29 minute read

potentialities of an innovative traditionSustainability

Sustainability: potentialities of an innovative tradition

“In my world, this is a rubber duck. It comes in California with a warning: “This product contains chemicals normed by the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects to the reproductive tract.” This is a bird. What kind of culture would produce a product of this kind and then label it and sell it to children? I think we have a design problem.”

Advertisement

-W. McDonough, 2005-

(1) A. Corboz (1983), The land as a palimpsest, Ecole polytechnique fédérale, Zurich, september, https://doi. org/10.1177/039219218303112102 (2) R. Welford (1995), Environmental strategy and Sustainable Development I, Routledge, London (3) P. Samson (1995), The Concept of Sustainable Development, in mailto:gci@ unige.ch, Copyright & Copy, Green Cross International

(4) Leader of Suquamish and Duwamish who pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers in America.

(5) J. Robertson (1985), Future work: Jobs, self-employment and leisure after the industrial age, Gower/Maurice Temple Smith, Aldershot

(6) J. Watson (2020), in Indigenous technologies “could change the way we design cities” says environmentalist Julia Watson, Amy Frearson, 11th of February, www.dezeen.com Men had always to relate to their environment. Nevertheless, with the passing of time and the evolution of techniques, men lost sight of their connection to nature, leading progressively to the generation of an artifcial world, completely detached from the natural one. The situation of environmental crisis we are facing today asks men to rethink this relation, that needs to be urgently balanced. The building sector, due to its impacts on the environment, have a central role to lead and direct the change. . The relation men-environment: cohabitation or occupation?

Land has always been the result of a process, either natural or human. Since the beginning of time people has occupied and transformed it, either by flling or by extracting, with the aim to plan a logic in the apparently illogic of natural life cycles. Generally, lands in traditional civilisations, concerned not to disturb the order of the world and even desirous of helping to maintain it, were a living body of divine nature to whom cultic homage was paid (1). Humans embrace nature trying frst to understand it, through representation, (the ancient Lascaux caves are an example of this), and rationalisation, (as in the case of Stonehenge, with a passage from pure representation to invention). Land was (and it is still today) a project setting a collective relation between that topographic surface and the population who has to establish in. Ancient populations used to perceive themselves as part of a cosmic and cyclical order, fostering an idea of posterity that was not just referring to a future event, but also to the past. In this regard, an old Kenyan saying used to go: We didn’t inherit the Earth from our parents: we borrowed it from children (2), while Samson (3), reports how the idea of sustainable development has already been present into Sumerian, Mediterranean and Maya societies. In more recent times, James Robertson trusted chief Seattle (4) with this words: (…) Tis we know. All things are connected. Whatever befalls the Earth, befalls the son of the Earth. Man did not weave the web of life. He is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself. (5) Ways of living necessarely used to depend directly on the belonging context. Local materials or natural energy were employed worldwide before technological advancements in construction.

Sustainability wasn’t a choice but rather a fact, an unconscious way to be. An obligation that generated innovation as, for instance, the 12th Century Cambodian temple complex Angkor Wat, a rainwater irrigation system that collected water during monsoon season to farm rice during the drier months; or the Persian engineering windcatchers enabling natural ventilation. With the passing of time and the advancement of technology, men succeeded in redesigning landscapes in diferent ways, attuned to their needs, either modifying the topography of production or afecting the form of land. Te drainage interventions of 10th and 11th century on the Po River plain by Benedictines or the replacement of oaks with pines in central Europe are just two well-known examples. With the beginning of Renaissance, the role of nature changes though and a process of aesthetization begins, with a consequent sentiment of progressive detachment from it. For the frst time men were able to represent in an exact way their surrounding world thanks to the invention of perspective, starting somehow to “handle” it. Te epitaph of Rafaello is exemplar of this general mood, as it states: Da Lui la Natura temette di essere vinta (Nature feared to be by him overcame). Tis period of tireless innovation led to a constant question of what will come next, in a state of faithful belief in human abilities. Te transition from the previous mindset of nature as a threat, to humans as saviours of nature

