CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL VOLUME 47 2022 PLANNING FOR HEALTHY CITIES

CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

Carolina Planning Journal is the annual, student-run journal of the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE

© Copyright 2022 Carolina Planning Journal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 4.0 International License

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

W. Pierce Holloway

MANAGING EDITOR

Emma Vinella-Brusher

EDITORIAL STAFF

Rachel Auerbach

PRINTING

A Better Image Durham, North Carolina

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this publication was generously provided by the Nancy Grden Graduate Student Excellence Fund, which supports graduate students working directly with the department’s Carolina Planning Journal, the John A. Parker Endowment Fund, the North Carolina Chapter of the American Planning Association, the Graduate and Professional Student Federation of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and our subscribers.

Carolina Planning Journal

Department of City and Regional Planning University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill CB #3140, New East Building Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3140 USA

Ruby Brinkerhoff

Lance Gloss

Walker Harrison

Rene Marker-Katz

Cameron McBroom-Fitterer

Amy Patronella

CONTRIBUTORS

Jordan April

James Hamilton

Sarah Kear

Jo Kwon

Sophia Nelson

Isabella Niemeyer

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Emily Hinkle

COVER PHOTOGRAPHER

Josephine Justin

SPECIAL THANKS

The Carolina Planning Journal would also like to thank the many people who have helped us this year, including Ben Howell and Bonnie Estes from the North Carolina Chapter of the American Planning Association, our faculty advisor Andrew Whittemore, DCRP accountant Kathy Uber, Mike Celeste at A Better Image Printing, former Carolina Planning Journal editor-in-chief Will Curran-Groome, Jordan Pleasant, our representative on the committee of the Graduate and Professional Student Federations, Planners’ Forum co-presidents Jen Farris and Cameron McBroom-Fitterer, and, of course, all of our subscribers.

carolinaplanningjournal@gmail.com carolinaangles.com

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill DEPARTMENT OF CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL PLANNING FOR HEALTHY CITIES VOLUME 47 / 2022

CONTENTS

4 FROM THE EDITOR

FEATURE ARTICLES

10 Lead Exposure, the Built Environment, and Social Vulnerability in North Carolina

Elijah Gullett

18 How Planners Address Extreme Heat with Equitable Resilience

Emily Gvino, MCRP, MPH / Julia Maron, MCRP

28 Expanding Crash Data Analysis

Daniel Capparella / Jessica Hill, AICP, PMP / Ashleigh Glasscock

36 Catching Health Messaging! The Translational Role Cultural Institutions Play in Cities

Rebecca F. Kemper, Ph.D. / Frederic Bertley, Ph.D. / Joseph Wisne

46 The Best Road Safety Plan is a Good Land Use Plan: Current and Promising Roles for Land Use Planning in Realizing a Vision Zero Future

Seth LaJeunesse / Becky Naumann / Elyse Keefe / Kelly R. Evenson

57 Quantity To Quality: Pursuing Community Wellbeing Through Economic Development

Eve Lettau / Marielle Saunders

66 At the Crossroads: The Intersection of Transportation and Public Health

Michelle Nance / Emily Scott-Cruz

2 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

6 STAFF 10

BOOK REVIEWS

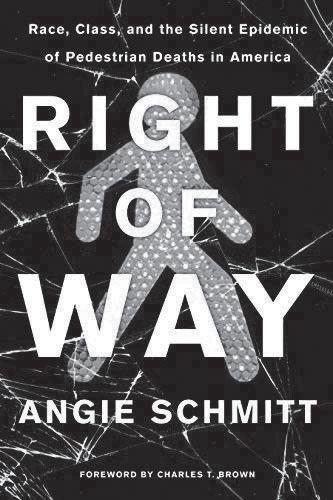

78 Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America by Angie Schmitt

81 Uneven Innovation: The Work of Smart Cities by Jennifer Clark

85

The City Creative: The Rise of Urban Placemaking in Contemporary America by Michael H. Carriere / David Schalliol

88 Last Subway: The Long Wait for the Next Train in New York City by Philip Mark Plotch

91 Sunbelt Blues: The Failure of American Housing by Andrew Ross

94

The Affordable City: Strategies for Putting Housing Within Reach (and Keeping it There) by Shane Phillips

97 Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-made World by Leslie Kern

3Planning for Healthy Cities 78

99 YEAR IN REVIEW 101 MASTER’S PROJECTS 104 PHOTO CONTEST 105 VOLUME 48 CALL FOR PAPERS

FROM THE EDITOR

PIERCE HOLLOWAY is a second-year master’s student at the Department of City and Regional Planning with a focus on climate change adaptation and data analytics. Before coming to Chapel Hill, he worked as a geospatial analyst for Urban3, working on visualizing economic productivity of communities and states. Through his coursework he hopes to explore the nexus between adaptation for climate change and community equitability. In his free time, he enjoys long bike rides, trail running, and any excuse to play outside.

Winston Churchhill was once quoted as saying, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” We as planners have a responsibility to look to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the resulting challenges, as an opportunity to learn and better frame how our work can bolster health. Volume 47 of the Carolina Planning Journal is titled “Planning for Healthy Cities.” The title itself is aspiration, as the concept that planners alone can ensure healthy communities is fantasy. Planners must collaborate with, listen to, and learn from multitudes of individuals from varying fields. Health is not tied to just the physical space of the city; it spreads beyond tangible infrastructure and extends deep into the roots of a community.

By 2050 it is projected that 70% of the world’s population will be living in urban areas. The weight of this and other projections have prompted many influential organizations such as the European Union, World Health Organization, and American Planning Association to examine the pivotal role planners play in improving and protecting the public’s health for generations to come.

To explore the many definitions and concepts of a planner’s role in promoting health,

we asked students, professionals, and researchers alike to explore the nexus of planning and health. The resulting articles provide an array of interpretations and important perspectives on how planning is intertwined with health.

Decades of research have shown a connection between adverse outcomes from childhood lead exposure and its ties to racial and class inequalities. Elijah Gullett (UNC ’22) contributes to this body of work by examining a case study of 31 counties in North Carolina. Importantly, the topic of healthy cities extends beyond symptoms identified by a medical practitioner and includes how social anchors can influence a community’s economic health. Marielle Saunders (MCRP ’22) and Eve Lettau (MCRP ’22) examine the link between health outcomes and economic development strategies. Their article leverages three case studies to explore strategies that shift the economic development paradigm from pure growth to quality development and community wellbeing.

During COVID-19 there was a constant struggle to effectively and clearly communicate evolving scientific information. Rebecca Kemper, PhD, Frederic Bertley, PhD,

4 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

and Joseph Wisne consider the struggles cities have had converting successive, highly technical medical research findings into protective health advisories. Their work seeks to provide planners with an understanding of how to use cultural institutions as a public health resource and communicative resource.

Developing tools and frameworks that can assist planners to best address varying issues is an important field of research. Emily Gvino (MCRP ’21) and Julia Maron (MCRP ’22) look at how local planners and municipalities, primarily in urban communities, can best address extreme heat within the lens of equitable resilience. The reframing of how planners can address climate resilience provides many parallels to how planners may address other community issues. Michelle Nance and Emily Scott-Cruz identify ways public health intersects with transportation planning and provide recommendations to North Carolina transportation planners, policymakers, and advocates. Their article offers advice for how to improve health outcomes through changing transportation planning practices, policy making, and prioritization.

Building on the importance of developing safe transportation system policies, Daniel Capparella, Ashleigh Glasscock, and Jessica Hill (DCRP ’09) use Nashville, TN, to develop a non-motorized risk index. Their system-level tool can be used to proactively identify areas with unsafe non-motorized conditions and motivate other transportation planners to reimagine how they classify risk.

Vision Zero, a global movement to end trafficrelated fatalities, takes a systemic approach to road safety. While Vision Zero plans have grown in popularity across the country, they are implemented to varying degrees. Seth

LaJeunesse, Becky Naumann, Elyse Keefe, and Kelly R. Evenson examined 31 United States Vision Zero plans published through mid-2019 to explore the degree to which local and regional transportation safety plans intended to eliminate serious and fatal road injury (Vision Zero) integrated land use plans, planners, and ordinances.

This year’s cover photo comes from Josephine Justin (DCRP Master’s student). She explores the relationship physical spaces have with health, offering New York City as an example.

“Two years ago, New York confirmed its first COVID-19 case and the City shut down its schools, restaurants, and businesses. As the world went into a state of lockdown, NYC emerged as an early epicenter of the pandemic. This March, two years after the start of the pandemic, I took this photo of NYC’s skyline. The city was bustling with residents and tourists, but the legacy of the pandemic lives on as we mourn those we lost. These past two years have shown us the importance of this year’s journal theme, Planning for Healthy Cities. While NYC and the world has been returning to normalcy, the pandemic is far from over as new variants emerge and cities face obstacles in distributing vaccines, tests, and treatments. The virus has exposed social and racial inequities in our cities and how the built environment can affect our health. May we use the lessons we have learned during this pandemic to rebuild our communities to be healthy, sustainable, and resilient.”

I hope that reading through this journal is as thought-provoking and enjoyable as it was working with the authors.

William Pierce Holloway Editor-in-Chief

5Planning for Healthy Cities

STAFF

EMMA VINELLA-BRUSHER / Managing Editor of Carolina Angles

Emma is a second-year student in the Master of City and Regional Planning and Master of Public Health dual-degree program, interested in reducing transportation barriers to food, healthcare, greenspace, and other vital goods and services. Born and raised in Oakland, CA, she received her BA in environmental studies from Carleton College before spending four years at the U.S. Department of Transportation in Cambridge, MA. In her free time, Emma enjoys running, bike rides, live music, and laughing at her own jokes.

