Kríti

WALKING means travelling—moving from one place to another. Advancing, exploring, and innovating. The Walking Society is a virtual community open to everyone from all social, cultural, economic, and geographical backgrounds. Individually and collectively, TWS champions imagination and energy, offering valuable ideas and solutions to better the world. Simply and honestly.

CAMPER means “peasant” in Mallorquin. Our brand values and aesthetics are influenced by the simplicity of the rural world combined with the history, culture, and landscape of the Mediterranean. Our respect for the arts, tradition, and craftsmanship anchors our promise to deliver original and functional high-quality products with aesthetic appeal and an innovative spirit. We seek a more human approach to doing business, striving to promote cultural diversity while preserving local heritage.

KRÍTI has a wild soul and an ancient heart. Known as the Zeus of the Greek archipelago, the island is a tapestry of stories that blur the boundaries between reality and mythology.

THE WALKING SOCIETY The seventeenth issue of The Walking Society Magazine takes us on a journey to the cradle of modern civilisation. An island where the snow meets the sea, the past embraces the present, and where no one leaves the table without a round of raki.

P. 22 CAMEL PARADE Deep in the Cretan hinterland with the man behind one of the island’s most bizarre traditions: the camel parade—which originally featured donkeys. P. 34 ILIANA MALIHIN A tale of struggle and rebirth: Iliana’s comeback from a devastating fire and the story of a wine that tastes like Kríti. P. 43 THE LABYRINTH The famous myth through the eyes of the Minotaur and others who believed that the world itself was but a labyrinth. P. 50 GREEK FRETS Meanders as you’ve never seen them before. An unexpected ode to freedom through armpit hair (and more). P. 58 TÁLŌS The legend of the impenetrable bronze giant who protected the island from invaders by circling its perimeter three times a day. P. 64 ELAFONĪSI Kríti’s most enchanting beach, where the sand is the colour of the sunset and the sea tries to steal its hues.

P. 86 STAND LIKE A GREEK An iconographic exploration of a people who only seem to exist in profile, revisiting their most common postures, both physical and intellectual. P. 107 SARIKI The history of the sariki: from traditional Cretan garment to decorative element adorning rearview mirrors. P. 115 THE MINOAN GODDESSES Votive statuettes from the 13th century BC with raised arms, invoking the afterlife and connecting the human and the divine. P. 122 NIKOS TSEPETIS A journey into the multifaceted world of Nikos Tsepetis through his creations: Ammos Hotel, Red Jane Bakery and the upcoming Garten. P. 130 CRETAN COSTUMES From folk dances to everyday life, traditional Cretan garments embody an ongoing dialogue between past and future. P. 144 LITTLE JOHNS A children’s workshop celebrating British artist John Craxton and his love for Kríti, led by visionary teacher Eltha Yiakoumaki.

Kríti has many souls and just as many superlatives. Besides being the largest Greek island, it also lies at one of the southernmost points of the Mediterranean. Stretching 260 kilometres from east to west, it is traversed by a long mountain range that lifts it from the sea, forming a spine up to 60 kilometres wide with atypically snow-capped peaks.

Considered the Zeus of the Greek archipelago for its size, Kríti is also the birthplace of the father of all gods. Classical mythology has it that Zeus was born in a cave on Mount Ida, the highest mountain on Kríti, where he was raised by nymphs who fed him honey and goat’s milk—both still integral to Cretan culture today. As always, there are various versions of what happened next. What we do know for sure is that the island soon became a symbol of perfection, prosperity and divine favour, thanks in part to the protection provided by Tálōs, the unyielding iron giant.

Another famous child of Kríti—born years later, outside the mythological realm—is Nikos Kazantzakis, a writer and poet whose work captures the painful beauty of this land better than anyone else. In his autobiography, Report to Greco, he describes it as follows:

“There is a kind of flame in Crete—let us call it ‘soul’—something more powerful than either life or death. There is pride, obstinacy, valour, and together with these something else inexpressible and imponderable, something which makes you rejoice that you are a human being, and at the same time tremble.”

Olivia is 10 years old and lives in Irákleio. Her mother is from Genoa and her father is from Kríti. She likes dancing, but most of all swimming and diving. She has a dog, which is two years older than her, and two brothers, one of whom lives in Italy.

Arselaida is Albanian but moved to Irákleio at a very young age. She finds the culture here similar to her own, but living on an island is completely different. She works as an English teacher and enjoys interacting with other cultures. It helps her discover a little more about herself, she tells us.

Nefeli is from Irákleio. She moved to Lyon to study law but soon realised it wasn’t the right path for her and returned home. Now she studies marketing and works in the industry. She speaks five languages but thinks that communication is primarily about colours. “Kríti,” she says, “is full of them.”

Clementine works in finance and lives in Chanià. Her dad is from Ithaca and her mum is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They met on Ulysses’ island after she had embarked on a contemporary odyssey. Despite this, Clementine’s Kríti remains her Ithaca.

Years earlier, Kazantzakis found himself embodying the same Greek “obstinancy” in an enterprise that was equal parts courageous and ill-advised: the rewriting of The Odyssey. His aim was to rescue the handful of words that were gradually disappearing from the Greek dictionary. He succeeded by interviewing village elders and treasuring their knowledge, knowing that, on Kríti, every past deserves to be remembered.

Cradle of the Minoan civilisation, one of the world’s oldest, the island has long been a crossroads of peoples and cultures. After the fall of the kingdom of Minos, the Mycenaeans, Dorians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Venetians and Ottomans all passed through Kríti, each leaving their mark. This rich mosaic of historical influences can still be seen in the archaeological sites and architectural stratifications. The northwestern city of Chanià, for instance, is a Venice whose cards were reshuffled to alter its destiny. The other villages, in comparison, resemble clusters of white cubes, abandoned like the dice of weary gods.

But what catches the eye above all and holds it is nature, at once wild and tamed. At the foot of the mountains that crisscross the island, the hills yield to the call of the sea, from which this small paradise shyly rises.

The fruits of this ordered nature make every meal a sacred ritual. In the homes or taverns, milk, honey, olive oil and wine form the basis of a diet that feels as divine as it is Mediterranean.

