THE FATE OF EARLY ITALIAN ART

DURING WORLD WAR II

PROTECTION, RESCUE, RESTORATION

CATHLEEN HOENIGER

CATHLEEN HOENIGER

Vol.V

Holly Flora

Sarah S. Wilkins

Cathleen Hoeniger

Queen’s University, Canada with Geoffrey Hodgetts

Queen’s University, Canada

Chapter 1. Introduction 17

Chapter 2. Historical Background: Italy’s Experience of World War II G eoffrey HodG etts ............................. 33

Chapter 3. The Role of the Italian Federal Government in the Protection of Monuments from War Damage 77

Chapter 4. The Defence of Art in the Italian Provinces before and during World War II .......................... 115

Chapter 5. The First Responses to the War Damage of Early Italian Art, 1943-1945 167

Chapter 6. What Befell the Mazzatosta Chapel in Viterbo and the Wider Circumstances in Lazio Province during World War II 2 33

Chapter 7. The Wall Paintings of Pisa’s Camposanto Monumentale in the Context of World War II ............ 291

Chapter 8. Conclusion 369 Bibliography 383 Index 415

This approach did not require a precise bombsight technology. Counter to this, during the 1930s, American Air Force planners were seeking the most precise ways of striking individual targets from a safer, higher altitude. This philosophy was driven by some uniquely American factors, including the wish to demonstrate advanced, made-in-America technology. The probably unrealistic challenge they set themselves was to develop better aircraft to fly at high altitudes for crew safety, at faster speeds in daylight conditions when visibility was better, equipped with a bombsight that provided precise capability to the bombardier to locate a militarily important target and consistently deliver an accurate strike with minimal collateral damage.124

After eleven years of development under top secret conditions, the first Norden bombsight was delivered to the Army Air Corps in April 1933.125 Refined continuously until war was declared in 1941, ninety thousand models were produced during the war, and fifty thousand men were trained in their use. By the war’s end, approximately US$1.5 billion had been spent on the project, its introduction being second only to the development of the atomic bomb in both cost and secrecy.126

While the technology of the Norden bombsight was being refined, methods of using aerial photography were being developed which would become essential in later years for identifying and avoiding marked heritage monuments on aerial photographs, as well as assessing damage after an attack (Fig. 2.4).127 During these years, work was also being done on the mathematics of measuring errors in accuracy using the concept of Circular Error Probable (CEP). This concept, while highly technical and, on the surface, perhaps superfluous to this art historical study, is important when trying to explain the damage that was done to Italian monuments that were marked as protected. In later chapters, the fact that Allied bombs destroyed Italian heritage sites that were clearly signalled as protected, will be discussed. Their locations were marked on maps provided to air crews, and standardized, large warning signs were painted on their roofs. This signage was required under Regulation Article 27 of both the Hague Convention II of 1899 and Convention IV of 1907. The rules were expanded upon and more clearly defined under Article 25 of the 1923 Hague Draft Rules for Air Warfare, which as noted, were never binding.128 It may also help us to

understand what would otherwise seem to be the completely random or even deliberate destruction of neighborhoods with their valued and vulnerable structures. The CEP is a measure of any weapon system’s precision, in this case aerial bombing. It is defined as the radius of a circle whose boundary is expected to include fifty percent of the bombs dropped. For example, if a bombing system has a CEP of 100 m, when one hundred bombs are dropped on a single target, fifty will fall within a circle with a radius of 100 m around the average point of impact, which, of course, might not even be the actual target.The other fifty bombs would fall outside this circle and strike any object outside the target zone.129

Daylight bombing from higher altitudes was a policy strongly adhered to by the Americans throughout the war, despite disagreements with the British. For them, the official Royal Air Force (RAF) doctrine of 1928 remained in force, stating that it was legitimate to break down the enemy’s means of resistance by attacking any target that would achieve this goal.130 Even though strong evidence pointed against this doctrine, in February 1942, the British Defence Committee issued the Area Bombing Directive, ordering the bombing of cities rather than specific strategic targets, stating that this would just as effectively damage wartime production, even if by more indirect means.131 In the case of Italy, area bombing was a calculated approach by Churchill and others in command to force Italy out of the war. The German air force also relied on area bombing in Britain during the Blitz of 1940-1941, targeting industries and portside infrastructure, yet causing widespread destruction of more than a dozen large cities in England and Wales.132

Despite the technological advances in aircraft design and speed and the theoretical sophistication of the Norden bombsight, from training flights in the United States under ideal weather conditions and not facing any enemy anti-aircraft measures, prewar results were not impressive. A heavy bomber such as the B-17 flying at 20,000 ft had a 1.2 percent probability of hitting a 100-ft x 100-ft target with an expected CEP of 555 ft. In other words, it would require two hundred twenty aircraft to achieve a ninety percent probability of destroying such a target. To achieve results, large formations of bombers dropping their bombs simultaneously would be required—which would hardly be possible. The standard use of smaller box-formations of aircraft releasing bombs in salvoes often caused quite large errors at ground level. Even small differences among the formation’s individual planes’ heading or air speed affected accuracy. A variation in just six miles per hour in a plane’s air speed could cause an error of 700 ft at the target, more than enough to destroy adjacent structures without striking the target.133 If one recalls the location of important monuments, such as San Francesco and Santa Maria della Verità in Viterbo, and their proximity to a target like the highway or railway yards, then this potential for error becomes highly significant (Fig. 2.5).

