Above and Beyond the Call of Duty

Military service made these alumni better physicians, leaders, and people of purpose.

Page 28

Learn Critical Skills on the Other Side of the Bed BUMC Donates 50 Microscopes to 3 Boston High Schools

Military service made these alumni better physicians, leaders, and people of purpose.

Page 28

Learn Critical Skills on the Other Side of the Bed BUMC Donates 50 Microscopes to 3 Boston High Schools

Dear Alumni, Friends, and Colleagues, As we welcome the new academic year, we also welcome our new BU president, Dr. Melissa Gilliam, a member of our OB/GYN faculty.

Several other leadership transitions will occur over the next year. Dr. Tarik Haydar will return October 1 as chair of our anatomy and neurobiology department; Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones will join BU on January 1 as director of the Framingham Center for Population and Prevention Science, PI of the Framingham Heart Study, and chief of the section of preventive medicine in the department of medicine; and we currently have search committees for department chairs of medicine, surgery, and dermatology.

At the end of May I announced my desire to step down as Medical Campus provost and dean of the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. A search committee should be constituted soon and will take time to find new leadership. Meanwhile, I will remain in these roles until the arrival of my successor, and then plan to take a year-long sabbatical before returning to the faculty.

Serving as dean and Medical Campus provost has been a privilege. Over the past two decades, we built the medical student residence, extensively renovated our other facilities, regularly revised the curriculum, invested in new faculty and staff, substantially increased endowments for scholarships and professorships, and named the school. I am grateful to all of you who have supported these initiatives and provided wise counsel over the years. Thank you.

The school is in a great place and I’m sure that the University will have many exceptional candidates to lead this outstanding school of medicine.

Meanwhile, this issue of BU Medicine has many excellent articles. Our cover story highlights alumni who have become military physicians. Some choose to make it a career while others leave after fulfilling their active-duty commitment, but all agree that the rewarding experience has made them better physicians and leaders.

Boston University Medicine

Boston University Medicine is published by the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine Communications Office.

Maria Ober

Associate Dean, Communications design & production Boston University Creative Services

contributing writers

Lisa Brown, Gina DiGravio, Doug Fraser, Sarah Rowan

photography

Zoë Farr, Dave Green, David Keough, Jake Mackey, Sarah Rowan, School of Medicine Archival Photos, Sentara Health

Please direct any questions or comments to:

Maria Ober

Communications Office

Boston University Medical Campus

85 East Newton Street, M810H Boston, MA 02118

P 617-358-7869 | E mpober@bu.edu 0924

We showcase a unique program created by VA Boston Healthcare called The Other Side of the Bed, whereby medical students gain critical experience and skills from nurses and physicians who care for our veterans, and also tell you about a special gift of 50 labquality microscopes to three Boston secondary schools.

Our Giving section highlights the Third Annual Alan and Sybil Edelstein Professionalism & Ethics in Medicine Lecture, as well as stories on research supported by The PatientCentered Outcomes Research Institute, the Carol and Gene Ludwig Family Foundation, and the Edward N. and Della L. Thome Memorial Foundation, and features a profile on Mort Salomon, who credits the school for his satisfying, multifaceted career.

Our Alumni section announces our Alumni Award recipients. Louis Sullivan, MD’58, will receive the Dean’s Lifetime Achievement Award in Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in recognition of his outstanding career in medicine and healthcare leadership. Jennifer Luebke, PhD’90, and Christopher Andry, MPhil, PhD’94, will each receive the GMS Alumni Award in recognition of their scientific and leadership contributions to BU.

In addition to the always-popular Class Notes, the section also continues our Alumni Stories feature with a profile on Fredric Meyer, MD (CAMED’81).

Please enjoy this issue of BU Medicine

Best Regards,

Karen Antman, MD Provost, Medical Campus Dean, Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

Five faculty members received Edward Avedisian Professorships in a March 12 ceremony in Hiebert Lounge that included online viewers both in the US and abroad. The professorships were funded out of the $25 million set aside from the transformational $100 million gift from the late Edward Avedisian and his wife Pamela in 2022, which resulted in the school being named the Aram V. Chobanian & Edward Avedisian School of Medicine.

Last April, Nancy Sullivan, ScD, director of the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories, and Venetia (Vanna) Zachariou, PhD, chair of pharmacology, physiology & biophysics, were installed as the initial recipients of Edward Avedisian Professorships.

“We’re abidingly grateful to Ed and Pamela Avedisian for their generosity and the recognition that a great medical school is a precious renewable resource for our society and for the world,” said Boston University President Ad Interim Kenneth Freeman.

Freeman noted that the five endowed chairs did not bear the Avedisian name but rather, had been selected to honor others.

“We chose to name these professorships to honor individuals who not only achieved great success in their medical careers but have continually used that success to help others,” said Pamela Avedisian. “We want them to inspire the current and future generations of medical students.”

“In medicine, we often say that we stand on the shoulders of giants. Today you will be introduced to 10 remarkable leaders in medical sciences,” said Dean and BUMC Provost Karen Antman, MD,

who emceed the installation ceremony.

Toby Chai, MD, professor and chair of urology, was named the inaugural Richard K. Babayan, MD, Professor of Urology. Babayan, professor emeritus and former chair of urology, retired in 2022 after 43 years at the school. He was honored with numerous awards and in 2005, was the first in Boston to do a robot-assisted radical prostatectomy.

“I’m humbled by this experience and very grateful,” said Babayan, who introduced Chai, the urologist-in-chief at Boston Medical Center and president of Boston Medical Center Urologists, Inc. Chai previously held the John D. Young Professorship in Urology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and was vice chair of research in urology at Yale University School of Medicine. He titled his remarks, “Gratitude with a Purpose,” noting that the professorship was about more than one person: “It really is to help our department continue our academic mission to make it the best that it can be.”

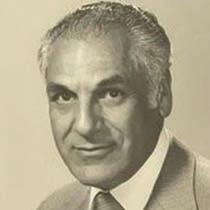

Rachel Fearns, PhD, chair of virology, immunology & microbiology, was named the Ernest Barsamian, MD, Professor.

Barsamian grew up poor in Syria, became a professor of surgery and faculty dean at Harvard Medical School, invented one of the early heart-lung machines, and was the chair of cardiac and thoracic surgery, chair of surgical services, and chief of staff at the Boston Veterans Administration Medical Center.

“From the earliest days of his medical career, our father worked tirelessly to balance leading-edge prowess in medicine, particularly surgery, with the compassion and humanity that marks the successful physician,” said his son, Peter Barsamian.

Originally from the UK, Fearns holds a PhD from the University of St. Andrews. Her research focuses on the transcription and replication of RNA viruses, like respiratory syncytial virus and emerging pathogens including the Marburg, Ebola, and Nipah viruses. Fearns frequently works with the pharmaceutical industry on small molecule polymerase inhibitors that help fight diseases by inhibiting their functionality.

“It’s such an honor to be the inaugural Barsamian chair. I’m excited to take this on,” she said. “My parents are educators and imbued in me the sense that education allows you to make choices in life.” She thanked her mentors, including Ronald Corley, PhD, recently retired as chair of virology, immunology & microbiology, who “built a wonderful department here,” and the department faculty who have helped mentor her students and elevate her science.

Hee-Young Park, PhD, professor and chair of medical sciences and education, professor

of dermatology, and associate dean for faculty affairs, was named the Carolann S. Najarian, MD, Professor. Najarian (CAMED’80) spent most of her career in private practice. In response to the devastating 1988 Armenian earthquake, she established the Armenian Health Alliance, delivering medicine and medical supplies and establishing a primary care facility and a center for expectant women. She was also assistant medical director at Middlesex County Hospital and an instructor in clinical medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“We chose to name these professorships to honor individuals who not only achieved great success in their medical careers but have continually used that success to help others,” said Pamela Avedisian.

“I know this chair will add significantly to the education of students here, enriching their medical education and preparing them to go out into a culturally diverse world to care for patients,” Najarian said.

