Navigating geo-politicsina crisis

In the dark: First casualty involving a dark ship fuels concerns

l Dragging anchors: Anchor snagging creating claims

l Illegal migration: Risk of stowaways rears again

l ChatGBT: How will the shipping sector manage AI?

l Seafarer arrests: Seafarers used as pawns in US

l Compliance: Making sure the ISM is adhered to

Marine Cargo

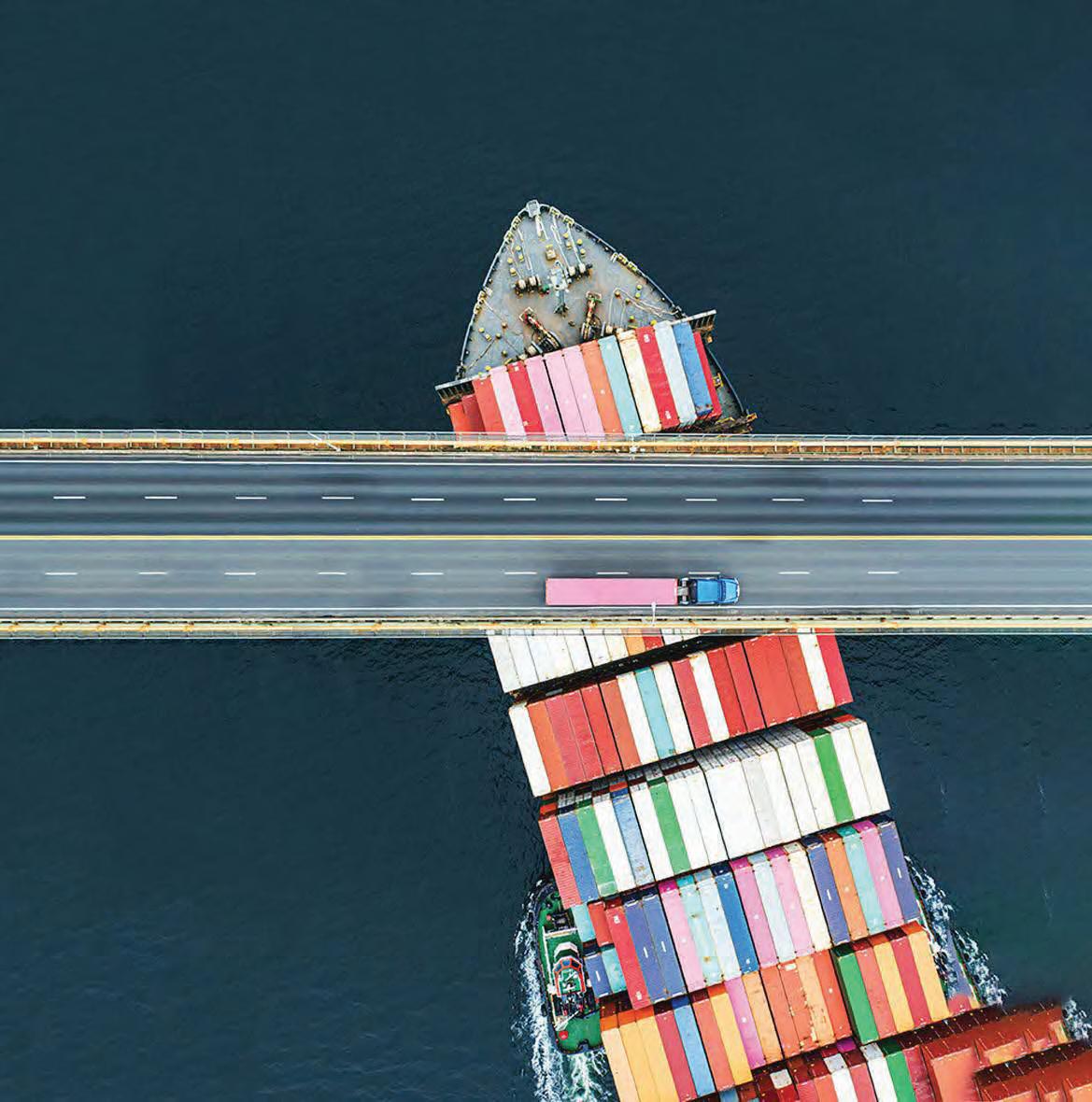

Navigating dynamic risk

The AXIS Marine Cargo team offers global insurance solutions that span the entire supply chain process.

Our specialist expertise in marine cargo enables us to create bespoke coverage for a wide range of industry sectors from the small to the largest, most complex risk.*

Scan here to find out more

In the United Kingdom, risks are underwritten by AXIS Managing Agency Ltd (“AMAL”) on behalf of Syndicate 1686 or by AXIS Specialty Europe SE (London Branch) (“ASE London Branch”). AMAL is registered in England (Company Number: 08702952) with a registered office at 52 Lime Street, London, EC3M 7AF. AMAL is authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority (Firm Reference Number: 754962). AMAL manages Syndicate 1686 and is additionally subject to the supervision of the Society of Lloyd’s. The Syndicate also benefits from the strength of the Lloyd’s brand, its network of global licenses and the Lloyd’s Chain of Security. ASE London Branch is an overseas branch of AXIS Specialty Europe SE (“ASE”). ASE is registered in Ireland (Registration Number: 353402 SE) at Sixth Floor, 20 Kildare Street, Dublin 2, D02 T3V7, Ireland. ASE is authorised and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. Authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority. Subject to regulation by the Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of ASE’s regulation by the Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. In the European Economic Area, risks are underwritten by AXIS Specialty Europe SE (“ASE”) or by Lloyd’s Insurance Company S.A. (“Lloyd’s Europe”). ASE is registered in Ireland (Registration Number: 353402 SE) at Sixth Floor, 20 Kildare Street, Dublin 2, D02 T3V7, Ireland. ASE is authorised and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. Lloyd’s Europe is a subsidiary of Lloyd’s and is authorised by the National Bank of Belgium (NBB).

*Coverage may not be available in all jurisdictions. Issuance of coverage is subject to underwriting criteria, and coverage depends upon the actual facts of each case and the terms, conditions and exclusions of each individual policy. Minimum premiums may apply.

NAVIGATING GEO-POLITICS IN A CRISIS

Global disruption?

WE GAVE this issue the theme of global disruption, with a question mark, quite deliberately as we wanted to see what was really worrying our contributors. And as you will see from the following pages, there is plenty of disruption to the marine insurance market.

But also, as we had anticipated, not everything is bad. The advancements in technology, for example, should pave the way for a cleaner and more efficient marine industry. One in which seafarers lives are less at risk and one in which vessels can ply their trade with less harm to the environment.

Technology will also enable the marine insurance sector to work smarter and more efficiently from pricing of risks to claims handling and monitoring – all positive stuff.

Sadly, however, there are plenty of less positive disruptions. The war in Ukraine continues to take its toll on the marine sector, although not necessarily in the most obvious of ways. This war has produced the new phenomena of dark ships – not new in themselves but new in that vessels are sailing after switching off the automatic identification systems that protect both them and others from collisions or groundings.

Many in the industry fear the consequences should one of these dark vessels collide with a law-abiding vessel or have an accident that results in massive pollution. Where will the liability fall and how can the marine market react to such an event? These questions were hypothetical until early May but now many are holding their breath and hoping for resolution in Ukraine before such an event becomes a major catasrophe.

Some global disruptions are hardly new – the world is too well used to geopolitical upheaval. It is just a matter of changing geographies rather than new threats. But there does seem to be a new world order emerging and only time will tell whether the axis of Russia, China and India does develop further to make a difference.

Another old problem that has reared its ugly head again in recent times is that of stowaways. As economic turmoil hits many emerging markets worldwide, it seems the stream of illegal immigrants is flowing that much faster – and with climate change threatening many poorer parts of the world too, that flow of stowaways is predicted to get that much worse.

So it seems we are faced with both good and bad when it comes to global disruption – something to keep everyone on their toes in the coming months.

Liz Booth Editor, The Marine InsurerUnintended consequences

On 2 May 2023 the Gabon flagged Aframax tanker Pablo lying at anchor off the coast of Malaysia suffered a catastrophic explosion. Three of the 25 crew are still missing. Thankfully the 1997 built vessel was in ballast at the time and a major oil spill averted. The vessel had recently been fixed to load a cargo of crude from Singapore.

