diane h. bodart and cleo nisse, editors

diane h. bodart and cleo nisse, editors

diane h. bodart and cleo nisse, editors

diane h. bodart and cleo nisse, editors

Diane H. Bo Dart an D Cleo n isse David Rosand on Titian: The Art Historian’s Mark 6

Chapter 1 Titian and the Critical Tradition (1982) 32

TITIAN IN SITU 50

Chapter 2 Titian in the Frari (1971) 52

Chapter 3 The Assunta (1988) 72

Chapter 4 Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple and the Scuola della Carità (1997) 96

UT PICTOR POETA 142

Chapter 5 Ut pictor poeta: Meaning in Titian’s Poesie (1972) 144

Chapter 6 Inventing Mythologies: The Painter’s Poetry (2004) 160

Chapter 7 Pastoral Topoi: On the Construction of Meaning in Landscape (1992) 180

Chapter 8 Pietro pictore Aretino (2010) 194

VENUS IN QUESTION 216

Chapter 9 Ermeneutica amorosa: Observations on the Interpretation of Titian’s Venuses (1980) 218

Chapter 10 So-And-So Reclining on Her Couch (1993) 228

Chapter 11 The Passion of Adonis (2014) 246

TITIAN’ S HAND 258

Chapter 12 Titian and the Woodcut (1976) 260

Chapter 13 The Stroke of the Brush (1988) 290

Chapter 14 “La Mano di Tiziano” (1999) 314

Chapter 15 Titian’s Saint Sebastians (1994) 326

OLD AGE 334

Chapter 16 “Most musical of mourners, weep again!”: Titian’s Triumph of Marsyas (2010) 336

Chapter 17 The Challenge of Titian’s “Senile Sublime” (1990) 348

PLATES 354

Religious Paintings 356

Portraits 391

Mythologies 399

David Rosand: Bibliography on Titian 436

Selected Bibliography on Titian Published Since 2014 439 Index 441

Il Caualier Titiano, ne le cui mani uiue la idea d’una nuoua natura non senza gloria de l’Architettura, la quale è ornamento de la grandezza del suo perfetto Giudicio.

Sebastiano Serlio1

Three great altarpieces span what is generally acknowledged to be the most energetic period of Titian’s development, the years between 1516 and 1530: the Assunta (1516–18), the Madonna di Ca’ Pesaro (1519–26), both in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, and the Martyrdom of Saint Peter Martyr (1528–30), painted for the church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo.2 The last of these was destroyed by fire in 1867, but the first two are still in situ The Assunta was removed from the high altar of the Frari to the galleries of the Accademia in 1817 and was returned to its original location only after the First World War; except for restorations, the Pesaro Madonna has never left its position on the altar of the Pesaro family.3 During the decade of 1516–26, then, the Frari was the most significant scene of activity for Titian as a painter of religious images; its continued importance to the master is further attested by the arrangements he made to be buried there beneath the altar of the Crucifixion, for which he was to have provided as an altarpiece his late canvas of the Pietà.

In the long course of his career, Titian surely came to be quite familiar with that Gothic basilica, to know its vast spaces, traffic patterns, and visual axes. The purpose of the following observations is to offer analyses of Titian’s Frari altarpieces in the context of their architectural setting. It is hoped that such consideration in three dimensions, so to speak, will afford new modes of approach to some of the critical problems surrounding these pictures—above all, the Pesaro Madonna thereby adding a further dimension to our idea of Titian’s creative imagination.

The inscription on the high altar of the Frari informs us that it was erected in 1516 at the charge of Fra Germano da Casale, prior of the Franciscan monastery.4 An unusual entry in the diaries of Marino Sanuto, rare for its explicit reference to a work of art, records the unveiling of Titian’s picture two years later, on 19 May 1518.5

1 Regole generali di architettura sopra le cinque maniere de gli edifici (Venice, 1537), iii.

2 The now canonical sexpartite division of Titian’s development was given its definitive formulation by Theodor Hetzer: Tizian, Geschichte seiner Farbe (Frankfurt am Main, 1935), 79 ff., and in Thieme-Becker, Allgemeines Lexikon, xxxiv (Leipzig, 1940), 158 ff. Cf. also Erwin Panofsky, Problems in Titian, Mostly Iconographic (New York, 1969), 18 ff.

3 For the nineteenth-century restorations, see Francesco Zanotto, Pinacoteca veneta ossia raccolta dei migliori dipinti delle chiese di Venezia (Venice, 1860), 11, No. 81, and J. A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle, The Life and Times of Titian, 2nd ed. (London, 1881), i, 309, note. The canvas was removed to the Accademia for restoration in 1843 and to the Ducal Palace in 1882–84, when work

was done on the altar itself and the window behind it, the bottom half of which was then closed (Archivio del Convento S.M. Gloriosa dei Frari, Fabbriceria della chiesa parrocchiale . . . , No. 8, Oggetti di belle arti, No. 20, and Pala Ca’Pesaro, 1882–4) I would like to thank Dr. Julia Keydel for calling my attention to these records and Padre Livio Chudoba, archivist of the Frari, for his generous hospitality.

4 The inscriptions on the tall pedestals of the flanking columns read: assvmptae in Coelvm virgini aeterni opifi C is matri and frater germanvs H an C aram erigi C vravit m Dxvi. The prior is often referred to by modern scholars as Marco Germano, but as Giuseppe Ungaro has noted (La basilica dei Frari, Venezia, [Padua, 1968], 60) the M. or M o before his name

figure 14

Apse, Santa Maria dei Frari, Venice. Media Center for Art History, Columbia University

simply stands for Maestro. In the document cited below, note 20, he is recorded as “Magister Germanus de Casale.” 5 Marino Sanuto, I Diarii (1496–1533) (Venice, 1879–1903), xxv, col. 418: “[Dil mexe di Mazo 1518] A di 20. Fo san Bernardin, el qual zorno per parte presa in Pregadi si varda, nè li oficii senta. Et eri fu messo la palla granda di l’altar di Santa Maria di Frati Menori suso, depenta per Ticiano, et prima li fu fato atorno una opera grande di marmo a spese di maistro Zerman, ch’è guardian adesso.” Sanuto’s mazo has often been misread as marzo rather than dialect for maggio; cf. inter alia, Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Life and Times, 1, 212, and Gino Fogolari, I Frari e i SS. Giovanni e Paolo (Milan, 1931), Pl. 8.

6 Lodovico Dolce, responding to the anti-Venetian bias of the first edition of Vasari’s Vite, declared with regard to the Assunta, “E certo si può attribuire a miracolo che Tiziano, senza aver veduto alora le anticaglie di Roma, che furono lume a tutti i pittori eccellenti, solamente con quella poca favilluccia ch’egli aveva scoperta nelle cose di Giorgione, vide e conobbe la idea del dipingere perfettamente” (Dialogo della pittura, intitolato l’Aretino [1557], ed. Paolo Barocchi, in Trattati d’arte del Cinquecento [Bari, 1960], 202). For comparison of the Assunta with Raphael’s work, see especially the brief but pertinent comments in Cecil Gould,

On that day Titian established a classical High Renaissance art in Venice, for in its dramatic gestures, its breadth of form, and its symbolically geometric structure, the Assunta (Plate 5) epitomizes a style more commonly defined with reference to the art of Raphael. Critics since the sixteenth century have indeed marveled that Titian could have created a work of such monumentality before he made the pilgrimage to Rome.6 Venetian painting to that date offers nothing in the way of precedent and very little, even in the juvenilia of Titian himself, that can be said to anticipate the grandeur of the Assunta. In interpreting the subject dramatically, Titian created a heroic figure type new to Venice. Abandoning the naturalism of his predecessors, he depicted the celestial realm as a truly supernatural phenomenon: the golden circle of Heaven in the Assunta, like that of Raphael’s Disputa, glows with a radiance beyond nature. In the art of Giovanni Bellini celestial light found expression through empirically comprehensible phenomena, manifesting itself as a purer distillation of natural light or as the reflection of golden mosaics. Titian, however, depicted a divine radiance existing entirely on its own terms, a visual reality essentially different from that of this world. In this he realized, again like Raphael, new possibilities of expression and ideality.

