Sangallo and Antiquity

CHRISTOPH LUITPOLD FROMMEL

I The Study of Ancient Monuments before 1513

b runelleschi A n D AlberT i

Since the fourteenth century, and probably even earlier, artists had drawn and measured ancient monuments, and in so doing prepared the ground for the renewal of architecture.1 But the first artist reported to have measured Roman monuments systematically was Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446): “… levassono [together with the young Donatello] grossamente in disegno quasi tuttj gli edificj di Roma e in molti luoghi circustanti di fuorj colle misure delle largheze e alteze….”2 For Brunelleschi the architecture of the ancients was the only legitimate kind—it was architecture true and pure. He went to great efforts to secure a translation of the most important chapters of Vitruvius’s treatise, the only surviving text to present a systematic idea of ancient architecture, so that he might understand better the character, vocabulary, and syntax of ancient architecture.3 In Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) he found someone of equal stature, someone with similar humanistic and artistic convictions, who would lay the theoretical foundation for the future development of architecture.4 Even though architecture did not become Alberti’s main interest until the 1440s, his humanistic education and intensive study of the ancient monuments equipped him to understand Vitruvius fully for the first time since antiquity. He began collecting every available text on architecture ; studied the monuments of imperial Rome, which Vitruvius could not yet have known ; and in a systematic Aristotelian fashion developed his findings into his own treatise De re aedificatoria, which he presented to pope Nicolas V in 1452. In this work he sketched out the ideal image of an ancient city, which he and many another longed to revive, and by comparing Vitruvius’s theory with the actual monuments, laid the foundation for the

studies of Francesco del Borgo, Giuliano da Sangallo, Francesco di Giorgio, Bramante, Raphael, Peruzzi, Palladio and, last but not least, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger.

Alberti criticised Vitruvius’s language and obscurities and did not hesitate to modify his norms whenever the monuments or other writers offered something more convincing. His persistent goal, in practice as well as in theory, was to assist in the rebirth of antiquity and thus to establish the preconditions for a new kind of life in the style of the ancients. His few buildings demonstrate that he was able to do this because he brought the habits and functions that had developed in the course of the Middle Ages into harmony with ancient types and forms. He found compromises that could, on the one hand, satisfy patrons and accommodate the changed artistic practices of his time and, on the other, transform these habits as far as possible into more antique ones.