Hardly anyone ever gets up from the table. It is but a pretext—a moment for things to return to the way they were and perhaps even the way they should still be. And, if anyone dares to try, they cannot do so without first having a round of raki, the typical Cretan drink. A spirit, in every sense, that serves to honour what has been but equally symbolises local hospitality.

No one is a stranger here and everyone is a guest. In the smaller villages, stories are told of a time that no longer exists, when life flowed slowly and smoothly. The same time that miraculously survives in the remotest corners of this land.

Of all the Greek islands, Kríti holds the most records. It is a place where past and present embrace and where people fight against the disappearance of words. For here on Kríti, it is still yesterday, but also already tomorrow.

Aris is a civil engineer but above all an athlete. After studying in Athens, he took up callisthenics and today spends much of his time upside down. When not training, he works in the family oil-producing business. He lives in Chanià and dreams of sharing his passion with someone special.

Eleanna is originally from Athens but has been living in Irákleio for a few years. Here, she studies social work and supports herself by working in an ice cream parlour. In Kríti, she has discovered a world she never knew existed and intends to hold on to it.

Marina is from Thiva, near Athens, but has lived in Kríti for nine years. She works as a cook in a cooperative but her real passion is music. She recently started bass guitar lessons and is looking forward to her first concert.

Konsta has just turned 30 and runs the beach bar in Ligres. He has an eleven-month-old daughter, Eli, who takes her first steps on the sand while we are here. The sea is his home: he can’t imagine life without it.

Olga and Olga are grandmother and granddaughter, 73 and 10 years old respectively. The elder Olga speaks only Greek, while the younger knows a few words of English. They used to own the beach bar in Ligres, not anymore, but it is still their home. Pelotas

Konstantinos founded the Minoan Pottery company, which has been making ceramic vases in the ancient Thrapsano tradition for 25 years. Before showing us how they are made, he tells us that: “The most important things are those you cannot see.”

CAMEL PARADE

Deep in the Cretan hinterland, among the vineyards and olive trees, lies the village of Nívritos. Here lives 90-year-old Michalis Psomas, the reputed inventor of one of the island’s most bizarre traditions. He speaks only Greek and insists on offering a round of raki, the Cretan welcome drink, before starting any conversation. It is 40 degrees outside, but this doesn’t seem to faze him; the temperature matches the alcohol content inside the glass after all.

Until the 1950s, there was no real carnival tradition on the island. Each village did what it could, celebrating in small groups of family and friends. But Michalis believed much more could be done. After months of research in the basement of his home, he came up with an idea that still animates Cretan carnival to this day: a donkey costume fashioned from a blanket, the head of a (dead) animal and a couple of people to support it. The concept was simple yet sophisticated, incorporating hand-woven cloth in the ancient Minoan tradition. During the parade, the motifs intertwined and overlapped, giving the animals an ever-changing appearance.

Inhabitants of the neighbouring villages were intrigued by the initiative and watched closely, hoping to replicate it the following year. But one key aspect eluded them: the donkey. They mistakenly believed they were witnessing a parade of camels—a tribute to the exoticism of this animal that had just entered the Cretan imagination. Convinced that this was the correct interpretation, they carried on the tradition, unaware of its original meaning. Before long, this became the official version, the truth known only to Michalis and his family.

After a brief hiatus in the 1980s, the camel parade has been an unmissable event for the locals since 1995. Beyond the valley, in neighbouring villages, some choose other costumes, with goats being a common choice. Nevertheless, camels remain an icon of the local carnival celebrations—symbolising an eternal fascination with the unknown that still characterises the most remote parts of the island of Kríti.

Michalis is the creator of the traditional camel parade. Originally intended to be donkeys, the animals were misinterpreted by the neighbours. Initially displeased, he eventually embraced the success of the amusing mix-up.

Of roots and rebirths with

ILIANA MALIHIN

The area surrounding Melambes, in the central region of Réthymno, has a mountainous conformation that gradually softens as it approaches the coast. Vines and olive trees seem to vie for the land in silent, age-old battles. Wild plants take what remains, leaving some space for more barren areas where the sun has the upper hand. A light mist tries to conceal things in the distance, yet the sea still peeps out from behind the mountains.

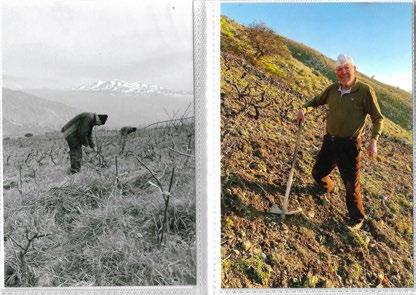

Iliana knows these places as well as she knows herself. But among her vineyards, some have been here longer than she has. The oldest are two hundred years old; the youngest are the same age as her. The project was born in 2019 out of an unconditional love for the land and a desire to bring the flavours of Kríti to the world. In 2022, a terrible fire swept through her vineyards, destroying most of them, but Iliana did not lose heart. Like a phoenix, she rose from the ashes even stronger than before. She did so with a crowdfunding campaign that allowed her to raise what she needed to start again. Today she looks back on those strong vines with the pride that only someone who knows their history inside out can feel and is finally ready to look forward.

Drift Trail, Pelotas Ariel F/W 2024

Tell us about yourself. You are young, but you already have a lot of experience. How did you get into the world of wine?

It is a rather strange story because I was born and raised in Athens, far from nature, but every summer I would come here, to Kríti, to my grandparents’ village. We had a small vineyard and a few olive trees. My oil is called Emmanuel in memory of my grandfather, who passed on his love of this land to me. When I was seventeen, I moved to Kríti to study

agriculture. I returned to Athens to do a master’s degree in Oenology, but I knew that this was where I belonged. During my research, I focused on Vidiano, a white grape variety that we only have here. I rapidly achieved a certain popularity in the Greek wine world, so in 2018, I decided to produce my first wine. It was made from old Vidiano from Kríti and Assyrtiko vines from Santorini. It was the first time anyone had made a blend from two islands in Greece. We sold out immediately!

How many bottles did you produce?

Just over a thousand.

A very good start.

A small start, but certainly an important one. From there, I started looking for other vineyards and ended up here almost by chance. I had never seen anything like it and immediately knew this was the right place. So in 2019, we rented this building, renovated it and set up the winery.