Park said it took a global community to raise her and get her to where she is today. Born in Korea, she credited her father with believing that education was for all—including women. Arriving alone in Arkansas at age 15 to pursue science education, Park expressed her gratitude to the Blyholder family in Fayetteville, Arkansas, who sponsored and hosted her.

“Today would not be possible without friends, families, and colleagues,” she said.

Andrew Taylor, PhD, associate dean of research and professor and vice chair of research in ophthalmology, was named the Sarkis J. Kechejian, MD, Professor. An internationally known researcher in ocular immune privilege, ocular autoimmune disease, and the role of melanocortin pathways in regulating inflammation and immunity, Taylor thanked the Avedisians, his family, students, colleagues, and research collaborators, and paid tribute to his mentors, J. Wayne Streilein, MD, and Joan Stein-Streilein, PhD.

Kechejian (CAMED’63) is the president of KClinic in Texas, CEO and chairman of Alliance Health, and president of the Kechejian Foundation. He said his mother taught him “the necessity of being involved in the community and instilled in me concern for helping others.”

He is a longtime advocate for increased scholarships for BU medical students, especially to ease the financial considerations that exacerbated a chronic shortage of primary care physicians and other nonsurgical specialties, and has received the school’s Distinguished Alumni Award. The Avedisian gift included $50 million for student scholarships. Kechejian said the scholarship fund has grown from $5 million in 1996 to $150 million today.

The Edgar Minas Housepian, MD, Professorship went to David Harris, MD, PhD, chair of biochemistry & cell biology since 2009. Harris studies molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying human neurodegenerative diseases. His work on infectious prion diseases—like mad cow disease, where brain proteins fold and can result in neurodegenerative effects—has helped research into other diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases.

“What I want to highlight here is the incredible foresight to use that endowment ($25 million of the Avedisian fund is dedicated to research and teaching) to support basic research which is…always at the root of great medical discoveries,” said Harris. “I am honored to be associated with a legacy that values the pursuit of knowledge and scientific excellence.”

Housepian was a renowned neurosurgeon at New York Presbyterian Hospital and professor of neurology at Columbia University Medical School, where he taught for 44 years.

His career began in labs, then evolved to surgery, but education remained his key concern and in his retirement years, he was an advocate for international educational affiliations for medical students. “He was a very creative person with a long-range vision,” said his daughter, Jean Housepian. ●

Karen Antman

as BU’s Medical School Dean and Medical Campus

Provost

Transformational leader oversaw new facilities and faculty & a new school name

“ Karen hired me 10 years ago and over this decade, I’ve had the privilege of learning many things from her—like why use 10 words when one will do, short bullets not long paragraphs, select the right font, do not use CAPS on slides or reports, run it by legal counsel, and make sure you know the policy and follow it to the letter.

But what I really learned is what ‘collaborative leadership’ looks like. I learned that questions are good and encouraged and will be answered with patience fueled by her sincere desire to share knowledge and skill. Differing views are valued and encouraged. I deeply admire her sense of fairness and her ability to make impossibly hard decisions and saw what integrity in action looks like, with 100% commitment to the students.

At the end of the day, the bottom line is that it is never about Karen herself; she is all about supporting the success of others and making the school better. And that is exactly what she has done. With deep admiration, thank you, Karen.”

ANGELA H. JACKSON, MD ASSOCIATE DEAN, STUDENT AFFAIRS ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF MEDICINE

I have had the pleasure of working with Dean Antman throughout her two-decade tenure. During this time, she has steadfastly supported the VA’s BU faculty, academic vitality, and mission of caring for those who have served.”

MICHAEL E. CHARNESS, MD CHIEF OF STAFF VA BOSTON HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

Karen Antman, who led two transformative decades as dean of Boston University’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and provost of the Medical Campus, has announced plans to step down from those roles and return to the faculty at BU’s medical school as a professor of medicine when her successor is named.

Antman, a leading expert on breast cancer, mesotheliomas, and sarcomas, also presided over the construction of BU’s first medical student residence, throwing an affordable housing lifeline to students facing medical education bills. Antman oversaw the naming of the medical school in 2022 following a staggering $100 million gift from alum and philanthropist Edward Avedisian (CFA’59,’61, Hon.’22). She has led the Medical Campus since 2005 and says the pending inauguration of a fellow physician, Melissa Gilliam, as the new University president helped prompt her to step down from leadership.

“A new president—an MD—should pick their own new dean for the medical school,” Antman said. She also wants to spend more time with her family. “I plan to take a sabbatical. After a real vacation, I plan to “

collaboratively write infrastructure grants” for the medical school.

Kenneth Freeman, former BU president ad interim, said information about appointing her successor will be forthcoming in the next several months.

“Dr. Antman’s energetic leadership over the last 19 years has fostered a culture of excellence,” Freeman said, adding that under her leadership, the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine “has gained in reputation and attracts outstanding faculty, staff, and students.”

“Dr. Antman has been consistently committed to facilitating faculty and student research,” he added. “Faculty members have particularly appreciated the establishment of the Proposal Development office, which assists faculty in writing grants.”

Robert Brown, BU president emeritus, who worked closely with Antman during his 18-year tenure, said she “has been a wonderful leader of our medical school, demonstrating time and again her unwavering commitment to our medical students and the quality of their education. Her work has been recognized nationally, and she leaves the school well positioned to excel.”

The Medical Campus provost oversees the South End complex, which includes the medical school, the Henry M. Goldman

“

Dean Antman’s leadership has made it possible to smoothly transition to the establishment of a new department, setting up new cores and technologies, and expanding to new directions.”

VANNA ZACHARIOU, PHD, EDWARD AVEDISIAN PROFESSOR AND CHAIR, PHARMACOLOGY, PHYSIOLOGY & BIOPHYSICS

“

Throughout her tenure as dean and Medical Campus provost, Karen Antman strongly supported the Framingham Heart Study and BU’s Framingham Heart Study Center. Her advocacy has been essential to ensuring that this groundbreaking study, now in its 75th year, continues to make vital research contributions to the prevention of heart disease, stroke, dementia, and other health conditions.”

JOANNE MURABITO, MD, AND GEORGE O’CONNOR, PHD, CO-INTERIM PI s

NICK DI PERSIO, FINANCIAL & ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR

FHS CENTER AND FRAMINGHAM HEART STUDY

School of Dental Medicine, the School of Public Health, and the University’s collaborative role with Boston Medical Center, BU’s primary teaching hospital and New England’s largest safety net hospital.

Antman sums up her institution-changing tenure as “construction, fundraising, and recruiting the right leadership for the campus and school.”

The $100 million gift from Avedisian, an investor and for four decades a clarinetist with the Boston Pops and the Boston Ballet Orchestra, was a capstone to Antman’s tenure. He had suggested that the school be named after his lifelong friend Aram Chobanian (Hon.’06)—cardiologist, BU president emeritus, and dean emeritus of the medical school and provost of the Medical Campus. Neither man wanted his name on the school until they were persuaded to allow it to be named after both of them.

The gift enables $50 million for scholarships for medical students, $25 million to support endowed professorships, and $25 million to the Avedisian Fund for Excellence, paying for cutting-edge research and teaching.

Of the medical residence, Brown said at its 2010 groundbreaking, “This facility will make the burden of a medical education a little bit lighter to carry.” In recent years, MDs have been among the five degrees that account for most student debt.

Financial management of the medical school and campus involved more than the naming gift, especially during the first decade of Antman’s tenure, a time of flat budgets at one critical funding source, the National Institutes of Health. Antman says she nevertheless managed to recruit “outstanding, grant-funded faculty to new and renovated campus facilities, paid for by moving faculty to campus from off-campus rental space, thus decreasing costs and significantly increasing our research funding.”

She is proud of the “exceptionally prepared and accomplished medical and graduate students” that the medical school has attracted during her tenure. “We are now the top choice for many and turned down for only the most competitive medical schools.”

