From World Fair to Central Hall of Arts and Sciences

The Prince, the Mover, and the Critics

The Great Exhibition of the Works and Industry of All Nations was the ‘must-see’ event of 1851. From May until mid-October, on a site in Hyde Park, it showcased British manufacturing, with almost equal space given to the achievements of other countries. It attracted over six million paying visitors (many on repeat visits). Personalities as diverse as Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin walked through the immense glass and iron ‘conservatory’ – dubbed the Crystal Palace – designed by the gardener and engineer Joseph Paxton (1803–1865). Queen Victoria (1819–1901) opened the exhibition; her consort Prince Albert (1819–1861) attending in his capacity of president of the Royal Commission which realised it. All walks of life enjoyed a day out there. The royal couple brought their children and visiting royals (their eldest child Victoria (‘Vicky’), aged 15, impressed her husband-to-be Prince Friedrich of Prussia with her precocious knowledge of the exhibits). The middle classes arrived en masse, often by means of the new railways. Cheaper tickets at times gave the working classes access.1 The venture had been controversial initially, but no one could dispute its immense success as essentially the first world trade fair. It made a huge profit of £186,000 (over £27m in 2022).

The first decades of the century had been tumultuous for Britain, as they were throughout Europe, with food shortages, calls for political reform, and frequent turnover of government. However, Britain’s liberal constitution and advanced industrialisation kept it from the revolutions that overwhelmed countries such as France and Prussia. The Reform Act of 1834 had quieted dissent, and a Whig government replaced decades of Tory political dominance. The Reform Act reorganised the often-corrupt voting system and extended the franchise; and so began an era of expansion of the role of government. Royal Commissions and Committees sprang up, enquiring into the state of the country and ushering in legislation in areas such as policing, public health and support of the poor. Eighteenth-century patronage was to be replaced by public works and public accountability.

Britain’s commerce and industry continued to expand, hand-in-hand with its rise as a colonial power. The Great Exhibition arguably marks a turning-point.2 A ‘pageant of domestic peace’,3 its success rested on several factors that would define the remainder of the century – the increase in the executive function of government; a rise in incomes; new financial developments; and a supreme confidence in technological progress. The year 1851 was also, in retrospect, the mid-point of the conspicuously stable union of Victoria and Albert. Through his diligence in both moral and practical spheres, Prince Albertwas to leave the monarchy an important legacy: ‘...a virtuous and domestic Sovereign, interested in

1 On the intentions associated with the 1851 exhibition to ‘break the boundaries of time and space’ as well as to bring different nations and members of society to unity, while maintaining an order and hierarchy assigned by providence, see Bellon, ‘Science at the crystal focus of the world’.

2 Hobhouse, The Crystal Palace.

3 Young, Portrait of an Age, p. 78.

Chapter one

9

docks and railways, hospitals and tenements, self-help and mutual improvement, was impregnable’.4

In realising the Great Exhibition , Prince Albert had joined forces with Henry Cole (1808–1884), a career administrator (public servant, we would say). Both understood that for industry and technology to flourish there must needs be education and innovation in the arts and sciences, directed at a middle-class that had seen its income double between 1815 and 1830, and a working-class whose improved literacy and skills were regarded as the backbone of progress. Cole was a man who ‘got things done’, almost as a force of nature. He was one of the organisers of the exhibitions held by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce – the precursors of the Great Exhibition . Prince Albert had been president of the Society of Arts since 1843 and it was under his aegis that Cole became secretary of the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition .

With the Crystal Palace dismantled, and a large pot of money at its disposal, the Royal Commission purchased an estate of land in South Kensington5 with a view to building a new cultural quarter. This sparsely-developed neighbourhood opposite Hyde Park was as yet poorly connected to the centre of the growing metropolis. Here they would build a diverse range of buildings, including museums and educational institutions, a meeting space for learned societies and a music venue. As president of the Royal Commission, the Prince Consort directed his enthusiasm to the new project, and the area was subsequently nicknamed ‘Albertopolis’.

In August 1853, Albert wrote “some suggestions as to a general plan for the Buildings which it is proposed to erect on the newly purchased ground at Kensington.” At the centre a large symmetrical building would contain a new National Gallery (A in fig. 1.1); to the north would be Colleges of Art and Science (B and C in fig. 1.1); to the south, two parallel buildings (D and E in fig. 1.1) would host “The Museum of Industrial Art, Patented Inventions, Trade Museums etc.”. Peripheral buildings were to cater for official residences, private houses or other institutions. The whole area would be part of a unified concept, both functionally and architectonically, being surrounded by architectural iron railings and entered at the south through a triumphal arch in an “Italian or Palladian style of Architecture, as admitting variety of outline and invention”.

Two of the proposed buildings were to be devoted to functions which eventually became associated with a single building: the Central Hall for the Arts and Sciences, later to be the Royal Albert Hall (fig. 1.1):

The space K, 870 feet long, by a width, East and West, of from 500 to 730 feet has not yet been appropriated and might form the best ground on which to place Buildings for such of the Learned Societies as might express a will to move being the portion of the ground nearest London. …A triangular piece of ground (I on the plan) to the South of the new Brompton Road, and 580 feet long, with a width of nearly 200 feet at its base, might be given to the Academy of Music, for a Music Hall etc., for which the commissioners have already been requested to appropriate a site.6

A number of architects were asked to produce plans for the development of the estate, to include buildings for the arts and the sciences. Sketches by Charles

4 Young, Portrait of an Age, p. 79.

5 Kensington Gore.

6 arce, rc/h /1/ a /3/1.