After America entered the war and joined the Mediterranean Theatre of Operations in November 1942, the challenge to precision bombing could be examined under combat conditions. A report of 11 December 1943 told a sobering story—a story that had devastating results for Italian heritage. A bombing campaign in support of the ground battles against

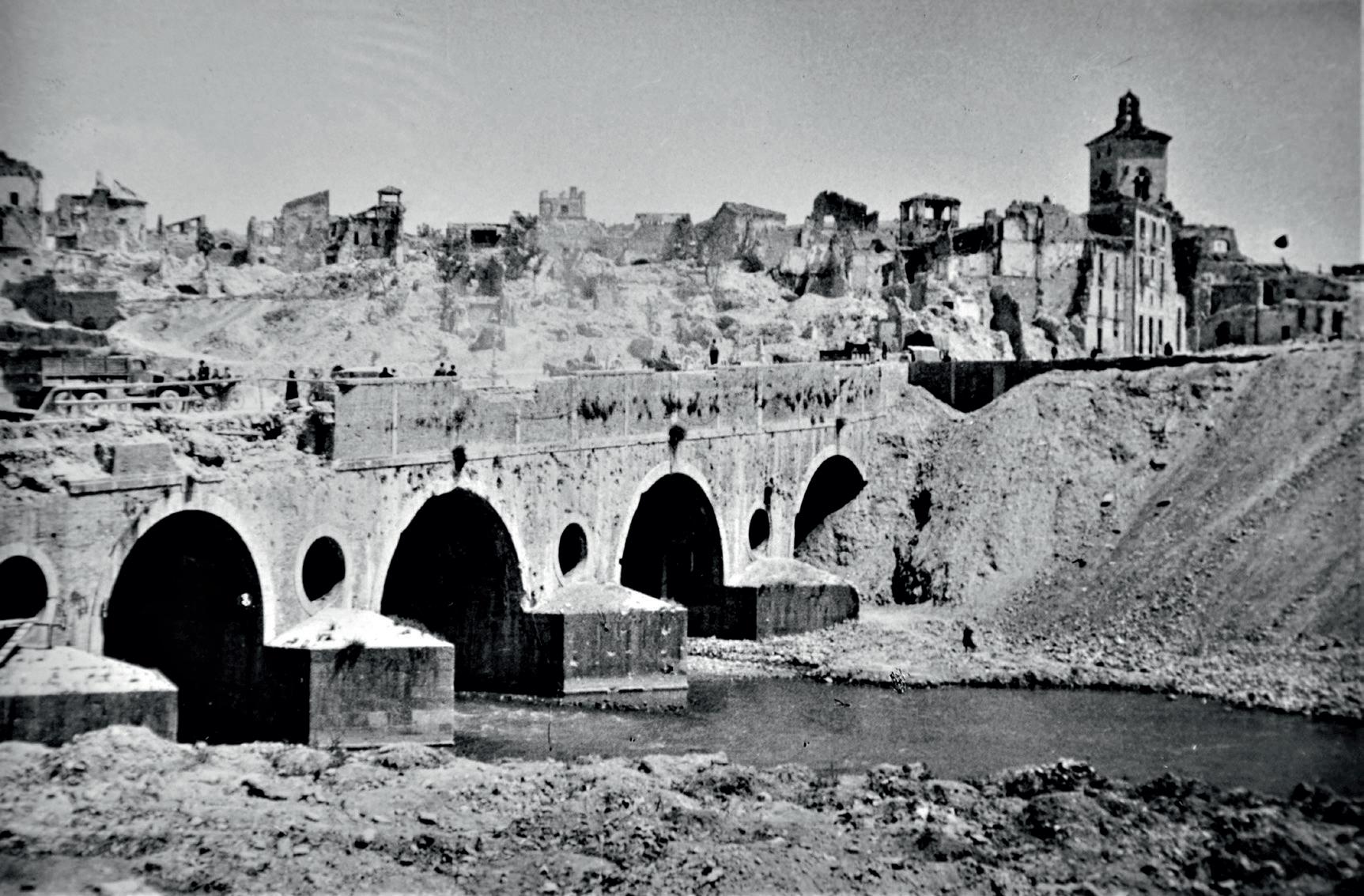

German forces following the Allied landings at Salerno had been mounted between August and November 1943 to destroy forty-seven rail and highway bridges in southern Italy. These bridges were essential as supply and retreat routes for the occupying German divisions, and destroying them would force the Germans to retreat northwards. The report found that only thirteen of the forty-seven bridges were significantly damaged.134 For example, in the raid of 16 September 1943, the target was the Vanvitelli bridge over the Calore River in the city

