Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 1

Cathedral Music

ISSN 1363-6960 APRIL 2003

Editor Andrew Palmer

21 Belle Vue Terrace Ripon

North Yorkshire HG4 2QS ajpalmer@lineone.net

Assistant Editor Roger Tucker

Production Manager Graham Hermon

Editorial Advisors

David Flood & Roger Overend

FCM e-mail address FCM@netcomuk.co.uk

Website Address www.fcm.org.uk

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of the Friends of Cathedral Music.

Likewise, advertisements are printed in good faith. Their inclusion does not imply endorsement by the FCM. All communications regarding advertising should be addressed to:-

Roger Tucker

16 Rodenhurst Road LONDON SW4 8AR Tel:0208 674 4916 roger@cathedralmusic.supanet.com

inQuire Editor: Richard Osmond

10 Hazel Grove, Badger Farm, Winchester, Hants SO22 4PQ Tel/Fax:01962 850818

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used. We apologise to any individuals we have inadvertently missed. The Editor would be glad to correct any omissions.

Designed and Produced by: Marketing & Promotions

The Old Pottery, Fulneck, Pudsey, Leeds, West Yorks LS28 8NT Tel: 0113 255 6866 info@mypec.co.uk

Cathedral Music is published twice a year in April and October.

Cover: Rochester Cathedral. Peter Smith. Newbery Smith Photography. © Jarrold Publishing.

Cathedral MUSIC Cathedral MUSIC

CMComment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 Andrew Palmer George Guest: Tributes 6 Alan Mould, Jonathan Rennert, Sir David Lumsden, Alan Thurlow Maintaining a Commitment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Canon Ralph Godsall Shaping up for the Future 15 Robert Quinney and Philip Scriven The Lay Clerks Tale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 Harry Winter Canterbury Gospels 20 Michael Hawkes and Dr David Flood Cathedral Music in the British Library 22 Timothy Day Little Known, but Magnificent 27 Colin Menzies 40 Years On 30 Stephen Farr Romantic at Heart 32 Simon Morley inQuire 33 Richard Osmond A Unique Experience 37 David Flood interviews Allan Wicks Choirs and Cloisters: Obituary of Freddy Hodgson 42 Michael Guest 60 Seconds in Music 44 Julian Thomas FCM National Gatherings 46 Peter Smith T. Nobbly Turtle 48 Timothy Storey Percy Whitlock 50 Malcolm Riley Dr Donald Webster 1926-2002 53 Obituary Letters 54 Your news and views Proms Retrospect 56 Roger Tucker Book Reviews 57 The latest books CDReviews 58 The latest recordings Cathedral Music 3

Front

Back Cover: The enthronement of the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury 27th February 2003. Photo courtesy of David Manners©

Cover Photographs:

The Magazine of the Friends of Cathedral Music 13 Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 2/4/03 9:14 AM Page 2

The Friends of Cathedral Music

Registered as Charity No. 285121

An internationally supported Society – Founded in 1956

Founder

The Revd Ronald Ellwood Sibthorp (1911-1990)

Patron

The Rt. Revd E. W. Kemp

President

Dr George Guest CBE Vice-Presidents

Sir David Calcutt QC, Dr Lionel Dakers CBE, Dr Francis Jackson OBE Anthony Harvey Chairman

Professor Peter Toyne DL, Cloudesly, Croft Drive, Caldy, Wirral, Cheshire CH48 2JW. peter.toyne@talk21.com

Council

Donald Bunce, Colin Clark, Dr Lindsay Colquhoun, Philip Emerson, Malcolm Johnson, Jonathan Milton, Very Revd Michael Moxon, David Price, Geoffrey Shaw, Very Revd Michael Tavinor, Julian Thomas, Peter Wright.

Secretary

Michael Cooke, Aeron House, Llangeitho Tregaron, Ceredigion, Wales SY25 6SU

Tel: 01974 821614 joycooke@aol.com

Treasurer

Anita Phillips, Rowan Lodge, 53 Fourth Avenue, Chelmsford CM1 4EZ

Tel: 01245 352035 anita@rowans.force9.co.uk

Publicity Officer & Advertising Manager

Roger Tucker, 16 Rodenhurst Road, London SW4 8AR

Tel: 020 8674 4916 roger@cathedralmusic.supanet.com

Diocesan Representative Co-ordinator

John Craddock, 105 Casterton Road, Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 2UF

Tel: 01780 763756

Membership Secretary

Donald Bunce, FCM Membership Department, PO Box 207, Scarcroft, Leeds LS14 3WY

Tel: 0845 644 3721 (UK local rate) or +44 113 293 700 info@fcm.org.uk

Secretary for Gatherings

Peter Smith, Paddock House, 7 Orchard View, Skelton, York YO30 1YQ

Tel: 01904 470 503 PeterSmith@robertpeter.fsnet.co.uk

Sales Officer & Secretary for Leaflets

Joy Cooke, Aeron House, Llangeitho Tregaron, Ceredigion, Wales SY25 6SU Tel: 01974 821614 joycooke@aol.com

National Gatherings 2003/4

Summer Gathering and AGM

Peterborough Cathedral

13-15 June

Autumn Gathering

St Davids Cathedral

10-12 October

Spring 2004

Rochester Cathedral

Dates TBA

Summer Gathering and AGM 2004

Salisbury Cathedral

26-27 June

All information:

Peter Smith, Secretary for Gatherings, Paddock House,Orchard View, Skelton, York YO30 1YQ