She led in opening more than 20 new research cores (shared research facilities) “to

“

The Boston University Genome Science Institute (GSI) is a vibrant research center that Dean Karen Antman played a key role in establishing at the beginning of her deanship to foster cutting-edge genetics and genomics research here on the Medical Campus as well as extending to researchers on the Charles River Campus. We are indebted to Dean Antman’s commitment to supporting the GSI research community, including delivering her address every year at our annual research symposium. We hope to continue her research support legacy in genetics and genomics for years to come.”

NELSON LAU, PHD

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, BIOCHEMISTRY & CELL BIOLOGY

GENOME SCIENCE INSTITUTE DIRECTOR

“

During my eight years as an associate dean, I had the privilege of working closely with Dr. Antman and witnessing her integrity, brilliant intellect, sharp wit, and dedication to educating future physicians and researchers. Her numerous accomplishments have left an indelible mark on our institution. While I am confident that we will be able to recruit a highly qualified successor, Dr. Antman’s legacy will be difficult to match.”

RAFAEL ORTEGA, MD, FASA PROFESSOR & CHAIR, ANESTHESIOLOGY

provide access to expensive, state-of-theart equipment,” she said, including the $8 million Center for Biomedical Imaging and the $4 million Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) Core Facility, opening this summer with a state-of-the-art electron microscope. Antman also cites the establishment of an office to assist faculty with grant writing.

BU’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center, created on her watch in 2008, has garnered international recognition for its research into the debilitating effects of repeated head traumas, in athletes and military especially. The center says its bank of 1,250-plus donated brains for study is “the largest tissue repository in the world focused on traumatic brain injury and CTE.”

Beyond new facilities, Antman supported the medical education faculty’s revised, team-based MD curriculum that necessitated “substantial renovations of every floor,” she said, in the Instructional Building—“including a 250-seat testing center, a 6,000-square-foot Team-Based Learning Lab, and completely renovated library floors.”

Before her BU service, Antman was deputy director of translational and clinical sciences at the National Cancer Institute. She also has served as the cancer center director at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (where she earned her MD

“ I became Chair of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine in 2019. The dean was extremely supportive of my candidacy and our department. Dean Antman provided mentorship and guidance along the way. We worked very well together over the past 4.5 years. I always found her open to discussion and forthright, judicious and thoughtful, available and supportive.”

CHRISTOPHER ANDRY, MPHIL, PHD, PROFESSOR AND CHAIR, PATHOLOGY & LABORATORY MEDICINE

“ Dean Antman has been a force at the School of Medicine over the past 19 years. Her creativity, vision, and dedication are why the school has the exceptional reputation it enjoys. I have learned so much from her about leadership and am grateful for all she has done to support me and the Department of Otolaryngology.”

GREGORY A. GRILLONE, MD, FACS, M. STUART STRONG AND CHARLES W. VAUGHAN PROFESSOR AND CHAIR, OTOLARYNGOLOGY-HEAD AND NECK SURGERY

and codirected the cancer care service line at New York–Presbyterian Hospital) and at Harvard Medical School from 1979 to 1993. At Harvard, she had hospital appointments at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and DanaFarber Cancer Institute.

She has edited five textbooks and monographs, authored or coauthored more than 300 publications, and written reviews and editorials on such topics as medical education, medical policy, and the effect that research funding and managed care have on clinical research.

Antman was elected a member of the National Academy of Medicine, an advisory group to the federal government, as dean, and chaired the American Association of Medical College Council of Deans. She also served as president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Association for Cancer Research. ●

“ In addition to an amazing career in academic medicine, you’ve been a truly excellent dean. The legacy you will leave behind is enormous and enduring. It’s been a privilege to serve as a chair under your leadership. Thank you, and best wishes for much good still to come.”

STEPHEN CHRISTIANSEN, MD, PROFESSOR AND CHAIR, OPHTHALMOLOGY

Focus should be on improving health beyond the healthcare system

“Healthcare is a basic human right, not a privilege. Our profession should focus on improving health beyond the healthcare system, in communities, with equal focus on prevention of disease and treatment of disease,” said convocation speaker Monica Bharel, MD (CAMED’94), MPH.

Medical Campus Provost and Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

Dean Karen Antman, MD, addressed a celebratory crowd of students, faculty, and friends gathered at the BU Track & Tennis Center for the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine convocation ceremony on May 16. Noting that graduation is one of the most joyous events of academic life, she also reminded the Class of 2024 that their degrees also confer considerable public trust.

With so much unrest around the world, natural disasters, and medical challenges on a global scale, “We hope that you will become leaders in solving these issues,” said Antman.

The school conferred 35 PhDs, 144 MDs, four MD/PhDs, three MD/MBAs, one MD/ JD, and two MD/OMFS (Oral Maxillofacial Surgery). Fifteen students earned cum laude honors and five, magna cum laude. Two students, Jonathan Berlowitz and Sarah Golden, graduated summa cum laude.

“The faculty know that you will use the knowledge, the research, and the clinical

skills that you have mastered here to make a difference in the world going forward,” said C. James McKnight, PhD, associate provost and dean of Graduate Medical Sciences.

“Humility reminds me of how far I’ve come and how much more there is to accomplish,” said PhD student speaker Josiane Fofana, who grew up in Senegal. After moving to Boston in 2011, Fofana completed an associate degree in biological sciences at Bunker Hill Community College, a BS in biochemistry at Brandeis University, and a PhD in virology, microbiology & immunology at BU.

Fofana urged students to look beyond their degrees. “In the pursuit of knowledge, we often overlook the importance of emotional intelligence. Brilliance devoid of empathy just renders us empty, contributing to the injustice in this world,” she said.

The mother of a toddler, Fofana founded a nonprofit that provides quality, STEM-based education to children in Dakar, Senegal. She is pursuing a postdoctoral position at the University of Ghana as a Fogarty Global Health Fellow.

“Do not think that the degree or leadership position you’re holding grants you the

ultimate wisdom on every issue,” she said. “Remain open to others’ experiences and embrace discomfort in order to grow.”

MD student speaker Bridgette Merriman grew up in Rochester, New York, graduated from Boston College, and will complete a pediatric residency at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. A childhood cancer survivor, she was hooded by David Korones, MD, her pediatric oncologist at Golisano Children’s Hospital in Rochester.

“One of the most beautiful aspects of our journey together has been the friendships we’ve formed and the shared experiences that have strengthened our bond,” Merriman said. “From our first days of orientation to the challenges of clinical rotations, we’ve grown together, supporting each other every step of the way.”

“I know that you have the minds, the hearts, and the souls of change-makers,” she said.

Monica Bharel, MD (CAMED’94), MPH,

formerly chief medical officer at Boston Health Care for the Homeless and commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and currently the clinical lead for public sector health at Google, encouraged students to consider global issues of health equity and socioeconomic impacts.

“Healthcare is a basic human right, not a privilege. Our profession should focus on improving health beyond the healthcare system, in communities, with equal focus on prevention of disease and treatment of disease,” Bharel said.

During patient interactions, Bharel advised students to turn away from their screens, look their patients in the eyes, and allow them to tell their story.

“Choose kindness and selflessness. Listen to your patients with humility. Connect your scientific endeavors to our most pressing health issues,” she said. ●

Told to make a difference with their education, training

On May 16, Graduate Medical Sciences (GMS) students, their families, friends, and faculty assembled at the BU Track & Tennis Center for the convocation ceremony marking a joyous passage in academic life. C. James McKnight, PhD, associate provost and GMS dean, urged graduates to make an impact on the world and in their own lives.

“You must continue to make a difference with the education and training you have received in your time here,” said McKnight. “Not just professionally; you should continue to make a difference in your families and your communities. Be involved, take care of the world, be engaged, and speak out.”

“The diploma you get today is the credential that grants you entry to the next stage of your life,” said Medical Campus Provost and Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

Dean Karen Antman, MD. “The faculty have great confidence in your creativity, resilience, collaboration, and commitment.”

Student speaker Brent Leung of Toronto, Canada, graduated from the Master of Science in Medical Sciences (MAMS) program—one of the oldest and most successful special master’s programs in the US that has prepared more than 3,000 students for medical school since 1989—and is headed into the University’s MD program this fall.