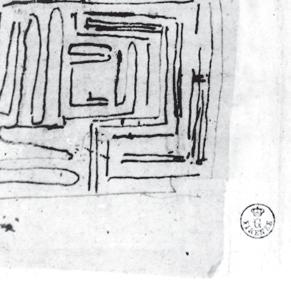

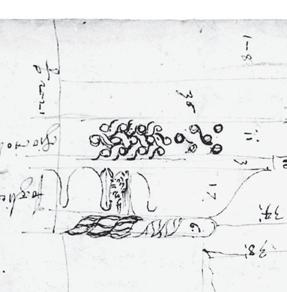

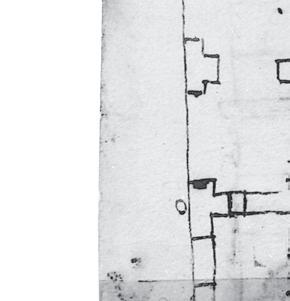

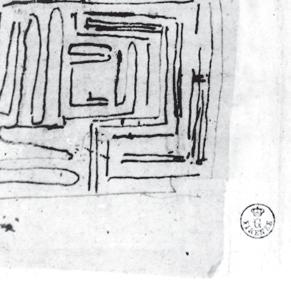

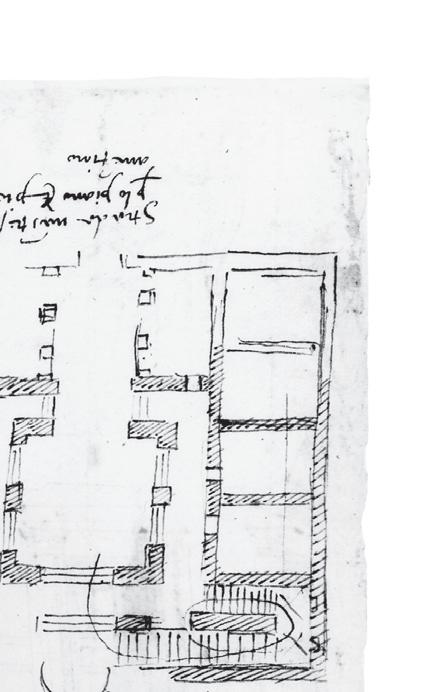

Alberti’s drawing of a bath complex, probably a fragment of a villa project, already shows an attempt at such a compromise (Fig. 1).5 It corresponds only partially to the “balinearum dispositionum demonstrationes” in the tenth chapter of Vitruvius’s fifth book, but the archaic manner of the drawing, the many parallels with the De re aedificatoria and the shallow niches at the end of the ambulatory, which recall Brunelleschi, argue for an early date around 1450. Evidently, Alberti was trying to reawaken the appetite of his wealthy contemporaries for the benefits of bathing, sweating, massaging, and anointing by incorporating a few functional rooms in villas or palaces with open views and loggias suitable for all seasons.6 It was the start of a new bathing culture, which would afterwards be revived about 1480 in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino and a little later at the Rocca of Ostia, and which would culminate in Bramante’s project for the Cortile del Belvedere and Raphael’s design for the Villa Madama.7

At the same time, shortly before 1450, Alberti started to win over to his ideals some of the most important architectural patrons in Italy. The result was the onset of an age that gave

7

itself as unreservedly as possible to the promptings of ancient art, trying wherever feasible to emulate it. As heir to Alberti and Bramante, as colleague of Raphael and as Palladio’s most important precursor, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger occupies a central place in this development. His rich store of almost two thousand architectural drawings affords perhaps the most complete idea that we have of the goals and problems of Renaissance architects and the astonishingly rapid changes that occurred in their understanding of antiquity.8

choice AnD mAnner of rePresenTATion before sAngAllo

The representation of architecture in plan, elevation, cross-section, and perspective views can be traced back as far as Villard de Honnecourt’s pattern book of around 1230 and is ultimately of antique origin.9 Brunelleschi learned these representational methods, which in the meantime had been perfected in the builders’ guilds, probably in the workshop of Florence Cathedral, and from him they were picked up by the young Alberti. Jacopo della Quercia’s project for the Fonte Gaia in Siena shows how far perspective had arrived in 1408,10 while Ghiberti’s drawing for the niche of St Stephen for Orsanmichele in Florence indicates that the combination of orthogonal elevation and perspective was already in use at the time.11 The drawings of the somewhat amateurish Ciriaco da Ancona, which we know primarily from copies and which must have been inspired by the more professional drawings of Brunelleschi, Alberti, Donatello or Ghiberti, convey an idea of how ancient

8

Fig. 1 Leon Battista Alberti Fragment of a design for a villa with bath complex (Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Codex Ashburnham 1828, App., fol. 56 v.f., photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana –Max Planck Institute for Art History)

Fig. 2 Leon Battista Alberti Project for the high altar of S. Lorenzo in Damaso in Rome (London, British Museum, 1860,0616.38, photo: British Museum)

buildings were drawn in the first half of the century.12 The use of wash for contrasts of light and shade, the employment of perspective, and the delight in such details as the figural elements and fragments of architecture in the foreground of his drawings all prepare the way for Mantegna, Bramante’s Prevedari engraving and Giuliano da Sangallo’s late drawings.

Although Alberti restricts himself in the plan of the bathing complex to a simple outline of the walls and omits all decoration, he works to scale and shows a professional knowledge of the proportions and wall thicknesses required for rooms undoubtedly meant to be vaulted (cf. Fig. 1). Alberti would eventually develop his graphic capabilities to such an extent that even from a distance he could direct building sites in detail. Filarete’s treatise from the early 1460s is also evidence that even before Alberti’s death Florentine architects were using highly sophisticated methods of representation, such as the perspective cross-section.13

Elevation drawings by Alberti from these years were probably similar to that of the project for cardinal Scarampi’s funeral altar in San Lorenzo in Damaso in Rome, which may be autograph (Fig. 2).14 Since Scarampi died in 1465, the drawing is datable to Alberti’s time and we do not know of any comparable example of the preceding decades. The drawing is orthogonal and drawn with ruler and compass. Only the altar table, the central opening with coffered vault, the lateral shell niches, and some pilasters are foreshortened. Though this combination of orthogonal and perspective drawing does not fully correspond to Alberti’s own principles of pure orthogonality, it goes far beyond Ghiberti’s niche for St Stephen. Both architecture and ornament are of the calibre of Alberti’s last years, and the drawings of his late projects may not have been very different.