PeterSmith@robertpeter.fsnet.co.uk

Non-members are welcome

Cathedral Music 4

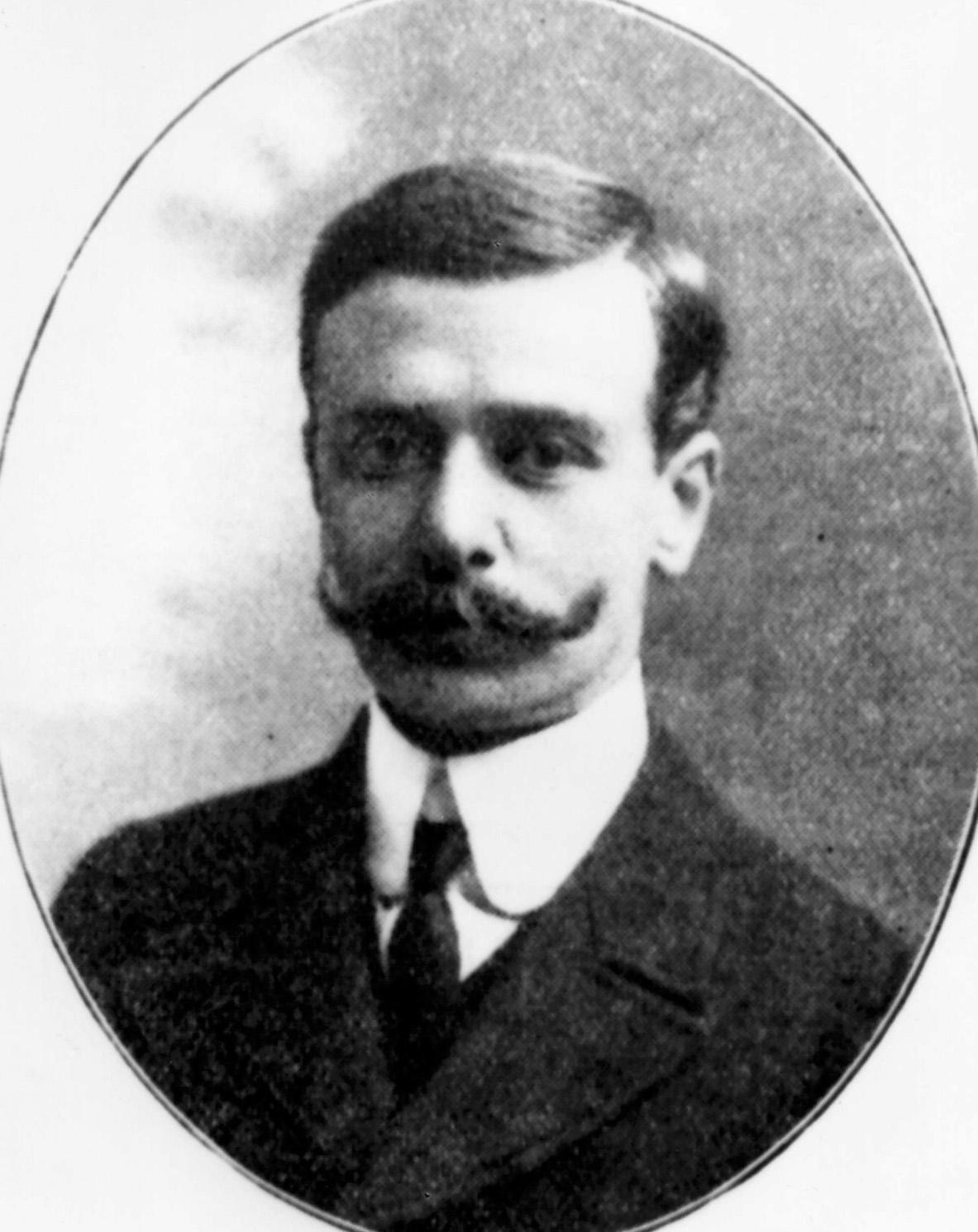

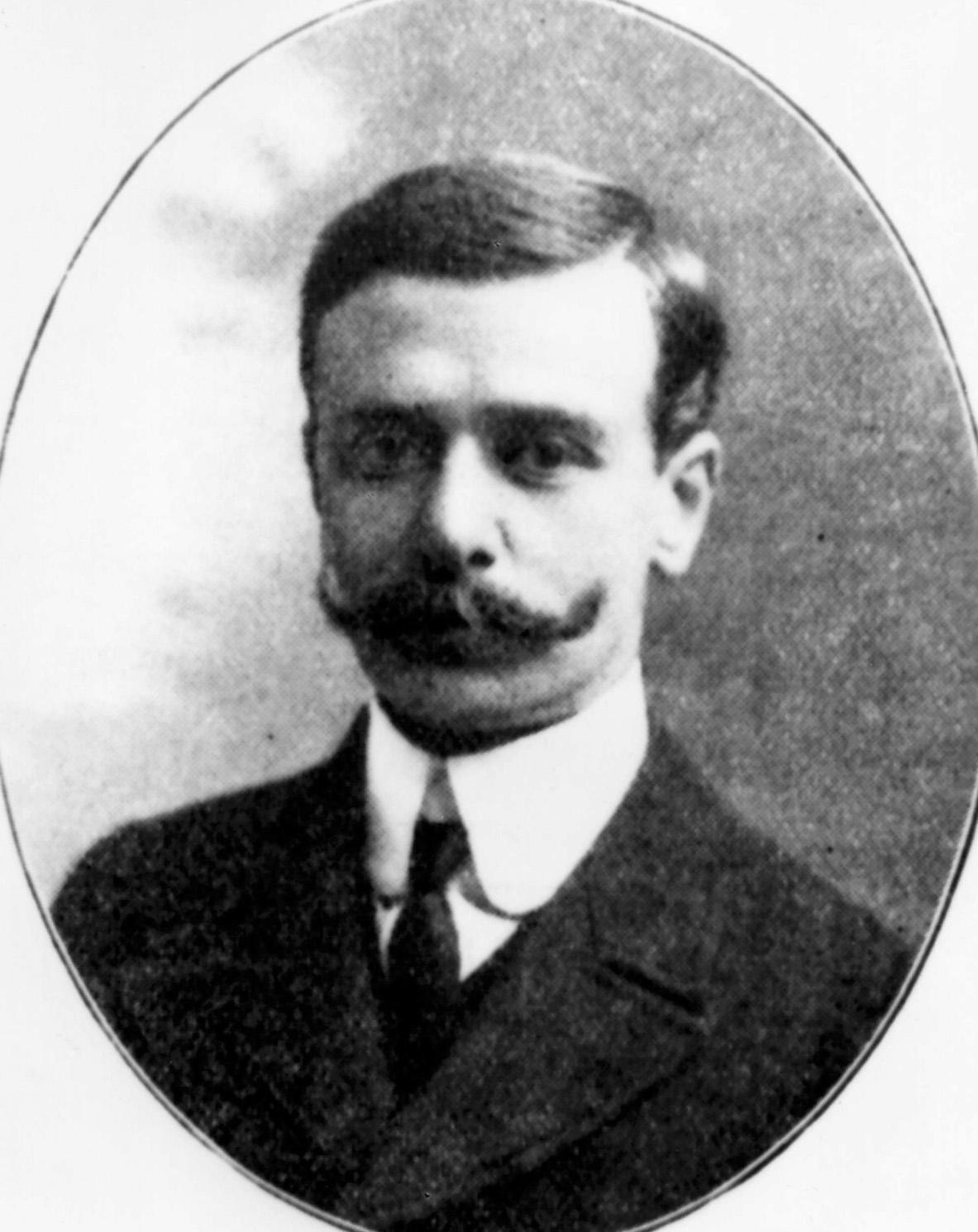

George and Nan on tour. Photo Alan Mould.

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 3

‘

’ CM Comment Andrew Palmer

nevertheless one he saw through. George died suddenly on 20th November last year aged 78, after suffering heart failure. Our condolences go to his wife Nan and their two children David and Elizabeth.

Traditional Virtues and something good about Songs of Praise

From generation to generation

George Guest’s reign at St John’s College, Cambridge, spanned 40 years as Organist, beginning with a fruitful two-year partnership with the organ scholar straight from Selwyn College – David Lumsden – as his first assistant who later became Organist of Southwell Minster.

George had a huge influence on standards in cathedral music and his legacy is still very much alive, with no less than nine of his organ students (St John’s designation of organ scholar) becoming cathedral number ones. In chronological order they were: Peter White, Jonathan Bielby, Stephen Cleobury, John Scott, David Hill, Adrian Lucas, Andrew Lumsden (crossing a generation), Andrew Nethsingha and Philip Scriven. There are also many others, including Jonathan Rennert (St Michael Cornhill), Ian Shaw (the former sub-organist at Durham Cathedral) and the late, lamented Brian Runnet (the Organist of Norwich Cathedral), so tragically killed in a car accident.

The final chapter in this career dedicated to cathedral music opened after George had left St John’s. He accepted the Presidency of FCM and threw himself into our activities, attending gatherings at which he endeared himself to members because of his eloquent advocacy of the highest standards in choral services, and opposition to any hint of populism. He was quite horrified at the idea of a ‘jazz evensong’, or using popular instruments to attract people to worship in Anglican churches, declaring these strategies to be ‘unworthy’. He had no interest in being merely a figurehead, and attended meetings of the Council, at which he spoke out on all matters including grants and those which touched on his lifelong beliefs. His final duty was to chair the group which chose Peter Toyne as our new chairman, a task he found onerous but

Imagine my surprise at hearing Pete Waterman on BBC Songs of Praise from Coventry Cathedral (Sunday, December 15th) waxing lyrical about traditional Christmas carols and the role of choirs. It was a programme that came to fruition after he attended a Christmas concert at his daughter’s school in 2001, where there was not one traditional hymn sung throughout the evening. The head of Religion and Ethics at the BBC agreed to make a Songs of Praise programme that would take a group of children and teach them how to sing ‘proper’ carols. The plan was to pick around 80 strong-voiced candidates from the West Midlands aged between 11 and 18 and form a choir which would sing in Coventry Cathedral. Local schools began the auditions, whittling down about 5,000 possible singers to a more manageable 360. A panel (which included Rupert Jeffcoat, Master of the Music at Coventry Cathedral) was chosen to cut the numbers down, to fit a format close to that of ITV’s Popstars and Pop Idol

The next day in the Daily Mail Mr Waterman expanded upon comments made in the programme, writing about his sadness at the way music has been so downgraded in the school curriculum and giving some interesting anecdotes. It is a shame that this innovation came out of the absence of the traditional. For me it is not just at Christmas that this problem occurs. Anyway, congratulations to someone as popular as Pete Waterman for raising this issue and even more applause for Songs of Praise for spotlighting this crucial issue

DVDs v CDs

According to some doom-mongers the death of the compact disc is nigh. There does seem to be a proliferation of compact discs in all areas of music to the extent that the market is being saturated and this presents serious problems for the viability of the industry. Some of the finest cathedral choir and organ recordings

were done in the era of direct-cut disc recording then later, on analogue tape and now using digital media. The medium is less important than the atmosphere at the recording sessions. Earlier systems, because they precluded editing, demanded one-take performances. It’s like live broadcasting: you can’t have a second go at it, so you tune yourself up to a higher pitch of readiness. By the same token, recordings made at live performances in front of an audience very often have the inspirational edge on studio-based sessions. I worry about whether record producers can create the environment which achieves an inspired performance at a recording session which is not an actual service. Sometimes recordings are approached in too clinical a way. Our late president was never guilty of this: he always regarded each session as an act of recreation, as is true of Sir David Willcocks and Barry Rose.

Is the repertoire being done to death?

What is the rationale for producing 70 minutes of cathedral anthems one after another or for that matter 12 pairs of canticles, which were not written to be performed in this way? Record producers however tell us they sell. It’s a phenomenon that has taken off through the advent of the compact disc with its extra playing time. Could it be that the spiritual element is increasingly lacking as the catalogues get larger and larger?

The exciting new phenomenon of the DVD (Digital Versatile Disc) has not yet taken off. As Roger Tucker is discovering, there is much more to enjoying a DVD than just sitting in a comfy chair in front of the television: it is multidimensional and interactive. (Roger will be examining and reviewing DVDs in the next issue). So let’s invest in DVD players, which are now rapidly dropping down in price, and open up new horizons for cathedral music enjoyment in the home. David Hill wants to explore this at St John’s College, Cambridge, when he arrives there later this year as he told David Flood in the last edition of CM.