The accounts in the art literature of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries concerning the reception of the Assunta confirm its extraordinary impact; and, granting the suspicious status of biographical anecdote as art-historical source material, the reports of Dolce and Ridolfi nevertheless ring true. “E certo in questa tavola si contiene la grandezza e terribilità di Michelagnolo, la piacevolezza e venustà di Rafaello, et il colorito proprio della natura,” writes Lodovico Dolce in enthusiastic admiration.7 Then, in a passage echoing Vasari in its historicism, he describes the shocked incredulity of the initial audience: “Con tutto ciò i pittori goffi e lo sciocco volgo, che insino alora non avevano veduto altro che le cose morte e fredde di Giovanni Bellino, di Gentile e del Vivarino […], le quali erano senza movimento e senza rilevo, dicevano della detta tavola un gran male. Dipoi, raffreddandosi la invidia et aprendo loro a poco a poco la verità gli occhi, cominciarono le genti a stupir della nuova maniera trovata in Vinegia da Tiziano […].”8

Writing nearly a century after Dolce and without any overt reference to his account, Carlo Ridolfi offers a further commentary on the reception of the picture as well as some interesting details concerning its execution: “Dicesi, che Titiano lauorasse quella tauola nel Conuento de’ Frati medesimi, si che veniua molestato dalle frequenti visite loro, e da Fra Germano curatore dell’opera era spesso ripreso, che tenesse quegli Apostoli di troppo smisurata grandezza, durando egli non poca fatica à correggere il poco loro intendimento, e dargli ad intendere, che le figure doueuano esser proportionate al luogo vastissimo, oue haueuansi à vedere, e che di vantaggio si sariano diminuite […].”9 Now, while it is of course impossible to verify the facts of Ridolfi’s narrative,10 Fra Germano’s protest would seem to corroborate the general tenor of Dolce’s account and is certainly understandable in

“Correggio and Rome,” Apollo, l xxxiii (1966): 336; cf. also Rodolfo Pallucchini, Tiziano (Florence, 1969), i, 46, and Harold E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian, i, The Religious Paintings (London, 1969), cat. no. 14, both with further references.

7 Dolce, Dialogo, 202.

8 Ibid. The ellipsis within the quoted passage reads, in parentheses, “perché Giorgione nel lavorare a olio non aveva ancora avuto lavoro publico e per lo più non faceva altre opere che mezze figure e ritratti.”

9 Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte (1648), ed. Detlev von Hadeln (Berlin, 1914–24), 1, 163. The monks

were evidently slow to comprehend Titian’s meaning. According to Ridolfi, not until the imperial ambassador offered to buy it for the emperor did they begin to realize the value of their new altarpiece. Another version of the story has it that Titian threatened to keep the painting for himself until he received a personal apology from Fra Germano (see Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Life and Times, i, 212).

10 Antonio Sartori, himself a Franciscan, rejects it as a malicious fabrication, a slur on the order which had earlier patronized the young Titian in Padua (S.M. Gloriosa dei Frari, 2nd ed. [Padua, 1956], 45 f.).

view of the picture’s innovative qualities. More significantly, Titian’s supposed response, acknowledging the extraordinary scale of the figures, relates directly to the very nature of the commission and the peculiarities of its architectural setting.