Fig. 1.1 Prince Albert, ‘Sketch of proposed design for the estate at South Kensington’, 20 August 1853.

This sketch was contained in the Memorandum by Prince Albert regarding buildings at South Kensington. Note the spaces K and I, described by the Prince Consort as apt to host Scientific Societies and a Music Hall respectively. Reproduced with permission of the arCe

10 chapter one

Robert Cockerell (1788–1863), James Pennethorne (1801–1871) and Thomas Leverton Donaldson (1795–1885) show possible solutions, all of which included a hall for music performances and other uses.7

As Prince Albert’s proposal indicated, there was an idea among cultural and government circles to move the National Gallery to South Kensington. This never happened, but relatively soon a new museum was built there: the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria and Albert Museum, or ‘V&A’). Founded in 1852, a direct legacy of the Great Exhibition whose collections it housed, it opened in its current location on Cromwell Road in 1857. Other parts of the project took much longer to materialise, particularly the plan for the music hall and headquarters for learned societies. Around 1860, consensus emerged in respect of locating it at the north end of the Commission’s grounds, adjacent to the conservatory in the newly-created Gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society and opposite Hyde Park. However, its form, size and exact purpose were still unclear.

7 Sheppard, ed., Survey of London, pp. 74–96.

8 A sketch by Cole for a ‘Chorus Hall’ shows a concert Hall with straight sides and rounded ends, enclosed in a rectangular building, see Binney, ‘The Origins of the Albert Hall’.

9 Herrmann, Gottfried Semper im Exil.

10 Burton, ‘Art and Science applied to Industry’.

11 arce, rc/h /1/21/45; arce, rc/h /1/21/46.

12 Mallgrave, Gottfried Semper; for the Dresden theatre design, see, in particular, pp. 117–29. The building was destroyed by fire in 1869 and the second opera house by Semper erected 1871–78.

12 chapter one

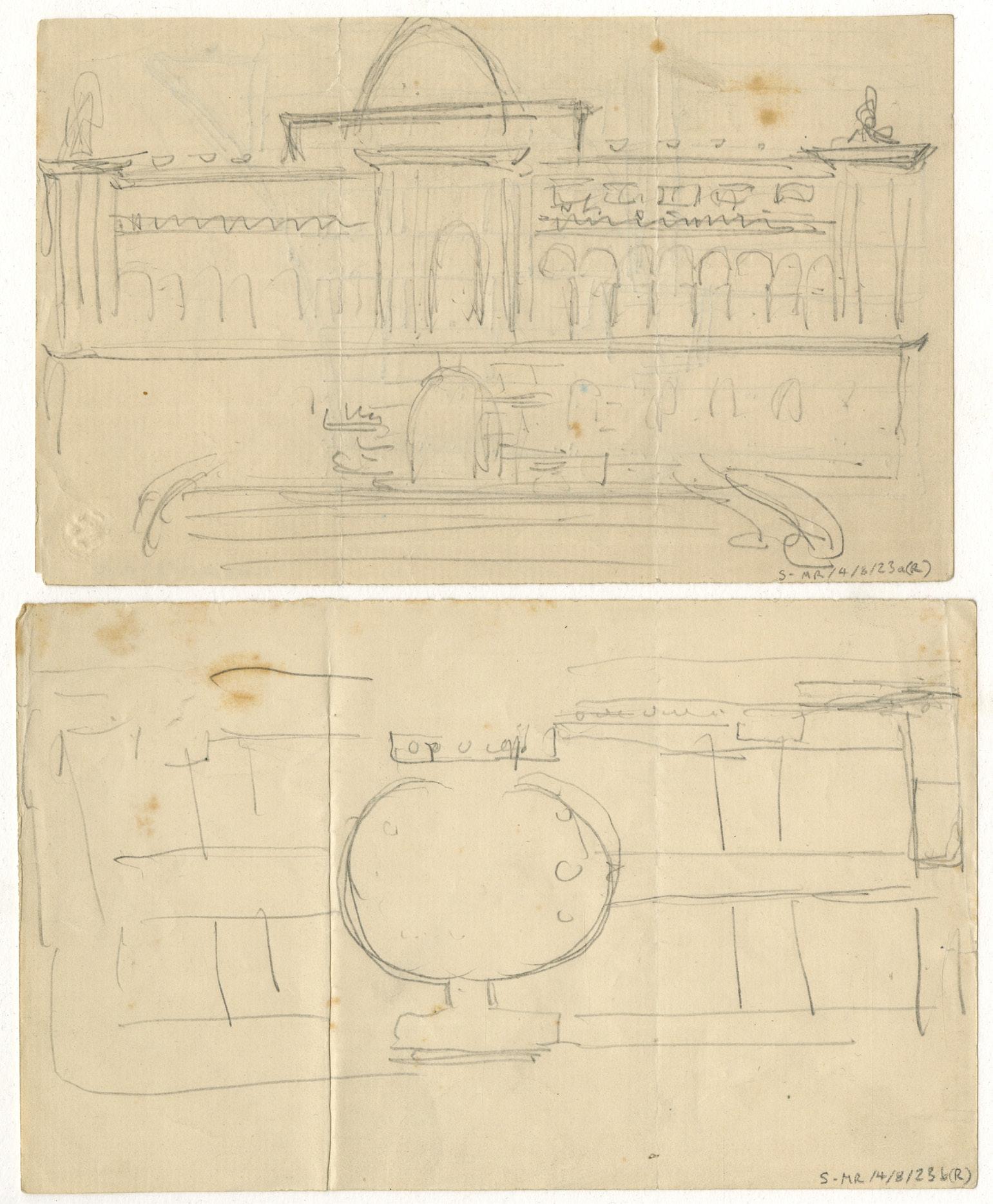

Fig. 1.2 Henry Cole, ‘Sketches of early ideas for a Hall of Science and Art’, 1860. RIBA collections.

