Inner and Central Asian Art and Archaeology III

In Search of Cultural Identities in West and Central Asia

Edited by Henry P. COLBURN, Betty HENSELLEK and Judith A. LERNER

Edited by Henry P. COLBURN, Betty HENSELLEK and Judith A. LERNER

Edited by Henry P. COLBURN, Betty HENSELLEK and Judith A. LERNER

Produced under the aegis of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University by F G

Kim Benzel – Foreword p. 7

Tabula Gratulatoria p. 9

Judith A. Lerner, Betty Hensellek and Henry P. Colburn – “Prudence Oliver Harper: Curator and Scholar” p. 11

Judith A. Lerner and Henry P. Colburn – “Bibliography of Prudence Oliver Harper” p. 19

Matteo Compareti – “Textile Decorations in Sasanian Stucco Panels at Bandyan (Khorasan, Iran)” p. 27

Georgina Herrmann – “Bringing Order Out of Chaos: Connoisseurship as a Fundamental Tool” p. 47

Pieter Meyers – “Bronze Casting in the Near East and Surrounding Areas” p. 55

St John Simpson – “Sasanian Skeuomorphs: The Influence of Metalware on the Glass Industry” p. 71

K. Aslıhan Yener – “Silver for Justinian: Lead Isotope Analyses of Sixth- and Seventh-Century Silver Artifacts” p. 85

Sasanian and Sogdian Silver

Betty Hensellek – “The Many Lives of the Silver Saiga Rhyton in the Metropolitan Museum of Art” p. 99

Kate Masia-Radford – “Aquatic Imagery on Silverware Attributed to the Sasanian Period ” p. 115

Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani – “The Memory of the Sasanian Age in Islamic Iran” p. 141

Nicholas Sims-Williams and Bi Bo – “A Silver Vessel with a Sogdian Inscription from Chach” p. 187

Joan Aruz and Annie Caubet – “Central Anatolia and the Mediterranean: Art and the Materials of Interaction” p. 207

Henry P. Colburn – “On the Date and Cultural Context of Aurel Stein’s Gilgit Rhyton” p. 233

Anca Dan and Frantz Grenet – “Facing Dionysus at Silenus’ Banquet in Tokharistan: A Possible Echo of a Greco-Roman Mystic Circle on a Fourth–Fifth Century “Bactrian” Silver Bowl in The al-Sabah Collection (LNS 1560M)” p. 247

Judith A. Lerner – “Thoughts on a Reused Roman Seal with a Middle Persian Inscription” p. 275

Andrew Oliver – “Fishing among the Flowers on a Roman Silver Cup” p. 287

Holly Pittman – “Forerunners of Old Elamite Culture in Bronze Age Kerman ” p. 301

Karen S. Rubinson – “Once More Identity at Tillya Tepe: The Iron Artifacts from Burial 2” p. 333

History and Historiography

Carol Bier – “Professor Pope and Dr. Phyllis Ackerman: Carpets and the Study of Persian Textiles ” p. 341

Martha L. Carter – “Notes on the Creative Mind of Ardashir I ” p. 361

John E. Curtis and Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis – “A Statue from Hatra in the Basrah Museum” p. 383

Anne Dunn-Vaturi – “Marie Thérèse Dubalen and the Ancient Near Eastern Study Collection” p. 393

Rika Gyselen – “Yazd, une province de l’empire sassanide ” p. 399

Jens Kröger – “Revisiting the Ctesiphon Excavations of 1928–29 and How The Met’s Trustees Saved the Second Campaign in 1931–32” p. 407

Author Biographies p. 437

Matteo CoMpareti1

This article discusses four unique Sasanian stucco panels with Middle Persian inscriptions excavated at the site of Bandiān, in Khorasan, Iran. Special attention is dedicated to garments, accessories, and textile decorations of the figures represented in the stucco panels. Iranian scholars have published excavation reports and detailed articles; however, a comprehensive publication of the site has not yet been written. Several details of the imagery in the stucco panels could help identify the main figures and their possible association with the patrons of the site who are mentioned in some of the Middle Persian inscriptions.

