Fourth-year medical student Kenya Homsley felt nervous as she stood in front of the rows of long white envelopes laid out on banquet tables. In a 71-year-old ritual known as Match Day, at noon on the third Friday of March, thousands of medical school students nationwide open envelopes to discover where they will spend the next four to seven years training in a hospital or other medical setting.

“Deep down, even with all the nerves, I do feel like I’m ready. There’s so much more to learn, but I’m right where I’m supposed to be,” said Homsley. A native of Charlotte,

North Carolina, Homsley matched with her first choice, obstetrics and gynecology at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center in California.

Matches are based on an algorithm that pairs students with medical facility residency programs based on preference lists developed by both the students and the schools through rigorous application and interview processes. Under supervision, residents diagnose, manage care, and treat patients in their specialty, with increased responsibility over time.

“You will now be at the front lines. You will be the doctor that the patient will trust,” said Priya Garg, MD, associate dean for medical educa-

tion, urging students to remember the social mission that drew many of them to the school when they become residents and physicians.

“Many of you came in here loving social justice, equity. That was your journey to us, and that’s been your journey with us,” Garg said. “Do not forget your role in changing the way medicine will be forever. Use your voices and the power you have as a doctor.”

“On behalf of the faculty, I am delighted to congratulate you on reaching your Match Day,” said Dean Karen Antman, MD. “Most of you arrived at medical school in August 2019. You had a conventional medical education for the first semester and a half, through Feb-

ruary 2020, anyway. Then, COVID upended your education, starting with studying for and taking the Step 1 exam. Your clerkships were a totally unique experience.

“In addition to medicine, you learned flexibility and creativity—important skills in medicine—as well as disaster management, up close and personal,” Antman continued. “I’m pretty sure your generation of physicians will be distinctive.”

Originally from Ohio, Jyla Hicks graduated from North Carolina Central University and came to the school to work with underrepresented and marginalized patient populations. She was pleased to match in internal medicine with BU’s primary teaching affiliate Boston Medical Center (BMC).

“Just to have the privilege to continue to serve those systematically marginalized populations is my goal,” Hicks said. “I know, especially with the minority populations, it’s really important for patients to see providers who look like them, so I love that I’m adding diversity to the already diverse BMC staff.”

There was a point in his medical school education when Madhav Sambhu thought he may not have what it takes to be a doctor. But he took an extra year, switched his focus to neurology, and through mentors and family support, stayed motivated and hopeful. On Match Day, his efforts paid off as he matched at Emory University Hospital in his hometown of Atlanta.

“I struggled a lot, and I think there was a point at which I didn’t know if I was going to be a doctor. Today, I realized it was possible— that I’m going to do this,” he said.

Carolyn Wilson of Long Island, New York, who studied at Boston University for seven years as an undergraduate and medical student, matched in internal medicine with New York University Grossman School of Medicine and looks forward to working in a city hospital with similar clientele to BMC. “During that hour waiting to open up your envelope, your nervousness peaks,” she said. “I’m excited to be going back home after such a long time.”

Following graduation, 37 medical students will stay in Massachusetts, including 18 at

BMC, five at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, four at Massachusetts General Hospital, two each at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Children’s Hospital Boston, UMass Chan Medical School, and Tufts Medical Center, and one each at Cambridge Health Alliance and St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center.

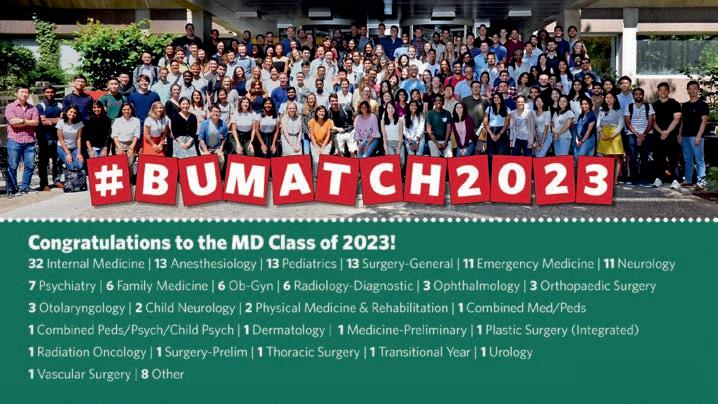

New York (22), California (17), and Connecticut (10) were the next most popular matched states. The class matched in a range of programs, with internal medicine (32), anesthesiology, pediatrics, and general surgery (13 each), and emergency medicine and neurology (11 each) as the top specialties. ●

2023

Match by State and Specialty

“Do not forget your role in changing the way medicine will be forever. Use your voices and the power you have as a doctor.”

PRIYA GARG, MD, ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR MEDICAL EDUCATION

As the school celebrates its 175th anniversary, the Class of 2023 is the first class to graduate from the newly renamed Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine.

Medical Campus Provost and Dean Karen Antman, MD, addressed students, family, and friends gathered at the BU Track & Tennis Center for the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine convocation ceremony on May 18.

Describing the 2023 MD and PhD graduating class as “creative, flexible, and resilient,” Antman spoke of the global pandemic that upended their lives and graduate education while also revealing disparities within the healthcare system. She cited wars and tensions around the world that have escalated and refugee numbers that have increased, “with many in our own patient populations.”

“In addition to science and medicine, you learned flexibility, adaptability, and creativity—important skills in both science and medicine, as well as in disaster manage-

ment—up-close and personal,” Antman said.

The school conferred 29 PhDs, 149 MDs, nine MD/PhDs, three MD/MPHs, and three MD/MBAs. Graduates ranking at the top of their class included 16 cum laude, five magna cum laude, and two summa cum laude graduates, Joshua Gustine and Flaminio Pavesi.

C. James McKnight, PhD, associate provost and dean of Graduate Medical Sciences, advised graduates to “continue to make a difference in the world, in your families, and in your communities. Be involved, take care of the world, be engaged, and speak out with your opinions. Your hard work here has prepared you, and we are confident that you have the necessary will, the courage, and the tools to make a difference in all our futures.”

One of many medical students who stepped up to help during the pandemic, graduating MD student speaker Divya Satish-

chandra and her peers started a call center for Boston Medical Center (BMC) patients to connect them with community resources.

Satishchandra aspires to a career in cardiology and will complete her residency at BMC.

“There will always be more to do, more to learn, more to innovate, more to fix. The field of medicine is ever-expanding and infinite,” she said.

She spoke of experiences like holding a human heart in anatomy class, the awe and existential dread of the learning process, and the tests that could open or close a door on a future career, all giving way by year three to the intangibles of patient care.

“We quickly learned that although multiple choice questions have one answer, real patient care involves multiple answers, or sometimes no answers. I think we’ve all learned that to be a physician is to embody qualities that may never be truly captured by a number, or any single outcome,” she said.

PhD student speaker Michael Breen noted that despite the array of degrees being awarded and the diverse careers represented,

“We are all bound by a common cause: the health and well-being of humankind.”

“The world, potentially now more than ever, needs caring and compassionate doctors and researchers,” said Breen, who received his PhD in microbiology with a focus on immunology and infectious diseases.

“During the pandemic, we all came together…in incredible ways. Selflessly, and before vaccinations were available, we all were on the forefront of the mass testing program, helping patients in any way we could and researching new treatments and diagnostics.”

Advising graduates to also credit themselves as they thank those who helped them along the way, Breen said, “There is no being here without your hard work, tenacity, and sacrifices.”

“There will always be more to do, more to learn, more to innovate, more to fix. The field of medicine is ever-expanding and infinite.”

