22 minute read

Case studies

50 x 50 House for Mass Production, Mies Van Der Rohe. Maison Domino, Le Corbusier. Unité d’Habitacion, Le Corbusier. Quinta Monroy Social Housing, Elemental. Urban Village, Effekt. Farmhouse, Precht. Centre Pompidou, Renzo Piano and Norman Foster. Transformation de 530 logements, Lacaton and Vassal. Al-bahr towers, Aedas. Student housing Weesperstraat, Herman Hertzberger. La Borda, Lacol.

Advertisement

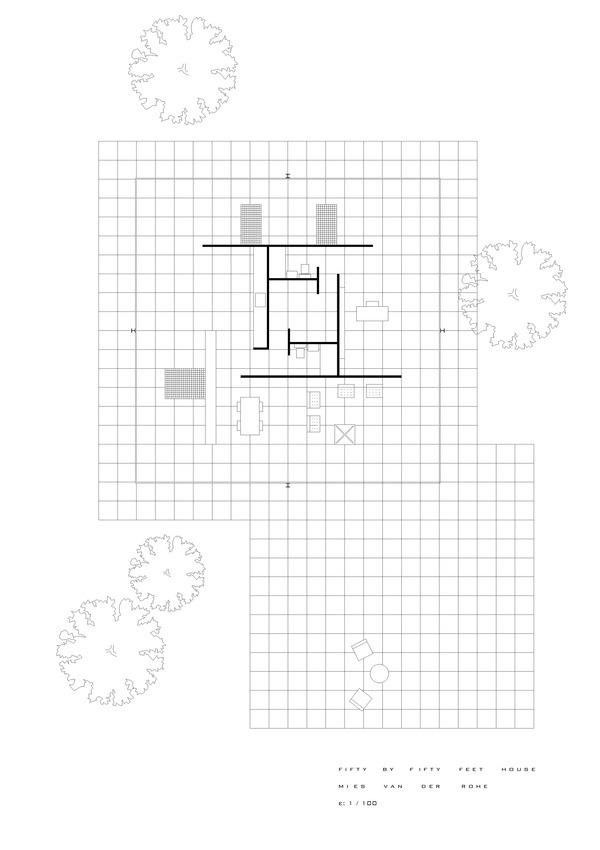

Year: 1951 Location: Unbuilt

. Description With this project, unbuilt, Mies Van Der Rohe has the aim to address the question of mass-housing. Conceived as a prototype intended for industrial production, the House is a square enclosed within glass walls. A central fxed core, the only room of the house, including an open kitchen and two bathrooms, occupies the centre of the volume. The resulting open space can be then partitioned with furnitures, curtains or lightweight walls. Only four exterior columns, located in the middle of each side of the square, carry the weight of the fat roof, enabling the presence of glass even in the 4 corners. In this project, the concepts of free plan and neutrality of the space is taken to an extreme level in order to set the possibility to accomodate every changing need of the family or economic shift. . An example of Spatial Flexibility The freedom of this plan and the presence of a minimal structural system make this project an excellent example of Spatial Flexibility. Theoretically, space can be customised according to needs, in the framework of a structural grid regulating the design composition. Technologies of that time wouldn’t been advanced enough to enable easy processes of construction and deconstruction. Notwithstanding, today the availability of more techniques and materials could enable this conceptual project to become real.

. To know more: http://socks-studio.com/2013/11/23/a-50-x-50-house-for-mass-production-1951an-unbuilt-project-by-l-mies-van-der-rohe/ https://sixtensason.tumblr.com/post/117348287468/ludwig-mies-van-der-rohe50-x-50-house-1950-52

Mies Van Der Rohe, plan of the project.

Maison Domino. Le Corbusier

Year: 1914 Location: Unbuilt

. Description This new construction system has been frst envisioned in the autumn of 1914, after the devastation of Flanders, in view of a future reconstruction. Made of standardised elements of reinforced concrete, Maison Domino was a simple framework carrying foors and staircase. It’s the frst example in architecture of free plan: an open system, a platform for residents to complete as they see ft, that could be adaptive to diverse building typologies. The open structure could be defned according to the needs of the user and to the ideas of the architect concerning the positioning, the size and the shape of services, partitions and external walls.