STOP PRESS

As we go to print we learn of the death of one of our vice-presidents, Dr Lionel Dakers. A full obituary will appear in the October edition

Cathedral Music 5

‘

‘George had a huge influence on standards in cathedral music and his legacy is still very much alive.’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 4

George Guest 1924-2002 A Tribute

Former CATHEDRAL MUSIC Editorial Adviser

Alan Mould, Headmaster of St John’s College School, Cambridge from 1971-90, looks back over the life of our late president.

Ours is the age of the mobile: upwardly mobile for preference. Stay in a post for five years and colleagues start muttering about lack of ambition. Cathedral organists are expected to be lofthoppers: organ scholar here, suborganist there, the top job in a modest place, the top job in a grand place, then – if you’re lucky – the top job in the top place. Fortunately not quite everybody succumbs to this restlessness. There is another way, but it is open only to the very special: find your job and make it the top place.

That was George Guest’s way. His professional CV could hardly be briefer: chorister at Bangor and Chester; sub-organist at Chester; then to St John’s College, Cambridge, first as Organ Student then as Organist (for 40 years) and Fellow (for 46). That’s it.

Very boring? No ambition? Nothing could be further from the truth. George’s professional career was, in his chosen field, amongst the most exciting, energetic and influential of all time.

Of course, George’s professional grasp extended far beyond the confines of a single college. For almost 30 years he was a university lecturer at

Cambridge and for much of that time also University Organist. For a year he undertook a professorship at the Royal Academy of Music. He was one of the RSCM’s special commissioners and an assiduous examiner for the Associated Board. As his renown grew, so responsibilities came his way, responsibilities which he undertook with generosity, being at various times president of all three leading associations of organists, not least the Royal College itself. He cherished the invitation to become president of FCM. And there were specially strong and active links with Welsh and American music. A fluent Welsh speaker, he became a major figure at eisteddfods. And his choir-training in America was a special joy to him, continuing after his retirement from Cambridge. But amidst all this widespread busyness, never was there the slightest doubt that his heart, mind and soul were centred on his beloved St John’s College and its chapel music.

Important foundations had already been laid at St John’s by George’s distinguished predecessor, Robin Orr. There is no sense in which it could be said that George took over a run down or failing establishment. Robin’s time as organist had been interrupted by

the war; in the early 1950s it had become clear to him that his major work was going to be in composition and teaching. But, before he persuaded a doubting college council to let him hand over the chapel music to his 27 year old organ student, Orr had already laid the foundations of what, under George, was to be a transformation. He had brought about a major rebuild of the organ, including, at George’s urging, the striking Trompeta real . And he had phased out the last of the ageing lay clerks, replacing them by altos, tenors and basses made up entirely of young, enthusiastic undergraduate choral students.

One major problem remained to be tackled. The St John’s choristers were drawn from one of the last of the country’s elementary day-boy-only choir schools, of a kind normal at the turn of the century but by 1950 almost everywhere replaced by more academic and challenging preparatory schools. Local boys joined the tiny school and the choir at the age of seven or eight and left when their voices broke to go on to apprenticeships or clerkships or trade. Down the road at King’s was a choir school that selected from all over the country and boarded bright, clever boys from cultured, professional homes, preparing them for scholarships to the best public schools in the land. George needed better quality treble material to work on. In 1955 the much-loved Sam Senior, headmaster of St John’s College Choir

Cathedral Music 6

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 5

‘George’s professional career was, in his chosen field, amongst the most exciting, energetic and influential of all time.’

School since 1912, was due to retire. George was determined to seize the hour. But so were some of the college council who saw it as the opportunity to relieve the college of a choir school altogether. Battle royal ensued, culminating in a campaign, engineered by George, to rain down upon the master and fellows letters and telegrams from all the country’s top musicians (including a famous one from Vaughan Williams in Italy, a special treasure in the Guest archive) begging the college to retain its choir school. George won. A substantial house was found and converted for school use, a good headmaster and staff were appointed, and in September 1955 the new preparatory choir school was up and running. But the college had said no to boarding. George, nevertheless, elected nonlocal boys to choristerships and boarded them in nearby homes – then presented the college with an obviously unsatisfactory fait accompli . During 1957 builders converted the school’s upper floors into dormitories. George had all he wanted: a first class organ, twelve keen choral students and the educational facilities for recruiting choristers of high potential.

Now all that was required was a choirmaster of genius. A well-known musician tells of how, when he was a choral scholar at King’s, studying in the music faculty, George Guest as a young university lecturer offered a masterclass on the training of boys’ voices by way of attendance at one of his morning chorister practices. A group of King’s choral scholars decided to go along, partly for a lark. As the practice went on they were more and more amazed. At the end they burst into spontaneous cheers. It had been revelatory.

The speed with which George moved his choir into the top league was astounding. Within a decade he had begun recording for Argo, starting with an anthology of popular choral items, notably a solo Hear My Prayer from the young Alastair Roberts. For many of his 60 or so recordings, continuing demand has ensured that CD reissues remain in today’s catalogues. Some of these broke new repertoire ground; others – one thinks especially of his Britten Missa brevis and Ceremony of Carols – brought to wellknown music a brilliant new timbre of sound. Others were simply very fine performances, such as the series, taken over by St John’s from King’s, of the Haydn masses which the then Prime

Minister, Edward Heath, took as his gift when he visited the Pope in 1972.

Broadcasts of the St John’s choir had begun in the 1950s and in due course they captured the airwaves for two major regular items, the Ash Wednesday Evensong with its Allegri Miserere mei (in Latin, not English as sung somewhere else) and, later, the Advent carol service of music and readings in a structure unique to St John’s.

Recitals outside Cambridge began to feature, at first modestly insular and later on a world-wide scale. There were difficulties about these. In the first place, George had a dread of flying and it was only with great courage at first that he faced flights to the USA and later as far afield as Australia and

underestimated. When, in 1978, the choir sang in the Sydney Opera House, all 2700 seats were sold and a further 2500 hopefuls had to be turned away. By this time his fame as a choirtrainer and the prestige of his choir meant that he was attracting to St John’s as organ students, choral students and choristers some of the finest young candidates in the land. This is part, but only part, of the explanation for the galaxy of household names now in high esteem who were trained by George: directors of music at King’s, St John’s (soon), St Paul’s, Winchester and two of the Three Choirs Festival cathedrals, the founder and director of the King’s Consort, leading operatic baritone Simon Keenlyside, to name just some

Japan. Then the tutors were not keen that their undergraduates should have their studies interrupted and the bursars were wary of commitments that might see the college bailing out a financial crisis. But on money George was pretty canny. Faced with quite proper bursarial tight-fistedness he managed to beg substantial gifts from well-wishers, placed in bank accounts drawable only on his own signature. And by and large he ensured that tours paid for themselves, initially, as in his 1970 tour of the United States, being his own tour manager , subsequently securing watertight funding from impresarios in host countries. Indeed, his ability to pull in the crowds was sometimes

of the very top achievers amongst the many distinguished musicians he nurtured. His recruitment techniques could be idiosyncratic. There was a little-publicised occasion when an exceptional bass candidate came to compete for a choral award, stating King’s as his first choice and St John’s as his second. That year St John’s examined in the morning. George was determined to ‘hook’ him and, with some connivance from the then dean, persuaded the young man to lunch with them. Two bottles of sherry and uncountable brandies later the poor man was capable of no more than being assisted onto a train at Cambridge station. King’s neither saw nor heard him. He proved an

Cathedral Music 7

➤ Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 6

‘The speed with which George moved his choir into the top league was astounding.’

excellent St John’s choral student. It had been a good lunch. When choosing boys there were some clear guidelines. Any boy who might grow stout was unlikely to win a place; on the other hand younger brothers from proven good stables began with a huge advantage. A sparkly manner helped. ‘How old are you?’ George asked one candidate. ‘Seven’, he replied; ‘And how old are you, sir?’ He was in!

Boys’ voice trials revealed two sides of George’s character. In the morning, in the privacy of his college rooms, he could be, without any unkindness to the candidate, hilariously funny, capable of drawing out the most unlikely home truths. In the afternoon, in chapel, when the short-listed sang in the presence of everyone’s nail-biting parents, he was wondrously and gently kind and encouraging. Every parent left

feeling that their son had acquitted himself well, whether successful or unsuccessful.

