Eleonora Pistis

Eleonora Pistis

Acknowledgments 7

Note for the Reader 10

Introduction 11

Drawings 18

Library-Laboratory 19

People 21

Geographies 23

Book Chapters 24

Chapter 1 I Am Architecture: Hawksmoor and Queen’s College 29

The Vice-Chancellor and Architecture 35

The Architect’s Knowledge 38

Knowledge on Display 45

Oxford’s Doors Open 55

Chapter 2 Architecture into a Book: Aldrich and The Elements 59

The Dean and the Books 62

Architectural Learning and the Instruction of “Young Students” 65

Taxonomy, Order, and Disorder 69

Images in Translation 76

Ornament, Rules, and Licentia 78

History between the Ancients and the Moderns 82

Chapter 3 Architecture of Knowledge: Clarke and the Library-Laboratory 93

The Don and Architecture 96

Unlocking the Study 101

A Library of a Library 107

Too Much on the Shelves 112

Networks of Objects, Networks of People 121

Learning and Academic Experimentation 126

Erudition in Stone 137

Chapter 4 “Generall Draughts, and Regular Schemes” (1710–1712) 145

“The Genius that Now Seems To Govern” 148

The Printing House 158

Imagining and Planning a New University 163

The Enlargement of the Bodleian Library 168

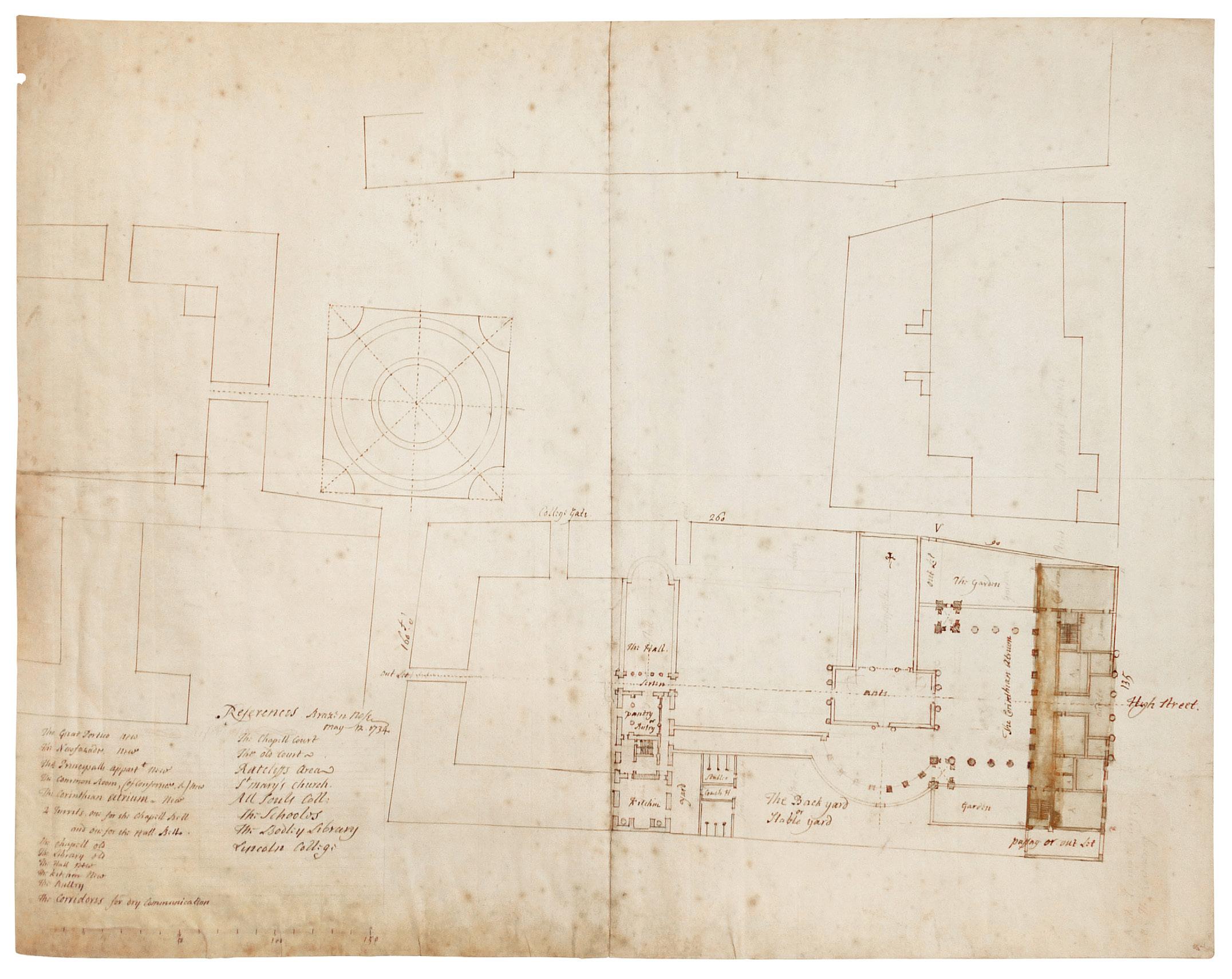

Chapter 5 “Accademia Oxoniensis Amplificata et Exornata” (1713–1714) 177

The Forum and Radcliffe 180

All the Souls of Books 190

The Temple-Church 197

Town and Gown 207

Chapter 6 Coming to Terms with History (1714–1736) 213

A Bubble of Credulity: 1720 215

The Explanation 219

A Reasonable Uniformity 227

The Printed City: 1733 236

For “Diversion” and “Good Wishes” 241

Almost There! (1736) 246

Chapter 7 Conclusion: Architecture and Knowledge 253

Abbreviations 263

Notes 264

Bibliography 291

List of Illustrations 306

Index of Names 316

Index of Places 321

fig. 1.6 Henry Cheere (attributed to), Nicholas Hawksmoor, c. 1736, plaster, Oxford, All Souls College, Buttery.

fig. 1.7 Nicholas Hawksmoor, View of Oxford, from his Topographical Sketchbook, c. 1680–1683, brown ink, pencil and wash, 195 × 165 mm (sketchbook measurements), London, Royal Institute of British Architects.

Determining what Hawksmoor knew when he arrived at Oxford in his late forties is not an easy task (Fig. 1.6). Very little is known about his education.40 Only a so-called topographical sketchbook, now kept at the RIBA , survives from the early stages of his career. Most likely executed between 1680 and 1683, it includes drawings of the cities of Nottingham, Coventry, Warwick, Bath, Bristol, Northampton, and Oxford (Fig. 1.7). As Kerry Downes explained, the drawings have varying levels of