TH E VILLA BARBARO AT MASER

Science, Philosophy, and the Family in Venetian Renaissance Art

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

Denis Ribouillault

An imprint of Brepols Publishers London / Turnhout www.harveymillerpublishers.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

isbn 978-1-915487-02-5 d /2023/0095/227

Copyright © 2023 Harvey Miller Publishers

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Harvey Miller Publishers.

Designed by Paul van Calster

Printed and bound in the EU on acid-free paper

Preface 6

INTRODUCTION 8

The family and their artists: A portrait gallery 9

Setting up the investigation: Historiography and method 28

Notes 36

Part One

THE WOMAN IN WHITE 42

I The sundials 43

II Daniele Barbaro the astronomer 51

III The cosmos in a villa: The Hall of Olympus 55

IV The identity of the woman in white 62

V When the Sun meets the Moon: A dragon story 71

VI Eclipses, the writing of history, and the reform of the calendar 78

VII The Room of Virtues: Daniele Barbaro between reason and faith 80

VIII The Room of Fortune and Venetian geopolitics 90

Notes 95

Part Two

DELOS IN TERRAFERMA 104

I The entrance to the villa: Time, the sea, and a marriage 105

II The double-headed eagle: Francesco Barbaro, Venice, and the East 117

III Welcome to the villa: The concept of hospitality and Villa Barbaro as a theater stage 126

IV The Hymenaeus Room: Untying the girdle 133

V The Bacchus Room: The civilizing process 141

VI Keeping the fire alive: The chimneypieces in the Hymenaeus and Bacchus rooms 145

VII The Cruciform Hall, Part 1: Childbirth 149

VIII The Cruciform Hall, Part 2: Crusade 164

IX The nymphaeum: An image of fertility 169

X The grotto: Socrates, Daniele Barbaro, and the immortality of the soul 173

XI The ten statues of the hemicycle 180

XII Civil happiness 193

Notes 202

CONCLUSION 216

Notes 225

Epilogue

MARINA VOLPI, TOMASO BUZZI, AND THE “RESTORATION” OF THE 1930 s 226

Notes 235

General Plan of Villa Barbaro 239

List of Illustrations 240

Bibliography 248

Indices 267

The woman who first gives life, light, and form to our shadowy conceptions of beauty, fills a void in our spiritual nature that has remained unknown to us till she appeared. Sympathies that lie too deep for words, too deep almost for thoughts, are touched, at such times, by other charms than those which the senses feel and which the resources of expression can realise. The mystery which underlies the beauty of women is never raised above the reach of all expression until it has claimed kindred with the deeper mystery in our own souls.

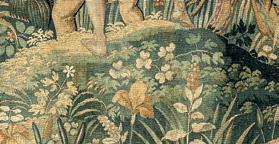

Villa Barbaro at Maser is a wonderful example of what could be called “cosmic architecture,” that is, architecture linked to the wider coordinates of the surrounding landscape and the cosmos. Like the botanical garden at Padua with its cosmological parterres, built around 1545 under the aegis of Daniele Barbaro, it is related architecturally to the cardinal points and harmoniously connected with the larger landscape (Fig. 29).1 The chosen site corresponds to the descriptions that Pliny the Younger gave of the landscape around his famous villas (Letters 2.17 [Laurentine] and 5.6 [Tuscan]). Built on a slight elevation, the villa looks southward over a vast expanse of cultivated land, its back nestling at the foot of the chain of hills called colli asolani after the nearby town of Asolo. The villa, with its creamy color, stands out beautifully against the wood of dark trees that now covers the hill, a part of the garden that was redesigned in the twentieth century by the landscape architect Maria Teresa Parpagliolo Shephard (1903-1974).2 This landscape was already famous when Daniele and Marc’Antonio visited the villa as young men. It had been elevated to the rank of work of art by the poetry of Pietro Bembo, especially his famous poem on love, Gli Asolani (1505), written at the court of Caterina Cornaro, queen of Cyprus, at

Asolo, and found a visual translation in the painted poesie of Giorgione, Lorenzo Lotto, and other Venetian painters.3 As Rudolf Wittkower and others have shown, the architecture of the villa is marked by strict symmetry and by harmonic proportions derived from the study of ancient architecture, echoing the mathematical-musical structure of the cosmos.4