How was it done, this brilliant achievement of his? How did he not only create one of the greatest of all choirs but raise the whole level of expectation of what a fine choir should and could achieve, and bring about a widespread enrichment of the sound heard in English cathedrals and colleges? Above all, standards mattered. Evensong, even with next to nobody there, had to be very, very good. It was an act of worship and only the best was good enough. Because it mattered so much to him, the contribution of those playing and singing with him had to be equally committed. Idleness or casualness, a tenor who had failed to learn his notes or a chorister who yawned, instantly brought forth the cold wind of his

GHG: The Early Cambridge

Years

Sir David Lumsden, Assistant Organist, St John’s College, Cambridge, 1951-53 recollects.

George and I came up to Cambridge within a year of each other, he in 1947 from the Royal Air Force and myself in 1948 from the Royal Artillery. George was four years my senior and had seen war service: I had simply served two years as ‘Organist of Stonehenge’ (strictly speaking the Garrison Church at Larkhill). He was organ student at St John’s, I was organ scholar at Selwyn and the gap seemed enormous, almost unbridgeable. At first I naturally gravitated towards King’s - the Christmas Eve carol service had penetrated even the northern outback from which I came - and I soon became a pupil of Boris Ord. John’s at that time was more low-key, producing excellent music under Robin Orr but lacking the public impact of the more famous choir ‘down the road’. This was to prove George’s great inspiration and challenge, very much in his mind from the start. He and I hit it off at once and soon we were collaborating musically. He would invite me to accompany concerts with his Lady Margaret Singers, at that time the leading (the only?) credible mixed chamber choir in Cambridge, long before the admission of women to men’s

dismay and disapproval. It was no fun being excluded from the warmth of his gratitude. The notes indeed had to be right, but that in itself was insufficient: there had also to be feeling. A note was only part of a phrase, and all phrases had a shape which was itself part of a larger passage. Every singer had to watch, not so much the beat (‘What beat?’ I hear ex-choral students asking!) as the mood, the emotional movement, the electric charge he was offering. As the climax of a passage drew near his left hand would grasp his neck (Was he suffocating? No, he was calling on the boys to give him more throat timbre) and his right hand would become a tight fist, shaking rapidly in passionate vibrato. On occasions such as this, simply from the congregational stalls one knew one had experienced something transforming, miraculous almost. One former choral student recalls such an occasion in the Abbaye aux Hommes at Caen when, towards the close of a Tallis mass, the men did not know whether they would get to the end as their eyes filled with tears at the wonder of it. I too carry Tallis ever in my memory. Throughout the 1980 tour of Japan George offered as an encore the little five-part hymn O nata lux de lumine. For me, had they sung nothing else, that would have been

colleges and the burgeoning mixed college choirs which now adorn Cambridge musical life. One performance sticks clearly in my mind – Britten’s Rejoice in the Lamb in Selwyn Chapel. It was my first experience of music making in public at that level and I was terrified. I was comforted to learn that George felt the same way: his sangfroid on the podium belied the nervousness and punishing self-criticism which he suffered then and (I believe) for the rest of his career. The most vivid illustration of this came early in his first year as Organist of John’s - he was so uncertain of himself that the offer of a university lecturership was too much for him on top of his new responsibilities with the Choir and he disappeared for two weeks to sort himself out: he had to be coaxed back.

His appointment as Organist of St John’s in 1951, immediately after completing Tripos, staggered the musical world, and not just in Cambridge. The only comparable shock had been Francis Jackson’s appointment (a mere lad he seemed at the time) immediately succeeding Sir Edward Bairstow at York in 1946. The immense distinction and success

Cathedral Music 8

‘How did he not only create one of the greatest of all choirs but raise the whole level of expectation of what a fine choir should and could achieve.’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 7

beauty enough. Sometimes the commitment asked for or accepted was almost beyond reason. One night, during the second choir tour of Australia in 1982, the head chorister and chief treble soloist, Hal Vernon, walked through a plate-glass window. He needed 69 stitches. The following evening he was on stage singing his solos.

It would be wrong to imply that George’s great moments were always the climaxes. Amongst the most wonderful occasions were when he chose to accompany the psalms. Sometimes it was simply a meditation on the chant’s harmony; sometimes there would be a touch of wordpainting, but never obvious or vulgar. If there were thunder and lightning there might indeed be a palpable shaking of the stalls, yet never such as to drown the words. When the psalmist was in verdant pastures there might be just the hint of birdsong, almost inaudible. Sometimes the accompaniment was inaudible, because George had decided imperceptibly to withdraw all accompaniment, a most beautiful effect. Sometimes it was done for a practical as well as an aesthetic reason. An organ student would be alongside him. George would silently slip off the

seat and whisper ‘You take over now’; as imperceptibly as before, the organ student would resume a gentle accompaniment – and to widespread puzzlement George would be found down below, a member of the congregation. That would have been a little jape from a man with a lovely sense of humour and fun. He was never

of both these appointments we now take for granted, even as we rejoice in them, but at the time they were regarded as highly speculative and risky! George hit his first major problem on his second day in office. His organ student had played his first service on Thursday (the voluntary is still recorded in the Voluntary Book), failed LittleGo (the qualifying Latin exam at that time) and gone down by Friday, leaving George alone in charge of this great choir. The first I knew of this was an urgent hammering on my front door. By then I had graduated and become a research student at Selwyn under Bob Dart - more importantly, Sheila and I were newly wed and had set up home together in Garden Walk. By a happy coincidence Sheila had been at college with Nan, who was not yet on George’s horizon but later, of course, became his wife. “For God’s sake come and play for me this weekend - I’m on my own”, cried a harassed George and having by now vacated the organ scholarship at Selwyn I was free and happy to agree - ‘’Just for the weekend, ‘til I can sort something out”......... My first service included Britten’s C major Te Deum, then quite new and thought to be exceedingly difficult, especially for the organ accompanist: more panic but a strong sense of fellow feeling with George and a determination on the part of both of us to make it work. Indeed, so much so that the weekend turned out to be two years, two of the most happy and formative years of my whole life, both personally and musically. Working day in day out at George’s level, with a professional choir of men and boys, was quite a new experience for me. I owe George a great debt of gratitude for that time, without which my life and career would undoubtedly have been very different.

At the time the boys attended a small school in All Saints

happier than when teasing dance music or swing from the piano keys, a gift he had honed in Bombay night clubs when in the RAF. As choral students who joined him at the Mitre or the Baron of Beef for the 20 minutes between practice and Evensong knew, he was a brilliant raconteur and, if anything, an even more brilliant mimic. ➤

Passage and George soon felt the limitations this imposed, the basis of his determination to found what is now one of the most outstanding choir schools in the country. Lay clerks were gradually replaced by young, undergraduate choral students. This worked surprisingly well and quickly, mainly because the average age of undergraduates was much higher then than now since many of them had served for years in WW II and came up five or six years older than they do today, with great vocal advantage.

George set about a strict regime of training and enthusing the newcomers with results which soon attracted attention from outside Cambridge. At this time William Morgan, the great Johnian Welsh scholar and first translator of the Bible into Welsh, was to be celebrated nationally and George immediately set about having the choir sing in Welsh. Hour after hour was spent in this long and arduous process and I remember more than once thanking my lucky stars that I only had to play the organ in Welsh. The great moment came when the BBC broadcast the anniversary service, but only on the Welsh Home Service, which was transmitted only in Wales and not strictly audible in East Anglia. George and I went to great lengths to try to catch even a whisper of sound over our very ordinary radio, subjecting it and ourselves to all manner of contortions. Here, though we did not realise it at the time, was the first fruits of George’s famous love affair with Wales and its language and culture. Other more audible broadcasts and recordings followed and within the short two years I was at St John’s – as assistant organist, never as organ student since I was a member of another college – most of the foundations of George’s phenomenal success were in place. ➤

Cathedral Music 9

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 8

A couple of vignettes still stick in the mind – George regularly disappearing after the anthem and before the sermon on a Sunday evening – “play them out – I must change for Hall” –on his way across the road to the Mitre.

George at the joint choral scholar trials held in Boris Ord’s rooms in King’s: “Just watch out – they won’t take the real singers, they’re after blend before quality. Then WE can take them........”

There is no doubt that George’s first few years at John’s were uneasy, tinged with anxiety and personal insecurity. He was young and relatively inexperienced, he was naturally sensitive and self-deprecating, he felt he must compete with the choir ‘down the road’, he was not inspired by academic work for its own sake, the choir school needed radical reform, the men in the choir had to be recruited in a highly competitive environment and brought round to his way of thinking and performing – he had clear ideas of the style and sound he wanted but he also knew that his ideal could not be manufactured overnight. No one would believe this now. The John’s tradition as we know it is entirely George’s brainchild.

He created a choir of immense range and subtlety: he maintained the highest standards every day of his life: he established the Advent and Ash Wednesday broadcasts: his recordings are collectors’ items: he toured the choir infinitely farther afield than ever before. All this could only have happened through his vulnerability, his sensitivity, his musical instincts, his perpetual, restless searching for something different and better, his refusal to accept anything but the best from himself as from his colleagues.