What goal did you set for yourself in 2019 when you threw yourself into this project?

I followed my instincts at first. I knew I wanted to do something different, but exactly what still wasn’t clear to me. Within a short time, I realised that I wanted to change the history of Réthymno. I wanted to help the locals while bringing the old vineyards back to life. They are the only pre-phylloxera [an insect pest that destroyed more than 80 percent of the world’s vines in the 19th century] vines that remain on Kríti and they’re almost 200 years old. Someone had to take care of them, so we identified nearby villages with the same wine culture and started teaming up with local producers. So the goal came later, but it is clear to me now. I would like to help people stay in the villages or return to their land without feeling forced to leave in order to have a future. In the hope that this will give them a better life.

Listening to you talk about it almost makes us want to move here.

It is very difficult, though.

It must be in such an isolated place. What is so special about this region?

Melambes used to be an extremely charming place, but over the years it has been abandoned. Everyone used to have a vineyard here for family production: people made wine for themselves and the village—for celebrations and socialising. Whereas, in Irákleio, the capital of Kríti, wine was produced for commercial reasons. When phylloxera arrived, it destroyed practically all the vineyards in Europe. They should have been replanted, like on the rest of the island. But grapes were only grown for the pleasure of drinking wine. There was no commercial pressure and there were no funds to start over. So today we have the oldest vineyards on Kríti.

In the end, the authenticity of the place was rewarded.

Exactly. I also think that Réthymno has special soil. We have rocks that are found almost nowhere else in the world. And most importantly, we have mountains, even though we are by the sea.

What is so unique about the Vidiano grape that you have been working on since your university days?

It is a special grape. It’s quite big and very tasty. It is reminiscent of the aromas of stone fruits, like apricots and peaches, but also tastes like chamomile. Not many people had heard of it before and now it’s the most famous grape on Kríti. We only have it here after all.

Today you are here with a smile on your face and everything seems to be going in the right direction. In 2022, however, a tragic fire struck your vineyards, destroying everything in its path. How did that feel?

There have always been a lot of fires here. We’ve had fourteen since 1964. It’s a huge problem, but no one seems that bothered. The 2022 fire was the first one that I experienced, but the locals were used to it. They’ve got to know them well over the years, but they were still angry after all the efforts to revive this land. We were told that the fire was started unintentionally by a beekeeper. It was an accident, but the problem was that the fire brigade arrived too late. The fire spread, and we just cannot forgive that. It burned for four days and destroyed twenty one thousand acres of land. A huge area. It was a real disaster.

And how did you feel?

It was terrible. The vineyards are my home, the place where I belong. It was like losing my father six years earlier.

It must have been hard but you reacted extraordinarily. Within a short time, you started a crowdfunding campaign that raised more than fifty thousand euros. You called it ‘Rebirth from the Ashes’ and that’s exactly what you did. How did you manage it?

It took me about ten days. I was in bed with a fever and couldn’t get up. The shock was intense. But I was surrounded by wonderful friends and they gave me the idea to crowdfund and helped me put it together. It resonated a lot in Greece, and abroad too. Here on Kríti, all the restaurants dedicated a whole day to my wines. That gave me a lot of confidence. It soon became this collective cause.

How wonderful that you joined forces. Are you back in full swing today or are you still feeling the effects of the fire?

We are still dealing with the consequences because the vineyards have not returned to full production—those that were completely burnt are just standing still. Then there are the economic problems, which are not to be underestimated. We still don’t have fire protection and we will use the money raised for that, but it won’t be enough. This is only the beginning and there is still a long way to go.

Another good start, nonetheless. But back to you: before the fire, you were producing five types of wine. Today you have added three, to replace the productions that still haven’t restarted. Can you tell us about them?

“Ever since I came here on holiday when I was young, I have felt a magnetic attraction to this land. A powerful feeling that I could not ignore. I believe I am a daughter of Kríti.”

Each type comes from a particular village or a particular combination of grapes. The first three bottles are from here [Melambes]. We no longer produce them because of the fire, but we replaced them with Lefkós and Liatiko Rosé. The fourth is from Fourfouras and the last from Meronas. Each one has something special about it. We differentiate the vinification depending on the village but also the age of the vines.

In the Manifesto of the Third Landscape, Gilles Clément sets out a gardener’s ethic. The gist is to do as much as possible ‘with’ and as little as possible ‘against’. I find this very similar to your ‘low-intervention philosophy’. Can you tell us what that consists of?

My ‘low-intervention philosophy’ requires great patience on the part of the farmer, who must observe the changes and understand what the vineyard needs. That’s because we don’t use any protocols; we approach each cultivation very personally. We ask our farmers to spend a lot of time in the vineyards and to be incredibly careful when pruning because a large part of the production depends on it. The idea is that we should not try to govern the vine. We must stand back, watch and do as little as possible. That is what nature needs. The philosophy is similar with our wines because we don’t change anything from the original product. That is why we have to be careful when harvesting. In doing so, we respect the wine and the terroir from which it originates, without adding or removing anything that could change its flavour.

Who are your wines for?

For everyone! From young people, who are discovering the world of wine for the first time and looking for simple and genuine products, to the more experienced connoisseurs who want to try something special. They are authentic wines for everyone. Everything that’s inside them is listed on the label. And so is the story of the wine, which allows anyone, no matter how far away they are, to take a trip to the land of Kríti and its flavours.

The labels are very highly curated. Each one is a work of art in itself. What is the story behind them?

My cousin designed them all. Each one has a very precise symbolism linked to the wine it represents. The pictures of young girls are linked to young grapes, for example, whereas the older lady is a reference to older vines. Then there are other references to the morphology of the land and the moon in the case of certain biodynamic production processes. The label that amuses me most is the one with the three hands: if it were a normal wine you would see two, but it’s not, so we put three.

Your wines have different origins and aromas, but how would you describe the flavour of Kríti?

Definitely sage. Then sea salt, mountain breeze, olive oil, milk. We have so many.

What does Kríti mean to you? Why did you decide to live here?

