O’BRATE STADIUM

JOEY GRAHAM

THE FOOTBALL FIVE PAIN & GAIN

ATHLETES & DADS

PISTOL PETE

JOEY GRAHAM

THE FOOTBALL FIVE PAIN & GAIN

ATHLETES & DADS

PISTOL PETE

At Oklahoma State, that guy is senior associate athletic director Marty Sargent. Sarge, as he is known around the athletic department (we aren’t terribly creative), spends time thinking about worst possible scenarios involving fan safety, student-athlete safety and team travel. If he could, he would devote time trying to solve world famine, global warming and maybe he would squeeze in some hand-wringing hours contemplating how the sun is due to burn itself out in about a kazillion years.

Marty Sargent played linebacker at Iowa State for Johnny Majors and Earle Bruce. He began his career coaching football at his alma mater (where he was on a staff that included former Oklahoma athletic director Donnie Duncan, current Seattle Seahawks head coach Pete Carroll and former Texas head coach Mack Brown). He arrived at OSU in the 1980s in an administrative role, and has worn many hats at OSU.

These days he oversees game day operations. His Wednesday afternoon meetings during game weeks are legendary (take our word for it, but don’t actually attend one). And no one knows the OSU travel policy better than Marty Sargent. If an OSU team is flying out of Stillwater, Sargent is there to see them off at the airport. When the OSU team charter arrives to pick up the Cowboy football team for its bowl trip, it hits the Stillwater skies with a single passenger on board. That person is of course Marty Sargent, who met the charter in Houston to assure smooth flying.

Sargent is deeply involved with bowl planning, which might be the least stressful part of his job – even if it does become an 80-hour week. He works hand in hand with law enforcement on game days where his concerns run the extremes from where to park the visiting band to possible terror threats. And don’t ever ask him about potential weather problems. He has more apps on his phone than Meryl Streep has accents.

Sargent is OSU’s one-man secret service agency. He does everything but talk into his wrist.

What does he do during the spring? Well he sees virtually every inning at Allie P. Reynolds Stadium. Some people think it’s because he’s a fan. And while I’m sure he likes Josh Holliday well enough, most of us are absolutely convinced he hangs out at Allie P. because college baseball is the sport of choice for local meteorologists. Rain, snow, lightning, high winds, constantly changing in-game conditions … That sport has it all.

The truth, though, is Marty Sargent has to think about things that make the rest of us uncomfortable. A weather delay at a football game is nowhere close to the worst possible scenario, which paints a tiny picture of the responsibilities Sarge carries around each day. Among the senior administrative staff now in place in OSU Athletics, only athletic director Mike Holder, senior associate AD for development Larry Reece and Marty Sargent were around for both air tragedies that OSU has endured this century. He has lived worse-case scenarios. Maybe because of that, he is always thinking – for all of us.

We’re lucky.

Every athletic department needs a worrier. It needs someone who thinks about the things no one thinks about. Someone who thinks about the things no one even wants to think about.

The OSU Athletic Department mourns the passing of Jim Cobb, who was a founding member of the OSU “Posse Club” in 1964.

Along with his late wife, LaVerna, Jim was a loyal supporter of Oklahoma State University in all areas. As Cowboy VIP level donors to the POSSE, the couple endowed a quarter-scholarship for athletics. Jim was also a member of the College of Engineering, Architecture and Technology Hall of Fame, as well as an OSU Alumni Hall of Fame inductee.

He and LaVerna will be greatly missed. Good ride, Cowboy!

POSSE Magazine Staff

VICE PRESIDENT OF ENROLLMENT AND BRAND MANAGEMENT KYLE WRAY

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF / SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR KEVIN KLINTWORTH

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR / EXTERNAL AFFAIRS JESSE MARTIN

ART DIRECTOR / DESIGNER DAVE MALEC

PHOTOGRAPHER / PRODUCTION ASSISTANT BRUCE WATERFIELD

ASSISTANT EDITOR CLAY BILLMAN

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS GARY LAWSON, PHIL SHOCKLEY MELISSA MORALES

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS CLAY BILLMAN, GABE CAMPIS, TOM DIRATO, JOHN HELSLEY KEVIN KLINTWORTH, JOHN LANGHAM ROGER MOORE, BILL SMITH, KYLE WRAY

Athletics Annual Giving (POSSE) Development Staff

ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR / ANNUAL GIVING ELLEN AYRES

PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR CLAY BILLMAN

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, ANNUAL GIVING RYAN SEVERSON

COORDINATOR, ANNUAL GIVING STEPHANIE DAVIS

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, ANNUAL GIVING / EVENT COORDINATOR ALEXA ABLE

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR / DEVELOPMENT LARRY REECE

ASSISTANT ATHLETIC DIRECTOR, DEVELOPMENT MATT GRANTHAM

ASSISTANT ATHLETIC DIRECTOR, DEVELOPMENT SHAWN TAYLOR

OSU POSSE

102 ATHLETICS CENTER STILLWATER, OK 74078-5070 405.744.7301 P 405.744.9084 F OKSTATEPOSSE.COM @OSUFANEX

POSSE@OKSTATE.EDU

ADVERTISING 405.744.7301 EDITORIAL 405.744.1706

A t Oklahoma State University, compliance with NCAA, Big 12 and institutional rules is of the utmost importance. As a supporter of OSU, please remember that maintaining the integrity of the University and the Athletic Department is your first responsibility. As a donor, and therefore booster of OSU, NCAA rules apply to you. If you have any questions, feel free to call the OSU Office of Athletic Compliance at 405-744-7862 . Additional information can also be found by clicking on the Compliance tab of the Athletic Department web-site at www.okstate.com

R emember to always “Ask Before You Act.”

Respectfully,

BEN DYSON ASSISTANT ATHLETIC DIRECTOR FOR COMPLIANCEDonations received may be transferred to Cowboy Athletics, Inc. in accordance with the Joint Resolution among Oklahoma State University, the Oklahoma State University Foundation, and Cowboy Athletics, Inc.

POSSE magazine is published four times a year by Oklahoma State University Athletic Department and the POSSE, and is mailed to current members of the POSSE. Magazine subscriptions available by membership in the POSSE only. Membership is $150 annually. Postage paid at Stillwater, OK, and additional mailing offices. Oklahoma State University, in compliance with Title VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive Order 11246 as amended, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Higher Education Act), the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and other federal and state laws and regulations, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, disability, or status as a veteran, in any of its policies, practices or procedures. This provision includes, but is not limited to admissions, employment, financial aid, and educational services. The following have been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 408 Whitehurst, OSU, Stillwater, OK 74078-1035; Phone 405-744-9154; email: eeo@okstate.edu. This publication, issued by Oklahoma State University as authorized by the Senior Associate Athletic Director, POSSE, was printed by Royle Printing Company at a cost of $1.136 per issue. 9.5M/January

Think

In the modern era, it is easy to take photos (pics as we call them now) for granted. We can take more photos in a day on our phone than previous generations might have taken in a decade. They are distributed all over social media. They are non-stop.

But the heart of photography is still about preservation. It’s about history. It’s about documentation. The photographers at OSU Athletics have no days off. They are at every OSU sporting event with rare exception. They are busy on non-event days as well, shooting for media guides, websites, social media and construction projects. They shoot current OSU athletes, past OSU athletes, even future OSU athletes. They are key to OSU’s digital media and marketing efforts. And they document.

EVERYTHING.

for just a moment about the immense duties of a photographer. Capturing the emotion of a moment that will live forever, providing the only perspective that most of the world will ever see of an event.

MELISSA MORALES BRUCE WATERFIELD

MELISSA MORALES BRUCE WATERFIELD

10/28/18

Former Oklahoma State softball standout Vanessa Shippy was a finalist for the prestigious NCAA Woman of the Year award, which honors academic achievement, athletic excellence, community service and leadership. The three-time NFCA AllAmerican and two-time Big 12 Softball Player of the Year was joined by head coach Kenny Gajewski at the October awards ceremony in Indianapolis.

