C a n a d a

by sofia durdag

On the sixth day, just after moonrise, they were finally allowed to stop walking. The girls made a fire, and after that was done, they sat down to eat dinner. Paul was not much of a cook. In the beginning, before the police had found the car, they had surfed through a million Denny’s and Arby’s and McDonald’s. Before he stole their phones and charging cords and earbuds and buried it all deep under the earth on the third night, they had called up Domino’s and ate so many garlic knots that they threw up, one after the other. Poor Lovely had broken out terribly from the grease. Now that the car and the phones were gone, they survived on sour gummy worms, Cheetos, and loaves of Wonder Bread mushed into the bottom of Perfect’s backpack.

It was hard to remember now, but it had been good for those first few days. Like a new drug.

Paul surveyed the girls from across the fire, great orangey shadows thrashing over his narrow, bearded face, the fire making deep black pits out of his eyes. He was a demon, their mother had said, almost admiringly, after she found Perfect’s stashes of liquor and was in the mood for a drink. Perfect barely remembered him before he had left, but she was certain he had not been so bent and twisted, a smudgy, crumpled-up drawing of a man. But, even she had to admit, seventeen years and a recently concluded stint in county would probably do that to anyone.

Perfect never agreed with her mother—it was like an allergy—but something animal and soft in her bleated, demon demon demon as she looked at her father.

“I want to get out of the woods,” Perfect said. His mouth drew into a deep frown. And just like that, he lit a Camel Blue, glowering. He chased every emotion with a Camel. Now—Perfect nearly smiled at the thought—there were only three left in the pack. She had been counting them for the past couple of days. Those stupid fucking cigarettes were her and Lovely’s ticket out.

But Christ, Perfect was so sick of sour gummy worms that the smoke nearly tasted good. She mopped sweat from her brow, feeling it leak over her scalp and down her ribs, even though the night was cold and she wore only the fuzzy fleece she had left with. She was sweating bullets from not smoking weed for almost a week. She never had to buy her own supply, never even had to keep any in the house. It was a particular kind of magic, to extract what she wanted out of anybody. However, once they started to know her, the magic faded. Perfect used up boyfriends the way farmers sucked the soil dry after a few seasons. And perhaps that was why her mother had once leaned in very close, after Perfect had returned home after two full days, still gnashing her jaw from something that looked like coke, and said, There’s something rotten in you. I can smell it.

“I think we’re close to the border,” Lovely said, those wide, permanently glossy eyes flicking nervously between Paul and Perfect. “Maybe only a day or two. Canada will be—”