Rightly such incidents will always attract headlines particularly when sections of the deck are filmed flying through the air from the force of the explosion by crew from another vessel at anchor nearby.

But this incident is also serving to shine a spotlight on an area of growing concern to mainstream shipping and regulators. Specifically, the Pablo is part of the so called shadow or dark fleet – vessels flagged, classed and insured in jurisdictions that do not recognise economic sanctions imposed on countries such as Iran, Venezuela and Russia and which provide little or no regulatory oversight on the vessel’s operations and insurance cover.

Quite simply the Pablo was an accident waiting to happen – and it could have been so much worse.

Over the four years prior to the explosion, the vessel had had four different names, was flagged in four separate countries and had had four different owners. It transferred to the Gabon flag only days before the incident. Its liability insurer is still not known. It was known to regularly carry Iranian oil.

The Pablo is but one of a growing number of vessels employed to carry cargoes subject to EU/ G7 sanctions.

RAPID EXPANSION

Estimates vary as to the numbers of vessels engaged in this trade but

as of April 2023 industry analysts estimated that the shadow fleet comprised of somewhere between 500 and 1,000 vessels. This fleet has grown rapidly in 2023 – in all probability because of the introduction of the Russian Oil Price Cap by the EU/G7 group of nations – and is continuing to grow.

The priority for these vessels is not to make money for their owners but to transport sanctioned cargoes. As such they do not need to be operated and maintained to commercially recognised safety standards and the insurance will be placed in markets that may lack the necessary financial coverage to pay for large claims and the experienced claims team to deal with them.

In April a spot check revealed over twenty tankers of greater than 50,000gt transiting the Baltic on a single day having all loaded cargoes of Russian oil at Primorsk. This trade threatens all of us. The Pablo could have exploded and spilled its cargo in the Baltic or the North Sea or off Singapore.

But, the problem is not limited to the shadow fleet because it is not just the deliberate sanctions breaker that may find itself uninsured.

Western maritime sanctions programmes are predicated on the mistaken belief that access to insurance cover is an enabler of unlawful trades and that by requiring an insurer to withhold or cancel cover, owners will be discouraged from engaging in such trades.

Mike Salthouse , Head of External Affairs, NorthStandard, says that the rise of the shadow fleet to evade Russian oil sanctions is becoming a serious problem that is not simple to solve and has wide impacts

DUPED INTO CARRYING

The flaw in this premise is that many of the vessels caught with sanctioned cargo on board have done their best – exercised due diligence – to avoid carrying such cargoes but notwithstanding those efforts are nevertheless duped into loading a sanctioned cargo.

Insurers, banks, flag state and class then withdraw their services leaving the vessel adrift, without insurance cover or access to its usual banking services and with a cargo it cannot discharge. If an accident happens at that point, in all likelihood, no one will respond.

As a result of lobbying by the International Group of P&I clubs in the run up to the introduction of the Russian Oil Price Cap an exceptional allowance has been made for the provision of insurance in the case of an emergency. This permits insurers to respond to liabilities that arise under conventions such as the Civil Liability Convention or Bunkers Convention.

However, that exception remains unique to the Russian Oil Price Cap legislation. No such exceptions apply to vessels loaded with Syrian, Venezuelan or Iranian oil cargoes.

SOPHISTICATED EVASION

Over the years sanctions evasion has become more sophisticated. It is now very difficult for the average shipowner to determine whether a cargo is lawful. This increases the likelihood of the

innocent vessel owner being caught out.

The Russian Oil Price Cap scheme requires owners and charterers to verify the price paid for the cargo by requiring their charterer to provide an attestation before loading that confirms that the cargo was sold at a price that did not exceed the Cap.

However, the shipowner has no real means of determining whether that attestation is correct. And if the cargo is sold on board the vessel during the voyage, then no amount of due diligence on the part of the owner can prevent that breach and the subsequent cancellation of the vessel’s insurance.

A few years ago, a North entered vessel trying to enter the port of Singapore to discharge a cargo of oil experienced just this problem. It was denied access by the port agent who had received a tip off from the US embassy that the cargo was of Iranian origin. It had loaded the cargo from a vessel off Malaysia. When the Club checked back using specialist tracking software there was nothing to link the cargo to Iran; and yet given the source of the allegation insurers and banks had no choice but to withdraw their services, leaving the vessel uninsured and idle in one of the world’s busiest waterways.

Eventually the vessel was able to transfer the cargo back to the vessel from which it had loaded, and cover was reinstated. But the solution for this vessel was simply to transfer the problem to another ship.

It may be that the Pablo will serve to draw attention to this issue. I hope so because it is in no one’s interest to have fully laden tankers lying idle, without insurance and with no means of discharging the sanctioned cargo. This is a growing problem and, as others have noted, the ever-increasing number of ships that comprise the shadow fleet have no interest in meeting shipping’s other great challenge – the reduction in greenhouse gases.

“Estimates vary as to the numbers of vessels engaged in this trade but as of April 2023 industry analysts estimated that the shadow fleet comprised of somewhere between 500 and 1,000 vessels. This fleet has grown rapidly in 2023 in all probability because of the introduction of the Russian Oil Price Cap by the EU/G7 group of nations – and is continuing to grow.’’Smoke pours from the tanker MT Pablo after it caught fire off Malaysia’s southern coast during a journey from China to Venezuela. Photo: MMEA

Cargo Insurance London

21st March 2024

NEWfor2024

Cargo Insurance London is a new conference taking place on the 21 March 2024. Traditionally, our cargo content was focused solely on seaborne transportation. This event is geared to be an accessible and dedicated one-day global cargo insurance conference in the City of London focusing on all aspects of the cargo transportation

Navigating geopolitics in a crisis

The maritime industry is international by its nature and has played an indispensable role in improving lives and living standards by moving goods around the world. Nation states have long been beneficiaries of international trade, but that success has largely been built upon free trade and cooperation between states.

In recent years, rising geopolitical tensions and outright conflict have been reflected in momentous changes in trading patterns.

The war in Ukraine has brought upheaval to energy markets and limited the exports of foodstuffs from Ukraine, one of the world’s largest exporters of grain. Tensions between China and the US over Taiwan are felt by a wide range of industries reliant on Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturing.

SOURED RELATIONS

The souring of international relations and re-emergence of politically aligned blocs has visible impacts on trade flows, but also creates an immeasurable risk to the safety of the environment, vessels, and their crews.

These are factors that often remain overlooked even as governments and the maritime industry seek to advance ambitious goals of environmental conservation, decarbonisation and greener operations across global supply chains.

The growth of the dark fleet in the tanker sector, in response to international sanctions and the consequential deterioration of Venezuela’s tanker fleet, is a catastrophe in-waiting.

Ageing vessels with the capacity to cause untold environmental damage have been pushed beyond the reach of the regulations, inspection regimes we rely on to prevent disaster, and insurance coverage should the unthinkable happen.

In the Black Sea region, a UN-brokered deal has allowed grain to flow out of Ukraine under an inspection regime that brings together Ukraine, Russia, Türkiye and the UN to clear incoming and outgoing vessels and cargoes for export.

After intense negotiations the deal has once again been extended for 60 days. But, the uncertainty was a stark reminder of how international shipping, and the food security it enables, is at the mercy of geopolitics and diplomacy.

What’s more, when an incident arises, an efficient salvage operation relies on co-operation and co-ordination between an astoundingly long list of stakeholders. Unfettered access to necessary data and information, as well as transparency and trust between those involved is crucial.

It is an unfortunate fact that geopolitics can muddy all of these criteria for success which, in the salvage industry, means the protection of property and the environment.

EMERGENCY IN A CRISIS

What if, in the midst of the negotiations to renew the Black Sea Grain Initiative, a vessel had run aground in the Black Sea, or a fire had broken out on a vessel transiting the grain corridor?

Getting a salvage tug or properly equipped, specialised vessel to an incident in such a hotspot would require a significant diplomatic effort that would inevitably hinder time critical incident response. Depending where in the world an incident occurs, there may also be added insurance considerations or the restrictive reach of sanctions which could have an impact on access and operations.

Beyond the equipment itself, specialists and experts must often be brought in to help deal with a situation or emergency. International tensions can significantly delay the arrival of operations experts when time is of the essence. All the while we must be mindful of our duty of care to our crews, staff, and contractors and do our utmost to ensure their safety and wellbeing.