He fondly recalled studying electron microscope slides on his laptop when friends and other MAMS students spontaneously gathered around to help him in one of the informal learning sessions that continued throughout his two years.

“Bonding over practice questions, writing out pathways on whiteboards, going out for drinks after an exam—these are the memories that come to mind when I reflect on the past two years,” said Leung. “While I don’t know what the future holds for all of us, I do know that we all have the capacity to succeed.”

Representing the Physician Assistant (PA) program, student speaker and Texas native Ellie McIntosh admitted fainting during the

first surgery she attended as a high school student and described an undergraduate journey that shifted through four majors until she graduated with a degree in finance.

Working at an OB/GYN clinic in Dallas brought her back into medical science and healthcare, which she will practice as a PA in Boston. Like Leung, she spoke of the support she received from her classmates, faculty, family, and friends.

“My charge to you is to not let this fervor for life dissipate on those grueling days that will inevitably come as we continue this roller coaster of life,” McIntosh said. “We can treat, heal, and interact with people of all different backgrounds and socioeconomic status and help them fight for a truly better tomorrow.”

MS student speaker Aris Desai, also a Texas native who will return there to do research, echoed iconic New England poet Robert Frost. “The road less traveled is often rugged, and less signposted perhaps, but it is ripe with the promise of personal growth and discovery,” he said.

“Each lab experiment, each patient case study, and each research project was an opportunity to choose resilience over resignation, curiosity over complacency, persistence over surrender,” he reflected. “It is a testament to the idea that success is not just in the destination, but also in the journey.”

Forty-three Master of Arts, 323 Master of Science, and 10 combined Master of Science/Master of Public Health degrees were awarded. ●

On May 3 in Hiebert Lounge, anatomy students celebrated those who donated their bodies to medical education in a memorial service featuring songs, music, poems, and prose dedicated to honoring and thanking them and their families.

“We should always remember and honor their sacrifice and the sacrifice their families made in supporting their decision to donate their bodies,” said first-year medical student Sophie Gray to the audience of donor families, students, faculty, and staff. “As students, we will strive to continue their legacies by using the knowledge and skills we have gained by learning from the donors to make a positive impact on the world.”

Each year, approximately 45 donor bodies are required for instruction of 310–370 medical, dental, physician assistant, and graduate medical science students studying in the Gross Anatomy Lab. This year’s ceremony honored the 23 donors whose bodies were studied in anatomy courses held in the past academic year, with 77 family members present among the audience of 200.

“The donors came from all walks of life, but what united them was their selflessness,” said Gray.

“I have lived inside this amazing creation for 91 years,” one donor wrote in a letter to students. “How I envy you the opportunity to learn and figure it all out.”

Nancilee Fuller signed on as a donor in 1990. She worked as a restaurant and office manager

and for 20 years as a medical secretary in her local hospital, finally retiring at 80. Fuller loved to garden and was a member of a synchronized skating team until she was 75.

“She just loved being in the medical environment and always knew she wanted to contribute her body to science and further medical knowledge,” said her daughter Heidi Finnegan.

“I didn’t realize how emotional this would be for me,” said Finnegan when she saw her mother’s photo and heard first-year medical student Aaron Ramtulla sing one of her mother’s favorite Adele songs.

“I wanted to show my appreciation for these people, these families, and the donors,” said Ramtulla.

When students first open the body bag of a donor, Jonathan Wisco (PhD’02), associate professor of anatomy & neurobiology, asks them to gently place their hands on the donor.

“This is the first time they have experienced the gift of death, so that they can learn how to preserve life,” said Wisco.

“As soon as I saw the body, I felt this immediate sense of honor by the fact that

I had the opportunity to learn from them,” said Ramtulla. “I was overwhelmed with those feelings.”

Until around 20 years ago, the end of anatomy classes for the school year was marked with a moment of silence before students zipped up the donor bags for the last time and the bodies were sent to the crematorium. But Robert Bouchie, manager of the Gross Anatomy Lab and director of the Anatomical Gift program, realized that students wanted more, and the memorial evolved into a nondenominational, student-run ceremony that over the past decade also has included donor families.

One of 14 students on the ceremony’s organizing committee, first-year medical student Giulio Cataldo said meeting donor families at the ceremony completes the circle that begins when they are introduced to the donor bodies and learn about their histories through the physical manifestations—such as an enlarged heart, gallstones, or overdeveloped muscles—that they accumulated during life. The families are key to helping them reunite the body with the person who inhabited it.

“We get to know them very intimately and

personally, seeing their internal organs and hearing about their past medical conditions,” said Cataldo. “We were really looking forward to meeting the families. I’m excited to hear the stories about their loved ones.”

“I like that [the ceremony] is studentdriven,” said keynote speaker Monica Pessina (PhD’05), clinical associate professor of anatomy & neurobiology. “I think the families are very touched. You hear about the value of the body donation, but they see it and feel it from the students who are there.”

A United Methodist minister in life, Jim Todd was an advocate for peace, social justice, and LGBTQ+ inclusion in the church. He and his wife Mary decided to donate their bodies to BU nearly 30 years ago. Mary attended the ceremony. “You put your whole self in, and that’s what Jim did,” she said.

“The music was just absolutely beautiful. It was a wonderful service that I felt truly healed by,” said Todd’s daughter Julie. “He would have loved every minute of it.”

The program included an opportunity for the donor families and students to meet and talk while sharing a meal. First-year medical

student Keven Cheung sat with the Todds. “Hearing what kind of man he was really touched me because of the things he was fighting for,” said Cheung. “Connecting with them makes me appreciate the gift that much more, and makes me realize that every one of the donors had decades of life and experiences—things they fought for; hopes and dreams—that live on in the people they knew, in their families, and in us.”

At the close of the ceremony, donor families privately receive the cremated remains of their loved ones, with Bouchie personally delivering them to families unable to attend the service.

Gillian Sanders attended the ceremony with her brother Michael. “I can’t wait to bring her home,” she said of her mother Doris Sanders, who will be reunited with her husband Charles, who donated his body eight years earlier. Doris and Charles met in Germany during WWII; she was German and he was an American soldier. “We were waiting to take them both back to Germany and sprinkle their ashes there.” ●

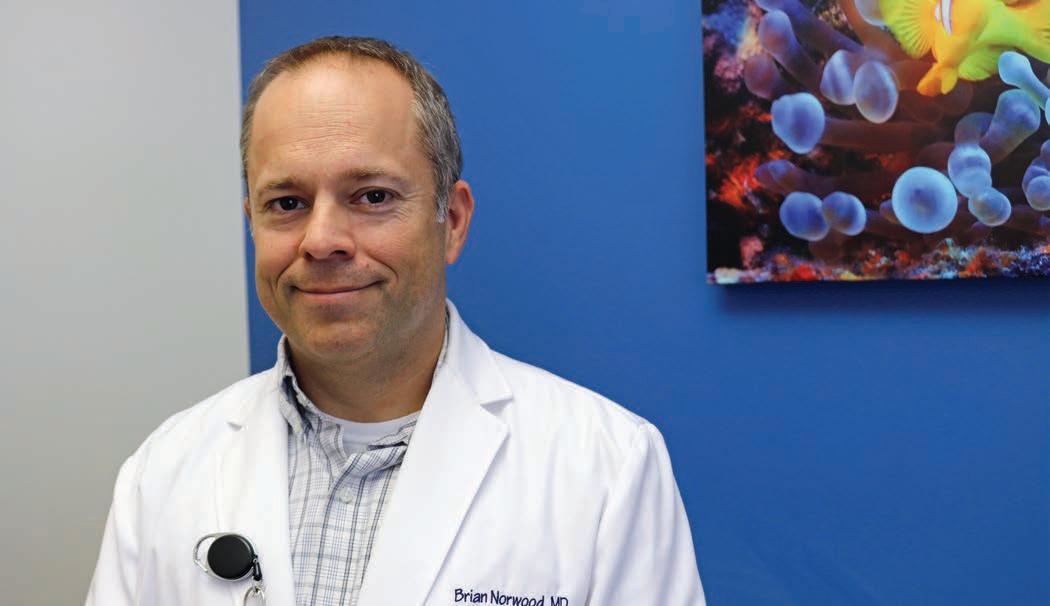

“Our goal is to increase physician/ nurse collaboration by helping medical students understand the role of nursing and the skills that nurses bring to healthcare,” says Cecilia McVey, MHA, RN, FAAN, associate director of nursing and patient care services at VA Boston Healthcare.