the ministry and the superintendents.71 In particular, the strong Irpinia earthquake of 23-24 July 1930 caused extensive damage to the Vulture region of Basilicata. In the aftermath, the ministry supported repairs and restorations to historic architecture, notably to heavily damaged Norman churches in the towns of Melfi, Rapolla, and Venosa.72 Only a few months after the Irpinia disaster, a strong earthquake caused widespread destruction in the Marche on 30 October 1930. Towns along the Adriatic, including Ancona and Fano, were affected, but the epicentre was close to the bustling port of Senigallia, resulting in the loss of many buildings in the town centre, among them attractive sixteenth- and seventeenth-century palaces and churches.73

Aside from supporting urgent repairs to monuments that had been damaged in World War I or in natural disasters, most of the financial outlay from Rome to the provinces in the interwar period was for conservation to art and architecture that had been subject to gradual and progressive deterioration. In fact, after 1918, the ministry and the superintendents quickly returned to the regular routine of maintaining the artistic heritage of the country. The superintendents were responsible for determining priorities for their territories and submitting convincing proposals for restoration. A sampling of the projects that were approved in the late 1920s and 1930s will illustrate the important nature of the ongoing preservation work and how busy the provincial offices were with their ‘normal’ portfolios in the years before World War II. But the extent to which these projects took time and funding away from preparations for a future war will also become clear.

The first case features the Superintendency for Monuments of Lazio under the management of the long-serving superintendent, Alberto Terenzio, who specialized in the restoration of medieval churches and campanili. During the interwar period, Terenzio and his staff were occupied with architectural restorations and projects to address deferred maintenance on early ecclesiastical buildings in towns close to Rome. For example, in 1929 to 1930, Terenzio argued for an allotment of extraordinary funding so that urgent repairs could be carried out on the sacristy of San Francesco in Viterbo. In justifying the financial request, Terenzio reminded the minister of the artistic importance of the church, which had been built in the Romanesque style and housed late medieval funerary monuments of popes and members of their curias. Two papal sepulchres were positioned to either side of the apse: the Tomb of Pope Clement IV by Pietro Oderisi in about 1271-1274, and the Tomb of Pope Adrian V by a follower of Arnolfo di Cambio c. 1300 (Fig. 3.2). Because of the importance of preserving this architectural and sculptural ensemble, which commemorated the period when late medieval popes resided in Viterbo, Terenzio and the architect who worked with him submitted a proposal on 20 October 1929. The request was for 6600 lire to rebuild the roof of the sacristy beside the left transept, since the partial collapse of the roof had allowed rain to leak in. By the following June, after a few more urgent letters from Terenzio and the news of a local fundraising campaign to meet some of the costs, the minister agreed to contribute 5000 lire.74 This church and the heavy damage caused by Allied bombs in World War II will be discussed again in Chapter 6 on Viterbo.

Two more examples of restoration projects from the interwar period will be considered, both involving frescoes that were in poor condition primarily because of the uncontrolled environment in churches. The subject of preserving late medieval and early Renaissance frescoes during World War II is central to this book, and the wall paintings to be

Fig. 3.2. Interior of San Francesco, Viterbo. To the right of the apse: Follower of Arnolfo di Cambio, Tomb of Pope Adrian V, c. 1300; to the left of the apse: Pietro Oderisi, Tomb of Pope Clement IV, c. 1271-1274, present condition.

discussed in the following paragraphs either were destroyed or were detached and moved to safety during the war. About five years after Superintendent Terenzio’s work in Viterbo, the Ravenna office of the Superintendency of Medieval and Modern Art for Emilia-Romagna became heavily involved in a project to salvage the Trecento frescoes in Santa Maria in Porto Fuori, a church located fourteen kilometres east of Ravenna, towards the Adriatic coast. It had been erected in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries on the site of a smaller chapel from the ninth or tenth century, and the late medieval church took the form that was traditional in Ravenna with a basilican plan and brick construction. Dante had honoured the church with a reference in his Paradiso (Canto XXI), ensuring the monument’s enduring fame. By the 1930s, it became evident that the Trecento frescoes on the walls of the apsidal chapel and the two adjacent side chapels were suffering serious deterioration. The culprit was moisture in the walls due to both a high water table and poor drainage of rainwater. These frescoes were of considerable interest for the variety of the religious stories depicted, including scenes from the Life of the Virgin, events from the vite of several saints, and episodes from the Apocalypse. They were also valued because their style revealed the influence of Giotto on the local school of painting. The authorship is unresolved, as some continue to use the anonymous name introduced by Carlo Volpe, the Master of S. Maria in Porto Fuori, while others attribute the cycles to Pietro da Rimini in the years 1328-1332 (Fig. 3.3).75