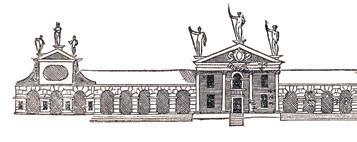

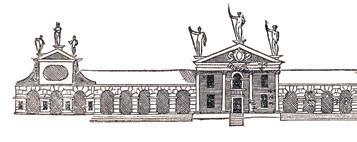

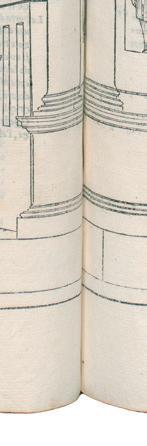

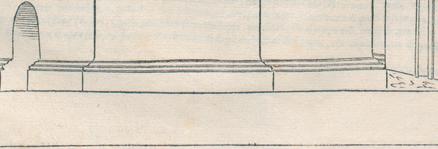

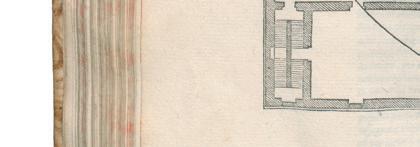

Today, two monumental sundials adorn the dovecots, or columbaria, placed at each end of the villa’s extended wings. The one at the eastern end is a zodiacal calendar indicating the seasons, while the other, at the western end, indicates the hours (Figs. 6, 30). In fact, these two sundials were only made in 19361938 by the architect Alberto Alpago-Novello (1889-1985), also a specialist in gnomonics and, interestingly, the author of a fascinating series of photographs of Maser and its surroundings taken during the First World War when he was a military engineer.5 Alpago-Novello had been called by his friend and colleague, the Italian architect Tomaso Buzzi (1900-1981), who restored the villa from 1934 onwards. The models, drawings, and correspondence with the owners, Marina Volpi da Misurata and her father Giuseppe Volpi da Misurata, regarding the project for the sundials at Maser are all preserved at the Archivio Buzzi at La Scarzuola and discussed in the epilogue of this book (Figs. 31, 32).6 There is no evidence to date that these new sundials were intended to recreate the original program devised by Daniele Barbaro for the villa. Indeed, sundials do not appear on the engraving of the villa in Palladio’s I quattro libri, although this is true of most of the statuary and decoration of the facade in that image (Fig. 33).7 They do not appear either on the plate from the late eighteenth century published

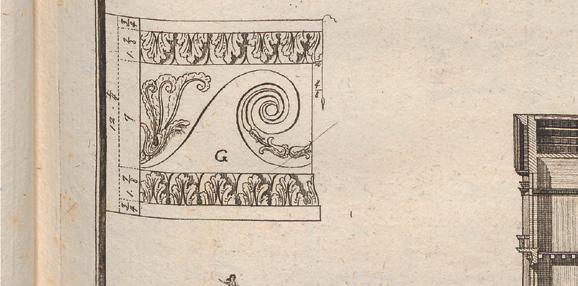

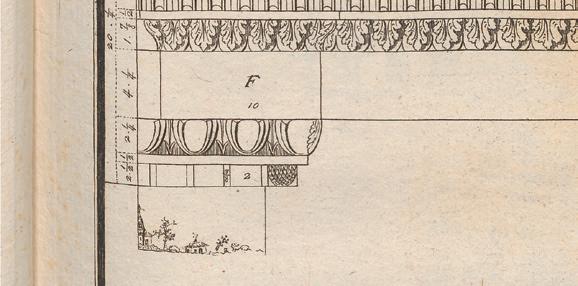

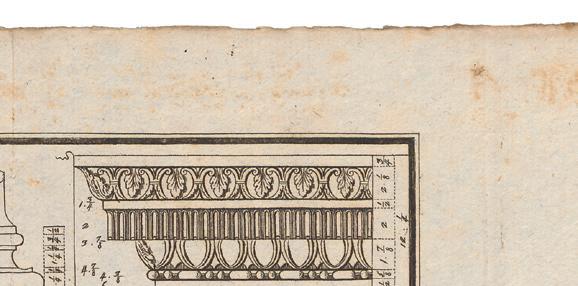

in Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi’s Le fabbriche e i disegni di Andrea Palladio, although this time the sculptures on the pediment are clearly legible (Fig. 34).8 In addition, old lithographs and photographs dating from the end of the nineteenth century and therefore taken before the restorations of the 1930s, show a completely different situation (Figs. 35, 36). On the east wing, we see a sundial that indicates local hours (Fig. 37). Oddly, this sundial is located at the center of a large zodiacal wheel. This configuration cannot be dated to the sixteenth century and the sundial itself does not correspond to the ways sundials were made at that time.9 However, it echoes the design of Renaissance astronomical clocks such as the one at Piazza San Marco in Venice (1496–1499).10 A description of the Maser clock from 1921 specifies that “the dominant colours are vigorous reds, blues and yellow,” which corresponds to the strong colors used for public mechanical clocks.11 In a recent contribution, Maria Losito pointed out that the design on the photograph resembles that of an ornament for the “hidden parts of gables” (“parti occulte de i Timpani”) appearing in an illustration in Barbaro’s famous commentary on Vitruvius’s De architectura. The legend explains that the design refers to a hydraulic clock (Fig. 39).12 Could this mean that the design shown in Figure 37 originally belonged to a mechanical clock, now lost? The presence of clocks on the facades of villas is not unprecedented. Those on the bastions of the great Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola, for instance, date from 1581. However, it is very hard to imagine the precious machinery of a mechanical clock being located amongst the droppings of pigeons flying in and out of the columbarium.

