‘Narrating’

‘Narrating’

British Inventiveness on the Grand Tour

1760–1800

Claude Beaulieu Orna

VII. Reinventing Modes of Disseminating Skills

From

Aquatint: an ideal mode of dissemination

From empirical assay to aesthetic expansion: Grand Tour landscapes in aquatint

Aquatint: a process for interpreting British landscape?

From the Sketch to the Illustration: ‘Narrating’

VIII. Sharing Travel Experiences

Collecting

Collecting

IX.

intended for landscape portrayal.8 An artistic education that immediately veered towards depicting the landscape was thus a shared, fundamental, and distinctive characteristic of Grand Tour British landscapists.

The experience of the Grand Tour was primarily intended to perfect the early training of these landscapists, though some may have had different or further reasons to travel. Before leaving Britain, several promising landscapists had already been awarded distinctions within their respective schools. Crone, Delane, and Forrester were honoured with a drawing prize at the Dublin Society School of Drawing;9 Dean, Garvey, Jones, Pars, Robertson, and Towne were all laureates of the Society of Artists.10 These painters often perceived the trip to Italy as the culmination of this learning period. In addition to completing training rudiments, Irish and Scottish painters came to admire paintings of great masters in Italian art collections; they often copied them in order to have a better understanding of traditional art. English ‘provincial’ painters did likewise, after having discovered the art of these masters essentially through prints.11 As accomplished and renowned a painter as he was, Wright of Derby also participated in the Grand Tour to perfect his skills in landscape painting. At the beginning of the 1770s, having discovered with great interest the teaching methods of Alexander Cozens, he decided to undertake a similar practice.12 Anticomania, highly popular at this time, also inspired Wright of Derby as well as many other painters: they came to see and draw the main vestiges of ancient Roman civilisation (Fig. 2).

Fully trained or not, others left home with the firm desire to explore new markets, an objective that often led them to settle longer or even permanently in the Peninsula. During the last third of the eighteenth century, fifteen of the British landscapists listed above made trips of a short or moderate duration, lasting between one and a half to five years, while nine others settled in Italy. These expatriates were all Irish or Scottish, with the exceptions of Patch, who came from Devonshire, and Pars, the son of a Dutch carver established in London. This seems to be explained by a less extensive art market in Ireland and Scotland, which motivated some landscapists to move abroad to make a living from their art.13 Rome and the papal seat became an appealing alternative to London, all the more since the presence of the Young Pretender to the throne of Great Britain, Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720–88), attracted a rich clientele sensitive to the Jacobite cause.14 The trip to Italy seems to constitute an option, at least initially, to pursuing training at home or to trying a career launch in the English capital. In turn, Patch took advantage of the opportunity that arose, following the death of the illustrator Giuseppe Zocchi (1711–67), to appropriate the flourishing market of the Florentine vedute. 15 Fi nally, the prolonged exile of Pars was, one might think, partially due to personal reasons: he left England accompanied by another artist’s wife.16 Whether they planned on staying for a short or

for an extended period, British landscapists were increasingly attracted by the experience of the Grand Tour.

Above all, this group of artists belonged to the same extended generation: they were, save for a few exceptions, all born between 1735 and 1770, and began their professional life between 1755 and 1790. This last interval corresponds to a pivotal period in the history of landscape painting in Britain. Indeed, a system to standardize teaching methods and to promote contemporary art was being developed; new aesthetics were emerging whilst traditions continued to be appreciated; landscapists progressively exhibited remarkable inventiveness in their art. All circumstances coincided to bring greater recognition to the genre and to please the ever more cultivated connoisseurs.17