(Was it the real Liverpudlian virger Wilf Rossiter speaking, or was it George being Rossiter? The two were indistinguishable.) And his social contacts with his singers were an important element in his deep care for them, as also was his profound distress when things went wrong: when an exam was failed, or unrequited love sent a young man into the depths, or a chorister seemed to lose all interest.

Faced with uncooperation or, much more rarely, downright opposition he could be a dogged combatant, as will be evident from his fight for the choir school. Great ingenuity was exercised in pursuit of what he deemed to be right. Some time, I think in the late 1980s, Cambridge City Council, as part of an ongoing but ineffective campaign to make Cambridge impenetrable to anything on four wheels, decided that St John’s Street would be one-way, southwards. George lived northwards. So he continued to leave the college gates and turn north into astonished southbound traffic. On the rare occasions when he was challenged by police or traffic wardens he would politely produce from his pocket a letter, dating, I think, from the 1950s when there had been some temporary

Many of George’s former organists and singers have gone on to forge distinguished careers for themselves – all acknowledge that George was one of the great influences in their lives and in the musical life not only of John’s and Cambridge but of Britain and indeed the whole Englishspeaking world. We all salute him. We mourn with Nan, David and Elizabeth. We all feel the greater for having known him – our loss is unfathomable.

Cathedral Music 10

‘Many of George’s former organists and singers have gone on to forge distinguished careers for themselves – all acknowledge that George was one of the great influences in their lives.’

George receiving a bouquet while on tour in Japan.

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 9

Photo Alan Mould.

restriction, giving him exceptional permission to turn north. (In any case George’s driving was the stuff of legend.) He was deeply suspicious of media people. Once, when the choir was being televised, his instructions to the choir were, ‘Gentlemen and boys: pay no attention to any men walking around with clipboards or calling each other ‘dear’. One Wednesday a live broadcast of choral evensong was to be followed by a recording of the men singing a plainsong compline. George had been unusually pressed and no time had been found to practise the compline. When the plainsong recording was due to begin and the producer asked “Are you ready?”

George said, “Yes we are. Right now, gentlemen, exactly as we rehearsed it yesterday, please”.

His 40 years as Organist were anything but static. Change was gently effected: the introduction of compline and plainsong; Sunday matins giving way to Sunday eucharist with wonderful opportunities for new repertoire; the college’s long-serving hymn book being beneficially replaced by the English Hymnal. Traditions like the Ascension Day carol from the tower were enhanced and novelties soon became traditions,

such as the annual Welsh evensong on St David’s Day. Above all, the range of music was continually widened, forwards by the commissioning of new works, backwards to the earliest of the Tudors, outwards from Britain to embrace composers from Italy and Germany,

Langlais’s Messe Solonelle was sung superbly in the enthralled hearing of its blind and aged composer. But then every day of my 19 years working in partnership with George was a privilege and a joy.

There is nothing conventional if I choose to end by recording that little of this would have been achieved from this passionate, sensitive man if he had not been constantly supported, encouraged and loved by his caring wife Nan: always there, never ruffled, offering security and calm in their comfortable, welcoming home. They are blessed by two splendid children, David and Elizabeth, both themselves musicians, and – a special late joy of George’s closing years – two little grandsons. To Nan and the family, I am sure, all members of FCM offer their deepest gratitude, condolence and blessings.

Scandinavia and Russia, the United States and, above all, France. He had a special feeling for 20th-century French church music, to which his great recordings of Fauré, Duruflé and others bear lasting witness. One of the greatest privileges of my life was to be present at the college eucharist at which Jean

With thanks to a number of helpfully reminiscent friends, most particularly Canon Charles Stewart, Precentor of Winchester.

As we go to print we have learned that a memorial service for Dr George Guest will be held in the Chapel of St John’s College, Cambridge on Saturday 3 May 2003 at 12 noon – it is however by ticket only.

Jonathan Rennert Remembers

Jonathan was Organ Scholar at St John’s (1971-4). He has been Organist & Director of Music at St Michael’s Cornhill, in the City of London, since 1979. Here he looks back at his time as one of George Guest’s organ scholars.

Muchhas been written about George Guest since he died last November: about his outstanding achievement in raising the St John’s College Choir to international prominence; about his adoption of a special style of boys’ tone, as well as the introduction of a new musical repertory to the Anglican liturgy; and about his lasting influence on generations of former choral and organ scholars who now sing, play and conduct in churches, cathedrals and concert halls the length and breadth of the country. My brief, as one of his former organ scholars, is to contribute a personal viewpoint. Before going to Cambridge, my piano and organ teachers had made me aware that although one’s performances should be historically aware, natural laws of breathing, movement and stress would always ultimately decide questions of musical interpretation. George’s intuitive approach to choral music complemented this teaching. Tempi, style, rubato and dynamics seemed obvious to him; and, when his blood sugar level may occasionally not have been at its highest at a pre-evensong rehearsal, he could show

his frustration that not all his musicians were approaching a setting or anthem from the same perspective. Any tension at rehearsal, though, tended to be sorted out in the Baron of Beef or the College bar later. “A pint of Abbot, George, or a Bell’s?”

He was enormously proud of his choir, and his loyalty to his singers was reciprocated: they not only admired his fine musicianship, but also delighted in what they saw as his mild eccentricities: his advocacy of anything Welsh, his loyal support for Chester City football team, and his pretence at naiveté in telling stories. When former choral and organ scholars meet, we still, almost without thinking, do our ‘George impersonations’ as we converse.

When I was George’s organ scholar, David Willcocks was in charge of the superb King’s Choir down the road. King’s was renowned for its beauty and blend. By contrast, George encouraged both men and boys to sing almost as soloists, with energy and emotion, and always intense sense of the inflexions and meaning of the words. This could result in a loss of

Cathedral Music 11

➤ Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 10

‘Every day of my nineteen years working in partnership with George was a privilege and a joy.’

Alan Thurlow, Organist and Master of the Choristers at Chichester Cathedral and FCM’s third Chairman worked closely with George Guest on FCM matters. Here he pays his own tribute.

George Guest became a legend in his own lifetime. Obituaries in newspapers and journals have already paid warm tribute to his achievements: to his vision in saving and in building up the choir at StJohn’s College, Cambridge, in the lean years which followed World War II and in making his choir into one of the most famous and well respected in the world.

I had the good fortune to be a student in Cambridge in the late 1960s and early ’70s: years when, aided by the accessibility which came through the emergence of recording, the ‘John’s sound’ was beginning to assert itself (Stephen Cleobury was Organ Scholar at the time). The warm and projected treble singing, the full-bodied sound of the choral scholars and the colourful and (for England) novel use of gentle vibrato, all combined to provide a distinctive choral style, far removed from what we were used to hearing when visiting other English choral

foundations. The ‘Continental style’ was often used as a description of the sound of the John’s boys but, even if it owed something to the Vienna Boys’ Choir (the only overseas boys’ choir generally known in England at that time), it was nevertheless totally personal: it was George Guest’s own style; and how glorious it was - admirably suited to the acoustics of the chapel. Complementing this was an interesting and explorative repertoire of music, opening up new horizons for those nurtured on the traditional Anglican diet of English composers.

George Guest’s personality and his faith shone through his music-making. That he could be a hard task-master was never in doubt; but his vibrant personality, his love of and conviction for the music which he was performing and his dry sense of humour endeared him not only to his choir but to all who came into contact with him or who admired him from the touchlines.

perfect blend, and occasionally of balance and even ensemble. What was extraordinary was that it also allowed George’s own feelings to fire the imagination of his singers, to create performances of enormous emotional fervour and excitement. Carefully rehearsed tempi and dynamics would be forgotten as George rose up on his toes, powerfully communicating his passion through his unconventional arm gestures and perhaps more importantly through his eyes, which willed boys and men to give every last ounce of themselves and more. Equally dramatically, I remember a stunningly magical, perfectly controlled ppp start to the Sunday morning introit, Messiaen’s O sacrum convivium, in a crowded yet totally silent chapel.

It was a very fortunate moment for the FCM when, following the death of Sir Charles Groves, George Guest accepted the invitation to serve as our president. Typically, he did not regard this position simply as an honorary one. He was not prepared only to lend his name and reputation as a figurehead: he became actively involved in FCM affairs, attending and from time to time chairing annual general meetings and meetings of the Council and - much appreciated by the membership- frequently attending our regular gatherings, getting to know the members and always ready to make a speech or to give a vote of thanks as the occasion demanded.

Part of George Guest’s greatness was his loyalty to St John’s College and his length of service there as organist. St John’s became his vision and his life: the world of church music is all the richer for what he achieved there and for what he taught us, whether as students, singers or performers, or simply as listeners.

The FCM is proud that, in his retirement, Dr Guest became associated with us as our president and grateful that he did so much to further our work. We send to George’s wife Nan, and to their family, our condolences in their bereavement, together with our great appreciation of all that George achieved and all that he gave to generations of lovers of choral music. He will be sadly missed.