STUDENT SPEAKER DIVYA SATISHCHANDRAAlissa Frame, MD/ PhD’23, gets hooded by Dr. Richard Wainford. Faculty Marshal David Greer, MD, chair and chief of neurology, leads the faculty into the MD and PhD convocation ceremony, followed by Dean Karen Antman and speaker Rochelle Walensky. Graduating MD students listen to remarks during the convocation ceremony.

General Hospital and studied vaccine delivery and strategies to reach underserved communities, spoke of the need to heed those who go largely unheard.

“Barriers may stand in the way of those we work with and care for, like poverty, poor housing, and unsafe or unhealthy environments, as well as lack of access to good jobs, quality education, and comprehensive, high-quality healthcare,” Walensky said.

“With your newly minted degrees, you have knowledge, you have wisdom, you have stature, and you have privilege,” Walensky continued. “And, I would argue, you now have a responsibility to not just use your voice for your own advocacy, but to use it for those who cannot otherwise advocate for themselves.”

She pointed out that the choice to listen and speak up requires the sacrifice of one of a physician or scientist’s most precious commodities: time.

“It will mean that when someone conveys an uncomfortable professional interaction that is so easy to gloss over, you will instead ask to hear more, unpack the details, sit with your colleague through their tears—even when you are overbooked with experiments and meetings,” she said.

Walensky advised graduates to be intentional about how they use their time and voice, and to use them for a purpose and for good.

“I ask you to use your voice to end the practice of marginalizing people, clinically and professionally, based on their identity,” she said. “I ask you to use your voice to eliminate the structural barriers to opportunity for everyone in this country. And I ask you to use your voice and the power of your research and your data to drive equity in policy change.

“Never in our history have our voices been so mightily important. You and I are so fortunate to be living in such an exciting time where great work and meaningful change for people of all communities and all backgrounds can happen not by accident, but because of your devotion; because you used your voice, and it rings clear.

“Keep your voice strong. Consistent. Compassionate. Be courageous and never give up.” ●

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, addressed MD/PhD graduates and their guests at the Convocation Ceremony on Thursday, May 18. Here, Walensky answers questions from students and faculty about her journey, women in leadership roles, lessons learned from the pandemic, and other issues facing our nation today.

Q. Please share with us how you got to where you are today.

A. My passion for public health became clear in 1991 during the AIDS crisis when the disease ravaged inner-city Baltimore, where I was completing my medical training. I remember admitting countless patients and feeling hopeless because we had little to offer clinically and therapeutically in the early day of the AIDS endemic. Challenging and touching conversations with patients ignited my call to service and fight against disparities. I would routinely call on those moments as a professor at Harvard Medical School, chair of the NIH’s AIDS Research Advisory Council, chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, and even today as the CDC director. My passion for disease prevention and treatment has remained steadfast, and I’m grateful to the mentors and collaborators who have helped me help others.

How do you feel about women in leadership roles?

Women in leadership are integral to producing fresh perspectives and new ideas. We must continue to offer opportunities, and support women in fields where they are underrepresented. Inclusivity throughout our public health workforce is

how we can create the best outcomes. This is why it is important that our workforce be as diverse as the communities we serve.

What are your biggest lessons learned during the pandemic or knowing what you know now, what would you have had the CDC do differently with regard to the COVID pandemic response?

I know the word is overused at this point, but the pandemic was truly unprecedented. Never in the CDC’s 76-year

history has the agency been forced to make decisions so quickly with limited and changing science. Before COVID-19, public health was somewhat unknown and chronically under-resourced. In addition, traditional scientific and communication processes in the context of a frail public health infrastructure left us woefully unprepared for the size and scope of COVID-19. At CDC, we are building on the lessons learned from COVID-19 to improve how we deliver our science and programs. These include:

“Women in leadership are integral to producing fresh perspectives and new ideas. We must continue to offer opportunities, and support women in fields where they are underrepresented.”

Sharing scientific findings and data faster: Release scientific findings and data more quickly in response to the need for information and action, as well as being transparent about the agency’s current level of understanding.

Translating science into practical, easy-to-understand policy: Enact a standardized policy development process for implementing guidance documents and other public health communications.

Prioritizing public health communications: Prioritize and enhance public-facing health communication practices and staff expertise.

Promoting results-based partnerships: Work more effectively with our public health partners to accomplish result-oriented goals and address the limitations of a siloed approach to solving major public health problems.

Developing a workforce prepared for future emergencies: Focus on diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility, and belonging to strengthen the CDC workforce’s response to infectious and noninfectious public health emergencies, including new skills, training, capabilities, and aligning incentives for commitment to these efforts.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic changed your thinking about how to handle emerging infectious diseases?

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted CDC’s role as a response agency. CDC is an exceptional science-based agency; traditionally, the agency has taken a more academic approach to our work. However, during the COVID-19 response, we learned that we must be a response-based agency, too, that can quickly respond to any emerging public health threat. I made this a priority for the agency to critically reflect on and implement lessons learned so that we can better prepare for future health threats. Through the initial implementation of my Moving Forward initiative, CDC is now disseminating science faster, communicating more efficiently, and becoming more of a response-based agency.

Given the gravity of the opioid epidemic and overdose-related deaths, how might it

be possible to create a national dashboard for reporting opioid-related deaths in as timely and detailed a method as we were able to achieve for COVID deaths?

CDC uses multiple sources to track the drug overdose epidemic. Examples of these systems include the Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology System and the Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System. CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics also provides monthly provisional drug overdose death counts.

CDC’s Overdose Data to Action initiative supports collecting and using this data to inform prevention and response efforts like prescription drug monitoring programs, community-level interventions, empowering individuals, and developing partnerships with public safety experts.

states becomes complicated and limits what we can provide in a timely manner concerning the national picture of overdose-related health outcomes.

What can be done to bolster faith in the CDC amongst groups that have turned away from science during the COVID-19 pandemic?

So much about trust is really about accountability. To bolster faith, we are acknowledging past mistakes and showing how we are working to do better in the future. This is a key focus in the CDC Moving Forward initiative I launched in August 2022. The priorities of Moving Forward include sharing data and decisions quickly, communicating uncertainty and developments, and sharing science and guidelines directly.

CDC has already started to put these priorities into action in response to recent public health threats. During the mpox response, CDC prioritized making timely data publicly available through web postings of key data finding including results of the American Men’s Internet Survey on behavior change and an early look at vaccine performance data. In both cases data were posted online even before they were packaged for publication. Similarly, CDC has continued to make timely and transparent data available on avian influenza through multiple and ongoing updates to our Avian Influenza Technical Report.

CDC is committed to building on trust through good science, good recommendations, and a good relationship with the public.

While CDC can get a national picture of overdose deaths from the National Vital Statistics System, this data can take time to collect and finalize. The additional data dashboards fill in some gaps, but the agency does not have the authority to require states to report specific, standardized data on overdose outcomes. As it does for most of its data, CDC relies on different surveillance systems, voluntary data sharing, or individual data use agreements to gather information from states and jurisdictions. Without standardized reporting, sharing and comparing this data across jurisdictions, cities, and

At CDC, our recommendations and public health decisions are based on science and protecting people. We must also recognize that public health policy impacts everyone and consider multiple perspectives. Coordinating across the government is critical when implementing our science-based policies.

As CDC director, I prioritized one-on-one conversations with legislators of all political parties so that they understand where we are coming from and what our science is

“I know the word is overused at this point, but the pandemic was truly unprecedented. Never in the CDC’s 76-year history has the agency been forced to make decisions so quickly with limited and changing science.”

telling us. I emphasize the significance of public health, the role of CDC, and the need for government support to protect our country’s health and security. Public health is a critical component of policy making, and it is important that CDC has a seat at the table and a voice in key decisions impacting the nation’s health.

Science has become politicized with results frequently cast as true or untrue. How can scientists communicate their level of uncertainty about their research…is there a way to cultivate an educated consumer base that understands how science works? Do you have any examples of scientists who are doing that now?

