The Sibthorpe Circle brings together and recognises the support of all generous individuals who are leaving a gift to Cathedral Music Trust in their Will. The Circle is named after our Founder, Revd Ronald Sibthorp, in honour of the far-reaching impact of legacy gifts.

Cathedral Music Trust would like to acknowledge and thank the Gold and Jubilate Patrons for their generous commitment and support of its work.

JUBILATE PATRONS JUBILATE PATRONS

Richard Creed

Jonathan Macdonald

Michael Antcliff

Marcia Babington

Revd Sarah Bourne

David Bridges

Michael Cooke

Eric Merton Cox

Stephen Crookes

Robert Frier

Rodney and Clarendon

Gritten

Julian Hardwick

Edward and Rosemary

Hart

Sheila Kemp

Dr James Lancelot

Robin Lee

Jonathan Macdonald

Roddie and Kate MacLean

Tom Hoffman MBE

Iain Nisbet

Martin Owen

John Pettifer

Denis Roberts

David and Margaret Williamson

And several anonymous supporters

Julian Hardwick

Christine Kilmister

Richard Moyse

Iain Nisbet

GOLD PATRONS

Anthony Biddle

Margaret Davis OBE

Richard Gabbertas

Jason Groves

Simon Hyslop

John Meyrick-Thomas

Nicholas Parry

Professor John Penniston

Gavin Ralston

For more information about supporting Cathedral Music Trust, please contact Victoria McDougall. Thank you for your support.

Graham Robinson

Katherine Powell Rolph

Philip Shirtcliff

Joyce Smith

Dr Christopher White

Susan Williams

John Wilsher

Anne Wilson

Michael Wilson

Instagram @cathedralmusictrust

YouTube CathedralMusicTrust

CATHEDRAL MUSIC MAGAZINE

Editor Adrian Horsewood editor@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Designer Jo Craig

Production Manager Kyri Apostolou

Cathedral Music is published for Cathedral Music Trust by Mark Allen Group twice a year, in May and November.

Spring 2024

parish church, or started playing the organ for services for a came later in life, when you entered a cathedral out of curiosity and

My introduction came in Year 9 at boarding school, when the choir director decided he could hear some potential in my audition. Having

However it happened, for most of us there will have been an initial determined that these sorts of life-changing experiences should be , which will

We also dive into the world of organ restoration in this issue, with tragedy, but both executed with the highest levels of expertise and great love and care. While the rebuild by Harrison & Harrison of the Hill, Norman and Beard organ in Norwich Cathedral took two years, put into words; similarly, the joy that will be felt in Paris when their instrument returns later this year will, I imagine, be incalculable.

Adrian HorsewoodErratum: In the review of David Baker’s Geoffrey Tristram: A Very British Organist in the Autumn 2023 issue, our reviewer wrote that the tracks on the accompanying CD were played by Ted O’Hare; in fact, they were recorded by Geoffrey Tristram himself, and were recovered by his son Michael from reel-to-reel tapes originally made in the 1970s.

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Cathedral Music Trust.

Advertisements are printed in good faith, and their inclusion does not imply endorsement by the Trust; all communications regarding advertising should be addressed to info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk.

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used; we apologise for any mistakes we have made. The Editor will be glad to correct any omissions.

Front cover: Local primary school children singing in Portsmouth Cathedral

(Photo: Mike Cooter)

Back cover: The Cymbelstern on the recently refurbished organ of Norwich Cathedral

(Photo: Press Association)

Editor’s photo: Andrew Wilkinson

6 Securing a musical future for all

Cathedral Music Trust has launched a strategic plan that renews the focus on its mission: to support cathedral and church music in its many guises, to nurture young musicians at the various stages of their journey, and to increase the long-term stability of the cathedral music sector

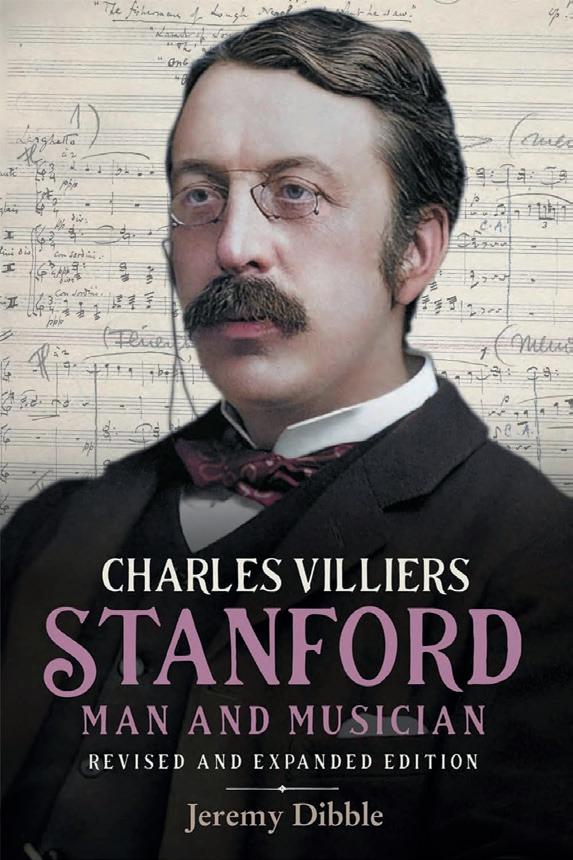

2024 marks the centenary of the death of Charles Villiers Stanford; Jeremy Dibble examines how his church music drew inspiration from other genres

Five years on from the devestating fire, Notre-Dame de Paris is close to reopening; Pierre Dubois reports on the work to restore the historic organ

3

Sheffield

Adrian Horsewood welcomes you to this new issue

12

Catch up with the latest developments in the world of cathedral and church music

21

We offer congratulations to musicians and other figures who are on the move

23

Cathedral Music Trust organises and hosts events for enthusiasts at locations all over the country

24

Learn how cathedral and church choirs have benefited from Cathedral Music Trust’s investment

48

51

Our writers sample some of the newest choral and organ recordings, as well as recent books

66 Q&A

One of Cathedral Music Trust’s team of Future Leaders, Elizabeth Leather, recalls her musical upbringing and formative experiences, and how she sees her role in nurturing the musicians of the future 40 Finding their voice

The organ of Norwich Cathedral has recently emerged from a two-year complete rebuilding and reorganisation by Harrison & Harrison

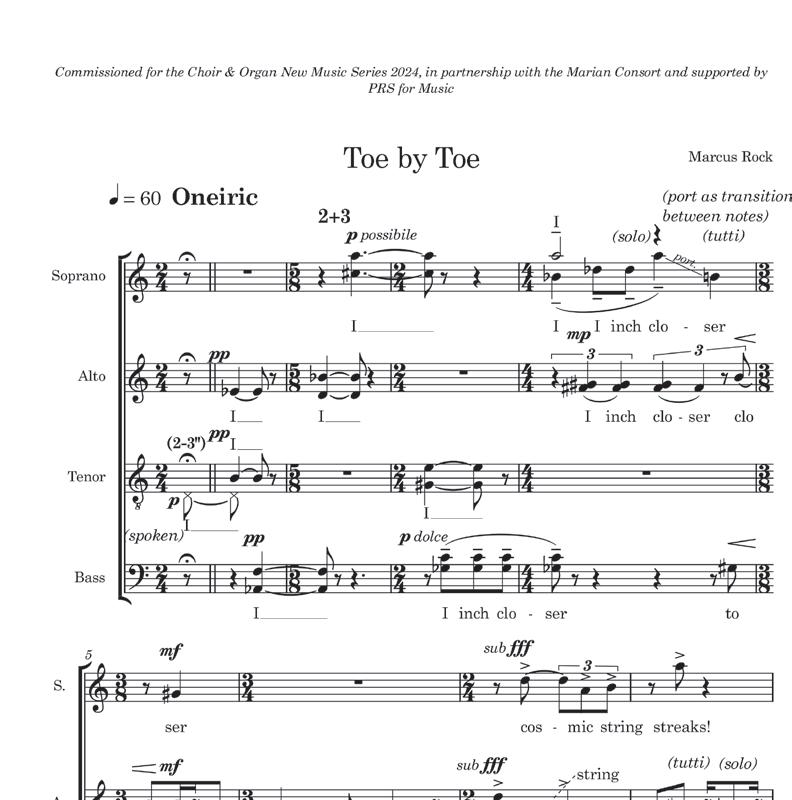

Marcus Rock discusses his work for unaccompanied choir, Toe by Toe

Cathedral Music Trust’s new strategic plan renews the focus on its mission: to support cathedral and church music in its many guises, to nurture young musicians at the various stages of their journey, and to increase the long-term sustainability of the cathedral music sector

By CLARE STEVENSWriting this article in the month that actor, Classic FM presenter and former cathedral chorister Alexander Armstrong undertook a Choral Adventure down the length of Britain on behalf of Cathedral Music Trust, I find it hard to believe that the Trust has existed in its present form for only four years. Since its evolution from the Friends of Cathedral Music (FCM) the Trust has established a strong new identity and become a dynamic presence in the church music scene, building on the success of previous generations who

worked so tirelessly to celebrate liturgical music and provide financial support for cathedral and collegiate music foundations. (And for some parish churches too, but more of that later.)