A Nike Fly Rush Jacket S-4XL | $120 B Nike Loyal & True Striped Beanie $30

C Youth Wrestling Pete Tee XS-XL | $14.95 D Nike Women’s Long Sleeve Funnel Top XS-XXL | $70

E Nike Women’s BBall Cotton Tee S-XXL | $30 F Nike Badge Wrestling Cap $23

G Nike Badge Wrestling Tee S-XXL | $28 H OK ST Wrestling Sweat S-3XL | $36.95 F

I Nike 2018 Replica Jersey #1 S-XXL | $75 J Nike Tri Blend Long Sleeve Tee S-3XL | $40

K Nike Breath Elite Long Sleeve Top S-XXL | $65 L Nike Badge Basketball Cap $23

M Nike Women’s Dry P0 Hoodie S-XXL | $90 N Nike Replica Basketball $30

O Nike Women’s Tri Boycut Elevated V XS-XXL | $40 P Nike Women’s Pom Beanie $30

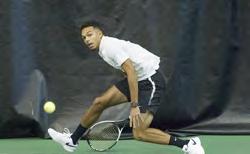

That has been clear for Joey Graham since his legendary Oklahoma State basketball career ended in 2005. And after a rewarding stint playing professional hoops, he is back in town.

Stillwater will always have a special spot in Graham’s heart. It was in the vibrant, homey college town where he met and fell in love with his wife, Trisha Skibbe, who was a standout player for the Cowgirl basketball team when they met in 2003. Stillwater is also where Graham became etched into the lore of OSU athletics, playing a central role in two of the most successful teams in Cowboy basketball history.

A relatable guy with steadfast confidence and the game to back it up, Graham is a heralded figure at OSU. But in his first season as the assistant coach for the Stillwater High School boys’ basketball team, his popularity looks set to expand deeper into the Stillwater community.

Graham has a passion for mentoring and instilling in young athletes the right values and work ethic it takes to be leaders in life. He credits God for blessing him with a multitude of experiences to share, as well as a desire to teach young players the ins and outs of basketball.

He also praises Eddie Sutton, another Cowboy legend who coached him for two seasons (plus a redshirt year), for instilling in him a deeper passion for life and for the sport he loves.

“Coach Sutton was a Hall of Fame coach as we all know, even though he didn’t get the just due credit for it,” Graham said. “He taught me a great work ethic and resilience because Eddie was a no-nonsense kind of coach. If you messed up you would get one more opportunity to correct it, and if not, you’re done.”

These lessons on integrity showed Graham that he had to be persistent with the gifts and talents he had or he risked losing focus and missing out on special opportunities.

The journey to playing under Sutton wasn’t the most conventional for Graham but ended up being beneficial. His dad, Joseph, was a Navy pilot, so along with his twin brother Stephen, older brother Brian, and mother Rose, he moved several times during his childhood.

They eventually settled in Florida, where Graham was introduced to the game. He first played competitive basketball in eighth grade and continued to play as a freshman at Land O’ Lakes High School, having competed in football, soccer and track before moving to the hardwood. When he first started playing, Graham hadn’t finished growing.

After spending his freshman season at Land O’ Lakes, he then transferred to Brandon High School, where he had a growth spurt that wound up being critical for his development.

“I was short,” Graham said. “My eighth grade year I was like 5’3” or 5’4” … I probably got to 5’6” my freshman year in high school.”

Graham said he kept growing, and between his junior and senior years he grew six inches to get to 6’6” and finally two more to finish out at 6-foot-8. It helped him become a force at the prep level, and he received offers from several high-profile Division 1 schools.

As he debated where to commit during the recruiting process, there were a few factors to consider. One happened to be his mom’s wish to have both he and Stephen play at the same school, and though they both didn’t feel strongly about playing together in college, they wanted to support their mom’s wishes.

“Even though we were twins, we never really acted like twins. We said, ‘But if one of us comes, we both come,’” Graham said.

They wound up picking the University of Central Florida, but after playing at the midmajor level for two seasons, he and Stephen were ready for a new and exciting challenge. At the time, and still to this day, the Big 12 was in the upper echelon for basketball competition, with OSU consistently competing for the conference crown. That success is what appealed to Graham: the opportunity to have his talents tested against other NBA caliber opponents.

“ Ted Owens , at the time when I was growing up, was the athletic director at St. Leo University. We used to sneak into the gym when the lights were out, and he would come in there and watch us shoot.”

Owens, the head coach at Kansas for 19 seasons, mentored Graham and showed him some of the fundamentals of the sport. As they went separate ways, they stayed in touch, and when Graham decided to transfer from UCF he reached out to Owens for help.

“He was from Tulsa so he knew Eddie, he knew Coach (Roy) Williams , who was at Kansas at the time,” Graham said. “So we called him up and we said, ‘Hey, Coach, we’re looking to transfer, do you know any teams in the nation that we can go to?’”

Owens’ first call was to Sutton, and after a workout and a conversation with Sutton, the Graham brothers had a new home.

Prohibited from playing right away due to the NCAA’s transfer policy, Graham couldn’t compete during the 2002-03 season but had the chance to practice and prepare for the intensity and the expectations that come with being a Cowboy. There was definitely a learning curve that came with playing under the College Basketball Hall of Fame coach, with every practice a test of mental fortitude. Each time he took the court exposed him to lessons in determination that could only come under Sutton.

“You can’t go into an organization or a university playing mediocre ball,” Graham said. “He’s not going to bring in mediocre players. So I had to learn to be tough, I had to learn to be resilient, and I had to learn to be persistent about this game that I love. Those were a few of the things Eddie taught me.

“He’s not going to bring in mediocre players. So I had to learn to be tough, I had to learn to be resilient and I had to learn to be persistent about this game that I love. Those were a few of the things Eddie taught me.”

“If you were an A-minus player he brought you up to an A-plus-plus player just on work ethic and playing hard.”

Once that season of sitting out was finished, Graham said he was eager to suit up as a Cowboy. Alongside several other standout players, the 2003-04 campaign saw OSU win the Big 12 regular-season and tournament championships with a staggering 31-4 record and ended with the team’s most recent trip to the Final Four.

There were too many incredible memories of that season for Graham to only choose one, but he said the talent within that squad and the attitude that they were going to outwork everyone helped them go far.

The two seasons Graham was eligible to play at OSU helped boost his stock and propelled him into the first round of the 2005 NBA draft as the 16th pick, selected by the Toronto Raptors. His versatility as an athletic wing player who played the role of a shutdown defender made him a valuable commodity for nine seasons in the pros. Graham said spending so much time playing the game that he loves and building lasting friendships with teammates was incredible.

“Those guys that you’re on the team with, you see them every day for a full season,” Graham said. “A lot of them you build a tight relationship with. All the guys in the league, you have a brotherhood with most of them.”

Playing in the NBA is a rare opportunity, and Graham said having that in common with only a select number of people leads to a feeling of camaraderie.

“There’s only 400-500 players, so when you see them in the airport or in a different city you always kind of say hello to each other because you have that one thing in common,” he said. “You’re playing in a prestigious kind of fraternity.”

As those nine seasons came and went, Graham’s focus shifted to settling down and starting a family. Since their time at OSU, Graham and Skibbe had dated off and on during the subsequent 15 or so years, but never had time to truly settle down as both had playing careers that took them across the world. They would visit each other in the summers, though, when Skibbe would come back from playing in Greece. They eventually got married in 2016 after both had retired from the sport.

“You’re playing in a prestigious kind of fraternity.”

Trisha said her relationship with Graham worked well because they could relate to each other in balancing basketball, school and life.

“We understood what each other was going through because we were always at practice or going to study hall or in the weight room or on buses or planes,” she said.

The couple have three children now: Kingston, 6; Taylyn, 5; Trinity, 2; and Graham said they’re his world. That’s why it was important to him and his wife to find a great place to raise them with quality education and great people.

“Stillwater is a really good place to raise a family,” Trisha said. “Neither of us wanted to raise our kids in a big city. We wanted the midwest feel, the home town, smaller community. I think that’s what happens when you have kids. You really base your decisions around what’s better for them.”