This encompasses risks arising from challenges inherent in marine salvage operations, like hazardous tasks, remote locations, harsh weather and ever-larger vessels, and complying with complex international regulations, as well as possible risks resulting from geopolitical matters.

As trust between nations erodes, the ability of salvors to respond to crises quickly and effectively is impacted as well. Ship casualties do not adhere to national borders and territorial waters, and their potential impacts do not respect the current geopolitical mood.

A vessel in distress off one country’s coastline may be only a change in the wind away from becoming its neighbour’s problem, and the same applies doubly to pollution from cargo and oil spills.

Mitigating impact is not merely a priority for the stakeholders involved, but, has knock-on effects across the supply chain for the global community when it comes to preserving

Geopolitical challenges, such as war and sanctions, add an extra layer of complexity to salvage operations. While increasing regional tensions make salvage challenging in the short term, ensuring we act promptly to reduce environmental impact remains key, writes Amanda Drinkwater from Marine Masters

the marine environment.

Prompt and responsible salvage operations are not simply the unfortunate end point of an incident, but, also a key impact point for ensuring minimal long-term effects for shipping operations and our planet.

MITIGATION AND RESOLUTION

While the ideal way to resolve the impact of geopolitical influence on the maritime industry is diplomacy, the reality is that this can be an arduous and unpredictable process with an extended timeline before outcomes are realised. As a result, salvage often has to be agile and flexible, and able to respond to the circumstances at hand.

For example, our own team at Marine Masters have adopted a pragmatic approach to operations that forestalls delayed actions and often assists us in mitigating environmental impact. For instance, the flexibility to employ alternative methods can reduce the area and number of nations from which equipment must be drawn.

We have used this customised approach when heavy lifting equipment would prove too costly, opting to use locally-sourced barge and winch solutions and/or pressurising tanks and void spaces instead of mobilising heavy lift gear.

This delivers cost-effective solutions, and since the necessary equipment is readily available in most countries, it also ensures a timely response that is not dependent on the goodwill or risk tolerance of other states.

Local contractors and suppliers are often invaluable sources of support during a tight timeline. Our understanding of this vital contribution is reflected not only in our ethos of sourcing personnel and equipment from local contractors and suppliers wherever possible, but also in our company’s commitments to ESG.

In circumstances where a specificity of knowledge and experience is key, we have a global network of contractors who are able to work effectively with local incident responders.

Working in tandem with local entities also helps to build and/or reinforce local expertise — a key component of maritime’s goal of a just transition. This offers significant benefits to the industry as a whole, as well as upskilling and equipping the local economy for the future.

UPCOMING CHALLENGES

A softer method of mitigating the complexities of geopolitics is leading by example in our work. We work with, and rely on, contractors the world over and cooperation and transparency underpins these relationships. By fostering and encouraging collaboration and understanding—whether it be between governments, companies, industry associations or other stakeholders—we help to create the professional relationships and mutual respect that

ultimately benefit the job at hand.

When acting at a policy level for national and international activities, collaboration has the potential to speed up the flow of information and clarify the frameworks we operate within – and of course, to allow for a coordinated response to incidents whenever possible. It is the bedrock upon which our global industry is built.

In the future, decarbonisation of the shipping industry, with attendant new fuels and cargoes, will impact on the risks involved in operating and salvaging vessels. A lithium-ion battery fire on a vessel is a potential catastrophe on its own. How is that situation changed if the vessel is ammonia-powered? Or methanol-powered? What are the risks to crew and salvage teams if there are tanks of liquefied captured carbon onboard?

There are so many changes coming to the industry in the coming years and decades that we cannot afford for safety-critical knowledge to end up siloed in individual companies, countries or geopolitical power blocs. At a time when international co-operation is showing signs of seizing up, collaboration is the grease that keeps the wheels of global trade moving.

“The war in Ukraine has brought upheaval to energy markets and limited the exports of foodstuffs from Ukraine, one of the world’s largest exporters of grain.”

Amanda Drinkwater, MarineMasters

At the end of 2019, and as the world was looking into the new decade, there was anticipation that we could be moving into a new “Roaring” or“Golden Twenties”. With rapid inflation, instability in the currency markets and growing global discontent, the socio-political climate is perhaps more akin to 1929, than the decade that preceded it.

The World Economic Forum published an article in July 2022 entitled “Why are supply chains facing disruptions and how long will they last?” Global disruption has perhaps been the overriding factor in this decade thus far, with the obvious drivers of the global pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

With these global events alone affecting the free flow of materials and products, the knock-on effect has created a supply chain disruption that, in itself, has put increased pressure on supply.

This result has led to an increased demand as the world has exited a pandemic at a time of disrupted supply, resulting in predictable cost and price volatility.

COMMODITY PRICES

The combined varying cost of commodities is an oftenquoted indicator of global inflation. A quick summary of a select few relevant materials’ estimated average inflationary prices from March 2020 to March 2023 are:

> Steel (the principal material used in most modern marine and offshore assets) seeing an increase of circa 30%;

> Copper price inflation resulting in a circa 96% increase;

> lead at a 27% increase;

> WTI crude oil experiencing a gross inflation of 310% from circa US$ 25 per barrel; and

> Natural gas seeing a 72% increase, albeit from an artificial low during the early days of the pandemic. There are clearly complicated and varying reasons behind inflationary prices. It is beyond the scope of this article to separate trading speculation and demand, but there is enough commentary to suggest the global markets are in a situation that would have been deemed unprecedented before the start of the decade.

The start of 2020’s came head-to-head with a global pandemic and, as the world was emerging from that initial disruption, the Russo-Ukraine war. Both contributed to the economy in which we now find ourselves.

Is lingering disruption driving the cost of offshore claims?

Lily Yates and Jim Clark , of MatthewsDaniel look at how the prolonged disruption of the global pandemic and the Ukraine conflict has affected the cost of offshore claims

SOBERING ANALYSIS

This ultimately provides a backdrop for a sobering analysis when it comes to reviewing marine and energy repairs, costs and, subsequently, claims.

The global cost of materials has a direct impact on damage repairs, equipment procurement, and replacement – impacting the costs of claims.

Marine and offshore energy activities provide a decent bellwether, because of the global nature of both industries meaning they have a particular sensitivity to cost fluctuations on the global markets.

Reuters reported in May 2023 that the US supply chain is |potentially healing from “early pandemic shocks that sent shipping costs sky rocketing and squeezed supplies of everything from toilet paper to pasta...”, although material and labour cost increases linger.

MatthewsDaniel has seen an escalation in cost and claims across the marine and offshore energy sectors. A breakdown of the cost increases on specific offshore claims has seen circa 20% increase in materials, circa 35% increase on labour costs and another 35% on energy consumed during fabrication and fuel on installation.

These cost increases have the potential to take the assured and the insurer by surprise, with the increase in repair and replacement costs often outstripping any annual increases in declared values.

Offshore vessel rate increases seem to have principally been

driven by a trio of factors. The first two being a direct result of global disruption with fuel costs rising and the maritime labour market heating up. Reports of seafarers leaving the industry after the uncertainty and unique sacrifices as well as the isolation experienced by ships crew during the pandemic years. This combination of factors has led to a decrease in the skilled workforce available in the maritime labour market, further exacerbating delays. The third factor is perhaps a secondary knock-on effect from the rising costs of energy, which has seen increased demand for specialist offshore vessels.

As offshore energy companies have looked to engage and take advantage in a suddenly buoyant energy market market, with a quickening of the drive into offshore renewables oil, gas and renewables operators are now often competing for the same vessels with offshore wind infrastructure now larger, deeper and looking towards floating.

DELAYED REPAIRS

In the event of a claim, (and outside the question of escalating values, underinsurance and application of an average clause, rarely seen in marine or energy policies), cost increases become most contentious where repairs have been delayed for months or years including ongoing cases from the pandemic. This has an effect on cost and claim escalation.

The delay of repairs is often undertaken for very valid reasons, but disruption in recent years has made bench marking claims costs, assessing potential claim escalation, the potential blurring of the line between escalation due to delay and expediting expenses, particularly challenging.