Some of the few preserved drawings of this early period, and perhaps even some by Brunelleschi, could have ended up in the library of Piero de’ Medici, who already in 1456 had sent draughtsmen to Rome and owned three volumes of drawings after the antique.15

The “ l ibro Piccolo” A n D T he “TA ccuino s enese”

One of Alberti’s first direct followers in architecture was undoubtedly Giuliano da Sangallo (ca. 1445–1516).16 During his training as a carpenter and woodcarver, he had witnessed the completion of some of Brunelleschi’s and Alberti’s Florentine buildings. It is likely that the Medici took an interest in furthering the education of the young artist, who was to become the most talented Florentine architect of his generation. They may even have sent him to Rome to meet Alberti, with whom they had close connections

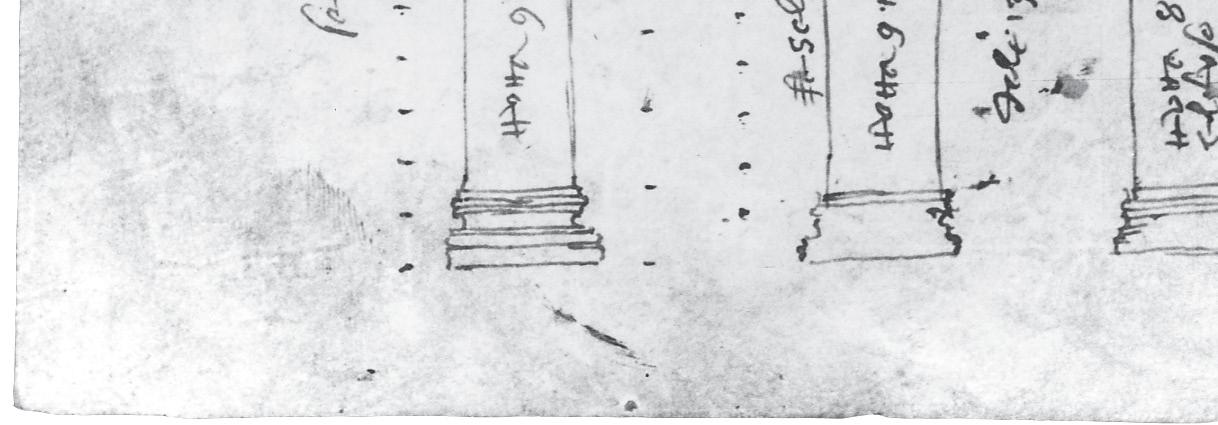

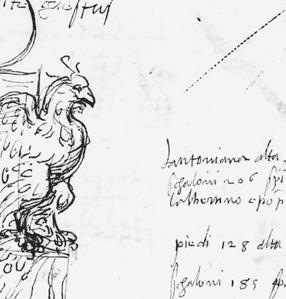

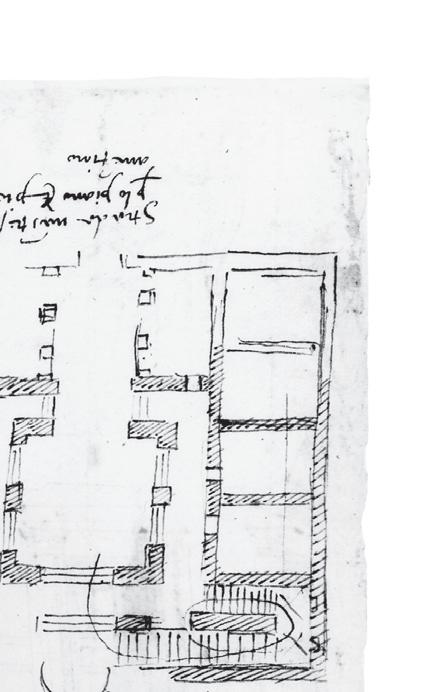

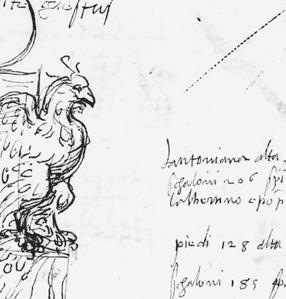

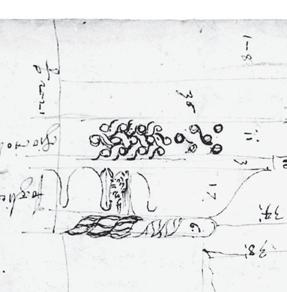

and who had already inspired so many artists. Giuliano profited more than anyone else from Alberti’s understanding of ancient monuments, his methods of representation and his reconstructions. By his own testimony, Giuliano began surveying the monuments of Rome as early as 1465, and the studies of capitals, bases and cornices in the “Libro Piccolo” of the Codex Barberini, which are still similar to the drawings of the circle of Benozzo Gozzoli, may go back to these early years (Fig. 3).17 To most Quattrocento painters and sculptors such details of antique architecture were more important than surveys of entire monuments. In the “Taccuino Senese,” which is datable only after the