complexity and polish, but largely remain “crude in style.”41 However, they are precious documents because they contain the seeds of many aspects of Hawksmoor’s work that will emerge in the following chapters. These drawings should not be dismissed as a mere indication of little training. To be sure, the sketchbook does not include any complex orthogonal projections and reflects a limited knowledge of the conventions of architectural representation. This limited knowledge is particularly evident from Hawksmoor’s use of perspective—for instance, in the drawing of the Market Cross at Bristol (Fig. 1.8).42 In addition to such perspectival views, the sketchbook contains only simple plans and elevations, including those of Nottingham Castle.43 While Hawksmoor acquired more refined drawing skills later in his life, as his drawings for St. Paul’s clearly demonstrate, some of his drawings for Oxford projects suggest an architect who had not been constrained by Vitruvian rules of architectural representation during the early stages of his training. In particular, some of his maps of Oxford (esp. Fig. 5.2a and Fig. 5.4a), executed around 1712–1714, evoke a familiarity with the medieval method of surveying large complexes and towns by producing unmeasured plans with some embedded elevations.44 Hawksmoor’s topographical sketchbook reveals close ties to both the content and the technique of the prints that depicted medieval cathedrals and churches and that were produced by men such as William Dugdale (1605–1686) and Daniel King (1616–1661). These prints were published and sold by John Overton (1640–1713) in London across the later seventeenth century (Fig. 1.9). We even know that Hawksmoor acquired a copy of Daniel

fig. 1.8 Nicholas Hawksmoor, Perspective of the Market Cross, Bristol, from his Topographical Sketchbook, c. 1680–1683, brown ink, pencil and wash, 195 × 165 mm (sketchbook measurements), London, Royal Institute of British Architects.

fig. 1.11 Nicholas Hawksmoor, View of Chapel Bar, Nottingham, from his Topographical Sketchbook, c. 1680–1683, brown ink and pencil, 195 × 165 mm (sketchbook measurements), London, Royal Institute of British Architects.

fig. 1.9 Daniel King, Bathensis ecclesiae cath. facies occidentalis (View of the west façade of Bath Abbey), from Monasticon Anglicanum (London, 1655), engraving, 240 × 168 mm, Oxford, Worcester College. [GC]

fig. 1.10 Nicholas Hawksmoor, View of Bath Abbey, 1683, from his Topographical Sketchbook, c. 1680–1683, brown ink and pencil, 195 × 165 mm (sketchbook measurements), London, Royal Institute of British Architects.