Despite the great interest in Sasanian art and culture, archaeologically attested sites securely attributed to this pre-Islamic Persian dynasty are not very numerous. The same could be said for Sasanian artifacts. As Prudence Harper stated in one of her informative studies, only six toreutic (that is, embossed or chased metal) objects have been found during controlled excavations and can be safely considered genuine Sasanian products (Harper 2000: 47–48). Throughout her very productive career, Harper has published a great amount of preIslamic metalwork, always giving convincing arguments to distinguish Sasanian artifacts from those of Central Asian or Islamic origin. Despite her interest in toreutics, she has not neglected other aspects of Sasanian art, as she demonstrated in her book In Search of a Cultural Identity: Monuments and Artifacts of the Sasanian Near East, 3rd to 7th Century A.D. (2006). Thus, for this Festschrift, I have opted for a subject that does not concern only Sasanian toreutics. A recent visit to Bandiān, in the Dargaz region of northern Khorasan Province, on the border between present-day Iran and Turkmenistan (Fig. 1), was an opportunity to observe in detail the fragmentary stuccoes that embellish the main room of this unique archaeological site.

Inner and Central Asian Art and Archaeology 3 27–46

Bandiān was discovered in 1990 by local farmers during agricultural work and has been scientifically excavated under the direction of Mehdi Rahbar since 1994. Its main columned room, embellished with stucco decorations, revealed five short Middle Persian inscriptions that could date the space to the fifth century CE.

Iranian archaeologists investigated an extended area around the stuccoes now in the museum (Fig. 2, Tepe A) and soon realized that the entire site was probably a large complex. An adjacent construction was identified as a dakhma, or Zoroastrian funerary tower for “air burials” (Fig. 2, Tepe B), and another building was probably a palace (Tepe C, not shown) (Rahbar 1998, 2004, and 2008). Many ideas expressed by Rahbar about the chronology and function of Bandiān have been rejected on philological grounds by Philippe Gignoux (2008); however, Rahbar restated his ideas with more convincing archaeological evidence following this criticism (2010–11). Although a comprehensive publication does not yet exist, some scholars have accepted Rahbar’s general reconstruction of the site and his chronology, alongside Gignoux’s reading of the Middle Persian inscriptions, despite Gignoux’s concern about philological and archaeological inconsistencies (Callieri 2014: 93–8, 118–25; Cereti 2019: 155–56). Samra Azarnouche has published the most recent study on Bandiān stuccoes along with some fresh interpretations on the scenes represented there (Azarnouche 2022).

The stucco panels at Bandiān depict men and possibly women in unique postures that are not found in either Sasanian monumental art (mainly rock reliefs) or small artifacts. As Pierfrancesco Callieri has already observed (Callieri 2014: 125), the only exception may be the Ṭāq-e Bostān hunting reliefs, which, in any case, represent an anomaly in Sasanian art (Compareti 2019b). Sasanian decorative stucco production has received great attention from scholars—in particular, from Jens Kröger (Kröger 1982; 2005; 2006; 2019; and in this volume).

In this paper, presented to Prudence Harper as a token of gratitude for her immense and generous work in the field of Sasanian studies, I consider the textiles represented in the stucco panels at Bandiān in order to shed some light on this unique monument.

When I visited Bandiān in mid-August 2017, a large pavilion, called the Site Museum of Bandiān in Dargaz, had been erected around the archaeological site. Only the dakhma and the structure considered to be a palace at Tepe C were excluded, although the former had received a roof (Fig. 2). The site’s Cultural Heritage Office is a few meters from the site where archaeologists continue their research. The Iranian archaeologists working there were extremely pleased to meet foreign colleagues and introduce the site according to Mehdi Rahbar’s ideas and reconstructions. A wooden walkway facilitated the visit to Tepe A, which is completely illuminated with artificial light inside the pavilion (Fig. 3).

There, the figured stucco scenes that survive are only on the lower part of three walls in the main room, but they are in good condition (Fig. 4). Some fragmentary geometric decorations from the upper part of the columns remain in the same room as well. No trace of color could be detected on the panels or any other stucco decoration. Graffiti, mainly of animals, are evident in different parts of the site. Unfortunately, most of this material is still unpublished (Hozhabri 2013: 39).