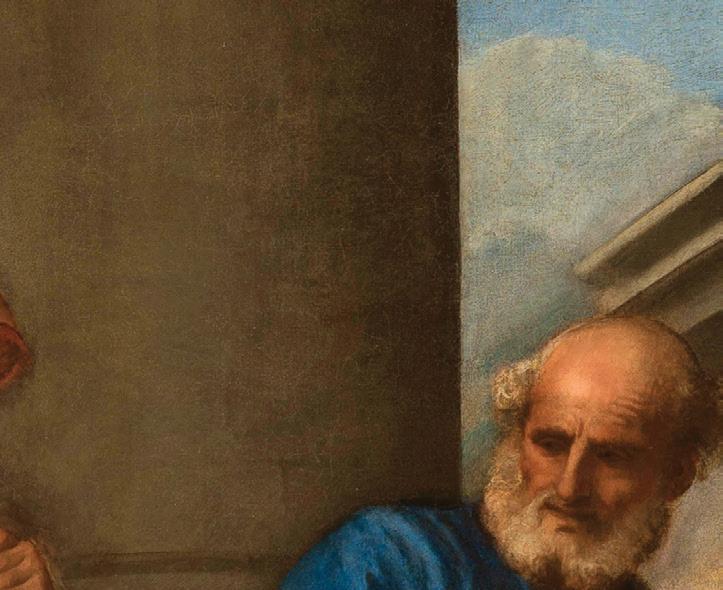

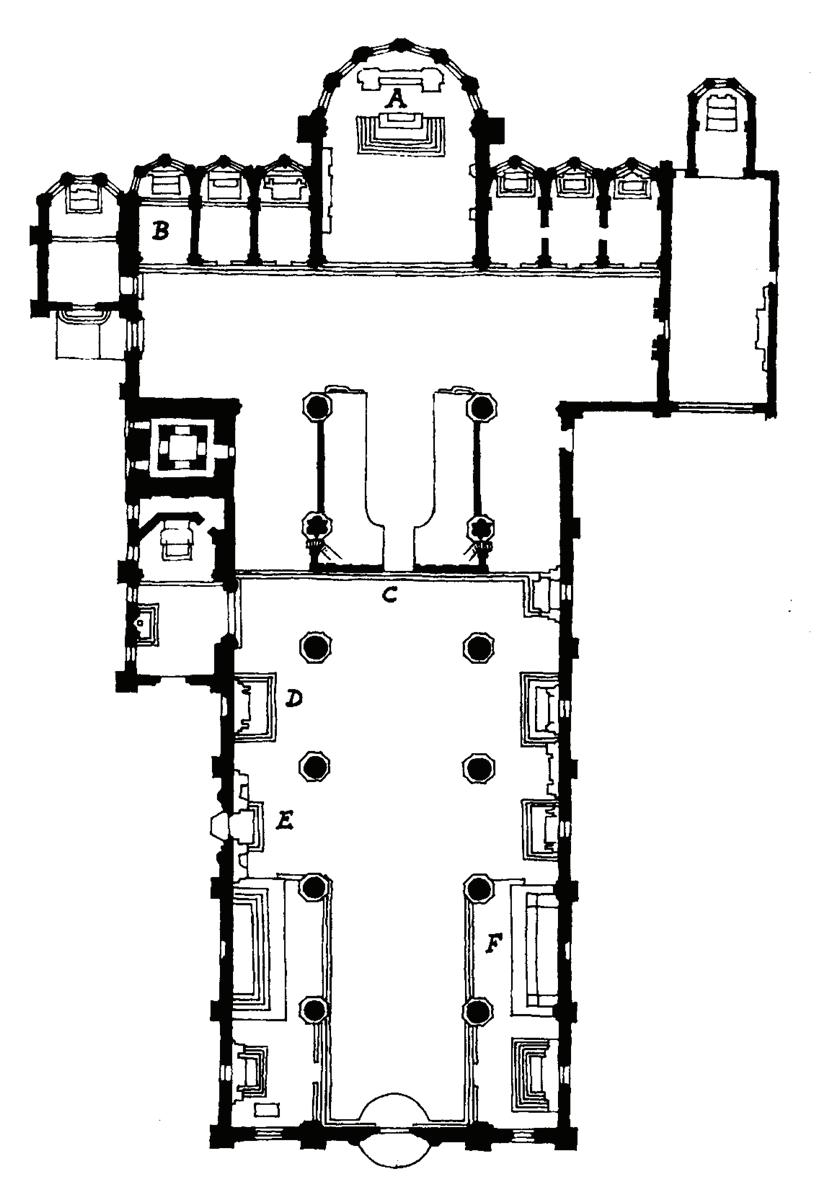

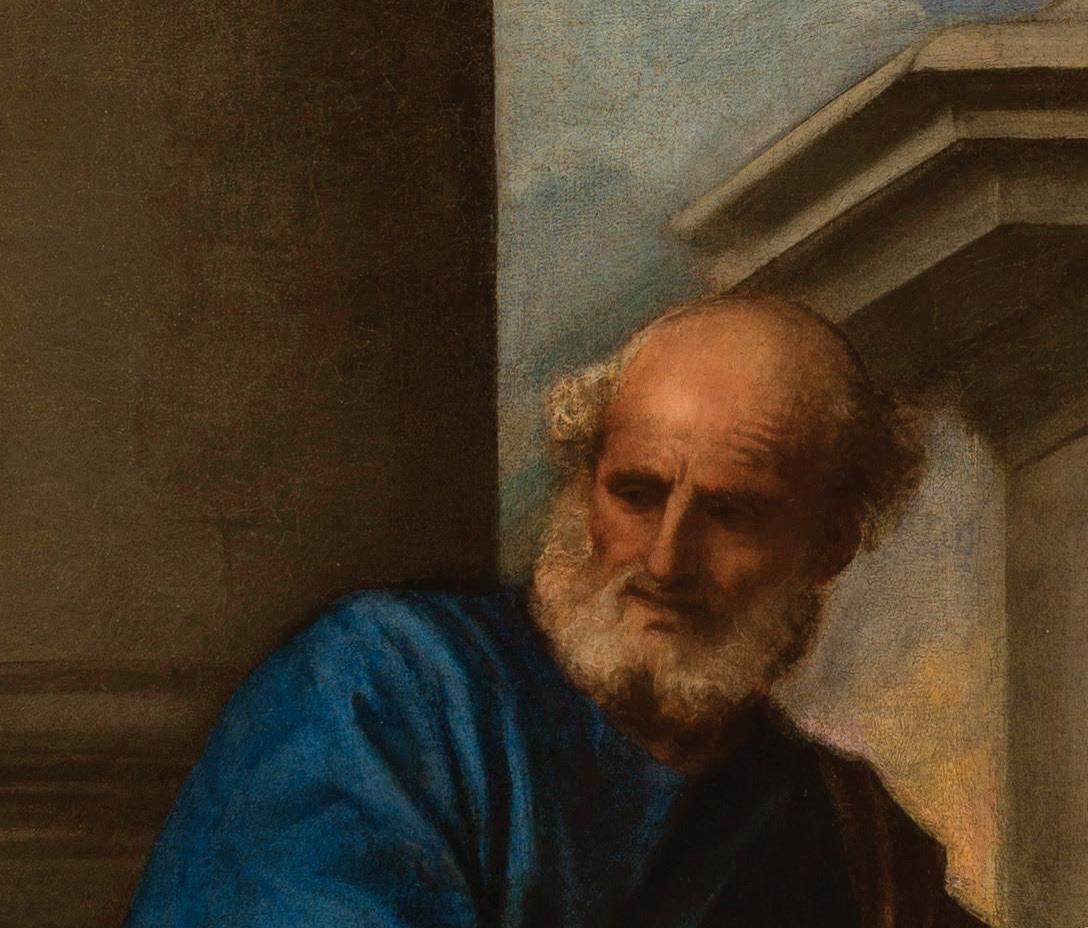

The church of Santa Maria dei Frari, completed in the early quattrocento, is a broad Gothic basilica on a Latin cross plan oriented to the southwest (Fig. 13).11 In the apse the sixteenth-century high altar rises to the height of the arcade (Fig. 14), and this juxtaposition of High Renaissance altar and Gothic setting must have posed a particular challenge.12 The stylistic conflict is partly reconciled by certain architectural adjustments; the altar, for example, fills the width of two bays and its cornice is aligned with the string course above the arcade. Within Titian’s painting the golden circle of heavenly radiance containing the Virgin, God the Father, and the celestial choir, corresponds to the upper zone of the arcade windows; the rectangular block of apostles below reaches to the height of the bottom zone of windows.

But a more difficult visual problem was posed by the glowing, dappled backdrop of windows and tracery against which the Assunta has to be seen.13 The breadth and simplicity of Titian’s design and colors are calculated to establish a dominant contrast to the more delicate detail of the surrounding apse. Seen now with the aid of artificial light, the painting does indeed emerge triumphant from its busy environment, but it was evidently not always so effective. Vasari, for example, reports that the Assunta was hard to see; he blames this, however, on the fact that it was painted on canvas (it is actually on panel) and on its supposedly poor state of preservation.14 While his reporting may be inaccurate in some rather fundamental details, Vasari’s perception of the picture was apparently shared by later observers, for in 1650 permission was granted to open two large lunette windows above the ducal tombs on the presbytery walls to obtain better illumination for the painting.15

The bold geometry of Titian’s composition was conceived with respect to other conditions of the site as well. In Ridolfi’s biography the artist defends the enormous size of the figures by citing the space in which they must operate and the distance from which they are to be seen, and here too the details of the literary account seem to be verified by the work itself and its site. First of all, the dimensions of the panel, which is over twenty-two feet high (6.90 × 3.60 m), do indeed require figures of a proportionately monumental scale. Secondly, the size of the altar is commensurate with the spaciousness of the Frari itself. Approaching the high altar along the nave of the church, one’s vision is focused upon it from a distance through the open arch of a choir screen (Fig. 15 and C in Fig. 13). Constructed in 1475, this screen was one of the given factors of the site, and its arched aperture provided a scenographic frame for the Assunta. 16 Although the choir screen was a pre-existent architectural unit, it was not just passively accepted by the designer of the altar. He actually utilized it, repeating, with some modification, the ornament of the screen in his own design; specifically, the gilded arabesque motif of the quattrocento arch is taken up in the arched frame of the altarpiece, thereby establishing a direct visual relationship between the two monuments.

11 On the history of the Frari: Flaminio Corner, Notizie storiche delle chiese e monasteri di Venezia e di Torcello (Padua, 1758), 361 ff.; Giambattista Soravia, Le chiese di Venezia descritte ed illustrate (Venice, 1823), 3 ff.; P. Paoletti, L’Architettura e la scultura del Rinascimento in Venezia (Venice, 1893), pt. i, 45 ff.; Aldo Scolari, “La chiesa di Sta. Maria Gloriosa dei Frari ed il suo recente restauro,” in Venezia, studi di arte e storia a cura della Direzione del Museo Civico Correr (Venice, 1920), 148 ff.; and Sartori, Frari, 3 ff.

12 A similar situation obtains in the Cappella dei Milanesi (B in Fig. 13), where the Renaissance reredos of 1503 is set into a Gothic apse. The solution there, as Fogolari recognized (I Frari, Pl. 11), anticipates in many ways the high altar of 1516 (cf. below, note 17).