. An example of Replicability Over time, the structure of the Maison Domino has became a normal procedure in architecture. It’s echo could be even observed in high-architecture. Rolex Learning Centre by SANAA, for instance, as a fuid landscape of nothing but foor, ceiling and columns. In this regard, Maison Domino offered great degree of spatial fexibility and technical adaptability but, due to the material it was made of and to the use of wet joints, this structure couldn’t be suitable for disassembling and couldn’t permit a fast process of customisation.

. To know more: http://www.fondationlecorbusier.fr/corbuweb/morpheus.aspx?sysId=13&IrisObj ectId=5972&sysLanguage=en-en&itemPos=102&itemCount=215&sysParentId= 65&sysParentName=home

Sketch of the Maison Domino by Le Corbusier, 1914.

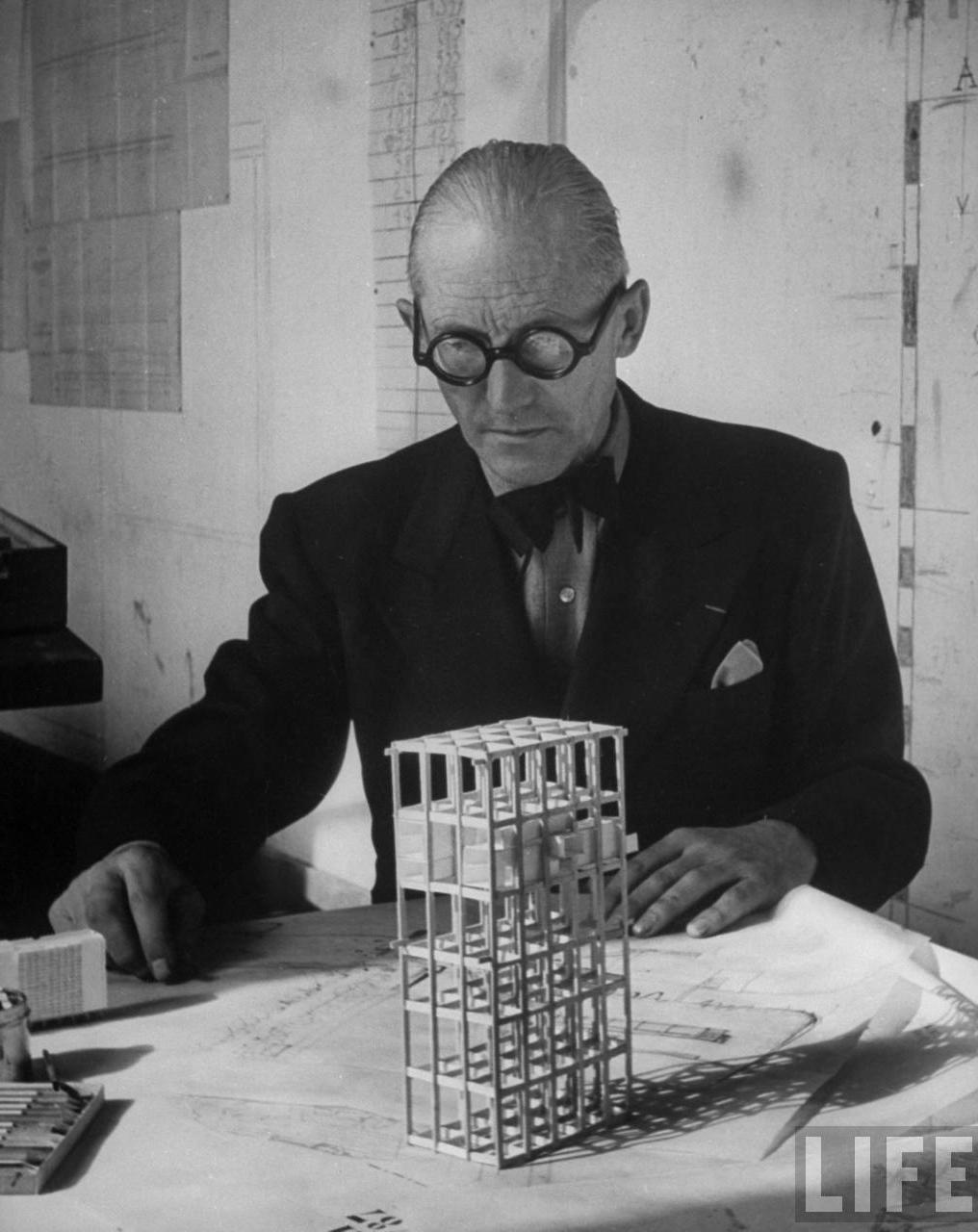

Unité d’Habitacion. Le Corbusier

Year: 1947-1952 Location: Marseille, France

. Description Unité d’Habitation is a stepping stone in the carrier of Le Corbusier as well as, more broadly, in the history of architecture. Through this project Le Corbusier advocates skyscrapers as units of integrated urban architecture which can achieve an exact, established function and occupy a pre-determined space, opposing to the concept of single-family housing. In this regard, modular housing units are integrated with services, aimed at guaranteeing the functional autonomy of the block. Architecture is the product of rationality. Modular housing units, based on Le Corbusier’s theories of rate of scale anticipating the concept of Modulor and here used for the frst time, are inserted into an existing permanent grid. As in the game of Tetris, modular units fnally acquire a holistic meaning when grouped all together. . An example of Demand Adaptability The concept at the bottom of the design of the Unité D’Habitation is the presence of a tridimensional grid in which different housing modules and services can be plugged and piled. It is the outcome of a recurrent vision of that times, where city is envisioned in an architectural way, (Yona Friedman and the group of Archigram, as above mentioned, are some examples). According to that, single modules could be easily add and taken out from the grid according to demand and needs. Notwithstanding, the rigidity of the structural grid, the materials used, the introvert character of the overall block and the extreme rationality of the modules marked the failure of the complex and of the artifcial replicability of cities. Even if theorised, the concept of plug-and-play wasn’t reality yet. . To know more: https://en.wikiarquitectura.com/building/unite-dhabitation-of-marseille/ http://www.fondationlecorbusier.fr/corbuweb/morpheus.aspx?sysId=13&IrisObje ctId=5234&sysLanguage=en-en&itemPos=61&itemSort=en-en_sort_string1%20 &itemCount=79&sysParentName=&sysParentId=64

Le Corbusier and the model of Unité d’habitacion, Life Magazine, 1946.

Quinta Monroy Social Housing. Elemental

Year: 2003 Location: Iquique, Chile