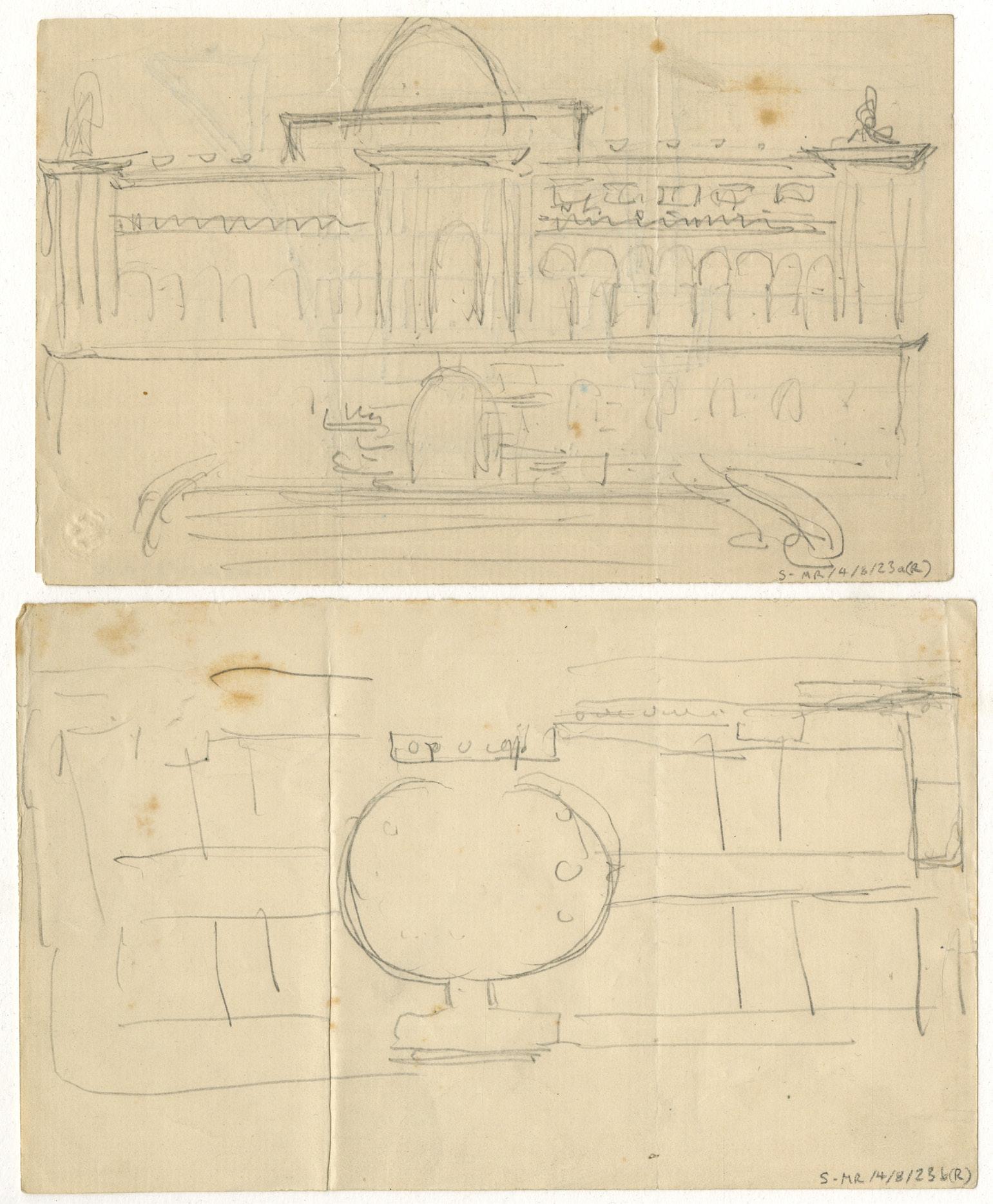

A sketch by Cole (fig. 1.2), possibly from 1860, gives an idea of the kind of building under discussion.8 It is echoed by an even vaguer sketch, which may have been by the Prince Consort himself, showing a similar building mooted to be attached to the Royal Horticultural Gardens’ Conservatory (fig. 1.3). The Royal Horticultural Society leased the land for the gardens from the Commissioners for the 1851 Exhibition: an arrangement very likely facilitated by Prince Albert who was president of both the Royal Horticultural Society and the Commission.