Although he was blessed with the chance to play basketball for a living, Graham soon recognized there were opportunities for him to give back a little.

For many of the kids Graham coaches, there is an air of respect in listening to a guy who played nine years of pro ball, against the likes of LeBron James , Dwyane Wade and Kobe Bryant , but they don’t necessarily grasp the significance of him returning to town.

High school players were too young to remember when he threw down a jam against Memphis in the 2004 NCAA tournament, the same season he won Big 12 Newcomer of the Year. Thankfully there’s YouTube for everyone to look back on moments like his baseline drive and posterizing finish over Hall of Fame center Alonzo Mourning , but it still doesn't have the same impact of witnessing those moments first hand.

Nevertheless, Graham has made an impact on some of the players at Stillwater High School.

“He’s helped me a lot in my post work and being more physical,” said one Pioneer. “He knows what he’s doing. He’s been there, he’s done everything. He wants to talk more, and he wants to communicate more. If you don’t know what you’re doing, he wants to talk and figure things out.”

Graham isn’t a stranger to coaching. During his time in the NBA, he and Stephen set up their own training program in Florida – Graham’s Shooting Stars – in which they would host camps during the offseason. The Grahams would teach some of the skills and drills they had developed or learned to kids in small groups or in private training sessions.

“All the knowledge, all the skills, all the training that we did and worked on to get to the position that I was in being a successful basketball player, I pass it on to them,” Graham said. “Hopefully they absorb something that you say or do or see and go out and become the best human beings and basketball players they can be.”

Trisha said she believes her husband will be a fantastic coach because he has the patience to deal with the adolescents but is firm enough to keep them in line. She knows he is a competitor that won’t take it easy on the players until they reach their goals.

“I think he will have the patience to deal with the parents, which you have to deal with more at a high school level than you do at the college level,” she said.

Graham is now in the midst of his first season at Stillwater, and as it continues to unfold, spectators can start to see some of the things he has implemented truly take shape. It will be a learning process, but Graham is well-equipped with lessons from his past to make things happen.

“All the knowledge, all the skills, all the training that we did and worked on to get to the position that I was in being a successful basketball player, I pass it on to them.”

Plus, with his family firmly settled in a city of loving and welcoming people and where he made some of the best memories of his life, coaching and mentoring is his sole focus.

He’s back home.

Annual Membership for Kids 8TH Grade and Under

ONLY $25 PER CHILD

Sign up today at okstate.com/kidsclub

OFFICIAL KIDS CLUB OF OSU ATHLETICS

,

Pistol Pete s Partners offers young Cowboy and Cowgirl fans the opportunity to attend over 100 OSU Athletics events for FREE! Plus ...

• Invites to “Member Only” Parties with Student-Athletes

• Membership T-shirt

• Picture of Pistol Pete

• Birthday Card from Pistol Pete

• AND MUCH MORE

FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT OKSTATE.COM/KIDSCLUB

Mike Holder generally dismissed previous tips from Chris Bahl about some off-the-grid “farmer” who had deep pockets and Oklahoma State ties residing relatively incognito up in Kansas.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Holder said. “(Chris) was standing in the doorway of my office and made an off-hand comment about someone in Garden City from OSU.

“I remember wondering what the odds were that Oklahoma State wouldn’t know about someone that close to Stillwater doing so well.”

He decided to find out.

Cecil O’Brate was indeed a man to know, a self-made success story with a history of winning big at business. And yes, he had a history with Oklahoma State in his past — deep in his past, yet still providing warm thoughts and memories.

“I got on the Internet and sure enough he owned a company, American Warrior, and in the bio there was information on his background,” Holder said. “And at the very bottom it said: attended Oklahoma State University.

“I said, ‘Well, I’ll be doggone.’”

And that’s the beginning of the return of Cecil O’Brate to Oklahoma State University, as friend and family, as an honorary alum, and as a major donor providing overdue momentum for the rise of OSU’s new baseball stadium ...

O’Brate Stadium.

Cecil O’Brate was born in Enid, Okla., in November of 1928. Just in time for the Great Depression.

O’Brate grew up in parallel with the worldwide economic crisis that hit the United States with a devastating blow. He grew up in poverty, although none of it dimmed an internal passion burning inside him to change both his fortune and his future.

By the age of 10, nearing the end of the depression, he was working jobs. By 16, he’d already built a résumé of sorts, delivering newspapers, stocking groceries, working as a butcher, bread slicer, salesman, gas station attendant, used-car salesman, glasses maker and more.

Early on, O’Brate showed entrepreneurial skills, too, as he creatively found additional avenues for earning money to help provide for his family.

“Every dime helped. We counted dimes then, not dollars,” he said in the book Making It Happen: Be Smart, Work Hard , and Never Worry About Having ‘Enough’ – Lessons from Cecil O’Brate.

Life changed abruptly for O’Brate as he moved into his late teens. Prior to his senior year in high school, he moved with his grandparents to a custom farm in Syracuse — not New York, but Kansas.

“It’s 50 miles from Colorado and 50 miles from Oklahoma,” he said. “You can’t quite see the end of the world from there, but just about.”

It was there that O’Brate discovered a love for farming, and the love of his life: the former Frances Cole. And the latter was a love to last, as the couple celebrated their 71st wedding anniversary in September.

O’Brate spent that year farming and working to save money for college. And for O’Brate, college meant only one destination: Oklahoma State, or Oklahoma A&M at the time.

He started in the fall of 1946, choosing a major strategically, utilizing the library to research the highest-paying jobs, leading him to architectural engineering, although that would eventually change to structural engineering. O’Brate lived in Cordell Hall and worked two jobs to help pay the bills: packaging ice cream at a local plant and setting pins at the bowling alley.

The ice cream job came with perks.

“I was catching it and putting it in the containers,” O’Brate said. “It comes out about like a malt. They said, ‘Feel free to test some ice cream.’

“I did.”

Once, O’Brate said with a laugh, he overdid things with the ice cream.

“I couldn’t quite afford to eat when I was in Stillwater, and I took a little too much,” he said. “My next job at the bowling alley, I worked in the back where it was hotter than hell. I got so sick I couldn’t even get home. My two roommates had to come get me. So I learned those two don’t mix.”

It’s rare, however, that work and O’Brate don’t mix.

After two years at OSU, in the fall of 1948, serious work came calling. His grandfather leased an additional 3,000 acres of land in Kansas and needed help. O’Brate answered the call, setting aside school and heading off to farm with the family.

The move changed everything, with a successful run of the land thrusting O’Brate forward into business — for good.

“That gave me a pretty good boost,” he said.

O’Brate never returned to school, although OSU awarded him with an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters last May. Instead, he thrived as a farmer, rancher, banker, business manager, developer and serial entrepreneur. He bought and sold property and banks and ventured into manufacturing and the oil and gas business, thriving as always.

Today, O’Brate is President/CEO of several independent oil and gas companies, including American Warrior, Inc., and Palmer Oil. And he’s greatly contributed to reviving Garden City, investing more than $55 million into the community to spark growth and to entice others to invest as well, fueling a rise of new shopping centers, restaurants and business development.

“He’s a living, breathing, testimony that the American Dream is still alive,” Holder said. “You can have nothing but ambition coupled with work ethic and commitment, and you can do anything.

“That’s not unique to the United States of America, but I think it’s more credible here. And I definitely think it’s more prevalent in this part of the United States, here in middle America where there’s good, old Christian values, hard work, loyalty, all the things I think make the country great.

“Cecil is a great example to all the young people who will come through the door (of the stadium) for decades to come. It doesn’t matter who you are, what your lineage is, what your circumstances are today, you can climb the highest mountain.”

Plug a Google search for Cecil O’Brate and the returns are minimal. Startlingly so.

No Wikipedia page. No rundown of his massive accomplishments and portfolio. No scandals. Few stories, although his generous gift to OSU at least adds something current to otherwise outdated material. Not much of anything, with the exception being a spot in Ingram's: 50 Kansans You Should Know And even that offers nothing more than a bare bones bio.

One of the great mysteries of this technological time must be how a man who has made so much and given so much, with such a great story, can fly so far under the radar.

