harvey miller publishers stained glass before 1700 in the Colle C tions of the los a ngeles County Museu M of a rt and the J. Paul g etty Museu M corpus vitrearum united states of america

l os a ngeles c ounty m useum of a rt

was receptive to the addition of a warm tint that could both define subject matter and enhance the abstract nature of the design. Two small-scale images of Apostles of about 1460–70 in the Getty Museum are composed entirely of uncolored glass (JPGM 19 and 20: 2003.45.1 and 2), and stand on a ground of solid yellow. Bands of yellow outline their haloes and color the borders of their cloaks, buttons, staffs, belts, and the pages of their books. The heraldic panel showing the arms of the Alsatian goldsmith Hans Ludwig Hanelutz and his wife, dated 1582, continues the same use of flat areas of uniform silver stain to articulate the pictorial elements (LACMA 28: 45.21.41). Silver stain, however, can be much more freely applied, mixing several shades and intensities of applications. The roundel of the Archangel Michael Vanquishing the Devil (JPGM 55: 2003.73) of about 1520 shows more loosely applied washes and two distinct shades of silver stain mixed with the russet tone produced by sanguine. Introduced in the early fifteenth century, sanguine contains iron that tints the glass from pink to red-orange when fired. The application in this panel spills over edges and is particularly variable in the landscape.

Enamel was a technique that grew in popularity in the seventeenth century. It became a staple for Swiss production, almost entirely displacing the use of pot-metal glass (glass colored in its mass while

7. Heraldic Panel: Arms of Hanelutz and Kölbin, detail of shield, reverse, showing enamel paint, Strasburg, 1582. LACMA 28: 45.21.41. Photo: author

in the molten state) for some panels.9 Enamels are intensely colored ground-up glasses suspended in a liquid medium that are painted onto the base glass, which is often a light tint for best effect. The enamels are then fused onto the glass surface and thus frequently appear on the reverse of the glass as a slightly raised layer, as visible in the blue enamel surrounding the image of a cock in the arms of Hanelutz of 1582 (fig. 7; LACMA 28: 45.21.41). While they are not opaque, they lack the transparency of pot-metal sheet glass. As they fire at lower temperatures than opaque vitreous paints, they are liable to flaking, as seen in the border around the image of Esther Accusing Haman at her Banquet (LACMA 41: 45.21.52) of 1620. After the segments of glass are painted, they are fired in a kiln to approximately 1250° F. As the glassflux softens and the surface of the glass sheet becomes tacky, they fuse to create a permanent bond. In the absence of instruments to measure temperature, the craftspersons responsible for loading and firing the kiln developed a remarkable sensitivity. Theophilus, for example, records the possibility of leaving pots of molten glass in the kiln for different lengths of time to produce different colors. Given that the process was time consuming and demanded close supervision, the producers of stained glass wanted to maximize kiln usage.10 Because of this need, a number of panels, even from different windows, could be stacked in the kiln and fired at the same time. A brilliantly executed heraldic panel with the Arms of Ebra (JPGM 28: 2003.57) is associated with the Hirschvogel workshop and shows sorting marks in the form of a number 6 scratched into the reverse side of each segment of the glass. The sorting marks were used to identify and assemble panels after a multi-panel firing. The artisans in the Hirschvogel shop were trained specialists who could produce windows on the basis of a designer’s model, often including the selection of colors.11

A Tracery Light: Angel with Arms of Anne of Brittany (fig. 8; LACMA 12: 45.21.14a), dated 1490–1500, shows sorting marks in the form of an irregular circle with a slash, while a Swiss panel of 1614 showing the Beheading of John the Baptist (LACMA 38: 47.19.3) has sorting marks in the form of a Z.

The fired sections are then joined by malleable lead elements called cames. Medieval cames were cast in molds. Molten lead was poured into a heated mold and planed to shape after cooling, creating a product that has, in some instances, functioned to the present day. By the end of the sixteenth century, almost all lead-came was milled, which took less time than casting, but yielded a thinner, less substantial came.

8. Tracery Light: Angel with Arms of Anne of Brittany, detail, reverse, showing sorting marks, Brittany (?), France, c.1490–1500. LACMA 12: 45.21.14. Photo: author

9. Visitation, detail of original leads, east window, Church of Maria am Wasser, Leoben, Austria, 1420–32. LACMA 9: 45.21.1. Photo: author

Given the displacement of panels when they enter an art market, and the desire of the seller to present a marketable object, restorers invariably releaded panels. Medieval leads often survive because a panel shows an unusual construction, such as the inserted chef d’oeuvre, mentioned above. Large panels with medieval leads are exceedingly rare. Thus, it is a significant discovery to find the Visitation (fig. 9; LACMA 9: 45.21.1) from Leoben, Austria, dated about 1425, retaining not only almost all its glass intact, but most of its leading. The came is slightly rounded on both sides and thinner in width than what was used for later releading of many panels in the collection. The caulk that was applied in the early twentieth century has

deteriorated, allowing views of the vertical interior – the heart of the came which does not show milling marks that are the result of extrusion from a mill. The grozed edges of the early fifteenth-century glass are also visible.