At one point, Prince Albert asked the German architect Gottfried Semper (1803–1879) to produce a design for a hall. Semper had escaped to London after the Dresden uprising of 1849 and been appointed clerk in the Science and Art Department. 9 He was well-suited to the task, having been involved in various capacities in the planning of cultural fora in Hamburg, Zurich (unrealised), Vienna (partially realised) and Dresden.10 Unfortunately, the drawings and cardboard models that Semper produced for South Kensington, once in the possession of the Prince Consort, have been lost.11 It is striking how Semper ’s most famous theatre design, the first Royal Court Theatre in Dresden (1838–41), has elements in common with the Albert Hall’s final design (fig. 1.4).12

1.3 ‘Plan of the Kensington Gore Estate of Her Majesty’s Commissioners for the Exhibition of 1851’, with annotations by Prince Albert.

It shows the outline of a prospective building adjacent to the Royal Horticultural Gardens and annotations, probably by Prince Albert. Reproduced with permission of the arCe

13 From World Fair to Central Hall of Arts and Sciences

Fig.

Fig. 1.4 Gottfried Semper's opera theatre in Dresden, which, in this view, strongly resembles the Royal Albert Hall's architectural composition. Friedrich and Ottilie Brockmann, c. 1860.

Reproduced with permission of the Historic Archive of the Sächsische Staatstheater, Dresden.

Fig. 1.5 Semper’s opera theatre in Dresden, which featured semicircular ends resembling the Royal Albert Hall, but straight sides, similar to some early designs by Fowke for the Royal Albert Hall. Unknown Photographer.

Reproduced with permission of the Historic Archive of the Sächsische Staatstheater, Dresden.

14 chapter one

The Royal Court Theatre in Dresden was praised internationally and considered one of the most beautiful and functional modern theatres in Europe. Despite the similarities between the curves of this building and the Albert Hall, there are significant differences. Semper ’s design featured straight sides and a central plan (fig. 1.5) that was characteristic of many German theatres in the first half of the 19th century. Precedents include the State Theatre in Mainz (1829–33), designed by Georg Moller (1784–1852) and the Victoria Theatre in Berlin (1858–59), by the architect Anton Eduard Titz (1820–90).13

Prince Albert died prematurely, in 1861, leaving Queen Victoria distraught and his projects incomplete. From public funds and the Queen’s patronage, a monument was to be erected to him in Hyde Park. The following year, the Committee for the Prince Consort’s Memorial asked a number of architects for their views on a proposal to link this monument with the late prince’s vision of a ‘Central Hall’. The architects’ response, in a letter to Charles Grey (1804–1870), private secretary to the Queen (and previously to Prince Albert), was equivocal, and reflects the vagueness that still characterised the Hall:

Having thus given our views of the site and character of the Prince Consort memorial, we approach with much more diffidence the consideration of the question of some building to be erected, with a view to general usefulness, in order to carry into effect to a certain extent the frequently expressed wishes of the Prince, and particularly to realise his views as stated in his address at the opening of the Horticultural Gardens.14

The Prince’s wishes had been to foster the arts and sciences. The letter goes on to say:

It appears to us that, by the generosity of the nation, apart from the learned societies, science and art are provided for in the British Museum, the Museum in Jermyn-Street, and the Schools at South Kensington. What seems to be wanted is some spacious Hall and its necessary adjuncts, as a place for general art meetings; or for such assemblies as are about to take place in London in connexion with social science and its kindred pursuits.15

‘Social sciences’ are here to be understood as public health and social reform, including the question of female education.16 While music was not central to the architects’ recommendations, they envisaged a multi-purpose hall for both administration and entertainment that would include art and music. London did not have “an object like the great halls of Liverpool, Leeds, and Manchester”, and the architects lamented that “the great meetings of the National Society for the Promotion of Social Science” had to take place in “most unfit places”, such as the Egyptian Hall of the Mansion House which did not offer enough space, or Exeter Hall which had significant religious (non-conformist) connotations.17

The ‘great halls of Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester’ are representative of the rise of commercial and industrial towns across England in the mid-19th century, and the way in which civic pride found expression in architectural projects. In

13 These theatres were known to the British architectural profession. They were, for example, listed by the architect Edward Godwin (1833–1886) in his long article on theatres published in 1868 in instalments in The Building News He mentions them as successful examples of theatres with a circular plan. Godwin, ‘Theatres’ (part 1).

14 Letter to Charles Grey, the Queen’s private Secretary, signed on 5th June 1862 by William Tite (1798–1873), Sidney Smirke (1797–1877), George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878), James Pennethorne (1801–1871), Thomas Leverton Donaldson (1795–1885), Philip S. Hardwick (1792–1870) and Digby Wtyatt (1820–1877), arce, rc/75/2, pp. 42–43.

15 arce, rc/75/2, pp. 42–43.

16 As is suggested by the reference made in the report’s subsequent paragraph to the ‘National Society for the Promotion of Social Science’. On the aims and actions of the Social Science Association, see Goldman, Science, Reform, and Politics.

17 arce, rc/75/2, pp. 42–43.

15 From World Fair to Central Hall of Arts and Sciences

1836, Liverpool produced plans for a hall to host music festivals, meetings, dinners and concerts, to which was later added the administration of justice. St George’s Hall began construction in 1841 and was inaugurated in 1854. The Great or ‘Concert’ Hall at its centre was equipped with a large organ for recitals, as would be the case with the Royal Albert Hall. The Liverpool building also contains a small Concert Room of elliptical shape, like its London counterpart.18

Leeds Town Hall, planned from 1850 and built between 1853 and 1858, according to designs by Cuthbert Brodrick (1821–1905), also provided for a series of functions: a courtroom, a police station, municipal departments, and a venue for concerts and civic events. The Great Hall (later renamed Victoria Hall), constituted the principal performance space: it too, was fitted out with a great organ.

