of place. The carcasses of buildings that once were, give a special mysterious touch to the place. Especially considering the orderliness of the centre of Maastricht, Landbouwbelang exposes a great contrast. But it shows as well a part of the history of Maastricht. A history that does not revolve around shopping and tourism, but a history of labour and industry. A rough history that these days is polished and polished, until the memory of this history becomes a more spotless version than it has ever been.

5554

engrained history

Sint-Antonietenklooster (1250-1794)

projection over current situation

Sint-Antonietenklooster around 1744

5756

collectivity in monastery

public private

collective

5958

collectivity in current Landbouwbelang

individual living cells

public

individual living cells big hall + rest space

private collective

collective kitchen/dining

individual living cells

6160

mentality

The interplay between collectivity, privacy and public life in Landbouwbelang has been built up by gradually appropriating a seemingly uninhabitable building. By simultaneously inhabiting and appropriating the building, the squatters needed a pragmatic attitude towards the build up of the private, collective and public spaces. As René Boer (2020) states it their way of live materialises in the emerging architecture, which creates a strong and grounded connection to the building

The engrained history of the site unfolds a collective identity of the site, that follows from a similarity in lifestyle of monks and squatters. Also the squatter’s mentality of a pragmatic and solution driven architecture follows from the research on-site.

The alternative future I am proposing for Landbouwbelang takes this squatter’s mentality to guide several interventions on the existing building. Interventions that experiment with this pragmatic attitude and induce further experiments on the architecture proposed.

There is one objective within all these experiments: they have to contribute to the public, collective or private life happening on site

Boer, R. (2020) The architecture of squatting, p. 177 in: ReWriting Architecture. 10+1 actions. Amsterdam: Valiz

making the industrial structure habitable

new openings to provide an outward connection for the individual living units

6362

I guess I had never imagined I would meet the people from Landbouwbelang in the way I did now. Seeing the building across from the river as a young boy, what would I have had to add to the story of Landbouwbelang and its users. Even when I got older and became a ‘consumer’ of the space, I merely stayed an admirer of the place, the people and its architecture. I admired the life and the course of history that was so present at Landbouwbelang. The industrial past that got a new life without the embellishments that are put in place when these places are redeveloped commercially.

My grandparents and great-grandparents have worked in the industries in Maastricht. Not specifically at Landbouwbelang, but in the ceramics industry that was just around the corner and on the other side of the city. The most prominent of these buildings, the Eiffelbuilding of the Sphinx factory, is now a Student hotel and a cinema. Program that does not connect to history, but that is present only for the most volatile group of people in Maastricht, students.

Now meeting the community of Landbouwbelang, I find people that have lived there for 15 years already and other people that have been involved for only 3 years. Within this community a discussion around volatility

is also present. The people that have build up Landbouwbelang from the beginning, feel a deep connection to the history and soul of the place. They have seen the changes that have formed Landbouwbelang to what it is at this time. But now it is the current time and the pressure of development is ever so real. Within the community a voice has come to the forefront saying that this pressure cannot be denied. The younger inhabitants acknowledge the history of the squat and underline the capacity of adaptation of Landbouwbelang and its community. They aim to point out the potential that lies in the creation of the future. In that sense the community stands at a crossroad where they can choose for a volatile approach that is engrained in the soul of Landbouwbelang and add a new positive chapter to its history. Or they can choose for a fixed mindset that would mean holding on to the history that has already been written. In this interplay of sentiment I think there is no right or wrong. An addition to the story of Landbouwbelang should take both sentiments into account. You can only write a truly worthy new chapter when there are firm roots in the history of Landbouwbelang and the site it sits on, and when the significance of the place through all the time layers is taken to heart.