“That’s just who I am,” he said.

O’Brate doesn’t operate completely off the grid; not hardly. He’s just not seeking the spotlight in any way.

He could live anywhere, but chooses to reside in Garden City (population 26,658 according to the last census), his home for the last 60-plus years. O’Brate continues to elevate Garden City through his businesses and his implementation of a master development plan, stoked by the hefty $55 million, but also his vision.

His philanthropic efforts spread wide, with many focused on aiding youth and those in crisis or need. In the fall of 2013, Cecil and Frances established the O’Brate Foundation, which provides college scholarships for students who are graduates of the foster care system or those who struggle below poverty level.

To date, the O’Brate Foundation has sent approximately 400 students to college with contributions in excess of $3 million.

“You give these kids an education, and you’ve helped them a long ways in life,” Cecil said.

The book, Making It Happen , is filled with copies of letters from congressmen and senators recognizing his rich contributions to the state of Kansas and specifically Garden City. There are notes from the governor of Kansas, too.

And then there are photos and notes revealing a tight relationship with former President George W. Bush , a relationship O’Brate considers the highlight of his career. The O’Brates were welcomed to Dallas for an annual Bush Christmas party and Cecil found a way to draw George to Garden City for a questionand-answer session with the locals, including students, firemen and business executives.

After O’Brate handled the introduction, Bush responded: “Cecil, thanks! It’s always good to be with a country boy made good.”

After his “I’ll be doggone” moment, Holder’s intrigue spiked. Who is this Cecil O’Brate? What’s his story? And where does Oklahoma State University fit within that story?

“I called him up, and he took my call out of the blue,” Holder said. “I introduced myself and said I’d like to come see him. He said, ‘What for?’ I said, ‘You went to Oklahoma State and we’ve never met. And we need to do something about that.’”

In April of 2015, Holder made his initial visit to O’Brate’s office in Garden City, where a 90-minute conversation played out.

“I took a yellow legal pad with me and made a lot of notes,” Holder said.

Holder still has that yellow legal pad, providing a fond memento of the start of a grand relationship he’s built with O’Brate. The notes

reflect O’Brate’s past, his many successful business ventures and one key revelation: the man still felt a connection to OSU.

“He would come back to an occasional ball game at that time,” Holder said. “He was a customer of the Bank of Oklahoma. Other than a football game, he had not been back for the 68 years since he had been a student.

Holder committed to changing that. O’Brate, he figured, could benefit from a reunion with the only college he ever wanted to attend.

And OSU could benefit, too.

Along with reconnecting with an esteemed former Cowboy, Holder was seeking a naming sponsor for one of the remaining finishing

touches to his ambitious vision of an Athletic Village: the new baseball stadium planned for the corner of Washington Street and McElroy Road.

“That one meeting led to him coming to Boone Pickens’ Mesa Vista Ranch that summer of 2015,” Holder said. “Then he came to multiple football games that fall. Then I went back to see him in April or May of that next year, and the relationship and the friendship and connection to Oklahoma State just kept getting stronger.

“It was always there beating in his chest, his love for the school and connection and all that means. We just needed to reach in.”

Holder and O’Brate proceeded deliberately with their budding relationship.

There were calls and meetings, in Garden City and Stillwater. The Cowboys A.D. delivered a new Oklahoma State license plate holder for O’Brate’s car to replace the one with the Powercat logo representing Kansas State, which had become the school of choice for his grandchildren.

When the Cowboys reached the College World Series in 2016, Holder had O’Brate join him in Omaha. As rain delayed OSU’s opener against Arizona, Holder seized the opportunity, escorting O’Brate into the dugout for an up-close look — of the stage, sure; but also to provide a peek at coach Josh Holliday and his staff, a group the athletic director holds in high regard as mentors and leaders of young men.

“We’re educators,” Holder said. “Coaches are in the business of educating. I believe baseball is one of the best classes taught on our campus. And it’s about a lot more than skills,

it’s about life lessons, about how to be a better father, how to be a better husband, how to be a leader in the community, how to be a risktaker and entrepreneur and change the world.

“Yeah, you came here because you had an interest in baseball. But oh, by the way, you’ve received life lessons that will go with you all the way to the grave.”

O’Brate watched the first few innings from his dugout seat. And he liked what he witnessed. Still does.

“I think he’s doing a good job,” O’Brate said of Holliday. “Educating these kids is an important job. It is to me, and it is to him.”

But was it all important enough to plop some money behind? A lot of money?

Holder would find out.

“Leaders like Cecil are rare, and many opportunities were missed because he was spending his time in places other than the OSU campus. There is a lesson there for all of us.”

— Mike Holder

Holder preferred driving from Stillwater to Garden City for his visits with O’Brate, not for the less-than-scenic 5-and-a-half-hour drive itself, but for what it represented.

“It makes a statement how important the relationship is,” Holder said, “to invest a full day for someone. It also shows you’re a good steward of money. It costs a lot more to rent a plane and fly to Garden City than to drive.”

One particular day, however — Dec. 22, 2016 — demanded something different. Christmas was closing in, and a departure for the Alamo Bowl was fast approaching. Time was an issue, and Holder was ready to truly gauge any intent O’Brate might have for impacting Cowboy Baseball.

So that day, Holder jetted into Garden City Regional Airport. Upon arrival, he found a surprise. O’Brate had arranged for a swap of Holder’s rental car, replacing a Ford Taurus with a Jeep Wrangler Sahara — bright orange

A sign? Perhaps. Because O’Brate would soon deliver an even bigger surprise.

Once behind the wheel in Garden City, Holder drove to an O’Brate hotel property in Garden City, where a lunch meeting with his executive team was taking place. When the meeting broke up, O’Brate said he’d catch a ride back to the office in the Jeep.

Holder had rehearsed for this moment in his mind many times over many months — “probably in my sleep” — and he braced for just the right opportunity to deliver the question on whether he could count on a gamechanging donation for OSU baseball, when O’Brate beat him to it.

“We’re just driving along the road,” Holder said. “All of a sudden, out of the blue, he looked at me and said, ‘I’m going to make a big gift for you.’”

Then it got better. Holder had previously asked for $20 million, but O’Brate announced he was in for $30 million. Later, when construction costs escalated, he kicked in $5 million more.

“After all that fretting and planning for what I was going to say,” Holder said, “I didn’t even have to ask him.”

Holliday looks back fondly on waiting out the weather for that College World Series opener in Omaha.

“Best rain delay I’ve ever been a part of,” he said.

The Cowboys coach, a former OSU baseball standout who grew up literally around the ball yard that is Allie P. Reynolds Stadium, where his dad Tom served as a coach, dreams about the future in O’Brate Stadium. It will be a sprawling complex that will offer many amenities catering to the team and its fans.

Allie P. served the program well, but time has relegated the old facility to the bottom of the Big 12. Cecil O’Brate, and others, are changing that.

“I don’t think you can put it into words,” Holliday said. “It’s funny, last year at the time of the announcement (the stadium was finally funded), our team was struggling, maybe below .500, just trying to jumpstart ourselves. From the day of the stadium announcement, it

created an energy among our group, coaches, players, fans. I saw a noticeable change in the way people felt about where we were headed.

“To drive by every single day and dream about what the future holds, the way Cecil said to give kids a chance to learn, to better the environment and give them an opportunity to become great, he’s made that opportunity for us.

“Such a special, special thing, to have a place you call home every day that will be the finest in the country. It’s going to pump pride through your veins every single day. It’s going to motivate you to chase excellence. And it’s going to make it a reality for us to be the very best. And that’s a gift.”

It took a while for OSU to reveal Cecil O’Brate as the catapulting factor in pushing the stadium forward, because, again, he prefers operating out of the spotlight. O’Brate even had to be convinced the stadium should carry his name.

“The more time Cecil spent in Stillwater, the more I grew to respect and admire him as a person and the more he connected with OSU,” Holder said. His gift was inspired by the way our people made him feel on game days. In the end, the gift was great, but his friendship and what he stands for is much more important than the money.