instead, became even stronger over the age of Enlightenment (6). In this regard, over the last centuries of Ancient Regime two opposite ideas on the relation man had with his surrounding environment took shape. On one side, sciences started to consider nature as an mere object, which men can, and even must, exploit for their own proft (1); On the other, Romanticism began to consider it as a sort of pedagogue of the human soul (…) as a mystic being which carried on an unending dialogue with men, (…) as a subject (1). Both these visions, even if so diferent, were actually marking a further detachment. Nature was fnally perceived as something alien, either object or subject, diferent from the life cycle humanity belonged to. Te development of tourism in 19th century is way exemplar of this mindset. An extreme will of contemplation of the so-called sublime, a radical research for the panoramic, is the same that caused the construction of hotels, cog railways and steam boats. (…) the farther the view carries and the more panoramic it is, the more it satisfes the need to dominate by derisively opposing the individual to the planet’s mass. (1)

Progressively this mindset, transferred into the social economic reality of nascent liberalism, led to the overcoming of the concept of posterity in favour of immediate economic growth, defning the upcoming Industrial Revolution with its linear production chain. Industrialists, engineers, and designers started to try to solve problems taking immediate advantage from them, in a period they used to consider of unprecedented opportunities and of massive and rapid change. (7) At bottom Industrial Revolution was an economic revolution and it was based on the essential aim to get the greatest volume of goods to the largest number of people. Due to the really low level of awareness on its impact on nature, massive production wasn’t seen as something problematic, environmentally speaking. In fact, natural resources were still considered infnite and perpetually regenerative. Even Ralph Waldo Emerson, a prescient philosopher and poet with a careful eye for nature, used to describe it, still in the early 1830s, as an essence unchanged by man (8), refecting, in doing so, a common naive belief concerning the existence of wild nature just parallel to the crescent industrial development. Anyway, even if many people continued to believe that there would always be an innocent and untouched piece of natural land, the Western view was progressively harnessing the need to subdue nature, as a brutish and dangerous force to be civilised and controlled. Economy started to become the only

parameter to judge best effciency and humans’ well-being. It’s no coincidence, that from the 20th century till today, in a world mainly looking for proft, barely questioning the origins of the resources used to generate it, the main unit to measure the improvement of a nation has been the GDP (Gross Domestic Product). Diferently, in fact, from what Robert Kennedy declared in 1968 at the University of Kansas on the unsuitableness of GDP as a beneft indicator of the economically developed nations (9), a more and more stronger speculative capitalism has progressively led to its overestimation, in spite of other values that cannot be monetized. In this regard the Exxon Valdez oil spill, happened in 1991 on the costs of Alaska is particularly emblematic, as it paradoxically increased the country’s GDP. In fact, due to the large amount of people who went there trying to clean up the spill, restaurants, hotels, shops, gas stations, and stores all experienced an upward blip in economic exchange. Te GDP in fact takes into account as only measure of progress the economic activity. It’s a sort of odometer: its precision can be crucial but still it’s not capable to inform you about the direction to take. (10) In fact, what sensible person would call the efects of an oil spill progress? By the way, still most of the time GDP is the only leading criteria to take long-run political decisions, that consequently neglect the real needs of both environment and society, as they

(7) W. McDonough and M. Braungart (2009), Cradle to Cradle. Re-making the way we make things, Vintage Books, London

(8) R. W. Emerson (1836), Nature, in Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson, edited by S. E. Whicher, Boston: Houghton Miffin, 1957

(9) (The GDP) counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage (...) It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fght the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman’s rife and Speck’s knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=t6U2irFSYHo&feature=emb_title

(10) Amici della terra (1995), Verso un’Europa sostenibile, Maggioli Editore, Rimini

Man is inside an existing natural eco-system, that he tries to understand.