Manchester had built a town hall in the 1820s to accommodate offices and assembly rooms. By the 1860s, the city was on its way to erecting a much more ambitious building, with the explicit aim of surpassing the recent structures in Liverpool and Leeds. Planning began in 1863 and building work started in 1868, following the design by Alfred Waterhouse (1830–1905). The Town Hall was inaugurated in 1877, six years after the Royal Albert Hall. For several years, the two projects were discussed simultaneously by the press and in architectural circles; but whereas the design, purpose and size of Manchester’s Town Hall soon became apparent, details of the Albert Hall remained nebulous.

These ambitious civic buildings were manifestations of a rising middle class that was increasingly interested in ‘educated’ entertainment and artistic expression. Since the late 18th century, regional towns had been active in promoting the advancement of science in its various branches, setting up local societies and regularly hosting lecture series for different audiences – out-doing London, where scientific societies, though well-established, were relatively stagnant.19 From the 1830s onwards, this lacuna was filled: a number of national organisations devoted to science, technology and the development of associated professions were founded in the capital and began a lively cultural and scientific dialogue with the provinces that included hosting annual conferences in urban venues around the country.20 For example, 1831 saw the birth of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, which grew out of a widespread frustration with the work performed by the Royal Society 21These institutions, and numerous theatres and public spaces notwithstanding, the capital still lacked the hallmark of the modern metropolis: a vast, multi-functional hall.22

Many of the London venues that provided for the arts and sciences in ways similar to those proposed for the Central Hall, were struggling financially; for example, the Crystal Palace at Sydenham and the Alexandra Palace. Balancing ‘showbiz’, edifying entertainment, educational initiatives and scientific pursuit was proving tricky; and some of the commentators on the new venue questioned what kind of public it would attract, or whether its programme could successfully be scientific, educational and innovative.23

Nevertheless, in 1863, the Prince Consort Memorial Committee proceeded to commission designs for both the personal monument to Albert and elevations of a ‘Memorial Hall’. The decision not to hold an architectural competition was significant. Competitions had been a mainstay of significant building projects throughout the 18th century and became near ubiquitous in the 19th century

18 Knowles, St George’s Hall, Liverpool See also Bassin, Architectural Competitions, pp. 47–53.

19 Hunt, Building Jerusalem Industrial and commercial elites from the north of England invested in cultural, administrative and recreational infrastructures as part of an ongoing ‘competition’ with the south of the country and the capital in particular.

20 On the role of provincial towns in initiating scientific societies and hosting congresses see Miskell, Meeting Places, in particular pp. 1–10.

21 Foote, ‘The Place of Science in the British Reform Movement 1830–50’. The Royal Society, the fellowship of eminent scientists founded in the 17th century, had latterly become more of a club than a power-house for knowledge

22 As explained in chapter three, the Crystal Palace at Sydenham was in some ways a comparable venue, but it was a completely private and commercial enterprise, rather than one born out of a civic initiative, and it was positioned outside of town

23 See chapter three.

16 chapter one

(perhaps, as Joan Bassin has suggested, due to a notion of ‘competition’ as a solution in all aspects of life, in which the best individual would naturally rise to the top: Herbert Spencer’s ‘Social Darwinism’).24 A competition was seen as the answer to a sharp rise in the instances of collective clients, as opposed to individual patrons, who could not otherwise reach agreement between themselves25 and who were often ill-equipped to make judgements in architectural matters; moreover, committees were prone to external influences, including corruption. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, even the Office of Works, devoted to the oversight of the Crown’s building projects, had at times been led by unqualified individuals and engulfed in scandals of incompetence and financial improprieties.26

Competitions served another purpose. Without a professional training system for architects, it was a difficult task to choose who to put in charge of a building project: the badge of honour of winning a competition implied at least some degree of proficiency. During the course of the 19th century, however, it became clear that the competition system was flawed. It was exposed to corruption and was unregulated, often favouring unrealistic but impressive proposals by unscrupulous architects and builders. A training system for architects was gradually developing. Formal professional institutions were founded, such as the Institute of British Architects (1834) and the Architectural Association (1847), and the specialised architectural press was born.27 Following this, attempts were made to regulate the competitive arena – in 1838 by the newly-formed Institute of British Architects, in 1850 by the Architectural Association and, again, in 1872 by the now Royal Institute of British Architects which published the “General Rules for the Conduct of Architectural Competitions”.28

Strict rules were introduced that prescribed the kind of material to be submitted, a limit to budgets, an exact description of what was expected etc., and the employment of professional, impartial judges. The latter would ensure that the rules were being followed and act as a ‘quality control’, while leaving the patrons a good degree of scope to choose the winning design (or architect). However, this solution was not as easy as it might seem. The idea of relying on impartial ‘experts’ was a contested one in the 19th century. The term ‘expert’ – mainly coined by the press in the context of witnesses called to arbitrate in various tribunal disputes – had, in fact, negative connotations. How could two ‘experts’ testify differently on the same issue, depending on which side they were ‘aligned’ to? Was objectivity at all possible? Given that expert witnesses were remunerated, was this not a blatant conflict of interests? More generally, could an ‘expert’s’ opinion not be swayed?29A partial solution, in Victorians’ eyes, was to engage ‘authorities’ rather than ‘experts’. The former, as representatives of an established institution with no direct financial interest in the matter at hand, could be expected to display a certain degree of impartiality. The distinction, however, was not always clear and, in a close-knit network characterised by ‘young’ institutions, faith in the authority’s trustworthiness was not always strong.