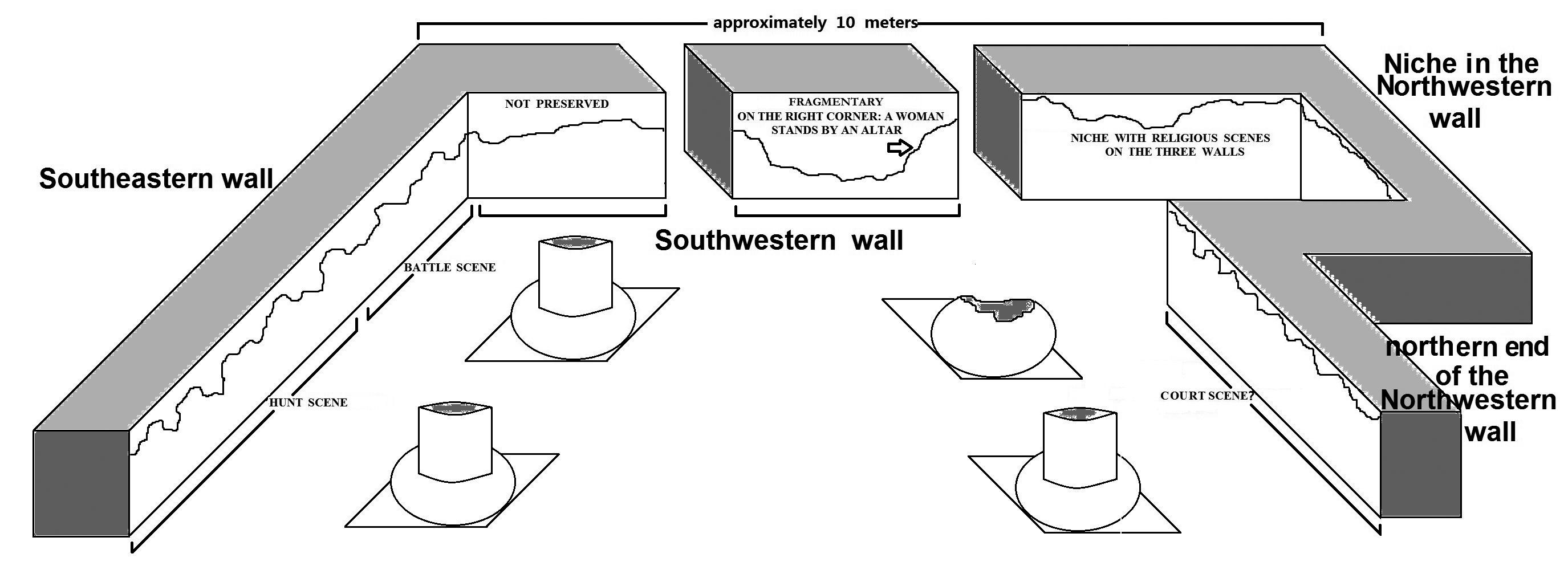

Each wall is approximately ten meters long; a seventy- to eighty-centimeter-high portion of stucco is still visible on three of them (Fig. 5). At least six different scenes can be found on the stucco panels: two on the southeastern wall (hunting and battle scenes, Figs. 6–7), two very fragmentary religious(?) scenes on the southwestern wall (Fig. 8), one religious scene divided into three sections in the niche in the northwestern wall (Fig. 9) and, finally, one long scene with standing and seated people on the remaining portion of the northwestern wall (Fig. 10). Rectangular friezes embellished with vegetal elements, shaped as typical Sasanian spread wings, delineate panel compositions.

The panel on this wall is divided into two portions by a vertical element, embellished with a double row of

squares, each with a dot in the center, approximately in the middle of the panel. The left-hand part of the southeastern wall depicts a hunt with two men galloping on horses in pursuit of their prey (Fig. 6a–b). In front of each rider is a crouching deer. The first deer is not well preserved, while the second one has massive antlers and muscular forelegs. A broken arrow sticks out from the left side of this animal’s neck, while an additional two arrowheads are visible on the right. The quivers hanging around the hunters’ waists indicate that they were equipped with bows. At the end of this scene, on the right, remain two legs of another horse. The different kinds of hooves on the deer and the horses are realistic and seem based on the artists’ actual observations. Thus, it is most likely that the hunters originally were at least three in number. A fourth hunter may have existed at the very beginning of the scene on the left, while a harness adorned with a double row of discs, probably pearls, along with a portion of an animal’s foreleg, suggest that another horse accompanied him.

No specific textile decorations embellish the garments of the hunters. The hunter on the left wears plain trousers and high boots with a double row of a pearl pattern. A short tunic above trousers and high boots embellished with a single string of pearls constitute the garments of the hunter on the right. On his trousers there is only a small section decorated with droplet-like motifs, perhaps stylized hanging jewels or metal decorations sewn directly onto the trousers. Similar decorative elements appear on the garments of the Sasanian king, who stands between two deities in the upper back part of the larger grotto at Ṭāq-e Bostān, as well as on figurative column capitals that were kept in the park at that site until a few years ago (Harper 1978: pl. 54). Additionally, the ornamentation on a silk fragment in the Victoria and Albert Museum imitates a hanging, drop-shaped jewel with a circular element in the upper part, meant to be sewn onto an actual textile (Ghirshman 1956: 209). Returning to the attire of the two hunters, the fabric covering their knees shows a circular element. According to Rahbar, this kind of decoration might suggest a military garment (Rahbar 1998: 221).

