ME AND MY DRAM

Kiefer Sutherland opens up about his incredible whisky journey

ME AND MY DRAM

Kiefer Sutherland opens up about his incredible whisky journey

Welcome to Issue 19 of Cask & Still. It seems like yesterday that we started this crazy venture, but we’ve now been publishing for almost a decade, during which we’ve chronicled some seismic changes in the whisky industry.

In this issue, we continue to shine a light on the good, the bad and the ugly of the whisky world (only kidding, there’s no ugliness in this issue of C&S, although we do look at the economic pressures which many believe could lead to some consolidation and mergers).

As well as looking at the ramifications of the reopening of mothballed or defunct distilleries, we examine the explosion of interest in whisky making in traditional vodka nation Finland following the relaxation of regulations, and examine

the social, economic and cultural drivers behind our enjoyment of a dram. The how of whisky production is fascinating, but the why is even more multi-faceted.

As Christmas hoves into view and our readers look for recommendations, our experts once again offer their favourite drams for your delectation. But we also have some suggested cocktails from the Balmoral’s famous whisky bar, and columnist Brooke Magnanti’s ruminations on the appeal of mixing your drinks.

So here’s to a great Christmas, a Hogmanay to remember and a stellar 2025!

EDITOR Richard Bath

MARK LITTLER

A knowledgeable commentator, Mark writes about the wider cultural and social dimensions to enjoying a dram.

KIEFER SUTHERLAND

The legendary actor talks with us about his love affair with whisky and his new Canadian whisky.

NEWS

Remember, you heard it here first...

08 BAR SNAPS

Shinji’s in New York is whisky heaven for devotees of Japanese drams

12 BREAKING

32 A BLUFFER’S GUIDE TO BARLEY Everything you ever needed to know about barley

34 IS WHISKY REALLY JUST FOR DRINKING?

Asks Mark Littler, or is there more to it?

39 CONNOISSEURS’ SELECTION

@caskandstillmag

Editor: Richard Bath

Design: Grant Dickie

Production: Andrew Balahura, Megan Amato

Chief Sub-Editor: Rosie Morton

Staff Writers: Morag Bootland, Ellie Forbes

Contributing Editor: Blair Bowman

NUMBERS

your mates with all of the latest stats on Scotch whisky

46 AGEING GRACEFULLY?

Aged gins are on the rise but they are not to everyone’s taste

Contributors: Dr Brooke Magnanti, Mark Littler, Federica Stefani, Peter Ranscombe, Geraldine Coates, Harry Brennan, Sean Black

PUTTING UP THE ‘FOR SALE’ SIGN

52 VIVE LA DIFFÉRENCE

Email: editor@caskandstill magazine.com

ADVERTISING

Grant Philbin

be a big year for craft whisky distillery owners who are tempted by mergers and acquisitions?

How Châteauneufdu-Pape is following in the footsteps of Scotland’s whisky tourism industry

Tel: 0131 551 7915

PUBLISHING

MIX

fuel your winter season from SCOTCH Whisky

55 OVER A BARREL The resurgence of IPAs and 80’ Shilling ales

Publisher: Alister Bennett, The North Quarter, 496 Ferry Road, Edinburgh EH5 2DL. Tel: 0131 551 1000

56 SPIRIT LEVEL

OVERSEAS WHISKY

tradition in country where it was banned in the 1900s

Dr Magnanti strays from her norm and experiments with classic cocktails

66 DRINKING WHISKY IN THE NETHERLANDS

Harry Brennan on the country’s thriving whisky scene

Published by Wyvex Media Ltd.

While Cask & Still is prepared to consider unsolicited articles, transparencies and artwork, it only accepts such material on the strict understanding that it incurs no liability for its safe custody or return. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine do not necessarily reflect those of Wyvex Media Ltd.

Johnnie Walker Princes Street has welcomed more than a million visitors from 141 countries just three years since opening its doors. The venue leverages AI-powered personalisation technology to help guests discover their personal flavour profile, which is then used to tailor their experience on Johnnie Walker Princes Street’s signature ‘Journey of Flavour’. To date, the experience has collected the flavour profiles of around 100,000 guests. www.johnniewalker.com

The Distillers One of One Charity Auction will return at Hopetoun House next year. Since 2021, the auction has raised £4.3 million for the Youth Action Fund. The event, which sees collectors of rare whisky from around the world gather, has so far broken 37 auction records globally. www. distillersoneofone.com

Scottish actor Ewan McGregor has raised £135,000 for charity after auctioning 150 bottles of whisky from his own personal cask at Lochranza Distillery. The rare 26-year-old Arran single malt, matured in an ex-sherry hogshead cask, is one of the oldest whiskies ever produced by the distillery. McGregor first toasted the inaugural cask of the malt back in 1998, which was the first legal cask to be laid down on Arran for over 150 years. The distillery presented him with his own cask that day and it has matured in their warehouse until now. Money raised from the auction will go to Children’s Hospices Across Scotland (CHAS). www.chas.org.uk

Global online whisky community, The Whiskey Wash, is relaunching as a price comparison site for whisky. The new one-stop-shop is in response to the increasing consumer demand for premium and super premium whiskies, bringing approved global retailers, auctioneers and distributors together with whisky enthusiasts across the world. The global whisky market is worth $69.5bn. www.thewhiskeywash.com

54 YEAR OLD

42.9% ABV, RRP £22,000

This is one of the oldest Highland Park whiskies to come on the market. It has a deep, multi-faceted nose, a rich creamy finish and a hint of delicate spice.

12 YEAR OLD

57.2% ABV, RRP £65

First aged in ex-bourbon casks before re-ageing in French oak barrels that previously held Calvados and Pommeau, this dram has heathery and floral notes.

21 YEAR OLD

53.6% ABV, RRP £275. Distilled on the shorelines of Islay, the Pedro Ximénez casks lend this spirit rich, sweet notes, delivering bold flavours of creamy berries, roasted nuts, and a touch of sea spray.

49 YEAR OLD

51.4% ABV, RRP £35,000

Marking Gleneagles’ 100th anniversary, this exclusive collaboration with Glenfiddich celebrates luxury. The dram has rich notes of vanilla fudge, creamy toffee and oak and finishes with sweetness.

The Macallan has released a rare 84-year-old dram, the malt that marks the first from the brand’s new distillery,

Pop singer Beyoncé launched her own whisky after collaborating with a leading Scotch expert. The dram was created with whisky pioneer Dr Bill Lumsden who is renowned for his work on Glenmorangie and Ardbeg. The dram, SirDavis, was named after Beyoncé’s moonshiner greatgrandfather Davis Hogue. www.sirdavis.com/en-gb

The Isle of Harris Distillery has released the second permanent expression within The Hearach single malt range, The Hearach oloroso cask. The new expression is entirely matured in first-fill oloroso sherry butts, for a bold and deeply aromatic spirit. It features notes of orange peel, warming spices, fireside smoke and toasted hazelnuts that evoke a cosy winter evening. www.harrisdistillery.com

Welcome to New York’s largest selection of Japanese whisky. Developed by the team behind Noda, a Michelin-starred omakase restaurant, this 18-seat bar provides an intimate cocktail experience for high rollers in the Big Apple. It’s ultra-luxe. Think liquid nitrogen cocktails, moody designs and tableside nibbles of caviar and handrolls.

www.shinjisbar.com

Hollywood A-lister and founder of Redbank Canadian whisky, Kiefer Sutherland takes Cask & Still on a deep dive into his world of whisky

Do you remember the first time you ever drank whisky?

I was 15 years old and I’d been doing a play in Canada for three months. At 15, three months is an eternity and eventually one of the actors saw that I was lonely and said, ‘Get changed, we’re going to a bar.’ I don’t think I’ve ever changed as fast in my life! We walk in and the bar tender asks me what I want to drink. I looked up and saw a bottle of J&B and thought, ‘Oh good, my dad used to drink that, and my mom used to drink that, I’ll get one of those.’ I threw it back and three drinks later I thought, ‘wow, this stuff is really great’. But what I remember most is that I stopped feeling lonely.

Where’s your favourite place to have a dram?

I’ve always attributed having a drink with being with friends. I don’t drink at home and I don’t drink alone. It was always a social thing. The best example is that you can go to a bar with two friends and walk out with five, right?

Do you have a favourite whisky?

for a long time. People started saying, ‘my grandfather drinks that’. And I’d kick back and say, ‘I bet your grandfather is really cool!’

Did you ever share a dram after a long day’s filming?

No, mainly because there’s almost always another long day’s filming the next day. We made 216 hour-long episodes of 24. That takes time. It’s a decade’s worth of work at the pace of making over ten movies a year. You can’t get through that volume of work and be as crazy as some people think I am.

What made you decide to make Redbank whisky?

I didn’t really decide to found a whisky company. We are four friends and we wanted to do something fun. It started as a way we could hang out more.