6564

bunkers

big hall

warehouse silos

existing

6766

intervening

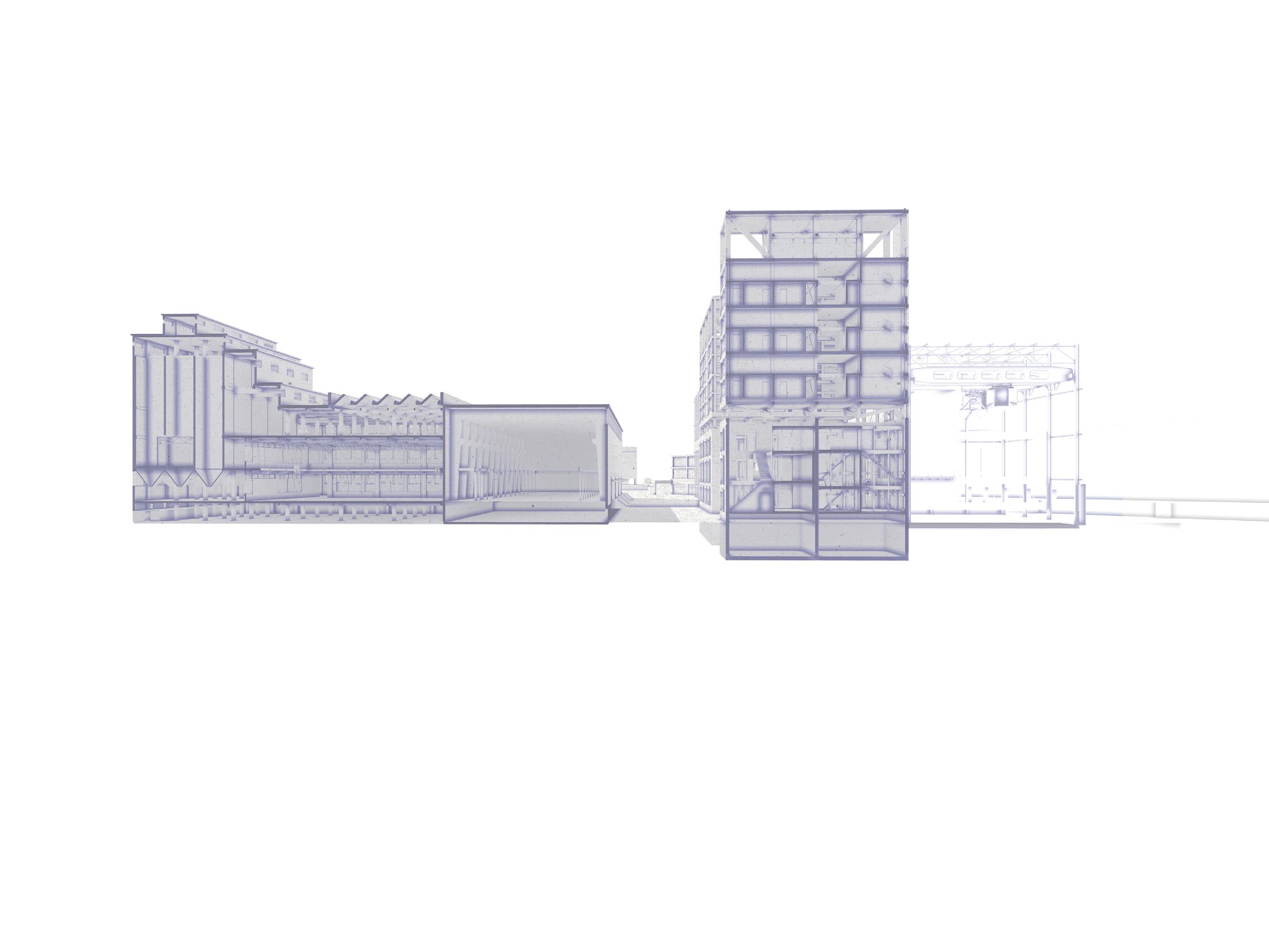

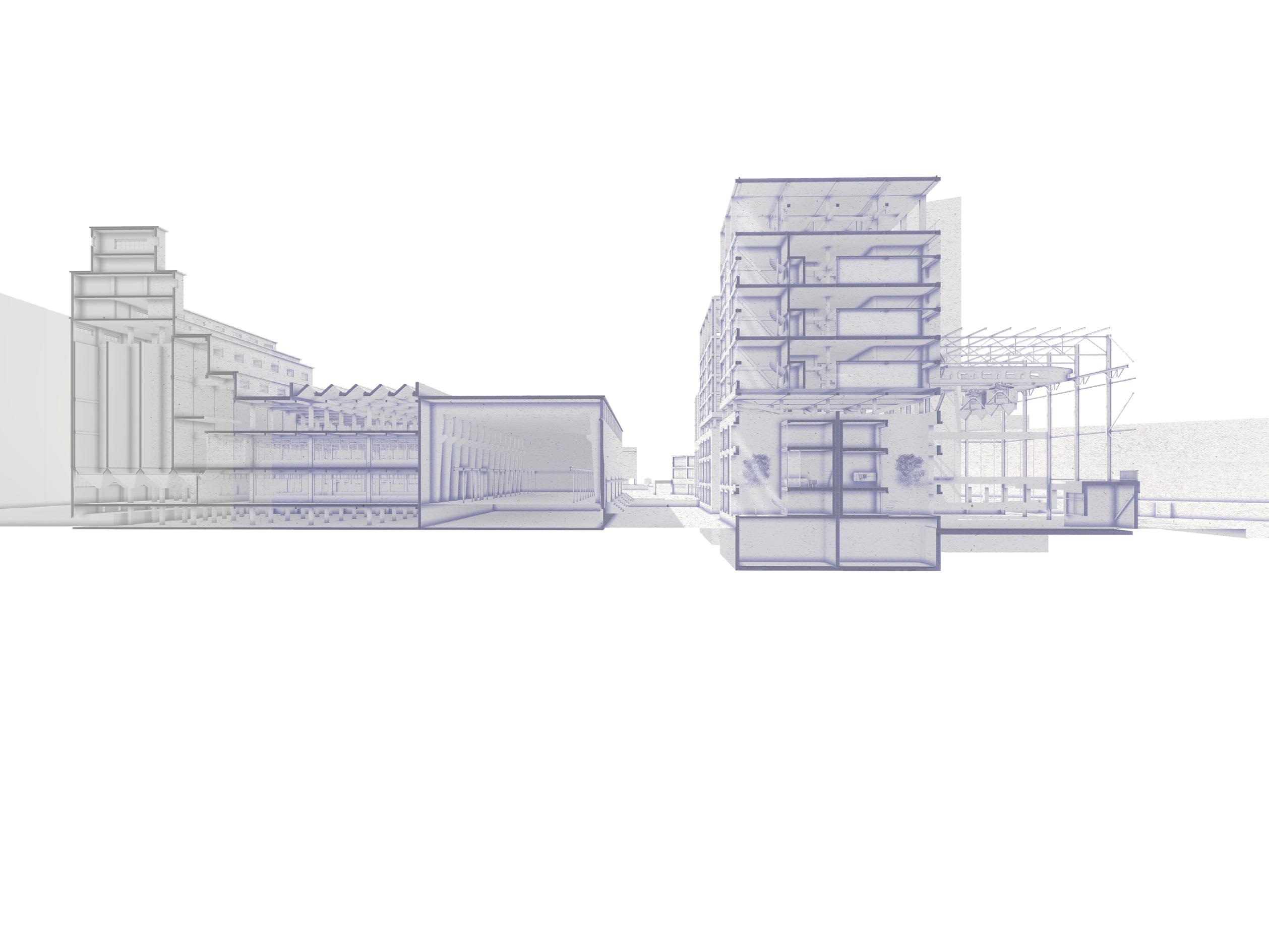

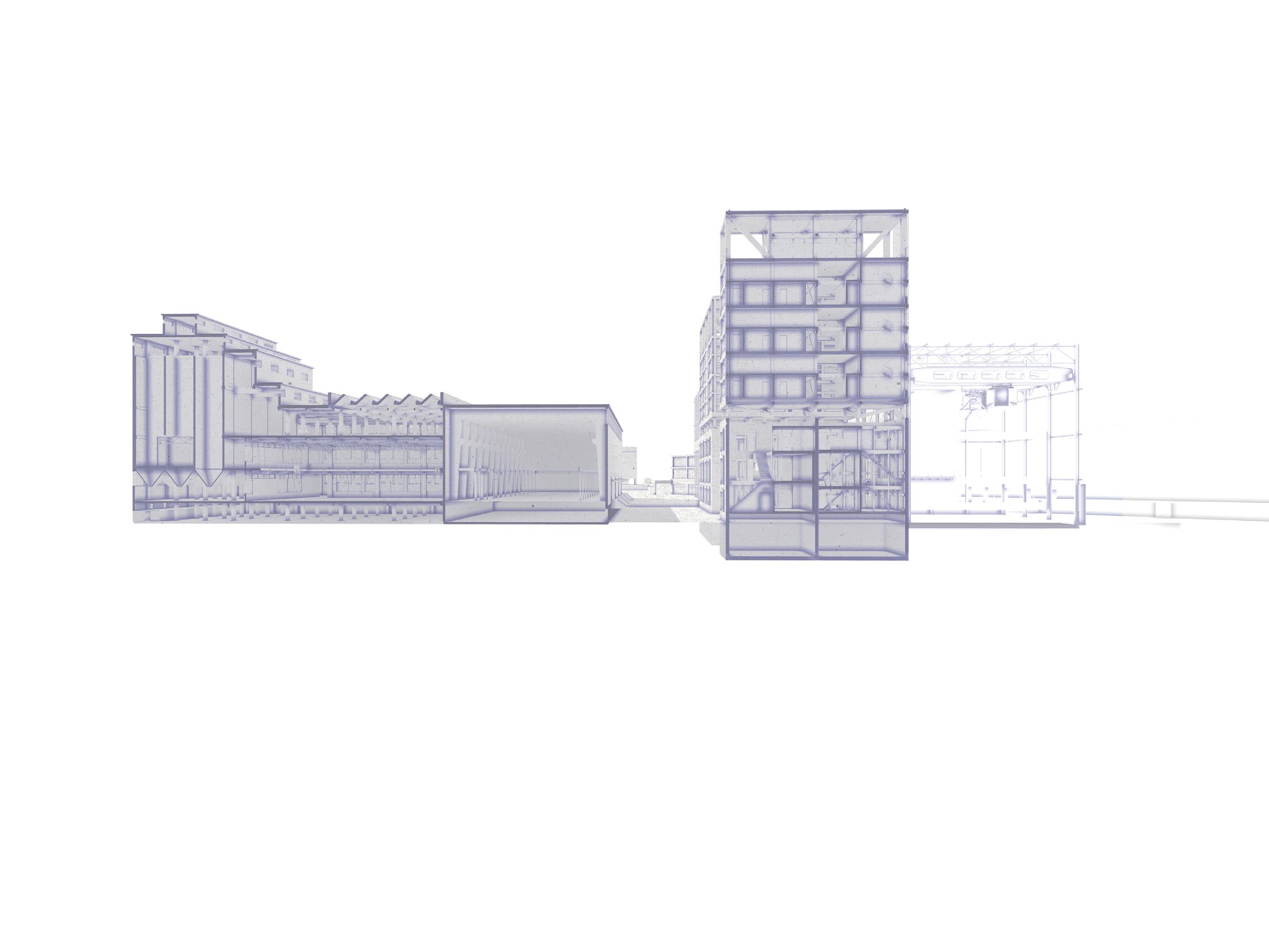

The interventions in the existing Landbouwbelang building will use the concrete structure as the base for a new chapter to the building. The concrete structure can only be downcycled when it is being disassembled or demolished. Keeping the structure for a new layer to building provokes a pragmatic architecture because it requires a sensitive and path dependent approach.

The steel structure which we find on the Northside of the site can be disassembled and recycled more succesfully. For a big part the steel structure is either opened up or completely disassembled. This makes space for the new uses and additions, and create new urban connections.

existing demolished

6968

dissassembled

7170

silos + warehouse

The grain warehouse is kept for a big part in its current form. Except from two big interventions: the concrete casco cut out to make big spaces for a gym and a reading room. The cut-outs are placed in the deep dark centre of the warehouse and in the silos. These are the locations in the building that are the most difficult to inhabit for people because of the lack of light.

The silos will be used as new reading rooms for students out of the whole city. This reading room links to the monastic life of easier days on the site, where the monks devoted a big part of their life to Bible studies.

The gym is a whole new function that is inserted into the Landbouwbelang site. This gym provides a new collective function to the site which attracts new groups of actors to Landbouwbelang. It diversifies the usage and users of Landbouwbelang. The floor above the gym is the upper floor of the warehouse. Here a roof light will be inserted in the roof to let extra light into the deep floor. This can be used as a gallery for all the artists and craftsmen that still house their ateliers on the window sides of the building. This way the use of all the space

7372

warehouse

7574 existing

intervention

intervention

The gym is cut out of the floor leaving the perimeter in tact. The above floor is propped by steel trusses. The gallery (and viewing balcony) is anchored on the above construction and in that way is floating over the gym floor.

7776

appropriation

The ateliers return to the edges of the warehouse were they have light and air. This zone is left to appropriate by the users themselves.

In the silos the spaces can be enlarged by cutting and propping the concrete walls further than the initial voids created in by the intervention.

7978

8180 intervention initial

void in silo

appropriation

The ateliers return to the edges of the warehouse were they have light and air. This zone is left to appropriate by the users themselves.

In the silos the spaces can be enlarged by cutting and propping the concrete walls further than the initial voids created in by the intervention.