Although disruption can be positive or negative, in this context at least, it is hard to imagine why anyone would hope for a continuation of the disruption the world has seen throughout the first third of this decade. However, the scene has been set for demand to continue to grow in the offshore sector, with the continued rise of renewables looking to increasingly draw raw materials and labour into the offshore sector.

As global disruption hopefully eases as we enter the middle of the decade, even if costs and subsequent claims continue to rise, one would hope that at least this will occur in an environment where the global movement of goods and services are predictable, ‘economic coercion’ is limited, costs can be accurately estimated, repairs can be conducted at an opportunity as chosen by the interested parties and the wider expectation on values and costs is realistic.

“Offshore energy companies have looked to engage and take advantage in a suddenly buoyant energy market. This has led to a quickening of the drive-in offshore renewables and both oil and gas and renewables now often competing for the same vessels with offshore wind infrastructure now larger, deeper and looking towards floating.’’

This year’s Marine Claims International event will once again take place at The Grand Hotel in Malahide, Dublin. The event was SOLD OUT in 2022 and is set to sell out again for 2023. This all-inclusive, three-day residential event will bring together the key players in the global marine claims sector to discuss the market landscape and take an in-depth look at the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for 2024 and beyond.

To find out more contact Daniel Creasey on +44 (0)7702 835 831 or email daniel@cannonevents.com

www.marineclaimsinternational.com

DAY ONE

28th September 2023

09.02-09.45: PANEL DISCUSSION: How is the Market Shaping Up?

09.45-10.05: PRESENTATION: Buyer Beware, or is it Insurer Beware?

10.05-10.30: INTERVIEW: Our Friend in Ukraine – Taking the Longer-Term View

Arthur Nitsevych, Partner, Interlegal

11.00-11.20: PRESENTATION: Working in the Shadows – The Dark Fleet

Ruby Hassan, AVP, Claims Knowledge Management and Digital Development, Skuld

11.20-11.40: PRESENTATION:

The US – Judge, Jury and Executioner?

George M. Chalos, Partner, Chalos & Co, P.C. - International Law Firm

11.40-12.00: PRESENTATION: Make your Claim ‘Reinsurance Ready’

Anthony Menzies, Partner, DAC Beachcroft LLP

13.00-13.45: PANEL DISCUSSION: Who’s to Blame for Engine Room Claims?

John Poulson, Director and Chief Surveyor, Poulson Marine, Helene Peter-Davies, Partner, Hill Dickinson LLP

13.45-14.00: PRESENTATION: Planning a Different Approach – The Nordic Plan?

Herman Steen, Partner, Wikborg Rein Advokatfirma AS

14.00-14.50: PANEL DISCUSSION: Would the Nordic Approach Work in London?

Joseph Shead, Average Adjuster, Aon, Melis Otmar, Marine Claims Director, BMS Harris & Dixon Marine

15.35-15.55: PRESENTATION: In the Courts – Climate Change Litigation on the Rise

J. Clifton Hall III, Partner, Hall Maines Lugrin

15.55-16.15: PRESENTATION: Know Your Enemy – Climate Activists at Work

16.15-17.10: PANEL DISCUSSION: Where are the Claims? Part II…

Francesco Zolezzi, Claims Manager, CR International

DAY TWO

29th September 2023

09.00-09.30: PRESENTATION: From the Courts – The Most Recent Cases Explored

Richard Sarll, Barrister, 7 King’s Bench Walk

09.30-10.00: PRESENTATION: Ship Master or Drug Mule? The Risk of the Unexpected Cargo

Simon Jackson, Partner, Clyde & Co

10.00-10.50: PANEL DISCUSSION: Bite-Sized – From Casualties to Talent

Amy Dallaway, Claims Manager, Lancashire Group

11.20-11.40: PRESENTATION: Salvage –Not in That Backyard

11.40-12.00: PRESENTATION: LOF Update. What’s Next?

Ben Harris, Head of Claims- London Branch, Shipowners’ Club

12.00-12.20: PRESENTATION: Making the Right Fuel Choice – The Salvage View

Henk Smith, Consultant, Marine Masters

12.20-13.00: PANEL DISCUSSION: General Average – Does it Remain Fit for Purpose?

David Richards, Deputy Global Head of P&I Claims/Head of Legal and Expertise, NorthStandard

WORKSHOPS

PRESENTATION: Fitting the E-Bill

PRESENTATION: Maintaining the Principles – Ready to Foot the Bill?

PRESENTATION: Ferrying the Batteries

PRESENTATION: Overboard – Cargo Going Missing

PRESENTATION: Can you Insure Something you do not Own?

Peter MacDonald Eggers KC, Barrister, 7 King’s Bench Walk

Oil spill Russian Roulette on the high seas

Charles Cormack , Intelligence Analyst at SynMax, analyses the growing problem of dark ship-to ship transfers caused by the sanctions imposed on the export of Russian oil

CHANGING WORLD

It cannot be said that Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine in early 2022 has gone entirely to plan, severely affecting Russia, its interests on the battlefield and its position within the international community.

While the West and NATO cannot be seen to be involved militarily, the US and the European Union have imposed biting sanctions upon Russia in an attempt to reduce its economic ability to wage war.

Included is a maximum price cap, imposed by the G7, of $60 per barrel on oil, by far Russia’s most lucrative export, and a ban on seaborne crude and refined products entering the EU.

However, because of Russia’s willingness to embrace clandestine networks and non-legal avenues, it cannot yet be claimed that sanctions have entirely guaranteed that either the price cap is adhered to or total oil exports reduced.

Using dark vessels to transport energy products was, until recently, a fringe activity carried out by Iran and Venezuela to avoid Western sanctions.

Since the invasion, however, Russia has incentivised and aided the emergence of a massive fleet of obscurely owned, dubiously insured and creatively registered dark oil tankers.

By subverting international shipping regulations and procedures, Russia has returned its oil export capacity to pre-invasion levels. In March 2023, Russia’s oil exports were the highest since April 2020.

TRICKS OF THE TRADE

In March 2023, it was estimated that there were 440 dark tankers above 30,000 dwt tonnes globally, an increase of 180 in the past year, accounting for 10% of all large tankers.

Two of the most commonly employed tricks of the dark shipper’s trade are automatic identification system (AIS) spoofing and ship-to-ship (STS) transfers.

Created to aid collision avoidance, AIS is a requirement by

the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for commercial vessels of more than 30 meters.

It regularly transmits navigational data, including a vessel’s identity, position, course, speed and destination, and as a by-product gives interested parties an oversight of light vessel’s movements and behaviours.

Spoofing works in a similar fashion to masking an internet connection by using a VPN, synthetically projecting a vessel’s location to create a digital alibi and allow a semblance of plausible deniability.

Theia, SynMax’s ground-breaking maritime domain intelligence product, is the only at-scale solution to AIS spoofing. Theia combines the evidential proof of satellite imagery with the scalability of machine learning and artificial intelligence, allowing for automatic identification, attribution and analysis of any vessel of more than 30 meters, light or dark, spoofing or not spoofing (see Image 1).

SHIP-TO-SHIP TRANSFERS

That a vessel engages in STS transfers is not deceptive behaviour. STS transfers can be a legitimate way of moving oil, cargo, fuel, supplies or personnel between vessels without entering a port setting. In doing so, they can avoid fees, bureaucracy and the size limitations imposed by port infrastructure.

However, the benefits of STS transfers are not limited to legal activities alone.; increasingly, they are used to obfuscate the origins of sanctioned oil. Particularly useful if, for example, you wanted to sell Russian oil in the EU or for more than $60 a barrel.

To ensure minimal risk of cargo spillage or damage to vessels, innocent transfers overwhelmingly take place in sheltered, territorial waters.

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) requires vessels engaging in STS transfers within territorial waters to notify coastal authorities 48 hours in advance. Thus, if an accident were to take place, help could be immediately at hand and environmental damage minimized.

Dark vessels collect oil from pariah states, including Iran, Venezuela and Russia, and carry out STS transfers in international waters, hidden from the watchful eye of regulators and port state control (PSC). The IMO referred to the tactic as: “Dangerous practice of ship-to-ship transfers in the open ocean.”

PSC inspections are required by foreign ships arriving in national ports. An essential part of the rules-based international maritime status quo, they act as an audit point, verifying that both vessel and cargo comply with IMO regulations, including MARPOL and safety of life at sea (SOLAS).