VA Vascular Access Nurse Kassidy Dias, RN, gently taps her forefinger on the blue vein in the arm of Vietnam War Army Veteran David Preston.

“Feel the bounce? That’s perfect,” Dias tells second-year medical student Juan Guerrero as he prepares to draw blood from Preston, a former sergeant in the 101st Airborne.

Guerrero is one of five second-year medical students from BU, along with a student from Harvard and another from Tulane, working on wards at the West Roxbury VA Medical Center, training in an innovative program known as The Other Side of the Bed. The six-week summer program, which began in 2009, has medical students undertaking many of the routine patient care tasks typically performed by the nursing staff.

“Our goal is to increase physician/nurse collaboration by helping medical students

understand the role of nursing and the skills that nurses bring to healthcare,” says Cecilia McVey, MHA, RN, FAAN, associate director of nursing and patient care services at VA Boston Healthcare System. She estimates that more than 200 medical students have participated over the past 15 years.

The program addresses what numerous studies have found: that an uneven power dynamic and issues around professional respect between doctors and nurses hinder collaboration, teamwork, and patient care.

VA Boston Chief of Staff Michael Charness, MD, believes the increased use of technology has exacerbated the problem.

“I think that as healthcare and medical education have evolved it’s harder for the different members of the team to understand and appreciate the skills each profession brings. And I think patient care can suffer from insufficient collaboration and communication,” says Charness.

Innovative program helps medical students understand the vital collaboration and communication between physicians and nurses

“I watch physicians as they are coming in for an hour, a half-hour, sometimes less, talking to patients, but there is a big difference being on the floor and being with patients the whole time,” says second-year medical student Rachel Kim.

Kim says nurses are continually asked to expand their responsibilities. On one of her first days on the ward, she watched a nurse juggle her patient load while taking time to accompany a veteran desperate for a walk, but who was a fall risk navigating with a walker while trailing an IV pole.

When a patient rapidly deteriorated and prognosis went from recovery to palliative care, Kim noticed nurses making careful observations of the changes. Although unconscious, the patient appeared to be experiencing pain. When the resident came on to the ward, Kim noted that he first turned to the nursing staff to ask what they had observed and what they thought should be done.

“One thing that really surprised me is how quickly you can make a valuable connection with a patient,” says second-year med student Douglass Bryant. “They are more than just their medical problems. They matter to so many other people and that’s all the more reason to do a great and respectful job.”

“It was the first time I saw one of the physicians take the time to get the full story from the nurses,” says Kim. “I saw that, and I said ‘okay, this is what I want to keep with me and emulate as I move forward in my training.’”

Studies also found that increasing reliance on technology, even just entering patient information and observations into a laptop, estranged physicians from patients. Students in The Other Side of the Bed said it was the opportunity to work directly and intensively with patients that drew them to the program.

“One thing that really surprised me is how quickly you can make a valuable connection with a patient,” says second-year med student Douglass Bryant. “They are more than just their medical problems. They matter to so many other people and that’s all the more reason to do a great and respectful job.”

“Throughout my first year [in medical school], I was afraid of having too much physical contact [with patients], too afraid of invading their privacy. It’s a hard line to walk, in how to provide hands-on care while still respecting their privacy and sense of personhood,” says Kim.

Working alongside nursing assistants (NAs) and nurses for eight- and sometimes 12-hour shifts, the medical students perform the most basic, but vital, tasks: bathroom assists, help with feeding and testing, and responding to call lights. Students shadow and learn skills from various teams, including vascular access, EKG, and respiratory therapy. There are weekly lunchtime lectures by a physician or researcher from the VA or BU.

Like most of the students, Guer rero was drawn to the intensive hands-on care experience, but found the reality of that work challenging.

“I thought I knew what I was getting into, but this was a lot more difficult; changing a patient for the first time, understanding how to move around a catheter, dealing with someone who feels really betrayed by the system and not knowing how to get through to them,” he says Sometimes, it’s the small details of care

that make patients’ lives in the hospital more bearable. Glucose testing is a daily ritual on many wards, and it involves pricking the patient’s finger with a needle to raise a drop of blood. No painkiller is used for this test and Kim found herself massaging patients’ hands to warm them and get the blood flowing.

“Throughout my first year [in medical school], I was afraid of having too much physical contact [with patients], too afraid of invading their privacy. It’s a hard line to walk, in how to provide hands-on care while still respecting their privacy and sense of personhood,” says Kim. “I learned a lot from [nurses] about how to do these really intimate tasks with dignity.”

Success is measured in achievements most people take for granted and patients provide life lessons that are humbling to students accustomed to accolades and success. When a patient started sharing his ignored

requests, Guerrero jumped in to express his sympathy, only to be rebuffed.

“He was very clear that he just wanted to be listened to. He didn’t want to be fixed; he wanted me to bear witness to his suffering,” says Guerrero.

Second-year medical student Jackson Wallner thought the most underrated aspect of the program was the opportunity to talk with patients and not feel rushed to move on to something else, a luxury he expects they won’t have as a physician. It’s why he knew that a shave was important to retired Army drill sergeant Robert “Rick” James. It’s a remedy that won’t be found in a medical textbook or that he’ll be expected to do on his future clinical rotations and residency, but Wallner grabbed shaving gear and fulfilled James’s request.

“He’s going to make a good doctor. He’s got the heart,” says James, a Vietnam War veteran. ●

Valeda Britton, BUMC executive director of community relations, presents one of 17 microscopes donated to New Mission High School to Head of School Will Thomas (Sargent’97, Wheelock’04) and his dedicated staff.

The Medical Campus recently donated 50 lab-quality micros copes to three schools in the Boston Public School (BPS) system.

The John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science in Roxbury, Dearborn STEM Academy in Roxbury, and New Mission High School in Hyde Park received Olympus CH series microscopes that were once used by Boston University Medical Campus (BUMC) students.

“This was a magnificent gift. We had the microscopes and the carrying cases, and the microscopes are in wonderful condition,” says Valeda Britton, BUMC executive director of community relations.

These 1970s-era Olympus CH series microscopes last a long time, but technology upgrades eclipse even the best performers eventually. Approximately a decade ago, the medical school and campus transitioned to virtual online microscope programs for teaching purposes. Eventually, the microscopes were placed in storage, with space limitations prompting plans to donate them.

“They were used less and less,” says Lucy Milne, director of education media. “Erita

Ikonomi, an educational technologist, maintained the scopes and kept them safe so they can now have a second life.”

The Medical Campus’s history of supporting Boston Public Schools includes establishing grants and other financial programs, offering the expertise of BUMC students and faculty, and donating excess equipment. BU also has specific initiatives—like the Summer Biomedical Research Internship and the Med-Science Program—that introduce underrepresented youth from Boston and other communities to postsecondary STEM-M (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine) programs.

As Medical Campus liaison to the surrounding communities, Britton and her colleagues visited the schools in advance of the donation.

“We casually brought up that we had these microscopes, and asked if they could use them in their science classes. And all three schools said yes,” she recalls. Within a few days, the 50 microscopes were loaded into a BU truck and driven to the schools, with two receiving 17 instruments and the third 16.

“The folks at the schools met us and they were really grateful to have these microscopes. I like the idea of those microscopes leading students to be more curious and more willing to explore,” Britton says.

“We said yes,” says Samuel Baker, an instructional coach at Dearborn STEM Academy focused on STEM and interdisciplinary pathways in health sciences, engineering, and advanced manufacturing and computer science. “The microscopes are of such good quality and very durable. They can take the wear and tear.”