King’s The Cathedrall and Conventuall Churches of England and Wales (1656), which he interleaved and annotated in 1720.45

More broadly, the topographical sketchbook reflects familiarity with the graphic conventions typical of seventeenth-century topographical prints. This familiarity is particularly evident in Hawksmoor’s use of heavy cross-hatching, as for example in his sketch of Bath Abbey (Fig. 1.10) and in his views of cities.46 As will emerge from this book, an important aspect of Hawksmoor’s work for Oxford and elsewhere that has not been fully recognized is his role as an author of prints.

The subjects of Hawksmoor’s drawings in the sketchbook suggest that he trained himself by observing medieval buildings—knowledge that would prove useful when he needed to negotiate the Gothic heritage of Oxford and when he created new Gothic designs for the city. His rendering of Gothic buildings demonstrates attention to light and shade, volumes, urban scales, and vistas framed by buildings. As I will show in Part II, this attention to the urban aspects of building would prove to be crucial in his contributions to the replanning of Oxford. In particular, the vistas framed by gates and doorways that he captured in his sketchbook contain the seeds of what he would create for the University of Oxford years later (Figs. 1.10, 4.20). Very early in his career, Hawksmoor seems to have understood the power of architecture in guiding humans’ bodily experience of a space, and this understanding would lie at the root of his designs later in his life.

In sum, Hawksmoor’s approach appears to have been relatively similar to that of his European contemporaries since he too observed and copied. However, what he observed and copied and the techniques that he employed were markedly different.47 Many of his European colleagues would have begun their architectural training with the study and reproduction of the proportions of the five orders as found in treatises (such as Vignola’s Regola) and, when possible, the first-hand observation of antiquities. In contrast, Hawksmoor did not consider measurements, orders, proportions, compass-based rules, or orthogonal projections of Classical architecture across his sketchbook. He did not even create canonical architectural sketches, such as the rapid Italian schizzi of Ferdinando Galli Bibiena (1657–1743). While geometry and the structural solidity of buildings would become an essential part of his design process (as particularly evidenced by his drawings for the Radcliffe Library; see Chapter 5), it seems that Hawksmoor at this stage was primarily learning from

fig. 1.12 Nicholas Hawksmoor, View of Coventry from the south, with the south façade of St Michael’s church in the foreground, from his Topographical Sketchbook, c. 1680–1683, brown ink, pencil and wash, 195 × 165 mm (sketchbook measurements), London, Royal Institute of British Architects.

fig. 1.13 Henry Hulsbergh (after Nicholas Hawksmoor), Perspective and Plan of the Church of St Mary-le-Bow, London, c. 1720–1723, etching and engraving, 679 × 474 mm, London, Royal Institute of British Architects.

the observation of the kind of “beauty” that was linked to the use of the “Senses” and to “familiarity”—to borrow Wren’s words.48 He was studying what made a building appear solid more than what would make it solid. Across his sketchbook, Hawksmoor could train himself by exploring the effects of buildings (rather than their geometry) through views, combinations of solids and voids, and contrasts between light and darkness.

The way in which he captured the Church of St. Michael’s, Coventry, and All Saints Church, Northampton, demonstrates his clear interest in these types of effects (Fig. 1.12).49 This interest extended to other enterprises—for example, his powerful 1695 bird’s-eye view of St. Mary Warwick, which is preserved today at All Souls College, and the prints that he executed later in his career (Figs. 1.13, 2.26–27).50 It is even possible that he trained himself by directly copying prints, rather than by observing buildings firsthand. It is likely that he used prints as his models for observing architecture, perhaps with the goal of acquiring skills that could lead to a job in publishing. An entry in the sale catalogue of his library seems to suggest his copying of prints because it lists a view of the Piazza Navona in Rome “by Hawksmoor.”51 As far as we know, he never left British soil. He therefore had to rely heavily on prints and books to feed his knowledge and spark his imagination.