Using STS transfers to carry out the bulk of logistical operations has meant below-standard, dark mercenary vessels can carry out a lucrative trade running sanctioned oil without the risk of detention, confiscation, or accountability by states or regulators.

Theia’s high-resolution imagery ensures that dark

vessels engaged in STS transfers on the open ocean are identified automatically and prosecuted if they are found to be lacking the necessary care and precautions. By taking into account changes to a vessel’s draught, oil can be effectively tracked from producer to consumer, making dark STS transfers obsolete.

PANAMA

MARPOL legislation dictates that vessels conducting STS transfers in international waters must notify the flag state with which they are registered. Endemic usage of flags of convenience has meant almost all dark ships are registered with small, undemanding states without the capacity to police vessels sailing under their flag, or that are willing to turn a blind eye to non-legal behaviour.

In November 2022, a leading maritime intelligence provider analyzed 43 large oil tankers anchored off the coast of Malaysia. All were aged 20 years or older and were being used as floating storage tanks - oil halfway houses - used to obscure the link between production in Iran, Venezuela, or Russia and consumers in China.

Of the 43 observed, 24 were flagged in Panama. This is not surprising as an estimated 45% of the dark fleet chooses to register in Panama, thanks to its laissez-faire attitude to policing and legislation enforcement on nationally flagged vessels.

IMO

In March 2023, Australia, Canada, and the US presented a joint submission to the IMO, raising concerns about the growing number of dark ships carrying out STS transfers in the open ocean.

They argued that the changing status quo could be perceived as a move away from the rules-based international order, represented an increased risk of pollution to coastal states and highlighted a lack of liability and compensation legislation in the event of an oil spillage.

The submission stated: “These risky practices unjustly expose national and local governments and authorities to potentially fill the void of paying for response and clean-up costs and compensating victims where no international or domestic compensation fund can do so.”

They called for flag states to take more responsibility in ensuring their tankers adhere to IMO conventions and to demand notification of STS transfers in open waters.

The IMO held its 110th session on open ocean STS transfers and dark shipping tactics at the end of March 2023, and announced that it: “Broadly supported the recommended measures outlined in the original submission.”

They clarified that STS transfers on the high seas were: “High-risk activities that undermined the international regime with respect to maritime safety, environmental

protection and liability and compensation needed to be urgently addressed.”

The IMO Assembly has since announced plans to meet in November 2023 to draft a resolution to go on the offensive against dark shipping and dangerous open-ocean STS transfers.

Theia is the complete tool for regulators, providing actionable intelligence to guarantee legislation is more than an empty threat. By bringing oversight and transparency to millions of square kilometers of open ocean, Theia ensures there is nowhere for bad actors and dark vessels to hide. Theia tracks the entire journey of a vessel and its cargo, making STS transfers, AIS spoofing and other obfuscation tactics used by dark ships obsolete.

“Dark vessels collect oil from pariah states, including Iran, Venezuela and Russia, and carry out STS transfers in international waters, hidden from the watchful eye of regulators and port state control (PSC). The IMO referred to the tactic as: “Dangerous practice of ship-toship transfers in the open ocean.”

GLOBAL PARTNERS:

Now in it's 5th year! Taking place on the 13 October 2023 at etc Venues’ 155 Bishopsgate, the event will focus on upstream oil & gas and have a heavy focus on energy transition and renewables. Energy Insurance London is specifically designed to bring together all the key players in the energy insurance market to discuss, debate and offer actionable insights into the issues affecting the sector.

To find out more contact Daniel Creasey on +44 (0)7702 835 831 or email daniel@cannonevents.com

SPONSORS:

www.energyinsurancelondon.com

Ukraine war raises fresh challenges for shipping in Turkish Straits

Ibrahim Onur Oguzgiray , Senior Associate at Turkish maritime insurance law firm Cavus & Coskunsu explains the latest complications when carrying out trade in the Turkish straits as a result of the ongoing war in Ukraine

The Russia-Ukraine war reminded us how important the strategic trade routes are and how delicate the global trade supply is.

The ongoing armed conflict in the Black Sea region caused massive disruptions in supply of grain that is being exported from Ukraine as well as the oil supply from Russia because of sanctions.

Turkiye is directly affected by the war as the Turkish Straits is the only waterway connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

The Turkish Straits are the main trading route for countries in the Black Sea region where the passages of ships are governed by the Montreux Convention.

This was signed on 20 July, 1936. This convention is not only about the passage of merchant vessels, but, for the purpose of this article, it is important to mention that it also provides free passage to merchant vessels.

Because of the ongoing conflict, Turkiye has introduced several new requirements from tankers and also taken a role to solve the grain supply crisis, both of which have led to increased traffic as well as delays and queues in strait passages.

NEW MEASUREMENT FOR P&I COVERS

Becoming aware of sanctions and issues arising from the insurance cover for vessels trading with Russian ports, on November 16, 2022, the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure released a notification stating that, starting from December 1, 2022 (later extended to December 2, 2022), all vessels transporting crude oil products and passing through or entering Turkish waters are required to present letters of confirmation from their P&I Club.

This should verify that insurance coverage will be maintained under all circumstances during the transit, while the ship is in Turkish waters, or during its time at a port or terminal.

These new requirements were designed to avoid risks arising from sanctions. The notice was challenged by P&I Clubs and liability insurers, stating that the wording of the requested letters would not be acceptable because it would confirm that the P&I cover would remain in place irrespective of any violations of the owners which may grant insurers to cancel or terminate the policies.

Therefore, discussions on the wording of letters caused huge delays and led to queues in the anchorage areas nearby.

After discussions between stakeholders and Turkish state bodies, the parties achieved a consensus on the wording under which the vessels carrying crude oil cargoes were allowed to pass through Turkish waters and the straits.

The requirement to provide the confirmation letter was later extended on 10 February, 2023 to ships over 300gt carrying petroleum products (listed in MARPOL Annex I – Appendix I) through Turkish controlled waters. This requires the name of the ship, the type of the cargo as well as the voyage that is being carried out.

FRESH HOPE

On 22 July, 2022, the United Nations and Türkiye facilitated an

agreement for the Black Sea region, initially set for a duration of 120 days.

The purpose of this agreement was to address a worldwide food crisis that had been exacerbated by the armed conflicted between Ukraine and Russia, which led to an escalation in prices of grain products worldwide as Ukraine is a major exporter of grains globally.

Under this agreement, Ukraine is able to the transport grain from three Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea, namely Odessa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny.

For the carriage of the cargo a route – known as the “grain corridor” - was established which allowed vessels to proceed without being targeted by either country.

Under the agreement, a committee was established called the Joint Coordination Centre that comprises representatives of Ukraine, the Russian Federation, Türkiye and the United Nations.

With more than 3 million tonnes, Türkiye has been the third biggest destination for cargo loaded from Ukraine. It is also the provider of the joint inspections of the Joint Coordination Centre, which are carried out to confirm that vessels are in compliance with the agreement, and mostly carried out in Istanbul ports.

A significant increase has been seen in maritime traffic in the Marmara Sea as well as the Turkish straits. Because of the increasing number of vessels in Marmara Sea, the vessels found it difficult to

find a place in anchorage areas, especially in Istanbul where the joint inspections are carried out.

CROWDED ANCHORAGE AREAS

As a natural result of the crowded anchorage areas - both due to the “grain corridor” and the P&I letter requirement - a substantive increase has been seen in collision cases at anchor. While most of the incidents are relatively small, in addition to some big claims, further claims may be brought because of delays arising from the formalities of the collision.

Under Turkish Law the authorities are empowered to commence an administrative investigation in cases of collisions where a sea protest is required.

A sea protest is issued by the courts in Turkiye where statements of the master along with the relevant crew, would be taken in a hearing then the sea protest will be issued.

Moreover, the statements of the same crew members would be also taken by the harbour master.

The vessels are only allowed to sail after the completion of the statements and submission of the requested documents and with a letter issued by the classification society certifying that the vessel can sail.

Therefore, even small collisions are causing loss of time and in some cases, delays because vessels are not allowed to travel the grain corridor if there is any detention by the harbour master due to collision.

The Turkish government is taking measures to prevent or decrease the number of the incidents.

But, because of these new measures introduced to reduce the waiting time or assignation of new anchorage areas in other ports in the south of the Marmara Sea (Çanakkale owners), means that insurers and other shipping interests need to be aware that the risk of becoming involved in an incident has significantly increased since the establishment of the grain corridor.