His single-minded devotion to his choir gave him the dogged energy to reorganise the choir school, appoint and train 40 years’ worth of choristers and organ and choral scholars, chase recording contracts and organise ambitious choir tours to many parts of the world. It also resulted in the highest musical standards. But it tended to embrace a lack of compromise and barely-concealed disdain for some university colleagues and members of the clergy who did not share his priorities. Moreover it led to an apparent loss of personal direction when he retired.

George was proud that undergraduates searching for religious experience were not all drawn to the triteness of the happy-clappy student Christian Unions. In his autobiography A Guest at Cambridge (Paraclete Press, 1994) he wrote: ‘... young people resent being patronised, and my experience at Cambridge has convinced me that there is a most definite reaction on the part of young people to the trivial in worship. In an ever-changing and often frightening world they look increasingly for dignity, for tradition.’ His work lives on through his recordings and pupils. It is particularly appropriate that his memorial service is to be held in St John’s Chapel. This is, after all, the building that he loved and in which he trained us all. Perhaps the greatest compliment to his work was the appointment in 1991, as his successor, of another of the country’s finest choir trainers, Christopher Robinson, who has, in his own style, ensured that the St John’s Choir remains one of the world’s most admired.

Cathedral Music 12

‘His single-minded devotion to his choir gave him the dogged energy to reorganise the choir school.’

‘John’s sound’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 11

Maintaining a commitment:

From my earliest school days, when I pushed my bicycle across the cathedral close in Hereford (riding your bicycle in the Close being a punishable offence!), I have been attracted to cathedrals. These massive monuments remain in some important sense both worldly and undomesticated. It is not just their size that sets them apart from parish churches. Cathedrals proclaim a generosity of spirit, which still has the power to enchant and to scar the imagination – to disturb and to exalt the human spirit.

At their best they model to society at large a form of ‘koinonia’ or collegiality that is rooted in corporate prayer and service, because they require a small village of individuals to run them: clergy, musicians, singers, craftsmen, vergers, administrators, cleaners, caterers and salespeople. They are inevitably open to the changing traffic of the world as it passes by, and comes in and out. Cathedrals draw people to drop in without commitment – to wonder and to explore. Cathedrals are vast buildings – and are expensive to maintain – but we keep them open because in their counter-cultural size and unusable space, they represent values which have not been finally lost and which people still hope will somehow be regained in nurturing the religious life of the nation.

Rochester Cathedral is set on the Pilgrim Way – the old road that led to Canterbury and, beyond that, to Rome and the Holy Land. Chaucer walked it; people still do today. But Rochester was a place of pilgrimage in its own right as well. In about 1201, William, a baker from Perth, was murdered just outside the town. Such was his reputation as a devout pilgrim that the townsfolk insisted that he should be brought within the town’s walls and buried in the monastic church. Soon his tomb was said to be a place of miracles, and it became a shrine. People began to flock to it. Today, alas, there is nothing left; it was completely destroyed during the Reformation. But the cathedral is still here, its stones soaked in the prayers of all those pilgrims who have come hererejoicing, or troubled, or sick. Many people still come to the cathedral today with their hopes and fears.

Gone are the days when cathedral clergy could quietly get on with their prayers, their reading, and their care of

Precentor Canon Ralph Godsall on life as the new boy at Rochester Cathedral.

the daily passing traffic of a cathedral precinct. The day-to-day running of cathedral departments and a range of management tasks now predominate. Today cathedral chapters are accountable to all kinds of bodies on all areas of cathedral governance. The involvement of so many others in the day-to-day governance of the cathedral distracts residentiary canons from their primary function as ‘advisers to the bishop and as counsellors in holy things’. Meetings and papers proliferate

The most important function of a cathedral is its offering of daily worship. Other activities – mission, evangelism, teaching, preaching and even the provision of a seat for the bishop – are bound to be of a secondary importance, if we believe that ‘the chief end of man is to glorify God and to worship him for ever.’

One of the glories of Rochester Cathedral is the tradition of sung services, in particular evensong. It is, in its dignified words and

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 12

The issues and challenges for cathedral music at Rochester are complex. The core musical unit consists of a choir made up of 14 boys (four of whom are probationers) and six 1ay clerks, directed by the Organist and Director of Music, who is assisted by a part-time SubOrganist. Girl choristers were also introduced to Rochester seven years ago. There are at present 16 girls (three of whom are probationers) who sing a number of the statutory services as a voluntary choir. Applications for choristerships continue to decline, partly because of Rochester’s close proximity to London and partly because of the choir’s current commitment to sing on six days of the week, including Saturday afternoons.

A generation ago local parents from the lower socio-economic groups saw choristerships as a way of getting a reasonable and cheap education for their sons in return for their singing. Today’s choristers come from the professional classes, and despite the best efforts of the Chapter to obtain sponsorship for one hundred per cent scholarships for boys from lower socio-economic groups it is proving difficult to find boys from such backgrounds, possibly because of the requirement that they must attend the cathedral choir school. In conversation with other cathedral precentors, it has been interesting to learn that cathedrals without schools, which have to recruit without the incentive of choral scholarships, are finding it easier to recruit across the social spectrum.

Interestingly, the recruitment of girl choristers is far easier, possibly because they are not required to attend the cathedral choir school.

Both systems give the singing boys and girls great opportunities, and one of the most welcome recent developments at Rochester is the way in which cathedral clergy, head teachers and organists are now prepared to share problems and to learn from one another. The addition of girls as members of the core musical unit has presented chapter with financial and administrative problems, but there are many benefits. Girls now participate actively in cathedral worship. They are being given the same educational and musical opportunities as boys. In addition to the benefits to the girls themselves, their inclusion is enabling Rochester Cathedral to provide a wider and more varied programme of musical activities, both in the cathedral and also in the diocese.

The future of cathedral music at Rochester depends on maintaining a commitment within chapter to chorister training and education, and developing the resources necessary to employ skilled and imaginative adult musicians as directors, organists and singers. An immediate and ongoing responsibility of the Precentor is to ensure the level of funding needed to sustain a choir of professional standard to meet a variety of liturgical settings.

Cathedrals increasingly see themselves as complex institutions with a diversity of functions and focuses, and substantial

financial responsibilities and liabilities. The awakening of a management culture, the review recorded in Heritage and Renewal and the consequent institutional reform required by the Cathedrals’ Measure 1999 have effected a move towards a more sharply defined organizational structure, with lines of reporting, teams and departments, and a new pattern of governance and scrutiny with far greater lay involvement. These changes bring to the fore the contrast between the informal understanding of status, protocol and good personal relations on which cathedrals formerly depended, and the new ethos of a wellrun, accountable, efficient, managed organization. With this new ethos comes an expectation of professionalism.

I discern two kinds of professionalism emerging at Rochester: first, a professionalism of administration, financial discipline, management and operation, applicable to every part of the organization; second, a professionalism based on the sharing of skills, experience, knowledge and understanding. These two kinds of professionalism should not separate `administrators’ from `ministers’ (including musicians); rather, a process of planned development and training throughout the organization is encouraging inter-professional respect and understanding.

Nowhere is this more clear than in the new Liturgy and Music Department of the Cathedral. There was no department when I arrived, but there is now a coherent administrative unit operating within an agreed budget within the structure of the cathedral organization. It acknowledges that the work of singers and musicians goes well beyond the functions of singing and playing at divine services, and brings them into a working relationship with vergers and stewards and many other members of the wider cathedral community.

Rochester hopes its Precentor will sing like an angel, balance liturgical expertise and musical training in equal measure, be a good communicator, be skilled in administration and management, and be able to retain a sense of humour and proportion at all times! The new Precentor at Rochester is not a trained musician. However, he can understand the needs of the musicians, relate to their concerns, and effect good communication. It is one of the most important working relationships within the cathedral. Such a healthy relationship helps to produce a climate marked by creativity, integrity and trust.

Cathedral Music 14

‘Rochester hopes its Precentor will sing like an angel, balance liturgical expertise and musical training in equal measure.’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 13

Photo courtesy of Medway Council.

Robert Quinney, winner of the 2002 RCO Performer of the Year competition and Philip Scriven, Organist and Master of Choristers at Lichfield Cathedral, discuss the competition and the future of cathedral music in the Church today.

Shaping up for the Future

PS Robert, congratulations on your recent success with the RCO Performer of the Year competition. How do you think this will affect the course of your career?

RQ It has certainly already raised my profile as a player, and a number of recital engagements have come in as a direct result of the competition. I have been keen for a while to do more solo performing, so the competition success was timely in that respect.

PS How do you see your career developing?

RQ I think there’s room within the general context of cathedral and collegiate music for a wide variety of activities, of which solo organ playing is one. I’m very fortunate to be Assistant Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral, a post which is both demanding and relatively flexible. One aspect of my career that there isn’t really much time to develop at the moment is the academic side, something I hope I can rekindle at a later stage.