Hawksmoor joined Wren’s office around 1683, and it is likely that at the beginning, he especially acquired administrative skills, such as listing materials, making economic estimations, and managing the delegation of labor.52 Over the years, the scope of his role within the office expanded and allowed him to develop more complex skills. In terms of practical experience, this well-known and widely discussed apprenticeship with Wren, alongside his collaboration with Vanbrugh and his solo work at Easton Neston, contributed to shaping the skills that he possessed by the time that he arrived in Oxford as a mature, multitasking architect.53 By that point, he knew how to handle complicated geometrical drawings and multiple aspects of building design and production, even if he never actually became a skilled free-hand draftsman such as someone like Juvarra.54 Already in the 1680s, Hawksmoor had experimented with library design and so was well aware of the different needs and facets of libraries. He made drawings for a library at St. Paul’s Cathedral and for the library at Trinity College, Cambridge (Fig. 1.14).55 This experience would become useful later in Oxford, when libraries and their designs were a central issue.

fig. 3.10 George Clarke, Plan and interior elevations of his study at All Souls College, 1705–1736, brown ink and grey wash, 483 × 317 mm, Oxford, Worcester College. [GC]

accommodated a library that provided Clarke with an inexhaustible source of “satisfaction” and “amusement” (Fig. 3.11).35

The wooden bookcase designed to host the volumes of his collection contained shelving units that mimicked a regular rhythm of bays with Doric responds doubled up at the corners. Looking more closely at the vertical jambs, the visitor would most likely have seen a serrated profile, such as the one depicted in another drawing in Clarke’s collection that shows a wooden bookcase in the form of a Doric temple front and that is attributed to John James (Fig. 3.12).36 This innovative solution made it possible to adjust the heights of the shelves according to the various sizes of volumes.37 The small shelves inserted into the responds were generally used to hold octavo and duodecimo volumes, while the larger shelves within the bays accommodated quarto volumes and folios. A similar arrangement appeared in the shelves planned for Worcester Library by Clarke and still survives today (Figs. 3.13–14). Inside the room, visitors could have let their eyes roam in every direction, observing the titles of hundreds of books, many of which were easily reachable by hand and without a ladder. Moving their bodies,38 and lowering their gaze to the base that ran the length of the library, they would have caught a glimpse of the hidden drawers that, when opened, would probably have revealed loose drawings and prints.

Interrupting the library on the east wall and dominating the center of the wall was a fireplace. On damp winter days, the fireplace would have offered warmth to those (most likely Clarke himself) who had selected their readings and decided to linger in front of the adjacent

Madrid, 31 January 1736: Filippo Juvarra, struggling with severe pneumonia, lay on his deathbed. One can only imagine what goes through an architect’s mind in his final moments—perhaps a recollection of the most magnificent building that he has ever seen, or a dreamlike image of a never-realized project, or a last-minute reflection on the destiny of a structure that is still under construction. In any case, the death of “the architect of the Capitals” symbolically marked the end of a generation.1 His generation was the first to be shaped by academic experimentation, by a strong interest in historical inquiry, and by libraries that contained an unprecedented quantity of books and prints. It was a generation that shared knowledge across Europe as never before and that was required to respond to an increasingly expanding colonial world. Many architects traveled, and even those who physically remained at home journeyed via proxy.

To this generation belong Hawksmoor and Clarke, both of whom died the same year as Juvarra: 1736. By serendipity, the grumpy architect and the clever All Souls Fellow also probably shared their year of birth, and, surely from age forty-seven, their plans and visions for a new Oxford.2 Although Hawksmoor often complained about people, I have not come across evidence that he ever found fault with Dr. Clarke or his many requests over the years—not a few of which he could well have regarded as a waste of time. Both men died at a moment in which their long-held dreams were nearing fruition. Throughout their friendship of sorts, they shared many moments of hope and disappointment.

In this final chapter, I reconstruct the development of the projects that Hawksmoor outlined in 1714; I focus specifically on the fate of Plan 6. The outcome of this plan depended on the fate of the Radcliffe Library (Fig. 6.1). Despite the wishes of many individuals, it was a long time before the final result was finally achieved. In the following pages, I trace this previously unwritten history, which was remarkably affected by the South Sea Bubble in 1720. By so doing, I consider a number of architectural initiatives that occurred after the death of Queen Anne—a time that was anything but stagnant.