In the late summer of 1936, the architect Corrado Capezzuoli, who was the Superintendent of Monuments for the provinces of Ravenna, Forlì, and Ferrara, submitted a long and carefully researched proposal to reduce the moisture in the church walls, accompanied by photographs and drawings.76 The large request was for 50,000 lire to implement the ‘Knapen system’, which involved the strategic insertion of drainage pipes to keep water away from the foundation of the church and from the base of its walls. In anticipation of the successful completion of the new drainage system, the Trecento frescoes were carefully restored in the summer of 1936, under the supervision of Cesare Brandi, who was then an inspector in the superintendency in Bologna. The treatment began with a consolidation of the loosened areas of painted plaster, followed by a thorough cleaning to remove salts and mould from the surface. There were substantial areas of paint loss, many of long standing because the conservation of the frescoes had been neglected for centuries. In compliance with the new ethical standards in Italy, these losses were not disguised by overpainting but instead filled in using flat fields of a neutral grey, water-based paint.77 Tragically, the medieval church with its Trecento frescoes, which had received so much attention in the 1930s, was almost completely destroyed by an Allied bomb on 5 November 1944. Only a few surviving sections of the fresco decoration were detached from the ruined walls so that they could be salvaged, as will be considered further in Chapter 5.78

The final example of a conservation project during the interwar period features Piero della Francesca’s donor portrait of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta with San Sigismondo,

Pietro da Rimini (attrib.), Christ Enthroned as Judge and Scenes from the Last Judgement , c. 1328-1332, fresco, arch over the entrance to the apse, Santa Maria in Porto Fuori, near Ravenna, before destruction during World War II. (Photo: Alinari Archives, Florence)

(Photo:

had discovered that the glaziers for Donatello’s Coronation of the Virgin were Domenico di Piero da Pisa and Angiolo di Lippo in the years 1434-1438 (Fig. 5.1).14

What even Poggi could not have anticipated was the precarious situation that arose for the portable art in shelters after Italy signed the armistice with the Allies in early September 1943. The immediate decision by the Germans to forcefully occupy Italy led to aerial and ground battles that invaded the countryside, where most of the deposits were located.The concern for art deposits within the orbit of Rome became more critical after the Allies’ Anzio landing on 22 January 1944. As the German army was forced into retreat, there was fear that Nazi officers and soldiers, covetous of the stored treasures, would steal from the deposits. During the German occupation of Rome, ministry staff, alert to the vulnerability of art in deposits, documented their conversations with members of the German Kunstschutz to preserve a record of the machinations.15

In response to these fraught circumstances, a group of ministry staff and superintendents travelled in trucks from Rome to the Marche, in the middle of active warfare in central Italy, to retrieve the cases of paintings and other cultural objects from galleries and museums in Rome, and also from churches and galleries in Venice and Milan, which were sheltered in the official national deposits at Carpegna and Sassocorvaro. They also recovered about one hundred forty paintings from galleries in the capital that had been in a deposit in Genazzano, east of Rome. Pope Pius XII, having refused to acknowledge the authority

of the Salò Republic in northern Italy in the final months of 1943, gave permission for the politically neutral zone of Vatican City to be used as a shelter for hundreds of crates of art.16 In the spring of 1944, further journeys were undertaken, despite the dangers, to retrieve paintings from churches and museums in towns in Lazio that were under fire, so that they could be more safely stored at the Vatican. Palma Bucarelli, who was Director of the Gallery of Modern Art in Rome, participated in one of these trips, on 7 February 1944, to a deposit in Caprarola, and observed the other rescue missions from the sidelines. Bucarelli chose the memorable phrase of ‘a Sisyphean labour’ to evoke the frantic and seemingly endless transfer of art from one shelter to another.17 These journeys to rescue art will be mentioned again in Chapter 6 in relation to Viterbo.

But in Florence, Superintendent Poggi resisted sending portable art from the Tuscan deposits to the Vatican. He became wary after receiving contradictory directives from the Salò Republic, from Rome, and from German commanders.18 Furthermore, the roads in Tuscany and northern Lazio were hazardous because of air raids. A group of Poggi’s colleagues, including Ugo Procacci, who was the director of the restoration laboratory, had experienced a bombing attack near Arezzo on 15 January 1944 during a trip to move paintings from Sansepolcro to safer storage near Florence. Procacci described how their truck, which was carrying Piero della Francesca’s Misericordia Polyptych (commissioned 1445, completed 1450-1461), among other works, was almost hit.19 Although the men and the paintings escaped harm, the incident made Poggi firm in his conviction that it would not be safe to transfer art from the province of Florence to the Vatican. One unexpected result was that the Nazis were able to confiscate many of the gems of the Uffizi and Pitti galleries from storage locations in the surroundings of Florence in August 1944 and to hide them in the South Tyrol.20

