Reuse, Adaptation and the Evolution of Rome’s Theaters after Antiquity

Guendalina Ajello Mahler

Reuse, Adaptation and the Evolution of Rome’s Theaters after Antiquity

Guendalina Ajello Mahler

Reuse, Adaptation and the Evolution of Rome’s Theaters After Antiquity

INTRODUCTION 9

An ancient theater in modern Rome 9

Aims of the study 15

CHAPTER 1

SURVEY OF THE BUILDINGS AND HISTORIOGRAPHY 28

Palazzo Orsini-Pio-Righetti (Theater of Pompey) 29

Building survey 29

Historiography 35

Palazzo Savelli-Orsini (Theater of Marcellus) 37

Building Survey 37

Historiography 41

Palazzi Mattei (Theater of Balbus) 42

Building survey 42

Historiography 45

CHAPTER 2

THE THEATER DISSOLVED 46

Six meters of dirt 47

The breakdown in context 50

The years 300 to 500 51

The years 500 to 700 53

The years 700 to 1000 55

The years 1000 to 1200 58

Conclusion 63

CHAPTER 3

THE RUIN RECOMPOSED AS A FORTIFIED FAMILY COMPLEX 64

Forces of unity: the medieval complex in the ideal (13th–15th centuries) 65

The Arpacata Orsini on the theater of Pompey 68

The trullo of Donna Marale 68

Fortification: the Orsini’s first building campaign 70

Expansion: the Orsini’s second building campaign 73

The Monte Savelli on the Theater of Marcellus 76

Forces of division: the medieval complex in practice (13th–15th centuries.) 81

Family issues: the Orsini 83

Family issues: the Savelli 85

A merchant settlement on the Theater of Balbus 87

Conclusion 88

CHAPTER 4

THE COMPLEX REIMAGINED AS A PALACE 90

Houses or palaces: buildings in flux (15th–early 16th centuries) 91

Domus magnae, a slaughterhouse and an early renaissance palace 95

The complex as income property 95

The palace of Francesco Condulmer 98

Conclusion 99

The “domos seu palatium” of the Savelli 100

The palatium of the Savelli 100

Expansion of the Savelli palatium 102

Conclusion 103

The beginnings of the “Isola Mattei” 104

Dreaming of the palazzo (16th–17th centuries) 106

Palazzi Mattei 108

Palazzo di Giacomo (“habitationes et domus veteres”) 108

Palazzo di Alessandro (Palazzo Caetani) 111

Palazzo di Ludovico II (Palazzo Mattei di Paganica) 114

Palazzo di Asdrubale (Mattei di Giove) 117

Palazzo Savelli 119

Baldassarre Peruzzi at the Theater of Marcellus 120

Palazzo Orsini 130

Campo de’ Fiori under the Orsini of Bracciano 130

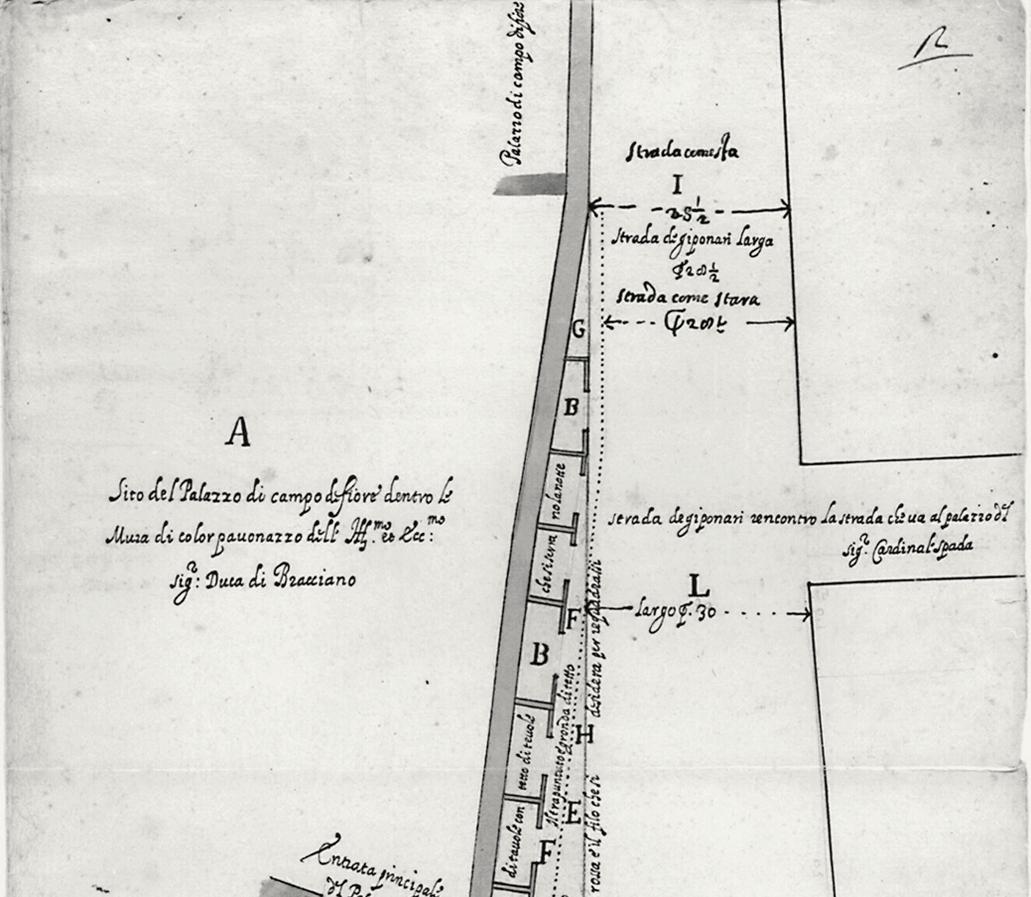

The Palazzo at Campo de’ Fiori under the Orsini of Bracciano 132

The palazzetto on Campo de’ Fiori 136

The palace under Paolo Giordano I 140

Conclusion 143

CHAPTER 5

THE PALACE IMPROVED 146

Miglioramenti: the un-architecture (16th–18th centuries) 147

Debts, discord and additions: Palazzo Savelli 149

Miglioramenti made by Cardinal Giacomo Savelli

(late 16th century) 149

The institution of primogeniture 150

The family’s use of the palace in the seventeenth century 151

Miglioramenti made by Duke Federico and others 151

The sale to the Orsini, and the redefinition of the palace 154

The palace as income property: Palazzo Orsini 162

The Palace as Income Property 162

Miglioramenti made under a long term rental 164

Miglioramenti made under short term rentals 165

Miglioramenti made as part of a temporary sale 166

Miglioramenti made by Virginio Orsini 168

Miglioramenti made as part of owner–tenant and owner–neighbor partnerships 170

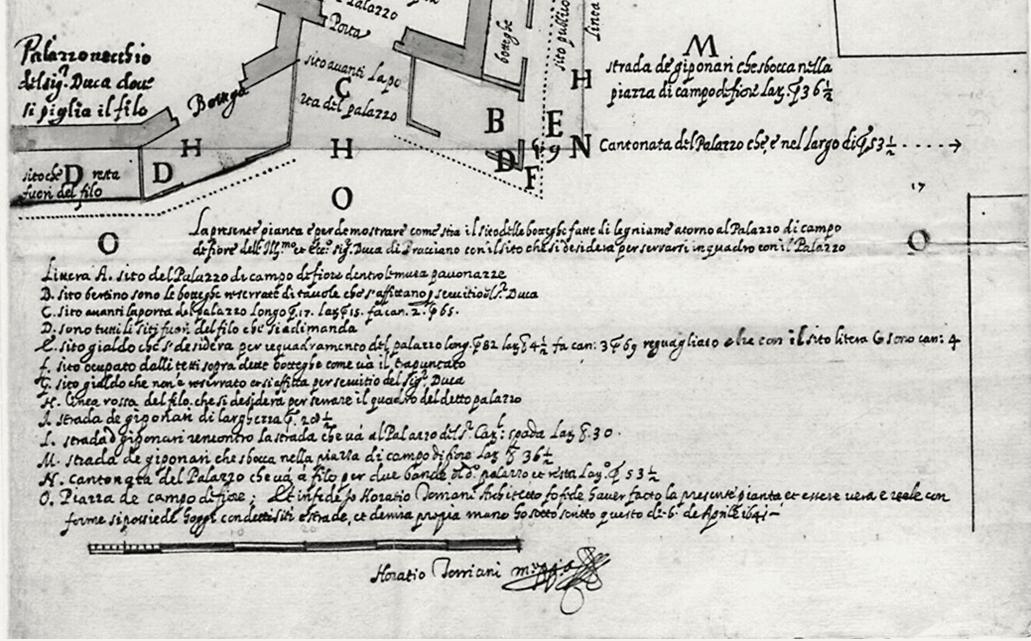

Miglioramenti only imagined: unrealized projects 175

The sale to Cardinal Pio and the redefinition of the palace 177

Frozen in time: Palazzi Mattei 178

Conclusion 179

CONCLUSION 184

APPENDICES 188

Appendix 1: The Pierleoni at the theater of Marcellus?