‘What I remember most is that I stopped feeling lonely’

You could fill the Grand Canyon with what I don’t know about whisky. In fact, you could fill the Grand Canyon with what I don’t know about lots of things! But, in the United States, and this was always hard to find, there was a whisky called Uisge Baugh [Tullamore Dew Blended Irish whiskey]. It came in a little stone jug with a cork and the first time I found it I bought a bottle to share with a friend who was wrapping a film with me. We both tried it and were like, ‘Oh my God, did you feel that?’

Because you know if you were to pour out mercury and it beads as it starts to move? That’s what it was like. I felt it separate in my mouth. It was the smoothest thing I’d ever tasted.

And what about your regular tipple?

I drank Glenlivet or Glenfiddich because that’s what you’d find in bars. But I drank J&B

How much input did you have into Redbank?

I wanted to make something uniquely Canadian, but I’m not a huge fan of Canadian whisky. I’d never understood why Canadian whisky isn’t redirecting itself towards Scotch. So we had a conversation with Michel Marcil, who would become our distiller, and he said that most Canadian whiskies have a high rye profile and a low wheat profile, so we could just switch them. We had a long discussion about what we liked and he went off to make the liquid. We had a blind tasting and all of us went, ‘that one!’. Well, the accountant picked something else and he’s never been invited back to a tasting since.

Do you enjoy a whisky cocktail?

I don’t drink cocktails, but we had an event at Redbank where lots of bartenders made these amazing cocktails. The finish, those vanilla and caramel flavours, still came through in the cocktails. You could tell it was a Redbank Paper Plane, or a Redbank Whisky Sour.

Written by Sean Black

very industry will work through boom-and-bust cycles, it is just part of business. Scottish whisky is no different and whilst we are currently amid a boom, it has not always been like this. Positive years bring about high sales, distillery openings, scores of jobs and plenty of drinking options. Lean years are sadly different, and it tends to lead in one ultimate direction – the closure of distilleries.

In the middle of the 1970s, Scotland was producing a vast amount of whisky, mostly for a thriving blend market as single malts were only a small part of the scene. However, whisky is a cyclical industry and circumstances changed; it soon became apparent that there was too much liquid out there, but not the demand. One key player, Distillers Company Limited (DCL), was significantly impacted, eventually deciding to close 11 malt distilleries and a further grain

The peaks and troughs of the Scottish whisky industry are well documented, but now we can raise a glass to the rebirth of lost distilleries

distillery in 1983, with additional closures in 1985 and sporadic shutdowns in other years. Further companies followed suit and Scotland’s whisky landscape changed dramatically. Those distilleries selected for closure were either too expensive to upkeep at their current standard, required substantial investment

‘Collectors are prepared to break the bank to get whisky from these silent distilleries’

to run e ciently, or were deemed to be so unremarkable that their spirit could be easily replaced. And so those unfortunate chosen distilleries were mothballed or demolished, and whatever stocks remained were tucked away for another day. As appetite for single malts grew in the late nineties, fans, bottlers

and collectors got stuck into these underappreciated, well-aged stocks. Helped in large part by special releases and word of mouth, some of these ‘silent’ or ‘lost’ distilleries became highly regarded and sought after. When used in a blend, they had no chance to shine. But as a matured single malt, they took the spotlight.

And so, the legends of Brora, Port Ellen, Rosebank and Dallas Dhu grew. All four were shut at some point by DCL (who eventually became Diageo) but were spared the total demolition fate that befell others.

Casks and bottles from these fabled icons became increasingly valuable and expensive, and gained a magical place in the eyes of enthusiasts, partly because they were deemed to be spirit of the upmost quality, but also because of their rarity. The liquid inside each cask or bottle was a fraction of all that remained. Once it was gone, it was gone. There would be no more.

With all this appeal, collectors are prepared to break the bank to get whisky from these

silent distilleries. In 2014, Diageo released their most expensive retail bottle of whisky at the time to the duty-free market, a 1972 40-year-old Brora, retail price £7,000. So highly desired was this whisky that it fetched even more at auction; a bottle was sold at Sotheby’s for £45,000 in 2019.

Riding the wave of the current boom has changed the fortunes of these silent distilleries. The interest, and price, is high, yet the availability does not exist. What is the solution? How about reopening and producing more?

Diageo took that step by announcing in 2017 that it would reopen both Brora and Port Ellen. Brora was up first, and restoration work started in , with the first casks filled in . The team behind the reawakening were so keen to keep the esteemed previous Brora style that much of the equipment is exact an copy of what was there in the days before it was shuttered. Next up was Port Ellen, although that required more work as little remained after years of inattention and pillaging. But it was rebuilt and reopened in 2024, even with a replica pair of

stills (known as the phoenix stills) created to mimic those from a bygone era, as well as an extravagant visitor centre.

They are not alone. Ian McLeod Distillers (owners of Glengoyne and Tamdhu) acquired osebank distillery in alkirk and after significant investment and overhaul, including replacing the stills which were stolen during a break-in around Christmas , osebank produced its first spirit in 2023 and opened to the public in the summer of 2024.

Later that summer, it was announced that Dallas Dhu in Speyside will reopen under the vision of Aceo, the spirits company who run Murray McDavid. After years of operating as a museum by Historic Environment Scotland, the hope is to create a fully functioning distillery again, blending original and historic equipment with more modern and sustainable practices. The plans for Dallas Dhu also include dining options and a state-of-the-art visitor centre, outlining the whisky industry and the Speyside region.

But might these reopenings impact the very

‘Riding the wave of the current boom has changed the fortunes of silent distilleries’

essence of what has made these distilleries so coveted? Part of the appeal has been that the stocks are finite, so replenishing appears contradictory. And what if the latest whisky cannot live up to the quite considerable hype? owever, more likely is that the old stocks will continue to be highly prized, and the new spirit will create its own story, blending together the distinct histories of the distillery.

Other distilleries that have gone silent have re entered production and become staples of the whisky market. Tamnavulin, Benromach and nockdhu through their anCnoc range all had years of inactivity and are now widely available and well regarded. In due course, the likes of Brora and osebank may not only be thought of as once lost distilleries, but as contemporary creators of some of the finest single malts the country has to offer.

It remains to be seen what impact bringing legendary silent distilleries back into production will have. Years will pass before any are producing new whisky for us to sample, debate and appreciate. Will these new visions capture the flavours and profiles that led to these distilleries becoming so sought after? Will they still enthral and captivate enthusiasts? Will they create a new tale for each distillery? Only time will tell, but you’d be hard pushed to find anyone out there not curious to see how the stories continue.

Written by Gemma Foster

If you’re a fan of whisky and golf then Room 116 at Rusacks hotel in St Andrews might just be your idea of Shangri-la

Golf, like whisky, has a rich and storied past in Scotland. We all know that St Andrews is the home of golf, but now it’s also the home of an exclusive new whisky lounge at Rusacks St Andrews Hotel.

Room 116 was created by Marine & Lawn Hotels and Resorts in partnership with The Glendronach to showcase its rare collections. One of Scotland’s oldest licensed distilleries, The Glendronach has been crafting sherried single malts in the Highlands for almost 200 years.

Boasting what might very well be ‘the best view in golf’, overlooking the hallowed greens of The Old Course, Room 116 was once a guest suite in the hotel. It has now been transformed into a luxurious members’ club-style space that’s perfect for whisky tastings, with a vintage vibe that’s befitting of this glorious old building that dates back to the 1800s.

With a little bit of luck and a prayer to the weather gods you’ll have the opportunity to sip a dram on the private terrace with panoramic views over the fairway. But there’s much to enjoy if conditions are inclement too. Room 116 is a

haven of beautifully crafted cabinetry housing a unique whisky collection including archive casks, a bespoke bar, comfy leather seating and a gallery of portraits that is a real who’s who of golf.

Personalised tours and tastings to suit all golf and whisky lovers can be booked at Room 116. Try the Home of Golf two-hour tour which includes storytelling, four Glendronach malts, a mezze board and golf amenities for 5-20 guests (£195 per person), or simply hire Room 116 for private use for 8-20 guests (£140 per person for two hours) and enjoy having this luxurious space all to yourself.

Room 116 also features in the new Marine & Lawn Grand Tour, a package including golf courses in Scotland and Northern Ireland, as well as luxury accommodation, transfers, bespoke dining, concierge service and rare golf experiences like lessons with professionals, personal styling and private museum tours.

For more information visit www. marineandlawn.com/rusacksstandrews

Just Whisky Auctions is revolutionising the world of whisky collecting. This online auction platform offers a seamless experience for sellers and buyers with its impressive features. Firstly, sellers can benefit from 0% commission, allowing them to maximise their profits. Additionally, the platform ensures fast payments, guaranteeing a hassle-free transaction process. For buyers, the appeal lies in the convenience of worldwide shipping, enabling whisky enthusiasts from all corners of the globe to participate. Moreover, Just Whisky Auctions conducts monthly auctions, providing a consistent stream of exciting opportunities to expand one’s whisky collection.