Depictions of Patrons

The development of stained glass as a major art form in the Middle Ages was dependent on the needs of a powerful client, the Church, and went hand in hand with the evolution of architectural forms that allowed for ever larger openings in the walls, producing awe-inspiring walls of colored light. As scholars began to probe the shifts in Gothic innovation, specialists in stained glass, such as Louis Grodecki and Jean Lafond, led pioneering work describing the reciprocity of building and window design.12 Intensity of color and proportions of uncolored and pot-metal glass were connected to the goals of effective display.13

The earliest works in these collections are two largely composite panels in the J. Paul Getty Museum. The first is dated about 1210–25 with some later additions (JPGM 1: 2003.27). It is an assemblage of fragments positioned to depict figures gathered about a table. The segment of yellow garment that dominates the right side of the panel exemplifies Theophilus’ descriptions of three primary applications of paint; first a light wash, followed by a medium to strengthen the shadow and finally the opaque line to establish contour.14 Likewise, the bold and schematic facial features are achieved with parallel curves making the contours of the eyes and lids, clumps of hair forming a cap, and repetitive linear profiles. With some inclusion of uncolored glass, the panel approximates the harmonies of windows of this time, a balance in hue and value among the saturated colors of the pot-metal glass. The deep reds and blues used as a backdrop often create a rich foil for the figures and details in narrative scenes. A Seraph, also from France, dates to almost a century later (JPGM 2: 2003.28). It shows the color harmony of red against blue pervasive of the locale and time. The facial features are more subtle, presenting a placid, classically frontal pose, evenly balanced, with the hair falling in calm waves on either side of the head.

The commissioners of these ensembles, some of the most labor- and materials-intensive works of art of their time, saw themselves as contributing to an eternal enterprise. In these edifices, images of God, the saints, and pious narratives populated the translucent walls. The makers expressed lofty thoughts concerning transcendent light transformed by multi-hued glass, but they also cherished more personal and

mundane goals.15 Since the first great programs of stained glass in the twelfth century, patrons situated themselves, in image and in name, in the windows.

Representations of donors extended across all media: wall painting, manuscripts, sculpture, and even set within the iconography of a reliquary. Inscriptions and heraldic displays enabled the viewer to recognize the identity of the donor. One of the most common pictorial formats was as diminutive figures at the foot of a saintly patron. In the Getty Collection’s renowned manuscript of The Life of the Blessed Hedwig, the patron and descendent of Hedwig, Ludwig I of Legnitz, together with his wife, Agnes of Glogau, kneel on either side of St. Hedwig of Silesia (fig. 10; JPGM: Ms. Ludwig XI 7, fol. 12v).16 Donors were alternatively shown, in glass as in illuminated manuscripts, kneeling before altars or desks with open prayer books as we see later in the panel of the Premonstratensian Canon of Berkheim (JPGM 46: 2003.66), discussed below.

Donor figures were therefore as much a petition as an advertisement. They called upon the viewer to remember and offer prayers and good works for the benefit of the soul of the person represented. Pious actions and good works included the seven Corporal Works of Mercy, such as visiting the sick or sheltering the homeless, a concept discussed later in this essay. Other good works included the giving of alms for the construction of a church, the fulfillment of a pilgrimage, saying prescribed prayers during a sequence of times or at visits to shrines, especially on the feast day of the saint.

Naturally, all in the community of the faithful were enjoined to pray. In a hierarchical society, however, it should not be surprising that some individuals would be seen as more powerful intercessors before the Divine Judge. Chief among these was the Virgin Mary, the mother of God, invoked as humanity’s most eloquent petitioner. Her power to remind Christ of his link to humanity was reinforced by images of Mary as a mother, cradling an infant who addressed her with loving gestures. For example, the Virgin and Child (JPGM 4: 2003.32) from the Augustinian Abbey of Klosterneuburg, Austria, dated about 1335, shows the Divine Infant playing with his mother’s veil and chucking her under her chin, a sign of intimacy in medieval times. We see the same depiction of human interaction a century later in the roundel showing the Virgin and Child Crowned with the Sun (JPGM 38: 2003.49) wherein the Christ Child smiles and turns to engage his mother while reaching for her breast.

It was this context that conditioned the window showing a Kneeling Donor (JPGM 16: 2003.41) from Brittany, dated between 1440 and 1450. A banderole curves around the figure carrying the Latin text: O mater dey memento mey (O Mother of God, remember me). Beyond honoring the Virgin, the panel reflects the practice of pious laity of reading books of hours, which emulated the clerical recitation of prayers at fixed times each day and intermingled selections from the psalms, hymns, and petitions to the saints. 17 The simplicity of the composition and summary 11.

Thurn and Schultheiss dated 1559 (Schaffhausen, Museum zu Allerheiligen, Inv. 51851, CV Switzerland, RN5, Hasler 2010, pp. 197–99, no. 15) shows similar shields with mantling. The panel employs an unusually wide gamut of techniques, and in the shield, the use of blue enamel instead of flashed and abraded glass for the tinctures of or and azure. The delineation of the lions’ manes shows strong similarities to the rich brush and stick work, especially evident in the wildmen in the Los Angeles panel. A later panel, dated 1570, also bears the artist’s monogram (Schaffhausen, Museum zu Allerheiligen, Inv. 54655, CV Switzerland, RN5, Hasler 2010, p. 205, no. 20). The shield with a black wheel on a gold ground and disposition of helm and mantling is close to that of the Los Angeles piece. A marriage panel of Von Fulach and Konstanzer ascribed to Lang was executed about 1560 and evidences some of the looser brushwork and intricate damascene on the shields that is so striking in the Müller coat of arms (Schaffhausen, private collection, CV Switzerland, RN5, Hasler 2010, p. 327, no. 126).

Date: The date is 1547 is written on the preparatory drawing.