In 2018, Dearborn moved into a brandnew, $70 million state-of-the-art STEM facility. Baker says the four-story school has microscopes in a lab on the second floor that had to be transported up to the biology lab floor when needed; the 16 Olympus microscopes allows them to have instruments in both labs.

Baker cites another benefit of institutions of higher learning interacting with BPS students—whether it’s university staff, faculty, or students who come to the high schools, they give students there the opportunity to broaden their everyday experiences by interacting with them. Dearborn’s student population is 90% African American, with many Cape Verdean families. Often, English is their second or even third language. “Students need to hear the college language, whether it’s a four-year or two-year college. We need to expose them to opportunities after high school,” he says. ●

Clinical Associate Professor of Anesthesiology

Robert J. Canelli, MD, has received the 2024 Leonard Tow Humanism in Medicine Award from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation. This award is presented to faculty who best demonstrate the foundation’s ideals of clinical excellence as well as outstanding compassion in the delivery of care and respect for patients, their families, and healthcare colleagues.

An anesthesiologist and intensivist at Boston Medical Center (BMC), Canelli demonstrates remarkable empathy for patients and their families, says a colleague. “His compassion is present in the perioperative arena, where Canelli strives to make his patients feel at ease prior to surgery. It extends into his practice in the intensive care unit, where he strives to care for critically ill patients and their families at their most vulnerable time. Canelli’s clinical expertise coupled with his caring bedside manner are an asset to BMC as he delivers high-quality anesthetic and intensive care to our most at-risk patients.”

Another colleague says Canelli not only excels as a clinician, working conscientiously and meticulously on behalf of patients in a wide range of clinical settings, but also as an enthusiastically involved educator who teaches and mentors medical students, residents, and junior faculty. “He is a role model who shows respect for everyone. As an accomplished academic clinician, he is constantly immersed in elucidating complex diagnoses and ethical dilemmas, always guiding trainees towards

the best management strategies for critically ill patients.”

Dedicated to fostering the next generation of physicians and healthcare providers, Canelli has developed a systems-based simulation curriculum for anesthesia trainees and introduced a point-of-care ultrasound initiative to teach this skill to medical students, residents, nurse practitioners, and fellows. “Not only is Dr. Canelli regularly going out of his way to teach trainees at the individual level, but he has also created an environment that allows and encourages them to gain knowledge in the use of ultrasound for the evaluation of cardiac, pulmonary, and gastric abnormalities,” says a colleague.

Canelli received his BS in chemistry from Villanova University and MD from St. George’s University School of Medicine. He completed his residency at the University of Massachusetts, UMass Memorial Medical Center, where he served as chief resident, and a fellowship in critical care from Harvard University, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Ricardo Cruz, MD, MPH, MA, assistant professor of medicine (pictured), and Shamaila Khan, PhD, clinical associate professor of psychiatry, have each received the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Accessibility (DEIA) of the Year Award. The annual award recognizes faculty and staff who have done extraordinary work addressing and improving diversity and a culture of inclusion, equity, and accessibility throughout the school community.

Since joining the faculty in 2014, Cruz has focused his clinical work at Boston Medical Center (BMC) on primary care and treatment

of substance use disorders for vulnerable populations, including racial and ethnic minority communities and individuals with a history of criminal justice involvement. He is also a physician in the Faster Paths to Treatment clinic, BMC’s innovative, low-barrier, substance use disorder bridge clinic.

His research interests include clinical innovations to address health and treatment disparities among people with substance use disorder. He was the principal investigator of the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health–funded Project RECOVER (Referral, Engagement, Coaching, Overdose preVention Education in Recovery), which utilizes peer recovery coaches to assist in the engagement and retention of individuals with opioid use disorder into treatment and primary care services after completion of acute treatment services (detoxification). He also served as coinvestigator on National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and National Institute on Drug Abuse–funded randomized clinical trials testing medications for alcohol and cocaine use disorders.

According to a nominator and colleague, “Dr. Cruz is a committed advocate for DEIA not only as a primary care clinician and addiction medicine specialist in the section of general internal medicine, but also as an educator and innovator of programs addressing health inequities. He provides exceptional care to Boston’s most underserved groups, many of whom face barriers to obtaining equitable healthcare.”

According to another, Cruz educates medical students and residents on the health impact and inequities driven by the criminal justice system: “Dr. Cruz is known as an excellent clinical teacher. His educational scholarship is deeply tied to the values of antiracism.”

A licensed clinical psychologist with a psychodynamic background and an interest in postcolonial theory, Khan’s clinical, academic, and research experience encompasses trauma and disaster relief work focused on

multiculturalism, decolonizing, and social justice. She treats those with individual trauma, community-based trauma, and immigration, racial, and postcolonial trauma. She travels globally to provide culturally significant disaster-relief services.

Khan also heads the Center for Multicultural Training in Psychology and the Center for Multicultural Mental Health and previously directed the Haiti SERG Program and served as clinical director of the Resilience Training Program at BMC. She was the first responder and director of behavioral health services at BMC’s Massachusetts Resiliency Center, serving the victims/survivors of the Boston Marathon bombings and led the Family Support Center, providing services to those impacted by the pandemic.

Khan is a member of both the Multicultural Concerns and the Professional Issues Committees of the American Psychological Association (APA) Division of Psychoanalysis, and the APA’s Committee on Accreditation multicultural expert and site visitor. She also serves on the Disaster Behavioral Health Advisory Committee of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and is cochair for the DEI Committee and diversity champion for the department of psychiatry.

“Dr. Khan embodies what this award is meant to honor. I can think of no one at the Medical Campus who is more deeply engaged in promoting diversity among students, trainees, staff, and faculty—and who is more deserving of this recognition,” said a nominator.

According to another colleague, Khan creates and implements programs designed to improve DEIA—including pathway programs such as the Black Lives Matter Training series— and has led a range of affinity groups, listening sessions, and healing circles at the Medical Campus and in the Boston community. “These efforts have made meaningful impacts as healing spaces related to the Boston Marathon bombing, COVID pandemic, George Floyd inci-

dent, anti-Asian hate incidents, LGBTQI hate crimes, and, most recently, in relation to Israeli/ Palestinian world events.”

Five Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine faculty have been honored as 2024 Educators of the Year by the school’s Awards Committee. The annual awards recognize Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine educators who demonstrate excellence in teaching and mentoring. Nominated by students and faculty, this year’s recipients are Molly Cohen-Osher, MD, MMedEd, Educator of the Year, Preclerkship; Christine Cary Cheston, MD, Educator of the Year, Clerkship; William Lehman, PhD, Educator of the Year, MA/MS Programs; Jeffrey L. Browning, PhD, Educator of the Year, PhD Programs; and Vanessa Villamarin, MD, Resident Educator of the Year.

Cohen-Osher is the assistant dean of medical education for curriculum and instructional design. Cohen-Osher joined BU in 2012 as the associate clerkship director of family medicine and assistant professor of family medicine. She completed a seven-year BA/MD program at Rutgers University/University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and did her internship in family medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, residency in family medicine at the MacNeal Family Medicine Residency Program in Berwyn, Illinois, and a master teacher fellowship at the Tufts University Family Medicine Residency

Program at Cambridge Health Alliance. She received her master’s in medical education at University of Dundee, Scotland.

Cohen-Osher focuses on creating learning experiences that foster active learning, teamwork, and the skills to build meaningful therapeutic alliances with patients, and supports faculty in implementing new instructional methods and curriculum.

According to a nominator, “Molly has been a model of professional behavior, dealing with students and faculty in a caring and compassionate way. She is an active listener and willing to make changes in response to feedback while holding fast to her principles as an educator. She is a superb role model for all educators at our institution. I cannot think of anyone more deserving.”