I have learned about the importance of communicating limitations and uncertainty

throughout the pandemic and during my time as CDC director. Ambiguity is a normal part of science and a fact of life; people deserve to know when they can expect changes. Part of CDC Moving Forward is communicating directly with the public using plain language and understandable resources. COVID-19 and mpox showed us that partnering with a diverse group of trusted messengers is critical in sharing our science and recommendations. To cultivate an educated public, we must earn and sustain their trust, prioritize diversity and accessibility, and be honest and thorough when uncertainty arises.

We should approach firearm injuries and deaths as a public health issue to accurately capture the complexity, urgency, and need for solutions. It must be understood that there is no single cause or solution to gun violence and that circumstances and needs vary across the country. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that, like many other public health issues, gun violence is often the result of poverty, racism, gender inequality, and other underlying social determinants. When we have this conversation in the context of a comprehensive public health framework, evidence-based solutions that protect individuals, families, and their communities become more conceivable.

Implementing safer public health policies is a team effort, requiring support from various partners. Looking through a public health lens, we recognize that we need to engage everyone on this topic, from gun owners to law enforcement. At CDC we have invested in research in this area spanning from firearm suicide prevention to safe storage of firearms in the home.

We all share the same goal of preventing adverse outcomes; let’s find areas where we agree and promote safe practices and interventions that can save lives.

What role can the CDC play in addressing the physician and healthcare worker shortages in rural areas?

A robust public health infrastructure requires a diverse workforce representing the communities they serve regardless of zip code. We are establishing the Office of Rural Health to build on our existing rural health work and provide a home for focused action and leadership. The goal is to integrate the best science and solutions to ensure that rural health needs are reflected in public health programs. We plan to make the most of this opportunity by developing a strategic plan, establishing federal leadership, integrating rural health into our major programs, and collecting better data to propose better solutions. A well-resourced environment and healthcare system are essential in attracting and retaining physicians and healthcare workers in rural areas. ●

The annual commencement ceremony celebrates a joyous passage in academic life, Medical Campus Provost and Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

Dean Karen Antman, MD, told the Graduate Medical Sciences (GMS) Master’s Class of 2023 as graduating students, their families, friends, and faculty assembled for the convocation ceremony at the BU Track & Tennis Center on May 18.

“The diploma you get today is the credential that grants you entry to the next stage of your life,” said Antman. Forty Master of Arts and 467 Master of Science degrees were awarded.

Antman noted that this academic achievement occurred in challenging times

for both education and personal lives, with loved ones, friends, and colleagues lost to a global pandemic that exposed the “health disparities that we in medicine knew existed but are now clear to everyone.”

“The faculty hope you have acquired the habit of continued, disciplined inquiry and that you are committed to contributing to the advancement of science,” said Antman. “We hope you will be the leaders in solving these problems.”

C. James McKnight, PhD, associate provost and GMS dean, urged graduates to use their education and training to effect positive change in the world.

“Your hard work has prepared you, and we are confident that you have the will, the cour-

age, and the tools that are necessary to make a difference to all of our futures,” he said.

Student speaker Darilyn Mahoney spoke of her plan to combine two passions—working with children and genetics—as a pediatric genetic counselor at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Mahoney described moving to Boston from her Maryland home two years ago as her first time being truly alone.

“No friends, no family, no familiarity, no community,” she recalled.

She found friends, mentors, and community, and successfully completed her master’s degree in genetic counseling, becoming the first African American to earn a degree in that program. She noted that her experi-

ence showed her that achievements come with challenges.

“From me to you, I say embrace discomfort, push for progress, and strive to support those whose voices need uplifting,” she said.

It was a long road to the speaker’s podium for Eaba Beyene, who was born in Ethiopia, moved to Canada when he was seven, and ultimately enrolled at Boston University to pursue an MS in Oral Health Sciences. He has been accepted into BU’s Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine.

Like Mahoney, Beyene urged classmates to show courage, take risks, and be unafraid of failure.

“Get out of your comfort zones and don’t let past negative experiences taint your capabilities,” he said. Beyene spoke of a goldfish that grows to the size of its watery environs, trading the safe confines of the fishbowl for the dangers of the pond.

“Even though the goldfish is in danger of becoming prey, growth was a product of a riskier environment,” he said. “I warn you

that there is no fun in a life that is risk-free and boring.”

Erika Minetti, who traveled from her home in Milan, Italy, to attend BU as an undergraduate before earning her MS in the Medical Sciences Program, reminded her fellow graduates that their journey is far from complete.

“Today, we are crossing the finish line, but it doesn’t end here. As individuals aspiring to become leaders in medicine and in the medical sciences, the marathon has just begun,” she said. “I have no doubt in my mind when I say that we will use everything we learned to fuel our future, no matter where we will be or who we will become.” ●

“Today, we are crossing the finish line, but it doesn’t end here. As individuals aspiring to become leaders in medicine and in the medical sciences, the marathon has just begun.”

STUDENT SPEAKER ERIKA MINETTI

Each year we receive questions about what are known as “legacy” admissions at Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, so BU Medicine sat down with Associate Dean for Admissions Kristen Goodell, MD, to discuss the topic.

How do you decide who is considered a legacy applicant?

Rather than “legacy,” we use the term “special-interest” applicant, which includes any applicant who has a particularly strong family or personal connection to the school. There is a place on the medical school application to note such a relationship, and applicants can use free text to describe their specific connection. We ask applicants to provide the name and graduation year or years of employment of their relative who has an affiliation with the school.

Generally, applicants whose parents or grandparents graduated from the school are considered special-interest applicants. We treat the children of current or former faculty and employees of the medical school the same way. We typically do not consider as special-interest applicants those whose parents or other relatives graduated from other schools or colleges at BU, or who completed a residency or fellowship at Boston Medical Center but did not graduate from the school. Occasionally, other relationships or connections with the school may merit special consideration, such as a sibling or a spouse of a current student.

What procedures does BU Chobanian & Avedisian SOM follow when a specialinterest applicant applies?

All applicants, regardless of their connection to the school, must meet our standards for admission. In other words, they must be competitive within our pool of applicants. We

use holistic application review, which means that we consider the applicant’s entire academic record and lived experiences. Accordingly, demonstrating a close connection to our school, understanding us well, and genuinely wanting to be part of this institution adds favorably to our overall assessment of the application.

If a special-interest applicant is not selected for interview, or if they are rejected after they are interviewed, they are offered follow-up counseling/application feedback by the associate or an assistant dean of admission.

How does carefully considering a specialinterest candidate benefit the school?

We want students who want to be at our school and share our commitment to the community served by Boston Medical Center, New England’s largest safety-net hospital. Medical school will be a better and happier place if the students in attendance feel positively about the school. In our experience, this positive association is often magnified if a student has a deep understanding of our mission; is dedicated to it and inspired by it. We have learned that students who have a parent

or grandparent who attended the school are more likely to better understand the school’s culture and to feel connected to the school from early on in their medical education.

Are there any challenges to considering special-interest candidates?

Each admissions cycle presents challenges because the number of applications from qualified candidates that we receive far exceeds the number of spaces we have available. In addition, special-interest applicants are more likely to have parents and grandparents who have college and graduate degrees and therefore, financial stability. However, we know that a diverse student population is better at solving complicated problems and that all students will develop a better and more nuanced understanding of the foundational principles of medicine if they are learning alongside classmates who are equally accomplished but have different experiences, expectations, and ideas. In our view, a more diverse physician workforce ultimately benefits patients. Our holistic review values these other experiences and obstacles overcome in our admissions process. ●

“All applicants, regardless of their connection to the school, must meet our standards for admission.”