Bibliography

unpublished sources : CW Post Hearst Archives; Hearst Inventory 1943, no. 246; Hayward Report 1978: Sibyll Kummer-Rothenhäusler, notes CV USA; Susan Atherly, 1985 draft of entry, CV USA; Rolf Hasler, CV Switzerland, 2019, communication to author of discovery of design of 1547 and identification of the workshop of Hieronymus Lang, Schaffhausen; Daniel Hess, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, CV, Germany, 2020, consultation with author.

published sources : Loewenthal sale, Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus 1931, p. 36, no. 169, pl. 37; LACMA Quarterly 1945, pp. 5, 10; Normile 1946, pp. 43–44; Hayward in CV USA Checklist III, p. 68; CV Switzerland, RN2, CV Switzerland, RN2, Hasler 2002, pp. 200–03; CV Switzerland, RN5, Hasler 2010, pp. 104–05, fig. 79; Daniel Parello, “Wappenscheibe des Abtes Caspar Müller von Hieronymus Lang d. Ä.”, in Der Schatz der Mönche [exh. cat. Freiburger Augustinermuseum] Guido Linke, ed., Freiburg im Breisgau, 2020, pp. 48–50.

20. Heraldic Panel with Double Arms of the Abbey of St. Blasien, Schwarzwald, and Abbot Caspar I Müller (Caspar I Molitor)

Rectangle: 28.8 × 30.0 cm (11À × 12ħ in.)

Accession no. 45.21.21, William Randolph Hearst Collection

Ill. nos. LACMA 20, 20/figs. 1–3

Inscription: Caspar von gottes gnaden Apte des gottehaus Sant blasï uff dem schwartz wald 1547 (Caspar by the grace of God, Abbot of the Monastery of St. Blasien in the Black Forest, 1547).

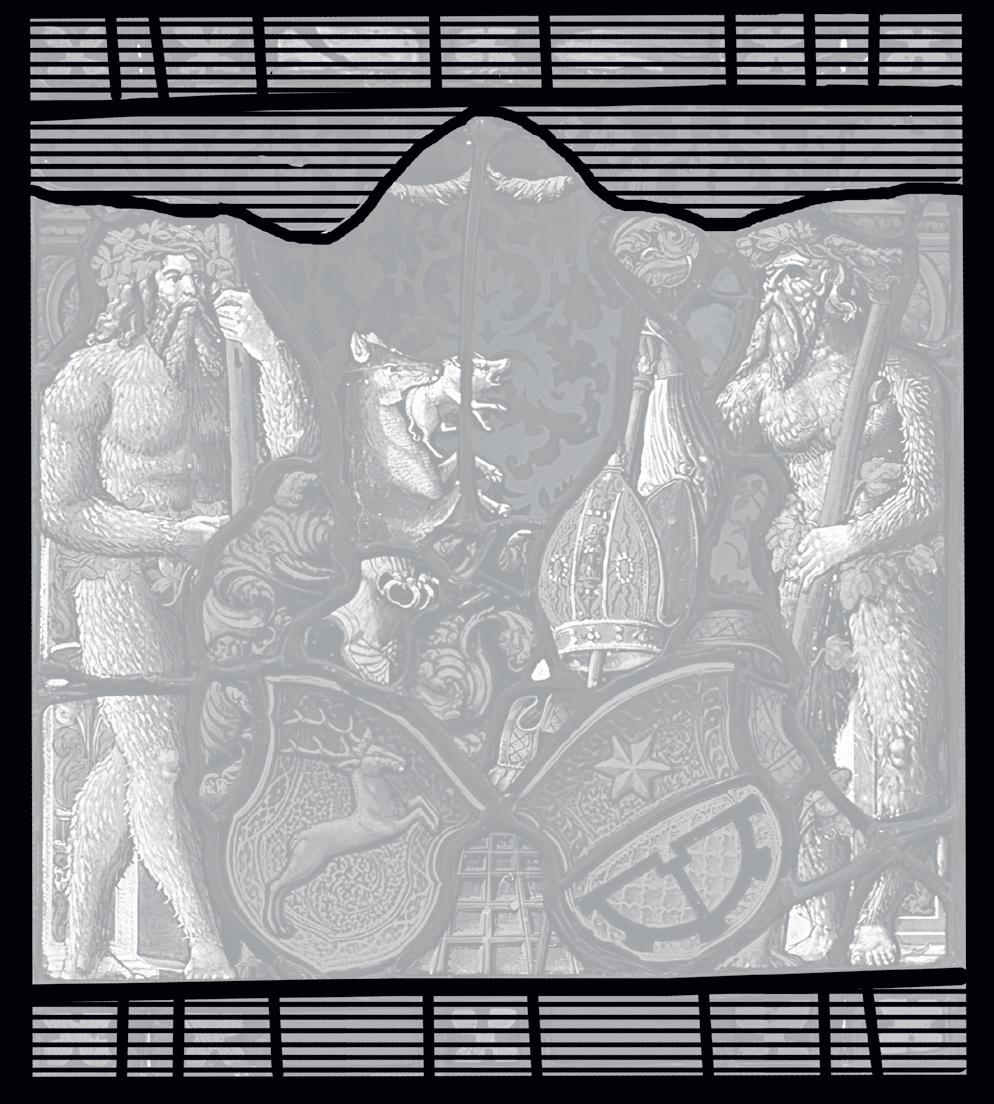

Description: To the left and right, taking up the entire height of the panel stand two wildmen. Wreaths of leaves encircle their heads and waists and they hold long staffs in their arms. In the center of the panel two coats of arm rest on a gridded floor; behind them is a damascene cloth.

Arms: LEFT: Azure a stag salient or (Abbey of St. Blasien); CREST: On a barred helm to sinister a demi-wolf rampant holding in its maw a wild piglet all proper; mantling of the colors.