Until the end of the seventeenth century, it could be said that there were no official institutions providing arts education in Britain, nor places or events dedicated to the public presentation of works of art. The Worshipful Company of Painters and Stainers, for which a first documented reference dates back to 1283, acted in lieu of a representative trade body, assimilated more to a guild for craftsmen than to an organization for professional artists.18 During the last decade of the seventeenth century, two structures were created that contributed to forming the basis for an educational system: first, auction houses, where exhibitions and the trade of ancient and contemporary art took place; and secondly, the first drawing classes, at Christ’s Hospital as well as at the school of Bernard Lens II (1659–1725) and John Sturt (1658–1730).19 Parallel to these factors was the emergence of art circles and private academies. The whole constituted the embryo of what Ilaria Bignamini designated as an ‘institutional system for the arts’.20

The first milestones of this system closely intertwined the life and interests of professional artists with those of art lovers. They both frequented a network of clubs and societies, such as the Rose and Crown Club or The Virtuosi of St. Luke.21 At the same time, places like Vauxhall Gardens and the Foundling Hospital, which artists were engaged in decorating, lent themselves to a simulacrum of an artistic exhibition hall. On to this initial core were gradually grafted some private academies more specifically aimed at training artists, ‘designed, established, ruled, directed and supported by the artists themselves’.22 The Academy in Great Queen Street directed by Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) was one such example. However, the education provided was poorly supervised and relied heavi ly on emulation between young apprentices. Noticeably, out of nearly one hundred painters attending Kneller’s academy during its existence (1711–20), only two were landscapists.23

As time went on, following various initiatives from artists, teaching structures tended to dissociate professionals from amateurs. In the winter of 1735, William Hogarth (1697–1764) resumed the interrupted activity of St. Martin’s Lane Academy to make it the principal, but not the unique, educational institution for the arts between 1735 and 1768. His objective in doing so was to instruct exclusively young people intending to work as professional artists.24 This was also the case for the three institutions that emerged between 1740 and 1760 in Dublin (Dublin Society School for Drawing and Design, 1742), Glasgow —-1 —0

belonging to this first sketchbook demonstrate his great ease in graphic technique while the smaller number of ink sketches indicate a degree of experimentation.