The photograph also shows a woman sitting on clouds in the center of the zodiacal wheel (see Fig. 37). Held by two putti and with a large billowing veil, she holds a torch in her left hand while throwing something with her right hand. She has all the features of Aurora, goddess of the dawn, sprinkling flowers as she brings forth a new day. On the dovecot located on the opposite side, a pendant fresco shows the winged figure of Father Time or Chronos with his great scythe and an hourglass (Fig. 38). Located at the western end of the villa’s facade, where the sun sets, he may symbolize the end of the day. Time is surrounded by four smaller scenes from the life of Christ, while roundels containing portraits of men (astronomers

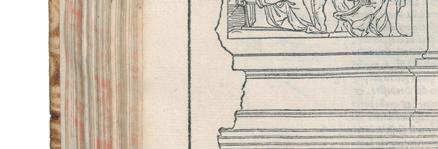

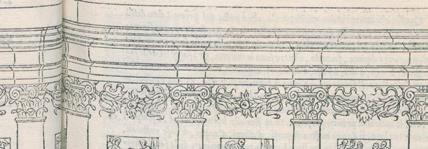

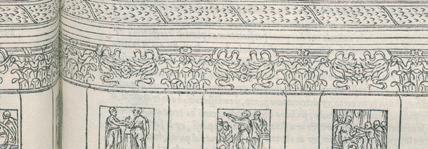

Christoph and Johann Chrieger, Villa Barbaro, 28.8 × 19.5 cm, in Andrea Palladio, I quattro libri dell’architettura di Andrea Palladio

(Venice: Dominico de’ Franceschi, 1570), bk. 2, p. 51. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 41.100.126-(2.51). Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If the wall space in the hall is used to represent the material world of the villa, with its harmonious domestic life and the peaceful landscapes of a utopian terraferma , the vault is logically devoted to the representation of the heavens. Veronese included details that link the two parts of the decoration, thus evoking the astral influence on the sublunary world in which Daniele Barbaro and his contemporaries believed. One such detail is the great sunrays piercing through clouds in several of the landscapes (Fig. 42). To us, these may appear to contribute to the rather romantic vision of Veronese’s imagined landscapes, but to a Renaissance visitor they might also recall Barbaro’s own words about “the effects that the rays of the shining bodies of Heaven have on the world” (“gli effetti che fanno i lucenti corpi del Cielo con i raggi loro nel mondo”).60 Much more decisive details are that the woman in white at the center of the vault is looking towards Giustiniana, and that the two beautiful young women resemble each other almost perfectly, as if they were two versions of the same person, one earthly and the other heavenly (Figs. 17, 24, 28, 44). While it is true that Veronese’s women have highly idealized likenesses and characteristics, which they share across different formats, genres, and iconographies, we will see later how our new identification of the woman in white explains the special relationship between the two women and the crucial position of Giustiniana’s portrait in the room.

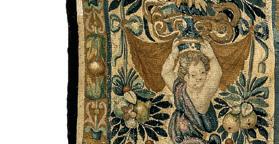

Mythological and allegorical figures occupy the vault and the lunettes on the upper part (Fig. 44). The personifications of the four seasons are depicted on the two large lunettes (Figs. 99, 100) and the four elements Juno (Air), Vulcan (Fire), Cybele (Earth), and Neptune (Water) are located in the four corners of the vault. Alternating with the four elements, Veronese painted, in elaborate cartouches, four allegories in imitation of white stucco reliefs standing out against a dark background. The three female figures are personifications of Fortune (Fortuna) with her wheel, Abundance (Annona ), and Fertility or Mother Nature, shown with multiple breasts from which milk is sprinkling. The fourth compartment shows Cupid Stung by Bees, an allegory of the sadness and pain that can accompany love.61 The ceiling opens up to a view of the heavens with the seven planetary deities (five wandering stars and two luminaries, the Sun and the Moon), carrying their attributes, seated around a trompe l’oeil octagonal frame. Each planet is

associated with the zodiacal signs over which it rules according to classical astrology. These are discreetly painted in grisaille on the outer ring of clouds underneath each deity. Reading counterclockwise, the sequence is: Diana (Moon) / Cancer; Mercury / Virgo and Gemini; Venus / Libra and Taurus; Apollo (Sun) / Leo; Mars / Aries and Scorpio; Jupiter / Sagittarius and Pisces; Saturn / Capricorn and Aquarius. This sequence of planetary rulers, also called chronocrators or lords of time, corresponds to the seven spheres of Ptolemy’s system, with Earth at the center (Fig. 43). The number seven was also associated with the days of the week, each planetary god ruling the universe one

Finally (for whatever reason) we are on earth, men and women, almost in the middle of a theater; and all around us, on all sides of heaven, sit the gods, all eager to witness the tragedy of our existence. We, therefore, whose end is to please the spectators, must strive to appear on the stage in such a way that we can be praised when we leave it.