RIGHT: Per fess in chief a mullet of six points or in base or a demi-mill iron sable (Abbot Caspar I Müller); CREST : An abbot’s crosier and miter with stole floating all proper; SUPPORTERS : Two wildmen wreathed about the head and middle with oak leaves and holding in their hands a tree trunk all proper.

Condition: The heraldic panel that forms the center is in excellent condition. The pot-metal borders above and below are a mixture of stopgap and modern glasses; they replace dedicatory inscriptions and decorative work that would have originally framed the central panel. Although blank in the drawing, the space at the upper portion of the design would probably have contained a figural element, such as the Annunciation, which appeared in later works commissioned by Müller (see below). The modern damascene segments above the capitals to the left and right are replacements for the Renaissance architecture that is depicted in the drawing. The design also attests to the original plan of a ribbon border with inscription.

Iconography : The animals on the shield and crest relate to the abbey’s patron saint, Blaise (Blasius), a bishop of the fourth century from Sebastea, Armenia. The cult of St. Blaise, however, was well established in Western Europe and was particularly intense in Germany (Hermann Jacobs, “Die Anfänge der Blasiusverehrung in Deutschland,” in St. Blasien, Festschrift aus Anlass des 200 jahrigen Bestehens d. Kloster und Pfarrkirche , Heinrich Heidigger and Hugo Ott, eds., Munich, 1983, pp. 27–32; Herder Lexikon, vol. 5, pp. 416–19; Réau, III:1, pp. 227–33). In two of the saint’s most characteristic legends, he shelters animals and also enables their consumption. The stag on the shield recalls the

story that he was discovered by hunters living peacefully in the deep forest surrounded by wild animals, some of whom he had healed. The wolf carrying the piglet in its maw refers to the miracle performed by St. Blaise from prison for an impoverished woman. Her only pig had been a carried away by a wolf and Blaise caused the animal to bring it back. This story entered the late thirteenth-century collection, the Golden Legend (Golden Legend, vol. 1, p. 152). Even earlier, this event appears in monumental form in the twelfth-century frescos of the apse of the monastic church of Berzé-la-Ville (Herder Lexikon, vol. 5, p. 419, fig. 3).

The panel commemorates Abbot Caspar I Müller who was also known as Müller von Schöneck, thus the use of the mill wheel in his coat of arms. The abbot’s seal of 1541 (LACMA 20/fig. 2) shows the figure of an abbot with a radiating nimbus, surely St. Benedict, under a Renaissance architectural niche. The inscription is in classical capitals, instead of the Gothic miniscule used by previous abbots. The two shields showing the stag and demi-mill and mullet appear below, but without the crests. Another seal of 1548, in a circular form, places the abbot’s miter and crosier between the two shields (Konrad Sutter, “Siegel und Wappen des Benediktinerabtei St. Blasien,” in Heidigger and Ott 1983, pp. 96–110, fig. 17:9, seal of 1541; fig. 18:10, seal of 1548).

Although the site apparently hosted some monastic settlement, the first abbot recorded is Werner I, who received foundation privileges in 1065 from the Emperor Henry IV. The abbey apparently grew substantially, was associated with Cluniac reforms, and in less than a century had founded five priories, including the Swiss abbey of Muri in 1082 (for Muri see Introduction to this volume; for the medieval history of the St. Blasien see Hugo Ott, Studien zur Geschichte des Klosters St. Blasien im hohen und späten Mittelalter , Stuttgart, 1963). Müller’s administration (1541–71) was a period of growth, which historians attribute in a large part to his acumen. In 1549 the abbot successfully resisted the efforts of the bishop of Constance to bring the abbey into the Swabian Circle. Müller is credited with the education of at least eleven monks who became abbots of other Benedictine abbeys. In 1557, he finished the first complete history of St. Blasien, entitled liber originum, which is preserved in Karlsruhe and bears the same double arms as the Los Angeles panel. A printed version of the text of the manuscript entitled CASPAR , MOLITOR , Stiftungsbuch “Liber Originum 1555/57” was published in the mid-nineteenth century (Franz Joseph Mone, Quellensammlung der badischen Landesgeschichte, II, Karlsruhe, 1854, pp. 56–80). The abbey was dissolved in 1806 during the secularization of Germany. Its massive church, dating from the late eighteenth century, now serves a parish and the monastic buildings house a prestigious Jesuit preparatory school.

Wildmen were popular motifs in late-medieval and Renaissance art, depicted sporadically as a heraldic device but far more commonly as supporters. One of the first examples may possibly be the seal of Bergen op Zoom of 1374 with three supporters, but the tradition became common by

LACMA 20/fig. 2. Caspar Müller’s Seal of 1541, after Konrad Sutter, “Siegel und Wappen des Benediktinerabtei St. Blasien”

the end of the fifteenth century (Richard Bernheimer, Wild Men in the Middle Ages, New York, 1979, pp. 179–80). The wildman symbol has multiple complex associations, stressing both the wildman’s supernatural strength and his awareness of nature and its primeval truths (Timothy Husband, The Wild Man [exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art], New York, 1980; Hayden White, “The Forms of Wildness: An Archeology of an Idea,” in The Wild Man Within, Edward Dudley and Maximillian E. Novak, eds., Pittsburgh, 1972, pp. 3–30). In the case of the Abbey of St. Blasien, a confluence of meanings can be posited. The monastery’s location in the Black Forest and the monastic model of rejecting society in favor of solitude in the wilderness resonates with the habitat and behavior of the wildman. These wildmen are well behaved, and wear leafy vines over their loins. Their dignity suggests a connection to the renewed interest in hirsute saints around 1500 in Germany. Depictions of John Chrysostom, crawling naked on his knees as penance, and St. Onuphrius living off figs and clothed only in thick body hair appear in works of Hans Schäufelein, Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach, and Sebald Beham (Husband 1980, pp. 95–99 and 107–09.) In addition, Onuphrius, who, during his early years, was nourished miraculously by a white deer and fed bread by a raven seems to reinforce the connection between the inherently virtuous forest creatures and the ability of human wildmen to serve a higher spiritual order (Herder Lexikon, vol. 8, pp. 83–88; Réau, III:2, pp. 1007–10). Accordingly, their role lends itself to the patron saint Blaise, who demonstrated miraculous healing powers to the forest animals who recognized his virtues.

