The House of Windsor

Matthias Range

© 2024, Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Matthias Range asserts his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publishers have no control over, or responsibility for, any third-party website referred to in this book. All internet addresses given in the this book were correct at the time of going to press. The authors and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

ISBN 978-2-503-59697-6

D/2024/0095/76

Designed and typeset in Bembo by Julia Craig-McFeely, Oxford OX4 4BS

Printed in the EU on acid-free paper.

Cover illustration: ‘Royal Wedding. HRH Princess Elizabeth and Duke of Edinburgh. The bridal couple with bridesmaids. 20 November 1947, colourized image by TopFoto production 03 05 2017’ © TopFoto 1414414.

Contents

Illustrations ii

Figures v

Preface vii

Acknowledgements viii

Abbreviations and Conventions x

1 Venue, Ceremonial, and Music: The Weddings of the Windsors 1

2 The ‘Abbey Weddings’: 1919 and the 1920s 19

3 The ‘Jubilee’ Weddings: The 1930s 53

4 ‘A Flash of Colour’: The Wedding of the Future Queen, 1947 77

5 The Fanfare Weddings: The Early 1960s 115

6 The Heyday of Royal Weddings: The 1970s and 1980s 163

7‘The New Era of Royal Weddings’: Tradition and Innovation in the New Millennium 209

8 Change and Continuity: Some Wider Aspects of Royal Weddings 241

Appendices

A Chronological List of British Royal Weddings since 1919

B Texts and Transcriptions

C Royal Weddings and their Music

Processions

Beginning with the royal weddings in 1919, the outdoor processions to and from the wedding venue have seen a considerable rise in significance. In the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there had been distinct, elaborate processions on foot to the chapel – but these were more or less restricted to the upper echelons of society who either took part in them or were privileged enough to obtain permission to see them. Beginning with the wedding of Queen Victoria in 1840, some weddings had also been preceded by short carriage processions to the wedding venue. However, even though these were significant innovations and attended by large numbers of spectators, these short carriage processions were overall not (yet) very significant parts of the proceedings.

The elaborate processions on foot to royal weddings did not survive into the twentieth century. Since royal weddings moved to Westminster Abbey in 1919, there was no need, nor any practicable possibility for these: instead, the carriage processions that had already been part of the nineteenth century weddings at Windsor have become a much more prominent part of the proceedings, bringing the main participants and guests directly to the Abbey and then back

— Venue, Ceremonial and Music

to the Castle or Palace after the ceremony. Even though these processions have fewer participants than the former processions on foot, they nevertheless have a somewhat greater impact. With their much longer route to Westminster Abbey and back – since the 1980s regularly using an open landau carriage for the bridal couple, so that they can be more easily seen – these processions allow for a much wider participation of the general public as spectators. The carriage processions have become a new tradition, an essential and expected element of these events, and their appearance has changed very little over the last few decades, their ceremonial accoutrements, with horse-drawn carriages and ceremonial uniforms, essentially remaining the same (see Illustrations 1.4 and 1.5).

Conversely, at modern royal weddings at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, there are now distinct walking processions of the more distinguished guests and participants down from the Castle to the Chapel. In the nineteenth century these had been carriage processions, but there is now, at best, a carriage procession of the couple alone after the ceremony.The bride, however, does not walk in these processions; she usually arrives by car.

In contrast to the elaborate processions on foot of the past, however, the outdoor processions on foot to the Chapel at modern royal weddings are much less ceremonial. In fact, they do not very much appear like processions. Whereas the processions on foot in previous centuries were headed by heralds and accompanied by music, with the musicians themselves walking as part of the processional retinue, the modern processions on foot feature neither heralds nor music. The longer carriage processions, however, do have some music, played by bands placed along the route. In particular, these play the National Anthem, as a royal salute (Illustration 1.6 overleaf ).