“Insurers and other shipping interests need to be aware that the risk of becoming involved in an incident has significantly increased since the establishment of the grain corridor.’’

Ibrahim Onur Oguzgiray, Cavus & Coskunsu

Please forgive the disruption

Dr William Moore , Senior Vice President and Global Head of Loss Prevention Shipowners Claims Bureau, Inc., Managers

of the American Club looks at the the benefits of the International Safety Management (ISM) Code for shipowners

The International Safety Management (ISM) Code entered into force for shipowners and operators in July 1998 and brought both high expectation and apprehension as well.

At the time, there was a critical mass of shipowners and operators that had already adopted a more holistic safety management philosophy and culture approach that incorporated the objectives of the ISM Code.

On the other hand, most of the maritime industry at the

time were primarily focused on complying with mandatory statutory instruments that were significantly prescriptive in nature. These included, for example, classification society rules and IMO conventions (SOLAS, Load Lines, MARPOL, etc.). Implementation of the ISM Code has led to changes in the way our industry approaches safety.

Compliance with the requirements of the ISM Code, oversimply stated, boils down to three simple things: “Say

what you do, then do what you say and then prove you’re doing what you say.” Furthermore, the ISM Code takes account of constant consideration and review of risk exposure and importance of the process to regularly review and consider those risks with an objective of continuous improvement.

This is reflected through two interrelated components that are key to effective safety management: An assessment of identified risks (Section 1.2.2.2) and non-conformities, hazardous occurrences and accidents are to be analysed and reported (Chapter 9).

These are key precursors to ensure compliance with ensuring vessels are manned with sufficient resources and personnel (Chapter 6), safe shipboard operations (Chapter 7) and well prepared for any emergencies that arise (Chapter 8).

VESSEL RISK MANAGEMENT

How should one consider the risks for a vessel? What are they? How critical are each of the risks to safe operations? Should all risks be considered? How can the risks be reduced, eliminated or mitigated?

These questions depend on many contributing factors that include, but are not limited to, the vessel’s design, cargoes carried, trading pattern, qualifications, motivation, training and working conditions of the crew and the like.

The US Coast Guard in their commercial vessel compliance mission management work instruction, US Flag Interpretations on the ISM Code (CVC-WI-004(2) of 30 July 2020), have set forth 21 risks that should be considered at a minimum in establishing emergency preparedness as required under Chapter 8 of the ISM Code.

Despite this prescriptive list of risks, it does provide a list of well-known risks that many ocean-going vessels are exposed to. However, there are no requirements or guidelines on effective methods to assess those risks while considering the contributing factors.

Furthermore, there are several challenging factors that impact the reporting of non-conformities, hazardous occurrences and accidents that include but are not limited to:

(1)Inconsistencies in understanding what constitutes non-conformities and hazardous occurrences;

(2)A lack of training, experience and procedural support of seafarers to properly perform investigations of incidents;

(3)Striking a balance on the details of what to report and format it is to be reported; and,

(4)Having a strong company and shipboard “just” culture that regularly promotes honest reporting as human errors are understood to occur, but, whereby individuals are also held accountable for willful misconduct or negligence.

Moreover, the reporting non-conformities and hazardous occurrences is viewed by many as being disruptive to the work process whereby seafarers are already under pressure of commercial demands and the normal daily tasks associated with shipboard life.

DISRUPTIVE BURDEN

I recall reviewing a shipowner’s documentation for tanker chartering that stated that each vessel was required to make two “near miss” reports per month.

In that company, reporting was seen as a disruptive burden rather than an important component of enhancing safety and environmental protection.

At the American Club, we grappled with the constant challenges of developing effective means of disseminating guidance to our shipowners and operator members and tools for their seafarers.

The global seafarer community includes a broad range and diversity of nationalities, many of which are native English speakers, possess significant ranges of seafaring knowledge and experiences. They also differ widely in age whereby generational differences influence how they have been educated and trained in the use of technology.

In 2021, we launched a seafarer focus initiative named

“Compliance with the requirements of the ISM Code, oversimply stated, boils down to three simple things: “Say what you do, then do what you say and then prove you’re doing what you say.”Figure 1

Good Catch that is featured both on the American Club’s website and mobile application in both English and Mandarin languages.

The initiative combines alerts and animations on safetyrelated issues in a focused format aimed principally at seafarers themselves.

Good Catch recognizes that, although there may be differences in detail between individual safety management systems, they all have a common purpose in ensuring seafarers’ situational awareness and their personal responsibility for their own safety, that of their shipmates, the marine environment and the many other interests involved in their service at sea.

The importance of a strong safety culture that identifies, assesses and reports unsafe conditions, unsafe acts and near misses, cannot be overstated. As seen in Figure 1, we emphasize the importance of situational awareness.

In addition, Good Catch also features safety animations, many which feature case studies of incidents and measures to take to prevent such incidents as seen in Figure 2 (above left) that demonstrate a line handling incident.

We also emphasize the importance of situational awareness in the prevention of slips, trips and falls. In 2017, the American Club in cooperation with the American Bureau of Shipping and Lamar University ascertained that from 2013 to 2017, 34% of injury claims accounting for 32% of injury related claims costs were the direct result of slips, trips or falls. We’ve brought attention to these risks through the Good

Catch animated artwork media format as well as our regularly featured Alerts (see Figure 3 above and Figure 4 below).

Many of us hark back to the days of old when maritime life was simpler. Well-established prescriptive rules and standards applied and not the plethora of safety and environmental regulatory requirements we now find ourselves subjected to. We cannot bring those days back.

However, we can do our best to reduce the misconception that reporting of non-conformities, hazardous occurrences (including hazardous situations and near misses) and accidents are not disruptive but key to their own personal safety. With better reporting, we gain a better understanding of what personnel, operational requirements and emergency preparedness.

Sometimes, taking small steps thought to be disruptive are are the necessary steps to truly improve safety.

“In 2017, the American Club in cooperation with the American Bureau of Shipping and Lamar University ascertained that from 2013 to 2017, 34% of injury claims accounting for 32% of injury related claims costs were the direct result of slips, trips or falls.”Figure 3 Figure 2

70+ Countries. 5 Oceans. 1 Network.

As a leading global marine insurer we know the risks businesses face. Our global solutions and expertise help our clients to face them with confidence.

AIG’s marine team has decades of experience in underwriting, loss prevention and claims handling across the globe. We put our experience and expertise to work every day for our clients, assisting them to protect their assets, maintain business continuity and retain their customers’ loyalty. To let us help you to face your risks with confidence visit aig.com

How to tackle the stowaway challenge

The reasons for stowing away are many and complex. Some migrate because of the risk of human rights violations, others because they want to work, study, or join family members, or because of poverty or political unrest.

In a world of geopolitical disturbances, regional unrest and impact of climate change, people are likely to continue to migrate, by land and by sea, through whichever means available. Is a zero-policy strategy for stowaways possible in a world where migration is only expected to increase?

Stowaways are regularly found onboard ships and shipowners together with Gard and other stakeholders and service providers have gained extensive experience in resolving stowaway situations.

Why are stowaways a problem? While efforts are being made to disembark the stowaways, crew members will have to guard and take care of them. The extra workload impacts their day-to-day work, possibly also rest hours.

Worst case, the situation can become a security risk, for example if stowaways are disruptive or if lifeboat capacity is exceeded. Repatriations can be costly and delay the vessel.

The significant risk of injuries and loss of lives that the stowaways are exposed to while in hiding and during the voyage should also not be forgotten.

Unnoticed by the master, crews, port and customs authorities, stowaways can gain access to ships with or

Stowaways seem to be an ever-present problem for the shipping industry. Migrants continue to risk their lives by ‘stowing away’ on board ships. And the number is expected to increase. Lene-Camilla Nordlie ,Vice President, Head of People Claims, Christopher Elefsen , Claims Executive of Gard explainsPHOTO: SALVAMENTO MARATIMO

without the assistance of port personnel. This is illustrated by the famous Swiss Cheese model: How many ‘holes or barriers’ can the stowaway pass before being stopped? The answer depends on the quality of the risk management.

Different ship types and sizes need different security procedures and some trading areas may need additional measures. Although international regulations and guidance outline security measures, an assessment should be made for each voyage to ensure it is relevant, practical and realistic.