Cathedral Music Trust has now embarked upon implementing its five-year strategic plan for 2024–29, Transforming Lives through the Power of Cathedral Music, a blueprint for addressing the challenges that face this sector now and into the future, launched last autumn. The plan outlines the Trust’s mission to transform lives through the power of

‘For cathedral music to survive, it is vital that people from all walks of life have the opportunity to be involved’

cathedral music; its vision of a world where people from all walks of life have the opportunity to benefit from a high-quality, well-resourced and valued cathedral music scene which enriches our choral tradition for years to come; and its objectives, which are to support excellence, broaden participation and ensure the long-term sustainability of the cathedral music sector.

Asked how the strategy evolved and how it represents a difference from how FCM worked in the past, Jonathan Macdonald, who has been Chair of the Trust since February 2023, begins by paying tribute to his distinguished predecessors who have led the organisation in the past, right back to the Revd Ronald Sibthorp, Precentor of Truro Cathedral, who founded FCM in 1956.

Back then, Macdonald reminds me, ‘following the Second World War … cathedral music was in a general state of decline. In many cases choirs, and particularly choristers, had been relocated, back rows had been called away to war and had not returned or been replaced, and funding to support the rebuilding of music departments was in short supply.

‘FCM began raising money and awarding small grants, meeting regularly to celebrate and enjoy choral services in cathedrals around the UK.’

Macdonald continues, ‘While cathedral music departments began to flourish once more, the challenge of funding has never really gone away. A few years ago, seeing the opportunity to increase the impact the organisation was having, my predecessor Peter Allwood and his fellow trustees started thinking about bolstering the charity’s resources in order to reach wider audiences and grow support for its mission.’

This led to the establishment of Cathedral Music Trust. In 2019 James Mustard, the current Precentor of Exeter Cathedral, volunteered to represent the Precentors’ Conference on the board of trustees of FCM.

He recalls how, soon after he first became involved, ‘We decided to move towards becoming a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO). This enabled the new organisation to implement best practice governance and take strategic decisions

much more quickly. I was part of all that process from the outset, and it has been incredibly rewarding.

‘The move to becoming a CIO coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic,’ Mustard adds, ‘and thank goodness it did, because it gave us the agility to respond to that difficult situation very rapidly.

‘I’m incredibly proud of what the Trust achieved in the pandemic, collaborating with the Ouseley Church Music Trust and the Choir Schools’ Association and succeeding in getting the £1m we raised to be matched by the Church Commissioners.’

Jonathan Macdonald also feels that the pandemic was a catalyst for much-needed change. ‘It accelerated discussions that were already taking place around the squeeze in funding faced by many cathedral music departments,’ he says, ‘and increased our conviction of the need to broaden our approach. We started by employing a team of experienced staff, creating an engaging website and new branding, and raising public awareness through social media campaigns.’

The next step was to commission two major pieces of research from More Partnership, a leading UK arts consultancy. ‘We asked More to conduct a review into the key issues facing cathedral music in the UK and to recommend how the Trust should focus its work to help address them,’ explains Macdonald.

‘We initially held a workshop at Southwark Cathedral with key stakeholders from across the sector, including members of the clergy, directors of music, cathedral administrators and education leaders. As the project developed over a period of nine months, more than a hundred individuals from across the country were interviewed. The final report, A Future for Cathedral Music, was published in September 2022.’

The More Partnership research identified three central elements that are important individually and together form a powerful set of interlinked factors that need to be balanced to secure the tradition of cathedral music: Excellence, Participation and Sustainability. These three topics form the key pillars of the Trust’s new five-year strategy.

The first pillar, Macdonald explains, focuses on the need to support excellence. ‘We recognise and champion the many strands of excellence that are woven into the fabric of cathedral music departments across the length and breadth of the country.

‘This isn’t just about world-class singing or organ playing. It’s also about ensuring the availability of high-quality training for children and young people, inspiring community engagement programmes, inclusive recruitment practices and protecting the welfare of cathedral musicians and staff.’

The second pillar is focused on broadening participation. ‘For cathedral music to survive, it is vital that people from all walks of life have the opportunity to be involved. Our job is to help choral foundations expand pathways that make it easier for young people to take part. An important part of this is raising awareness of the joy and lifeenhancing benefits that cathedral music can bring to people from all walks of life.

‘And finally the third pillar addresses the need to promote the sustainability of cathedral music. Here we are not just referring to financial sustainability but also ensuring a healthy pipeline of young talent, the flow of which is under significant threat due to the uneven state of music education in our country.

‘While Cathedral Music Trust will continue to offer meaningful financial support, it is essential that we help to address the underlying problem of underfunding, rather than just provide an annual sticking plaster. This means promoting activities that are

‘Our job is to help choral foundations expand pathways that make it easier for young people to take part’

likely to attract more funding over time through increased community awareness and engagement.

‘We are also playing our part in lobbying policy-makers and education leaders to place greater stress on the importance of a basic music education.’

Cathedral Music Trust’s Programmes Director Cathryn Dew is leading the charity’s work on education and participation, in particular the Early Years programme which is set to launch this year. ‘The pandemic highlighted that children were getting less early experience of music, and we want to try and address that,’ she says. ‘Research suggests that music-making and creativity in the early years is fundamental to children’s personal, social and creative development, and so by working with young children and their families, empowering their families to continue making music at home, and experiencing what music in a cathedral can be like, we’re sowing seeds for the future. Whether those seeds blossom into choristerships, or whether they take the children in completely different directions is almost less important than that the seeds are there and that the children begin to develop creatively. We’ve really begun to appreciate the need for and the value of that.’

James Mustard concurs: ‘I’m about to be fifty, and my way into music was that I had a recorder put into my hand; it cost about fifty pence but it was an absolutely invaluable way [to start learning]. That’s not happening now. Music might technically remain a statutory part of the National Curriculum but it’s been very much downgraded in terms of priority

and that’s a massive challenge for cathedrals. Some are really trying to tackle the problem … Southwell Minster, for example, with its crèches, and Sheffield … here in Exeter, we have a Saturday morning children’s choir that helps to provide our pipeline.’

At the other end of the chorister journey, the gap in provision for ‘retired’ choristers of many cathedrals was highlighted by the research.

‘We sometimes lose touch with our ex-choristers because there isn’t an offer for them,’ says Dew. ‘But this is beginning to change, and we want to do what we can to help, because it is important. Where do the future back rows and choral scholars come from?

‘We want to address the issues around what happens to choristers when they finish, but also to engage teenagers who might not have had the opportunity to sing as choristers but have an enthusiasm for the music – or don’t even know they have an enthusiasm for the music yet, but would do if they knew it – and give them a chance to develop the skills that they need, so that they might be in a position to audition for choral scholarships or to sing for the rest of their lives.

‘We need to be careful not to exclude sopranos in that; the focus tends to be on altos, tenors and basses, but a few cathedrals

are looking at developing soprano choral scholars as well, and I think that’s a move we want to help support. We’re right at the beginning and we’ve got lots of ideas that need to be formulated.’

A recent recruit to the board of Cathedral Music Trust is Simon Toyne, Executive Director of Music for the David Ross Education Trust, where his role has involved developing a music programme for over 14,500 children in thirty-four state schools in the East Midlands. An experienced choir director and parish church organist who was himself a chorister at Exeter Cathedral, he is well placed to help Cathedral Music Trust implement the new strategy.

He speaks passionately about the contrast in public appreciation of excellence in sport compared to church music: ‘We are sitting here on a remarkable, unique living heritage – that touches lives profoundly, that involves children and young people as active participants – but I don’t think the country at large understands it, or is even aware of it. There’s a really interesting set of statistics about the number of hours a chorister will devote to their education – and they do become world-class – and it’s roughly the same as the training of a young footballer. We need to value choristership in the same way, as a badge of honour for schools and communities.

BELOW Schoolchildren take part in Cathedral Sing, one of Portsmouth Cathedral’s education and outreach projects

‘I think it’s great that there is now a coherent strategy from Cathedral Music Trust, setting out what this remarkable tradition can give not just to the children and young people who are involved, but to society at large.

‘It gives a very clear sense of direction, and of the kind of imaginative, joined-up thinking that we need this sector to bring to the table, so that cathedral music has the same sort of powerful voice as, say, the national portfolio organisations, the youth music organisations, the music hubs and everyone else in the musical world.’

One of the most important aspects of the strategy is supporting the adult workforce of cathedral music foundations, through enhanced training for younger organists and conductors and through assistance with the administrative tasks that take up so much of a director of music’s time.

‘We know that fundamentally it is very simple: where there’s a very good musician, who cares about their art-form and about education, and they are empowered to educate, you get outstanding results,’ says Toyne.

‘There needs to be a cherishing of all who are in this workforce, including parish churches and schools, where so many profound, pivotal, life-changing moments can happen.

‘But we also need to make that a more viable career prospect and to be looking at what the landscape is. Thirty, forty, or fifty years ago it would have been normal for the director of music at a parish church to be director of music at their local school.