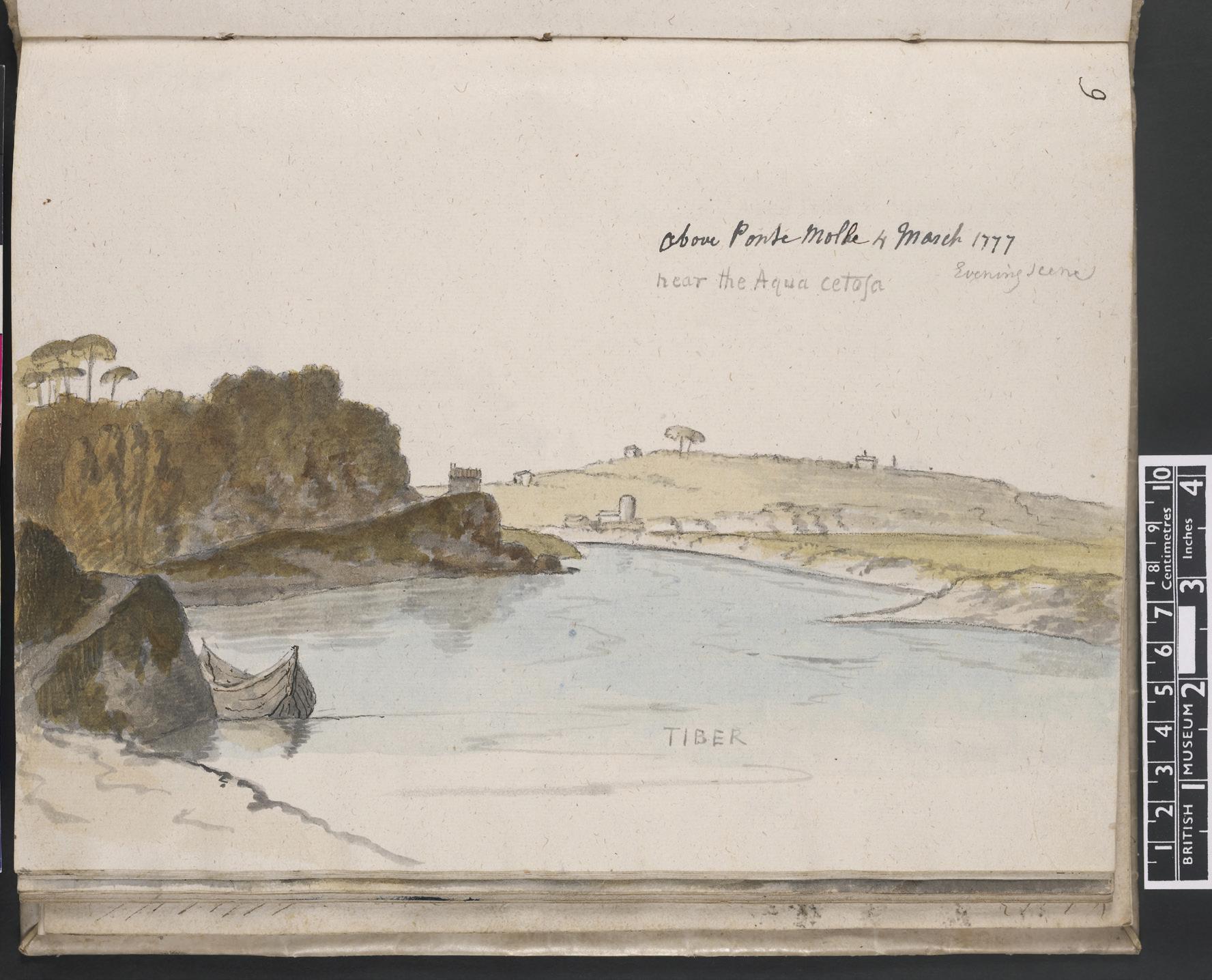

The second sketchbook marks a turning point towards technical experimentation. It comprises more than twenty watercolour sketches out of a total of thirty-eight drawings. Jones outlined forms in pencil, annotating colours here and there, before applying watercolour with a brush. A systematic recording of the date and place on the drawings recalls Malchair’s recommendations.85 The succinct contours and the limited palette of these drawings suggest that they might have been sketched out of doors, while others, more refined, might have been completed afterwards (Fig. 36). Jones returned to his usual drawing technique in the third travel sketchbook in which graphite outlines are preponderant.

Spurred on by the setting of the Bay of Naples, the artist developed his interest in drawing panoramic views: this is demonstrated by the six sketches on double pages of the sketchbook kept at the National Museum Wales.86 Jones adapted the materiality of the exercise of sketching from nature to the needs imposed by visual perception.

Travel sketches were therefore an opportunity for Jones to look at the urban and rural landscape from a different angle, trying to grasp its essence in trivial ‘properties’. Sketching from nature was also aimed at experimenting with uncustomary drawing techniques and formats.

As Jones exemplifies, the variety of drawing techniques in travel sketchbooks and first impression drafts reveals a sense of adaptability, both to situation and to intention, as well as an aptitude for experimentation. Towne, Cooper Jr., and Edward Swinburne also sought to find the technique best suited to rendering their visual impressions on paper. Hitherto unused skills were implemented in order to depict subtleties of natu ral scenery defined by light and chromatic effects. Their watercolour drawings demonstrate that, from the 1770s, the consideration of proper colour, generated by reflections and lighting, as opposed to natu ral colour became increasingly impor tant in the study of landscape.

Of all the British landscapists participating in the Grand Tour, Towne was certainly far and away the one who most notably blurred the distinction between a sketch and a completed artwork. At first glance, the artist’s alpine sketches appear to be thoroughly finished works. However, almost all of them show on their verso the handwritten note ‘drawn on the spot’, suggesting that they are in real ity sketches. Indeed, Towne completed his works by applying watercolour directly on his initial out- of- doors sketches.87