JORDAN APRIL / Contributor

Jordan is a second-year student in the Master of City and Regional Planning and Master of Public Health dual-degree program. They are interested in housing affordability, healthy housing, health equity, and lead poisoning prevention. Jordan received their undergraduate degree in government and international politics from George Mason University. Originally from Upstate New York, they have had prior internships with Legal Services of Central New York, the National Center for Healthy Housing, and the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

RACHEL AUERBACH / Editor

Rachel is a first-year student in the Master of City and Regional Planning and Master of Public Health dual-degree program at UNC. She is interested in the intersections of health, planning, and climate change. Prior to coming to UNC, Rachel worked in development at the World Wildlife Fund. She received her BA in geography from Macalester College, and enjoys hiking, biking, and experimenting in the kitchen.

6 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

RUBY BRINKERHOFF / Editor

Ruby is a second-year master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning. Ruby specializes in land use and environmental planning, with a sustained interest in food systems, climate change, and equitable access to resources. Ruby received a dual bachelor’s degree from Guilford College in biology and religious studies. She loves playing music, exploring North Carolina, and owning a lot of books that she never reads.

LANCE GLOSS / Editor and Incoming Editor-in-Chief

Lance Gloss came to UNC from Colorado to earn his Master of City and Regional Planning. He previously served as managing editor of the Brown University Urban Journal and section editor at The College Hill Independent. While in graduate school he continues to work on land-use planning projects for communities in the West and South.

JAMES HAMILTON / Contributor

James is a first-year master’s student with the Department of City and Regional Planning whose interests center on urban form as it relates to community marginalization, environmental justice, societal cohesion, and suburban retrofit. He studied public policy and economics at Duke University and has since worked in New Orleans and New York before circling back to the triangle. Never happier than when he is hiking up a mountain or traveling on a train, James fails to commit enough time to his average writing collections, ambitious reading list, and lifelong rugby enthusiasm.

WALKER HARRISON / Editor

Walker is a first-year master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning with a focus on transportation planning. He is interested in sustainable mobility, pedestrian and bicycle safety, and international policy transfers to the US context. After earning a BA in geography from UNC-Chapel Hill, Walker worked as a town planner for two years in Spindale, NC. He enjoys playing mandolin, planning his next bike route, and reminiscing on his time as a mascot.

7Planning for Healthy Cities

SARAH KEAR / Contributor

Sarah is a dual-master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC-Chapel Hill and in the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. She earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in political science, gender and women’s studies, and Chicanx and Latinx studies. In her free time, Sarah enjoys running and trying out different recipes.

JOUNGWON KWON / Contributor and Incoming Managing Editor of Carolina Angles

Joungwon is a third-year PhD student in the Department of City and Regional Planning. With a statistics and English literature background, she earned her MA in computational media at Duke University. Her academic interests include visualizations in plans, urban technology, and sustainable cities. She has been part of the Carolina Planning Journal since 2019.

RENE MARKER-KATZ / Editor

Rene came to the Department of City and Regional Planning from University of New Orleans with an undergraduate degree in anthropology, where she was a research analyst exploring the impact of food scarcity during environmental-related disasters. Her academic interests are in hazard resiliency and climate change adaptation in coastal and low-lying areas. Some of her hobbies are herbalism, astronomy, and anything outdoors.

CAMERON MCBROOM-FITTERER / Editor

Cameron is a first-year master’s student in the City and Regional Planning program whose interests include climate change adaptation, coastal hazards, and mass transit. Before moving to North Carolina, he lived in Miami, Florida, where he earned an undergraduate degree in history from the University of Miami and worked for a short time in creative advertising. In his free time, Cameron enjoys playing music, watching good films, and closely following his Miami sports teams.

8 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

SOPHIA NELSON / Contributor

Sophia is a first-year master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning, specializing in transportation planning. She is particularly interested in urban public transit systems and equitable community engagement. Sophia earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Washington, where she studied urban planning, landscape architecture, and geographic information systems.

ISABELLA NIEMEYER / Contributor

Isabella is a first-year master’s candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning with a specialization in housing and community development. She is particularly interested in the intersection between participatory planning, community engagement, and equitable housing reconstruction. She received her undergraduate degree in geography and French from The Ohio State University, and enjoys talking about the Midwest and her dog Percy.

AMY PATRONELLA | Editor

Amy is a first-year Master of City and Regional Planning student. Her upbringing in Houston, TX informs her interest in the nexus of mobility, green space, and climate resilience. She earned an undergraduate degree in political communication with minors in public policy and sustainability from the George Washington University. In her free time, she enjoys reading, biking, and supporting local coffee shops and breweries.

9Planning for Healthy Cities

FEATURE ARTICLES

LEAD EXPOSURE, THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT, AND SOCIAL VULNERABILITY IN NORTH CAROLINA

Elijah Gullett

ELIJAH GULLETT is a fourth-year undergraduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill studying public policy and urban planning. He will be starting his Master of Public Policy degree in the fall of 2022 with a focus on urban policy and infrastructure. He is also currently a research intern with the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory working on environmental justice and energy policy. He is interested in housing policy and economics, environmental health, and demographic change.

ABSTRACT

This article builds on decades of research indicating a connection between adverse outcomes from childhood lead exposure and racial and class inequalities. A representative sample of 31 North Carolina counties is used to understand where elevated childhood blood lead levels (BLLs) occur, and their geographic proximity to poor and aging housing, large low-income populations, and large racial minority populations. The results indicate here is a strong relationship between the age of housing, housing quality, and racial characteristics with elevated childhood BLLs; however, these relationships are not consistent across counties, indicating that sources of lead exposure may be varied in North Carolina due to the potential for industrial point sources of lead.

10 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

INTRODUCTION

The Flint, Michigan water crisis beginning in 2014, caused by leaded water pipes, sparked outrage throughout the world. Videos of brown, undrinkable water flowing from kitchen sink pipes dominated the media. Flint residents, justifiably, blamed Michigan and Flint’s governments for failing their residents. Journalist investigations, as well as public pressure, revealed the source of Flint’s troubles: water infrastructure construction being outsourced and the use of leaded water pipes to transport it to people’s homes and businesses.

The Flint water crisis also sparked a national resurgence in interest in the prevalence of lead in the United States. While Flint’s pipeline replacements are in their final stages, many communities across the US still struggle to control lead exposure (City of Flint, 2021). This article seeks to understand the role that housing segregation along class and racial lines increases risk of lead exposure for low-income Communities of Color. In Flint, those hardest hit by the water crises were typically low-income, minority communities, which is part of a long pattern of marginalized communities being disproportionately affected by poor infrastructure. This article attempts to understand if and where similar patterns arise within North Carolina. To understand this relationship, I use geographic data, as well as housing characteristic data, to identify which North Carolina communities are considered most at risk.

Understanding who in North Carolina is most at risk for lead exposure is essential to combating the health (World Health Organization, 2021), cognitive (Lanphear, et. al., 2005), and behavioral (Liu, 2014) consequences of chronic lead poisoning, especially children,

who will face these consequences for years to come. Understanding the role geography, residential segregation, and spatial inequality play also provides tools for policymakers, planners, and community activists to better target interventions. By addressing spatial inequalities and residential segregation along class and racial lines, it may be easier to fully address the negative health impacts of lead in North Carolina.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

The History of Lead In The US

Lead has been used and found in humanmade materials for centuries, including in pigmented products such as paint and makeup, birth control supplements, as a food preservative, in dishware, and in metal piping for water. The health risks associated with lead exposure have also been known for centuries, as Romans documented the health impacts of lead (despite continuing to heavily rely on it for its aquifer systems). Its use has continued since the Roman era and carried over into the Americas. Indeed, by the 20th century, the US was a leading producer and consumer of lead, and by 1980 the US was consuming 1.3 million tons of lead each year (Lewis, 1985). This figure far exceeded other nations at the time, and much of this consumption was in fuel for automobiles, actively emitting lead into America’s air. Even beyond gasoline, lead was everywhere. It was in the wall paint in people’s homes, it made up the majority of America’s water infrastructure, and it seeped into the soil.

The dangers of lead exposure were well known by the early 20th century, and by the 1980s, regulations were put in place to ban the continued use of lead. By 1970s, unleaded gasoline was put on the market and leaded

11Planning for Healthy Cities

gasoline was completely phased out in 1996. In 1978, consumer goods, including household paints, that contained lead were banned. Programs were implemented in a variety of states to incentive homeowners and landlords to remediate their homes and remove lead paint. Lead was banned in drinking water pipelines by an act of Congress in 1986; however, already existing leaded pipes were allowed to stay in place.

Lead Prevalence in North Carolina

In North Carolina, 10.6% of homes are at risk for lead (America’s Health Ranking, 2021). For children in NC, lead exposure typically comes from leaded paint in homes, however, sources of lead exposure are varied. Other sources include leaded water pipes, untested private wells, nearby industrial facilities, and lead-contaminated consumer goods (NCDHHS, 2020).

The second worst county for childhood lead exposure in 2019 is Beaufort County according to NC Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) records. Beaufort has a relatively high poverty rate at 19.5%, and the per capita income is only $16,722 a year (US Census, 2020). It is a rural county in eastern NC outside of Greenville, and its largest city is Washington, which has a population of just over 19,700. The demographics of Beaufort overall are predominantly white, with white individuals making up over 68% of the county. However, the city of Washington is much more demographically diverse, being almost entirely split between white and Black. Washington is also markedly poorer than the rest of the county, with a per capita income of just over $14,000 and almost 29% of its population living below the poverty line. These features of Beaufort demonstrate the impacts social determinants of health (race and class, in particular) may play in risk of lead exposure.

The Role of Housing in Lead Exposure

As previously mentioned, paint in homes built before 1978 is a major source of lead exposure in the United States, even when lead paint has been painted over (National Center for Healthy Housing, 2021). Children may chip paint off the walls, which allows leaded dust into the air. This dust often settles on childrens’ toys and on the floor, which children often end up ingesting through hand-to-mouth contact. Home remodels that release the leaded paint and dust into the air can also cause a serious risk of lead poisoning for children.