Stephen Cleobury and Michael Nicholas, for example, started their careers as directors of music at both St Matthew’s, Northampton and Northampton Grammar School.

‘That has grown to be less common, but that connection between schools and churches or cathedrals is starting to come back, for example with the National Schools Singing Programme and the really imaginative partnerships between cathedrals and schools that have been developed.

‘If you can expand a cathedral music department to recruit really good choral practitioners who are working in schools, you can build a choral foundation that is properly connected to its local community. The result is powerful.

‘We actively need to develop the workforce and it should be a no-brainer that the more young people are engaged in cathedral music, the more opportunities there will be to find

‘Cathedral music provides not only a transformative education for children and young adults but also joy, comfort and wellbeing to countless people, whether they have faith or not’

and train the leaders of the future. There will be a wider talent pool to develop the next generation of the workforce – it’s really simple.’

From the perspective of a residentiary canon, James Mustard also welcomes the focus on professional development.

‘I am very mindful that current assistant directors of music – and to some extent organ scholars – are the directors of music of the future. In the past their training would have been essentially an apprenticeship, learning on the job alongside more experienced organists, which was great if the director of music was someone like Roy Massey, who could inspire and develop protégés such as Timothy Noon, our Director of Music here at Exeter.

‘Perhaps more significantly’, he adds, ‘the terrain of music-making has changed immensely over the last twenty to thirty years, not least with regard to safeguarding, but also with regard to inclusion, in terms of how children’s voices are understood and what is appropriate in terms of training them … So we felt that assistance with training would be very valuable.

‘Our Future Leaders programme will help with all of this, ensuring that younger musicians themselves will have input into how we shape our plans. I’m also aware that the job of running a cathedral music department is vast, and the administrative support directors need is huge, so we aim to help with that too.’

An issue that keeps recurring in our conversations is the enormous variation in the financial circumstances of different foundations and in almost every aspect of how they operate. That is one reason why Cathedral Music Trust aims to use the expertise and availability of its staff as well as its trustees to get to know individual musicians, clergy and administrators better, to walk alongside them and to offer financial support in a more meaningful way.

‘We’re very aware that no two cathedrals are the same, and it’s not for us to tell anyone how to run their cathedral; we’re saying that we’d like to be able to resource them in order

to help them to bring the widest possible number of people in as participants and provide the widest level of professional support in that context.’

The idea of partnership underlies much of the strategy, says Jonathan Macdonald, citing as an example the Trust’s Church Choir Award, which was set up in partnership with the Royal School of Church Music and is now in its third year. Choirs which do not usually qualify for the Trust’s main grant programme may apply for up to £10,000 to fund an innovative or enriching project. ‘We also want to highlight the importance of music-making in parish churches across the country which forms an integral part of our nation’s church music scene.’

Macdonald says that the response to the publication of the strategy has been extremely positive. ‘We have been delighted with the support and buy-in received for our plan from across the sector. To ensure its success our intention is to work ever more closely with cathedral music departments across the UK and Ireland and assist them in whatever way we can to ensure a bright future.

‘We know we can’t fix the problem of underfunding in the sector overnight – or alone – but I am confident this new approach will help us to build the Trust’s financial resources while also broadening and deepening awareness of our mission.’

In conclusion, Macdonald reflects that ‘Cathedral music provides not only a transformative education for children and young adults but also joy, comfort and wellbeing to countless people, whether they have faith or not. The more people that understand this and want to become involved, the more this wonderful living heritage can develop, flourish and be preserved for the benefit of future generations.’

You can read a summary of Cathedral Music Trust’s five-year strategy, a summary of the More Partnership report and its literature review at www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/ publications.

At Cathedral Music Trust we believe that every child should experience the life-transforming benefits of learning to sing.

Our 2024 Small Sounds programme will establish weekly music groups in cathedrals for over 1,500 early years children and their families across the UK, helping them to live happier and healthier lives.

Many children experience barriers accessing music from a young age, provision which has been proven to support personal, musical and social development.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, music provision for very young children has drastically reduced, exacerbated by closures of early years settings and financial barriers facing families. Less than 9% of cathedrals, which are the UK’s centres of choral excellence, offer early years provision.

‘This is a superb opportunity to really grow excellence in singing from an early age,’ said Alexander Binns, Director of Music at Derby

Cathedral, ‘and to build relationships with families so they feel comfortable engaging with music, and feel at home in the cathedral space.’

Weekly cathedral-based music groups will provide high-quality musical experiences and enhance children’s confidence, well-being and personal development – and help them become ready for school. We will equip cathedral music departments and train their musicians to deliver this work on an ongoing basis, enriching lives for years to come.

Cathedral Music Trust’s Director of Programmes, Cathryn Dew, points out that, ‘Making music from

‘Making music from a very young age sets children on a lifelong musical journey’

a very young age helps children meet developmental milestones and sets them on a lifelong musical journey, giving them the skills they need to join a choir. We want to help more children discover the joy of singing!’

Small Sounds was launched in March with an initial funding campaign that saw over £6,600 donated by Trust supporters and members of the public; the Big Give then contributed £5,000 of matched funding. But this is only the beginning of a long-term project.

‘I owe my entire career to my early cathedral music education,’ says Alexander Armstrong, Cathedral Music Trust Ambassador. ‘I urge you to support the Small Sounds project so that more children can be given the lifechanging opportunities that singing offers, now and for years to come.’

For more information about the Small Sounds project, visit the Cathedral Music Trust website at www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

One of the country’s leading music educators and choral conductors, Simon Toyne, has joined Cathedral Music Trust’s board of trustees. He received his musical training as a chorister in Exeter Cathedral Choir, later becoming Organ Scholar of University College, Oxford. Simon was Director of the Tiffin Boys’ Choir for twenty-four years, overseeing over 270 Royal Opera House performances and collaborations with the world’s leading conductors. Since 2012, he has been a Director of the Rodolfus Choral Courses.

Simultaneously serving as Director of Music at All Saints’ Church, Kingston, and Assistant Head & Director of Music at Tiffin School, Simon led choir broadcasts on BBC1, Radio 4, and World Service Radio, with over twenty choristers achieving scholarships to Oxford and Cambridge.

Since 2015, as Executive Director of Music at the David Ross Education Trust (DRET), Simon has developed a music programme for over 14,500 children in thirty-four East Midlands state primary and secondary schools. Notable achievements at DRET include the award-winning Singing Schools programme, trust-wide music curriculum development, and partnerships with leading organisations including Gabrieli Roar and the Royal Opera House.

Contributing to the National Plan for Music Education and Model Music Curriculum, Simon served on the Department for Education’s Expert Panels and is currently a member of the Monitoring Board for the National Plan. His chapter on curriculum music in What Should Schools Teach? (2021) is available from UCL Press. Founder President of the Music Teachers Association, Simon also serves as the Music Director of the Northampton Bach Choir.

Simon commented: ‘I am proud to be joining Cathedral Music Trust at an exciting stage in its journey. The UK’s remarkably rich choral and organ music tradition is constantly renewed through the profound contribution of children and young people as active participants. I am looking forward to contributing to the Trust’s vital work in developing an even deeper and wider access to this unique tradition, and in helping to shape a vastly more equal musical culture of the future.’

Jonathan Macdonald, Chair of Trustees, added: ‘We are delighted to welcome Simon Toyne as a trustee. He brings a wealth of experience across both the music and education sectors, alongside a lifelong passion for choral and organ music. Simon joins the Trust at a crucial stage in its development, as we work towards our mission of transforming more lives through cathedral music.’

Anna Lapwood, Director of Music at Pembroke College, Cambridge and a Cathedral Music Trust Ambassador, has been appointed MBE for services to music. Remarking on the honour, she said, ‘This honour has inspired me to keep pushing for the causes close to my heart. Everyone should have the option to pursue a career in music: nobody should feel they aren’t welcome in our industry because of who they are. Fighting for this is rarely easy, but the joy of seeing people unlock their potential makes it all worthwhile.’

