RRESEARCH

AT BERKHAMSTED

Berkhamsted aims to develop students who do more than simply pass public exams with exceptional results. The ideal Berkhamsted alumnus is better-rounded than that. They are someone who flourishes – in Higher Education, in employment, and in society more broadly (for more on student flourishing, see Kristjansson, 2019; Hampson et al., 2022; McConville et al., 2021; Swaner and Wolfe, 2021). They don’t simply ‘earn a living’ but ‘enjoy lives worth living’, because they forge happiness and life satisfaction, mental and physical health, and a sense of meaning and purpose in life, character and virtue, and strong social relationships (which are the domains The Human Flourishing Program at Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science uses to measure the extent of ‘human flourishing’).

A key part of the school’s nurturing process is the focus on the education of student character: at Berkhamsted, the development of character is as important as the content in lessons and extra-curricular activities. Such ‘Character Education’ is celebrated in this fourth issue of Research at Berkhamsted. It offers insight into some of the evidence, research, and thinking underpinning our emphasis on this key facet of education in 2022, and helps explain why it is so important in developing flourishing, remarkable people.

We open with Edward Cain’s detailed and lively literature review, ‘What can your subject contribute?’, which helpfully – and thoroughly – serves to contextualise the character-focused pieces that follow. The first of these is Richard Backhouse’s ‘Character – Universal or Just Vital’, with contributions from Mark Turner and John Browne, whose Janus-faced approach outlines the tradition and modernity of character education, as well as, ultimately, its value in three very different contexts. Ben Kerr-Shaw’s ‘What makes a “remarkable” person?’ builds on Backhouse’s, succeeding in crystalizing the potentially nebulous idea of an individual being ‘remarkable’, with an investigation into the character traits that parents, pupils, and colleagues look for in a ‘remarkable person’. Next, Aidan Thompson, PhD student and Director of Strategy and Integration at the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtue at the University of Birmingham, argues in ‘Educating character through song lyrics’, that popular song lyrics are as morally useful for the ‘betterment’ of the individual as some of the greatest works of Literature. Former Head Girl, Daisy Holbrook, then reflects on how her character was developed throughout 15 years as a student at Berkhamsted in ‘Character Education at Berkhamsted’. Duncan Hardy’s contribution is also Berkhamsted-focused: in ‘Leadership at Berkhamsted and “the advantage it offers”’, he outlines his initiative of embedding a culture of leadership throughout the school, which has been crucial in the formation of students’ character. An alternative view is provided by Dr. Lee Jerome, whose article, ‘Problems with Character Education’, finishes this section of the issue, critiquing the efficacy of certain actualisations of character education, providing food for thought about how best to deliver it.

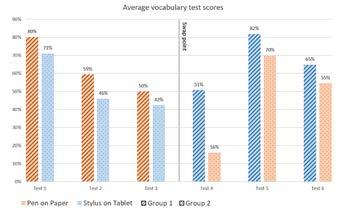

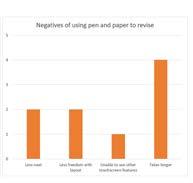

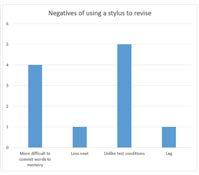

The issue then broadens out with Alastair Harrison’s, ‘What is the purpose of the Key Stage 3 curriculum?’, which interrogates whether KS3 in English should be GCSE preparation or subject enrichment. Following this, Hannah Galbraith’s ‘Pen-on-paper versus stylus-on-tablet’ investigates whether some of the cutting-edge technology used for learning and teaching during lockdown still has a place in the Mandarin classroom. Similarly, Anna Dickson’s article asks how ‘digital technology [can] be used to support effective assessment and feedback without increasing teacher workload’? The post-pandemic classroom is also central to Sophie Brand’s work in ‘Reflections from a Covid Classroom’. It draws on the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari to explore a ‘teaching without organs’ approach. In ‘Improving children’s vocabulary: does it progress their writing?’, Emily Bowers then explores her efforts to improve Year 2 pupils’ writing by exposing them to more contextual vocabulary, which could have been seen as lacking during lockdowns throughout the pandemic. George Picker from Downe House School follows this in ‘Assessment: a meaningful process?’, calling for ways to make assessment more meaningful in Music and Isla Phillips from Sevenoaks School examines how the ‘Harkness’ discussion method can enhance the teaching of Critical Thinking.

The issue is brought to a close with a precis of Adeeb Ali’s A* ‘Extended Project Qualification’ essay which evaluates antitrust law in the regulation of ‘Big Tech’ in the USA before book reviews by Nick Cale and Lucie Michell.

Depending on why you are reading, I hope the inspiring work on display motivates you to tweak your practice or pursue a line of research; or demonstrates a small sample of some of the research-informed thinking that contributes to the development of 'remarkable' people at Berkhamsted.

Once again, thank you wholeheartedly to all contributors, to Hannah Butland, Deputy Head: Teaching, Learning, and Innovation, for guidance and proof reading, and to the exceptionally creative Jen Hallesy for the graphic design.

Dr. James Cutler (Head of Research and Teacher of English)

Character Education: What Can Your Subject Contribute? by Edward Cain 3 - 7

Character – Universal or Just Vital? by Richard Backhouse 8 - 11

‘What Makes a ‘Remarkable Person?’ - a Report Into Current Attitudes and Beliefs Towards Character Education at Berkhamsted Schools Group by Ben Kerr-Shaw 12 - 16

Educating Character Through Song Lyrics by Aidan Thompson 17 - 19 Character Education at Berkhamsted by Daisy Holbrook 20 - 22

Leadership at Berkhamsted and ‘The Advantage it Offers’ by Duncan Hardy 23 - 26

Problems with Character Education by Dr. Lee Jerome 27 - 30

Preparation for GCSE or an Opportunity For Subject Enrichment - What is the Purpose of the Key Stage 3 Curriculum? by Alastair Harrison 31 - 34

Pen-on-paper Versus Stylus-on-Tablet: An Investigation into the Effect of Surface Texture on Vocabulary Learning in Chinese by Hannah Galbraith 35 - 39

How can Digital Technology be Used to Support Effective Assessment and Feedback Without Increasing Teacher Workload? by Anna Dickson 40 - 49

Teaching Without Organs: Reflections From a Covid Classroom Using Deleuze & Guattari by Sophie Brand 50 - 56

Improving Children’s Vocabulary: Does it Progress Their Writing? by Emily Bowers 57 - 58

Experimenting With the Harkness Discussion Method by Isla Phillips 59 - 60

Assessment: A meaningful Process? by George Picker 61

How Successful has Antitrust Law Been in Regulating Big Tech in the USA? by Adeeb Ali 62 - 65

What Does This Look Like in the Classroom? Bridging the Gap Between Research and Practice. by Nick Cale 66

The Boy Question: How to Teach Boys to Succeed in School. by Lucie Michell 67 - 68 Works Cited 69 - 74

If you could choose a new name for our noble profession, would you choose ‘teaching’? Given everything else that we do, it seems too limited. In my first year of teaching in a state boarding school, I quickly discovered that despite the academic job description my role actually required pastoral advice, parenting, sports coaching, chapel talks, CCF and extra-curricular clubs for leadership. Perhaps it was the same for you because, school to school, expectations seem similar. As teachers we are implicitly asked to help develop our pupils as whole persons. ‘Whole person, whole point’ as Rugby School neatly puts it.

As a Philosophy graduate, I self-importantly rationalise these activities with reference to Aristotle: we contribute to pupil flourishing. In education literature this is theorised under the umbrella term ‘character education’ (Kristjánsson, 2017). But I struggle to square this high-minded aim with classroom pedagogy. Should character education form part of a teacher’s professional classroom practice too? And if so, what can each of our own subjects meaningfully contribute? These questions formed the basis of my firstyear research project on the MSc in Learning and Teaching in 2019-20, and what you read below is selected more-or-less directly from the literature review.