Paint is not the only source of lead in homes either. The soil in yards can become contaminated with lead. Leaded gasoline, when it was still in use, spewed lead into the air, which settled into the soil. Furthermore, nearby industrial activity, building demolitions, and exterior paint chipping can add lead into the soil. This poses a threat especially to children who are likely to engage in normal play activity that involves touching the dirt or playing with toys in the dirt, which then may end up in their mouths. Leadcontaminated soil may also be tracked into the home on shoes and pets’ feet.

Drinking water also poses a major lead exposure threat to communities. The EPA estimates that drinking waters account for 10-20% of human exposure to lead, making it a major hurdle to eliminating lead poisoning in the US (US EPA, 2022). Older homes with leaded pipes, or homes located in communities with outdated water infrastructure, may be at higher risk for lead exposure. The EPA suggests upward of 9.2 million homes are connected to lead service lines (LSLs). In North Carolina alone, there are at least 82,000 LSLs, although this number is likely underreported because reporting of lead pipes is voluntary in NC (NC DEQ, 2016).

12 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

Additionally, much of the lead exposure is likely coming from pipes on private property, which are largely not reported on. While NC requires homeowners to disclose the types of piping in their homes to potential buyers, “lead” is not an option available for description. Interior plumbing, then, is likely a bigger risk for lead exposure than these LSLs (Vaccari, 2016).

These three sources—paint, soil, and leaded pipes—indicate that one of the biggest risk factors for lead exposure is living in an older home, especially in a home still connected to central water systems with leaded pipes. Housing is then at the forefront of the charge to eliminate lead poisoning in the US through remediation, retrofitting, relocation, and potentially demolition.

Historical Racial Disparates and Lead Exposure

It has been broadly observed that environmental health problems fall disproportionately on low-income, minority households. The literature surrounding this comes from public health, geography, economics, and sociology. The social determinants of health —which are defined in this study as racially marginalized groups, low-income individuals, and those living in depreciating urban environments – are key to understanding why certain groups are disproportionately harmed by lead exposure in the home. Previous literature has demonstrated effectively how racial and class disparities drive differences in lead exposure (Sampson & Winter, 2016; Lanphear, et. al., 2005; Leech, et. al., 2016).

A recent dissertation (Kamai, 2021) found that low-income, minority individuals were disproportionately likely to live near point sources of lead pollution in Forsyth

County, NC. Earlier comprehensive research (Carlock, 1993) that analyzed the causes of lead poisoning in NC found housing characteristics, home renovations, and location of home near major highways to be major causes of elevated BLLs.

SIGNIFICANCE

Determining where high-risk communities for lead exposure are located, as well as the role demographic characteristics play in increased risk for lead exposure, is important for state and local policy planners to target lead prevention policies. These factors can influence the public relations work required to provide the public with accurate and effective messaging on lead prevention. For communities and local governments with low capacity, this data will also allow state officials to best allocates funds and resources to assist local communities rehabilitate or demolish buildings that pose a public health risk, as well as ensure limited displacement occurs for low-income residents in toxic communities. Furthermore, individuals and families most impacted by high levels of lead exposure will potentially need decades of healthcare support. Geographic and demographic data allows providers, state and local officials, and community advocates to better target health services to at-risk communities.

Finally, as previously mentioned, the testing rates for every county in North Carolina are low compared to the total population. Increased and improved testing for elevated childhood BLLs is necessary, especially since there is no known safe level of lead in the human body (EPA, 2022). North Carolina officials must intensify and improve their current BLL testing regime to target the most at-risk communities.

13Planning for Healthy Cities

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data Sources

To understand where high risks of lead exposure are in North Carolina, as well as what their likely equity impacts are, three data sources are used: NC Department of Environmental Quality’s (DEQ) 2019 Lead Surveillance Data; the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) (2018), and the 2019 American Community Survey conducted by the US Census Bureau. These datasets provide information on known childhood BLLs in particular counties, as well as census tract and county-level data on demographics, housing characteristics, and, in the case of the CDC’s SVI, aggregate information on public health and natural disaster risks.

Methodology

Data from the aforementioned datasets is matched by location variables, including county-level and census tract-level where possible. Each dataset was mapped using ESRI ArcMap. To analyze patterns that emerge, a geospatial analysis is utilized for several variables, including Black population density, Latino population density, housing built pre-1980, and density of individuals below the poverty. Firstly, a layer is created that demonstrates where the highest rates of elevated childhood BLLs are in North Carolina. The map is then overlaid with demographic and housing characteristic hot spots where clusters of elevated childhood BLLs and these social determinants occur.

This geographical approach is influenced by previous research indicating the high value of geographical methods for targeting specific populations and locations for lead prevention interventions (Kim, 2008).

Compared to previous studies, however, these geographical analyses include data from 31 NC counties to provide a comprehensive view of lead exposure risk throughout the state, as well as census tract-level data for high-risk communities to better understand where the highest risk areas are located. This combination of county-level data to pinpoint hot spots for elevated BLLs, as well as granular data to target specific geographic locations, provides a more holistic picture of lead risk in North Carolina. Furthermore, this research is strengthened by statistical analysis conducted in Stata using the same dataset.

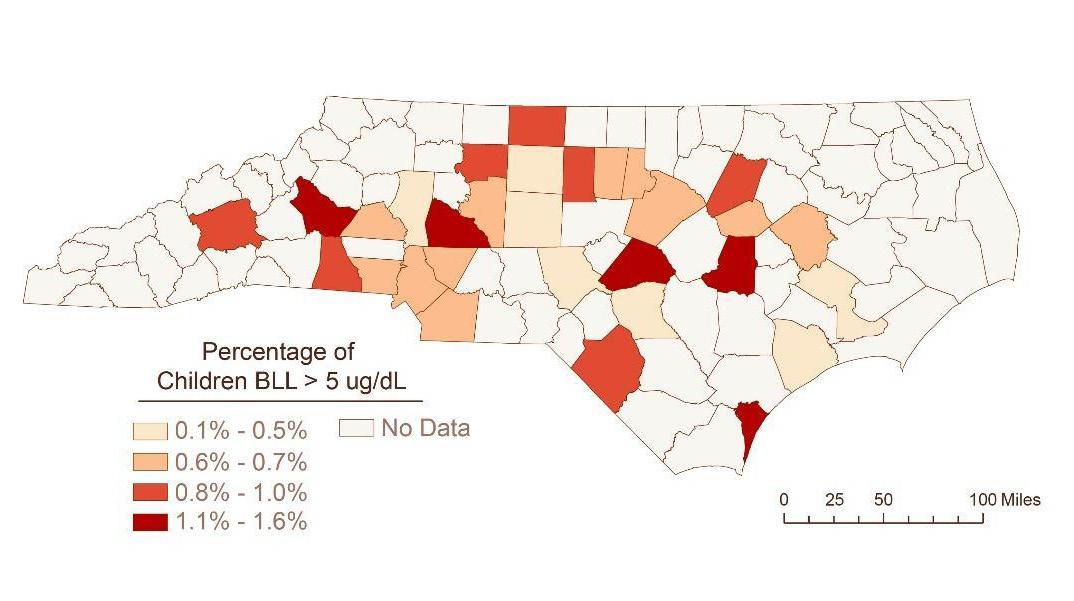

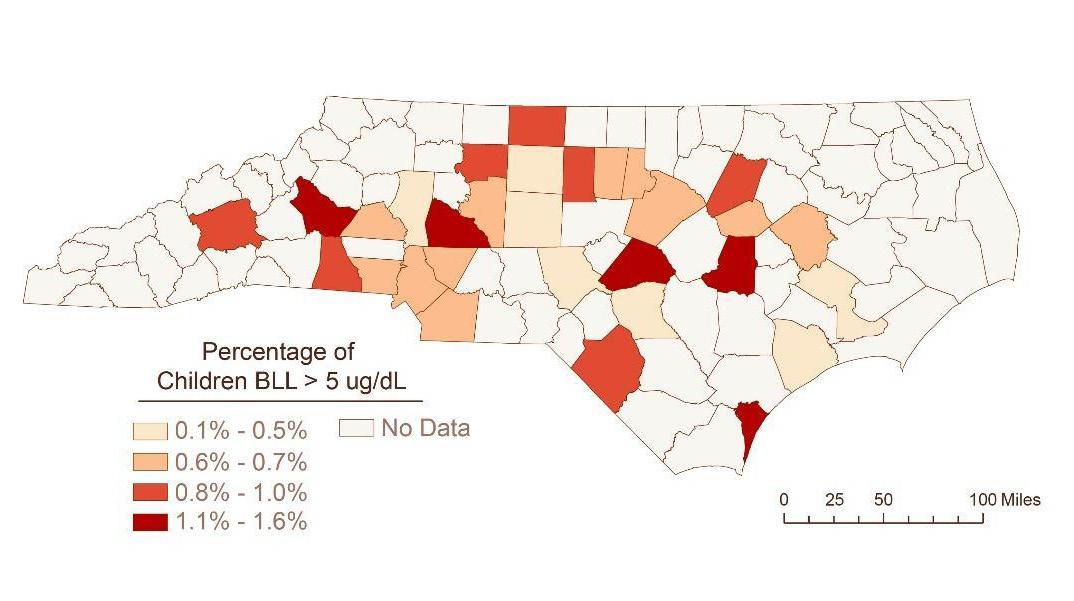

Figure 1 provides an overview of where the highest rates of lead exposure are. Wake, Guilford, Mecklenburg, Durham, and Forsyth stand out as counties with particularly high rates of childhood lead exposure.

Figure 1. Percentage of children with BLL > 5 μg/dL.

After narrowing down specific locations with relatively higher rates of elevated childhood BLLs, the map is zoomed in to better understand circumstances for specific locations based on the proportion of the minority population and the housing characteristics. This is done using the CDC’s SVI along the “Minority Percent” variable, which is the percent minority population, and

14 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

E_HH, which is the percent of the housing stock considered to be in poor quality.