8382

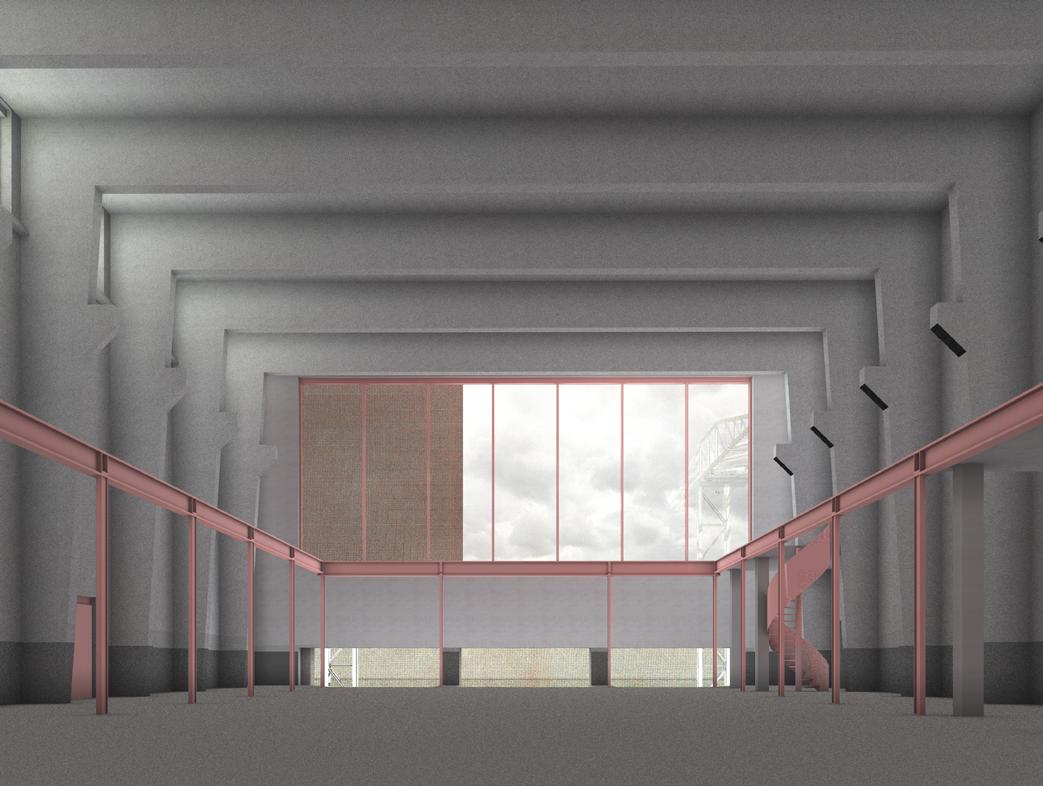

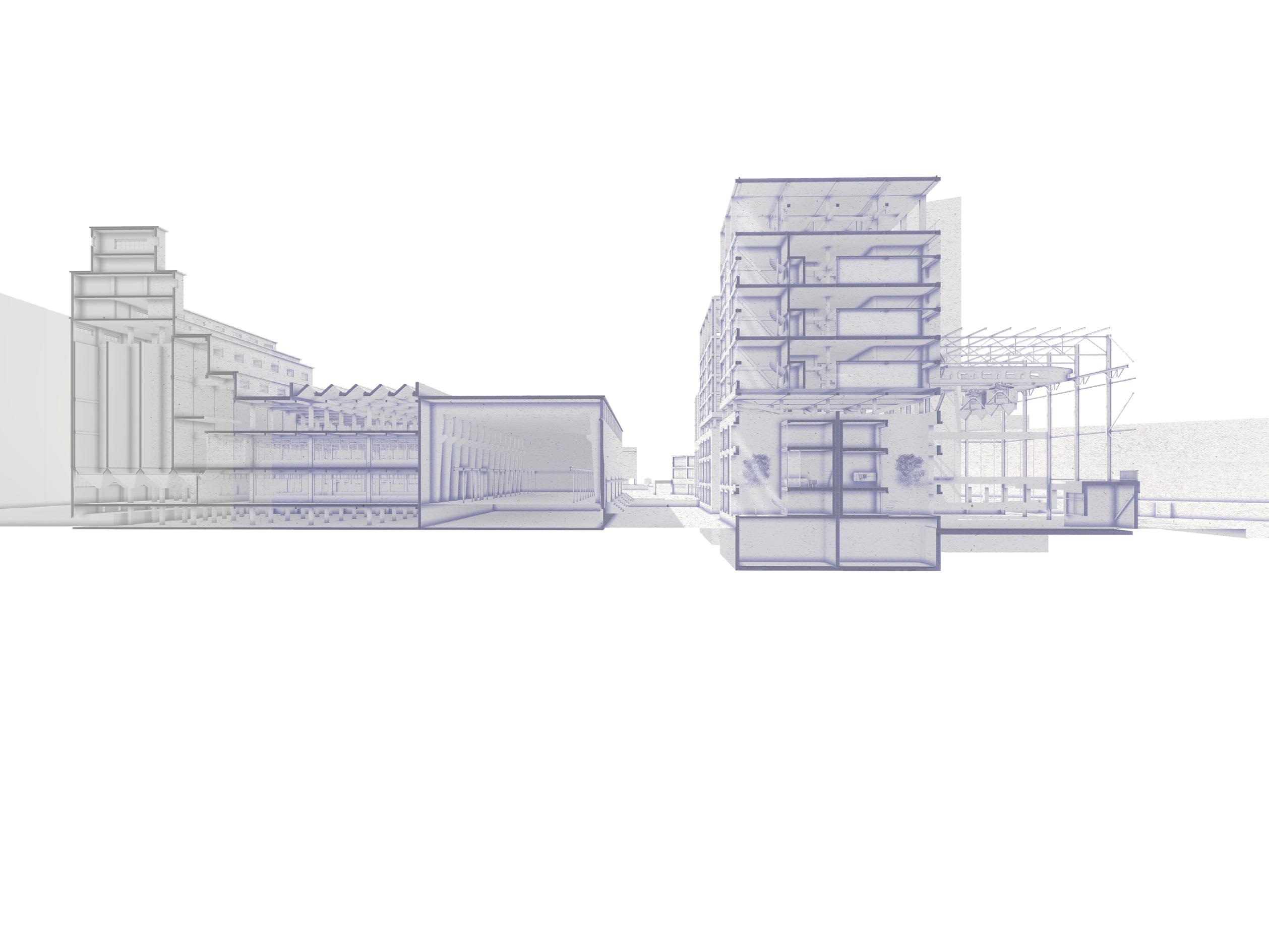

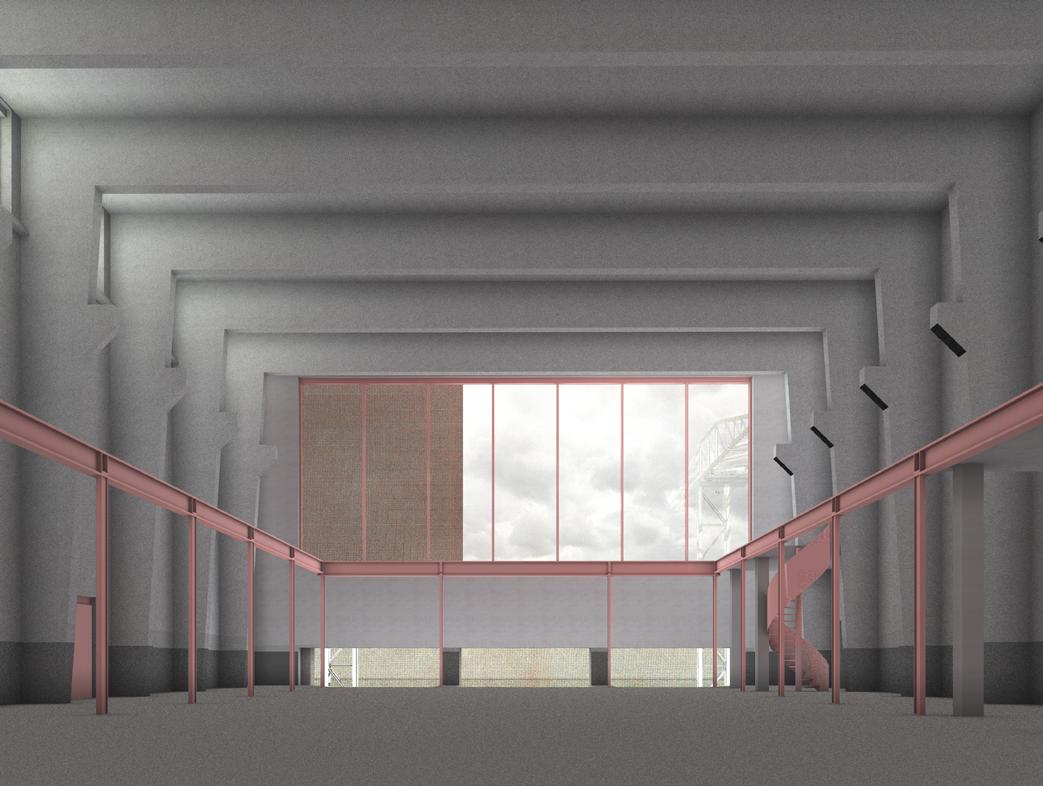

big hall

The big hall’s use as multifunctional events space is preserved for the future. It has proven to be a unique space that is part of the public domain of Maastricht. The only intervention here is to enhance the public character of the hall and strengthen the multiplicity of it. The public character is extended by opening the Northside of the hall, which is possible because the smaller hall next to it is disassembled. This provides space for the historical gates on the side of the big hall to be used as public entrances. On the quay side a big opening towards the Maas is made, with stairs descending from the hall to the quay.

The multiplicity of uses of the big hall is supplemented by adding an extra steel structure to the perimeter of the hall. This creates new possibilities to appropriate the hall to the desired needs. It gives the hall new layers of usage by suggesting a perimeter and an ‘interior’, but also by encouraging a horizontal division of the hall. It gives the hall a possible second level to use or to store elements.

8584

8786 existing intervention

intervention

The opening towards the Maas makes the big hall a true public space in which events of any kind can be enfolded.

The steel perimeter structure suggests an interior and perimeter space.

The structure encourages even more multiplicity of uses for the big hall.

88

appropriation

The appropriation of the steel structure will create a new division within the big hall that is guided by its users. A periphery on the edges is created by the structure, this can be used as ‘backstage’ space. But the structure can also be used to make an extra level in the big hall; an added vertical multifunctional use.

90

bunkers

The concrete bunkers that were used as clay containers for the paper mill adjacent to Landbouwbelang, are stripped from their steel upper structures. This leaves them as freestanding concrete objects on the site. The concrete tubes are given a new use as a facade to live behind. By cutting holes out of the concrete the structure becomes habitable, just as the squatters created new holes in the Landbouwbelang facade to let light in and create connection outwards. The existing inner division in four of the clay bunkers will be assigned to a family cooperative that can collectively build their own house in the bunker. This way family collective live can come into existing in the bunkers. Targeting these bunkers to families that want to live collectively here, brings in a new target group to the Landbouwbelang development. A target group that brings in a specific liveliness to the site; a liveliness with kids of which we do not find a lot in the current situation.

9392

existing intervention

appropriation

Family collectives build their own house behind the newly created facade of the bunker. Each segment in the bunker can house a family collective of around two families.

The patio is suggested to make sure enough light falls into the 9 meter deep bunker segment.