. Description Chilean Government asked to Elemental to settle the 100 families of the Quinta Monroy, in the same 5,000 sqm site that they have illegally occupied for the last 30 years which is located in the very center of Iquique, a city in the Chilean desert, with a really low budget. Therefore, the challenge was how to build decent homes for these families when there was almost no money left for the housing itself after purchasing the land. Therefore, Elemental tried to make a more effcient use of the land, working with row houses, trying to make fexible typologies enabling for future expansions. The basic design idea is that Social Housing is here perceived as an investment rather than an expense. Hence, the architecture design involves just the housing core, half-a-house. Over time, users, according to their needs and budget, can decide to implement it. The initial dwellings are double-height, robust concrete block structures ftted out with the very basics — a kitchen, bathroom, some partition walls, and an internal timber stair. Each of these boxlike structures alternated with an empty space of exactly the same size, where family can expand their own home, confguring the space however they desired. Each had the potential to become a generous family home. As the residents moved in, they could take these generous spaces and tailor the structure to their needs, customizing their space at their own expense and labor — adding color, texture, and life, developing a sense of pride, ownership in and belonging to their homes. With generous, customizable homes and a desirable location, each dwelling more than doubled in value within the space of a year. . An example of Demand Adaptability In a context where informality has been the norm for years, Elemental provides a framework that set the rules for self-construction. In this kind of social context, this approach is smart in the way it still enables for self-expression, even setting an order. People, in this way, can still feel a sense of belonging to their own shelter, as they have room for customisation. Nevertheless, in another type of context this kind of approach could be problematic, as it basically leaves half of the house completely unfnished. The strategy therefore shall probably look at fostering adaptability through a structure that can host several functions and be easily customised according to needs. . To know more: https://dac.dk/en/knowledgebase/architecture/quinta-monroy/ https://www.plataformaarquitectura.cl/cl/02-2794/quinta-monroy-elemental

Elemental. Quinta Monroy Housing Project. Iquique, Chile. 2003-05 Photo: Tadeuz Jalocha

Urban Village. Effekt

Year: 2018 Location: Unbuilt

. Description The concept stems from a collaboration with SPACE10 on how to design and build homes, neighbourhoods and cities through Design for Disassembly. Effekt thus creates a new building system for disassembly made of wood, that can be prefabricated, fat-packed and quickly assembled on site. This system, suitable both to generate housing prototypes and side functions, is made of customisable components. Therefore, the user can decide which ones suit him more according to his needs. The architectural frm also envisions a new system to lower the entry point to the housing market, with a holistic approach toward Circular Economy in architecture that aims at fnding solutions at different scaled and challenging our current way of inhabit our homes.