Telephone Number: 01383 745665

Website: www.just-whisky.co.uk

Hidden in a basement, three minutes from Queen Street station in Glasgow, the Good Spirits Co. is crammed with bottles from every corner of the world. Alongside hundreds of malt whiskies – including some shop-exclusive single casks – there’s also a huge selection of rum, brandy, gin, tequila and bourbon, plus just about every possible ingredient you’d need for a cocktail.

Books and bottled cocktails make great festive gifts, there’s a humidor with a wide selection of hand-rolled Cuban cigars, and the neighbouring Wine & Beer branch offers fine wine, champagne, port, sherry, and a range of craft and traditional beers and ciders.

Telephone Number: 0141 258 8427

Website: www.thegoodspiritsco.com 23 Bath Street, G2 1HW 105 West Nile St, G1 2SD 21 Clarence Drive, G12 9QN

Impress your friends with these facts and figures

Around 90% of barley required for the industry is sourced in Scotland.

41,000 90%

In 2023 more than 41,000 people were employed in the Scotch whisky industry in Scotland.

The United States remains the largest global market for Scotch whisky by value at £421.4m, down 3.5%.

In 2023 Scotch whisky accounted for 74% of Scottish food and drink exports and 22% of all UK food and drink exports.

Exports of Scotch whisky fell by 18% £2.1BILLION

Exports of Scotch whisky fell by 18% to a value of £2.1bn.

India is the largest market by volume, with growth of 17.3% in the first half of 2024.

£298,000,000

The 10.1% increase to spirits duty in August 2023 resulted in a £298m reduction in revenue.*

Source: Scotch Whisky Association. All figures relate to the first half of 2024, compared with the same period in 2023, unless otherwise stated. *Between August 2023 and July 2024, compared to the same period the previous year, according to HMRC figures.

Could 2025 be the year that we start to see consolidation among Scotland’s craft whisky distilleries, with owners feeling tempted by mergers and acquisitions?

Written by Peter Ranscombe

Whisper it, but we could be on the verge of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) among Scotland’s craft distilleries. Speculation and hushed conversations are slowly solidifying into formal negotiations.

are uietly on the market. I would expect to see some of these smaller distilleries go through changes of ownership over the next six to 12 months.’

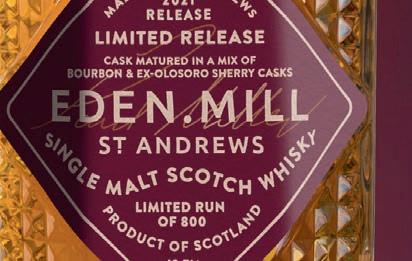

A small number of deals have already been done – private equity firm Inverleith bought ife based distiller and brewer Eden Mill in 2022 and, south of the Border, English sparkling winemaker Nyetimber acquired The Lakes Distillery in the summer of 2024. Experts say more deals are in the pipeline.

‘The long and the short of it is that there is talk of M&A among the smaller distilleries,’ confirms Brian Moore, a partner at Dentons, the world’s biggest law firm. ‘I’m aware of a number of projects that are going through sale processes.

‘There are also some distillery assets that may not be in a formal M&A process at the moment but

A number of factors are at play. The craft distillery boom began in earnest following a change in the regulations in 2009, which legalised stills holding fewer than 1,800 litres, and allowed British craft distillers to follow in the footsteps of their American cousins.

Now, the number of Scotch whisky distilleries has soared to 151. Some of the initial investors will have held their shares for more than a decade and will be starting to think about selling them to get a return on their cash.

‘By necessity, investors in whisky tend to be patient capital,’ explains Moore, highlighting the long time it takes to age Scotch. ‘But there are a number of factors that can drive when the time is right for people to put assets up for sale.

‘Outside events can sometimes drive sales. or example, if something has happened elsewhere in an

investor’s portfolio, which forces them to sell.

‘The other factor that’s relevant for these smaller distilleries is the nature of their shareholder base. Some of these investors will have now been through the excitement of building a distillery and have reached the point that they want to make some money from their

Duncan McFadzean, managing director at investment bank Noble & Co, questions whether the typical five to eight year investment timescale of private equity or venture capital is relevant to craft distilleries because he thinks a lot of the investors are individuals, family o ces or trade investors. Instead, he thinks other factors are at play.

o

‘If someone comes knocking on your door, are you more likely to consider it than you were five years ago? Yes.’

‘I would expect to see smaller distilleries go through changes of ownership’ investment.’

‘There is some M&A, and there’s quite a lot of activity behind the scenes,’ he reveals. ‘We’re in a part of the economic cycle where M&A would typically be more prevalent – things get tougher, cashflow gets tighter, banks are not as keen to provide funding as they were a few years ago, the cost of that funding has gone up, and it’s tougher to generate revenues.

get

door, are you more likely to consider it near Greenock, highlights the fact that distilleries with their initial investments, meet rising costs. That then leaves less other projects.

Roland Grain, the Austrian investor who’s building Ardgowan distillery near Greenock, highlights the fact that often shareholders don’t simply support distilleries with their initial investments, but also with ongoing finance to help meet rising costs. That then leaves less cash for those financiers to invest in other projects.

‘It’s the combination of lower interest to support the distillery from existing shareholders over the years, higher than planned production costs, and a really weak market in the so called affordable premium segment” where most of the new distilleries try to be,’ he says. ‘People sometimes believe that once you have the money to build a distillery then everything is fine and will work.

shareholders over the years, higher than affordable once the money to build a distillery then production as equity and even more

seen by many investors in young whisky

‘You need a minimum of the same amount again in the first ten years of production as equity and even more as additional debt. This reality is now seen by many investors in young whisky

projects, and this need for money is exhausting the investor base so that there is less and less left for new projects.’

So – who are the buyers going to be for Scotland’s craft distilleries? McFadzean from Noble & Co, who also writes the weekly Commercial Spirits Intelligence email newsletter with Martin Purvis, points to investors as well as other distillers.

‘What I am seeing is there’s probably more private equity interest coming into this space than there has been in a good number of years, and part of that is that craft boom,’ he explains. ‘A lot of those businesses are several years on, they’re generating revenue, some of them are profitable, so it starts to meet the criteria of a

financial investor, where it’s really about scaling it, rather than building a distillery and getting your first product into market.

‘With the trade, things are tougher out there, so if there’s an opportunity to buy growth then they’re interested in that. People like Pernod Ricard and Diageo have used this approach to supplement their own new product development.’

While bidders might be circling Scotch makers behind the scenes, distillery design consultant Gareth Roberts questioned why a craft player would need to sell in the first place. ‘Distilling can be very robust once you have everything in place to make spirit,’ he says, pointing to demand for spirit from Indian blenders.

‘For example, you can sell shifts at cost-plus, so you’re always going to cover your expenses and keep the lights on and pay the staff. If you have a fully functioning distillery, there should be no reason why you should go out of business.’

SCOTCH Bar at Edinburgh’s Balmoral Hotel is a whisky lover’s paradise whose new book provides a wealth of cocktail inspiration...

SERVE IN: Rocks glass or short tumbler

GARNISH: Strip of lime zest

20g (¾ oz) desiccated coconut (or unsweetened shredded coconut)

45ml (1½fl oz) Glencadam 15YO

35ml (1¼fl oz) Italian vermouth

20ml (3/5fl oz) Campari

Strip of lime zest, to garnish

METHOD: Preheat the oven to 180ºC fan (400ºF), gas mark 6. Spread the desiccated coconut onto a baking tray and bake until the coconut just colours. Be careful not to burn the coconut, or this will make the cocktail bitter. Once cooled, transfer to a container, add the whisky and allow to infuse for an hour. Strain through a coffee filter twice and chill in the fridge. To make the cocktail, pour all ingredients into a mixing glass with large ice cubes and stir until the liquid is ice cold. Strain into a rocks glass or short tumbler filled with ice cubes. Twist the lime zest over the glass so that the essential oils spray into the liquid, and drop it into the drink.

SERVE IN: Rocks glass or short tumbler

GARNISH: Cherries and lavender

50ml (1¾fl oz) Glenfiddich 15YO

30ml (1fl oz) cherry cordial (see below or use a shop-bought alternative)

25ml (4/5fl oz) egg white or aquafaba

Bottled cherries

A crumbled, dried lavender sprig, to garnish

METHOD: Put all the main ingredients in a cocktail shaker and shake to mix everything together. Add a handful of ice cubes and shake until the cocktail is well chilled and diluted. Double strain into a rocks glass or short tumbler filled with ice cubes.