The concept of fast economic growth becomes stronger than the one of posterity.

The evolution of the relation between man and his environment.

(11) E. Tiezzi, N. Marchettini (1999), Che cos’è lo sviluppo sostenibile? Le basi scientifche della sostenibilità e i guasti del pensiero unico, Donzelli, Roma (12) E. Abbey (1977), The journey home. Some Words in the Defense of the American West, Penguin, 1991 (13) T. Malthus (1798), Population: The First Essay, University of Michigan press, Ann Arbor, 1959, p. 49 (14) E. Zencey (2010), Theses on Sustainability, in Orion Magazine, https:// orionmagazine.org/article/theses-onsustainability/. (15) Quoted in Max Oelshaeger (1992), The idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology, Yale University Press, New Haven, p. 217 Next page: Exxon Waldez, Photo: RGB Ventures/SuperStock/Alamy Stock Photo, 1989 Man becomes part of this eco-system. He makes use of available natural resources in a respectful way.

The Vitruvian Man and the emergence of the concept of human microcosm. are outside an individual preference system. (11) Finally, in the words of Edward Abbey: Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell (12) and it’s hence the time for sustainability to radically infuence and change our culture and society.

. A siècle of transition: from industry and society…

With the passing of time the awareness about the limit of available natural resources compared to our growing demography had progressively increased. Tomas Malthus frst, at the end of the 18th century, warned about the expected exponential growth of population and to its consequent devastating impacts on humankind: Te power of population is so superior to the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race (13). Anyway at that time, his voice remained quite isolated and unheeded, and he even became a cultural caricature due to his pessimistic position. In fact, for decades environmentalism would have been primarily a simple moral admonition, with principles susceptible to being reduced to fundamentalist absolutes. Environmentalists were just mourning the disappearance of natural wildness and time has long since passed for the achievement of sustainability to fnger-wagging in its various forms (14), through the condemnation of environmental pollution, a more active type of denunciation or just through creative thinking. Romantics as William Wordsworth (1770-1850) and William Blake (1757-1827) as well as Te American Environmental Movement, (even if ofcially started around the 1970s with the frst Earth Day, the movement grew its roots in the writings of 19th-century naturalists, as George Perkins Marsh and Henry David Toreau) on the other side of the world, were speaking out against the increasing mechanistic urban society, without having a real active program though. Leopold (1887-1948), who used to belong to this last group, especially anticipated some of the feelings of guilt that today characterise environmentalism when radically stated: When I submit these thoughts to a printing press, I am helping cut down the woods. When I pour cream in my cofee, I am helping to drain a marsh for cows to graze, and to exterminate the birds of Brazil. (…) when I father more than two children I am creating an insatiable need for more printing press, more cows, more cofee (…) (15). Over the 1960s and ‘70s environmentalism started assuming

a scientifc base and a more proactive approach.

In historic terms, the moon landing of 1969 and the possibility to look at our planet as a whole contributed to the gradual adoption of a global perspective (16). Moreover, some years later, the Arab oil embargo of 1973–1974 reinforced the idea of a globalised world as, for the frst time, an event happening on one side of the globe had a direct domino impact on economies of several, dislocated but still inter-dependant, nations. In that period, as a feld of inquiry, environmental history, the human history through an ecological lens (17), emerged out of the environmental movement. In this regard, Rachel Carson with her book Silent Spring, published in 1962, became a key fgure of active environmentalism, as she put the scientifc bases to the romantic strain of wilderness appreciation, pointing out how science could damage hugely environment (specifcally referring to pesticides such as DDT). Her words displayed an increasing consciousness of the environmental issue: Te control of Nature is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man. (18) Ten years later, in 1972, the Club of Rome with the publication of Te Limits to Growth, demonstrated what Malthus was just theorising around two centuries before, displaying for the frst time to the whole contemporary world the limited quantity of natural resources in respect to demographic growth. According to this report, if the rate of growth at that time, in terms of world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion, continued unchanged, resources would have been fnished in around one hundred years. (19). With Beyond the limits, published around 20 years later, Club of Rome passed from a descriptive to a critical approach, concluding with some general warnings aimed to mark a direction to avoid an irresponsible resources’ consumption: Minimise the use of nonrenewable resources. (…) Prevent the erosion of renewable resources. (…) Use all resources with maximum efciency. (…) Slow and eventually stop exponential growth of population and physical capital (20). Paradigms that still today one could refer to when speaking of Circular Economy and sustainability. 1972 is also the year of the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment, the frst Global meeting between nations about the theme. It marked the recognition of the interdependency between environment and human development and hence the impossibility to split environmental and social policies. In this regard, starting from 1979, the World Meteorological Organisation has settled several periodic international meetings about global climate issues in order to set the coordination between nations concerning environmental policies.