The horses’ saddles do not show a particular decorative motif or specific harnesses, only waving lines along the edge, perhaps suggesting fur. Only the horse on the left sports the hanging tassels that appear on the horses of Ahura Mazda (the supreme deity in Zoroastrianism) and the Sasanian king in rock reliefs (Tanabe 1980). The tail of the second horse ends in a very elaborate yet realistically tied knot. Quivers present more interesting ornamentation, possibly representing textiles, leather

tooling, embossed metal, painted decoration, or incrustations with precious stones. It is worth observing that stirrups do not appear in this scene or in the battle scene; this element of harness was still unknown in Iran and most of Central Asia when the stucco panels were finalized.

At least eleven individuals appear in the battle scene (Fig. 7a–k). One warrior on the left (Fig. 7a) confronts two enemies (Fig. 7b–c) who come from the opposite direction, while the corpses of four fallen opponents lie open-mouthed beneath the horses’ hooves (Fig. 7f–i). These fallen, represented in profile, have short hair, moustaches, and short beards. All have almond-shaped eyes, which suggested to the excavator, Rahbar, that they are Iranian Huns (specifically Hephthalites) with whom the Sasanian king was presumably at war (Rahbar 2004: 19). Rahbar also proposed that the main Persian warrior on the left is a king because of the ribbons attached to his feet (Rahbar 1998: 220). On the right, behind the second galloping horse, only a small part of the feet of at least two persons standing on two dead enemies can be seen.

The horseman (Fig. 7a) who confronts two mounted enemies wears a tunic over his trousers, which are patterned with discs containing a circle and dot, plus a circular element on his knee. His trousers are tucked into high boots with a pearl-pattern border at the top and ribbons in the lower part. His saddle, too, has the same decoration as in the hunting scene and also a strange motif repeated many times that could be a stylized animal. That warrior is equipped with a long scabbard resembling the element used to separate the hunting and battle scenes. Despite the elaborate harness of his horse, the animal is not adorned with the hanging tassels which, on the contrary, appear on both horses of his opponents. The dead enemy (Fig. 7f) below his horse wears clothing decorated with a three-dot design that is also found on the trousers of his immediate opponent (Fig. 7b). The latter is trampling on three dead enemies, also characterized by almond-shaped eyes but who show no textile decoration (Fig. 7g–i). Apart from the three-dot design of the trousers, the man trampling the fallen does not display any other decoration. His boots are less elaborate than those of the first horseman (see Fig. 7a) and he also has a circular decoration on the knee. In the right-hand part of the scene, at least one of the two figures that stand on the enemy dead has ribbons attached

to his boots (Fig. 7d–e). The enemy dead have mustaches (Fig. 7j–k), and the one on the left wears a simple hoop earring. His garments present the same droplike motif already noted in the hunting scene, while the other dead enemy’s clothes are decorated with a scattered design of simple dotted discs. Decorations very similar to the threedot pattern represent the main motif on the garments of the king at the rear of the large grotto at Ṭāq-e Bostān and on some contemporary figurative column capitals at that same site (Compareti 2018). This design also occurs in paintings probably representing important members of the Sasanian royal family in the fourth-century manor house at Hajiabad in Fars Province, Iran (Azarnoush 1994: 174–75).

It is not easy to propose an identification for the people in this battle scene. If the repetition of the same garments could be considered a means of identifying one person represented sequentially, then the dead enemy (Fig. 7f) below the horse of the first warrior on the left (Fig. 7a) should be the one who is still riding a horse on the right (Fig. 7b). A typical Sasanian formula that was rooted in more ancient Mesopotamian art is the double representation of the prey in front of the hunter king and already dead under his horse (De Francovich 1984: 89–98). This formula is also evident in Sasanian rock reliefs such as those at Naqš-e Rostam, where the opponent of the king appears twice in front of him and already dead under his horse (Callieri 2014: 121). However, another typical Sasanian element seems to be the hanging tassels that are attached only to the horse of the sovereign. If the main warrior should be identified as the one on the left (Fig. 7a), then the absence of this part of his harness would point to someone not intended to be the Sasanian king. Only the second warrior (Fig. 7b) opposing the main person could be considered an important enemy (perhaps the king of the Huns?), while the third warrior (Fig. 7c) arriving from this direction could be another Persian coming to help the first warrior by attacking his opponent from behind. This does not seem to be very convincing, since Persian literature of the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods is full of references to single duels between champions or royal heroes. The repetition of dead enemies that resemble Huns (or other “Turanian” people) points to this reading. However, one (Fig. 7e) of the two persons on the right who stand victorious over dead enemies could be connected to the first warrior on horseback, since both wear beribboned shoes embellished with pearls. It is worth observing that the dead enemies under the horses or the feet of the victors have their heads oriented in a similar way: the one (Fig. 7f) below