A documentary conundrum resolved 189

Appendix 2: List of miglioramenti made by Cardinal Giacomo Savelli at Palazzo Savelli and its stables 193

Appendix 3: Arguments for the purchase of Palazzo Savelli by the Orsini of Gravina 195

Appendix 4: Sale of Palazzo Savelli by the Congregazione dei Baroni to the Orsini of Gravina 196

Appendix 5: Contract giving Cardinal Pucci permission to build on a neighboring building at Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori 197

Appendix 6: Agreement between Paolo Giordano II Orsini and S. Lorenzo in Damaso regarding a house adjacent to Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori 198

Appendix 7: Excerpts from a rental contract of Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori to Cardinal Giulio Sacchetti 199

Appendix 8: Orazio Torriani’s description of Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori 200

Appendix 9; Cost analysis of a proposal to open a street with shops through Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori 202

Appendix 10: Contract of sale of Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori from Paolo Giordano II to Cardinal Carlo Pio di Savoia 204

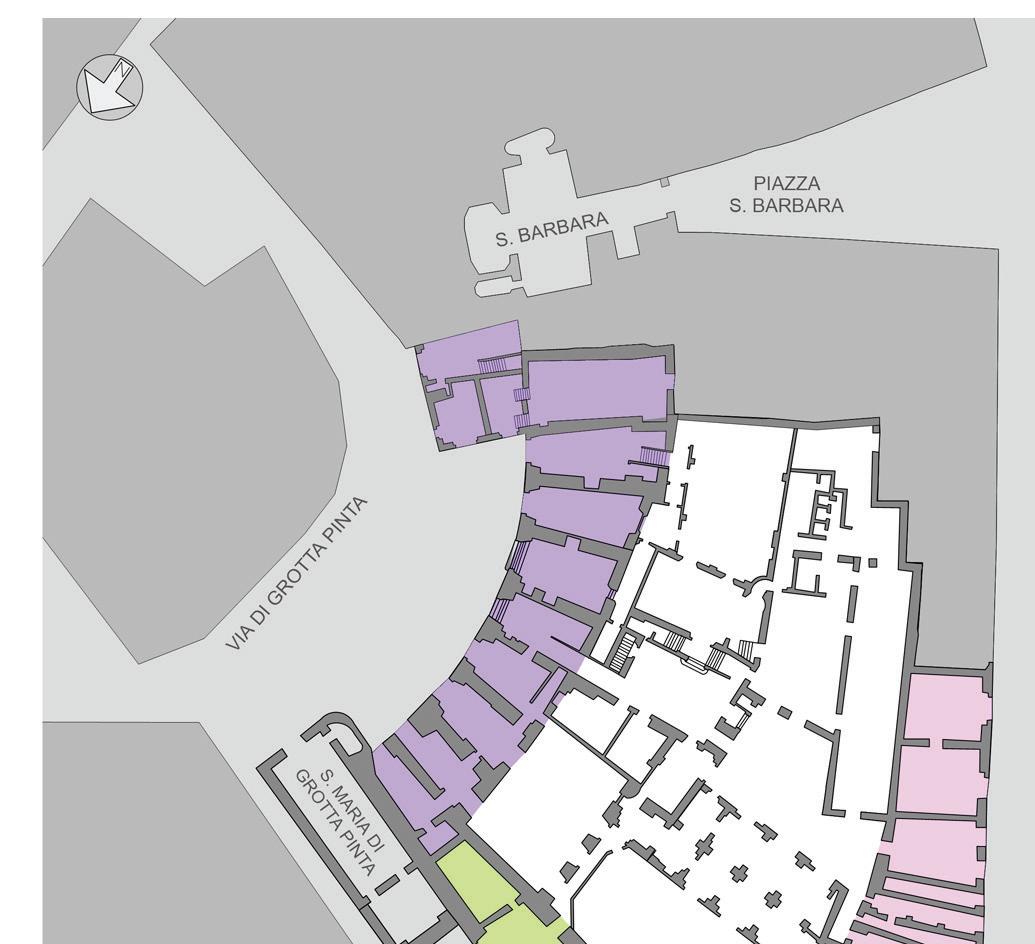

Appendix 11: Notes to a plan for incorporating a house owned by S. Maria di Grotta Pinta into Palazzo Pio di Savoia (formerly Orsini) at Campo de’ Fiori (Pl. 125) 206

Appendix 12: Genealogical Tables 207

Appendix 13: Timeline of documented rentals and sales of Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori 211

BIBLIOGRAPHY 212

LIST OF PLATES & CREDITS 220 INDEX 227

ASC Archivio Storico Capitolino, Rome.

ASR Archivio di Stato, Rome.

BAV Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Orsini ASC Archivio Storico Capitolino, Rome, Archivio Orsini.

Orsini u C l A Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles, Orsini Family Papers (Collection 902).

Ambrosiana, Pio di Savoia Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Collezione Falcò Pio di Savoia.

The process by which these layers were created is also plainly in evidence across the city. As though in frames of stop-motion animation, many of Rome’s buildings stand with toothy edges, poised to gobble up older neighboring properties, in a game that has been vividly compared by Joseph Connors to the big fish eating the little fish.2 A cluster of buildings in Piazza dei Caprettari illustrates the broader process (Pl. 22). The two small buildings at the center of the frame, with their mismatched windows, are the oldest visible structures. To these a third and then a fourth story

were added, and their interiors may have been joined. One of the buildings eventually gained two more floors, while the building at the far right expanded forward, filling a sliver of space left in the uneven street line. It pushed out into the public domain as far as it could get away with, at first probably only on the ground floor, then adding more height and elbowing onto its neighbor’s façade with its cornice. In the meanwhile, on the opposite side, Palazzo Lante grew to an entirely different scale, and bared its teeth in the declared intent of taking over the whole mess. Thus, in ways big and small, out of centuries of near abandonment and many more centuries of growth, today’s Rome evolved, sometimes deliberately and dramatically, as with the grand papal projects, but more often through the slow attrition of individual wills competing to build the next story, the next expansion, layer after layer.