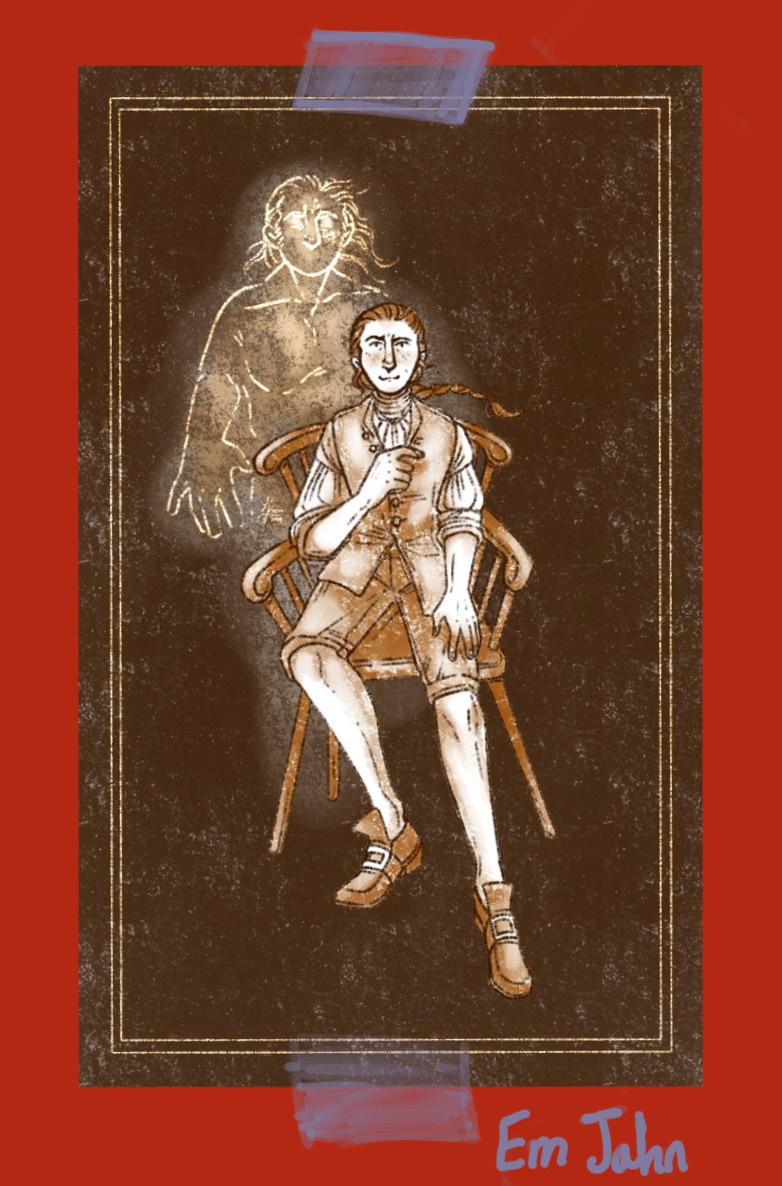

Canada was Lovely’s fresh obsession, her new thing to love to death. If they could just get across the border, there would be no more police, no more kidnapping charges. Her sweet Lovely, always with her head in the clouds. When their father had come to collect them, just after four in the morning on a Sunday, Lovely had already been wide awake.

I knew a good thing was gonna happen, Lovely whispered as she woke Perfect up that night. Like, so so good. Her sister chased anything that might love her better, and Perfect chased Lovely. And so, without much hesitation, they had left with him.

Their father leveled those flat black eyes at Perfect as he tore up a slice of pillowy white Wonder Bread, his dirty hands leaving black thumbprints. “We aren’t leaving,” he snapped, stabbing a finger in Perfect’s direction. “Don’t ask about that shit again.”

Of course, he was the one going back to county if they were found. He was the one with the crisp bundles of hundreds in the inside pockets of his coat that Lovely and Perfect were not supposed to ask about, the money that would be safe in Canada. Perfect had learned this the hard way. It was the only way she knew how.

She knew it was her fault for leaving. Yes, she had been bottomed out and washed up from a heavy haze of Smirnoff, hash, and ket, probably still high. But it was no excuse. Perfect was a shark. Bloodthirsty. Tactical. Always trading something bad for something better. But the whole week, her father’s presence—it had felt like the puffy blisters spreading like a plague over her heel. One wrong movement and everything would rent apart in a bloody rupture.

“They must know we’re in here,” Perfect said, violently chomping through the sticky body of a gummy worm. “They found the truck easy enough. They almost got us.”

At this, the fire popped and snapped like wrenched joints, sending sparks high up into the air to illuminate the tall, skinny pines. Lovely grabbed Perfect’s wrist tightly. Her sister was skinny and bug-like, but she had weirdly strong fingers. When they fought as children, Lovely would wrap her arms around Perfect and hold her fast until she surrendered. “Stop,” she said. “Listen to Daddy.”

She insisted on calling Paul Daddy. Lovely and Perfect were nearly the same age, only ten months apart. Neither of them even recognized his face when he knocked on their door—really knocked, like a traveling salesman—asked if they wanted to get out. But Lovely got attached to everything, sobbing over lost dolls, clinging to disinterested friends like a life raft. It was a point of pride for Perfect that Lovely would never have to cry over her. They were like two saplings that had grown together. They would never know how to live without each other.

There was a terrible, grating pause, her father daring her to obey. Beads of sweat coursed down the side of Perfect’s face. “Fine,” she said, carefully. It was hard to lie when she was sober, but she managed.