13 The only designs presently in these windows, dedicated to the lives of Saint Francis and Saint Anthony of Padua, date from 1907 (Sartori, Frari, 46).

14 Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, ed. G. Milanese (Florence, 1878–85), vii, 436:

“[…] ma quest’opera, per essere stata fatta in tela, e forse mal custodita, si vede poco.” Vasari’s identification of the support as canvas has been carelessly repeated by some modern scholars (e.g., Hans Tietze, Titian [London, 1950], 396). Mark Roskill has mistranslated Dolce’s accurate description of the Assunta, “una gran tavola,” as “a large canvas” (Dolce’s “Aretino” and Venetian Art Theory of the Cinquecento [New York, 1968], 187).

15 Scolari, “La chiesa,” 166. The lunettes were closed in the course of the twentieth-century restorations. On the darkening of the Assunta, cf. also the

The sculptural decoration of the reredos, understandably neglected in discussions of the Frari altarpiece, deserves some comment, for its iconography is in fact related to that of Titian’s painting (Fig. 14). Crowning the triumphal arch of the architectural frame stands the figure of the resurrected Christ, flanked by the primary saints of the church, Francis and Anthony of Padua. In the center of the bottom cornice of the frame itself is a small relief of the dead Christ attended by two angels. Thus, the theme of Mary’s ascent from her tomb to Heaven is complemented by that of Christ’s own Resurrection. The triumph over death, explicitly articulated by details like the Victory figures in the spandrels and implicit in the sacrificial bucrania in the entablature, is the guiding idea behind the altar; like many of the preceding monuments in the Frari, the high altar is based precisely on the concept of the triumphal arch.17

The design of the Frari altar has been plausibly ascribed to Lorenzo Bregno,18 but one particular factor could not possibly have been the decision of an early cinquecento stone carver in Venice: the conception of an altar painting on such

observations of Sir Joshua Reynolds (cited in Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Life and Times, 1, 211) and Anton Maria Zanetti, Della pittura veneziana (Venice, 1771), 110: “Ad onta del lume contrario e del fosco velo, con cui il tempo ingombrò questa pittura, si giunge a vedere ch’essa è dipinta d’un carattere assai grande.”

16 The screen, possibly initiated by the Bon workshop, was completed by Pietro Lombardo and his shop and is inscribed 1475. See Giulio Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario, 3rd ed. (Rome, 1963), 589, and Fogolari, I Frari, Pl. 5.

17 Cf. e.g., the bucrania and the Victory figures in the spandrels of the 1503 altar in the Cappella dei Milanesi (ill. in Sartori, Frari, 37) and the sepulchral monument of Benedetto Pesaro, with its nude figures of Neptune and Mars flanking the triumphant effigy of the deceased (ill. in Fogolari, I Frari, Pl. 23).

18 Paoletti in Thieme-Becker, Allgemeines Lexikon, iv, 570. The monument of Benedetto Pesaro, cited in the preceding note, has also been attributed to Lorenzo Bregno (Soravia, Le chiese, ii, 46 ff.).

19 Titian’s reputation as knowledgeable in architectural matters is enthusiastically attested by Serlio in the tribute quoted in the epigraph to this article. The two had served together in the 1534 expertise on Francesco Giorgi’s complex program for San Francesco della Vigna (see R. Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism [London, 1952], 93 f.).

20 Archivio di Stato di Venezia, S. Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, No. 5, Cathastico incomencia 1502, c. 5.

a monumental scale. That daringly imaginative choice must have been made by the painter himself, who, after all, bore the final public responsibility for its effective realization. Indeed, it seems evident that the very conception of the altar itself was an act of the highest pictorial and, we might say, theatrical imagination, and the Assunta is so beautifully attuned to the various architectural considerations of the site that one is tempted to attribute the basic idea for the entire monument to a single mind. Lorenzo Bregno may have carved and gilded the stone, but he may very well have been following the directions of Titian.19

Titian’s awareness of architectural settings and of the particular problems of vision is still further revealed in his second Frari altarpiece, the Madonna di Ca’ Pesaro (Plate 6), which graces the altar of the Immaculate Conception (D in Fig. 13). On 3 January 1518, the altar was conceded to Jacopo Pesaro as the Pesaro family chapel in perpetuity; at the same time he was granted permission to erect his own funerary monument on the wall just to the right of the altar.20 On 28 April of the following year Titian acknowledged the first payment for the altarpiece.21 Payments continued until 27 May 1526, and the painting was in place by December 8, in time for the celebration of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception.22

Two striking features of Titian’s Pesaro Madonna are generally cited in discussions of the picture’s place in his oeuvre and its significance in the development of Renaissance painting: the asymmetrical position of the Virgin and Child and the two columns set so dramatically against the sky. The latter motif in particular has inspired some of the loftiest passages in the modern critical literature. But, as is well known, those massive columns soaring above the figures and intersected by the cloud with two cross-bearing angels in a decidedly Baroque manner were evidently not part of Titian’s original composition. In 1877 August Wolf first observed that behind the columns one could discern the traces of a barrel vault springing from the wall to the right;23 indeed, between the wings of the two angels a segment of an arch of the vault is still visible through the overpaint (barely visible in reproduction). Those critics who have considered Wolf’s observations have tended to assume that Titian himself effected this significant alteration during the course of executing the picture, that is, between 1519 and 1526. However, in a highly suggestive study, Staale Sinding-Larsen has argued persuasively that the columns are not Titian’s, that they were added long after the completion of the altarpiece, even long after the artist’s death.24

Despite the admittedly dramatic impact of the columns—deriving, I think, more from the spatial effect of the cloud hovering before them than from the columns per se—they simply do not make architectural sense, as Sinding-Larsen was the first to insist. Most obviously, in the context of this composition, the columns

21 Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Life and Times, 1, 441. The document is now in the Museo Correr (see A. Scrinzi, “Ricevute di Tiziano per il pagamento della Pala Pesaro ai Frari,” in Venezia, studi di arte e storia . . . , 258 f.).

22 Sanuto, Diarii, xliii, col. 396: “[mDxxvi dicembre] A di 8. Fo la Conception di la Madona, et si varda, et fassi la festa a la Misericordia, etiam in molte altre chiese et ai Frari menori a l’altar hanno fatto i Pexari in chiesa.” Sanuto’s text merely states that the feast was celebrated at the Pesaro altar; it does not, as is usually implied, declare that the altar was inaugurated on that date or that Titian’s painting

was then “solemnly unveiled.” Contrary to Wethey’s implications (The Religious Paintings, cat. no. 55), the altar was always dedicated to the Immaculate Conception and is so identified in the concession to Jacopo Pesaro (see above, note 20).

23 August Wolf, “Die Madonna der Familie Pesaro in der Kirche der Frari zu Venedig,” Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, xii (1877): 9 ff.

24 Staale Sinding-Larsen, “Titian’s Madonna di Ca’ Pesaro and its Historical Significance,” Institutum Romanum Norvegiae, Acta ad archaeologiam et artium historiam pertinentia, 1 (1962): i, 39 ff.

bear no relation to the other architectural elements. The wall to the right and the base of the Virgin’s throne are of Lombardesque design; their marble revetment matches and continues the encrusted manner of the altar frame and of the neighboring tomb of Jacopo Pesaro (Fig. 16).25 With the columns substituted for the previous barrel vault, the background wall is rendered structurally superfluous, a vestigial element whose heavy cornice now supports only a segment of blue sky. Against the coloristic activity of the polychrome architecture the columns appear quite incongruous in their monolithic gravity and colossal size. Furthermore, they themselves have no evident function. Disappearing beyond the upper limits of the composition, they support nothing, nor do they give any indication of a natural termination. For columns that are frequently supposed to signal a new era in Venetian Renaissance art they are strangely without entasis and disturbingly incommensurable.26 Unlike their presumed counterparts in later Renaissance designs—Veronese’s Giustiniani Madonna of 1551 in San Francesco della Vigna is the most often cited— they are not architectural fragments, symbols of the world ante gratiam.