First, once it had been decided that All Souls would need to face the future university forum to its west, it was possible to devise a final design for the building’s renewal, and construction could begin. Hawksmoor, the author of the chosen project, wrote for Clarke and the academics of the college a long “Explanation” to accompany his drawings. This document is the most extensive written account of his work for Oxford. I use it here to examine his attitude towards the two crucial components of his projects for the university: the urban aspect of his designs and the mediation between Gothic and Classical architecture. Regarding Hawksmoor’s Gothic work for All Souls, Colvin argued that he “seized on the salient

Terms with History feature of a half-forgotten style and exploited them without any pretention of scholarship.”3 While it is true that Hawksmoor did not seek to display “scholarship” as we define it today, his short notes and his long explanation for All Souls together place his designs within a broader, pseudo-scholarly dialogue on architecture and its history that he had been conducting with Clarke for quite some time. This dialogue occurred via exchanges of designs, information found in books, and knowledge acquired thanks to practical experience.

In the years that followed the creation of Plan 6, Hawksmoor was working for Clarke—“for [the sake of the latter’s own] diversion” and his own “good wishes”—on the renovation of Brasenose (1724) and Magdalen Colleges (1720–1734). In a manner similar to his approach for his designs of Worcester College (1714–1720), which I addressed in Chapter 3, he made explicit references to architectural knowledge found in books. For Brasenose and Magdalen, he seems to have referred to Aldrich’s treatise in particular. Noteworthy is the fact that across his interactions with Oxford’s academic community, Hawksmoor inserted an increasing quantity of explicitly erudite references into his drawings. This practice of augmenting images with pseudo-scholarly notes is surely an indication of Oxford’s significant contribution to the shaping of his identity as the learned architect described in his obituary—a characterization that I addressed at the beginning of this book.

In this final chapter, I also discuss Clarke, who continued to collect designs, prints, and books. I consider two materials from his library that are of particular significance because they summarize and symbolize his constant, twenty-five-year engagement with the architecture of Oxford. A printed map from 1733, which has not been discussed in previous scholarship, offers tangible evidence of the urban history that I have been tracing here in Part II. The other item is what I would call a hybrid object: a book containing maps, prints, drawings, and prints onto which drawings have been pasted. The volume was bound by Clarke and illustrates several Oxford projects, some realized, some yet to be accomplished, and others that never saw the light of day. Many of these projects involved Clarke and Hawksmoor. This object thus epitomizes the complexity of the multimedia process that shaped early eighteenth-century Oxford, as it locates the university and the city between unattainable visionary aspirations and real achievements.

In the previous chapter, I left Hawksmoor at his desk dealing with Plan 6 and figuring out all of the different projects that he had been contemplating across the first months of 1714. As mentioned, Clarke and other eminent individuals from the university must have conversed with each other in front of his large drawing. On 13 September 1714, confirmation that their ideas would proceed as expected finally arrived. Several weeks before his death, Dr. Radcliffe dictated his will, stating:

[I] Will, that my Executors pay forty thousand Pounds in the Term of ten Years, by yearly Payments of four thousand Pounds, the first Payment thereof, to begin, and be made after the decease of my said two sisters for the building a Library in Oxon, and the purchasing the Houses […] between St. Mary’s and the Schools in Catstreet, where I intend the Library to be built; and when the said Library is built, I give one hundred and Fifty Pounds per annum for ever, to the Library-Keeper thereof, for the time being; and One hundred Pounds a Year, per Annum, for ever, for buying Books for the same Library.4

fig. 6.10 View of the Library of All Souls College (left; Nicholas Hawksmoor, 1716–1721) with the Radcliffe Library (right; James Gibbs, 1737–1749, right).