RESULTS

The summary table below details the population of children under three years old, the percentage tested for blood lead levels, and the percentage who were designated as having elevated BLL, which is anything greater than 5 μg/dL for the top five worst counties in NC by percentage.

County Children <72 months of age Children tested Children with bll >5 µg/dl

Vance 3,346 312 (9.3%) 14 (4.5%)

Beaufort 2,832 348 (12.3%) 11 (3.2%)

Lee 4,600 782 (17%) 14 (1.8%)

Burke 5,268 515 (9.8%) 8 (1.6%)

Rowan 9,871 1,281 (13%) 21 (1.60%)

Table 1. County-level data on child blood lead levels greater than 5 μg/dL. Analysis conducted for all counties; however, only the top five worst were included in this table

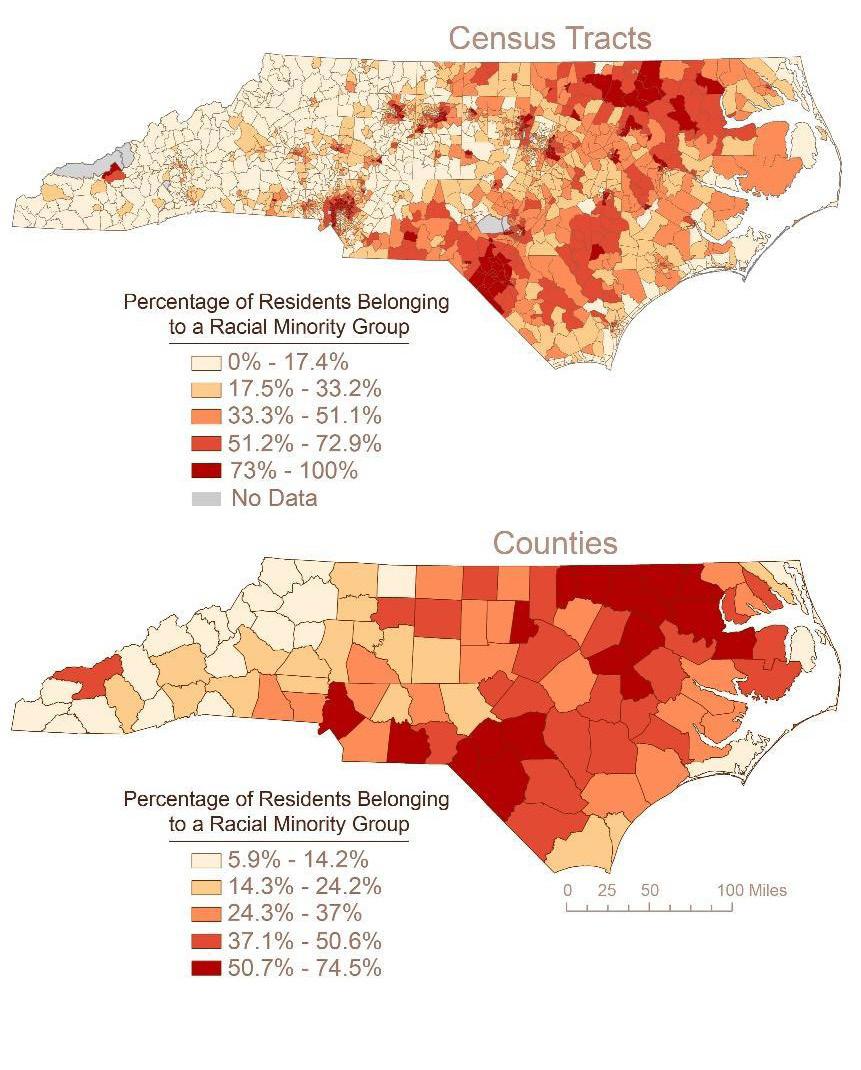

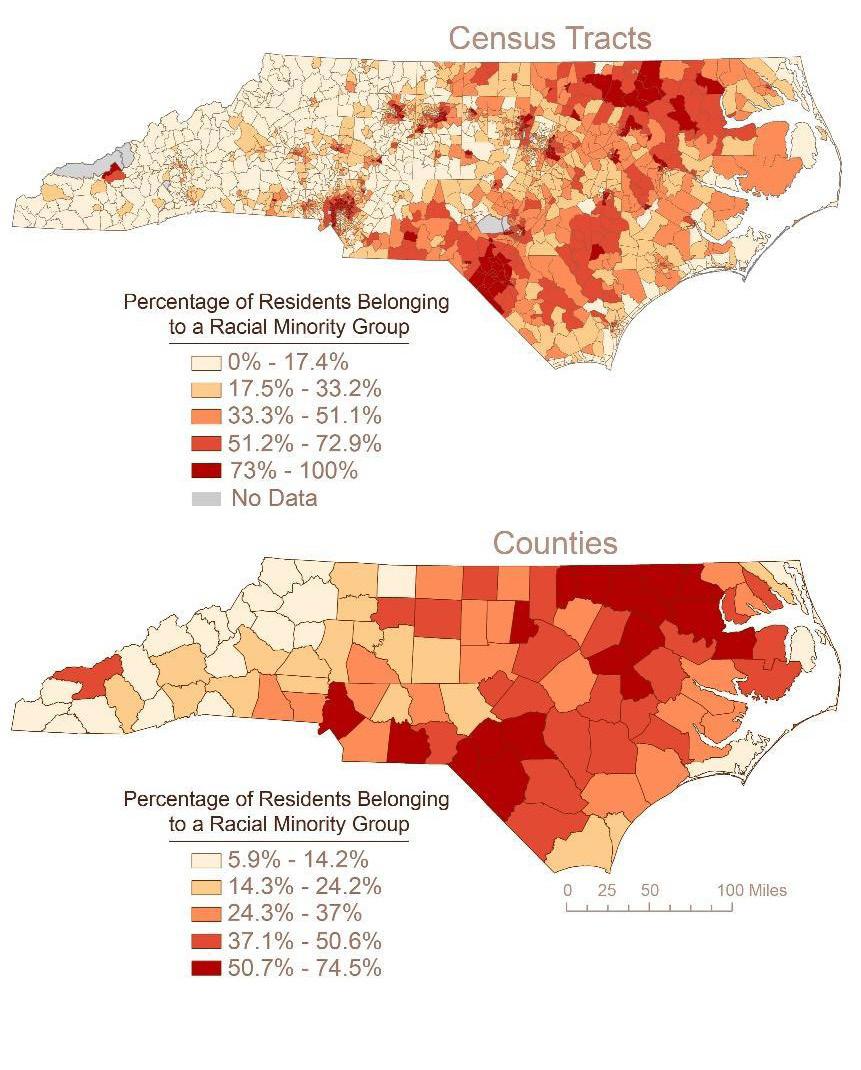

Figures 2, 3, and 4 indicate that there is an association between demographic and housing risk factors and increased prevalence of lead in North Carolina. Firstly, there is a strong clustering between the density of poverty and increased childhood BLLs. Statistical analysis indicates that a one percent increase in the presence of poverty is associated with 3.2 percentage point increase in the percent of children with elevated BLLs. This measure is a proportion, indicating that it is not simply due to population density. Statistical analysis also indicate there to be a relationship between the percent of Black residents and the percent of children with elevated BLLs—specifically a 0.47 percentage

point increase in elevated childhood BLLs. Finally, as was expected, increased numbers of homes built pre-1980 (lead paint in homes was banned in 1978) was also associated with increased rates of elevated BLLs.

Figure 2. Population density analysis of minority percentage at state and county levels.