. An example of Reuse In order to be effective in terms of Design for Disassembly, modularity is an essential feature of the project. Through the use of just a few components, it’s possible to design different housing units, that can be diversely piled to form more housing blocks. The overall approach is coherent to the principles of Design for Disassembly, even if Effekt doesn’t report any news regarding the insertion of plumbings and services, as the kitchen and the bathroom. Plumbing is generally an issue in terms of Design for Disassembly, due to their low level of recyclability. . To know more: https://www.effekt.dk/urbanvillage

Effekt. Urban Village Project. Render by Effekt.

Farmhouse. Penda

Year: 2019 Location: Unbuilt

. Description Architecture studio Precht has developed a concept for modular housing where residents produce their own food in vertical farms, in order to reconnect people in cities with agriculture and help them live in a more sustainable way. Prefabricated A-frame housing modules made from cross-laminated timber (CLT) provide fexible living spaces and, on the external walls, space to grow vegetables. In this regard, each of the walls is made of three layers. An inner layer, facing the home interior, holding electricity and pipes; a middle structural layer flled with insulation; an outside layer holding all the gardening elements and a water supply. Modules can differ for their external wall, that can be made of hydroponic units for growing without soil, waste management systems, or solar panels to harness sustainable electricity. Assembling these modules according to each need, single-family users can build their own homes. The smallest living confguration available is just nine square metres with a 2.5-square-metre balcony. Nevertheless, the system doesn’t limit the height of the tower, because it is adaptable to a different thickness of the structure. . An example of Modularity Penda develops the concept of urban sustainability from different points of view. Modularity and design for disassembling come with tools providing urban agriculture, that permits energy and resources’ savings. Moreover, these type of modules are interesting in the way walls can be structural and host plumbing as well, still being customisable on the external layer. The choice to use timber in high-rise is also challenging but crucial as way more sustainable than a concrete structure, especially because of its lightness. . To know more: https://www.precht.at/the-farmhouse/ https://www.dezeen.com/2019/02/22/precht-farmhouse-modular-vertical-farms/

Render of the Farmhouse Tower by Precht.

Centre Pompidou. Renzo Piano and Norman Foster

Year:1971-1977 Location: Paris, France

. Description Centre Pompidou, locally known as the Beaubourg, is a cultural landmark that has its structure and mechanical services visible on the exterior of the building. The project, Described by Piano as a “big urban toy”, was the outcome of an international competition hold in 1971 and won by Roger and Piano, and it was fnally completed in 1977. It contains six-storeys of large column-free spaces, that, due to the exterior placing of all the building services and structure, can be easily re-arranged when needed. Alongside the exposed structure, Centre Pompidou’s facades are covered with colour-coded building services: blue marking its air-conditioning, yellow is for electrics, green denotes water pipes, and red highlights tubular escalators and elevators. These stand out from a minimal curtain wall backdrop made from steel and a mix of glazed and solid metal panels that were designed to create the feeling of a transparent building envelope. . An example of Systems’ Independency The high level of fexibility of Centre Pompidou is given by the transfer of all the service systems on the outside of the building. In this way, internal composition doesn’t have to respect any type of constrain. Moreover, systems are in this way visible and accessible, as they follow an aesthetic of that times based on the honesty of the building system. Even if not specifcally Design for Disassembly, this project could be read as a radical interpretation of systems independency and recognisability. . To know more: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/11/05/centre-pompidou-piano-rogers-high-techarchitecture/

Renzo Piano and Norman Foster, Centre Pompidou. Photo: Michel Denancé.