At Villa Barbaro, the theme of the domination of the seas is much more important than the almost insignificant detail of the meridian line on the globe of Fortune in the Room of Fortune might suggest. In fact, it is the first theme that a visitor encounters when arriving at the villa. Neptune’s Fountain is located in the center of a hemicycle at the crossroads of the public road and the main ceremonial axis of the villa, which extends beyond the road into fields that were once family property (Figs. 80, 81). The god of the seas stands in the middle of a large shell-like pool, accompanied by a dolphin and supported by four seahorses, the animals that traditionally drive his carriage. The octagonal pedestal of the fountain is decorated on each side with the motif of a mermaid. Like other statues of Neptune in Venice and elsewhere, the statue represents the seas and may indicate here maritime power, in particular the commercial activities that enabled the Barbaro family to acquire its wealth.1 Documents show that in the mid-sixteenth century the family owned several ships, which were used especially in the salt trade on the routes to Cyprus

(Finalmente (qual che si sia la cagione) noi siamo in terra huomini, & donne, quasi in mezzo di qualche theatro; e d’ogn’intorno per ogni parte del cielo siedono li Dei, tutti intenti à guardare la tragedia dell’esser nostro. Noi adunque, il cui fine altra cosa esser non dee, che’l compiacere à gli spettatori; sotto tal forma dovemo cercar di comparer nella scena, che lodati ce ne possiamo partire.)

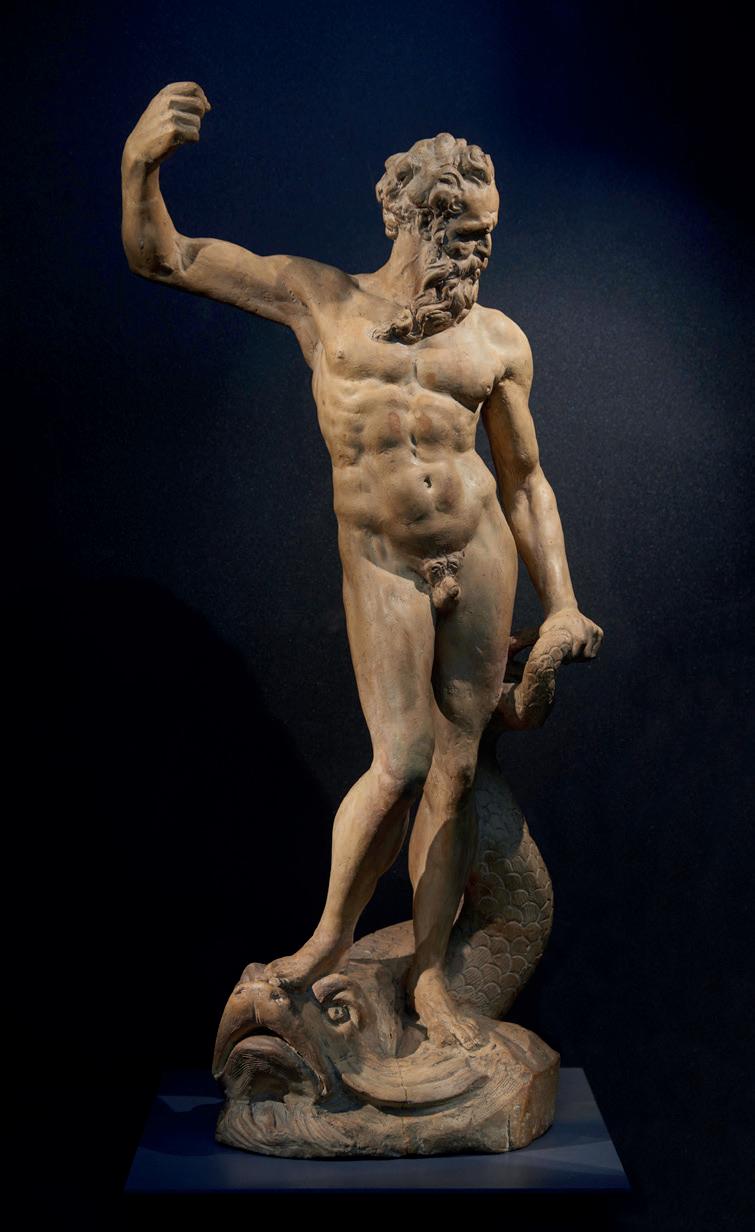

and Syria for instance, the Barbaretta (built in 1551), the Barbara Grossa (1556), and the Barbara (1563).2 This statue, like the other statues in this part of the garden, cannot be attributed to Alessandro Vittoria. As mentioned in the Introduction, it is probable, though not proven, that they were added later (perhaps in the 1580’s when the Tempietto was built or in the late seventeenth century). In any case, they fit in harmoniously with the rest of the decoration and therefore deserve to be included in our reading of the villa.3 Alessandro Vittoria produced several smaller figures of the same subject in either terracotta or bronze, especially for door knockers decorating the entrance doors of Venetian palaces (Fig. 82).4

The Neptune Fountain is flanked to the west by a statue of an old, bearded man with a scythe representing Saturn, the oldest of the gods (Fig. 83). The god holds his beard in his hand in a gesture that reminded me of the figure of Joseph in Michelangelo’s Madonna del Silenzio (ca. 1538), a meditation on time and the inevitability of death known through many copies and Giulio Bonasone’s engraving of 1561. Here Saturn stands as Chronos, the god of time, an image of how time eats everything in its path, or, to quote Ovid, “tempus edax rerum,” time devours all things. To the east, a statue of Fortune stands with her foot on a globe (Fig. 84). Fortune appears here typically with Occasio’s forelock, i.e., Opportunity, which must be seized by the hair, as the virtuous man seizes his destiny. The statue at Maser is reminiscent of the figure of Occasio (the female equivalent of Kairos, the opportune moment) in the famous fresco by

Hemicycle at the entrance of Villa Barbaro, Maser, seen from the main driveway with, from left to right, statues of Fortuna, Mars, Neptune, Minerva, and Saturn.