The artist’s method of execution can be extrapolated from a detailed examination of the contents of the sketchbooks. Towne seemed to be able to compose the mountainous landscape he observed directly: he drew the striking features—lines and masses—of the scenery in pencil or pen. As Gilpin underlined, certain painters could ‘by Genius guided, mark the general form, the leading features, which the eye of Taste practised in Nature, readily translate’.88 Towne then inscribed factual details, providing information about the out- of- doors session: the date, location, angle of view, and specific conditions of natu ral lighting, such as ‘light coming from the right’, were specified.89 It was impor tant for him to prove he was sketching in situ. Fi nally, he assigned a sequential number to each sketch and indicated if it was done ‘on the spot’ or ‘after Nature’. This initial sketch was later completed by applying gradated ink washes or watercolour hues with a brush. On rare occasions when this seems to have been done in open air, Towne would indicate ‘drawn & tinted on the spot’, as for the portrayal of Monte Porzio from the Villa Mondragone, Frascati 90 This colour application was much more likely to have been executed sometime later, when the artist returned to his inn. Towne applied washes or watercolours directly on the medium, at the same time leaving occasional spaces of blank white paper, as can be seen in On the Lake of Como (Fig. 37). As a last step, the landscapist went over the initial pencil or pen outline using a pen with bistre or brown ink. He scraped the paper, probably using the tip of his pen, to remove pigments in isolated places, as can be seen in the clouds and along the mountain ridge.

During a single excursion, Towne, through a technique that effectively combined study and completed work in one, aimed at giving the most authentic character to his depiction and expressing the immediacy of the recording on paper. Indeed, his technical choices all suggest that his drawings were done rapidly; moreover, his daily creation rate of such works seems to confirm this.91 Paradoxically, at a time when colour was becoming essential to the sensitive expression of landscape, Towne’s highly personal style, giving precedence to drawing over painting, was going against the tide.

Fig. 37. Detail of Francis Towne, Lake of Como, 1781, pen, ink, and watercolour, 15.6 × 21.2 cm, London, Tate Gallery (Small Sketchbook: Northern Italy, Switzerland, Savoy and Germany)

Richard Cooper’s album of sketches of Italian landscapes is a tangible witness of his desire to experiment with the materiality and techniques of travel drawing.92 Its eclectic content explicitly demonstrates the insatiable curiosity of the artist during his eight-year stay in Italy in the 1770s. Son of his first master, the eponymous Edinburgh engraver, Cooper Jr. completed his training as an engraver in London before attending the studio of Jacques-Philippe Le Bas (1707–83) in Paris. He was soon introduced to contrasting artistic approaches. His album contains very different types of drawing, executed on loose sheets and presented randomly: sketchy drafts in graphite pencil and/or in pen (Fig. 38); more elaborate landscape studies, probably drawn from nature in graphite; landscape sketches in ink and wash, with a very lively touch (Fig. 39); copies of drawings by old masters (Fig. 40); studies inspired by the imaginary prisons of Piranesi; a landscape study portraying the sunset, done directly and entirely in watercolour (Fig. 41); etc. Similarly, a variety of types of paper serve as substrates for these heterogeneous sketches: white writing paper, blue packaging paper, and ivory medium textured cut sheets, etc. Some drawings have an almost square format; others stretch across a narrow horizontal strip; others correspond to the so- called ‘landscape’ format. Some occupy an entire page, others share a single page. Cooper used red, black, and white chalk, graphite, black and brown ink, wash, watercolour, and gouache.

Fig. 77. William Marlow, Rome from the Tiber: St. Peter’s and Castel Sant’Angelo, c. 1765, pencil, blue, grey, and pink washes, 90.0 × 124.5 cm, UK, Government Art Collection (Rome, British Embassy)

Fig. 78. John Melchior Barralet after William Marlow, Rome, View of Castle St. Angelo and St. Peter’s Church, 1784, etching and aquatint with hand colouring, 40.5 × 57.0 cm, UK, private collection