“My only regret is that we didn’t meet decades ago,” he added. “Leaders like Cecil are rare, and many opportunities were missed because he was spending his time in places other than the OSU campus. There is a lesson there for all of us.”

At age 90, O’Brate continues to work and work hard. But he’s taken some time to enjoy things, too, especially back home at OSU.

“I like to come to these games,” O'Brate said, “because I never got to do it when I was younger.”

One game in the future now looms extra special, when the Cowboys open their 2020 baseball stadium — in O’Brate Stadium.

“First one,” O’Brate said. “I'll be here.”

One didn’t need to say much to get his point across. One would talk to anyone within earshot. Another had his own version of the English language. You were constantly shaking your head trying to figure out what the fourth member of this group really had to say. And then, there was the calculating, efficient approach that still characterizes individual number five to this day.

Five head football coaches at Oklahoma State. Five unique personalities. Five different ways to communicate. Yet, Jim Stanley, Jimmy Johnson , Pat Jones , Bob Simmons and Les Miles all share a common bond. They all had a huge hand in paving the way for the gridiron success that OSU has enjoyed over the last several seasons. And, to steal a line from an old song — they did it their way.

I had the pleasure of working with five of OSU’s last six head football coaches — four on a daily basis while a member of the Oklahoma State athletic department and as color analyst on the Cowboy Radio Network. When you throw in the six years I covered the Cowboys under Stanley’s watch, I probably spent as much time with these men over a 32-year span as I did with some members of my own family.

When I take time to consider that I worked for six different athletic directors and with the five head football coaches mentioned here, I now realize — and appreciate — how hard so many people worked over the last four-plus decades to get this program to where it is right now. That old saying about embracing the past before you can enjoy the future, in my opinion, certainly applies.

Jim Stanley and I had a great working relationship. We enjoyed an even better friendship. True, I was a member of the media during Stanley’s six years at the helm, but we respected one another from day one. I didn’t tell him how to coach (although I offered some advice from time to time), and he didn’t tell me how or what to write.

Every year there was a fourto-six week window when things became a little tense. Keep in mind, the recruiting process was much different back in the 1970s. Unless OSU was going after a recognizable state high school or junior college prospect, the general public didn’t have a list of names to scrutinize weeks before signing day. For the most part, Cowboy fans didn’t have any idea who was coming on board until national signing day. There weren’t many recruiting services, websites, recruiting gurus or recruiting magazines that predicted the every move of a potential recruit.

But, part of my job was to name names for Cowboy fans. It wasn’t easy under Stanley. He kept a tight grip on that list. The circle of people who knew OSU’s recruiting targets was small. While there was no social media or hat games back then, there was still a need for both the school and recruit to enjoy the taste of publicity. So in exchange for names and telephone numbers, I promised to quote “sources” when writing about a

high-level young man thinking about making his way to Stillwater.

Each column seemed to irritate Stanley even more. To this day, I’ve never given up the name(s) of those on the Cowboy football staff who provided me the information I needed. But it was a win-win situation. I got the “scoop,” and OSU got the publicity.

Over the years, Jim and I laughed about how I managed “to get those names when that list was locked away in my desk.” He probably knew but chose to humor me.

I never met Bear Bryant , but after spending three and sometimes four days a week in the football office, I feel as if I knew him personally. Stanley was a Bryant disciple and former player. He learned how to play and coach when the game was not for the faint of heart. He was hard-nosed but fair. He was intense but sensitive when he needed to be. He believed in both mental and physical toughness. He had a John Wayne persona.

He took Oklahoma State to two bowls, tied for the Big Eight championship in 1976 (one play away from an outright title) and beat Oklahoma in Norman in 1976 to end a long Bedlam drought. His teams were as tough as they came. They reflected their coach.

Journalism professors will cringe when they read this, as will sports editors who warn against this very thing, but I knew Jim would be let go following OSU’s 62-7 loss in Norman in the ’78 finale. It was one of the two toughest columns that I ever sat down to write (the other predicting Paul Hansen would not return). Critics will point out the pitfalls of getting “too close” to the story.

I can assure you those people never met Jim Stanley.

Jim StanleyJimmy Johnson and his confident, talented staff of assistant coaches hit Stillwater shortly after Stanley emptied out his office. This group, for the most part, came from the University of Pittsburgh and took north central Oklahoma by storm. Jimmy’s energy level was in stark contrast to Stanley’s laid-back approach. OSU fans longed for the brash personality that this staff brought to Cowboy country. Over the next five years, Oklahoma State would become a legitimate player in the Big Eight and would go to two bowls.

Lost in Johnson’s five-year stay at OSU was the fact that many of his assistant coaches went on to become head coaches, and some even found their way to the National Football League. While their bravado ruffled a few feathers in and out of the league, these coaches walked the walk after talking the talk.

Perhaps it was Jimmy’s Arkansas background. Maybe it had to do with the fact that he never accepted the notion that Oklahoma State had to play second fiddle to Oklahoma. He knew, coached with and bantered back and forth with Barry Switzer. Although he never beat OU during his stay in Stillwater, he helped reshape the thought process when it came to playing the Sooners. He respected the Big Red of the south but didn’t fear the football monster that for decades had owned the state.

Jimmy’s “Press On” battle cry was quickly adopted by Cowboy fans. To be sure, there were highs and lows. The improbable road win (14-13) at Missouri in his first year set the tone for a 7-4 season (5-2 in the Big Eight) and Big Eight Coach of the Year honors for Johnson. I’ll forever remember Terry Suellentrop’s Herculean effort in Columbia that day. Fresh out of healthy backs after two physical losses at Arkansas and South Carolina, Sully came over from the defense to rush for over 200 yards. The Cowboy nation saw a great future for the program following that game.

Jimmy Johnson

Jimmy Johnson

Johnson’s lowest moment came in the season opener the next year. After a summer of bold predictions (“We’re going to knock their eyes out”), West Texas State came to town and stunned OSU, 20-19. OSU started 1980 with five-straight losses, won three of seven conference games and returned to earth with a 4-7 mark. The year ended in Norman on the short end of 63-14 drubbing.

While Johnson’s era was an elevator ride, it brought a new excitement to Lewis Field. It can be argued, and I totally agree, one of Johnson’s greatest contributions was bringing a ball of fire coach by the name of Pat Jones with him.

Ihave to admit upfront that Pat Jones was my favorite Oklahoma State head football coach. There are several reasons I still feel that way today. I worked beside Pat for 11 years. He was a heck of a football coach and, to those of us who really knew him, a great friend.

After Johnson bolted for Miami, the coaching search lasted just a matter of days. Players and fellow assistants were almost unanimous in their feeling that the next Oklahoma State head coach already had an office in the football complex. A defensive coach by nature, Pat also had the homespun way to communicate with fans and media. While entertaining to say the least, his 62 wins stood for the longest time as the most of any Cowboy head man. Ironically, Mike Gundy, one of his star pupils, has since taken over that honor.

Some of the greatest gridiron accomplishments in OSU history were under the watch of Pat Jones. Three 10-win seasons, four bowl appearances, national rankings in four of his first five years at the helm and the recruiting of OSU greats Barry Sanders , Mike Gundy, Hart Lee Dykes and Leslie O’Neal, just to mention a few, highlight his resume.

Pat and I did well over 200 radio and television shows together. My office for many years was just around the corner from his. We talked football, baseball and life in general on a daily basis. And all had that signature Pat Jones take when conversation came to an end.

There are too many memories to relive here. Being left after a road win at Wyoming might be one of my all-time favorites. Former Sports Information Director Steve Buzzard and I are still grateful for the ride we hitched that allowed us to get to the airport before the team plane left. Practice every afternoon when we’d see Pat “fire for effect” when he wasn’t pleased with the effort or execution. His reaction to phone calls when we actually took some on radio. He even played a huge role in highlight tapes that we produced all those years.

But those were behind the scenes memories. Winning 45-3 in his head coaching debut at Arizona State after some had predicted the Sun Devils to be national title contenders, the 31-17 win to open year two at No. 12 Washington, the 21-14 comeback Gator Bowl win over South Carolina for OSU’s first 10-win season. And so many others: the thrilling 35-33 Sun Bowl victory over West Virginia, the lopsided Holiday Bowl romp over Wyoming (Sanders, Gundy and Dykes put on a sensational offensive display). The list goes on and on.