Given this context, it is unsurprising that the Commission for the proposed Hall of Arts and Sciences was cautious about calling an open competition. The Prince Consort himself had apparently not been in favour of such a route.30 In 1862, the Commission decided to invite proposals from a small number of cherrypicked architects, to be paid a sum of £100 each.31 We can build a general picture of

24 See Smith, An Inquiry into the nature and causes of the Wealth of Nations Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population as it affects the future improvement of Society ; Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection On the idea of social evolution in Britain in the 19th c. and its roots, see Goldman, ‘Victorian Social Science: From Singular to Plural’, in particular pp. 106–110.

25 Jenkins, Architect and Patron p. 88.

26 Crook, Port and Colvin, History of the King’s Works

27 Hvattum and Hultzsch ed., The Printed and the Built: Architecture. Hultzsch, ‘Sharing knowledge, promoting the built’

28 Bassin, Architectural competitions, pp. 1–18.

29 Gooday, ‘Liars, Experts and Authorities’.

30 arce, rc/h /1/21/64.

31 The invited architects were Charles Barry Jr (1823–1900), Edward Middleton Barry (1830–1880), Thomas Leverton Donaldson, Philip Charles Hardwick (1822–1892), James Pennethorne, Matthew Digby Wyatt (1820–1877) and George Gilbert Scott. See Sheppard, ed., Survey of London, pp. 177–95.

32 Anonymous, ‘The Competition Designs’, specifically p. 386, discusses Wyatt’s and Hardwick’s designs. Hardwick had suggested, among some possible alternative designs, a ‘Medieval Fountain of National Science and a Classical Fountain of National Art’, part of the entry is ‘The Albert Institute, Piazza and surrounding buildings in a classical style’.

17 From

Arts

Sciences

World Fair to Central Hall of

and

many of these designs through descriptions in the press, but unfortunately only a few drawings survive.32 The most interesting proposal for our purposes is by Gilbert Scott (1811–1878) since he was initially chosen to design the Albert Hall; but instead he designed the Albert Memorial G. Scott’s main design was Byzantine, “a completion of the idea of St Sophia”, one of the most renowned dome structures in the history of architecture.33 He also suggested a variation characterised by pointed rather than round arches. Moreover, he developed two completely different concepts: a Byzantine and a “Gothic”.34 The surviving drawings are of a “detached building, between the Hall itself & the Park, that Building which would be alone seen, being occupied by Offices,

Reproduced with permission of the ARCE

18 chapter one

Fig. 1.6 ‘Plans for a Great Hall to be built in the North of the Commissioner’s estate in South Kensington’, enclosed in a letter from Henry Cole to General Grey, dated 20 August 1864.

Reproduced with permission of

Chambers etc.” (fig. 1.4). According to G. Scott, this was a preliminary design “for the purpose of furthering the project during its embryo stage”.35 A prospectus of 1864 for the ‘Albert Memorial Hall’ states that “the exterior elevation of the Building facing the personal memorial, will be designed by G. Gilbert Scott esq., R.A., and its interior arrangements by Captain Fowke, R.E.” By August 1864, the Royal Commission was considering a similar arrangement36 whereby a front building containing offices would separate the main Hall from Hyde Park. Unlike G. Scott ’s design, this plan did not envisage a prominent South front, the offices being linked to the Hall through some kind of connecting bridge; while the Hall itself, on the South, would be attached to the Royal Horticultural Gardens’ Conservatory. A great organ was already considered, in line with that of similar halls in the period (fig. 1.6).

Towards the end of 1864, Cole and the Royal Engineer, Captain Francis Fowke (1823–1865) visited sites such as the Roman amphitheatres of Nimes and Arles in the south of France. Earlier in the year, Cole had suggested a Colosseum-like design for the new building to Fowke, G. Scott and Richard Redgrave (1804–1888), an artist and administrator heavily involved with Cole in the Science and Art Department and in the reform of art education.37 Inspired now by the sight of these ancient buildings, Cole dropped G. Scott’s suggestion of an “early Gothic treatment, with a tinge of Byzantine” and asked Fowke to “set to work upon further plans, and a model” based on their travels.38 This stage of the design is documented by Fowkes’ model of the Hall, shown in fig. 1.7. The building’s exterior was still undetermined, possibly because the idea of a separate building forming the front was still being discussed. The interior shown in the model closely resembles an unrealised design that Fowke had previously proposed for the building of the 1862 International Exhibition (fig. 1.8).39

33 Generally known as hagia Sophia, see chapter eleven

34 Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, p. 279.

35 arce, rc/h /1/21/97. In subsequent years, when the project had taken a different trajectory, the architect asked to have his designs back

36 arce, rc/h /1/20/37.

37 Indeed, Cole would call the Albert Hall ‘The new covered coliseum’ (Cole, Report on TerraCotta, p. 9).

38 Cole, Fifty Years of Public Work, i , p. 361. Among the classical examples the amphitheatre in Pula, Istria, was also mentioned; see Sheppard, ed., Survey of London, pp. 177–95.