Similar to Superintendent Poggi, Ferdinando Forlati (1882-1975) brought decades of experience to his position as Superintendent of Monuments for the eastern Veneto. Nevertheless, Forlati struggled with the challenges he faced beginning in 1940. During World War I, he had worked under Commander Ugo Ojetti (1871-1946), who was appointed by the Ministry of War to organize heritage protection in the Veneto. Trained as an architect and an architectural restorer, Forlati supervised the protection of monuments in Venice. For instance, he managed the removal of the ancient bronze horses from the façade of the Basilica of San Marco and their transportation to Rome. Forlati also designed the defensive armature that was installed around Andrea del Verrocchio’s Equestrian Statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni (1480-1488) in the Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo.21 Since Venice suffered more aerial attacks than any other urban centre in Italy during World War I, Forlati gained firsthand experience of heritage protection. But despite all his knowledge, the Venetian superintendent felt ill prepared and unsupported when Italy entered World War II. He expressed his concern to colleagues because of the lack of clear instructions emanating from Minister Bottai and the paucity of resources for the implementation of protection. Forlati did not initiate the construction of barriers for the extraordinary buildings in Piazza San Marco until July 1940, and before May 1943, the Palazzo Ducale was without a water system for extinguishing fires.22

The direction Superintendent Forlati took reflected his substantial experience and his educated understanding of the strength of the weapons Italy would have to face during

171 THE FIRST RESPONSES TO THE WAR DAMAGE OF EARLY ITALIAN ART, 1943-1945

World War II. Since he had witnessed less powerful aerial attacks in World War I, Forlati was cognisant of the impossibility of protecting stationary art against direct hits by much heavier explosives. Consequently, Forlati selectively extracted fixed works of art to move them to deposits in the countryside. For example, in 1941, Forlati ordered the removal of two scenes from Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1304-1305), representing Christ Among the Doctors and the Way to Calvary.These frescoes had already been detached and remounted by Antonio Bertolli in 1891-1892.23 When the frequency of the attacks intensified, Forlati took the step of having several other small areas of the fresco decoration detached by the leading painting restorer in northern Italy, Mauro Pellicioli. Three tondi on the barrel vault of the chapel, one of the Virgin and Child and two representing prophets, were extracted, as well as another fresco of a prophet. The detached frescoes were then taken to the large refuge established at the village of Carceri near Padua.24