It was just a feeling. Ever since I came here on holiday when I was young, I have felt a magnetic attraction to this land. A powerful feeling that I could not ignore. I believe I am a daughter of Kríti.

What plans do you have for the future?

I would like to introduce my wine to the world and spread the Cretan tradition beyond the sea. I find that tasting the products of a place is a bit like having visited it. A journey, limited to just a few senses. At the moment, we export to the United States, New Zealand and Europe, but I would like to do more. In the future, I would like to be safe from fires. I would like to expand production and help people live better lives. I dream of a different life for both villages and farmers. A life where no one is forced to flee anymore.

After destruction, comes rebirth. Iliana knows the weight of each day and captures every moment in a small photo album. Inside, we find every step of the reconstruction—a sort of miracle with an immense amount of work behind it.

LABYRINTH THE 43

There are many ways into the Labyrinth, but none leads to an exit. It may sound like a paradox, yet that is exactly what it is: a deception of space that holds time hostage. Only from above does it make sense—only gods and birds are permitted access. And so, celestial privilege flies over earthly complexity, seeking meaning in human error. It finds it in the Labyrinth. Elsewhere, similarly intricate trajectories

seem to evoke invisible walls. According to The Aleph, written by Jorge Luis Borges in 1949, the world itself was a labyrinth from which escape was impossible—there was no need to build more. But Minos didn’t see it that way.

Legend has it that the ruler of Kríti, son of Zeus and Europa, wanted to assert his right to the throne through divine

concession. This came from Poseidon, who offered the gift of a beautiful white bull. Minos was so captivated by the animal’s beauty that he decided to keep it for himself and failed to sacrifice the bull as promised. This unleashed the wrath of the sea god, who took revenge by making the king’s wife Pasiphae fall in love with the animal. With the help of the ingenious inventor Daedalus, she was able to

consummate her love. This union gave birth to the Minotaur, a monstrous being with a human body and a bull’s head. Minos, disgusted by the creature but unable to kill it, turned to Daedalus for help once more. The structure he designed was so complex that no one could find their way out, including the Minotaur who was trapped inside.

Neither man nor god, the Minotaur only knew what he was not. Seeing countless beings like himself in the mirrored walls that surrounded him, he felt something akin to happiness for a few brief moments. When he realised he was alone in the midst of a sea of Minotaurs copying his gestures, he flew into a beastly rage. According to the writer Friedrich

Dürrenmatt, who dedicated a long series of verses to the Minotaur, he was a being simultaneously locked out of the world and inside that infernal mechanism. The Labyrinth existed because he existed, and a creature like him, reflected the Minotaur at the end of his days, should never have existed.

Yet only Dürrenmatt’s Minotaur understood something of himself before he died. The others simply accepted the condemnation of their nature and devoured everyone who entered the Labyrinth. Legend has it that every nine years Athens had to pay tribute to Kríti by sending seven boys and seven girls to the island to die in the jaws of the Minotaur.

One day, Theseus, the Prince of Athens, decided to put an end to this terrible practice. He volunteered as one of the tributes and set off for Kríti to defeat the monster. Once in Knōsós, he met Ariadne, daughter of Minos, who fell in love with him. Eager to help Theseus, she came up with the idea that would allow him to survive his endeavour.

She gave him a ball of red thread, which Theseus unwound as he advanced through the Labyrinth. After a fierce fight with the monstrous creature, he only had to rewind the thread to find the exit and lead the youngsters to safety. The birds, witnesses to the fight, rushed into the Labyrinth, whose secrets they knew, to devour the monster’s remains.

Since then, all that is left of this place and its history is myth. Walking around the Palace of Knōsós, the major centre of the Minoan civilisation, it is easy to imagine where it all stems from. The architecture was once articulated around multiple overlapping floors, so complex that anyone could

lose themselves. Today, little remains of the palace, but wandering through its ruins feels like retracing the deadend street that led to the Labyrinth. With that in mind, one might glimpse the same path along which human existence was lost—and of which Borges first became a prophet.

Friedrich Durrenmatt, “The Minotaur: A Ballad” in Selected Writings, Volume 2, Fictions, 1985

GREEK FRETS

A Greek fret, as described by Karl Kerényi, is “the figure of a labyrinth in linear form”. One might think that the Greeks enjoyed losing themselves along precise and intricate trajectories, as if visually reconstructing a line of thought. Like small hypnotic traps, Greek frets still capture the gaze of anyone who encounters them, evoking the infinity they once symbolised. Also known as meanders, a reference to the winding path of the Turkish river Maeander, the well-known motif has travelled far beyond its original artistic and architectural context, exploring a wide array of new applications.

If Kríti still had a protector, there would probably be no fires today, the winds would be gentler and the heat waves kinder. But the demigod who once guarded the island was killed at the very hands of a human, blinded by love and a desire to overpower.

According to Greek mythology, Tálōs was an impenetrable bronze giant given to Minos by Zeus to protect the island of Kríti. Half god and half man, he had a single vein running from his head to his ankle, making him partially vulnerable.

Tálōs circled the island three times a day to defend it from invaders. When the enemy approached, he would throw massive boulders at them or crush them in his grip. He would often throw himself into the fire, reaching such high temperatures that his touch became even more inauspicious.

The giant was seemingly invincible, except for that single vein that ended at his ankle, which no one dared approach. One day, with the arrival of the ship Argo, Tálōs was outmanoeuvred. Medea—who was in love with Jason, leader of the Argonauts—struck him with a powerful spell that caused him to lose his balance. Falling, he hit a rock and the blow was fatal.

Since then, Zeus’ rebellious island has existed in this world without a protector, exposed to the rush of the winds and the endless succession of human events.

ELAFONĪSI

There is a place on Kríti where the sand is the colour of the sunset. It is the pink beach of Elafonīsi on the western side of the island. The road to get there is a succession of bends that wind through forgotten villages, where everything has remained exactly as it was. But once there, nature takes the upper hand.

Elafonīsi is an island in itself, but it is also the stretch of coast that faces it. Getting there requires plunging almost completely into the water and following a path that changes with the tides. The colour of the sand comes from ancient shells, broken down over the years by the pounding of the waves. With time, the currents have washed them ashore with the specific purpose of turning everything pink.

