Painting Architecture in Early Renaissance Italy

Innovation and Persuasion at the Intersection of Art and Architectural Practice

Livia Lupi

harvey miller publishers

Chapter 1

A New Architectural Consciousness

Masolino da Panicale at Castiglione Olona

Masolino da Panicale was a successful Florentine artist, who had worked on major commissions in Florence and Rome by the time Cardinal Branda Castiglioni invited him to carry out work in Castiglione Olona, Branda’s hometown. Located on high hills north of Milan and close to Lake Maggiore, Lake Como and the Alps, Castiglione Olona is to this day little more than a hamlet. There, in the mid- to late 1430s, Masolino painted the life of St John the Baptist in the baptistery and the life of the Virgin in the vaults of the collegiate church’s choir chapel, later completed by Lorenzo di Pietro (known as Vecchietta) and Paolo Schiavo. The arrival of Masolino and his workshop must have been a particularly exciting opportunity both for the Tuscan artists to explore the artistic production of this region of Italy, and for the locals to engage with an approach to painting that was completely novel in Lombardy at the time. More specifically, Masolino’s work in Castiglione Olona’s baptistery stands out for its prominent architectural settings, which propose a variety of structural and decorative solutions engaging with classical heritage. Whilst an all’antica approach was already relatively well established in Florence, where Masolino had collaborated with Masaccio, arguably the most innovative painter of the early fifteenth century, it was ground-breaking even for major centres like Milan, and even more so for a small town like Castiglione Olona.

By commissioning Tuscan artists to decorate the town’s main church and baptistery, Branda Castiglioni was making a statement. A well- educated prelate who had risen to great prominence and who could boast an impressive international network,1 Branda was demonstrating his awareness and endorsement of the latest artistic developments taking place in Florence, attempting to turn his small native town into an up-to-date centre of cultural prestige.2 This chapter argues that Masolino’s frescoed architectural settings for the baptistery played a major role in the articulation of Branda’s intentions, which can be inscribed within a broader encomiastic discourse relating both to city panegyrics and to ancient and contemporary literature on building sites and architecture. The landscape around Castiglione Olona is a key aspect of this discourse, as demonstrated, on one side, by the stark promontories and thick woods Masolino painted in the baptistery in conjunction with his architectural settings, and on the other, by a textual celebration of Castiglione’s architecture and natu ral setting written in 1432 by Francesco Pizolpasso, Bishop of Pavia.

Masolino’s frescoes at Castiglione Olona are a particularly precocious example of patronage patterns inspired by classical antiquity and informed by a degree of artistic and architectural ingenuity pointing to the patron’s cultural and the artist’s professional ambition. In par tic u lar, an analysis of his architectural settings reveals the painstaking attention with which Masolino engaged with existing architectural practice and the extent to which he proposed bold new solutions, underscoring how his architectural awareness informed this commission. On the one hand, this suggests that architectural knowledge and invention were key skills an artist had to possess in order to fully convey his patron’s vision. On the other, it highlights the cultural potential attached to architectural forms in this period, pointing to a nascent architectural consciousness that was first delineated in artistic practice as a platform for experimentation.

MASOLINO AND ARCHITECTURE

The remarkable architectural character of Masolino’s frescoes for the baptistery at Castiglione Olona stands out in comparison to his previous work, including Branda’s first commission to him, a chapel at San Clemente in Rome, where he painted the lives of St Catherine and St Ambrose between 1428 and 1431.3 The settings Masolino created for this chapel demonstrate his engagement with ornament, especially evident in his capitals, which often elaborate on what we would now identify as the Ionic or Corinthian orders (Figs 1.1 and 1.2), and with structural solutions, as in the two-aisled portico of the Annunciation and the domed building recalling the Pantheon (Figs 1.3 and 1.4). However, his thin walls and excessively slender arches point towards a certain disregard for structural feasibility, evoking Maso di Banco’s arched openings in the Bardi di Vernio Chapel (Fig. 0.1) or Simone Martini’s impossibly narrow columns and piers (Fig.1.5). Masolino’s lithe structures and his empirical application of perspective have often meant that he was brushed aside by a scholarship increasingly concerned with pictorial space. In particu lar, comparisons with his frequent collaborator Masaccio informed an interpretation of Masolino as a somewhat backwards artist, as yet unable to embrace the perspectival developments and more assertive, classicising forms conveyed so credibly by Masaccio.4 This art historiographical narrative has hindered recognition of Masolino’s contribution, especially preventing a closer engagement with his approach to the representation of architecture.