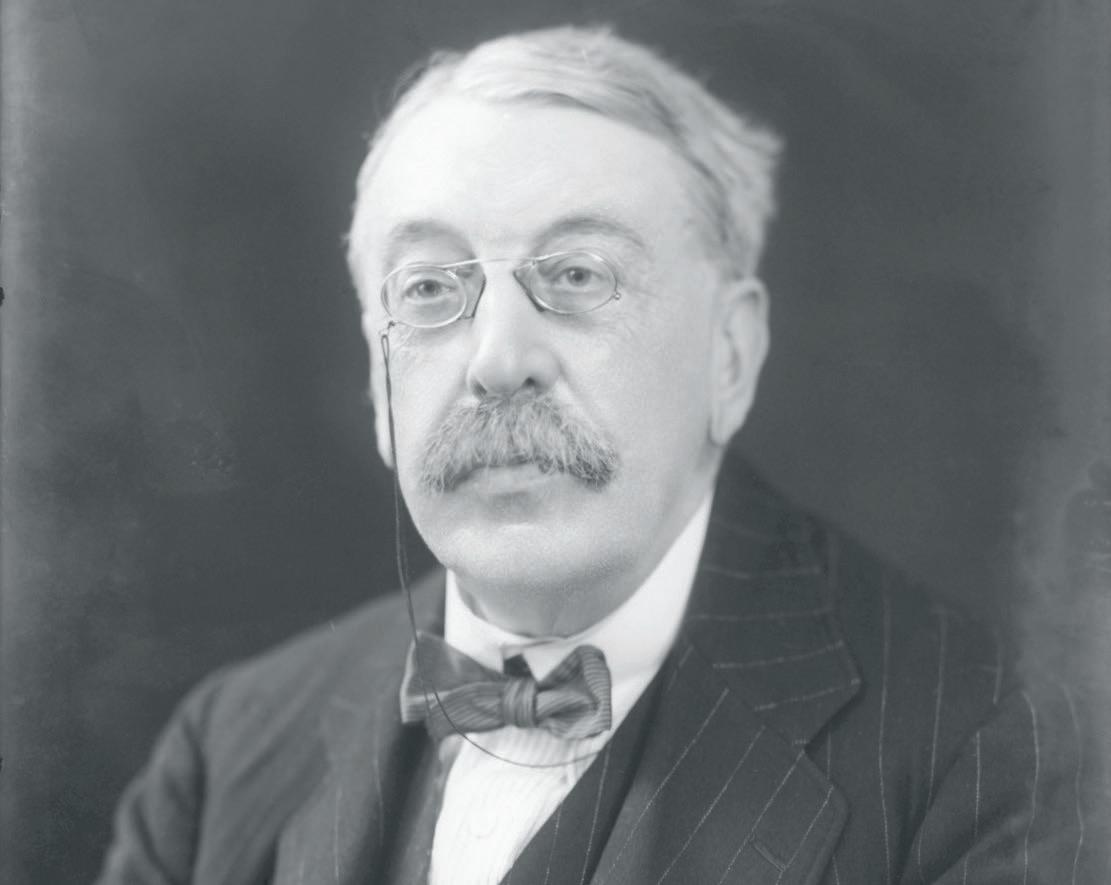

Edward Higginbottom has been awarded the Choral Director’s Lifetime Achievement Award by the Musicians’ Company in recognition of thirty-five years as Director of Music, fellow and tutor at New College, Oxford. Previous recipients include Stephen Cleobury, Harry Christophers, Christopher Robinson, Andrew Carwood and James O’Donnell.

Roy Massey, one of the twentieth century’s most influential organists and choir trainers, turns ninety on 9 May this year. As Organist and Master of the Choristers at Hereford Cathedral between 1974 and 2001, he oversaw nine seasons of the Three Choirs Festival and helped to shape the musical lives and careers of generations of singers and organists. Massey was awarded the Lambeth degree of Doctor of Music (DMus) in 1990 and appointed MBE in 1997; following his retirement from Hereford, he served as President of the Royal College of Organists from 2003 to 2005.

The Royal College of Organists (RCO) has launched The Organ Podcast, a fortnightly show designed to inform and entertain organists and organ enthusiasts alike, including those who are simply curious and want to know more about this unique instrument and its music. Episodes will feature interviews with leading UK and international organists, visit historic or littleknown organs of interest, catch-up with organ rebuilds and restorations, and encounter a diverse mix of individual organ-related news from around the UK. Host Mark O’Brien is both an organist and an awardwinning former BBC radio and televsion producer. He said: ‘The aim is to make a show which is friendly, informal and entertaining, but at the same time as being an intelligent and authoritative guide to the whole world of the organ. In that spirit we will be covering all manner of organ-related activities and cultural aspects, exploring performance, organ design and history, the instrument’s many secular as well as liturgical uses, different approaches to educational and outreach work, the organ’s links with choral traditions, as well as the insights, experiences and stories of organists around the world.’

The Organ Podcast is available free of charge from Apple, Spotify, Google, Amazon, Buzzsprout and all popular podcast directories; it is also available to hear via the RCO’s YouTube page, and the RCO content platform iRCO (with either a member or free guest account).

The British composer, conductor and producer James Whitbourn has died at the age of 60, following a cancer diagnosis. A graduate of Magdalen College, Oxford, his career in music began in the BBC, for whom he worked as a composer, conductor, producer and presenter; from 1990 to 2001 he served as Editor of BBC Radio 3’s weekly Choral Evensong series. He had a close association with the choir of King’s College, Cambridge, having produced the BBC television broadcasts of Carols from King’s for more than thirty years. He also worked for many years as the Executive Producer for the Royal Opera House’s Opus Arte label. As a composer Whitbourn focused on choral writing, often in combination with instrumental or orchestral forces. His most popular works included his portrait of Anne Frank, Annelies; the multi-media choral work Luminosity; and the Son of God Mass, a work for saxophone and choir. Recent works included Arise, my love, Christmas Welcome, O magnum mysterium, Shchedryk, Solitude and Our Gold, all published in Oxford University Press’s Carols for Choirs 6. He received four Grammy nominations and one Gramophone nomination.

Whitbourn’s orchestral catalogue includes the award-winning work Pika, based on the bombing of Hiroshima, one of three large-scale compositions for symphony orchestra written with the poet Michael Symmons Roberts and performed by the BBC Philharmonic, who also recorded many of his television scores.

His commissions included the music to mark several national and international events, such as the BBC’s title music for the funeral of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother in 2002 and music for the commemoration of 9/11 at Westminster Abbey in 2001 (subsequently performed in New York on the first anniversary of the attacks). He also composed music for the BBC’s coverage in 2004 of the sixtieth anniversary of D-Day. Whitbourn was Fellow and Director of Music at St Edmund Hall, Oxford; Senior Research Fellow at St Stephen’s House, Oxford; Director of Music at Harris Manchester College, Oxford; and a member of the Faculty of Music in the University of Oxford. He held long-standing associations with the University of Cambridge and with Westminster Choir College of Rider University in Princeton, USA.

This year, the Royal College of Organists honours five distinguished musicians for their achievements in organ and choral music with the award of the Medal of the Royal College of Organists (‘The RCO Medal’): Professor Graham Barber, ‘in recognition of distinguished achievement in organ performance, pedagogy and scholarship’; Dominic Gwynn, ‘in recognition of distinguished achievement in organ building and scholarship, in particular with respect to UK organ heritage’; Sofi Jeannin, ‘in recognition of distinguished achievement in choral directing’; Dr Stephen Layton MBE, ‘in recognition of

Former Sub-Dean of Westminster Abbey, Canon David Hutt, has presented a bronze maquette of Benjamin Britten to the Abbey Choir School, to celebrate his eighty-fifth birthday. The eighteen-inch tall sculpture, by Ian Rank-Broadley, is one of a limited edition (based on the full-sized statue that will be erected in Britten’s boyhood home town of Lowestoft) and shows the composer as a young boy of around fourteen.

distinguished achievement in choral directing’; and Dr David Ponsford, ‘in recognition of distinguished achievement in organ performance and scholarship’.

President of the RCO, David Hill says: ‘The 2024 honorands are both respected and celebrated in their respective fields. The RCO Medal acknowledges their many achievements, and we warmly congratulate them and thank them for their immense contribution to choral and organ music.’ Four of the recipients were presented with their medals at Southwark Cathedral in March; Sofi Jeannin will be awarded her medal at the 2025 ceremony.

Cathedral Music Trust has announced a new cohort of Future Leaders, who will work to shape the future of cathedral music in the UK and beyond: James Bartlett, Nicholas Bown, Isobel Chesman, Alistair Donaghue, Charlotte Gauthier, Iris Lam, Meg Rees, Jordan Theis, Ben Thompson, David Whitworth and Daisy Widdicombe join nine existing Future Leaders. This year the whole group will establish a Future Leaders’ Network, to offer professional development opportunities to young people working within the sector. Thanks go to the outgoing Future Leaders –Thomas Allery, Daniel Maw, Eilidh Owen and Rupert Scarratt – for their contributions over the past two years. A special mention goes to Imogen Morgan who steps down from the role of Co-Chair having established the Future Leaders as essential to the work of the Trust alongside Elizabeth Leather, who continues as CoChair (with David Whitworth) for the coming year.

To celebrate its fortieth anniversary, the Pratt Green Trust, which exists to further the cause of hymnody, has announced a hymn-writing competition, encouraging the creation of new words or the composition of a new tune for a text by Dr Fred Pratt Green; he was a prolific writer of hymns, including the ever-popular ‘When in our music God is glorified’, ‘For the fruits of his creation’ and ‘Long ago, prophets knew’. To enter, visit prattgreentrust.org.uk by the closing date of 10 May 2024.

Andrew Lumsden, Organist and Master of the Choristers at Winchester Cathedral, has been awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Winchester ‘in recognition of his immense contribution to church music in Hampshire and beyond, as well as directing one of the leading Cathedral Choirs and Music Departments in the country’.

The Women’s Sacred Music Project has published a new collection of hymns, entitled Resounding Voices, which complements its 2003 publication Voices Found; the two volumes feature the work of female authors and composers, and are published in conjunction with The Hymn Society in the USA and Canada.