Lovely beamed, gumline caked with sickening orange Cheeto dust, and gathered Perfect up close to her, mashing her face into the space between Perfect’s neck and shoulder. Her sister’s fingers dug into the back of her neck, her warm breath echoing in her ear. Lovely did not embrace so much as attempt to shear apart her atoms and sink wholesale into Perfect’s body.

Paul seemed disturbed by all this. Men always were. “Behave, girls,” her father threatened, rising to stand over the fire, his face shining an electric yellow.

“Fuck off,” Perfect hissed at him. Lovely sank her nails into the nape of Perfect’s neck like a rabid raccoon, grabbing on harder. Be sweet, she was telling her. Lovely believed she could charm the world into treating her right. In the little house by the airfield, Lovely made their mother dinner and brushed her hair and did the taxes. But she had still ended up here.

Now their father was wildly shaking his head, as if he was trying to blur Perfect out of existence. “I made you. I named you,” he said. He had done a piss-poor job of it. What kind of psychopath named their second daughter Perfect? “So you’ll fucking listen,” he said.

“You know what’s best, Daddy,” Lovely said sweetly, tangling her fingers in Perfect’s long hair so that she wouldn’t pull away with annoyance. “Can we just go to sleep?”

Paul didn’t like it when they slept. That’s when the devil gets in, he had said on the third day. They had stayed up for seventy-two hours straight before Lovely had begged him to let them sleep in the back of the car, just for a few hours. It had been an easy task for Perfect, who was still jumpy from the last of her pills, but Lovely had no such gifts.

“You know what’s best,” she repeated dully into Lovely’s pimpled cheekbone, and they were finally, finally allowed to go to sleep.

On the seventh day, they continued walking north, ever north, following the curve of the rural highway that carved through miles and miles of useless green nothingness. Paul had two cigarettes left in his pack. He was still fuming over what had happened last night. Their father was a different animal than Mama. She was careful and sharp, a knife making a precise quarter-turn into your guts.

Two cigarettes more, and Paul would have to stop at the nearest gas station to buy another pack. Then, and only then, she would throw Lovely over her shoulder kicking and screaming, and they would run, just the two of them. The sisters trailed Paul as he marched ahead, thick plumes of smoke hanging over them like a miasma. She stared at the back of her father’s head as Lovely hummed the tune of a cereal commercial. Imagined swinging a branch right into the middle of his bald spot.

All of the extra—the weed, the pills, the powders, the drink—had finally drained from her, like a lanced boil. It made her feel like Lovely, raw and shiny.

“You look pretty today,” Lovely murmured to her. “Except you should have brought a brush.” Perfect scowled. “I thought you were gonna bring one,” she said, hooking her arm through Lovely’s so that they walked hip to hip. Lovely always thought she was prettier with nothing in her bloodstream.

Lovely let out a delicate, jangling laugh, trying to pull apart her hair, which had matted into a thick rug at the crown of her head. Paul whipped his head around to stare at them. “I knew it,” she said to Paul, those saucer eyes wet with emotion. “This was how it was always supposed to be.”

“Just right, Lovely,” he said, a satisfied grin on his demon face.

“What are you smiling for?” Perfect snapped.

His scrunched mouth slackened. She saw the naked beginnings of fear on his face, before it hardened. “I got half a mind to leave you right here,” he said, waving his hand around the vast virgin forest, the distant whoosh of cars on the highway. “See how you like it.”

That should finish off the last two cigarettes.

“I just wanna make it to Canada, Daddy,” Perfect said softly, and Lovely trilled with glee, her relief so palpable that Perfect felt it seep into her very bones.

On the eighth day, at the unhealed, ugly break of dawn, they reached a gas station on the outskirts of a little no-name town. They had not slept, walking on the vacant highway’s dim shoulder through the night. Sleeplessness had made her strangely wired and jittery, like her body still thought she had spent the whole night in some friend of a friend’s basement. It was so early in the morning that there were no cars getting gas. She craned her neck, but even the employee that must be inside had been dropped off, with no car parked in the back. The trees crowded around the small, lumpy square of pavement that the station sat on. She heard no cars on the highway. The world seemed to crush small and tight around her chest. No way out.