The publication of the Brundtland Report of 1987, also called Our Common Future, defnitely marked the meaning of sustainable development, which is the one that meets the need of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (21). Again, after centuries, concepts as posterity and circularity of resources were coming back. It was still a vision, though, that didn’t fnd an immediate application to the industrial sector. After decades of issuing urgent, in fact, industries were beginning to recognise causes for concern, but they were applying a strategy of reduction rather than a consistent modifcation of how to produce things.

Sustainability has always been related to the 3R’s: Reduce, Recycle, Reuse. Reduce and Recycling though have been the primary drivers of the debate on the topic over the last century. Notwithstanding, due to the nature of some materials that could go wasted or be

(16) T. Ingold (1993), The temporality of the landscape, published online: 15 Jul 2010, https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.19 93.9980235

(17) J. D. Hughes,(1975), Ecology in Ancient Civilizations, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press (18) R. Carson (1962), Primavera silenziosa, Feltrinelli, Milano, 2016

(19) D. and D. Meadows, Sanders (1972), The Limits to growth: A report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, Universe Press

(20) D. and D. Meadows, Sanders (1992), Beyond the Limits: Confronting Global Collapse, Envisioning a Sustainable Future, Chelsea Green Pub.

(21) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. https:// sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/ documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (22) R. Minunno, T. O’Gradya, G. M. Morrisona, R. L. Gruner, Exploring environmental benefts of reuse and recycle practices: A circular economy case study of a modular building, 16 May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. resconrec.2020.104855

(23) H. Bennetts, A. Radford, T. Williamson (2002), Understanding Sustainable Architecture, Taylor & Francis Group, Routledge, Abingdon (24) Quoted in (7) (25) C. De Wolf, E. Hoxha, C.Fivet, Comparison of environmental assessment methods when reusing building T components: A case study, 10 June 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102322 (26) C. Monticelli (2013), Life cycle design in architettura. Progetto valutazione di impatto ambientale dalla materia all’edifcio, Maggioli Editore contaminated and to the energy needed for their transformation or upgrade, (22), reductionism and recycling don’t halt depletion and destruction. Tey only slows them down, allowing them to take place in smaller increments over a longer period of time (7). At the contrary, a recent study (22) has fnally demonstrated how a strategy of reuse can ofset greenhouse gas emissions by 88% compared to reductionism.

Reuse and circularity, therefore, become crucial concepts in view of sustainability and ask for a complete rethinking of our society and industry. Sustainability in fact implies a circular notion of time, while development has always been connected, in the Western culture at least, to a continuous accumulation of capital, material, services, knowledge and of anything that is commodifed, implying, accordingly, a linear notion of time. (23). Nevertheless, even if in recent years industries started to be aware of their limits of production (Robert Shapiro in 1997 declared: What we thought was boundless has limits and we’re beginning to hit them), the industrial infrastructure is mostly still linear, focused on making a product and getting it to a customer quickly and cheaply, according to the extract-produce-dispose model (25). In this regard, 90% of US production, due to the overused concept of planned obsolescence, is programmed exactly to become trash at its “end of life”, as it had a fxed and unchangeable expiring date (26).