LACMA 20/fig. 3. Caspar Stillhart and Christoph Bocksdorfer, Constance, Heraldic Panel of Abbot Caspar I Müller, 1544. Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, MM905

Abbot Caspar Müller had his arms set in glass by many other glass painters. In 1544, Caspar Stillhart and Christoph Bocksdorfer of Constance painted the first glazed representation of the abbot’s arms with the formula of wildmen supporters and crests of wolf and piglet and miter and crosier (LACMA 20/fig. 3. See above under related works). The heraldic supporters are again wildmen but the abbot’s miter has the image of the Annunciation instead of an abbot. The Annunciation was apparently a recurring theme since in 1563, Müller commissioned a panel from the Basel master Hans Jorg Riecher (or Reiher), who later executed fifteen panels for Basel’s Schützenhaus (Giesicke 1991). It shows Müller’s arms quartered with those of the abbey and the Annunciation, with Gabriel to the left and Mary to the right, in the spandrels of the architectural frame (private collection H. R. Geigy-Koechlin, Basel: Ganz 1966, p. 37, fig. 27). Quartered arms are also used in 1569 in the panel designed by Hans Hug Kluber, a Basel glass painter. Over a three-dimensional Renaissance arch, we see the Adoration of the Magi. The inscription, like that of the arms of 1663, is in Latin (Ganz 1966, p. 59, fig. 50). These quartered arms

can be compared to the format used by a later abbot, Martin Meister, who gave a panel in 1623 to Wettingen’s cloister showing his arms quartered with those of the St. Blasien. He used as supporters, saints James and Blaise, not wildmen (bay South IVa: Hoegger 2002, pp. 152, 353. ill.).

Müller also commissioned a window for the monastery of Muri in 1558 (South IV: CV Switzerland, RN2, Hasler 2002, pp. 92–95, 200–03, ill.). Three lights include in the center an image of St. Blaise seated with a stag at his feet. To the left, in a pyramid, are the arms of St. Blasien, Sellenbüren, and Austria; to the right the arms of St. Blasien and Müller. A panel (whose upper portion is probably restored) is dated 1557 and shows the same disposition at the base (London, Victoria & Albert Museum, Inv. C.91–1934; Rackham 1936, p. 92; CV Switzerland, RN2, Hasler 2002, pp. 202–03, fig. 49). One panel dated 1569, in all likelihood made for the monastery of Wettingen, shows two wildmen supporting arms and holding clubs with a miniature of a stag hunt above (formerly Schloss Lenzburg, Historical Museum of Canton Aargau, inv.no. K 256: Anderes and Hoegger 1988, p. 39).

Photographic Reference: 45.21.21.

LACMA 21. PORTRAIT OF ULRICH VON WÜRTTEMBERG

Southern Germany 1550

History of the Glass : The portrait is recorded as once belonging to the collection of the Comtesse de SaintMichel (unidentified) before being purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Vance Thompson, Hollywood. The roundel was leaded into a modern surround of colorless glass in a lattice pattern containing nineteenth-century works: a roundel of arms containing a demi-bear and six panels showing the Dance of Death after Hans Holbein the Younger. The Thompsons loaned the panels to museum, recorded on November 4, 1918; they were given outright and accessioned in 1924.

Color and Technique: Two shades of vitreous paint and one tone of silver-stain have been applied to uncolored glass. The roundel also shows transparent enamels applied to the reverse, green for the table top and one of the plumes in the cap and purple for the slashed sleeves.

Style : The panel is executed in a manner that recalls engraving or enamel work. A dense black wash, picked out with quill work, is used for the lower sleeves and the chest.

The glass painter is not using a painterly mode of applying color or line, rather, the strokes are very small and tightly controlled. An example is the treatment of the fur of the collar. Whether a trace intensifying the value at the edges, or quill work removing the matte from the center, the strokes are of equal size and aligned in uniform rows. Each detail of the slashes in the sleeves is executed in the same way. A uniform medium wash in the center is accented by a trace squiggle; a quill-work line then outlines the boundaries of the wash. Silver-stain on the back of the panel transforms the quill work into a yellow line. The color is subdued, supporting the conservative style of painting. The image is similar to ancient coins, whose forms inspired Renaissance artists in their quest to revive the antique.

The roundel presents the same characteristic features found in the woodcut portrait of Ulrich executed by Hans Brosamer about 1545 (LACMA 21/fig. 1; London, British Museum, 82367001). The three-quarter pose shows a longish, broad nose, a sloping mustache, and a trimmed beard. His dress shows a similar tilted soft hat bedecked with feathers, a fur collar, ruffled neck of the shirt, and multiple chains across the chest. Both print and roundel include inscriptions and heraldic devices. See also the anonymous oil portrait of Ulrich (Ulrich von Württemberg, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Volker Press, “Herzog Ulrich (1498–1550),” in Robert Uhland, ed., 900 Jahre Haus Württemberg, Stuttgart, 1984, p. 12, ill.)