Today, hordes of tourists come from all over to see this anomalous colour in the sand. Some come dressed to match, hoping to accentuate the hues even further. Others come laden with empty bottles to fill with sand and commit the unspeakable crime. The island opposite observes the human rush from afar, gladly immune to it. A little further on, the locals wait impatiently for the sun to set. “No tourist ever stays the night,” they tell us, “and the sand becomes even pinker when they leave.”

F/W 2024 WALK, DON’T RUN. Pelotas Ariel

F/W 2024 Pelotas Ariel (TWINS), Walden

F/W 2024

F/W 2024 Karst Junction

F/W 2024 Pelotas Soller

F/W 2024 Pelotas Soller

F/W 2024

F/W 2024 Junction Runner BCN

F/W 2024 Onda

F/W 2024 Dean

F/W 2024 ROKU

WALK, DON’T RUN.

F/W 2024 ROKU

F/W 2024 Pelotas Ariel

F/W 2024 Junction Runner

F/W 2024 Karst

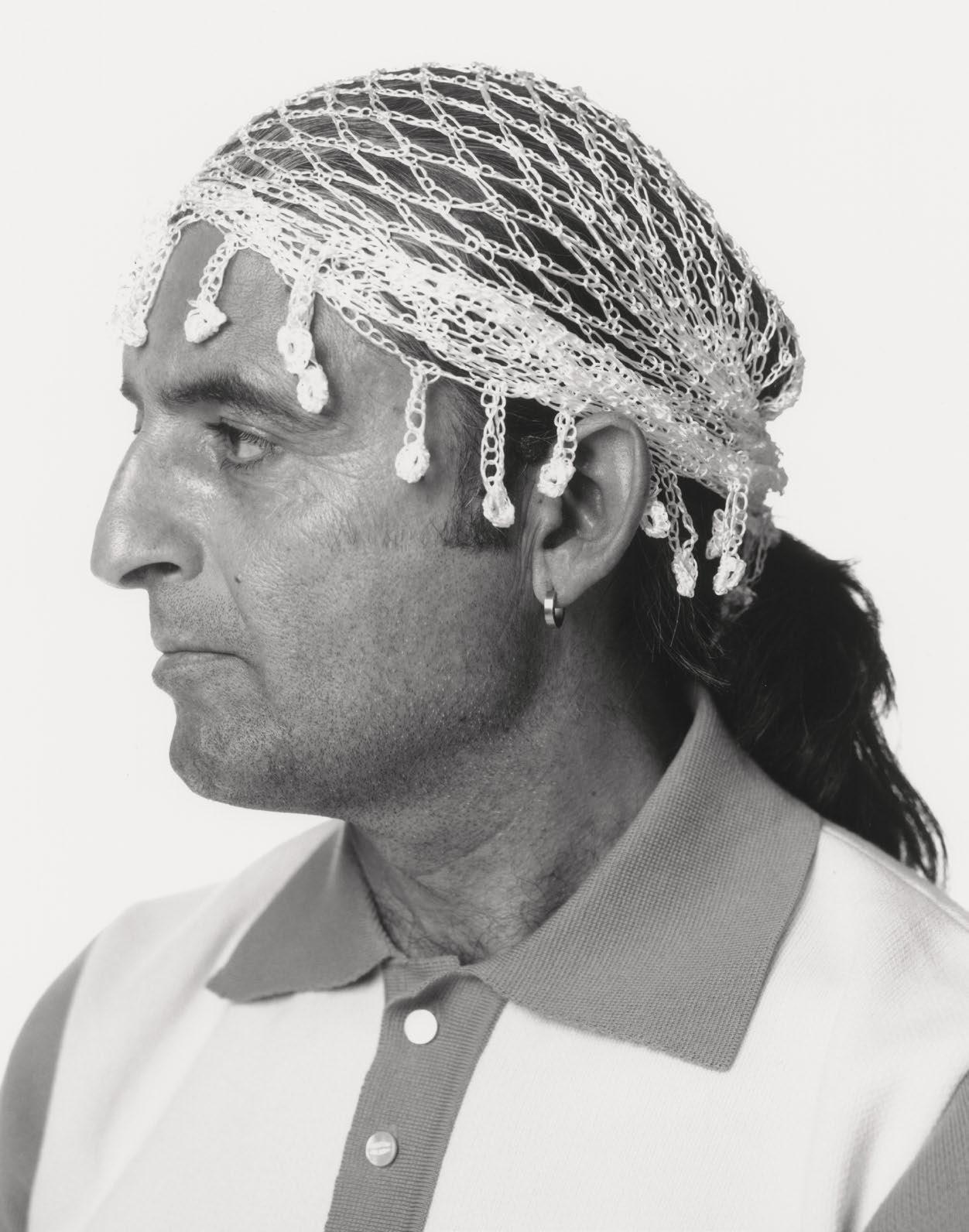

Ancient Minoan art gives the impression that the Cretan people only ever existed in profile. In reality, it was a precise stylistic choice inspired by a preference for content over form and representation at the expense of realism. Images were understood from a symbolic, rather than aesthetic, perspective. This theory is equally supported by a total absence of depth, which makes the figures look like shadows cast on a wall. Unmistakable features emerge from the

black contours, defining a peculiar Cretan physiognomy: large eyes, gentle gazes, pronounced noses. And then the hands and bodies, placed in space like the phonemes of an unknown language. Today, only a few traces of that world remain, preserved in the conditioned air of distant museums, but that distinctive stance—smiling and in profile— can still be found here.

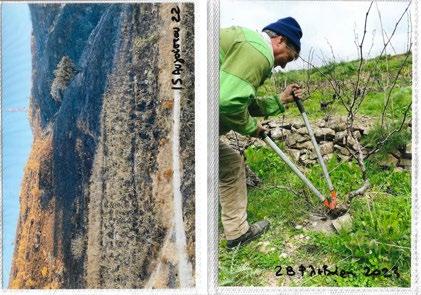

SARIKI

Nowadays, the sariki is usually seen decorating the rearview mirrors of old cars or the hips of girls on the beach, but it was once a much more serious matter. Made from a thick knitted net, it is a turban-like headdress that ends in a series of fringes and tassels. Its origins can be traced back to Turkish rule, after which it became the symbol of Cretan resistance.