You might like to consider the questions for yourself. Here at Berkhamsted they are especially pertinent because our formal adoption of Guy Claxton’s Building Learning Power imposes a framework for developing ‘habits and attitudes’ that have been chosen to ‘help young people become better learners, both in school and out’ (Claxton, 2002). We should plan a third of our lessons in a way that explicitly promotes pupils’ ability to collaborate, explore, link, listen, notice, persevere, plan, question, reason, or review. These are character dispositions. But are they the only character dispositions we should be instilling through academic study in each of our own unique subject areas? In RE, for example, are we grasping the character potential of a subject that ranges so widely across religion, philosophy, and ethics?

In 2011 London was burning. Prime Minister David Cameron expressed horror at this August rioting with the familiar proposal that schools should cure our social ills. His government would seek, he said, a first class education that ‘doesn’t just give people the tools to make a good living – it gives them the character to live a good life, to be good citizens’ (Cameron, 2011). This grand aim wasn’t new in itself. Since 2002, UK schools have had a statutory duty to promote the spiritual, moral social and cultural development of their pupils (Education Act, 2002, c.32). But what followed was the explicit rise of character education as Conservative government policy (Jerome & Kisby, 2019).

It took a few years, but in 2014 Education Secretary Nicky Morgan formalised the building of character as one of her department’s aims (Arthur et al. 2017). Resulting projects included the Character Innovation Fund and Character Awards (Morgan, 2014) and later, under Damian Hinds, an advisory group to help schools self-assess their development of character education (Hinds, 2019).

This advisory group showed that there is a good appetite for character education in schools as well as government. Of the 880 schools that completed its character education survey, 97% of them ‘sought to promote desirable character traits among their students,’ but that nearly half were not directly familiar with character education (Marshall et al., 2017; White et al., 2017). Most secondary schools were motivated by their pupils’ future employability, alongside citizenship and academic attainment.

The new Ofsted inspection framework is now likely to spur overt character education in maintained schools anyway. The handbook for full inspections (Ofsted, 2019) now gives just as much weight to the personal development of pupils as to the quality of education they receive: if either is inadequate then a school may be placed in special measures (Buzzing, 2019). Character is specified as one of the most significant dimensions of this personal development.

Renewed focus on character education and the accompanying funding has spawned a ‘significant, multidisciplinary field of research’ (White et al., 2017), most notably the University of Birmingham’s omni-present Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. You will see them cited again and again in this article because since 2012 their researchers have utterly dominated the field with prolific paperloads of publication.

With government, Ofsted, and the massed firepower of education researchers on the case, there is no escaping character education. It’s certainly not an arcane Victorian interest.

So what actually is character education?

Policy announcements give the impression that character education is largely about improving a young person’s performance in challenging circumstances. The term ‘character’ rarely appears unaccompanied. Nicky Morgan speaks of building ‘character, resilience and grit’, and Damian Hinds pairs character with resilience. In its assessment of character education interventions, the Education Endowment Foundation conflates character with essential life skills. It’s the same with recent bestselling books about character. Authors tend to focus on particular characteristics and promote their benefits for individual or economic success (Jerome & Kisby, 2019). Character aspects highlighted include growth mindset (Dweck, 2008), grit (Duckworth, 2019; Duckworth & Gross, 2014), confidence and curiosity (Tough, 2013).

These popular ideas are limited, instrumentalist, views of character education because they focus on performance benefits alone. However, the theoretical work emerging from UK universities puts characteristics like resilience, grit, and confidence within a wider philosophicalmoral framework. It all has a long lineage. Earlier on I mentioned Aristotle, and the dominant

theory of character education is overtly Aristotelian (Jerome & Kisby, 2019). This is because in the Nicomachean Ethics he coined the foundational concept of hexis or ‘state of character’ (Aristotle, Ross, & Brown, 2009). Aristotelian person-based ethics were popular with some revision amongst early and medieval Christian philosophers, until Enlightenment thinkers instead pivoted towards rationalising the morality of individual actions and rules – rather than moral character of the person doing them. There was a belated revival of Aristotle’s virtue theory among 20th-century ethicists (Anscombe, 1958; Foot, 1978; MacIntyre, 1981) whose work informs modern exploration of character. There might be well-founded misgivings about the baggage all this entails (Kristjánsson, 2013), and challengers have emerged from other retro philosophies including Stoicism and Thomism (Gill, 2018; Hacker-Wright, 2018). Discussion can get rather niche: in January 2020 a character education conference at Oriel College, Oxford, comprised 52 papers discussing precisely what constitutes human flourishing (Jubilee Centre, 2020). Nonetheless, the dominant model currently has the advantage of offering a coherent philosophical framework to what might otherwise be a competing selection of characteristics.

So here is the York Notes version. The Jubilee Centre defines character in neo-Aristotelian terms as ‘a set of personal traits or dispositions that produce specific emotions, inform motivation and guide conduct’ (Jubilee Centre, 2014). Character education is an umbrella term for 'the cultivation of positive character traits called virtues' (Arthur et al., 2017). Through repeated choices, virtues form stable patterns which might be called habits or dispositions. Overall, ‘good character is a stable and well-integrated cluster of dispositions’ (Curren, 2017).

Character education is informed by the ancient Greek philosopher’s claim that eudaimonia (flourishing) is the ultimate good, that ‘good character contributes to a flourishing life’ (Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, 2014) and is ‘formed in large part through habitual behaviour’ (Pike, 2010). Despite the siren voices of instrumentalism, this philosophical-moral framework allows educators to justify building a wider range of character virtues than just the ones which make them good workers. Higher educational attainment, rather than being the goal itself, is a ‘happy side-effect’ of wider personal development (Arthur et al., 2017).

Why would this be a school’s responsibility?

Schools are uniquely well-placed to develop the character of our young people because they provide all-round opportunities for virtues to be ‘caught, taught and sought’: caught from the culture and influences that a pupil is exposed to; taught both in and out of the classroombecause virtues should be understood and reasoned; sought by the pupil freely pursuing 'varied opportunities that generate the formation of personal habits and character commitments' (Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, 2014).

Precisely what virtues should be encouraged? There is ‘no definitive list,’ and ‘particular schools may decide to prioritise certain virtues over others in light of the school’s history, ethos or specific student population’ (Jubilee Centre, 2014). Nonetheless, general categorisation could be applied to any shortlist. The Jubilee Centre’s Framework distinguished between four types: intellectual virtues (e.g. curiosity and reasoning), moral virtues (e.g. courage and honesty), civic virtues (e.g. citizenship and service), and performance virtues (e.g. perseverance and resilience) (Jubilee Centre, 2014). Overarching all of these, practical wisdom or phronesis helps the pupil judge what best to do when these virtues are in competition with each other (Arthur et al., 2017).

In very simplest terms, character education comprising intellectual, moral, civic, and performance virtues is about ‘developing good people’ (Jerome & Kisby, 2019).

Although a pupil’s whole life at school might be seen as a Vale of Soul Making, this doesn’t mean that character education must be taking place everywhere within it. Character development comes through habit and practice, so a classroom seems like the wrong place to expect it to happen. For an extreme illustration of this, look at university ethics professors: they spend their lives reflecting on right action, but are no better behaved than the rest of us (Schönegger & Wagner, 2019; Schwitzgebel & Rust, 2014)! Practical guides to character education emphasise the dangers of just bolting it on artificially as a classroom module (e.g. Roberts & Wright, 2018).

Nonetheless, individual subjects might have an angle on character and virtue that lets them contribute towards character education as a whole-school endeavour. To demonstrate this I look at the example of my own subject, and invite you to reflect whether your own has a place in the effort too.