Date: The year 1550 is part of the inscription on the roundel.

Bibliography

unpublished sources : Curatorial files concerning the Thompson gift; Hayward Report 1978; Freiburg Corpus Vitrearum, 2019–20, consultation and research.

published sources : Museum Bulletin I no. 4, July 1920, p. 31, ill; Husband in CV USA Checklist IV, p. 55.

21. Portrait of Ulrich von Württemberg

Circle: 13 cm (5ħ in.)

Accession no. 18.7.2g (formerly A.880.18.2a), gift of Mr. and Mrs. Vance Thompson

Ill. nos. 21, 21/figs. 1–2

Inscription: Ulrich der . 3. Herzog Zu Württemberg. Sarb [rect. Starb] Sellig . Anno . 1550 (Ulrich the third, Duke of Württemberg died blessed/in peace, the year 1550)

Description: A richly dressed nobleman is portrayed in a half-length portrait. His left hand rests on the pommel of a sword while his right appears to hold a letter. An inscription encircles the panel.

Arms: Quarterly; 1 or three antlers fesswise sable (County/ Duchy of Württemberg); 2 lozengy bendy sable and argent

(Duchy of Teck, acquired 1381); 3 argent imperial standard with imperial eagle displayed (Holy Roman Empire); 4 gules two fish addorsed proper or (Mömmpelgard, acquired 1397) (Ulrich von Württemberg).

Hans Baldung Grien designed a panel showing the coat of arms for Ulrich von Württemberg, executed in 1520 using traditional pot-metal and uncolored glass (LACMA 21/fig. 2). The shield shows the same quartering with four devices. It also shows two barred helms facing each other, each carrying a different device. The hunting horn, dexter, relates to the antlers of the first quarter, as does the stag hunt in the upper part of the frame (noted as Basel, Private Collection, Schmitz 1913, p. 143, fig. 205; present location unknown).

Condition: A shatter crack is edge-mended. There is a minor chip and some flaking along the edge.

Iconography: Ulrich von Württemberg’s reign was lengthy (1498–1550), bridging periods of both political and religious upheaval; he numbers among the most important of the dukes of Württemberg (Press 1984, pp. 110–35). His early years of extravagant expenditures led to a popular uprising called armer Konrad (poor Conrad). Although the revolt

was suppressed, it led towards the growth of constitutional liberties for the territory. In the treaty of Tübingen of 1514, the people agreed to pay the duke’s debts in exchange for political concessions. Ulrich had unfortunately made enemies of both the Swabian League and William IV, Duke of Bavaria, because of his ill treatment of the Bavarian princess Sabina, who had become Ulrich’s wife. Württemberg was invaded and Ulrich expelled. The Duchy was then sold to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V who gave it to his brother, Ferdinand I of Germany. Ulrich’s coat of arms after a design by Hans Baldung Grien (LACMA 21/fig. 2) was made during this era. The Reformation in the German territories soon provided a restructured system of political allegiances. Ulrich embraced the Lutheran cause in 1523, strategically allying himself with the peasant underclass, and managed a short-lived reconquest of his territories. Ultimately, aided by Philip, Landgrave of Hesse and other Reformed princes, he defeated Ferdinand at the battle of Laufen in 1535. The treaty of Kadan recognized him a duke, but under Austrian authority. Nonetheless, Ulrich instigated a vigorous campaign of support for the Reform by confiscating monasteries and endowing Protestant churches and schools

36. Adoration of the Magi

Rectangle: 35.6 × 22.9 cm (14 × 9 in.)

Accession no. 45.21.35, William Randolph Hearst Collection

Ill. nos. LACMA 36, 36/1

Inscription: Caspar Gallatÿ Ritter Kö[niglich]/ Maaÿ [aestät]

Zu Franckrich v[n]d Nāw[arra]/ Besteltder Kreigs oberster 1612 (Caspar Gallati Knight; His Royal Majesty of France and Navarre appointed [him] Field Colonel 1612).

Kaspar Gallati (1535/37 Näfels – 1619 Tours) was one of the most distinguished officers of his era. He served under the French Catholic kings, Charles IX, Henry III, Henry IV, and Louis XIII, during numerous conflicts, particularly against the Huguenots in France and the Spanish in The Lowlands (https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/023709/2007–06-29; Albert Müller, “Kaspar Gallati,” in Grosse Glarner, 26 Lebensbilder aus fünf Jahrhunderten, Fritz Stucki and Hans Thürer, eds., Glarus, 1986, pp. 47–61).

Description : In the center, the seated Virgin holds the naked Christ Child on her lap. The eldest king, with a white beard, kneels to the left. Joseph is in the background before a stable with animals. The young king from Africa is on the right and the middle-aged king from the Middle East to the left. The scene is set within an architectural frame for ornamented columns. Below is an elaborate cartouche with the inscription.

Condition : The panel is virtually intact except for tiny stopgap segments inserted at the top of the panel and near the inscription plate. Mending leads in the inscription plate were removed after Hearst’s purchase. A sliver of new glass has been inserted to replace the missing top of the R in Ritter and the adjacent upper border of the inscription. The figural scene does suffer from weathering that has left speckles on the glass. Heavy mending leads diminish the clarity of the lower section of the figural panel.