However, the real secret behind the sariki tradition is its colour. Black signifies mourning and is worn both at funerals and during the months or years that follow. The implicit message, as a local boy explains, is that life has happened, with the tassels framing the wearer’s face like tears. White, on the other hand, is for moments of celebration, mainly weddings, but other special moments too. Here, the tassels represent tears of joy, symbolising the purity of an existence free from sorrow.

As is so often the case, there is no room for life’s grey areas, which may explain why the sariki has gradually fallen out of use. Nevertheless, it remains an emblem of the Cretan mentality to this day. For at the table and beyond, everything belongs to everyone, and everything belongs to no one. Joy and sorrow—Greek salads and saganaki [fried cheese]. Because that’s the only way to taste it all.

THE MINOAN GODDESSES

Imagine walking through a Cretan vineyard and coming across a clay statuette with its hands raised in an apparent sign of surrender. Now imagine discovering that this statuette dates back to the 13th century BC and that it is not the only one beneath the vines. It may sound like the beginning of a folk tale, but this is precisely what happened in Gazi, on the north coast of Kríti, leading to the discovery of an entire population of small Minoan goddesses. The vineyards were once community sanctuaries where they were tasked with the specific purpose of connecting earth and sky, human and divine. Some say that the raised arms symbolise prayer and blessing, while others interpret it as a greeting from the goddess when she appeared among mortals.

Whichever interpretation you prefer, the recurrence of this gesture—always the same evocation of an invisible elsewhere—is certainly surprising.

Even the faces resemble one another, albeit with different expressions. Some smile reassuringly, while others hypnotise the observer with enigmatic features. Each is defined by these small nuances, which become essential in identifying their nature, like the ornamental diadems that proudly crown their heads.

The most powerful goddess wears a crown of poppy seeds, which have strong hallucinogenic properties. It is believed that her role was linked to sleep, death and the possibility of influencing these states— leading, for example, to miraculous healing. She also evoked the dream world and direct communication with the afterlife, making her both fascinating and feared.

A worthy rival is undoubtedly the snake goddess. In the most common version, the statuette holds two serpents, subjecting them to her power. In another, snakes decorate her crown, giving the impression of being part of her small army. In both cases, the goddess controls nature and determines its actions. She is a powerful but dangerous protector, capable of influencing fertility and

regeneration, atmospheric agents and natural disasters.

After earth comes the sky: the third goddess smiles as birds nest in her diadem. Rarer than the others, she stands as a mediator between the terrestrial and celestial worlds, representing the divine dimension. The birds are her messengers and her work is linked to revelation and prophecy.

Who knows how many diadems still lurk beneath these layers of ancient dust; how many goddesses, as yet unnamed, inscrutably determine the fate of this island.

“In Greece,” Henry Miller states in The Colossus of Maroussi, “the changes are sharp, almost painful.

In some places, you can pass through […] fifty centuries in the space of five minutes. Everything is delineated, sculptured, etched. Even the wastelands have an eternal cast about them.”

Clay ‘Poppy Goddess’ with raised hands, Late Minoan IIIB, Gazi

Clay goddess with raised hands and diadem with snakes, Late Minoan IIIC, Kannia Clay goddess with raised hands and diadem with birds, Late Minoan IIIC, Karfi

NIKOS TSEPETIS

Nikos Tsepetis greets us at the entrance of his new bakery with Johnny, his inseparable Boston terrier. Before letting us in, however, he decides to show us his home, which is just around the corner. We go up to the seventh floor in a lift made entirely of mirrors and arrive in a well-kept loft, where everything happens in a single room. The main wall opens into a large window that frames the old town of Chanià and the blue sea. The apartment is white, with the odd colourful detail purposely placed to catch the eye. A blue bookcase with lopsided, empty shelves (books are to be found everywhere, especially on the kitchen counter); a red Thonet with one knotted leg; a photograph of an interior, which dialogues with the loft as if it were another branch of it—a room within a room. He reserves the bathroom for all the things he doesn’t like enough to put on display, including an endless pile of magazines and some works of art. At the far side of the room, we notice a hole in the floor and discover it is all that remains of a Simone Fattal sculpture, once fixed to prevent it from falling.

The house is magnetic, but Red Jane Bakery is waiting for us a few minutes away. Nikos tells us about the project, from the story behind the name to the collaboration with Michael Anastassiades. He talks about Ammos Hotel, simultaneously a blessing and a curse, which has bound him to Kríti, and about Garten, his future ‘baby’, where design will no longer take centre stage. His rule? Keep changing, for in stasis lies the trap.

You were a journalist, then an entrepreneur with a passion for design. Tell us your story.

I was a journalist for ten years. Now I run a hotel. My father started building the hotel in the mid-80s when I was still a child. He left it halfway through, and the baton passed to me. I opened the hotel in 1996. For the first few years, I split my time between the hotel and working as a journalist. But then, in the mid-2000s, I decided to give up on writing.

What did you write about?

Mostly politics. I took pictures and wrote articles. They were the golden years, the bubble. Everyone was getting paid, and very well too.

Things have changed.

The crisis changed everything. Back then, I wrote a controversial column and lived in fear of being sued. That’s why journalists in Greece don’t have anything in their name, but I had the hotel. I couldn’t afford to lose it. Today, my job is taking care of people.

Was that the Ammos Hotel?

Yes, exactly. I called it ‘Ammos’, which means sand in Greek.

A fitting name given its views over the sea. How did it all happen? What was the vision behind Ammos?

As I said, it came to me almost by chance. I would never have decided to become a hotelier had it not been for my father. He had already built half the hotel... I had no way out. I had to do something with it. I had planned to go abroad and study film. But there’s no point thinking about that now. In the end, I became a hotelier. I wanted to bring together the things I like at Ammos, namely food and design, and do it in a way that is respectful of the people who pay to come here every day. I have to admit that I am never actually happy with what I do. I feel like there’s always something that could be done better.

You are a perfectionist.

I’m a perfectionist, that’s just the way it is. The bakery, for example. It came about by chance. I saw this building and immediately wanted to buy it. But I had to work out what to do with it. I didn’t want to create a design gallery, displaying or selling products.