Character is arguably the very subject matter of religion: ‘great religious texts – and great religious leaders, prophets and gurus – have all wrestled with such central questions as the need to grow in self-knowledge, build strong relationships, and live in a responsible, reflective and considerate way… Judicious exposure to the best that has been thought and said can lead directly to personal application – or rejection – of such considerations’ (Arthur et al., 2017). It is perhaps telling that the Jubilee Centre’s pilot project on developing virtues through the English curriculum explored C.S. Lewis’s Christianity-infused Narnia novels (Francis et al., 2018; Hart, Oliveira, & Pike, 2019). In RE, pupils already analyse role models who are ‘related to life in its full extent, including its moral complexities and ambiguities’ (Vos, 2018).

Despite this rich potential, since the 1970s RE pedagogies have been looking for a secular grounding (Gearon, 2014) tending to ‘studiously avoid’ looking at the inner religious life (Copley, 2008). Character education moves towards fixing this blind spot. Yet there is some doubt that the classic Thomist theological virtues of faith, hope and love could be accommodated in a way ‘relevant to those outside of particular faith communities’ (Carr, 2014).

Doubt can perhaps be overcome by limiting personal development to the moral rather than spiritual sphere. Focusing solely on moral virtues would not be much of a limitation, since suggestions for dispositions that can be developed in RE usually often turn out to be moral ones anyway (e.g. Felderhof & Thompson, 2014). And (Christian) moral education was previously a recurring feature of RE throughout the 20th century (Moulin-Stożek & Metcalfe, 2018). It might be that pupils are resistant to this since ‘many young people, whose beliefs are instinctively postmodern, will find it difficult to hold moral positions derived from religious beliefs’ (Kay, 2014), but at least the teacher’s role can be to give maligned views a fair hearing (Felderhof, 2014).

In Aristotelian terms, the point of this moral study is to develop pupils’ phronesis (good judgement). This has four aspects. First, the perception of virtue: ‘through engaging with ethical issues, pupils grow in their ability to discern the most important features of ethical situations and recognise which virtues are required to resolve ethical issues.’ Second, the conception of the ‘good life’: ‘where we understand the meaning and importance of virtues as part of a flourishing life and apply these in our lives accordingly.’ Third, virtue reasoning: ‘pupils gain awareness into how religious followers reach conclusions and grow in their own knowledge of how to integrate components of the good life in ethical situations.’ Finally, emotional regulation, where a calm exploration of ‘reasons why faith holders take action in their lives’ (Metcalfe, 2019) helps them ‘eschew the extremes of narrow rationalism and superficial emotivism’ (Barnes and Wright, 2006, cited in Metcalfe, 2019).

When surveyed, 98% of RE specialists agreed that ‘RE contributes to pupils’ character development’ and 94% that ‘RE teachers should model good behaviour for their pupils’ (Arthur, Moulin-Stożek, Metcalfe, & Moller, 2019). It is not clear, though, that this amounts to a mandate from teachers for explicitly educating character and virtues in the RE classroom. There is rather a difference between modelling good classroom behaviour and modelling a virtuous life! Respondents may have had the former in mind. Some further cause for doubt lies in the detail: teachers who themselves have a religious faith tended in the interviews to see exposure to religious teachings as the vehicle for pupils’ character development, while nonreligious teachers tended to attribute it to the practice of critical inquiry instead. So there seems to be fundamental disagreement here on the means and nature of implicit character education currently happening in RE.

Nonetheless, one popular theme emerges from those interviews. RE teachers feel that their subject offers a particularly strong contribution to the development of virtue literacy (Metcalfe & Moulin-Stożek, 2020). Specifically, the perception of specific virtues in action, reasoning about their wider application, and reflecting on one’s own development of them. This is in line with the opportunities outlined above, and is ripe for further research. My continuing MSc study explores how it could be practically implemented.

So, pending teacher buy-in and debate on the details, this is what RE might contribute to character education: ready-made historical examples of realistic moral and civic virtue with all its imperfections, through which students can become literate in what the virtues are and what they look like in reality. Ethical frameworks, both religious and philosophical, to analyse moral claims. Critical thinking skills – intellectual virtues – with which to do that reasonably. The potential outcome is well-developed practical wisdom, phronesis, which can then be exercised in other areas of school life.

What can your subject contribute?

BIO Edward Cain is currently studying towards an MSc in Learning and Teaching at the University of Oxford. He joined Berkhamsted in 2018, having previously taught RE, Politics, and History at a state boarding school in Dover. Edward’s scepticism of employability as the aim of education can be blamed on his rather gloomy first career in marketing.

While there is evidence that both China and Egypt saw the first schools spring up approximately 2000 years ago, the earliest forms of character education are usually ascribed to the Greeks (Doyle, 1997).

In the UK, character education has been seen as one of the advantages of a system of education which was established in boarding schools, and flourishes still in private schools. Successive Secretaries of State for Education have seen the breadth of education in independent schools as better educating character, and have sought to emulate it (DfE, 2019).

Character education is regarded by many as having a moral dimension. The Jubilee Centre at Birmingham University advocates a Neo-Aristotelian Virtue Development which is congruent with its Character Education focus. CS Lewis is often quoted as having said that 'Education without values, as useful as it is, seems rather to make man a more clever devil', but this is widely thought now to be a misquotation (O’Flaherty, 2014). He did say that education has intrinsic moral value: 'The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts. The right defence against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments. By starving the sensibility of our pupils we only make them easier prey to the propagandist when he comes' (Lewis, 1943).

The universality of underpinning values links CS Lewis’ writings to the programme put in place more than 20 years ago on the other side of the world, in New Zealand: Cornerstone Values sought to establish basic programmes to teach honesty and truthfulness, kindness, consideration and concern for others, compassion, obedience, responsibility, respect and duty in schools (Keown et al., 2005).

More recently still, the work of James Heckman, Nobel Laureate in Economics, demonstrates that ‘non-cognitive skills’ (which we may call character, or virtues) have at least as much effect on post-education ‘success’ as cognitive ability – or intelligence (Heckman et al., 2006).

If character education helps people both to do well and be well, then the question is: how? In the remainder of this article, three different approaches are outlined in three different contexts.

Here at St. Michaels University School, based in Victoria, the capital of British Columbia, Canada, we have an interesting perspective on character education. Of course, many of the leading HMC schools have several centuries of tradition that inform their view of character education in the present. Here in Canada, we are relatively unencumbered by the precedent and traditions of the past. Although our School has been in existence since 1906, it has only grown to full maturity since a merger between St. Michael’s School and University School in 1971.

Given that we are situated at the southern point of Vancouver Island, we have always been committed to the notion that the ‘great outdoors’ is the best classroom. Even though our campus is now urbanized, many faculty and staff will regularly take their classes outside in preference to the confines of four walls. This sense of engagement in the environment is of course very relevant today, with the rise in international concern for climate change and environment degradation.

We are also committed to the notion of leadership opportunity for all. My experience in the UK led me to believe that schools provided many wonderful leadership opportunities, but often unfairly biased towards the most capable. Here, we have a very egalitarian commitment to ensure that every individual is able to develop their own potential. Naturally enough, maximizing the advantages of our position, there are numerous programmes in the world of outdoor and adventure recreation. Winter survival training, constructing snow holes, and operating as a team take on a new urgency when the temperature outside is minus 25.

Although our School does not have the strong religious traditions of many in the UK, we do seize every opportunity to emphasize our values, courage, honesty, respect and service. These four themes are repeated like a mantra and used in a plethora of different contexts multiple times every day.

On arrival in 2018, I have to confess to a degree of cynicism about how effective this would be. Four years of experience has taught me that it actually works. Every student from Kindergarten to Grade 12 knows our values and has to relate to them as they make every day decisions around the School. Of course, failure to live up to any of these values presents a tremendous learning opportunity. Almost everyone can recognize when they fall short.

Here in Canada, since the publication of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Final Report in 2015, all schools have taken steps to engage with their Indigenous neighbours in a spirit of learning, and in a desire to reconcile some of those aspects of history of which we are least proud.