Cherry Cordial

This cordial is made with cherry syrup from good-quality canned or bottled cherries. First, strain the cherries and collect the syrup. Weigh the syrup and add 4 per cent of its weight of malic acid (lemon juice can be used as an alternative). Store in a sterilised bottle – it should last for around 3 weeks in the fridge.

SERVE IN: Highball glass

GARNISH: Sprig of purple shiso

35ml (1¼fl oz) The Macallan 12YO Double Cask

20ml (3/5fl oz) Tarragon Green Tea Cordial (see below or use 20ml/3/5fl oz lemon ice tea and 4 drops anise spirit)

2 drops Ms Better’s Mt. Fuji Bitters (or any other fruity bitters)

150ml (5fl oz) peach soda

Purple shiso sprig, to garnish (optional)

METHOD: Put the whisky in a highball glass with the Tarragon Green Tea Cordial and bitters. Fill the glass with ice cubes, then top up with the peach soda. Garnish with purple shiso.

Tarragon Green Tea Cordial

SERVE IN: Stemmed beer glass

GARNISH: Red chilli and orange zest

50ml (1¾fl oz) Johnnie Walker Black Label

20ml (3/5fl oz) ginger liqueur (The King’s Ginger is a good option)

Brew 500ml green tea, ideally at 80ºC, infused to double the strength you would drink it at. Remove teabags, add 50g fresh tarragon, muddle lightly and cool. Strain to remove the tarragon and add 5g malic acid (or lemon juice).

Shake well, then add 250ml agave nectar. Store in sterile bottle – should last 1 month in fridge.

30ml (1fl oz) Honey Cordial (see below)

2 dashes orange bitters

75ml (2½fl oz) spicy ginger beer

Long, thin slice of red chilli and strip of orange zest, to garnish

Spritz of Talisker 10YO (optional)

METHOD: Combine the whisky, ginger liqueur and Honey Cordial in a shaker, add ice cubes and shake vigorously to chill. Once cold, strain into a stemmed beer glass filled with large ice cubes. Add orange bitters and top up with ginger beer. Garnish with chilli and orange zest. Spray the Talisker over the top of the glass.

Honey Cordial

Mix 2 parts honey with 1 part boiling water. Add 1 star anise and orange zest. Infuse. Store in sterile bottle – should last 3 weeks in fridge.

SCOTCH: The Balmoral Guide to Scottish Whisky by Cameron Ewan & Moa Reynolds, is out now. Imprint, Mitchell Beazley. RRP £22. Based in Edinburgh’s famed The Balmoral Hotel, SCOTCH Whisky Bar is a now veritable Mecca for those who enjoy the water of life. www.roccofortehotels.com

In vodka-obsessed Finland, whisky was banned until 1904, but liberalisation in 1995 has led to some stunning local drams

Written by Federica Stefani

s several countries ride the whisky boom, inland finds itself relatively new to the world of whisky distillation.

Unlike nations with deeprooted traditions in whisky production, Finland is primarily known for its vodka. However, in just a few years, Finnish whisky makers have begun to make significant waves in the global market.

A NEW WHISKY FRONTIER

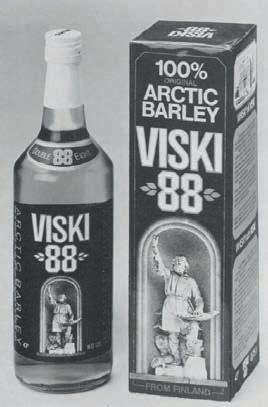

Finland arrived rather late to the European whisky party. Following the Russian occupation in 1808, the importation of whisky was forbidden until 1904. Even after the ban was lifted, the local preference leaned heavily toward vodka and imported cognac, leaving little room for whisky in Finnish culture.

The country regained its independence in 1917, shortly

after the Russian Revolution, but entered a period of prohibition known as kieltolaki, lasting from 1919 to 1932.

When this prohibition ended, alcohol production remained under strict state control. That same year government-owned alcohol retailer, Oy Alkoholiliike Ab – now known as Alko – was founded. While a few whisky brands made their way into state-owned shops, Alko was also involved in producing whisky.

It wasn’t until Finland joined the European Union in 1995 that private distilling became legal. This marked a turning point, allowing a broader range of brands to emerge and be imported. However, the sale of spirits, wine and beer above 8.5% ABV still remains under Alko’s monopoly today.

The popularity of whisky started growing and that’s, literally, when things started brewing.

In 2001, Mika Heikkinen, owner of Panimoravintola Beer Hunter’s in Pori, distilled the first innish single malt whisky, Old Buck. Over the years eikkinen maintained production of very small batches, with new releases appearing intermittently.

In , another brewery and restaurant, Teerenpeli, began distilling in its garage based distillery in ahti.

‘ ahti is near one of inland’s largest groundwater reserves, now a CO Global Geopark. We have access to pure water and a lot of of barley is grown in the area,’ explained eera astinen, sales and marketing manager for Teerenpeli.

fter starting to make beer, the owner thought that whisky would be a natural progression. Teerenpeli primarily produces single malt whiskies and has expanded its distillery since, repurposing the original space to make gin. The company’s network of restaurants across inland has been crucial for its success, particularly given the country’s stringent laws on alcohol sales and advertising.

‘In inland, we cannot sell or advertise alcohol

outside licensed premises, so our restaurants serve as a great outlet,’ eera continued. ‘We cannot mention alcohol on social media at all, nor can we post a photo of a whisky bottle. This makes you uite creative Winning awards has significantly helped us spread the word about our products without it being perceived as a direct attempt to sell alcohol.’

trict controls by the state over alcohol production and marketing meant that no new distilleries were able to be established for a while.

SAUNAS, RYE, AND MONKS

s the global whisky boom gained momentum, innish whisky enthusiasts began forming clubs.

In , the largest whisky society in inland, The ellowship of Whisky iskin Yst vien eura , was founded and now boasts more than , members. It was at this time that five friends gathered in a sauna to taste rye whisky and hatched an idea that would lead to the founding of yr istillery in .

‘We aimed to make whisky that was characteristically innish,’ said alle alkonen, master distiller at yr . ‘ ye is a staple in our diet, and we wanted to use it exclusively in our whisky.’

Located in a repurposed dairy in Isokyrö, Kyrö employs traditional cold smoking methods, Finnish peat, and has even released the first whisky finished in a sauna.

‘ ince we don’t have a long tradition of whisky distillation, we had the freedom to create a innish whisky the way we envisioned it,’ alle noted. owever, the journey for new distilleries like yr was not without its challenges. The strict control on advertising limited marketing options. To reach consumers, they set up a pop up restaurant in elsinki.

‘Initially, the legislation was so restrictive that we couldn’t even mention on our website that we were producing rye whisky,’ alle said. dditionally, small distilleries cannot sell their products directly, as everything must go through lko shops. ‘ ortunately, things have improved over time, making it easier for us,’ alle added. ‘The growing craft brewery culture in inland has encouraged other craft producers to start their own businesses.’ yr ’s opening was followed in the same year by The elsinki istilling Company, founded by childhood friends and whisky enthusiasts ikko ykk nen and ai ilpinen. ‘ ot having a whisky making tradition in inland presents challenges,’ ikko explained. ‘You lack someone to ask for guidance, but you also have the freedom to innovate.’

The distillery mainly focuses on rye whisky but also experiments with other grains, producing single malts and bourbon style whisky using innish corn. They work closely with the niversity of elsinki and source barley from the local area. The distillery benefitted from the gin boom, as interest in their products grew during that period. ‘There was a genuine curiosity about innish alcohol, which helped us a lot,’ ai said.

The climate also plays a crucial role in shaping the character of innish whiskies. The short summers with long daylight hours mean local grains will have specific properties influencing the spirit’s flavour, while freezing winter temperatures can impact maturation.

‘Severe temperature fluctuations slow down maturation and can create micro cracks in the casks, causing small leaks,’ ai explained. ‘ o, you need to mature whisky in a controlled environment to avoid that.’ eera from Teerenpeli refers to the whisky lost in the leaks as the ‘ evil’s hare’.

In , another significant player, alamo onastery istillery, was established, producing a variety of spirits from an Orthodox monastery in astern inland. In , gr s istillery opened in iskars, focusing on botanical spirits with the release of a limited batch of whisky

matured in or Oloroso casks, with more to come.

‘We’ve historically had a lavic drinking culture, with vodka and neutral grain spirits dominating,’ said Jarkko ikkanen, brand ambassador for drington and Beam untory, known as r. Whisky of inland. ‘ ortunately, things are changing.’

e noted that people are now drinking less but opting for higher uality options.

‘Whisky is appealing to younger consumers because it’s not just about getting drunk it’s about exploring flavours and stories.’

While cotch whisky

remains popular, Jarkko emphasised that the innish market still leans toward blended whiskies. owever, interest in and Irish whiskies has surged, partly due to the growing cocktail culture. innish consumers tend to enjoy smoky whiskies, and although local distillers are still small players on the global stage, interest in their products is rising.