Year: 2011-2016 Location: Bordeaux, France

. Description The project consists of the transformation of 3 inhabited social buildings, as frst phase of a renovation program for the ‘Cité du Grand Parc’ in Bordeaux. Built in the early 60’s, these housing blocks, called G, H and I, with a height of 10 to 15 foors, especially gather 530 dwellings. In order to avoid big expenses, the economy of the project is based on the choice of conserving the existing building without making important structural interventions. Instead, generous winter gardens and gardens applied on facade are the key to enhance in a lasting way the dwellings quality and dimension. An opportunity to live outside, while being at home, to enjoy more natural light, to provide more spatial fexibility and openness toward landscape, while reaching high energetic standards. In this regard, the outdoor spaces are large enough to be fully used (3,80m deep on the south facades of H and I buildings and on 2 façades of G building), developing generous, pleasant and performing dwellings, able to improve current living conditions, comfort and pleasure, and the overall urban image. . An example of Systems’ Independency The intervention of refurbishment here depends on the application of an entire independent new element of facade, that becomes at the same time a tool of sustainability, affordability and sociality. Moreover, the opening toward the exterior and therefore the improvement of the permeability of the block becomes a way to promote the building itself and to connect it to the urban context. . To know more: https://miesarch.com/work/3889 https://www.lacatonvassal.com/index.php?idp=80 https://www.floornature.it/lacaton-vassal-vince-eumiesaward-il-grand-parcbordeaux-14609/

The additional facade. Lacaton and Vassal, Transformation de 530 logements. Photo: Philippe Ruault.

Al-bahr towers. Aedas

Year: 2012 Location: Abu Dhabi, Emirates

. Description The extreme weather conditions of Abu Dhabi, characterised by high temperatures and no rain and by an harsh environment where sand can easily compromise buildings’ structural integrity, give architects the boost to design an innovative and adaptive sun-sharing skin system. The system is applied over two 25-storey cylindrical offce towers, parametrically designed based on islamic geometric mosaics. In order to avoid extreme solar gains, that would result in a bad indoor climate, Aedas design a skinsystem of triangular screens arranged in a series of scalable hexagons fold up to create a solid solar barrier. The screen operates as a curtain wall, sitting two meters outside the buildings’ exterior on an independent linear actuator which enables it to function in response to the position of the sun, effectively reducing heat gain and glare by 50% while giving islamic vernacular a contemporary representation. The intelligent facade, together with solar thermal panels for hot-water heating and photovoltaic panels on the roof, minimize the need for internal lighting and cooling, altogether reducing total carbon dioxide emissions.

. An example of Systems’ Independency This project is just an example of the advantages that a Double Skin Facade system can provide in terms of environmental adaptability and building characterisation. This independent secondary skin becomes the smart tool to provide indoor comfort. Thanks to its modularity, eventual episodes of maintenance would imply the intervention just on one of the modules, without compromising the overall functionality of the structure.

. To know more: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/aedas-al-bahar-towers/

The indipendent element of external facade. Aedas, Al- Bahr Tower. Photo: Christian Richter.

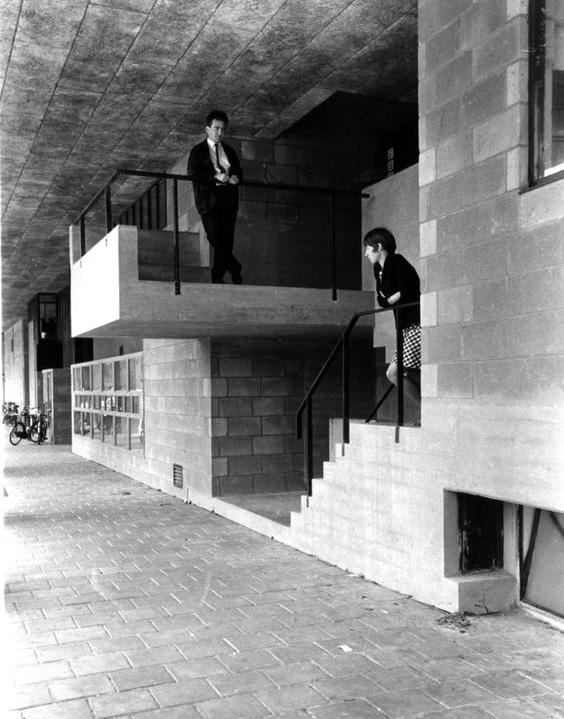

Student housing Weesperstraat. Herman Hertzberger

Year: 1959-1966 Location: Amsterdam, Netherlands

. Description The accommodation for married students shapes along a wide residential corridor, as a prototype for pedestrian streets with usable outdoor space. Bedrooms are the only private space of the accommodation: living and dining area, as well as the kitchen and laundry are shared. . An example of Space Sharing What’s interesting of this project is the presence of several architectural details suggesting social interaction, without forcing it. This type of approach is visible in the corridor, that becomes an informal linear place of gathering. Nevertheless, the privacy of bedroom is still granted due to the interruption of this linearity with the creation of niches. Surely, the will of sharing is stronger in a student house rather than in a residential complex. Notwithstanding, social housing could be a way to rethink the role of the adjective social, not just with the meaning of affordable but also of mutual support. Hence, the importance of re-thinking layers of sharing in order to be comfortable for both the parties: the user and the guest. . To know more: https://www.ahh.nl/index.php/en/projects2/14-woningbouw/135-studenthousing-weesperstraat-amsterdam