Design has to be in context. It has to make sense.

Yes. I like the idea of creating something more than selling objects.

That’s exactly what you did with the hotel. Some say it resembles jazz improvisation. How did you choose the individual pieces?

It resembles jazz because it wasn’t all done at the same time. It is the result of a very long process. I have changed gradually over thirty years and Ammos has changed with me. It all started when we opened. The hotel has always had an excellent location. The service was good, the people were kind and the rooms were clean, but nothing was planned. The first phase was very ‘easy’. I had no budget at the time, which meant no decisions to make. It took me years to work out what I wanted and to work up the courage to change. It’s easy when you do things like the bakery, where there’s a clear plan and you do it all properly. We haven’t changed a single thing at Red Jane since the day we opened and it works. I’ll never change anything about it. It’s a lot more work when you don’t know where you’re going from the beginning, or you don’t have the budget.

But the result is more interesting.

That’s because it is a slower and certainly more ‘painful’ process.

One striking element of the hotel is your decision to replace the TVs in every room with a copy of Zorba the Greek by Nikos Kazantzakis.

I did but people kept taking them. I bought three hundred copies and then I stopped. The TVs are still gone, but so are the books. The idea remains. The idea always remains.

Why did you choose that book? What does it mean to you?

Perhaps it’s not that well known nowadays, but Zorba the Greek was once a major phenomenon. In the 1960s, the film radically changed the way the world saw Greece. It became iconic, like that picture of Jane Fonda, where the name Red Jane Bakery comes from. Never before had someone so popular sat on the enemy’s tank for a photo. It marked a before and after. There was a clean break. The same goes for Zorba. It became the name given to every Greek person.

Do you think it has become a stereotype?

Maybe. But it is interesting that the book’s set here on Kríti. The film won an Oscar. Michael Cacoyannis was an extraordinary director and the cinematographer was amazing too. Walter Lassally, his name was. After making that film, he fell in love with the island. He bought a house and lived here for the rest of his life. Bottom line: I had to choose a book and it had to be that one.

Absolutely. Ammos isn’t your only baby, though. Just last year you opened Red Jane Bakery, where we are now. The internet claims it was “love at first sight”.

I saw this building years ago and immediately fell in love. I wanted to buy it, but they wouldn’t sell it to me. They changed their minds four years later. It was a workshop back then and I bought it without knowing what I was going to do with it. The building is from the 1930s and was built by an immigrant family fleeing the war in Turkey. But it’s not like I was looking for a place to set up a bakery.

So why did you buy it?

It just happened. We were famous for our spectacular breakfast buffet at the hotel. Then Covid came along, and we had to stop the buffet format and serve instead. I decided that home-baked bread and croissants would make up for this change. That is where the bakery idea came from. Since we were already baking, I thought two or three more people would suffice—I didn’t realise it would take twenty.

We know that the name Red Jane refers to the scandal that engulfed Jane Fonda following a photo taken in Vietnam during the war. Why did you choose to call it that?

It was a name I had been carrying around for some time. I liked the sound and I liked the meaning. I always thought that if I opened a new place I would call it that, and I did. I mainly chose it for the story. Jane Fonda going to Vietnam and having her picture taken on the enemy tank… She was labelled as a traitor, but I’m fascinated by the concept of betrayal.

Do you think Red Jane Bakery is a betrayal of your country in some way?

Yes and no.

Perhaps differentiation is a better term?

I don’t know. There is certainly some outside influence in the menu choices and whimsy in the architecture, but I think it’s more of a general concept. At first, I just wanted to call it that without telling anyone the story behind it. Then the story came out.

An avant-garde bakery, but equally a temple of contemporary design. How did the collaboration with Michael Anastassiades come about?

He immediately came to mind because he seemed like the perfect person. I proposed that he come and see the place and we work on it together. He immediately got behind the project. We used tiles made especially for the bakery, from

“I have put my whole self into this project: I have travelled, met people, educated myself and eaten to exhaustion. If you open me up, I’m full of carbs. But it was definitely worth it.”

traditional Athenian marble, but in red. Michael also thought long and hard about the light, which is the real star of all his work. He wanted to leave the rest as similar to the original building as possible and the façade has remained identical. But Michael didn’t just take care of the design. He was very active throughout the whole process, in all the choices. We worked on the recipes together too. We ate together, we travelled together. He even designed the logo. There is only one thing he didn’t design and that is the bench we are sitting on.

Moving on to the menu you created with advice from Eyal Schwartz, co-founder of the iconic e5 Bakehouse in London. How does the Cretan culinary tradition fit into a menu with such a contemporary and international mood?

Kríti doesn’t actually have a great pastry or bakery tradition. We have paximadi, a dry bread made from barley.

Is that the bread used for dakos [a traditional Cretan dish, similar to bruschetta, seasoned with tomato, oil, salt, oregano and feta]?

That’s right. When I decided to do the bakery, I didn’t want to offer things that already existed here with no room for improvement. That’s why we developed different techniques. At most, we try to interpret a few Greek ingredients in the Nordic tradition, so that people can get to know it here as well.

Have you ever thought about living anywhere other than Kríti?

I have thought about it all my life, but now I am too old. In the end, it was a matter of pure chance. If it hadn’t been for the hotel, I would have gone abroad to study and I would be doing something different.

What did you want to do?

Film. I did that for a while, but it didn’t work out. Before that, I studied political science. The fact is, you can’t do everything. You can’t live too many lives.

Plans for the future? Are you already thinking about your next ‘baby’?

Yes, actually. I’m opening a new place right near here. It’s another building, this time from the 1950s. We’ll open a wine shop selling bottles and glasses of wine. I’ve also taken the land next door to make a garden.

Will you be going with the natural wine trend?

I like natural wine, but Greece is still a little limited in terms of natural options. I won’t exclude good wines just because they are not natural.

And what about the garden?

It will be designed by Helli Pangalou, who has recently overseen a really interesting project for the Greek National Opera in Athens.

What will the place be called?

Garten, German for “garden” and also “courtyard”. People will be able to have a glass of wine and something to eat.

Will you collaborate with any acclaimed designers as you did with Red Jane?