This year started off with a whole-school ceremony where we received four spindle whorls, which are the manifestation of our four values as depicted by Indigenous artist, Dylan Thomas. 1 A deliberate attempt to connect more meaningfully with Indigenous heritage and culture gives us a new perspective on the future, with opportunities to take character education in a different direction.

Proximity to nature, respect for the environment, sustainability, non-hierarchical structure, and the importance of serving the community, particularly helping the disadvantaged members of it, are given new expression as we plan our character education for the future. All very much in line with Indigenous cultures evolved over millennia.

1 A spindle whorl is a weaving tool, traditionally made of amber, antler, bone, ceramic, coral, glass, or stone inserted into a spindle to increase or maintain the speed of the spin in the making of thread.

'We acknowledge that our school rests in the heart of Straits Salish territory, a living culture with its own rites, ceremonies, and unfolding history.'

'We honour the Esquimalt, Songhees, and WSÁNEĆ peoples - whose homelands we share and whom we recognize as our neighbours.'

The Society of Jesus (the ‘Jesuits’) was founded by Ignatius of Loyola, a Spanish soldier turned priest, in 1540. Ignatius arguably started one of the greatest educational movements the world has ever known. The Jesuits were known as ‘the schoolmasters of Europe’ and the Ratio Studiorum of 1599 standardised regulations of their schools globally. Today approximately one million young people attend a Jesuit school or university worldwide. Jesuits were innovators in education and created the concept that each year group should have a different curriculum. Year groups were named (and still are) Figures, Rudiments, Grammar, Syntax, Poetry, Rhetoric, etc. The foundations of the curriculum were the classics (theology, philosophy, Latin and Greek), but also including the study of native languages, history, geography, mathematics and the natural sciences. Astronomy is still taught in some Jesuit schools (including Stonyhurst) and the Vatican Astronomer is a Jesuit!

The Jesuit Pupil Profile has been developed by the schools of the British Jesuit Province as a successor to the Jesuit School Leaver Profile published in 1995. The new Jesuit Pupil Profile was launched in the schools in the autumn term of 2013.

Our aims in creating the new Jesuit Pupil Profile (JPP) have been:

• to propose a simple but challenging statement of the qualities we seek to develop in pupils in Jesuit schools, using key words which unfold Ignatius' own stated aim of 'improvement in living and learning for the greater glory of God and the common good.'

• to produce a profile that describes the whole process of Jesuit education (from age 3 or 5 or 11 or 17 - the common ages of entry into our schools in Britain) rather than that of a school leaver.

• to create a JPP image in the style of a tag-cloud which can be used alongside the formal statement. Both image and statement are designed to provide a rich resource to stimulate discussion in class, assemblies, retreats and liturgy, in meetings of governors, with school leaders, teachers, support staff and parents; and which can be used to explain to prospective parents the aims of Jesuit education.

The JPP proposes eight pairs of virtues that sum up what a pupil in a Jesuit school is growing to be. Alongside the pupil profile itself, we have developed a parallel statement of what a Jesuit school does to help its pupils grow in the virtues listed in the JPP. There is also a brief expansion of the profile explaining its gospel and Ignatian roots.

Pupils in a Jesuit school are growing to be . . .

Grateful for their own gifts, for the gift of other people, and for the blessings of each day; and generous with their gifts, becoming men and women for others. Attentive to their experience and to their vocation; and discerning about the choices they make and the effects of those choices.

Compassionate towards others, near and far, especially the less fortunate; and loving by their just actions and forgiving words.

Faith-filled in their beliefs and hopeful for the future.

Eloquent and truthful in what they say of themselves, the relations between people, and the world.

Learned, finding God in all things; and wise in the ways they use their learning for the common good.

Curious about everything; and active in their engagement with the world, changing what they can for the better.

Intentional in the way they live and use the resources of the earth, guided by conscience; and prophetic in the example they set to others.

Acknowledging that Berkhamsted is less developed in its thinking about character education than the Jesuit Foundation of Stonyhurst, it is striking, nonetheless that the plaque outside the Chapel records the values of the school in the time of Dean Fr y as being loyalty, simplicity, and discipline. Such a record is the exception rather than the rule. In this respect, Berkhamsted exemplifies the liberal tradition of English public schools that important matters of character were rarely written down; codification was not seen as necessary for character to be developed and celebrated through the breadth of the School’s endeavour.

The breadth of the curriculum (once the School had been wrestled back from the control of the Dupré family in the early nineteenth century) has for a long time included sport, performing arts and adventurous activity: the School boasts one of the oldest Combined Cadet Forces in the UK, for example. We approach character education therefore with the advantages of the more recently arrived – able to celebrate those elements of modern character which we believe to be relevant and important, and without being tied to traditions which have lost relevance or, worse, offend a different time and audience. At the same time, the history of the School allows the narration of stories (for example about the three Victoria Crosses gained by alumni, or the status of former pupil Euan Lucie-Smith as the first Black officer in the British Army) based on a rich history of achievement; these stories illustrate the education of character throughout the School’s history.

A great danger awaits those schools which place an explicit value on character: the attempt to turn character development into some sort of production line produces an industrialisation of the process. As Max Weber identified in the early nineteenth century, the attempt to turn organic processes into rationalised ones may be self-defeating, as it normally depersonalises processes, eliminates individuality, and thereby loses the essential ‘why’.

One advantage to tradition is that time tends to build an organic focus on human flourishing (‘eudaimonia’). Modern individualism might enable a school to ally this with an explicit acknowledgement that each person may define their own version of flourishing. Encouraging young people to have regard to the flourishing of their whole self, blending modern thinking with ancient wisdom, seems likely to this author to attract the young to attend to the development of their character rather than be unaware of the manner in which each action or habit is building up into a whole. All three approaches above give licence to value tradition and seek new expressions of their historic role in helping the young bring out the character within.

Character education is worth the debate it causes. It’s evident all over the world; it differs locally to meet local needs; it has a deep history; it has rich traditions, and modern expressions.

Perhaps the most surprising development in thinking about character is Heckman’s: that character education brings financial benefits to those who experience it (2006). Thus the least noble of reasons may justify the most noble elements of education…

The purpose of this article is to assess the ‘ground truth’ of character education culture and practices at BSG schools to provide a foundation for future strategic planning around character education.

The research questions addressed are:

Education theory and practice show a renewed interest in character education (see, for instance, Morgan, 2017, Kristjansson 2015, Jubilee Centre, 2017) and the strategic direction of BSG makes ‘developing remarkable people’ a priority. Character education is one key element that underpins this strategic priority.

This study used a mixed-methods approach using an abridged version of The Jubilee Centre’s Character Education Evaluation Handbook for Schools. Quantitative research involved a four-question survey distributed to all parents, staff and KS3+ students in BSG. 809 responses were received. Qualitative research took place in which nineteen key stakeholders from across the BSG teaching community were interviewed. Those interviewed oversee areas of the school in which character education is believed to take place. The qualitative research followed the same methodology as Character Education at Eton College (Centre for Innovation and Research in Learning, 2019)

Which character virtues are most valued by the Berkhamsted School community?

What is Berkhamsted School currently doing to support the development of these virtues?

What action should we take to better support the development of these virtues?

‘What Makes a ‘Remarkable Person?’

1. There is significant interest in character education among parents and staff. To this voluntary survey there were 247 replies from parents, 127 replies from staff and 434 replies from students. Many respondents added detailed comments at the end of the survey. All key stakeholders interviewed spoke about the importance of character education in their area.

2. Berkhamsted provides a wide range of opportunities for character development, meeting most of the published studies’ examples of best practice. For example, Arthur et al., (2017) lists the following examples of best practice: developing virtue literacy, co-curricular activities, civic engagement (including volunteering), partnership with parents, role modelling and opportunities for dialogue.