PS Do you think it is possible in today's competitive climate to make a name for yourself today without winning a big competition?

RQ It’s difficult to ‘kick-start’ a career without a competition success of some sort. The prestige of a cathedral post is no longer enough to guarantee a steady stream of recitals – if indeed it ever was. Recital series organisers are (for obvious reasons) not keen on asking untried players, whether they have a church position or not, and the shady business by

which organists reciprocate each other’s invitations is perhaps not as widespread as it used to be. It is, however, a shame that series often end up presenting the same few very well established organists and, consequently, a narrower variety of music than would be the case if the net were cast a little wider.

PS What areas of the repertoire do you specialise in?

RQ My first love is the music of Bach, in which I have an academic as well as a performing interest. Bach’s organ music is one of the most extraordinary oeuvres of any composer: in many ways it’s quite different from the rest of his output, and the brilliant integration of different genres and styles in the organ music fascinates me. In the organ music we meet Bach face to face, as he was an organ virtuoso himself, and I think there is bound to be something special – more private, perhaps – in the music a composer writes for his own instrument. As well as Bach my interests encompass British keyboard music of the 16th, early 17th and late 20th (and early 21st!) centuries: in the latter category is Francis Pott’s monumental Passion Symphony Christus, a demanding (in that it lasts twoand-a-quarter hours) but totally compelling work which, sadly, I have played only once, as it doesn’t fit into a typical recital programme! I’m also very fond of the music of Jehan Alain and, increasingly, Reger.

PS What do you think of the current trends in organ performance, such as the growth of interest in improvisation in this

country, and the increasing popularity of transcriptions?

RQ Improvisation has become popular over the last few years. Concert improvisations feature more in programmes of British players than they used to, under the influence of French organists. Just as exciting, however, is liturgical improvisation, which is, of course, the source of the European improvisation traditions. I find myself doing quite a lot of it at Westminster Cathedral: the Catholic liturgy is perhaps more open to improvisation and Martin Baker, himself a virtuoso improviser, has instituted a number of improvisation ‘points’ in both Mass and Vespers. Thomas Trotter has for some years been largely responsible for a revived interest in transcriptions. This can only be a good thing: the playing of orchestral transcriptions strengthens the organ’s connection with the wider musical world; it provides a better choice of repertoire for the organist – very little transcribed music is of a low quality, while rather a lot of ‘straight’ organ music is; and it capitalises on the strengths of the 19th and early 20th century British organ –variety of tone colour, power and ease of operation.

PS Organ music still suffers from a poor image in the wider musical scene. What do you think organists can do to improve the way the instrument and its repertoire are viewed?

RQ Four things occur to me. Firstly, concert halls should have good organs on which regular recitals are given – as at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and ➤

Cathedral Music 15

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 14

Robert Quinney

the Bridgewater Hall in Manchester – this is an important step towards establishing the organ as a solo instrument in its own right. Secondly, organists have a responsibility to play good music that engages with the audience – there is no excuse for playing bad music, yet it features in so many recital programmes! Thirdly, I find it helps to speak to the audience, especially in a situation where the player can’t be seen. Of course it’s rare that a concert pianist or a member of a string quartet address the audience, but they don’t have the dual problems of an instrument that mitigates against direct communication and a repertoire that can seem arcane if no explanation is offered. Finally, it is essential that some organists pursue concert careers independently of the Church. I’m not planning on doing this myself, because my interests lie in a number of areas including church music, but it is important that opportunities are given for artists like Gillian Weir, to take the most notable example, to continue their promotion of the organ and its repertoire uncompromised by other commitments.

PS Could you tell us a bit about your work at Westminster Cathedral? What does it entail, and what would you say makes the music there so distinctive?

RQ I accompany the choir, conduct two or three times a week, and discharge a number of administrative duties, including organising the Sunday afternoon recital series (in which I give most of the concerts), booking singers for ad hoc services, recordings, etc., and maintaining the choir library. Westminster Cathedral’s music differs in many respects from that of its Anglican counterparts. For a start, our daily choral liturgy is Mass, not Evensong (we do sing the office of Vespers every day, just before Mass, but it only lasts about fifteen minutes and is sung mostly to chant). Because of this we have a much bigger repertoire of masses than Anglican choirs, most of them drawn from the Renaissance, and it’s from that period that most of our motets come as well. This affects the way the choir sings (pure Italianate vowels lend themselves much better to musical line than English diphthongs and consonants!), as does the large amount of melismatic chant we sing – on average three plainsong propers in each mass. The choir stands not in an enclosed ‘quire’, but almost out of sight in the Apse, a half-domed area behind the high altar: the distance from the congregation encourages well-projected, open-throated singing, and the acoustical properties of the Apse are much more generous to voices than the average Quire. From an organist’s point of view, it’s perhaps a shame

Cathedral Music 16

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 15

‘The sorry state of music in, for example, many of the French and Spanish cathedrals should convince us of the need to defend our own traditions while they are still flourishing.’

that so little of the repertoire is accompanied, but we have the consolation of the Grand Organ, which stands on the West wall, and from which most of the voluntaries and all the recitals are played. Built by Henry Willis III between 1922 and ’32, it is the finest solo instrument I have played, and working at it is a daily pleasure.

PS There is plenty of debate about the future of cathedral music. How do you see it shaping up?

RQ There always has been, and ought always to be space for an elite group of musicians in a great Christian building –even in the earliest days of the monastic foundations there were designated musicians among the monks, and song has always been integral to worship. Music also has an essential role to play in the edification of the faithful, and good music is naturally better able to do this than bad (and it’s worth asserting in passing that musicians are uniquely, if not exclusively, qualified to make value judgements over music). The sorry state of music in, for example, many of the French and Spanish cathedrals should convince us of the need to defend our own traditions while they are still flourishing. The daily opus of sung worship is an invaluable link with our past, as steadying influence in a hectic and violent world. In doing this, however, we must be alive to changing times, and must not fall into the trap of regarding change as anathema to tradition. I suspect, for example, that the service of Evensong needs careful consideration – does it actually work on anything but a musical level? Now that daily Evensong has developed into a much more grandiose event than was almost certainly intended by its designers, the idea of simply reciting the office in straightforward rotation of psalms and readings perhaps needs rethinking, as does the balance between the form and function of musical settings.

PS With the ever increasing pressure of recruitment, what do you think are the most beneficial aspects of a chorister’s experience that we need to emphasise?

RQ The educational value of choristerships is perhaps the strongest selling point for cathedral choirs: there is no better way for a musician to start his or her training, and even children who don’t end up as musicians benefit enormously from four or five years of dedicated team-work and the daily challenge of preparing and performing music.

PS Westminster Cathedral has commissioned works from a number of notable composers recently. Which do you think are the most important composers writing church music today, and which really have something original to say?

RQ At the present time there is an important distinction to be made between church musicians who occasionally write music for their choirs, and who are therefore concerned mostly with producing functional pieces that suit particular occasions and particular

produce the best music, because the musical world is quite strictly demarcated – we’re not really expected to be interested in composing, let alone be any good at it! It is rare, therefore, to find a composer like Philip Moore, whose music is conceived out of and for a liturgical tradition but is of an exceptionally high quality by anyone’s standards.

people, and composers such as Peter Maxwell Davies and James MacMillan, both of whom have recently written Masses for Westminster Cathedral Choir. These latter are the musicians who ‘really have something original to say’, because their masses are products of broad influence and wide experience, and they come to the texts with a freshness that those of us who hear ‘Kyrie eleison’ or, for that matter, ‘My soul doth magnify the Lord’ every day are unable to muster. The essential difference is that, these days, we rely on professional composers rather than generalists like you and me to

Maxwell Davies is an interesting case, because he is both strongly antiecclesiastical (he is an atheist) and deeply respectful of church music traditions, as well as being an incisive commentator on contemporary social issues. His mass, which makes extensive use of the antiphon Dum complerentur dies Pentecostes and the hymn Veni creator, seems to me a profoundly humanistic response to the mass text – a celebration of song as an experience shared with the length and breadth of humanity (hence the two plainsong themes) – which also pays respect to liturgical tradition and works tremendously well as a festal mass setting. It’s certainly not a concert setting of a liturgical text like Poulenc’s Gloria MacMillan’s Mass seems in some ways remarkably similar in outlook to Maxwell Davies’, though the composers have quite different beliefs and write very different music. Both masses are underscored with a dark quality, an equivocating presence which refuses to allow words like ‘dona nobis pacem’ to resolve into an idealised evocation of peace. Great artists make statements which they might not recognise as their own, because they act as ciphers for contemporary society in its widest sense. We should be suspicious of any mainstream composer who attempts a ‘straightforward’ setting of texts like the Gloria and Agnus Dei, given the complex and uncomfortable relationship we are all bound to have with God in a largely secular age. The ‘spirituality’ practised by certain contemporary composers has more to do with New Age-style escapism than the challenges of Christian belief. I think it’s very important that composers within the mainstream continue to write music for the Church: however, unlike Stanford and Parry (both of whom were international musical figures who certainly didn’t regard themselves as ‘church music composers’) modern composers will not write religious music unless they receive commissions to do so, for the simple reason that religious observance is no longer an integral part of most people’s lives.