Informal interaction between users. Herman Hertzberger, Student Housing Weespertraat.Photo: Johan van der Keuken and Herman Hertzberger.

La Borda. Lacol

Year: 2018 Location: Barcelona, Spain

. Description La Borda housing is a non-speculative housing cooperative with the frst aim to enhance sociality and collectivity. The building program proposes 28 units (40, 60 and 75m²) and community spaces, (as kitchens, laundry, multi-purpose spaces…) located all around a central court-yard, stretching and blurring the threshold between public and private life spheres. In this regard, future users had been consulted through workshops and periodical presentations during the design phase, in order to understand their specifc needs. Moreover, the project aims at lowering its environmental impact both in the construction work and during its operative life. For this reason, architects prioritized passive strategies to achieve maximum use of existing resources. . An example of Space Sharing The project is interesting in the way it develops the topic of sociality and sharing. Living units are disposed linearly around a central courtyard, that also becomes the connection between spaces. Niches and open spaces make the internal courtyard dynamic and permit different types of relations between users.

. To know more: https://www.archdaily.com/922184/la-borda-lacol

The courtyard. Lacol, La Borda. Photo: Lluc Miralles

Winter Garden Housing. Atelier Kempe Thill

Year: 2015 Location: Amberes, Belgium

. Description The city of Amberes is currently trying to reply to the growing housing demand of the city. Thus, the project has the aim to foster a new expression of Flemish collective housing, capable of combining housing quality and urban density. In this regard, Atelier Kempe Thill acts in two directions. On one side, it provides a high degree of fexibility thanks to the strategic position of the core of accessibility and to the use of internal movable partitions. On the other, it decides to add a plus in terms of liveability thanks to the addition of wintergardens on both the long sides of the block. They ‘re averagely 10 m long with a depth of 2.6 m and they offer an in-between space to people who inhabit the housing units. . An example of Urban Branding The project is located in a new segment of the city, currently under development. The insertion of winter gardens on massive blocks is a way to make them lighter and beautiful, branding the new area. They are also a sort of showcase for people living in, a buffer that makes a connection between inside and outside environment, between private and public.

. To know more: https://archello.com/it/project/winter-garden-housing-antwerp-nieuw-zuid https://www.archdaily.com/916263/winter-garden-housing-atelier-kempe-thill

Photo by Photo: Architektur-Fotografe Ulrich Schwarz

The project

Given the above, the project envisions a new construction system with the aim to reply to the above mentioned goals of Circular economy and Design for Disassembly.

To achieve this result, the design project stems from the decision to use a modular bolted concrete structure, that provides durability, according to its life expectancy, resistance and possibility of reuse.

Building for disassembly doesn’t necessarily mean to build temporarily. It means, instead, to build something durable with the potentiality for it to be one day dismantled. In order to reinforce and enhance the sustainability and liveability of each housing unit, the project makes use of the element of Double Skin Facade in a strategic way, as a qualitative tool characterising the new system, aesthetically, socially and environmentally speaking. It encloses the housing unit, that could thus be perceived as a sum of spaces, and gives them an holistic and integrated meaning, providing them with a better indoor climate and additional free space. Te combination of these systems and the use of an approach based on Design for Disassembly gives this construction method the potential to achieve all the mentioned goals of circularity. In fact, it enables:

Spatial fexibility. Diferently from a traditional beams and columns structure, the use of punctual and scattered shear walls permits more fexibility in the design of spaces. According to this innovative construction method, the concept of functional core breaks. Te lack of distinction between service and structural walls results in more space adaptability over time and in the use of less material. Te element of facade contributes to this fexibility thanks to its level of ambiguity and uncertainty, that also means freedom in the way it is used.

Demand Adaptability. Even if totally refned, each housing unit, thanks to the presence of scattered shear structural/service walls and to the additional space of the liveable double skin facade, could be eventualy increased depending on demand. Incremental housing does not necessarily imply the concept of unfnished.