Iconography: At the top of the panel, a triangular shaped aureole surrounding the star breaks through a wreath of clouds to illuminate the scene of the Adoration of the Magi. The lean-to frame of the stable is set against massive architecture. Indeed, the placing of the stable within a huge edifice recalls the setting of modest shrines, such as the Portiuncula Chapel in Assisi. The site of St. Francis’ death in 1226, the chapel was enveloped by the magnificent baroque structure of the church of St. Mary of the Angels, completed in 1578. This image may also evoke an actual Nativity crèche set within a church. The tradition of the crèche began in the early thirteenth century when St. Francis set up a manger in the town of Gubbio to “make memorial of that Child who was born in Bethlehem, and in some sort behold with bodily eyes His infant hardships; how He lay in a manger on the hay, with the ox and the ass standing by” (Thomas of Celano, First Life, ch. 30, 84). The event is dated to 1223, three years

before the saint’s death (Bonaventure, Major Life, ch. 10, no. 7).

Mary has a yellow nimbus, and wears a white wimple. A blue mantle covers her white robe. The Child has a cantedsquare nimbus. At the left kneels the eldest king, Melchior, in a yellow robe and red cloak. Behind him stands the middleaged king, Balthasar, in a purple turban, gold crown, green robe, and purple cloak. Joseph, in a green robe and purple mantle, stands behind the Madonna and Child. In the background are a gray ass and a brown ox. The ass ignores the message of Christ and turns to eat, while the ox directs a respectful gaze at the Christ Child. Although absent from the Gospel accounts of Christ’s birth, the ox and ass appeared early in Nativity depictions, such as the sixth-century image on the lid of a wooden box for pilgrim’s souvenirs from the Holy Land (Museo Sacro, Vatican City: see discussion in LACMA 18: 18.7.1g, Adoration of the Shepherds).

Kaspar Gallati commissioned the panel seven years before his death at the age of 84 (or 82). Given his long service to the kings of France, the selection of royalty may have had multiple meanings. Caspar, his name saint, stands clearly silhouetted to the right of the seated Virgin. Since the fifteenth century, he was often portrayed as African. Here, unlike the portrayal in the Lucerne panel of Caspar Pfyffer (LACMA 56: 45.21.42), he is in European military dress, and is differentiated only by his dark skin. This choice may have been an allusion to the donor’s own occupation of soldier. Caspar’s attire includes purple and green armor, a green cloak, a white shirt, and green boots. Although traditions differ, Caspar was most often seen as the youngest of the three Magi who offered the infant the gift of frankincense, signifying the Child’s divinity (Kehrer 1908, p. 66; quoting Collectanea et flores, Basel, 1563, vol. 3, p. 649; Réau, II:2, pp. 236–55, which cites the tradition of a gift of gold; Herder Lexikon, 6, cols 97–98).

Photographic Reference: 45.21.35.

LACMA 37. CRUCIFIXION WITH THE ARMS OF MICHEL, VALLÉLIAN, AND VILLARD

Switzerland, canton of Fribourg 1612

History of the Glass: The panel was listed in the 1885 auction of a Mr. H., in Basel. It later appeared in the 1924 estate sale of James A. Garland, Boston, when it was purchased by William Randolph Hearst. Hearst donated the panel to the museum in 1943; it was accessioned in 1945.

Original Location: The status of the canton and city of Fribourg provides the context for the message and structure of this panel. At one time under the influence of Savoy, it gained independence as a Free Imperial City in 1478. In 1481, Fribourg joined the Swiss Confederation. Its government long remained under the control of a group of patrician families, who were instrumental in encouraging adherence to the old religion during the time of the Reformation. Fribourg is

on the edge of the divide between Catholic and Protestant Switzerland. During the Middle Ages, the influence of the church had been strong, with powerful abbeys founded by the Cistercians, Augustinians, and Franciscans. It became a center of Counter-Reformation activity and in 1580, aware of the Protestant schools founded at Basel, Lausanne, and Geneva, the government invited the celebrated Jesuit, Peter Canisius, to found the College of St. Michel for the education of the youth. Canisius died in Fribourg, November 21, 1597. Thus, in 1612, we see the context for so articulate a manifestation of Catholic piety and the social and religious ties among men promoted by Jesuit education.

Color and Technique: A bright intensity is achieved through the dominance of blue and violet. These are balanced by numerous touches of yellow and neutrals. The construction is quite sophisticated. The glass includes uncolored glass and pot-metal in the tints of violet, blue, and green used in the architectural frame. Flashed and abraded red appears in the central area of the architrave. Two shades of vitreous paint and two shades of silver-stain augment the complexity of the color scheme. Blue, green, and violet enamels are applied with unusual skill. Horizontal striations removing blue enamel add a sense of vivacity to the sky closest to the horizon (LACMA 37/1). The green in the triple mount in the shield and green devil with St. Theodule are achieved by silver-stain on the glass under the blue enamel. The eyes, horns, and testicles of the devil show through as yellow where the blue enamel has been omitted.

There is considerable modulation via back-painting. A cool neutral tone appears for darker areas, such as the cloaks and hair of the two donors, a lighter tone for the flesh of the figures, and a warmer tone for parts of the architecture below the apparition of the Holy Spirit and to the left of Gabriel in the Annunciation. Sanguine appears restricted to Christ’s hair and beard.

Style: The artist shows a sure hand in the depiction of the many components of the scenes. The grisaille matte is applied in a painterly fashion in many areas. In the robes of the Virgin and St. John, for example, over a layer of medium wash, shading washes blend with few hard edges. Trace is varied among thin and broader strokes. Removal of paint is similarly varied. In the garments of the Virgin, extremely small strokes indicate her robes’ soft contours and linear work suggests the sharper edges of her veil. John’s robe and exposed area of tunic show linear accents that suggest a surface sheen. The anatomical three-dimensionality of the devil is a testimony to the artist’s sophistication.