Only since 1840 has the bride been the last to enter the venue of the wedding ceremony: previously the monarch had been the last to arrive, but in 1840 Queen Victoria was both bride

British Royal Weddings

Carriage procession after the wedding

the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, 2011, at Horse Guards. The band seen in the foreground is just playing the National Anthem, with the Duke of Cambridge saluting and the Duchess bowing her head. Alamy 2CNPM29.

and monarch.17 Since then, the bride has been the last to enter at every royal wedding and her entrance was soon understood as one of the high points of the proceedings. By 1923, this perception was firmly established: an account of the wedding of Prince Albert and Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in that year enthusiastically described the entrance of the bride as ‘the climax, the beautiful climax’ of the proceedings up to that point.18

Whereas the entrance of the bride gained ever more attention and ceremonial gravitas, that of the bridegroom became ever less distinct. Towards the twentieth century, the bridegroom’s entrance procession had much decreased in elaboration, and by the time royal weddings moved to the grander venue of Westminster Abbey, in 1919, it was barely noticeable. For the royal wedding in that year, the bridegroom Sir Alexander Ramsay, a Royal Navy officer, appeared widely unnoticed. As the Times pointed out:

At some moment not observed by most of those present the bridegroom had, with the modesty characteristic of a sailor, come through the South Transept and […] taken his place at the end of the front bench on the south side below the Sacrarium rail.19

At the next royal wedding, that of Princess Mary in 1922, the accounts similarly noted drily that the bridegroom, Henry Viscount Lascelles ‘steals quietly in through the Poets’ Corner

17 See Range, BRW, p. 121.

18 ‘The Wedding of H.R.H. The Duke of York and The Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon April 26, 1923’, Supplement to The Queen, 26 April 1923, p. [iii].

19 ‘Royal Wedding’, Times, 28 February 1919, pp. 10 and 14, here p. 14.

be seen in the film footage and pictures of the ceremony, standing on either side of the grave as the bridal pair walks past them (Illustration 4.7).

When Roper wrote to McKie in early October to congratulate him on his approved music proposal, he told him that we are already prepared and await only the Introit.With this I am very pleased – it has personality and exactly fits its purpose. I had warned Alan Frank [at Oxford University Press] about it to save time and there is just nice time for us all to prepare it if we get it by 1 Novr.178

This ‘Introit’ must refer to McKie’s We Wait for thy Loving Kindness.This was published by Oxford University Press, in a series edited by Roper.179 The subtitle of this publication intriguingly called it ‘Antiphon’, perhaps accounting for Roper’s referring to it as ‘the Introit’, or short piece to introduce something – although neither term seems to describe McKie’s piece very well. It is noteworthy that, the score was published before the wedding, as some special wedding music had been in earlier years.

In the same note Roper also referred to ‘the question of the last item which could be settled at final choir rehearsal’ and for which he offered to ‘find Copies of our use at the CR.’ Roper had earlier referred to the Wesley anthem and to psalters, hymn books and the responses; therefore, the ‘last item’ most plausibly refers to the National Anthem, which was the ‘last item’ in so far as it concluded the service proper. If so, it seems curious that Westminster Abbey did not have its own copies of the National Anthem, which must have been sung at the Abbey quite regularly – for instance, at the Royal Maundy services.

178 Roper to McKie, 7 October 1947 (as in fn. 63, and transcr. in Appendix B 4.1).

179 William McKie, We Wait for thy Loving Kindness, O God: An Antiphon for Tenor Solo, Chorus, and Organ, ‘The Oxford Series of Modern Anthems’, ed. by E. Stanley Roper (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1947).

Illustration 4.7: The Royal Wedding, 1947 [the procession leaving the Abbey], showing the scholars of Westminster wearing surplices, standing among the congregation. Gelatin silver print, The Royal Collection RCIN 2002397, Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2022.