Suggestions that the architectural structures in the Castiglione baptistery were designed by Lorenzo di Pietro, Masolino’s talented workshop aid also known as Vecchietta, are especially revealing of scholarship’s reluctance to recognise Masolino’s artistic and architectural innovation.5 Whilst Vecchietta’s architectural imagination is undeniable, the linearity and clarity of both structure and ornament in the baptistery are at odds with his penchant for structural complexity and abundant decorative detail. This is evident in his frescoes for the Collegiata and especially in his work for the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena (discussed in the next chapter), indicating that Masolino was ultimately responsible for at least the overall design of the architectural settings in the baptistery at Castiglione Olona. Besides, lack of evidence frustrates all attempts at defining precise responsibilities within Masolino’s workshop, and it

Fig. 1.3. Masolino da Panicale, Annunciation, Castiglioni Chapel, San Clemente, Rome, 1428–1431.

Fig. 1.4. Masolino da Panicale, St Catherine Refuses to Pray to the Idol, Castiglioni Chapel, San Clemente, Rome, 1428–1431.

tabernacles with shell niches, pediments and fluted Corinthian pilasters to a pre- existing first storey with pointed arch windows, composite piers and twisted columns.19 A testament to Marvin Trachtenberg’s theory of Building-in-Time, this façade exemplifies the fluidity of the boundaries between seemingly different aesthetic approaches.20 However, while Rossellino had to respond to a pre- existing structure, Vecchietta and Domenico di Bartolo designed ad hoc, complete buildings that are free from the constraints of built architecture: their approach further underlines the persistent appeal of solutions we would now describe as Gothic, as well as the value specifically attached to an innovative, inclusive approach to ornament.

At the same time, Domenio di Bartolo’s Building of the Hospital challenges notions of building typologies by experimenting with the centrally planned, polygonal building. If its Gothic ornament clearly evokes major sacred buildings like the Sienese Duomo or baptistery, it is difficult to imagine how its structure, more similar to the Florentine baptistery, could support the needs of a hospital complex. This is especially evident if one considers the fact that the buildings in this fresco in no way recall the hospital’s actual structure, although this scene supposedly documents its construction or enlargement.21

Showcasing Domenico’s architectural knowledge and imagination, the setting for the Building of the Hospital is a reinvention of the hospital’s locales— a reinvention that, on the one hand, grounds the hospital in the prestigious local tradition of major sacred buildings and raises its

Fig. 2.24. Façade, Palazzo della Fraternità dei Laici, Arezzo, 1375–1550.

profile by introducing innovative all’antica details, and, on the other (by representing a construction site), highlights Domenico’s awareness of building practices and the key figures involved in them, as suggested by the master mason prominently represented in the foreground holding his pair of compasses (Fig. 2.4). This may hint at the hospital’s plans for the renovation of major parts of its complex, including the building of a new sacristy in 1443, as Domenico was working in the Pellegrinaio,22 and the renovation of its church, whose openly stated aims were to render this environment, also functioning as the hospital’s main entrance, “beautiful, honourable and magnificent.”23 Yet, Domenico’s frescoed structures in the Building of the Hospital should not be read as a practical proposal for a rebuilding of the hospital, but as a reinterpretation of its identity in a majestic architectural key and as a transposition of the rector Buzzichelli’s ambition for the institution. This is significant, as it points to the centrality of architecture for the definition of the hospital’s identity through this representative fresco cycle. Whilst a precise interpretation of the relation between the figures eludes us,24 this scene’s emphasis on building processes points to a conscious deployment of architecture as a narrative agent that redefines the image of the hospital. This approach pivots in par ticu lar on ornamental ingenuity and structural experimentation, giving us an insight not only into the patron’s aims but also into the transfer of architectural knowledge between artists, as demonstrated by Domenico’s Papal Indulgence (Fig. 2.6).