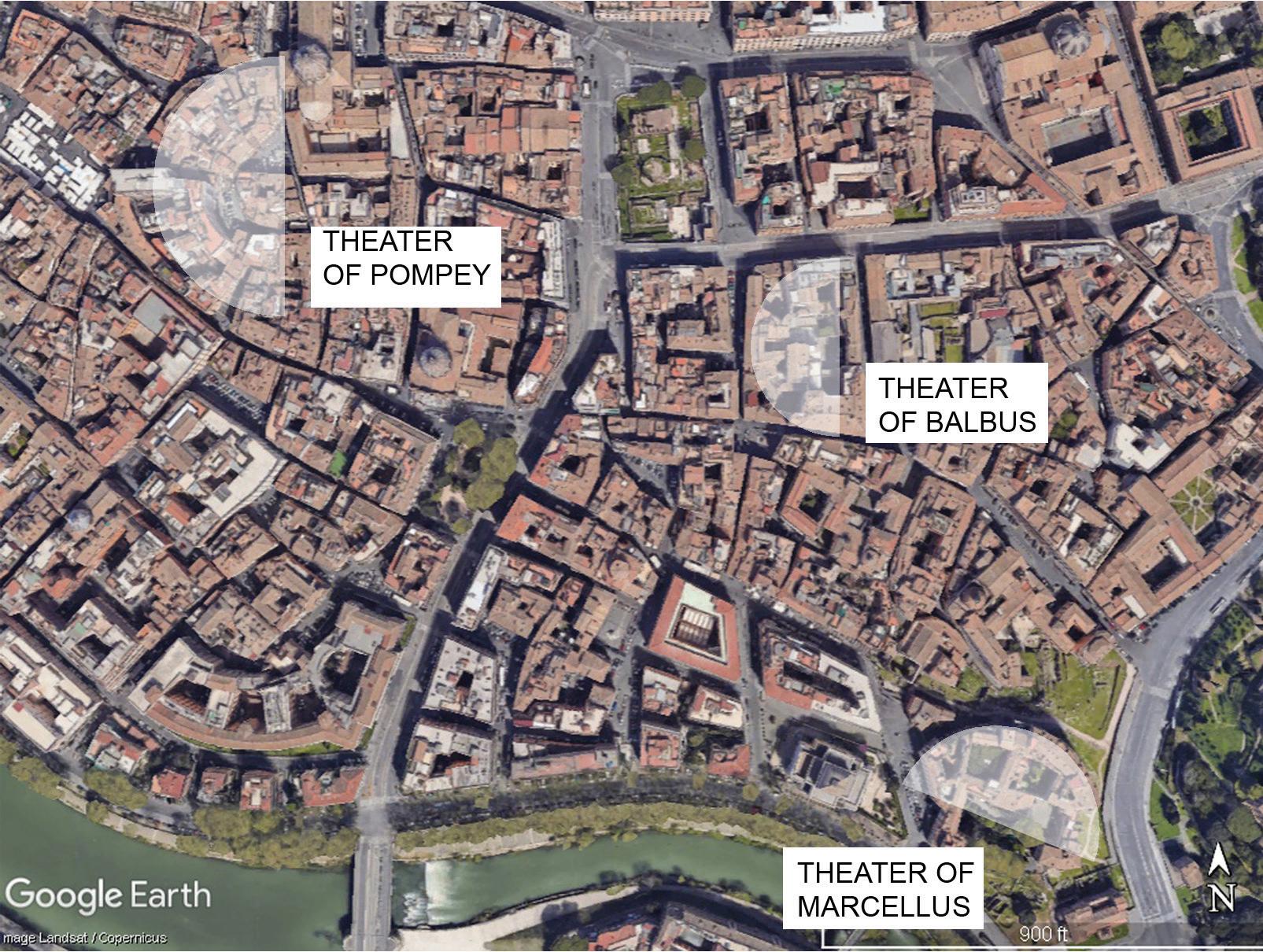

My study focuses on how this process of transformation took place at three ancient Roman theaters. In particular, I examine the post-antique interventions of the families that took over a substantial portion of each of the ancient buildings. I look most closely at the Theater of Pompey, in which the Orsini installed their family compound, and the Theater of Marcellus, which was taken over by the Savelli. The history of these buildings has had to be reconstructed almost entirely from documentary sources. I also look at the interventions of the Mattei at the Theater of Balbus. This building has been the object of excellent studies, so I have not had to reconstruct its history. It has nonetheless been included for the insight it offers into an alternative path of evolution. All three structures underwent a similar sequence of changes after antiquity and under the ownership of these families: first the breakdown of the ancient theaters and their rudimentary reuse, then reassembly as medieval family compounds, followed by adaptation as formal Renaissance-style palaces, further adaptation according to the owners’ ongoing needs and, in two cases, one final transformation: the remaking as archeological artifacts. Though only the Theater of Marcellus was actually extensively excavated, the same had also been planned for the Theater of Pompey, and designs survive from a competition for the treatment of the ruin and its integration into the neighborhood.3

The theater buildings will be core samples, as it were, for an exploration into the depths of Rome’s physical evolution. As samples these buildings are not exactly typical, especially since in each case I concentrate on the parts owned by one family, and only briefly consider the areas that were owned by many small individual proprietors. The three families which took over the monuments were

also atypical, since they were among the richest and most powerful in Rome and beyond. Yet this approach has advantages. Illustrious ownership has made the history of these buildings especially traceable in written sources, which means that we are not limited to hovering above the city, looking at general urbanistic trends. Rather than seeing the transformations of the urban fabric as impersonal, almost biological impulses of the city, we can approach them as the choices and actions of particular individuals.

Rome’s ancient theaters also make particularly appealing case studies because the sheer scale and unwieldy configuration of these extraordinary public monuments has meant that the city was rarely able to swallow them entirely. As a result, physical evidence of the process of their transformation is still visible. Though it is only at the Theater of Marcellus that substantial ancient structures are still exposed, the other two theaters also betray their ancient origins, as can be seen in a comparison between the “plastico” model of ancient Rome, and aerial views and plans of the theater-buildings today (Pl. 23–27). The views show how the theaters’ semi-circular contours, radial structure and massing remain fossilized in the fabric of today’s city like petrified wood, whose organic fibers, long gone, have been replaced by minerals which reflect their original configuration precisely.

A final reason why these buildings make for good case studies is that all three have their place in the canonical history of architecture. Not only were the original theaters among the most notable monuments of ancient Rome, but some of their subsequent incarnations earned their own positions in the pantheon of noteworthy historic buildings. The Orsini and Savelli fortresses were important enough to appear in the Limbourg brothers’ map of monumental Rome (1411–16) (Pl. 28), and the Mattei palaces also have a place, primarily for the interventions of architects such as Giovanni Mangone, Nanni di Baccio Bigio, and especially Carlo Maderno (Pl. 29).

If the status of these buildings as significant monuments is not in question, both in antiquity and beyond, where to look for interpretive models for understanding them is less evident. The survival of antiquity is one of the most thoroughly explored aspects of western culture. The reprisal of ideas and texts, myths, images and motifs, as well as the reuse of physical remains such as sculptures or architectural spolia all of these aspects of ancient

2 Connors, 1989a, 217.

3 Galassi Paluzzi et al., 1937.

1

BuIlDINg SuRVey

About one third of what was the ancient Theater of Pompey is occupied today by a large palace built on the theater’s ruins by the Orsini family. The building was later owned by the Pio family, then the Righetti, and finally by its current owner, a charitable institution called Istituto della SS. Assunta (also known as Istituto Tata Giovanni).1 The rest of the site of the ancient theater is occupied by two churches and by small buildings, including several in which the remains of the theater are still visible. Though I will briefly discuss these houses, my primary focus will be on the great palace which occupied the bulk of the ancient monument.

The palace, an anonymous seventeenth century observer noted, “è così murato all’antica che non si può pigliar forma di facciata.”2 It was not the classical sense of all’antica that the observer invoked — the palace displayed little of that — but a more blameworthy notion of building in an antiquated way. The contours of Palazzo Orsini have changed little since the seventeenth century and still now, as then, the palazzo does indeed turn a curious face towards the important market square of Campo de’ Fiori (Pl. 30–32). The palace’s principal façade consists mainly of a one-story

1 For an overview of the Theater of Pompey in antiquity, see Richardson, 1987; P. Gros, “Theatrum Pompei,” in Steinby, 1993, vol. 5, 35–38; Sear, 2006, 57–61, 87–88, 133–35; Gagliardo and Packer, 2006; Packer, Gagliardo, and Hopkins, 2010.

2 Ms. 721, Fondo Vittorio Emanuele, Biblioteca Vittorio Emanuele, Roma.

Published in Tomei, 1939, 224. Tomei dates the manuscript to 1601,164.

3 Connors, 1989a, 217.

4 On the Orsini family in the Middle Ages, see above all Allegrezza, 1998. Also Carocci, 1993a, esp. 387–403. On the Orsini in the post-medieval period, see Celletti, 1963; Shaw, 1981; Shaw, 1988; Shaw, 1992; Shaw, 1995;

structure used today as the vestibule for the Cinema Farnese. It traces a crooked line along the east end of the piazza, then turns onto Via dei Giubbonari. To the north of this low building (to the left in Pl. 31) stands a dainty sixteenth century palazzetto, trimmed in travertine, which projects sharply out into the piazza, and stands in visible contrast to the unceremonious character of the rest of the façade. The palazzetto, in turn, is hemmed in by the jagged edge of an unfinished seventeenth century façade commissioned by subsequent owners and poised to devour the smaller buildings.3 Behind all of these, looming soberly, is the irregular hulk of one of the palace’s residential wings.

Viewed from Campo de’ Fiori, the building’s appearance is so odd that one strains to see in it the palace of one of Rome’s two leading families (the other being their arch-rivals the Colonna). The Orsini rose to power in Rome in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries, at a time when a few families filled the gap created by the struggle between a weakened papacy and a fledgling communal government.4 During this period the Orsini acquired scores of feudal lands in the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples. As baroni, they belonged to the top stratum of Rome’s élite, with a social and even legal standing superior to that of the rest of

Triff Burgard, 1998; Triff, 2000; Shaw, 2007; Ago, 2008; Ajello Mahler, 2008; Castiglione, 2008; Kuehn, 2008; Shaw, 2008; Furlotti, 2012; Furlotti, 2013; Triff, Forthcoming. For a view of the Orsini through the lives of two women who married into the family, see Murphy, 2005; Murphy, 2008. The most accurate genealogy of the Orsini up to the

fourtheenth century is in Allegrezza, 1998, tavv. 1–11; for the later period, see Shamà, 2003–24, “Orsini,” an extremely useful collation of genealogical information from numerous sources, including the fundamental entry on the Orsini in Litta and Odorici, 1819–82, vol. 7, fasc. 113–15, which continues to be valuable for its long biographical notes.

the nobiles viri. 5 Over the following centuries, the Orsini’s private armies and enormous wealth made them crucial players in the complicated game of Italian politics. They remained important in Rome’s balance of power well into the sixteenth century.

Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori was one of several seats the family established in city. At the height of the family’s power, in the late Middle Ages and into the early Renaissance, the building was considered one of the most important and admired in Rome. It figured among the landmarks singled out for representation in early fifteenth century maps of Rome (Pl. 28), and in 1462 it was cited as an exemplary palace for a cardinal, described as “bellissimo, hornato quanto dir si possa.”6 As late as 1510 it was still considered one of Rome’s finest residences: Francesco Albertini, who described Roman palazzi in order of importance, put it at the top of his list of cardinals’ palaces, second only to the Cancelleria.7

The presence of the ruins of an ancient theater beneath the building only partly accounts for the theater’s unorthodox shape. Indeed, the façade which most directly reflects the awkward forms of the ancient theater upon which it rests is also one of the palace’s most coherent. It is the curved sweep of its rear wing on Via di Grotta Pinta (Pl. 33). In the remainder of the palazzo the building’s ancient origins are less easily identifiable, but the process of accretion and transformation that resulted in the Palazzo Orsini at Campo de Fiori lies undisguised — though, up to now, unexplained. In fact, in spite of a number of studies on the building, the evolution of Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori remains almost completely obscure.

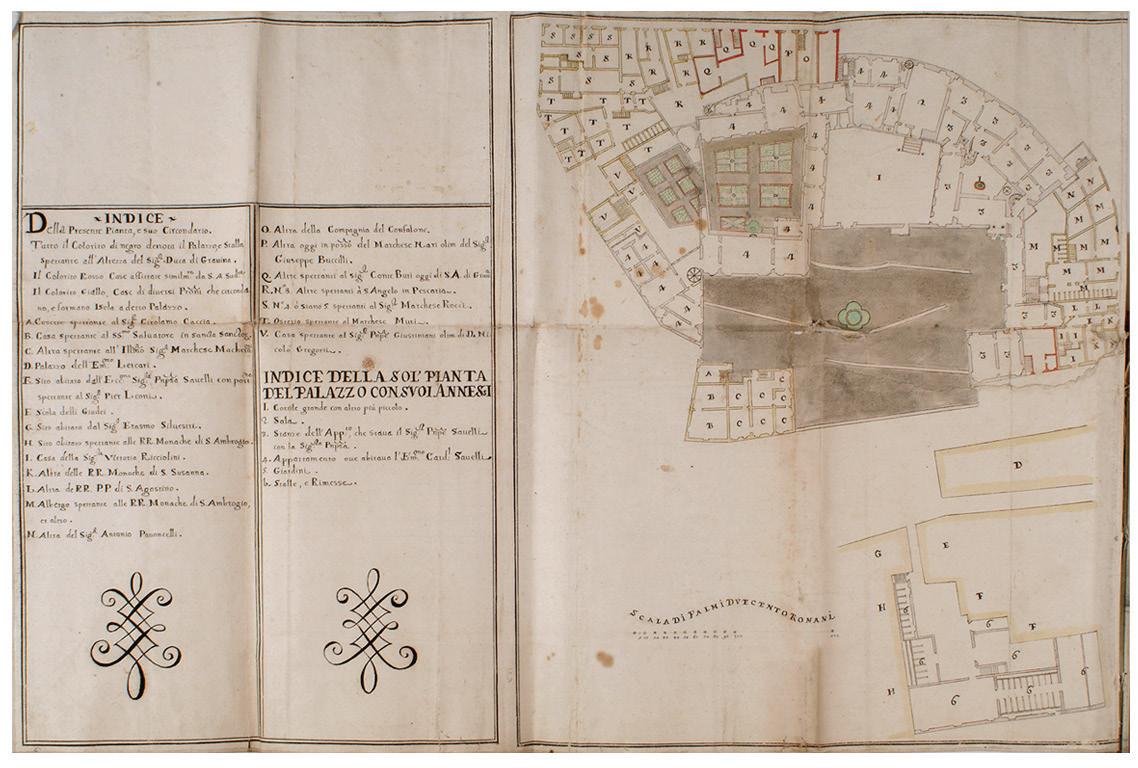

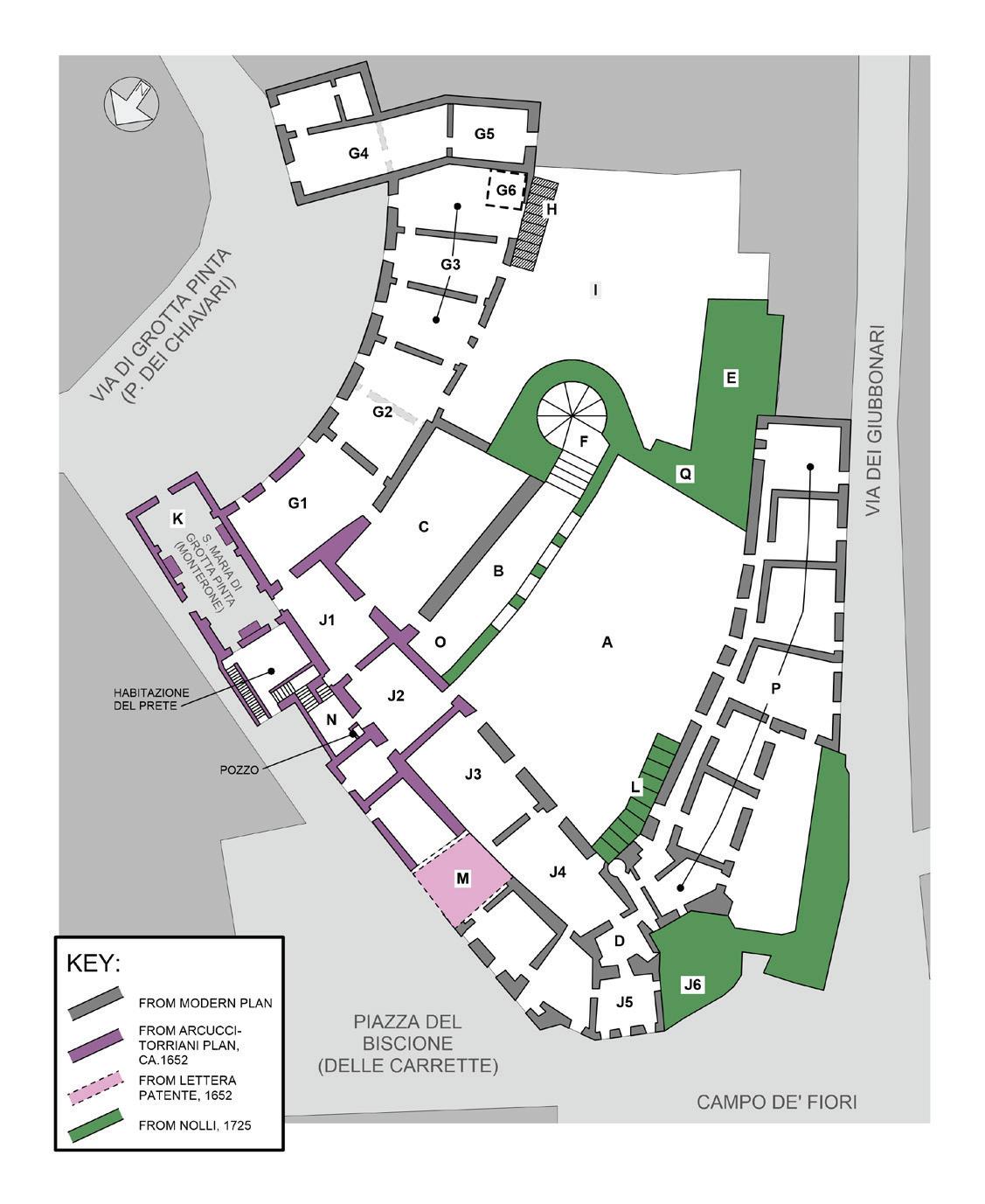

The easiest way to understand the complicated structure of Palazzo Orsini is to start by peeling away the most recent accretions. In the Catasto Urbano of 1819 the palace, numbered 325, occupies the south side of the ancient theater site, and includes most but not all of the block bounded by Via di Grotta Pinta, Piazza del Biscione, Campo de’ Fiori, Via dei Giubbonari and Piazza S. Barbara (Pl. 34). If we compare the Catasto to a current plan and aerial photograph, it is clear that most of the structures that clutter the area within the precinct of the palace are very recent additions (Pl. 32 and 35).8 Only in the twentieth century was the large courtyard divided by a new wing, the garden almost completely built over, and the forecourt on Campo de’ Fiori filled in with the onestory structure we see today.

A further comparison with Giovanni Battista Nolli’s plan of 1748 (Pl. 36) shows that the building changed little in the intervening years. The only addition was a small extension south of the main stairs. At the time of Nolli’s plan, the palazzo was owned by

the descendants of Cardinal Carlo Pio di Savoia, who had bought it directly from the Orsini in 1652. Shortly after acquiring it, Cardinal Pio hired Camillo Arcucci to design a grand renovation for the palace. Only a third of it was executed: the north façade on Piazza del Biscione, which is shown in Giuseppe Vasi’s view of 1748 and which can still be seen today (Pl. 37). We know what he had planned for the rest of the building from two lettere patenti requesting slivers of public soil needed for the renovation (Pl. 38A and B ).9 The lettere show that, though the plan would eventually have involved substantial new building, the part that was executed was largely cosmetic. The contours of the palazzo before the 1652 sale were almost exactly as they are today, with the exception of an unbuilt gap labeled “sito dove sta [?] lo casarino.”10

5 Maire Vigueur, 1976; Carocci, 1993b; Maire Vigueur, 2010, esp. 241–304.

6 It was described by Guido dei Nerli in a letter of 1462 to Barbara of Brandenburg (Archivio Gonzaga 841/624), published in Chambers, 1976, 43, Appendix 3. The palace is referred to as that of “Monsignor d’Avegnone” (Cardinal

Alain Coetivy, Bishop of Avignon), tenant at Palazzo Orsini at Campo de’ Fiori.