‘We have a vibrant whisky scene in elsinki,’ Jarkko added, highlighting bars like ub udvig, Barley & Bait and ikkulintu uttopuisto. Other cities, including Turku, Tampere, Oulu and uopio, also boast specialist whisky bars.

s new producers like oto pirits in emp l and agu istillery in the agu archipelago emerge, the future looks bright for innish whisky.

o, as they say, ippis

Written by: Federica Stefani

n the previous issue of Cask & Still, we looked into various aspects of malt production for whisky: what characteristics farmers and maltsters seek in the barley, the varieties used in the industry now and in the past as well as harvesting seasons.

For this edition of our Bluffer’s Guide, we delve deeper into the impact of climate change on malting barley production, where it is grown and how the industry is seeking more sustainable ways forward with the help of Rebecca Gee (grain procurement manager) and Colin Johnston (sales and marketing director) from malting company Crisp Malt.

Across Scotch whisky – and the wider distilling world – there is increasing interest in terroir and how locally-grown barley and other elements of a specific place can affect spirits’ flavours.

However, the vast majority of barley is still grown in key areas across the UK – mainly on the east coast of the country – where the type of soil and weather is ideal for this crop. ‘If you look at a map of the barley-growing areas, and where all the maltings are located, they’re very similar in climate and soil,’ says Rebecca.

‘Getting the rain at the right time and getting

Growing malting barley can be an exacting process for farmers, but their input is absolutely key to effective whisky production

sun at the right time is important, as is having a very light, sandy soil, which is very good for malting barley. It doesn’t hold the water too much, but it allows the roots to grow.

‘We’re looking for low protein levels in barley and that light, sandy soil doesn’t hold on to the protein. It is different from the soil required for growing wheat, which is usually grown on heavy land as it normally goes to the baking and bread industry, where a high level of protein is welcome.’

Aberdeenshire and Moray (where malting facilities such as Crisp Malt’s new establishment in Portgordon, Boortmalt’s maltings in Buckie and Diageo’s maltings at Roseisle and Burghead) have a very high concentration of barley growers. In England, Norfolk and Yorkshire are also important areas for this crop.

The changing weather and climate heavily impacts crops like barley, which is now going into the ground later than usual.

‘Usually, spring barley is planted in April,’ says Rebecca, ‘but because it has been so wet, farmers struggled to get onto the fields to plant the barley in the usual season. So, we had late crops going into the ground this year, and we

are seeing this more and more.

‘Generally we’ll see quite a steady annual rainfall, but recetly we’re getting long stretches of rain and then long stretches of drought.’

Colin added: ‘Climate volatility is increasing so we need to be prepared for what Mother Nature throws at us in the future.’

To answer these new challenges, companies and researchers are exploring new varieties of barley, with Crisp Malt embarking on a new PhD programme looking into climateresistant varieties of barley.

Companies are now focusing on resilience, while looking at how they can reduce emissions and pollution. Mapping the carbon footprint of their farmers is a useful first step.

‘One of the most important steps is to benchmark where we are at the moment, then share that information among the farmers we work with,’ says Rebecca. ‘So, if one farm has a particularly low carbon footprint, those practices can be shared across the group.’

comes from the farming and agricultural side of the business.

‘It’s not a farm issue,’ she stresses. ‘It’s an industry issue. We need to work really closely with the growers to come up with solutions for everybody.’

The rest of the carbon footprint, says Colin, comes from the energy used in the malting process, when the barley is dried after harvest, and the energy used during germination to wet and dry the barley, including the last step in the kiln.

The solution, he says, is to make wider use of renewables

and technologies to make barley growing for malting more sustainable and profitable.

‘Investing in projects that can look at these climate resilient varieties is really important because it looks after the risk for us, but also the risk to the farmers,’ says Rebecca. ‘We need these farmers to continue to want to grow barley for us.’

Malting barley is not an easy crop to grow. It has to meet tight specifications, requiring extra effort from farmers and a loss in revenue if they fail to meet those specifications and have to

and electricity in the processes (plus newer technologies for kilning). Here, biogas and hydrogen may provide solutions.

‘Emerging technologies will help, but what’s required is investment in the sector to achieve that journey to net zero. But this will have to be a gradual transformation, balancing food security and supply and demand with sustainability. It requires all parts of the supply chain to work together on solutions.’

In malting, the majority of the

carbon footprint (around 60%)

The key is now to work with farmers to introduce practices

sell the barley for cattle feed. ‘Consumers don’t appreciate that farmers’ choices of what they grow depend on what makes them a living and what’s resilient,’ says Colin.

Farmers also have new options available, such as government schemes encouraging them to put land into fallow use for a period of time, which might be more profitable than growing crops, but which might make land unavailable for several years.

‘I think it’s really important that we’re all aware of the challenges that the farmers are facing,’ Colin concluded.

Sharing a dram with friends is a beautiful thing, but there are also wider cultural, social and economic meanings behind how we enjoy our national drink

s whisky just a drink, or does it play a larger role in society? To me, whisky has evolved and viewing it purely as a drink misses the complexity of its influence across different spheres. To truly understand its significance we need to delve into the deeper cultural, social and economic meanings it holds.

If we reduce whisky to simply a drink, then you can argue that its value should lie solely in

Written by Mark Littler

its consumption. Because all whisky is made using the same three ingredients then it should all cost the same and we should all like each whisky equally. Of course, that is a hugely simplistic view.

The consumption perspective aligns with Marxist ideas about ‘use value,’ which suggest that objects exist primarily to fulfil their functional purpose. A chair is for sitting, food is for sustenance, a watch for telling time –and each of those things should have a value based on the importance of that use and the

di culty cost of making it. Which of course, is not how society actually works.

Just as art becomes worth more than the sum of its paint and canvas, all consumable goods carry layers of meaning and significance far beyond their basic use. rom the brands of food you select to the car you drive and the whisky you drink, all can be appreciated aesthetically, culturally, and even financially, without ever being used or consumed.

or many enthusiasts, whisky is meant to be enjoyed in a glass. or whisky purists, an unopened bottle holds little value because it hasn’t fulfilled its ultimate purpose. It must be tasted experienced to be truly appreciated. It is this in turn that assigns value.

This gives rise to an inherent contradiction. ow can you define the value of a closed bottle before tasting it? nd in turn, each bottle that is opened reduces availability, which has the knock on impact of increasing price. ven without collectors, drinkers are driving up demand and, by extension, price for their favourite whiskies, just by drinking them.

The tension between consumption and preservation raises an interesting psychological dilemma. any whisky drinkers are also collectors who ac uire bottles not just to drink now but to save for special occasions, or sometimes just to admire, discuss, and for some, if the price is right, to even sell at a later date. or these individuals, the value lies both in the act of drinking and in ownership itself. The unopened bottle becomes a symbol of personal accomplishment, a token of one’s knowledge and discernment in the whisky world. It’s not just a drink anymore it’s an asset, a conversation piece, or even a legacy to pass down to future generations.

Imagine presenting a closed bottle of a rare whisky say, a Brora are alts to the average person. They might not grasp its significance.

But to a whisky enthusiast, that bottle speaks volumes without a single drop being tasted its prestige and rarity can be ‘read’ like a book, understood through the language of signs uni ue to the whisky world. o owning and displaying a rare piece, like the Brora mentioned above, becomes an unspoken statement about the owner.

If whisky were purely for drinking, why would anyone place such importance on the unopened bottle? The value here is symbolic, tied to knowledge, reputation, and cultural understanding just as one might appreciate a piece of art without needing to physically interact with it.

This leads us to a key comparison whisky and art. When you stand in front of, say, a Caravaggio, what do you see? o you simply see a painting on a wall? Or do you recognise it as a Caravaggio, appreciating the master’s signature style? erhaps, with even deeper understanding, you notice the subtle misalignment of perspective, revealing insights from avid ockney’s Secret Knowledge about the use of optics in art.

ach level of appreciation re uires increasing cultural and intellectual capital. The same applies to whisky. To the uninitiated, it might just be another bottle, but to those with knowledge and experience, it’s a complex

creation that tells a story.

Appreciation of both whisky and art demand what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu termed ‘cultural capital’ – the education, knowledge, and understanding needed to fully appreciate them. Because not all whisky is the same in terms

of history, quality and value it has evolved to be more like art; it requires an investment in understanding its craft, history, and significance. In this way, whisky is not merely a consumable but a marker of cultural, social and increasingly economic capital.

One example of whisky as cultural capital is The Macallan’s Fine & Rare collection. Each bottle in the series not only represents a remarkable whisky but also serves as a piece of history, crafted to evoke specific moments in time. The value in this series goes beyond the liquid – it includes its packaging, the story attached to the vintage, and the prestige of owning a bottle from such an exclusive series.