Photo: author by permission Villa di Maser—Patrimonio dell’Umanità—unesco

Neptune’s Fountain, after a design by Alessandro Vittoria (?), ca. 1558–1560 (?), sandstone, Villa Barbaro, Maser. Photo: author by permission Villa di Maser—Patrimonio dell’Umanità—unesco

Alessandro Vittoria, Neptune, ca. 1566–1567, terracotta, height 53.4 cm. London, British Museum, no. 1896,0612.1. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Saturn, after a design by Alessandro Vittoria (?), ca. 1558–1560 (?), sandstone, Villa Barbaro, Maser.

Photo: author by permission Villa di Maser— Patrimonio dell’Umanità—unesco

fig. 84

fig. 85

the School of Mantegna at the Museo della Città in the Palazzo di San Sebastiano in Mantua (Inv. No. 1105) (Fig. 85).

The two statues flanking the Neptune Fountain thus express two opposing but complementary notions of time, the eternity of time and the fleeting moment, as Chance or Opportunity.5 Together, they reflect a conception of time and chance typical of the Renaissance, fundamentally linked to the idea of virtue and human destiny, a subject on which Aby Warburg, Erwin Panofsky, Edgar Wind, Rudolf Wittkower and, more recently, Simona Cohen and Barbara Baert, among others, have written at length.6 They also announce an important theme developed inside the villa in the Room of Fortune, where, as we have seen, Veronese depicted both Saturn as an image of time and Fortune as a force necessarily harnessed by virtue (Figs. 75, 76). Furthermore, the two statues of Saturn/Time and Occasio/Fortuna framing the Neptune Fountain provide an immediate echo to the iconography of the two dovecotes devoted to the passage of time and the course of the sun,

fig. 86

discussed at the beginning of Part 1, with Father Time and Aurora (Figs. 37, 38). Such iconographic concordance shows that, regardless of whether or not these elements belong to the original program, the iconography of the sculptures in the garden is closely related to the iconography of the facade and the paintings inside the villa. The decoration has a clear iconographic unity, with the different parts echoing and complementing each other. In this regard, it is also worth noting that Aurora does not only symbolise the dawn. In Roman religion, Aurora was the equivalent of Mater Matuta (“mother of the morning”), a goddess who protected childbirth and children, associated with virtuous young matrons, and closely related to Fortuna. She is therefore, like Occasio, the goddess of the “opportune moment”, favourable to both the birth of the day and the birth of children.This is illustrated, for example, in the Allegory of Birth painted by Giulio Romano in the Loggia of the secret garden of the Palazzo del Te in Mantua ca. 1531–1534. 7 On the other side of the public road, two more statues,

from Fra Sabba da Castiglione, Knight of Saint John of Jerusalem attached to the defense of Rhodes under siege from the Turks to the Marchioness of Mantua Isabella d’Este, to whom he had promised to bring back some beautiful ancient statues to adorn her new grotto. Visiting Delos, home of Apollo and Diana, he laments its ruined state. All he can send her are two medals, wrapped in a sheet of paper on which he had written a sonnet composed within the ruins of a temple, “so that at least she may be able to say that her collection boasts some antiques from the home of Apollo.”65 Finally, a fine description of the island, where the entire legend of Latona and the birth of Apollo and Diana is recounted in great detail, is Benedetto Bordone’s bestseller, Libro di Benedetto Bordone nel qual si ragiona de tutte l’isole del mondo [. . .], printed in Venice in 1528 and reprinted in 1534, 1537, and 1547 (Fig. 111).66 As we will see later, this mythical topography of the island is at the origin of the idea for the nymphaeum of Villa Barbaro.

We are not finished with the facade yet. Let us now observe how the theme of civilization versus barbarism also relates to that of hospitality. Above each of the four pedimented windows of the facade are short Latin inscriptions in elegant lettering (Fig. 112). Put together and read from top left to bottom left, then top right to bottom right, they form a sentence: “Nil tecti sub tecto / Hospes non hospes / Omnia tuta bonis / Non solum dominis,” which can be translated as “There is nothing hidden under this roof, / O guest who is not a guest [i.e., a stranger], / All is safe here for good people, / Not just for the masters.”67

This apparently simple message of hospitality is directly linked to a very important tradition in the Greco-Roman world, that of hospitality, or xenia . The practice of xenia (in Latin hospitium), the sacred rule of hospitality, implies reciprocity between a host and his guest, who are defined in Greek by the same word, xenos. This double meaning of the word is retained in the Latin hospes, used on the facade within the cryptic expression “hospes non hospes,” and in the French word hôte or Italian ospite, which means both the one who gives hospitality and the one who receives it. Xenia, implying an exchange of gifts, is central to all Greek culture and is placed under the protection of Zeus. Therefore, the statue of Jupiter in front of the villa is not only that of Zeus Gamelios, protector of marriage, but also of Zeus Xenios (the Hospitable), protector of guests and keeper of the rules of hospitality. In Renaissance villas, the display of inscriptions welcoming visitors, the so-called lex hortorum, also belongs to this ancient tradition.68