7 Francesco Albertini, ‘Opusculum de mirabilibus novae et veterae urbis Romae’, 1510, in Valentini and Zucchetti, 1940–53, 4.516.

Pl. 31

Palazzo Orsini, façade on Campo de’ Fiori.

Pl. 33

Palazzo Orsini, rear façade on Via di Grott a Pinta.

8 Please note that for ease of comparison to early vedute, most plans I use in this study are oriented to show the palace from the perspective of Campo de’ Fiori.

9 Published in Bentivoglio, 1995, 49. I thank Fabio Barry for pointing these out to me.

10 The palazzo was not, as Tomei states, razed for the building of Palazzo Pio. Tomei, 1939, 224.

and hardware needed to be replaced, a staircase needed refurbishing and the courtyard needed to be repaved.31 The only indication that there may have been other plans afoot for the palace was that, during his lifetime, Filippo Bernualdo senior also bought two houses attached to the north side of the theater (Pl. 133, Letter Q ). 32 It is possible that he already planned to gain control of the structure’s street façade. For the time being, however, the new houses were rented out for income.33 Over the course of the next century the Orsini continued to acquire more street-level properties around their palace,

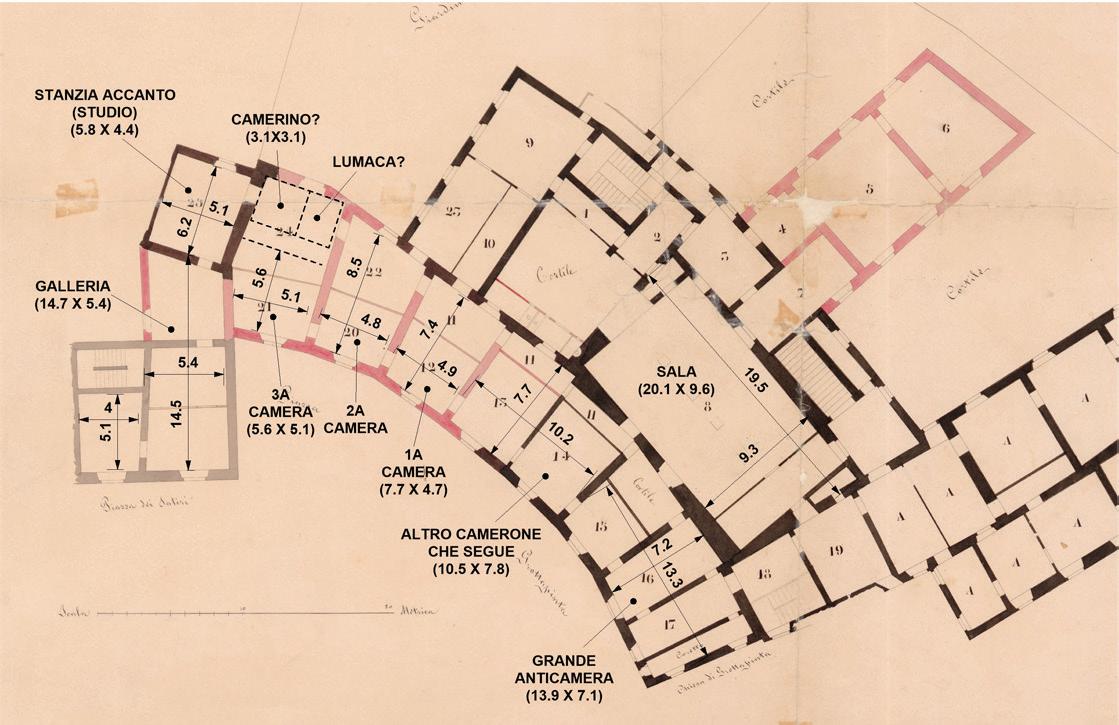

Pl. 133

Palazzo Orsini (former Palazzo Savelli), plan showing the use of rooms under its last Savelli owners.

rifarsi la selciata del Cortile, che è in cattivissimo stato, essendo la maggior parte devastata, accomodarsi le cucine, et officine; et accomodarsi diversi condotti delle fonti e chiaviche con diversi rappezzi; Che tutti i sudetti lavori di rappezzi e reattamenti come sopra, considerati, e scandagliati,

ascenderanno in circa alla somma di scudi 380.” Estimates were also given for carpentry, plumbing and painting. Orsini uClA , Box 260, Folder 3 (I.A xx , I.H .18), ff. 61r-64r.

32 An undated document details the arrangements for the payment for two houses bought by Filippo Bernualdo

– 155 –

Orsini from Niccolò Buti and Olimpia Ricci his wife. ASC , Orsini, Miscellanea Documenti Diversi, II .A .50.3. In the annotated plan (Pl. 133, Letter Q ) the houses are already marked as “spettanti al Sig.r Conte Buti oggi di S. A. di Grav[in]a,” i.e. already belonging to the Orsini.

33 They appear in a 1735 list of Orsini rental properties around the palace, ASC , Orsini, Miscellanea Documenti Diversi, II A .50.3, ff. 111–12. The house is identifiable because of the “forno ad uso di ciambellaro” on its ground floor. Compare this to two earlier documents: “Nota delle Case che sono nell’Isola del

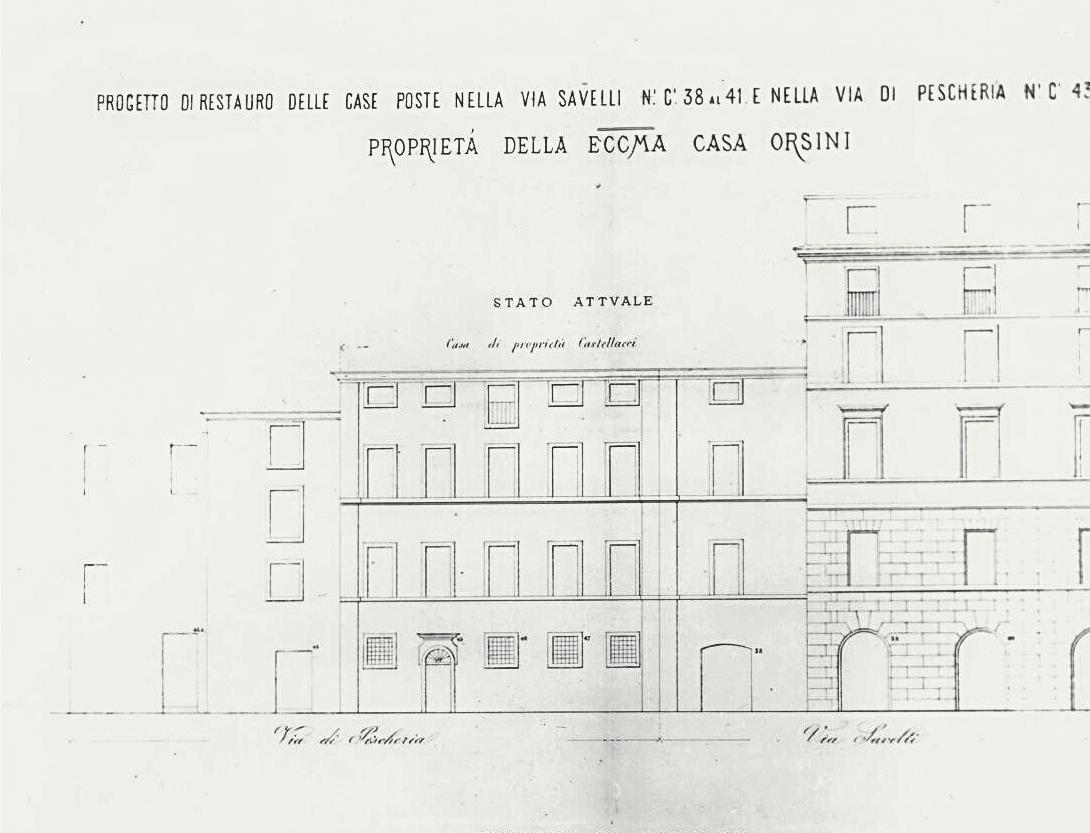

including most of a large block of houses south of the palace, which had belonged to the Maccherani and Caccia families (Pl. 133A and C ). The corner house, owned by S. Salvatore in Sancta Sanctorum and later by the Castellacci, was the only hold-out (Pl. 133B and 136).