GeorGina Herrmann

Stylistic analysis, backed up by technical studies, is an essential tool employed by art historians and museum curators, among many others. This approach was developed by the Italian art historian Giovanni Morelli, thanks to the introduction of photography in the midnineteenth century. Recently it has fallen into disrepute, perhaps because critics have failed to understand the tripartite division of a catalogue: stylistic analysis, supported by technical studies, with a commentary. While the first two are “hard data,” the commentary is necessarily more speculative but is based on “hands-on” knowledge of all the material. Prudence Harper’s 1981 monograph with technical studies undertaken by Pieter Meyers, Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period, is an excellent example.

Avisitto the Metropolitan Museum of Art during Prue Harper’s long and distinguished curatorship was always a privilege. Not only was it a real pleasure to see Prue and discuss things Sasanian together (although by that time I was probably working on the Nimrud ivories), but also she was unfailingly supportive and helpful. Not only were hotels booked, and often paid for, and grants found, but all the material was made available, as well as space in which to work. Furthermore, lectures were arranged, and—as a final treat—so was dinner in her lovely flat. Happy memories. I can also remember a pleasant dinner in a little French restaurant, Mon Plaisir, in Covent Garden….

This small contribution is a brief defense of the way that Prue worked in her seminal study, Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period, Volume I, which is also the way most museum curators, art historians, and archaeologists do. Fundamental is a detailed and meticulous study of the actual objects, together with any relevant information on provenance and history, backed up by suitable technical studies. Since, all too frequently, the material to be studied

Inner and Central Asian Art and Archaeology 3 47–53

is dispersed in a variety of museums or collections, it is heavily dependent on a full photographic record to act as an aide-mémoire.

The Italian scholar Lionello Venturi (1885–1961) fully understood the significance of the introduction of photography.1 It made possible major advances in the study of Renaissance art by the eminent nineteenth-century Italian art historian Giovanni Morelli (1816–1891). Prior to that, comparative studies by the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle (1819–1897) depended on the drawings he made of the paintings he saw.

Venturi (1964: 233) wrote that “gifted with a tenacious visual memory and a noteworthy sense of quality in painting, [Cavalcaselle] succeeded, with the aid of his own drawings, in comparing in a precise manner the style of works seen at wide intervals of time and place.”

While photography reproduces only a general view of the work of art, Venturi (1964: 234) opined that

a comparison between photographs, by anyone who is familiar with the originals, can give a certainty on stylistic affinities or differences, otherwise impossible.

The first … to correct many errors of attribution, some of which had escaped Cavalcaselle himself, was another Italian, Giovanni Morelli. He was a physician, a follower of the anatomist Döllinger, and therefore he had the taste for exact science; he was a collector, and he had an outstanding artistic sensibility.

Morelli’s approach was based on direct observation, backed up by his photographs, as Venturi (1964: 234) noted:

He professed to observe that the painters of the fifteenth century, so attentive to variations in the model, repeated conventionally the hands and the ears, and he generalized this observation so far as to make of it a law: the works in which hands and ears are drawn in the same manner are by the same author.

His approach was followed and codified by the distinguished early twentieth-century art historian Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), as described by Marian Feldman (2014: 19):

The most influential element in Berenson’s methodology is his clear articulation of the ranked weight of the visual elements used in distinguishing … the general grouping of a regional and period school, and then on a second order, the characteristics that set specific individual artists (hands) within a school apart from one another. In between schools and artists is the workshop, the locus where a master artist worked with lesser artist apprentices.

In our modern world, we are visually bombarded with images across all media, each and every day. It may therefore be hard to realize the overwhelming impact of photography in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Not only did it make possible Morelli’s pioneering studies, but it underpins all subsequent objectbased studies, museum and exhibition catalogues, and architectural surveys. Suitably adjusted to the various types of material studied—paintings, Greek vases, Sasanian silver, Persepolis reliefs, Nimrud ivories, and so on—detailed examination of all the material, substantiated by a full photographic record, remains fundamental. Until the 1990s, such study relied on black-and-white or color prints and slides. Since then, there has been an ongoing revolution, initially with the digitizing of existing photographs and then with the development of digital photography itself. This has enabled photographs to be studied in detail on-screen and readily transferred to other scholars or interested people, and has simplified publication with cameraready copy.