Ateam of medical students made the Final Four of Innovate@BU’s BU Refugee Challenge with a proposal aimed at relieving social isolation and meeting the nutritional needs of 200 postpartum or pregnant newly arrived Haitian migrants.

In a field of 30 teams representing 16 of Boston University’s 17 colleges, one medical school student proposal, “Community Connection Through Cooking,” advanced to the finals, and a second team reached the semifinal round with a presentation called “Recipes for Refugees” about an interactive nutrition website.

“We were trying to develop creative ways to best incorporate systems we know are successful for increasing social support in a way that matches the specific needs of this population,” said Community Connection team member Leah Hollander (CAMED’23, SPH’23).

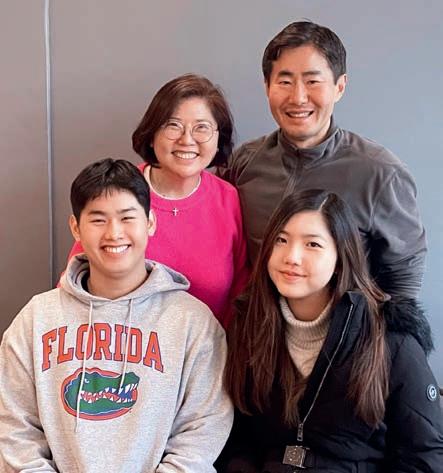

The Community Connection team included medical students Hollander, Hassan Beesley (CAMED’23), Heejoo Kang (CAS’20, CAMED’26), and Alyssa Quinn (CAMED’22, ‘26), and graduate student Gwendolyn Strickland (CAMED’25, SPH’25). The proposal— cooking classes focused on the affordability, cultural relevance, and dietary recommendations for pregnant people using Haitian recipes and ingredients, and adapting them to microwave cooking, a common cooking method in temporary housing—was a collaboration between the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine Refugee Wellness Student Group, Boston Medical Center’s Refugee Women’s Health Clinic, and the Teaching Kitchen.

The Recipes for Refugees team included first-year medical students Jessica Barmine, Monica Abou-Ezzi, and Emily Getzoff.

“We’d been incubating this idea of doing group nutrition classes as part of prenatal care,” said Sarah Kimball, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine and codirector

of BMC’s Immigrant Refugee Health Center (IRHC), which oversees and connects clients to programs like the Women’s Health Clinic.

Hollander and Beesley discovered that the biggest impediment to implementing their program was transportation cost, with more than $10,000 of a $13,000 budget earmarked for rideshare and other services.

“It’s a great lesson to learn that there are a lot of steps in between having an idea and operationalizing it,” said Beesley. “But I don’t think that should be a barrier to anyone trying to achieve an idea.”

“All of the pitches were incredible,” said Innovate@BU Program Director for Social Entrepreneurship Katie Quigley-Mellor, who oversaw this year’s challenge and expressed admiration for the medical students who put tremendous time and effort into the project

while maintaining rigorous academic and clinical schedules.

Managing the demands of a dual degree, Hollander, in short order, delivered her master’s thesis in public health, participated in Match Day—where she matched in a family medicine residency at University of North Carolina Hospitals—and prepped for the Refugee Challenge.

The Community Connection team worked in the Refugee Women’s Health Clinic at the IRHC.

“They have real, tangible experience, and that is the point of a cross-campus initiative—to get students from different colleges talking to each other, learning about different initiatives, and sharing skill sets and ideas,” said Quigley-Mellor.

Maria Gorskikh (Questrom’23) took the $10,000 top prize with Dream Venture Labs, a proposal that creates a place for refugees and migrants to develop their business ideas with the help of student volunteers from Boston-area universities.

The Innovate@BU Changemaker Challenge launched in the spring of 2019 with the Global Impact Challenge. They are sponsored through the BUild Lab IDG Capital Student Innovation Center that helps all BU students and recent alumni translate ideas into reality by developing innovation and entrepreneurial skills with the goal of strengthening communities.

Utilizing the “challenge” format allows for educational opportunities within a compressed time frame that includes a two-day retreat focused on taking an entrepreneurial approach to solving social issues; coaching; and connecting with local nonprofits and policy makers.

All semifinalists received $500 toward their proposal. Quigley-Mellor’s office encouraged semifinalists and finalists to take advantage of coaching and additional funding at the BUild Lab to continue working on their projects. ●

“All of the pitches were incredible,” said Innovate@BU Program Director for Social Entrepreneurship Katie Quigley-Mellor, who oversaw this year’s challenge and expressed admiration for the medical students who put tremendous time and effort into the project while maintaining rigorous academic and clinical schedules.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of two landmark programs, the Modular Medical/ Dental Integrated Curriculum (MMEDIC) and the Early Medical School Selection Program (EMSSP), which have created unique admission pathways to Boston University’s medical and dental schools.

For four decades, MMEDIC has served high-achieving BU undergrads who want to remain at the University for their medical degrees. Four years ago, the dental track was added, which provides a similar pathway for students to enter the dental school.

“MMEDIC is good for the medical school because we get great students, and it is good for the students because it takes some of the pressure off the medical school admissions process,” says Kristen Goodell, MD, associate dean for admissions.

Goodell says that 10 to 12 BU sophomores enter MMEDIC each year and commit to continuing their postgraduate medical education at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine.

In contrast to most medical school admissions processes, which are normally time-consuming and expensive, the MMEDIC pathway has candidates—all excellent students who have focused on medical school throughout their academic years—fill out one application in their sophomore year and do on-campus interviews before being accepted into the program. Provided they meet certain academic metrics, they are then guaranteed entrance into the medical school upon graduation, which, Goodell says, allows them to follow their intellectual curiosity when choosing other courses.

Once in the program, their undergraduate course selection is done in consultation with the MMEDIC director and must include four choices from a list of graduate-level courses chosen to augment a typical premed student curriculum and offering the opportunity to

study subjects such as medical ethics, public health, and medical anthropology.

“This helps them to develop into the kind of physician who solves really complicated problems where you have to pull knowledge from different fields and specialties to address what is going on with a patient,” Goodell says.

EMSSP is focused on recruiting underserved and underrepresented medical students from a consortium of historically

Black, Latinx, and Pacific Islands colleges and universities. Each year, 12 to 18 students are admitted to the program.

“These students have the native talent,” says Goodell. “What we’re trying to do is address the external obstacles that often keep people out of medical school.”

An incredibly competitive process, getting into medical school can include deciding factors such as participation in research, clinical experience, and volunteer or paid work, all of which are often much more difficult to achieve in lower-resource settings, especially without the aid of family and friends. An undergraduate college or university with the resources and experience to keep students on track and prepared is invaluable.

EMSSP students enroll in six weeks of summer courses at BU prior to their junior year and eight weeks of BU coursework— including an MCAT preparatory course— prior to their senior year, which they spend at BU taking both undergraduate- and

“These students have the native talent,” says Goodell. “What we’re trying to do is address the external obstacles that often keep people out of medical school.”Samantha Kaplan, MD, celebrates with EMSSP graduate Jyla Hicks at the 2023 MD and PhD convocation ceremony.

graduate-level classes to prepare them for the intensive medical school curriculum.

Giving students the opportunity to spend senior year at an institution other than their undergraduate university sets BU’s EMSSP apart from similar programs at other medical schools, says EMSSP Director Ebonie Woolcock, MD, who also praises the built-in support system.

“There are a lot of programs that recruit people of color, or people from underserved backgrounds, but the support isn’t there after they arrive,” she says. “We give a much more personal approach to easing their transition into medical school and supporting them while they’re here.”

A Boston native, Woolcock was an EMSSP student while attending the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. In her first summer in the program, her father was deported to Jamaica and her mother died of cancer. Suddenly, at 19, she was the primary caregiver for her two sisters, ages 12 and 15. She says that Program Director Kenneth Edelin, MD, along with her fellow EMSSP students, helped her through that tough time.