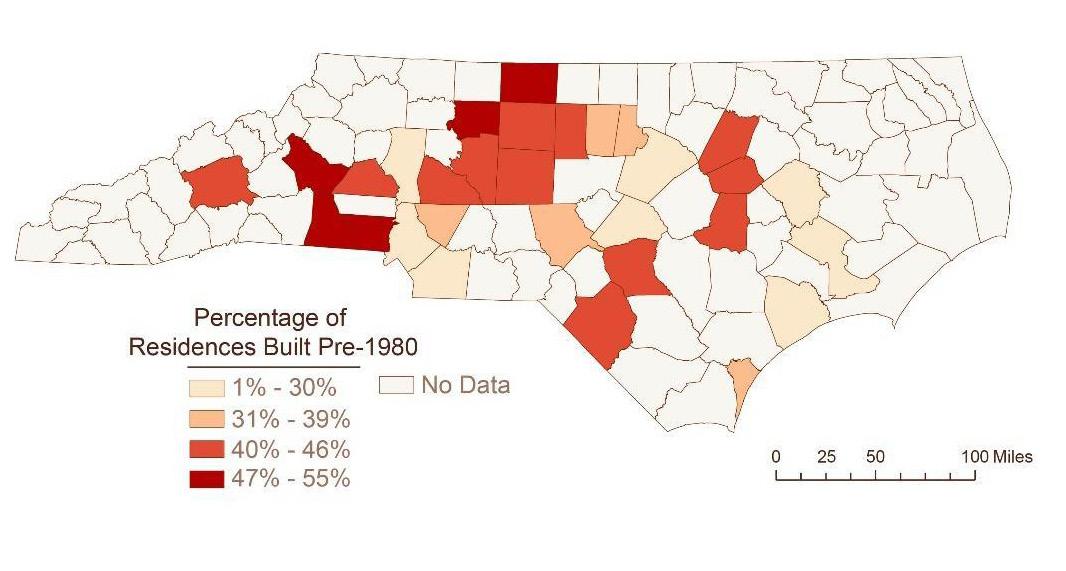

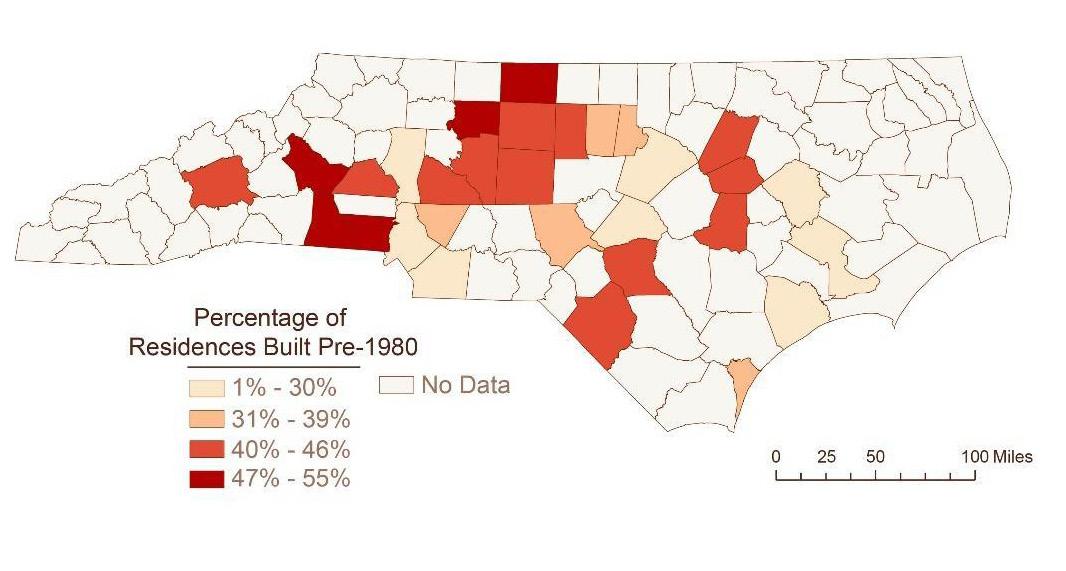

Figure 3 depicts which counties have high concentrations of older homes at higher risk of lead exposure. The statistical analysis indicates that each percentage point increase in homes built before 1980 is associated with a 2.2 percentage point increase in the percent of children with elevated BLLs.

15Planning for Healthy Cities

Figure 3. Geo-spatial analysis of homes built before 1980.

These results indicate that broadly speaking, North Carolina experiences a strong relationship between marginalized class and racial identities and living in high-risk housing environments, increasing their exposure to lead. However, the counties where these trends do not hold (specifically New Hanover and Columbus counties) indicate that there may be alternative sources of lead exposure, particularly industrial sources, that causes elevated BLLs in children.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

These results are only associations and not indicative of causality; however, consistent patterns emerge. There appears to be relatively strong relationships between demographic minorities, low-income communities, poor housing conditions, and elevated blood lead levels in children. The literature supports these findings, and the above results support that these relationships persist in North Carolina at the county and census tract levels.

Policymakers, planners, and community advocates should take these results as a call to action. Low-income, minority communities are disproportionately harmed by household lead exposure, often caused by lowquality, aging housing units. As President Biden’s implements the Build Back Better legislation, which includes provisions for lead remediation, NC and local level officials should be taking immediate action to address lead exposure in all NC communities. These interventions include targeted public relations messaging, home remediation, expanding the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, expanding BLL testing, and mandatory reporting for counties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Cartography by Tia Francis, Digital Research Services Specialist at the University Libraries at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

16 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

REFERENCES

America’s Health Rankings, 2021. https://www. americashealthrankings.org/explore/health-ofwomen-and-children/measure/housing_leadrisk/ state/NC

Carlock, David M. 1993. Determination of the Sources of Low-Level Lead Poisoning In North Carolina Children. https://doi.org/10.17615/07b0-7e46

City of Flint, 2021. https://www.cityofflint.com/ gettheleadout/

Environmental Protection Agency, 2022. Basic Information about Lead in Drinking Water. https:// www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/ basic-information-about-lead-drinking-water

Kamai, Elizabeth. (2021). Lead and Children in North Carolina: Patterns of Lead Testing across the State and a Case Study of Point Sources in Forsyth County, North Carolina. Gillings School of Global Public Health, Department of Epidemiology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17615/0sc9-v126

Kim, Dohyeong, M. Alicia Overstreet Galeano, Andrew Hull, and Marie Lynn Miranda. “A Framework for Widespread Replication of a Highly Spatially Resolved Childhood LeadExposure Risk Model.” Environmental Health Perspectives 116, no. 12 (2008): 1735–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25165531

Lanphear, B. P., Hornung, R., Khoury, J., Yolton, K., Baghurst, P., Bellinger, D. C., Canfield, R. L., Dietrich, K. N., Bornschein, R., Greene, T., Rothenberg, S. J., Needleman, H. L., Schnaas, L., Wasserman, G., Graziano, J., & Roberts, R. (2005). Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environmental health perspectives, 113(7), 894–899. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7688

Leech, T. , Adams, E. , Weathers, T. , Staten, L. & Filippelli, G. (2016). Inequitable Chronic Lead Exposure. Family & Community Health, 39 (3), 151-159. doi: 10.1097/ FCH.0000000000000106.

Lewis, J. (1985). Lead Poisoning: A Historical Perspective. https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/ lead-poisoning-historical-perspective.html

Liu J, Liu X, Wang W, McCauley L, Pinto-Martin J, Wang Y, Li L, Yan C, Rogan WJ. 2014. Blood lead levels and children’s behavioral and emotional problems: a cohort study. JAMA Pediatr; doi:10.1001/ jamapediatrics.2014.332.

Occupation & Environmental Epidemiology, N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2020. https://epi.dph.ncdhhs.gov/oee/ a_z/lead.html

Sampson, R.J. & Winter, A.S. (2016). The Racial Ecology of Lead Poisoning. Du Bois Review, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ du-bois-review-social-science-research-onrace/article/racial-ecology-of-lead-poisoning/ F39AF4724258606DCC1CDA369DC08707

World Health Organization. 2021. Lead Poisoning. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ lead-poisoning-and-health

17Planning for Healthy Cities

HOW PLANNERS ADDRESS EXTREME HEAT WITH EQUITABLE RESILIENCE

Emily Gvino, MCRP, MPH / Julia Maron, MCRP

EMILY GVINO is an Associate with Clarion Associates in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. After graduating from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Master of Public Health and Master of City and Regional Planning dual-degree program, she worked for the Belmont Forum-funded grant, Re-Energize Governance of Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience for Sustainable Development. As an environmental planner and public health professional, her work focuses on the intersections of climate justice, disaster resilience, health equity, and environmental and land use planning.

JULIA MARON is a Climate Resilience Planner with Kleinfelder in Raleigh, North Carolina and is graduating with a master’s from the City and Regional Planning Department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in May 2022. She also worked for the Belmont Forum-funded grant, Re-Energize Governance of Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience for Sustainable Development. As an aspiring resilience planner, she plans to work at the intersection of environmental conservation and disaster resilience, with a focus on utilizing natural and nature-based methods to address hazards.

ABSTRACT

Problem, Approach, and Findings

Extreme heat is one of the most concerning natural hazards facing cities today, forecasted to increase in frequency, duration, and intensity in the future. With close to 3.5 billion people projected to be impacted worldwide by extreme heat by 2070, it is critical that efforts focus on planning and adapting our built urban environment to reduce the risks that people will face from heat waves. A lack of data and monitoring has left uncertainty surrounding the full impact to people’s health

18 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

from extreme heat. Currently, planners are undertaking important work to understand how extreme heat disproportionately affects communities historically discriminated against in planning practices.

Implications

This article looks at how local planners and municipalities, primarily in urban communities, can best address extreme heat within the lens of equitable resilience. Planners must go beyond unenforceable comprehensive plans to zoning regulations and unified development ordinances to change and adapt to threats posed by hazards. Equitable stakeholder engagement and environmental justice must be incorporated into the process, centering those with power and those most impacted, as these people will have the most at stake.

INTRODUCTION

Climate change is a cross-cutting issue that impacts urban environments across many disciplines and sectors. Leading practitioners in public health and health research institutions have already identified climate change as the greatest threat to global public health (Choi-Schagrin 2021; Maibach et al. 2010). An unprecedented statement published by over 200 medical journals globally called for interdisciplinary action to address the social and economic determinants of health impacted by climate change (Atwoli et al. 2021)

One of the most critical and urgent threats to healthy cities is the risk of natural hazards, as climate change is altering the frequency and severity of severe weather (Masson-Delmotte et al. 2021). Climate resilience resides at the intersection between planning and health and seeks to promote healthier and more

equitable living conditions for urban residents. This intersection will become increasingly important as cities cope with acute events such as severe storms and hurricanes and longer-term impacts such as higher average temperatures, chronic flooding, and changing precipitation patterns.

Of all climate hazards, extreme heat causes the most health risks in the United States (Meerow and Keith 2021). The unusual increase in the number of deaths in a given population, termed excess mortality, is a particular concern for urban environments impacted by extreme heat (Smith 2020). Heat waves are increasing in frequency, duration, and intensity (Manaloto 2021); 2020 was the second warmest year on record globally (Bateman 2020). The Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance—a global, crosssectoral collaboration addressing urban heat challenges—estimates that extreme heat will impact more than 3.5 billion people by 2070. Of these, 1.6 billion will be residents of urban areas. Extreme heat is known as the ‘silent killer’ due to a lack of data and monitoring. There is uncertainty around how many people die from heat, which health conditions are most exacerbated by it, and whether current policies are effective in addressing heatrelated health impacts (Owen-Burge 2021) This hazard deserves particular attention given the reality that temperature warming will continue to increase for many decades, even with intensive emissions reduction (Sherman 2020).