Although Hawksmoor had stated in his “Explanation” that, like the exterior, the interior of the library would be Gothic, the 1717 print reveals that, by then, he was planning an all’antica library on the interior, just as the library would be in the completed building (Figs. 6.10–11). This was not the first time in which a building in Oxford was Gothic on the outside and Classical in the interior.77 In his detailed analysis of the structure of All Souls, Anthony Geraghty has already shown how in the covered passage between the front and north quadrangles, Hawksmoor eventually blended Classical structural systems (groined vaults and domed structures) with a Gothic shell. For the hall, which is located in the east half of the south range, and for the library, which occupies the entire north range, he created a structural relationship between the Gothic exterior façade and the Classical interior. Classicism does not control the totality of the design, but some of its principles have informed Hawkmoor’s choices, especially the way in which he corrected the “irregularities” of the Gothic with symmetry and order.78

Clear evidence of this complicated dialogue between Gothic and Classical can be found in the drawings where Hawksmoor proposed a metamorphosis of a tripartite gothicized window into a Serlian window (Fig. 6.12).79 Here the intertwining of Classical and Gothic becomes so physically tight that they are blended in probably the most emblematic manifestations of the “reasonable uniformity” pursued by Hawksmoor in Oxford.80

Despite his earlier decision to build the north quadrangle of All Souls in the Gothic style, he had also admitted in his “Explanation” that he had tested an all’antica solution and

fig. 6.11 Nicholas Hawksmoor, West window of the Library of All Souls College, c. 1716–1721.

fig. 6.12 Nicholas Hawksmoor, Study for the west window of the Library of All Souls College, c. 1716–1718, ink, pencil and grey wash, 601 × 485 mm, Oxford, All Souls College.

designed “a Portico and a Gate (next to ye Great Piazza) after ye Roman Order” just “to Shew” that he and Clarke were “not quite out of Charity with that ma[n]ner of building.”81

The final design for the north quadrangle is in a modern Gothic language that combines Romanesque, Moorish, and Perpendicular features.82 Although the design has been interpreted as proof of Hawksmoor’s lack of historical knowledge, it can equally be viewed as the result of a design process similar to his process for composing in a Classical language (for instance, at Queen’s College): consciously intermingling elements from different periods and places.

Overall, the quadrangle that Hawksmoor designed was based both on a medieval prototype and, as already suggested, on the Parisian hôtel de ville, especially the Palais du Luxembourg, which had already been a point of departure for the Queen’s College designs.83 The west entrance is located at the center of a low range and is marked by a domed pavilion, as at Queen’s College and the Palais de Luxembourg (Figs. 1.4–5, 6.9). This low range provides a screen for the opposite east range, where the church-like façade of the Common Room and the “Great Dormitory” is located (Fig. 6.13).

Even the project for All Souls and the plans for Brasenose were reconsidered, albeit briefly, in the wake of the enthusiasm roused by the financial speculation of 1720. Hawksmoor was once again the one who tested new ideas and coordinated them within the urban context. In 1720, the All Souls’ library was nearly complete, and construction was about to begin on the north quadrangle’s northern tower and the strip of residences between it and the library. Having taken control of the project, which had been approved in 1715 and only slightly modified subsequently, Hawksmoor now came up with three alternatives for the range that would

fig. 6.13 View of the north quadrangle of All Souls College (right; Nicholas Hawksmoor, 1716–1721) seen from the “Forum” (today: Radcliffe Square, c. 1733–1736) with the Radcliffe Camera (left; James Gibbs, 1737–1749).

fig. 6.14 Nicholas Hawksmoor, Proposition I for a gateway and screenwall of All Souls College, plan and elevation, 1720, brown ink and grey wash, 508 × 737 mm, Oxford, Worcester College. [GC]

face the future forum and that would be located between the chapel and library. For the external elevation, he proposed solutions in which he tested Gothic, Roman, and Greek idioms. These alternatives attest to Hawksmoor’s conception of a certain equality and interchangeability of different styles.

The Gothic solution “after ye Monastic manner” is the closest to what was eventually realized (Figs. 6.13–14).84 Hawksmoor’s use of “Monastic” suggests a specific choice within the wider label of “Gothick,” which, as we have seen, Hawksmoor used for other designs. According to his own account of the periods of architectural history, which he would write fifteen years later and which I discussed in Chapter 2, the “Monks” used “Arches semicircular;” these arches are the only element that clearly distinguish this project from Hawksmoor’s “Gothick”

fig. 6.33 Nicholas Hawksmoor, Plan of the “Forum” with an outline for the Radcliffe Library and a project for Brasenose College, 1734, ink and grey wash, 470 × 600 mm, Oxford, Brasenose College.

lies in the beveling of the base’s angles, which are now concave (Fig. 6.33). In addition, the building appears to be freestanding for the first time. While its north-south axis is aligned with the entrance to the Schools, its east-west axis is aligned with the façade of Library of All Souls. No longer centered in the forum, the Radcliffe Library’s mass nearly reaches the edge of the Exeter College garden and the outer walls of Brasenose. In an alternative solution, Hawksmoor proposed a plan in which the new library was to be connected to the southern side of the Schools via a T-shaped volume so that the north-south axis was shifted eastward and was more centered within the forum.123 At the same time, a direct link between the Printing House and the forum was partly maintained (Fig. 6.34).