Exciting new directions supported by Cultural Heritage Imaging2 have resulted in a computational photographic method, Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), that allows multiple images to be manipulated under varying lighting conditions to capture subtle surface information. Put simply, when a surface is illuminated from an extreme angle, it shows different information than a surface lit from above. By taking a series of photos from a single position but lit from different angles, the images can

be combined into an RTI, capturing an accurate record of a surface’s shape. Imagine turning something in the light to discern changes in the surface. It can also allow the object to be viewed under novel lighting conditions, allowing further information to be gleaned. This can reveal data not visible to the naked eye. Such advances offer important new tools to the study of artifacts.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a connoisseur as “a critical judge of art, especially of one of the fine arts.” In recent years, however, connoisseurship has almost become a dirty word. So, too, has the name of Morelli, even leading to arguments that Morelli was “motivated by a nationalist desire to define and reify ‘Italian’ art for the newly unified nation state” (Feldman 2014: 18; see also Anderson 1987; Anderson 1996; Brewer 2016: 7–8).

The Morelli system of rigorous stylistic analysis is a fundamental tool for classifying material culture. However, in recent years problems have arisen with, for instance, two “individuals reconstructing very different historical scenarios” from the same data (Winter 2005: 34). Irene J. Winter wrote that “to make progress in untangling competing hypotheses” we need “to set up exercises with a designated body of material amenable to attribute analysis, along the lines of the system used by Michael Roaf in his study of artistic hands and work groups” in the fifth-century BCE reliefs on the Apadana building at the Achaemenid capital of Persepolis, Iran (Winter 2005: 35).

These reliefs are unique in many ways: Not only is their location, date, and authenticity certain, but they consist of rows of closely similar figures, ideal for comparison. When he was at Persepolis, Roaf did not have to rely on photographs but made a detailed Morellian stylistic analysis directly from the actual sculptures (Roaf 1983). He selected a number of specific attributes. Being a mathematician and highly computer literate, he was able to run the attributes through a similarity matrix, which grouped them independently. He then had the great good fortune to notice a series of sculptors’ marks on the sculptures, the divisions of which matched his groups. As he himself noted, the principal function of these marks was to identify and distinguish the work of one sculptor or group of sculptors from that of another. This enabled him to reconstruct the teams of craftsmen who produced the carvings and also to note that a single figure was the work of more than one craftsman.

Both Roaf’s study of the Persepolis reliefs and, for instance, the magisterial study of Attic vases grouped by artistic style by the British classical archaeologist and art historian Sir John Beazley (1885–1970) relied on an indepth knowledge of the actual material. Beazley also had the advantage of building from a series of signed vases. In the absence of such advantages, the study of ancient art, such as Sasanian silver vessels, is considerably more complex, particularly as the material is widely dispersed, lacks secure provenances, and may even include later copies or fakes.

Harper’s Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period, to which Pieter Meyers (then senior research chemist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) contributed the technical study, provides an excellent illustration of the essential tripartite role of a museum catalogue. It consists of a stylistic analysis; a technical analysis of the material, its sources, and methods of manufacture; and an interpretative section or commentary. This division between catalogue and commentary is fundamental. The catalogue entries, the photographic record, and the scientific analyses provide the hard data about the material, and this remains a permanent foundation for further study. However, it is only the scholars who have prepared such a catalogue who have the deep, comprehensive, hands-on knowledge of the material. It is therefore the essential duty of the authors, having completed the catalogue, to continue and develop interpretative hypotheses. Such hypotheses will undoubtedly require adjustment and correction through time, particularly as new evidence is found and new approaches are undertaken, but that is the nature of scholarship.

Harper’s decision to study Sasanian silver vessels was, without doubt, an exceptionally challenging one. Most of the thirty-seven silver vessels with royal imagery that she catalogued lack any meaningful provenance, being widely dispersed in museum and private collections around the world. They were made over a long time range and a broad geographic area, and there is the additional major problem of whether some are genuine or fake. However, the realization that the early Sasanian kings each wore a distinctive, personal crown, identified from the dated coin sequence, provided an important external source of evidence (Harper and Meyers 1981: 9).