3. Staff and parents agree that ‘Resilience/Persistence’ is the most important trait for BSG to develop in its students. This was also the most frequent trait identified by school leaders as being important. Students only ranked this as 13th most important out of 25 traits listed.

4. There is no significant overlap in the character traits ‘which the school should develop’ between students on the one hand and staff and parents on the other (persistence, integrity and empathy feature in staff/ parents' top four traits; these do not feature at all in the students’ top six traits, although both staff and students put ‘confidence’ as number two).

5. Students, parents and staff agree that their key hopes for young people centre on ‘being the best version of themselves’ (a simplified view of ‘flourishing’) rather than objective measures of success and achievement, or collectivist views of an equal society.

6. Several school leaders believe that as both a diamond school and large school group that takes in children at nursery age and can educate them through to Sixth Form, BSG has unique opportunities for character development. Some of these opportunities are yet to be fully realized.

7 The language used by school leaders to describe character education, and possibly their understanding of what character education means, is diverse. In addition, no evidence was found of character measurement tools being used, planning of wholeschool approaches to character, parental engagement programmes centred on character or a whole-school organized approach to character education.

Quantitative data review (student, parent, and staff survey)

Creativity 142

Curiosity 114

Open-Mindedness 117 Love of Learning 80 Honesty 177 Courage/Bravery 129 Persistence/Resilience 117 Zest 66 Kindness/Service 160 Love 81

Empathy/Social Intelligence 151 Fairness 169 Leadership 120 Teamwork 205 Modesty/Humility 78 Self-Regulation 69 Appreciation of Beauty 36 Gratitude 115 Hope 68 Humour 157 Confidence 194 Citizenship 68 Integrity 151 Environmental awareness 59 Self-motivation/autonomy 129 Other 11

250 200 150 100 50 0

Which character strengths are most important for BSG to develop in its students? 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0

STUDENTS:

1. Teamwork (n 205) 2. Confidence (194) 3. Honesty (177) 4. Fairness (169) 5. Kindness/ service (160) 6. Humour (157)

Creativity 50 Curiosity 75 Open-Mindedness 101 Love of Learning 70 Honesty 81 Courage/Bravery 76 Persistence/Resilience 152 Zest 30 Kindness/Service 81 Love 28 Empathy/Social Intelligence 101 Fairness 45 Leadership 37 Teamwork 60 Modesty/Humility 40 Self-Regulation 39 Appreciation of Beauty 8 Gratitude 58 Hope 23 Humour 26 Confidence 118 Citizenship 19 Integrity 118 Environmental awareness 22 Self-motivation/autonomy 97 Other 14

Fig 1. Which character strengths are most important for our school to develop in its students? (students’ response)

PARENTS:

1. Persistence/Resilience (152) 2. Confidence (118) 3. Integrity (118) 4. Empathy (101) 5. Open mindedness/ critical thinking (101) 6. Self-motivation/ autonomy (97)

Fig 2. Which character strengths are most important for our school to develop in its students? (parents’ response)

Creativity 20

Curiosity 39 Open-Mindedness 43 Love of Learning 33 Honesty 35 Courage/Bravery 25 Persistence/Resilience 73 Zest 11 Kindness/Service 51 Love 9 Empathy/Social Intelligence 56 Fairness 31 Leadership 11 Teamwork 31 Modesty/Humility 23 Self-Regulation 26 Appreciation of Beauty 4 Gratitude 34 Hope 10 Humour 13 Confidence 39 Citizenship 12 Integrity 67 Environmental awareness 22 Self-motivation/autonomy 42 Other 5

80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0

STAFF:

1. Persistence/Resilience (73)

2. Integrity (67) 3. Empathy (56) 4. Kindness/ service (51) 5. Open mindedness/ critical thinking (43) 6. Self-motivation/ autonomy (42)

Fig 3. Which character strengths are most important for our school to develop in its students? (staff response)

School leaders recognized the importance of character education and in each area there existed a range of opportunities for character development amongst students. Most school leaders made links between character development in school and a wider vision of a flourishing society (a key principle in neo-Aristotelean character education).

Most school leaders believed that ‘resilience’ was among the most important traits to develop:

Several school leaders believed that there are more opportunities to leverage the through-school/ diamond school opportunities at BSG.

The language used by school leaders to describe character education, and possibly their understanding of what character education means, is diverse. In addition, no evidence was found of character measurement tools being used, planning of through-school approaches to character, parental engagement programmes centred on character, or a BSG-wide organized approach to character.

It will come as no surprise to students, parents, and staff that Berkhamsted School is a community where character is valued and opportunities for growing in character are abundant. That said, BSG still has some distance to travel if we are to truly embody the vision of the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtue’s Framework document:

'The sensible question to ask about a school’s character education strategy is not, therefore, whether such education does occur, but whether it is intentional, planned, organised, and reflective, or assumed, unconscious, reactive, and random.'

Therefore, the following recommendations are made: i) create a common language at BSG around character; ii) leverage the throughschool/ diamond school opportunities at BSG to develop character over the students’ time at Berkhamsted; and iii) character instruction should focus on a values-led, meta-cognitive approach, rather than developing a pre-selected list of virtues. By building on its strong foundations in character education, Berkhamsted School will not only fulfil its aim of ‘developing remarkable people’ within our own community but can go on to provide guidance and resources for many other schools seeking to embed effective character education programmes.

BIO Ben Kerr-Shaw is Head of Churchill House and Teacher of Religious Studies and Philosophy at Berkhamsted. He is completing his final year of a Masters programme in Character Education at Birmingham University.

Music is performed, but lyrics are written. Written in song books, journals, on scraps of paper, on napkins, on iPhones, on laptops, iPads, tablets; they are written, edited, re-written and crafted in much the same way that page-born poetry is crafted. Where poets craft their lyrics to particular rhythms and meters – iambic pentameter, trochaic tetrameter – songwriters and lyricists craft their verses to a musical beat, melody, or harmony. The care and effort are no less worthy of consideration, however, and the mass appeal of popular music, the global commerce that it creates, and cultural critique that its content stems from, almost demand that greater literary attention is paid to the lyrics that constitute popular music.

Literary critic Adam Bradley claims that the work he undertook for his 2017 The Poetry of Pop consisted of listening to pop music ‘for hours, really for years, to the detriment of my ears and the betterment of my being' (2017, 5). If we both interpret ‘betterment’ to include moral and virtuous benefits, then it is plausible to argue that pop lyrics hold ethical value, and that this ethical value can be utilised in the classroom. I consider this a helpful refocusing of Bradley’s use of the term, particularly with regards to the application of moral development of students. We listen to music for pleasure, but I contend that we can go beyond the simple pleasures of listening to pop songs, and, through a close analysis of pop lyrics, particularly those that address moral issues, see ‘betterment’ from a moral perspective. This is helpful when considering the positive outcomes of analysing pop lyrics.

Literary texts, novels, dramas, poems, and films are utilised in education as tools from which we can develop morally and ethically, and yet songs, and specifically lyrics, are often overlooked. Equally, ‘good’ books, plays, and poems are analysed by scholars for their ethical value and content, and their moral value debated as a philosophical aim of good education (see, for example, Bohlin, 2005; Arthur et al., 2014; Kilpatrick, Wolfe and Wolfe, 1994). Indeed, the interest in the potential of the arts, generally, and literary narratives, specifically, to educate character has received sustained scholarly attention (see, for example, Conroy, 1999; Carr and Harrison, 2015; D’Olimpio, Paris and Thompson, 2022, forthcoming). Where ‘good’ books, tales, and other literary narratives are used in moral education, popular song lyrics are not as regularly considered as morally valuable tools for moral education. Some recent scholarly attention has been paid to popular music in debates over ethical and aesthetic value (see, for example, Stone, 2018). This has coincided with a rise in interest in moral education, particularly in terms of what constitutes moral/character education and what works in the classroom (see Arthur, Fullard and O’Leary, 2022; Morgan, 2017). As the moral development of young people can be framed as helping young people develop and acquire a sense of moral purpose, so a logical step for practitioners is to seek out theoretically sound tools that can support such outcomes (see Damon, 2009; Cotton Bronk, 2013). What pop lyrics offer, then, is content that is emotion-rich, descriptive, and depicts ethically challenging situations for a reader or listener to engage with, but presented in an aesthetically pleasing way that is ‘easier’ for teachers to use and students to engage with, due to pop’s mass consumption and commercial value.