In both Greece and Rome, xenia was an overwhelmingly upper-class institution fundamental to interstate political relations. In ancient Greece, a diplomat appointed by a foreign city-state to serve in his home state was called a proxenos and his main duty was to offer assistance and hospitality to visitors from the state they represented, especially ambassadors. It is thus not surprising to see this kind of theme adorning the facade of the house of a family who gave Venice a long list of highly distinguished diplomats. As the facade was being built, Daniele had just returned from his mission in England (1548–1551), and Marc’Antonio, who had accompanied the Venetian ambassador to France as early as 1537, was about to return there as his replacement (1561–1564). Like the imperial eagle, the institution of xenia was as important for the Barbaro family as it was for the bride’s. The Giustiniani family of Venice is one of the best examples of professionalization of the function of ambassador amongst the Venetian patricians.69

Hospitality was also, on a broader level, what defined true nobility. An entire genre of literature on household management developed in sixteenth-century Italy in which the rules of hospitality are discussed. It applied especially to Church prelates, the Christian virtue of Charity being strongly bound up with those of wealth, liberality, and magnificence. This topic is also addressed in the frescoes of the Hymenaeus Room, as we will see later. The general argument, neatly captured on the facade of Villa Barbaro, is summarized for instance in Stefano Guazzo’s bestseller, La civil conversatione (1574). For Guazzo, true nobles “keep their family honored and their home open no less to foreigners than to citizens and mainly to the poor and virtuous, to whom (if they have the means) they are obliged in order to support the dignity and greatness of their past and to show themselves worthy and legitimate heirs” (“tengono honorata famiglia et casa aperta non meno ai forestieri, che ai cittadini et principalmente ai poveri e virtuosi, alche fare sono (havendo il modo) obbligati per sostentare la dignità et la grandezza de’ loro passati et per mostrarsi degni et legittimi loro successori”).70

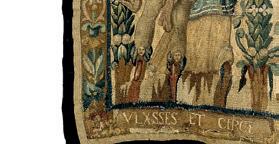

The concept of xenia is central to Homeric poetry; after homecoming it is arguably the most dominant theme of Homer’s Odyssey. The story of Latona, which is at the core of the villa’s iconography, is another good example of the importance of xenia in ancient Greek myths. Juno forbade anyone to give her hospitality, the Lycian peasants were transformed into frogs for

fig. 113

Étienne Delaune, after Luca Penni (attr.), Latona Turning the People of Lycia into Frogs, 1547–1572, engraving, 8 × 10.7 cm. London, British Museum, no. 1834,0804.200-205. Photo: ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

fig. 114

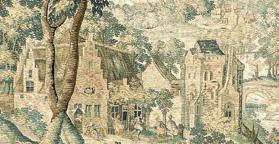

Workshop of François Spiering (Delft), The Lycian Farmers Preventing Latona and Her Children from Quenching Their Thirst, ca. 1593–ca. 1610, tapestry, silk and wool, 355 × 354 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, no. bk-1969-2. Photo: Rijksmuseum.

refusing to let her drink their water, and Apollo rewarded Delos for its hospitality to his mother (Figs. 113, 114). Hesiod, Herodotus, Thucydides, Aeschylus, Euripides, Aristophanes, Aristotle, and many others used the word frequently. The work that uses xenia most often, however over 150 times is Plato’s Laws, where a distinction is made between four types of xenos 71 Most importantly for our discussion here, xenos is a stranger, but not an enemy. Xenos is the Other, but an Other who shares the same culture and the same language: Greek. Therefore, he is to be distinguished from the barbaric, uncivilized foreigner.72

The most important sources on xenia are fundamentally connected with the theater, and especially Euripides’s Cyclops , which was published in Venice in 1503 by Aldus Manutius together with most of his extant plays.73 The play develops the concept of xenia through the retelling of the famous encounter in the Odyssey between Odysseus and Polyphemus, the one-eyed giant son of Neptune, referred to as the “guest-eater” (xenodaitumos in verse 610, and xenodaita in verse 658). Polyphemus personifies the barbarian, uncivilized, un-Greek monster that follows no laws and never cultivates the land.74 Euripides’s play is a satyr play, strongly associated with Dionysus and Dionysian religious elements. The work was written to be performed in the great theater of Dionysus, the cradle of Greek tragedy, for the Great Dionysia, the festival celebrated there each year to honor the god. The association of Dionysus with the theater is itself directly linked to xenia, or more specifically to theoxenia, hospitality given to the gods. For the early Greeks, Dionysus is himself a xenos, a traveler, who received hospitality during his ceaseless wanderings. Following an alliance with the city of Eleutherae, the Athenians were offered a statue of Dionysus, which they refused. In response to this affront, Dionysus sent a plague that affected the genitalia of all male citizens, an affliction that was cured only when the people of Athens recognized the cult of Dionysus in their city. The idol was brought into the theater so that it became itself a spectator to the theatrical performances created in his honor, such as Euripides’s satyr plays. With the cult of Dionysus, fertility was revived.75