Harper and Meyers succeeded in providing meticulous descriptive analyses and full technical studies, which

in turn led to new insights into the development of the Sasanian monarchy. While Harper focused on a careful study of shape, style, and iconography, Meyers was interested in the sources of the silver ore, whether it was alloyed with copper, and whether the fineness of the silver was controlled. Visual and low-power microscopic examination were employed to study surface characteristics such as tool marks, joining techniques, and gilding; and X-radiography was used to reveal methods of manufacture. Together the authors succeeded in classifying the vessels in stylistic, technical, and chronological groups and proposed that

[there] existed both a central Sasanian royal production subject to state controls and an independent, provincial industry that was the source of a related class of vessels. The royal plates identified here as central Sasanian are executed in the paired-line drapery style. On all examples, the kings wear correctly rendered Sasanian crowns. These plates are presumed to have been executed from the time of Shapur II (309–379) onward, in workshops under the control of the Sasanian court (Harper and Meyers 1981: 124).

Shapur II and his court lived at Karkha de Ledan in Khuzistan, where the royal workshops were sited near the palace. Shapur “organized the artisans, separating the workers into corporations according to métier” (Harper and Meyers 1981: 16). He appointed a Syrian, Posi, as chief of artisans, as well as overseer of workshops in other parts of the kingdom, indicating that more than one center of production existed as early as the fourth century. All artisans in all parts of the Sasanian state were evidently subject to royal control (Harper and Meyers 1981: 124).

The individual crowns of the Sasanian kings were crucial in another study of Sasanian art, that of the early Sasanian rock reliefs. These present different problems from those of the vessels. First, as they are carved on cliffs, there is no doubt about provenance. They have been variously described, drawn, and commented on during the last two centuries, with a variety of imaginative interpretations of the various scenes, based on the presumed scene depicted. Unfortunately, the reliefs are not easily accessed and only about half have been catalogued with a thorough description, a full photographic record, and

Pieter Meyers

The principles of lost-wax casting in the ancient Near East and Central Asia are generally well understood. Therefore, this contribution does not address in any detail the historic and geographic developments of lost-wax casting. Instead, it highlights several key innovations with brief technical descriptions illustrated by a number of significant objects. Examples are presented where understanding casting technology and casting alloys have been employed in authenticity studies. In particular, lostwax casting versus piece-mold casting has been hotly debated and is one of several issues explored.

When I started my career in 1970 as a young scientist at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (The Met) I was soon made aware of a confusing issue in the field of ancient Near Eastern art. It was Prudence Harper, Curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art, who explained to me that the exhibition Sasanian Silver: Late Antique and Early Medieval Arts of Luxury, organized in 1967 by Oleg Grabar at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, had raised serious questions of authenticity and/or attribution for a significant number of silver artifacts shown in this exhibition. She also informed me that the general unease about the authenticity of all Sasanian silver and that the lack of reliable attribution criteria could reflect negatively on The Met’s collection. She encouraged me to start examining the Sasanian silver at The Met and investigate whether technical and scientific examination could provide information that could address the problem. At that time, I knew next to nothing about the Sasanians and even less about Sasanian silver. Prue patiently taught me and gave me a basic understanding of Sasanian art in general and of

Inner and Central Asian Art and Archaeology 3 55–70

the existing questions and issues of Sasanian silver in particular, and guided me to the relevant literature.

As I started to learn about methods of manufacture, alloy compositions and other technical characteristics of ancient silver, under Prue’s watchful eyes, I began a comprehensive technical examination of the museum’s Sasanian silver vessels. During this project I realized that it would be very difficult to state whether or not any of the objects were authentic, mostly because I lacked reliable standards, specifically access to excavated or securely documented Sasanian silver vessels. I asked Prue: where are the “real” Sasanian silver objects, and should I not go there and examine them? She answered that the largest collection of well-documented Sasanian silver is in the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and, yes, I should go there. I had not expected such positive encouragement, but not long thereafter, on February 2, 1972, accompanied by Prue, I walked into the offices of the Oriental Department of the State Hermitage Museum, where she introduced me to the staff members. She reviewed and discussed with the Hermitage staff a plan for me to examine and discuss with the staff every Sasanian silver object in their collection, a project I carried out during that trip and on a number of follow-up visits.

This research and related technical studies during and after the Hermitage project resulted in detailed information on the manufacture of Sasanian silver vessels and their alloy and trace element compositions. When combined with more traditional art historical studies this knowledge allowed more reliable classifications of Sasanian silver vessels, including their authenticity, and, in some cases, attribution and dating. Most of this study has previously been published in Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period, I: Royal Imagery (Harper and Meyers 1981).