Urban heat islands are the phenomena of higher temperatures in cities (compared to rural communities) resulting in part from the high concentrations of paved surfaces, along with limited tree canopy and green space, often seen in urban development

19Planning for Healthy Cities

(Meerow and Keith 2021; Jones, Dunn, and Balk 2021; Wilson 2020). Importantly, extreme heat is an environmental justice concern, disproportionately affecting communities that have experienced historical patterns of discrimination and disinvestment (Wilson 2020). Researchers have analyzed patterns of disinvestment and racist policies—specifically redlining—as determinants for the health impacts of extreme heat (Plumer, Popovich, and Renault 2020; Wilson 2020; Wolch, Byrne, and Newell 2014). Early practices of segregating Black and white communities, followed by redlining, caused social and environmental inequity impacting nonwhite residents in current urban forms, like less tree canopy and green space (Maller and Strengers 2011; Lawrence 2004; Grove et al. 2017). These inequities have compounded issues of access to green space, distribution of resources, urban design and investment, and other factors that comprise the built environment. Planning at the local level is integral for addressing equitable resilience and promoting adaptation. Tools like comprehensive plans as well as local zoning, codes, and ordinances can mitigate the impacts of extreme heat by planners promoting equitable resilience and locally led adaptation. Augmentation of urban vegetation and other urban design strategies can also decrease extreme heat risk at the local level. For planning strategies to remain equitable, these mechanisms must be coupled with vulnerability assessment and equity analysis, integrating public health concepts to fully understand who is being impacted and how to implement solutions.

EQUITABLE APPROACH TO RESILIENCY: INTERNATIONAL POLICY CONTEXT

Addressing the ingrained systems of injustice and inequity within social determinants of health, and the resulting vulnerability of priority populations, must underpin any resilience efforts. The concept of equitable resilience requires a transformation of current systems and mindsets about resilience, taking “into account issues of social vulnerability and differential access to power, knowledge, and resources” (Matin, Forrester, and Ensor 2018). The Resilient Nation Partnership Network, FEMA, and NOAA published the 2021 report, “Building Alliances for Equitable Resilience,” garnering key insights from diverse stakeholders on community resilience and equity (Willis et al. 2021). As the repercussions of climate change challenge our cities, establishing equitable frameworks for heat resilience will be increasingly vital.

Planners can look to several policy frameworks from the global stage for context on addressing equitable heat resilience, especially from the United Nations (UN). The 2015 Paris Agreement was a monumental step forward in this arena, mandating universal commitment to climate neutrality through multilevel, multi-stakeholder action (BerrangFord et al. 2019; Roberts 2016).

The Sendai Framework, which focuses on the health impacts of natural hazards, was adopted at the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in 2015. The Sendai Framework established four priorities for action following the Paris Agreement: 1) understand disaster risk; 2) strengthen disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk; 3) invest in disaster

20 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

risk reduction for resilience; and 4) enhance disaster preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction 2021). The ambitious goals imagine a world that is safer, healthier, and more equitable by 2030: one that decreases mortality and impacts to people, reduces economic and infrastructure damages, bolsters local risk reduction strategies, improves global cooperation, and augments early warning systems (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction 2021).

In 2016, the New Urban Agenda was adopted by the UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) and endorsed by the UN General Assembly. The focus of the New Urban Agenda is “equal rights and access to the benefits and opportunities that cities can offer”, highlighting the role of subnational and local governments in accomplishing these goals. Quantitative measures are included for the transport and mobility, energy solid waste, and water/sanitation sectors. The New Urban Agenda promotes intervention mechanisms in land, housing, and revitalization policies, urban design, municipal finance, and urban governance. As such, planners have a clear, global mandate from climate experts to focus on disaster risk reduction and resilience in their work. As cities grapple with these complex challenges, health equity and stakeholder engagement must be the primary focus in implementing intersectional, inclusive, and effective solutions. Pivotal to this work is equitable stakeholder engagement, which underpins the current roles and responsibilities of planners working at the local level across

the United States. The International Institute for Environment and Development aptly describes this imperative for “local governments to shift away from ‘development as usual’—to development planning that places climate at its heart, champions bottom-up community participation and values local knowledge” (Soanes 2021a) Hundreds of governments and institutions are committed to locally-led climate adaptation, having signed on to these principles (and committed significant funding) at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (Soanes 2021b, 2021a; Owen-Burge 2021).

The Belmont Forum-funded grant project, Re-Energize Governance of Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience for Sustainable Development , established the UNC Snow Angel Method. This novel approach to stakeholder engagement re-thinks traditional processes to invigorate locallyled resilience. The UNC Snow Angel Method combines snowball and purposive sampling methods with the idea that better-informed decisions are the result of equitable engagement that encompasses people from priority groups. This approach advocates for the greater involvement of stakeholders in decision-making, garnering more rooted community support, and improving implementation. The snowball method starts with a few defined stakeholders and asks them to identify new organizations and other contacts. While this is helpful for researchers, this method can unintentionally limit the scope of included stakeholders.

In comparison, while the UNC Snow Angel Method specifically recognizes the need to include a wide number of stakeholders, it centers those with power and those most impacted. This method is an attempt to

21Planning for Healthy Cities

prioritize the need for broad stakeholder input while simultaneously recognizing that those most impacted (or vulnerable) have the deepest stake in the issues at hand. NOAA’s National Integrated Heat Health Information System heat mapping campaign, conducted across 11 states by local organizations, is an excellent example of a community-based equitable engagement approach. During the Summer of 2021 in Durham County, North Carolina, the community-led campaign recorded and mapped heat data in Durham and Raleigh on the hottest summer days (Freid 2021; Cawley 2022). Within Durham County, the project focused on eight identified census tracts where redlining, racism, and historic inequity have resulted in marked and disproportionate health risks for people of color and lower-income community members.

The project would not be possible without an extensive network of community volunteers and local partners. To support data collection, the volunteers traversed the cities by car and bike to better understand how heat is impacting residents. The data will be integrated with community demographic information to understand social vulnerability. From a policy standpoint, this project will be integrated into the first-ever climate change chapter in the Community Health Assessment from the Partnership for a Healthy Durham. This work is also founded in Durham County’s Strategic Planning goals.

APPLICATION TO PLANNING PRACTICE

When addressing extreme heat in the context of equitable resilience, local level planners have a variety of tools at their disposal. Of course, every planner faces a complicated decision-making process prioritizing community feedback and balancing local climate change impacts, funding, resources, and capacity. Following the inspiration of the landmark Sustainable Development Code, we present a framework of “good-better-best” planning practices that can move the needle in mitigating extreme heat (Rosenbloom and Adams 2019).

COMPREHENSIVE AND CLIMATE PLANS—GOOD

In the United States, comprehensive plans are foundational for determining community goals and guiding future actions for individual jurisdictions. Generally, these planning documents look at existing conditions and issues, set goals and objectives to address the issues, determine implementation strategies, and guide future land use decision-making. Increasingly, cities and states are creating climate adaptation and resilience plans that will help stakeholders anticipate, prepare for, adapt to, and recover from the impacts of climate change (Environmental Protection Agency 2021). As with comprehensive plans, climate adaptation and resilience plans lay out strategies to address hazards and their associated risks to vulnerable groups. Many states have local or regional plans that address climate adaptation, and few have state-led adaptation plans (Georgetown Climate Center 2021). While increasingly common, climate action plans tend to focus on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

22 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

Comprehensive and climate plans generally require collaborative efforts to identify current issues and offer objectives and goals. However, these planning documents often lack legally enforceable standards that ensure progress towards the desired goals. When these plans are not referenced during decision-making, they fail to reach their full potential. Therefore, we believe comprehensive and climate plans are only good when it comes to addressing extreme heat and equitable resilience.

INTEGRATED RISK ASSESSMENTS—BETTER

A better approach for municipal governments and local planners is to integrate extreme heat risk assessments with comprehensive plans or unified development ordinances. While comprehensive plans provide overall guidance through goals, policies, and programs, they lack enforceability and leave substantial discretion for how they are implemented. In contrast, unified development ordinances combine zoning regulations with other management or design regulations, providing the enforcement and implementation tools that comprehensive plans lack. By integrating extreme heat risk assessments into these documents, municipalities are armed with the “how” or “how much” behind the “why.”

The City of Baltimore’s Disaster Preparedness and Planning Project (“Disaster Plan”) was produced by the Department of Planning in 2013 and ultimately adopted in 2018. Baltimore is currently in the process of completing their Master Plan 2030, presenting a great opportunity for Baltimore to integrate the hazard risk assessment into their comprehensive plan process. The Disaster

Plan recommends increasing urban tree canopy to 40% by 2037, which would reduce the effect of extreme heat on communities. An additional recommendation is to increase green space in vacant lots, which would reduce impervious surface and provide new opportunities for shade (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions 2017)

PHYSICAL LAND USE CHANGES—BEST

The term “urban heat management” refers to proactive engagement by local governments to reduce the intensity and duration of heat exposure through tree planting, use of cooling materials, and similar activities (Stone et al. 2019). While comprehensive plans, heat action plans, and integrated risk assessments provide the foundation to mitigate extreme heat, physical land use changes through urban heat management will result in tangible health impacts for communities. As previously mentioned, lagging national and global action to reduce greenhouse gases means that extreme heat will be a regular reality, particularly for lower-income and BIPOC communities. Planners face an imperative to retrofit, redesign, and rethink the current urban environment to relieve these health impacts as quickly as possible.

To best reduce risk to extreme heat for vulnerable groups and provide equitable resilience, municipalities need to examine ordinances and zoning regulations to determine what is and is not being enforced. Related to extreme heat, these elements should be examined first: tree protection and retention, green and open space preservation, cooling pavement, and cooling roofs. For example, the City of Raleigh received a clean

23Planning for Healthy Cities

technology pavement award from NCDOT for reducing urban heat island effect and preserving pavement through titanium oxide treatments. Treated roads showed a 37% reduction in nitrous oxides—a roadway contaminant—as well as a nearly 400% improvement in the average Solar Reflective Index compared to untreated locations (Cawley 2022; Carleton 2021). This work by the City of Raleigh demonstrates how data-driven physical interventions can promote equity in green infrastructure.