We regularly turn to music, to our favourite songs, at times of emotional strain, or emotional pleasure. What we recognise in our favourite song lyrics are the ways in which lyrics provide comfort, familiarity and sometimes support. They help us escape, overcome loss, move past a metaphorical obstacle, and help us find a sense of purpose. That is not to say that the lyrics of Justin Bieber’s ‘Baby’ (2010) provide more insight into the idea of love than, say, W.H. Auden’s ‘The More Loving One’, or that Ed Sheeran is a ‘better’ story teller than Dickens. Such comparisons are unhelpful. What can be argued, though, is that the lyrics of pop songs contemplate ethical dilemmas, the excesses of vice, and topics of virtue, so provide rich and accessible content for discussion.

Most music listeners may be content to never consider the lyrics that they sing along to as pieces of poetry, to be poured over and analysed, but given the mass consumption, mass appeal, and emotion-rich content of pop songs, it seems essential that we consider the power that they hold over our lives, why we turn to them in times of happiness, grief, celebration, hurt. The themes pop songs discuss are more than trivial, surfacelevel discussions of love, lust, and loss. They are rich with emotion, with feeling, with vice and with virtue, driven by the lived experiences of the artist/songwriter made accessible to all, or created by the committees that write to manipulate the listener into feeling a certain way. Much of this ‘manipulation’ is achieved through the rhythm and melody of the song, as much as the content and structure of the lyrics, but let us consider some examples to emphasise my point.

The role of the singer/artist is important, particularly when a lyric is presented in the first person. Whilst there is undoubted separation between the singer and their lyrics, artists often draw inspiration from personal experience. Artists seek to engage their listeners, or in the words of Kanye West, ‘first I snatched the streets then I snatched the charts / First I had they ear, now I have their heart’ – ‘Never Let Me Down’ (2004). West raps that he has moved from capturing the ear of his listeners, to getting them to love him, accepting him and also following his every word. As we are considering the poetry of pop, here, interestingly, the J. Ivy verse in the track was originally penned as a poem.

Yet virtue is not always depicted positively, as The Killers tell us in ‘Human’ (2008), ‘Pay my respects to grace and virtue / Send my condolences to good’. ‘Human’ is a song that contrasts being ‘human’ with being ‘dancer’ or puppet-like, on strings. Brandon Flowers, lead singer of The Killers, doesn’t conclude whether he is either human or dancer, asking the question a total of nine times in the lyric. In speaking in the first-person plural, the lyric

includes the listener in the dilemma, of whether they are alive or being on strings, asking the listener to ‘let me know’ and participate in the debate.

A third example can consider the virtue of gratitude, a philosophical ‘hot topic’ in terms of recent research into virtue and emotions. Gratitude is conceived of as taking a triadic structure where three variables interact, the beneficiary, the benefit, and the benefactor (see Arthur et al., 2015). Whilst there are other conceptual approaches to gratitude that do not require there to be a beneficiary, we can understand gratitude to be a virtuous emotion that has generally positive connotations attached to it, even a moral virtue, that evokes a positive emotion, and valuable for a flourishing life (Kristjánsson, 2018).

‘Thank You’ by Dido (1998) is a song that has gained huge commercial success. In the lyrics, there is a benefactor, a beneficiary, and a benefit all present, fitting the requirements of the philosophical structure. Even though the song only says ‘thank you’ four times throughout, the juxtaposition of the depression and desolation experienced by the author in the verses against the gratitude and pleasure of the choruses is compelling. For context, the premise of the lyric is one of gratitude for sharing time with another during a bout of depression, with the singer presenting in verses one and two her feelings of sadness and depression at the circumstances of her life, but ending with positive emotions of seeing a picture of a loved one (verse one) and receiving a phone call (verse two), which reminds her that things are ‘not so bad’. Verse three then follows the same structure, but describes the presence of the partner being enough for the singer to temporarily escape the turmoil and depression of their life.

On the surface, the lyric is simply presented as a contrast between the despair of the author’s life with the cheer of experiencing the very ‘best day of my life’ in being with one’s lover. The acts of gratitude are multiple, and escalate in significance throughout the song; beginning with seeing a picture, to receiving a phone call, to being handed a towel when coming in from the rain, and culminating in seeing the lover and being in their presence. The author is grateful to the other party for being able to transport them from their state of depression into something that is ‘not so bad’. The unnamed other party is the benefactor of the gratitude, and the lyric itself is the articulation of it. The gift is being able to brighten someone else’s day by your mere presence, particularly if that person is experiencing depression or despair.

What endures in the lyric is the notion that however hard one’s life gets, it is always possible to lift them and provide them with a little bit of happiness through

one’s presence, through a phone call, picture, or a memory. The obvious interpretation is that the other person is a partner or a lover, but that is open to interpretation; it could be another meaningful person. The lyric appears simplistic and, perhaps even twee, but its popularity suggests that there is an enduring notion of gratitude that the listener can engage with and learn from. We don’t all need to have been in the depths of despair to be able to engage with the emotional uplift that a significant other can bring to us on good and bad days.

It is the reflection on that uplift, who is responsible for it, and how it ‘saves’ the author that creates the lasting meaning. Whilst we might feel a fleeting notion of thanks, a pang of love, or another positive emotion in response to seeing a picture, receiving a phone call, or returning home to see that person, reflecting on that emotion sufficiently to then thank the person for doing nothing more than being there is unusual. Perhaps the polarisation of emotions created in the description of the depression and the resulting uplift allows space to reflect and acknowledge the cause for the positive change in emotion. Regardless, the gratitude experienced and the description of that experience appear to fulfil the requirements of a ‘virtuous emotion’. It is not necessary for listeners to need to engage and empathise with the level of depression experienced by the singer, and it is plausible to think that the lyric expresses too much gratitude in response to relatively little action; however, such is the polarisation of the negative (‘I’m wondering why I got out of bed’, ‘I might not last the day’) and the positive (‘best day of my life’) creates a balance that works for Dido. We must also remember that this is a pop lyric, where repetition of choruses is a feature designed to move the song forwards, rather than a device to gauge the level of emotional content.

So, what is the purpose in deconstructing pop song lyrics in this fashion? Is it all moot, or can there be an educational benefit that aids reflection and ‘betterment’? Do we need to engage with a lyric in the detail we have begun to engage with ‘Thank You’ to gain pleasure from the song? No, of course not, but in reading and re-reading the lyrics, analysing their structure and form, as well as discussing their content in detail, we can engage with the lyric, the singer, and one another in terms of any virtuous feeling that is inspired by the song.

As I began with quoting Bradley, so I will close by quoting him again, ‘What artists do…is to take the everyday and make it unusual; to make us look at the things around us with new eyes, to listen with new ears. Great poetry of all stripes, great literature of all stripes has the capacity to do just that.’ (Bradley, 2017). Ultimately, if pop song lyrics are to be considered as useful tools for moral development, we must engage with them in a meaningful way – akin to how we engage with other forms of narrative art. I contend that where Bradley acknowledges that pop artists are taking everyday topics and everyday situations and making them appear unusual, and affecting how we see and hear those topics through rhyme and expression, so we can push further. Where pop lyrics engage us emotionally and ethically, even if initially only for a fleeting period, we can harness this potential for emotional and moral progress. If we encourage students to take time to analyse the lyrics of such songs, facilitate structured discussions on the meaning of metaphors and imagery and how they engage our emotions, then the opportunity to reflect on the emotional and ethical value is where this educational potential of pop lyrics can be realised.