“He shared that he had lost his mom when he was 14 and what his path was, and from then on, he had my back,” says Woolcock, who speaks with the EMSSP students after every exam. She stresses that the program helps with nonacademic, but important, aspects of the educational process, like navigating the culture of the medical profession.

Approximately half of the school’s Black medical students, and a quarter of the Latinx students, are EMSSP participants.

“We’re recruiting from places like Tougaloo, Mississippi, and El Paso, Texas, where students are coming from neighborhoods that are [medically] underserved,” says Woolcock. “That’s the beauty of the program, that we graduate people who go back home and work in underserved communities.”

Woolcock believes that EMSSP benefits everyone, not just those taking part in it.

“There are students who have never talked to a Black student before, and it’s an introduction to someone who is going to help them bridge the gap with their future patients because we are from the same background,” she says.

Please see the Alumni Stories series beginning on page 46 for profiles on six EMSSP alumni. ●

On February 21 and 22, more than 100 artworks created by Medical Campus students, faculty, and staff were on display in Hiebert Lounge during the two-day celebration known as Art Days

Keith Tornheim, PhD, an associate professor of biochemistry, is very pleased—and unsurprised—by the creative output he’s overseen as Art Days faculty advisor over the past 20 years. “The medical field, the health field, they have this other side, this creative side, in abundance,” he said.

A 33-year-old Medical Campus tradition, Art Days showcases a wide variety of art and artistic inspiration. This year, some works were drawn directly from work and study, such as the snakelike intertwining of embroidered hemoglobin, the glass and polyvinyl installation that resembled blood platelets draped over an IV line and bag, and a photograph of vegetables and fruits assembled as an exposed ribcage and heart. Others were fanciful, including a celestial migration of whales and Van Gogh’s Starry Night over BU’s new data sciences building.

Bhavana Ganduri, a physician trained in India and a graduate student at the School of Public Health, admired a painting of three dancers—an explosion of pink resembling the windblown petals of a chrysanthemum—by Ashley Davidoff, MD, a clinical professor of radiology.

“It’s beautiful,” Ganduri said. “These people are already great at their jobs, but I came to see how good they are at art—and, wow—I don’t know if artwork makes a person more complete, but I think it makes them more interesting.”

Second-year dental student Nathan Faynzilbergim mused that fellow dental student Han Chaoshi’s intricate miniature sculptures

of a pair of fantasy creatures fit his friend’s personality and professional choice.

“You can just see the immaculate detail he put into them, the steady hand it takes, and it makes sense since he is in dental school,” said Faynzilbergim.

LaKedra Pam, MD, likes to focus on things other people overlook, “or maybe don’t necessarily think are the prettiest, and make them look awesome.” An assistant professor in obstetrics and gynecology, Pam said architectural details grab her attention. One of her two photos mounted on woodblocks at the show showed the lines of a building rising into clouds and a brilliant blue sky.

“I think creative thinking is a big part of obstetrics,” she said. “And anything you do that engages another part of your brain helps.”

According to Kristen Segars, a fourth-year MD/PhD candidate, if you’ve got a creative side, it’s best to let it out. “You can try not to do creative things, try not to focus on art, but in the end, you’ll always find yourself doodling in your notebook,” Segars said, standing in front of the polychromatic dress she knit for the event. She noted that doing art can ease stress as well. “It kind of keeps everything in perspective, especially when there’s so much emphasis on the grind and always working.”

Second-year medical student Alexis Fearing said that her whirling mosaic maelstrom of jagged tiles arose from both a time of emotional turmoil and a love of meteorology.

“Art is a source of inspiration, and it’s important to seek out sources of inspiration because that’s how we have growth, how we make changes,” she said. ●

The names of the school’s basic science departments have historically represented the disciplines taught in medical school almost a century ago. New scientific disciplines—including structural biology, cell and tissue imaging, and data science—have evolved. After a comprehensive review beginning in June 2021, faculty and departmental leadership requested the names of some of our basic science departments be changed to more accurately describe the actual research done in their departments.

On March 8, 2023, the University approved the new names. Now, the school will need to update areas including department, faculty, and lab websites; the University Bulletin; course descriptions; campus and other signage; CVs, and publication submissions.

Diplomas and transcripts will change as of September 1, 2023. Students graduating in May and August 2023 will retain the former department names.

Speaking at a February 8 virtual symposium celebrating Rebecca Lee Crumpler, MD, four distinguished alumni reflected on their medical careers, their experiences at the school, and the personal impact of Crumpler’s legacy. More than 190 viewers registered for the event, sponsored by the school’s Diversity & Inclusion and Development offices.

Graduating from New England Female Medical College in 1864 (which merged with Boston University in 1873 to become Boston University School of Medicine), Crumpler was the first Black female physician in the United States. In A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts, she wrote that she was driven to pursue “every opportunity to relieve the sufferings of others” and chose to provide treatment—particularly to women and children—regardless of their ability to pay.

Crumpler faced racism and sexism as pharmacists refused to fill her prescriptions, fellow physicians shunned her, and she was denied admitting privileges at hospitals.

“The fact that the School of Medicine was originally a female medical college . . . speaks volumes to the emphasis placed on the importance of women in medicine. And then, to have a Black woman . . . at the end of the Civil War who actually graduated (with a medical degree) and was the first in the US . . . it just reemphasizes the school’s mission . . . in terms of understanding the importance of women, and women of color, in medicine,” said Patricia Williams (CAS’84, CAMED’89), former vice president of safety surveillance and risk management for Pfizer Pharmaceuticals.

Williams said the premed competitiveness during undergraduate years shifted to a supportive environment once she started at

medical school, which featured a fair amount of “tough love” but also staff, faculty, and students pulling together to help everyone.

As a medical student, Nancy Roberson Jasper (CAMED’84), a former assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center, was impressed by the school’s emphasis on community outreach. She recalled an incident where medical students went to the home of a man suffering from prostate cancer who was experiencing elder abuse and brought him back to the hospital.

“I thought that was so courageous, and how unique that was, that we had done that for this individual,” said Jasper.

The idea of serving the community locally and globally permeated her career, including a mission to the impoverished and war-torn West African country of Sierra Leone to investigate women’s health issues and infant mortality. She recently decided to leave Columbia University and a private practice in midtown Manhattan for a position as an OB/ GYN at the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx.

said her BU education “sparked her curiosity and made me look at medical problems . . . with a much more global view.”

She chose cardiology following the loss of her grandfather due to a heart attack. As a cardiologist, she was “intrigued by the heart and how the heart worked” and was drawn to consider the larger issues. A third-year rotation with attending cardiologist

Alice Jacobs, recently retired professor of medicine and vice chair for clinical affairs in the department of medicine at the school, showed her that women could succeed in what continues to be a male-dominated field. Her subsequent research work pushed her to investigate root problems—such as why women with heart issues were diagnosed so much later than men—and to help write American Heart Association guidelines on how to use diagnostic technology on women.

The coauthor of five books and coproducer of four documentaries including the Emmy-nominated A Woman’s Heart, Mieres lauded Crumpler’s book for making medicine understandable to the average person.

“I was inspired by my patients to translate all of the science into actionable steps,” she said. “So, I think, like Rebecca Lee Crumpler, with the intellectual curiosity and the solution-minded mindset that started at Boston University, I was able to join forces with colleagues to really help patients and people become empowered to be partners in their health.”

bit different, and the support for me might be a little bit different, was really, really important,” said Woolcock.

The larger social and medical issues behind teen pregnancy helped draw her into women’s health and to ultimately become an OB/GYN. Mentored by the late Kenneth Edelin, MD, while in medical school, Woolcock found that she was particularly interested in the surgical delivery of babies by Cesarean delivery (C-section).