Barralet’s print after Marlow was no exception at the end of the century: the growing demand for engravings designed for decorating interiors established a new market for coloured reproductions.63 In response to this fashion for large-format, coloured facsimiles, like View of Castle St. Angelo and St. Peter’s Church, which measures 40.5 by 57.0 cm, engravers preferred to interpret creations of acclaimed painters of the Grand Tour. Jacob More, Andrew Wilson, and Louis Bélanger (1756–1816) had prints executed after their work once each had established their reputation in the British artistic milieu: More, then deceased, was still celebrated in Rome as in London; Wilson was a former student of the renowned Nasmyth; and Bélanger had made a name for himself among the London vedute painters.64 Two main reasons may explain this choice. On the one hand, such prints were hung on walls of upper- class mansions instead of renowned masters’ pictures, sometimes too difficult or too expensive to obtain.65 On the other hand, the subjects and composition of these sublime or picturesque views easily lent themselves to decorative purposes, responding to an aesthetics that took the viewer’s perception more into consideration. In addition, the choice of aquatint was also dictated by a desire to imitate the plastic effects of the original work. Hence in 1800, John William Edy (1760–1820) used aquatint qualities to render the sublime atmosphere of More’s depiction of an eruption of Vesuvius (Fig. 79).

The intense colours and accented contrasts of the print executed after this night scene are fundamentally reminiscent of More’s pictorial light effects.66 Of Danish origin, Edy had

Fig. 79. John William Edy after Jacob More, Eruption of Vesuvius at Night; Boat and Two Men in the Foreground, 1800, aquatint, 45.0 × 60.9 cm, London, Wellcome Collection

moved to London at the end of the century and mainly engraved topographic views; he illustrated certain works for the publisher Boydell.67

Aquatint associated with hand colouring was often chosen as a method for producing decorative prints because of its ability to enhance both landscape depictions and their pictorial techniques. Satisfying an increased demand for high mountain images, aquatint facsimiles of B élanger’s alpine views in gouache were created by several London engravers.68 Among the pioneers to test aquatint in the 1770s, Francis Jukes also participated in illustrating Gilpin’s works.69 Trained in Leipzig, Maria Katharina Prestel (1747–94), a German, worked in London from 1786 and engraved amongst others several alpine landscapes by Bélanger.70 Apprentice in Copenhagen in the studio of the history painter Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard (1743–1809), Simon Malgo (1745-after 1793), a Dane, travelled extensively in Europe in the company of the landscapist Jens Juel (1745–1802) before emigrating to England; he was particularly known for interpreting Juel’s views of Switzerland.71 Like Malgo, Jacques Mérigot (1760–1824) moved to London in 1791 and quickly gained fame as an illustrator, working with ‘Warwick’ Smith for instance.72 Although they came from various backgrounds, they all shared the same predominant interest in interpreting landscapes.

Taken from a series engraved after Bélanger’s gouaches, the aquatint A View of the Loss of the Rhône was executed by Prestel in two versions, one in grisaille and the other in colour (Fig. 80). The grisaille print clearly configures Bélanger’s composition, which is defined by light effects on large masses, meanwhile preserving the precision of delineated motifs such as leaves. A line engraving process would not have allowed such a fine rendering nor such an effective juxtaposition of flat tints and contours. Prestel’s tonal aquatint even evokes Bélanger’s highlights of white gouache on rock walls and at the top of waterfalls. The coloured version offers a convincing chromatic and plastic interpretation of Bélanger’s mixed technique using watercolour and gouache. Compared to the original gouache work, this interpretation could be displayed with much less fear of alteration by the ambient light.