. … to architecture

Tese ecologic and economic crisis related to industrialisation had an impact also on the directions taken by the architectural development and research. Its development could be synthesised in four main phases that are strictly related to historical events of last century and anticipate the current approach based on principles of Circular Economy. Chronologically they are: Bioclimatic Architecture; Environmental Architecture; Sustainable Architecture; Resilient Architecture. Tis is not a fxed classifcations, but rather a way to set a mental grid to order the events and have an efective synthesis of the evolution of the concept in the construction feld over last century. In this regard, studying the built and planned environment in view of sustainability provides a way to reassess the very idea of an ‘artifcial’ built environment. Artefacts of architecture and infrastructure are perhaps the most pervasive evidence of men’s artifce. Historically, buildings and architecture had a central meaning to represent the relation of a society with it surrounding environment. Consequently, their reinscription within a natural history allows us to reassess this divide and, with it, a central paradox of our present moment: that we have constructed a natural world in the process of fabricating an artifcial one.

Bioclimatic Architecture, from the beginning of the 20st century till the ‘1950s, is generally characterised by the interest for natural surroundings and local climate, ensuring the efciency and conditions of thermal comfort for the building. Te ideas of Wright (1867-1959) on organic architecture, of Le Corbusier (1887-1965) and Breuer (1902-1981) on sun shading, of Atkinson (1883-1952) on hygiene are some examples of the frst developments of this phase. In the ‘20s, the concept further evolved thanks to Meyer (1889-1954) and to his Biological Model (1926), a design approach that used to consider the building as a biological event (Meyer, 1926). A few years later, in 1929, Neutra (1882-1970), who had been a pupil of Wright and had already stated in the past the faw of human products compared to nature, started to spread the concept of Bioregionalism: an infrastructure design that maximises the free-work that natural systems can provide (27). Finally in the ‘50s empirical research entered defnitely the architectural design. Tose are the

years when Buckminster Fuller developed the Anticipatory Design Science (1950), with the aim to compute the exact quantity of material and energy needed for the construction and use of certain structures, introducing the concept of lightness in architecture. In the same period, the Olgyay Brothers set up the frst architecture lab combining academic research and practice. Some years later, their book Design with Climate (1963) will become a stepping stone for an alternative modernism questioning the universality of a fossil fuel-dependent architecture. (28)

Te passage toward the second paradigm of Environmental Architecture, corresponding to the period between the ‘60s and the ‘90s, is characterised by a tendency of environment inclusiveness in architecture, from the building interior to the planning scale. In this period, environmentalism was starting to enter public consciousness and hence the criticism, or at least the questioning, of modernist architectural practices, that will defnitely collapse with the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe in 1972. McHarg (1920-2001) with his contribution on a regional planning approach that uses natural systems, is one of the main actors of this phase. His book Design with Nature (1963) had great popularity and not only changed design and planning, but also gain the attention of felds as diverse as geography and engineering, forestry and environmental ethics, soils science and ecology. At the architectural scale, the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy, also known as the Middle East’s father of sustainable architecture (29), leaded to the rediscovery and incorporation of traditional design and building materials, that can be easily be recycled or directly reused. He wrote: here, for years, for centuries, the peasant had been wisely and quietly exploiting the obvious building material, while we, with our modern school-learned ideas, never dreamed of using such a ludicrous substance as mud for so serious a creation as a house (30). Te ‘70s also marked the outcome of several organisation promoting a more sustainable way of constructing, consistently to the general pro-active approach that environmentalism started to adopt in these same years. In this regard, in America, the American Institute of Architecture (AIA) was promoting American public works to be a refection of the sensitivity toward environmental quality (Commission on Highway Beautifcation, 1972). Te American Solar Energy Society (ASES), instead, was, and still is today, a non-proft organization, funded in 1954 with the aim to share knowledge, advocating for sustainable living and 100% renewable energy (31). In Europe, the Passive and Low Energy Architecture (PLEA) society had a role in leading the debate and collecting new ideas about sustainable architecture, especially thanks to the conference they organised in Crete, Greece, of 1983. In this occasion, frst ideas of energy neutral buildings and renewable energy integrated systems were introduced in several building prototypes and concepts.