While some scholars have invested these columns with an iconographic significance,27 no interpretation, whatever its possible merits, can ignore the basic visual facts that the columns are demonstrably out of proportion to one another and that their perspective construction makes little sense, confusing rather than clarifying the spatial setting. The horizon line of the composition is low, being marked by the step upon which Saint Peter stands, yet the base moldings of the columns, set appreciably higher in the pictorial field, are seen in almost pure profile. Now, while Titian was hardly an academic purist in matters of perspective; such gross inconsistencies and contradictions are not to be found in his work and it seems more appropriate to ascribe their presence in the Pesaro Madonna to another hand.28

Sinding-Larsen suggested that the “modernization” of Titian’s picture may date from the seventeenth century, when, in 1669, the massive sepulchral monument of Giovanni Pesaro, the first doge of the family, was erected to the left of the altar (E in Fig. 13).29 The addition of the colossal columns to the Pesaro Madonna, masking the original, quite old-fashioned Lombardesque architecture,30 would have related the painting over the family altar to the most recent and grandiose Pesaro monument in the Frari, while diminishing the initially intended relationship to the earlier tomb of Jacopo Pesaro.

There is no documentary evidence to confirm or to refute this hypothesis; the literary sources are concerned mainly with the naturalism of the figures and make no mention of the architecture. Some supporting evidence, however, comes

25 Sartori (Frari, 28) asserts that the tomb was completed “dai Lombardi” in 1524. The inscription on the monument was recorded by Sansovino in 1581 (Francesco Sansovino, Venetia, città nobilissima et singolare, ed. Giustiniano Martinoni [Venice, 1663], 189); see also Soravia, Le chiese, ii, 131 f. Jacopo Pesaro, Bishop of Paphos, appointed commander of the papal fleet by Pope Alexander iv, was victorious over the Turks at the Battle of Santa Maura in 1502. These events dominate the personal iconography of the Pesaro, Madonna—in the special patronage of Saint Peter and in the group of Christian warrior leading the defeated figures of a Turk and Moor—as well as that of the earlier small votive picture in Antwerp, in which the pope presents the kneeling Pesaro to Saint Peter (Plate 8). For the problems surrounding the dating and attribution of the Antwerp canvas, cf. the recent observations of Sinding-Larsen, “Titian’s Madonna,” 159 ff., and Panofsky, Problems, 178 f.; for a summary of previous opinions on the dating, see Wethey, The Religious Paintings, cat. no. 132.

26 Crowe and Cavalcaselle may have had some reservations regarding the aesthetic propriety of the columns, but, assuming them to be the creation of the master, they evidently resolved their doubts by a critical leap of faith. The passage is, I think, worthy of full quotation: “Far away from those humble conceptions of place which mark the saintly pictures of earlier times, the Pesari kneel in the portico of a temple, the pillars of which soar to the sky in proportions hitherto unseen. The Virgin’s throne is raised to a platform, to which access is obtained by two high steps, and still the plinths upon which the pillars rest are as high as the Virgin’s form and the die of the stone on which she sits, and the human shape is but a pigmy in those colossal surroundings. We might fancy that such a massive edifice on so large a scale would needs crush the figures and spoil them of their grandeur; but whoever should fancy this would misjudge Titian, who knew how to temper all this vastness and fetter the eye to the parts upon which it is required to be fettered, on the group

of the Virgin and her noble band of adorers” (Life and Times, i, 306).

27 Mirella Levi D’Ancona has identified them as the “Gate of Heaven” (The Iconography of the Immaculate Conception [Monographs on Archaeology and Fine Arts of the College Art Association of America, vii ] [1957], 70, n. 162), while E. Forssman suggests that they may represent the columns Jachin and Boaz of Solomon’s Temple (“Über Architekturen in der venezianischen Malerei des Cinquecento,” Wallraf-Richartz Jahrbuch, xxix [1967]: 108). Levi d’Ancona’s elaborate interpretation of Saint Peter’s supposed single key and Sinding-Larsen’s refutation (“Titian’s Madonna,” 140, n. 1) are both based on a false premise: there are in fact two keys in the Pesaro Madonna, one leaning against the riser of the step, the second lying on the tread at St Peter’s foot. The second key is hardly discernible in photographs but is recorded in all the graphic copies of the painting. For further comment on iconographic interpretations of the Pesaro Madonna, see below, note 35.