“Don’t make that face,” Lovely whispered as they stood shivering together outside the gas station as their father peeled off dollar bills from one of his forbidden coat stacks.

“What face?”

Lovely contorted her face a monstrous, pained frown. “This is a good thing,” her sister said, so quietly the wind almost caught her words and carried them away. Her face was pleading. “It is.”

She brushed her fingers against Lovely’s windburnt cheek. “You would have been a good nun.”

“Girls!” Paul interrupted, his voice burnt out and raspy from the Camels. “Inside.”

They dutifully followed him. She gave one last, mournful look to the parking lot. Her last boyfriend had taught her how to hotwire a car. It wouldn’t help her now.

She scrubbed her fingers over face, fingers coming away slicked in a muddy grease before she scanned for anything heavy, solid. She had never even thrown a punch, except the one time she had accidentally taken bath salts. But if she didn’t remember it, did it even count?

The Cumby’s was a blinding paradise after days of crowded green forest and dim light filtered through the thick canopy of pines. There was a single clerk in the store, surely on the last hour of his overnight shift. He looked at them blearily, his phone—God, Perfect had forgotten that she had once owned one—blaring some yappy male podcast.

Perfect moved to the back, Lovely lingering by the Hostess snacks, though she knew that Pual would never let them buy any. She moved towards the liquor aisle as Paul went up to the counter, making a big show of buying lottery tickets.

Quietly, carefully, she picked a large bottle of Moscato. Four bucks. She liked the idea that it would only take four dollars to dispatch Paul from her existence. Lovely was still eagerly perusing the sweet treats. The dentist always sighed heavily when her sister came in.

Taking the bottle of Moscato, she crept slowly behind her father. She was used to walking carefully, quietly, in the little house by the airfield. Mama woke at the smallest noise. The clerk locked eyes with her, scanning her body up and down, the weird mix of pajamas and outerwear, the hideous mat of greasy hair.

She only needed one good swing, like a softball bat. But Lovely let out a squeaky scream behind her, dropping her armful of Twinkies and Muddy Buddies. She bounded towards Perfect— during her freshman year she had been a track All-Star before she had quit at their mother’s behest—and grabbed Perfect’s arm with that strange alien grip. The bottle arced away from Paul’s head, landing between his neck and shoulder. There was a wet crash, sticky white wine spraying over her face and her shirt. Lovely tackled Perfect around the middle, crashing onto the slippery, just-mopped gas station tile. Paul collapsed over the counter, his chin hitting the card machine. He didn’t make a noise, only a soft exhalation of breath like he was falling asleep.

“Are you fucking high?” Lovely roared, arm locked around Perfect’s shoulders. The clerk was wailing, flailing for the phone, as the podcast thundered on.

“Why won’t you let it be good?” Lovely sobbed. “Why won’t you let it be good?”

They had crashed into the wire rack with all of the cheap tech products that imploded with one use. It toppled over them, and Lovely’s grip slacked for a single second. Perfect wrenched her body over Lovely’s, pinning her to the ground.

“I made you,” Perfect seethed, lightning throbbing in her blood. “Nobody else. I made you.”

Now her father had risen up, an awful, bleeding revenant, stumbling towards the knot of Perfect and Lovely on the ground. Perfect dragged Lovely up, feet slipping in soap scum. Lovely had stopped resisting—this was the essential thing to know about Lovely, was that there was always a softening point, a giving up. Her lovely Lovely, who could never hold on quite long enough. Perfect found that she was still holding the broken shards of the four-dollar Moscato. She brandished it at Paul.

“Get away,” she said, feeling like she had flown free of her body, finally, finally loosed it.

She pushed Lovely through the swinging glass doors, out into the misty parking lot, distant sirens already screaming their names over and over and over.

“We wanted to be made out of something good,” Lovely cried as Perfect lugged her forward and forward, Paul still tripping behind them, clutching the back of his head and speaking in a new language, like the demon that her mother had always warned of had taken over his bones.

“You made me,” Perfect said, gripping Lovely’s chin, their faces so close that Lovely’s eyes slid into one large Cyclops orb. “You did.”

And her sister, her very own blood, nodded.