Te Brundtland report of 1987 marked the transition toward the period named Sustainable Architecture, lasting for around 10 years. Te concept of posterity entered building construction and hence the concept of biological and technical loops. In America, Samuel Mockbee (1944-2001) demystifed Modern Architecture, combining its forms and angles to a context-belonging approach, that look for the reduction of transformation processes and transports’ shortenings rather than universality. (32) Tis period is also characterised by the research for new empirical simulation and measuring methods to quantify buildings’ performance in terms of sustainability. Te idea was to establish a holistic rating that goes beyond aggregating individual components of the project (33).

(27) C. J. Kibert, J. Sendzimir and G. B. Guy (2001), Construction ecology: nature as the basis for green buildings, Spon Press, London

(28) V. Baweja (2014), Sustainability and the architectural history survey, Enquiry. An open access journal for architectural research, vol. 11, issue 1

(29) T. Laylin (2010), Hassan Fathy is The Middle East’s Father of Sustainable Architecture in Cities, February 26 (30) H. Fathy (1973), Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London

(31) https://ases.org

(32) samuelmockbee.net (33) G. Gylling in K. G. Jensen and H. Birgisdottir (2018) (edited by), Guide to Sustainable Building Certifcations, Realdania and The Dreyer Foundation (34) S. Attia (2018), Regenerative and Positive Impact Architecture. Learning from Case Studies, Springer, Cham Te US Green Building Council of 1993, founded to promote sustainability in the way buildings are designed, built, and operated will fnally defne the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system. It was the frst method to compute the level of sustainability of a building based on factors like surroundings, emissions, toxicity, performance efciency, water and energy use. Meanwhile in Europe the concept of Passive House was progressively emerging, based on the considerations of excellent insulation, prevention of thermal bridges, airtightness, insulated glazing and controlled ventilation, already required in Denmark and Sweden for low energy buildings. Its inventors were Bo Adamson (1925-) and Wolfgang Feist, who defned Passive House as buildings which have an extremely small heating energy demand even in the colder climates and therefore need no active heating. Tis kind of houses could be kept warm passively, solely by using the existing internal heat sources and solar energy entering through the windows as well as by the minimal heating of incoming fresh air. Te theoretical proof for the feasibility of such houses was fnally provided in the thesis Passive Houses in Central Europe by Feist in 1993.

Just a few years later, the frst international agreement to stop global warming, the Kyoto Protocol, of 1997, marked furthermore the need for Resilient Architecture. In this regard, the work of Bill Dunster (1960-) and of his studio Zedfactory on Zero Energy Development and Ed Mazria (1940-) on the 2030 Challenge had a strong impact on architectural research and practice.

Notwithstanding, till the end of last century, consistently to what was also happening into the industrial sector, all these paradigms have been based on an existing strategy of reductionism

rather than proposing innovative approaches and technologies aimed at the complete elimination of wastes. Moreover, until the start of the 21st century, promoting sustainable architecture and green building concepts was actually a specialist niche issue, a storm in a glass of water in the margin of a linear economic mass production. (34) Nevertheless, sustainable architecture can play a key role for the sustainable development of society as a whole, as cities can potentially be a testing ground for models of the ecological and economic renewal of the society. (34) In this regard, cities shall be conceived as histories of ecosystems, due to their set of ecological relationships. (17) Now especially the built environment plays a vital role in the global economy and can be an engine for sustainable innovation and growth. Accelerating the ongoing transition from a linear to Circular Economy in the construction sector can vastly increase this potential.