British Royal Weddings

Performance and Rehearsals

Thanks to McKie’s meticulous records, many details of the actual performance of the music at the wedding are well documented. In his early August proposal, McKie referred to the precedent of the 1934 wedding, where the singers had come from Westminster Abbey, the Chapel Royal and St George’s Chapel, with a processional choir that had ‘consisted of 6 Children of CR, 6 choristers of WA, 6 Lay Vicars’.180 In a letter to the Dean of Windsor, Dean Don explained that in 1934 ‘St. George’s Chapel Windsor was represented by four choristers, who took part in the service’.181 He continued that, after discussion with the Precentor and the organist, ‘we are agreed that it would be very appropriate and helpful if you would send a contingent of, say, six choristers to supplement our choir’. The inclusion of choristers from Windsor was given an added layer of significance. John Henderson and Trevor Jarvis have observed that it ‘was reported in the newspapers as being a tribute to Harris [the Windsor organist], who had taught music to the Princess’.182 According to the printed ceremonial, the processional choir was to consist of ‘6 children of the Chapel Royal, 6 Abbey choristers, 6 Lay Vicars’.183 While this matched the 1934 arrangement, McKie suggested that the processional choir could furthermore also include the six choristers from St George’s, and then twelve (not six) lay vicars, all from Westminster Abbey.184

An article on the preparations of the wedding in one of the illustrated magazines included a colour picture of William McKie sitting at the Abbey organ, accompanying the singing of the Abbey choristers.The boys are singing from green hymn books, possibly The English Hymnal, and the bright scarlet of their cassocks is another component adding to the ‘flash of colour’ observation at this wedding – spread widely through colour pictures like this in the popular magazines of the day (Illustration 4.8).

The fourteen choristers in this preview picture are just a small part of the choir for the wedding, which included a much larger number of singers. As the picture caption explains, these ‘Royal Wedding Choristers’ are in the organ loft ‘waiting to be joined by fellow choristers from the Chapel Royal, St. James’s, and from Windsor Castle.’ McKie’s list with the ‘MEMBERSO [sic] OF The ROYAL WEDDING CHOIR who took part in the News Reel Filming of Choir Rehearsal’ includes all the singers’ names: in addition to himself and Peasgood, the Abbey’s sub-organist, there were eleven gentlemen from Westminster Abbey plus ‘(Mr E. Saunders)’, ‘Five’ unnamed ones from the Chapel Royal and ten ‘Supernumerary Singers’ – then 28 ‘Boys from the Choir School’, ‘9 “Sunday Boys”’, ‘6 Choristers from Windsor’, and ‘10 Children of H. M. Chapel Royal’. This makes a total of 27 men and 53 boys, 80 singers altogether.185 McKie referred to the ‘Supernumerary Singers’ also in another interesting note: It seems that there will be room for a few extra singers in the Choir for the Royal Wedding on 20th November, and I have been given permission to invite the gentlemen who helped in the Abbey Choir during the war period to join us for this occasion as supernumerary singers.186

180 McKie to Precentor, 3 August 1947, Lwa McKie 1947, bundle 1, p. 1.

181 Don to the Dean of Windsor, 7 August 1947, Lwa WAM 62243

182 John Henderson and Trevor Jarvis, Sir William Henry Harris: Organist, Choir Trainer and Composer (Salisbury: The Royal School of Church Music, 2018), p. 57.

183 Ceremonial 1947, p. 4.

184 McKie to Precentor, 3 August 1947, Lwa McKie 1947, bundle 1, p. 2.

185 The list is included in Lwa WAM OC/2/5, folder ‘ACCOUNTS’. See also the appended note from McKie to Hebron, 25 November 1947: ‘I was wrong – there were 27 men in the Choir at the Wedding. So you are one fee to the good!’

186 McKie to [unknown recipient], 7 November 1947 (in two copies), in Lwa McKie 1947, bundle 1, separate bundle of papers.

4 — ‘A

Flash of Colour’

Illustration 4.8: William McKie at the Westminster Abbey organ with some of the choristers. Picture in Joan Skipsey, ‘Prelude to the Wedding’, Illustrated, 22 November 1947, pp. 7–13, here p.7. Author’s collection.