Despite the lack of elevations, it is apparent that these two schemes are closely related to the wooden model (the so-called Design VIII), which was constructed at the behest of the Trustees in 1735 and which has come down to us in damaged form.124 The similarities between these schemes and the model suggest that Hawksmoor was most likely the author of the design on which the model was based. The model does not seem to be connected to the Schools building, but the absence of a connection between the first and second floors may suggest that Hawksmoor planned to include a bridge between the Radcliffe and the Bodleian Library. The presence of a vestibule corresponding to one of the subsidiary spaces on the side seems to confirm this hypothesis.125 The vocabulary too has changed and, compared

fig. 6.34 Nicholas Hawksmoor, Plan of the “Forum” with a layout for the Radcliffe Library, c. 1734–1735, brown ink with grey and yellow washes, 540 × 370 mm, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum.

with Design VII, results in a more rigid composition that is more clearly inspired by antiquity. Engaged Composite columns frame alternating niches and windows, while the corners of the rusticated basement are concave, as in the designs illustrated in Figs. 6.33–34.

In May 1735, Hawksmoor was paid £70 sterling for his drawings for the Radcliffe Library; next to his name appears that of James Gibbs, who received £42.126 It is not clear whether Gibbs at that stage was simply assisting Hawksmoor in making the drawings necessary for the library to be constructed. During early 1736, Radcliffe’s last surviving sister died, and it was finally possible for the project that Hawksmoor and Clarke had been working on for twenty-five years to be realized. They were almost there!

By a stroke of bad luck, however, Hawksmoor died on 25 March 1736 and was followed to the grave by his friend Clarke on 22 October. Like for Juvarra, one can only wonder whether the fate of Oxford architecture passed through their minds in their final hours.

On 29 January 1737, Willian Busby wrote to Richard Rawlingson:

From Oxford I hear the model for the Library is much liked but the only objections are that the design on a communication with the other Library will not bear. The passage thro’ the Schools, if continued will lye too near Brazen Nose, whereas according to the model it should go thro’ the center, so that the scheme for a thorough view from the Printing House to St. Mary’s will be impracticable 127 [Italics my own]

On 4 March 1737, James Gibbs appears as the official architect of the Radcliffe Library, which was completed following his design and direction between 1737 and 1749 (Figs. 6.35–36).128 Although the formal layout of Hawksmoor’s final plans—particularly Design VII—was mostly retained, Gibbs’s building as constructed ignores Hawksmoor’s slow and thoughtful process that had rationally woven together architecture and urban space, tradition and shocking novelty, and representation and function—all aspects that were crucial to the conception and visualization of Oxford as the “Seat of ye Muses Admired at home and Renowned abroad.”129

Gibbs’s rotunda, set at the center of the square and occupying a significant part of what had once been envisioned as a “Forum,” disregarded parts of the fundamental reasoning behind the overall layout. Its massive bulk bears no relationship to All Souls and instead privileges—perhaps because of Shippen’s influence—its rapport with the entrance to Brasenose College. Furthermore, the elimination of a porticoed basement prevents that “Walk or place of Conference in which Students of all sorts might confer together,” which had been envisioned since the time of Laud.130

The important role of Hawksmoor’s designs in the conception of the library’s architecture as it was finally realized by James Gibbs in the structure termed today “the Radcliffe Camera,” has been thoroughly discussed in the literature. 131 By contrast, the full complexity of the linear, albeit rocky, course of Hawksmoor’s plans for Oxford has been overlooked. Isolated from the world in which they were conceived, discussed,

6.35 Nicholas Hawksmoor, West side of the north quadrangle of All Souls College, c. 1733–1735, with the Radcliffe Camera (James Gibbs, 1737–1749) behind.

6.36 James Gibbs, Radcliffe Camera, 1737–1749.