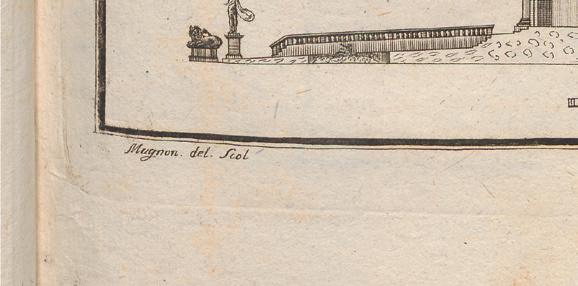

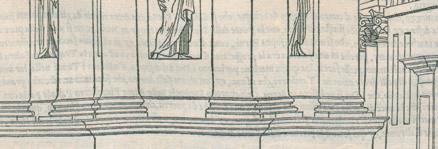

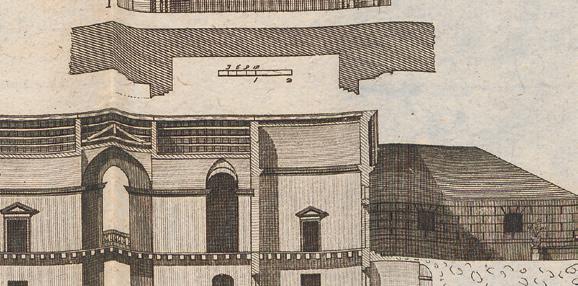

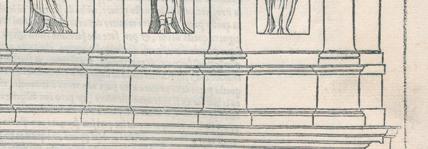

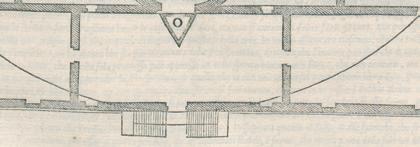

the facade appear as a logical element. Today, the facade overlooks a large, paved, square platform bordered on each side by long benches, creating a theatrical piazzetta in front of the villa (Fig. 95). The raised platform, whose entrance is guarded by two lions, is accessible via four steps from the main piazza, and another four steps lead to the entrance to the villa. As with the sundials on the facade, this entrance terrace was redesigned in the spirit of Palladio by Tomaso Buzzi in the 1930s (Fig. 115).76 Palladio does not depict it in I quattro libri , although he indicates a series of steps leading to the main central door (Fig. 33). Bertotti Scamozzi, at the end of the eighteenth century, represents it more clearly, with a balustrade that no longer exists and a circular fountain, in the center of which was a putto holding the long neck of a goose or swan, visible in early images and now in the Rose Garden (Figs. 35, 116, 117).

At Villa Barbaro, Palladio developed a truly theatrical conception of architecture in which the welcoming inscriptions on

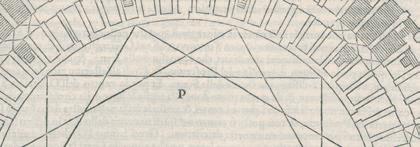

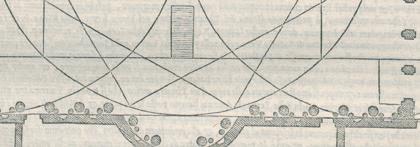

Even without this platform, Palladio’s plan for the entrance piazza in I quattro libri is, like the nymphaeum, clearly inspired by the theater, more precisely by the ancient theater. The platform recalls the Hellenistic skene or Roman scaena, and the facade of the villa functions thus as a true scaenae frons while the great hemicycle at the end of the allée that approaches the villa indubitably evokes the orchestra of the ancient theater (see Fig. 33). The comparison of this spatial composition with that of the ancient theater can even be extended to the wings of the villa flanking the projecting central block: two long rusticated porticoes articulated with rectangular Tuscan Doric piers

fig. 116

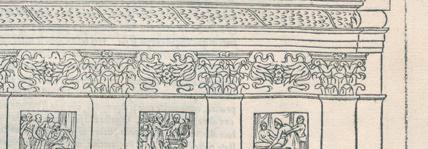

Antonio Mugnon, Spaccato: Palagio in Maser nel Trivigiano, della N.D. Basadonna Manin, in Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi, Le fabbriche e i disegni di Andrea Palladio raccolti e illustrati da Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi (Vicenza: Giovanni Rossi, 1796), bk. 3, pl. 22.