Even before these houses were acquired, the Orsini had embarked on an ambitious project to redefine the appearance of the building as a whole. The entire palace, with all its multifarious forms and wildly varying heights, was wrapped in a uniform sheath which took as its starting point the opus isodomum base of tower D (Pl. 74 and 131). It was an enormous undertaking, and it took over a century to accomplish even in part. Some of the southern face of the building had already been refaced by the eighteenth century. The tower’s revetment had been expanded onto the adjacent wall to the east, and perhaps also onto a separate structure at the end of the east addition. It appears this way in an undated painting of the palace which must have been made some time after the Orsini’s purchase of the palace (Pl. 48). Then, in the following century, the treatment was extended to encompass the rest of the palace. By 1892 part of the new southern block of houses had been refaced (the old Maccherani property), but the small corner house was still in its old form. Evidently the Orsini were waiting to acquire the house, and even commissioned a renovation project with a new façade which would have incorporated both structures into the existing palace (Pl. 137). The owners, however, never relented, and the property still remains separate today.

Another significant addition was also made in 1823, on the occasion of the marriage of Domenico Orsini and Maria Luisa Torlonia — namely that of a new apartment attached to the front of the building.34 The new structure was installed in place of the final ramp that led to the palace’s main portal. The embankment

Palazzo Savelli colli nomi delle Persone che le possedono e pigioni di esse,” of 1 December 1721, in which: “Il Conte Buti possiede un forno da Ciammellaro con cinque stanze, ne ricava ogn’anno scudi 70,” ff. 54–56. Also in the same volume: “Piano delle Case ed altri siti spettanti al

Sig. Duca esistenti in Roma, ed annue Pigioni,” undated, in which: “Altra casa attaccata come segue con forno di Ciambelle che tutto resta dell arcate dell antico del palazzo. La casa è del Conte Butti,” ff. 98–102.

which supported the ramp already contained stables and storage areas, and sometime in the eighteenth century a portico was built in front of these, as is shown by an undated plan and elevation (Pl. 138 and 139). The drawings reveal the state of the fabric before the building of Domenico’s apartment, but after Federico’s pre1649 addition was already in place. The portico is visible, centered on the main entrance portal, and the ramp can be seen to its right. Domenico’s new apartment took the place of ramp and portico, and was massed so as to match Federico’s seventeenth century addition, creating a single block in front of the old defensive wall (Pl. 140). A new portico, similar to the old one, was built in the center of the combined blocks. The façade of the new structure was given the now standard opus isodomum treatment (Pl. 141).35

34 The new structure is described in:”Scandagli e Descrizione dei lavori eseguiti nel 1823 dall’Eccmo Sig. D. Domenico Orsini,” written later, in 1867. Orsini uClA , Box 99, Folder 8, 25 April 1867 (I.C.VII .22).

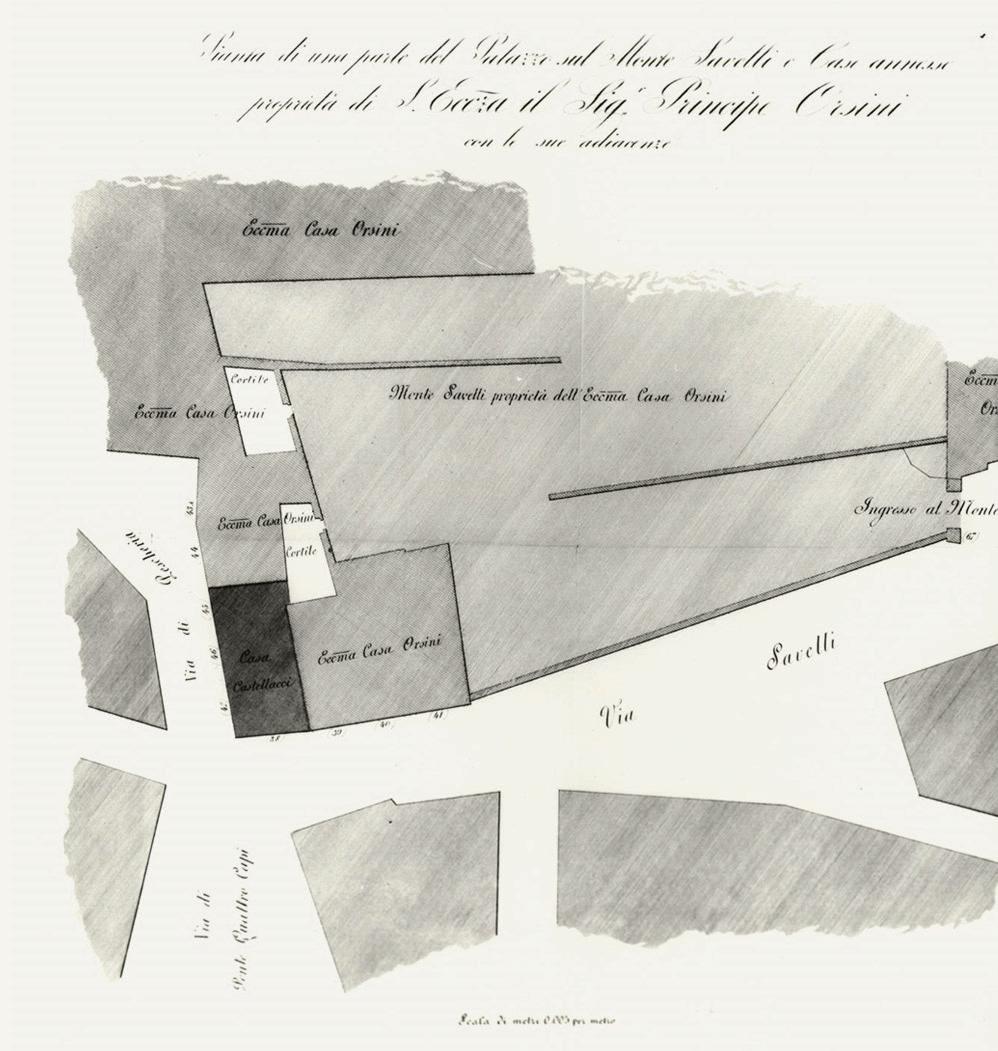

Pl. 136

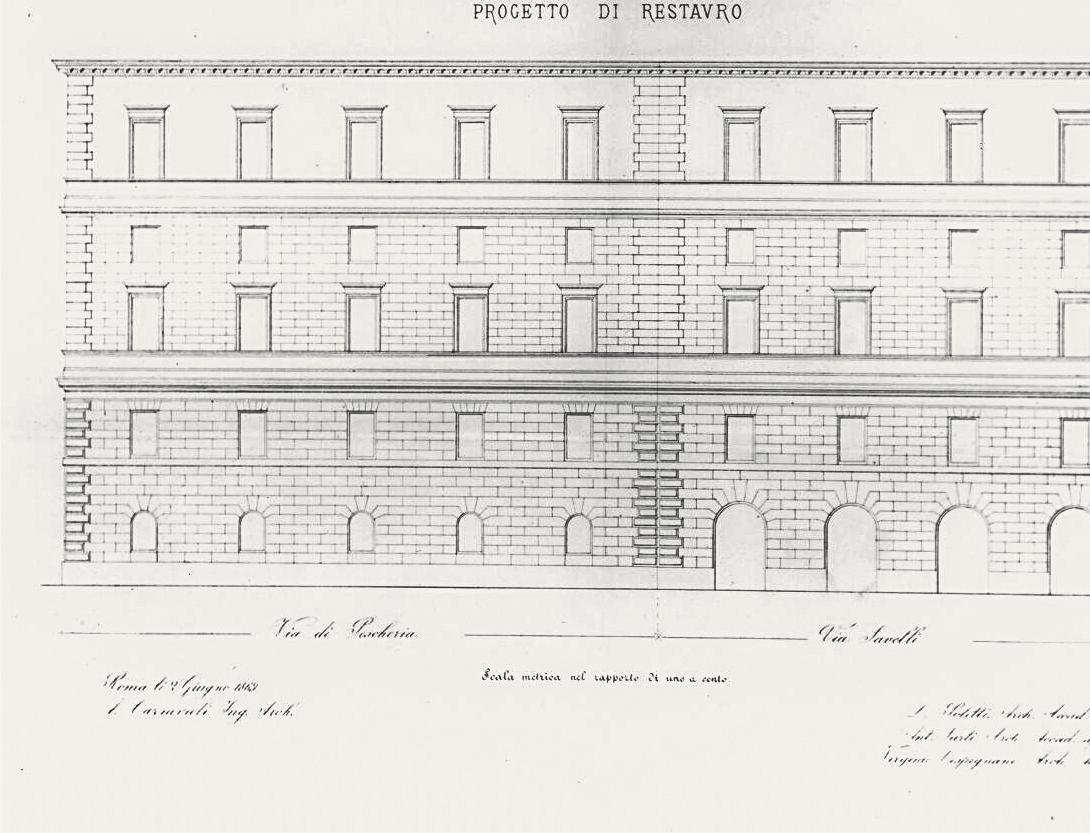

A. Carnevale (?), Palazzo Orsini (former Palazzo Orsini), plan of the south-west corner block showing the Orsini and Castellacci properties, c 1869?