Aidan P. Thompson works at the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham. He is part of the Management Team and leads on strategic and operational matters. He is also a PhD candidate in the School of Education, University of Birmingham under the title ‘The Ethical Value of Pop Lyrics’.

'What artists do… is to take the everyday and make it unusual'

Character Education as a concept appears self-explanatory, but it actually relies on a collection of smaller factors that ultimately have profound impact upon the jigsaw that makes up our personality. As such, I would argue that Character Education is the most important learning that takes place during our years at school, in that it makes up the basis of who we are today and how we shape the 'habitus', so to speak, within which we interact. Lao Tzu comes to mind here in that I firmly believe ‘Character becomes your destiny’ in that it shapes who we are and what we do, be that in exams or in the everyday fabric of our lives and it turns us into remarkable individuals.

At its core, Character Education is the subliminal shaping of an individual’s personal characteristics through other extracurricular activities or social processes. According to NatCen Social Research and the National Children’s Bureau, there are four key indicators and areas of learning which are essential to develop one’s character.

Developing the ability to remain motivated by long-term goals, to see a link between effort in the present and pay-off in the longerterm, overcoming and persevering through challenges.

Learning and habituating of positive moral attributes, sometimes known as ‘virtues’ (i.e. sense of justice).

The acquisition of social confidence (i.e. developing social mannerisms and listening skills). Having an appreciation of the importance of long-term commitments which frame the successful and fulfilled life.

More specifically, research has identified that the most influential place in which this is learnt is within formal education (Orchidadmin, 2021). The benefits of developing one’s character can be seen in the short run but more predominantly in the long term; the development of the aforementioned traits can not only improve individual educational attainment, but also is associated with better performance in the workplace, higher levels of self-control and more sophisticated coping strategies thus increased wellbeing. The Department of Education has thereby produced extensive recommendations as to how this can be done, and noted that it requires strong leadership, a diverse curriculum, and provision of a wide range of extracurricular activities.

In From Able to Remarkable, Robert Massey explores how this can be reflected within the school environment and suggests that students tend to be underestimated in their potential; he goes on to remark that good teaching is more important than ability for influencing student achievement (2019). In fact, he suggests, and indeed I concur, that by categorising students by ability in some cases we are in fact missing the true point of education (ibid.). We aim to push each individual to be the best version of themselves, not the best version of what is expected of their ability, and thereby inherently limiting their self-perceived potential. Thus, categorisation of students by ability could be considered a contradictory principle in some cases, reinforcing the importance of extra-curricular character development and a nurturing environment outside of class (Massey, 2019). Extensive studies have also shown that activities are good for the soul, making children feel better ‘physically, socially and mentally’ (ScienceDaily, 2010), and through years of reinforcement and expanding opportunities, students are left with generally higher levels of self-esteem and mental health. To that end, categories of activities can be perceived to develop specific ‘nutrients’ (Oberle et al., 2010) that feed this character development. For example, team sports are essential in building up social skills with teammates and coping with pressure, whereas the arts focus on building up creative expression and self-regulation. Therefore it is essential that all ranges of activities are available to young people to enable a broad development.

How does Berkhamsted ‘walk the walk’? What does this actually mean to me though? I take character education to be about turning everyday experiences into life shaping lessons that I carry with me always. I like to think of it like a ‘jigsaw of me’, as it were, and each activity or lesson learnt helped create my ‘future me’. Whether that be through my friends, the environment, or the activities I had the opportunity to partake in. I am profoundly grateful for what I have learnt and only having left Berkhamsted in 2021 can I begin to see the true breadth of the picture. My experience has taught me that I can face every challenge as an opportunity and progress towards curating my dream life through hard work, tenacity, kindness, and self-reflection. For this grounding at Berkhamsted I will forever be grateful.

To give a broad overview of how Berkhamsted does this we must first start beyond the curriculum, primarily looking at the phenomenal arts and sports programmes. The yearly productions and talent shows are always fantastic, including the occasional staff panto, accompanied by the annual house music competitions that always

promise good fun. The great music programmes also allow students to pursue any instrumental passions they may have beyond that, with accessible practice spaces for all students. Outside, the countless provision of sporting activities ranges from traditional sports like football and netball, to activities beyond the curriculum like fencing, climbing or fives, all of which anyone can join at any age or experience level (which was especially useful for me when I spontaneously decided to take up squash having never played it before).

Outside the hours of 08:30 to 16:20, there is also a huge amount to do. In my 15 years at Berkhamsted I was lucky enough to engage in the following activities: DofE gold, flying planes with the CCF, debating competitions, sports competitions (swimming and netball), choir practices, cooking club, as well as trips to Berlin, Washington, and Moscow. I also enjoyed holding two positions of responsibility in the form of House Captain and then later becoming Head Girl. This is just my personal snapshot of some of the amazing experiences provided for students, with even more being developed every day as the provision expands. To top it off, all of this is overseen by some of the most devoted and passionate role models I have encountered, and in my opinion, this is what helps deliver this personal development without us really noticing.

This development starts with the clear grounding of Berkhamsted key values in the heart of every aspect of life. To Aim High with Integrity, Be Adventurous and Serve Others are at the core of what is expected of any student. Berkhamsted doesn’t ask you to be anything you’re not. You don’t need to be the top scorer at netball or to walk out as the national debate champion to embody these values. I never felt I fitted into one group, I wasn’t sporty but I liked the outdoors, I wasn’t especially creative or musical but I enjoyed learning about these things, I liked academics but exams weren’t my life - I really didn’t know what I was supposed to be but I found as long as I tried my hardest to be kind and pushed myself to be better, it didn’t matter.

That is not to say this is an instant process. You don’t go on one 5-day hike in the Brecon Beacons and are suddenly ready to take on the world – I certainly wasn’t! However, even then I learnt something about myself, I’m stronger than I realised. Similarly, be it the CCF, or the school trips we were fortunate enough to go on, each opportunity provided us with a platform from which to grow. And even then, these are just some of the opportunities, let alone the collective possibilities, provided by Berkhamsted to its hundreds of students over the course of a possible 15-year school career.

I don’t think any single trait makes someone remarkable. Rather, their experiences, resilience and learning do and that all comes from Character Education. I have not been asked for my A-level results since leaving Berkhamsted, but I have needed all the skills it taught me every day at university, and I am still learning. Berkhamsted doesn’t produce one type of person, students aren’t all maths geniuses or sports scholars, there isn’t one mould that students must fit into to succeed.

What it does produce are well-rounded, determined individuals who have been able to make the most remarkable memories, friendships and develop life skills from their time at school. Thanks to the fantastic opportunities presented to them they are as prepared as possible to move onto the next stage of their lives. To me, this is what it means to be remarkable and the Character Education approach at Berkhamsted is the best way to help do this.

Leadership is a skill that all parents may reasonably hope their children will be able to achieve if they want to. Few parents would hope for their child to be lacking in independence, initiative or resilience. For some families, leadership may be an expectation or hope for their children. The local demography of Berkhamsted suggests that a large proportion of families will have a heritage of leadership, with parents or grandparents they might wish to emulate.

Leadership is both simple and complex. It may relate to having responsibility for a large number of people as in a company CEO, or for none, as in a newspaper columnist; it may require predominantly interactive skills as a developer of the capabilities of other people, or it may require inspirational insight in pushing the boundaries of human knowledge alone in a laboratory.

This article explores my thoughts on why I see leadership as important, why all schools should see leadership development as a core skill, and how we are approaching this at Berkhamsted.