. What is Circular Economy and the concept of Regenerative Architecture

Terefore, in industry as well as in construction and society in general the question is still the same: You wouldn’t want to depend on savings for all of your daily expenditures, so why rely on savings to meet all of humanity’s energy needs? (7) Today, a number of globally branded companies are seeking to develop and transform their business models in view of Circular Economy, in order to be able to exploit the opportunities of this type of approach and hence to increase signifcantly resource productivity (35). Te business model of Circular Economy is one of the most recent proposals to address

environmental sustainability. It stands in contrast to the traditional linear economic model, by addressing at the same time economic growth and shortage of raw materials and energy. It is a production and consumption process based on the preservation of components

and materials within closed loops of production of either biological or technical nutrients and it has the aim to achieve resource effciency by keeping their added value throughout all stages of the value chain. Te size of each loop especially depends on the quantity of transformations a certain product will need before being valuable and reusable again: the smaller the loop is, less transformations the component will need. Product value, instead, depends on the overall value chain structure identifying processes of material reuse, as transportation distances, site conditions and quantities of materials. Tus it’s clear that the more processes and material inputs are required by a reuse product, the less likely it is to become pricecompetitive through potential cost savings from lower-priced secondary materials (36).

Circular Economy now forces its way into architecture and urbanism as well. And with good reason: 40% of the demand for energy in the European Union is consumed by the building industry (37) and, according to estimates, a staggering 60% of all waste is the result of construction and demolition. Te great signifcance of buildings and dwellings is evident in the way the building sector occupies in national economies. Private households spend roughly one third of their disposable income on housing (38), while in Western Europe, 75% of fxed assets are invested in real estate (39). Data are again disconcerting: urban sprawl has already caused severe environmental damages as we’re developing land, the scarcest resource on earth according to the European Union Directive, at a speed that the earth cannot compensate. Resources (land, water, energy, materials and air) we need to provide for decent housing and high quality life in the built environment are in decline because they are being used, exhausted or damaged faster than nature can regenerate them. (34) According to Global Footprint Network, the accelerated impact of climate change and the increasing negative impact of the built environment are exceeding the planets capacity by almost two times.

In addition, United Nations recently stated that cities are responsible for the 70% in the global energy demand and that their relevance is expected to increase, in step with the urban

population (40). Our demand is growing: by 2050 people on Earth shall around 10 billion and 80% of them is expected to be urbanised. Tis fact urgently ask to re-think our city and to fnd new solutions to provide afordable and sustainable housing. In this regard, today half of the population of many cities live in illegal settlements without access

to basic services (41). Forecasts state that within little more than a decade, a third of urban dwellers, 1.6 billion people, could struggle to secure decent housing (42). Currently, moreover, the afordable housing gap, that is the diference between the cost of an acceptable standard housing unit, which varies by location, and what households can aford to pay using no more than 30% of income, stands at $650 billion a year and the problem will only grow as urban populations expand. In terms of numbers, this means that by 2025 1 billion houses are needed worldwide. (43). Tus, the demand side asks for new policies able to combine economic and social aspect (the ageing of population, the increasing of number of families, the increasing of social and economic vulnerable categories, the in- creasing number of migrants), facilitating housing access (44). However, meeting this demand through current linear construction and housing practices requires an investment of around $9–11 trillion overall and have signifcant negative environmental impacts, such as the impacts from extraction that are felt locally as well as globally.

Therefore, integrating circular economy principles into all the phases of a building’s cycle could work to meet urban needs for built space, while staying within planetary boundaries.