Probation and lack of facilities took a bite out of the last six years. Even then, OSU battled on even terms with most of the big boys. Perhaps no head football coach at OSU endured more heartbreaking losses to Oklahoma. Half of those 10 losses were by two touchdowns or less, and then there was the 15-15 tie in ’92.

What makes Pat Jones an engaging radio host today made him a highly successful head college coach and longtime NFL assistant in years past. He was a throwback football coach with a unique personality. That combination, in my mind, was hard to beat.

Although he called Oklahoma State home for six years, took the Cowboys to the Alamo Bowl, won 30 games and, in my opinion, turned the Bedlam Series culture around in Stillwater, Bob Simmons might have been the most underappreciated head football coach in OSU history. I know that’s a pretty bold statement when you consider he was 30-38 overall and just 16-31 in conference play. The Cowboys were 13-20 over his final three campaigns, and that led to a change at the top.

So how could I use the word underappreciated when describing Simmons’ contribution to OSU football? Well, let me take you back to Nov. 9, 1995. OSU had just put the wraps on the final practice of the week. In less than 24 hours, the Cowboys would bus to Norman for a Saturday meeting with Oklahoma.

Oklahoma State was 2-7 on the season (1-4 in the Big Eight). OU was looking forward to another Bedlam win. Simmons stood before his team in the old Varsity Room and delivered this simple message, “You do what we’ve practiced all week, and we’ll win the game. I’ve gone against these guys a lot as an assistant at Colorado. We had success there. You can have the same success on Saturday.”

I recall thinking he must not realize that OSU had not beaten Oklahoma since 1976 and had only a tie during that span. To be honest, I thought he was doing everything he could to create a positive pregame mentality.

Well, we found out that Simmons knew what he was talking about.

Oklahoma State 12, Oklahoma 0.

The drought was over. OSU fans celebrated from border to border throughout the Cowboy nation. Stillwater looked like Times Square on New Year’s Eve as the party lasted well into the wee hours. The team was welcomed back like national champions.

As it turned out, this win was a preview of things to come. Under Simmons, OSU went 3-1 in his first four meetings with the Sooners. Two of those wins were posted in Norman, which made the accomplishment even more dramatic. Oklahoma had to battle to the end to nail down a 12-7 win in Stillwater in what turned out to be Bob’s last year and a national championship season for OU.

1995-2000

In 1995, after the win in Norman, as the players, coaches and support staff filed into the locker room, it was pandemonium. I arrived long before to get ready for the postgame radio show. I’ll never forget the exchange I had with Simmons, who looked as if it was just another day at the office. I said “Thanks for all us long suffering Aggies. We’ve waited for this forever.” He smiled and simply nodded. “The kids really played well.” And, with that short analysis, he joined the team to sing the fight song.

In the media get-together, someone asked Simmons if he would call recruits that night to tell them the final 12-0 score. “No. You all will do that for me the next few weeks,” he offered. And with that, the man who went 3-3 against Oklahoma, left the interview room and began his journey into Bedlam history.

Although Les Miles left the Oklahoma State staff for the NFL, he never gave up the hope of returning to Stillwater as the Cowboys’ head coach. I would talk with Les once a month and keep him up on what was going on at OSU. While he was knee deep in the pro game, he had more than a casual interest in the program that he left behind.

While visiting my oldest daughter and her husband in the Dallas area, I arranged to meet Les at Valley Ranch, which was then the headquarters for the Dallas Cowboys. My son-in-law and I spent about an hour walking and talking with Miles. Much of the conversation was about Oklahoma State.

I had no input whatsoever on Simmons’ replacement. But I was all in on the decision to bring Les back. I had grown close to the Miles family when he was drawing up offensive plays for the Cowboys. I couldn’t wait to work with him now that he sat in the head coach’s office.

What you saw is what you got with Miles, who took OSU to three bowls in his four short years in Stillwater. He was a ball coach who was passionate about the game and his team. No, he wouldn’t talk your ear off. In fact, if something could be said in 20 words, Miles would do it in 10. He was guarded and calculated in what he said. That part drove me bonkers from time to time, but I fully understood his personality and respected his approach.

On just a few occasions he let emotion and passion take over in a public setting. Remember those famous quotes “We’ll play those suckers anywhere, anytime” and “I guess we’ll figure out which team is which when we line up to play on Saturday against Oklahoma.” Never one to supply bulletin board material, Les always played things close to the vest. He even scripted his responses on his TV coaches show.

Les’ overall record at OSU was 28-21 (16-16 in the Big 12). But his numbers were very solid when you consider he got off to a 4-7 (2-6 in conference play) start.

Miles took what Simmons started in the Bedlam Series and continued to run with it. He was a key part of that successful stretch as a Cowboy assistant. A tough-minded, old school Michigan man, Miles wasn’t in awe of anyone. He considered himself as CEO of his company and made decisions accordingly.

Miles won his first two Bedlam meetings and split four games against Oklahoma. He will forever be part of OSU’s 16-13 magic in 2001 and the 38-28 pounding of the Sooners the next year in Stillwater in a game that was truly not as close as the final score.

He took OSU to the Houston Bowl in ’02 and the Cowboys beat a good Southern Miss team 33-23. That broke a four-year bowl drought and energized a fan base that turned Houston orange. The next year Ole Miss slipped by the Cowboys in the Cotton Bowl. Despite the loss, the fans continued to believe in the direction of the program.

Unfortunately, many fans will recall Miles in less than glowing terms over his departure to LSU. OSU was appearing in its third-straight bowl — against Ohio State in the Alamo Bowl. Rumors swirled throughout the bowl preparation that Miles’ stay at OSU was coming to an end. He tried to deflect the speculation and focus on the Buckeyes.

OSU was hit in the mouth early by the Buckeyes and routed 33-7. The Cowboys never really challenged Ohio State and that didn’t go over well with the thousands of fans who made — and paid for — the trip to San Antonio.

Some “insiders” said Miles was on his phone at halftime working out the details of his new contract. That was absurd and just an excuse for the embarrassing loss. Shortly after returning home, Les confirmed he was leaving. Those who said there was no way that could happen had egg on their faces. To this day, emotions are still raw over that decision.

I’m biased because of my friendship with Les, but I think he had as much to do with the current state of Cowboy football as any coach in school history.

I was truly blessed and fortunate to have known and worked with five of the most impactful head football coaches to ever roam the sidelines at Oklahoma State. They were in charge for 32 of the last 45 years and accounted for 185 of the school’s 586 wins heading into 2018.

There is no doubt Mike Gundy and the coaches and players he has brought to OSU over his 14 years at the helm deserve a tremendous amount of credit. They have turned the Cowboy program into a real force on the national scene. But the work of people like Jim Stanley, Jimmy Johnson, Pat Jones, Bob Simmons and Les Miles paved the way. And they did it with far less resources.

You must appreciate the past before you can enjoy the present and look to the future. That’s especially true when analyzing the current state of Oklahoma State football.

Taylor Lynch

Taylor Lynch

Taylor Lynch’s phone started ringing. She picked up, saw Madi Sue Montgomery’s name on the caller ID and quickly answered.

“I’m telling you before I tell anyone else,” Montgomery said to her friend.

“What’s wrong?”

Montgomery proceeded to tell Lynch how she had torn her ACL just days before her sophomore year of softball at Oklahoma State was set to begin.

The Burleson, Texas, native had traveled home to Centennial High School on Aug. 2, 2016, to take part in an alumni volleyball game at the school. Her father, Monty, had told her to be smart if she was going to play in the game.

Montgomery took part in warm ups, going through hitting lines with fellow alumna. She jumped up to spike a ball and all went as planned — until she landed.

“It felt like I landed on a pencil,” Montgomery recalled from the night she was hurt. “It wasn’t anything bad, my knee just kind of rolled a bit. Originally I thought it was just going to be sore for a little bit.”