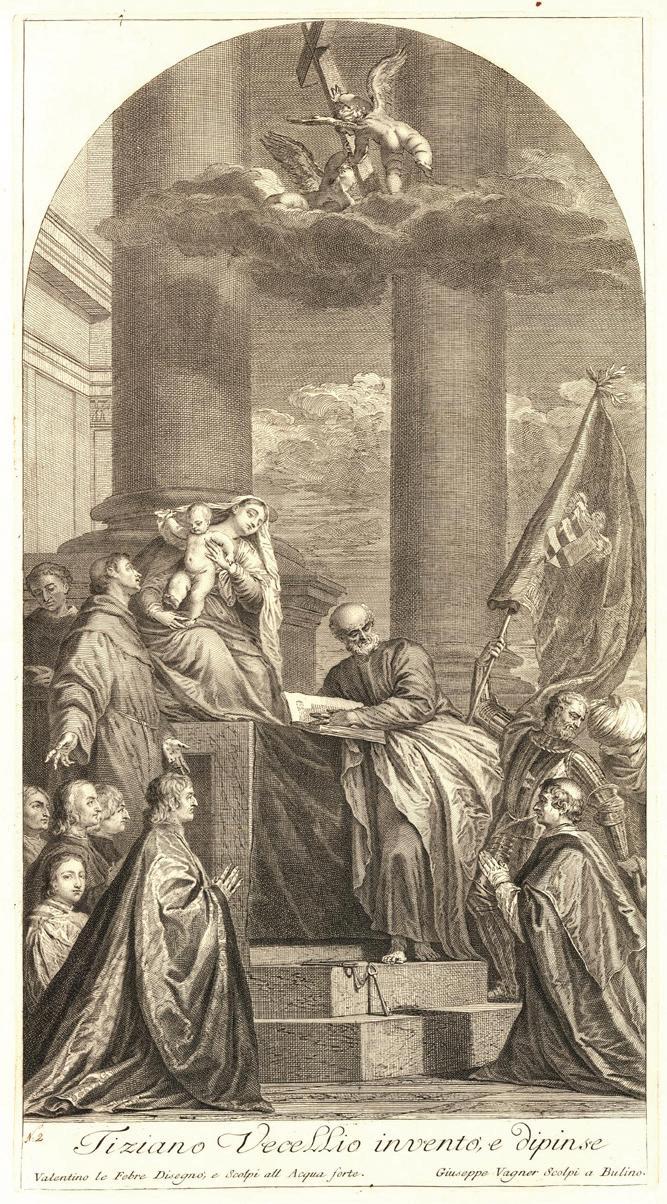

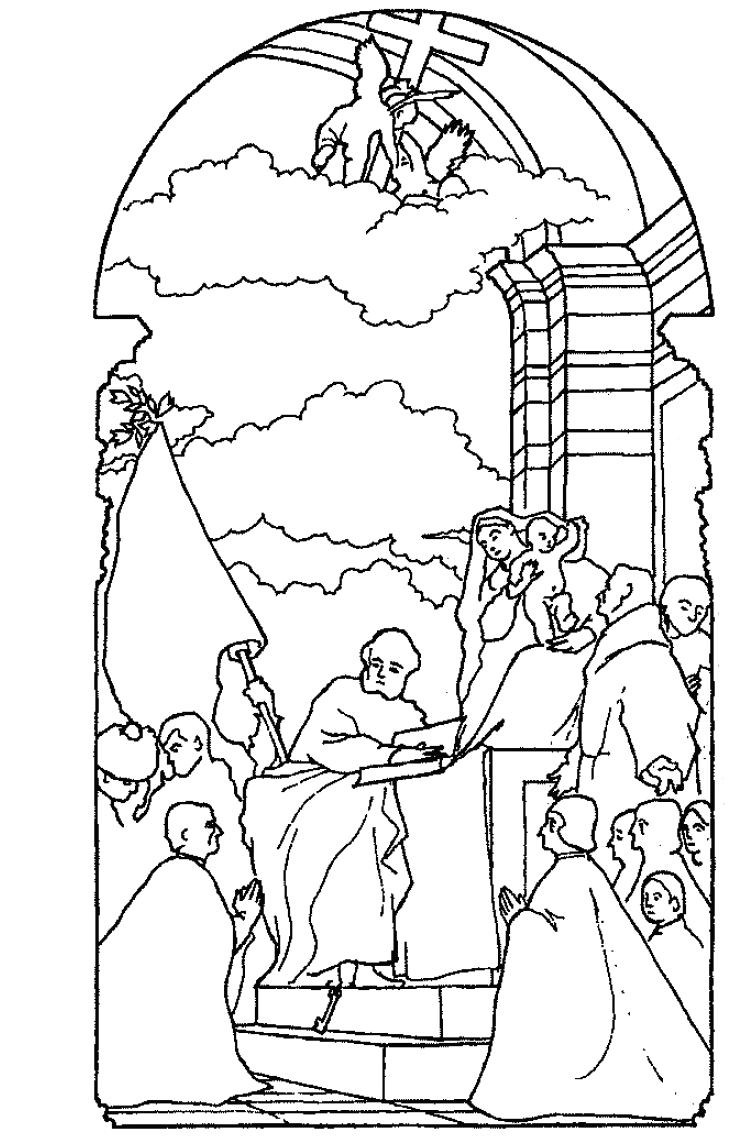

from an unsuspected source, copies after the painting; for several of the copyists apparently felt the need to correct, albeit in minor ways, the architectural setting of the Pesaro Madonna In Valentin Lefebre’s etching of 1680, the earliest known record of the columns, small adjustments were made to reduce the massiveness of the columns and minimize the fragmentary nature of the wall.31 A revised and expanded edition of Lefebre’s graphic anthology was published in the eighteenth century, and his copy of the Pesaro Madonna was in turn engraved by Giuseppe Wagner (Fig. 17).32 Evidently even more disturbed by the vestigial wall, Wagner added a new section to it above the entablature—thereby eliminating the embarrassing segment of sky, if not really resolving the architectural dichotomy.33

A more radical solution to the problem is offered by a painted copy after the Pesaro Madonna (Fig. 18), which was originally published as a preliminary sketch for the altarpiece.34 Owing to its general rejection as an autograph, this small

28 A thorough technical examination of the painting would undoubtedly help to resolve some of these problems. At this point, however, I would like to confirm Sinding-Larsen’s observation on the paint surface: “When the upper part of the picture is examined under reflecting light, it appears that most of the dark cloud as well as the columns present a glittering, densely shining surface, whereas the surroundings, including the putti, remain relatively opaque” (“Titian’s Madonna,” 144).

29 Ibid., 147. An earlier alteration to the Pesaro altar itself dates from 1582, when the entablature was inscribed gregoriano, commemorating the granting of privileges by Pope Gregory xiii and the additional participation at the altar of the Scuola dell’Immacolata; this was done upon the petition of Carlo Pesaro, Bishop of Torcello. A plaque on the pier opposite the altar records the full particulars (see Soravia, Le chiese, ii, 132 ff.); the inscription below, which had been covered in the nineteenth century, indicates the confirmation of these privileges by Pope Benedict XIV in 1751.

30 Cf. Dolce, Dialogo, 203; Vasari, Vite, vii, 436; the “Anonimo del Tizianello,” Breve compendio della vita del famoso Tiziano Vecellio (Venice, 1622) (unpaginated); and Ridolfi, Maraviglie, 1, 163 f.

31 These adjustments were noted by Sinding-Larsen, “Titian’s Madonna,” 144, n. 3. Lefebre’s etching (not engraving) appeared in his popular Opera selectoria, qvae Titianvs Vecellivs Cadvbriensis, et Paulus Calliari Veronensis inventarvnt, ac pinxervnt . . ., published in 1680; a second edition followed in 1682 with many more thereafter. On the later editions, see G. Moschini, Dell’incisione in Venezia (Venice, 1924), 52 ff.

32 Opere scelte, dipinte da Tiziano . . . e scolpite all’acquaforte da Valentino le Fevre . . . ora finite a bulino sopra gli originali . . ., (Venice, 1740); expanded in 1789. For this publication, see Moschini, Dell’incisione, 66.

33 Another adjustment made in the graphic copies offers still a further critique of the revised Pesaro Madonna, where the cross of the angels is rather uncomfortably wedged into the space between the two columns. To open this congestion Lefebre turned the cross into space, thereby freeing it from the imposed constraint. This small but significant change was pointed out to me by the painter Willard Midgette.

34 Godefridus Johannes Hoogewerff, “Un bozzetto di Tiziano per la ‘Pala dei Pesaro’,” Bolletino d’arte, vii (1927–28): 529 ff. The painting is now in the collection of Professor A. Richard Turner, Middlebury, Vermont.

35 Erica Tietze-Conrat, “The Pesaro Madonna, A Footnote on Titian,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, xlii (1953): 177 ff. The debate over the interpretation of Titian’s painting as an image of the Immaculate Conception has become by now somewhat gratuitous. Mrs. Tietze no doubt overstated her case, but there is no reason to reject it totally, since, as Sinding-Larsen notes, the idea would “normally be inherent in any figure of the Virgin” in a Franciscan church from the late fifteenth century on (“Titian’s Madonna,” 139 f.). Cf. also Eva Tea, “La Pala Pesaro e la Immacolata,” Ecclesia, xvii (1958): 605 ff., and idem, “lconografia della Immacolata in Italia e in Francia,” in Actes du xix e Congrès International d’Histoire de l’Art (Paris, 1959), 283 f.

canvas, probably dating from the eighteenth century, had been forgotten until Erica Tietze-Conrat, noting the addition of a third figure to the group of SS. Francis and Anthony, cited it in support of her iconographic reading of Titian’s design as a supposedly disguised Immaculate Conception.35 Mrs. Tietze’s argument was not much strengthened by her observation here, since the additional figure seems a necessary response to the wider format of the copy. A more interesting deviation from the original, however, concerns the architecture. The copyist again seemed to sense some disparity between the columns and the polychrome wall, and he “corrected” his model by removing the marble revetment, thereby opening the wall—rather like the back of the throne in Giovanni Bellini’s Coronation of the Virgin in Pesaro. He thus reduced the sheer physical conflict between the architectural elements, and by adding a landscape view in the resulting open frame he provided a spatial background more accommodating to the broad plasticity of the columns. While offering no absolute proof of the later addition of the columns, the various copies, comprising an implicit critique of the revised edition of the Pesaro Madonna, attest to a tradition of negative response to the architecture of the altarpiece.