Pl. 137

A. Carnevale, project to renovate the houses along Via di Pescheria and Via Savelli (the southern corner block of Palazzo Orsini (former Palazzo Savelli) and the Castellacci house), 1869.

35 The treatment is described as bugnato in the document: “[Domenico] dispose che questo portico fosse sostenuto da cinque archi … addossati al nuovo muro al quale è aderente, che avesse un zoccolo di travertino che fosse decorato di un bugnato e che questo proseguisse nelle

– 157 –

due ali a dritta e a manca, che fossevi una cornice all’imposta la quale pure ricorresse in tutto il prospetto … che ciascuna fenestra venisse decorata di mostra.” Orsini uClA , Box 99, Folder 8, 25 April 1867 (I.C.VII .22).

façade. As the plan makes clear, it was connected to the casino on one full side, and stood on high arcuated substructures similar to those which supported the east side addition. We know the appearance of its façade only from a print of 1690, since it was soon concealed by a further addition (Pl. 131). More formally ambitious than those of the two other additions, this structure’s façade was articulated horizontally with pronounced cornices, and vertically with flat pilasters which rose up through the parapet of a long terrace. Scrolls decorated the window openings.

It is unfortunate that we do not have more information about the addition of these two apartments: the sheer engineering challenge and amount of construction required by their substructures made them by far the most significant interventions in the building since the fifteenth century. The considerable investment the Savelli must have made in them reveals that the family’s priority in this period continued to be to increase the living space at the palace, to create room both for services and for formal apartments. It is telling that the family chose not to expand the building in height, or to increase the density of the structure within its footprint. Far from being consolidated as a regular, geometric block, the palace grew sprawling tentacles. The Savelli evidently preferred the considerable expense of building up the ground level in order to retain the building’s looser weave and the independence they clearly relished.

tHe SAle to tHe oRSINI, AND tHe ReDefINItIoN of tHe pAlACe

Giulio Savelli, the last member of the family to own the palace, died in 1712. Although he had a son, Bernardino, the son did not outlive his father. Giulio had, it seems, lived “more like a sovereign than a prince,” and sent an already cash-strapped family into headlong ruin.26 During his lifetime Giulio had been forced to sell several major feudal holdings, and when, at his death, he left his property to the Cesarini, the inheritance came burdened with 500,000 scudi worth of debt. The Congregazione dei Baroni confiscated Palazzo Savelli and sold it off to help repay the creditors.

25 The dates are those of Maggi’s 1625 view, and of a view of the south side of the palace by Giuseppe Tiburtio Vergelli (etching by Pietro Paolo Girelli), published in Rossi, 1690, 47.

26 See Litta’s notes on the life of Giulio di Bernardino Savelli. Litta and Odorici, 1819–82, vol. 10, fasc. 167–68.

The palace was bought in 1717 by Filippo Bernualdo Orsini family, of the branch descended from Francesco Orsini, first Duke of Gravina, builder of the Palazzo at Pasquino.27 In 1698 the Pasquino palace had been left by Flavio Orsini to his second wife, a formidable French woman by the name of Anne-Marie de la Trémoille.28 More than a decade of legal wrangling had failed to return the palace to the heirs of the title of Duke of Gravina, who were now based in Naples. The Gravina branch had, in the meantime, fared well in church, and prospects for the election of Cardinal Pier Francesco Orsini as pope were good. But if the papacy was going to be attained, the family needed a Roman seat to fulfill the “condizione di domicilio.” So says a short document of 1715, laying out the reasons for buying the palace.29 The arguments made in it ranged from the grandiose, including the supposed genetic ties between Caesar and the Orsini, to the practical: because the building was being sold by the Congregazione dei Baroni at auction as a repossession, it was likely to be cheap.

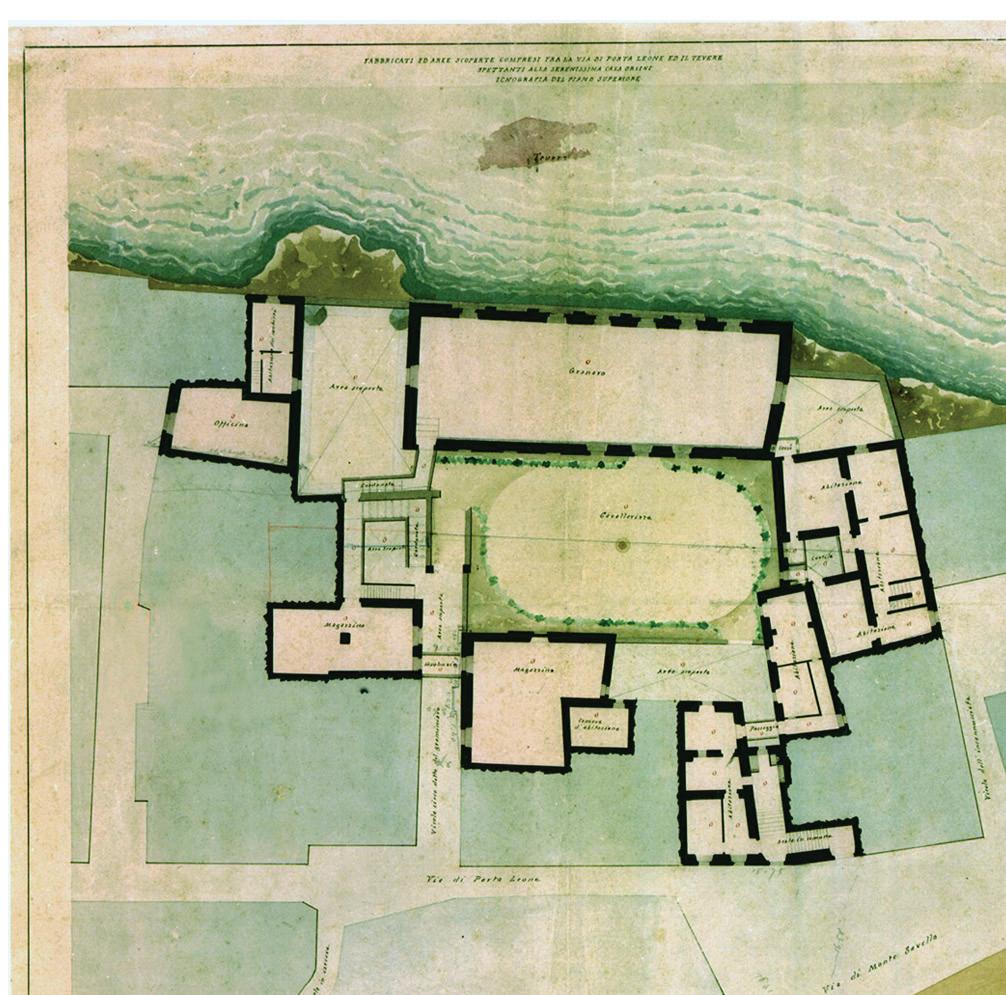

The earliest plans we have of the palace (those used up to now) date from this time, shortly before the sale in 1717 (Pl. 45 and 133). They show that at that time, Cardinal Paolo Savelli had the west side of the palace, with the garden, the adjacent hanging garden, part of the north wing (west of the shared sala), the wing between the garden and the courtyard, the new structure overlooking the Monte, and the casino della servitù. The east side was used by the lay side of the family (Prince Giulio and his wife), and included the rest of the north wing (east of the sala), the wing east of the courtyard, and the additions along the east side of the Monte. There were also separate stables across the way — called Le Cento Finestre — which were shared. These stables had been part of the palace since at least the sixteenth century.30 They survived until the late nineteenth century, but were destroyed when the massive embankments of the nearby Tiber were built. An excavation has revealed their remains below the current street level (Pl. 134 and 135).

Upon buying the palace, the Orsini drew up a list of necessary miglioramenti to be made there. The concern was entirely with restoration: all the roofs needed to be repaired, most of the doors, windows

27 See Appendix 4. On the palace under the Orsini di Gravina see Benocci, 1984.

28 Castiglione, 2008.

29 See Appendix 3.

30 They are mentioned in a document of 1544. See ch. 4, n. 72.

31 8 March 1717, estimate of the construction work to be done on the

– 154 –

palace. “Per i lavori spettanti all’opera, e fattura di muratore, si trova aver di bisogno essere riattati tutti i tetti di detto Palazzo, essendo sporchi, e con quantità di tevole, e canali rotti, accomodarsi la cantonata verso Piazza Montanara della scaletta, che cala alle cucine, la quale ha patito, e minaccia rovina; accomodarsi

tutti gli ammattonati, con farli diversi rappezzi d’ammattonati rotati, e tagliati, et alcun altri più ordinari; diversi rappezzi di spicconature, ricciature, e colle stuccamenti de lugli; mettitura in opera, e muratura di diversi telari, che si dovranno rifar di nuovo per esser cattivi, et alcuni che non vi sono;

Pl. 152

Palazzo Orsini a Campo de’ Fiori, conjectural plan showing the state of the palace at the end of the seventeenth century (courtyard and piano nobile). Annotations refer to the spaces identified in Orazio Torriani’s description (Appendix 8).