HIGH RISK PORTS

It may be difficult to accurately predict high-risk ports, yet there are certain geographical areas which historically have been, and still are, considered high risk. Among these are ports in southern and west Africa.

Security at ports can range from exceptional to virtually non-existent. The risks may be higher where the ISPS Code has not been properly implemented. Ships’ agents can provide advice in advance of a ship’s call. But shipowners and masters may have little or no influence on port security and instead must focus on preventing stowaways from gaining access to the ship.

Therefore, it is vital to communicate to the agents that the ship will not sail with stowaways onboard and that all necessary safety measures available at the port should be implemented.

Various measures relating to ship security and watchkeeping can be implemented depending on the potential risk of stowaways in a particular port.

First and foremost, proper access control relies on crew members being properly briefed about the ship’s trading patterns and stowaway risk and the relevant security measures to be implemented.

To best guard against unauthorised boardings, all crew members, especially those with specific security duties and responsibilities, must understand the threats facing them in a particular port. Onboard instructions must clearly specify when to control access to the ship and how to do it.

The strategy is to ensure that no unauthorized personnel are able to gain access to the ship and that all those who have been authorised to board disembark before sailing.

STOWAWAY ALARM

If stowaways have gained access, they must be dealt with consistently with humanitarian principles. Due consideration must always be given to the operational safety of the ship and to the safety and well-being of the stowaways.

Any stowaways found should be placed in secure quarters, guarded if possible and be provided with adequate food and water. They, as well as the place they were found, should be searched for any identification papers.

Where there is more than one stowaway, they should preferably be detained separately. The master and crew should act firmly, but humanely and if needed, the stowaways should be provided with medical assistance. Stowaways should never

be put to work.

It is important to collect as much information as possible on how stowaways have boarded the ship, as well as the ship’s efforts to prevent stowaways boarding and to locate any stowaways prior to leaving port. This includes details of access restrictions, watch arrangements, locked areas and the like.

It is key that all involved parties collaborate to resolve stowaway cases, meaning an early repatriation of stowaways.

The ship must investigate and share relevant information with immigration authorities and countries must allow the return of stowaways with citizenship status or residential rights.

Where the nationality, citizenship or right of residency cannot be established, the country of the original port of embarkation of a stowaway should accept their return, pending final case disposition. P&I insurers and correspondents support and facilitate the process along the way.

BEATING THE ODDS

There is no doubt that the stowaway challenge will remain and most likely grow. It will be tough to beat the odds of avoiding stowaways on board in regions where people are driven to migrate.

A goal of zero-policy for stowaways will not resolve the problem, but setting and committing to a clear goal enhances focus and awareness of the people involved and can help identify and understand the challenges that need to be tackled to enhance chances of success in the next ports of call.

The stowaway problem is complex and involves a long list of stakeholders that individually and collectively need to work together to beat the odds.

Gard has recently published an updated comprehensive guide on stowaways outlining the problem, the applicable regulations, assessing the risk of stowaways, prevention at port and humane handling of stowaways found on board. While we hope for successful prevention, our P&I claims handlers are there to assist shipowners to resolve the situation, no matter how much time it may take.

“It may be difficult to accurately predict high-risk ports, yet there are certain geographical areas which historically have been, and still are, considered high risk. Among these are ports in southern and west Africa.”

The witnessesunwitting

It is standard for the Coast Guard to insist that the captain and the entire engine room department be disembarked from their shipboard home, turnover their passports/travel documents, and remain in a hotel within the federal district where the matter is pending for an unknown and unlimited amount of time during the government’s investigation.

The seafarers are not parties or signatories to the agreement on security. When a seafarer asks to go home or to have their passport returned to them, the government denies those requests.

Worldwide, there are signs and placards throughout airports, train stations, seaports, and bus stops offering assistance to individuals who may be experiencing being held against their will.

They often pose a series of questions along the lines of the following: “Is someone . . . holding your passport or personal documents; threatening you or your family; controlling your movements; and/or forbidding you to go anywhere or speak with anyone you want.”

These are tale-tell warning signs of human trafficking, involuntary servitude and modern-day slavery. The posted signs are jarring, but they are not just for individuals to reach out for help. They are also designed to raise awareness for the public to be on the lookout for distressed individuals in need.

There is no dispute that the persons being held against their will is a bad thing and has no place in the modern world.

However, in the US there is a government sanctioned regime whereby foreign seafarers are routinely held against their will as involuntary detainees and material witnesses in MARPOL/APPS prosecutions.

Pursuant to 33 U.S.C. §1908(e), the Coast Guard (and customs and border protection acting at the Coast Guard’s instruction) can revoke and refuse to reinstate a foreign flagged vessel’s departure clearance until surety satisfactory to the Secretary is posted.

Such “surety” takes the form of an “agreement on security,” which requires not only the posting of a financial undertaking by the vessel’s owners and operators, but also requires the removal of seafarers from the vessel.

When a seafarer applies to the court to have their travel documents returned or to have their deposition taken so they may leave the US, the government opposes the requests.

Typically, the government will implement some combination of the following procedure to block a seafarer’s right to departure:

1)claim that the crewmember is in the US voluntarily;

2)argue that there is no right to a deposition because criminal charges are not yet pending; and

3)if all else fails, obtain a material witness arrest warrant pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3144 to ensure that a seafarer remains for trial.

MATERIAL WITNESS

The purpose of the material witness statute is to secure the presence of a witness who possesses information material to a criminal proceeding.

Some district courts have found that seafarers held pursuant to an agreement on security and/or material witness warrants in MARPOL/APPS cases were functionally detained as a result of this arrangement, even if not formally incarcerated, and therefore entitled to have their deposition taken so that they could return to their jobs and families abroad. See, eg In re Zak, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 222937, *17 (D. Me. 2017); United States v. Dalnave Navigation, Criminal No. 09-130, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21765, 2009 WL 743100, at *2 (D.N.J. Mar. 18, 2009); Mercator Lines Ltd. (Sing.) PTE Ltd. v.M/V GAURAV PREM, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 153429, *28-31 (SDAL 2011). However, even in those matters, the seafarers had to complain of detention for many months before the court took action.

In two recent cases, US Magistrate Judges in the Eastern District of Louisiana and Southern District of California have

George Chalos , partner at Chalos & Co, describes how seafarers detained as witnesses under MARPOL/APPS prosecutions are routinely used as pawns

refused to order depositions, instead finding that the government’s interests in completing charging decisions and live testimony of witnesses was of greater interest than the rights and liberty of the individual seafarers. See, eg, In re Joanna, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 114281, (ED La. 2021)(finding that the prosecutors’ subjective intent of the use of the material witness warrant was not reviewable, so long as the warrant was facially valid) (citations omitted); In re Rana, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 227288 (SDCA Dec. 16, 2022) (finding exceptional circumstances did not exist to order depositions, despite crew being detained for seven months)). In another recent case, United States v.Evridiki Navigation, et al., in the District of Delaware, the court finally ordered Rule 15 depositions after the crew members were detained for several months by government officials on the basis that their testimony would be significant to the investigation and prosecution. When the crew members returned for trial six months later, the not call any of the seafarers as witnesses in the case.

WARRANT STATUTE

The actions by the government are all the more egregious compared to how the material witness warrant statute is routinely used in other criminal matters in the US.

For example, in U.S. v. Whited, the court found that Christopher Cambron had material information relevant to a pending criminal matter in which the defendant was accused of armed robbery of at least seven businesses.

Due to Mr Cambron’s history of drug and alcohol abuse, the government sought a material witness warrant to keep him in custody to ensure his availability for trial. United States v. Whited, 3:21-cr-29, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 230521 (E.D. Tenn. 2022). The Court agreed and ordered Mr Cambron detained.

However, the District Court directed his deposition to be completed within a week and Mr Cambron’s deposition was completed the day after Christmas on December 26, 2022. He was released the next day after spending less than seven days in custody.

Similarly, in US border cases, material witnesses are often detained, deposed, and then released within a matter of days. See, eg, W.D. Tex. Local Criminal Rule 15b (setting out the procedure for deposition and release of material witnesses and requiring

release within 24-hours of deposition or 45 days of first appearance in court, whichever occurs sooner).