Photo: eth-Bibliothek Zürich, Rar 2018. fig. 117

Putto Holding the Neck of a Goose or Swan, ca. 1558–1560 (?), sandstone, Rose Garden, Villa Barbaro, Maser (formerly in the middle of the circular fountain in front of the villa). Photo: author by permission Villa di Maser—Patrimonio dell’Umanità—unesco

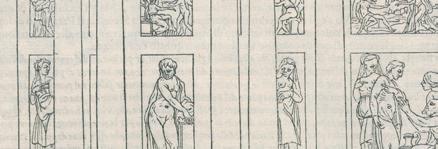

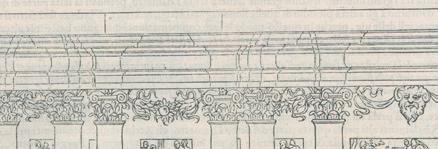

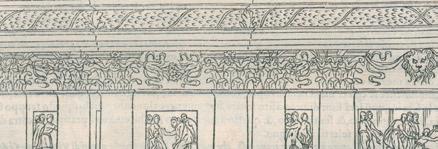

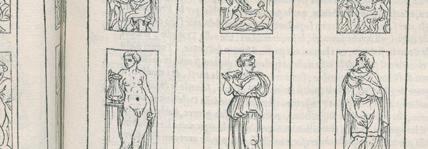

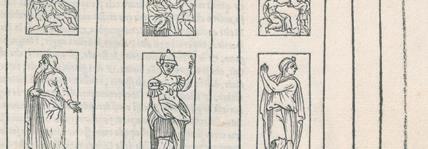

and ornamented with stucco masks serving as keystones, and statues of divinities in rectangular niches (Figs. 6, 30, 95, 119). These elements are present in the ancient theatre too, as Inge Reist noted in her 1985 dissertation:

Situated in the eight piers of the colombara, the other freestanding statues of the southern facade, most likely by Marcantonio Barbaro, can be identified (from left to right) as Venus, Bacchus, Ceres, and Apollo (within the niches of the southwestern colombara) and as Flora, Charon, Mercury [with the head of Argus], and Diana on the southeastern side. [. . .] [T]hese statues serve collectively as an allusion to their counterparts in the scaenae frons of ancient theaters and individually as a prelude to the iconographic schema, themselves replete with figures of Olympian and sylvan gods, of the interior frescoes and nymphaeum sculptures behind.77

The masks above the arches of the wings’ porticoes are visually and typologically connected with the satyr mask above the arched entrance door (see Figs. 95, 96). With their curiously old-fashioned headdresses and headgear (except for two other satyr masks at the extremity of the western wing), they evoke portraits rather than idealized figures. Although they appear as a typical element of the ornamental vocabulary of the classical theatre, I suggest they represent members, past or present, real or ideal, of the Barbaro family, assembled in a theatrical chorus on the stage of the family villa.78 All the grotesque human or

fig. 118

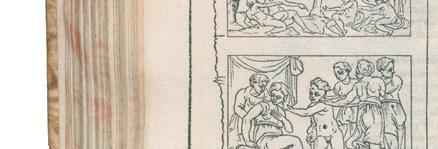

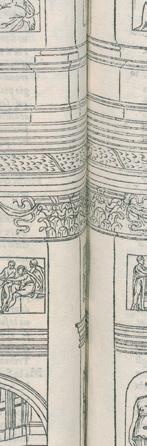

Andrea Palladio, Frons scaenae, in Daniele Barbaro, I dieci libri dell’architettura di M. Vitruvio tradutti et commentati da Monsignor Barbaro eletto patriarca d’Aquileggia (Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1556), 156. Photo: eth Bibliothek, Zürich, 160.

fig. 120

Andrea Palladio, The Greek Theater, in Barbaro, I dieci libri, 168. Photo: eth Bibliothek, Zürich, 163.

fig. 119

Western portico, ca. 1557–1558, Villa Barbaro, Maser

Photo: author by permission Villa di Maser—Patrimonio dell’Umanità—unesco

fig. 120

Andrea Palladio, The Greek Theater, in Barbaro, I dieci libri, 168. Photo: eth Bibliothek, Zürich, 163.

fig. 119

Western portico, ca. 1557–1558, Villa Barbaro, Maser

Photo: author by permission Villa di Maser—Patrimonio dell’Umanità—unesco

Through a careful description of its architecture, paintings and sculptures, this book offers the first comprehensive analysis of the Villa Barbaro at Maser, one of the most famous masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance. Conceived and commissioned by Daniele Barbaro, a leading humanist of the Venetian Renaissance, and his brother Marc’Antonio, an important politician of the Republic of Venice and a talented amateur artist, the villa’s architecture and painted decoration were created by two canonical figures of Renaissance art: the architect Andrea Palladio and the painter Paolo Veronese. By offering a new and holistic reading of the iconographic program of Villa Barbaro, the study highlights in particular the importance of women, childbirth and motherhood. With a strong multidisciplinary approach, the book is also a contribution to the history of astronomy, philosophy and domesticity in sixteenth-century Venice.

denis ribouillault is professor of early modern art history at the University of Montreal. His research focuses on Renaissance villa culture, cultural landscape and garden studies and the intersection between art, science, and literature in the early modern period. He is the recipient of numerous grants including a French Academy in Rome Fellowship, Florence J. Gould Fellowship at Villa I Tatti, and a Dumbarton Oaks Fellowship.

The Villa Barbaro at Maser

The Villa Barbaro at Maser