The packaging on this series is understated classic Macallan, which means to the casual observer a collection of Fine & Rare may just look like a few unremarkable bottles. However to other whisky connoisseurs a collection of Macallan Fine & Rare makes a significant statement of knowledge and wealth.

Beyond the individual collector, whisky experiences – such as tours at storied distilleries or exclusive tasting events – also contribute to its cultural capital. A visit to a distillery like Glenfiddich or Lagavulin is not just about tasting whisky; it’s about engaging with the history, craftsmanship, and heritage that the distillery represents. For many, these experiences add a personal connection and elevate their understanding of the spirit far beyond a simple tasting session. It’s not just about drinking whisky – it’s about becoming part of its story.

oreover, the influence of social capital can be seen in how whisky enthusiasts form exclusive networks or clubs around shared appreciation. These gatherings, whether formal whisky societies or informal tasting groups, create a sense of community and offer opportunities for statusbuilding within certain social circles. Possessing rare bottles or deep knowledge about the whisky world becomes a currency of its own, affording members access to otherwise exclusive events, tastings, or even business opportunities tied to the whisky industry.

Whisky, once primarily consumed, is now seen as a viable financial instrument, traded at auctions or held in collections for long-term

appreciation. Brands like Macallan have worked for the last 50 years to establish themselves as a luxury product. There has been a knock on impact of the value of those whiskies on the primary and secondary market. In recent years rare bottles of whisky have not only held their value but often appreciated significantly. or example, bottles from iconic distilleries like Port Ellen or Brora, both of which had ceased production for decades, have sky-rocketed in value as they became symbols of scarcity, heritage and quality.

This has given rise to whisky as an investment, and so people who have no interest in whisky as a drink have also become involved in the market. This gives rise to tensions within the different

are actively shaping this narrative. By creating intricate packaging, marketing whisky as a luxury good, and attaching significant price tags to their rarest expressions, the producers are also elevating whisky into something more than just a drink.

Producers are, in many ways, the driving force behind its transformation from a consumable into a status symbol, a collector’s item, and an object of cultural desire. Therefore, any critique of whisky’s broader societal role should consider the role of the producers. It is they who lay the foundations to craft the narrative that whisky is more than a liquid, embedding it with meaning and value beyond consumption. If whisky has become a symbol of economic or social capital,

‘Whisky is now seen as a viable financial instrument, traded at auctions or held in collections’

groups, with drinkers blaming investors for price rises. However, as touched upon earlier, drinkers increase their own prices by the very act of opening and depleting bottle numbers.

Ultimately certain whisky brands have become status symbols because of the economic capital contained within them. Having a collection of well-known expensive bottles can display wealth as well as knowledge. The ultimate economic statement of course are open rare and expensive bottles.

In the end, to reduce whisky to its utilitarian function is overly simplistic. Yes, it can be drunk, but it also serves as a tool for social bonding, a symbol of cultural capital and even a financial asset. In this way it is not dissimilar to wine. It plays different roles for different people, and none of these perspectives are inherently right or wrong.

But crucially, it’s not just consumers who attribute this symbolic or economic value to whisky – it’s the producers themselves who

it’s because the industry itself has cultivated that perception.

The responsibility, then, does not lie solely with those who consume whisky for its symbolic or economic value but with the producers who have, through their own actions, encouraged this shift. They’ve crafted whisky into a product that transcends its basic purpose, reflecting the evolving role that whisky plays in our society today.

To say that whisky is just for drinking is to overlook its complex role in society. Whisky is a cultural artefact that embodies tradition, craftsmanship, and exclusivity. It drives profits for companies, pays dividends to shareholders, and holds symbolic weight for collectors.

While some may be put off by extravagant packaging or astronomical prices, these elements serve a purpose. They elevate whisky beyond its functional use, turning it into something more –an object of desire, a status symbol, and a piece of cultural heritage.

Discover the spirit of the Borders this Christmas!

The Borders Distillery is the first Scotch whisky distillery in the Scottish Borders since 1837, dedicated to capturing the true spirit of the Borders.

At The Borders Distillery, only locally-grown Scottish Borders barley is used to make their spirits, all harvested from 12 farms lying within 35 miles of Hawick. This helps to keep the delivery of barley as eco-friendly as possible, while also supporting the local economy.

Borders alt & ye is the first blended Scotch whisky out of the Scottish Borders since 1837, made entirely by The Borders Distillery in Hawick. A small batch of rye spirit was distilled and then matured in the same first fill bourbon casks as the malt, to create this remarkable and aromatic whisky. Boasting notes of soft spice, buttery pastry and baked fruits this dram will definitely bring some warmth this Christmas.

A limited release, the Long & Short of it is the second edition in the series of experimental blended Scotch whiskies. The distillers experimented with very short fermentation times of 55 hours and very long ones

in first fill ex bourbon barrels, before being married with single grain. The result? Fig pudding and butterscotch with fresh bursts of gooseberry skin and citrus zest.

You can enjoy both blends this Christmas in a WS:01-02 Combo Box for £60.

They also have their own Scottish Gin. Kerr’s Gin – every drop is made from Scottish Borders barley, and every grain grown within 35 miles of their Hawick distillery, entirely distilled by The Borders Distillery. This distinctive, award-winning

who was born in Hawick in 1779. With his passion for plants, Kerr would have approved of the Carterhead Still used to make this bright Gin, which gently steams the botanicals in the spirit vapours, rather than boiling them like most other Gin stills. This captures more of the subtle aromas and complex flavours. Their G&T Box is a Christmas exclusive that has everything you need to craft the perfect Kerr’s G&T.

Shop now at www.the bordersdistillery.com

Befuddled by the dizzying range of drinks on offer? Feel the fog of confusion lift with our eight-page guide to what the real experts drink

Sweet peat smoke with underlying

I first knew Ledaig as a very pale coloured NAS bottling that was readily available in the supermarket. As much as I enjoyed that, it has been great to see this brand come along in quality and reputation. The star of their core range for me is this 18-year-old, finished in

Fermented apricots and peaches, toasted nuts and citrus zest all intertwine with Sweet and spicy with the sherry casks and peat playing their part. Lingers for a long time.

BLENDED MALT

40 46

Glencadam is still very much under the radar, but this distillery makes great quality whisky across its range and offers value at each price point. This 13-year-old is packed full of tropical flavours and plenty of punch at 46% – my go to for a classic ex-bourbon matured whisky.

NOSE: Vanilla, coconut and fresh pineapple.

PALATE: Lots of vanilla custard, buttery pastry and green apples.

FINISH: The vibrant fruit flavours stay with a creamy vanilla sweetness.

An incredible value for money blended malt by the makers of Springbank that brings together all three distilleries in Campbeltown.

NOSE: Classic sea salt and brine along with nutty, creamy and spicy notes. A hint of ginger and stewed fruits.

PALATE: Those stewed fruits appear again with a salty edge, and subtle peat adds a layer of seasoning to balance the sweet syrup and treacle flavours.

FINISH: Old school whisky notes of leather and tobacco.

Fraser Robson

Based in the company’s spiritual home in Elgin, Fraser has been the Whisky Ambassador at Gordon & MacPhail South Street since 2018. Fraser is also one of the judges of the Scottish Field Whisky Challenge. been to with massive phenolic notes.

WHISKY AMBASSADOR AT GORDON & MACPHAIL, SOUTH STREET, ELGIN www.gordonandmacphail.com

XOP PORT DUNDAS 45 YEARS OLD SINGLE GRAIN SCOTCH WHISKY

LOWLAND SINGLE GRAIN

1,800 49.9

that celebrate Lindores Abbey’s centuries-old ties to the French village and Abbey of Thiron-Gardais where the Tironesian monks, who laid down the spiritual foundations of Scotch whisky, came from.

NOSE: Mellow vanilla cake, caramel syrup, baking spices and fruity plum jam.

PALATE: Oaky vanilla, butterscotch, plum jam playing with cinnamon, ginger notes and layers of roasted chestnuts. Silky texture on the palate, very well balanced and complex with a pleasing finish.

FINISH: Medium length finish.

LOWLAND SINGLE MALT

50 46

Lochlea is currently bringing through some fantastic whiskies. The distillery may be young, but the provenance and quality is apparent. Lochlea have matured their signature spirit in fresh first-fill oloroso sherry butts. The different cask make up highlights the distillery’s progression as the last in the popular sherry influenced Fallow trilogy.

NOSE: Delightful baked apple and sweet medjool dates.

PALATE: Manuka honey and nutty, fresh, malted bread.

FINISH: Rich, buttery sandalwood oils and mixed peppercorns.

This ultra rare Port Dundas 45YO was released last year to celebrate Douglas Laing & Co’s 75th anniversary. This Glasgow distillery is now closed, thankfully Douglas Laing & Co who are descendants of the same city are thriving!