39 Dishon, ‘South Kensington’s Forgotten Palace’. The shape of the auditorium, with straight sides and curved ends, also reminds of Cole’s design for a ‘Chorus Hall’, illustrated in Binney , ‘The Origins of the Albert Hall’.

19 From World Fair to Central Hall of Arts and Sciences

Fig. 1.7 ‘Model of the Hall’, according to a design by Francis Fowke, presented to Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales by Sir Henry Cole and Richard Redgrave at Osbourne House on 30 January 1865.

the V&A.

20 chapter one

Fig. 1.8 ‘Interior view of the never-built 1862 Exhibition building’, by Francis Fowke. Reproduced with permission of the V&A.

On 30 January 1865, Cole and Redgrave went to Osborne House on the Isle of Wight to present the model to the Queen and Edward (‘Bertie’), Prince of Wales (1841–1911), in a bid for their support for the new Hall. Cole gave the royals “a ground plan showing the proposed site of the Hall, also a drawing prepared by Mr. Gilbert Scott R.A. of the entrance building to the hall proposed to front the memorial to the Prince Consort, which he had designed”.40 The Queen and her son agreed to back the project, and in July 1865 the Prince of Wales presided over a meeting at Marlborough House at which was formed the ‘Provisional Committee for the Construction of a Great Central Hall’.

Cole’s diary records many discussions with Fowke about the shape of the Hall, and with trusted members of his circle about the feasibility of the architectural proposals. For example, on 25 February 1865, “Fowke [was] wanting to avoid the design of Colosseum for the Hall & proposed some heavy structure.”41 On 27 February 1865, Fowke proposed a “Venetian treatment”.42 On 28 February 1865, Cole reports that “Kelk did not like Fowke’s proposed sketch for outside”.43 Fowke went back to the drawing-board, coming up with two new solutions: “a Colosseum & (a) Bramante”.44 John Kelk (1816–1886) was a well-known public-works contractor who was tasked with the construction of the Albert Memorial (for which he received a knighthood). He was also heavily involved in the early construction phase of the South Kensington Museum and the 1862 International Exhibition building. A member of the Institution of Civil Engineers since 1861, Kelk was an influential figure in his profession and in politics, representing the Conservatives in Parliament from 1865–68.

On 19 and 20 March 1865, Cole showed Fowke’s latest designs for the Hall to Kelk and to Robert Lowe, Viscount Sherbrooke (1811–1892), a member of the Provisional Committee for the Hall who also sat on its Financial Committee. Lowe was a prominent politician and would become Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1868. Cole evidently consulted people who were as much ‘influencers’ as technical and artistic advisors, not all of whom shared his vision for the building. Lowe, for example, appears not to have liked Fowke’s designs – instead, suggesting “a Sheldonian Theatre for 4000 persons”;45 ie. a much smaller building that would host more narrowly-defined scientific gatherings, rather than a vast multi-purpose venue.

In July 1865, a second prospectus for the Hall described the building as “a spacious amphitheatre consisting of an arena, an amphitheatre, and two tiers of private boxes.” The Hall was expected to have a variety of uses, including music performances on a grand scale and exhibiting pictures and sculpture. Exhibitions would be held above the boxes where there would be “a corridor lightened from the top affording space for a spacious promenade”.46 Fowke died in December 1865, leaving the model of the interior mentioned above (fig. 1.7) and some drawings of the exterior. Additionally, a further model, drawings and sketches had been prepared by his assistant John Liddle, partially under Fowke’s supervision.47 However, drawings and models were “so little in accord, indeed, that they cannot be said even to belong to the same building”.48 This sounds surprising: but it appears that Fowke, at the time of his death, had not considered plans for the exterior of the Hall to be settled.49

Cole and Grey were inclined to think that Fowke’s draughtsmen might complete the design, and commissioned more models of the building in wood

40 raha, rah/1/2/1/1, p. 6.

41 cd, 25 February 1865.

42 cd, 27 February 1865

43 cd, 28 February 1865

44 cd, 1 March 1865. See also cd, 3 March 1865 (‘Discussing details of Hall with Fowke’). Possibly ‘Bramante’ refers to a design that took inspiration from the famous ‘tempietto’, a circular building attached to the Church of S. Pietro in Montorio in Rome, built in the early 1500s to a design by Donato Bramante.

45 cd, 6 April 1865.

46 rc/h /1/21/21.

47 Liddle, ‘The Architect’

48 Scott, ‘On the Construction’.

49 ‘I have had a good deal of conversations with Cole lately on the subject of Fowke’s design for the Hall. As for the interior arrangements he tells me Fowke considered them as, in essentials, definitively settled. Not so, however, as to the exterior’. arce, rc/h /1/21/45.

21 From

Arts

Sciences

World Fair to Central Hall of

and

according to his plans, particularly to indicate the stair arrangements and seating, to see how far the existing design could be taken.50 But it became apparent that the arrangements of the exterior portion of the Hall “would not fulfil satisfactorily all the conditions which Captain Fowke contemplated.” 51 A successor to Fowke was needed who could develop his design and direct the construction. Grey suggested Semper, citing the drawings of a hall he had produced for Prince Albert many years before, as well as his acclaimed Royal Court Theatre in Dresden . 52 However, it was declared that commissioning a German to construct a national monument “would be a shun on the whole body of British architects”, and the idea was dropped.53 As the Committee was not seeking a new design, an architectural competition was unnecessary (which, in any case, was little approved of at South Kensington, as we have seen).54 Cole made a ‘half-way house’ proposal to show a group of architects a model of the design so far, and invite them to suggest improvements:

What do you think of a competition for the outside of the hall on this plan?