Woolcock recounted a difficult C-section with a medical student observing. “I said to him, ‘so that’s not normal, that’s not what we normally do.’ But his eyes were so big, and I remember having that same moment when I saw my first C-section,” she said. “My eyes [were] so big, like, this is amazing. We went in the room with one-and-a-half patients, then came out with two.” The earlier experience had helped her connect the direct ways in which physicians help people, regardless of their life circumstances.

“For me, it was this whole idea of intervention and public health and [that] this is really a space where I, as a Black woman, can make a difference and use my hands, and within two minutes, I can actually make a difference in someone’s life,” she said.

Woolcock saw a life lesson in Crumpler’s solitary drive, and she constantly reminds her students of the importance of self-affirmation.

“I’m going to go back to where I really feel my roots are . . . to get back to the community for [whom] I had gone into medicine, to take care of women who had not had the opportunities that I had . . . who I knew couldn’t come and see me in my own practice because they didn’t have insurance,” said Jasper.

Jennifer H. Mieres (CAMED’86), dean for faculty affairs and professor of cardiology at Hofstra University’s Zucker School of Medicine,

Born and raised in Boston, Ebonie Woolcock (CAMED’10, SPH’10), assistant professor of obstetrics & gynecology, assistant dean for diversity & inclusion, and director of the Early Medical School Selection Program (EMSSP), was the first in three generations of her family to break the cycle of teen pregnancy and the first college graduate. Her background differs from the typical applicant admitted to medical school.

“Having deans and faculty who recognized that my path to the school might be a little

“In those moments, I remind myself that, ‘I’m the bomb. Do you know how hard I had to fight to get here? Do you know how smart I had to be to get here? Do you know whose shoulders I stand on? Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler did it, so can I,’” she said.

Jasper advised medical students not to be afraid of change, as she and most of the other panelists had made career moves that were often dictated by life circumstances.

“Be fearless,” she said. “There are going to be times when things are not going to go the way you expect them to, but then, there are going to be times when you’re going to have riches beyond your belief.” ●

“In those moments, I remind myself that, ‘I’m the bomb. Do you know how hard I had to fight to get here? Do you know how smart I had to be to get here? Do you know whose shoulders I stand on?

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler did it, so can I.”

EBONIE WOOLCOCK

Graduate Medical Sciences (GMS) is pleased to present three high-achieving graduating students with Outstanding Student Achievement Awards in the categories of Outstanding Research and Community Service.

These students have made exceptional contributions to their departments and communities during their time at GMS. Meet each awardee:

PhD in Molecular & Translational Medicine, Program in Biomedical Sciences

Outstanding Student Achievement Award: PhD Research Category

Claire Burgess matriculated into the PhD Program in Biomedical Sciences (PiBS) in 2017 and currently works in the lab of Darrell Kotton, MD, director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine (CReM) and David C. Seldin Professor of Medicine at Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine.

During her time in the Kotton Lab, Burgess has discovered two different methods for generating human alveolar epithelial type I cells (AT1s) from pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These cells, which form most of the gas exchange surface of the lung, had no previous human in vitro culture model and are difficult to access from primary tissue.

These difficulties limited scientific understanding of lung epithelial diseases like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

“AT1s have the largest surface area and are one of the most topologically complex cells, as well as one of the thinnest,” Burgess says. “They’re difficult to isolate because they get

shredded in the process. There weren’t any good culture model systems for these cells, and so we didn’t know a lot about them.”

Her research contributed to the Kotton Lab ultimately discovering how to grow iAT1s from different genetic backgrounds in 3D organoids, as well as in 2D air-liquid interface cultures. The lab has completed a provisional patent application for these lentiviral and media-based methods.

“Being able to generate [iAT1s] from iPSCs, not only have we managed to make a model for these cells, so that we can understand how they’re affected by smoke exposure or viral infections […], but we’ve also been able to understand a little bit more about their development and the signals that are involved in differentiation, and how that might be perturbed in different disease states like IPF and COPD,” Burgess says.

Burgess and the Kotton Lab also have demonstrated the role of nuclear YAP/TAZ signaling in the differentiation of human type I cells. She has generated a reporter iPSC line to track and purify these iAT1s, which she has shared with academic and industry-based labs across the country, like the Chobanian & Avedisian SOM Varelas Lab and labs on the University’s Charles River Campus, Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Novartis.

In 2021, Burgess was awarded an F31

National Research Service Award through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health for her research. The project, “Generation of Human Alveolar Epithelial Type I Cells from Pluripotent Stem Cells,” is posted on the preprint server for biological sciences, bioRxiv. Burgess successfully defended her dissertation on February 9, 2023.

Burgess is very grateful for her Outstanding Student Achievement Award.

“I’ve been doing this research for five years, so the successes come spaced out with as many if not more failures,” she says. “When you condense all the successes into a single paragraph [for the award application], it suddenly seems very impressive. It’s funny to be able to look at that paragraph and think, ‘Wow, I really have done a lot.’”

Master’s in Medical Sciences (MAMS) Program Outstanding Student Achievement Award: Master’s Research Category

Born and raised in Milan, Italy, Erika Minetti moved to Boston in 2015 to pursue a BA in biochemistry & molecular biology with a minor in music performance at Boston University.

Following graduation, Minetti spent a year as a research technician in the lab of Reiko Matsui, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, then another as a clinical research coordinator in a translational setting with Naomi Hamburg, MD, the Joseph A. Vita Professor of Medicine and chief of the vascular biology section.

When it came time for Minetti to apply to graduate programs, MAMS stood out as an excellent option.

“I’ve been doing this research for five years, so the successes come spaced out with as many if not more failures.”

CLAIRE BURGESS

“I’ve been doing research from 2017, since I was an undergrad,” Minetti said. “I have a lot of important mentors here from my research experience, in addition to all the professors that I’ve met and who have also guided me through my master’s. That’s also why I picked the MAMS program specifically.”

Minetti returned to the Hamburg Lab to write her MAMS master’s thesis, “Cardiometabolic Proteomics and Vascular Endothelial Health in Type 2 Diabetes.”

“What we found is that there are associations between abnormal vascular endothelial phenotype and serum biomarkers in T2DM,” Minetti said. “That was our main finding, and that was really exciting to write about and to understand.”

The Outstanding Student Achievement Award is well-deserved recognition of Minetti’s research and education before and throughout her time in the MAMS program.

Minetti dedicated her award to all of the mentors she had at BU, especially Hamburg and Matsui, as well as Robert Weisbrod, her senior lab manager, and Gwynneth Offner, PhD, director of the MAMS program and an associate professor of medicine.

“The great thing about all my mentors is that they helped me not only in my academics and in my research, but they also take the time to mentor me through the challenges I face in my life,” she said. “I’m incredibly grateful, and I don’t think I could have made as much progress without them.”

Physician Assistant Program

Jean Jacques describes her own experience as a refugee in the United States as an important part of her journey that ultimately led her to BU and to the service project that earned her the Outstanding Student Achievement Award.

The project, “A Warm Welcome for Babies & Families Winter Essentials Fundraiser & Drive,” came from her experience in her OB-GYN rotation at Boston Medical Center (BMC) in October and November 2022.

During that time, Jean Jacques spoke with many refugee patients in the labor and delivery unit. Hearing their stories, she learned that many of these mothers and their families were adjusting to the cold Boston winter weather for the first time.

People with type 2 diabetes are more vulnerable to developing cardiovascular disease, and endothelial dysfunction is one of the early indicators of cardiovascular disease. Vascular endothelial cells make up the innermost layer of blood vessels.