So why are seafarers, who are historically recognized as ‘wards of the court’ to be afforded special treatment and protection, abused by the system in MARPOL/APPS cases?

The reason is simple: the crewmembers are pawns used by the government as an additional pressure point on the owner and operator in these prosecutions.

The expense of paying for the total wage salary, per diems, hotel costs and local travel expenses for the crewmembers detained in the district can reach $30,000$50,000 per month (or more).

Meanwhile, seafarers who most times have done nothing wrong, are forced miss important life events: births, deaths, anniversaries, family obligations and the like.

This is a result that is all the more inhumane and disproportionate when considering that the US courts routinely use remote appearances and/or video recorded deposition testimony in lieu of live, in-person testimony.

“Pursuant to 33 U.S.C. §1908(e), the Coast Guard (and customs and border protection acting at the Coast Guard’s instruction) can revoke and refuse to reinstate a foreign flagged vessel’s departure clearance until surety satisfactory to the Secretary is posted.”PHOTO: US COAST GUARD

A technical aspect of sampling of hydro carbon products

By Captain Stewart

By Captain Stewart

In the maritime industry, tanker vessels are chartered to carry various products and as part of this remit, the shippers are required to conduct sampling. This is done to ensure that the cargo being loaded is of a suitable quality and meets a particular specification or contractual requirement. In this article, we provide brief explanations for some of the technical aspects of the sampling of hydrocarbon products (such as petroleum, fuel oil) in tanks, the different types of samples to obtain a representative composite sample of a tank for analysis and the trend of including the bottom sample.

Energy Institute (EI) and American Petroleum Institute (API) committees, under the cover of various publications, consider sampling methodology as evidence of best industry practices in manual sampling of hydrocarbon products in both ship and shore tanks. Guidance on sampling can be found in the following:

> API MPMS Chapter 8.1 Standard practice for manual sampling of petroleum and petroleum products 6th Edition 2022;

> ASTM D4057 – 22 Standard practice for manual sampling of petroleum and petroleum products.

> HM93 1st Edition Guide to manual sampling of hydrocarbon products.

As set out in API MPMS Chapter 8.1, the intention behind the sampling is to obtain a small sample that is representative, either of a particular point in the tank, or of the cargo in the tank as a whole.

8.Manual sampling concepts and objective

8.1 Objective of manual sampling -The objective of manual sampling varies. In some instances, the intention is to obtain a small portion of product that is representative of the tank or container contents. In other instances, samples are specifically intended to represent product only at that one particular point in the tank, such as a top, dead bottom, or suction level sample. When a tank is determined to be homogenous, a series of spot samples may be combined to create a composite sample.

API MPMS Chapter 8.1 also defines a representative sample as:

§3.3.19 representative sample - a portion extracted from the total volume that contains the constituents in the same proportions that are present in that total volume.

To put this into context a single litre sample may be required to be representative of a tank that holds many thousands of litres of product.

The definitions of the various level samples in API MPMS Chapter 8.1 are as set out below:

§3.3.8 dead bottom sample - a sample obtained from the lowest accessible point in a tank. This is typically directly from

Horan , Master Mariner, LLM, at Hawkins & Associates, a global company specialising in forensic root cause analysis, expert witness services and engineering consultancy to the insurance, legal, risk management and commercial sectorsVessel Sampling Device and 500ml Spot Sample Taken from Cargo Tank

the floor (or datum plate) of the shore tank or the bottom of the vessel compartment.

§3.3.3 bottom sample - a spot sample collected from the material at the bottom of the tank, container, or line at its lowest point. In practice, the term bottom sample has a variety of meanings. As a result, it is recommended that the exact sampling location (for example 15 cm (6 in.) from the bottom) should be specified when using this term.

§3.3.16 lower sample- a spot sample of liquid from the middle of the lower one-third of the tank’s content (a distance of fivesixths of the depth liquid below the liquid’s surface).

§3.3.17 middle sample - a spot sample taken from the middle of a tank’s contents (a distance of one half of the depth of liquid below the liquid’s surface).

§3.3309 upper sample - a spot sample taken from the middle of the upper one third of the tank’s contents (a distance of one-sixth of the depth of the liquid below the liquid’s surface).

§3.3.28 top sample - a spot sample obtained 15 cm (6 in.) below the top surface of the liquid.

§3.3.24 surface sample (skim sample) - a spot sample skimmed from the surface of a liquid in a tank.

§3.3.20 running sample - a sample obtained by lowering an open sampling device to the bottom of the outlet suction level, but always above free water, and returning it to the top of the product at a uniform rate such that the sampling device is between 70 and 85 % full when withdrawn from the product.

API MPMS Chapter 8.1 further states inter alia:

§3.3.6 composite sample - a sample prepared by combining a number of samples and treated as a single sample.

§3.3.25 tank composite sample - a blend created from a single tank, as an example combining the upper, middle, and lower samples. For tank of uniform cross section, the blend consists of equal parts of the three samples. A combination of other samples may also be used, such as running, all-levels or additional spot samples.

Some samples, such as skim, top, bottom and dead bottom samples are representative of specific levels within a tank and so are not representative of the tank’s contents as a whole. They are only representative of the material at the position/level from which they are taken. Such “spot” sample types are shown in Figure 1. For marine shipments upper, middle and lower (U/M/L) samples in equal parts from each tank are generally

adequate for creating a representative volumetric composite sample of the individual tank.

However, as set out in the API Standards, if the initial U/M/L samples show the cargo in the tank is nonhomogeneous, it is recommended that additional spot samples at equidistant multiple levels should be taken. Furthermore, as set out in HM93 §3.3, U/M/L samples “… should not be confused with top and bottom samples. Top and bottom samples cannot be relied on to be representative of the bulk quality” and should not be used in the creation of a representative sample. They are used to determine the stratification and analysed in isolation with

“Energy Institute (EI) and American Petroleum Institute (API) committees, under the cover of various publications, consider sampling methodology as evidence of best industry practices in manual sampling of hydrocarbon products in both ship and shore tanks.’’Figure 1 - HM 93 – Schematic of Spot Samples in an Oil Tank

any technical interpretation thereafter.

API MPMS Chapter 8.1 raises the issue regarding water contents and non-homogeneity:

§9.2.8.1 Water in petroleum - The concentration of dispersed water in the oil is generally higher near the bottom of a tank or pipeline. A running or all-level sample, or a composite sample of the upper, middle, and lower samples, may not be representative of the concentration of the dispersed water present. The interface between oil and free water may be difficult to locate.

§9.2.9 Depending on the extent of stratification, it can be very difficult to obtain a representative manual sample. Spot samples, such as upper, middle and lower (UML), or top, middle and bottom (TMB) are recommended to establish the extent of stratification. Running or all-levels samples will contain all product layers in the vertical column from the sample point, although the rate of fill will be variable based on the depth of the product. Even with care, it may not be possible to exactly reproduce a manual sample from a nonhomogeneous or stratified tank.

§9.2.9 Spot samples may be taken to assess the level of stratification of a particular property within a shore tank or marine vessel compartment.

Sampling to create a representative sample of the bulk of the oil requires care and diligence. For example, a bottom (B) (15 cm from the bottom) or dead (absolute) bottom (DB) samples are taken where, if water is present, there is likely to be a predominantly higher water content than compared to the bulk of the cargo above. If a bottom or DB sample is included in the composite with the upper (U) (1/6th level from the surface), middle (M) (3/6th from the surface or from the tank bottom) and the lower (L) (1/6th from the tank bottom), then there is a disproportionate volume of lower sample volumes (50%) in the composite sample to be analysed (Table 1). Such a ‘composite’ may not be representative of the bulk cargo as a whole.

Inclusion of the bottom sample 15 cm from the tank bottom has a disproportionate and potentially dramatic impact such as with ISO 8217 marine heavy fuel oil having a maximum water content specification of 0.5 vol%.

This can be shown by the calculation in Table 1. Consider a tank with a cross sectional area of 100 sqm and liquid heel of 10 metres, which contains a nominal 1,000 cbm. If a bottom sample with a water content of 2 vol% is included, it contributes a disproportionate amount to the overall water content of a U/M/L/B volumetric composite sample. If the upper, middle and lower samples have a homogenous water content of 0.3% then the derived water content of the apparent representative sample is 0.73 vol% and does not meet the 0.5 vol% water content specified by ISO 8127 for marine heavy fuel oil.