late 1490s, Giuliano dedicated attention to entire surveys, such as those of ancient centralized buildings, above all mausolea in the environs of Rome and Naples, some of which Brunelleschi and Alberti had already discovered as important sources of inspiration and which Giuliano may have visited when presenting a model to the king of Naples in 1489, or even earlier (Fig. 4).18

The city-view panels in Berlin, Urbino and Baltimore from about 1480–1510 are probably Giuliano’s invention and demonstrate the evolution of his virtuosity, not only in representing architecture in convincing perspective and lighting, but also in combining the language and typology of antiquity with that of his own time in an urban context.19

9

of g iuli A no DA sA ng A llo

Fig. 3 Giuliano da Sangallo Views of antique capitals (Biblioteca Vaticana, Codex Barberini 4424, fol. 14 v., “libro piccolo” ; photo: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana)

10

Fig. 4 Giuliano da Sangallo Ground plans of antique mausoleums (Siena, Biblioteca Comunale, S.IV.8, fols 16 r. and v ; photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History)

Fig. 5 Andrea Mantegna Padua, Eremitani Church, Ovetari chapel, frescoes with the history of St James 1448–57, Detail (photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History)

Fig. 6 Giuliano da Sangallo Groundplan and perspective view of the exterior of the Colosseum (Biblioteca Vaticana, Codex Barberini 4424, fol. 12 v., “libro piccolo”). (photo: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana)

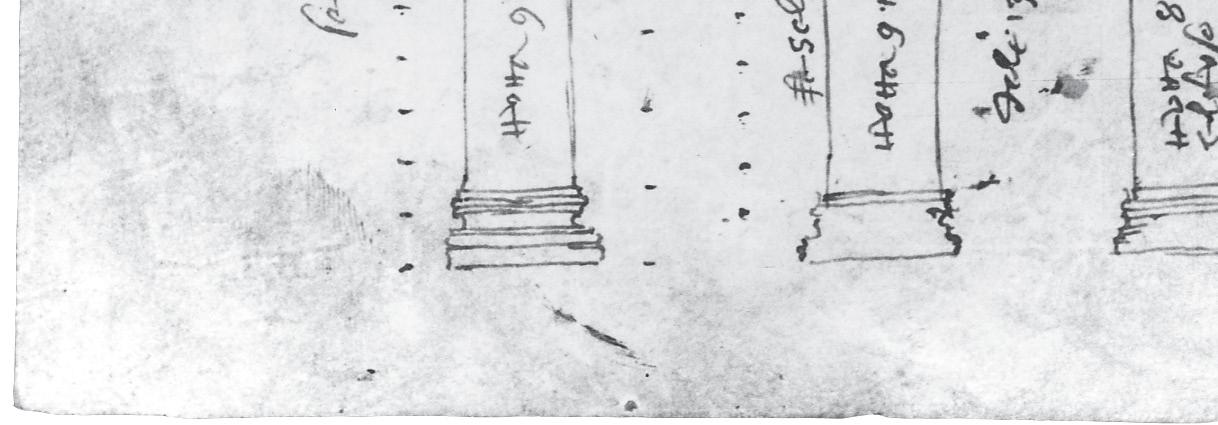

Fig. 7 Giuliano da Sangallo Elevation of the three orders (Siena, Biblioteca Comunale, Taccuino, Codex S.IV.8 , fol. 6 r.).

(photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History)

As he did with wooden models, Lorenzo de’ Medici may have ordered them as gifts for prominent princes whom he wanted to encourage to build in the new classical style. In the Baltimore panel the plan of the Colosseum is already oval20 and the perspective is centred on one of Giuliano’s magnificent triumphal arches which appear only in his Taccuino Senese.21 Its rhythm seems to be inspired by the arch of Gallienus22 and is more complex than that of the arches which Botticelli and Perugino had painted in the early 1480s in the background of their Sistine Chapel frescoes.

Alberti must have already measured some triumphal arches when he designed the facade of the Tempio Malatestiano in around 1450, and some years later he probably also studied the triumphal centrepiece of the Castel Nuovo at Naples.23 In the interior of S. Andrea in Mantua he used the triumphal motif for the first time in sequence, the so-called “rhythmic travée,” and made it one of the most successful articulating devices in post-medieval architecture. Reflections of the rediscovery of the triumphal arch can be seen also in the young Mantegna’s frescoes in the Ovetari chapel at Padua, and in the work of Jacopo Bellini and Bonfili and others (Fig. 5).24 In the first two decades of the sixteenth century Giuliano, Gian Cristoforo Romano, Bernardo della Volpaia and Peruzzi strove to make increasingly precise drawings of triumphal arches.25 In the drawings of Bramante and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, however, they play a relatively minor role.26

Giuliano’s Taccuino Senese includes small surveys of his projects for the Piccolomini chapel of Siena cathedral (1481), the villa at Poggio a Caiano (1485), Santa Maria delle Carceri (1485) and the palace of the king of Naples (1489), which he must have copied from earlier drawings.27 On the last page of the Taccuino he mentions the completion of the dome of Loreto in 1500 and the death of a certain “Lorenzo di Pietro” in 1503, and as late as 1513 he added a measurement to the plan of the Colosseum.28 In view of these dates, the Taccuino thus provides what is probably the most concrete idea of the state of knowledge of antiquity at the time when Antonio da Sangallo moved to Rome. As in the earlier “Libro Piccolo” (Fig. 6) the methods of representation range from ground plans and orthogonal elevations with some perspective detail (Fig. 7), to perspective cross-sections and perspective exterior and interior views such as those of the Piccolomini chapel, the Colosseum or the “bagno di Viterbo.”29 Drawing the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders Giuliano also demonstrated a solid knowledge of Vitruvius and Alberti (Fig. 8). There he noted Vitruvius’s various intercolumniations, the tapering of the entasis, and the enlargement of the architrave with the increasing height of the orders.30 Like Alberti, he gave the Doric order a proportion of 1:8 and devoted special care to the Ionic order,

whose proportions, as in Vitruvius, fluctuate between 1:8 and 1:9. He reconstructed its capital, base, and entablature ; and like Francesco di Giorgio in the same years, noted the translation into Italian of the Vitruvian terms.

According to Vasari, Giuliano’s pupil Simone Pollaiuolo, known as il Cronaca (1457–1508), was one of the most competent draughtsmen of ancient buildings.31 He started as a stonemason and may have collaborated in the eighties with Andrea Bregno at the Piccolomini chapel of Siena cathedral. Drawings of many details of Bregno’s executed work in the co-called Codex Strozzi by a hitherto unidentified draughtsman may have been copied after lost drawings of Cronaca.32

Only active as an architect in his own right from about 1490, Cronaca collaborated with Giuliano in 1493 on the vestibule for the sacristy of S. Spirito in Florence—perhaps the most classical building before Bramante’s Tempietto. In San Salvatore al Monte and the comparable church of San Pietro in Scrigno