The 2024 Southern Cathedrals Festival will take place in Winchester between 11 and 14 July, with services and concerts given by musicians from Chichester, Salisbury and Winchester cathedrals; for full programme details, visit southerncathedralsfestival. org.uk

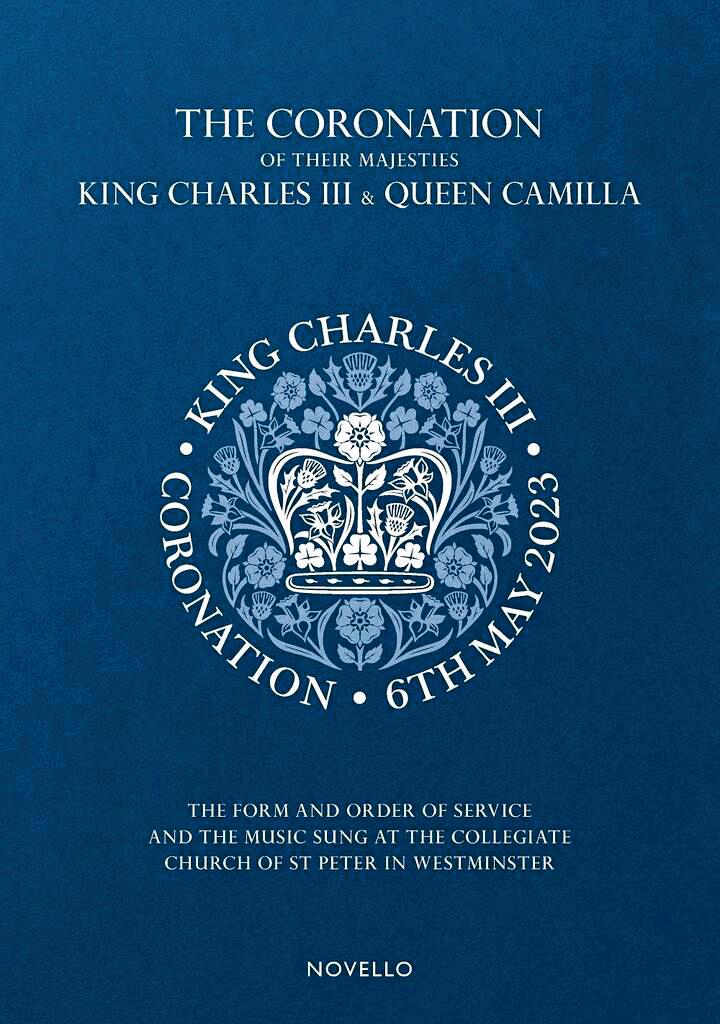

Novello & Co. has published the full order of service and vocal scores of all the choral music performed at the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla on 6 May 2023 at Westminster Abbey. The 224-page book includes the six new commissions heard in the service – Coronation Kyrie (Paul Mealor), Alleluia (O clap your hands) – Alleluia (O sing praises) (Debbie Wiseman), Make a joyful noise (Andrew Lloyd Webber), Coronation Sanctus (Roxanna Panufnik) and Coronation Agnus Dei (Tarik O’Regan) – and the arrangements of ‘Christ is made the sure foundation’ and ‘Praise, my soul, the King of heaven’ made by James O’Donnell and Christopher Robinson respectively.

Cathedral Music Trust’s 2024 conference will focus on themes of education and participation, diversity and inclusivity, the intersection of theology and music, the chorister experience, and liturgical music in the twenty-first century. Perspectives of the current generation of participants and perspectives of the new generation of cathedral music researchers will make this conference a vibrant, exciting event for everyone involved in this field. Leading academics, practitioners and musicians will be presenting alongside postgraduate researchers, including many of the Trust’s Future Leaders. The event will provide opportunities for dynamic conversations and fresh insights, interdisciplinary collaboration and the exchange of innovative ideas.

19–20 September, Sarum College, Salisbury. More information, including how to book, will be available on the Cathedral Music Trust website from 3 May.

The Multitude of Voyces foundation, which promotes music and performance by and with those from underrepresented and marginalised groups, is fundraising to bring the music of Elizabeth Poston back into the public consciousness. Best known for her carol Jesus Christ the Apple Tree, Poston left many manuscripts on her death in 1987, and Multitude of Voyces is continuing the work of Dr John Alabaster in creating new editions of out-of-print and unpublished works. For more information, or to donate, visit multitudeofvoyces.co.uk

The Clergy Support Trust Festival Service will be held for the 369th time this year, for which the choir of St Paul’s Cathedral will be joined by those from Durham and Rochester cathedrals; the sermon will be given by the Most Reverend Andrew John, Archbishop of Wales and Bishop of Bangor.

The Festival Service is the occasion, more than any other, that helps to bring the work of the Clergy Support Trust (CST) to a national and international audience. Chief Executive of the CST, Revd Ben Cahill-Nicholls, explains that the Festival Service is three things. ‘First, it is an act of worship. Second, it is an occasion of thanksgiving for the work of the charity but also for ministry in all its fullness.

‘Third, it’s a choral service on a grand scale, and one that really demonstrates the power of the choral repertoire – when you have 120 singers together under the dome of St Paul’s it’s impossible not to be moved and thrilled in equal measure. And since cathedral choirs from

across the country are invited to take part on rotation, each combination of choirs has never been heard before, which is quite a moving thought.

‘We’re particularly excited about the music planned for this year’s service, which is a real choral journey. There will be pieces from Gabrieli through to Cecilia McDowall, and a real highlight is Elgar’s Give unto the Lord, which all three choirs will be singing together: it was written for the Sons of the Clergy [the forerunner to the CST] Festival of 1914, and so it’s lovely to be reminded of the history of the event.’

The CST’s history is a great deal longer than those 110 years; founded in 1655 to support clergy who had been made destitute during the Commonwealth, today the charity supports over 22% of Church of England clergy and their families, and in 2023 helped more than 2,700 households.

Cahill-Nicholls points out that the CST is ‘a rare organisation, in that we have essentially been carrying out

the same work since our creation, albeit with a few changes of name along the way – we have been providing the same kinds of support to more or less the same groups of people for nearly four centuries.’

Returning to the topic of the Festival Service, Cahill-Nicholls recalls how central choral music was to his journey of faith and to discerning his vocation, and talks enthusiastically of ‘how undervalued, underfunded and underappreciated’ Anglican choral music is.

‘Faith and music form such a powerful relationship, and cathedral music is a world that really shows that on a day-to-day basis; whether clergy or musicians, all of us are leading worship, both on an occasion such as the Festival Service or at a weekday Evensong, and I believe that is something to be extremely thankful for.’

This year’s Festival Service takes place at 5pm on Tuesday 7 May; to book a free ticket, visit clergysupport.org.uk/festival-2024.

The tenth anniversary of girl choristers in the choir of Canterbury Cathedral was celebrated at Evensong on 28 January with the premiere of a specially-written

The winners have been announced of the 2023 BBC Young Chorister of the Year, the first time the BBC Young Chorister of the Year competition was run along Junior and Senior categories rather than selecting a boy’s winner and a girl’s winner. Belinda Gifford-Guy – a former chorister at Wells Cathedral and now a specialist singer at Wells Cathedral School – won the Junior category, while Natalie Fooks – a student at Sheffield Girls’ High School –won the Senior category.

anthem by Gabriel Jackson. A setting of verses from Psalm 147, O praise the Lord, was commissioned by the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury and conducted by David Newsholme.

Norwich Cathedral has announced that from January 2024 girls will be able to audition alongside boys to join the Cathedral Choir and take up chorister scholarships at Norwich School. This will offer choral opportunities to boys and girls alike from the age of six to eighteen, increasing the range of opportunities available and ensuring the finest young voices can contribute to the Cathedral’s rich musical life. Until now, places for the Cathedral’s younger choristers have been open to only boys, although in 1995 the Cathedral started a senior girls’ choir for eleven- to eighteen-year-olds. Additionally, there are now plans to create a new group of senior boy choristers, giving teenage boys the opportunity to sing at Norwich. Both the senior boy and senior girl chorister groups will be open to young people from any school across Norfolk.

The choristers of Winchester Cathedral, Stephen Barton (composer and former chorister), and American composer Gordy Haab have won a Grammy Award for the Best Soundtrack for Video Games and other Interactive Media. Accepting this prestigious award, Stephen said, ‘A special moment for me on this, was [that] we had the choristers from The Pilgrims’ School in Winchester come and record on this. It reminded me about music teachers being the most important thing, so I dedicate this to mine.’ Back in 2022, Stephen engaged the choristers to take part in a recording project at Abbey Road Studios in London. The choristers, who sing with the Winchester Cathedral Choir and are educated at The Pilgrims’ School, can be heard on the soundtrack for the new video game, Star Wars Jedi: Survivor. Director of Music at Winchester Cathedral, Andrew Lumsden, said of the choristers’ achievement, ‘This is fantastic news for all of us at the Cathedral and The Pilgrims’ School but particularly for the choristers. They are thrilled to have won the award and are over the moon with excitement. It is also very exciting that we have similar projects already in the pipeline.’