The most striking architectural feature of this scene is the hexagonal building in the background (Fig. 2.25), further evidence of Domenico’s fascination for centrally planned polygonal structures. Open on all sides, this detailed, elegant structure, which stands out for its frieze with oculi and shallow dome surrounded by a balcony on large console brackets, evokes an ancient temple, an early Christian martyrium and a celebratory canopy all at the same time. Its closest parallel in Siena is Nicola Pisano’s pulpit in the Duomo (1265–1268), although the arches and elevation are considerably different. Though it defies identification with specific built examples, the structure is an elaboration of Masolino’s temple in the Annunciation to Zechariah at Castiglione Olona (Fig. 1.14). Domenico’s structure rests on round arches rather than an architrave, as Masolino’s, but both buildings have a hexagonal plan, a moulded stringcourse and a frieze with oculi that, in Masolino’s case, are marble inlay roundels, whilst in Domenico’s are proper apertures. Most importantly, both artists proposed a dome surrounded by a balustrade with colonnettes, a solution loosely evoking a tiburio. Siena’s Duomo presents a comparable structure, but its dome is surrounded by a round, covered ambulatory resting on arches, whereas Masolino and Domenico proposed a trabeated balustrade, highlighting the polygonal structure of the building. Domenico must have considered this feature particularly interesting, as he made it jut out from the rest of the structure and emphasised it with prominent console brackets.

These remarkable similarities suggest a transfer of knowledge between the two artists, most likely through Vecchietta, Masolino’s collaborator at Castiglione Olona and Domenico’s fellow painter in the Pellegrinaio, or perhaps through exchanges with the numerous Lombard builders who worked in Siena.25 On the one hand, this transfer confirms that Masolino’s work at Castiglione Olona was considered innovative and worthy of being imitated by his contemporaries, proving the success of his designs. On the other, Domenico’s re- elaboration of Masolino’s proposal indicates that artists exchanged their architectural designs, were aware of

architectural invention and perceived this aspect of their craft as an integral part of their work to which they were willing to dedicate time and thought. Domenico’s centrally planned building in the Papal Indulgence is a particularly apt example, as at first sight it may appear to be superfluous and unrelated to the narrative taking place in the foreground nave. Yet, its carefully thought- out structure and detailed ornament focus the viewer’s attention, demonstrating not only the artist’s perspectival ability but also his architectural ingenuity. Buildings such as these are indices of the importance attached to architectural forms precisely because they are a seeming addition to the basic needs of the narrative message.

This approach was shared by other craftsmen. The marble inlay of the Story of Jephthah (Judges 11, 29–40) for the floor in Siena’s Duomo, made by Bastiano di Francesco in the early 1480s but most likely designed by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, 26 features a centrally planned polygonal structure in the top left corner (Fig. 2.26). Although this is trabeated and has no balcony, it is characterised by a shallow dome with lantern and a prominent cornice, suggesting the artist may have used Domenico’s structure as a model. Though the heart of the action appears to be the battle raging in the foreground, the temple is the setting of Jephthah’s poignant sacrifice of his daughter, and the care with which this polygonal building and others around it have been designed is painstaking, showing the artist’s keen interest in architecture.

Fig. 2.25. Domenico di Bartolo, A Hospital Rector Receives a Papal Indulgence, detail, left wall, Pellegrinaio, Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, 1442–1444.

encapsulates this potential particularly well, further enriching architectural exploration with the possibilities of colour and the convincing suggestion of clearly identifiable materials. More specifically, architecture in frescoes evokes with greater immediacy and effectiveness the transferability between drawing and building. Frescoes are an integral part of the structures on which they are painted, but they also reproduce, albeit in a much more elaborate form, the drawings architects made on the walls of their buildings under construction to explore solutions with their fellow craftsmen working on the site.5 Documents pertaining to Jacopo della Quercia’s Fonte Gaia, already mentioned in the Introduction, indicate this practice was also adopted for sculptural projects to be evaluated by patrons, suggesting a widespread level of literacy in the assessment of perspectival or isometric drawings.6