When Montgomery returned to Stillwater the next day, she met with the softball team’s athletic trainer, Claire Williams, and had the bad news dropped on her.

Torn ACL.

She then made the call to Lynch. It was the same call the two had shared five years prior when they were freshmen in high school — with the roles reversed.

“It was weird that both of us have had to have that phone call,” Lynch said. “But it was nice because I knew exactly what she was going through.”

When Lynch tore her ACL as a freshman at Red Oak High School, her first call was to Montgomery. The phone call five years later was just the latest in a series of shared memories for the friends that have known each other since they were six-years-old.

The teammates have been in the same dugout for more than a decade now.

Richard Lynch and Braden Montgomery always knew their sisters loved to watch them play baseball. They knew that Taylor and Madi Sue would always be there to cheer them on, no matter if they struck out or hit a grand slam.

But what they didn’t know was that they would be the reasons that both younger siblings first picked up a bat and glove.

“I always wanted to be like him,” Taylor Lynch said of her brother. “I wanted to play baseball, and when I figured out that I couldn’t, I started playing softball and everything just took off from there.”

Taylor's desire to be just like her older brother helped carry her to places she never thought she’d reach.

“She was always hanging out with me and my buddies,” Richard Lynch said. “She was always trying to be one of the guys and would mess around with us out on the field because she just wanted to be part of the group. It has been crazy to see how she’s developed over the years from being such a little runt and then turning herself into a D-I athlete.”

The bond between siblings was unbreakable growing up, even through long afternoons when Richard would pepper balls back at his sister for hours, with the occasional one skidding past Taylor’s glove and colliding with various body parts.

Richard would remind Taylor that she didn’t need to worry about the pain. He was hard on his sister, constantly striving to see her become the best that she could be, and he also knew that no matter how much she hated him for it at the time, his efforts would prepare Taylor for whatever came her way.

“He has always expected the best from me, and I never wanted to let him down,” Taylor said. “That was always my motivation.”

The profound impact that brothers had on the Cowgirls helped shape the two into the prominent people they are today, but it was a two-way street.

“I knew that whatever I did had an impact on the way she perceived life,” Richard said. “If I did something detrimental, I had to think about how that would affect her. I had to think about what she would say to me.

“She honestly made me a better person.”

“Maybe we weren’t necessarily competing for the same spot, but we’ve always driven each other to constantly be better or to take the next step.”

As Lynch and Montgomery sat on the brown leather couch that lines a wall inside the Oklahoma State softball clubhouse, they reminisced on the memories they shared growing up as teammates and friends.

Trips across the country for travel ball tournaments, long car rides and plenty of nights spent at hotels in states far, far away from their native Texas filled their thoughts. The talented tandem remembered talking to friends back home and asking what they did on the Fourth of July.

They wanted to know what other kids did during the summer because they already knew what they would be doing — playing softball.

Montgomery and Lynch first joined forces at age 10 when they began competing with the Texas Glory, a travel-ball organization based in north Texas. But prior to that, the two came across each other as opponents quite frequently in the four years that preceded their partnership.

“We played against Taylor a lot. We could never get her out,” said Monty Montgomery, Madi Sue’s father and longtime coach. “She was a slapper and speedster that was constantly wearing us out. Eventually, I decided that if we couldn’t get her out maybe we could convince her to come play with us instead.”

“She pitched and had a really good curveball. I knew she was the best kid and had the best arm on her team,” Lynch recalled about the times she faced Madi Sue growing up. “I was always like ‘I need to get a base hit or something’ because I knew how good she was and there weren’t many kids as good as her at that age.

“We both knew that we were the toughest outs on our teams, and we had that sort of competitive nature built up between us.”

The first time the two faced off came when they were just six-years-old, and over the years that followed, the competitive fire that existed between the two softball stars was stoked quite often.

Their relationship blossomed even further after they became teammates.

After sharing a dugout, Lynch and Montgomery trusted each other like sisters, but the competitiveness remained. It’s something they credit for the success that they have had, even now after being named All-Big 12 performers in one of college softball’s premier conferences.

“I think our competitiveness with each other has definitely helped us along the way,” Lynch said. “Maybe we weren’t necessarily competing for the same spot, but we’ve always driven each other to constantly be better or to take the next step.”

That competitive fire saw both become stars within the Texas Glory organization and achieve success in all corners of the country as teammates. It has also been something that Monty Montgomery has been happy to see exist between the two because he knows how it will help them later in their lives.

“You need that competitive drive throughout your whole life,” he said. “They’re playing softball now, but as they grow up and get into a competitive workplace it’s one of those life lessons that’s good for any time. You don’t have to win at everything, but you have to be able to be your best at everything. It’s hard to do that daily, but they’ve practiced and worked hard and shown that they have that mindset.”

“I NEED TO GET A BASE HIT, OR SOMETHING”

It was a hot and muggy fall afternoon in Burleson, Texas. The sun beat down on Centennial High School’s infield dirt as Madi Sue Montgomery stood at shortstop, just inside the outfield grass that still held its deep green hue from the spring and summer.

Taylor Lynch stepped into the batter’s box at home plate clad in a maroon jersey that featured “Red Oak” in bold white letters on the front and a white No. 6 on the back.

To those that didn’t know them, it was just another routine at-bat in a meeting between the high schools of Lynch and Montgomery. But to keen observers, the red, white and blue Texas Glory glove that Montgomery wore at short was the same one Lynch wore when she took the field in the bottom of the inning.

Although they were in opposite dugouts during high school contests, the two always saw themselves as teammates first. By using their travel-ball gloves, the two made sure the whole world knew it, too.

“Everybody knew we were teammates because we used our red, white and blue gloves,” Lynch recalled. “Those weren’t even our school colors.”

The meetings between the two in high school never fell at critical junctions in the season, which allowed for more freedom between the travel ball teammates.

“It was really nice playing her in high school,” Montgomery said. “It was never during districts so we didn’t necessarily care all that much when played against each other.”

Remembering those days spent in the pounding Texas heat brought smiles to the faces of both OSU players as they reflected on just how far they had come together and how they already knew they’d be teammates again for years to come.

“(Recruiting) started early for both of us,” Montgomery recalled. “I committed to OSU during my sophomore year.”

“In December,” Lynch added. “Because I committed in January, and that’s the only reason I remember it.”

Both of the talented Texans winding up in Stillwater was not something they’d planned. Like most great things in life, the individual journeys that led them both to Oklahoma State is a story that seemed to be written in the stars.

“We didn’t think we’d necessarily end up at the same spot,” Montgomery said. “But knowing her family and my family, we both knew that we wanted to stay close so there was a slight chance. But it wasn’t a ‘We’re going to the same place’ type of thing. It just happened.”

The way Montgomery and Lynch constantly found themselves in each other’s lives seemed to be a strange coincidence. Time and time again, the two were side-byside at major moments, none more so than the day they found out that Lynch would be joining Montgomery in the Cowgirls’ 2015 signing class.

That day, they were hitting in the Glory’s batting cages together when former OSU head coach Rich Wieligman and their travel-ball coaches walked up to the cage and started talking to Lynch.

After the conversation ended, Lynch darted over to Montgomery and told her the good news.

“I think I’m going to be with you,” Montgomery recalled Lynch saying at the time.

“I can’t even tell you how many years that I’d hit behind her. Whether it was the twohole or in the three-hole, it was always her and then it’s me every single year. Just knowing that we’d still have that was nice.”

After Lynch made her collegiate decision, the bond between the two continued to strengthen as they shared unique experiences that most go through by themselves.

“I remember that we would go to football games together, and we always went to the same camps,” Lynch said. “We tried on our first OSU jersey together and all that stuff. It’s just cool because you don’t every really get to go through the whole recruiting process together, and we got to start together in sixth or seventh grade and have gone the whole way since then together.”

There are few moments more profound in a college student’s life than move-in week as a freshman. That theory held true for the two Cowgirl softball stars, but not everything went according to plan for Montgomery that first week.