Candyfloss, sticky date pudding and

gentlest of piquant sweet spices and honey.

OWNER, ROBBIE’S DRAMS WHISKY MERCHANTS, AYR robbieswhiskymerchants.com

The owner of Robbie’s Drams, Robin is a judge on various whisky panels including the Scottish Field Whisky Challenge. He is widely recognised as one of the first people to create a Whisky Festival back in 2003 and it’s still going strong (Whisky An A That).

SINGLE MALT

Glen Moray were one of the first distilleries to experiment with port casks, with this expression joining their Elgin Classic range of affordable no-age statement releases back in 2014. It’s treated to an 8-month finishing period in Tawny Port casks before being bottled.

350 46

This Speyside stunner uses wormtub condensers to create meaty notes that captivate whisky enthusiasts and this expression has often been referred as an older style of whisky.

NOSE:

Chocolate and vanilla.

PALATE:

Sulphur, zingy, long and complex. period

Cinnamon and red berries with hints of tangerine and bramble jam.

FINISH:

Wood spices, dark chocolate and blackcurrant.

SINGLE MALT

70-80 43

NOSE: Fruit crumble, engine oil and rubber.

PALATE: Herbal, minty, fresh fruit and vanilla.

A sherried single malt from Tomintoul, specially designed to be paired with cigars or chocolate! A no-age statement Speyside, which has been matured in Oloroso sherry casks, sourced from Andalucia.

NOSE: Maple loaf cake, cinnamon and a whiff of smoke, with spiced raisin cookies.

PALATE: Toasted oak, followed by cracked black pepper, mocha and vanilla.

FINISH: Buttery oak and roasted coffee beans.

Colin Hinds

OWNER OF TIPSY MIDGIE EDINBURGH BAR www.tipsymidgie.com

Colin Hinds is an award-winning chef and restaurateur with over 30 years in the industry. A champion of Scottish food and drink, Colin’s whisky bar the Tipsy Midgie Edinburgh has been open for 2 years, winning both Scottish Whisky Bar of the year 2023 & 2024 and himself being voted Scottish Whisky Guru of the year’.

43.50 46

Smokehead is a brand owned by Ian MacLeod, owners of Glengoyne. When first launched it was alleged the whisky was sourced from Ardbeg, these days it is sourced elsewhere on Islay.

NOSE: Intense, with peat smoke, iodine and green malt.

PALATE: Round, malty and sweet with chewy smoke and brine.

FINISH: Long with medicinal peat and sweet malt loaf.

unpeated Bruichladdich, heavily-peated Port Charlotte

and the extremely-heavily-peated Octomore. This bottling is their Islay Barley release for this year and is the second peatiest whisky they have ever bottled at 307.2 PPM, compared to Port Charlotte’s 40 PPM.

NOSE: The nose is initially sweet and tightly closed but with water suddenly there’s green malt, gentle spice, freshly sliced green chilli pepper, followed by campfire, smoked bacon and linseed oil.

PALATE: Sweet malt, green pepper, muscovado sugar, cloves, baked plums and campfire smoke.

FINISH: The finish is long with waves of rolling peat smoke, BBQ and maple smoked bacon.

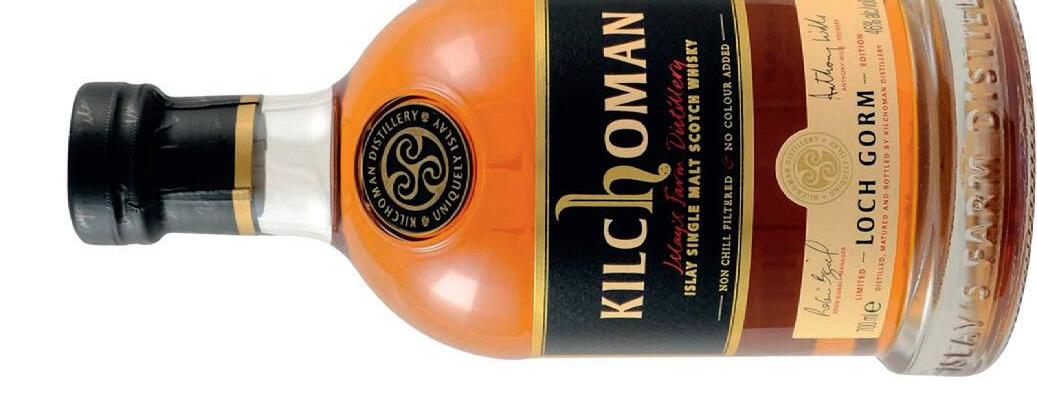

KILCHOMAN LOCH GORM

SINGLE MALT

84 46

This is the yearly 100% sherry cask matured release from Kilchoman, their whiskies are generally big, smoky and intense.

NOSE: Creosote, smoke and fruit cake.

PALATE: Orchard fruit and Germolene, then dried plums, raisins and spice.

FINISH: Rich with dried fruit then smoke and a lingering medicinal iodine which slowly fades.

CO-OWNER, THE GOOD SPIRITS CO., GLASGOW www.thegoodspiritsco.com

Matt can usually be found at the helm of The Good Spirits Company on Glasgow’s Bath Street, hosting monthly whisky, gin and cocktail tastings.

30 46

A blend created by the skilled team at Gleann Mòr, evoking Leith’s esteemed and influential whisky blending history. The Legacy combines aged malt and grain whiskies with some matured in sherry casks.

NOSE: A dessert-like nose filled with

vanilla, ginger spice, apricots and ice cream.

PALATE: A chewy texture reveals bread initially then creamy fudge and pastry.

FINISH: A small hint of smoke but then cascades of delicious sweet

DRAMS and as their labels.

The newly launched Decadent Drams range is home to various selections and concoctions by independent bottlers Decadent Drinks. Curiously minded and pushing the boundaries of the indie bottling category, their releases are as creative as

Chocolate coated raisins, thick dark cherry syrup with a subtle hint of smoke.

Elegant but complex with rich oranges, lebkuchen and butter cream. Tangy jelly and cocoa.

FINISH: Sherry with very gentle peat, evoking drams of yesteryear with musty old school characters. Coffee and black forest gâteau.

Watt Whisky. Based in famed whisky town Campbeltown, the Watts are finding unusual casks and experimenting

with blends such as this one which brings together 12-year-old North British and a younger peated blend.

NOSE: A musty peat smoke then hay and biscuits, before toasted almonds emerge.

PALATE: Marshmallows, juicy elegant smoke and caramel. A long biscuity finish with ginger and a hint of bonfire.

Sam Brabbs PURCHASING MANAGER, ROYAL MILE WHISKIES & DRINKMONGER www.royalmilewhiskies.com

Sam has worked for Royal Mile Whiskies for over a decade after first falling in love with whisky at Edinburgh University’s Water of Life Society.

JAPAN • BLENDED MALT WHISKY. NON AGE STATEMENT, EX-SHERRY BUTT, FINISHED IN A MIZUNARA VAT

112 46.5

The Mizunara wood is talked about a lot. There is a distinct tone in this glass, it reminds me of a quality oloroso. It’s a complex and intelligent dram that pairs really well with fatty meats.

NOSE: Amazing! It has an ethanol tone akin to a Riesling. Plums and spice play a strong role too.

PALATE: Distinct spice and slightly herbaceous. There is song of sandalwood in the background. Full bodied with a thick mouthfeel.

FINISH: Lengthy, malty and dry. It stands proud

SINGLE MALT WHISKY. NON AGE

43 43

I couldn’t wait to try this as I am a dual citizen with New Zealand! Soft and welcoming, its bright colour exudes freshness and a sense of promise. It’s a wee sunrise in a glass – perfect for my introduction into Kiwi whisky.

NOSE: Everything that hits the nose is subtle, but if you listen carefully it has wonderful notes of honey, caramel and forest leaves after the rain.

PALATE: Well balanced and coats the gums. Nail varnish and a slight salinity give it that fresh feel.

PUNI, ARTE LIMITED EDITION NO. 4

67 48

FINISH: A soft and easy finish taking me to tinned mandarins and a touch of demerara sugar.

ITALY • ITALIAN MALT WHISKY. 5.4 YEARS OLD, MATURED IN EX-MERLOT CASKS

One of the coolest looking distilleries, and the bottle is bold! The experience has an innovative and confident vibe to it. Its colour and taste follow in the same vane. All in all, a memorable journey.

NOSE: Woodland heather and burning autumn leaves on a bonfire.

PALATE: Slightly thin but with a nice peat smoke, moves to a dark chocolate, bittersweet character.

Three-time Olympian and Olympic medallist in sailing. After Tokyo 2020, Luke started a whisky venture with his sister, Anna, specialising in bespoke premium bottling for private clients (The Patience Spirit Co.) and an independent bottling brand, Unkiltered. with its shoulders back.