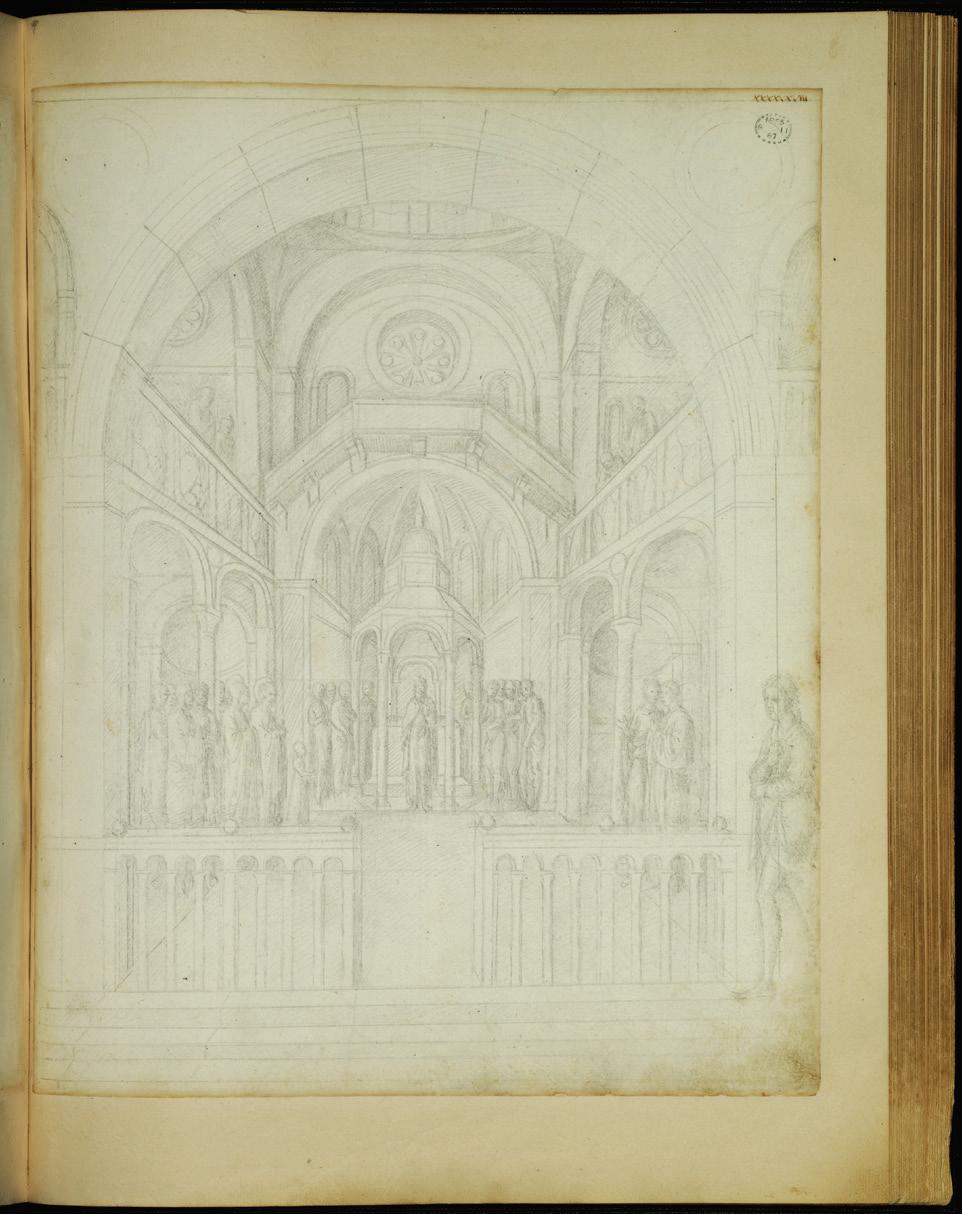

A broad appreciation of three-dimensional architectural drawings is also confirmed by the survival of designs like those in the Libretto degli anacoreti at the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome (1420–1430) and even more so in the Sagredo-Bonfiglioli-Rothschild Album at the Louvre (late fourteenth- early fifteenth century) (Fig. 4.1), in Jacopo Bellini’s albums at the Louvre and British Museum (1440–1470) (Fig.4.2), and in the North Italian Album at the Sir John Soane’s Museum (late fifteenth- early sixteenth century) (Fig. 4.3).7 These precious early designs have so far been studied individually, often eluding the attention of architectural historians because they do not abide by a posteriori standards of project drawings; nor can they be too hastily classed as architectural settings for a narrative, and a straightforward definition as studies for theatre stages is at best an educated guess. Yet, considered together, they further corroborate craftsmen’s fascination and genuine engagement with architectural forms beyond pictorial space and narrative restrictions. Carefully executed to a polished state on expensive parchment (or heavy white paper in Jacopo Bellini’s album at the British Museum), these drawings were most likely used to draw patrons’ attention, indicating the broad appeal of architectural forms. They urge us to reconsider our categorisation of architectural drawings to include a wider variety of representational strategies whose intersection with building practice is in need of clarification.8