The Grand Organ of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral has recently undergone restoration work. The project, which involved removing, cleaning and restoring each of its 4,565 individual pipes, took eighteen months to complete at a cost of over £1 million. This work was carried out by specialist organ builders Harrison & Harrison. Dr John Rowntree, Organist and Director of the Choir at Douai Abbey, acted as adviser for the project, and reports on the work.

The 1967 Walker organ of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral is iconic. It followed the influential, 1954, neo-Classical, electro-pneumatic organs of the Royal Festival Hall (Harrison) and Brompton Oratory (Walker). However, by 2015, the mechanisms, especially the schwimmers and compensators regulating the wind supply, were failing. The organ was unable to stay in tune: it was time for renovation.

The concrete organ chamber provided by the cathedral architect, Francis Gibberd, was problematic, being high at the front and low at the rear; this made it difficult to place big pedal pipes, some of which remain in a trench at the rear of the chamber. The adviser in the 1960s, Richard Wright OSB, a monk of Ampleforth Abbey, had wished the Liverpool organ to have more stops than the 104 in the Ampleforth Walker instrument; however, the chamber proved inadequate for even the 88 stops eventually installed, which were shoehorned in, without walkways for maintenance.

Equally unsatisfactory was access to the gallery, which was via an iron ladder twenty-six feet in height up narrow concrete channel from the car park beneath the cathedral.

Discussions began in 2015 and stalled. In 2019 four organ-builders were asked to tender. Concerns included: lack of power, extending the platform for more organ, a new nave section, mobile console, and re-voicing. One firm even suggested

replacing the organ entirely –providing a highly detailed submission. It was refreshing that the Cathedral Organ Committee –Dr Christopher McElroy, Director of Music; James Luxton, Assistant Director of Music; Richard Lea, Cathedral Organist; Terry Duffy, Cathedral Organist from prior to its opening in 1963 to 1993 and Director of Music 2004-07; and myself as Adviser – were unanimous that the organ had successfully served the cathedral since its installation in 1967 and should retain its integrity.

Harrison & Harrison were selected to undertake the work. The organ layout was re-configured for tonal egress and balance, and walkways for maintenance were installed. After the reconfiguration design was approved, the contract was signed and work commenced. Asbestos was then found in various parts of the organ. This led to a considerable delay, as mechanisms and pipework had to be decontaminated with the

assistance of asbestos experts. Finally, work recommenced.

One tonal change was agreed. The Postive had two 4ft flutes. One was replaced by a 4ft Principal to give better internal balance, and cohesion when coupled to the Great.

Tuning the Positive Cymbale, on the gallery edge, was hazardous. It was relocated to the rear of the chest. A safety restraint was installed for tuners! The Great Trumpets were moved from behind the Swell box to behind the Great chests.

Gibberd had not provided the gallery with a floor, merely a series of concrete upstands. The discarding of the schwimmers meant the new wind trunking had to go up, over, and around the upstands. Happily, amidst all the new technology the mechanical connection from console to swell boxes, 140 feet in length, was retained. The work was completed in 2023, and the newly restored organ was formally unveiled in early 2024.

Five patrons from across the worlds of public service and the arts have lent their support to the St Margaret’s Choristers – a new girls’ choir founded at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster, in 2023. The patrons are: actress and author Baroness (Floella) Benjamin; Baroness (Sue) Carr, Lady Chief Justice; broadcaster Katie Derham; Sir Lindsay Hoyle, Speaker of the House of Commons; and Baroness (Genista) McIntosh, Senior Deputy Speaker of the House of Lords.

The St Margaret’s Choristers began meeting last September. The choir is made up of twenty girls aged between 11 and 17, drawn from schools across London, who receive free singing tuition as well as a generous scholarship. Under the direction of Greg Morris, Director of Music at St Margaret’s, they have the opportunity to perform some of the great cathedral music repertoire alongside the professional singers of the St Margaret’s Consort.

The Three Choirs Festival has announced the programme for its 2024 edition, with a celebration of nature and its enduring influence on composers and musicians at its heart. Highlights of this year’s festival include the UK premiere of Sarah Kirkland Snider’s Mass for the Endangered, Elgar’s The Kingdom, Gustav Holst’s The Cloud Messenger and Bob Chilcott’s The Angry Planet, with performances from the Three Choirs Festival Chorus, the Festival Youth Choir, Festival Voices, Three Cathedral Choirs, the BBC Singers and orchestrain-residence, the Philharmonia. There will also be smaller, more

intimate concerts and a lively programme of family events, with soloists and performers including Anna Lapwood, Marta Fontanals-Simmons, Robert Plane, Francesca Chiejina, Jocelyn Freeman and Toby Spence. The 2024 festival marks Holst’s 150th anniversary, the 100th anniversary of Stanford’s death and the 70th birthdays of Judith Weir and the late Steve Martland, as well as including festival commissions from Nathan James Dearden, Paul Mealor and Luke Lewis.

The Three Choirs Festival takes place between 27 July and 3 August in Worcester; 3choirs.org

The Choir of St John’s College, Cambridge has premiered a triptych of works by composer Joanna Marsh and poet Malcolm Guite. The first part, The Hidden Light, was performed at the Choir’s Advent carol services last year; Refugee was performed at the Epiphany carol services in January 2024; and Still to Dust was premiered in March. The Choir will record the three pieces in the summer for release on the St John’s imprint label on Signum Classics in 2025.

Michael Whitefoot NATURE The Choir of St John’s College, Cambridge and Director of Music Christopher GrayWe offer our congratulations to the following, who are on the move

Helen Brookes has been appointed Singing Partnerships Lead at Canterbury Cathedral, where she will design and deliver opportunities for high-level musical engagement in the local community

William Fox has been chosen as Director of Music at St Albans Cathedral; currently Assistant Director of Music at St Paul’s Cathedral, he was Organ Scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford and at Hereford and Wells cathedrals

Timothy Parsons, Director of Music at St Edmundsbury Cathedral, will take up the same position at Wells in September; he was formerly Assistant Director of Music at Exeter Cathedral

William Campbell has been appointed Organist at Leeds Cathedral. He was Organ Scholar at Canterbury Cathedral, and formerly held posts at St Helen’s, Stonegate in York and Leeds Minster

Claudia Grinnell has been appointed as Director of Music at St Edmundsbury Cathedral. SubOrganist at Winchester Cathedral since 2017, she was formerly Organ Scholar at Salisbury Cathedral and Peterhouse, Cambridge

Carolyn Craig has been appointed Assistant Director of Music at Wells Cathedral; she is currently Organ Scholar of Westminster Abbey, and was previously at Truro Cathedral and Westminster Cathedral

The Revd Canon Dr Victoria Johnson is the new Dean of Chapel at St John’s College, Cambridge, having been Canon Precentor at York Minster; she has a PhD in biochemistry and was a research scientist before ordination

St Paul’s Cathedral has announced three new appointments. William Bruce (left) has moved from Choral Director for the Diocese of Leeds to become Artistic Director of Choral Partnerhips; Jeremiah Stephenson (centre), who remains Associate Director of Music at All Saints, Margaret Street, is the new Organ Education Lead; and Alexander Knight (right) has been appointed Organ Scholar following his studies at the Royal College of Music

Don’t miss the opportunity to join a Cathedral Music Trust gathering near you

SUNDAY 2 JUNE 2024

Tower of London Gathering

Book now for a service of Choral Matins in the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. The service will be followed by a talk and organ demonstration, and the chance to visit St John’s Chapel in the White Tower.

SUNDAY 9 JUNE 2024

St Edmundsbury Cathedral

Observe the choir’s rehearsal for Evensong before attending the service, followed by a concert of organ duets by Timothy Parsons (Director of Music) and Richard Cook (Assistant Director of Music).

THURSDAY 19–FRIDAY 20

SEPTEMBER 2024

Cathedral Music: New Generation Perspectives

Cathedral Music Trust’s academic conference will focus on themes of

education and participation, diversity and inclusivity, the intersection of theology and music, the chorister experience, and liturgical music in the twenty-first century. Booking opens 3 May.

FRIDAY 20–SUNDAY 22

SEPTEMBER 2024

Salisbury National Gathering

Book now for our Autumn National Gathering and spend a long weekend with fellow cathedral music lovers in Salisbury, including all choral services, plus a talk by David Halls (Director of Music), an organ recital by John Challenger (Assistant Director of Music), and a choice of tours around the cathedral, cloisters and close over the three days.

TUESDAY 8 OCTOBER 2024

St Paul’s Cathedral, London

Save the date for ‘The Musicians of

St Paul’s’, taking in Choral Evensong, a talk by Director of Music Andrew Carwood and a concert of Stanford part-songs by the Vicars Choral.

SATURDAY 16 NOVEMBER 2024

St Bartholomew the Great

Save the date for a joint gathering of Cathedral Music Trust and the Prayer Book Society, including Choral Mattins, a talk by Rupert Gough (Director of Music) on the history of music at St Bart’s, an organ recital by James Norrey (Assistant Director of Music) and a service of Choral Evensong.

For more information or to book, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/ events, email

info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk, or call 020 3151 6096 (Mon–Fri, 9am–4pm).