96

suggestion of living in the bunker

9998

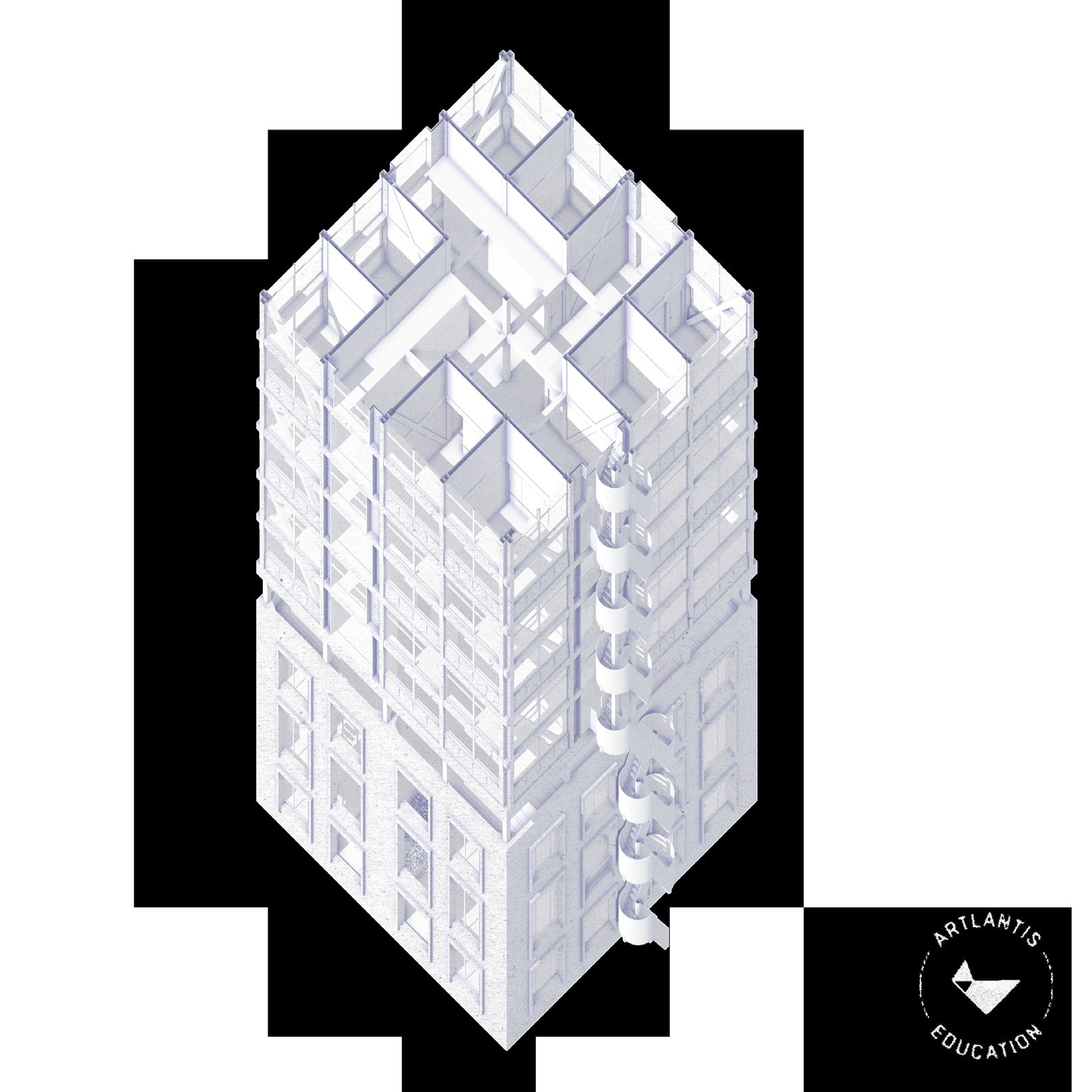

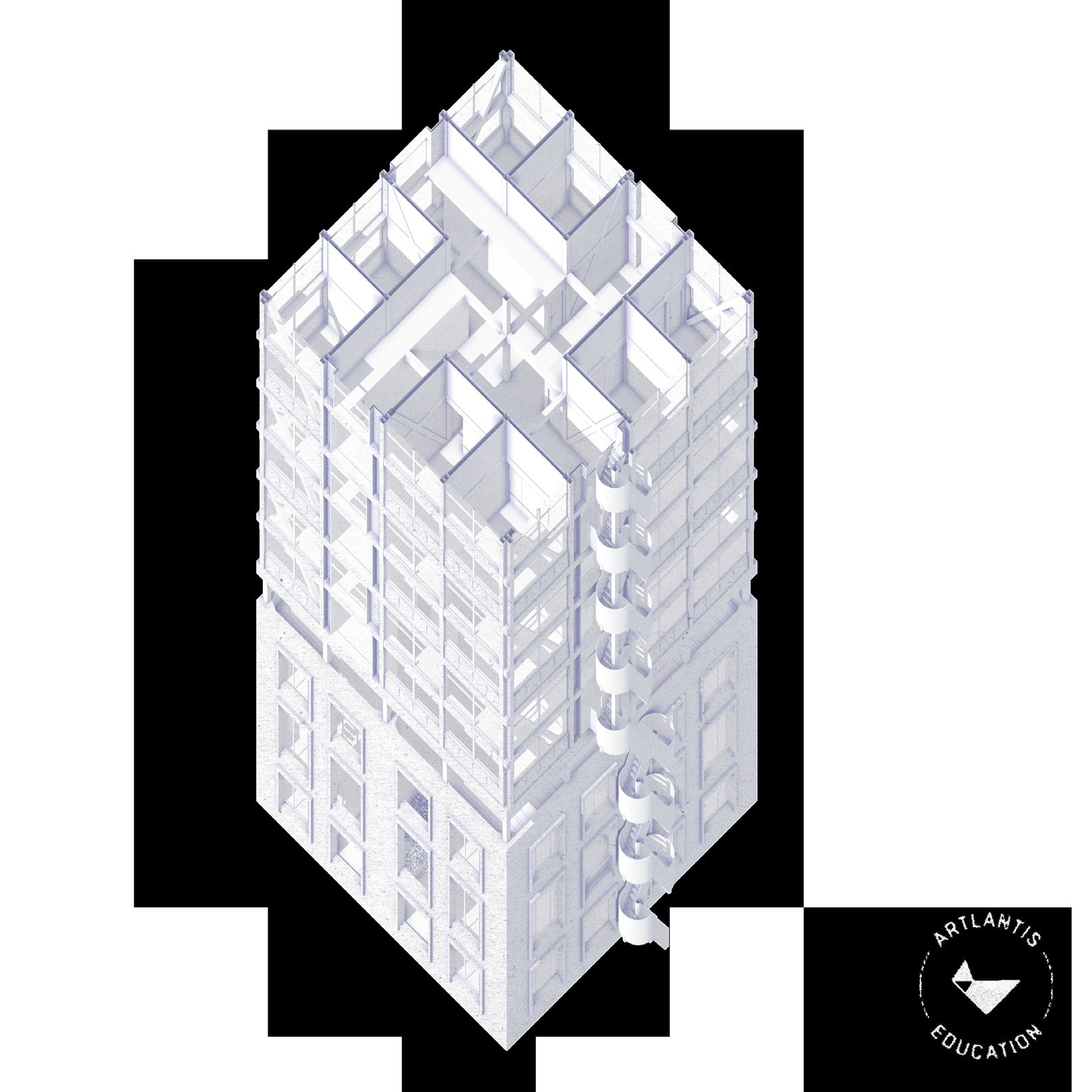

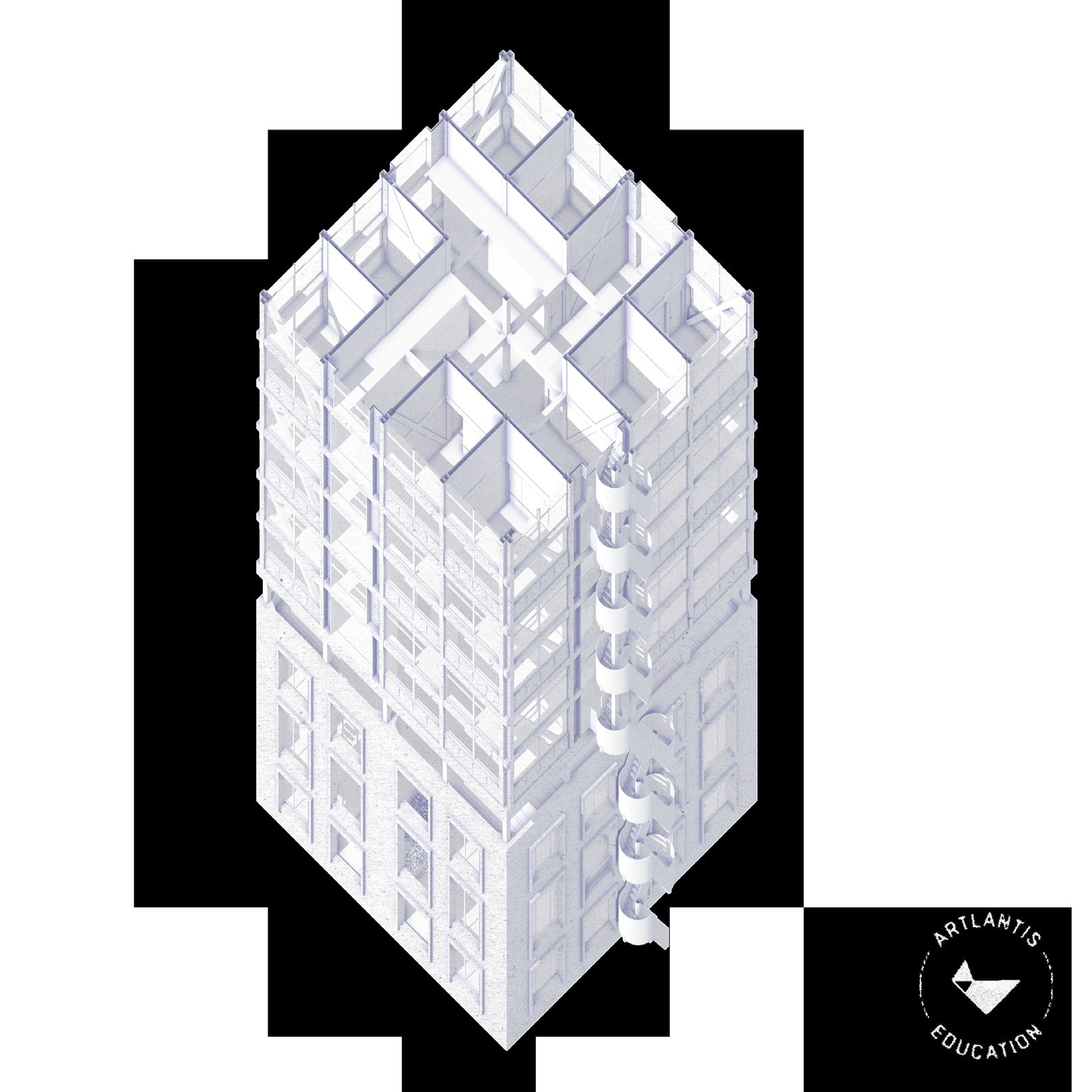

top up

Next to a facade the concrete bunkers are also used as foundation for a wooden top-up on both of the containers. In addition to the family collectives that will build their house in the bunkers, the top-ups will house multiple collectives. These collectives will target people that are looking for a collective lifestyle that is reminiscent of both the monks and the squatters. The top-ups will have one collective living per floor. These floors house a large collective space which has views towards all sides, but the heart is the most collective part. This ample collective space is achieved by placing the circulation core outside of the two top-ups. This gives efficient circulation and creates a valuable interior collective space. From this collective space the individual living units can be reached. The individual units have a minimised floor space of 28m², but have a double height like the rest of the floor.

The double floor height in both the collective space and the individual units know a structure that provokes a certain appropriation of the space. This can be done by adding floors, opening up interior walls or any other way. The column and beam construction can sustain ample alterations.

The upper floor of the top-ups is left unprogrammed. Its structure here provides freedom to appropriate and alter this floor to the desires of the new inhabitants. These are collective floors that can be used in any way the inhabitants find fit. In that perspective they can be used as public floors, or have a more private collective character. It places the ‘deconstructivist’ squatter’s approach on a pedestal visible for the whole city. A reminder to the city that Maastricht is not only a smooth city or ‘sjiek en sjoen’.

101100

intervention

The top-up uses the concrete bunker as a foundation. The top-up is a wooden structure to minimise the loads on the existing concrete bunker. The structural grid follows the segmentation of the bunkers underneath as a true foundation fo the added layer.

102

appropriation

The top floor of the top-ups is a collective floor to be used by the whole building. This floor is unprogrammed to let it fully open to appropriation by the inhabitants. It makes the additions and collective outings very visible to the city. A beacon that showlights the subcultures that claim the scarce freespace in the city.

104

a current inhabitantan architecta design curator a welder (who has a workshop in Landbouwbelang)

appropriation by...

To highlight the multiplicity of views and uses several potential users have been asked to appropriate the rational structure that is added to Landbouwbelang.