Regarding the Ann Arbor exhibition, I subsequently had the opportunity to examine a significant number of objects published in the catalogue and obtain evidence in support or against their authenticity. For example, two silver

bowls and two silver plates (Grabar 1967: no. 38 and 39 and no. 14 and 31, respectively) were manufactured using the so-called “double-shell” technique, involving the use of two sheets of silver, one for the front and one for the back. This method was determined not to have been used for any of the Sasanian silver vessels I had examined at the Hermitage; it has become one of the criteria now used to establish their modern origin. On the other hand, the technical examination of a number of objects with questioned authenticity has provided convincing evidence in favor of their authenticity. They included the silver bust of a king (Grabar 1967: no. 50; Meyers 1981) (Fig. 1) and a silver container in the shape of a crouching antelope (Grabar 1967: 132, no. 49). I am greatly indebted to Prue for teaching me how to look at works of art, for guiding and encouraging me to pursue research in the application of scientific techniques in the study of art objects, and especially for instilling an interest in the arts of the ancient Near East, specifically as it applies to the use of metals, alloys, and metalworking techniques. Ever since my early introduction into Sasanian silver I have cherished my collaboration with her. I am most grateful for her guidance, friendship and support during the various projects, even after I left the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s employment. Thus I am pleased to submit this contribution to her Festschrift. What follows is a general overview of bronze casting technology in Western and Central Asia. Various objects, predominantly from museum collections, are used to demonstrate casting methods, casting materials, and their application in authenticity studies; I also include a controversy among scholars about the casting method used for bronze Dongson drums from Vietnam.

The earliest use of casting occurred in open or bivalve molds at some time during the Chalcolithic period (ca. 5500–3500 BCE). Lost-wax casting came into use several millennia later, but the exact period in which this casting method was first documented is uncertain. In its simplest form, the technique of lost-wax casting involves a model, shaped or carved in wax and then encapsulated in clay (“investment”). The wax is removed by heating, and the melted wax is then poured out through one or more pre-formed openings in the investment, via “gates” or “sprues.” The resulting hollow clay mold is fired to produce a solid ceramic, into which molten metal is poured through one of the openings. After solidification

of the metal and cooling, the investment is broken and removed, exposing a metal artifact, exactly reproducing the original wax model.

Archaeological evidence appears to indicate that the earliest lost-wax castings date to the late fifth millennium BCE. The most compelling evidence is found among the many artifacts of copper and copper alloys from the Nahal Mishmar hoard found in a cave near the Dead Sea (Moorey 1988; Shalev and Northover 1993), and among several small copper artifacts excavated in Mehrgarh (Baluchistan) (Bourgarit and Mille 2007). The Nahal Mishmar hoard and the Mehrgarh copper amulets have both been attributed to the late fifth millennium BCE. However, the dating to the Chalcolithic period (late fifth millennium BCE) of the lost-wax cast artifacts of the Nahal Mishmar hoard and the Mehrgarh artifacts has been challenged (Guil 2018). Based on technical characteristics and comparison with related archaeological evidence, it has been suggested that the hoard contains items from different periods and that the prestige items including the crowns and standards should be dated to a considerably later period. The author also claims that the evidence for lost-wax casting in the Mehrgarh is not convincing. It would be remarkable that the earliest lost-wax casting would occur not in the Chalcolithic technological centers of Anatolia, Iran and Mesopotamia, but outside these areas, in two unrelated and widely separated sites. Since there is very little archaeological evidence that there was a sustained lost-wax casting industry before 3000 BCE it is assumed here that lost-wax casting did not become widely used until the third century BCE.

The earliest lost wax castings used mainly unalloyed copper but also copper-lead alloys. It was not very long thereafter that successive modifications were introduced in alloy composition as well as in manufacturing methods. However, even though copper alloys had better casting characteristics, the use of unalloyed copper continued well into the third and second millennia BCE, as exemplified by the copper head of a ruler, excavated at Nineveh (Akkadian, ca. 2300–2159 BCE; Aruz 2003: 194–95, fig. 57), another head of a ruler dating to the late third millennium (Aruz 2003: 210–12, no. 136; Muscarella 1988: 368–74, no. 494), and a canephore foundation peg (Muscarella 1988: 303–305, no. 435), attributed to Early Dynastic III (ca. 2600–2400 BCE).

Unalloyed copper is difficult to cast. It has a high melting point and releases gasses during cooling. During the third

ISBN 978-2-503-60438-1