McKie’s note is followed by eight replies from men accepting the invitation. In addition, nine more boys were invited to join the choir for the wedding: these were mostly from other London choirs, but it is not known what the criteria for their selection had been.187 The inclusion of so many external singers was a clear sign that this event was more than a mere Abbey affair, and rather an occasion of much broader scope. McKie’s papers do not seem to include a final list of the choir that sang at the service, but in his article on the music he stated that there had been ‘91 singers altogether’, comprising:

(i) the Abbey Choir, and all the available junior boys from the Choir School;

(ii) the Gentlemen and Children of H.M. Chapels Royal;

(iii) six choristers of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor;

(iv) a few additional tenors and basses, to balance the large number of boys.188

Then, in another source, McKie noted a total number of 96 for the organ loft, and also included two drawings showing their positions (Illustration 4.9 overleaf ).189

Regarding the actual performance at the service, McKie also suggested that he should like to go with the Processional Choir, to take over the Organ as soon as we reach the Organ Loft; to do any necessary conducting at the service, and to take charge of the choir at rehearsals beforehand.190

187 For the invitations see Lwa McKie 1947, bundle 2.

188 McKie, ‘Royal Wedding’ (1948), p. 80.

189 See Lwa McKie 1947, bundle 1.

190 This and the following McKie to Precentor, 3 August 1947, Lwa McKie 1947, bundle 1, p. 2.

6 — The Heyday of Royal Weddings

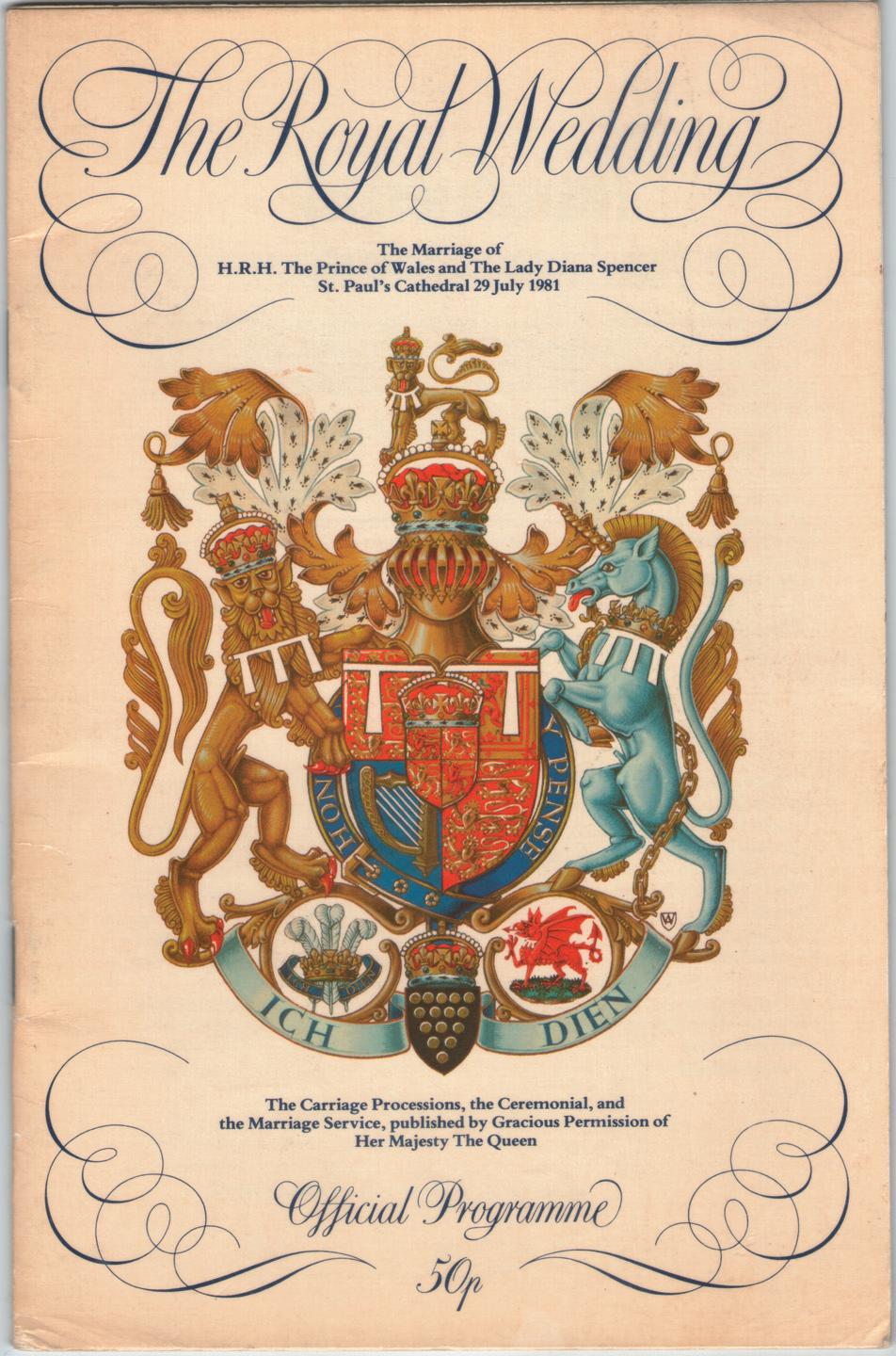

Wales – in 1736 and 1863, respectively.75 Furthermore, on the occasion of Princess Mary’ wedding at Westminster Abbey in 1922, one writer had predicted that it was ‘quite possible’ that her brother the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) ‘will be married in the nation’s Cathedral, St. Paul’s’.76 This also mentioned that ‘the music will probably have by then greatly improved’, more or less insinuating that the low standard of the music had been the reason why the 1922 wedding was not at St Paul’s. However, nothing had ever come of these speculations – until 1981.

One of the main reasons for the change of venue was the larger size of St Paul’s. When the choice was officially announced in early March, a statement by Robert Runcie, the Archbishop of Canterbury who married the couple, explained that thanks to the bigger venue ‘large numbers of friends and representatives from every walk of life in Britain and the Commonwealth’ would be able to attend the ceremony.77 Robin Young in the Times explained that St Paul’s was chosen ‘because it can seat several hundred more guests’ than Westminster Abbey.78 At the same time he detailed:

About 10,000 people crowded into St Paul’s for the thanksgiving service at the end of the Second World War. Allowing for modern safety requirements and security arrangements it is hoped that up to 3,000 might be able to attend the royal wedding.

In the end, this wedding was, as Alan Hamilton put it, ‘the most public of all private moments, watched by 3,500 guests inside Wren’s light and majestic cathedral’.79

Besides the possibility of a larger congregation, it has been suggested that it was the music of the ceremony that played an important part in the choice of venue. A few years after the event, on the occasion of the next royal wedding, H. A. Milton explained that Prince Charles had ‘judged’ that St Paul’s ‘post-Renaissance airiness compared with the sepulchral Gothic of the Abbey was a better setting for his chosen programme of music.’80

In the same vein, but from a more practical angle, it has been highlighted that the choice of St Paul’s also meant more space for all the musicians that the Prince of Wales wanted to participate.81 Judged by the sheer number of musicians, this wedding was grander than any previous one. Alastair Burnet aptly summarized that Prince Charles ‘wanted a musical wedding, and St Paul’s filled the bill’.82

Apart from space, there was another practical point in favour of St Paul’s: Burnet explained that this choice also meant a longer route for the outdoor processions.83 In addition, there were longer processions inside, necessitated by the size of the building and the different stages of the ceremony: the exchange of the vows took place at the steps of the quire, under the great dome, on a dais that was just big enough for the couple and the two families, covered with rich red carpet, increasing the sumptuousness of the scene (Illustrations 6.5 and 6.6 overleaf ). Then, for their blessing, the couple moved to the high altar, at the end of the quire; and the signing of the register took place in the south quire aisle, known as the Dean’s Aisle, (see Illustrations 6.8, p. 190 and 8.4, p. 256).

75 See Matthias Range, British Royal Weddings: From the Stuarts to the Early Nineteenth Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2022) [hereinafter ‘Range, BRW ’], pp. 61 and 163.

76 ‘A. E. L.’, ‘The World of Women’, ILN, 18 February 1922, p. 230.