As a Friend or Patron of Cathedral Music Trust, the support that you give allows us to make grants to cathedrals and churches all over the UK to fund their work. In 2023 the Trust made thirty-three awards totalling nearly £500,000; we profile a selection of last year’s recipients to see the impact that their awards have had

By ADRIAN HORSEWOOD

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral received a grant of £25,000 to support choral and organ studentship pathways for former choristers

For Dr Christopher McElroy, Director of Music at the Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, Liverpool, an important word is ‘young’.

‘We’re an unusual cathedral because of when it was built, in 1967 – making us one of the youngest cathedrals in the country. Also, the contribution of children to our music is huge and always has been ever since the cathedral was consecrated.’

Although there have been boy choristers since the 1960s, it was only in the 2000s that girl choristers were introduced – building on the Youth Choir first set up by McElroy in 1999 when he was Organ Scholar at the cathedral, which marked the first time that girls’ voices were heard in the building.

‘We now have two excellent sets of choristers who all attend the two cathedral choir schools, as well as the Youth Choir –now predominantly made up of former choristers in school years 9 to 13 – which has grown greatly over the last seven to eight years.

‘What we felt was an important next step was to create a pathway for former choristers to continue with their musical education, for boys from the age of around twelve or thirteen, and girls when they stop being choristers at sixteen.

‘We were continually seeing these former choristers with as much musical talent, knowledge and enthusiasm as university students – I personally know of at least ten former choristers from this cathedral who are studying at music college or reading music at university – enjoying being able to sing with the Youth Choir, but in a way it was all going to waste without something more formalised.

‘We already had several more advanced singers, for whom choral music could potentially be a career, coming to sing with the lay clerks at every service – among our lay clerks and deputies we have ten former choristers – but we wanted to take things up another level.’

Funding from Cathedral Music Trust has gone towards supporting several schemes for former choristers of the cathedral: an Organists’ Pathway, which sees organ students accompany and direct the Youth Choir and also occasionally work with the Cathedral Choir; and choral students, who also help with the Youth Choir and some of the chorister rehearsals.

‘This year, the funding has allowed us to appoint three choral students and two organ students, each of whom works three or four days a week in the cathedral. They also have their own rehearsals each week, and receive singing lessons; this includes the organ students, as it’s extremely useful for organists to be able to sing and talk to singers about singing.’

The selection process for the studentships was ‘rigorous – as tough as applying for a scholarship at Oxbridge,’ according to McElroy, ‘and deliberately so. They had to fill in numerous forms and attend interviews and auditions. We had twelve applicants for the three choral studentships, so we didn’t make it easy for them!’

The grant from Cathedral Music Trust has also helped to fund a director for the Youth Choir, who is a former girl head chorister at the cathedral.

‘This and the studentships all enable choristers and their parents to see that there is a clear path for choristers: they will get to sing from eight to eighteen and learn so much more along the way.’

Chester Cathedral received a grant of £25,000 to support an organist who will also lead the development of a music outreach programme

The appointment of Daniel Mathieson (pictured above) as Head of Music Outreach and Assistant Organist at Chester Cathedral in September 2023 – supported by a grant from Cathedral Music Trust – heralded a new beginning in more ways than one.

As well as bringing the permanent music staff at Chester back up to three – its usual number, but which had not been the case since before the Covid-19 pandemic began in 2020 – Mathieson is spearheading the cathedral’s drive to bring its musical offering to a wider audience through projects and

collaborations across the local community and diocese.

Philip Rushforth, Organist and Master of the Choristers at Chester, is full of praise for how much Mathieson has achieved in such a short space of time – although he is also quick to acknowledge the hard work of Sub-Organist Alexander Lanigan-Palotai, during the pandemic.

‘Our current outreach work certainly isn’t new, but was definitely negatively impacted by Covid, and I’m very grateful to Alex for all that he has done to hold the fort during these last few years.

‘That said, we’re absolutely delighted with how smoothly Dan has set things in motion since his arrival. He has already organised two “Be a Chorister for the Day” events –one each for boys and girls – which were the first since 2020. They were both hugely oversubscribed, with over 100 enquiries in the first week alone; we’ve had to set up a waiting list for subsequent events later in the year.

‘Dan is also leading our partnerships with local state schools – we’re building up to holding a Schools Singing Day, in collaboration with Abbey Gate College, which we hope will also aid our chorister recruitment.

‘Before Alex and Dan joined us I was doing the bulk of working with schools, which I enjoyed, but it ended up being rather piecemeal and not very coordinated, to fit around my duties at the cathedral.’

Another facet to Mathieson’s role is overseeing the cathedral’s Saturday Singing Club for children aged between six and eleven; directed by one of the deputy lay clerks, it is a ‘useful trickle for finding choristers’, according to Rushforth.

‘In short, while we always worry about chorister recruitment, we worry much less now that Dan is on board and the music department feels complete again.

‘He helps us to tick all the boxes in terms of what we would like to provide musically for the cathedral and our local community, and to be honest it already feels as if he’s always been here!’

St Alphege, Solihull received a Church Choir Award of £6,000 to support a choral outreach project in local schools

St Alphege is the principal church in the parish of Solihull, and Director of Music Christopher Martin Thomas presides over a busy choral programme that sees five choirs regularly singing services each week: the Junior Choir (for children in school years 3–6), Boys’ Choir (former choristers include organist Iain Simcock, founder-director of Tenebrae Nigel Short, and Christopher Monks, director of the Armonico Consort), Girls’ Choir (whose alumnae include Alice Halstead, BBC Young Chorister of the Year in 2008), Men’s Choir (with choral scholars regularly moving up from the Boys’ and Girls’ Choirs), and the Ladies’ Choir.

Alongside this the Minims group is for five- and six-year-olds, who enjoy a thirtyminute musical fun session that overlaps with the Junior Choir’s Friday rehearsal, acting as a conduit for the youngest children.

Thanks to a Church Choir Award from Cathedral Music Trust, St Alphege has recently expanded its thriving choral offering to local primary schools, with its ‘Rising Stars!’ outreach project for Key Stage 2

children, running in partnership with Tudor Grange Primary Academy Yew Tree, Sharmans Cross Junior School, Widney Junior School and Oak Cottage Primary School – all within 1.5 miles of the church.

In March the four school choirs combined to perform Michael Flanders and Joseph Horowitz’s Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo at St Alphege’s, and in June the church will host an All-Stars concert – a ‘talent festival’ in which each school choir will present a mix of choral pieces, solos and instrumental pieces, before all combining for a grand finale.

For Thomas these are the encouraging fruits of much labour and dedication. ‘The first two terms have gone very well, and the Church Choir Award has meant that we could approach schools and say, “There is no charge to you or your pupils to take part”.

‘It’s a refreshing change from some of my previous jobs, when I found myself constantly fighting those who doubted that this kind of choral outreach work by a church could actually benefit schools. Many headteachers see it as just an add-on to whatever music provision they might already have, and don’t appreciate the wider benefits to the schools. The choristers play a big part in school choirs and help to encourage their friends, who in turn become interested and potentially inspired to become choristers themselves.’

St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, Cork received a grant of £15,000 to support singing lessons for choristers and junior lay vicars

When Peter Stobart was appointed Director of Music at St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, Cork in 2015, it was immediately apparent that singer recruitment would be one of his priorities.

‘The girls’ choir was – and has always been – in good shape, but there were only eight boys, seven of whom had started only a month or so before me! Thankfully our numbers are now much healthier and we have a full complement of sixteen boys.’

One particular aspect Stobart quickly homed in on was how to maintain the boys’ singing beyond their voices changing. ‘This was a key point at which many of them started to drift away from the choir; also, as the move from primary to seconday school happens a year later than in the UK [i.e. after the year in which a child turns twelve], we found that parents were often keen for their children to focus on school work.’

This was a key factor in the application to Cathedral Music Trust for funding towards singing lessons for choristers and young lay vicars. ‘The choristers aren’t in the cathedral

every day, so any additional singing they do is helpful for their vocal health. It also encourages them to keep singing by giving them some technical know-how and support.

‘Also, put simply, it’s often hard to find adults who can turn up and sight-read, so it’s very important to keep hold of those I’ve trained as choristers and encourage them to continue to sing as adults.

‘We’ve already hit the ground running, having started weekly lessons in September 2023. We have two teachers, one for the younger children and the other for the older, and they’ve been very popular.

‘In particular, we found that after the Covid-19 pandemic, we had teenage boys whose voices had changed in the interim who came back wanting to sing, but clearly all the vocal training they’d received was as trebles, so they needed a different kind of support.’

Working with schools is also a key part of this focus on chorister retention. ‘In 2017 we set up the Diocesan Church Music Scheme to foster singing and musical education in schools and churches throughout the diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, and my Assistant Director of Music and I visit five or six schools a week. We’re trying to create a culture of singing within the Church of Ireland primary schools in the diocese.’

Inverness Cathedral received a grant of £4,500 to support three choral scholarships and an organ scholarship

Home to the northenmost cathedral in the British Isles, Inverness has long had to contend with being off the beaten track. The remoteness was part of the attraction for Adrian Marple and his family, who moved to Scotland from Suffolk in 2019; but on his appointment as Director of Music at the cathedral in 2022, Marple felt that it was also important to think about how to offer opportunities to younger singers in Inverness and the surrounding region.