The New Urban Agenda calls for two actionable changes relevant to urban heat management land use policy: 1) providing of rebates or tax credits for new development that include cool and green roofs and 2) creating an expedited permitting process for developments that meet density requirements (United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development 2016). Gold-star renovations of municipally owned buildings, the Agenda suggestions, can demonstrate the feasibility of these project in local development markets. In addition, developing building retrofit incentive programs can vastly decrease heat-related illness and mortality.

Houston, Philadelphia, and Louisville have also taken action in urban heat management. Houston required cool roofing provisions in 2016 for commercial buildings, and Philadelphia passed an ordinance requiring white or reflective Energy-Star approved materials for new or renovated buildings (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions 2017). An innovative expansion of these kinds of requirements is the installation of cool pavements, which lower surface temperatures and mitigate health impacts (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions

2017). Louisville experienced a deadly heat wave in 2012 that prompted city action (Stone et al. 2019). The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions commended their multi-pronged approach, which will include a climate and health assessment, a cool roof rebate program, and cool roof installation on parking garages and park buildings. The city completed an Urban Tree Assessment and hired a forester, aiming for 45% tree canopy citywide and focusing on disinvested neighborhoods (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions 2017, Boyle 2020).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LOCAL PLANNERS

Local planners are key leaders in helping their communities address the challenges climate change poses to people and the environment. The planning profession works at the intersection of sectors that are critical to hazard mitigation and adaptation – land use, public health, development, and transportation. Interdisciplinary collaboration amongst these sectors is necessary for advancing equitable resilience. Based on issues identified in the comprehensive and climate plans, local planning departments can re-evaluate zoning regulations and unified development ordinances within the lens of climate change adaptation. A strategy that can be effective is overlay zoning for specific hazards or establishing a “resilience zone” overlay. This applies additional standards to the defined boundary, which can be specific to hazards like extreme heat or flooding. The hazard and resilience overlay can dictate land use regulations, permitted uses, and construction types which creates opportunities to address equitable resilience strategies. The Boston Planning &

24 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

Development Agency (BPDA) adopted the Coastal Flood Resilience Overlay District (CFROD) in October 2021 (Boston Planning & Development Agency 2021; Hughes 2021). The CFROD aims to protect portions of the City of Boston where 40 inches of sea level rise is expected in a 1% chance storm event. The CFROD implements updated Design Guidelines, new flood elevation requirements, and standards for building uses. The BPDA also added a Resilience Reviewer to advise development project alignment with climate policies, following their Climate Ready Boston plan (Boston Planning & Development Agency 2021). Similarly, the city of Norfolk, Virginia established a Coastal Resilience Overlay Zone and Upland Resilience Overlay, both of which were adopted in 2018 and requires developers to address risk reduction, stormwater management, and energy resilience through use of a flexible pointsbased system (Sharp 2021)

Local level prioritization of funding for climate action is critical. According to the International Institute of Environment and Development, less than 10% of global climate funds are committed to climate action at the local level (Soanes 2021a). This lack of funding leads to critical gaps in action for communities most impacted by extreme weather and climate events. We recommend re-tooling planning finance mechanisms to fund urban heat management strategies. For example, the New Urban Agenda highlights tax increment financing and special assessment districts as land value capture tools for climate resilience (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions 2017)

Additionally, stakeholder engagement should center those with power and those who are most impacted, as those most vulnerable will likely have the deepest stake in the issue. Community involvement around extreme heat risk reduction and comprehensive planning is critical, and efforts must ensure that the appropriate people are fully brought into the process. Stakeholder engagement activities may look like in-person workshops, virtual meetings held at varied times and utilizing the UNC Snow Angel Method to reach vulnerable groups.

CONCLUSION

Planners have the tools and ability to help communities increase their resilience to extreme heat. Zoning regulations, unified development ordinances, and financing incentives should be used—in tandem with equitable stakeholder engagement—to make changes to land use that ultimately work well in alleviating heat in urban areas.

25Planning for Healthy Cities

REFERENCES

Atwoli, Lukoye, Abdullah H. Baqui, Thomas Benfield, Raffaella Bosurgi, Fiona Godlee, Stephen Hancocks, Richard Horton, et al. 2021. “Call for Emergency Action to Limit Global Temperature Increases, Restore Biodiversity, and Protect Health.” The New England Journal of Medicine, September. https://doi. org/10.1056/NEJMe2113200.

Bateman, John. 2021. “2020 Was Earth’s 2nd-Hottest Year, Just behind 2016.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 14, 2021. https://www.noaa.gov/news/2020-was-earth-s-2ndhottest-year-just-behind-2016

Berrang-Ford, Lea, Robbert Biesbroek, James D. Ford, Alexandra Lesnikowski, Andrew Tanabe, Frances M. Wang, Chen Chen, et al. 2019. “Tracking Global Climate Change Adaptation among Governments.” Nature Climate Change 9 (6): 440–49. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41558-019-0490-0.

Boston Planning & Development Agency. 2021. “Flood Resiliency Building Guidelines & Zoning Overlay District.” Boston Planning & Development Agency. September 2021. https://www.bostonplans.org/ planning/planning-initiatives/flood-resiliencybuilding-guidelines-zoning-over.

Boyle, John. 2020. “Louisville Group Works To Replenish Urban Tree Canopy.” WFPL News Louisville, December 29, 2020.

Carleton, Audrey. 2021. “Cities Are Spraying Asphalt With This Chemical to Cool Urban Heat Islands.” Vice, June 30, 2021.

Cawley, Max. 2022. “Raleigh/Durham HeatWatch UHI Data Release.” presented at the Museum of Life + Science, February 3.

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. 2017. “Resilience Strategies for Extreme Heat.” Arlington, Virginia: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. https://www.c2es.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ resilience-strategies-for-extreme-heat.pdf

Choi-Schagrin, Winston. 2021. “Medical Journals Call Climate Change the ‘Greatest Threat to Global Public Health.’” The New York Times, September 7, 2021.

Environmental Protection Agency. 2021. “Climate Adaptation.” United States Environmental Protection Agency. October 7, 2021. https://www. epa.gov/climate-adaptation.

Freid, Tobin. 2021. “Durham County Joins NOAA, City of Raleigh and Community Partners to Map Urban Heat Islands.” Durham County News, May 13, 2021. https://www.dconc.gov/Home/Components/News/ News/8291/.

Georgetown Climate Center. 2021. “State and Local Adaptation Plans.” Georgetown Climate Center. November 4, 2021. https://www.georgetownclimate. org/adaptation/plans.html.

Grove, Morgan, Laura Ogden, Steward Pickett, Chris Boone, Geoff Buckley, Dexter H. Locke, Charlie Lord, and Billy Hall. 2017. “The Legacy Effect: Understanding How Segregation and Environmental Injustice Unfold over Time in Baltimore.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2 4694452.2017.1365585.

Hughes, Liz. 2021. “BPDA Votes to Advance City’s Coastal Flood Resilience Zoning Overlay District.” Boston Agent Magazine, September 20, 2021. Jones, Bryan, Gillian Dunn, and Deborah Balk. 2021. “Extreme Heat Related Mortality: Spatial Patterns and Determinants in the United States, 1979–2011.” Spatial Demography 9 (1): 107–29. https://doi. org/10.1007/s40980-021-00079-6.

Lawrence, Roderick J. 2004. “Housing and Health: From Interdisciplinary Principles to Transdisciplinary Research and Practice.” Futures 36 (4): 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2003.10.001.

Maibach, Edward W, Matthew Nisbet, Paula Baldwin, Karen Akerlof, and Guoqing Diao. 2010. “Reframing Climate Change as a Public Health Issue: An Exploratory Study of Public Reactions.” BMC Public Health 10 (June): 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/14712458-10-299.

Maller, Cecily J, and Yolande Strengers. 2011. “Housing, Heat Stress and Health in a Changing Climate: Promoting the Adaptive Capacity of Vulnerable Households, a Suggested Way Forward.” Health Promotion International 26 (4): 492–98. https://doi. org/10.1093/heapro/dar003.

Manaloto, Jen. 2021. “Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance.” Atlantic Council; Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center at the Atlantic Council. https://uploads-ssl.webflow.

Masson-Delmotte, V, P Zhai, A Pirani, S L Connors, C Péan, S Berger, N Caud, et al., eds. 2021. “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.” Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/#SPM.

Matin, Nilufar, John Forrester, and Jonathan Ensor. 2018. “What Is Equitable Resilience?” World Development 109 (September): 197–205. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.04.020.

Meerow, Sara, and Ladd Keith. 2021. “Planning for Extreme Heat: A National Survey of U.S. Planners.” Journal of the American Planning Association,

26 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

December, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.20 21.1977682.

Owen-Burge, Charlotte. 2021. “‘It Is in Cities Where the Battle against Climate Change Will Be Defined.’” UNFCCC Race to Resilience. November 11, 2021. https://racetozero.unfccc.int/it-is-in-cities-wherethe-battle-against-climate-change-will-be-defined/.

Plumer, Brad, Nadja Popovich, and Marion Renault. 2020. “How Racist Urban Planning Left Some Neighborhoods to Swelter.” The New York Times, August 26, 2020. https://www.nytimes. com/2020/08/26/climate/racist-urban-planning. html?auth=login-email&login=email.

Roberts, Debra. 2016. “The New Climate Calculus: 1.5°C = Paris Agreement, Cities, Local Government, Science and Champions (Plsc2 ).” Urbanisation 1 (2): 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455747116672474.

Rosenbloom, Johnathan, and Bradley Adams, eds. 2019. “Sustainable Development Code.” Sustainable Development Code. https://sustainablecitycode.org/ about/

Sharp, Jeremy. 2021. “Zoning Ordinance Overhauled to Increase Community Resilience to Flooding.” NOAA Office for Coastal Management. April 21, 2021. https://coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/training/norfolkzoning-ordinance.html

Sherman, Amy. 2020. “The Heat Is On.” Planning Magazine, September. https://www.planning.org/ planning/2020/aug/the-heat-is-on/.