Shortly after unpacking and beginning to settle into a new room, a new town and a new state, Montgomery was called home to Texas after her grandfather passed away. Suddenly, her first week of life as a college student was thrust into chaos, but fortunately she still had her close friend to rely on throughout.

“I had all of this excitement of moving into the dorms and all that and then I had to go home, but the entire time I was texting Taylor asking how things were,” Montgomery said.

That bond that the two had built over years of time together both on and off the field would help carry them through their successful freshman seasons in Stillwater.

“You see so many kids come in and struggle because typically you don’t know anybody there that you’re playing with or you’re not that close with them yet,” Lynch said. “But with us knowing each other and being in each other’s lives for forever and then coming to the same school, it was easy for us because we knew we always had at least one person that we could go to.”

With both Cowgirls now living more than 275 miles away from home, their families, and coaches, they were thankful to know that they still had someone to lean on in tough times.

“It’s really cool to know that she has a teammate like Taylor that just knows what she’s all about and helps her continue to be that way,” Monty Montgomery said.

“I think the comfort of having people that you know is a big deal,” OSU softball head coach Kenny Gajewski reaffirmed. “They don’t hang out a ton off the field here, but they’re really good friends and they may be best friends. They have found their own paths but are still obviously great friends and just knowing that you have someone you can always call is a great thing.”

Together, Lynch and Montgomery pushed each other to new heights as players and became stalwarts of Coach Gajewski’s lineup almost immediately, with Montgomery beginning her collegiate career as an outfielder and Lynch at third base. But their early success didn’t come without effort and hard work.

The pair lived in Bennett Hall as freshmen, a hop, skip and a jump away from Cowgirl Stadium and a place they would become very familiar with — the batting cages.

“We were in the cages almost every single night,” Lynch said. “There were nights where maybe I didn’t want to go to the cages, and she would tell me that we had to go. I think that’s us. We’ve always been strong when the other is weak, and weak when the other is strong. We’re definitely a little bit on the opposite side of each other as people, but it balances out and it has helped us tremendously over the years.”

Lynch and Montgomery were in the cages so much in fact that OSU baseball coach Josh Holliday took notice one night and reached out to Gajewski to let him know what he was seeing.

“We’ve always been strong when the other is weak, and weak when the other is strong.”

“I remember getting a phone call from Coach Holliday one night,” Gajewski recalled. “He told me it was the first time in his five years that he had seen my team up there at night. He wanted me to know that because as coaches we don’t always see what they’re doing on their own time. They forced some of our older kids to wake up and see that they needed to get up there and work as well.”

Late nights spent at the corner of Duck and McElroy marked the beginning of a new era for Cowgirl softball, and the culture shift that occurred was spurred by players such as Lynch and Montgomery.

The new energy that surrounded the program sparked a Cowgirl squad that won 32 games in Gajewski’s first season despite facing a rash of injuries and having countless new faces in the program. At season’s end, Lynch, Montgomery and the rest of their team sat anxiously in hopes that their name would be called during the NCAA Tournament selection show.

At the watch party, Montgomery and Lynch stood side-byside, hand-in-hand, nervously staring at the television screen.

“Coach G was putting in our heads all day that we might not make it.” Lynch remembered from that day.

“I think we all kind of knew why he was saying that, but we didn’t know for sure. It was our first year so we didn’t know if our record was going to be good enough to get in,” Montgomery added. “Taylor was just holding my hand, and I could feel her shaking. We saw our name pop up, she looked at me and goes ‘Oh my God!’”

“That first selection show is probably my favorite memory, and if it’s not, it’s in my top three,” Lynch said. “It was so surreal. We were actually making this program better, and we were going to regionals as proof of that.”

With the selection show behind them, the duo that had shattered OSU records as freshman — Lynch compiling a program-best 23-game hitting streak and Montgomery’s 57 RBI the most ever by a Cowgirl freshman — went back to work, preparing for a regional trip to Athens, Georgia. There the Cowgirls staved off elimination three-straight times before falling to No. 16 Georgia in the regional championship game.

The loss marked the end of a wildly successful freshman year for both Lynch and Montgomery, but the two stuck together through it all and their success as teammates only grew in the years that followed.

Three years into their collegiate careers, both Lynch and Montgomery have scattered their names throughout

the OSU record books and have already left a lasting mark on a revitalized program. Whether it’s career batting average, home runs, runs batted in or almost any other stat in between, the Texas tandem has produced at a level equal to, or greater than, some of the iconic names in Cowgirl softball lore.

Heading into the 2019 season, they stand as the only two players to be a part of the OSU roster during the first four seasons of Kenny Gajewski’s tenure as head coach.

“I think for this coaching staff, they’re two very, very important people,” Gajewski said of the duo. “They’ve been pillars in our lineup and our program. They’re mainstays. Every day we know that two of our nine are set. I just can’t say enough about what they’ve meant to this program and what they continue to mean to us as coaches.”

“Being the first four-year kids is cool, and I know that we both take pride in that,” Lynch said about her and Montgomery’s distinction. “We mess around a lot, but at the end of the day we know how special it is. We feel like this is our team and this is our year that we’re going to lead this team to wherever we’re going to go.”

But the record-setting numbers and statistics are not why Gajewski will remember Lynch and Montgomery after they graduate in the spring.

“They’ve always taken the younger kids and helped guide them through everything. That’s not a trait that every kid has,” Gajewski said. “I told them that their legacy — and it’s what I told (Vanessa) Shippy last year — is not going to be their numbers. Their legacies are not their numbers, but the mark they’ve left on their teammates and what type of people they are.”

Lynch and Montgomery have always been leaders but have also always gone about leading others in different ways.

Montgomery, never one to say more than necessary, has always been cast perfectly in the role of leading by example, while Lynch has tackled the other half of the equation perfectly and is often referred to as the “voice of the locker room.” Together, just like in their relationship with each other, they create a perfect balance that has helped prime the Cowgirls for 2019.

They have had front-row seats to the success of the past three seasons and to the potential that this year’s group possesses. But what they also understand is that their work as leaders, and as agents of change, is never truly finished.

“We want to make sure we leave this program better than we found it,” “Lynch said. “I know that we’ve done that, but we have to continue to improve on it. That goes above graduation and continues afterward because we’ll always have that brand on our chests as OSU softball players.”

“We came here to change a program, and we’re not done until we’re done,” Montgomery added. “And I know that we can look back on everything in however many years and know that we did exactly what we wanted to do.”

Both players have spent countless hours working to change the Oklahoma State program over the past three seasons. In that time, they have seen some of their childhood friends live out dreams of playing in the Women’s College World Series.

Now, Lynch and Montgomery are ready for their turn in the spotlight.

“Our motivation as seniors only grows because now we have something to look back on,” Lynch said. “We are not going to go to

a regional final and lose because we know what that feeling is like. I think that drives us a little bit more.

“We love watching our friends’ success and everything they’ve done, but we’re ready for our turn.”

With one year left as teammates, Lynch and Montgomery stand together, the pillars of a program, with more than a decade of history between them. They know how far they’ve come and what they still want to achieve, but regardless of the result, the two will always have limitless memories to fill a lifetime of friendship.

“During my hitting streak, she was one of the first people to say anything to me, and I know when she broke the home run record last year (15 in a single season) I sprinted out to celebrate even though I’d just had a horrible at-bat,” Lynch said, recalling just two of the moments she has shared with Montgomery. “It’s little stuff like that, and we’ve been able to see each other have those moments for a long time. It’s cool to be able to say we’ve seen each other do all that stuff since we were 10.”

“It wasn’t necessarily pretty in the way it worked out, but God knew what he was doing by putting Taylor and me together,” Montgomery said. “I don’t think that either of us would’ve guessed that we would’ve done what we’ve done so far, but we’re not done either.

“I can promise you that.”

“There was this one time your dad …”

For 10 current student-athletes at Oklahoma State University that is an all-too-common phrase heard on and around campus. But since many of their dads are part of Cowboy athletic royalty, they have gotten used to sitting and listening, watching old loyal and true followers’ eyes light up as they recount great plays and unforgettable moments.

STORY BY ROGER MOORE

STORY BY ROGER MOORE