A comparison can be made with a panel showing the Allegory of the Conflict of the Soul commissioned by Peter Hans in 1610 (LACMA 37/fig. 1; Museum für Kunst und Geschichte, Fribourg, Inv. Nr. MAHF 2451; CV Switzerland, RN6, Bergmann 2014, pp. 566–67, no. 87; note, the man plowing is a stopgap). We find the same general proportion of central figural scene to architecture. The patron saints, in this case Peter and Barbara, stand on red bases against

light-colored pillars similar to those in the LACMA panel. A wide area below is dedicated to the inscription. On the left, Peter Hans, a member of the clergy, kneels in prayer, rosary beads in his hands, and his coat of arms is shown on the right. His stance is similar to the donors adoring Christ’s redemptive act in the Crucifixion. Beyond workshop similarity, common local conventions of painting and composition link the panels. The haloes of the saints in both panels are enhanced by radial striations. The subtle use of enamel colors may be the most striking common characteristic. Combining washes and stick work, the two artists achieve a remarkably engaging reciprocity among the figures and the landscape. Although not as complex as the clouds in the LACMA panel, the circular-shaped clouds at the height of the tree are an eye-catching element of the 1610 composition.

Date: The inscription gives the date of 1612.

Bibliography

unpublished sources : Hearst Inventory 1943, no. 265; Hayward Report 1978; Sibyll Kummer-Rothenhäusler, inspection before 1987 with notes identifying Fribourg, CV USA; Jane Hayward notes, CV USA; Rolf Hasler and Uta Bergmann, CV Switzerland, 2016–20, consultation and research on the donors for author; Leonardo Broillet, archivist of Fribourg, 2020, furnishing information to the author concerning the donors.

published sources : Catalog der Sammlung von Glasgemälden des Herrn von H., by Elie Wolf, Antiquary, Stadtcasino in Basel, 15 and 16 June 1885, n.p., no. 1; Garland sale, American Art Galleries 1924, no. 331, with the notation that the panel “needs restoration”; LACMA Quarterly 1945, pp. 5–10; Normile 1946, pp. 43–44; Hayward in CV USA Checklist III, p. 74 Switzerland, canton of Fribourg; CV Switzerland, RN6, Bergmann, 2014, pp. 111–12, fig. 78 in a discussion of varied representations of patronage.

37. Crucifixion with the Arms of Michel, Vallélian, and Villard

Rectangle: 43.5 × 34.9 cm (17ħ × 13ƒ in.)

Accession no. 45.21.40, William Randolph Hearst Collection Ill. nos. LACMA 37, 37/fig. 1.

Inscriptions : on titulus of cross: INRI (initials of Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews); on banner of donor to right: O DEUS PROPITIVS ESTO MICHI PECCATO RŸ (O God be well disposed to me concerning my sins); on banner of left donor: S. MERE DE DIEV ET S. I [. .]ANNES – MOŸ (Holy Mother of God and St. John [remember] me); around arms in center: JOANNES A WILLARIO CVRAVIT SIEN BVLENSIS (Jean du Villard of

Bulle; in lower cartouche on left: theodvlvs michael / 16 (Théodule Michel 16); in lower cartouche on right: piere walleian / 12. (Pierre Vallélian 12).

Description: A scene of the Crucifixion shows Mary to the left and John to the right; each of them behind a kneeling male figure. An elaborate architectural frame surrounds the scene. At its top, the Annunciation appears with the Virgin on the extreme left and Gabriel on the extreme right. Below them are patron saints standing on heavy architectural bases. The lowest level shows three heraldic shields, one in the center and one at each side. The cartouche behind them carries an inscription. Within the scene, banderoles also carry inscriptions.

Arms: LEFT: Azue on a mount vert a lamb passant argent in chief two stars of six points or (Michel); CENTER : Per fess in chief azure a fleur-de-lis or in base paly of five argent and azure (unidentified); RIGHT: Azure on a triple mount vert three rings triquetra argent a mallet or (Vallélian).

Condition : The panel is completely intact except for the restoration below Christ’s arm to the right of the cross. Small triangular stopgaps appear in the lintel just above the cross on the right and on the left next to the dove of the Holy Spirit.

Iconography: The panel presents a confessional statement by two male donors meditating at the foot of the cross. Each is addressing the images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. John that they see in their mind’s eye. Their prayers, made explicit by the inscriptions below, are uttered both in Latin, the official language of the Catholic Church, and in the French vernacular. The Crucifixion is portrayed vividly, set against a cloudy landscape of blue, purple, and yellow. In the center, Christ is flanked by images of the sun and moon. These are symbols common since at least Carolingian times, and they refer to the darkness during the Crucifixion: “Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over the whole earth, until the ninth hour” (Matthew 27: 45). The darkness is represented here by the purple clouds. Here we also see the idea that the celestial bodies stood as witnesses for all of creation, mourning the death of its Creator. At the base of the cross is a skull, a double reference that Golgotha “means ‘The Place of the Skull’” (Mark 15:22) and that it was also believed to be above Adam’s tomb. Adam’s burial directly below the Crucifixion associates Adam, whose actions caused harm to the human race, with Christ, the new Adam (I Corinthians 15), who brought eternal life. To the left stands the Virgin Mary, dressed in a white wimple and blue mantle. Her head is bowed and her hands are folded in prayer. On the right is St. John the Evangelist in a purple mantle and gold robe. Mary and John are both traditional figures at the foot of the cross.

Two donors, in small format, are both dressed in black cloaks over blue doublets, breeches, and hose and kneel in front of Mary and John. Théodule Michel was a citizen of Bulle, the major city of the district of Gruyère in western Switzerland. He exercised the profession of notary since 1612