Smith, Adam B. 2020. “2010-2019: A Landmark Decade of U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters.” NOAA Climate.Gov. January 8, 2020. https://www. climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/20102019-landmark-decade-us-billion-dollar-weatherand-climate.

Soanes, Marek. 2021a. “Principles for Locally-Led Adaptation.” International Institute for Environment and Development. November 2021. https://www. iied.org/principles-for-locally-led-adaptation.

———. 2021b. “Significant New Support for Locally-Led Adaptation Principles.” International Institute for Environment and Development. November 8, 2021. https://www.iied.org/significant-new-support-forlocally-led-adaptation-principles.

Stone, Brian, Kevin Lanza, Evan Mallen, Jason Vargo, and Armistead Russell. 2019. “Urban Heat Management in Louisville, Kentucky: A Framework for Climate Adaptation Planning.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, October, 0739456X1987921. https://doi. org/10.1177/0739456X19879214.

United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development. 2016. “New Urban Agenda.” United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III).

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021. “What Is the Sendai Framework?” United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. December 2021. https://www.undrr.org/ implementing-sendai-framework/what-sendaiframework.

Willis, Chauncia, Monica Sanders, Jo Linda Johnson, S. Atyia Martin, Valerie Novack, Anna Marandi, Jake White, and Nikki Cooley. 2021. “Building Alliances for Equitable Resilience: Advancing Equitable Resilience through Partnerships and Diverse Perspectives.” United States Federal Emergency Management Agency. https://www.fema.gov/sites/ default/files/documents/fema_rnpn_buildingalliances-for-equitable-resilience.pdf.

Wilson, Bev. 2020. “Urban Heat Management and the Legacy of Redlining.” Journal of the American Planning Association, May, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.108 0/01944363.2020.1759127.

Wolch, Jennifer R., Jason Byrne, and Joshua P. Newell. 2014. “Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough.’” Landscape and Urban Planning 125 (May): 234–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. landurbplan.2014.01.017.

27Planning for Healthy Cities

EXPANDING CRASH DATA ANALYSIS Defining Crash Risk for Non-Motorized Users

Daniel Capparella / Jessica Hill, AICP, PMP / Ashleigh Glasscock

DANIEL CAPPARELLA has been with GNRC since August of 2019. He currently serves as the Active Transportation Planner and coordinates the bike and pedestrian elements of transportation planning carried out by the organization. Prior to joining GNRC, he worked at the Los Angeles Community Action Network, a homelessness advocacy organization in the Skid Row Community and greater Los Angeles metropolitan area. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in urban and environmental policy from Occidental College.

JESSICA HILL serves as the community and regional planning director for the Greater Nashville Regional Council. With more than 14 years of experience in local and regional government, Jessica excels at building partnerships across government and business sectors. She holds a Master of City and Regional Planning from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Master of Business Administration from Wake Forest University.

ASHLEIGH GLASSCOCK has been with GNRC since December 2018. She serves as a senior research analyst, working to assess a variety of datasets, create maps, data visualizations, and perform data analysis in support of GNRC’s programs. She helps support programs related to demographics, development, infrastructure, natural resources, and quality of life. Prior to joining GNRC, she attended East Tennessee State University where she received her master’s degree in geoscience with a concentration in geospatial analysis.

28 CAROLINA PLANNING JOURNAL

ABSTRACT

Problem Approach and Finding

The Nashville region has a troubling trend. Since 2015, pedestrian fatalities have almost doubled. While serious motorized injuries were nearly cut in half, non-motorized serious injuries remained constant. These trends have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the recent surge in active transportation activity in the region and limited funding available for bicycle and pedestrian improvements, a more systemic and focused approach must be utilized to identify and prioritize solutions for improving safety for bicyclists and pedestrians.

This article presents a non-motorized risk index that provides a system-level tool to proactively identify areas with unsafe nonmotorized conditions to better guide planning and prioritize solutions for bicyclists and pedestrians.

Implications

By demonstrating the ability to identify unsafe conditions for bicyclists and pedestrians across the Nashville region’s transportation network beyond a hot spot analysis, this index can help inform future investments that improve safety for all users of the transportation network and provide a framework to expand areas considered for non-motorized safety improvements.

INTRODUCTION

The built environment, which includes the transportation network that facilitates movement and mobility, is a foundation of community health. The transportation network is intended to accommodate multiple transportation modes, but traditional roadway design inequitably favors vehicle throughput over non-motorized needs.

In 2019, 6,205 pedestrians were killed in traffic crashes in the United States. (USDOT National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2020) That is about one death every 85 minutes. In the same year, 846 bicyclists were killed in traffic crashes in the United States. (USDOT National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2020) Similar to national trends, the Nashville region is experiencing a troubling trend for non-motorized safety. Since 2015, pedestrian fatalities have almost doubled and while serious motorized injuries were almost cut in half, non-motorized serious injuries remained constant. These trends have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the Tennessee Department of Safety reveals that 2020 proved to be the worst year on record as pedestrian fatalities continue to rise even with less cars on the road. (Tennessee Highway Patrol n.d.) With the recent surge in active transportation activity in the region due to COVID-19 related behavior patterns, combined with limited funding available for bicycle and pedestrian improvements, it is imperative that a more systemic and focused approach be utilized to identify and prioritize solutions to improve safety for bicyclists and pedestrians.

29Planning for Healthy Cities

BACKGROUND

Crash data has traditionally been used to identify dangerous areas for bicyclists and pedestrians and to make investments in safety improvements through location specific crash analyses or hot-spot analyses. Yet, relying solely on prior crashes is limiting because it does not capture all areas that are unsafe for non-motorized users. Given that bicyclists and pedestrians often avoid areas without facilities or suitable conditions, there are unsafe locations not represented through a traditional crash analysis. To better understand the factors that result in nonmotorized crashes in the Nashville region, the Greater Nashville Regional Council (GNRC) developed a non-motorized risk index to systematically identify unsafe locations for bicyclists and pedestrians.

GNRC is the federally designated metropolitan planning organization (MPO) for the Nashville region and is responsible for investing in transportation improvements, preparing, and maintaining a long-range transportation plan, and planning and programming federal, state, and local funds for transportation projects and operations. Every five years GNRC updates the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) to account for shifts in national policy, local community issues and concerns, travel behaviors, advancements in technologies, and fluctuations in funding availability. (The Greater Nashville Regional Council 2021)

In 2019, GNRC began the process of updating the 2045 RTP and identified that prior RTPs had limited investment for bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. An increase in bicycle and pedestrian fatalities and population and shifts in lifestyle preferences for more walkable communities led to a

more comprehensive way to identify and prioritize areas for non-motorized safety improvements. The purpose was to develop a tool for prioritizing areas for investment in non-motorized safety across the region.

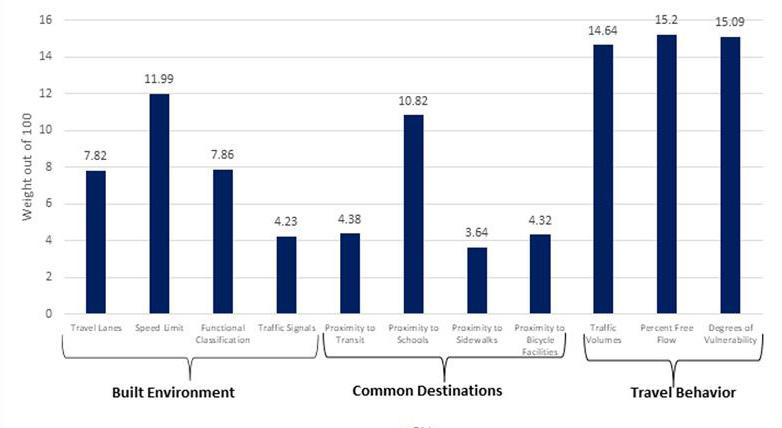

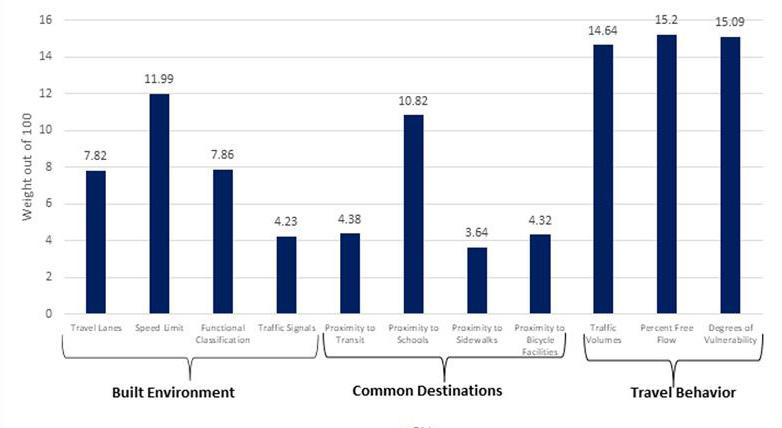

The non-motorized risk index aims to capture unsafe areas (beyond where crashes occur) at the system level based on an analysis of crash risk factors related to the built environment, common destinations, and travel behavior. The index identifies areas where the odds of non-motorized crashes occurring are disproportionately high. The index can help proactively identify locations with unsafe non-motorized conditions to better guide safety planning and improvements in the Nashville region through a rough system-level approach.

OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF NONMOTORIZED RISK INDEX

The index was developed through a set of five steps. Each step includes a corresponding question that is answered by the step below. While each step answers a prompt question, the index includes the following five steps to drill down to a system level to understand what increases crash risk across the entire region, not only in areas where crashes have occurred. Figure 1 details the index development process starting with the baseline: the regional hot-spot analysis.

HOT-SPOT ANALYSIS BASELINE