11

Fig. 8 Giuliano da Sangallo Reconstruction of the Vitruvian orders. (Siena, Biblioteca Comunale, Taccuino, Codex S.IV. 8. fol. 31 v.). (photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History)

he was, however, more inspired by the detail of ancient prototypes than by their typology. The majority of his drawings after the antique are, in fact, limited to details and are clearly more akin to those in the Taccuino Senese of Giuliano, with whom he may have exchanged surveys, than to the mature parts of the Codex Barberini.33 Whatever the case, Cronaca was one of the pioneers of orthogonal drawing after ancient monuments. Thus, in his studies of capitals, like Giuliano in the Taccuino, he occasionally combines an orthogonal front view with a ground plan or side view (Fig. 9, Fig. 10).34 Orthogonal elevations of the Theatre of Marcellus and the Septizonium, and elevations of the Basilica Aemilia and the Arch of Constantine with perspective details in the Codex Strozzi and Raffaello da Montelupo’s sketchbook in Lille, have been also interpreted as copies after Cronaca. The latter was, however, much less able to follow Vitruvius’s more complex descriptions than Giuliano, as is shown by his reconstruction of the Doric portal.35

For a long time, the early architectural drawings of Peruzzi36 were attributed to Cronaca, whom he must have admired not only as both connoisseur and draughtsman of the antique, but also as architect.37 Peruzzi was however already inspired by Bramante not only in the orthogonal elevations with perspective details and strong chiaroscuro, which go far beyond Giuliano’s Taccuino, but also in wide-angle interiors such as the imposing drawing of S. Stefano Rotondo (Fig. 11).38 The fact that the influence of Giuliano and

Cronaca as well as Bramante can be felt in Peruzzi’s Farnesina, designed around 1505, also speaks in favor of dating these sheets to the beginning of Julius ii ’s pontificate.39

The surveys of the Roman sculptor Gian Cristoforo Romano (ca. 1460–1512), such as those of the arches of Constantine and Septimius Severus, are only known through copies.40 They are purely orthogonal and their combination with the plan, not drawn to scale, and their details without any perspective section recall Giuliano’s Taccuino. Gian Cristoforo was the son of Jesaia da Pisa, a sculptor who had been in contact with Alberti, trained in Rome and worked there until 1491. After having lived for many years in Milan and Mantua, Gian Cristoforo Romano was perhaps one of the sculptors—like Andrea Sansovino and Domenico Aimo da Varignana—brought to Rome by Bramante to fill the numerous niches in the Cortile del Belvedere with statues.41 When he was entrusted in 1510 with the execution of Bramante’s project for the basilica in Loreto, he must already have absorbed his method and vision.

In the 1480s, when Giuliano was at the height of his career, his brother Antonio the Elder (1460–1534) collaborated closely with him, and after Lorenzo il Magnifico’s death in 1492, when Giuliano had entered the service of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, Antonio the Elder became the preferred architect of the Borgias.42 In 1499 at the latest, he was commissioned to build the Rocca in Civita Castellana and

12

Fig. 9 Giuliano da Sangallo Ionic capital (Siena, Biblioteca Comunale, Taccuino, Codex S.IV.8, fol. 34 r., detail ; photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History)

Fig. 10 Simone Pollaiuolo , called il Cronaca . Ionic capital of the Baptistry, Florence (Montreal, The Canadian Center for Architecture, Castellino Group, fol. 5 r.). (photo: Bibliotheca-Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History)

must have gone there a number of times until the summer of 1503.43 He may sometimes have taken with him his promising nephew, Antonio the Younger, who would later direct the work after 1510 or even earlier. Antonio the Elder’s drawings of two castles, which may date from as early as the beginning of the 1490s, differ from Giuliano’s contemporaneous sheets, both in their less convincing bird’s-eye perspective and in their finely hatched modelling in ink.44 The orthogonal survey of the Hadrianeum on u 1407 A r with the solemn signature “… o DA s A ng A llo A rchi T e T.” is again reminiscent of Giuliano’s Taccuino and may be a copy after Antonio the Elder.45

b r A m A n T e’s D r Awings

In the pontificate of Julius ii the influence of Antonio the Elder, Giuliano and Cronaca on Antonio the Younger’s development was increasingly superseded by that of Bramante. When Bramante (1444–1514) moved to Rome late in 1499, he not only knew all the methods of representing