The theory that Titian himself made no change in his own composition has found little acceptance, although those rejecting it have not, so far, responded with substantial counter-argument.36 Art historians, mostly in private discussions of the problem, have followed Sinding-Larsen’s own, perhaps too limited approach, considering the Pesaro Madonna rather exclusively in relation to other asymmetrical sacre conversazione and votive pictures of the Venetian cinquecento. Couched in those terms, the issue remains one of precedent: did Titian in fact initiate the tradition of “oblique Madonnas” with asymmetrically placed columns, or should more credit go to an artist like Veronese?37 The various examples of this compositional type occurring before Veronese’s Giustiniani Madonna, however, render the TitianVeronese alternative something of a false issue.38

Those who maintain that the Pesaro Madonna columns are Titian’s own invention adduce as proof of the altarpiece’s tremendous influence in the sixteenth century the numerous Venetian paintings with columnar elements or, outside Venice, Lodovico Carracci’s Bargellini Madonna—in all of which, it should be noted, the columns function in a convincingly structural and intelligible manner. Yet it is a remarkable fact that the most exciting feature of the present architectural setting, the spatial extension created by the cloud floating before the columns, is nowhere repeated in any other sixteenth-century composition.39

Indeed, the motif does not seem to have had any appreciable effect until the eighteenth century, in Tiepolo’s Sacrifice of Iphigenia in the Villa Valmarana. The group of putto and deer descending upon a cloud passing before columns pays full

36 Erik Forssman merely finds it inconceivable that in Venice one would ever have tampered with a work by Titian (“Über Architekturen,” 138, n. 5a). Wethey contents himself with rejecting SindingLarsen’s suggestion as “a subjective opinion devoid of historical or reasonable basis” (The Religious Paintings, cat. no. 55). To my knowledge, the only published acceptance of the thesis is by Horst Woldemar Janson (History of Art [New York, 1964], 372). Rodolfo Pallucchini lists the article in the bibliography of his monograph but makes no reference to it in his text; his enthusiastic description of the columns, however, leaves no doubt of his full acceptance of them as genuine (Tiziano, 1, 63). Francesco Valcanover takes impartial note of

Sinding-Larsen’s study (L’Opera completa di Tiziano [Milan, 1969], No. 128).

37 Sinding-Larsen, “Titian’s Madonna,” 146.

38 Cf. Sinding-Larsen’s own list of examples (ibid., 142 f., n. 3) and the discussion, focusing on Pordenone, in Christian Lenz, “Veroneses Bildarchitektur,” Ph.D. diss., Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat (Munich, 1969), 117 f. (kindly brought to my attention by Dr. Wolfgang Wolters).

homage to the Pesaro Madonna in its revised state—as a fully Baroque rather than proto-Baroque conception.40

The argument thus far has been concerned with the Pesaro Madonna in its present form. Transferring our attention to the overpainted initial composition, however, may yield a more profitable approach to the whole problem. Following the indications of Wolf’s analysis, Sinding-Larsen offered a reconstruction of the presumed original design of the painting, upon which our schematic rendering is based (Fig. 19).41 In this state the sacra conversazione takes place beneath a coffered barrel vault which rises from the wall behind the Virgin. In style and decorative detail the architectural setting is an extension of that of the surrounding frame— and, as we have mentioned, it also matches the contemporaneous wall tomb of Jacopo Pesaro. Titian’s composition, then, would have effected a union of real and fictive space by relating the actual architecture of the altar and the painted architecture of the composition. Hardly a radical innovation, it continued, with significant modification, an earlier tradition deriving ultimately from Masaccio and best known in Venice in the altarpieces of Giovanni Bellini. The earlier paintings, in which the depicted space of the altarpiece is conceived as a continuation of the chapel itself, maintain a fairly strict symmetry both in architectural setting and in the central placement of the holy figures, a symmetry which generally followed the main axis of the chapel in which they stood.

Titian’s asymmetrical composition is usually hailed by critics as a bold and innovative step in the development of the altarpiece—and it surely is. But the motivation for such a significant modification of tradition, which has theological as well as aesthetic implications, can hardly be ascribed to artistic adventurousness alone. Sinding-Larsen has properly introduced into the discussion the tradition and concept of the votive picture, for the Pesaro Madonna, with its six portraits, is indeed an altarpiece cum votive picture. The prominence accorded the members of the family assures them a significant role in the working of the composition as a cult image. They are aligned parallel to the picture plane and are seen in pure profile, except for the illuminated face of young Leonardo Pesaro;42 turning to the observer, he effects the only direct psychological contact between painted world and reality. The holy figures and saints are concerned exclusively with the adoring Pesaro, and it is through this noble family that the outsider eventually gains access to the Virgin and Child.

Viewing this phenomenon, with its narrative emphasis upon the experience of the donor and his family, as a radical rupture of the traditional relationship between worshipper and image, Sinding-Larsen has interpreted the asymmetry of the vaulted architecture as a reinforcement of the dramatic autonomy of the picture, a further denial of access to the observer. He writes, “in the representations [in altarpieces] where a donor or a particular saint is presented to the enthroned

39 In Pordenone’s Cortemaggiore altarpiece of the Immaculate Conception (Giuseppe Fiocco, Giovanni Antonio Pordenone [Udine, 1939], Pl. 138), not mentioned by Lenz, a small group of cloud-borne angels does indeed pass before a column, but, in comparison to the massiveness of the figures below, the motif exists as a minor pictorial incident, lacking the spatial impact of the revised Pesaro Madonna In Jacopo Bassano’s Sant’Eleuterio altarpiece (Sandra Moschini Marconi, Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia, opere d’arte del secolo xvi [Rome, 1962], cat. no. 11) the glory of clouds also overlaps the columns, but the inspiration here, particularly with regard to the cloud-supporting angels, comes rather from Titian’s Assunta

40 The dark cloud before the columns in the Pesaro Madonna is indeed “un-Titianesque in its smoky diffuseness” (Sinding-Larsen, “Titian’s Madonna,” 142). One need only compare it to the firm plasticity of the clouds in the Assunta, clouds capable of functioning as supporting elements, to appreciate the effect of the repainting.

41 Ibid., Pl. iv. In our diagram (Fig. 19) I have deliberately avoided the problem of filling in the pattern of architectural ornament; I trust that future technical examination of the painting will offer surer guides in this reconstruction.

42 Although the young son of Antonio Pesaro is more usually identified as Giovanni, I follow Fogolari (I Frari, xxi and Pl. 17) and Sartori (Frari, 27) in calling him Leonardo—who was born in 1508 and thus would have been of the right age for the image in Titian’s composition. Louis Hourticq was evidently so struck by the beauty of this young face that he described it as “une toute jeune fille” (La jeunesse de Titien [Paris, 1919], 192). For the identity of the other members of the Pesaro family, on which there is also some disagreement, cf. Zanotto, Pinacoteca veneta, 11, No. 81, and, most recently, Pallucchini, Tiziano, 1, 260.

Madonna, ‘modern’ artists found an occasion to create a story which both by virtue of its selfcontainedness and by its dramatic or momentary character emphasized the participation of the person presented. When in Titian’s Pesaro Madonna even the vault architecture was reoriented so as to disconnect the depicted room from the room of the church, this was the final step in transforming the altar-image into a window through which the events of another world could be seen.”43 I propose that Titian’s vaulted setting was designed for precisely the opposite purpose, namely, to assure the apparent spatial continuity between the two realms and to guarantee constant access, as it were, to the fictive space.