Focusing on disegno also enables us to glean the parallels between architecture in painting and the development of architectural practice through drawing. Baldassarre Peruzzi’s drawing for St Peter’s at the Uffizi (Fig. 4.4), realised around 1506, ingeniously accommodates the building’s ground plan, section and elevation in one single image by applying an aerial perspective. This enabled Peruzzi to maintain the architectural legibility of the project whilst at the same time giving a sense of what the building would look like as a whole. As Brothers has noted, this approach also creates a temporal dimension, in which the building appears as a design, during construction and as completed.9 Representational possibilities of this sort had already been explored by painters. The so- called Ruskin Madonna at the National Gallery in Edinburgh (c. 1470–1475) (Fig. 4.5) features a basilica-like structure, but the clean cut of the pier bases visible behind the Virgin looks like a horizontal section drawing, suggesting at least part of the basilica was abandoned mid- construction, whilst the wall and arch in the background appear to be a ruin. Thus, as in Peruzzi’s drawing, this setting eloquently conveys different temporalities.10 The high perspective, which enables us to see the complex geometric paving, is also comparable to Peruzzi’s, as the ruined structure in the background is comparable to the elevation of the

Fig. 4.1. North Italian draughtsman, Palace with staircase and rabbit, 845 DR, fol. 9r, Sagredo-Bonfiglioli-Rothschild A lbum, Musée du Louvre, Paris, late fourteenth- early fifteenth century.

Fig. 4.2. Jacopo Bellini, Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple, Jacopo Bellini A lbum, 1855,0811.67, British Museum, London, 1440–1470.

chancel in his drawing. T hese observations are not meant to establish a direct link between the Ruskin Madonna and Peruzzi’s drawing, but to highlight painters’ close engagement with strategies for the representat ion of architecture, and the extent to which t hese later informed experimentations with project drawings.

Yet, this emphasis on drawing risks overshadowing existing tensions between the arts. The frescoes discussed in this book are especially successful at underscoring the potential of architecture in painting in terms of structure, ornament and materials, posing a challenge to existing built architectural examples. They thus articulate a competitive comparison between painting and architecture, which is a further index of the social and professional development of a craftsman’s status. This form of paragone is a painter’s assertive statement of the versatility of his ingenuity and of the extent of his architectural knowledge, and therefore a claim to architectural practice and to t hose aspects of it that entail sculptural abilities, such as capital and frieze designs, crenellation and tracery: it is a painter’s answer to the overwhelmingly sculptural character of medieval microarchitecture. Rather than being a harmonic expression of the unity of the arts, this book’s case studies explore the facilit y of painting for bold architectural innovation,

Fig. 4.3. North Italian draughtsman, Cityscape, North Italian A lbum, SJSM Vol. 122, p. 13, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, late fifteenth- early sixteenth century.

22. I n addition to the corner capitals of the Temple of Portunus in the Forum Boarium, Masolino’s frescoed Ionic order is comparable to only two ancient examples in Rome, which he may have seen during his stay t here: the Ionic order of the temple of Saturn (320 CE) and two spolia capitals in the interior of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere (1140), which may have been taken from the Baths of Caracalla.

23. Vincenzo Scamozzi, Dell’idea dell’architettura universale, Part II, Book VI, 17. Palladio included the angular Ionic order of the Temple of Saturn (then known as the Temple of Concord) in his Quattro Libri (1570), but unlike his pupil Scamozzi he did not especially encourage its use. Andrea Palladio, The Four Books on Architecture, ed. by Robert Tavernor and Richard Schofield (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1997), IV, Ch. 30, 336–339; Calder Loth, “The Scamozzi Ionic Capital. Classical Comments,” Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, online publication (n.d.).

24. David Hemsoll convincingly argued for a date later than the canonically accepted 1502 for the Tempietto. Hemsoll, Emulating Antiquity, 149–157. Although the window may not be a conscious reference to antiquity in either Masolino’s or Bramante’s case, the similarities between t hese painted and built examples remain striking.