I joined Berkhamsted Schools Group in September 2012 having spent twenty-four years in the Royal Marines. When I started at Berkhamsted I believed I understood the art of leadership. I had been taught to lead, I led and taught leadership. I had worked within the MOD, FCO, UN and NATO in a variety of strategic, diplomatic and military advisory roles and led in operational environments such as Northern Ireland, Bosnia, Afghanistan and Pakistan. I taught diplomacy and strategic leadership at the UK Defence Academy as a Director and I believed I knew my stuff! I was wrong.

Moving into education I quickly identified that I did not know as much as I thought and I needed to adapt to my new surroundings. I took a keen interest to read widely about education, to review my thinking on areas such as emotional intelligence and my approach to empathy. I had spent plenty of time working in international settings working with diverse groups and recognised the strengths of it as well as the challenges. What I did not consider was how much time I had spent working with colleagues who were like me and this meant ‘Group think’ tendencies. Teachers are different, with different needs, views and ideas. I understood that ‘different isn’t wrong, it’s just different’ but I needed a rethink. I noted that teachers generally had more empathy and specifically the culture at Berkhamsted has a strong empathy thread, which supports both colleagues and pupils. I remember Andy Ford on his first day as Vice Principal saying to all staff during his first INSET day that at Berkhamsted “It’s okay to say you are not okay”. During my early years, my journey of self-discovery allowed me to think more about leadership and how to lead and continues to this day. The more I learn, the more I appreciate how much more there is to learn about leading and I feel more humbled by it.

I started in Outdoor Education, which is excellent for developing pupils in so many ways beyond the classroom. My aim was to help pupils to develop self-confidence through controlled exposure to risk and to link classroom theory, where possible, to the outdoors. Using techniques such as blank recall testing on navigation or weather fronts in a relaxed way on a mountain would reinforce learning in the classroom. A key strand of Outdoor Education is delivering expeditions for the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award. Approximately four hundred and fifty pupils are involved in the scheme at Berkhamsted in any given year and each pupil must take part in two, a practice and a final. I am sure you can imagine this means a lot

of expeditions, but it also provides a great opportunity to see a large cross section of pupils across Years 9 – 13. Every expedition group is required to deliver a presentation on their expedition. Watching pupils present each week, I was struck by a lack of leadership and noted how nervous many were. Some students were excellent, mostly those who regularly participated in activities such music and drama. However, the majority lacked confidence. This was the moment that I knew I wanted to introduce leadership development at Berkhamsted.

In September 2019 we started the program with Year 10 pupils. I knew I needed a vision and the support of the school community. My desire was, and still is, to provide knowledge and to encourage pupils to search out leadership opportunities to put theory into practice. Leadership cannot be developed through theory alone: creating experiential opportunities is key and I strongly believe that leadership skills can be developed by anyone. The vision I came up with is in the text below:

How am I aiming to achieve the vision?

We know it takes a village to raise a child. To deliver the vision above we need to create a community where staff and pupils have a leadership culture mindset. Staff buy-in and motivation is always key to delivering any strategy in an organisation. When I think of leadership, I think of three words - what, why and how. Much of my time is spent explaining the ‘why’ to as many pupils and staff as possible. Buy in and driving forward leadership will only succeed if pupils and staff understand why and are motivated by it. Culture here is essential and ‘culture will always eat strategy for breakfast’! Culture is core to my approach alongside resource development and identifying experiential opportunities.

The Outdoor Education team are developing some great resources and lead on the years 7 – 11 formal leadership training. Leadership lessons happen during Clubs and Societies for half a term and are linked to a list of components, which can be seen below.

The following qualities are being used as a framework for our teaching sessions. I see these skills as a complex collection that may be developed in different ways and at different speeds by different young people. No young person should be labelled either as having an obligation to lead, or as having no/low ability to lead, at an early age. In addition, children should not be exposed to a course, or construct, in which leadership is construed to be one particular combination of dispositions and skills, nor where it is static. In different contexts, the requirements of leadership will draw differently on a palette of skills and abilities which may be described, practised, and reflected upon during that period of a person’s life in which their brain contains most grey matter, and they are therefore most able to learn – from 0 -18.

To offer formal leadership training to build knowledge for pupils from years 7 - 12 and to create the conditions for all pupils to have the opportunity to lead as widely and as often as possible in order to gain experience and practice.

Years 7 – 9 and Year 11 take part in half-termly sessions, but Year 10 is a full year of weekly lessons. These are based on three distinct areas of public speaking, leadership theory, and debating. In Year 12 leadership sessions are run during private study periods to small groups of pupils on a voluntary basis. These are great opportunities for reflective discussions between pupils as well as providing deeper knowledge.

Leadership is learnt through leading There is a place for leadership theory and sessions specifically to develop the skills of leadership. My main focus for developing leadership is on giving students meaningful opportunities to lead. Experiential learning can be reinforced through the PLAN-DO-REVIEW model. It is important for students to experience leadership opportunities during their schooling, to learn the art of building relationships within teams, defining identities, and achieving tasks effectively. It also provides an opportunity to learn to identify and display effective communication and interpersonal skills. In short, students should be driven by real-world consequences of their leadership actions which aim towards intrinsic motivation, not teacher-imposed extrinsic, 'artificial' consequences.

This is not an aspirational statement, rather a statement of fact. All students will, at some point in the future, be in a leadership position. Students need to comprehend this reality and prepare for it. There is a need to extinguish the 'I'm not a leader mentality' and shift the focus from examples such as prefects and sports captains. There needs to be leadership opportunities in every academic year from Stepping Stones to Year 13. My aim is to 'plant seeds' so that later in life all students have the confidence to step up and take a lead.

Leadership is currently happening everywhere: through friendship benches at Pre-Prep to mentoring roles in the Sixth Form. Older pupils mentoring younger year groups in activities both academic and non-academic is a great way to expand opportunities. We have Year 12 and 13 pupils leading in a variety of roles from academic enrichment to supporting classroom teaching during private study periods.

Using the school's strong commitment to its three values to guide the leader ship model (Aim High With Integrity, Be Adventurous, and Serve Others) provides an ideal framework to build a leadership development project around. We can instil these values through leadership opportunities; my aim is to change how the students see themselves. We should be cautious about over-reliance on leadership models based on sport, business and warfare; although these are often interesting, we can probably learn more about good leadership by observing a manager in a charity shop than the Google board room.

Leadership skills are essential for personal development. Understanding how to lead yourself by becoming truly independent, and understanding how to manage your own time and become resilient is the first step to being a leader. Developing interdependence, so one can work with others and foster trust within teams is the second. The why is simple: the world beyond education is evolving rapidly and particularly post covid. More work-place environments are adopting remote working practices at least a few days each week. Opportunities for younger members of a team to learn in the office from more experienced staff is less common. So what? Pupils leaving education and entering industry will need to have the ability to survive independently, to build relationships online, and be proactive. They must be able to know when to comment, have the confidence to say what they believe and the emotional intelligence to know how to deliver points in a way that gains traction. This is where leadership skills take us into a different environment, where the building of socio-emotional growth mindsets and empathy, and developing soft skills will become desired by employers.

At Berkhamsted, we have chosen to seek to enable pupils to develop the many qualities and to encourage them explicitly to give instruction, practice-opportunities, reflection-opportunities and feedback in these qualities during their journey through the school. The acquisition of these qualities will be important to all pupils; some pupils may put them to use in a conventional way in conventional leaders. Some may not exercise obvious leadership which draws on positional authority or attracts the limelight; some may act as ‘trim tabs’ or environment changers in an almost imperceptible way; some may ‘merely’ demonstrate initiative, independence of mind, and emotional intelligence without choosing to lead; some may seek opportunities to influence, command or manage. All will gain from the qualities identified.

Great leaders are driven towards a mission that everyone can get behind. They know how to motivate a team. Developing a culture where leadership is just part of what we do at school will help to foster both a positive and motivating environment for staff and provide a high-quality experience for students. When pupils engage with pupil leadership it has a positive impact on their capacity for learning. This benefits everyone and is a win – win, which is always the best sort of deal.

BIO

Duncan Hardy