77 Archbishop’s statement, 3 March 1981, Llp Runcie/STATEMENT/2, fol. 12r

78 Robin Young, ‘St Paul’s Chosen for July Royal Wedding, Times, 4 March 1981, p. 1.

79 Alan Hamilton, ‘Day of Romance in a Grey World’, Times, 30 July 1981, p. 1.

80 H. A. Milton, ‘The Abbey Tradition’, ‘Royal Year 1986’, special issue of ILN, 4 August 1986, pp. 96–97, here p. 96.

81 Ingrid B. Seward, My Husband and I: The Inside Story of 70 Years of the Royal Marriage (Simon and Schuster, 2017), p. 166.

82 Alastair Burnet, The ITN Book of the Royal Wedding (London: Michael O’Mara Books Limited and Independent Television News Limited, 1986), p. 105.

83 Burnet, ITN Book of the Royal Wedding, p. 92. See also Brand, Royal Weddings, pp. 49–50.

British Royal Weddings

Trevor Beeson, a canon of Westminster Abbey, was somewhat disappointed by the preference for St Paul’s and recorded some interesting details on the choice of venue. He noted that Edward Adeane, the private secretary of the Prince of Wales, had called the Dean of Westminster before the official announcement:

He explained that the Prince has nothing against the Abbey but prefers St Paul’s and believes that its vast space, with an unrestricted view, will be more suitable for the large number of guests who are to be invited. He had been much impressed by the Service of Thanksgiving for the Queen Mother’s eightieth birthday held there.84

In relation to the ‘unrestricted view’, however, Beeson commented critically that St Paul’s will certainly accommodate more guests, but it is an illusion that they will see more than they would in the Abbey, since the great distance between the chief participants and the majority of the congregation will restrict visibility to the processions to and from the West door.85

84 Trevor Beeson, Window on Westminster: A Canon’s Diary, 1976–1987 (London: SCM Press Ltd., 1998), p. 132: entry for Monday, 23 February 1981.

85 Beeson, Window on Westminster, p. 134.

British Royal Weddings

At the previous Abbey wedding, that of Princess Margaret in 1960, the Queen Mother also had had a faldstool. In 1963, however, nobody else in the sacrarium apart from the Queen had a faldstool, and the others sitting in this area, on their chairs, mostly can be seen with their heads bowed. This image may give the impression that the Queen is kneeling representatively for the whole assembly, joining the bridal couple in the name of all the congregation. The picture was more widely disseminated through inclusion in the reports of the wedding, thus supporting the image of a pious monarchy.76

However, by the time of the next more elaborate royal wedding, that of Princess Anne in 1973, the bridal couple were clearly the only ones in the sacrarium who could be seen kneeling (Illustrations 8.3 and 6.3, p. 173). The Queen, let alone any other member of the royal family, was no longer provided with a faldstool, thus also removing this visual marker of public piety.

Kneeling at royal services since the 1960s has generally been seen less and less, in parallel with its overall decline at Anglican

church services, and it is very rarely seen today. The most notable instance was probably Charles III’s kneeling for the oath at his coronation in May 2023. For royal weddings, in particular, kneeling has disappeared not merely for the congregation, including the family, but also for the choir and even the clergy. It is now only the couple themselves who can be seen kneeling and who are pictured in this pious act (see Illustration 7.10, p. 237).

Overall, this change has at least visually altered the character of the prayers. The emphasis has somewhat shifted from the prayers being communal prayers – offered by the whole of the congregation for the couple – to their being an act of prayer by the bridal couple alone, leading into, if not merging with, the following blessing of the couple.

76 It was reproduced on the cover of Country Life’s Royal Wedding Supplement, 2 May 1963, and also, for instance, in The Sphere, 4 May 1963, pp. 166–67.