Replicability. Te simplicity of this system, made of just a few modular structural pieces, and the use of concrete, that is one of the material mostly available and used worldwide, makes this system easily replicable. Te strategic use of the element of Double Skin Facade permits, instead, to avoid standardisation and to contextualise each building block, every time, according to each diferent location and to available local resources.

Reuse. Te use of modular components permits potentially their further reuse. Tis especially depends on the materials each component is made of. For what concern the structure, the use of concrete makes the possibility of reuse without any further process of remanufacturing possible, as has already been displayed by many past design experiences. Te project of Resource Row by Lendager group shows the same possibility concerning external facade. Nevertheless, the use of more technologically high-performance facade systems could prevent from direct reuse and need for more expenditures due to processes of recycling. Te investigation shall thus focus on fnding the correct balance between the positive impacts of high-tech components and their further recycling costs at the end of their life.

Non-intrusive maintenance. Te use of mechanical connections integrates building systems maintaining their relative indipendency. Te modularity of each building component and the accessibility of joints between elements permit to isolate and punctually fx eventual damages. Moreover, the use of Double Skin Facade enable a continuity in the normal use of the housing unit over the overall operative life of the building, as, in case of modules reparation or substitution, user can still use the essential part of the housing unit, enclosed by the inner skin.

Space sharing. Te element of Liveable Double Skin facade enables the creation of an ambiguous space, not indoor and neither outdoor, a threshold between public and private space that could be eventually shared. Te possibility to share it would result in fact in a higher degree of afordability, as a Space of transition, (...), equally accessible from both the private and public sphere; it is without saying that both the sides shall accept that the other one has the right of using it. (1).

Urban Branding. Te element of Liveable Double Skin can become a way to make peripheral segments of the city catchy and attracting, reinforcing eventually the concept of vicinity and of policentric city. Moreover, this threshold can be perceived as an individual showcase, expression of each user. It generally permits to rethink an aesthetic for Design for Disassembly into an urban context in a successful and engaging way.

Nevertheless, all these design goals can’t be reached if not integrated into a policy and fnancial framework ensuring the circularity of components and resources. In the next chapter, thus, I’ll explain specifcally the building system and the new fnancial model it envisions.

(1) H. Hertzberger (1991), Lezioni di architettura, Editori Laterza, 1996

Next page: R. Buckminster Fuller and S. Sadao (1960), The Dome over Manhattan. The dome was conceived to decrease use of resources. The new building system represents the same concept on the architecture scale: the skin of the building protects whatever spatial phenomenum happens inside while characterising its overall aspect and thus the context it belongs to. Photo: https://medium.com/ designscience/1960-750843cd705a

Home as a Service to achieve the goals of circularity in architecture

Spatial fexibility

The lack of distinction between service and structural walls results in more space adaptability over time and in the use of less material. The element of facade contributes to this fexibility thanks to its level of ambiguity and uncertainty, that also means freedom in the way it is used, as an expansion of the interior space.

Demand adaptability

Even if totally refned, each housing unit, thanks to the presence of scattered shear structural/service walls and to the additional space of the liveable double skin facade, could be eventually increased depending on demand. Incremental housing does not necessarily imply the concept of unfnished.

Replicability

The system is simple and made of just a few modular structural pieces and for these reason it can be easily replicated over different typologies. The element of Double Skin Facade permits, instead, to avoid standardisation and to contextualise each building block, every time, according to each different location and to available local resources.

Reuse

The use of modular components permits potentially their further reuse. The structure, as made of concrete, can be reused without any further process of remanufacturing. The types of processes required for the reuse of the outer layer of facade, instead, depend on its hightechnology and materials.

Non-intrusive maintenance

The use of mechanical connections permits the indipendency of building systems, resulting in an easier eventual maintenance over time, as damages can be isolated. Moreover, in case of modules reparation or substitution, users can still use the essential part of the housing unit, enclosed by the inner skin.

Space sharing

Users could decide to share the space of threshold. This would result in a higher degree of affordability, as a Space of transition equally accessible from both the private and public sphere.

Urban branding

The element of Liveable Double Skin defnes the aspect of the city and can enhance peripheral segments, reinforcing the concept of policentric city. This threshold permits to rethink an aesthetic for Design for Disassembly and Social Housing.