13

Fig. 11 Baldassarre Peruzzi Interno of Santo Stefano Rotondo (Florence, U Santarelli 161 r.) (photo: Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi)

Fig. 12 Bernardo della Volpaia (after Bramante ?). Elevation of the Cortile del Belvedere (London, John Soane’s Museum, Codex Coner, fol. 43r. ; photo from Ashby 1904)

Fig. 13 Anonymous early sixteenth century. Copies after Bramante’s projects for the choir and the exterior of St Peters (Florence, U 5A r. ; photo: Gabinette dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi)

COMMENTARIES ON THE DRAWINGS

Note on the Organization of the Entries

The entries follow the numerical sequence employed at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e Stampe at the Uffizi, Florence. Each drawing is identified by its Uffizi number, which is followed by an indication of the subject collection it comes from. The drawings by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and his circle, are all from the architectural collection (“Architettura”) and are thus identified by the letter A. We have used the designation “U” (for Uffizi) only for the first drawing in a sequence or a drawing referred to separately.

While every effort has been made to regularize the forms of transcription used by the authors, some variations are inevitable. The designation “recto and verso” is used in the heading when we have reproduced both recto and verso, having judged that both faces of the sheet merit reproduction. In cases where only a brief text is found on the verso, scholars have been asked to transcribe the text but a reproduction of that face is not provided. In this case, a sheet is referred to as “recto” only. Numbers or other mathematical inscriptions have not been transcribed unless judged of special relevance.

The division of the sequence of drawings by subject, both for the purposes of the entries and for the format of the volumes, is a result of the vast size of this undertaking. In some instances, drawings that contain annotations related

n A Nicholas Adams

eb Enzo Bentivoglio

rb Rita Bertucci

ic Ian Campbell

Acf Anna Cerutti-Fusco

hc D Hans Christoph Dittscheid

se Sabine Eiche

fzb Fabiono T. Fagliari Zeni Buchicchio

clf Christoph Luitpold Frommel

Agg Adriano Ghisetti Giavarina

Ach Ann C. Huppert

cj Christoph Jobst

f - ek Fritz-Eugen Keller †

to subjects ostensibly covered in this volume have had to be reserved for another volume. References to other volumes are indicated by “vol.” and the number of the volume in Roman numerals. By and large, we have tried to follow the principle that the main subject of the sheet determines its location within the corpus. Despite our best intentions this principle of order has not always been respected.

The first lines of each entry give the author, subject, and approximate date of the sheet. Next follows a summary of specifications. Dimensions (height and width) are expressed in millimeters, measured from the bottom left corner ; irregularly cut sheets are described as such. References to “white paper” are assumed, since it was the standard medium used by the Sangallo workshop. Restorations to the sheet may be noted.

In the inscriptions, brackets around three dots indicate an illegible word or phrase. A slash (/) is used to mark a new line. Semicolons indicate discrete words or groups of words.

The authors are identified by their initials at the end of each entry. Authorship divided by a comma (,) indicates that the entries have been combined by the editors.

As the texts written by different authors were written at different times and have different profoundness, they and the bibliography have been updated to varying degrees for the preparation of the publication.

bk Bernd Kulawik

mk Margaret Kunz

ml Maria Losito

ml u Manfred Luchterhandt

gm a Golo Maurer

jn Jens Niebaum

P n P Pier Nicola Pagliara

s P Simon Pepper

hr Hannes Roser

gs Giustina Scaglia †

ms Maximilian Schich

vz Vitale Zanchettin

57

Antiquity and Theory

U 32A recto and verso

An T onio DA S A ng A llo T he Younger Rome, St Peter’s, details of a column, ca. 1535–46 (recto), Sketches of a composite capital, 1535–46 (verso).

Dimensions 287 × 220 mm. Technique Pen and brown ink.