(35) GXN Innovation (2019), Building a Circular Future. 3rd Edition, originally published in 2016 with support from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (36) Nußholz, Rasmussen, Whalen, & Plepys (2020), Material reuse in buildings: Implications of a circular business model for sustainable value creation, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118546 (37) P. Huovila (2007), Buildings and Climate Change: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities, United Nations Environment Programme (38) Eurostat (2012) Housing cost overburden rate by tenure status. Eurostat (39) Serrano C, Martin H (2009), Global securitized realestate benchmarks and performance, J Real Estate Portfolio Manage (40) K. Milhahn (2019), Cities: a ‘cause of and solution to’ climate change, in UN News, 18 September (41) D. Satterthwaite, D. Archer, S. Colenbrander, D. Dodman,J. Hardoy,D. Mitlin, S. Patel (2020), Building Resilience to Climate Change in Informal Settlements, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.02.002 (42) J. Woetzel, S. Ram, J. Mischke, N. Garemo and S. Sankhe (2014), Tackling the world’s affordable housing challenge, McKinsey Global Institute, 1st October (43) McKinsey Center for Business and Environment, J. Woetzel, S. Ram, J. Mischke, N. Garemo, S. Sankhe (edited by) (2014), A blueprint for addressing the global affordable housing challenge, October

(44) V. Gianfrate, C. Piccardo, D. Longo, A. Giachetta (2017), Rethinking social housing: Behavioural patterns and technological innovations, http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.05.015

Cradle to grave

Reductionism

Cradle to cradle

Different strategies of production.

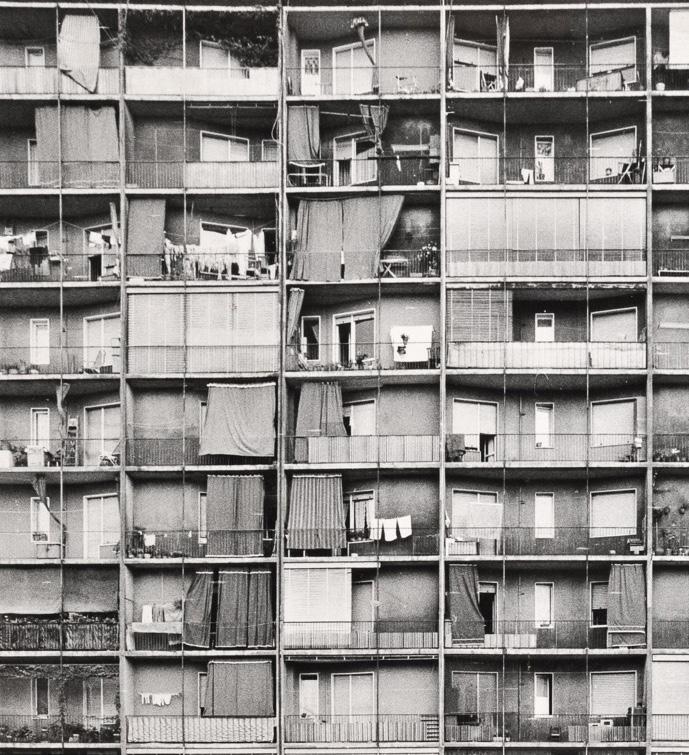

Next page, right: Milano - Quarto Oggiaro. Porzione della facciata di un edifcio di edilizia popolare. Photo: G. Basilico, 1970-1973. Next page, left: Residential house in Hong Kong. Photo:A. Shimmeck, 2019. In this regard, Social Housing can have a role in the development of social enterprises and as an opportunity to face this new incremental housing demand and hence new living models, enlarging the entrance to the housing market and with the identifcation of new fnancial and funding models, fostering new partnerships’ between public and private sectors, as further explained in the fourth chapter. Covid-19 puts an additional strain to the research for building a liveable, afordable and sustainable alternative, as when households and communities have most of the essential features, it’s easier to address COVID-19 at scale. According to Satterthwaite, still today many minimise health, social and economic costs and make self-isolation and achieving high-quality hygiene much easier (41).

Future challenges ask thus more research on crucial topics as Circular Economy in the construction sector and quality affordable housing for everyone. These are the starting points of my research.