25. For an identification of the topography of Rome in this fresco: Spiriti, “Imago Urbis,” 64–70. On the no longer extant Baptist cycle at the Lateran: Luke Syson and Dillian Gordon, Pisanello. Painter to the Re naissance Court (London: National Gallery and Yale University Press, 2002), 16–19; and Borromini’s drawing, inv. HdZ 4467, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin. On Branda’s projects for Sant’Apollinare: Roberto Valentini, “Gli istituti romani di alta cultura e la presunta crisi dello Studium,” Archivio della reale Deputazione romana di storia patria, 59 (1936): 235–237 (doc. VI).

26. Johannes of Olmütz, Life of Branda Castiglioni, in Bondioli, “La ricognizione della salma,” 477. Branda also wanted to found a student residence in Rome, on which see: Valentini, “Gli istituti romani”; Cazzani, Il cardinale Branda Castiglioni, 135; Anna Luisa Visintin, “Il più significativo precedente del Collegio Ghislieri: il Collegio Universitario Castiglioni (1429–1803),” in Il collegio universitario Ghislieri di Pavia, ed. by M. Bendiscioli, A.L. Visintin, M. Marcocchi and E. Sanesi Tambassi (Milan: Giuffrè editore, 1966), 49–89; Franco Zambelloni, “Il Collegio Castiglioni prima istituzione collegiale pavese,” in Collegio Ghislieri 1567–1967, ed. by Associazione Alunni del Collegio Ghislieri (Milan: Alfieri and Lacroix, 1967), 209–219. On Castiglione Olona’s Scolastica: Spiriti, Castiglione Olona, 109–114.

27. Vespasiano da Bisticci, Lives of Illustrious Men of the XVth Century, ed. by William George, Emily Waters and Myron P. Gilmore (Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 119–121.

28. Commentariorum Cyriaci anconitani nova fragmenta, ed. by Annibale degli Abati Olivieri (Pesaro: In aedibus Gavenelliis, 1763), 38; Alessandro Rovetta, “Filarete e l’umanesimo greco a Milano: viaggi, amicizie e maestri,” Arte lombarda, 66 (1983): 96–103.

29. Charles Mitchell, Edward W. Bodnar and Clive Foss, Cyriac of Ancona: Life and Early Travels (Cambridge, MA and London: I Tatti Renaissance Library, Harvard University Press, 2015), 103–129, 264; Cazzani, Il cardinale Branda Castiglioni, 187.

30. Giorgio Mangani considers Cyriac of Ancona as the foremost promoter of the revival of antiquity, specifically endeavouring to turn it into a commodity. Giorgio Mangani, Antichità inventate. L’archeologia geopolitica di Ciriaco d’Ancona (Milan and Udine: Mimesis, 2016).

31. Work must have started in or before 1437, as a papal bull of this year makes a reference to the Chiesa di Villa as being u nder construction. The church must have been completed by 1444, when Branda’s nephew Baldassarre left funds for its decoration and the clearing of the churchyard. Maria Bonaiti, “La

“This book explores the communicative power and astonishing variety of architectural representation in fifteenth-century Italian painting. Lupi illuminates three wonderful fresco cycles in different parts of Italy, each serving a different type of patron, and all designed to enhance reputations, strengthen authority, and shape specific identities. The meticulous research and fresh insights of this new study help us all to look closely at these vast yet strangely neglected parts of paintings, and to understand how widespread, engrained and inspiring depicted architecture can be.”

Amanda Lillie, Professor Emerita, University of York and Curator of Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting

“Livia Lupi has written the book about painted architecture that the field of Italian Renaissance art and architecture has long needed. Moving beyond the fixation on perspective representation, she addresses the many and varied ways painters employed architecture for narrative ends. Despite the prominence of architecture in many fifteenth-century paintings, few scholars have taken it as their central subject and when they have it has often been in relation to the issue of pictorial space. Lupi widens the lens, and through an in-depth analysis of several key case studies, opens up a broad set of interpretations. Featuring beautiful color illustrations and clear prose, her book is sure to inspire many other studies.”

Cammy Brothers, Professor, Northeastern University and author of Michelangelo, Drawing and the Invention of Architecture and Giuliano da Sangallo and the Ruins of Rome