8 — Change and Continuity

Multi-confessionalism

In the context of the religious core of weddings, it is interesting to look at another ceremonial aspect of the wedding service. All major British royal weddings since the Reformation have been Anglican, which was codified by the legal requirements of the 1701 Act of Settlement. In relation to the 2011 wedding, Norman Bonney, explained:

While Scotland has its own established church and there are no established churches in Northern Ireland and Wales, nonetheless, in many of its significant national ceremonials, rituals and actions – most significantly the coronation, but also royal weddings as in 2011 – the Church of England acts on behalf of the whole of the United Kingdom.77

Notwithstanding the Anglican nature of the British monarchy, the twentieth century to some extent added the aspect of multi-confessionalism to royal weddings. As early as on the occasion of the 1922 wedding, there was a religiously more inclusive approach, when invitations to the wedding had been sent to ‘all the greater denominations of the clergy throughout England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland’.78 There were also representatives of the Episcopal Church of Scotland – the Scottish Anglican equivalent – at the 1923 and 1935 weddings. Yet, this would have been mere attendance, these representatives not having any role in the service. During the preparations for the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten, in 1947, the Dean of Westminster asked the Archbishop of Canterbury what he ought to do if other spiritual leaders asked him for participation in the service, such as the Moderator of the Church of Scotland and/or the Moderator of the Free Church Federal Council; and he recalled that they had claimed some participation at the 1937 coronation.79 The archbishop replied decidedly:

I take it that neither of the Moderators has ever taken any part in a Royal Wedding. If they raise the question, I think the answer should be that it is not wise to depart from precedent in this matter.80

Regarding active participation, Anglican exclusivity at British state services was prominently broken at the Queen’s coronation in 1953, when the Moderator of the Church of Scotland presented her with the Bible.81 Wolffe has highlighted that there was ecumenical participation at the state thanksgiving service for the Queen Mother’s 80th birthday at St Paul’s Cathedral in 1980.82 Already three years previously, in 1977, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Donald Coggan, had recorded:

I had a talk with the Dean of Westminster and with Reg Pullen about non-Anglican participation in the wedding of the Prince of Wales if at any time this should occur. It would presumably be at the Abbey. / The three of us agreed that it would be desirable that such participation should in these days take place – it has not done so before. We further agreed that the shape of the Marriage Service is such that this should not prove very difficult to bring about, though the actual marriage would, of course, be taken by the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Archbishop of York should have a part. / We decided to keep a memorandum of our conversation on our files in view of the possibility that others might be in office when this event took place.83

77 Norman Bonney, ‘The Sacred Kingdom and the Royal Wedding of 2011’, The Political Quarterly, 82:4 (October–December 2011), pp. 636–44, here pp. 636–37.

78 ‘Royal Wedding Guests’, Times, 13 February 1922, p. 7.

79 Alan Campbell Don to Archbishop Fischer, 1 August 1947, Lwa WAM 64420

80 Fisher to Don, 2 August 1947, Lwa WAM 62242

81 See Matthias Range, Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations: from James I to Elizabeth II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 249.

82 John Wolffe, ‘National Occasions at St Paul’s since 1800’, in St. Paul’s: The Cathedral Church of London 604-2004, ed. by Derek Keene, Arthur Burns, and Andrew Saint (New Haven:Yale University Press, 2004), pp. 381–91, here p. 390.

83 ‘Prince of Wales / plans for wedding’, ‘MEMORANDUM’, 6 October 1977, Llp Coggan 57, fol. 163r

This memorandum provides no concrete reason why there should be non-Anglican participation: when both the bride and bridegroom are Anglican, it does – strictly speaking – not make much sense to have clerics from another denomination to have a part at their wedding. Yet, Coggan’s reference to ‘in these days’ alludes to the changed composition and attitudes of society. This in turn illustrates that, although royal weddings may technically be private royal occasions, they are at the same time a kind of unofficial state occasion thought to represent not only the whole of the monarchy but also a broader image of the nation.

For royal weddings, an ecumenical aspect was indeed added for the wedding of the Prince of Wales, which did, however, not occur until four years after Archbishop Coggan’s memorandum, in 1981. Kathryn Spink then pointed out that ‘The presence and participation of representatives of a number of Churches will make it a more ecumenical service than any pre-