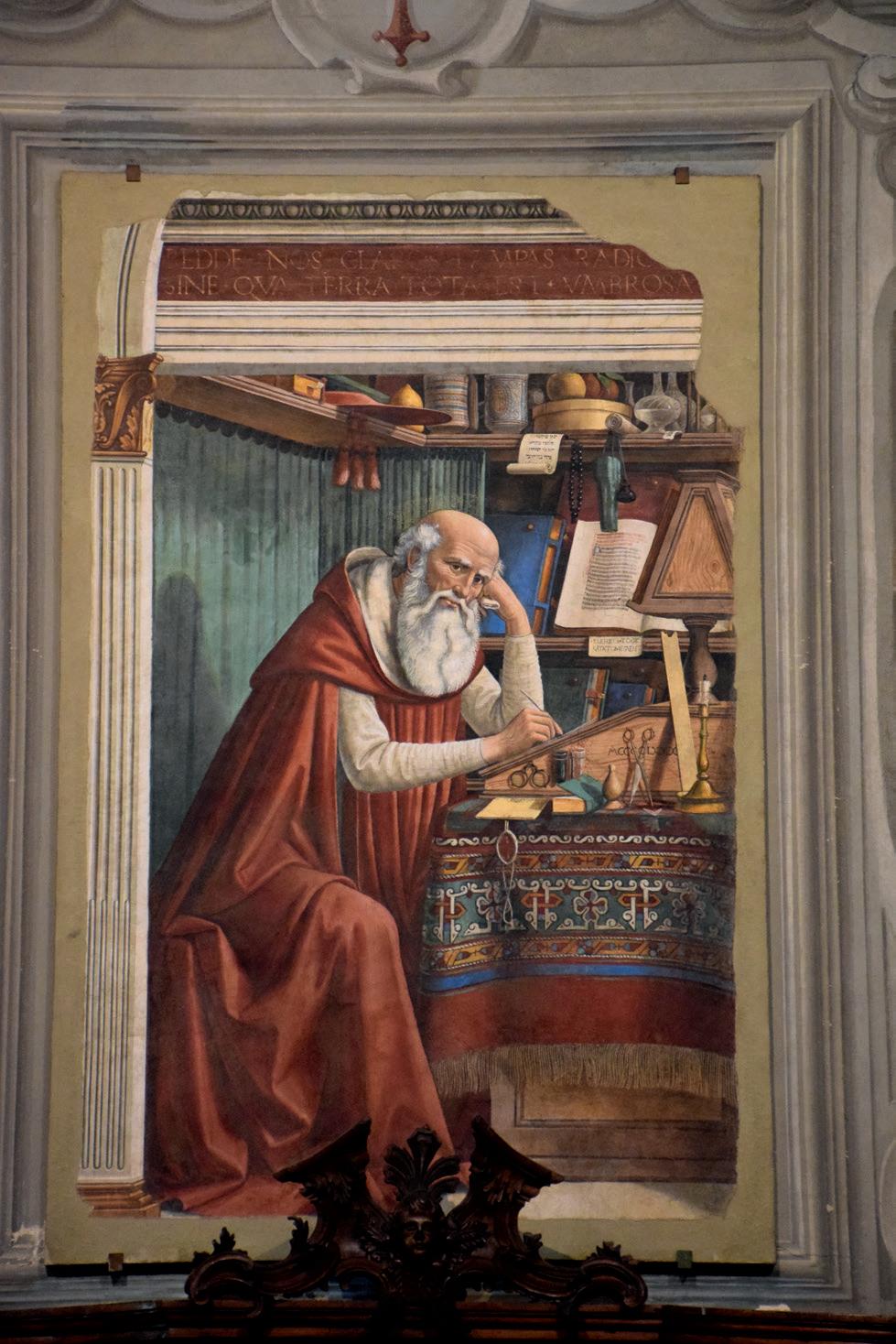

It was quite unusual for superintendents to have wall paintings preventatively detached as part of PAA to enable their storage in fortified shelters.25 The inexpert ‘strappo’ of Piero della Francesca’s Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta with San Sigismondo (signed and dated 1451, Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini), at the initiative of Superintendent Capezzuoli, when Rimini was being heavily attacked in May 1944, was discussed in Chapter 3 (Fig. 3.4). Two careful detachments were performed preemptively by the Florentine restorer Amedeo Benini on frescoes by Masolino in Empoli. One was Masolino’s Pietà, painted before the artist embarked on the Brancacci Chapel commission, which Benini extracted from the baptistery of the Cathedral of Sant’Andrea. Later, when Empoli’s historic centre sustained heavy damage, it was considered almost miraculous that Masolino’s frescoes were safe.26 However, the general aversion to the extraction of frescoes for their safeguarding is illustrated by the fact that some wall paintings that had been detached in the past were not removed to shelters. For instance, the memorable portrayals of the Church Fathers in the Ognissanti, Florence—namely, Domenico Ghirlandaio’s St Jerome in His Study (1480) and Botticelli’s St Augustine in His Study (c. 1480)—were not removed but protected on site (Fig. 5.2).27 Under the supervision of Giorgio Vasari in 1564, these frescoes had been detached from the tramezzo on which they were painted using the ‘stacco a massello’ technique, before the partition that divided the nave was torn down as part of the radical church renovations stimulated by the Council of Trent.28 Most of the plaster support was taken when the frescoes were detached, and they were rehoused on the nave walls. Although a removal for protection before World War II using the ‘strappo’ method would have caused structural alterations, the frescoes would not have been extracted from their original location, and it would not have been the first time they were detached.

There are a few examples of frescoes being detached during the war after the stability of buildings or supporting walls was undermined by attacks, but this was part of rescue work not PAA, as will be seen below in relation to the Triumph of Death in Palermo. Regarding Andrea Mantegna’s scenes in the Ovetari Chapel (1448-1457, Church of the Eremitani, Padua), three of the frescoes—the Martyrdom of St Christopher, the Transport of the Body of St Christopher, and the Assumption of the Virgin with the Apostles—were taken to safety before the chapel was destroyed in the air raid of 11 March 1944. These frescoes had been extracted previously using the ‘stacco’ method by Antonio Bertolli in 1886-1891, and therefore, strictly speaking, they were not detached but only removed from the chapel during World War II.29

On the whole, however, the protection of fixed artistic decoration in early churches posed an insurmountable problem in World War II, as Giovanni Poggi in Florence and Ferdinando Forlati in Venice recognized after their experiences during the Great War. A much larger geographic area was subject to attack and the destructive power of the weaponry was far greater. Certainly, the duration of the war in Italy for five years rendered the crisis more serious than the relatively short-lived, though severe, impact of previous natural disasters, particularly earthquakes. The entire country became engulfed in an emergency of horrific proportions, involving aerial, naval, and ground battles with warheads of terrifying strength. Moreover, the military circumstances were changeable and almost impossible to chart in advance. From the outset, the pattern of the bombing raids over urban centres was unpredictable, and the superintendency staff was not given warnings. After the battles on the ground began in September 1943, the direction of the fighting between the German divisions and the British Eighth and American Fifth armies could be anticipated to some extent. However, the air strikes by the Allies, intended to clear a path for the arriving ground armies, were less predictable. In addition, most of the superintendents were not sufficiently knowledgeable concerning the weapons that would be utilized and the damage that could result, since neither the Ministry of National Education nor the Ministry of War had been open and realistic about what lay ahead. The truth was that the dangers facing the Italian people and their artistic treasures were extreme.