Like alpine scenery, Grand Tour emblematic landscapes were fash ionable subjects for engravings of a decorative nature. With great proficiency, Frederick Christian Lewis the Elder (1779–1856) interpreted Andrew Wilson’s wide-angle watercolour view of Tivoli using aquatint.73 After what appears to be one of his first aquatints, Lewis would later interpret works by Thomas Girtin (1775–1802) and engrave a plate from Turner’s Liber Studiorum (1807–1819).74 Examination of the print reveals the subtlety of chromatic nuances and the fine shifting lights by virtue of Lewis’s masterful work, which brings this interpretation close to the distinctive qualities of Wilson’s tempera paintings. Such attractive chromatic rendering might have caused Horace Walpole to proclaim by the end of the century that ‘engraved landscapes have in point of delicacy reached unexampled beauty’, in this way confirming his earlier statement underlining the fact that ‘want of colouring is the capital deficiency of prints’.75

Evidence shows that decorative aquatint prints were not the only coloured engravings to portray Grand Tour scenery; however, they played a prominent role in communicating British landscapists’ inventive technical skill. Indeed these coloured achievements are to be compared with previous engravings by Louis Ducros and Giovanni Volpato (1732–1803). In the early 1780s, Ducros combined his virtuosity with that of the renowned Italian engraver Volpato to create watercoloured views of sights popular with Grand Tour visitors. Volpato,

Displaying travel portfolios from unsuccessful editorial projects

Some professional landscapists acted as draughtsmen on expeditions in order to record scenery for an illustrated travel account. Indeed, for certain travellers, such a project came to acknowledge the Grand Tour as an accomplishment and was a sought-after sign of high social rank. The proliferation of works by Gilpin on picturesque travels also encouraged initiatives in which an ability to appreciate natu ral and artificial landscape could be demonstrated.1 However, despite having received artistic training, this type of visitor did not always have the graphic skills required to sketch landscapes easily. For these reasons, some patrons depended on the virtuosity of an artist. Within the framework of the Grand Tour, shorter excursions or brief tours also developed, which lent themselves to illustration. British patronage was responsible for three-quarters of these excursions.2 Furthermore, seventyfive percent of these small excursions took place in the Neapolitan and Sicilian regions, which were still a novel attraction for a good number of travellers at this time.