From spatial professionals to inahbitants, they have envisioned a certain future and appropriation to show how the top-up can sustain all these additions and adaptations.

a landscape architect

107106

intervention

By placing the circulation core outside of the building the collective core becomes an inhabited structure. The column and beam structure highlights both the double heigth and a second level to be appropriated by the inhabitants.

108

collective core

appropriation

The open column and beam structure in the collective space provokes the inhabitants to build their own world within the structure.

Also the indivdual units can be altered according to the desires of the inhabitants.

The possibility is there to repurpose it to either individual or collective needs.

110

113112

collective living

An open central space that unfolds between the column and beam structure holds the double heigth collective space in the top ups. The individual unit with also the 5 meter ceiling heigth and massive windows, gives the small units an adaptability and grand quality.

115114 +5

117116 +6 private unit

119118

structural

By placing the core outside of the wooden top-ups a hybrid wooden structure with a stiff concrete core cannot be achieved. This requires an alternative approach to attaining a stiff whole in the top-ups.

By making four towers with individual wind bracing the braces can be placed in the walls that divide the indivdual living units. To deal with twisting forces the four towers are connected so they counterbalance the opposite towers and forces. The connecting beams between the towers go through the collective core, but is freed from extra diagonals. This leads to an open and clean central core; a central space as an inhabited structure.

121120

The wind braces follow the walls of the individual living units. The diagonals in the woodstructure remind of the timber-framed houses typical of the region. The corner unit will show the diagonal of the wind brace behind the glass.

123122

124 1000 2000 3000mm

dividing wall

2x12,5 mm hemp plate (hemplith) 100 mm insulation cavity 100 mm insulation 2x12,5 mm hemp plate (hemplith)

CLT wind bracing

floor

25 mmtop floor 10 mm hemp impact sound isolation 240 mm kerto ripa KRB 45x200 acoustic isolation within floating ceiling (fireproof)

1 1 copper plate 2 rhombus pine slats 3 stained plywood panels (18mm) 4 kerto-Q floor 5 sunscreen 3 2 4 5

129128

131130

appropriation

Over time the top-ups will be appropriated by the users of the building. This will have an effect on the appearance of the facade. But the gridded structure and copper panels are strong elements in the facade, that maintain a frim framework for all additions made over time.

133132

new situation

135134

137136

section existing

139138

section proposed

143142

existing Landbouwbelang as a barrier on the edge of the Maas

Sphinx

Bassin

Bureau Europa Lumiere

Sappi

urban situation

Landbouwbelang is part of the urban tissue that encloses ‘t Bassin. At the same time it closes off the connection towards the Maas river. The dissassembly of the nonmonumental hall in between a new route and view is installed through the site. A route that connects to the public big hall. A second route along the water makes it possible to experience the Maas and the views over the water all around the site.

new routes make the Maas approachable

Nolli - the big hall connects a public domain to the new route

145144

inside world symbolism structure claustrum enclosures courtyards boardwalks

Monasteries order

Squatters chaos

porosity pragmatism flexibility informality openness interaction directions

147146

hortus rarus

The new future for Landbouwbelang fuses two histories of the site: the monastic history and the squatters history. They find eachother in its collective, public and private qualities. But they also seam miles apart in their values and routines. A monastic world in which order is perceived as the supreme objective. Whereas the squatters approach values informality as the highest.

Landbouwbelang will remain an island in the city where these two worlds play out together. As in the monastic gardens an order in the public space will be installed by identifying spaces as they are defined by the buildings. This order can withstand a more informal infill of elements in the public space.

Eventually the whole site will we be embraced by a monastery wall. This highlights the individuality of the ‘island’ in the city. The wall is not a hard border though, it is a permeable border to demarcate a world of ‘otherness’ as opposed to the smooth city. With this a porosity is created that makes the garden part of the public space of Maastricht. It gives Maastricht a new type of public domain: the hortus rarus. A porous garden.

order that can withstand ‘chaos’

149148

embraced by a porous wall

153152

ateliers/workshops

foodbank/restaurant

public space (events)

family collectives

bath house

freespace (workshops)

freespace

watercloister

155154 1- gym 2-

3-

4-

5-

6-

7- brewery 8-

9-

10-

7 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 10 5 10 20m

157156

159158

reflection

With a large pressure on cities and governments to fulfil housing needs, it is valuable to keep in mind the premisses of brutalism as Alison and Peter Smithson stated them. For them it was never a stylistic discussion; at the heart of brutalism was an ethical debate. It poses new objectives for what architecture can and should do, which takes a step further then the sole production of houses. Brutalism in this case was a reaction following up on the compact, disciplined postwar architecture profession. Brutalism made a move towards examining the whole problem of human associations and the relationship that buildings and community has to them.

The current mass-production of housing brings us to the same discussion. We need to handle our cities and our history with an ethical mind, as to not erase several pages of our collective past. We need to understand the relationships that communities adhere to the built form. Exactly by this approach we create the conditions to drag a rough poetry out of the cities we have inherited from our ancestors.

As an architect I have tried to get a firm insight in the reality of Landbouwbelang and have meticulously read the site. With this knowledge I have used the exisiting structure as a basis and added a layer to the history of Maastricht. The built form has for the biggest part been kept intact. On the programmatic side the new Landbouwbelang can be viewed as a palimpsest, where the current and historic programme is reused in a different setup, but still bearing the visible traces of its earlier form. This way of superimposing a new order has the potential to bring a lot of new value to the city and its inhabitants, especially when it is adapted by its new users.

“Brutalism tries to face up to a mass-production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.

Up to now Brutalism has been discussed stylistically, whereas its essence is ethical”

Smithson, Alison and Peter(1957) “The New Brutalism”, Architectural Design (April 1957) p.113

161160

Alison and Peter Smithson

With special thanks to

Harold van Ingen and the Landbouwbelang community

Milad Pallesh, Machiel Spaan and Christopher de Vries

Ronald Wenting (structural engineer)

UNIT4 collective Jesse Stortelder Carola Raaijmakers

Lennard van Buren

163162

© 2022, Art Kallen

Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd of openbaar gemaakt zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van Art Kallen.

165164