PS Robert, thank-you for sharing your thoughts on these important issues and best wishes for your forthcoming recitals.

Cathedral Music 17

‘Which do you think are the most important composers writing church music today, and which really have something original to say?’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (3-17) 1/4/03 6:53 PM Page 16

Philip Scriven

The Lay Clerks Tale

The Apocrypha has it that a certain church musician, mindful of Ripon’s modest standing as a city (in England playing minor only to Wells’s minimus) enquired of one chorister parent as to where it might be possible to find lay clerks for the choir. “Well – er…” (came the reply) “… usually in the One Eyed Rat!”

Uniquely the Book of Common Prayer –after the Ripon use – continues the evening office beyond 2 Corinthians 13 and into premises located on Allhallowgate (some five minutes’ walk from the Cathedral and by repute only three minutes back) dedicated to a little known deity rejoicing in the name of

Harry Winter, a tenor lay clerk at Ripon Cathedral joins his colleagues regularly at the One Eyed Rat in Allhallowgate.

‘One Eyed Rat’ (but originally to ‘Lord Nelson’ – hence the one eye). Here gather the lay clerks to slake their thirsts after the nightly tussle with Gibbons, Stanford, Howells, Bryden et al, and to set the world to rights. Available to them is a wide and constantly changing variety of real ales, fruit wines and Continental bottled biers which makes this pub unequivocally the best in the city. There is a fine garden to enjoy on sunny Sunday afternoons and also in May an annual German Bier Festival, at which times it has been noted with some relish that the Schlelkerla Rauch and Erdinger Wiesse available at the one end of the bar are amply counterbalanced by the Shepherd Neame Spitfire and Mitchell’s Lancaster Bomber at the other!

Illustrated is a fine gathering of the

George Sixsmith &Son Ltd Organ Builders

chaps (including acting organist Andrew Bryden) following evensong on Tuesday January 21st, which featured renditions of Purcell in Bb and Expectans Expectavi (of Charles Wood). In the best of traditions antiphonal insults were exchanged (interestingly the photograph has divided exactly between Cantoris and Decani with the camera, as it were, at the altar) however even the least able among us may celebrate the pub’s motto:

‘In the land of blind mice

The One Eyed Rat is king!’

It is recommended that visiting choirs should avail themselves of this facility and also any passing waifs or strays with an interest in cathedral music should make a point of joining us on Evensong evenings in term at the witching hour of about 6.30pm.

My Spirit Rejoiceth

Directed by Richard Tanner

Organist: Greg Morris

Settings of the Magnificat

The organs of Douai Abbey played by Terence Charlston including Toccata and Fugue D mi Pedalexercitum G mi Fantasia and Fugue G mi Prelude. Trio and Fugue C maj

Pastorella in F maj Fantasia in G maj

Cathedral Music 18

In this new series we go round the country visiting lay clerks’ favourite watering holes.

We provide all types of new instruments New Organs Restoration Rebuilding Tuning Maintenance We can give unbiased advice for all your requirements Hillside Organ Works Carrhill Road, Mossley Lancashire OL5 0SE Tel: 01457 833 009 Fax: 01457 835 439

CHOIR BLACKBURN CATHEDRAL GIRLS’ CHOIR RENAISSANCE SINGERS

BLACKBURN CATHEDRAL

OF BLACKBURN CATHEDRAL

OUNDSOF

and Nunc Dimittis by Smart, Lloyd, Watson, Read, Brewer, Ashfield, Tavener and Howells S

B ACH

Lammas RECORDS CHORALAND ORGAN MUSICOF DISTIINCTION Order direct from: Lammas Records 34 Carlisle Avenue, St. Albans, Herts. AL3 5LU Tel/Fax: 01727 851553 E-mail: enquiries@lammas.co.uk www.lammas.co.uk Distributed by: Discovery Records Tel: 01380 728000 Fax: 01380 722244 Griffin and Company Ltd Tel: 01524 844399 Fax: 01524 844335 LAMM 131D LAMM 150D

&

Send for our latest catalogue and offers Ripon lay clerks enjoying a pint or two. Cathedral Music APR 03 (18-33) 2/4/03 9:21 AM Page 1

CDs price £13.99 each including p

p

Cathedral Music 19

Where do lay clerks hang out in your part of the country? If your local hostelry is worth a mention drop the editor a line along with a photo of the lay clerks partaking in a pint.

‘...where it might be possible to find lay clerks for the choir. “Well – er…” (came the reply)

“… usually in the One Eyed Rat!”’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (18-33) 2/4/03 9:21 AM Page 2

Photos by Graham Hermon.

Canterbury Gospels: The

Twelve-year old Canterbury Cathedral Chorister Michael Hawkes describes the excitement and preparation of the Enthronement of the 104 Archbishop of Canterbury

Question: Was it worth the hours of practice beforehand? (Our halfterm holiday had to be moved to enable us to be at the cathedral for the enthronement, therefore disrupting our attendance at school; We practised the same pieces for hours; The cathedral was turned into an ugly film set full of scaffolding and television lights.)

Answer: Definitely!!

As the day of the enthronement got closer and closer mixed feelings of worry and excitement built up in the Precincts. Policemen and sniffer-dogs patrolling around nearby houses and dustbins and the windows of the cathedral being sealed, an alarm put in the practice room and BBC lorries parking outside the cathedral added to the tension.

A newly commissioned piece and lots of pieces new to our eyes were sight-read by us; chairs appeared all over the cathedral; cameras peeked over walls; familiar faces from the cathedral appeared on the television.

enthronement of Dr Rowan Williams

The great day dawned bright and fair –The Dean will have been mightily relieved; the only thing worse than a worried dean is a wet worried dean! To our surprise, the morning singing practice was mercifully relaxed and shorter than we expected! It seemed that everything was on track for a successful day!

The enthronement itself was very exciting. As we processed in it suddenly dawned upon us that this was the ‘Big One’ – the most magnificent and important service in our (or any chorister’s) career. (Although we did have the Royal Maundy last year!) Benches of Bishops, clusters of Canons, vast hordes of vicars –everyone who was anyone was there... or so it seemed. We saw Prince Charles and the Lord Lieutenant of Kent, representing the Queen. Tony Blair was there as well as many other politicians, including the Lord Chancellor and the Speaker of the House of Commons. The Anglican Primates, representatives from all other Christian denominations and other religions processed past us; there were Anglicans, Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jews, Hindus, and probably Muslims too. We at last realised just how important throughout the world our Archbishop is.

Dr. Rowan Williams, resplendent in gold cope and mitre, Welsh and English dragons facing one another across his chest, made a dramatic entrance to his cathedral, after hammering three times on the door as we sang Jubilate Deo

The congregation of 2,300 had waited excitedly for this moment and their delight at seeing him was obvious.

The Archbishop was welcomed, the Mandate for his enthronement having been read, he was enthroned twice, once as Archbishop of this diocese and once as Primate of all England. He was given three seats: St. Augustine’s throne, the Cathedra in the Quire and the Prior’s seat in the Chapter House.

All the choristers enjoyed the enthronement hugely, as everything went smoothly, and it was a great experience to be singing on television and in front of such a huge congregation. We enjoyed all the pieces we sang, especially the Festival Te Deum by Benjamin Britten, in which Joe Rawlins starred with a two page long solo. We all thought that Frititi (the African singers and dancers from Brixton) were amazing and it was hard for all the choristers to keep still! (Apparently the choir probationers, in the congregation, couldn’t keep still!)

As we were processing back to St. Andrew’s chapel after the Foundation Ceremony in the Chapter House, we experienced something new, our first ever round of applause in a service, rather than a concert! We noted that most of the people applauding were clergy!

The enthronement will be an experience that none of us choristers will ever forget! (When we are old men we can bore our grandchildren about it!!)

Cathedral Music 20

‘...the only thing worse than a worried dean is a wet worried dean!’

Cathedral Music APR 03 (18-33) 2/4/03 9:21 AM Page 3

Micheal Hawkes is the chorister top left. Photography David Manners.

Recruit a Friend Programme

MUSIC

Theenthronement of an Archbishop is an event which we in Canterbury Cathedral both enjoy and dread at the same time. It is a fabulous occasion, under the eyes and ears of the whole Anglican Communion worldwide. It is a wonderful opportunity to welcome so many guests from home and abroad; a fantastic festival day, but for the Cathedral staff a long period of intense preparation.

For the musicians, a considerable amount depends, of course, on the wishes of the Archbishop himself; on the elements which he particularly wants to have included in his most special and daunting occasion. Then, through much pondering and discussion, a programme of music is devised which, we hope, covers as many of the wishes and requirements as we can.