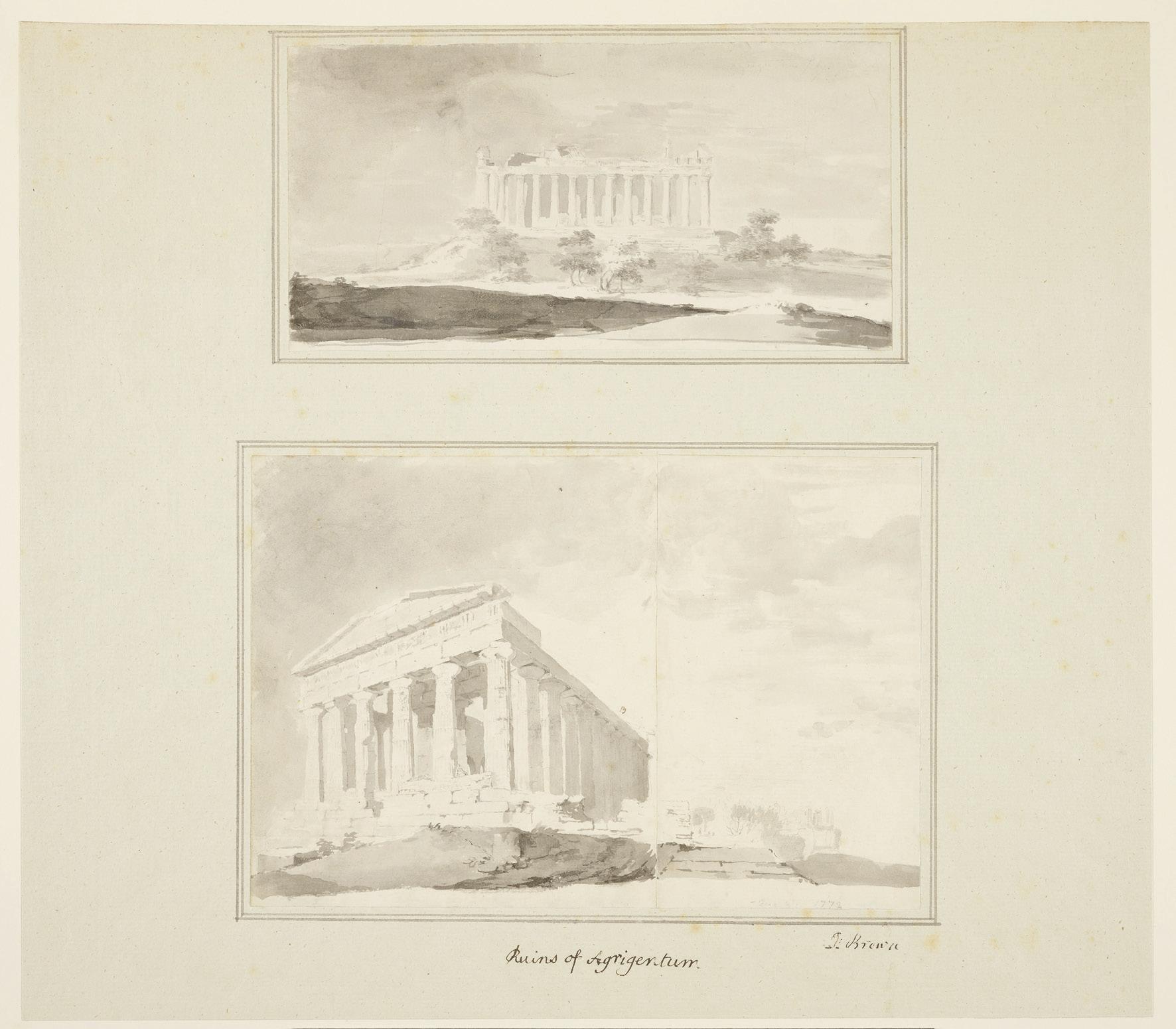

Visiting the vestiges of ancient Magna Graecia and climbing volcanoes were highlights of these excursions. Some reference guides were available to help prepare those intending to travel to the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. The most well known, by Johann Hermann von Riedesel (1740–84) and Patrick Brydone (1736–1818), had already been translated into various languages. Italian scholars had also described principal ancient sites in travel literature.3 Apart from Breval’s Remarks, none offered illustrations of landscapes or ruins, hence the desire of some travellers to be accompanied by landscapists for their circuit in Sicily. William Young (1749–1815) and Richard Payne Knight were two such travellers in the 1770s. In 1772, Young and John Brown, a landscapist, were among the first to ‘narrate’ the landscapes of southern Italy. At the end of June, both embarked for Sicily and thence for the island of Malta. Whilst journeying in these islands, Young wrote A Journal of a Summer’s Excursion by the road of Montecassino to Naples, and from there over all the southern parts of Italy, Sicily and Malta, in the year 1772. Around 1774, the text was printed in London in a limited edition of only twenty copies.4 Contrary to what seemed to have been planned initially and without any explanation, this publication did not include any illustrations.

Young’s illustrated voyage therefore took the form of a text that lacked illustrations and was accompanied by wash drawings that were never engraved.5 Nevertheless, examination of some of these travel sketches and an analysis of the narrative both suggest that the editorial project originally planned to include plates from a selection of Brown’s drawings. Some sketches seem to have been done to facilitate a potential work of interpretation: accustomed to landscape drawing in graphite pencil, Brown resumed using washes to mark tonal values (see Fig. 85). Furthermore, Young specified in his narration that he did not intend to expand on detailed descriptions, since ‘following dif ferent Sketches thereof, will supply a much more perfect Idea’.6

Interestingly, Young envisaged sketches, and not completed drawings, as images sufficiently expressive and worthy of publication. At the beginning of the 1770s, illustrating a journal with sketches would undeniably have been an innovative aesthetical approach. By resorting to interpretations of studies carried out in situ as illustrations, not only did the author release the reader from tedious descriptions but he confirmed the very authenticity of his narration. The intention was also to demonstrate the ‘genius’ of the draughtsman, who, with an economy of means, succeeded in expressing the unique majesty emerging from the site of Agrigento as well as its starkness. In short, this limited- edition