To better understand what drives endothelial dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes, Minetti and her team obtained serum from people who have type 2 diabetes and nondiabetic controls.

The serum was used to assess levels of cardiometabolic markers using two O-Link panels. The biomarkers of which levels were significantly different in the two groups are involved in metabolism, immune function, apoptosis, vascular effects, and fluid homeostasis, but some of these biomarkers have many different cellular and physiological functions.

The lab also collected endothelial cells from both groups, stimulated them ex vivo with insulin, and measured the fold change in levels of phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (p-eNOS), an enzyme in the pathway that produces the potent vasodilator nitric oxide (NO). Then, they correlated the biomarker findings with p-eNOS levels.

Outstanding Student Achievement Award: Master’s Community Service Category Born and raised in Portau-Prince, Haiti, RhodeArmelle Jean Jacques and her mother sought refuge in Miami, Florida, due to ongoing political instability in their home country.

Jean Jacques completed high school and her undergraduate degree in Miami, graduating from the University of Miami in 2016 with a bachelor’s degree in biology and a minor in chemistry.

She also obtained an MPH from George Washington University in 2020 before starting the Boston University Physician Assistant (PA) Program in 2021.

Completing BU’s PA Program has given Jean Jacques several opportunities to serve her community, as the Greater Boston metropolitan area is home to the third-largest Haitian population in the United States.

“Haiti has a special place in my heart because it’s home,” Jean Jacques said. “The fact that I’m able to practice medicine and do what I do and be able to give back to my community is very special to me.”

“There really is a need here to have [these patients] be able to make an easier transition and then to get them the help that they need,” Jean Jacques said.

Jean Jacques spearheaded the project and partnered the Physician Assistant Program with BMC midwives to collect supplies and raise funds for frequently needed items, such as portable cribs, car seats, diapers, and clothing. The fund also collected donations of new and gently used winter coats and accessories to help keep families and their new babies warm.

To facilitate this project, Jean Jacques worked alongside BMC Director of Childbirth Education Cesylee Nguyen, CNM, MSN, RN, as well as PA Program Director Susan White, MD, and her classmates.

Jean Jacques recommends that all students try to step away from their studies from time to time and volunteer.

“There’s so little time, but a little thing can just make such a huge difference in someone’s life,” she said. “Even if it’s volunteering somewhere just for a few hours, whenever you have the chance, I think you’ll get a lot more from that than you think that you’re losing time-wise.” ●

“The great thing about all my mentors is that they helped me not only in my academics and in my research, but they also take the time to mentor me through the challenges I face in my life.”

ERIKA MINETTI

“There’s so little time, but a little thing can just make such a huge difference in someone’s life.”

RHODE-ARMELLE JEAN JACQUES

On April 21, Graduate Medical Sciences held the 29th Annual Henry I. Russek Student Achievement Day in the Hiebert Lounge with 98 students—the most in “Russek Day” history— registered to present their research.

Shelley Russek, PhD, organizes the event each year in honor of her late parents—Henry I. Russek, MD, a prolific physician scientist in cardiology, and philanthropist Elayne Russek— and to celebrate the ongoing achievements of the graduate student body at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine.

According to Russek, a professor of pharmacology and experimental therapeu-

tics, director of the graduate program for neuroscience, and president of The Russek Foundation, the mission of Russek Day goes above and beyond academic research by incorporating how students balance their research with service to their departments, their programs, and their communities.

“Each person getting an award today is giving something back to the community in balance with their outstanding research mission,” Russek said. “That’s behind a lot of what my family believes in and why we started this endowment 29 years ago.”

Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Medical Sciences C. James McKnight, PhD, applauded the presenting students on the caliber of their research at GMS.

“My job is to make sure that all you students get the best experience you can have while you’re on campus learning science,” McKnight said. “Hopefully, we’re imparting the joy of science. That’s our goal.”

David Housman, PhD, a Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor for Cancer Research at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a cofounder of Genzyme, was the keynote speaker. Housman is renowned for his contribution to discovering the HTT gene, which causes Huntington’s disease, the role of p53 in cancer, and WT1 in Wilms Tumor.

The Housman Lab uses genetic approaches to identify the molecular bases of human disease pathology—specifically

in cases like Huntington’s, cancer, and cardiovascular disease—and works to develop effective intervention strategies for fighting trinucleotide repeat disorders.

Shoumita Dasgupta, PhD, assistant dean for diversity & inclusion at Chobanian & Avedisian SOM, professor of medicine/biomedical genetics, founding director of the Genetics and Genomics Graduate Program, and former Housman lab member, introduced Housman to the audience, describing her time as an MIT undergraduate in his lab as her “origin story in genetics.”

Housman drew from his expertise in genetics and human disease and his team’s lab work to present “Treating Multiple Sclerosis: An MD/PhD Student Teaches Us.”

Students then introduced their research during a luncheon and poster presentation

● Devin Kenney, Department of Virology, Immunology & Microbiology

● Gian Sepulveda, Program in Genetics & Genomics

● Beverly Setzer, Graduate Program for Neuroscience

● Ioanna Yiannakou, Nutrition & Metabolism Program

Russek presented winners with certificates onstage, including 11 first prizes of $1,500, eight second prizes of $500, and five third prizes of $350.

The ongoing success of Russek Day stems

from the research accomplishments of GMS students and their dedication to their projects, their peers, and their departments, as well as the Russek family and Russek Foundation’s unwavering support of these student research and service endeavors.

GMS administrative coordinator James Mazarakis; Chobanian & Avedisian SOM student Alison Tipton; Pharmacology, Physiology & Biophysics Administrator Sara Johnson, and several other GMS staff members and students contributed to this year’s event. ●

In April, Ellen DiFiore, assistant dean and registrar for the MD Program, announced her plans to retire effective June 2, 2023.

DiFiore worked at BU in various roles since 1989, serving as a research assistant in pediatric infectious diseases, an administrative manager of the Primary Care Training Program in the department of medicine, and a project manager for the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Initiative. She was appointed the MD Program registrar in 2000.

access to their schedules, grades, and many services, and developed an online add/drop system for fourth-year scheduling. And when the school transitioned to remote operation during the pandemic, the service level remained exceptional.

session. Prior to the event, departments had selected the award winners, who proudly displayed stickers on their posters and nametags.

In the afternoon, 11 first-prize recipients delivered oral presentations of their research:

● Guillermo Arroyo Ataz, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine

● Anne Billot, Behavioral Neuroscience Program

● Morgane Butler, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology

● Andrew Chang, Department of Pharmacology, Physiology & Biophysics

● Jenna Libera, Department of Pharmacology, Physiology & Biophysics

● Liang (Martin) Ma, Graduate Program in Molecular & Translational Medicine

● Adeline Matschulat, Department of Biochemistry & Cell Biology

She received the University’s John S. Perkins Distinguished Service Award and the school’s Student Committee on Medical School Affairs Annual Service Award. She also served on the Association of American Medical College’s Group on Student Affairs (GSA) Committee on Student Records and was the secretary/treasurer for the GSA Northeast Region.

Under her leadership, the registrar’s office has provided outstanding service to students and graduates, implementing many changes over the years—including some suggested by the students themselves—in order to give them access to the information they need for success in medical school and beyond.

Among the changes, the office transitioned from paper and forms to electronic records, giving students 24/7

“It has been an honor to have played a small part in the success of the 3,800 graduates awarded the MD degree during my tenure. I have shared in their triumphs and disappointments and am proud of their accomplishments.”

“It has been an honor to have played a small part in the success of the 3,800 graduates awarded the MD degree during my tenure,” DiFiore said. “I have shared in their triumphs and disappointments and am proud of their accomplishments. The school has been my home and the students, faculty, and staff my family. I will miss them all greatly.”