No, it will be designed by me and my friend Alexia Mylonogianni. I don't want to repeat myself. Red Jane was already a challenge. It was an act of vanity.

Do you think people understand all the work that went into this project?

I think they do. Not just the design, but also the atmosphere, which I think is the essence of design. Also the quality of the food. If the bread is bad, I don’t care how good the place looks. It is so much more than that. I have put my whole self into this project: I have travelled, met people, educated myself and eaten to exhaustion. If you open me up, I’m full of carbs. But it was definitely worth it.

If there is an island where traditions never go out of fashion, it is Kríti. Here, every village has its own festival, and every festival its own language. No one would ever admit that they all look alike; it is the assumption of superiority that galvanises each village. The sound of the lyre, the folk dances, the inebriating euphoria—just some of the many ways to remember and celebrate, with symbolic theatricality, the recurrence of something. They serve equally to trace the contours of a certain world, elsewhere on the verge of extinction. A distinctive dress code can also be found amidst these myriad different customs that are somehow all the same, purely Byzantine in inspiration. Sweeping dresses with balloon sleeves; black waistcoats with gold decorations and red belts; boots and aprons... Every outfit tells a story. Sometimes it’s the story of the person who once wore it, sometimes it’s the story of a person who will wear it, broken up by a printed T-shirt or a pair of sneakers. But that’s just how Kríti is: the obstinacy of the ancient world collides with the zest of modern life. The result? A stratification of cultures where every existence finds its place.

CRETAN COSTUMES

Little Johns

Eltha Yiakoumaki is no ordinary teacher. Born and raised in Chanià, she studied to become a preschool teacher in Thessaloniki before opening her own nursery in 2006. Traditional education always felt suffocating to her, so in 2021, she chose to take a freer path. After years of experimentation, she devised a way to combine her passion for art with an unconventional educational approach that brings out the individuality of each child. She achieves this with the help of the big names in art history, introducing her young students to these figures through themed workshops. Once a week, for a few hours, she gathers groups of children aged four to nine to explore the world of different artists. She begins by showing them the artist’s works and telling them about the life of the quirky creator. Next, she selects the most powerful images and draws their outlines. Finally, she explains the rules in theory and then allows the children to break them freely.

Artemis Christos Katrina Dimitra Marina

Work inspired by John Craxton, Cockerel and Cat, 1957

Work inspired by John Craxton, Hotel by the Sea, 1946

Work inspired by John Craxton, Head of a Goat, 1948

Had John Craxton and Eltha Yiakoumaki ever met, they probably would have got on like a house on fire. That is why Eltha chooses him for a special workshop, in homage to the island where they are both performers and guardians: Kríti. While her love for the island is a childhood gift, Craxton’s was a belated discovery, resulting from one of his many trips to escape London. Born in 1922 into a family of musicians, Craxton’s artistic career led him far from bustling city life in search of landscapes that resonated with his own. He chose Kríti for its scenery, which restored harmony to his angular compositions. It was here that he realised that life is the highest form of art and that often there is no difference between the two. Thanks to Kríti, Craxton grasped the ultimate value of experience, which goes far beyond its representation.

Today, many little Johns, guided by Eltha’s audacity, discover that this experience can transcend reality when viewed through the filter of art.

Manos is from Irákleio and studies political science in Athens. His dream is to be a filmmaker, though he fears his father’s judgement. Every summer, he returns to Kríti to enjoy the sea and tranquillity of the island.

Anna was born in Irákleio but splits her time between Athens and Thessaloniki. Before discovering acting, she wanted to become a marine biologist. In her spare time, she is a DJ but her favourite thing about Kríti is the silence.

Georgios is Greek and his wife, Carol, is Irish. Thirteen years ago, their love brought them to Kríti. Their eldest son, Evangelos, was born in Dublin but moved to Irákleio with his family when he was one. Patrick and Tristan, aged 12 and 10, are from here but have a special bond with Ireland.

On Kríti, every rock hides a story, shaped by the winds and the deeds of ancient gods. On Ligres beach, some know these rocks by heart and check that none are missing from the roll call every morning. The sea, as we know, often kidnaps pieces of land and takes them far away.

Pelotas Ariel F/W 2024

Alexia was born in a small town near Manchester but grew up in Irákleio. With an English mum and a Greek dad, she feels Cretan but isn’t a fan of the sun. After studying politics and sociology in Athens, she returned to Krìti to be surrounded by nature.

Melina is a computer scientist who works in a bar in the evenings. This is her favourite time because she comes into contact with people—instead of computers. She likes the nature on Kríti, but there just isn’t enough of it in Irákleio, where she lives.

Manolis is the 20-year-old son of Konstantinos, the founder of Minoan Pottery, and is learning his father’s trade. Like the rest of his family, he loves cats and cares for the ones that live on their farm. The kittens wander around the pottery, making the huge ceramics look even bigger.

Katia is 17 years old and attends secondary school—everyone goes to the same one here. She lives in Irákleio where she dances, hoping to turn her great passion into a profession. When not dancing, she goes to the sea, where she finds the peace that adolescence sometimes steals away.

Brand Creative Director

Achilles Ion Gabriel

Brand Director

Gloria Rodríguez

Photography

Maxime Imbert

Styling Francesca Izzi

Illustrations

Francesca Albergo

Copywriting

Robin Sara Stauder

Production Hotel Production

Special thanks to Emmanuelis Angelakis

Christos Bairabas

Alex Brack

Eva Grimm – Cretan Folk Art and Antiques Gallery

Konstantinos Houlakis – Minoan Pottery

Guillaume Mercier

Nivritos Cultural Association

Oloapitreps

Ioannis Papadakis

Arianna Sesia

Sorry Mummy

Evelina Evangelia Stoltidou

Studio Levi

Universo Maglia

Image Credits

© Maxime Imbert

© Fele La Franca, video stills: pp. 80-85

© Iliana Malihin p. 41

© Heraklion Archaeological Museum pp. 116-121

Print House

Artes Gráficas Palermo, Madrid

ISSN: 2660-8758

Legal Deposit: PM 0911-2021

Printed in Spain

Alcudia Design S.L.U. Mallorca

camper.com

© Camper, 2024 Join The Walking Society