Cheston is an associate professor of pediatrics in hospital and newborn medicine and program director of the Boston Combined Residency Program (BCRP) at Boston Medical Center (BMC). Cheston received her undergraduate degree at the University of Virginia and her MD at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. She completed her pediatric residency in the Urban Health and Advocacy Track of the BCRP and received the Harvard Medical Student Teaching Award as a senior resident. She served as BMC chief resident prior to joining the faculty and in 2022, became an inaugural graduate of the BU Clinician Educator Leadership Program.

A student nominator cites Cheston as a model physician/educator who embodies a commitment to student growth, mentorship, and antiracism. “Dr. Cheston models compassionate, patient-centered care during rounds. She consistently prioritizes patient needs by requesting in-person interpreters,

finding chairs or squatting to maintain eyelevel communication, and offering nonjudgmental language suggestions to center the patient and minimize stigma. Moreover, Dr. Cheston empowers students to lead discussions and challenges our thought process to mitigate anchoring bias by asking for wide differential diagnoses and explanations for patient assessments based on their current clinical picture.”

Lehman is professor and vice chair of the Department of Pharmacology, Physiology & Biophysics and previously served as chair ad interim of physiology & biophysics. His research focuses on characterizing the role played by muscle thin filaments in regulating cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle contractility using a structural approach that combines molecular biology, cryoelectron microscopy, image processing, and computational tools such as molecular dynamics. His laboratory was the first to directly visualize and identify components of cardiac and skeletal muscle actin-containing thin filaments that respond to calcium and, in turn, control muscle activity. His molecular models of thin filaments provide a framework for investigating disease-bearing mutations leading to cardiomyopathies, and for drug discovery to counteract disease development.

Lehman received his BS from Stony Brook University, New York, and his PhD from Princeton. He spent three years as a postdoctoral fellow at Brandeis University and an additional year as a higher scientific officer at Oxford University before assuming his faculty position at BU in 1973.

“Dr. Lehman is a first-class professor who is immensely passionate about the education of his students and their success within the

healthcare field. His outstanding leadership has made each of his students exceptionally competent and knowledgeable, and we are extremely thankful to have had him guide us through such a challenging yet rewarding course,” said a nominator.

Browning received his PhD in biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin. He did postdoctoral work with Joachim Seelig, PhD, in the biophysics department of the University of Basel, using nuclear magnetic resonance methods to study membrane structure; and with Louis Reichardt, PhD, in the neurobiology department at the University of California-San Francisco, researching the neuromuscular junction. Beginning in 1984, for 28 years he was a research scientist in the immunobiology discovery group at the biotech firm Biogen in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His research interests center on the tumor necrosis factor family of regulatory molecules—notably the discovery of the lymphotoxin, BAFF, and TWEAK systems—and translation of modulators of the lymphotoxin pathway to the clinic in indications ranging from autoimmune disease and inflammatory bowel disease to oncology. A research professor in the Department of Virology, Immunology & Microbiology and the section of rheumatology since 2013, his current research focuses on altered vascular and stromal states in the perivascular compartment in the skin of systemic sclerosis and lupus patients, and their impact on the pathology.

One of his nominators said, “Jeff is a dedicated educator who is passionate about immunology and its role in health and disease, and who consistently strives to impart his vast knowledge and excitement for immunology to students. He pays a great deal of attention to each student’s research

and provides insightful comments as well as providing students with relevant papers and avenues for consideration. Importantly, he does not shy away from demanding the best of students but works hard to help them meet a high bar.”

Villamarin is a rising obstetrics & gynecology fourth-year resident at Boston Medical Center (BMC). Born in the Bronx, New York, Villamarin spent most of her early childhood in Ecuador before moving to central Massachusetts. After completing her BS in psychology on the neuroscience track at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, she worked as the lead research coordinator for clinical postpartum depression studies at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, where she earned her medical degree and was a student leader for the Worcester Healthy Baby Collaborative, working to address racial disparities in infant mortality. She also served on the executive board of the Latino Medical Student Association and Student National Medical Association chapters at UMass Chan.

Villamarin is passionate about social justice, equity in healthcare, and increasing diversity in medicine. According to a nominator, “She saw firsthand how dedicated BMC is to advocating for and providing equitable and excellent care to underserved communities when her mom received care at BMC as an uninsured patient.”

Her nominators describe her as kind, empathetic, and generous to students with her time. One said, “From day one, she was approachable and vested in my success. She always encouraged me to ask clarifying questions on rounds and in the OR, and shared constructive feedback in a way that encouraged my growth. Additionally, she taught me

how to approach challenging conversations with patients and the importance of always practicing shared decision-making. Her patients’ trust in her was palpable.”

Assistant Professor of Family Medicine Cheryl A. McSweeney, MD, MPH, has received the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine’s highest teaching honor, the Stanley L. Robbins Award for Excellence in Teaching.

Established in recognition of the exceptional teaching and devotion to students exemplified by Stanley L. Robbins, MD, former professor and chair of pathology, the annual award recognizes an outstanding educator who represents the importance of teaching skills and demonstrates commitment to students and education.

McSweeney is director of the Learn, Experience, Advocate, Discover and Serve (LEADS) course, launched in 2022 to equip medical students with the skills necessary to recognize and engage with the social drivers of health. In LEADS, students examine the structures and systems that have resulted in health inequities both currently and historically, explore their roles as physician advocates for justice in service to others, and develop pragmatic skills to advance health equity.

“LEADS is a complex course, and similar to other brand-new courses, it has required constant evolution and refinement. Yet, somehow, Dr. McSweeney has found a way to maintain a calm and cheerful demeanor in leading our team and the course. Whether providing feedback to a draft of a self-learning guide or leading a workshop for students on advocacy skills, Dr. McSweeney’s dedication to LEADS, our team, and the students is constant and evident. She fills every gap

and ensures every detail is accounted for thoughtfully and intentionally,” said a colleague in recommendation.

“Cheryl is patient, thoughtful, and kind in everything she does. While the LEADS curriculum provided multiple challenges around logistics, moving parts, and clarity on goals since inception, Cheryl has been able to take every challenge presented and work with individuals in an open, kind, nonjudgmental manner. She never presented herself as all-knowing but as inclusive, open to suggestions, flexible, and accommodating to change. Cheryl was committed to creating a road map that was visible and usable for everyone, despite constant pivots. She embodies servant leadership at the highest level,” said another colleague.

Multiple faculty members noted that McSweeney helped orient and mentor them when they were new. “She fosters a culture of collaboration and continuous improvement. Furthermore, she empowers the faculty and administrative team to innovate. She considerately approaches new ideas, strengthening them and helping support their success. She thus creates space for faculty to develop unique didactics focused on health equity,” one said.

Another colleague noted that McSweeney is a vocal advocate for diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging in the curriculum, saying, “She encourages our team to ensure that the students learn from an incredibly diverse set of speakers and that every learning objective promotes health equity. She values differences of opinion on our teams and seeks to provide a safe environment for students and faculty to express their challenges and frustrations.”

McSweeney’s outpatient family medicine practice is located in the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center, where she provides primary care to families and teaches third-year medical students.

Student evaluations describe her as “very engaging and knowledgeable”; “easy to get ahold of for questions and discussion”; “clear and passionate about equity and learning”;

and also as a mentor who “creates a very kind and comfortable learning environment” and “challenges students to think critically and apply concepts in her teaching.”

McSweeney received her undergraduate degree in brain and cognitive sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and MD from The Ohio State University, followed by an MPH in maternal child health from Boston University School of Public Health in 2013. She completed her residency at the University of Massachusetts Family Health Center in Worcester, Massachusetts. ●

The BU endocrinologist and department of medicine chair will remain on the medical school faculty

“I look forward to hearing from my colleagues across the hospital to build on their ideas and expertise to meet the health and social challenges of the patients we serve.”

Anthony Hollenberg, a nationally renowned endocrinologist and physician-in-chief at Boston Medical Center (BMC), as well as the chair of the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine department of medicine, has been named the new president of BMC, Boston University’s primary teaching hospital and New England’s largest safety-net facility, serving disadvantaged patients.