The school thanks Ellen DiFiore for her many contributions to our community and wishes her all the best in the years ahead. ●

Nancy Sullivan, ScD, director of the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL), and Venetia Zachariou, PhD, chair of pharmacology, physiology & biophysics, have been installed as the inaugural recipients of the Edward Avedisian Professorships. The endowed chairs were funded out of the historic $100 million gift the late Edward Avedisian gave to the school.

“I believe they are most worthy inaugural Edward Avedisian Professors, and congratulate them,” Avedisian’s wife Pamela told a hybrid audience at the ceremony held in Hiebert Lounge that included faculty, students, friends, and members of the Sullivan and Zachariou families.

A longtime musician with the Boston Pops and Boston Ballet Orchestra, Edward Avedisian (CFA’59,’61, Hon.’22) was also a highly successful investor who quietly amassed a fortune. He made donations to educational programs and buildings in his ancestral country of Armenia as well as throughout Rhode Island and at the University, which renamed the medical school the Aram V. Chobanian & Edward Avedisian School of Medicine in honor of Avedisian and his childhood friend Aram Chobanian, MD (Hon.’06). Medical school dean emeritus and BU president emeritus, Chobanian attended the ceremony online.

Twenty-five percent of the gift is dedicated to funding endowed professorships.

A professor of microbiology and biology, Sullivan came to BU from the National Insti-

tutes of Health, where she was chief of the Biodefense Research Section at the Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID). An international leader in filovirus vaccines and hemorrhagic fever virus immunology, her team was first to demonstrate Ebola vaccine protection in primates and later developed Marburg and Sudan vaccines that are currently in Phase 2 human trials, in addition to a monoclonal antibody for Ebola that resulted in a nearly 90 percent survival rate.

Sullivan thanked family, friends, and mentors, noting that like SARS CoV-2, there are new viruses, still unknown and unstudied, that exist in animal reservoirs around the world.

Projecting a slide showing researchers in “space suits” that are worn while studying highly infectious emerging diseases in the highest-level containment labs at the NEIDL, Sullivan said, “We need to do that so that we can, ahead of time, develop therapies and vaccines for these viruses that we know are coming.”

Joseph Mizgerd, ScD, professor of medicine and the inaugural Jerome S. Brody, MD, Professor of Pulmonary Medicine, said he has been both friend and fan of Sullivan since the 1990s, when they were both pursuing their doctorates at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“I learned so much from her,” said Mizgerd. “I’m so glad to welcome Nancy to BU and congratulate her on this wonderful professorship.”

Zachariou joined BU in November 2022 from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, where she was professor of neuroscience and pharmacological sciences.

Karen Antman, MD, Medical Campus provost and dean of the medical school, introduced Zachariou, citing her work investigating chronic pain states and addiction at

the cellular level and her efforts in developing novel therapeutics for the management of chronic pain by targeting novel genes and intracellular pathways.

“Twenty percent of the American population suffers from very severe chronic pain conditions such as peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, chronic migraines, or chronic fatigue syndrome,” said Zachariou. “It’s important to develop novel approaches to break this vicious cycle of chronic pain, instead of simply suppressing symptoms.”

Given the ravages of a national opioid epidemic, one of her research goals is to develop alternatives to opioids as pain relievers.

“I’ve been extremely lucky to be surrounded by amazing trainees and colleagues. We’ve discovered new treatment targets. But more importantly, we connected with other scientists all over the world,” said Zachariou.

Alex Serafini, a postdoc in BU’s pharmacology, physiology & biophysics department who studied under her at the Icahn School of Medicine as an MD/PhD student, told the audience that Zachariou was an outstanding mentor.

“She forces people to become the best scientist they can be,” Serafini said.

Five Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine faculty have been honored as 2023 Educators of the Year by the school’s Awards Committee. The annual awards recognize Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine educators who demonstrate excellence in teaching and mentoring.

Nominated by students and faculty, this year’s recipients are Ricardo Cruz, MD, MPH, Educator of the Year, Preclerkship; Julia Bartolomeo, MD, Educator of the Year, Clerkship; Lillian Sosa, MS, CGC, Educator of the Year, MA/MS Programs; Douglas Rosene, PhD, Educator of the Year, PhD Programs; and Jia Jeannie Xu, MD, Resident Educator of the Year.

“I believe they are most worthy inaugural Edward Avedisian Professors, and congratulate them.”

PAMELA AVEDISIAN (HON.’23)Nancy Sullivan Venetia Zachariou

Ricardo Cruz is an assistant professor of medicine and a board-certified primary care physician in internal medicine. He has clinical expertise in addiction medicine and treats patients with substance use disorders at Boston Medical Center’s (BMC) Faster Path low-barrier bridge clinic and the Office Based Addiction Treatment clinic, where addiction treatment is integrated into primary care services.

He also works with individuals who have a history of incarceration, striving to mitigate reentry risk by reengaging them in primary care and behavioral services with a focus on the treatment of substance use disorders. As a member of the Academy of Medical Educators at the school, Cruz serves as the core advisor to a cohort of medical students for the duration of their studies and core educator for the doctoring courses, where students learn communication and clinical reasoning skills and knowledge.

According to his nominators, Cruz “has repeatedly demonstrated a passion for teaching first- and second-year medical students as they lay the foundation for becoming doctors in the Intro to Clinical Reasoning course. He loves engaging the students and encourages a deeper understanding of what can be learned through the physical exam. He provides ongoing support through mentorship and professional coaching to ensure Underrepresented in Medicine residents are retained and achieve success in the residency program.”

Julia Bartolomeo is an assistant professor of family medicine who sees patients at East Boston Neighborhood Health Center (NHC) and rounds on the inpatient Family Medicine service at Boston Medical Center (BMC) with residents and fourth-year students.

As associate director of the Family Medicine clerkship, she teaches third-year

students and serves as site director for those rotating at East Boston NHC. She was accepted into the inaugural Academy of Medical Educators in 2019, where she is an educator and advisor for first- and second-year students in the doctoring courses. She has been a field-specific advisor for many students applying to Family Medicine and served as faculty advisor for the Family Medicine Interest Group.

Bartolomeo’s nominators said, “Her leadership and commitment to the Family Medicine Interest Group (FMIG) during COVID was essential. As events were often cancelled or provided via Zoom during our first year, we did not have any experience planning in-person events when we became student leaders. She encouraged us to develop our own ideas, which allowed us to explore our interests in family medicine, including collaborating with the Geriatrics Interest Group to establish a joint event on the intersection of geriatrics and family medicine. She helped FMIG achieve its goal of increasing awareness and interest in family medicine in the preclerkship years.”

Lillian Sosa is a licensed genetic counselor practicing in the department of obstetrics & gynecology. The assistant program director of the genetic counseling master’s program, her primary responsibilities include overseeing and coordinating the fieldwork and clinical education curriculum. Sosa also manages students and faculty education for clinical supervisors in her region.

A nominator said, “Lillian is a deeply valued core member of our faculty who continues to elevate the quality of teaching for our program in the classroom and the clinic for

our students. She is consistently rated highly by students on her knowledge, experience, professionalism, mentorship, and teaching ability.” According to a student, “She has always gone above and beyond in providing in-depth feedback and tailors each day of the rotation to fulfill skills that I needed improvement on. I appreciate how open she is in receiving feedback and am always confident in being able to have a conversation with her.”

Douglas Rosene is a professor of anatomy & neurobiology and a world expert on the anatomy of the temporal lobe limbic system, an area in which he has published extensively. He is also recognized for his work in the neurobiology of cognitive aging and for 15 years served as program director of a long-standing NIH program project studying the neural bases of cognitive decline using an experimental model of normal human aging. He is the principal investigator or coinvestigator on several other NIH grants studying various aspects of aging and age-related disease in experimental models.