THE FIRST RESPONSES TO THE WAR DAMAGE OF EARLY ITALIAN ART, 1943-1945

Workman points out the remains of a pier to Major Paul Gardner, probably November 1944. Photo by Captain Sheldon Pennoyer.

take his own photograph of the tomb’s condition (Fig. 5.15). The architect, Zampino, leans in behind him. Most of the relief sculpture on the front of the king’s sarcophagus has been revealed, and a small part of the supportive basement level can also be seen. In the foreground right, a sad stump is all that remains from one of the decorative pillars of the canopy. Thus, the photographs taken by Gardner or in his presence provide extensive visual documentation of the ruin to the presbytery and the labour of clearing the wreckage. In particular, they record the condition of the Tomb of King Robert as the rubble was being removed. These images attest to Gardner’s intermittent involvement over the course of thirteen months in the clearance of the presbytery and the uncovering of the buried tombs. Furthermore, the photographs that include Gardner with his own camera supply evidence of his concern to capture the damage to one of the artistic treasures of Naples. They also provide visual records of Gardner’s cooperation in his role as the Allied Fine Arts Officer with the Naples superintendency for the salvage of heritage, since Gardner and Zampino appear together in a number of the images.135

Very aware of the limitations of his knowledge and time, Gardner also requested that the superintendency staff submit written evaluations of artistic and architectural damage in Naples and its surroundings. Dr Sergio Ortolani supplied Gardner with several condition reports on works of art in Campania. Ortolani had been Director of the Royal Picture Gallery in Naples since 1930, and before that, he had held the rank of inspector in the superintendency. He had studied art history under Pietro Toesca and Adolfo Venturi and wrote on many periods of Italian painting, from the fifteenth to the early twentieth century. In addition, Ortolani took special interest in the condition and restoration of works of art, and had established a laboratory for the scientific examination and restoration of art as part of the superintendency in Naples in 1932, although the facility was closed in 1937, when the Istituto Centrale del Restauro (ICR) was established in Rome. But Ortolani’s rise in the superintendency administration had been delayed because of his refusal to join the National Fascist Party.136

Ortolani forwarded to Gardner the annotated lists he had prepared of noted works of art in Campania that had been compromised by the war, in which he separated the art according to its importance and the severity of the damage.137 The three Angevin tombs behind the altar in Santa Chiara appeared on Ortolani’s list of ‘destroyed’ works of art, and his descriptions indicated that he had examined the tombs as the wreckage was being removed. Ortolani devoted most of his attention to the condition of the Tomb of King Robert because of its ‘rich’ and ‘precious’ sculptural decoration. As he explained clearly and without obvious emotion, the top half of the tomb and the monumental canopy had been destroyed by the fire, which had reduced the intricately carved marble to a calcined and friable material. Applying formal evaluations to distinguish the quality of the carving in each part of the monument, Ortolani mitigated, to some extent, the significance of these losses when he explained that the statues of the seated king and the group in the gable were ‘mediocre’ works by lesser masters in the Bertini workshop.138 On the other hand, most of the lower sections of the tomb had been saved, including the personifications of the Seven Liberal Arts (with the exception of one partially damaged head) and the double pillars with the Virtue caryatids. Ortolani expressed his opinion that the lower storeys had been protected from the fire both by the sandbags and by the accumulation of rubble. In a similar though

201 THE FIRST RESPONSES TO THE WAR DAMAGE OF EARLY ITALIAN ART, 1943-1945

Tomb

King Robert

Close-up of the Seven Liberal Arts and the king’s effigy, probably November 1944. Photo by Major

November

and as personal intercessors for those in search of salvation. For example, Antonio Veneziano, in his scenes of St Ranierus, documented the saint’s local ties through the insertion of easily recognizable scenery. The circular baptistery in the Posthumous Miracles of St Ranierus, from which only a few fragments have survived, confirmed the Pisan location of the sacred events.60 In the Return and Miracle of St Ranierus, the heavily laden, seagoing vessel would have been familiar to Pisans because of the busy, trading port (Fig. 7.10). Ranierus had turned away from his life as a merchant-trader to become a pilgrim in the Holy Land and later an ascetic, holy man in Pisa. By placing an emphasis on the Pisan identity of Ranierus, he became more accessible to local people as a spiritual guide. In addition, textual inscriptions under the scenes and inserted into the picture space helped to clarify the meaning.61

Regarding Spinello Aretino’s scenes of Sts Ephesius and Potitus, Vasari described the frescoes at length and recorded that they were in an ‘excellent state of preservation’.62 In the second edition of the Lives, it is readily apparent that Vasari not only favoured Spinello, who was his compatriot, but also that he saw this cycle as the highlight of the artist’s career, largely because Spinello had followed in Giotto’s footsteps at the Camposanto. Spinello’s scenes are also important because the hagiographic legends of these early Christian martyrs were rarely depicted. Stefan Weppelmann, in his recent monograph on the artist, identifies manuscript accounts of the lives of the saints that may have served as sources for the imagery.63 Presumably, Spinello also depended upon visual precedents for such large and detailed pictorial narratives. One proposal is that ancient reliefs on sarcophagi in Pisa inspired Spinello to represent the drama of war, as in the Battle of St Ephesius against the Pagans in Sardinia, but manuscript illuminations of Old Testament battles likely also served as models.64

7.10. Antonio Veneziano, Return and Miracle of St Ranierus, 1384-1386, south corridor, Camposanto, Pisa, present condition.