To prepare the Model as far as may be done, consistently with what we believe to be Fowke’s wishes and with the necessities of the case in respect of dimensions, approaches etc.

To let the architects see it and then to give a premium to those who can suggest the best practical improvements. Whether little or much resulted, the Provisional Committee would at least know what was thought of the outside.55

Cole’s proposal was not taken up but the model was produced, according to a letter to Cole from the Earl of Derby (1799–1869) in April 1866. The letter referred to the

50 arce, rc/h /1/21/54. See also arce, rc/h /1/21/44: ‘We are now having models made in wood to show the stair arrangements and the seats [?] from the Hall, and probably when next you are able to come they will be made for you’

51 rah/1/2/1/8 pp. 40–41.

52 arce, rc/h /1/21/45. See also Herbert Fisher to General Grey, arce, rc/h /1/21/48. Herbert William Fisher (1826–1903) was a British historian who served as the Prince of Wales’ English tutor; see. See also Henry Cole to General Grey, arce, rc/h /1/21/46.

53 Lord Derby to the Prince of Wales, arce, rc/h /1/21/49. Lord Derby was a member of the Provisional Committee for the Albert Hall and had been a member of the Commission for the 1851 Great Exhibition from 1850. In April 1864 he was elected President of the Commission, succeeding the Prince Consort, and undertook the role until his death in 1869. Lord Derby was the first British statesman to become prime minister three times. He led Conservative governments in 1852, 1858 and 1866.

54 arce, rc/h /1/21/45.

55 arce, rc/h /1/21/64.

Fig. 1.9 Portrait of Henry Young Darracott Scott (1822–1883), published in The Illustrated London News in 1883.

22 chapter one

need to decide whether to appoint an architect;56 and also recommended meeting ‘in the reading room of the Horticultural Society where the Plaster Model of the Hall can be put up & Fowke’s drawings and designs laid out for consideration’. Meanwhile, another Royal Engineer, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Young Darracott Scott (1822–1883, fig. 1.9), had been working on plans for the Hall since Fowke’s death. Cole considered him to be a good option to keep the design in-house.57 Indeed, on 14 December, the Science and Art Department ’s board suggested that H. Scott should take over from Fowke as director of new permanent buildings. H. Scott had been involved in the construction of the South Kensington Museum and the Royal Horticultural Gardens, and was secretary of the Provisional Committee.

The relative infancy of the Albert Hall project required H. Scott to make considerable alterations to Fowke’s design, which are partially documented in the minutes of the meetings of the Provisional Committee and its sub-committees. In response to his modifications, on 30 April 1866 the Provisional Committee asked him to prepare drawings, a model, and a report describing the revised project. A week later, these were considered and approved58 and H. Scott was appointed to succeed Fowke.

56 arce, rc/h /1/21/65. It suggests that the provisional committee meets without further delay to decide on the prospectus and whether or not to hire an architect. See also raha, rah/1/2/1/9 and rah/1/2/1/10, pp. 38–44.

57 cd, 7 December 1865.

58 rah/1/2/1/8, pp. 40–41.

23

Sciences

From World Fair to Central Hall of Arts and

Albert, Prince Consort 9, 17

Architectural Association 17 B

Berlin

Victoria Theatre 15

British Association for the Advancement of Science 16

Broderick, Cuthbert 16

C

Cockerell, Charles Robert 12

Cole, Henry 10, 13, 19, 21

D

Darwin, Charles 9

Derby, Earl of 22

Dickens, Charles 9

Donaldson, Thomas Leverton 12

Dresden

Royal Court Theatre 13, 15, 22

E

Edward, Prince of Wales 21

F

Fowke, Francis 19, 23

G

Grey, Charles 15, 21, 22

I

Institution of Civil Engineers 21

Isle of Wight

Osborne House 21 K

Kelk, John 21

L

Leeds

Town Hall 16

Liverpool

St George’s Hall 16

London

Albert Memorial 15, 16, 18, 21

Alexandra Palace 16

British Museum 15

Crystal Palace 9

Crystal Palace, Sydenham 16

Egyptian Hall, Mansion House 15

Exeter Hall 15

Great Exhibition, 1851 9, 10, 12

Marlborough House 21

National Gallery 12

Royal Horticultural Society, gardens 12, 13

V&A (previously South Kensington Museum) 12, 23 M

Mainz

State Theatre 15

Manchester

Town Hall 16

Moller, Georg 15

National Society for the Promotion of Social Science 15

Paxton, Joseph 9

Pennethorne, James 12

Redgrave, Richard 19, 21

Rome

Colosseum 19, 21

Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 9, 10, 19

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA ) 17

Royal Society 16

Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce 10 S

Science and Art Department 13, 19, 23

Scott, Gilbert 18, 19, 21

Semper, Gottfried 13, 15, 22

Titz, Anton Eduard 15

Victoria, Queen 9, 15, 21

Waterhouse, Alfred 16

24 Index

A

N

P

R

T

V

W

‘Model of the Hall’. Detail of fig. 1.7.

‘Model of the Hall’. Detail of fig. 1.7.