FINISH: A lovely wasabi-style burn that softens to sticky treacle sweetness.

CO-FOUNDER AT UNKILTERED SPIRITS & THE PATIENCE SPIRIT CO www.unkilteredspirits.com, www.thepatiencespirit.com

The number of aged gins on the market has exploded, but what are drinkers to make of this new trend?

Written by Geraldine Coates

Most gins are rested in large metal containers for a short time after distillation to allow the subtle flavours of the botanicals achieved through the distillation process to settle and ‘marry’.

There has, however, been a trend toward ‘aged’ gins and, indeed, the highly successful online drinks retailer, aster of alt, currently lists over one hundred of them. Usually described as cask aged, barrel aged, or rested, what they do all have in common is that they have all been stored in wooden casks post distillation in order to take on some of the flavours of the wood or the wine or spirit that was previously stored in the casks.

Why? you might ask, given that most people love gin precisely because of its bright, clean, piney flavours that go so well with tonic water. nd those flavours are exactly what has made gin the pre eminent mixable spirit for all the classic cocktails for decades.

When the first aged gins began to emerge around they were greeted with a certain cynicism. nderstandably since the claim was that ageing gin in wood is a return to the authenticity of the gin of the 19th century, when it was stored and transported in wooden barrels on long sea voyages. This argument is not particularly convincing because most wooden storage barrels were used and reused many times and would not have imparted further flavour.

‘ pirits weren’t aged in barrels for flavour purposes until the mid s,’ says spirits

expert hilip uff. ‘But distillers did still use barrels for storage. In fact they picked neutral barrels for transporting their liquor so that the barrel’s flavour wouldn’t affect the spirit.’

We both also agree that the idea that the gin of the ictorian Gin alace was inherently better than modern gin is wrong. In fact, the opposite is true modern distilling techni ues and stricter uality controls mean that we now live in a golden age of gin production.

espite the easily debunked marketing hype, there remains no doubt that aged gins do bring something new to the flavour party.

I personally don’t buy the initial stated purpose, which was to expand our drinking repertoires to include gin as a digestif akin to a fine malt whisky or venerable old rum. ery few people drink neat gin, despite what the marketeers say. But there are many other

‘The real prototype of an aged gin came about by accident in the 1920s when some gin was left to age in sherry casks by mistake’

possibilities.

Most aged gins taste like a hybrid of new make whisky and gin with malty, woody, caramel type notes depending on which type of wood has been used in the ageing process.

So, what’s the best way to drink them? A gin and tonic with aged gin simply doesn’t work. Nor does aged gin suit a Martini. But the Martinez, an old school version of the Manhattan that is made with equal parts gin and sweet vermouth plus maraschino li ueur and bitters, has the robust flavours needed to balance and complement the spirit and not be overwhelmed by it, so is the perfect option.

Manhattan, the Old Fashioned and the Highball made with ginger ale are easy to make and great ways to drink this unusual spirit.’ Do resist however any attempts to convince you that aged gin is the perfect addition to the Negroni – it’s not.

My other spirits guru, Craig Harper, has some useful advice for people wanting to experiment with the more complex flavours of aged gin.

‘Since this type of gin has a lot in common with whisky, you have to think whisky when you want to make cocktails,’ says Craig. ‘Classic whisky cocktails like the original

Funnily enough, the real prototype of an aged gin came about by accident in the 1920s when Booth’s (once the largest distiller in the country) left some gin to age in sherry casks by mistake. The resulting Booth’s Finest Old Dry had a slightly golden colour and such a mellow flavour that it was henceforth always ‘rested’ in sherry casks.

Sadly, at the time the fashion was for clear gin as that signified purity, so its reputation suffered.

But amongst the cognoscenti, it was lauded as the only gin for a Pink Gin by that great hero of drinks writers, for clear gin as that

antique bottles were long sought after as a type of Holy Grail of spirits by the geeks. The good news is that and available online. Much like whisky, gin

it is in production again

Much like whisky, gin can be aged in different types of barrel. Some use new American oak, like The Botanist. Other brands, such as Campfire Cask ged, use ex-bourbon barrels, while Beefeater’s Burrough’s Reserve is rested in wine barrels. There has also been a trend to age gin in barrels that once held whisky, especially in Scotland. Caorunn Cask Aged does this to great effect.

Beefeater’s Burrough’s Reserve is rested in There to age gin in barrels that once held whisky,

The other factor to consider is the amount of time the spirit has spent in wood, which is a crucial determiner of flavour. The ageing process for gin can be anything from three weeks (for example, Hayman’s Gently Rested), to the stonking twenty years (the time that Fifty/50 Gin ages half of its production for). The general consensus is that a shorter ageing time is preferable as it doesn’t take away the brightness and ‘gininess’ that one wants.

cask aged expressions from distillers all over the world. Multi-award-winning Swedish Hernö Gin pioneered the idea of maturing gin in juniper wood with the launch of its Juniper Cask variant. Here fresh woodiness and pine combine to produce an intensely juniper gin.

If you’re interested in exploring aged gin there’s plenty of choice, from conventional barrel-aged gins produced by the big brands to quirky offerings from the hipsters.

Or there’s Australian brand Four Pillars who have really pushed the boundaries with their Bloody Shiraz, made by steeping whole locally grown Shiraz grapes in Four Pillars Rare Dry for eight weeks then pressing the fruit and adding more gin. Each year’s vintage is slightly different and these limited edition bottlings consistently sell out.

Since most distillers like nothing better than the opportunity to play around with flavour, there’s a wealth of very interesting

One thing is for sure though – the possibilities of cask ageing have become irresistible to both producers and consumers, so we can undoubtedly look forward to more innovation and more choice..

TUIRC

SCOTTISH GIN

39.99 45

Small-batch gin from the beautiful Kintyre peninsula, aged in Bourbon casks for a sensuous and comforting winter gin.

NOSE: Rich toffee with gentle spice and smooth butterscotch.

FRENCH GIN

34.99 45

PALATE: The sweet and spicy effects of the Bourbon wood

make this a perfect gin for mixing with ginger ale and a curl of orange peel.

Made with 100% grape spirit, with botanicals including sandalwood and grape blossom.

FINISH: Luxurious and exciting, this is a gin for your Christmas drinks cabinet.

NOSE: Perfumed bergamot and weighty sandalwood balanced by traditional juniper notes and a hint of citrus peel.

PALATE: Juniper-led with floral notes, orange oil and peppery cubeb, all married together by the smooth grape spirit.

FINISH: Warming ginger and sandalwood, with a velvety, luscious mouthfeel.

Darnley’s to express their passion for local produce and a proudly international outlook. Only 600 bottles were made.

Heady kefir and warm galangal balanced by delicate

marigold and lemon balm.

PALATE: aperitif gin.

FINISH: Zippy and fresh but with deeper, warming notes of galangal. This is like sipping a cocktail at a beachfront bar in Thailand… or the West Sands!

Emili Fusaro

DIRECTOR, LUVIANS BOTTLE SHOP www.luvians.com

Emili is part of the next generation of the Fusaro family running award-winning bottle shops in St Andrews and Cupar. Luvians has an incomparable range of whisky, spirits and wine, along with a deli, cigar room and artisan gelato.

KENTUCKY, USA • BOURBON (SMALL BATCH)

$200-220 (APPROX. £158-174)

54, BARREL STRENGTH AT 108.2 PROOF

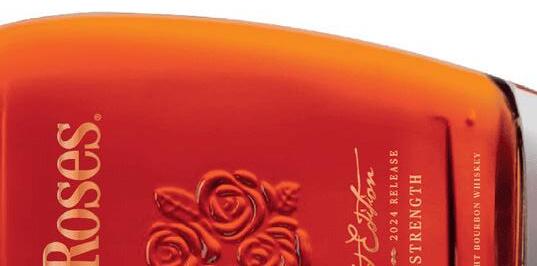

The founder of this distillery Paul Jones Jr. fell in love with a beautiful lady, he proposed to her, she arrived to marry him wearing a pretty corsage of four roses, from then he transferred the passion

Initially this has light, spicy, caramel notes which lead in to a slight leathery and tobacco smell, followed by sweetness of prunes and sugar.

Oaky notes smothered in an array of soft and stone fruits, raspberries, nectarines

DEAU COGNAC LOUIS MEMORY

FRANCE • COGNAC

220 40

This Cognac showcases the expertise of the Deau distillery. It has awards and recognition from many experts and is known for its excellent quality and craftsmanship. Perfect for those who really appreciate cognac.

NOSE: A rich medley of floral, sweet and delicate spice notes, with hints of chocolate.

PALATE: Smooth and better than the nose with all of the floral, spicy and fruity notes perfectly brought together with some coffee and chocolate in the background.

FINISH: A luxurious finish which lingers. This is one to be appreciated.