Without the columns the asymmetry of the Pesaro Madonna was much more conspicuous. The receding orthogonals of the background architecture must have accentuated the oblique perspective construction. This emphasis on the orthogonals is relatively rare in Titian’s architectural spaces and would seem to lend some particular importance to the perspective in this case.44 The vanishing point lies beyond the frame of the picture to the left,45 indicating an ideal vantage point to the left rather than directly in front of the picture. Now, there are no actual side chapels, enclosed independent spaces, along the nave of the Frari (Fig. 13). The Pesaro Madonna, above an altar against the wall, is visible to an observer as he moves down the nave of the basilica toward the choir. And it is precisely this approach, previously considered by Titian in his conception of the Assunta on the high altar, that the composition of the Pesaro Altarpiece recognizes. One’s first view of the painting is from an angle (Fig. 20), and the design itself is constructed to accommodate this oblique view.

Because of its site the Pesaro Madonna must function both as a wall painting, continually visible from a variety of angles as one passes down the nave, and as an altarpiece, to be approached frontally on a central axis when one worships at the Pesaro altar. As a wall painting, the asymmetry and obliquity of Titian’s composition render it accessible from the left; the orientation of the steps to the Virgin’s throne, originally reinforced by the background wall and crowning vault, invites entrance from the side. The holy figures naturally follow this general arrangement. But the narrative sequence within the picture functions with respect to a frontal approach, the viewer facing the altar directly. The grouping of the Pesaro family— Jacopo Pesaro on the left, the others on the right—subtly modifies the obliquity of the spatial structure; the balance of the two groups creates a certain centrality within the asymmetry of the design. Further, their profiled parallelism at first establishes a barrier at the level of the picture plane—the surface tension of which is broken only by the boy’s face—but this simple tableau parallelism is only apparent. The situation is significantly complicated by the isolation of Jacopo Pesaro, who is located farther back in space than his relatives—leaving open an area of pavement, a space which affords the first step into the painting from the oblique approach. Before the altar, however, our own immediate involvement in the painting follows a different direction, from right to left. Beginning with our encounter with the youngest Pesaro, we look to the left with his elders to the leader of the clan. Jacopo Pesaro, in turn, faces to the right, presented to the Virgin by his special patron, Saint Peter;46 this is the main dramatic action in the painting, complemented on the right by the gesture of Saint Francis, who presents the rest of the

43 Sinding-Larsen, “Titian’s Madonna,” 157.

44 The Malchiostro Annunciation in Treviso, contemporaneous with the Pesaro Madonna, offers another example of such spatial emphasis. See below, note 75.

45 As nearly as one can determine, the orthogonals do not in fact recede to a precise point, but rather to a focused area—which does not really affect our analysis.

46 Pallucchini unaccountably identifies the iconographically essential Saint Peter as Saint Joseph (Tiziano, 1, 63).

47 Sinding-Larsen interprets this resolution as a kind of hesitation on Titian’s part: “It must be regarded as a concession to a time-honoured convention when, in the figure of Saint Peter, Titian granted the picture at least a relic of a ‘frontal enthroned’ at which the more conservatively minded onlookers could direct their eyes. In this way the new composition appeared less provocative” (“Titian’s Madonna,” 158).

48 This effect is a hallmark of Titian’s work during this period; cf. in addition to the Assunta, the Bacchanal of the Andrians, a painting contemporaneous with the Pesaro Madonna

49 The documents concerning Titian’s death and burial on the following day were published by Giuseppe Cadorin, Dello amore ai Veneziani di Tiziano Vecellio (Venice, 1833), 95, docs. L, M.

family to the Christ child. Saint Peter occupies the pivotal position in the design as the only figure on center; looking down and to the left while moving toward the Virgin at the right, he is the only one of the sainted figures completely open to the viewer. Out of this large-scale contrapposto of action, gesture, and glance emerges a self-contained dramatic situation which resolves the two different modes of approach in a synthesizing composition of extraordinary balance—acknowledging all the while the validity of both.47

In the restricted space of an enclosed chapel an altarpiece is generally perpendicular to the main axis of approach, and the movement of the observer is controlled to some extent by the confines of the actual architecture. The Pesaro altar, however, is actually parallel to the initial line of approach, the longitudinal axis of the Frari itself, and the observer enjoys a great latitude of unrestricted movement. The dynamics of Titian’s composition, then, are not a deliberate assault upon aesthetic and theological tradition but represent rather a response to the challenge of a particular site. Titian’s aim was not to “disconnect” the depicted space of the painting from that of the church but to maintain a spatial continuity under rather special, open circumstances.

The addition of the columns thus destroyed not only what must have been an exciting pictorial effect of the figures silhouetted against the glowing sky48 but the very functionalism of Titian’s design, its spatial flexibility. The columns cancel the recession of the original architecture and tend to offset the asymmetry of the composition. It seems quite improbable that Titian himself would have so seriously impaired the effectiveness of his own conception.

The third altarpiece Titian designed for the Frari was never installed (Plate 20). Intended to stand above the altar where the master was to be buried, the Pietà remained in his studio, unfinished, when he died on 27 August 1576.49 The artist had made arrangements for a tomb at the Altare del Crocefisso in the Frari (F in Fig. 13), in return for which he agreed to paint the altarpiece. The project seems to have been abandoned, however, possibly because the monks hesitated to tamper with that particularly venerated altar, the site of a miraculous Crucifix. For all this Ridolfi is our main source of information.50 The earlier account of the socalled Anonimo del Tizianello makes no mention of the Pietà but notes that Titian

50 Ridolfi, Maraviglie, 1, 206: “Haueua anco dato principio ad vna tauola col morto Saluatore in seno alla dolente Madre, à cui San Girolamo seruiua di sostegno, e la Maddalena con le braccia aperte si condoleua, che disegnaua por Titiano nella Cappella del Christo nella Chiesa de’ Frari, ottenuta da’ Padri con patto di farui quella pittura; ma portandosi la cosa in lungo ò perche, come altri dicono, non vollero quelli perder l’antica diuotione del Crocefisso, che vi si vede, non vi diede fine […].” That the Cappella del Christo or del Crocefisso was indeed a venerated site in the Frari is attested by Sansovino in his 1581 guidebook: “Vi si honora parimente il Christo miracoloso situato à mezza Chiesa, à cui piedi è sepolto quel Titiano, che fu celebre nella pittura, fra tutti gli altri del tempo nostro” (Venetia, ed. 1663, 188). In 1579 the altar was conceded to the Confraternita della Passione (Soravia, Le chiese, ii, 19).

51 “Anonimo del Tizianello,” Breve compendio: “Morì finalmente il gran Titiano di età d’anni 99, & fù sepolto nella Chiesa de’ Frari di Venetia, chiamata la Ca’ Grande all’Altare del Crocefisso, benche hauesse morendo ordinato di douer esser sepolto, nella Chiesa Archidiaconale della sua Patria, nella sudetta Capella della sua vera Famiglia, ma ciò non seguì perche s’interpose una mortifera pestilenza, che non lasciò essequire in questo l’ordinatione di lui […].” Evidently following this passage, Laurie Schneider has assumed, wrongly, that the painting itself was placed in the family chapel at Cadore (“A Note on the Iconography of Titian’s Last Painting,” Arte veneta, xxiii [1969], 219, n. 1).

52 Ridolfi, Maraviglie, 1, 209: “Onde d’anni 99 terminò il viaggio della vita, ferito di peste il 1576 e benche fossero vietati ad ognuno i funerali, gli furono dall’autorità de’ maggiori conceduti gli honori della sepultura; e nella Chiesa de’ Frari à piè dell’Altare del Crocefisso, come