The west wing of the Camposanto can be passed over quickly since, according to conservation research, the wall was left free from paintings during the Trecento and Quattrocento. The murals in the hallway, which depict the biblical heroines Esther and Judith, were carried out much later under Medici patronage—in 1585-1616.

At the same time as Spinello was completing his cycle in the south corridor, the decoration of the north corridor was begun by Piero di Puccio in the years 1389-1391. The artist, whose reputation was built on his work in Orvieto Cathedral, was invited by the Opera to fresco the long, north hallway with an Old Testament cycle, but he left after completing the first stages of the decoration. Piero di Puccio painted the Theological Cosmography and three scenes from Genesis in the western section of the hallway, as well as the Coronation of the Virgin over the entrance to the Aulla Chapel.65 Some innovative features are evident in the Coronation, where the traditional setting has been altered by placing the heavenly courtroom within a domed temple to fill the rectangular field above the doorway. As the underdrawing reveals, Piero di Puccio took a painstaking approach to the composition, which involved substantial revisions. Areas of the unusually detailed sinopia were already exposed because of losses in the lower part of the fresco before the war, but when the Camposanto was struck and caught fire, more of the intonaco fell away (Fig. 7.11).66

To initiate the cycle of the Old Testament in a grand fashion, Piero di Puccio filled the west corner of the hallway with a depiction of God as creator of the geocentric cosmos (Fig. 7.12). Instead of scenes narrating the stages of God’s creation of the universe and the earth as described in Genesis, this was a symbolic, non-narrative image that called upon the knowledge of the viewer for interpretation. The fresco encapsulated the Christian understanding of the organization of the macrocosm as fashioned by God, which was familiar to educated viewers from treatises such as Johannes de Sacrobosco’s De sphaera mundi, c. 1230.67 Sacrobosco’s primer was used in the teaching of astronomy as part of the quadrivium in schools.Written in a clear and systematic manner, a style mirrored in the schematic quality of Piero di Puccio’s mural, Sacrobosco introduced the cosmos as comprised of spheres within spheres, with the Earth at the centre and, beyond the limit of the spheres, the celestial realm. Sacrobosco described the earth according to the ancient scientific belief that everything in the terrestrial realm was composed from four fundamental elements.

In the Camposanto fresco, the Earth is represented as surrounded by the other three elements in sequence: water, air, and fire. Piero di Puccio added details not mentioned by Sacrobosco when he mapped three regions on the surface of the Earth (Asia at the top, Europe on the bottom left, and Africa on the bottom right)—a tradition that can be traced back to Herodotus. Above the terrestrial world, the artist depicted the crystalline spheres, which were believed to carry the moon, the sun, and the planets and to rotate in perfect circular motion around the Earth. Just above the spheres of the planets was the band of the fixed stars, or zodiac constellations. Beyond the fixed stars, the artist represented the nine rings of the angelic hierarchy. Textual inscriptions on the fresco—on the open books held by the diminutive figures of St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas in the lower left and right corners and in the poetic verses that were once legible just below the painting—reminded viewers of the theological importance of the orders of the angels, an extraordinary aspect of God’s creative power.68 Finally, Piero di Puccio pictured God offering the universe that he had made. This striking and iconographically rich image of the divine order of the cosmos

Fig. 7.11. Piero di Puccio, sinopia of the Coronation of the Virgin , 1389-1391, Camposanto, Pisa, present condition after detachment and rehanging over the Aulla Chapel door.

Fig. 7.12. Piero di Puccio, Theological Cosmography, and Adam and Eve, 1389-1391, and Benozzo Gozzoli, Wine Harvest and Drunkenness of Noah , 1468-1484, north corridor, Camposanto, Pisa, present condition.

TRECENTO FORUM

In Italy, art historians can study wall-paintings, tombs, and stained-glass windows in the early churches for which they were created because they have been preserved in situ over the centuries. This book explores one fraught period of this critical preservation work, during the five years of World War II in Italy, when numerous artistic monuments of value were vulnerable to damage and destruction. Works of art from the late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance lie at the focus, among them, the Angevin tombs of Santa Chiara in Naples, the frescoes of Pisa’s Camposanto, Piero della Francesca’s wall-painting of Sigismondo in the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, and the Mazzatosta Chapel in Viterbo. Rooted in the archives, the narrative charts the formidable task of safeguarding stationary art in the midst of aerial and ground attacks. Taking centre stage are the struggles endured by heritage superintendents, the innovations tested under pressure by art restorers, and the desperate position of clerical custodians of churches. The Allied Monuments Officers, who arrived over halfway through the war, provided substantial assistance in the rescue of damaged art from ruined buildings. This study offers an original perspective by emphasizing the Italian protagonists, whose efforts played out against the political and economic landscape of fascism and the devastation wrought by the war on Italian soil.

ISBN 978-2-503-60974-4