Effective June 3, the appointment was made by BMC’s trustees, whose chair, Martha Samuelson, said that Hollenberg “will further cement our hospital and health system’s role as a national model in equitable care.”

BMC is one of six healthcare providers and plans in the Boston Medical Center Health System, which is creating a coordinated care system to give patients state-of-the-art treatments, while also conducting cutting-edge research.

“I’m truly honored to lead BMC and our world-class clinical, research, administrative, and operational team members as our health system reimagines the future of equitable, expert care for our patients and members,” Hollenberg says. “I look forward to hearing from my colleagues across the hospital to build on their ideas and expertise to meet the

health and social challenges of the patients we serve. Every role at the hospital is critical to helping our patients and communities thrive.”

A native of Toronto, Hollenberg is taking a newly created job as BMC’s president under the hospital’s restructuring as an integrated health system.

Hollenberg will remain a professor of medicine. BMC and the medical school will begin a search for both department of medicine chair and physician-in-chief.

Before joining BMC in 2022, Hollenberg chaired the department of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City and was physician-in-chief at New York Presbyterian/ Weill Cornell Medical Center.

“Dr. Hollenberg’s extensive leadership background at academic medical centers, demonstrated experience as a highly accomplished physician-researcher, and his long-standing commitment to clinical innovation and health equity make him ideal to drive BMC forward as a premier academic medical center,” says Alastair Bell, president and CEO of Boston Medical Center Health System.

“As our health system rewrites how to best deliver care to our patients and members,” Bell says, “Dr. Hollenberg will further advance systems of care to ensure BMC remains a strong, trusted, and sustainable organization.”

Hollenberg’s research and clinical practice focus on thyroid disorders. He studies how thyroid hormones govern metabolism, including body weight, and also researches thyroid gland development. He has published more than 100 studies and 30 book chapters and reviews.

A graduate of Harvard University, he earned a medical degree from the University of Calgary. He served his residency in internal medicine at Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, followed by a clinical and research fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Tony is an accomplished physicianscientist and leader in academic medicine,” says Karen Antman, dean of the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and provost of the Boston University Medical Campus. “He is deeply committed to clinical excellence and health equity. We wish him great success and look forward to collaborating with him in his new role.”●

Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, ScM, has accepted the position of director of the Framingham Center for Population and Prevention Science, principal investigator of the Framingham Heart Study, and chief of the section of preventive medicine within the department of medicine at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center, effective January 1, 2025.

Lloyd-Jones is the chair of preventive medicine and Eileen M. Foell Professor of Heart Research and professor of preventive medicine, medicine and pediatrics at Northwestern University. He previously served as senior associate dean for clinical and translational research and PI/director of the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences (NUCATS) Institute from 2012–20. Lloyd-Jones also served as the national president of the American Heart Association from 2021–22.

He received a BA from Swarthmore College, an MD from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and a master of science in epidemiology from Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. He completed a residency in internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and served as chief medical resident. Following a cardiology fellowship at MGH, he joined the staff as an attending cardiologist and was an instructor and then assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and MGH. He joined the Framingham Heart Study as a research fellow in 1997 and was a research associate from 1999–2004. In 2004, he moved to Northwestern’s Feinberg School

of Medicine and became chair of preventive medicine in 2009.

Lloyd-Jones’ research interests include the study of the mechanisms and life course of cardiovascular health and healthy aging, and cardiovascular disease epidemiology, risk estimation and prevention. Other areas of interest include the use of novel biomarkers and imaging of subclinical atherosclerosis to improve prevention, and the epidemiology and outcomes of hypertension and dyslipidemia. His clinical and teaching interests lie in general cardiology with a focus on prevention.

He has been a national leader in public health and clinical approaches to promoting cardiovascular health and preventing cardiovascular diseases across the life course. He served as cochair of the Risk Assessment

Guidelines and a member of the Cholesterol Treatment Guidelines Panel for the 2013 ACC/ AHA Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction and was the lead member for risk assessment on the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines Panel and the 2019 Primary Prevention Guidelines Panel. He has authored over 750 peer-reviewed scientific publications and has been a PI or coinvestigator on more than 120 grants, the majority from NIH.

Lloyd-Jones has been named a “Highly Cited Researcher” by Clarivate Analytics in each of the last 10 years for being in the top 1% of cited authors in the field of clinical medicine, a distinction that includes only ~420 investigators worldwide.

The recipient of numerous awards and honors, he is a fellow of the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the American Society for Preventive Cardiology. ●

Also worked as part of a clinical team helping to treat injured athletes at the Summer Games.

As a basketball and tennis player of admittedly limited skills, Ali Guermazi, MD, PhD, MSc, would never be headed to the Olympics as an athlete. But as a radiologist and professor of radiology and medicine, Guermazi journeyed to his second Olympic games in eight years this summer when the Paris 2024 Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games named him codirector of radiology research for the Summer Games.

In the Olympic village from July 23 to August 12, Guermazi joined 32 radiologists and 36 radiographers, including Michel Crema, MD, an adjunct assistant professor of radiology at the school. For five of those days, he worked as a clinician, reading X-ray, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging for athletes injured during the games. For the rest of the Olympics, he directed the collection of injury data with the goal of producing 20 research papers that the Olympic committee hopes will provide insight into training, injury prevention, and treatment.

“It’s all about best practice,” says Guermazi of the research. “The goal is to give [athletes, trainers, and coaches] an idea of why it happened and how to prevent it the next time.”

One of the papers from the 2016 Rio Olympics detailed the damage to muscles, connective tissue, and bone wrought by competition at the highest level, with more than 1,100 injuries diagnosed for 11,274 athletes. BMX cycling, with 38 percent of the athletes injured, and boxing, with 30 percent, topped the list.

“Thirty percent of the athletes who participated in the Rio de Janeiro Olympics had arthritis and were very young. Those were probably posttraumatic [injuries],” says Guermazi.

As chief of radiology at the VA Boston Healthcare System, he sees some similarities between military veterans and athletes.

“Almost every veteran has posttraumatic osteoarthritis because they went to war…and they do things that are very stressful on the joints,” he said.

“We’re looking for treatment because at this point, there is no treatment.”

When injuries occur, the impact of a correct diagnosis and treatment of an injury play out in real time in the medical clinic. Not just muscles and bones are torn and shattered, but Olympic dreams as well. Whether the athlete enters the clinic accompanied by a coach or trainer, or with an entourage of a dozen people, as happens with the Olympic stars, the images reveal the toll of the pursuit of excellence.

“We can say to the athletes how long it’s probably going to be for them to return; if it’s five or six days and you can continue [competition], or if their Olympics are over,” says Guermazi, who has worked in sports medicine for 30 years. The 2015 book he coedited and helped author, Imaging in Sports-Specific Musculoskeletal Injuries, factored into his invitation to the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

These high-performing athletes are not typical people, Guermazi says, and their injuries are often way beyond what he sees in his sports medicine practice. But when they finally get to the Olympics after years of training, their drive to win is often stronger than their fear of injury.

“They want to win. For them, it has to be first, not second or third,” he says. “When they get injured, it’s really big. You see the images and sometimes you say, ‘Oh my God, what’s this?’ It’s kind of mind-blowing.”

Guermazi is impressed by the athletes’ resilience and their capacity to endure pain and even risk long-term disability to succeed. He cites a champion judo athlete who has almost no rotator cuff on one arm—the rotator cuff holds the shoulder joint in place and

Ali Guermazi (right), a radiologist and professor of radiology and medicine, was part of a team of radiologists treating injured athletes at the 2024 Paris Summer Olympics. He previously served at the 2016 Rio de

allows movement of the arm and shoulder, which would seem essential in a sport like judo—yet the athlete continued to compete and win despite what should have been a career-ending condition.

According to Guermazi, preventing osteoarthritis in both athletes and the general public is a tough task, but it’s vital to ensure the least amount of trauma and microtrauma.

“Exhausting your body is not going to be okay,” he says.

NBA players, for example, who play 82 games over a seven-month schedule— roughly, a game every two and a half days— have little time for recovery.