Paper Lightweight, horizontal and vertical folds, perforated in places.

i nscri PT ion , Recto (top half) Di Santo pietro ; lo tutto alto 1 65 ; Tutto 1 65 ; Colla misura del mo dello che l minuto si è per due di quali di 5 per dito ; (lower half, bottom edge) Misurato colle misure […] / modello ch ogni minuto per dito di que 10 di dito ; tutto 3 95 ; Tutta 7 88 ; (lower left) in una te [ ] de / delli [ ]rmo giallo di S.to pietr [ ] ; cinquantamilia cinquanta 71

Verso Di questo capitello me stato mozzo minuti 3 / me stato mo zzo M 3 ; rivedere l’agetto dell’ovolo li membri della cimasa ; la di sotto del capitello 142 / la colonna da pie 1466

The drawing on the recto shows details of the columns, including a sketch of the composite capital (a) ; a study of the volute (b and c) ; and decorations on the base of another column(?) (d ). The latter sketch was executed by turning the sheet 90 degrees ; it may have been made at a different time than the two details for the column in St Peter’s and thus may be unrelated to it. On the lower half of the sheet are sketches of the shaft (e) and the profile of the base ( f ) ; these two drawings were executed by turning the sheet 180 degrees. The notes suggest that the shaft of the column,

of which approximately two thirds was fluted, was to be made of giallo antico marble. However, as evinced by the many calculations on the sheet, Antonio seemed to have been more interested in the relationship between the measurements, so that he could study the proportions of the composite column. The elegant capital is a fine composite example as Giovan Francesco da Sangallo stated in a note on u 1804 A v. (which might be a copy of u 32 A r.), for which there are studies both here and on the verso ; it would appear to have been used as a model for the capitals of the Ducal Palace in Urbino and by Baldassarre Peruzzi for those on the tomb of Pope Hadrian VI in S. Maria dell’Anima. In general, Antonio was not much interested in such richly decorated composite capitals, which, as Pagliara (1992, Ordini, p. 149) has observed, he thought more appropriate for interiors ; he employed similar capitals on fluted pilasters in the Serra Chapel at S. Giacomo degli Spagnoli in Rome.

The sketches on the verso of a composite capital relate to those on the recto of the sheet. Here Antonio drew a good representation of the capital with a measured profile, and next to it a three-quarter view of another profile, in order to study the volutes, which are placed at 45 degrees. The latter scheme was also adopted by Giovan Francesco for u 1804 A , his fair copy of the same capital in St Peter’s that was sketched on the recto of this sheet, u 32 A , by Antonio. However, the survey sketches made on site by Antonio were redrawn in fair copy at the drawing table by his cousin Giovan Francesco. | A gg

b ibliogr AP h Y Ferri (1885) 130, 150–51 ; Bartoli (1914–22) iv: figs 351–52, pl. 210 ; vi : 67 ; CensusIDs 10014116, 10070230.

U 184A recto and

verso

GiovA nni B ATT is TA DA S A ng A llo

Rome, Ancient basins at S. Pietro in Vincoli and at S. Marco (recto). Plan related to projects for Medici tombs at S. Maria Sopra Minerva (verso), prior to 1536.

58

a b c d f e

10 U 284a recto U 284a verso

14 U 606a

recto

15 U 626a recto U 626a verso

35

U 1037a recto U 1037a verso

84 U 1153a recto U 1153a verso

94

U 1168a recto

U 1168a verso

157

U 1369a recto

U 1369a verso

284 codex rootstein hopkins 13 verso

is is the third of four volumes of e Architectural Drawings of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and His Circle, dedicated to drawings of Roman, Etruscan, and Medieval antiquities, and theoretical studies. Antonio da Sangallo’s drawings of antiquity are more numerous than those of any other Renaissance architect before Palladio. ough many of them were taken when preparing new buildings, they are characterized by extraordinary precision and graphical excellence showing the orthogonal triad of plan, section and elevation – but rarely perspectives. Antonio was one of the first to measure orientation with a compass: many of his drawings are therefore still regarded as reliable sources for archaeologists. He was also interested in theory: the column orders and the composition of architectural elements such as doorways and windows play an prominent role in his drawings. For decades Antonio da Sangallo prepared a treatise where he would have reconstructed ancient buildings and compared them with Vitruvius. He kept many of his drawings for this purpose, but his increasing duties, finally as the architect responsible for the entire State of the Church, did not leave him the time to proceed beyond the beginnings. Antonio da Sangallo was no dogmatic Vitruvian but he fought through all of his life for an architecture “all’antica”.