Pl. 153

Partial plan of Palazzo Pio-Righetti (former Palazzo Orsini) at Campo de’ Fiori, piano nobile, 1851, showing room dimensions compared to those given by Orazio Torriani (see Appendix 11, translated into meters, noted in parentheses).

by its own external stairs from the courtyard (L), and its suite of rooms included the newly created space in the old tower (D) and the room in the palazzetto (J5) (now evidently incorporated into the palace), as well as camere on the north side of the wing. A terrace overlooking Campo de’ Fiori gave it an exterior outlet (J6).

A third formal apartment, this one for the use of women, was one story up.107 It had been newly created by Paolo Giordano II with every amenity one could desire, Torriani says, including its own kitchen. Above that, under the eaves, was a very large guardaroba, which spanned the entire wing from the church to the tower.

Service quarters for the lower staff were on the ground floor, directly off the courtyard.108 Those for the upper staff occupied the third and final wing of the palace (P), which ran diagonally southeast from the tower and continued along Via dei Giubbonari.109 Due to its use, this wing had rooms connected by a corridor rather than an enfilade. The service wing was linked to the cardinal’s apartment by a covered wooden corridor (Q) — a structure which also separated the courtyard from the garden. (I).110 The garden was planted with fig and bitter orange trees, and featured an aviary, a fountain, a well and laundry facilities.

The wooden corridor linking the cardinal’s apartment and the service quarters must have been a less than ideal solution to what apparently was once a serious problem of indoor circulation at the palace, or at least so Torriani’s text suggests. Again and again in his description Torriani stresses the ease of circulation in the palace, assuring the reader that the apartments were now entirely independent, and could comfortably be reached via multiple stairs, several of them newly built. One of these stairs, in fact, was added as part of Sacchetti’s rental; it was at the north end of the loggia, opposite the new ceremonial stair at the south end.111 The source of the circulation problem, we can guess, was that originally the building was conceived as a series of separate houses, which communicated only via outdoor communal spaces. This arrangement was not practical for the functioning of a formal seventeenth-century palace, where men, women, servants, and people of different social standings were all expected to live in separate spheres, intersecting only in controlled ways and in appropriate locations.

The miglioramenti made by Paolo Giordano II and Torriani suggest what must have been their main concerns for the building. Aside from essential repairs, the first priority was to add usable space. The palace was expanded both by building new structures, and by converting and incorporating old ones that had been used separately. Torriani also strove to make appropriately articulated

apartments: ones that were long enough and had amenities suitable to their inhabitants, such as the totally independent apartment for women.112 Other priorities included improving circulation — with the addition of several stairs — and increasing the comfort of the spaces, for instance with the creation of the double enfilade. Finally the duke and his architect made a major effort to improve the palace visually, especially by giving it unity. This posed the challenge of knitting together the existing structures with those newly built or newly converted. In this respect Orsini was dealing with an old problem, since the complex had undergone centuries of additions, but such a concerted effort toward coherence was a new impulse. Efforts toward this goal included the beginnings of a new exterior façade, improving the courtyard façades, and substituting the antiquated out-door cordonata with a formal interior staircase.

Paolo Giordano II’s miglioramenti were of a different order than those of his recent predecessors, driven by a bolder and more comprehensive vision for the palace than the improvements of the previous century. Accomplishing such a vision required a much greater financial commitment than earlier, more limited efforts, and Paolo Giordano II approached the problem though the use of creative financing. This involved compromises on ownership, agreements with neighbors, and loans from his tenants. Oblique strategies for improving the palace were not new to the Orsini, but Paolo Giordano II took them to a new level. The results of his efforts were mixed. Though he was able to accomplish a great deal at the palace, his failure to rebuild the houses of S. Lorenzo in Damaso and S. Maria sopra Minerva suggest that he may have bitten off more than he could chew. In fact, these were not the only projects he was unable to fulfill.

miglioramenti oNly ImAgINeD:

uNReAlIzeD pRoJeCtS

The duke, it turns out, had a more ambitious plan for improving the palace exterior than just the north façade on Piazza del Biscione. A 1641 drawing by Torriani shows that he also hoped to

107 Appendix 8.9.

108 Appendix 8.3.

109 Appendix 8.10.

110 Appendix 8.11 and 8.5.

111 “Fare una schaletta di peperino, che cominci nella stanza in testa alla loggia a piano del forno, e vadi all’ultimo

regularize the façade of the palazzo on Campo de’ Fiori, by continuing the line of the palazzetto and squaring the corner at Via de’ Giubbonari (Pl. 154). Torriani’s drawing gives no hint as to the proposed elevation, but establishing a new street front would have required creating an entirely new façade for the building, presumably one that matched the one begun on the north side.

Far more revealing than this already ambitious project, is evidence of an extraordinary plan for the palace. We know of it from a proposal submitted to Paolo Giordano II by a certain Finugio,113 probably identifiable as the architect Girolamo Finugio, a rather distinguished architect connected with the planning of St. Peter’s in the same period.114 The document is actually a cost analysis of Finugio’s proposal, balancing the expense of executing the changes at the palace against the increase in rental earnings these changes would offer. The plan involved carving up the old complex and running a public street through its center. The street would have entered just south of the old tower, cutting through the courtyard and garden, and exiting at the other end of the complex, near S. Barbara.

The main advantage of such a drastic operation was the creation of forty shops along the new street, each yielding 40–50 scudi in rent, plus a number of other rentable spaces. The document alludes to several variations on the project that were under consideration. Though now lost, we know they included one submitted by Torriani, and another by a certain Signor Angelo. The writer of the evaluation favored a plan slightly different from Finugio’s — one which would do away with the garden completely, and make the courtyard into a public piazza. This, he wrote, would reduce the number of shops by eight, but it would increase the amount at which the palace could be rented from 800 scudi to 1,000. He added that in any case the plan was likely to be even more profitable than it might seem, because it would improve the palace as a whole, and make it easier to rent.

This extraordinary proposal to run a commercial street through the Campo de’ Fiori complex raises once again the question of the Orsini’s intentions for the palace. Paolo Giordano II was certainly committed to improving his ancestral palace, but it is clear that he saw his work on the palace largely as an investment

appartamento sino a piedi della scala della guarda robba.” Appendix 7. There was already another stair on the opposite side of the loggia (the new formal stair); we know that the loggia had stairs on both sides because Torriani refers to the “due scale che stanno per

– 175 –

le due entrate della detta loggia.” See Appendix 8.9. The oven which was converted into a kitchen was next to the new stairs at the north end, and there were also new structures here, since the contract refers to a “fabrica nuova verso il forno.” Appendix 7.

112 Waddy, 1990, 26–27.

113 Appendix 9.

114 See McPhee, 2002, 11, 296, 319–20.

This book is an exploration of the layers of Rome: the accumulations of centuries of habitation that make the city a fascinating and sometimes confounding palimpsest. This architectural coexistence is perhaps most nakedly on display at the sites of the ancient theaters of Marcellus and Pompey. Here ancient, medieval, early modern and contemporary elements are interwoven in a way that produced some of the strangest buildings in Rome.

Drawing on archival sources, pictorial records and physical evidence, this book untangles the rich history and fabric of these buildings. It starts to trace their evolution from the fall of the Roman Empire, when the city’s public monuments were taken over by private owners and the theaters were first used as simple shelters. It follows the theaters as they were taken over by powerful Roman families in the Middle Ages, and transformed into fortresses which dominated the urban landscape. And it examines the structures’ continued evolution, as defensive needs were replaced by the desire for more elaborate living spaces, and eventually the requirements of the formal aristocratic palace.

This last transformation posed the greatest challenge for the buildings and the families that inhabited them. The Tuscan palace was a highly desirable model but in many ways was incompatible with the massive, radial theater remains. The choices made by the owners in response to this problem are in many ways surprising, and shed light on overlooked aspects of patronage and palace-building. Eschewing badly needed formal improvements, the families focused primarily on enhancing the experiential aspects of their palaces. Their approach shared by some of their contemporaries, pointing to a plurality of practices in the conception of the palace.

This book offers an alternative perspective on Rome’s ancient remains: a material history which enriches our understanding of Rome and its antiquities, and illuminates aspects of baronial patronage, social identity, and even the palace itself.

HARVEY MILLER PUBLISHERS