‘I was lucky to inherit a choir of loyal and long-standing adult volunteer singers – I was the youngest person in the room at rehearsals – who were also a close-knit group of friends. However, there hadn’t been any youth element to the cathedral’s music offering for many years, which was something I was keen to develop.

‘The grant from Cathedral Music Trust enabled us to recruit this year’s choral and organ scholars, who have made such a difference not only to the sound of the choir, but also to our whole approach to music and the liturgy – they’ve brought fresh ideas and asked questions about things that we older hands perhaps have done unquestioningly for years.’

The new scholars have a weekly meeting with Marple before the main Friday evening rehearsal. ‘Initially this was about showing them the ropes – talking about choral singing and repertoire, but also practical things about services and worship – but this has evolved into more interesting discussions about issues such as faith and the Psalms, which has been great to witness.’

Marple is particularly enthusiastic about how much the current organ scholar, Hannah Spencer, has benefited from her experience with the choir. ‘When Hannah joined us she had never played the organ before and was starting completely from scratch – although as a good pianist and traditional fiddler she was very musical. She had a background in a different church, so the Anglican repertoire and liturgy was all new to her.

‘But she has been desperate to practise as much as she can, and also sings with the choir and plays for rehearsals; she has also recently accompanied her first anthem with the choir, and it has been fantastic to watch her development as a musician.’

As well as training the new scholars, Marple has initiated a Junior Choir at the cathedral for children aged between six and thirteen, which takes place after school on a Friday. ‘This started off as a small choir of just a few children who like singing, but has grown hugely – the next step is to include them in the liturgy from time to time. This is another aspect to cathedral music where the scholars have been invaluable.’

For more information on the Trust’s grant programmes and other recipients of awards, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/grants

5 April - 7 November 2024, UK-wide tour

Something old, something new, something borrowed. Celebrating the art of imitation, the richly sensual music of Lassus and Josquin provides a stunning centrepiece to world renowned choir The Sixteen’s 2024 Choral Pilgrimage programme, inspiring a new work by Bob Chilcott and wrapping around songs from overlooked female composer Maddalena Casulana.

now

The ever-popular church music of Charles Villiers Stanford, the centenary of whose death falls this year, was but one part of the output of this extraordinary creative mind

By JEREMY DIBBLEABOVE RIGHT

With the exception of such works as the immutable The Blue Bird, the stirring Songs of the Sea and Songs of the Fleet and the Piano Concerto No. 2, Stanford’s reputation for most of the twentieth century resided in his unique contribution to music for the Anglican liturgy. Few would challenge the elevated status of its compositional originality, its intellectual qualities of invention or the high satisfaction derived from performing it from those who have participated in church, chapel and cathedral choirs across the English-speaking world. Indeed, to all who admire English church music, the name of Stanford is a household word. Yet we have perhaps never stopped to consider, given the strictures placed on the composition of liturgical anthems and settings of the canticles (there was always the restricted time factor to consider), what sort of creative personality came to write such music and what kind of creative stimuli contributed to its unequalled status and integrity.

In one respect, Stanford’s intensive background in church music at the two Dublin cathedrals during the 1850s and 1860s was undoubtedly a key formative experience, as were the twenty-two years he spent as a practising church musician and organist in Cambridge between 1870 and 1892. In this environment he learned not only to appreciate the entire history and changing styles of English church repertoire from the renaissance to the nineteenth century (and we know this from the surviving music lists at Trinity College, Cambridge), one which engendered a pioneering reverence for Elizabethan and Jacobean polyphony, Purcell and Blow, the more commonly accepted gamut of eighteenth-century composers such as Handel, Boyce, Greene, Nares and Travers (which still held sway in many cathedral and collegiate institutions), and the more contemporary voices of Thomas Walmisley (Stanford’s distinguished predecessor at Trinity), S. S. Wesley, William Sterndale Bennett and Stainer. In his role as Director of Music, Stanford also learned how to train and discipline a choir within the context of the typical Anglican services of Matins, Communion and Evensong, the liturgical details of which were in the constant process of incremental change. Yet, it should be understood that Stanford’s

church music was not composed in a vacuum. Even while his employment at Cambridge was circumscribed by the execution of the divine service and the exigencies of its liturgical parameters, his outlook as a musician was highly ambitious. On his return to Trinity College, in January 1877, he had become well acquainted with a host of European names such as Joseph Joachim, Johannes Brahms, Ferdinand Hiller and Clara Schumann; he was familiar with Wagner’s new Ring cycle which he had heard at Bayreuth in 1876, and during 1877 (which witnessed Wagner’s visit to London), he cemented friendships with Edward Dannreuther, George Grove, Hubert Parry and Hans Richter. Additionally, he was the author of chamber music, a symphony, songs, church music and incidental music for the theatre besides initial plans for his first foray into grand opera with The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan. In Leipzig and Berlin as a student under Reinecke and Kiel, Stanford had already produced impressive settings of the ‘Pater Noster’ of 1874 and two commemoration anthems for Trinity (In memoria aeterna) of 1874 and 1876, the techniques of which he had probably gleaned from the examples of Mendelssohn’s music for the Lutheran liturgy, but by the time he returned to Cambridge his mind was full of the new German symphonic music, particularly the symphonies of Schumann (especially those with their experimental formal designs of a cyclic nature), the new instrumental concept of Wagner’s music dramas (coupled with the larger theory of the Gesamtkunstwerk), and the epic Doric architecture of Brahms’s First Symphony. After placing the Cambridge University Musical Society on the map with the first English hearing of Brahms’s symphony in March 1877, the production of his first major chamber works – the Cello Sonata op. 9 and the Violin Sonata op. 11 –and the first (and only) performance of his own First Symphony at the Crystal Palace in March 1879, Stanford’s creative imagination gained a new momentum, a new-found propensity which manifested itself in the Morning, Communion and Evening Service op. 10, published in 1879.

The multi-faceted symphonic matrix of his Service op. 10, where, as he later stressed, the presence of musical form was imperative, established a model for all his later service

‘In terms of its quality, invention and innovation Stanford’s church music remains unequalled’

music and many of his anthems, and the cyclic method of thematic inter-relationships was also a concept he developed in all his later services. Moreover, it seems likely that Stanford wanted in some way to be able to re-create a version of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk in his Service in B flat since, by thematically linking all his movements, a choir and congregation might take part in a broader experience of the Sunday liturgies, by way of the three main services of the day.

Stanford’s orchestral Service in A major op. 12, written for the Festival of the Sons of the Clergy, further crystallised his instrumental and formal approach to the composition of church music and this is nowhere more evident than in the orchestral role in the Nunc Dimittis which essentially dominates the structure. Similarly, the anthems Awake, my heart (1881), If then ye be risen with Christ (1883) and the masterly setting of The Lord is my shepherd (1886) are entirely symphonic in their processes of musical prose (which escape the regular phraseological periodicity of a good deal of Victorian liturgical music) and the manner in which the choir and organ (which might easily be replaced by an orchestra) closely interact thematically. Such questions of instrumentally-informed design are also worth examination in the later anthems such as the much neglected Arise, shine, for thy light is come (1905), the ebullient Easter anthem, Ye choirs of new Jerusalem op. 123 (1910), the bold setting of J. M. Neale’s translation from the Latin, Blessed city, heav’nly Salem op. 134 (1913) and the late How beauteous are their feet (1923), as well as the frequently overlooked Festal Communion

Service op. 128 (1910–11), a major composition which contains the often-sung Gloria, written for George V’s Coronation.

Stanford’s classical sense of discipline is also key to the understanding of a cappella works such as the Three Latin Motets op. 38 in which Justorum animae and Beati quorum via make inventive use of sonata principles while the through-composed, eight-part Coelos ascendit hodie reveals Stanford’s historical assimilation of seventeenthcentury antiphony.

This historical awareness lay at the heart of his six ‘hymn anthems’ op. 113 which draw on Baroque techniques of ‘chorale prelude’, while the magnificent Latin Magnificat op. 164 in eight voices, dedicated posthumously to Hubert Parry (1919), looks to the Bachian motet as well as the buoyancy of the Magnificat BWV 243.

As Stanford’s style matured, and the intricacy of his instrumental works intensified – we can observe this in the impressive catalogue of his later symphonies and chamber works – so did the conceptually experimental nature of his church music. The inspired rondo form of the Magnificat and the subtle monothematic canvas of the Nunc Dimittis from the Service in G op. 81, both of them idiomatic importations from the lieder tradition (as ‘songs’ of Mary and Simeon), are primary examples of this intellectual process. So are the ingenious (yet unlikely) variation techniques of the Magnificat in C op. 115 (1909) and the first of the Three Motets op. 135, Ye holy angels bright (1913) which were surely motivated by Stanford’s increasing preoccupation with instrumental variation forms, explored with great fecundity in his Concert Variations on an

‘Stanford’s church music was not composed in a vacuum … his outlook as a musician was highly ambitious’